RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

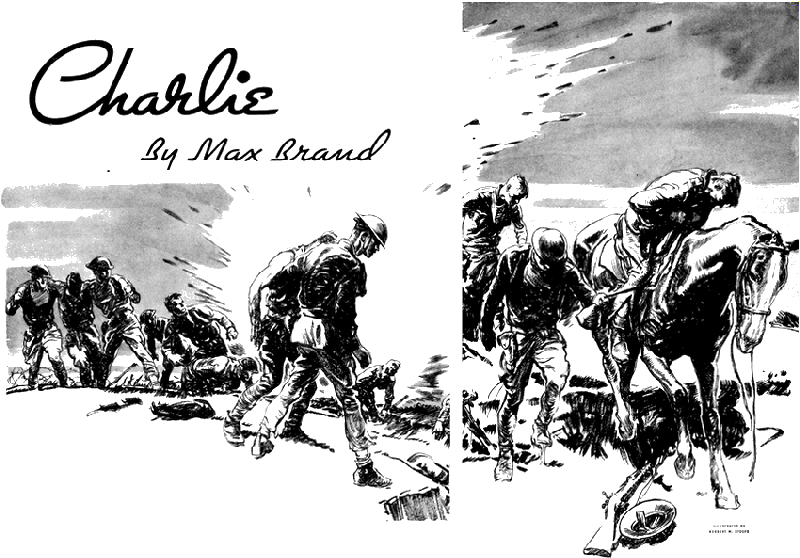

The American Magazine, February 1935 , with "Charlie"

They reached trenches smashed and ruined by shellfire. To cross

this confusion was like steering a boat through a choppy sea.

A generation has passed since the World War—lest

it be forgotten, here is a picture of the price of glory.

OF the Second Battalion there remained thirteen privates, Corporal Salters, and the sergeant in command. When the division went forward it was believed that the Germans were definitely on the run; therefore, the general pushed his light field artillery up close and kept it there during the advance. But out of the ground rose a fog which gave a great advantage to the Germans, because of course they could see in the dark. They hit that American division with a hard fist of shock troops and knocked a considerable hole in it. Among those who suffered was the light artillery and, particularly, the Second Battalion, under Major Hubert Tolliver. Shell-fire knocked the battery teams to pieces; the guns were claimed by the mud; and when the battalion tried to get home it bumped into Germans north, south, east, and west.

Staggered and mud-sick, the last commissioned officer gone, the survivors stopped marching because there was no place to go. The sergeant ordered the battalion to rest, so it stretched itself full-length in the mud, while the sergeant sat down cross-legged to think things over.

HE could see only a short distance because, though there was a full moon overhead, it sent only a meager cone of brightness through the ground mist. The Second Battalion was thus enclosed within a circular room fifty feet in diameter, of which the floor was French mud, while the walls and the ceiling were composed of nebulous, drifting white. The floor was variously furnished with tattered gas masks, some packsaddles, shell splinters half as long as a man's arm, some packs of wire made to open like an accordion, trembling scraps of paper, the butt ends of unexploded shells, mess kits, some broken wheels, odd twists of tin which were all that remained of a cook-wagon, old shoes at regular intervals, like a planted crop, and certain graceful sproutings of barbed wire rose from the ground like tall grass.

A great orchestra was playing for the entertainment of the Second Battalion. Bass viols boomed and roared to make an undertone with a steady plucking at the heavy strings, also; tenor drums rolled continually on a piercingly high note. Little flute voices came piping and made the Second Battalion tremble with interest in spite of all fatigue. Sergeant Carey rhythmically ducked his head to keep time with the droning of the wasp noises which flew past him singly or in swarms. And high above him and the mist were the woodwinds, drawing out their notes to an incredible length.

The sergeant looked at a shell hole so big that only the nearer half of it was visible; he looked at his command, nigger-black with mud; and then he began to hum a little song. The sergeant had not lied very much about his age when he enlisted and he was now, actually, nineteen. He was a blond young man who had been receiving a classical education in order to prepare himself for the selling of real estate five days out of seven and golf over the weekends. He was distinguished among his fellows by a pair of big hands which were perfect for hurling spiral forward passes or receiving them. At the present moment blood was running from a slash across his left side where a shot had glanced along his ribs. Otherwise he was unharmed, except that a bullet had bitten a chunk out of the rim of one ear. This caused him to reflect that if ever he wished to follow a career of crime he would have to have a new ear.

The sergeant now recognized his second in command by the size of the upturned feet. He rose, went to Corporal Salters, and wiped the mud from his face.

"Ah, there you are," said the sergeant.

"Where?" said the corporal, speaking out of one side of his mouth because a shell splinter had ripped the opposite cheek.

"That's what I came to ask you," said the sergeant.

"Go to hell," said Salters.

"I'm already there," declared Carey. " Sit up and keep me company."

He sat down and the corporal sat up.

"What's the idea?" asked Salters. "I thought this was a study period."

"It is," said Carey. "This is where we study our way out."

"There isn't any way out," replied the corporal.

THEY both ducked their heads as a sound flew past them, sharp and thin like the whistle of a bird. A little tremor ran through the muddy forms about them. One of these sat up and laid a hand on the pit of his stomach.

"How are you, kid?" asked the sergeant.

The kid bowed his head and said nothing. Then he lay down again, on his side.

"We're about to be one less," said the sergeant. "That chump Willis is cashing in."

The corporal said, "He never could stick on the back of a horse."

"What of it?" asked the sergeant.

"Yeah. What of it?" said the corporal.

"You're speaking to your commanding officer now," went on Carey "Rally the old bean and tell me what to do with this team."

"Try left end," said Salters, yawning. He propped himself up in the mud with both hands. He was very tired. They were all tired enough to last out a century of sleep. Some of the men were snoring and groaning at once, because their wounds were growing older, now, and the real pain was beginning.

"That's the trouble with the fellows in your college," said the sergeant. "No reverence for anything. No real spirit. You never really get behind the team."

"What you want me to do? Pray or something?" asked Salters.

"You wouldn't know how," answered Carey.

"You teach me, Big Boy. Show me your religious side, will you?"

"Sure, I will," agreed Carey, lifting his head.

He added, "Hey, God, why should we keep on playing overtime? Blow the whistle and let's all go home. There's not ten dollars in the bleachers, so why should we stay here bucking the line?"

"He doesn't seem to hear you, Big Boy," said the corporal.

"Speak up, God," said Carey. "You call the signals and we'll carry the ball."

"Look at that!" exclaimed the corporal.

Carey, turning his head, saw a horse with a bald, white face coming through the fog towards them. The saddle he carried was empty.

"It's Charlie!" said the sergeant. "It's the major's horse!"

He stood up and waved. "Hello, Charlie. How are you, kid?"

"He got a load off his mind when the major went West," remarked the corporal.

"'The origin of the salute,'" quoted Carey, "'is the knightly gesture of lifting the visor in recognition of a friend. A certain chivalry underlies all the customs of war.' Damn his heart!"

"He didn't have a heart, but it's damned, anyway," said the corporal.

"Come here, Charlie. That's the boy," said the sergeant.

THE horse came up to him and pricked his ears.

"He knows you, Big Boy," said the corporal.

"I had to hold him for two hours while the major was making up his mind to go somewhere," said the sergeant. "Charlie always had more brains than his master."

The horse began to blow out his breath and sniff loudly at the wounded side of Carey.

"Now you know the stuff we're made of, Charlie," commented the sergeant. "Going to leave us, boy?"

Bald-faced Charlie had started on at an unhurried walk, picking his way through the gleam of the barbed wire.

"Wait a minute!" shouted the sergeant.

He ran after the horse, his feet sinking in the mud, his knees sagging like the last five minutes of the game; but he overtook the major's horse and returned with it.

"What's the idea?" asked the corporal. "Maybe Charlie knows the way home. Get the boys up. We're going to turn Charlie loose and follow him."

It was hard to rouse the men, they were so utterly spent, but Carey was brisk about it. Finally he reached the last man on the ground. It was Willis, doubled into a knot.

"Hey, you awake?" shouted Carey.

He saw Willis' eyes open.

"Get up! We're going home!" said Carey.

Willis shook his head.

"Get up, yellow dog!" called Carey, and struck him heavily across the face.

"You bum!" said Willis, but kept both arms wrapped around his body.

"Sorry, kid," answered the sergeant. "I guess you've got it pretty bad. But up we come. Charlie's waiting on special purpose for you."

He lifted the bent body and shifted it into the saddle on the back of the horse. Willis, doubling over, clung with both hands.

"Go on, Charlie!" called the sergeant. "Look at him go! Keep your heads up, boys. This is the way home."

THEY went on, staggering. Every man in the Second Battalion carried at least one wound. Private Harmon, heir to seven millions, had been shot through the leg. Sometimes he walked and sometimes he crawled, until the sergeant took one of Harmon's hands over his shoulder and helped him forward in this way.

Corporal Salters elbowed his commanding officer out of the way and took charge of Harmon.

"You're commanding the whole Second Battalion, you fool," explained the corporal. "You're not the pack train that follows it."

The sergeant took the lead, following the horse, which sometimes almost disappeared in swirlings of the mist; and still Charlie, with pricking ears, followed a steady course.

Sanders fell to the rear. The sergeant ran back to him.

"I'm all right," said Sanders. "I'll catch up in a minute—"

The sergeant made him catch hold of one of Charlie's stirrup leathers. This added weight and all the mud did not slow the regular step of the horse.

They reached trenches ruined by shell-fire, with tatters of bags, jumbles of broken timbers. To cross this confusion was like steering a small boat through a choppy sea. Carey shepherded those sagging figures over the barrier, singing out, "Here's a milestone for you, boys. This shows you that we're on the way home!"

They were well beyond that line of trenches when Charlie disappeared. Carey, thinking that it might have been a shell hole into which the horse had slid, ran forward, and found Charlie stretched on the ground with a gaping wound in his side. Willis was dead. The streaked mud on his face made him look like a grinning mask of comedy.

The sergeant did not touch the dead man, but he leaned to stroke the head of Charlie; then he went on. If he could hang to the line which Charlie had sketched for them—but how could he keep to any direction across the vast junk-heap of the battlefield with never the glimpse of a star to guide him? The slant of the moonlight through the mist could tell him something, to be sure, but in a way far too inaccurate.

They had to go slowly. Every now and then one of the men dropped to hands and knees. Some of them had to be helped to their feet. Partridge lay flat and begged them to go on.

"Look!" said the sergeant. "We're a team. We've got to hang on all together."

He gave his help; Partridge got up and staggered ahead, his mouth hanging open and his eyes empty of knowledge.

Then, dim before them through the mist, dark outlines blossomed high in the air, disappeared, rose again. The earth was commencing to dance; a small rain of descending clouds and clattering bits of wreckage showered about the Second Battalion.

It halted without command. That way was blocked by a barrage through which not even a bird could have flown.

"Listen," said the corporal. "Who started this damn' war, anyway? "

The others had fallen prone to rest but the commanders remained on their feet for a wavering moment.

"You don't like it, eh?" asked Carey.

"I don't mind the shells and the poison gas; it's the mud, Big Boy."

"'A certain chivalry—'" quoted the sergeant.

"Say another prayer, Big Boy," suggested the corporal. "We got Charlie in answer to the last one."

"Hey, God, are you quitting?" demanded the sergeant, of the mist. "The whistle hasn't blown, but are you out of this game?"

Said the corporal, "I wouldn't want a drink. I'd only like to hold the glass in my hand. I'd just like to sniff it. I wouldn't roll it over my tongue. I'd just sit and look at it for a couple of years "

THE sergeant, resting on one knee, saw the mist thinning and, in the distance, the dim silhouette of a horse which moved across the horrible jumble of the field.

"Second Battalion, on your feet!" shouted the sergeant. "There's Charlie again, showing us the way home! Charlie, or his ghost, by God!"

The greatest miracle was the strength that poured like blood renewed through his body. He could stride about among the Second Battalion and jerk the fellows to their feet, where they stood reeling. But they saw that faint image of the horse through the mist and started towards it.

It was Charlie they found, with men hanging to the stirrup leathers, two holding to his tail.

The sergeant saw this, and that the ears of the horse were still pricked forward, and that something hung out from his wounded side.

A red madness came over the sergeant. He stormed among his men and beat them from their hold on Charlie.

"Give him his chance. Let him be!" he shouted. " You'd nail Christ to the Cross again, the lot of you."

So Charlie went on, with his head nodding cheerfully, and the Second Battalion reeled after him.

Twice Charlie stopped, as though he were not quite sure of his way and wished to consider it. But both times he went on again, until a dark river was faintly visible flowing through the mist. It was not water, because it moved above the surface of the ground with an odd wavering, and now the sergeant could hear the muffled treading of feet.

This meant capture, probably, but Carey paid little attention to the thought, for now the hindquarters of Charlie sank to the ground and he looked, with his attentive ears, like a great, foolish caricature of a rabbit, sitting up to view the landscape before hopping away to safety. But Charlie would never hop away, the sergeant knew. His numb legs bore him hurrying towards the horse just as the forehead of Charlie sank down with a certain shuddering. The sergeant was barely in time to drop cross-legged to the ground and take the head of Charlie in his lap. At the same time a voice sang out, "Who goes there?"

It was Corporal Salters who yelled in answer, "The Second Battalion—" but here his voice changed and burst into horribly neighing laughter.

It was Colonel Alfred Pearson Van Goss, young in years and further endowed with the eternal youth of West Point, who left the column with a detail to inquire into the nature of those shapes which dropped to the ground and rose slowly again.

AS he proceeded, smartly, with a thirty-inch step in spite of the mud, he came on a picture of a dozen men or so who were trying to get forward but were merely making an absurd wriggling through the mud.

The voice which had announced a Second Battalion and gone out in laughter before saying the second battalion of what, had been undoubtedly American. But this, of course, was not a battalion. A battalion, Van Goss knew, cannot be reduced to such an absurdity.

Here a large-caliber shell sailed through the air with a rhythmical zooming that sounded like several vast motors out of time. It plumped into the ground and lifted two hundred cubic feet of France into the air. This portion of France began to rain down on everything except, of course, the person of the Van Goss.

He noted, through the rain, the singular picture of a man seated cross-legged on the ground with the head of a horse in his lap. This was a manifest absurdity, because the horse was either dead or dying.

"Who's in command here?" demanded the colonel.

"Charlie," said the man on the ground.

"Charlie?" echoed Colonel Van Goss.

"Hysteria," said a firm-faced young man at the side of the colonel.

"Charlie the horse," said the man who sat on the ground.

"Stand up," said the colonel.

But Sergeant Carey was looking earnestly down into the eyes of Charlie and seeing in them the last flickerings of life.

Even the thrilling pathos of the speeches of Old Grads between halves, even those appeals to die for the dear old Alma Mater, had never dimmed the eyes of Carey, but now tears began to pour down over the mud on his face.

"Get up!" said a neat young lieutenant. "Get up and report to the colonel!"

"Go to hell, you cockeyed carbon copy of nothing!" said the sergeant.

"Get some stretcher bearers here," commanded the colonel. "These poor devils are out of their heads. Can no one tell me who's in command?"

"Charlie!" shouted Carey. "And God Almighty, you blithering fool!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.