RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

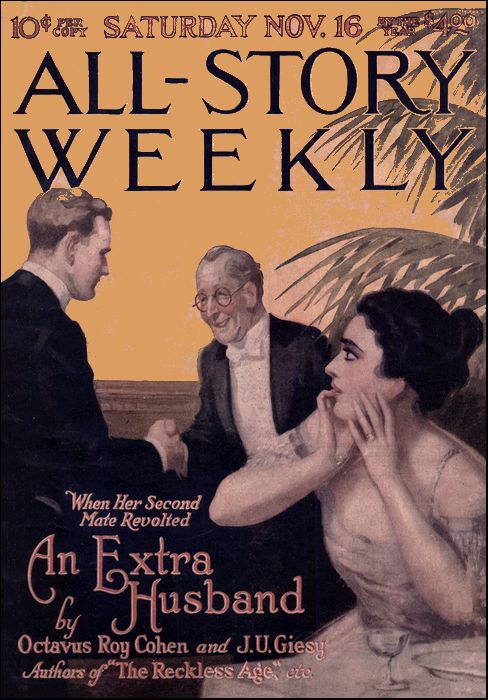

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 16 November 1918, with "The Great Stroke"

AN epigram has the same relation to truth that a duck pond has to the open sea. Like the ocean the pond reflects the blue sky, and in the same way, I suppose, all epigrams carry a partial truth. No doubt the duck finds his pond a noble stretch of water, and the maker of epigrams is generally inclined to despise all other forms of expression.

Jordan coined epigrams.

Otherwise he was a jovial fellow, but in an argument, he was, to be frank, an infernal nuisance. While one explained a theory and puffed it out with nebulous thoughts until it began to float, Jordan sat back with his hands folded, smiling serenely; but at the very critical moment when that inflated balloon of theory was about to leave the earth and soar to the clouds, he popped out with an epigram that pricked the bubble of an hour's fine dreaming, and in place of the noble balloon there remained only some fluttering fragments. The shadows of a thousand shattered conversations surrounded Jordan. I've no doubt they were to him what the scalps of dead enemies were to Indians.

Because he was so amiable in many ways I never confided to Jordan my inner opinion of his processes of thought, but finally he passed the forbidden line and the anger which I had been storing up for months, like water behind a dam, I loosed upon him in a single burst.

It was the old argument about the Russian. I had a carefully elaborated theory that the Slav peasants are packed full of energy, but it is the energy of the dreamer and they require a severe jolt before they will awaken and translate their moods into concrete acts. I expounded all this to Jordan at dinner in the club, and he waited until we settled down to a chess game afterward before he fired his epigram, a solid shot that hit me between wind and water. He did this immediately after capturing my queen with an impudent knight, and the combination was too much for my self-restraint.

In a word, I let Jordan have it, and I drove my opinion of him straight from the shoulder. I might have known that he would hear me with unbroken good humor.

As I finished, a little red and puffing, he suggested that we refer the argument to a referee, and when I agreed we hailed Marshal. I secretly think that Marshal inclined toward Jordan's point of view, but he wouldn't commit himself.

"Here's a lot of theory and not much fact," he said, "but a few minutes ago I was introduced to a man who has been in Russia. Suppose we go up to the dining-room and find him?"

We followed him—I was rather glad to discontinue that disastrous chess game—and in the dining-room he led us toward a table at which sat Stewart and the traveler. The latter was a small middle-aged man, and the moment I saw his round, white face, I knew him. It was Jean Paul Meneval. At that time he was quite unknown—which is, in a way, the point of this story. A rare coincidence, that meeting, for it made the third time I had run across Meneval in widely separated quarters of the earth—the first time in Naples, again in Manila, and now in a fashionable New York club!

He greeted in his usual unsmiling, earnest manner, and as Stewart and he were down to cheese and coffee, the rest of us drew up chairs around the table. Marshal announced the reason of our coming.

"I've been in Russia," said Meneval in that quiet voice of his, "but, of course, you can't expect me to settle an argument on a point so—so very inclusive. It is like prophesying the destiny of the Slav, isn't it?"

"Come," said Jordan, leaning forward in his aggressive way, "we aren't asking for a profound opinion. Put it this way: I claim there's the touch of the brute in the Slav—they have the brute mind, the brute way—they go to extremes; they're either blindly stupid or blindly violent. What do you think? They couldn't become—I mean, the mass of them—men of the world, men of culture, welt-citizens. Pardon me for being personal, but I mean they couldn't become men like yourself—a Frenchman perfectly at home in an American club."

"And I hold," I broke in, "that they can—that through their very violence they are apt to strike the spark which will light up what Jordan called their brute nature and they will see their souls."

Meneval looked at me with one of his rare smiles.

"In a way," he said, "I incline to agree with you."

"The devil you do!" cried Jordan. "Not really? Let's have your proofs!"

Jordan, after all, was a bit of an ass; but Meneval was looking into profound space while he lighted a cigarette. I noticed his hands. They were very white and slender, but the tips of the fingers were oddly blunt.

"I knew a Russian who became quite a man of the world. In fact he passed muster nearly everywhere," he said.

"Was he originally a man of the people?" demanded Jordan sharply.

"A shoemaker."

"Then he won't do as an example. A shoemaker is a skilled laborer and his work gives him time to think. I refer to the mass of the Slavs—the peasant class."

"When I describe the fellow," said Meneval, "I think you'll find his class low enough."

"Fire away."

"Ah, but it's quite a long story."

"All the better," said I. This would be a crusher for Jordan.

"We're a long way from Russia, but I suppose I should omit names," began Meneval, "or better still, change them. We'll call the man—let me see—Rotanoff. Yes, Maxim Rotanoff. That has the Russian tang, hasn't it? He was a shoemaker, as I said. He didn't work in a shop but carried his roll of leather and his case of tools along with him when he went down the streets of the village.

"That village lay in the heart of European Russia. On the whole I suppose it was at least two centuries behind the civilization of western Europe. The village held about four thousand people and the same number of dogs—all starving. If you had been in Russia you would know the place from that description. The nearest railroad was a hundred miles away.

"Nearly every one in the town worked on the estate of the rich noble—let's call him Dmitri Gorgos. In fact the village itself was built on his lands, and every inhabitant paid him a rental which varied according to the amount of money the tenant was making.

"This fellow, Maxim Rotanoff, you may be sure, was no better off than those who tilled the soil. Indeed he was their servant, in a way. He went the rounds of the houses asking for work. Often he met a man on the streets, and if the man had a boot which needed repairing he would take it off and stand wiggling his toes in the mud while Rotanoff crouched beside his little case of tools, cut the leather without much care to make it fit the hole, and cleated it home in a few minutes. Then his customer would wipe the mud from his bare foot with his hand, draw on the boot, and give Rotanoff his fee. Do you find Rotanoff's position low enough?"

Jordan made a wry face. "And this chap became a man of culture. My clear sir, it isn't possible! But wait a moment. Perhaps he was a rare example—a man who hated his place in life and bent every moment to study and fit himself for other things. Is that it?"

"Not at all," smiled Meneval, and Jordan's face fell. "No. He was quite contented with his lot. Never dreamed of anything else. His pleasures were few, but they were great to him. He was glad when spring came; he was sorry when autumn passed; he revered the village priest; even the mud did not bother him very much. Yes, on the whole I should say that he was happier in his place than I am in mine!"

He smiled again and his eyes wandered off into space. That was a trick of Meneval's. It gave him a sort of plaintive aloofness.

"Now," said I, "now for the great stroke which lifted him out of the slough!"

"The slough?" said Meneval absently. "Ah, yes; the great stroke! This Rotanoff was in love with a girl—we'll call her Ila Nadasky. He had no need of the lessons of civilization to love her passionately. She was straight and slender, with dark hair and darker eyes. She had a trick of throwing her head back to take a deep breath. At such an instant she seemed to scorn the earth."

Meneval pushed his hand slowly through his stiff, iron-gray hair. It was so coarse that it seemed to defy the brush and fell quite low over his forehead.

"I suppose she was beautiful. Rotanoff seemed to think so even after the many years. She was fifteen and he was seventeen when he told her he loved her. They decided to marry, but they waited three years while Rotanoff starved himself and saved up a few rubles. Oh, it was very little, I assure you; but if he saved a ruble in a fortnight they were content. He would bring it to her and they laughed and kissed the ruble and each other and sometimes even wept. You see, that is the Russian nature.

"After those three years—they were really terrible years of privation to Rotanoff—the glorious day came. They were mightily thrilled, I suppose, those two peasants! It was a holiday. They had waited for that so that all their friends could follow them to the church. The procession left Ila Nadasky's house. What a day! What a day it must have been for them! She had flowers twined in her hair and she carried more flowers in her hand. Rotanoff was so proud of her that his neck ached from looking sidewise at her beauty while they walked down the street. And half the village followed them, weaving in and out to avoid the little pools of water which stayed there from the rain of the night before.

"They were half way to the church when two horsemen galloped around a corner and came toward them. They were no other than Dmitri Gorgos and his eternal companion, Paul Maxady. At sight of the train they drew rein very sharply, so that Gorgos's horses slid to a halt with braced feet and sent a little shower of slush sprinkling upon Ila Nadasky. Of course she was too overawed by the nearness of the great man to cry out, but I'll wager that shower of mud on her wedding dress hurt her more than if it had fallen on her bare heart.

"Gorgos leaned from his horse a little and smiled upon her beauty. He was a rather ugly man, but his smile could make his face almost handsome. There again is the Russian for you. He asked her name, but his eyes were fixed so fast upon her face that he did not seem to hear when Maxim Rotanoff answered for her. Then he gave Rotanoff a glance, delved into the pocket of his riding breeches, and tossed the groom a gold coin.

"Of course it was a fortune to them—more than they had saved in the whole three years. They were so dumb with joy that they could not say a word of thanks, but the crowd behind marked the yellow flash of the coin as Dmitri Gorgos tossed it, and how they shouted and cheered their beneficent lord as he galloped off down a side street with his companion!

"Strangely enough when the procession came in sight of the church the noble was outside it in the act of remounting his horse. For some reason he had circled back on his course, for he had been riding in the opposite direction when he first passed them. However, it gave the crowd another opportunity to cheer, and this time you may be sure that Maxim Rotanoff led the shouting. After such happiness—after such glorious good fortune—sorrow had an added tang, and it followed quickly enough.

"When they reached the church they found the priest gone. He had left word behind—it was very vague—that business, a sudden death on the Gorgos estate, called him away, and that he could not celebrate the wedding until the next day.

"Poor Rotanoff and Ila Nadasky merely stood and stared at each other. The rest of the procession broke into groans. You see, both Ila and the groom were very popular with the peasants and every one had looked ahead for a long time to this wedding.

"Nevertheless the two had the gold coin to balance against the postponement of the marriage. They sat up late that night whispering plans for their future. And everything was given an added color and brightness by the sheen of that yellow metal. All things seemed possible to them. They spoke confidently of great sums of money which they would earn and save. Maxim Rotanoff even mentioned a thousand rubles. At that they both stared at each other in speechless excitement, and they finally broke into laughter together. There again, you see, is the Russian nature."

"And the next morning the girl was gone—that was the great stroke?" broke in Jordan. "That was what changed Rotanoff?"-

I could have throttled him, and the suggestion of a frown troubled Meneval's placid forehead.

"The next morning the girl was gone," he said coldly, "but that was not the great stroke. Her mother came running a little after dawn to Rotanoff, telling him that the girl had gone out of the house to borrow salt from a neighbor, and she had not come back and neither had she been to the neighbor's house. Of course you have guessed it already. Two of Dmitri Gorgos's servants carried her away the moment she left her mother's house. That was all.

"It was three days—three heart-broken days—before Rotanoff learned what had happened. Then he walked twenty miles to the neighboring village and spent the gold coin for a very fine revolver and ammunition."

"With which he returned and shot the dog of a noble dead," broke in Jordan. "It's as plain as day, and I suppose that was the great stroke?"

"Really, sir," said Meneval, raising his eyebrows.

"Keep still, Jordan," I said, and I wanted to wring his neck for his boorishness.

"But let's have the point!" said Jordan, "Damn it all, where does ail this lead?"

"Ah," said Meneval, "it is indeed plain that you do not see the manner of a Russian tale! The point will come soon, Mr. Jordan.

"Rotanoff came back to his village and for six months he lived as if nothing had occurred. People sometimes pointed to him and shook their heads in pity. He did not seem to heed. Several times he heard from gossips things which made his soul burn in him. Yet he would not hurry. Whenever he found an opportunity he went far from the village and practised with his revolver until he became amazingly expert. He would not miss that shot.

"When he was satisfied with his skill he began to take walks out to the gardens of Dmitri Gorgos's house. There he lurked about. Finally he met with the opportunity. Gorgos came down a path walking alone. Rotanoff crouched behind a shrub."

"Why didn't he step out and do it like a man?" growled Jordan.

"As Gorgos came beside the shrub," went on Meneval, now ignoring Jordan, "Rotanoff leveled the revolver and pulled the trigger with a practised hand. There was merely a dull click in response. The hammer fell upon a defective shell, that failed to detonate. The noble jumped through the shrub and collared the fellow. He shook him as a dog might shake a rat, so violently that the revolver dropped from his hand and his brain reeled. Gorgos kicked the weapon to a distance. There was no fear in that man.

"Then he dragged Rotanoff up the path. Paul Maxady was smoking a cigarette on the porch. There was music in the house.

"'Look at this dog,' said Gorgos. 'Music tires me, and I went for a stroll through the garden. This puppy tried to shoot me.'

"Maxady leaned a little closer and by the light which came through the open door he looked at Rotanoff.

"'Ah,' said he, 'this is the man who was to marry Ila.'

"Gorgos tightened his hand on the peasant's collar and turned him about so that he could see his face, and he kept repeating at little intervals: 'So! So! So!'

"Otherwise he said nothing. After a time he started around the side of the house, taking Rotanoff with him. They entered a dark hall and Gorgos made Rotanoff step lightly while they passed through several unlighted rooms. Finally they came to a door a little ajar which opened on a brilliant hall.

"'Look in there,' said Gorgos.

"Rotanoff peeked carefully. He rubbed his eyes and looked again. It was the first time he had ever seen women and men in evening dress. They sat about drinking brandy from very small glasses, and there were small cups of black coffee. The musicians had just finished a piece. One of the women was more beautiful than the rest. She wore a black gown and she had a great red jewel pendant in the hollow of her throat. It was a long moment before Rotanoff recognized Ila Nadasky. You see, she seemed quite at ease among that brilliant group. He turned away from the door and supported himself with one hand against the wall. He had received the great stroke, as you call it. That was the thing which changed him.

"'Do you understand?' said Gorgos.

"'I understand,' said Rotanoff, and he went back to his home in the village."

Meneval broke off and lighted another cigarette.

"Afterward Rotanoff became quite a polished man of the world. I know, for I was a familiar friend of his," he said, "and you see how low his origin was, but I am sure that if you had known him you would have accepted him as a man of culture."

"But the man—the woman—Rotanoff—Ila!" gasped Jordan. "You won't leave the story at that point?"

Meneval regarded Jordan with quiet disapproval, "The point of the story is really there," he said.

"Yes, yes! but the girl—"

"Why, if you wish to know what became of her—"

"I should say so!"

"Then I'll finish the story—for your sake!" and Meneval nodded pointedly at Jordan. "Besides, I should really explain why Rotanoff left Russia.

"Rotanoff went back to the village, as I said, with a feeling that some one had turned a search-light on his insides, if you'll admit that expression."

"A very good one—by all means!" said I, somewhat flattered.

"He suddenly discovered that he wanted to change himself. You see, he loved Ila more than ever. When a man really wants a thing he usually gets it. The richest of the villagers had a son called Misha Detin. He had gone to a college for a year or so and he had a number of books—French and German and English books and dictionaries, among other things. Rotanoff scraped an acquaintance with him and very soon was able to borrow the books.

"He read them at all hours—it was like food to him. Russians are very apt linguists. Rotanoff picked up French first, and then English. In a year he made really amazing progress. He had no exact plans for his future. He merely wanted to learn—to learn everything at a great mouthful. By the second year he was quite advanced. It is astonishing how rapidly an eager man can learn. He began to show his change. The village respected him, but was a little suspicious because he lived so much apart.

"Quite late one night there came a knocking at the door of his hut. He laid aside his book and opened the door. He could not, at first, make out the features of the woman who stood here, so he stepped aside and asked her if she would enter.

"'I have not the right to enter,' she said. Then he knew it was Ila."

Meneval paused again with that rare smile and those eyes which searched the infinite distance.

"The Russians, you know, are quite emotional. Rotanoff dropped to his knees and buried his face in her dress. He led her into the hut and closed the door and gave her place on the bed, for she looked ill. He could not speak for a time, and the tears ran down his face.

"'Ila,' he said, 'I have not prayed to God, but he has sent you back to me.'

"She smiled at him, and when he knelt beside her she let her hand wander over his face while her eyes looked into the distance. It was as if she tried to see him through the sense of touch.

"'We shall be married to-morrow,' he said.

"'Yes,' she would answer, 'to-morrow.'

"'You have thought of me a little, Ila?'

"'I have always loved you, dear little one,' she would say. You see, Rotanoff was a small man.

"He caught her into his arms and kissed her throat and lips. Afterward he stood back and asked her pardon, and she smiled at him. He took out all the books—they were ragged with his use of them—and he went over them with her. Sometimes it was hard to explain their meaning to her, but she nodded and seemed to understand—in a way. Then he kissed her hands and went away to a friend's hut.

"In the morning when he went back to his place he found her body cold on his bed. She had stabbed herself with one of the sharp, crooked little knives that he used for cutting leather. The wound was in the hollow of her throat where Rotanoff had seen the red jewel shining.

"He sat beside her all that day. In the evening he went up to Gorgos's house with the knife in his pocket and told a servant that he had important news for Dmitri Gorgos. The servant made him wait in a hall, for the master was out riding.

"Very soon he came in carrying his heavy crop. Rotanoff went to him.

"'I have brought you news from the village,' he said.

"Gorgos looked him over. 'Who is this fellow?' he asked the servant.

"'I am the man who was to have married Ila Nadasky,' said Rotanoff.

"'Ah,' said Gorgos.

"'She has killed herself,' went on Rotanoff, 'with this knife.'

"And he showed it to the master.

"'God!' said Gorgos, and struck him over the face with the butt of his riding whip.

"It must have been loaded, for it tore down a V-shaped wound on Rotanoff's forehead and knocked him back against the wall. Gorgos was panting as if he had been running. He tore open his shirt. The blood was streaking down Rotanoff's white face and he grinned in his hopeless way. He must have seemed like a poor child who presses his face against a shop window at Christmas time and yearns for the costly toys inside. What he really saw was not Gorgos but an image of the dead girl as he had seen her when she wore the red jewel; and there was Gorgos's throat, naked before him. He sprang forward and drove the sharp little crooked knife home.

"The master coughed and dropped to the floor. The red blood welled from the hollow of his throat, and as the light struck it looked like a great ruby. That was why Rotanoff had to leave Russia."

We were all silent. Meneval was staring into the void again. He pushed his hand absentmindedly through his mop of hair. As it moved back I saw a triangular scar on the upper part of his forehead.

"But that doesn't prove the main point," began Jordan in a brutally loud voice, "We were arguing—"

I got up and left the table.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.