RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"YOU sent for me, and I have come."

The remark was addressed to the president of the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway Company by a very countrified-looking individual, who had just entered the presence of that official.

The president looked up, rather nonplused for an instant.

"I sent for you?" he exclaimed.

"Yes."

"You must be mistaken, sir."

"I don't think so."

"Who are you, if I may ask?"

"I am Nick Carter."

"The devil you are!"

Nick smiled.

"I have been called many names in my experience," he said, "and that one is among them. Nevertheless, I am Nick Carter, at your service."

The president was thoroughly astounded.

Like everybody else, he had heard of the wonderful Nick Carter many times, but had never expected to see him in any such guise.

He had thought of Nick Carter as a reproduction of that class of detectives to which he was accustomed; the general run of Pinkerton men, and detectives connected with the police forces of our great cities.

Instead of that, he saw a regular, out-and-out "hayseed" of the greenest type.

Nick was arrayed in his Old Thunderbolt costume, with the broad-brimmed hat, the long-tailed coat, the checkered pants, the inevitable straw in his mouth, and the general air of rusticity which created the character.

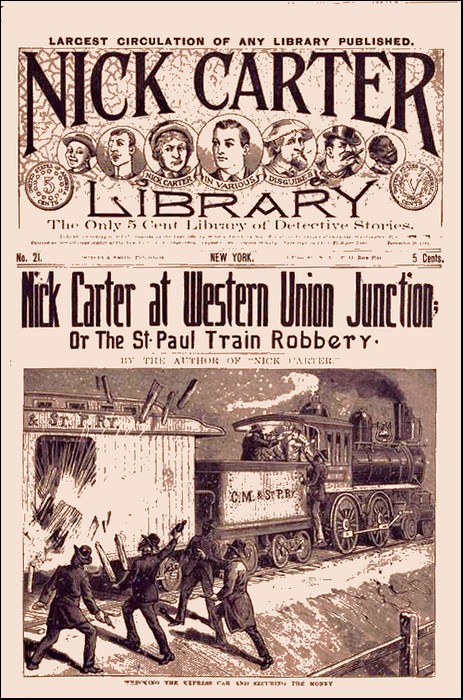

The passenger train which left Chicago for Milwaukee on the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad at eleven o'clock on Wednesday night, November 11th, had been held up and robbed a little more than a mile beyond Western Union Junction, Wis., by a gang of train robbers.

The passengers of the train had not been molested, but the express car had been broken open with dynamite bombs, and its contents rifled.

There were many and conflicting reports as to the size of the haul that the robbers had made. The general reports fixed the sum between five and fifteen thousand dollars.

The loss to the American Express Company, however, was nothing when compared with the reflection which was cast upon the railroad company by the successful consummation of such an act.

The fact that a passenger train upon one of the greatest railroads of the country should be stopped and robbed in a thickly-populated locality, and when within a very short distance of two great cities would tend to destroy the public confidence in that company, and seriously to injure its traffic, unless the robbers should be speedily apprehended and punished for their crime.

The express company was the money loser, but the railroad company was the greatest sufferer, because of the reflection put upon it.

There were already a dozen or more detectives at work upon the case, but the president of the St. Paul road had conceived the idea of engaging Nick Carter.

He had sent for Nick, and the Little Giant, who had his own way of beginning operations, had traveled to Chicago and presented himself to the official in the unostentatious garb of a countryman who was out to see the "elephant."

"So you are Nick Carter," said the president, wonder still depicted upon his face.

"I am."

"I would not have believed it."

"Nevertheless, it is true."

"Are you ready to begin work?"

"I am."

"Do you think you can find these scoundrels?"

"I can try."

"I have been led to believe, Mr. Carter, that if any man can do this work, you can. We want it done thoroughly and quickly. We want every man who was engaged in that robbery apprehended and punished, without an exception. If you succeed, and succeed quickly, you may name your own reward. In any case, we will pay well for every one of them that you bring to justice."

"How many were engaged in the affair?"

"That is a hard question to answer."

"I am aware that there have been conflicting reports on that point."

"Very."

"But you, as the chief official of the road, probably know the truth."

"The number is placed variously from two to six."

"Where do you place it?"

"At six."

"You are satisfied, then, that there were six men engaged in this robbery?"

"I am."

"Notwithstanding the fact that the general impression has been given out that there were only two?"

"Yes; it is to the interest of the railroad to represent the number as small as possible."

"Is this the first robbery of the kind that has ever occurred upon this road?"

"To the best of my recollection, it is."

"Have you any suspicions as a starter for me to work upon?"

"None that are worthy of a suggestion."

"The general conduct of the robbers would indicate that they were old hands at the business, would it not?"

"That is my opinion."

"In that case, the ringleaders, at least, came from another part of the country."

"Without doubt."

"And to do that, they must have had accomplices here."

"Why, certainly."

"And those accomplices were doubtless connected with your company in some capacity."

"That seems to be a natural deduction."

"The whole affair was worthy of the reputation of Jesse James or the Younger boys."

"It was."

"Both of those gangs are extinct?"

"Oh, yes, long ago!"

"And yet my experience has proved that you can very often trace a criminal by his past associations."

"I do not comprehend."

"I will explain. Jesse James and the Younger boys were, practically speaking, pioneers in the train-robbery business. They had regularly organized gangs, and were thoroughly acquainted with their occupation."

"There can be no doubt of that."

"Those gangs, like weeds, cast abroad their seeds, which took root in different parts of the country; and, without doubt, the perpetrator of every train-robbery to-day can be traced, either directly or through his associations, back to a membership in one of the gangs to which I refer."

"I had not thought of that."

"What evidence, in the shape of clews of any kind, is in your possession now?"

"Very little."

"Tell me that little."

"There was a slight snow upon the ground at the time that the robbery was committed."

"Yes."

"Tracks were found in the snow, made by a pair of rubbers having a very peculiar stamp upon the soles."

"Yes."

"A farm hand employed by a farmer named Worthington, has just such a pair of shoes, but he has proved to the satisfaction of Sheriff Rohan, of Racine, that they were neither wet nor muddy on the morning following the robbery, and that he had been at home all night."

"Yes."

"A mask which was worn by one of the robbers has been found. It was an ordinary pasteboard shoe-box, from a firm in Chicago. It was just large enough to fit over a man's head, and had holes cut in it, for seeing and breathing."

"Yes."

"The bombs used by the robbers, in breaking open the express car, were in many respects similar to those used in railroad construction, but were not exactly the same."

"Yes."

"A horse attached to some sort of vehicle had been standing in the snow in a grove of evergreens on the Fancher farm, a quarter of a mile from the scene of the robbery. It was probably placed there by some of the bandits for their use in escaping."

"Continue, please."

"Two of the robbers called each other 'Bob' and 'Dick.'"

"Yes."

"While they were marching Engineer McKay and Fireman Averill up and down the track, they engaged in a conversation."

"Do you know what that conversation was "

"No, but the facts are in the possession of General Superintendent Collins."

"How long was the train stopped?"

"About forty minutes."

"Proceed, please."

"A man named John Henderson rented a gun from Botsford & Wooster, of Racine, late on Wednesday afternoon. The gun is said to be of a peculiar pattern, and a number twelve cartridge, found at the scene of the robbery, fits it exactly."

"A number twelve cartridge would fit any twelve-bore gun, would it not?"

"Yes, but there is a peculiar fact in connection with this particular gun and cartridge shell."

"What is it?"

"The plunger of the gun had in some manner become chipped, so that it made a ragged dent in striking the primer of the cartridge."

"Ah!"

"The dent upon the primer of the cartridge found is a perfect fit for the plunger of the gun belonging to Botsford & Wooster."

"Then the gun has been returned?"

"Yes."

"When?"

"The morning following the robbery."

"Who returned it?"

"John Henderson, the man who hired it."

"Where does he live?"

"In Racine, at 317 Seventh street."

"Has Henderson been arrested?"

"No; he disappeared immediately after returning the gun. He has since returned, however, and is now under surveillance.

"If he was implicated in the robbery, is it not strange that he should take the trouble to return the gun at all?"

"Yes, but the fact is worthy of investigation."

"Certainly."

"A forty-four caliber Smith & Wesson revolver was found about half-way between Junction station and the place of the robbery.

"Our detective, Martin White, assisted by Detectives Broderick, Parker, Hansen, Kelly, and Hannifin, are now at work upon these clews.

"The neighboring country has been thoroughly scoured, even the farmer boys turning out to help."

"The country about there is thickly inhabited, I believe?"

"Quite so. It is surrounded by cultivated farms, and the houses are not far distant from each other. The robbery took place in sight of the station at Western Union Junction."

"Shortly after midnight, I believe?"

"Yes, at about one o'clock in the morning."

"How much money was taken?"

"I cannot give you exact information on that point, but the sum will exceed five thousand dollars."

"Now, sir, I have one request to make of you. I desire that nobody besides ourselves be made aware of the fact that I am engaged upon this case."

"Your request shall be respected, Mr. Carter, and I hope that you will succeed in apprehending the robbers."

ON the night succeeding the conversation related in the preceding chapter, the same uncouth-looking countryman, whom we know as Nick Carter, accompanied by another, equally uncouth and green in his appearance, whom we are privileged to suspect was Chick, the great detective's assistant, boarded the "stub"-train which left Western Union Junction at 10.30.

When the conductor came through to collect their tickets, Nick opened a conversation with him.

"Be yew the man that runs this train every night?" asked Nick.

"I am," replied the conductor.

"Hev yew ever been held up an' robbed, as t'other train was?"

"No, I am thankful to say I have not."

"Yew hev lots o' robberies here, don't yew?"

"I never heard of any, except the one the other night."

"Did they git much?"

"I don't know."

"I should hev thought that yew might hev seen somebody around here on this trip that night."

"I did."

"Git out! Is that so? Who?"

"Two men with shotguns got off of my train at the junction that night."

"Git out! Yew don't say so!"

"It's a fact."

"What kind o' lookin' fellers were they?"

"Well, I didn't notice them particularly."

"Git out! That's funny. I should think yew'd notice everybody wot got on an' off yewr train."

"I wouldn't have much time to collect tickets if I did that."

"Did the fellers look as if they were goin' huntin'?"

"Yes, they had guns and game-bags."

"Anything else?"

"Yes; a flask of whisky."

"Git out! Did they? What kind of a flask was it?"

"An ordinary flat whisky flask."

"Suthin' like this one?"

As Nick spoke, he drew a pint flask of the ordinary pattern from his pocket.

"Yes, it was exactly like that."

"Git out! Was it? You don't s'pose they'll suspect me, do yew?"

"No, I guess not."

"I hope not. Say!"

"Well?"

"Yew've seen other flasks just like this, haven't yew "

"Lots of them."

"Hev 'em on the train most every night, don't yew?"

"Pretty nearly."

"Gosh! I'm glad o' that!"

"Why?"

"Cause I'd hate like all git out to have some o' them Pinkerton fellers put their claws on me fer this ere thing. Say!"

"Well, what?"

"Was the flask full when yew saw it?"

"No."

"Empty?"

"There was about one drink left in it when they got off the train."

"Git out! Was there? This un's half-full; won't yew take suthin'?"

"No, thank you."

"Never drink on duty, hey?"

"Never."

"That's right; neither do I. Say!"

"Well, what?"

"Was them fellers young or old?"

"Somewhere about thirty."

"Tall or short?"

"Medium height."

"Wear whiskers?"

"Both had mustaches."

"Black ones, I s'pose."

"Yes."

"Were they full?"

"Not very, I guess."

"Do yew suppose they had anything to do with the robbery?"

"I don't know, I'm sure."

"Kind o' queer, that robbery, wasn't it?"

"Yes."

"Old hands at the business, I opine."

"I don't think so."

"Why not?"

"Well, if they had been old hands at the business, they would have blown open the safes that contained the most money."

"Didn't they?"

"No."

"Why not?"

"Because they didn't know how, I suppose."

"Git out! They didn't have time, mebby."

"They had time enough."

"Well, then, they oughter hev done it; don't yew think so, hey?"

"They didn't have the tools."

"Git out! didn't they? They had some stuff wot they call dynamite, didn't they?"

"Yes."

"Well, wasn't that wot that was for, hey?"

"I guess not."

"W'y?"

"Because they used it all up on the car."

"Wot car?"

"The express car."

"That's jest the p'int."

"What do you mean?"

"W'y it's plain enough, ain't it?"

"How so?"

"Ef they used the stuff all up on he car, they didn't hev any more left for the safes, did they?"

"Certainly not."

"Perzactly! that's the p'int, see?"

"No, I don't."

"Mebby they carried the dynamite for the very purpose of blowing open them safes, but when they found they couldn't git into the car, they had to use it fer that instead."

"I hadn't thought of that."

"Well. I admit that I'm kinder green, but it seems to me that them fellers knew their biz, or they wouldn't ha' done the job so clean."

The conductor went on his way through the car, leaving Nick and Chick to talk the matter over between themselves.

"I am satisfied," said Nick, "that if the conductor saw two men leave the car at the junction, as he states, they were probably what they purported to be, hunters and not robbers.

"In the first place, men who were going to that point for the purpose of holding up a train and threatening the engineer and fireman with shotguns, would have had too much sense to have shown themselves publicly in such a place as this, just before the commission of the crime.

"This flask that I found may or may not have belonged to one of the robbers. It probably did; but unless they filled it again, after leaving the train, it was not the property of the same men whom the conductor described.

"He noticed that that flask was nearly empty. This one is half-full."

"This makes the second flask that has been found there," said Chick.

"Yes, but one can find empty whisky flasks along any road in a thickly-populated district, and it is very natural to find them beside railroads, where they have been thrown from passing cars. That two have been found here; at the scene of the robbery, is nothing in itself, and I do not think that the other flask has any relation to the matter at all."

"Why not?"

"Simply because it was empty."

"But this one is half-full."

"Yes, and that may mean something."

"What?"

"It means, for one thing, that it was lost, and not thrown away. People who carry whisky about with them in flasks, are not in the habit of throwing them away when their contents are only half-exhausted."

"That's so."

"Whoever owned this flask, lost it."

"Probably."

"A man, in climbing over the coal on a tender, might easily lose such a thing from his pocket."

"Have you examined the flask carefully?"

"Yes."

"Is there any mark upon it?"

"Only on the cork."

"What did you find there?"

"A part of a label, such as druggists sometimes paste upon corks, after filling a bottle with some prescription."

"Is there any name upon the label?"

"The last four letters of one, and the last two letters of the city where he is located; 'b-e-l-' represents the name, and 'g-o,' the place, so that it is doubtless a druggist who does business in Chicago."

ON the following morning the detective left Chick at Racine to look up certain points connected with Henderson, and other matters there, and with instructions to take an afternoon train for Chicago, for the purpose of finding the druggist whose name ended with the letters "bell."

Nick himself went once more to the scene of the robbery.

His disguise was that of an ordinary young countryman of the neighborhood, whose curiosity had led him to the scene.

He would have given a good deal if he could have been at the scene of the robbery on the morning immediately following its enactment.

Now, nearly a week had elapsed, and hundreds of men, detectives and spectators, had ransacked every foot of the ground over and over again, until every trace which the robbers might have left had doubtless been totally obliterated.

It is true that on the preceding day he had found the half-empty whisky flask, partially concealed beneath an old tie which had been thrown out at one side of the road, eight or ten feet from the track.

The flask might have been hidden there by someone since the robbery, or it might have fallen from the pockets of someone, and rolled without being broken, into its temporary hiding-place. It might have been there an hour, or a week, or even a month, when he found it; and of itself it was unimportant, inasmuch as there was no way of tracing it to its original owner.

Still there was always the possibility that something might have been overlooked, no matter how many searchers had failed to find it.

But it was not particularly to search around the scene of the outrage that Nick visited the place that morning.

A dozen or more detectives, assisted by several scores of natives, had spent many days in searching for clews; but they had thus far failed to find anything of particular importance.

There are two distinct classes of clews, notwithstanding the fact that the average detective never searches for more than one.

There is the material clew, which is always found at the scene of a crime, and is in some way directly connected with it or its perpetrators.

It may be a button, a bottle, a weapon, a tuft of hair, a remembered conversation, or any bit of substance or coincidence which happened at the scene of the crime.

It is always contained in one article, or is the fruit of the recollection of one man, and it always points directly at the act which it is desired to elucidate.

The other class of clew might be termed latent, inasmuch as it is a bit of mosaic which amounts to nothing of itself, but which, when fitted to other bits, equally irregular in shape as well as in meaning, forms a symmetrical whole, and tells a complete story.

Nick arrived upon the scene too late to waste his time in a search for material clews. Besides, there were dozens of others who were constantly seeking them.

He therefore started out upon an entirely different basis.

After a half-hour's inspection of the track in the vicinity of the robbery, he turned his face toward the Worthington farm-house, where he was soon in conversation with the young corn-husker who owned the rubber that was like the impression which had been left in the snow by one of the robbers.

One glance at the young man's face satisfied Nick that he was not implicated in the affair, and he was strengthened in this belief as he proceeded with his investigations.

The young man in question was engaged in cleaning a harness in the stable when Nick approached, and he looked up and nodded familiarly when the detective accosted him.

"Kin I git a horse and saddle here?" asked Nick.

"I don't know; mebbe so," was the reply. "Want to go far?"

"No; eight or ten miles."

"Don't want to buy one, do you?"

"I hadn't thought of it."

"I've got a horse I'll sell you."

"For how much?"

"A hundred dollars."

"Is he any good?"

"Sound as a dollar, but a perfect devil."

"Have you got a saddle, too?"

"Yes, an old one that I'll sell for ten dollars."

"Fetch the horse around, and let me have a look at him."

"There he stands, right there."

"Big fellow; ain't he?"

"Yes, and fast too."

"Easy rider?"

"Easy as a rocking-chair."

"But ugly, eh?"

"Uglier'n Satan. He's all right, though, after you get on him."

"How old is he?"

"Comin' six."

"Will you warrant him just as you represent him?"

"Sure."

"Where is the saddle?"

"Hanging there."

"Tell you what I'll do."

"What?"

"I'll give you a hundred dollars for the outfit."

"It's a bargain, stranger. What's your name?"

"Perkins."

"Stranger round these parts, ain't you?"

"Yes, I belong up north, about twenty miles. I came down here to see where the train was held up."

"Did, eh?"

"Yes, You're the feller, ain't you, that owns the rubbers I heard talked about?"

"I s'pose I am."

"Kind of a close shave for you, wasn't it?"

"Pretty close, but Worthington knew I was in the house all night, so I didn't have no trouble."

"How did he know that? A feller might slip out after the other folks were in bed."

"We heard the noise of the bombs exploding, and I went to his room to ask him what he s'posed it was."

"Well, you couldn't have been here and down there at the same time very well, could you?"

"Not very well, no."

"Where'd you buy them rubbers of yours?"

"Of Ellis Brothers, in Chicago."

"When?"

"About two weeks ago."

"Ever have any tramps around here?"

"Sometimes."

"Seen any lately?"

"Yes, one came along here the day before the robbery."

"Beggin'?"

"He asked me for something to eat, and I got him some doughnuts."

"What kind of a looking feller was he?"

"A regular out and out tramp."

"Which way did he go when he left here?"

"Toward the Junction."

"The robbers had a horse tied up in the woods near Fancher's, didn't they?"

"There was a horse there. I don't know whether it was theirs or not."

"Well, saddle up that horse, and I'll give him a try now."

"He's the devil to mount, Mr. Perkins, but when you get on him he's all right."

"I guess I can mount him. Have you got another horse handy?"

"Yes. Why?"

"I'd like to have you ride up as far as Fancher's with me."

"Why?"

"Oh, just to see how this nag goes, and to show me the place where the robbers tied their horse."

"All right."

Nick handed over the hundred dollars which the horse had cost him. Then with one quick spring, before the animal could get out of the way, he seated himself in the saddle.

A moment later, and the two were galloping along the road toward Fancher's farm, nor did they pause until they were within the confines of the grove where an unknown horse had been picketed, sometime during the night of the train robbery.

Nick leaped from his saddle, and handing the bridle to his companion, began a thorough investigation.

So many searchers had been there before him, that he had little hope of finding anything that would be worth the name of a clew.

Nevertheless, he poked carefully round under the snow and among the twigs and withered needles of the evergreens.

Suddenly he paused and picked something up from the ground.

It was the stump of a cigar that had been two-thirds consumed, and near it was a burned match of the parlor variety.

"Both of these were thrown away at about the same time," he reflected, "for I find them very near together. The man who tied the horse here that night is the man who threw away that cigar stub, and the reason is obvious.

"The horse was brought here, and this cigar and match were thrown away before twelve o'clock that night," he said aloud to his companion.

"How do you make that out?"

"Simply because the snow did not begin to fall until midnight. Am I not right?"

"Yes."

"Very well, the horse stood here before the snow began to fall, and this cigar was so covered that I am certain that it fell before the flakes."

"That's all right about the cigar, but how do you know that the horse was tied there before it snowed?"

"By the impressions that his feet made upon that soil. If he had been tied here after the snow began to fall, there would have been comparatively very little impression left of his presence."

"How do you make that out?"

"Have you ever noticed a horse when he was standing alone in a storm?"

"Often."

"Haven't you also noticed that in that case they always stand very still?"

"That's so, sure."

"This horse was uneasy until it began to storm. Then he stood quietly. But very little snow has been crowded under the twigs, and his first droppings were made before it snowed that night, I am positive."

"Well, you see things that nobody else would."

"This cigar was extinguished before it was thrown away, also. If it had been lighted, it would have left some evidence of that fact where it fell. The snow covered it completely, and in that compact manner that it has when it falls upon and covers a thing, instead of being pierced by it."

"Oh!"

"What kind of matches do you use in this neighborhood?"

"The ordinary kind."

"Parlor matches?"

"No; sulphur matches."

"Exactly. This is a parlor match, you see."

"I do—yes. What of it?"

"The man who threw that match away, probably did not belong around here."

"Why?"

"Because he used a parlor match."

"Oh! You think if it had been me, for instance, I would have used a common sulphur match."

"I do."

"Well, maybe you 're right."

"I think I am. I am very much obliged to you for coming up here with me. If the horse doesn't suit, I will bring him back to you."

"All right. Good-by."

"Good-by."

Nick spent some further time in examining the ground around the place where the horse had been tied; he poked around among the needles at the base of the tree-trunk, and with his knife chipped off little pieces of hardened pitch and bark from the tree itself; then he took his way toward the Fancher farm-house, which stood on a rise of ground, less than a quarter of a mile from the spot where the train was held up.

He wanted to learn more concerning that tramp, of whom the young corn-husker had spoken, for he knew beyond a doubt, by what he had discovered in the grove, that the robbers had been upon, or near the scene, shortly after dark that night; that they had been at the place long before the time when the robbery was committed.

The tramp might prove to be one of them, or at least might possess some knowledge of their presence.

NICK had learned several points while in the evergreen grove that he did not choose to reveal to the young corn-husker.

Indeed, he had not meant to reveal anything to him, except what he did, and that was for a purpose.

While he did not believe him to be really guilty of participating in the robbery, there was always the possibility that he might be mistaken, or, that the corn-husker might possess knowledge concerning the affair, which he was afraid to reveal.

If that was the case, his experience in the grove might startle him into running away, or into making admissions which would be useful.

Nick's habit was to suspect nobody without good cause, but, at the same time, to put to the test everybody who could by any possibility have guilty knowledge.

He was not long in reaching the Fancher farm-house, where he was soon talking with the farmer about the weather, the crops, cattle, and politics.

At last the robbery was mentioned incidentally and Nick expressed his opinion that two men could not have performed the deed so successfully.

"I know there were more than two," said Fancher.

"You know it!" exclaimed Nick.

"Yes."

"How do you know it?"

"Because I saw 'em."

"What! You saw them, while they were at work?"

"Yes."

"From the house, here?"

"Yes."

"Haven't you gotta a gun?"

"You bet I have, stranger."

"Well, what good is it?"

"What good is what?"

"Your gun."

"Why?"

"I'll tell you why. If I'd had a gun, and had been where I could see what was going on that night, I'd have drawn a bead on one of them fellers, and don't you think, I wouldn't."

"It's just a leetle too far away, stranger," said the farmer, dryly.

"You could have gone nearer."

"Yes, I could; and I tried to. The fact is, I've gotta sick wife, she was sick that night, an' when I grabbed my gun an' started for the door, she grabbed me, see?"

"Wouldn't let you go, eh?"

"Not a step."

"Well, what did you see, anyhow?"

"Saw the whole business."

"How many robbers were there?"

"Five, at least. I could count eight men around that express car at one time, and there might have been more on the other side. The engineer, fireman, and express agent would be three, and five strangers would make eight."

"True."

"I'll tell you what I think."

"What?"

"I think that there were a lot of 'em in the thing. Some of 'em kept dark, hiding away while the others did the work. I hear lots of talk about the robbers being amachewers, but I tell you, they were old hands at the business."

"Just what I think, Fancher. How'd'you happen to see 'em?"

"Heard the bombs. What's your business, stranger?"

"I'm lookin' for a hoss that was stolen t'other day, up my way."

"What kind of a hoss?"

"Sorrel with a white star on its forehead."

"White star, 'r white face?"

"Well, pretty near a white face."

"Three white feet?"

"Yes, that's the horse."

"How big was he?"

"About fifteen hands."

"What kind of a wagon?"

"I don't know. The thieves used a wagon of their own, but one tire was part way off of one of the nigh wheels. You talk just as though you'd seen him."

"I think I have."

"When?"

"Why, come to think of it, the very afternoon before the robbery."

"Is that so? Where?"

"Drivin' past here."

"Well—well! Which way?"

"Toward Racine."

"I shouldn't wonder if that was the horse I am after. Who was driving?"

"There was a man an' a woman in the wagon, which was an old buck-board."

"A man and a woman, eh?"

"Yes."

"Bundled up, pretty well, I suppose."

"Yes; 'twasn't so awful cold, either."

"Haven't seen the horse since, have you?"

"Narry a see."

Nick changed the conversation to other topics for a few moments. Presently, he said:

"I heard about a tramp that was along here that day, and he rather answered to the description of a tramp that I thought might have had something to do with stealing the horse. Did you see him?"

'Yes, I remember. But it was two 'r three hours before I saw the horse; and besides, the tramp came from the other way."

"From toward Racine, eh?"

"Yes."

"Then he couldn't have been the same one."

"Hardly."

"Did he stop here?"

"No, I met him on the road."

"Did he say anything?"

"Asked me how far it was to Milwaukee."

"Regular tramp, wasn't he?"

"Yes, except his boots."

"What about his boots?"

"Well, he was the first tramp I ever saw that had on a new pair of rubber boots. I noticed 'em because he had his pants over 'em, instead of having 'em tucked inside. I guess he stole 'em at some. farm-house lower down."

"Probably."

Nick then left the Fancher farm and went on along the road, away from Racine.

He rode slowly, thinking deeply.

"I have struck a pretty good clew," he reflected, "that is, acting upon the hypothesis that the horse in the grove belonged to the robbers, of which there is no doubt.

"First, I know the horse was sorrel in color. A horse, standing at a tree, will always rub and scratch his neck, if left long enough to himself. I found sorrel hairs stuck fast in the pitch on each side of the tree; hairs from the mane on one side, and short hairs from the neck on the other, proving that the horse's mane was trained on the left side.

"On the front of the tree, I found a single white hair, proving that the horse had either a star, or a white face. I know he was about fifteen hands high, by the height from the ground to where he rubbed the tree.

"Good! Now second. Fancher saw the horse and tells me that he had a white face and three white feet; that he was hitched to an old buck-board, which fits into my find because the wagon must have been old to have a tire so badly out of place. I found that fact where it went across the ditch to get to the grove.

"The man and woman being together in the wagon, was intended by the robbers to avert suspicion when the rig should be remembered after the looting of the train; and it worked, too.

"Now, for a bit of summary:

"I believe that the robbery was planned and carried out by a regularly organized gang of train-robbers, who selected two of their most experienced men to do the job.

"They arranged all of their plans, so that nothing would upset them, and then they went to work, and succeeded partially.

"They knew, as well as the messenger on the train, that there were two steel safes in the express car, which contained a large amount of money, and it was those two safes that they were after.

"It was for that purpose that they carried the dynamite bombs. They meant to use them to blow open the safes.

"The robbery was originally planned in Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, or some such locality, but the basis of their operations was Chicago.

"Good! I am getting at it.

"Two men were selected to do the work, two more to act as assistants, and two more who were on hand, ready to jump in and help, if help was needed. That makes six.

"One man went to Milwaukee, and there he either hired or bought a horse and buck-board to drive out into the country. He may have been disguised as a woman when he hired the horse; he may have assumed a woman's garb after driving out of the city; or it is possible that the party who went there to hire the horse was really a woman who is in league with the robbers.

"One man went to Elkhorn, Springfield, Burlington, Truesdell, or some equally contiguous locality, where he disguised himself as a tramp and walked the rest of the way to Western Union Junction. It was his duty to meet the party with the horse somewhere between Western Union Junction and Milwaukee, probably near Oakwood.

"Having met, they turned off on a side road, compared notes, the tramp became an ordinary-looking countryman, or he may have played the woman's part from that point, the paraphernalia being in the wagon, ready for him.

"That is more likely; let us decide that the tramp became the woman whom Fancher saw.

"They drove down past here, toward Racine, just before dark to look the ground over, and to find a good place to leave their horse while they were at work that night.

"When nine or ten o'clock came, that night, they drove back again, for the people hereabouts were in bed by that time.

"They went into the grove, tied their horse, and sat in the buck-board, smoking and talking and chewing tobacco, until the time came for them to go to work.

"They were the fellows who were to do the job, and they knew that they would have help if any should be needed.

"One of them, the tramp, wore rubber boots. They happened to bear the same stamp on the soles, as those on the rubbers owned by the young corn-husker, and may have been bought at the same place in Chicago.

"I have that address if I need it.

"Two more came down on the 'stub'-train, and they were the ones who were ready to assist in case of need. They had guns and game-bags, and were supposed to have been, or to be going, hunting. They took no part in the robbery, but were hidden near by with their guns ready in case any show of desperate resistance was made. None was, more is the pity, and they had nothing to do but look on.

"When the work was done, they got away to Racine, and furnished the only clew that the detectives have lit upon which amounts to anything. Careful inquiry at Racine, would, I think, establish the fact that some hunters bought game at one of the markets either the evening before the robbery, or the morning after it. Those fellows walked the ties, found their game, and nobody noticed them.

"Now for the other two: They took passage on a parlor car from Chicago for Milwaukee. They were among the first to hide their valuables when the train was held up. After that, they were brave, and went out to see what was going on.

"They saw the engineer, etc., as they were being marched along the track, and growing more curious, they went as far as the locomotive, or, perhaps farther, there being no danger at the moment.

"Somewhere, they found the packages that the real looters had dropped for them. They picked them up, concealed them under their coats, walked back to their car, went into the smoking-room, perhaps, and wondered why the railroad company did not arm its employees."

NICK did not cease his reflections as he rode along.

He believed that he had hit upon the real solution of the mystery.

To catch the land pirates was another thing.

"If any resistance had been made, there would have been murder committed," he continued, still thinking out the probable solution. "The attack would have come from the side of the road, and those who resisted would have thought that there were a dozen or more hidden there, instead of two.

"No resistance was made, and it is fortunate that there was not.

"The two who came in the buck-board boarded the train at the junction, held up the locomotive when they reached the right spot, and proceeded with the work.

"Everything had been carefully planned beforehand. The guns were double-barreled breech-loaders, and, with the stocks taken off, could easily be placed under the seat of the buck-board. They put them together when they got ready to use them.

"When they left, after the robbery, they left as they came.

"They returned to the grove, and drove away.

"The woman-disguise was reassumed by one of them, and he wore it until well out of the neighborhood.

"Then he made up as a tramp again, bade his friend good-by, and started out to walk, once more, begging his living as he went.

"We will say that his partner dropped him somewhere just beyond Waukesha, and that he followed the main highway from there to Madison, where he could easily disappear.

"Good! I will look that point up later.

"Now, if there is anything in my theory, at all, we have the party arranged in this way:

"All start from a given point, all meet at Western Union Junction, and all meet again at the original given point for a divvy.

"Two travel from Chicago on the train that is to be robbed, their business being to find the packages of money which the others drop for them to pick up, to return with the cash to their car, to look horrified, and to play the role of traveling gentlemen.

"Two go hunting, and manage to be at the spot at the proper moment, having shown themselves in various places in the character of sportsmen, so that in case of arrest on suspicion, they are prepared to prove that they are harmless, have been in the neighborhood several days, and are really what they seem.

"Two—those who do the real work—separate. One goes to Milwaukee, perhaps by way of La Crosse or Prairie du Chien. He waits there until the proper time, perhaps hiring the horse for several different trips before he takes the real one. He always gets back before dark until the last trip, when he announces that he will probably be detained till morning, or, at least, very late. Therefore, nothing is thought of the fact. He has prepared the way.

"The other plays the tramp. He reaches the right spot at the right time. He goes to Worthington's to get a bite to eat; and leaves his foot-prints there when the robbery has been done, not knowing that the young farm-hand has rubber-soles like his, but just as a chance misleader that can be quickly done.

"Then they drive away.

"If they should be stopped as suspicious characters and their wagon searched, no money is found in their possession, and they have a story prepared. One of them has a character, which he has established in Milwaukee, where he hired the horse—the other is a stranger to him, whom he has picked up on the road.

"Nothing is easier—nothing simpler.

"The two hunters part at Racine, and go their separate ways.

"The two gentlemen (!) part at Milwaukee; one to return to Chicago, the other to continue on to St. Paul.

"The two real looters part upon the road in the dark; one to tramp it to Madison, and the other to return his horse to the stable in Milwaukee, to announce that he is through for that trip, and to set out for some distant place, kindly remembered by all who knew him as a genial fellow.

"The thing is done!"

It cannot be denied that Nick had conceived a very plausible story, and a very skillful one.

Few detectives would have thought of it, or of any point connected with it.

To Nick, it presented many features that were worthy of investigation, and he rode on for Milwaukee.

It was dark when he put his horse up, but he asked the stableman a few pertinent questions about a sorrel horse with a white face and three white feet.

However, he got no satisfaction there.

At the hotel agreed upon between him and Chick, he found a message, and, an hour later, Chick was there.

"Find the druggist?" asked Nick.

"Yes. Tarbell, La Salle street."

"Did he know anything about the label?"

"Knew that it was his, but that was all."

"Find out anything worth using?"

"Not a thing."

"Thought you wouldn't. I want you to take the night train for Racine."

"Yes."

"Inquire for two hunters—those who got off the 'stub'-train at the Junction."

"Yes."

"Find out if hunters bought any game at any of the markets, the day before or the day after the robbery. Find the hunters, if you can. If you get trace of them, follow them, if it takes you to Winnipeg."

"Correct."

"That's all. You've got twenty minutes to catch the train."

"I'm off."

"Good-by and good-luck."

"Thanks."

The following morning Nick began a tour of the livery stables of the city.

He visited seven before he found a clew.

Then he struck one.

"Do you own a sorrel horse?" he asked of the proprietor.

"I do."

"White face?"

"Yes."

"Three white feet?"

"Yes."

"Habit of scratching his neck against posts when you hitch him?"

"Yes, confound him!"

"That's the horse my friend was talking about. He said he was a dandy. I wanted to hire a horse and he sent me to you."

"Oh, you mean Mr. Gray!"

"Yes."

"He used him a good deal and liked him."

"Isn't afraid of a gun, is he?"

"Not a bit."

"Gray is a great fellow to carry a gun with him when he's riding."

"Yes; and he generally shoots something, too. Most always brings some game in with him."

"Did he the last time?"

"No; he said it got dark too soon for him that day."

"Horse have any pitch on his neck the next morning?"

"Yes; in his mane. Why?"

"Simple curiosity. I say, is that the buck-board that Gray used?"

"That one in the corner?"

"Yes."

"It is, yes."

"Too rickety for me, I'm afraid."

"It's old, but it's sound."

"Gray said one tire was a little off."

"Well, a leetle mite—on the nigh-hind wheel."

"Exactly."

"It's all right to use."

"Well, if you'll put the sorrel into it, I'll take him out."

"Going far?"

"Over toward Madison."

"Be back to-day?"

"Can't tell."

There was a triumphant smile on Nick's face as he drove out of the stable, with the very horse that the train-robbers had used in working their scheme.

He had told the truth when he said he was going "over Madison way."

He was.

He was going tramp-hunting.

His solution of the robbers' plans had worked well thus far, and he believed that he would strike the trail of the tramp somewhere in that neighborhood.

Before leaving the stable, however, he asked the proprietor a few carefully-worded questions about Gray, his general appearance, _etc.^

Nick was hot upon the chase now, and he felt confident that a day or two would develop splendid results.

With Chick on the track of the hunters, and himself after Gray and the tramp, there were large chances of finding something.

NICK'S plan for getting upon the track of the tramp was a very simple and at the same time effective one.

He had asked enough questions of the keeper of the livery-stable, to give him some general ideas of the roads that the man who had called himself Gray was in the habit of taking.

He knew that it might consume two or three days before he could get track of the man that he was after, but once upon his trail he felt certain that he could track him down much easier than he could follow Gray, or any of the others.

Besides, he felt that the tramp was more certainly implicated in the affair them any of the others, with the exception of Gray.

During the first day, he covered three different east-and-west roads, by using the cross-roads, and going in a zigzag course.

Six miles straight west on one road, stopping at every house, then over a cross-road to the next one running east and west, and then back along those six miles; then farther south to the third road and twelve miles on that, six miles back on the middle road and twelve to the westward on the north road.

That was his plan, and it covered all the roads that the tramp would have been most likely to take, if the detective's theory was correct.

It was not until the afternoon of the second day that he hit upon a genuine clew.

Many of the farmers had seen tramps passing along the roads, but none of them had seen the right one.

However, on the afternoon of the second day, he struck a clew.

His usual course of questioning was precisely that which he followed, when, upon entering a spacious door-yard, a keen-eyed young man approached.

"The farmer's son," mused Nick.

"Fine day, but a little chilly," he said, as the young man drew near.

"Yes; been driving far?"

"Yes; from Whitewater, to-day. I'm taking subscriptions for a new monthly magazine. Are you much of a reader?"

"Not much. Reckon I won't subscribe for anything to-day."

"I'm sorry for that. You look at my horse just as though you had seen him before."

"I have."

"Is that so? Where?"

"I've seen him twice before."

"He belongs in Milwaukee."

"Yes; so the other man said."

"What other man?"

"A lightning-rod agent who was along here sometime ago. "

"Named Gray?"

"Yes."

"I know him. But, say, when was the second time you saw the horse?"

"About a week ago?"

"Gray have him, then?"

"Yes."

"Where was that?"

"On the road about a mile farther east. I had been to a dance and was coming home."

"Early in the morning, wasn't it?"

"Just daylight. Gray overtook me. I recognized the horse when I saw it coming."

"And caught a ride, eh?"

"Yes; had to sit on the hind ex, though."

"How was that?"

"He had a man with him."

"Ah! did, eh?"

"Yes."

"They went right past here, I suppose."

"Yes."

"Was it somebody you knew with Gray?"

"No. He was a no-good-looking chap."

"Tramp?"

"Well, not exactly. You seem to be interested in him?"

"I am. Have you heard of the train-robbery at Western Union Junction, young man?"

"I should say so.'

"Well, one of the robbers started off this way on foot, and I'm trying to get on his track. It might be the fellow who caught a ride with Gray."

"Maybe. They were strangers, anyhow."

"Why?"

"Well, they didn't say anything much to each other, and that little showed they were strangers."

"Describe the tramp, won't you?"

"Well, he was about my height and build, and he wore a black mustache. He hadn't been shaved for a week, either."

"See anything peculiar about him?"

"Just one thing."

"What was that?"

"The wind was blowing a gale that morning, and his hat blew off. Being on the ex, I jumped down and got the hat, and when I handed it to him, I noticed that he had a bad scar on the left side of his head, just over the ear."

"High enough up so the hat would hide it?"

"Yes."

"Is that all that you noticed?"

"Yes, except the expression of his eyes. I never saw such eyes."

"What about them?"

"They were small, and set uncommonly wide apart. They glittered, too, when they looked at you in a queer sort of way. I can't describe them, only I remember thinking that a man, with a pair of eyes like that, must be a bad egg."

"Did he thank you when you returned his hat?"

"Yes."

"What did he say?"

"'Much obliged.'"

"What did he say when it blew off?"

"He swore."

"What did he say?"

"He said 'damnation, there goes my hat!'"

"Ever hear of him since?"

"No."

"Gray talked, I suppose?"

"Oh, yes; but 'twas all about lightning-rods."

Nick reflected a moment.

"Where do you think they were going?" he asked.

"To Madison."

"Why?"

"They were on the straight road for Madison."

"You won't repeat anything that we have said to-day."

"Certainly not."

Nick drove on.

He was on the right road, and he felt reasonably certain that Gray would leave his accomplice at the next four-corners, and that he need not begin to question anybody until he passed that point. He had to drive about three miles before he reached a house beyond the next corner.

"Here is where my tramp would have tried for some breakfast," he thought.

"Hello!" he shouted, as he drove up to the barn door.

A man came out, and asked what he wanted.

"I want to know if a tramp stopped here to beg his breakfast, a week ago last Thursday morning," said Nick.

"A week ago last—yes, yes! I remember now. Yes, one stopped here then. Why?"

"I am an officer, and I'm looking for him."

"Oh! What for?"

"Stealing a coat and a pair of rubber-boots."

"Rubber-boots, eh? The coat he had on was old enough, but he did wear good rubber-boots."

"Did you give him his breakfast?"

"Yes."

"Did he talk any?"

"Not much."

"Say where he came from?"

"Watertown way."

"Say where he was going?"

"Yes; Janesville."

"Thanks; did he take his hat off while he was here?"

"No."

"All right; good-day."

Nick drove on before the farmer could question him.

He figured how far the man would walk before he would begin to want more refreshments. Then he began calling at the houses again.

At the second one, he found where the tramp had got his dinner, and moreover that he had said there that he was going to Madison.

The farmer was on the point of starting for Madison in a-buggy, and offered to let the tramp ride.

The offer was accepted, and the tramp was carried into the city.

Nick's horse was tired out, and so he "put up" at the farm-house for the night, spending the evening in talking with his host and picking up every scrap of information that he could concerning the tramp.

He learned a good deal that was valuable, and that would be of material assistance to him in the chase, and the following morning at daylight he started for Madison.

His first move after entering the city was to go to a telegraph office. There he wired the clerk of the hotel where he had stopped in Milwaukee to forward any message that might be awaiting him, and he was soon in possession of one from Chick, which read:

"Having considerable success with ducks. Expect to leave here immediately."

"Good!" mused the detective. "Chick has struck one trail and I another. If we don't meet somewhere before the end of a week, I am greatly in error."

Next, he sent the horse and buck-board back to Milwaukee. Then, having once more donned the dress of Old Thunderbolt, he started out to pick up the trail of his tramp, for the farmer had given him such explicit directions regarding the locality where he had left him that he felt confident of learning something at once.

The place was a fourth-class eating saloon, in a very questionable neighborhood, and Nick went in at once.

He believed that the tramp had left a change of clothes somewhere, and why not there? It was far enough from the base of operations.

IT must be remembered that Nick wore his countryman costume.

He wandered aimlessly into the eating-saloon, and seated himself at one of the tables. They were divided from each other by thin partitions, and each one had a curtain hung in front, so that a man could pull the curtain and be entirely alone, if he chose.

There was only one waiter on duty, and the time of day was about the same as when the tramp must have entered the place. It followed, therefore, that the same waiter must have been in the eating-saloon that day.

When he came to wait upon him, Nick gave his order.

Then, when the food was brought, instead of beginning to eat at once, he looked up at the waiter and grinned.

"Suthin' funny 'bout that grub?" asked the waiter.

"No," said Nick. "I was thinkin' wot a nice trick a friend o' mine play on yew t'other day."

"When??"

"Lemme see, a week ago last Thursday, I guess it was."

"I don't study ancient history, ole man. Gimme suthin' easier."

"Don't yew remember the feller wot came in here an' sot at one o' these tables? How he hadn't been shaved nor nothin' w'en he came in, an' how he was shaved w'en he went out, hey?"

"Wot'r yer givin' us, ole chap?"

"He said he stuck yew fur the grub."

"Oh, come off!"

"An' he said that he gave up a nice new pair o' rubber-boots fur it, hey? see? Do the boots fit yew?"

"No; they're too big. But say, who're you?"

"I'm his friend."

"If you're his friend, tell me his name."

Nick put one finger on the side of his nose and winked. Then He beckoned the waiter nearer.

"This is a pretty good make-up, ain't it?" he said. "Yew didn't know me, did yew, now?"

"Blowed 'f I did. You don't mean—"

"Yes, I do."

"Well, by thunder! You're a lu-lu, you are! I thought that day when you got into the new clothes, shaved yourself, and worked the old man racket, that you was a slick one. Have you caught the feller yet?"

"Not yet. I'm onto him, though. You haven't said anything about my being here?"

"Not a word. When a feller chucks a V at me, I know enough to do as he says."

"Right."

"Say. I sent the things."

"Good! here's another V for you. How'd you send 'em?"

"By express, just as you told me."

"Right again. Did you get a receipt from the express office?"

"You bet!"

"Let me have it."

The waiter went down into his pocket, and a moment later the detective had a most valuable clew in his possession.

It was an express-receipt for a package addressed to "J.Z. Clinton, Kansas City, Mo."

No value was given, and the charges were prepaid.

It was the clew that Nick wanted more than anything else.

He talked a little longer with the waiter, paid his bill and left the saloon.

He hurried straight for the depot, took the Illinois Central road to Freeport. and from there the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul for Kansas City.

It was five o'clock the following afternoon when he stepped from the train at the Union Depot in Kansas City, and he went at once to the main office of the express company where he inquired if there was a package there for J. Z. Clinton.

At first he got no satisfaction, but when he called the manager aside and told him that he was an officer and wanted to find the man who received the package referred to, the books were examined, and it was found that J. Z. Clinton had received his package three days before.

"He called here for it," said the clerk, "and carried it away with him."

"You have no idea where he went?"

"None whatever."

"Would you know him again?"

"I think I would."

"How?"

"By his eye."

"Have you got anything particular to do to-night?"

"No."

"I'll engage your services to take a walk with me, which may last all night. I want to see if you can find Clinton for me. Can you earn ten dollars any easier?"

"Guess not."

"Meet me at the St. James at seven, then."

"I'll be there."

He was there, and the tour of the slums of Kansas City began.

Third, Fourth, and Fifth streets were traversed from end to end without result. Every dive in that neighborhood was carefully inspected, but no sign of J. Z. Clinton was discovered. About three o'clock in the morning, they found themselves on the corner of Fifth street and Broadway, and the clerk in the express-office said that he was hungry.

On the corner of Ninth and Broadway is an all-night eating-house, so they went in there for a lunch.

They had been at the table but a few moments when the clerk suddenly kicked Nick under the table.

But his excitement died away in an instant.

"What was the matter?" asked Nick.

"I thought I had found our man, but I was mistaken."

"One of those who just came in?"

"Yes."

"Which?"

"The tall one."

"Are you sure he is not the man we seek?"

"No; I'm not sure either way. They are sitting down between us and the door."

"Good! When we get up, I will be very drunk. I shall probably stumble against him and knock his hat off. You apologize for me, if I do, just as though I was a friend whom you are taking care of. Catch on?"

"Yes."

Nick's disguise was that of a young man-about-town, a favorite one with him, at times.

Presently they left the table, and Nick staggered as though he could hardly keep his feet.

When he got near enough to the table where the suspected man was sitting, he lost his balance entirely and lurched forward, full against the man whose hat he wanted removed.

The ruse was entirely successful.

Clinton's hat was sent rolling ten feet away upon the floor, and he was nearly overturned himself.

"Damnation, there goes my hat!" he exclaimed, and Nick could hardly repress a smile.

He did not have to look twice at the scar on the left side of Clinton's head to know that he was the man he was seeking.

The exclamation that he uttered was so exactly like the imitation that the young farmer in Wisconsin had given him, that he was satisfied at once.

"What in thunder do you mean!" cried Clinton, leaping to his feet and raising his arm to strike Nick.

The clerk tried to apologize, but it was no use.

Clinton would not be placated.

The arm and fist descended, and had Nick been an ordinary individual he must have received the full force of the blow.

As it was, he threw out his guard and warded it off.

But Clinton's mad was up.

He followed up the blow with another, and Nick was obliged to parry again.

In showing himself so expert, he was forced to betray the fact that he was not as drunk as he had seemed, and as Clinton followed him up to make a third attempt, he was on the point of striking back, when interference came from an unexpected source.

A middle-aged man who had been quietly seated in one corner, sprang forward and stepped between Nick and Clinton.

"Shame!" he cried, "to strike a man when he is intoxicated."

"What is it to you?" growled Clinton.

"I'll make it my fight, if you insist," said the stranger, with flashing eyes. "Go along, young fellow," he added to Nick. "I'll 'tend to this end."

Nick thanked him in a maudlin way, and followed by the clerk, left the place.

He had recognized Chick, in the man who had interfered.

AS soon as Nick was outside of the restaurant, he paid the express clerk for his services, thanked him, and bade him good-night.

He stood still until the clerk had disappeared in the direction of Main street, and then he hurried along Main street toward the power-house of the cable company.

He found a dark nook where he quickly altered his disguise, and, fifteen minutes later, Old Thunderbolt walked into the restaurant, where Chick was still holding a warm discussion with the companion of the man with whom Nick had had the row.

Where the man himself was, Nick had no idea, but he had not been in the restaurant more than five minutes when Clinton also re-entered it.

He immediately called his friend aside, and they were for several moments engaged in an earnest discussion.

Chick, of course, knew that the countryman was Nick, but he made no sign of recognition, other than a quick, warning glance, which cautioned the detective to keep very shady.

Nick, however, walked straight up to his young assistant, and at once began a conversation.

"Say, mister," he said, "can yew tell me where I can find a perliceman?"

"Why? What is the matter?"

"I've had my pocket-book stolen."

"Where did you lose it?"

"Down here in Fifth street."

"Small chance of getting it back, if you lost it there, I guess."

"Well, I've got the price of a drink, anyway? What'll you have?"

They were about to give the order when the two men suddenly approached them.

The one who had tried so hard to strike Nick in his former disguise walked straight up to Chick, and placed his hand upon his shoulder.

There was something menacing about the man's attitude, and his eyes glittered like those of a snake as he began to question the man who had interfered with him when he had attacked the drunken man who had knocked his hat off.

"Will you tell me your name?" he said.

"Why?" asked Chick. "Are you looking for more fight?"

"No; I'm looking for information."

"Well, what do you want to find out?"

"I want to know who that young fellow was whose part you took in here?"

"Well, then, I guess you'll have to ask him."

"Was he a stranger to you?"

"Entirely."

"Didn't you ever see him before?"

"Not that I know of. Can't you forgive a young fellow who's got a load on, for knocking your hat off?"

"That's all right, my friend, but he wasn't half as drunk as he seemed."

"Why not?"

"Because he got away too quick."

"Oh, you followed him out, did you?"

"Yes, I tried to; but he disappeared altogether too quick to suit my fancy."

"Well, I don't know anything about him."

"I say, stranger," said Nick, interrupting the conversation at this point, "Me 'n this here feller were just goin' to have a drink. Wont yew j'in us?"

"No, we buy and pay for our own drinks."

"Git out! Do yew now? Yew don't look it."

"What do you mean, old moss-back? I'll give you a lift under the ear."

"Git out! Will yew? Yew'd better not. It might give me a fit. I have fits sometimes, and when I have 'em, I always clean out the room I'm in, proprietor and customers included. What are yew goin' to have to drink?"

"I suppose you think you're a fighter," said Clinton, savagely. "If you don't shut up, I'll just tie you up in a knot, old man."

"Git out! Will you, now? S'pose I should have fits?"

"I'll give you a fit."

"Git out! Will you?"

"Yes, curse you! Take that!"

As Clinton uttered the last word, he let drive a furious right-hand blow full at Nick's face.

But his fist struck nothing but the empty air, and the next instant he found himself rolling over and over upon the floor, where he had been sent by Nick, who seized him by the arm and threw him with all his strength.

Clinton leaped to his feet, furious with anger.

In a second he whipped a big six-shooter from his pocket, and raised it to fire.

It was, then, that the Little Giant performed one of those marvelous snap-shots for which he had no equal in the world.

His arm flew up, there was a flash and a report, and the would-be murderer uttered a loud cry, and fell flat upon the floor.

Instantly there was consternation in the restaurant.

Waiters ran forward, the bartender leaped the bar at a bound, and two or three scattering customers who were seated at the tables sprang to their feet in dismay.

Everybody thought that the man had been killed.

But they were quickly undeceived.

Clinton did not remain a moment upon the floor, for the ball had only grazed him.

He recovered his feet, and then with a loud and furious oath, started toward Nick.

Ere he had taken two steps, however, he came to a sudden halt, for he found that he was covered by a six-shooter as big as his own.

It was in the hands of the strange countryman who was subject to fits, and who, to all appearance, had just had one of the most violent kind.

"Stand right where yew are," said Nick, coolly, "'cause this ere thing might go off, if yew came any closer. I jest want to do a little talkin' to yew."

"Curse you!" growled Clinton.

"Curse away," said Nick, "that don't hurt any."

"Well, what do you want to say?"

"I jest wanter ask yew what yew're goin' to have to drink. Yew see, when I ask a man to drink, and he don't refuse perlitely, why then he's either got to drink or get hurt. What yew goin' to have?"

"Whisky."

"That's right. Now, you put your gun up, and I'll put mine up. I didn't hurt yew much, did I?"

As a matter of fact, Nick had wounded Clinton on the right side of his head, just above the ear, and exactly opposite the scar that he already bore, by which Nick had been able to identify him.

His companion was one of the cooler kind, and he had not taken part in the row, because he doubtless appreciated the risk that was run in so doing.

Clinton had also evidently come to his senses, for he took his drink with as good grace as he could command, and then, accompanied by his friend, left the restaurant.

Nick and Chick were thus alone together, for the first time since they had parted in Milwaukee.

"Who was the other fellow?" asked Nick.

"One of the hunters."

"I thought so. Do you know where to find him when you want him?"

"No, and I'm afraid they will give us the slip now."

"No fear of that."

"Why?"

"One or both of them will watch outside to see if we try to follow, and in the meantime I can get out of this rig and take up the trail as soon as I have asked you a few questions."

"All right."

"How did you get here?"

"Over the Alton road from Chicago."

"Have your hunters communicated with anybody else on the trip?"

"They did not until they reached here."

"What happened then?"

"This is the fourth man that they have interviewed."

"Making a party of six in all, eh?"

"That is the way I count it."

"Did your men come here together?"

"Yes."

"When did they get here?"

"Night before last."

"They are evidently about ready to divide the spoils of the train robbery."

"That is my idea."

"What puzzles me is, why they didn't get together sooner."

"Probably they put the meeting off until this time for the sake of safety."

"Well, Chick, we have got pretty good reason to believe that we are after the right parties. You followed out one clew, and I another, and they have brought us together in a restaurant on the corner of Ninth street and Broadway, in Kansas City, six hundred miles from the scene of the train robbery.

"No matter how many men were engaged in the affair, they will probably get together here within the next twenty-four hours for a division of profits, and we must be there to claim our share."

"Yes, and the lion's share."

"After I have been gone from the restaurant a few minutes," said Nick, rising from his chair, "you had better work a change, and follow me."

"All right, I'll be ready."

Nick walked the length of the room, and disappeared behind a screen.

Five minutes later he reappeared, but nobody in the restaurant except Chick had any idea that he was the countryman, who, only a few moments before, had been so quick with his revolver.

Now, he was again dressed as a gentleman, and he walked boldly out upon the street, glancing neither to the right nor the left.

Two men stood together upon the opposite corner.

Nick recognized them instantly, but apparently not noticing them, he turned and walked toward the Coates House, discovering, however, long before he reached Tenth street, that he was being followed.

"They are shrewd ones," he reflected, "and although they do not half-suspect that I am either the countryman or the 'other fellow,' one of them is going to find out for certain, while the other waits upon the corner for him to return, still watching for Old Thunderbolt.

"But I will show them a trick worth two of that, and I will track them to their headquarters between now and daylight, as sure as my name is Nick Carter."

NICK walked boldly into the Coates House, paused a moment in the billiard-room, and then took the elevator, just as though he belonged there.

But ten minutes later he was again upon the street, and this time his disguise was a perfect representation of a negro.

It was in that character that he intended to follow the two men wherever they went.

The man who had followed him from Ninth street had evidently just made up his mind that there was nothing to fear from that quarter, for he was half-way down the block to rejoin his companion, when Nick saw him.

Both seemed satisfied that their fears were without foundation, for as soon as they came together again, they started away, walking rapidly.

Nick kept up the pursuit.

He knew that Chick would manage to shadow him while he shadowed the train robbers, and he was not mistaken.

The two men took the Fifteenth-street cable-car and rode to the terminus.

Then they started away on foot, with Nick still following.

They walked a long distance, finally turning to the left along the Blue River Valley.

It was difficult work to shadow them there, even in the darkness.

Nick was obliged to keep entirely out of sight, for there were no persons on that lonely road, and if the men should see him, and suspect that they were being followed, they would not hesitate to ambush and shoot him down, as they would a dog which annoyed them.

But the detective knew the region thoroughly, and when finally he saw the men leave the highway and turn into the Blue River Valley, he knew almost to a certainty where they were going.

He was so positive that he did what he never had done before.

He stopped, and allowed the men to go on their way unwatched; allowed them to pass out of his sight in the intense darkness of the valley.

He wanted to wait for Chick, for there must be no mistake in the work that was about to be done.

There were six men to cope with, every one as desperate and determined as men could be.

Not one of them would hesitate to send a bullet through the brain of anybody who might have the temerity to interfere with them in their plans, and every one would rather be killed than be captured.

Nick knew that as well as he knew his own name.

He knew the character of Western desperadoes; he knew with whom he had to deal.

Men who will hold up a train that is loaded with passengers; who will face hundreds without flinching, threatening death to anybody who offers to interfere with them, are no mean foes. To tackle them, and to attempt their arrest in a lonely place like the valley of the Blue River, is a job which few men would attempt, and which would require all the courage, fortitude, and skill of Nick Carter himself.

In the Blue River Valley, about three-quarters of a mile from Fifteenth street, was an old house which had stood there many years.

It was deserted, and had earned the reputation of being haunted.

Nick believed, and with good reason, that the train robbers meant to rendezvous there.

He had not long to wait ere Chick joined him.

Then, in a few words, he told his faithful assistant just what he wanted done, and they crept forward.

When they turned into the path along the valley, it was necessary to proceed with great caution, because the men might suspect that they were followed, and watch the approach to their place of meeting.

But if they had done this, they had abandoned the watch before Nick and Chick came along.

They found the coast clear, and, meeting with nothing to hinder their progress, they were soon at the old house, where they knew that the men who had held up the train on the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad at Western Union Junction were at that moment in consultation for a division of the proceeds of their venture.

The two detectives examined their weapons carefully, and then crept forward.

It wanted only about an hour of daylight; the best time in the whole twenty-four hours for a secret meeting to take place.

Nick crept up on the low step before the door.

He lifted the latch with great care, and pushed.

The door was not locked.

Chick was right behind him, and they both passed through and closed the door after them.

They could hear voices from the back-room of the house.

Nick opened the mask of his lantern just enough to get a glimmer of light for one brief instant.

It was enough, however, to give him an idea of his surroundings.

There was a door wide open, which led into a little room at one side of them, and he pulled Chick in there.

Suddenly, and almost as soon as they were out of sight, the door of the room where the men were assembled was thrown open.

"Did you lock the front-door, Bob?" they heard a gruff voice demand.

"There's no lock on the cussed thing," was the reply.

"Well, then we'll leave this door open. I ain't going to be surprised at this thing."

"No fear out here in the Blue Valley, Dick."

"That's all right. Git to biz now. It'll be light afore you know it."

"Get out the swag, Tim."

"There it is."

The listening detectives heard the sound of something falling upon a table.

It was doubtless made by the packages in which the money was done up when taken from the express-car.

"Is it all there, Tim?"

"Every bit."

"You haven't got away with a thousand or two, you and Sam, eh?"

"Not a cent."

"Well, I'll believe you, because I know just how much there was."

"How do you know?"

"Didn't you see it marked on the outside of the packages?"

"Yes, but you were too busy with your guns to notice a thing like that."

"Was I?"

"I'd have been."

"When I marched the engineer and fireman down the track, I looked at the packages before I chucked them aside for you."

"Well, how much swag is there, since you know so much?"

"Twelve thousand."

"No, only ten."

"Twelve, I say; if there is only ten now, you have got the other two. I was in this biz too long with Jesse, not to know how to take care of myself when I had to trust somebody else."

"Jesse's dead!"

"You'll be, too, unless you fork over the twelve. Three thousand apiece for Dick and me, and the other six for you four. That was the agreement."

"What was?"

"One-fourth of the whole amount for each of us, and the balance for the rest of you; divvy up."

"Well, there ain't but ten."

"Say, do you see this?"

"Yes."

"It's a six-shooter; it's loaded; it's aimed at your heart. Hand out six thousand or die."

"I tell you there's only ten."

"Will you fork over the six?"

"No."

There was a loud report, a scream of agony, and then report after report echoed through the house.

There were cries and groans; oaths and shouts; curses and yells.

At least twenty revolver shots were fired, and then all was still.

Nick was about to creep forward.

Suddenly he paused.

He heard a voice.

"I'm alive, and so are you, Dick," it said. "Are you hit?"

"Yes."

"Bad?"

"No. In the arm."

"And I in the leg. We'll have it all now."

"You bet!"

"Not quite all," cried Nick, as with a bound he leaped into the room, followed by Chick.

They covered the two men with their revolvers, and they, seeing that there was no help for it, threw up their hands and surrendered.

There were four dead bodies on the floor, for the thieves, in fighting among themselves, had made the job just so much easier for Nick Carter and his assistant.

Bob and Dick were securely handcuffed, and then the spoil was examined.

Only ten thousand dollars was recovered, and if there had originally been twelve, Tim had securely hidden the remaining two.

But victory remained with Nick Carter.