RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

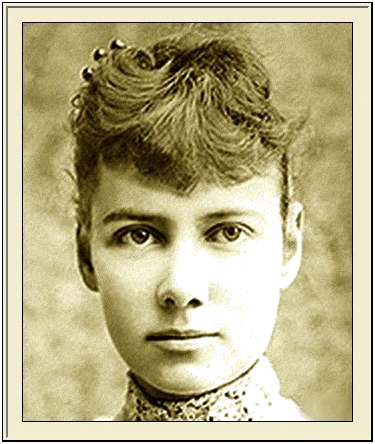

Nellie Bly

(Elizabeth Jane Cochrane)

THE strangest Christmas dinner ever given in this world, I attended last night.

Seventeen women, absolute strangers to each other, who had never met, seen or heard of each other until they met at the table, ate their Christmas dinner together.

On Monday morning the following rather remarkable advertisement appeared in The World:

LONELY MARRIED WOMAN INVITES...

A dozen other lonely women, lonely from any cause, to dine with her privately Christmas night; no reference or names required; no questions asked; good comradeship for one evening and a good appetite the only essentials. Send address to which notification can be sent as to place and hour, to B. N., box 180, World.

Heaven knows I considered myself a worthy applicant. I am possessed of a great big weary load of loneliness that made me long for the acquaintance of some one dying of the same complaint. Truly misery loves company! I didn't want to see any happy people, just some one who didn't feel especially puffed up because it was Christmas.

So I wrote a little touching note and waited! I hoped and feared, and when Christmas morning came and no reply, I decided I was entirely too lonely even to join a lonely dinner party, when a nice little messenger boy with the remnant of a nice little cigarette brought this note:

Dear Madame—

You are expected to dine today (Christmas) at the Broadway Central Hotel, No. 671 Broadway, west side, between Bleecker and West Third streets at 6:15 p.m. Please inquire at the clerk's desk for Mr. Mercer, the hotel steward. No other formality is necessary than to show this letter to Mr. Mercer, who will conduct you to the dining-room where your hostess will be present to wish you a Merry Christmas.

Of course I went. Indeed, I could scarcely wait until the appointed hour, and only the fear of looking as if I were awfully hungry restrained me from being there on the moment. As it was I was only three minutes late.

With my heart beating, a little faster than it really ought—that is for a very sedate young woman who is not in love—I went through the ladies' entrance and up a flight of stairs, where, to my embarrassment, I saw several men standing with every appearance of waiting. I began to wonder whether my hostess was a host.

But assuming an ease I was far from feeling I handed my little note to the nearest and fleshiest man.

"That's right," he said, instantly. "Go right in there."

I walked in the way he pointed and found myself in a little reception-room. A number of women were sitting around and I felt their eyes upon me. It's an awfully uncomfortable thing to be looked at by women. A man may look at a woman, as a mouse may look at the king, and one doesn't mind particularly a thing like that. It's only a man, and he'll be one of two things—either perfectly indifferent or he'll admire. There's no other course with men.

But the women! Heaven knows how they can look!

However, I found the gaze of these strange women less fearful than I have found the gaze of acquaintances. I knew these strangers were not estimating the cost of my gown or giving a thought as to who my present dressmaker may be. I knew they were not conscious of the fact that I had looked better, and I would miss the blessed privilege enjoyed by friends of making me well aware of it.

Oh, there were many little things that seemed to offer compensation!

A maid told me where I could remove my wraps and I found several women in the room fussing with their hair, just as they would at an ordinary reception, and furtively eyeing each other.

I wondered who would introduce us and what would come after. Then I followed the other women into the reception-room.

"Where is our hostess?" I heard a woman demand of a maid.

"I don't know," the maid replied.

"It is unpardonable for her to be late," observed, another drily.

This raised a laugh, but not a very merry one.

"I guess it's a joke," suggested another.

"Or she may be here and we don't know it," suggested another.

That started a new train of thought. Immediately everybody was asking everybody else whether she were the hostess. And everybody denied it.

Just at the moment when a feeling of fear began to circulate, started by some one's suggestion, "Let's get our hats and go home," a man appeared at the door, the man I spoke to when I came up the stairs.

"Ladies," he began, pulling out a gold watch and glancing at it, "dinner is on the table, and if you wait any longer it will only get the colder."

"Where's our hostess? Where's our hostess?" came from a dozen throats.

Three kept still. That looked suspicious. But in the excitement this went by unnoticed except by myself.

"I don't know who your hostess is," the man replied. "The dinner was bought and paid for, and that's all we know about it."

"It was very kind of some one," observed a pleasant little woman with white hair.

"I'll bet it's a newspaper that did it," added a plump, merry woman.

"Nellie Bly did it," said another. "I heard a man in the hall say he saw Nellie Bly come in."

How I quaked! I could disclaim the dinner, but what could I do about myself?

And what would they, especially the unknown hostess, do if I acknowledged myself?

Whew! But I was uncomfortable and my poor, old heart beat so fast that my cheeks burned. I never was more frightened, not even the time when a cold little mouse tried to sleep beneath my pillow. But that's another story—and one I will not tell till I grow older.

One poor girl was immediately pounced upon as being Nellie Bly. She said she was not and then some one said Nellie Bly did not get up the dinner, but it was the fine looking woman in velvet, who doubtless was inspired by a wish to be charitable.

She laughingly disclaimed all knowledge, and as the man started to lead the way to the dining-room we all followed.

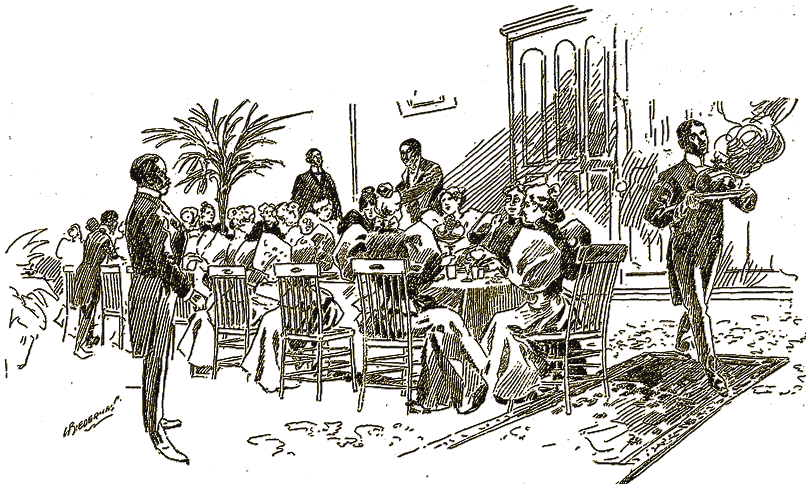

He took our invitations from us at the door. Then we found ourselves in a nicely lighted room that seemed to hold nothing but a long table with empty chairs around it.

But the table was not empty. A big green palm formed the middle piece, and leading down towards either end were too many things to be taken in by a glance.

All I really noticed were the two big brown turkeys that lay on their backs at the opposite ends of the table.

Here we found no one to receive us. We all stood helpless for a moment, not knowing quite how to proceed. Then one woman, with black eyes and hair and a gown trimmed with jet, picked up one of the papers that were on the plates:

"Listen to this!" she cried, and she read aloud from the typewritten sheet:

Peace on earth, good will to women.

Your hostess bids you welcome.

All that she asks is that you dine heartily and merrily, forgetting the world as your presence here denotes you are by the world forgot.

To-night let there be no difference between us.

We are women, that's all.

Try to be comrades during the dinner and let us part as we met.

If you are happy for one evening your hostess is more than repaid.

"How sweet!" murmured a little blond girl.

"'Peace on earth, good will to women,'" repeated the woman in velvet. "That is a kind thought. I shall keep my paper in remembrance of this evening."

We all made haste to do likewise, and the papers were folded.and bestowed in various places, a few of which were pockets.

I had a pocket, and when I felt a telltale little pencil and sheet of paper in the bottom of it I felt very guilty. So guilty in fact that when I wanted to refer to the typewritten message I was compelled to abandon the idea in fear of bringing the yellow manuscript paper to light.

Two women, the one in the jetted black, the other in a plaid silk waist, proceeded to get very friendly. They made themselves thoroughly at home, and sat down side by side. A very plump woman with an enormous pink tulle collar sat next to them. At their end of the table was a little white-haired woman with black eyes and a sweet, gentle voice.

On the little woman's left was a plump girl with small, black eyes, very deep set. Next to her sat a little woman with a sharp nose and quick tongue.

On her left was a slender girl with her hair combed straight back. She looked amused, and her right-hand neighbor said she also looked innocent.

Next to the girl and coming directly in front of the center decoration was an English woman, middle-aged, probably, and awfully clean and neat. And her cheeks were ruddy and her voice mild and pleasant.

The woman on her left was doubtless the poorest one there, counting myself out, for who is poorer than one without hope and appetite? She had false bangs pinned tightly to her forehead and she was poorly clad in black. She had never been good-looking, and now that her cheeks were flabby she was less so.

But I liked her. I always have a weakness for poor women, so long as they are clean.

The only one who looked as if she were out of dinner was seated beside my little poor woman. She was a thin, fair girl, with an appealing look and. a white tulle waist.

"When I saw her," observed the woman with the quick tongue, "I had a notion to go home and put on my best. I thought I was going to meet poor women here."

"I didn't," declared the jolly woman opposite, the one in the plaid silk waist. "If I thought it meant poor women I would not have come. The advertisement said lonely women, and I'm lonely."

"I would not think one so lively as you," chimed in the girl with straight-combed hair—the "innocent" girl—"would ever be lonely. You seem so merry that I would think you had plenty of friends."

"I am very lonely at times, very lonely," was the reply, and for an instant the woman looked sad. But the expression did not return again all evening.

But to continue with a brief description of the others. The girl next to the girl in the tulle waist was a little modest thing, with nothing to say. She smiled occasionally.

The chair at the end of the table was vacant, and beginning on the other side was a black-haired woman who had lost one of her front teeth. Next to her was a fine, intellectual-looking woman, who was, without doubt, the best-dressed woman there. She wore a black velvet waist, brightened with a little lace at the throat.

She had a fine face and a pleasant way of looking upon those present, that was enough to make one feel that, if the hostess were present, there she sat.

But the woman denied it, and she had a truthful face.

Next to her was a thin woman with very light hair, and the next chair was still vacant,

I am among those described, but which one I am I leave for my readers to guess. Those women were lonely, and I did not know them, and as they talked about me I don't want to embarrass them by letting them know just which one I was.

If you have never heard yourself talked about, try it. I tried not to listen, but I could not help myself, and I must confess I heard more about myself than I ever knew before.

The little woman next to the one they called innocent knew all about me. She declared I am elderly. Well, maybe!

"Nellie Bly is not here," she said, "but she may come yet. Did you read what she wrote in The Evening World yesterday? It was great. But then, you know she never writes anything herself. No, never! I know everything's written for her."

H'm! I thought of that when I sat down to write.

"Well, she gets a great big salary just the same," observed the woman in black jet. "She gets two hundred a week, and I guess she isn't paid that for some one else to do her work."

"What's that about Nellie Bly?" asked some one at the other end of the table.

Thereupon the woman began to tell all she knew about myself. It was news, and I listened, although I pretended to follow the example of the poor woman with the false bangs. She was there to eat.

What we ate I hardly remember. We began with blue points and something in a slender glass. One woman said it was sherry and bitters. I think it was the innocent girl. The woman in black jet said it was a cocktail.

"I've had blue points before down in the deep," she remarked, as she finished her last oyster.

The others made no remarks and soup came, and with it a white wine. I noticed that all the women drank quietly and as if it were an everyday matter.

When the fish came so many people were talking that it was useless to try to follow any conversation.

"I suppose the majority of women here are self-supporting?" I heard the woman in velvet say.

"I am," replied the girl in the tulle waist, but I could not hear if she told what her employment was.

The woman with the pinned-down bangs ate.

"I am a teacher of languages," the little clean woman with ruddy cheeks remarked. "I have an invalid husband to support."

"I had a big dinner ready," the large woman with the pink tulle sailor collar was telling the well-bred little old lady with the snowy hair. "I was just putting it in the oven when the messenger came, and so I told my girl she could go out. I would have had a good dinner home, but I was so lonely. So I came here."

"I think it was very kind, whoever invited us," the little old lady answered softly.

"It was a beautiful idea," agreed the woman in velvet.

"Wait until you see yourself written up to-morrow," warned the woman with a quick tongue.

"There's something back of it," agreed the girl on the right.

"There is a man back of the screen taking photographs of us," said the woman in jet, laughing as she said it.

"We'll have to smile and look nice," laughed the one on her left.

And the woman with the pinned-down bangs merely ate.

The door opened and a strange woman entered.

"You're late," said one.

"Yes," she replied as she took her place at the end of the table.

She was not a bit abashed or confused, and everybody instantly accepted her as one of themselves.

"That's Nellie Bly," said the black-eyed girl at the far end of the table.

I looked at the newcomer curiously. She was doubtless thirty-five or forty. Her hair was plastered in crimps down low on her forehead. Her nose was sharp and her hands showed the mark of toil.

"I was avay dis mornin' un' I didn't get mine invitation till just now," the newcomer began to explain to the modest girl, who smiled.

"That ain't Nellie Bly," declared the woman with the quick tongue. "Why, that woman can't speak English, can she, Duchess?"

This was directed to the plump woman in the plaid waist across the table.

"I see you recognize me," she observed calmly, smiling.

"I wonder if you'll recognize me if we meet some day?" the woman continued.

"I most certainly shall if we meet in public and you speak the 'Duchess' loud enough," was the quick reply.

The door was shoved open and another woman entered. She was quite well dressed and had a shrewd, bright face. She took the vacant place in front of the centerpiece.

"Are you our hostess?" some one demanded.

"No; where is she?" she asked curiously.

"No one knows. We're all guessing," some one explained.

"I'm the new woman," she offered. "I'm the only one here that wears a hat."

"But wouldn't the new woman take her hat off like a man?" inquired the innocent girl.

"Perhaps she would. Isn't this funny? Who do you suppose invited us.?"

"I like this hotel well enough," observed the woman with the quick tongue. "Waiter tell them to prepare the bridal chamber for me."

"Are you married?" asked the girl on her right.

"I've buried two husbands," she replied proudly.

"Oh, you corpse! Get away from here," cried the woman in black jet.

"I'm the corpse," said the innocent girl mildly.

"When did you die?" demanded the one in jet.

"When I married," laughed the girl.

"Now I know you," declared the woman with the quick tongue." You're Nellie Bly. Only Nellie Bly's elderly and you're young."

And the woman with the pinned-down bangs ate, merely ate.

We had fish and claret, and then we had turkey, and with the turkey champagne.

"I love this better than any man in the world," declared the snowy-haired little woman at the end of the table as she held her glass outstretched.

"Let's drink a toast to our hostess and a very happy New Year for us all," suggested the woman in velvet. This was drank speedily and heartily.

"What are men good for anyway?" demanded the new woman.

"Tickets!" shouted the one in jet.

"They're good for nothing," added the woman with the missing tooth.

With such conversation we passed the time. Not a cross or disagreeable word was spoken. Not an unkind glance was exchanged. I never in my life saw women get on more pleasantly.

After the plum pudding and pumpkin-pie one woman laughed so loudly that we all turned to look at her.

A smiling colored waiter held a plate before her on which lay three Egyptian cigarettes and three matches.

"Well, I never!" she exclaimed. Then she took one.

"I'll take this home to my beau," she laughed, sticking it in the buttonhole of her bodice.

The cigarettes were set before every woman. Eight out of the seventeen lit them and smoked. The others did not mind it in the least.

So the dinner was finished.

Afterwards we walked back to the room for our wraps. All the women were in a good humor. We were all glad we had been there. We all thanked somebody, we didn't know whom. We all wished each other a happy New Year.

Not a sneer, not a snub, not an unkind word or look. It was a dinner to remember and be proud of.

Strangers we met, comrades we were and friends we parted, to become what we had been before 6:15—strangers again.

Nellie Bly.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.