RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

NICK CARTER and Inspector Byrnes were closeted together in the Little Giant's study.

The time was ten o'clock in the evening.

Both were smoking, and both were silent.

The hiatus remained unbroken for several moments, and was then interrupted by the celebrated inspector.

"Well, Nick," he said, "I suppose you know that my errand here to-night was caused by something more than the mere desire to smoke a cigar with you."

"Well, yes," replied Nick; "but I thought I would wait for you to open the ball."

"All right, Nick. I am ready."

"Fire away, then."

"I want to put you in harness again."

"Am I ever out of it, inspector?"

"My application of the term refers only to the regular horse."

"I don't think I quite catch on, inspector."

"I would like to attach you to my office, on regular duty."

"Impossible."

"Ah, well, I supposed so!"

"I am always ready to take a special case for you, inspector."

"Thanks."

"You have one on your mind now?"

"Yes."

"What is it?"

"It is rather a puzzler for my men, Nick."

"Tell me the story."

"Have you ever heard of Violet Graham?"

"The actress?"

"Yes."

"Often."

"She has disappeared."

"Indeed!"

"Yes. She was last seen two weeks ago to-night, when she was leaving the theater. Since the moment that she passed from the stage-door into the street, absolutely no trace of her can be discovered."

"Your men have searched for her?"

"Diligently."

"And without success?"

"Entirely."

"She was very beautiful, was she not?"

"Extraordinarily so."

"Has any cause been assigned for her disappearance?"

"None."

"With whom was she living at the time?"

"Her mother."

"Ah, yes, I believe I have heard that her mother is an invalid!"

"She is."

"Does she venture an opinion regarding the cause of her daughter's disappearance?"

"She is incapable of one."

"Why?"

"The sorrow caused by her daughter's disappearance has unbalanced her mind."

"Ah!"

"She has become a harmless lunatic."

"Does she rave at all?"

"At times."

"What is the chief characteristic of her paroxysms?"

"It is only during those moments when she seems to realize her loss that she raves about her daughter, and appears to believe that Violet has been murdered."

"What is your opinion, inspector?"

"I am entirely without one."

"What! you have no opinion regarding this case?"

"None, except that the girl is lost, and must be found."

"You have, of course, examined into every detail connected with her life?"

"I have, thoroughly."

"And have found nothing upon which you can base an opinion?"

"Nothing."

"How old was Violet Graham?"

"She disappeared on her twentieth birthday."

"Had she a lover?"

"A hundred."

"I mean a favored one."

"No."

"You are, of course, positive upon this point."

"Of course."

"Was there one who was particularly persistent?"

"A dozen."

"Out of that dozen was there one who might be called dangerous?"

"I think not."

"You think not?"

"There is not one among them of whom I can find any trace that I would class as dangerous."

"Still, danger often lurks where we least expect it. You have examined into the habits of all of them?"

"Certainly."

"And have found no clew?"

"None."

"Is there any point connected with the girl's life which would serve as a starter?"

"If there is, my men have not discovered it."

"Then where am I to begin?"

"At the theater."

"But if you, with all your sagacity, have failed to follow her beyond the stage-door, how do you suppose I am to be more successful?"

"My dear Nick, you are possessed of three traits which render you invincible as a detective."

"Indeed! what are they?"

"Wonderful sagacity."

"That's one. What is the second?"

"Extraordinary nerve."

"But your men possess these same qualities, and therefore it must be the third upon which you place your dependence on me in this case."

"It is."

"I am anxious to hear it."

"It is supernatural luck."

"Well, I am lucky, that's a fact."

"Go in on your luck this time, Nick, and see what you can do. There is no reward and no remuneration for you. in this case, more than the regular pay which you will receive from the department while so employed."

"But you have a personal interest in solving this mystery?"

"I have."

"May I, without being impertinent, ask what is it?"

"You may, for here it is."

The inspector passed a slip of paper across the table to Nick.

He received it, and spread it open before him.

It was an ordinary half-sheet of note-paper, upon which had been sketched the picture of a coffin.

Across the lid was printed the name "Violet Graham," and underneath it was written in a copper-plate hand these words:

Inspector Byrnes isn't in it; but he will be, unless he abandons the search for Violet Graham.

The Thirteen.

"When did you receive this, inspector?" asked Nick, after a moment's pause.

"The day before yesterday."

"How?"

"Through the mail."

"Where was the letter posted?"

"At Station E."

"Was the envelope addressed in the same hand?"

"It was."

"You caught on to the signature?"

"Yes."

"There may be some connection between this and the gang I once broke up."

"There may be—yes."

"Well, this is a starter, anyhow."

"Not a very satisfactory one."

"No, and yet—"

"What?"

"If it has aught to do with the original 'Thirteen,' it will prove a good beginning."

"Yes. Tell me what you make of it, Nick."

"It simply proves that the disappearance of Violet Graham was the consequence of a plot to abduct her."

"In other words, it is evidence that she did not wander off in a fit of dementia."

"Exactly."

"Well?"

"If she was abducted, there was a motive."

"Assuredly."

"And that is the first thing for which we must search."

"By all means."

"Let us glance over a few."

"Gladly."

"First, then, we will take the probable motive of one of her would-be lovers."

"Yes."

"There is the theory that non-success in his projected suit maddened him to the point of perpetrating the crime of abduction in order to secure her."

"Yes."

"Or, failing in the requisite courage to execute such a deed, he has lured another to do it for him."

"Go on."

"In that case the hired accomplice is a woman."

"Why?"

"Because Violet would not have gone willingly with a man."

"Exactly."

"There would have been an outcry, a scuffle, or a disturbance of some kind that would have attracted attention and been remembered."

"Very good."

"If she was abducted by a woman, we can get some trace of her.

"We both know the character of woman that this man would seek to employ; knowing them, and where to find them, we can find the right one."

"Correct."

"Now for motive No. 2."

"Proceed."

"The girl was beautiful, and in every way attractive."

"She certainly was."

"It is possible, perhaps probable, that she may have become the victim of one of those same women to whom I just referred; and that, without the instigation of an unsuccessful gallant."

"Yes."

"In that case also we can find her."

"Ay, but she might better be dead."

"Motive No. 3."

"What is that?"

"I have seen Violet Graham upon the stage. She wore a magnificent diamond necklace, which was the wonder and the admiration of her compatriots and her audience."

"She did, and that necklace has a history."

"Yes, and that history comes in motive No. 4, but I have not yet finished with No. 3."

"Continue."

"The avaricious eye of some crook may have rested upon that necklace, and fired him with the determination to possess it."

"To that end he may have determined to abduct and murder its owner."

"In that case, also, he has employed the aid of his 'Mol,' and thus we have a clew upon which to begin operations."

"But if motive No. 3 be correct," said the inspector. "Violet's body would have been in the river long ere this."

"In all probability."

"The river has given up no dead which could by any possibility be identified as Violet Graham, and the morgue tells us nothing."

"That brings me to motive No. 4. To my mind it is the most probable of all."

"I think I see your point."

"Wait. Let me explain."

"YOU referred, a moment ago, to the history of the necklace, worn by Violet," continued Nick, presently.

"Yes."

"Have you heard that history?"

"In part."

"The necklace is said to be an heir-loom, and to have come to Violet from a branch of her family residing in England."

"Yes, I have heard that."

"The family name I have not learned; have you?"

"No."

"Graham is doubtless a stage name."

"Probably."

"Her people abroad are said to be very wealthy."

"Yes, I have heard that also."

"The story is the old one about the mother belonging to a noble family, marrying beneath her, and being cast off."

"Yes."

"May it not be that her relatives, somewhere, may have an object in getting rid of Violet? If there is a fortune that would, in the course of events, go to her if living, but which might be preserved intact, and to the good of those same relatives if she were dead, it would certainly be to their interest to put her out of the way."

"Right, Nick."

"I will set Chick to looking up the history, while I follow the trail from this end."

"A good idea."

"There are a few questions that I would like to ask, inspector."

"What are they?"

"How did Violet usually go to and from the theater?"

"She walked."

"The distance was not great, then?"

"No—not more than a quarter of a mile."

"Are there carriages at that stage door, as a rule, when the theater is out?"

"Yes, always: from one to three or four."

'How many were there on the night of the disappearance?"

"Some say two and some three. In reality there were three."

"You have found them all?"

"Of course."

"And still no clew."

"None."

"Might there not have been four?"

"Certainly."

"Could you get any trace of a fourth?"

"No."

"She must have been taken away in a carriage."

"Yes—if she left the theater by that door."

"Ah, you think she—"

"I think she might have changed her mind, and instead of passing out at the stage door, might have gone through the auditorium."

"That is possible."

"Also, she might have forgotten something, and have returned to get it, and so have been attacked in her dressing-room. At all events, Nick, there has been foul play of some kind going on, and because I have taken the matter in hand, those concerned in the scheme dare to threaten me."

"Exactly."

"I will not stand that sort of thing."

"No; you are hardly the proper party to threaten."

"I will have that girl found, Nick, and I will get into my clutches the man who sent this picture and warning to me, if it takes ten years to do it—ay, even if I have to go on the trail myself."

"You cannot spare the time, inspector."

"No."

"I will do it for you."

"I thought you would. Now, I have another thing to speak of."

"What is that?"

"There was a robbery committed the same night by the same parties."

"Eh?"

"It's a fact, Nick."

"By the same parties?"

"Yes."

"How do you know?"

"By this."

The inspector passed another half-sheet of paper to the Little Giant.

It bore a drawing of a coffin, evidently made by the same hand that had designed the other.

On the plate was written the name "Nick Carter," and underneath, in the same fine penmanship, was this message:

To Inspector Byrnes:—

Nick Carter isn't in it—yet—but he will be if you dare to call him in on this case. Take heed.

The Thirteen.

"Humph!" muttered Nick.

"What do you think of that?" asked the inspector. "I think they meant to get me into the case."

"So do I. That is one inducement for my coming here."

"It is the old plot against me, revived."

"Without doubt."

"Now, tell me of the robbery."

"James Winslow's safe was opened and eleven thousand dollars in cash was stolen."

"Quite a haul."

"Yes."

"Who is James Winslow?"

"A retired merchant living on Forty-seventh street."

"What do you know about him?"

"Simply that he lives there, that he is a man about sixty and has not been in active business for a number of years. He came here from the West."

"When did this robbery occur?"

"The night before last."

"In the night?"

"Yes."

"Did Winslow send to you?"

"He called upon me."

"What—"

"Wait, Nick. I have told him to go and see Old Thunderbolt."

"Ah!"

"He is to call upon the countryman detective, in the morning."

"At what time?"

"At ten."

"Old Thunderbolt will be in his office."

"Good! You had better get your particulars direct from Winslow instead of questioning me."

"Yes."

"You can talk it over with me afterward."

"All right."

Fifteen minutes later, the great inspector departed.

A half-hour after that, Chick entered the house.

Nick speedily told him the story of Violet Graham's disappearance, and instructed him to set about the discovery of her family history in the morning.

"Nick," said the young man, when he had heard all that the Little Giant had to tell him, "I think the whole thing is a scheme."

"So do I."

"I think we differ regarding the nature of it."

"What is your idea?"

"I believe it is nothing more or less than a plot against you."

"Against me!"

"Yes."

"They would hardly abduct a girl from one part of the city, and rob a safe in another part, for the mere purpose of getting me on their track."

"I think they would."

"Why? There are easier and less dangerous ways in which the same effect might have been produced."

"I don't agree with you."

"Tell me why."

"You see it as clearly as I."

"No doubt; and yet your version may give me some new ideas."

"First, then, the girl was stolen, and the inspector warned."

"Precisely."

"They covered up their tracks in such a manner that they knew he would have to take the trail himself, or call you in."

"Well?"

"Second, to make sure that he would call you into the case, they worked the safe racket, got away with some boodle, and then sent him another warning which referred to you."

"Yes."

"That was the clincher. The inspector came, and you have the case."

"Well, what does that prove?"

"Considerable."

"What? They could have shot me, stabbed me, or poisoned me without going to all that trouble."

"I think not."

"Why?"

"Well, chiefly because they have tried it several times and failed."

"Go on."

"In this matter, unless I am greatly mistaken, you will find that they have laid their plans way ahead, and that they mean to get you into their clutches alive."

"It may be."

"And—here comes my most prominent point—if I am right. I think you will get an unexpected clew at once."

"You may be correct, Chick."

"If you do get such a clew, be careful, Nick."

"I'll look out."

"Who is Winslow?"

"I don't know."

"He's to call upon you in the A.M."

"Yes—that is, on Old Thunderbolt."

"Have you any idea that anybody aside from Inspector Byrnes and myself has any idea that Old Thunderbolt and Nick Carter are one and the same?"

"No."

"Nor I—and yet—"

"Well?"

"This gang may have 'got onto' it."

"Doubtful."

"If, as Old Thunderbolt, you are given the clew, you will suspect that they have, won't you?"

"Probably."

"When shall I report?"

"When you have something to report."

"That will be soon."

Their conversation was interrupted at that point by the ringing of the door-bell.

Patsy had gone to bed—the readers of the preceding number will remember that a youth named Patsy had taken Peter's place as Nick's servant, and so Chick went to the door.

A moment later he returned, bringing an American District Messenger boy with him.

The boy carried a package.

"Something for you, Nick," said Chick.

Nick took the package and laid it on the table before him.

"Where did you get this, boy?" he asked.

"At the office."

"Did you see the man who left it?"

"A woman left it."

"Indeed! You saw her?"

"Yessir."

"Describe her."

"Can't."

"Why?"

"She wore a veil."

"Did you hear her speak?"

"No, Sir."

"Was she tall or short, lean or fat? Tell me what you saw."

"Saw a woman, she was kinder tall an' kinder fat, that's all I know."

"You may go, young man."

When he was gone, Nick lifted the package from the table.

It was very light.

He cut the string, and unwound it.

Presently a little pasteboard box was disclosed.

Removing the cover, he was surprised to find that the box contained a jeweled stiletto of Italian pattern.

It was lying upon a bed of cotton, and beside it was an envelope.

An examination of the envelope disclosed the following:

Nick Carter:—

We send a little present. If you do not accept this as it is intended, you will receive another, ere long; but next time it will pierce your heart. We know that Inspector Byrnes has been to see you. Drop the cases he gave you to-night, or beware of The Thirteen.

"Well," said Nick; "this is what might be called egging me on."

Chick picked up the stiletto.

"Careful, Chick," said the detective. "Without doubt that point is poisoned. You were right, my boy. This thing is a plot against Nick Carter, and, by heavens, I'll accept the challenge."

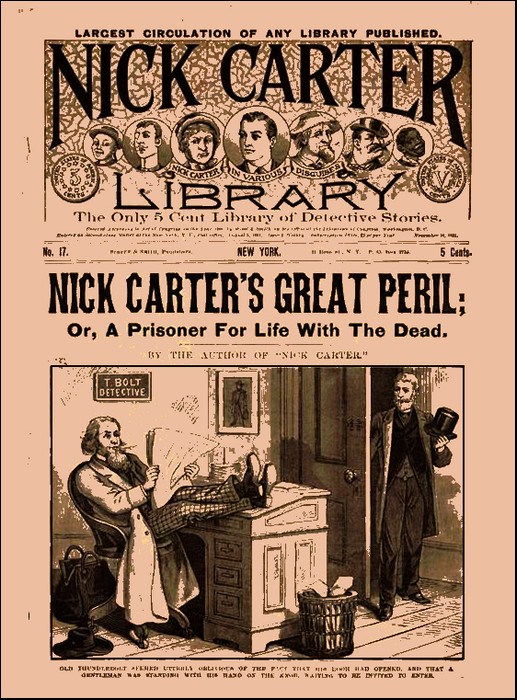

THE office of Old Thunderbolt was situated in Liberty street near Pearl, and at ten o'clock on the morning following the incidents narrated, the old man was sitting before his desk intently scanning the morning papers. Over his head was a gilt sign, which bore this legend:

T. BOLT, DETECTIVE,

and on the outside of the door, which opened at the head of a narrow flight of stairs, which led to the street, was the sign:

THOMAS BOLT, Detective.

WALK RIGHT IN.

In appearance, he was the very last person that a client, with an important case on hand, would be likely to select as a shrewd detective.

A mass of shaggy and unkempt gray hairs covered his head, and a long chin-beard of the same hue half-concealed the high collar and stuck which he wore.

His coat was so long that it swept the floor around the chair in which he was sitting, and he wore a checkered variety of what the boys call "high-water-pants."

On the floor at his right side was a broad-brimmed, black slouch hat, and on the other side was a carpet-bag of the "down-east" pattern.

His feet were stuck over one corner of the desk, and he seemed utterly oblivious of the fact that his door had opened, and that a gentleman was standing with his hand on the knob, waiting to be invited to enter.

Presently he coughed insinuatingly.

"Got er cold, hain't yew?" asked Old Thunderbolt, without removing his eyes from his paper. "Guess yew wanter give me one tew by the way yew're holdin' that door open. Come in, can't yew?"

"Thank you."

"Git out! What fur?"

"Are you Old Thunderbolt?"

"Sometimes, when I hev fits; ordinarily, I'm only plain T. Bolt."

"You are a detective?"

"Wal, some think so, an' ag'in some don't."

"Inspector Byrnes sent me to you."

"Git out! did he?"

"Yes."

"What's yew're name?"

"James Winslow."

"'Tis, hey. Wal, wat kin I dew fur yew, Jim?"

"Sir!"

"Didn't yew say yewer name was Jim?"

"My name is James Winslow, and I am usually called Mister Winslow."

"Git out! air yew. I've heard tell that all good rules have exceptions. Did yew come to see me on biz, 'r only fur instance?"

"On business."

"All right; set!"

"Eh?"

"Set down, can't yew?"

"Certainly."

"All right. I didn't know but yew had a bile as well as a cold, Jim. Now talk."

"My safe has been robbed."

The entire manner of Old Thunderbolt seemed to change at once.

His face assumed a keen expression that could not be mistaken, and his eyes glanced sharply from under his shaggy brows.

"Eleven thousand dollars were taken," continued the caller, "and I want you to find the thief."

"Whar is yewer safe?"

"In my house."

"What part o' the house?"

"In my back parlor."

"Combination or key?"

"Combination."

"How many figgers?"

"Three."

"Blowed open, 'r worked?"

"The combination was used to open the safe."

"Who knew it?"

"Knew what?"

"The combination?"

"I did."

"Who else?"

"Nobody."

"That's a whopper!"

"Sir!"

"'Tain't so, on the face of it."

"What do you mean? Do you think that I would lie about it?"

"Wal, yew hev, hain't you?"

"Good-morning, sir."

"Yew said that when yew came in."

"But you are insulting."

"Git out! am I?"

"Yes."

"Didn't yew say that nobody knowed the combine but yewerself?"

"Yes."

"Didn't yew say that the robber worked the combine?"

"Yes."

"Be yew the robber?"

"Certainly not."

"Wal, then; didn't yew tell a lie when yew said—"

"Ah, I see!"

"Git out! dew yew?"

"Yes."

"Then somebody besides yew knowed the combine."

"Evidently."

"Who?"

"I don't know."

"Didn't yew ever tell it to nobody?"

"Never."

"Dead sartin?"

"Yes."

"What was it?"

"The combination?"

"Yes."

"Wait, before I tell you, I will show you how I remembered it myself."

"Yew've got a bad memory fur figgers, hey?"

"Yes."

"Well, spit 'er out."

"I keep the numbers in this little book."

"Writ out?"

"See if you can find them."

Nick looked at the book carefully.

It was an ordinary address-book, and on the fly-leaf was written the name of its owner, James Winslow.

Underneath the name were the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 0.

The figuers 3, 5, and 7, were crossed out with red ink.

Nick turned to page three of the book, then to page five, and then to page seven.

Then he returned the book.

"Any fule cud read that air combine, ef he knew 'twas in the book," he said.

"Do you mean to say that you have discovered it?"

"I hev."

"What is it?"

87, 51, and 49."

"You astound me, sir."

"Git out! Do I?"

"Yes."

"Be the figgers right?"

"Yes."

I thought so."

"Tell me how you discovered them."

"Wal, yew've scratched out 3, 5, and 7, hain't yew, on the front leaf?"

"I have."

"Yew got a new address-book on purpose to keep yewer combine in, didn't yew?"

"Yes."

"There ain't nothin' in 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 0, is there?"

"No."

"'Cept that 8, 5, 7, air scratched."

"That is all."

"Then the furst question wat I ax myself is, Wat's that done fur?"

"Well?"

"I calkerlate it refers to page three."

"Yes."

"I turn there an' find at the top o' the page, Brown, John, 87 Woodsum street."

"Well?"

"Yew didn't even put down the city wat Brown, John, lives in, did yew? Say, where does he live?"

"In er—er—Philadelphia."

"Does, hey? Say Jim, there hain't no Woodsum street in Philadelfy."

"Ah!"

"Then I goes to page five, and at the top o' the page I find 'Cook, John, 51 State street.

"Go on, please."

"You brown yer things fust, an' cook 'em arterward. Most fellers do this cooin' fust. Yer forgot the town ag'in, didn't yew?"

"Yes."

"On page seven I find, ag'in at ther top o' the page, 'Dunn, John 49 Spring street.'"

"Ah!"

"Ag'in yew forgit tew name the town."

"Yes."

"Now I hev Brown, John, Cook, John, an' Dunn, John, an' arter 'em I hev 87, 51, an' 49, see?"

"Yes."

"That's the combine o' yewer safe, ain't it?"

"Yes."

"Where do yew keep this book?"

"In my pocket."

"Allers?"

"Yes."

"Hain't been out lately?"

"No."

"Sartin?"

"Sure."

"How'd yew happen to hev so much money in the safe that night?"

"I had a mortgage paid off."

"When?"

"That afternoon."

"Where?"

"In my own house."

"Who paid it?"

"A real estate agent named Decker."

"I know him. Who else was present?"

"Nobody."

"Who knowed yew received the money?"

"Nobody."

"When did yew put it in the safe?"

"Right away."

"Afore Decker left?"

"No, afterward."

"What time was it when he paid yew?"

"Half-past one."

"Where do yew keep yewer bank account?"

"At the Metropolitan Exchange Bank."

"That's near yew."

"Yes."

"Why didn't yew take the money tew the bank?"

"I was suddenly called away on business."

"What kind o' biz?"

"A friend was very sick and sent for me."

"Who's yewer friend?"

"Henry Easton."

"Where does he live?"

"What has that got to do—"

"Dew yew want me tew take yewer case?'

"Yes—certainly."

"Certainly—certainly."

"Where does Easton live?"

"In Eighty-first street."

"East 'r west?"

"East."

"Wat number?"

"Twenty-four."

"Who came arter ye?"

"His son."

"Did he see the money?"

"No."

"Know ye had it?"

"No."

"Did yew put it in the safe while he was there?"

"Yes."

"Where was he?"

"In the front parlor."

"An yew was in the back?"

"Yes."

"Then yew went out?"

"Yes."

"With young Easton?"

"Yes."

"Wat's his name?"

"The same as his father's—Henry."

"In wat shape was the money?"

"One-hundred-dollar bills."

"All of it?"

"Yes."

"Why didn't Decker pay you in a check?"

"I didn't ask him."

"YEW kin go now, Jim," said Old Thunderbolt; when Mr. Winslow made the reply recorded at the end of the preceding Chapter.

"Whom do you suspect, Mr Bolt?"

"Wal, I hain't made up my mind yet."

"I hope you have no suspicion against my friend Easton, or his son?"

"I hain't."

"I was about to say—"

"Say it."

"That I remained with my sick friend all night, and Harry was in the room with me."

"Yew wa'n't at hum when the safe was robbed?"

"No."

"How's yewer friend? Gittin' better?"

"Decidedly."

"Thats' good. Who lives in the house with yew?"

"Two servants."

"Wat air they?"

"A man and a woman. Husband and wife."

"I'll kim up an' see 'em."

"I cannot suspect either of them."

"That's right, don't; say?"

"Well?"

"How old air yew, Jim?"

"Fifty-one. Why?"

"Yew look older."

Winslow smiled.

"Most men would resent that," he said; "but I take it as a compliment."

"Git out! Dew yew?"

"Yes."

"Wal, I hain't got any more questions to ax now."

"I have one request to make, Mr. Bolt."

"Wat is it?"

"I don't want you to bother the Eastons about this."

"Hadn't thought of it."

"Thanks."

"Don't mention it."

James Winslow withdrew, and Nick picked up the paper again and read a full column.

Then he laid the paper down and began to think.

We are permitted to read his thoughts, and here they are.

"Point one," he reflected; "James Winslow is a fraud of the first water. He wears a disguise to make him look older than he is; a clever one, to be sure, but a disguise.

I caught him when I asked him his age, and before he thought, he told me the truth. He is just about fifty-one, and he looks sixty-five.

"Point two: He does not know a man named Easton who lives at 24 East Eighty-first street, for the reason that no such man lives there.

"I happen to have a friend who lives at that number, and therefore I know that. Winslow lied. He used the number and the name of the street at random.

"Point three: If Decker paid the money at all, he paid it in cash because he was requested to do so. I know that he would prefer to pay it in a check, and I would be willing to bet that he first insisted upon doing so.

"Point four: If Winslow was robbed, he robbed himself, and when he went to Byrnes he figured that the inspector would send him to me.

"Point five: He knows that Old Thunderbolt and Nick Carter are the same.

"Point six: Chick was right, and the whole thing is a conspiracy to down me.

"It is a revival of the 'Thirteen,' and they have not been slow to let me know that fact, for the very reason that they are well enough acquainted with me to know that I will not hesitate to go for them, to put myself in their way

Twenty minutes later, Nick left the office, and started up Liberty street toward Broadway.

When he reached the junction of Maiden Lane and Liberty street he saw a bit of paper, neatly folded, lying on the sidewalk in front of him.

He stooped and picked it up carelessly, and presently opened it.

Then he stopped suddenly and glanced around him, first one way and then another.

Soon his eyes again sought the paper.

Here is what he read:

"To-night. Sleepers pier, East River, Twelve sharp. Tug Roarer. Finish the girl business."

That was all.

There was no address and no signature.

There was one noticeable fact, however.

The note was written in the same copper-plate-like hand that had penned the various warnings.

For a moment Nick was puzzled.

Then his face cleared.

"This is the clew," he thought. "Clews don't grow on pavements and things, as a rule, and this was either left here on purpose for me to find—that is, some fellow who was watching for me and saw me coming, dropped it for me to pick up, or, it may be that Winslow dropped it through carelessness.

"I incline to the first idea, however.

"Chick is a cute one for his years and experience. He hit the nail on the head when he said that we would find a clew somewhere soon.

"Well, one thing is certain, I have found one that they did not mean me to get, and that is that Winslow is a fraud.

"Tugboat Roarer, eh? The thing is evidently a trap, but I think I will walk into it just the same.

"I may end this thing much sooner than they intend me to.

"Tugboat Roarer, Sleepers pier, East River: midnight. Correct. I'll be there, sonny, and if you can get away with Nick Carter on the first deal, you'll have a chance."

Nick sauntered slowly up Broadway, and had reached Canal street, when he was accosted by a well-dressed young man, who asked him the way to Grand street.

"Walk right along with me an' I'll show yew, mister," he said; and they passed on.

"Found anything, Chick" he asked, presently, in a low tone.

"Yes."

"What?"

"Violet is an heiress."

"Is, eh? Who told you?"

"I knew it before."

"Indeed; then why didn't you tell me at once?"

"I wanted to be certain."

"Well?"

"When you were away a month ago, her mother sent for you."

"Violet Graham's mother?"

"Yes."

"You went to her?"

"Yes."

"Well?"

"She told me a rambling story about an inheritance that should come to her daughter, of which she believed that Violet was being defrauded."

"By whom?"

"Parties in England."

"Well?"

"She wanted you to look the matter up, but her story was so wild and her own manner so strange, that I concluded that she was raving and paid but little attention.

"Go on."

"She gave me the name of a lawyer in town, who, she said, could tell me a great deal if I could make him talk."

"You went to see him?"

"No."

"Why not?"

"I promised to do so the following day, but that very afternoon Violet herself called at the house."

"Ah!"

"She inquired for you, and of course I represented you."

"Of course."

"She told me that her mother had told her of her interview with me."

"Humph!"

"She said that her mother was not quite sound on that one topic, and that while it might or might not be true that she, herself, was an heiress to a fortune, she preferred to let the matter rest as it was."

"I see."

"In other words, she very decidedly told me to drop the whole thing right there."

"Did she give any reason?"

"No, none."

"And you dropped it?"

"Certainly."

"Well, go on; you haven't finished."

"No."

"Give me the rest."

"To-day I looked up the lawyer."

"What is his name?"

"Dunlap."

"You saw him?"

"Yes."

"And questioned him?"

"Yes."

"Well?"

"First, he wouldn't talk. Finally he admitted that there was an estate in England to which he believed that under certain circumstances Violet Graham would have had some claim.

"'However,' said he, 'those circumstances have not arisen.'"

"Well?"

"I tried to get particulars, and could not."

"Did you ask him in what way he was connected with the matter?"

"Yes."

"What did he answer?"

"Simply that he was employed by Mr. Winthrop to take care of his interests.

"'Who is Mr. Winthrop?' I asked.

"'My client,' he replied.

"'In this matter?

"'In many matters."

"'Does he own property in New York?'

"'A great deal.'

"Then I came away."

"Winthrop—Winthrop," mused Nick. "Go on, Chick."

"I made up my mind that Dunlap was a shyster, and if there is any deal, he is not only in it, but he is also shrewd enough to keep away from the fly-wheel."

"Watch him, Chick."

"I will."

"We will find Violet first—if she is alive—and go for the property afterward."

"All right."

"Look at this, Chick, and tell me what you think of it," and the detective handed his assistant the note that he had picked up on the street.

"This is the clew," exclaimed Chick.

"Yes."

"Are you going to bite?"

"I am"

"It's dangerous."

"All the better."

"You will go to Sleepers pier to-night?"

"Yes."

"Will you take me with you?"

"No."

"Patsy, then?"

"No."

"What do you want me to do?"

"Shadow Winslow."

"Do you think that he is in this plot?"

"I know it."

"Ah!"

"He is a fraud of the first water, and I will make a shrewd guess."

"What?"

"I believe that Winslow and Winthrop are one and the same, and that he is the leading spirit in this game of plots. He has in some way tumbled to Violet's inheritance and worked the other end, so that he has only to get rid of her to own it.

"In the meantime, he is using her as a decoy to draw me, for you will find that he is the leader of the 'Thirteen' vice Dr. Quartz, deceased."

IT was exactly eleven o'clock that night, when a man who bore every appearance of what is known as a "South-street rounder," staggered rather than walked out on Sleepers pier, which juts out about five hundred feet into the East River, a little distance above Catherine street.

He was one who unquestionably belonged to the genus "tough," if he might be judged by his appearance.

But appearances are often deceptive, and this case was an instance of that fact.

Beneath the dilapidated coat beat the heart of the indomitable Nick Carter.

He had taken the villains at their word, and had accepted the challenge so strangely given.

He was on Sleepers pier for the purpose of boarding the tugboat Roarer.

He was determined that if Violet Graham was to be a passenger of the tugboat that night, he would be one also.

It must not be supposed that he belittled the danger to which he would be exposed in his adventure of that night.

But Nick was accustomed to danger. He liked it.

His phenomenal luck in always coming safely and well out of every calamity had imbued him with a fearlessness which was akin to recklessness, although that was thoroughly qualified by caution.

Staggering as though very much under the influence of liquor, he made his way out upon the pier.

He had purposely calculated his time, in order to be an hour earlier than that set by the villains whose object it was to decoy him there.

That hour he meant to employ in characteristic investigation.

There was no sign of life upon or near the pier.

Back of him, and along South street, the world seems never to sleep, and only grows more rampant when night draws its curtain to hide the deviltry that is afoot.

Moored to the pier were two tugboats, one on either side.

In the light which shone out from the street, Nick could see, in large, white letters, the name Roarer, upon the stern of the one on his right.

He glanced at the opposite, and smiled when he read the name Demijohn.

"Boon companions," he muttered, "Roarer and Demijohn."

The Roarer seemed as tenantless as the pier.

He paused for an instant when passing that part of the boat where the engine-room was located, and detected the slight sounds which denoted that she had steam up, and was ready for instant use.

Then he continued his way to the end of the pier.

It was a lonely spot, there on Sleepers pier, and one well calculated for any kind of villainous work.

Nick selected a place where he was half-concealed by one of the piles, and there for twenty minutes he waited and watched.

Nevertheless he saw and heard nothing.

No one ventured upon the pier, nor was there any sign of life upon either of the boats.

It is true that his attention was solely occupied in watching the Roarer. Nevertheless he now and then turned his eyes toward the Demijohn.

It was half-past eleven when he again stole along the pier toward the latter, and he quickly perceived that she also was carrying a full head of steam, as if prepared to move at a moment's notice.

Whether this fact was a mere coincidence, or whether his enemies intended to make use of her as well as of the Roarer, he had no means of knowing.

He inclined, however, to the former theory.

After watching the boat for a moment, he suddenly sprang from the pier to her deck.

He knew that if he was expected at all, they were looking for him upon the other boat, and that he ran little or no risk in boarding the Demijohn.

Nick was keen-sighted, and, perhaps, the most difficult man in the world to shadow.

Nevertheless he was shadowed when he went out upon that pier, and a pair of eyes had patiently and intently watched every move that he made, although he was totally unsuspicious of the fact.

It is true that the "shadow" seemed perfectly satisfied to keep well in the background, and that he had not once shown himself where Nick could by any possibility be expected to discover him.

It is also true that the detective had not been shadowed previous to the moment of his arrival at the shore end of the pier.

Those eyes were lurking there when he came, and their owner did not move from the position he had selected.

The Little Giant leaped upon the deck of the Demijohn near the pilot-house, and then made his way cautiously aft, along the starboard side—that is, the side nearest the wharf; for she, like the Roarer, lay with her bow pointing toward the river.

He discovered no evidences of occupancy, until he was passing the engine-room.

There he managed to peer through a window into the interior, and saw the engineer asleep in his chair.

He continued on his way, and so made the entire circuit of the boat discovering nothing.

Suddenly an idea occurred to him which he determined to follow, and that without delay.

To carry it into execution, he again went to the starboard side of the tugboat, pausing when he reached a point about amidships.

From the place where he stood to the end of the pier, was not more than fifty feet, and he had determined to swim from the Demijohn to the Roarer.

He would thus be enabled to approach the tugboat, the real object of his adventure from the water-side.

He reasoned that in that.way he could escape observation, and could examine the boat thoroughly, without discovery from any one who might be watching his movements from the shore.

Exercising great caution, in order that no splashing might betray his movements, he lowered himself over the side into the water.

Then he struck boldly out.

The tide in that part of the East River runs about seven miles an hour, a dangerous current for a swimmer to oppose.

But Nick did not give the subject a thought.

He reached the end of the pier, rounded it, and swam in, to the Roarer, without accident.

Then he climbed aboard.

Cautiously he crept aft, peering into every window, and listening at every step.

He saw nothing, and heard nothing.

Then he went forward.

The pilot-house was as empty as the rest of the boat.

So far as he could determine, there was not a sign of life to be seen or heard anywhere about him.

"If I was seen to go upon the pier," he thought, "I was, of course, observed when I boarded the other tugboat.

"But I am certain that no one can have any suspicion that I am here."

There was one, however, who did suspect it, and that was he who was hiding among the casks at the shore end, and who had watched every move the detective had made, until he had disappeared aboard the Demijohn.

He waited a long time for Nick to reappear, but, as the reader knows, without result.

Presently he grew impatient.

Next he stole forward toward the point where Nick had disappeared, keeping in the shadow as much as possible, until he also went over the side of the pier onto the boat.

His manner of investigation was almost an exact copy of that of the detective.

He made the circuit of the boat, peered into windows, and listened, as the detective had done.

But unlike Nick, after finishing his first tour, he began a second.

This time he bent his energies to a careful examination of the rail which surrounded the boat.

Whatever it was that he was searching for, he seemed to meet with no satisfaction, until he arrived at the point where Nick had lowered himself into the water.

There he evidently made a discovery.

Suddenly he pulled something from his pocket, and grasping it in his right hand, leaned down over the water.

A sharp ray of light illumined that point of the tugboat's hull.

He had made use of a bull's-eye lantern.

One glance seemed to satisfy him.

The slide of the lantern was not open a half-minute of actual time, and yet the man uttered a low exclamation of satisfaction as he closed it, and straightened up again.

For fully five minutes he stood thus, as silent as a statue, either waiting or thinking.

Then suddenly he turned and went rapidly to the engine-room door.

He did not knock upon it, but pushed it open, entered, and closed it behind him.

Aboard the Roarer Nick was still unable to discover anything of a suspicious character.

It was about a minute after the unknown had entered the engine-room of the Demijonn that Nick crept cautiously around the pilot-house of the Roarer, and secured a position where he could see along the pier toward the shore.

Two minutes later he saw three men approaching.

They came directly to the Roarer, and sprang aboard.

At the same instant a hack, drawn by two horses, was driven rapidly upon the pier, and far in the distance he plainly heard some clock toll the hour of midnight.

The hack drew up, and stopped close to the Roarer.

Its door flew open, and four men leaped out.

Then one of them turned, and pulled from the carriage something which in the darkness might as well have been taken for a bundle of clothes as a human body.

There had been two men upon the box of the hack.

One of them remained there, and drove rapidly away, as soon as he was clear of his passengers.

Then two of the men seized the burden, and leaped with it aboard the tug.

The remaining three sprang to the lines, and cast them off.

Somebody uttered a shrill whistle, the tug's propeller began to revolve, and she darted like a bird out into the river.

It had all taken place so quickly that not more than one full minute had elapsed from the time the hack was driven upon the pier, until the Roarer had left it.

Had Nick wished to get ashore, he could not have done so without being discovered.

But he had no idea of leaving the boat. He had seen enough to convince him that his place was there.

In that brief moment he decided that the men had no idea that he was there.

But he little knew how thoroughly they understood the character of Nick Carter.

They played upon his well-known daring, as they would have played upon another man's caution.

Nick Carter was never in his life in greater danger than at that moment.

NICK remained where he was hidden at the bow of the tugboat, when she left the pier, for the simple reason that he could not change his position without being discovered.

Even then it seemed as though he must be seen.

But either the men did not or would not see him.

At all events, he was left undisturbed where he lurked beneath the windows of the pilot-house.

From his position he could not see that the Demijohn had also gotten under way.

But she had.

She left Sleepers pier not more than a minute behind the other boat.

The Roarer turned southward, heading toward Buttermilk Channel.

The Demijohn turned southward also, but headed for the Battery.

Thus with their wakes the two tugboats formed a fair representation of the letter V.

An experienced boatman would have noticed instantly that of the two tugs, the Demijohn was the faster.

She gained upon the other boat so rapidly that by the time Governor's Island was reached, she was considerably in advance of the Roarer.

The mysterious individual who had acted so strangely upon the pier, and who had so silently entered the engine-room of the Demijohn, was now in the pilot-house, with his hands grasping the spokes of the wheel.

Otherwise, there was not a human being in sight aboard of her.

On the Roarer, all seemed to go smoothly.

Nick felt that his luck was more phenomenal than ever, in the fact that he had not been discovered, when it seemed impossible to escape observation.

In the pilot-house above him were two of the men.

He could hear them talking together, and gathered much of their conversation.

"This is just the night for our work, Bill," said one of them, soon after the boat left the wharf.

"Ye're right, Jimmy, it is that," replied the other.

"Do you s'pose Byrnes has got onto us?"

"Not much, he ain't."

"Well, I ain't much afraid O' him an' his men."

"I ain't afraid of none of 'em."

"Not even Nick Carter?"

"No, nor a dozen like him."

"I say, what's the cap going to do with the gal, anyhow?"

"Cut her throat, most likely."

"Mebbe that's what we're goin' out in the boat for."

"Sure."

"So he can tie a shot to her heels and chuck her overboard in the lower bay."

"That's about the size of it, I guess."

"Tell you what, Bob—"

"Well, what?"

"I think we've missed a good chance to-night."

"How so?"

"We've sworn to get away with Nick Carter, haven't we?"

"You bet."

"Wouldn't it have been a good idea to have given him a tip to-night?"

"What do you mean?"

"Suppose we had let him know we were going on this trip."

"What! with the gal?"

"Yes."

"That would have been a fine idea, that would."

"You don't tumble, Bob."

"Mebbe I don't."

"He would have followed us here; he would have been aboard this boat, and we would have had him dead to rights."

"Not much, we wouldn't."

"Why?"

"He'd have had a hull bilin' of cops with him."

"Not he. You don't know him, Bob."

"Don't I, though! Ain't my jaw been crooked ever since I met him?"

"Did he have a bilin' O' cops with him, then?"

"No."

"He never does have. He always goes it alone."

"That's so, by Jupiter!"

"We ought to have enticed him here, somehow."

"You're right, Jimmy. You always are."

"What're cap an' the others doin', Bob?"

"Oh, they're holdin' a confab."

"Where?"

"In the cabin, aft, where the gal is."

"I think I'll join em."

"All right. So long—"

"So long, Bob."

The pilot-house door opened and closed, and Nick heard Jimmy's footsteps as he hurried aft.

"I guess I'll be in at that little confab," he muttered, and he also made his way toward the cabin.

"During the time that had elapsed while the men were talking in the pilot-house, the Roarer had reached Buttermilk Channel and passed through it.

Thus, when Nick started aft toward the cabin, they were just rounding Governor's Island, and ahead of them, off the starboard bow, was the Demijohn.

As Nick moved aft, two other men rose up from the darkness of the pilot-house, and leaning forward, they cautiously peered from the window toward that part of the deck where Nick had been crouching.

"Did he bite?" asked the one in the background,

"Like a mice."

"Then we've got him."

"He's as good as dead now."

"Come on, then."

They followed in the footsteps of Jimmy, but moved along noiselessly, knowing that the man whose life they were seeking, was on the opposite side of the boat.

When Nick reached the cabin, which was a very small affair, he could hear the murmur of voices inside.

He looked about him for a place from which he could hear what was being said.

He found one at once.

Had the boat been built with an idea of the use to which he desired to put it, she could not have been better planned.

The cabin door could be plainly distinguished.

He first placed his ear against that, but he could not hear distinctly enough to suit him.

Then he remembered having seen another door close by that which led into the cabin.

He turned and tried it.

It was unlocked.

Exercising great care, he pulled it open and peered in.

The interior was a little room, in which part of the crew evidently slept.

More than that, he saw at a glance that it connected with the cabin in which the men were talking, and he could hear them plainly.

With quick decision he passed through, and pulled the door noiselessly shut behind him.

From the sound of the voices he quickly determined that there were four men in the cabin, who were engaged in the conversation.

Instantly he wondered what had become of the other three who should have been there.

A moment's thought convinced him that they were doubtless with the others, but were not taking part in the talk.

"Well, cap," said one of them, when Nick was enabled to catch the words they were uttering, "we've made a great strike this time."

"You bet."

"What are you going to do with the girl?"

"Sink her in the lower bay."

"A good scheme."

"So I thought."

"How much do we get apiece out of this job?" asked another.

"About a hundred thousand."

"Whew!" exclaimed the third, "then there over two millions in the whole thing."

"There is."

"You get a million for your share."

"Yes."

"And we divide twelve hundred thousand, eh?"

"Precisely."

"I thought the eleven thousand was a pretty good haul, but it wasn't a flea bite."

"Nixy."

"What about Carter?"

"What Carter?"

"The detective."

"Oh! Why?"

"Well, ain't we organized to 'do' him?"

"Cert!"

"We want to do it in good shape."

"You bet."

"How'll we do it."

"We might send him to the bottom with the girl."

"Yes, if he was handy."

"He will be sometime."

"I say, cap."

"What?"

"When will we 'do' him?"

"Now."

It was not the captain who answered, but seven distinct voices.

Four of them came from the cabin, and three of them from behind the spot where the detective was listening to the conversation.

The moment the first sound of a voice in uttering the word "now" reached him, Nick knew that he had walked into a trap that had been most skilfully planned.

In that instant he leaped away, even as the men leaped upon him.

Two of them seized him, but he wrenched himself loose and shot them both.

One fell dead, and the other, wounded, drew his pistol, and began firing.

In the meantime the remaining five, with a courage that would have been notable in a worthy cause, threw themselves upon the detective.

One grabbed him by the legs, and the others seized upon various parts of his body, and he was borne downward in spite of all that he could do.

Not, however, before he had fired his revolver twice more, and had brought two more of the miscreants to their knees, wounded.

But they were too many for him, and, in spite of his struggles, he was firmly bound.

Then one of them stood over him with a knife in his hand.

"Drop it, Carter, 'r I'll just cut out your tongue for a beginner," he said, savagely.

Nick saw that he might as well save his strength, and so he ceased his struggles.

Suddenly the bell in the engine room began to ring furiously.

It rang four times, loudly and quickly.

Then it ceased a moment, and then four more clangs.

There was no one in the engine room to obey the signals. The man whom Nick had killed at the first shot was the engineer.

There was not another man there who knew how to manage the engine.

Again the bell rang four times.

It was the signal from the pilot to stop and back up.

It was followed by a dozen short, sharp blasts from the whistle.

The men left Nick lying upon the floor of the cabin and rushed upon the deck.

The reason for the signals was instantly apparent.

The Demijohn was bearing down, head on, upon the Roarer.

She was coming at full speed, and it could be seen that she meant business.

The pilot of the Roarer had at first tried to stop his boat.

Receiving no answer to his signals, he had endeavored to sheer off.

But he did not make the attempt soon enough.

Both boats were going at full speed, and they were so headed that the bow of the Demijohn must strike the Roarer a little forward of amidships.

On came the Demijohn.

There was but one man visible aboard of her, and he stood grimly at the wheel.

"Curse that pilot!" shouted the man who had been called "cap."

He raised his revolver, took careful aim, and fired, just as the two boats came together.

There was a terrific shock, followed by the crashing of timbers and glass, and the loud hiss of escaping steam, while ringing out. high above the din, was the shrill scream of a woman's voice.

It came from a figure that bounded from the cabin-door just as the boats struck together.

The Roarer was turned almost completely over, while the prow of the Demijohn cut her nearly in half.

She, too, careened until it seemed as though she must topple over and be capsized, and in the midst of that wild scene—amid crashing timbers, breaking glass, hissing steam, and the curses and mad shouts of men, the woman leaped into the air, and seized the rail of the Demijohn.

There she hung, half-submerged in the water, unseen or uncared for by all.

Then, and it came so suddenly that it was appalling, the Roarer toppled over still farther, and, as if swallowed up by magic, disappeared beneath the surface of the bay.

The Demijohn seemed to try to plunge after, like an animal which is not satisfied with killing its foe, but seeks to worry it after it is dead.

But she quickly righted and floated upon the water, undamaged, except that a goodly portion of her bow above the water-line had been knocked away.

Then, the man at the wheel left his post.

He bounded to the deck.

"Save me! Save me!" cried the woman, who still clung to the rail.

He seized her almost savagely, and drew her upon the deck. Then with the same savage air, he pushed her into the pilot-house.

"Wait there!" he said, abruptly, and then he turned back and searched the water with his eyes.

He was Chick, and he was looking for Nick Carter.

CHICK was looking for his master.

He was searching for Nick Carter.

It was Chick who had been concealed among the casks at the shore end of the pier, when the Little Giant was making his investigations of the two boats.

It was Chick, who, when Nick did not reappear, after boarding the Demijohn, had gone in search of him.

With the aid of his bull's-eye lantern, he had arrived at the correct conclusion as to what Nick had done in order to get aboard of the Roarer. Some explanation regarding Chick's presence there seems imperative.

It will be remembered that in the connection between the two detectives on Broadway, Nick had signified his intention of visiting the tugboat that night, no matter what the risk might be.

Also that he had given Chick orders to shadow Winslow. But Chick could not rid his mind of the settled conviction that Nick Carter was rushing with open eyes into a danger greater than any he had ever faced.

The belief took such firm hold of him, that he resolved, come what might, that for once he would disobey his instructions and do as he pleased.

What he pleased consisted in going at once to the Battery, instead of toward the residence of James Winslow, in Forty-seventh street.

At the Battery, or rather near it, and adjoining South Ferry there were many tugboats moored. Chick went about among them, until he selected one that suited him.

Then he sought the captain.

"I want to charter your boat," he said.

"What for?"

Chick looked the man over thoroughly, and he came to the conclusion that he was the sort of man that he could trust.

Having so decided, he told him in plain words, exactly what he wanted of the boat, and why he wanted it.

Then in conclusion, he offered the captain a very large sum for the use of the boat, and agreed to pay all damages. There was only one impediment, and that was that he had let all of his men go for the day, and he had no crew.

Chick, however, speedily assured the captain that if he would manage the engine and fire, he (Chick) would attend to the wheel.

It took two or three hours, and many promises to effect the bargain, but it was finally concluded, and the Demijohn pulled out for Sleepers pier.

About ten o'clock, Chick took his position among the casks and waited.

The rest we know.

When the two boats left the pier, Chick at once discovered that his tug was much more fleet than the Roarer, and he governed himself accordingly.

His idea was to keep near to the Roarer so as to be ready to go to Nick's assistance at any moment.

He believed that he could judge by appearances whether he was needed or not, for he knew that Nick could never be captured without some kind of a fight which he could see or hear.

In the event of there being none, he was simply determined to follow the Roarer wherever she went and await results.

When the pistol-shots rang out, he understood that he was needed at once.

Without hesitation, he turned the prow of the Demijohn full upon the Roarer, and ran with full speed.

His deliberate intention was to run her down, and he succeeded.

Chick's confidence in Nick was such, that he did not for a moment doubt that the Little Giant would be able to take care of himself when the collision occurred.

But he did not calculate upon the Roarer's sinking so suddenly.

All the while that he stood at the wheel of the Demijohn, when the men on the Roarer rushed upon her deck shouting and cursing, Chick's eyes were searching for Nick.

He hardly saw the others, so intent was he in his search for the one person for whose sake he was there.

But he did not see him.

Of all who were on the Roarer, but one person reached the Demijohn, and that was the woman to whom we have referred.

Chick scarcely noticed her.

He did, indeed, seize her, help her to the deck, and thrust her into the pilot-house.

Then he hurried back again to the boat's rail.

The night was not very dark, but yet one could not see distinctly.

Some distance away, he saw a boat with four men in it, rowing away, but he scarcely heeded it, still searching for a sign of Nick.

A great fear was at his heart.

Had he known that at the moment when the boats collided, Nick was lying bound and helpless in the cabin of the Roarer, he would have felt like his murderer.

But fortunately he did not know it.

He believed that Nick had been drawn down when the tugboat sank, and that he would presently rise to the surface.

But moment after moment passed, and he did not appear.

Then he bethought himself of the small boat that he had seen.

He turned to look for it, but it had disappeared.

Then an icy fear settled upon him.

What if one of the pistol-shots that he had heard had been the signal of Nick's death?

What if a bullet had struck him, and he had been drawn down to the bottom of the river with the sinking tug.

Had he known Nick's real condition, he would have been horrified.

But he did not.

He almost forgot where he was, so intent was his gaze and so earnest his search for the missing detective.

But he was recalled to himself by a sudden cry from the captain of the boat, who stood in the engine-room.

"Look out!" he cried.

Chick wheeled.

It was well that he did.

The woman that he had saved was just behind him.

In her hand she held a dagger poised, and she was in the act of striking when he turned.

Quicker than a flash, he seized her by the wrist, and the dagger dropped from her hand to the deck.

"Ah!" said Chick, himself again in an instant. "A delicate attention that you were paying me."

"I would have killed you," she hissed.

"I don't doubt it, my dear; but why?"

"Because you have killed him."

"Oh! who is 'him?'"

"My husband."

"Was he on that boat?"

"Yes, you villain."

"Well, I hope I did kill him."

"Curse you, curse you!"

"Thanks; do you see that water?"

"Am I blind?"

"I'm sure I don't know. Do you see it?"

"Yes."

"Do you want to be tied hand and foot and thrown into it?"

"You would not, you dare not do that."

"Well, I don't know. I'm savage enough to do most anything just now."

"Oh, sir—"

"Look here, didn't you just try to murder me?"

"Oh, sir, I—"

"Answer me."

"Yes, sir."

"Wouldn't I be justified in chucking you overboard?"

"Yes, sir."

"Well, it depends upon you whether I do or not."

"Upon me?"

"That's what I said."

"How, sir, how?"

"If you will answer every question that I ask you truthfully, I will not only spare you, but I'll let you go when we get ashore."

"I will."

"Who are you?"

"Madge Morton."

"Ah, the pickpocket!"

"Yes,"

"What were you doing on that boat?"

"Playing a part."

"Were you the girl they took from the hack?"

"Yes."

"Where is Violet Graham?"

"I don't know."

"Did you ever see her?"

"No."

"I wish I could believe you."

"I am telling you the truth."

"Do you know of an organization called the 'Thirteen?'"

"Yes."

"Do you know the members?"

"Two of them."

"Is that all?"

"Yes."

"Is your husband one?"

"Yes."

"What is his name?"

"Jim Morton is one; he has a dozen."

"You were the decoy to-night?"

"Yes."

"Did you see Nick Carter?"

"No."

"You knew he was there?"

"Yes."

"All the time?"

"Yes."

"Where were you when the fight began?"

"In the cabin."

"Where was the fight?"

"In a little room off."

"Do you know what became of the detective?"

"I am not certain."

"Have you an idea?"

"Yes."

"What is it?"

"I know that he killed one man, the engineer, and he wounded others. Just before the men rushed out on deck, I heard a smashing like a door being kicked in."

"Yes—well?"

"I heard one of the men cry out: 'Curse him, he has got away again.'"

"You did, eh?"

"Yes."

"How do you think he got away?"

"I think he jumped into the water on the other side of the boat."

"Madge, why do you pick pockets?"

"To get a living."

"Don't you want to earn some money honestly?"

"I don't know."

"You wouldn't give your husband away, I suppose?"

"Never."

"Well, give him the tip and let him skip, and then give away the rest of the gang."

"I'll think about it."

"I'll pay you well."

"How much?"

"A thousand dollars."

"It isn't enough."

"How much do you want?"

"Five thousand."

"What will you do for that?"

"I will give 'em all away, Jim and all. I'll take you where you can capture the whole lot together, and I won't claim a cent till its done."

"Madge, it's a bargain."

"You agree?"

"Yes; when will you do it "

"Leave that to me.'

"All right. When shall I see you?"

"To-morrow night."

"Where?"

"Anywhere."

"At Grafferty's, then."

"All right."

"What time?"

"Any time you say."

"Very well—midnight."

"No treachery, Madge."

"No—no! I'm looking for the dollars."

"All right."

FROM the story that Madge had told him, Chick was satisfied that Nick had managed to escape from the Roarer, when the collision occurred, and he believed that he would find him at home when he reached there.

But the brave young detective was doomed to disappointment.

Nick was not there.

Still, the faithful assistant did not permit himself to become anxious about his chief.

But when the entire day passed and there came no news of the Little Giant, Chick began to grow uneasy.

He knew that only one of two reasons could exist for keeping Nick so long away from home, without sending some sort of word regarding his absence.

Either the detective was following some clew which had taken him where it was impossible to communicate with Chick, or he was prevented from returning home through some accident which had placed him in the power of his foes.

It is true that the idea occurred to Chick that his chief might be dead; but he dismissed it at once, and with self-indignation that he should even conceive such an absurdity.

It was fortunate for his peace of mind that he did not know the true condition of things on board the Roarer, when the collision occurred.

All that day Chick waited patiently for Nick to appear.

When ten o'clock struck that evening, he was in a quandary.

"It will take me an hour to get from here to Grafferty's," he mused, " where I am to meet Madge at midnight. I will wait for Nick until eleven, and then I will go."

At eleven Nick had not come, and Ethel had begun to grow anxious.

Chick, however, pooh-poohed her fears, and after leaving a message for Nick, in case he should return, he set out to keep his appointment with the female pickpocket.

Grafferty's place was in Cherry street. It has since been raided, and effectually done away with.

Then, however, and it was only a very short time ago—the word Grafferty was synonymous with all that was evil.

His den was the hot-bed of various vices, and the more horrible and revolting they were, the better they flourished there.

To go to Grafferty's as a stranger and dressed as a gentleman, meant to go to one's death.

The bartenders were ever ready to administer "knockers-out," which is a slang term for the drugs which those fiends employ. They may only render a person insensible or stupid, but usually they kill.

Murderers were there, ghouls, "doctors' assistants" (a class of men who make their living by procuring bodies for unprincipled medical students, and who are not always particular whether the subject is alive or dead when they decide to take it), robbers and thieves of all classes, fallen and abandoned women of the worst types, procuresses, pickpockets, and confidence women, who, when they could not fleece their victims in any other way, resorted to the panel game.

There was no worse place in New York than Grafferty's, where Madge, the pickpocket, had agreed to meet Chick.

That her appointment might have been made for the purpose of luring him there to kill him he well knew.

Nevertheless, he did not hesitate.

It was exactly midnight when he opened the door and staggered into the immense saloon—a room which by the uninitiated was believed to be the place where all Grafferty's business was done.

But there were rooms up stairs which could have told many a horrible tale of revolting crime.

There was a huge cellar beneath, which concealed many a mystery which would never be revealed.

There were trap doors, mysterious closets, false partitions, movable panels, hidden stair-ways, and all the ingenious devices which rendered possible the crimes that were committed there.

Chick had never been into the place farther than the big saloon, and yet he knew pretty well what sort of a place it was.

His disguise was that of an old sailor—for sailors gave Grafferty much of his custom.

There were, perhaps, a hundred people in the room when Chick entered, and they were about evenly divided in regard to sex.

All were drinking, some were listening to the war songs, sang by coarser artists (?) upon the stage at the far end of the room.

Chick staggered to a table, called for a drink, and sat with it before him, looking blear-eyed and sodden.

Nevertheless he carefully studied every person there.

Presently he saw Madge.

She was sitting alone, at a table in one corner, where she seemed to be waiting for somebody.

Chick studied her narrowly, and watched every movement that she made.

His object was to let her think that he had failed to keep the appointment, and thus to discover if she meant to betray him.

When man after man, until seven different ones had been there, had approached her and been dismissed, and one o clock had struck, Chick staggered toward her.

"Are you ready to talk business?"

"Yes."

"Are you prepared to give the 'Thirteen' away?"

"Yes."

"The whole gang?"

"Every one of them."

"And take your pay when it is done?"

"That's what I agreed to do."

"Did you tell me the truth last night about Nick Carter?"

"I told what I thought was the truth, then."

"Have you since found out that you deceived me?"

"Yes."

"Didn't Nick Carter escape, after all?"

"I don't know whether he did or not," she answered, slowly.

"Tell me what you do know."

"Nick Carter was bound and helpless when the collision took place."

"What became of him, then?"

"I don't know."

"How many men were there on the tug who were members of the 'Thirteen?'"

"Seven."

"Did any escape?"

"Yes."

"How many?"

"Only three."

"Who were they?"

"The captain and two others."

"What were their names?"

"Long Tom and Shorty."

"What is the captain's name?"

"I can give you the one that I first knew him by."

"What was that?"

"Bouncer Bob."

"Ah! I think I remember him. He came from California with Dr. Quartz, didn't he?"

"With Paul Dangerfield; was that Quartz?"

"Yes."

"That's him, then."

"You have seen one of the men who escaped to-day?"

"Yes."

"Which one?"

"Bouncer Bob."

"Where is he now?"

"Somewhere in the place."

"In this house?"

"Yes."

"You must put me onto him pretty soon."

"I will if I can"

"Now, what did Bob tell you?"

"Not much."

"How did he escape?"

"When he saw that the tug was bound to sink, he jumped for it, and Long Tom and Shorty followed him."

"They got away?"

"Yes."

"Well?"

"I tried to find out what became of the detective."

"Well?"

"Bob said he was dead, but from the way that he talked, and the way he looked when he said it, I am satisfied of one thing."

"What is that?"

"Nick Carter may be dead, but I believe that Bouncer Bob either saw him alive and comparatively well after the tug sank, or else—"

"Well, or else what?"

"Or else he saw his ghost."

"Which isn't at all likely."

"No."

"Then you think he is alive yet."

"I don't know. I think that Bouncer Bob would kill him the first moment that he could."

"NOW, Madge, to business! I see that you can't tell me anything about my friend, and that I will have to find him for myself. When do you propose to work this little racket, which is to give the whole thing away?"

"To-morrow night."

"Why not to-night?"

"It is too late."

"To-morrow night will certainly be too late."

"Why?"

"Because I must save my friend."

"If he's alive now, he'll be alive, then?"

"Perhaps."

"I know it."

"How do you know it?"

"I know that Bouncer Bob would kill him the moment that he had him in his power, unless—"

"Well, unless what?"

"Unless he believes that he has got him safe, and means to kill him by degrees."

"My God! do you mean by torture?"

"I know that Bob delights in starving people. He considers it to be the best kind of torture. If he could get your friend where he knew that he could not get away, he would leave him there to starve."

"Then you think that he has him imprisoned somewhere?"

"That is my idea."

"Where?"

"I cannot guess."

"Where will they be to-morrow night?"

"Here."

"At Grafferty's?"

"Yes."

"At what time?"

"They meet at midnight."

"Four are dead."

"Yes."

"Therefore there will be only nine for me to capture."

"That's all."

"Jim, your husband, was not the captain, then?"

"Yes. Jim is one of Bouncer Bob's names."

"I see; and you are willing to betray him?"

"Perfectly."

"Why?"

"That's my business."

"Tell me a few of Jim's names."

"He's James Winslow, Judge Winthrop, Jim Morton, Bouncer Bob, and Skinner."

"Good; now, where is Violet Graham?"

"Dead."

"What makes you so certain? Did you see her die?"

"No."

"What then?"

"I gave her the stuff that killed her."

"What!"

"Well, 'twas this way. Maybe you'll say I did wrong, but not to my way of thinking, anyhow."

"I am listening, Madge."

"Jim and two of his cronies got away with her—"

"How, Madge?"

"They told her that her mother was in a hack on the corner. She went and looked in. I was dressed up as her mother, and Jim was in the hack with me. When she looked in I grabbed her, and Jim slapped a lot of chloroform over her face."

"Well?"

"Then we brought her here."

"Here!"

"Yes. Jim promised that no harm should come to her. I'm about as bad as they make 'em, but I never helped to bring a woman down to my level—never."

"I'm glad to hear that, Madge."

"Jim promised to be good, but Violet was beautiful and he got 'stuck' on her."

"I see."

"He was bound that she should marry him, but he knew that I was Jim's wife. Well, he got wild, and then I knew that she was in terrible danger."

"I took pity on her, sir, and I told her all."

"Go on."

"When she knew what was in store for her, and realized that there was only one way to escape, she begged me to help her."

"It wasn't one man, but four that she had cause to dread. She begged me on her knees to get her some poison, end I did."

"Tell me the rest, Madge."

"I got her a little vial of prussic acid. I gave it to her. That night when they went to the room where she was a prisoner, she was dead."

"This is horrible, Madge."

"It is the truth."

"Didn't I do right?"

"God alone can answer that. I cannot blame you."

"Thank you, sir."

"What did they do with her body?"

"That's a strange part of it."

"Why?"

"Well, there are lots of dead bodies in this place one time and another."

"Yes."

"And they all go through the sewer into the river, but hers didn't. Jim wanted to save the body where he could find it again for some reason. He had her embalmed, and then she was taken in a carriage to a place over in Jersey."

"Where?"