RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

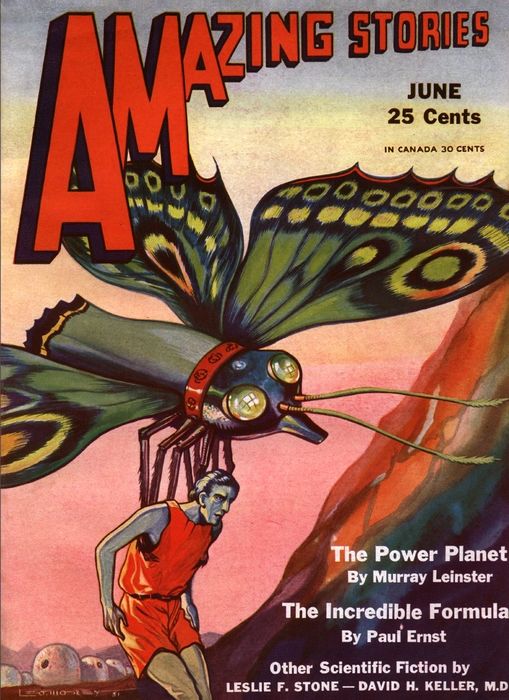

Amazing Stories, June 1931, with "The Time Flight"

If Einstein is right, and if there is a fourth dimension and time-traveling is a possibility, future generations can look forward to an era of exciting occurences. The adventurous individual, in days to come, will have unlimited scope for thrilling experiences—not without their attendant dangers, Our hero's experience is unique and the story is of absorbing interestt.

THE woman on the death-bed had been widely known for the noble ideals for which she stood, and for the determined and indefatigable way in which she had worked for them. Now, her sweet face was pale and wasted by her disease; only her eyes still held something of the old lofty fire. They were now steadfastly fixed on her son.

She had just asked her husband, the boy's stepfather to go out of the room for a moment and leave them alone together. The boy's face was puffed with the tears he strove in vain to repress, and his grief bore the air of desperate bewilderment that is characteristic of the youth at this age when confronted by the loss of someone near and dear. He stood by the bed and held her hand.

"A year ago when the doctor told me that I could not live many months, I did not believe him. Now, I know it is near. I want a last intimate talk with you, Jerry.

"I want you to be like your father. You and I have agreed that he was a wonderful man. You can't repeat what he did, starting from utter poverty and building up a fortune of millions. But perhaps your task is the more difficult. There are worse things to fight nowadays than poverty; and character is harder to build than a big estate. One day your father's millions will be yours. I want you to have them all and unconditionally. But I want you to grow up to handle and administer them wisely. These millions you must regard not as a privilege or a license, but as a heavy responsibility.

"I have left them in your stepfather's hands, but only temporarily. When he dies, they will be yours. As he is now sixty years old, you will probably get them when you are about thirty. That is early enough for you to assume a load like that.

"In the meantime, realizing that your stepfather is not a kind man nor always over-scrupulous, and that for some reason he does not love you as I do, I have arranged for you an independent income of ten thousand dollars a year. You are not dependent on him and need not live with him. Heed all the advice I have given you. Even that temporary income is dangerous in these days for a young boy with unformed habits."

The boy promised and the mother continued her advice.

"You can accomplish wonders if you want to hard enough. Anything the human mind determines upon with sufficient intensity can be done!"

When the stepfather came back into the room in response to their signal that their talk was over, there was a cynical leer on his face. For several hours they sat in the death-room; they sat on opposite sides of the room, with as much space between them as possible, and neither spoke a word. The beautiful face of the sick woman gradually grew calmer, her breathing slower, her body stiller. No one could say exactly when she died. After a long, sharp scrutiny, which convinced him that life was extinct, Ezra Hubble turned to the boy, with his face set into an expression of cruel contempt.

"All right, Jerry!" he snarled. "Now all you have to do is to wait till I die, to get your millions."

There, in the presence of Death, with the beloved mother's body still warm, the heartless old man taunted him. The boy hung his head, not knowing what to say.

"Waiting till I die!" the old man sneered. "Well, there are ways around that. Don't be too sure of your money."

The boy turned and crept out, big tears dropping down and making dark little splotches on his tan shoes.

Ezra Hubble chuckled and did not even glance at the dead woman.

"He'll never touch her millions," he whispered to himself.

Jerry Strasser, son of the famous millionaire, came to his mother's funeral, and then dropped out of Ezra Hubble's life.

EZRA HUBBLE was a mean, small man. But, with sufficient wealth available, even mean, small things can be done on a grand scale. Hubble determined on a mean, small thing, and went to great lengths to do it thoroughly.

He advertised in all the technical colleges of the country a competitive examination by which he was selecting a suitable man for a certain job that he had in mind. The examination was given at the applicant's university; the job was to begin at once. Its nature was not stated. The amount of salary was not given, but it was intimated that it would be generous. It was a queer examination, and included not only engineering theory and manual mechanical skill, but also personal history, past life and character. The matter attracted considerable excited attention in the newspapers all over the country.

Out of the two hundred and thirty-one applicants, only four made a passing grade in the examination. Obviously, these four young men must have been outstandingly able engineers. One of them was a young man whose father was a section-hand and desperately poor. The young man had worked his entire way through school, and was now deeply in debt for his education. The other three all had fair financial means. Ezra Hubble chose the one that was in desperate financial circumstances. It offered a prospect of more perfect control over his man.

HENRY JURGENSEN, the young engineer who won the competition, was promptly overrun by reporters. He was exuberantly happy over his success, after his years of discouragingly hard work. He took up his residence at the Hubble mansion at once, and spent two weeks there in conference over plans with his wealthy employer.

The case remained before the public for a long time, because of Hubble's wealth, because of the curious competition and the choice Hubble had made, and because of the refreshing personality of the winning contestant. Jurgensen was very tall and boyish-looking, with simple ways and a frank countenance. He reminded one of Lindbergh, and unconsciously one expected genuine achievement to be reported of him some day.

He seemed to be glad to talk to reporters, but could not tell them much. How did he like Hubble? He didn't know just how to answer, as he hadn't known him long enough. What was the character of the work for which he was employed? He had been asked not to divulge that, but could say that it was a piece of scientific experimentation; nothing particularly amazing, considering the things that are being done in science nowadays. It was difficult enough, but largely because of a mass of detail to be gotten through. No, it would not affect others nor have any public bearing of any kind, except for the exciting boldness of it. Otherwise it was purely a private matter.

Suddenly the item appeared that Jurgensen had gone to London. There he was picked up by the Associated Press people, and his movements reported as though he had been a Crown Prince. He spent a week making countless calls among the publishers of Fleet Street. Two or three weeks he spent among the records of the British Museum. Half a dozen times he had conferences with medical men on Harley Street. He appeared eager, interested, enthusiastic, hot upon a trail of some sort. Nieuhaus of the Associated Press caught him for a successful interview.

"I have found Filby," Jurgensen replied, some three weeks after he had reached London. "I had almost given up, when I ran across him by a lucky accident. He is an old man, but still remembers it all clearly."

"Filby," repeated Nieuhaus vacantly. "Who's Filby? Don't think I ever heard the name." Jurgensen brushed his inquiry aside absent-mindedly. "Why don't you read H.G. Wells?" he said impatiently. "Look up The Time Machine. Filby helped me find the Editor, and now I am on the Doctor's trail." The reporter eyed him in silent inquiry. "I regret that I am not able to tell you who and where these men are," Jurgensen said. "That is in Hubble's hands, not mine. But I can give you this much hope. I am confident that the old man will call the Press in on his stunt when he is ready. I've got him figured out that far."

His surmise turned out to be true, though it was many months before the Press heard from Hubble. Jurgensen came back from England with a brief-case full of notes and drawings. A modern, factory-like workshop was built on Hubble's grounds. There were draftsmen at their drawing boards and a mercury-arc turning out blue-prints. Lathes and presses were ranged down one bright side of the place. At the end was a cupola furnace, an electric furnace, and a power press. At the other end was a storeroom into which supplies were stuffed; ingots of nickel, crated lengths of ivory; a truckload of quartz.

In the middle of the floor a curious mechanism gradually took form and grew. It looked like the inside of a clock; the frame without the cover and the dial. There were many geared wheels; there were rods of crystal and bars of ivory. In the middle was a seat with quartz levers at the side, and in front an instrument-board filled with knobs and dials.

Jurgensen sat mostly at a table, over a growing pile of blue-prints. The men would come to him for the sheets; and at times he worked here and there at a machine, and a great deal at the mechanism that kept growing there in the middle of the floor. At times he looked very much worried; though there were periods of triumph for him.

Hubble came in regularly every morning, listened to the reports of progress, and then went out. As the apparatus in the middle became larger and more intricate, he hung over it a great deal; stood and stared at it, and studied it. As time went on, he became more and more excited and eager about something. Finally he got to scurrying around very busily among banks and trust companies.

ONE day, about three years after the death of Mrs. Rubble, when the whole affair had been practically forgotten by the public, the newspaper men got their invitation. They were asked to meet in Hubble's new marble Temple, a genuinely beautiful piece of work in the Greek style that an Italian architect had recently finished for him. The curious machine had been transported from the workshop, and now stood in the middle of the Carrara marble-flagged floor. A considerable group gathered, and only those who presented tickets were admitted. The group in the Temple contained, besides newspaper reporters and editors, some bankers, a Congressman, a novelist, two attorneys, and a Professor of Physics from Columbia University. Obviously, some select publicity was desired for the event. Back in a corner, shrinking from the rest of the group, was a boy of nineteen, who had also presented a ticket. He had a melancholy face, and his lips were set in a thin line.

Hubble stood up before the people and cleared his throat for a pompous speech.

"I've invited you to see something sensational," he began. "Most of you seemed willing enough to come. I assure you that you will not be disappointed.

"I have, as you are aware, a big fortune, the possession of which is very pleasant to me. I have not had it long. I dislike to think that in a few years someone else—that it will no longer be mine. You will be astonished at my announcement, that by the use of persistence and intelligence, I have found a way to beat the game, and to triumph over the passing years—" he tried to beam genially on the gathered group, but succeeded only in producing a malevolent simper. Many of them sensed an insincerity somewhere in his talk, but could not state definitely what it was nor where it lay.

"For many years," Hubble continued, "I have been fascinated by H.G. Wells' account of a trip into the future. For many years it remained a dream; but with the coming of wealth, I was able to act on my promptings. I know nothing about Science myself, but my money was able to buy the best talent available in the scientific world—" again that unpleasant flavor, thought many of his listeners. "There has been a great deal of progress in scientific theory and in means of construction since Wells' time-traveler took his trip. My young friend was able, not only to find the men who had seen the Time-Machine, but he has eminently succeeded in reconstructing it from their accounts and from his own scientific knowledge. There stands a replica of Wells' Time-Machine!

"However, before we look at it more closely, permit me to dispose of a little ceremony."

He gathered up an enormous pile of rolled-up plans and blue-prints, and stacked them on a little framework of clay bars.

"I do not feel it to the best interests of humanity that this secret be too widely used just now. If it be fitting that it should become common knowledge, I'm sure someone will succeed in reproducing it soon without my assistance. Just now, I feel that the secret should perish completely."

He pushed a button beside him. The clay bars glowed red, then white. The papers flamed up brightly, and with a rush and a blaze were consumed to ashes in a few moments. He had burned them on an electric incinerator before anyone could even protest.

"Unfortunately, my young friend Jurgensen was called away this morning on an important matter. Perhaps, though, that is for the best, for it might break his heart to see the fruits of his labors thus destroyed." Again many of his hearers detected the timbre of insincerity in his voice.

"I am about to start on a trip into the future. I have decided on one hundred years, for practical reasons. I think I can get along with the people of such a period. And my securities will still be good. I have here—" he indicated a suitcase made of steel and strongly locked—"my entire fortune. It was difficult to turn it into securities that stood a good chance of being good in a hundred years from now; but I paid well for advice in the matter, and I think these papers will be worth more then, than they are now."

His self-control was good, but he could not resist a glance in the direction of the downcast boy at the back of the room. Nor did Jerry miss the gleam of malignant triumph which that glance carried. For sheer, dog-in-the-manger, diabolical meanness, this contemptible trick of depriving the boy of his just rights without any especial benefits to himself—because here or in the future his body could only live its allotted number of years and no more—was unequaled.

With his glance of imitation geniality, Hubble climbed into the machine and set the steel case under his feet.

"I have arranged for this house to be torn down," he said, "and these grounds to be turned into a public park around this Temple, so that when I arrive, a place shall be ready for my landing.

"And now gentlemen, I wish you one and all goodbye!"

He bowed and smirked for a moment; and then his face became impassive and he busied himself with the controls of the machine. For a moment he looked up expectantly, and then pulled the crystal lever. Gears whirred, and there was a vibration throughout the machine. Then the whole thing blurred and dimmed, and man and machine were both gone!

JURGENSEN was astonished when he returned from the trip on which he had been sent, to find his employer gone and the house being torn down. However, he was a calm young man, and none of those with whom he came in contact could glean the least inkling of what was going on beneath that philosophical countenance. However, his experience must have left some sort of an emotional impress, for he turned his back upon engineering and on jobs. A year later found him well established and successful as an instructor in physics at Columbia University.

There, his attention was before long attracted to one of his students. This was a melancholy-faced young man. Who did brilliant things in the first-year physics class, and showed the makings of a first class scientist. In his second year at the university, this young man took on four courses in physics, and in his third year he was student-assistant instructor in physics. In his fourth year he knew more about physics and mathematics than most physicists twice his age. He lived for physics, and lived in it.

Jerry Strasser seemed to be a young man of melancholy disposition. It was a long time before it occurred to Jurgensen to associate him with Hubble; but eventually the memory came to him. Jerry sat and dreamed a great deal. He cared nothing for the girls, nor seemingly for any pleasures. Physics was his sole absorption. He was obviously well off financially; he spent money freely to help himself along in his chosen work, but never seemed to have a thought of spending it for anything else.

Gradually his work shaped around to a specialized subject: "entropy." Upon graduation he received a research fellowship and devoted himself to the further pursuit and cultivation of that queer abstraction.

"How did you happen to pick up such an abstract and useless thing to get interested in?" Jurgensen asked him. "There ought to be a lot more promising stuff."

"You notice my classes are full," Strasser said. "If you know enough about it, you can even make students like entropy."

"Entropy may be defined," said Strasser in his second-year lecture to his Thermodynamics students, "in general terms as the degree of distribution of the level of energy in the Universe. It is the opposite or reciprocal of the availability of energy. When we make the statement that the available or utilizable energy of any system is always decreasing (when not supplied from without) everyone understands it. Well, that is quite equivalent to saying that the entropy of any system is always decreasing.

"Entropy is useful in a limited way in Thermodynamics, in the theory of steam-engines, etc., but the practical utility of the conception is decreasing with the diminishing use of steam as a motive-power, and scientists have recently not devoted much attention to this curious cosmological principle—"

But Jerry Strasser took up this principle and developed it. When he began his work, entropy belonged in the limbo of "pure science," and as such was dry as dust to the man in the street. When he got through with it, it had an intensely practical value. "Pure science" has an unexpected way of turning out to be of concrete, practical utility to the man in the street, who has been turning up his nose at it.

During all these years of work on entropy, Jurgensen and Jerry Strasser became close friends. Jurgensen was vaguely but powerfully impressed with some sort of a hidden and irresistible purpose underlying Jerry's intense and brilliant researches. The two of them eventually decided to share an apartment, and were together for two or three years before Jurgensen found out much of anything definite about his friend. They had some good times together, and took two wonderful vacations in the mountains. At the end of their second year of companionship they were lying on their cots in a tent; outside was the moon, the fragrant pine woods, the roar of a waterfall. The well-being followed upon a day of physical activity in the open, and a wonderful meal of fish, made life seem so good and livable that they disliked to waste it in sleeping. For a while they lay in silence, in a companionship that is more powerful than one sustained by chatter. Suddenly Jerry said:

"I think the time has come...to tell you...my story." He got it out in short jerks.

Jurgensen reached over and laid his hand on Jerry's arm.

"Wait. I know you," said Jurgensen. "I was the engineer who made the second Time-Machine. I know your story, and have helped you all I could, because I sympathize. I want to help some more."

JERRY suddenly shut off his confidences and stared through the darkness toward his companion. After some minutes Jurgensen understood.

"You realize," he continued, "that I had no conception of the purpose for which the machine was being made. I took it all the time that it was pure scientific work. Now I can see the miserable meanness of it all.

"Here's how he treated me. He paid me a hundred dollars a month with the promise of ten thousand dollars when the work was done. He gave me his check for ten thousand early in the morning on the day when he departed in the Time-Machine. When I came to cash it, I found it worthless, for he had taken all his money with him. He was a remarkable specimen of despicableness in the human species."

They shook hands in silence. Jerry resumed his confidences:

"You know that much of my story, but that isn't all of it."

"I suspect that," Jurgensen replied. "You've had something on your mind all these years."

"It isn't the money I care about," Jerry continued. "That means little to me, and he could have gone to the devil with it. But my mother wanted me to have it. Not to spend. But to do things with. It was her wish. On her deathbed she instructed me how to handle it, what to do with it. Therefore, it has become a sacred purpose with me. She was wonderful—"

"But," the older man exclaimed, with a rudeness that both of them overlooked; "what do you mean? What can you do about it?"

Jerry laughed, a hard, mirthless laugh. Then he softened down.

"When she died," he breathed, "my mother said: 'Anything that the human mind determines upon with sufficient intensity can be done!' Those were her exact words. Right now I can hear her saying them."

"But—he's gone!" Jurgensen exclaimed. "The money's gone!"

"After it's been on your mind as long as it has been on mine, it's simple. If he can go into the future, so can I. He was kind enough or fool enough to tell us just exactly how far he was going. I can get there before he does, and be there to meet him. I can take my mother's will with me, and the necessary means of establishing my identity. Then I can wait until he dies. I can follow him into the future as far as he wants to go!"

"Build another Time-Machine," Jurgensen mused. "I don't know if I could—"

"Wells' Time-Machine is an antiquated, clumsy thing, both in theory and practice. It crawls laboriously along the time-dimension. Primitive. Entropy will get us a better one. We can mold Time to suit our needs and alter its very nature."

"I'm listening," said Jurgensen breathlessly.

"The entropy of any system is always increasing?" Jerry almost stated it as a question. Jurgensen merely nodded.

"This increase is irreversible?" Again as a question. Again Jurgensen nodded.

"Entropy changes are about the only absolutely irreversible reactions we know of. All other reactions, chemical, physical, even biological, not involving entropy, proceed equally well forward or backward?"

Another question; another nod.

"Therefore, the increase of entropy is what determines Time. The process by which energy is distributed over the Universe toward a common level, constitutes Time. Suppose a hypothetical being, not conscious of Time, as we are. He could recognize the Time-direction by watching the direction of entropy increase.

"Eddington has compared entropy to shuffling. A new pack of cards, with all the suits grouped together, has low entropy. Random handling shuffles them, increases its entropy. Nature shuffles things. All of Nature's activity is a shuffling. That is what determines the direction of Time.

"But suppose intelligence steps in? Though Life is most conscious of the passage of Time, yet Life is the very thing that can interfere with the shuffling process. Intelligence can sort out the suits, thereby decreasing entropy. That would reverse Time!"

Jurgensen was now sitting upright his breath coming fast. Jerry's momentary pause made him nervous.

"Go on!" he pleaded.

"Compare the flow of Time to the flow of a river. In a river, the molecules of water move in all possible directions, upstream, downstream, sidewise, up, and down. If we were among them and could see them, their movements would seem about the same in all directions; but their final resulting average is downstream. More molecules have moved downstream than up.

"Suppose we could sort out the molecules; stop those going downstream, release those going upstream. Water would be flowing uphill.

"I have been sorting quanta of energy. With a triode tube, just as you sort electrons in radio. Looks like a radio tube; but inside of it, Time goes backwards—or forwards or sidewise, fast or slow."

BETWEEN them they managed it in three years. Without the mathematical genius of Jerry Strasser, the Entropy Shell could never have been built; nor would it have been possible without the laboratory skill of Henry Jurgensen. The team of them made it successfully possible.

It was shaped like a shell for a high-powered gun. Both ends were of metal, an aluminum-tungsten alloy, and served as electrodes. The middle segment was of reinforced glass. This was an outer case. Separated from it by 100 p.c.[per cent?] of vacuum was the inner compartment, also of glass, for mechanism and passengers.

Columbia University is a powerful institution. When two members of its Physics faculty desired the use of the Hubble Temple for some experimental work, the request went through official channels from one level to another, and the permission came down by the same devious route. The Entropy Shell was housed in the Temple.

The Press and the various other representatives of the community were again assembled. Jerry Strasser felt that it would be advisable to have witnesses. He hired an investigation bureau to secure for him the names of all that had been present at the departure of the Time-Machine, and by giving a hint of what he purposed doing, readily secured the attendance of all of them, except Endersby, a reporter who had been killed in an airplane crash, and Duteau, a banker who had died of old age.

Jerry made them a timid little talk; the publicity was not to his liking and he was using it solely to protect himself; for he had hopes of returning from his trip into the Future and continuing to live as he had done before. He reminded them of his moral right to his inheritance and pointed out Hubble's trickery to deprive him of it. He showed them the operation of his apparatus, which was simple enough for a child to carry out at first trial; a lever moving in a slot carried the passengers forward or backward in Time; and a knob like the tuning-dial of a radio-receiver regulated the speed of travel.

"I have figured the exact date when he ought to arrive," Jerry said, "but I don't need it. I can skim along through Time and keep a watch over there—" indicating with his hand the spot where the Time-Machine had lain—"and when I catch up with him, I'll see him. Then I can follow him till he stops. When he arrives, I'll be right there. Then I'll stick around until I inherit the money."

A small cheer went up from the group. They were all on his side. They had disliked Hubble the first time; and Jerry's devotion to his mother's memory had made an impression on them.

The two physicists climbed into the Shell. The spectators could see them through the glass, closing the hatches on the inside, seating themselves, and working the controls. A hum came from within the machine. Then it grew misty, and when they looked again it was not there. A reporter walked over to the spot and felt out with his hands. Finding nothing, he walked all about on the spot where the Shell had stood. It was quite vacant. A great hubbub of talking broke out in the group. The men milled about excitedly, asked each other questions, argued. There were arguments as to what had become of the two machines and the men in them; whether the boy could get the money in the future century; whether they were really going into the future. Gradually they broke up into groups and pairs, and began to drift away. Suddenly some of the last ones on the scene heard a hum. Their shout brought the others running back.

Those that turned about at once, could see a dim shape taking form. In a moment, there stood the Entropy Shell, solid, material, unchanged. Within were the forms of the two men. But their positions were reversed. Now it was the younger man at the controls, while Jurgensen slumped limply in his seat. He was disheveled; there was blood on his coat and shirt; his left arm hung limp.

Jerry Strasser opened the hatch from the inside, and with his help, Jurgensen clambered painfully out, leaving a track of blood behind him. Jerry went back into the machine and came out with the steel suitcase. Every eye in the crowd stared at that suitcase; striking, familiar even after these many years. It looked as though Hubble might have just that moment set it into the Time Machine.

THE story was in the newspapers by afternoon; but it was not in the words of either one of the physicists. Both of them were too weary and dazed to talk consistently. However, the newspaper men were persistent, and gradually pieced the story together from the replies of the two men, one in his room at home, the other at a hospital.

The scheme of the entropy travelers did not work out as they had planned it. Jurgensen had a fair idea of the Time-velocity of the old Time-Machine. He ran the entropy-tubes rapidly enough to overtake the Time-Machine along the Time dimension before it arrived at its destination a hundred years in the future. They did overtake it. All about them was that emptiness, the indescribable blankness into which the trees and buildings had faded when the tubes were started; yet there, to the side of them, the old Time-Machine was beginning to take form. Jurgensen recognized his handiwork with a good deal of emotion. In the seat sat Hubble, not a whit changed in seven years. In a moment he had noticed their Shell, and jerked up his head in amazement.

Then the Time-Machine began to grow dim again.

"We're getting ahead of him," Jurgensen said. "Going too fast."

So they slowed down, and Hubble, seeing them again, began to beckon with one hand, the other on the crystal lever. They could not understand what he meant by his up-and-down gesture, and shook their heads. He grasped the lever between his knees and wrote on the back of a blank check:

"Good work. Stop. Would like to see you and talk to you."

Jerry and his companion discussed the matter for a moment. Jerry was for stopping, Jurgensen distrusted the old man's motives.

"Sooner or later we'll have to meet him," Jerry said. "Might as well be now—or here—or what do you call it."

They stopped. The Time-Machine disappeared for a moment, but soon materialized beside them.

It was night. The two machines were inside the Hubble Temple, In all directions there were tiny points of light, the lamps of a huge city. Bulks of buildings loomed in the distance, and black trees near by.

Hubble climbed out of his machine. The two companions remained within their Entropy Shell, but opened a hatch so that Hubble might look in.

"Congratulations!" he said, with a great show of heartiness. "That's a fine machine you have there. And now you will be able to inherit the money after all. Fortunate boy! The Future must indeed be interesting—"

He broke off and stared upwards as some huge, dark thing with a thousand lights soared by overhead. Afar off there were colored glows and strange rushing noises. It was indeed "interesting." Jerry was fascinated.

In spite of Jurgensen's protests, he got out to have a better look at the graceful buildings that bulked beyond the edge of the park. He exclaimed in wonder to see some sort of a machine climbing straight up into the air; a black mass of it sailed up vertically with increasing speed.

"A helicopter!" exclaimed Jerry.

"I knew they'd get 'em some day," Jurgensen said with some satisfaction.

"Wonderful!" exclaimed Hubble, and walked over to the door of the Temple in order to see better.

For a moment the three of them stood there, staring out into the strangeness of the night. Then there was a sudden exclamation from Jurgensen. Hubble had edged behind them. Now he had given a quick run and was climbing into the Entropy Shell.

Both of them turned and ran after him at their topmost speed. He had a wrench raised, and they could see that it was his intention to damage their machine. In a moment his whole nefarious scheme had dawned on them. He had attracted their attention in another direction, and was now smashing their tubes, intending to leave them marooned in a far-off future period. There was one slip in his calculations.

Jurgensen shouted, and Hubble looked up for a moment. He took the time to leer triumphantly out of the hatch at them. Jerry was running toward the Entropy Shell, but was still a dozen feet away. Before he could run that distance, Hubble could smash a tube and disable the entire vehicle. But he saw Hubble's countenance change and turn blank, and then twist up in a rage. Jerry looked around. The Time-Machine was gone, and with it, Jurgensen, and Hubble's steel bag of securities.

Hubble acted quickly. Though his countenance was ashen with fright, he shut the hatch of the Entropy Shell, sat down in the seat, and studied the controls for a moment. Jerry saw him slip the starting lever forward and twirl the speed knob. There was a hum of the transformers and a dimming. The Entropy Shell was gone. Jerry was left alone in an unknown age! His whole plan was a failure!

He felt such a sinking within him that he had to sit down on the marble floor, fearing that his knees would crumple. In a moment it had passed, and left him with only a violently pounding heart. Well, he thought, what did it matter? In this panorama of endless years and countless millions of people, what difference did it make what became of one small man?

A shout awakened him from his reverie. There was Jurgensen with the Time-Machine again, beckoning him in. They crowded together on its small seat. Jurgensen pointed to the steel suitcase at their heels.

"That's what got a rise out of him," he said.

"Now what shall we do?" Jerry asked, puzzled.

"Well," Jurgensen said, "I can operate this machine. I made it. Let's go back home—to our own time."

That seemed reasonable and they started. They had the securities, which after all was what they had started out for. What became of Hubble did not matter much. The blankness of time-travel closed about them.

In a few moments, however, the Entropy Shell slowly took form out of the blankness beside them, and Hubble's sardonic grin leered across at them. All around was blankness, emptiness.

"Now what will he do?" asked Jerry.

"If he learns how to operate the shell skillfully, he can go all around us in Time," Jurgensen said. "But let's give him a chase."

He brought the Time-Machine to a sudden stop. The Entropy Shell faded. Obviously it had a momentum which carried it on past the Time-Machine on the course that both of them were pursuing backward in Time toward their own century. However, the Shell soon appeared in pursuit of them. Again Jurgensen stopped the Time-Machine. "We have some advantage," he observed. "I know how to run this machine better than he knows how to run the Shell."

He put on full speed forward into the future. For a long time the dials spun and the little cog-wheels buzzed. How to estimate the duration of this part of the chase, they did not know, since they were independent of Time. But for a considerable period it seemed that they had shaken off their pursuer. Eventually the shape of the Entropy Shell appeared beside them. Jurgensen stopped the Time-Machine. There was a little bump as it stopped and one corner of it settled.

Evidently they had reached a very remote period in the Future. There were holes in the once beautifully smooth marble floor. The Temple was in ruins. By the broad daylight they could see that they were in a dense jungle, with ruins peeping out of it here and there. It was a dreary and frightening prospect, and they started backwards in Time again.

Hubble was apparently learning to operate the Entropy Shell, for he soon appeared beside them. He managed his machine skillfully enough to keep beside them most of the time, no matter how Jurgensen varied the speed of the Time-Machine. All around them was blank emptiness; the only things in existence seemed to be the two machines side-by-side. Except when they stopped or reversed directions, there would be flashes of strange environment, lights and trees and buildings and things high in the air. Then again emptiness.

It was a ridiculous situation, playing hide-and-seek back and forth in Time. It did not seem to them that they were on Earth at all, nor even in Space, but just alone in Nothingness. All that the two machines could do was to watch each other and jump backward and forward in Time. The two men in the Time-Machine could not shake their pursuer. The only thing they could do was to get him out of sight momentarily when they stopped suddenly. Then there would be scenes about, each time different, sometimes silent night, or night pierced by glows and flashes; sometimes the bright day, with moving bulks, smokes and scurrying people in the distance. But Hubble always reappeared promptly with the Entropy Shell, because it handled much better than did the Time-Machine.

How long they played this blindman's bluff in Time, neither of them could tell. They began to feel thirsty, and then hungry.

"We can't keep this up forever," said Jerry.

"The only thing to do is to get back home," Jurgensen said wearily. "He can't stop us. You've got the money."

"Yes, but when we get there, he'll be there to claim it. Legally it won't be mine. He's capable of any dirty trick to get it back."

They sat in silence for a long period, listening to the whirring machinery, looking occasionally at Hubble, who was glaring malignantly across at them.

"We're both supposed to have good heads," they told each other. "We ought to be able to grind out some kind of a plan."

They looked woefully at each other. They could feel that Hubble was swearing, though they heard nothing. But he looked quite as helpless as they felt.

Suddenly Jurgensen got it—the idea that solved the puzzle.

"I've been figuring," he said, "that outside, on the ground, we are two to one against him, and ought to be able to get the best of him, either by violence or by trickery. I'll stop the machine suddenly. You get ready; jump out quickly. Grab the suitcase of spondulix, and cut and run—away from the spot where we land. He'll get out and go after you. I'll disable this machine and take possession of the Shell. In the meanwhile you can circle back toward the machines, and I'll help get you away from him."

Jurgensen stopped the machine suddenly. It was near dusk. Within the Temple a half gloom prevailed, but outdoors there was still plenty of light. Jerry ran with the suitcase, out between the columns and down the stairs.

The Entropy Shell disappeared from sight for an instant, but was back again. Hubble looked this way and that, jerking his head abruptly as he did so. He discovered Jerry's absence, and saw him hurrying down the steps. In a moment he was out, pursuing Jerry, and firing a pistol after him.

Jurgensen looked about for a weapon. There was nothing loose. He wrenched violently at the quartz rod, and it snapped off with a loud crack. It weighed about four pounds and fitted his hand satisfactorily. He ran swiftly, and gained on the old man. When he was sure of his weapon, he shouted to distract Hubble's attention and spoil his aim.

Hubble whirled about, pointing his pistol at Jurgensen. Quick as a shot, Jurgensen threw his quartz rod. Jerry had stopped and turned. He saw Hubble's pistol spurt, and both of them fell.

Hubble rolled down the steps, and over the edge of the wall that held up the terrace. He landed on the concrete pavement about ten feet below, with a crunching thud.

Jerry ran first to Jurgensen. There was a bullet in his shoulder and he was unconscious. But his heart was beating regularly and his pulse was strong. Confident that his friend was in no immediate danger, Jerry ran to look at Hubble. He had to make a detour to descend and was terribly frightened lest people had heard their shouting and shooting, and would begin arriving on the scene. He found Hubble stone dead, and let him lie where he had fallen, his head and one arm sharply kinked under the weight of his body.

He took the suitcase and threw it into the Entropy Shell. Then he dragged Jurgensen over; and during the process, Jurgensen gradually came to.

"Somewhere, in some unknown future age," Jerry concluded, "there are going to be some mighty surprised people. A dead man in their park, dressed in ancient clothes, and a curious machine that won't work because the quartz rod is broken out."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.