RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"HELP! Oh, help me!! Murder! murder!!"

IT was a wild and startled cry that rang out upon the affrighted air just as the town clock was striking midnight.

It was the voice of a woman that uttered the loud appeal for assistance, and two young men who were in the act of parting at a corner upon the outskirts of the village, heard the shrieks, and paused, even as their hands clasped in the act of bidding each other good-night.

"What was that?" gasped one of them, in a husky tone.

"A woman's voice."

"From the cemetery, wasn't it?"

"Yes."

"Come on, then," and he dashed away in hot haste, followed by his friend.

The corner where they had been standing was only a short distance from the village cemetery, from whence the cry had seemed to proceed.

The cemetery was, however, surrounded by a high stone wall, the entrance gate being a considerable distance farther up the road.

It was toward that point that the young men sped.

But they were destined to be too late.

They were still some distance from the gate-way, when a closed carriage dashed through, turned abruptly to the right, and rolled away rapidly toward the cemetery.

"Too late," muttered the young man, in advance.

The night was very dark.

The sky was hidden by heavy, inky clouds, so that not a star made its appearance.

To have followed the rapidly moving vehicle on foot would have been, even in daylight, next to an impossibility; under the circumstances it was entirely so.

Both young men paused, just in front of the cemetery gate.

"Come," said the one who had led the chase. "We must go in here."

"In there?"

"Yes."

"Ugh!"

"Are you afraid?"

"No—but—"

"But what?"

"What's the use?"

"We must find out what has been done here to-night."

"Why?"

"Because it is our duty."

"We can't see a thing."

"Yes, we can."

"How? It's darker than pitch in there,"

"I've got a light."

"Yes."

"Where?"

"In my pocket."

"What kind of a light?"

"This."

As the young man spoke, he drew forth a marvelous little bull's-eye lantern.

By simply touching a spring the slide flew back, thus permitting a brilliant stream of light to escape.

"You're a queer one to be carrying such a thing as that around with you," ejaculated his friend. "What on earth do you do it for?"

"For just such an occasion as this. Now, Frank, don't ask questions, but come with me."

"Where are you going?"

"Into the cemetery."

"What for?"

"To find who is missing."

"Missing from a cemetery!"

"Yes."

"What do you mean?"

"Did you ever hear of ghouls, or body-snatchers?"

"Yes."

"I think they have been here to-night."

"And stolen a body?"

"Yes."

"Bodies don't screech and cry help and murder."

"True. Are you coming?"

"Yes; where to?"

"To the vault of the Lawrence family."

"The Lawrence family?"

"Yes."

"Ah, you think it is the body of Dora Lawrence that has been taken!"

"Yes."

"How do you account for the cries?"

"I don't."

"Oh!"

"That's just what I want to do."

"Why not report the thing and have done with it?"

"I wish to investigate it myself."

"Why do you think that it was Dora Lawrence whose body they took?"

"I have several reasons."

"She was only put into the vault this morning."

"Exactly."

"You're a queer fish, Cheever."

"I know it."

"Well, fire away. I'll go with you, and you can explain afterward."

"Thanks."

They soon arrived at the vault.

It was not very far from the main entrance, the two young men being only obliged to traverse the winding roadway less than an eighth of a mile before they came to a halt before the heavy iron grating which formed the door of the vault.

"I say, Cheever, what's that?" asked the one called Frank, pointing at a white object which lay upon the ground near the vault door.

Cheever bounded forward, and picked up a delicate cambric handkerchief, which he hastily thrust into his pocket.

"I'll examine it later," he said to his friend. "Now for the vault."

"B-r-r! are you going in?"

"Yes."

"But the thing is locked."

"Perhaps not."

"It is—see!" and he gave the door a violent shake.

"Wait," said Cheever; "I will open it."

"How?"

"With a key."

"Hold on a minute. This thing has gone far enough."

"What has?"

"I'm not going to be a party to breaking open that vault. Why, if anybody saw us, we'd be taken for ghouls ourselves."

"Without doubt."

"Well, I don't fancy the job."

"Neither do I; but it is necessary."

"Bosh!"

"Hold the light for me while I open the door."

"Not much! I'm—"

The young man called Cheever, interrupted his companion by seizing him by the wrists, and forcing him to his knees as easily as though he were a child.

"Listen to me, Frank Tappen," he said, sternly. "I'm going into that vault and you are going with me. This is not the first time that you have been in a cemetery at night, and unless—"

"My God! what do you mean?"

"Just what I say."

Tappen's face grew as white as a sheet. His teeth chattered, and he wore, for an instant, the aspect of one who was mortally afraid.

"I swear—" he began, but the sharp voice of the other interrupted him.

"Don't swear," he said, tersely, "for I already know all that you would swear to."

"Are you a detective?" gasped Tappen.

"Perhaps I am."

"Then—"

"Will you hold the light and do as I tell you?"

"Yes,"

"Then get up."

Tappen obeyed. He took the light in his trembling hand, holding it so that the gleam fell upon the lock of the vault door.

Cheever was but a moment in overcoming that trifling obstacle.

The great mass of iron bars swung slowly in, moving as silently as a ghost.

"Ah murmured Cheever; "I thought so."

"Thought what?" asked Tappen.

The young man who had insisted upon thoroughly investigating the cemetery robbery, turned quickly upon his companion.

"Who unlocked this door, when the body of Miss Lawrence was placed here?" he asked.

"The sexton."

"Who stood near him when he did it?"

"There were several."

"Exactly. Weren't you one?"

"Yes."

"I thought so. Did you notice anything peculiar about the door, then?"

"Nothing, only—"

"Only what?"

"It squeaked horribly."

"Exactly. Did you hear it just now?"

"No."

"Neither did I."

"What has made the difference?"

"Somebody has oiled the hinges."

"Ah!"

"Which proves that the people who just left by the front gate were at this vault."

"You think so?"

"I know it."

"Why would they come here?"

"For the body of Dora Lawrence."

"For what purpose?"

"For what purpose are bodies usually stolen?"

"For the dissecting-room. Oh, Heaven! can they have taken her to—"

"You should know, Frank Tappen."

"I!"

"Yes, you!"

"But—"

"Wait. Let us proceed with our investigations. When we have finished, I will explain, and so shall you. Come!"

"What are you going to do now?"

"Now?"

"Yes."

"I am going to examine the coffin in which the body of Dora Lawrence was once placed."

"Oh, no—no—no!!!"

"And I say yes!"

"It is horrible!"

"Perhaps."

"If we are seen, we will be arrested as body-snatchers."

"Yes."

"That would be terrible."

"For you, yes; but not for me."

"Cheever, I demand to know what you mean?"

"I will tell you by and by."

"Tell me now."

Tappen spoke in a low, constrained voice, full of intensity, full of anguish, full of defiance and determination.

As he spoke, he drew a revolver and pointed it straight at his companion's heart.

"Tell me now," he repeated. "I am not a baby to be forced to your will, whether or no. Tell me what you mean, or by heaven, the coffin that held the body of Dora Lawrence shall not be empty long."

THE young man called Cheever did not move, when he saw the pistol aimed at his heart.

Indeed, he smiled coldly, as if he felt no real fear of the weapon that was pointed at him.

"Why do you say that?" he asked.

"Because I mean it," returned Tappen, still keeping his pistol poised.

"Ah! then you know that the coffin is now empty?"

Tappen recoiled, and grew even paler than before.

It was a weird scene, indeed.

Two young men alone in a cemetery vault; Tappen, with the bull's-eye lantern in one hand, and a revolver in the other, and with both aimed full at his companion.

The last words of Cheever seemed to madden him beyond endurance.

"You are a devil!" he hissed; "and I will kill you."

"Tell me how you know that the coffin is now empty," repeated the other, coldly and imperturbably.

"I do not know it."

"Then why—"

"I suspect it."

"Ah!"

"You have made several insinuations which you must explain."

"Certainly."

"Or, I will kill you."

"And place my body in the empty coffin."

"Yes."

"You insist that it is empty?"

"No."

"Suppose it is not."

"Well?"

"Where, then, would you hide my body?"

"Bah! you trifle. I will give you one minute to explain. If you do not do so I will fire, just as sure as we are alone in this vault, far out of the way of interference."

"You would murder me?"

"Yes."

"And leave my body here?"

"Yes."

"Thinking that you would never be known as my murderer?"

"Yes."

"You are mistaken."

"Bah!"

"Listen to me, Frank Tappen."

"Speak quickly."

"I will do so. Do you know where you stand?"

"Yes."

"Do you know that a warrant is already out for your arrest?"

"No—no."

"It is true. Do you also know that we were known to be together to-night? Do you know that suspicion points to you as the murderer of Dora Lawrence? Do you know that if you pull that trigger it will bring three men to the vault, who have followed us, and who only await a signal from me to enter and seize you, and bear you away to jail a prisoner? Do you know that, although you stand there with a deadly weapon pointed at my heart, you are as much in my power as I appear to be in yours? Put that pistol in your pocket, and listen to me, and I will tell you what I know."

"I will not."

"Put it in your pocket, I say. If you should be seen with it in your hand, the suspicion which hovers over you now would be strengthened. You dare not use it; therefore hide it."

The cool manner in which Cheever spoke, impressed Tappen.

He glanced furtively around him, so that had Cheever chosen to do so, he could have leaped upon and disarmed him with little trouble.

But such was not his purpose.

He saw that the young man was already morally conquered and he waited.

"Put away the weapon," he said, again.

Tappen obeyed.

"That is right," said Cheever. "Now listen. Do you know that Dora Lawrence is dead?"

"Yes."

"Do you know what killed her?"

"Yes."

"What?"

"Heart failure."

"Ay, but what caused that?"

"Who can say?"

"I can."

"You?"

"Yes."

"What, then?"

"Poison."

"Poison!!"

As Tappen uttered the exclamation, he started as though a bee had stung him.

"Yes, poison," repeated Cheever, coldly.

By a violent effort Tappen regained his composure.

"Who administered it?" he asked in a low tone, but he was in no wise prepared for the answer that he received. It came in four words:

"Her husband is suspected."

Frank Tappen started back, and his hand again sought the pocket where he had placed the revolver.

"Don't draw," said Cheever, sternly, "for I am prepared for you this time."

He was. His right hand held a weapon, and the muzzle menaced the young man, who, a moment before, had been so defiant.

Cheever stepped forward, and extending his other hand, said, coldly:

"Give me your pistol."

Tappen obeyed.

"That is better. We can talk now without more theatricals. Were you surprised to learn that Dora's husband is suspected?"

"She was not married."

"Do you say that? You?"

"Yes, I!"

"Tappen, are you, indeed, a thoroughgoing scoundrel? Have you no sense of shame left in you? Did the fortune to which you have lately fallen heir destroy all your manhood?"

"What do you mean?"

"Don't you know what I mean?"

"No."

"Frank Tappen, you lie!"

Tappen took one quick step toward his companion.

"By Heaven, Cheever!" he exclaimed, whiter than ever, with passion and fright, "it is well that you took away my pistol before you said that. But I warn you—"

"Well?"

"If you repeat it, I will kill you, or you will kill me."

"But not as you killed your wife, eh?"

"Oh, my God!"

The exclamation burst from Tappen's lips in a wail of anguish.

He covered his face with his hands, and sank backward upon a rough settee, moaning like one in pain.

Cheever regarded him silently, an expression of mingled scorn and pity upon his finely chiseled features.

He said nothing, and presently Tappan spoke again,

"Who are you?" he moaned.

"One who knows all," returned Cheever.

"All?"

"Ay, nearly all. Enough to—"

"To what!" and Tappen leaped impetuously to his feet.

"Enough to convict you of the crime of murder," was the slowly enunciated reply.

Again the young man sank upon the settee.

There was a full minute of absolute silence, and then Cheever spoke again, slowly and emphatically:

"I know that a little more than a year ago you were secretly married to Dora Lawrence; I know that about four months ago a child was born of that union; I know that the marriage and the subsequent birth were kept profound secrets; I know that six months ago, your uncle, in Liverpool, died and left you a large fortune; I know that certain severe restrictions were in the way of your accepting the money left to you; I know that the fact of your marriage, had it become known, would have kept you out of the wealth which you are now enjoying, and of which you have made very poor use; I know that from the moment of your uncle's death, you cursed the hour when you had married Dora Lawrence; I know that had there been any safe means of getting rid of your wife and expected child, you would not have hesitated to employ them; I know—"

"Stop! Stop! For Heaven's sake, stop!"

"Well?"

"Man, boy, or devil, who are you?"

"Don't you begin to suspect?"

"You are a detective?"

"Yes."

"You were sent here to arrest me?"

"Yes."

"For murder?"

"Yes."

"You have woven around me a chain of evidence from which I cannot escape?"

"Yes."

"You could prove me guilty?"

"By circumstantial evidence, yes."

"Oh, Heaven! Then why, why did you bring me here?"

"Because the body of Dora Lawrence has been stolen."

"Stolen! and do you think that I—"

"Wait. If Dora died from the effects of poison, and her body should be taken from the vault for a post-mortem examination, traces of the poison would be found."

"Yes—yes."

"But if, when they come here for the body, it should have disappeared, where would be the proof that poison had been administered?"

"Ah!"

"The proof would have disappeared with the body?"

"Yes."

"And the person who was guilty of the crime would be the one who would have had the most reason for causing the body to disappear."

"Do you believe that I—"

"Wait, Tappen. I know more."

"Speak, man, for I believe that I am going mad."

"I know that before you inherited your fortune, you were a medical student; I know that you were a member of a private clinic, which met near this village once a week; I know that the principal features of that clinic were anatomy poisons; I know that in the anatomical studies many bodies were secretly and illegally procured for your instructor's dissecting-room; I know that you take part in many expeditions to grave-yards, and I know—"

But Tappen could hear no more.

With aloud cry he fell headlong to the floor of the vault in a dead faint.

But as the detective bent over him, he murmured:

"And I know enough to believe that you are innocent of the crime of murder."

TAPPEN did not remain long in a faint. He presently opened his eyes, and looked up into the face of the young man who bent over him, and whom he knew as Cheever.

"Who are you?" he murmured.

"Did you ever hear of Nick Carter?"

"Yes. Are you Nick Carter?"

"Perhaps I am."

He was not Nick, however, but Chick; the faithful assistant of the great detective.

The remarkable case of the supposed murder of Dora Lawrence had been taken to the Little Giant during his absence from the city, and Chick, who personated him upon all such occasions, had speedily recognized the fact that unnecessary delay should be avoided.

Leaving a note of explanation for his chief, therefore, he had started out at once, and gone to the little village in New Jersey where the crime was supposed to have been committed.

He had been there four days at the time of the opening of our story, and during that period, he had become the boon companion of Frank Tappen. The object that he had in thus associating himself with the person suspected of the crime, can be readily seen.

Link by link he had put together the scraps of evidence that he had gleaned during those four days, and with the result that we have already seen.

Many of the statements that he made to Tappen during their conversation in the burial vault, were based on conjecture only, but that they had one and all hit the mark, he saw the instant that they were uttered.

It cannot be denied that there were other and graver reasons in his mind, for his suspicions regarding Frank Tappen, but they do not yet appear.

Chick soon assisted Tappen to his feet.

"Come now," he said, somewhat coldly, "we must finish this business."

"What would you do?"

"Examine the coffin."

"Why? You believe it to be empty?"

"Yes, and you know it to be."

"I do not, so help me God."

"Have you the courage to look into it?"

"Yes."

"Even though the dead face of your murdered wife may still be there?"

"Yes, even so."

Chick suddenly stepped forward, and, seizing Tappen by both arms, said, sternly:

"Frank Tappen, did you kill your wife? Answer me; are you her murderer?"

For an instant there was a dead silence in the vault, while Chick waited for the young man to reply.

At last the words came slowly, and with evident hesitation.

"As I hope for forgiveness hereafter, I do not believe that I did."

It was a strange answer, and yet evidently it, or one very much like it, had been expected by Chick.

"Tappen," he said, "you have much for which you must answer. I believe you intended to murder Dora, for I know that you had planned to be rid of her, but of the act itself I believe you to be innocent. Help me with this coffin."

"Must we move it?"

"Yes."

It was soon placed upon the floor between them, and then Chick, with deft hands, removed the screws from the lid.

"Raise the lid and look in," he said.

"Oh, no; I cannot. She is in there. The coffin is not empty."

"Raise the lid," repeated Chick, sternly.

"I cannot."

"You must."

With trembling hands the young man obeyed.

He raised the coffin-lid and drew it aside.

Then, with a loud exclamation of dismay, he started back, nearly falling to the floor again.

"It is not Dora," he cried. "It is—"

Then he paused suddenly, looking up at the young detective with a startled glance of apprehension.

"Who?" demanded Chick, quietly.

"Ay, whose face is it?" said Tappen, trembling, and making an effort to replace the lid.

But Chick motioned to him to wait.

"Whose face is that?" he asked, sternly, throwing the light of the bull's-eye, which he had taken when Tappen fainted, full upon the face of the corpse in the coffin.

"I—I do not—know."

"You lie, Frank Tappen."

"How should I know whose face it is? I never saw it before. I—"

"Stop, or, by Heaven, I will give you up, to-night, for murder, and hang you for it, too. Whose face is that? What girl have the fiends, who stole Dora's body, placed here in lieu of her? Tell me."

But Tappen's strength was gone.

As he stood gazing at the beautiful blonde head in the coffin, his eyes seemed to start from their sockets in horror. His face blanched until it resembled chalk. His body swayed like a reed in a strong wind.

Suddenly, he began to chatter incoherently.

Meaningless phrases fell from his lips. Sentences which had naught to do with the time or circumstance.

Then he turned to Chick, and, with a vacant smile upon his face, he whispered:

"Is she dead? Is Cora dead? Cora and Dora. Cora is a blonde; Dora is a brunette. All right, doctor, I hear you. Yes, yes; I'll be careful. Ah, Cora, it is too bad to treat you so, but—"

He paused, and then there issued from his lips a scream such as one who is suffering untold anguish and mortal terror, can utter.

Then he paused, and, crouching upon the floor, he muttered in an intense whisper:

"My God! what have I done! I—am—a—murderer!—twice—a—no—no!!"

Then, as though completely overcome, he again sank to the floor in a swoon.

For a moment, Chick was nonplused.

He drew near to the insensible form of Tappen, and bent over him.

"I tried him too far," he murmured. "The strain was greater than he could bear. Wild, reckless, heedless, and bad as you are, Frank Tappen, I believe that you are more sinned against than sinning, for even though in your moment of madness, you proclaimed yourself a murderer, I do not believe you are one."

He left Tappen, and leaned over the beautiful face in the coffin.

Then, with careful, reverent hands, but with the determination to be thorough for the sake of the justice that he could do in the future, he lifted the body from its resting-place.

Twenty minutes later he returned it to the coffin, screwed down the lid, and then, alone and unaided, replaced the casket in its niche in the wall.

Tappen had regained consciousness, but had not sought to rise from his position on the floor.

Chick approached him.

"Get up, Frank," he said. "You must go with me now."

"Is that you, Cheever?" asked Tappen.

"Yes. Get up."

"I cannot."

"Why?"

"Don't you know that I am dead?"

"Oh, yes," replied Chick, humoring him; "but ghosts can walk. You are Tappen's ghost, aren't you?"

"Yes, that's it. Tappen's ghost."

"Well, come with me."

"Where to?"

"Never mind; I will show you. Come."

"No, I cannot."

"Why?"

"I dare not."

"Dare not?"

"No. People will see me. You know I have got murderer written upon my forehead, and they will know that I killed—I killed—I say, Cheever, who was it that I killed, Cora or Dora?"

"Both, wasn't it?"

"No, oh, no! I am quite sure it was only one; which one was it, Cheever?"

"Perhaps it was Cora. Tell me her last name, and maybe I can say."

"Don't you know her last name?"

"No."

Tappen laughed aloud.

"Wouldn't I be a fool to tell?" He cried.

"Why?"

"Because you would hang me."

"I couldn't hang a ghost, could I?"

"I am not sure. Am I a ghost?"

"Certainly. Tappen's ghost."

"Then people can't see me, can they?"

"No."

"Nor read that word on my forehead?"

"No."

"Are you sure?"

"Perfectly."

"Aren't you afraid of ghosts?"

"Not a bit."

"That's strange; I am, although I am a ghost myself. That's odd, isn't it?"

"Very."

"Say, Cheever."

"What?"

"I saw a ghost to-night."

"Did you? Whose?"

"Cora's."

"Cora who?"

"Don't you wish you knew?"

"Yes."

"Ho-ho! I'll never tell you, never!"

"Come, now, we must go."

"Must I go?"

"Yes."

"All right."

Chick took the demented man by the arm, and led him from the vault.

He carefully locked the iron door, and then, still leading Tappen, hurried away through the darkness, having closed the mask of his lantern in order to avoid chance observation.

Leaving the cemetery, he made straight for the railroad station, where he knew that a train was soon due, that would take him to New York.

Two hours later, he entered the house of Nick Carter, still leading Tappen by the arm.

*

When he left the vault and walked away with his companion, a shadow-like figure glided from among the bushes near by, and at a safe distance noiselessly followed.

She—for the figure belonged to a woman—continued the chase far enough to be satisfied regarding the destination of the detective. Then, pausing abruptly, she stood for a moment as if lost in thought.

Suddenly she turned and retraced her steps to the cemetery, again entering by the front gate, which stood wide open.

Instead of following the path, she glided along the wall for several rods. For a moment she disappeared in the shadow of a dense grove, but suddenly reappeared, mounted upon a coal-black horse.

Then she rode swiftly to the gate, and in another moment dashed away at a rapid pace in the same direction taken by the carriage.

THE circumstances surrounding the death of Dora Lawrence had been very peculiar, and a few words in explanation of the event and the conditions surrounding it, are necessary here.

She was buried, or rather the body was consigned to the family vault, on her twenty-first birthday, and just four days after she breathed her last.

Fatherless and motherless, the only surviving member of a once large and wealthy family, she had, for two years, resided in the old homestead with a maiden aunt, a half-sister of her mother.

She was by no means an heiress, for the wealth that her parents had formerly enjoyed had vanished at the time of her father's death, leaving barely enough to support her and the aunt, who was supposed to care for her from that time on.

But the aunt thought little about her niece. Her mind was given up to graver matters. She was engaged in the occupation of saving her soul, and had no time to devote to the welfare of her youthful charge.

The consequence was that Dora did as she pleased.

Nevertheless, she was as good as she was beautiful, and when Frank Tappen proposed a secret marriage to her, she indignantly refused.

But he did not give up.

At every opportunity, he renewed his arguments, until ultimately she consented, and the marriage was consummated.

Then all went smoothly for a time, until Dora realized that she must either absent herself from home for an indefinite time, or betray the secret which she had promised Frank to keep inviolate until—well, until he gave her permission to reveal it.

Tappen was, at that time, a student of medicine in one of the New York colleges; but he also belonged to a private and extremely select clinic, which had been organized by a choice few who had secured for their instructor a very aged and very learned physician of the village where Dora lived, and who was known there as Dr. Agate.

Very little was known regarding the aged doctor, except that he had on several occasions proved himself to be remarkably skillful—and it was whispered remarkably unprincipled as well.

At all events, the clinic, of which he was the instructor, and Tappen was a member, had been formed.

Dora, acting upon the instructions of her young husband, easily secured permission from her aunt to pay a protracted visit to imaginary friends in Albany, and so departed.

But that same night she secretly returned to her native village and was received in the house of Dr. Agate, where she remained until her child was born, and she was strong enough to return to her home.

In the meantime, Tappen had fallen heir to a large fortune, which was, however, so restricted that should his marriage become known, he would lose it all.

About four months after the return of Dora to her home, she was taken violently ill, and Dr. Agate was called in to attend her.

He came, but for once his skill seemed to be of no avail, until one evening, after making his usual call, he told a neighbor who inquired of him as he was leaving, that Dora was better, and he believed that she would recover.

That same night she died.

Frank Tappen was seen hovering about the house where his wife was sick, at midnight, the night she died.

He was seen to enter the grounds and to stand beneath her window for along time. Finally he was seen to enter the house by the back door, and twenty minutes later he reappeared.

Dora's death was known to have occurred after the clandestine visit of the husband. Her aunt had administered her medicine at midnight, and had, soon after, dropped into a slumber, from which she did not wake until two. She had then gone to the bed to administer another dose, and had discovered that her niece was dead.

Dr. Agate was at once called, but had averred that he could do nothing.

He pronounced the death heart failure, resulting from the malady from which she was suffering. The certificate was made out, no questions were asked, and Dora, after being kept four days, because her aunt had a horror of anybody being buried alive, was consigned to the family vault.

But there was in the village a young man who had deeply loved Dora Lawrence. For months he had watched developments, and it was he who had gone to engage Nick Carter to work upon the case, believing that a crime of some kind had been committed.

Months before, when Dora was supposed to be in Albany, John Burlington had, by the merest chance, learned that she was an inmate of Dr. Agate's house. From that moment he had watched with close attention, but with little result.

Such was the story that Chick learned, partly from John Burlington, but chiefly through his own efforts, and such were the facts as he related them to Nick Carter about noon, on the day following the adventure in the vault, adding all that has been already told in these chapters.

They were sitting together in the room that Nick called his study.

"You have done very well, Chick," he said, when his assistant had finished; "as well in every respect as I could have done; but there is much to do yet."

"Lots."

"What is it that you are keeping back from me?"

"Eh?"

"You heard my question."

"You must be a mind-reader, Nick."

"I am. Speak out."

"I am not exactly keeping anything back, but—"

"Well, but what?"

"I have a strong suspicion."

"Ah! what is it? That Tappen is not so crazy as he would have us think?"

"Yes, that is one."

"And I agree with you; but we will touch upon that subject later. What is the other?"

"I think I have found Dr. Quartz."

Nick bounded from his chair, and seized Chick's hand.

"Good!" he said. "That means ten thousand in your pocket, boy."

"Bah! I was not thinking of that."

"Of what, then?"

"Wait; I will get to it. I want to ask a few questions."

"Fire away."

"When did Quartz make his second escape from prison?"

"About ten months ago."

"Hum! Let me recall the circumstance. Soon after his capture he was taken violently ill?"

"Yes."

"And died?"

"Yes."

"And the body was given to his friends?"

"Exactly."

"Just as he was about to be buried, the chief received a telegram from you, advising him to look at the body, the last thing before it was lowered into the grave. He followed your advice, and found that the coffin contained a wax figure, weighted, and so perfectly made as to almost defy detection."

"Right, Chick."

"Then they wondered what had become of the slippery doctor, and, up to date, no trace of him has been found."

"Precisely; go on."

"That's all."

"Oh, no. You forget that two thousand dollars reward was offered for satisfactory proof of his death, and ten thousand for his capture, if alive."

"No, I don't. Well, I believe he is alive, and that I have found him."

"Where?"

"In this case."

"What! Do you mean Dr. Agate?"

"Yes."

Nick indulged in a long whistle.

"Why do you think so, Chick?"

"Well, chiefly because I do. That is about the only reason that I can give."

"It will do for the present. To-morrow we will look into the question a little more deeply."

"We will."

"Now, Chick, how did you happen to be on that corner, near the cemetery, when you heard the cries for help?"

"I had walked part way home with Tappen, and intended to visit the vault and investigate things when I left him."

"So if you had been a little earlier, you would have caught the body-snatchers in the act?"

"Yes."

"Can you account for the screams?"

"I wish I could."

"So do I."

"There is only one explanation."

"And we both know what that is."

"Yes."

"Have you any clew whatever regarding the identity of the body you found in the casket where Dora's should have been?"

"None, except that her name was Cora, and that she has been upon a dissecting-table."

"You are sure of that?"

"I ain positive."

"The clinic meets to-morrow night."

"Yes."

"We will be there, Chick, for further instructions. Well, Peter, what is it?"

"A gentleman to see you, sir."

"All right. I'll be there presently."

While Nick was adjusting his dress to suit the occasion, Chick went to the peep-hole.

When he again faced his chief there was a broad grin upon his face.

"You've got another case," he said.

"Ah!" replied Nick.

"Yes. This time it is a mysterious disappearance. The man waiting for you is the step-father of Frank Tappen, and he wants you to find the lost millionaire."

"Good!" said Nick; "I'll take his case."

They both laughed, and Nick went to interview his caller.

Chick's conjecture proved to be true.

The step-father of Frank Tappen had called to engage the great detective to find his wayward son, notwithstanding the fact that the young man had not been missing twenty-four hours.

IT was just dusk on the following evening when a curious-looking old countryman, accompanied by a gawky youth with carroty hair, rang the bell of the old house where Dr. Agate lived.

"Well, I'll be gosh-darned!" ejaculated the elder man, after he had waited several moments without receiving a reply to his summons.

"What's the matter, Dad?" asked the other one.

"Sposen yewer mother Mirandy wuz jest arter havin' a shock! How in thunder dew yew s'pose a feller'd git a doctor fur her, hey?"

"Have patience, Dad."

"Wal, I shouldn't think the doc would have any ef he keeps 'em all a-waitin'— Hello! Say, Bill, somebody's comin'."

The door opened and a middle-aged woman, with uncommonly piercing eyes for one of her years, stood before them.

"Wanter see the doc," said the elder man, shortly.

"Walk in."

"Thankee. Say, jest tell him that Sile Griffith's called, will ye? Hello, be you the doc?" as they were ushered into a little room off the hall, in which, before a desk that was literally strewn' with bottles, empty and full, an aged man was seated.

"Yes. What can I do for you?"

"This is my boy, Bill."

"Indeed."

"Yes, and he wants ter be a doctor."

"Ah!"

"I've tried to convince him that he's a tarnation fool fur havin' any such idea, an' I've jest brung him to you to settle the biz."

"My dear sir—"

"Wait, doc; I ain't got much to say, and when I'm done, yew begin. Say, ef yew'll take that boy an' set him tew study in' medicines, an' pizins, an' cuttin', I'll pay the bill. Now, ef yew've got anything ter say, hoop er up."

"I have very little to say."

"Say it."

"I cannot take your son."

"Can't!"

"No."

"Why not?"

"There are many reasons. It is enough that I cannot."

"Won't, eh?"

"No, if you put it that way."

"Blowed ef yew will, eh?"

'Exactly, blowed if I will."

The farmer turned to his son with triumph in his face.

"There, Bill, what did yer ole dad tell ye, hey?"

"I ain't done yet, Dad."

"Ain't, hey?"

"No."

"What ir ye goin' ter dew now?"

"Try t'other feller."

"Wot! over to the ole Morgan place?"

If the farmer had glanced from the corner of his eye, he would have seen the aged doctor give an almost imperceptible start when he asked the last question.

"Yep," replied Bill.

"But ye don't even know who the feller is."

"I know wot he does."

"Tut—tut, Bill; ye mus'n't tell all yew know."

"I'll tell that, ef he don't let me in."

"Of what are you speaking, my young friend?" asked the doctor, blandly.

"There, Bill, shet up now!" exclaimed the farmer.

"I won't, Dad—that is, unless I kin git the feller to take me in."

"In where?" asked the doctor.

"To the Morgan place."

"Ah! where is that?"

"Over here a piece."

"Why do you want to be taken in there?"

"Cos I do."

"Ah! what have you seen there?"

"Who said I'd seen anything?"

"I'm sure I don't know; have you?"

"I've seen enough."

"Enough for what?"

"To make him take me in. I'm bound tew study for a doctor, I am."

"How much will your father pay to have you instructed?"

"Oh, I'll pay the bill!"

"But you will have to go to college to become a physician."

"Guess I know that."

"I'll tell you what I will do, William."

"What's that?"

"I'll take you to study with me for a week, on trial. If you like it, and I like you, you may remain longer. How does that suit you?"

"Bully."

"Very well; when do you wish to begin?"

"Now."

"But this is rather sudden."

"Look here, doc; me an' Dad's had a row. He walloped me fur it, too, an' I ain't a-goin' hum ag'in till I'm a doctor, yew hear me? I'll take care of yer hoss an' do the chores for a place to sleep an' suthin' ter eat, an' Dad'll pay fur my schoolin', an' I'll begin now, 'r try t'other place."

"Very well. You may begin now, if that's the case."

"What's the bill, doc?" asked the farmer. "I'll pay for one week now."

"Ten dollars."

"What!"

"Ten dollars."

"Whew! It'll cost suthin' tew make a doctor of Bill, won't it. Wall, here yew be. Now, Bill, I'm goin' back tew yew'er mother, Mirandy, an' don't yew go tew makin' a fule of yerself, tellin' 'bout that Morgan place. Good-evenin', doc."

The farmer walked out, untied an old horse from the hitching-post, and drove slowly away toward the country.

But there was a smile lurking in his keen eyes.

He was no other than the detective, Nick Carter, in his favorite disguise as a farmer from "up-country," and he had just seen and heard that which pleased him greatly.

"We've got him, sure enough," he thought, "for if Dr. Quartz wasn't the fellow under that snow-white wig and beard, then it was his ghost. Well, I did think him too smart to swallow a bait whole like that, though."

Events proved, however, that Nick congratulated himself a little too soon.

The doctor had not taken the bait as freely as he appeared to.

Those of our readers who knew Dr. Quartz in the previous numbers of the library, which relates the experiences of Nick Carter, know that he was in many respects a wonderful man.

As powerful as a veritable giant; stronger even than the great detective himself; as keen as a razor; as quick as a flash; thoroughly educated; noted for his skill as a physician; as perfect an adept at disguises as Nick Carter; a scholar, and a man utterly without conscience or heart, he was one to whom even the keenest of all detectives—for Nick Carter had no peer—was forced to accord the old saying:

"This is a foeman worthy of my steel."

Twice had Nick been pitted against him, and twice had the wily doctor been placed behind prison bars by the Little Giant.

Both times he had made his escape from prison, and now the third trial of shrewdness and cunning was inaugurated.

"Three times and out," muttered Nick, as the old horse jogged mournfully along. "I guess Chick will be enough for him at that end, so I'll work this one."

But the doctor was not so greatly taken in as he seemed to be.

Nick Carter had no sooner left the house than he motioned to Chick to come nearer.

"What do you know about the Morgan place, William?" he asked.

"Nothin'."

"Tell me the truth."

"I ain't goin' to tell nothin'."

"Ah!" and that odd smile, which somehow the doctor always had ready, played upon his face.

"You have seen strange doings there, haven't you?"

Chick nodded.

"Dead bodies, and so forth, eh?"

Again Chick nodded.

"Do you know who has cHarge of the place?"

Chick shook his head.

"I have."

Chick was rather surprised.

"You are determined to study medicine?" continued the doctor.

"Yessir."

"Very well. You may begin to-night. I will take you to the house with me, and you shall see what it means to become a doctor."

"Yessir."

Chick saw no more of the woman who had opened the door to admit him, until at ten o'clock the doctor woke him from a feigned sleep, and said that he was ready to start.

The Morgan place was an old house of the Colonial style, and stood a mile from the village, beyond the cemetery.

It was reputed to be unoccupied, and thought by many to be haunted, for strange sights and sounds had been seen and heard there by belated pedestrians.

When Chick reached the carriage, which was to take them to the Morgan place, he was about to step in when he heard a voice from the shrubbery call:

"William!"

He paused and looked hastily around.

"William!" repeated the voice.

"That's a woman's voice," thought Chick, and he said:

"Hello! Wot's wanted?"

A dark figure glided from the shadow, and, seizing him by the arm, drew him away into the denser darkness.

"The doctor is coming, and I haven't a minute," she said.

"That's so," responded Chick.

"You must not go to the Morgan place to-night, young man."

"Why not?"

"Because, if you do, you will never leave it alive!"

"Git out!"

"The doctor is a villain."

"Mebby he is, ole girl, an' ag'in, mebby he ain't."

"Listen to me."

"I am listening."

"He means to murder you."

"To murder me!"

"Yes."

"How do you know?"

"I know, because he has done it before."

"You're mistaken; he never murdered me before. I—"

"Oh, listen to reason."

"You bet!"

"Do you know what that house is?"

"Yes—the Morgan place."

"It is a charnel house."

"A what!"

"A house of death."

"Oh!"

"Once a week they meet there."

"Who meets there?"

"The doctor and his pupils; but do you know what for?"

"No."

"Shall I tell you?"

"Yes."

"They meet there to dissect human bodies. When they are without a subject for their table, they make one with the knife. They have no subject to-night, and they mean to murder you and place you upon their dissecting-table."

CHICK did not know exactly what to think when the strange woman gave him this warning.

He did not know whether to believe that she was in earnest, in endeavoring to save him from a terrible fate, or whether her warning was only a part of a deeper scheme against him.

"Do you mean that when they kin git a body in no other way, they murder somebody?" he asked.

"Yes."

"Have they ever done that?"

"Often."

"Often?"

"Yes, a dozen or more times."

"And they mean to murder me?"

"Yes, they do."

"They dassent."

"Why not?"

"My ole dad'1l be lookin' fur me."

"They will murder him, too."

"Not much, they won't!"

"Hush! there comes the doctor. Run while you have time."

"No, I'm goin' ter stick."

"Do you insist upon going?"

"Yes."

"To be murdered?"

"Yes."

"And cut to pieces and fed to dogs like carrion??

"Say, lookahere, ole girl, my dad has tried to skeer me outen this here notion o' mine, an' ef he couldn't, by gosh yew can't, an' don't yew think yew kin!"

Then Chick turned and climbed into the carriage, just as the doctor reached it, his case of instruments in his hand.

The drive to the Morgan place was accomplished in silence.

Chick was busy thinking of what the mysterious woman had said—wondering to what deep plot her words might lead.

Suddenly the carriage stopped.

"We get out here," said the doctor.

"We ain't to the Morgan place yet."

"No, it's a half-mile farther."

"What a'ye git out here fur, then?"

"Because we must not be seen going to the house. It isn't too late for you to back out now, if you care to."

"No, I'm goin' ter see it through."

The horse was driven among some trees and tied, and then the strange pair continued their journey on foot.

The house was soon reached.

It was dark and silent. Not a sign of life could be discerned about it.

The doctor led the way to the back door, and, making use of a little key that he carried on his watch-chain, opened it and entered.

Chick followed, having no suspicion of impending danger at the moment.

He had forgotten that he was dealing with a man as shrewd as himself, and as unprincipled as he was keen.

They passed through the door into total darkness, for the doctor quickly closed the entrance after them.

"Where are you, William?" he said, in that strange, soft voice of his.

"Here."

"Give me your hand."

"Why in blazes don't yew strike a light?"

"Presently, William, presently. Give me your hand, and I will lead you to the light."

Chick extended his hand, and the doctor grasped it.

"Come," he said.

Then they walked a dozen paces or more through darkness, so dense that absolutely nothing could be seen.

Suddenly the doctor paused.

"Stand where you are, William, until I open the door," he said.

"Right," replied Chick.

The doctor dropped his hand, and moved swiftly away.

So did Chick.

He did not relish the manner in which he was being introduced into the house, and there was a tone in the wily doctor's voice, when he told him to stand where he was, which warned him not to do so.

His hand was no sooner released than he stepped three paces backward, in the direction from which he had come.

He moved quickly and silently, and yet he was not an instant too soon.

There was a sharp click from the floor directly in front of him, and instinctively he knew that he had been standing upon a trap-door, which had suddenly fallen open.

Had he not moved, he would have been precipitated into the unknown abyss.

Simultaneously with the click there came a flash of light, and the brilliant ray of a bull's-eye lantern was thrown squarely into his face.

It was the doctor who held the lantern, and he laughed softly when he saw that his companion had not fallen into the trap.

"You were too quick for me," he said, coolly, as though referring to a harmless joke.

"Yes," said Chick, just as coolly, "and, if you move an inch, I'll be too quick for you again. I know you, Dr. Quartz, and I have you covered through my pocket, with one of my little guns."

"Indeed! So you know me, eh?"

"Yes."

"Well, the recognition is mutual. Did you and Nick Carter think that you could impose upon me with such a simple trick as the one you tried to-night?"

"Well, we didn't, it seems."

"Not quite—no."

"Quartz," said Chick, sternly, "I am awfully sorry that you sprung that trap-door when you did."

"Indeed! Why so?"

"Because it compels us both to unmask too soon."

"Exactly."

"And I am obliged to put the shackles on you too early in the game."

"Very unfortunate," ironically.

"Very—for you."

"So you're going to arrest me?"

"Yes. "

"When?"

"Now."

Again the doctor laughed, softly.

"Do you think that I will wait here calmly for you to put the bracelets on my wrists?"

"You will have to."

"Why?"

"Because, if you move, I will kill you as I would a dog."

"You will, eh?"

"Yes, I will."

"Very well, I won't move."

"That's right."

"Neither will you take me."

"We will see about that."

Chick took one step forward, but only one.

As he did so, there was a loud report from behind where he stood.

The brave youth uttered a loud groan. Then he reeled, and the next instant fell headlong to the floor, close to the open trap.

For a second his body clung to the edges of the opening, and then, as the young detective made one spasmodic effort to save himself, he lost his balance, and pitched forward through the square hole into the darkness below.

A loud splash and a smothered cry came up from the depths into which he had disappeared, and then all was still.

Again the doctor laughed.

He stepped forward, and threw the rays of his lantern into the abyss, just as the woman who had warned Chick not to go to the Morgan place, appeared upon the scene, revolver in hand, and with a fiendish glitter of hatred in her eyes.

"He's done for, Zel," murmured the doctor. "Did you shoot to kill?"

"Would I shoot for any other purpose?"

"No, my beauty, I don't think you would—and you never miss."

"Never. I would that the other one had stood by his side."

"With all my heart, my dear. Still I think it was foolish to shoot at all."

"Why?"

"Pistol-shots are noisy."

"Who would hear them in this place?"

"Anybody who might chance to be passing."

"Nobody passes here at this hour."

"Unless it be Nick Carter."

"Bah! I hope he heard it. He will think that we have killed his assistant, and he will force his way in here to meet with the same fate."

"Still, my dear, a shove would have done as well."

"A shot is surer."

"Well, Zel, shot or shove, alive or dead, nobody who gets into that hole, can ever get out alive. Come."

With his foot he closed the trap-door with a bang, and led the way into an adjoining room.

It was a strange apartment, and in it were half a dozen youths; young men, some of whom had not yet attained their majority, and others who were scarcely past it.

They were in a group at the far end of the room, while between them and the door by which the doctor entered, stood a table upon which something covered by a white sheet had been placed.

"What was the shot, doctor?" asked one of them, as the physician entered.

"We are getting short of subjects for our table. I was compelled to furnish one. A detective followed me; he is now in the pickle, clothes and all. Are you all here?"

"No. Tappen hasn't come."

"We will wait, then, for I particularly desire his presence."

"What have we for a subject to-night, doctor? You promised us a treat."

"You have not looked under the sheet?"

"No."

"Good! We will wait an hour for Tappen, and then—"

"Then what, doctor?"

"If he does not come, we will postpone our work until to-morrow night."

It was eleven o'clock when the doctor said that he would wait for Tappen. At twelve, he glanced at his watch, and then at the sheet which covered the table.

"Tappen is not coming," he said, "and I—"

"Hark!" exclaimed one of the students. "He is coming."

They all heard a door open and close, and the next moment a young man entered the room.

"Just in time, Tappen," they cried, in chorus. "The doctor was about to dismiss us because you were not here. Come! Get ready, for the doctor says he has a treat for us."

"Yes, a great treat," murmured the doctor, as Tappen and the others gathered around the table.

Then he motioned to the woman, who seemed to act as his assistant, to remove the sheet.

She obeyed, and there, arrayed as she had been in her coffin, was revealed the body of Dora Lawrence, as beautiful in death as in life.

THERE was a strange gleam in the eyes of Dr. Quartz—or Dr. Agate, as he was known by the students who surrounded him—when the woman, acting upon his instructions, drew the sheet from the face of the body upon the table.

He bent his glance fully upon the last arrival, Frank Tappen, and the tender smile which usually hovered about the corners of his mouth, had in it then something that was sinister and forbidding.

To the other students, the sight was merely that of a woman, young and beautiful, who was dead, and whose body they were to be permitted to mutilate when it should have been properly prepared for their use.

As it was, they uttered exclamations of disappointment, for they plainly saw that the doctor did not mean to use the knife that night.

A subject, fully dressed; laid out as it had been in its coffin, was hardly to their taste, and they were about to offer remonstrances, when the voice of Tappen interrupted them.

He said but one word, and yet it somehow chilled them all by its coldness.

He looked into the glittering eyes of the doctor, and said:

"Well?"

"Do you recognize the face?" asked the doctor, softly.

"Yes."

"Who is it, Tappen?" asked one of the students.

"An old schoolmate; a girl whom I once loved and wanted to marry," he said, coldly.

They looked at him in astonishment.

"Shall we proceed?" asked the doctor.

"Yes," he replied, in the same voice.

"You have no objections?"

"None."

For an instant the physician seemed puzzled.

Then, suddenly throwing the sheet back over the beautiful face, he demanded:

"Why were you late to-night?"

"I was detained."

"Where?"

"In the city."

"By whom?"

"By business."

"Where were you the night before last, at midnight?"

"In the cemetery."

"With whom?"

"With my friend, Cheever."

"Is his name Cheever?"

"No; he is a detective."

Again the doctor looked puzzled.

"Where did you go when you left the cemetery?" he asked, presently.

"To New York."

"Why?"

"To mislead the detective. Why do you ask these questions?"

"Because I believe that you have betrayed us all, and because, if you have, you shall be the next one to go upon that table where your schoolmate now lies."

"I did not betray you, but our secrets are known. We are not safe here, and you know it."

"You are crazy," said the doctor, speaking with strange. deliberation.

"No; I am not crazy. I have been, but I have recovered. I believe that I was followed to-night. I believe that if we remain here, we will be surrounded and arrested in an hour's time. However, I will, remain, if the others do."

But he had said enough to make them all only too anxious to go, and five minutes after he had spoken, all had departed except the doctor, the woman Zel, and himself.

"Why do you remain?" asked Quartz, coldly.

"Because I wish to ask you a question."

"Ah!"

"Why did you put Cora's body in the coffin that had been occupied by my—by her?" pointing toward the sheet.

The doctor chuckled.

"For you to find," he said, softly.

"How did you know that I would find it?"

"Bah! I knew it."

"Who screamed that night, when you drove away from the vault?"

"Zel."

"Why?"

"Because I choked her. I can be ugly upon occasion, Tappen, and being questioned does not improve my temper. Our little game is drawing to a close."

"Yes."

"You and I must have a settlement."

"When?"

"To-morrow. You have kept me waiting until you could convert the securities into cash. I have waited long enough, and to-morrow you must furnish the small fortune that you owe me, or—take the consequences."

'You mean this?"

"I do."

'You shall be paid to-morrow,"

"Ah!"

"On one condition."

"What is that?"

"That you take Zel and leave here now."

"Leave you here?"

"Yes—with her."

"Alone?"

"Yes."

"Why do you wish to be left here alone with the dead body of your wife?"

"It is enough that I do wish it. You will have to oblige me."

"Have to?"

"Yes."

"You use strong words."

"I mean them."

"How will you force me?"

"By telling you that you will lose the fortune you covet, if you refuse."

"Ah! You forget what such a refusal would cost you."

"No, I do not. Go. I wish to be left alone."

"What if the officers come?"

"They will not."

"Then you were not followed?"

"No,"

"Before I go, you must explain one thing."

"What?"

"Your madness in the vault."

"Does not the circumstance explain it?"

"Only partially."

"I can explain no further. I was taken off my guard. I got out of it the best way I could. Now go. It is one o'clock, and I must be alone."

"One more word, Tappen."

"Well?"

"Do you fear the detective who caused you to lose your reason the other night?"

"No, for if he persists in annoying me, I will kill him."

"As you killed your wife?"

"Perhaps."

"There will be no need."

"Why not?"

"Because he is dead already."

"Dead!"

Tappen started strangely, so that the doctor glanced keenly at him, as he said:

"You seem shocked."

"I am surprised. When did he die, and why?"

"To-night. He was afflicted with a combination of difficulties," and the doctor laughed, softly. "Cerebral concussion, asphyxiation, and general debility superinduced by Zel."

"She killed him?"

"Bah! no; he committed suicide. Well, you shall have your way. We will leave you here with your wife, and to-morrow, at 7.30 P. M., I will meet you—where?"

"Anywhere."

"Good! Here is a card. Come to that address, and ask for the queen."

"The queen!"

"Yes, Zel. She will conduct you to me."

"Is Zel a queen?"

"Ask her," and the doctor turned away and left the room.

The woman Zel lingered long enough to glance searchingly into Tappen's face.

"You are strange to-night," she said.

"Strange?"

"Yes."

"Why?"

"There is something in your manner,and—you forget me."

Tappen laughed coldly.

"Wait until to-morrow," he said, "when I call upon the queen, I will not forget you then, Zel."

She took one step to leave him, and then she paused.

"Do you let me go in this way?" she asked, reproachfully.

"Yes, to-night."

"Why to-night more than any other?"

He pointed silently toward the sheet.

The gesture seemed to infuriate the woman.

With a quick motion she drew a poniard from her bosom and leaped toward the table upon which the. body of Dora was laid.

But Tappen was before her.

He sprang between her and the object of her hatred, and, seizing her wrist, forced her back again.

"What would you do?" he exclaimed.

"Do! I would drive this poniard deep into her heart. I would murder her soul, if I could, by stabbing her dead body again and again. I hate her. I hate her, dead though she be."

"There—there—Zel; go, now, go! To-morrow night I will see you, but—"

"Wait!" she exclaimed, seizing him suddenly and pressing the point of her poniard for one instant against his throat. "If you fail, I will find you, and though a thousand furies stand in the way, I will kill you."

Then, without another word, she turned and fled from the room, leaving him alone with the corpse of the murdered Dora Lawrence.

The entire demeanor of Frank Tappen changed as soon as he was alone.

He sprang-to the table upon which the body of Dora Lawrence was lying, and, lifting the sheet from her face, he tenderly raised the lids of her eyes.

"I believe that I am right," he muttered, under his breath, "and, at all events, I'll risk it."

He stooped, and was about to raise the body from its resting-place upon the table, when suddenly he paused.

"Chick!" he exclaimed. "Where is he? Did that rascally doctor speak the truth, when he said that he was dead? If he is dead, his body is somewhere in this house, and if it is here, I will find it."

The man was no longer Frank Tappen.

The whole expression of his face had changed, and Nick Carter stood revealed.

He had laid his plans perfectly. He had secured what information he could from Tappen, and he had guessed the rest, and, with nothing else to guide him; he had presented himself at the dissecting-room, had been received as Frank Tappen, and not one had suspected the deception.

NICK did not pause long when he remembered what had been said about Chick, but went to work at once to rescue him, or to find his body, if dead.

But first he was resolved to make sure of the body of the girl, and therefore when he left the room, he carefully closed and locked the door, placing the key in his pocket.

Then he began a thorough search of the house, using his wonderful little lantern to light his way, and resolved to find some trace of Chick, if there was one to be found.

He knew the brave young assistant well enough to be satisfied that he had gone to that house with Dr. Quartz. He also knew that he was not there when he arrived in the character of Frank Tappen.

What had become of him in the meantime?

As Nick left the dissecting-room, he turned directly toward the trap-door through which Chick had fallen into the brine, after being shot by Zel.

The door was, however, cunningly concealed, nor was the detective looking for such a contrivance.

His foot was upon it, and he was about to pass on, when two things attracted his attention.

The first was a spot of blood about the size of an ordinary nail-head upon the floor in front of him, and the other was a slight sound such as a rat might make in falling into a cistern.

The latter came from directly beneath his feet, and even as he bent forward to examine the blood-spot more attentively, he listened for a repetition of the sound.

It was strange that he did not hear yet another, but his mind was so occupied in his quest for the missing Chick, and he was so sure that he had been left alone by the doctor and Zel, that he had no ears for strange noises, which did not bid fair to lead him to the hiding-place of his lost friend.

But there was another sound, and it came from the room that he had just left, where the body of Dora Lawrence was lying, covered by a sheet, when he left her.

The noise beneath his feet was repeated.

The splashing of water reached his ears a second time. Accustomed as he was to looking for secret doors, it did not take Nick long to find the trap through which Chick had fallen.

In a second, he raised it from its place, and threw it back.

As he did so, he heard a groan.

"Chick," he called.

"Here," came a faint response from the depths of the black hole.

"Are you hurt?"

"I am—nearly—dead. I—can't last much—longer. Help me—quick."

It was enough.

In an instant the rays of the light were cast into the hole, but, try as he might, he could not discover Chick. He threw himself at full length upon the floor, and held the lantern as far down as he could reach.

Then he saw him.

Chick was at one side of the loathsome place, and nothing but his head and one arm were visible above the surface of the filthy liquid in which he had been submerged. His head was covered with blood, and his right hand was grasping a slippery projection in the side of the pit.

"Help, Nick," he murmured, again. "I am almost gone."

"Stick to it a minute longer, and I will have you out," replied Nick, heartily.

He was quick to think, and quick to act.

In approaching the house in the character of Frank Tappen, he remembered to have seen an old ladder, half-hidden in the grass near the back of the house.

He went for it with a rush, and in fifteen seconds he was back again with the article in his grasp.

To place one end of it in the hole was but the work of an instant.

Then he began his descent.

Ah, what a foul and loathsome smelling place it was into which he descended.

But he thought nothing of that, for his object was to save Chick from a terrible death.

Down into the darkness, lantern in hand, he went, and as he descended, a form, robed in black, glided through another door, and bent over the trap.

It was the figure of Zel.

There was a fiendish smile upon her face, and her breath came in gasps like one who is gloating over a longed-for opportunity.

But in the short time that had elapsed since she had left Nick in the dissecting-room, a marvelous change had taken place in her appearance.

Then she had been a woman at middle age, with traces of a lost beauty upon her features; but withal, there had been something revolting and forbidding about her.

Now, all that was changed.

The gray hair had disappeared; the teeth which formerly had been "blocked" out had reappeared, and as she leaned over the abyss into which the two detectives had been forced, one could see that she was marvelously beautiful.

The contour of her face was perfect, and she looked like the queen of furies, as she gloated over the double crime that she was about to commit.

"So." she murmured, "I have them both; they are at my mercy, they are both in the black hole, and neither shall ever come forth alive!"

A beautiful fiend, she was nothing less.

In the meantime, Nick was steadily approaching nearer to his friend.

"Patience, Chick!" he called. "One second more, and I will have you."

He reached the edge of the foul liquid.

Then, with extended arm, he seized Chick by the collar, and dragged him upon the ladder at his side.

Chick was rescued, for the moment, but the reaction was too great for him.

No sooner did he feel the detective's firm grasp upon him, than the little remaining strength that was his, deserted him, and he fainted.

With a quick motion, Nick drew him up so that he could pass his arm around the unconscious body of his friend, and then, with one arm supporting Nick, and the other holding the trusty little lantern, he began to make his precarious way toward the top of the ladder.

But he had not taken a step before a sharp voice bade him stop.

With a start he raised his eyes.

There in the opening above him was a face at once so beautiful and so fiendish, and at the same time so strange, that he paused.

"Who are you?" he exclaimed.

"Don't you know?"

"No."

"I am Zel."

"Zel."

"Yes."

"But Zel is—"

"Bah! Nick Carter, you are a fool, after all. Had you asked to see my face to-night, when we were for a moment alone together, I would not have suspected you. But you did not, and I returned, and now, strong as you are, you are utterly at my mercy."

It was true, and Nick shuddered in spite of himself as he realized it.

If Chick were only conscious there would be some chance against this woman fiend.

But he was not.

To release his hold upon the faithful but insensible Chick, would be to allow him to slide back into the horrible pit beneath them, from which he could never be rescued again alive.

And there was no alternative for the detective.

He was at the woman's mercy, unless he dropped the body of his friend, and that he at once resolved that he would not do.

"If Chick must die, I will die with him," he thought.

Then the woman laughed—a low, musical ripple like the ruffle which precedes a hurricane upon the water.

"Do you realize that you are at my mercy?" she asked, slowly, and with evident delight in her words.

"Yes."

"Do you think that you can make terms with me?"

"No."

"How well you know me, Nick Carter."

"What are you going to do?" asked Nick.

"I am going to kill you."

"How?"

"So."

She held a bottle over his head and laughed again, fiendishly it seemed, and yet as softly as an houri.

"Do you know what this is?" she asked.

"I can guess," he replied.

"Guess, then."

"It is vitriol."

"What a good guesser you are, Nick Carter. Do you know what I am going to do with it?"

"No."

"Shall I tell you?"

"Yes."

"I am going to pour it over you where you stand. It is surer and more silent than fire-arms. Molten lead is cooling when compared with vitriol."

"Are you a fiend, woman?"

"Yes; listen. When the liquid strikes you it will burn, burn, burn! You will shriek with agony and horror, and I will laugh with glee.

"Then I will pour still more upon you. In your suffering you will drop your friend into the brine, you will release your hold upon the ladder to dig this liquid fire from your eyes, but you will dig your eyes out instead, and then, then, you will fall down and die."

And she laughed again.

EVEN the great detective, strong nerved as he was, could not repress a shudder of horror at the words of the woman bending over him, for he realized that she meant every word that she uttered, and that there was no way out of the difficulty into which he had thrust himself.

"See!" she cried, holding the deadly bottle above him, and tipping it until, involuntarily, a drop fell out.

It was but a single drop, but it struck him upon the back of his neck beneath the collar of his coat, burning like a drop of molten lead.

He gritted his teeth and bore it, making no sign, for he plainly saw that she did not know that she had dropped it.

Did she but know it, the accident would have been another fiendish suggestion to her, and she would have continued to let it fall, drop by drop, until she tortured him to death.

He realized that fully, and made no sign.

"See!" she repeated. "The cork is out, and I am tipping the bottle. Why don't you beg for mercy?"

"Why should I?"

"I might grant it."

"I think you are a she-devil."

"Yes, and a beautiful one, too, am I not?"

Nick shuddered.

"Beg!" she demanded, but Nick was silent.

"Beg!" she repeated. "I want to hear you plead for mercy. Beg, and I will give you as much time as you use in pleading. Beg, or I will burn you now."

Suddenly Nick started.

He was looking up into the woman's face, which he could see by the light of her own lantern.

Beyond her, in the gloom of the room above, he saw something which sent one ray of hope like a dart through his bosom.

"Woman," he cried, seeking only to gain a moment's time, "have you no heart?"

She laughed softly.

"Ah!" she cried, "she great detective pleads for mercy from Zel."

"Do you believe in ghosts?" asked Nick. "Do you have no fear that I will haunt you after this night's work?"

"Bah!" she cried, derisively, and laughed again.

"Do you not fear the ghosts of your victims? Do you not tremble in dread, lest Dora Lawrence should hover over you?"

"Dora Lawrence! Why should she haunt me? I had no hand in her death."

"Who had?"

"Do you want to know?"

"Yes."

"Your old friend Quartz killed her with one of his mixtures, and he made her fool of a husband believe that he did it."

"But if her spirit walked," persisted Nick, in a strange tone, as though his words were meant as a suggestion; "if she knew that you held a bottle of deadly liquid, poised over my head, over the heads of those who have tried to save her; if she hovered above you at this moment, knowing that, would she not seize the bottle and wrench it from your hand?"

Zel laughed; but even as she did so an arm was thrust past her head.

The hand seized the bottle, and tore it from her grasp, partially overturning it, and causing some of the fiery liquid to be spilt upon her own beautiful neck.

She uttered one loud shriek of terror and of agony.

With a cry that rang and re-rang through the house, she started to her feet and reeled backward against the wall while scream after scream hissed from between her lips.

The instant that the hand was stretched forward to seize the bottle, Nick Carter acted.

He knew that there would be no time to lose, and by superhuman effort he reached the top of the ladder just as Zel reeled against the wall, overcome by agony and terror.

The figure of Dora Lawrence stood in the center of the room in all the fine array of her burial dress, just as she had risen from the table where Nick had seen her last.

One hand held the bottle which she had torn from Zel, and the other still grasped the sheet with which she had been covered when she had lain upon the table in the dissecting-room.

But the sheet, and the arm that held it, were dripping with blood, and the hilt of the same jeweled poniard, which Nick had seen in the hand of Zel earlier that night, protruded from the inner side of her arm near the shoulder.

Like a flash, Nick saw through it all.

When Zel had returned, she had crept into the dissecting-room.

Not finding him there, she had carried out the fiendish purpose which she had sought to accomplish before—that of stabbing the dead body of the beautiful Dora.

But in the dark, her aim had not been sure, and instead of piercing the heart, as she had intended, the poniard had penetrated the inner side of Dora's arm.

Then the woman had crept away again in search of Nick.

But Dora was not dead.

The victim of one of Dr. Quartz potions, she was in a state so closely resembling death that all had been deceived.

The stab, in opening a vein, had revived her.

With returned consciousness, though dazed and bewildered, she had started up and wandered, with the sheet grasped tightly in her hand, in the direction of the sound of voices, and she had arrived just in time to save Nick Carter from an awful death.

His words had told her what to do, and although scarcely conscious, she had acted.

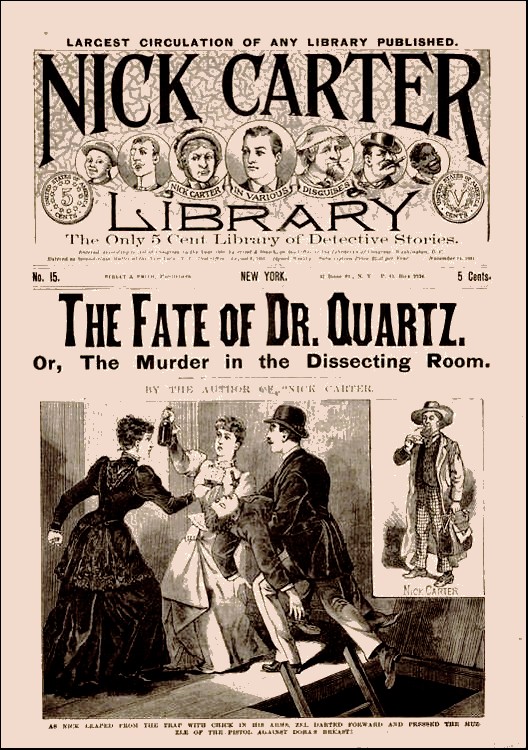

As Nick leaped from the trap-door with Chick in his arms, Zel, who was suffering untold tortures from the burning liquid that had been spilt upon her neck, suddenly leaped away from the corner in which for an instant she had been crouching.

Again she drew the weapon with which she had fired upon Chick, and so nearly ended his life.

But this time the object of her attack was Dora Lawrence.

With a cry more resembling the scream of a cougar, than anything else, she leaped forward until the muzzle of the pistol was pressed almost against the unfortunate girl's breast.

Then she pulled the trigger.

But the weapon was not discharged, and now, utterly beside herself with fury, she turned just as Nick leaped toward her, and, seizing the bottle from Dora's almost senseless hand, she cast it with all of her strength, straight at the detective's face.

It struck him on the forehead, and he staggered backward from the shock of the blow.

But the bottle had turned, and although the terrible liquid was spilled, it did not touch him.

Then, before he could recover in time to seize her, Zel turned and with another shriek she darted through the door which Nick had left ajar, he had brought the ladder with which to rescue Chick, and disappeared.

After her went Nick, but Zel had come prepared, and when he reached the outer air, he heard the sound of a horse's hoofs upon the roadway, and he knew that the woman had, for the time at least, escaped.

Her black horse had been ready, and, with two bounds after leaving the door-way, she was upon his back and galloping at a furious pace from the scene.

Nick hurried back into the house.

There, upon the floor, was stretched Dora Lawrence in a dead swoon, while Chick was just opening his eyes to consciousness.

In an instant, the detective decided what to do.

He bent over Chick, and held a flask of brandy to his lips.

"Are you all right lad?" he said.

"Yes."

"Then I am going. Stay here with this girl, and I will send somebody to your assistance at once. Be on your guard, for there is need of it."

It required but a moment for him to bind a handkerchief tightly upon Dora's arm above the wound.

Then, withdrawing the poniard, he thrust it into his pocket and darted away.

Down the road through the darkness, toward the village, he sped as fast as he could run, for he knew that he must reach the village without delay.

On, on, pausing but once, when he was passing the house of a worthy practitioner of medicine, to whom he hastily related the occurrences of the night, and having enjoined secrecy for the present, sent him post haste to the Morgan place to care for Dora and Chick.

Then on again, never pausing until he reached the house where Dr. Quartz masqueraded as the aged Dr. Agate.

When he reached the front door, he did not ring for admittance.

His peculiar little instrument before which all locks were of no avail, was brought forth, and the next minute he passed into the house, and closed the door behind him.

"Am I too late?" he murmured, "or shall I find them here?"

He paused and listened intently.

For a moment, there was not a sound, and then he fancied that he could hear a faint noise from the room over his head.