RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

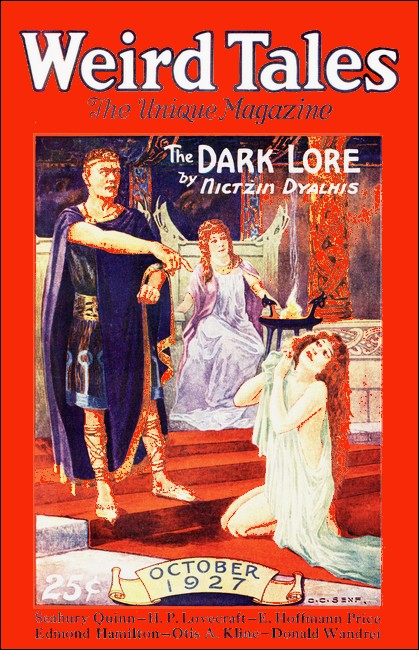

Weird Tales, October 1927, with "The Dark Lore"

"Back to Nak-Jad!" cried Grarhorg

AS an occultist of some thirty years' standing, it has been my

lot to listen to some strange stories and tales, for I have been

called upon to hear confidences, some of which were horrifying in

the extreme—things which almost appalled me, but never

quite, for two reasons. One is that mice I myself passed through

an experience so frightful that nothing happening thereafter has

ever availed to wholly upset my equanimity. And the other and

more important reason is simply this:

The Great Law is just! Equal and opposite vibrations cancel each other. Sin as deeply as one may, still redemption is possible, nay, certain, after the equivalent proportion of suffering has been experienced. Thereafter, whoso has sinned may build Sin's opposite of Good until the last scars of Evil are erased from the sight of men and angels, and the soul once again shines stainless...

Repeatedly I have emphasized this to those poor, sick souls who have crept to me, sobbing out their griefs, fear-stricken, all hope vanished, yet desirous of relieving their sadly overburdened minds by "talking it over" with one who could at least sympathize because he could understand, and who, they knew, would not shrink from them, poor spiritual outlaws though they might be.

So, to me has been granted a privilege that has brought tears of humility to my eyes many times; the highest and holiest privilege to which the eternal-living spirit may hope to attain while still inhabiting the body of the flesh—that of sometimes reassuring and comforting a fallen soul that has been drawn into the abomination of desolation, clutched by the grisly hands of the powers of darkness. And because I have been, perchance, of some slight help along such lines to them, there are a few who speak of me as a "soul-doctor."

Yet never, I say this truthfully, have I betrayed a confidence reposed. True, I have given some stories to the world, as I may give others. But always with the consent of the principal character involved—never otherwise.

And now, by her actual, expressed wish, I release the terrible story told me in her own manner by her who was once upon earth named Lura Veyle.

I CAN recall, dimly, a time when I was innocent, spotless of

soul, and with a mind unstained.. But that was ages ago, if time

be measured by experience rather than by the hands of a clock.

Yet now, as earth-years are counted, I am but forty-one.

Oh, this hideous burden of memory! Can it ever be lightened? Horrific thoughts swarm up from the lowest depths of my consciousness wherein I have tried to bury them— stifling, choking me till speech becomes an overwhelming exertion.

Great sin have I wrought, power and triumphs unearthly have I known, arrogance has made of me first an evil-doer against all spiritual laws; and afterward an abject slave, exposed to the insults, jibes and derision of the leering legions of the Haters and Mockers infesting the outer voids!

Through hells unnamed till now I have passed, tortured and harried. From Flaming Furies I have fled in a blackness so dense it could be felt. Alone I have wandered over the rocky face of a burned-out world, devoid of any inhabitant save myself.

Deep has been my suffering—and I have merited it, every bit! Nor has all of it sufficed to blot out my sin. Atonement is very far from complete. Yet, with soul laden with shame, I have struggled so high already that I dare say "Thank God," without shuddering in terror lest even worse befall me for venturing to breathe that Ineffable Name.

Behold me as I am! A dwarfed, bent, crippled, warped hunchback. Hair hanging in wild elf-locks, gray and stringy, about my face. My face! It more nearly resembles that of an ape than of a woman. Blear-eyed, wrinkled, with evil writ so plain on my features that children run screaming and dogs bristle, snarling, as I pass. Yet I was, at twenty, considered the most beautiful young woman in a city noted for its examples of feminine pulchritude.

That beauty which was mine was my curse, yet not that alone caused my undoing and downfall. That was due to my unholy pride and self-conceit. Mortal happiness and the joys of earth were insufficient to gratify my inordinate ambition. Wherefore, in a world beyond this world I accepted pomp and power and dominion, and reveled therein; to the height of my desire and beyond, to horrors inexpressible.

I had a sister. She loved me. And so did I—love myself! She was my diametric opposite. Blond whereas I was brunette. Slender and petite whereas I was tall and voluptuously modeled. She was gentle and humble, and I, to my shame, was stem, cold, proud and haughty. She was kindly where I was cruel—ah! fill in for yourself all that was good-as contrasted to all that was evil, wicked; and whenever the finer quality was manifest, be very sure that while it was descriptive of her, never by any chance would it apply to me.

All that was good and holy she was, and I, filled with the seeds of all that was bad—unsprouted, then, it is true; but soon, all too soon, to crack open and rear a writhing crop of clinging hell-weeds that eventually well-nigh strangled my immortal soul.

One loved her, and she adored him as only a pure and good girl can adore the man of her choice. And I adored him too, or thought I did, from the first moment I set my eyes on him. I had been prepared to ignore "her Edwin." She had enthused too much about him. "What a good man-" until I was nauseated at sound of his name. Once, in a tantrum, I snapped:

"The sooner you two fools are married, the better for all concerned! After the honeymoon, when full acquaintance is established, perhaps we'll get a vacation from 'Edwin' and his multifarious perfections. He's just plain man like all the rest; and if you want my candid opinion, he's very much a 'he- sissy'!"

Even yet I can see the hurt look she bestowed upon me. But all she said was: "Wait, sister, until you've seen him. You'll love him, too."

I did—but not in the way she, in her innocence, meant!

There came a time when, during an interview which I deliberately schemed to bring about, I sought to turn his allegiance from her shrine to myself. And in terse, scathing phrases, he let me see, plainly, what a really honorable man thought of me and my attempt!

Humiliation, followed by a cold, deadly rage, suffused my entire being. Without further words I walked away from him. Nobody, observing us as we met at breakfast next morning, would have suspected that aught untoward had ever passed between us. Only he and I knew, and I knew, too, that very soon only I would ever know...

I'd heard the servant maids talking. There was an old Gipsy woman, too old to travel longer with the caravans. Her sons had purchased for her a tiny plot of ground and a small cottage near where Lost River enters Deadman's Swamp. The maids had whispered of love-philters, charms, spells... One said: "She will only see those who love when the moon shines... those who hate when the dark o' the moon prevails."

That old Gipsy was a disappointment to me. She heard me out, patiently. But she shook her head. Nor could a proffered bribe of a thousand dollars move her to change her determination.

"You do not belong in my circle," she said. "Nor does any that touches mine touch yours. I may not, dare not help you. Yours is a strange fate. You must work out your own magic wickedness or leave it alone. Yet if you desist from your purposes you will die from the hate-poisons in your blood. You had best go home and pray, then lie down and die. Otherwise, great evil will you wreak, although never on earth shall you be punished therefor."

In disgust, I left her presence, wordlessly.

But all that night one sentence ran through my mind, excluding all else:

"You must work your own magic wickedness or leave it alone."

An ignorant, illiterate, uncivil old Gipsy! There must be a higher, stronger magic. I wrote to dealers in antique books. They mailed me lists such as they compile for collectors. So, I gained insight into ancient arts; such lore as it were well for all the world had it never been known!

Two photographs I took to a sculptor of my acquaintance. In exchange for a smile and a few low-spoken words, meaning less than nothing to me, but which went to his head like a powerful wine, the poor, infatuated fool made me two figurines from a white clay. And the likenesses, though small, were very perfect. I'd assured him they -were intended as a wedding jest, and he believed me. What did he know of the Dark Lore? He considered himself overpaid when I allowed him to kiss my hand as I left his studio.

The terrible methods I employed in utilizing those figurines are best unrelated. None shall ever learn of that frightful sorcery from me, directly or indirectly. But—there was, within a month, a terrible auto accident. Edwin was unrecognizable. And she, my little sister, lived but ten days thereafter; a helpless, shuddering, apathetic wreck; vaguely moaning: "Edw'ee... Edwee..."

And I—exulted!

This is the curse of the Dark Lore —no sooner is one triumph achieved by its sinister aid than the drunken soul craves even greater conquests! And I was no exception.

Edwin? Was dead—through my spells, and lost to the world and me. But was he lost to me? True, his body I might never see more—but his spirit! Once again I turned to the forbidden books. And the Evil Powers beheld—and chuckled. On the night when I found that which I sought, there was mirth in many hells.

"THUS is the Mystic Lamp of the Adept prepared...

"But when ye shall come to light it, use ye not fire nor flame. Fairly in the center of a darkened chamber shall ye place it. Then must ye, circling about it, with w r oven paces and waving arms, whisper, at low breath the Spell to the Fire- Sprites; until at length, streaming from all fingertips shall a flickering flame be seen. So, hold ye one hand each side of the holy lamp in such wise that the streamers of lambent flame do unite at that spot where is the wick fashioned from the thrums of the Lapis Asbestus. And if all be well and duly prepared, ye shall behold a marvel indeed.

"Yet observe the color of the flame the Lamp gives out, for it will be the color of the soul of whoso made that Lamp. And should the flame be silvery, know that high spirits love and guard ye. Shall it burn blue like the vault of heaven, then stedfast shall ye stand against all evil, sin, or shame. If it be of golden hue, deep is the knowledge to which ye shall attain, and wisdom worthily used is good to have. But should it blaze scarlet, know it emanates from a wrathful soul. Crimson shall betoken a nature filled with wicked desires. Purple shall tell of pride and of high command, although this may be well or ill; for there be colors holy as well as unholy, which may be known by their softness or by their glare..."

Vivid, glaring crimson, tinged with hectic purple rays, flooded that darkened chamber when I completed that experiment. And my lip curled in scorn of all consequence as I read in that illumination my secret nature revealed. To an humbler soul it might have served as a solemn warning. To mine it was but proof that I was great, and would be greater.

Thereafter, for eleven days I made another lamp each day, which totaled a dozen. And on the twelfth night, I lighted them all at once. And each gave off that same glorious yet sinister brilliance as' did the first with which I had experimented. Grouped together they filled the room with intense vibrations, much as the overtones of some great organ would thrill the soul of a musician. I had dared much; but had succeeded thus far in all I had attempted. Always/the drunken soul seeks further conquest...

So, I drew the circle and the triangles, and at each angle save one I placed a lamp. The draperies of earth I removed from my person and tossed them aside indifferently. I was above all conventions, had cast off all inhibitions which hamper the mediocre. For I knew that power more than mortal was henceforth mine to wield as best pleased myself.

Then, with the remaining lamp, the twelfth one, held high in a hand which did not shake or quiver, I entered the magic circle—and only then did I close the gap in the mystic figure with that twelfth lamp. For several minutes I stood thus, reveling in the sense of my own importance and splendor, for I felt—royal! Then, with a wave of my hand I began the spell that should drag back the soul of lost Edwin from whatsoever dim realm it had reached. Once it had beheld my glory—knew my power...

It came!

That command was too potent to be disregarded. And I beheld a white specter that gazed at me with eyes mutely reproaching me for that which I had done to him and his... Disillusion!

That? The poor, feeble, impotent, contemptible ghost—it was not worth summoning! Its love? Absurd! With a wave of my hand and a curt order I banished it from my presence. But what, oh! what, was left?

In my mind, unbidden, unsought, there formed another incantation. I swear that never had I read that in any book. It was the clarion call of a soul athirst for love—the call of a soul high enough to be greatly daring —for that call would summon no lover from earth's weak children... I uttered it in clear, full tones. And I would that brain had shriveled and tongue withered ere I thought, and -dared, that unholy evocation.

Yet what ensued was anything save terrifying! Came a blaze of regal, splendid, somber purple and dusky gold; and, lo! just outside the magic circle stood one whose lofty bearing and prideful look bespoke him no lowly, common spirit.

His great, luminous eyes met mine and in their depths I read full understanding and mutuality of purpose. On his lips a slow smile hovered, proclaiming louder than words the extent of his admiration of myself.

But back of him!

Rank on rank, stretching away in space as though no chamber walls existed, were ranged a throng, hardly less glorious than was he in appearance. Who or what he might be, I knew not—then. But one thing was very evident, would have been clear to a duller wit than mine—he was their Master, their Leader, their Overlord.

And mine!

None who has not faced such a being can comprehend the subtle urge which I knew then. Never thereafter for me could there be inclination toward mortal man, not though one such should lay at my feet all the treasures of Goleonda.

That mighty being was kneeling just without the barrier of the protecting circle. His arms were outstretched, his fingers barely avoiding passing above the mystic lines traced upon the floor. And I—I laughed in his face. But not the derisive laughter of scorn—nay! it was the laugh with which a woman greets her well-beloved.

"Thou art a—demon?"

"Call me that, if thou wilt—thy 'demon-lover', and I'll be content!"

"But what, then?"

"A rebellious Angel—I!"

"Lucifer?"

"Not so—yet his co-equal!"

"Who, I said?"

"Hesperus!"

"And I?"

"Shalt share my throne and power!"

"On earth?"

"Here—and hereafter!"

Again I laughed. Triumphant. Thrilled at my evident power over such a being. But not thus easily was I to be won. I would make certain of his love.

"Nay, not tonight!"

He rose to his full height, folding his arms across his breast. His brilliant eyes flamed into mine—there was not a yard of distance between us, for I had unknowingly drawn close to the edge of the ring "Pass Not."

"Thou wilt summon thy Hesperus again, O Beloved?" The cadence of his tones thrilled me as never had I thrilled before.

"Assuredly."

"Soon?"

"Perhaps."

"A token from thee, my Queen, ere I depart?"

What had I to bestow? Then I remembered. On my finger I wore a ring set with a black opal. It had been my mother's and her mother's before her. But, surely, it was mine now. It should have been sacred. But what was sacred to me—then? I stripped it from my finger, kissed it, and tossed it to him. And by that one piece of folly gave him a focus whereto he could always direct his thoughts, so, reach me, invariably, at his will! But I knew not that, at the time. Would that I had! The blaze of splendor—triumphant—from his eyes, well-nigh intoxicated me! I reeled backward to the center formed by the interlaced triangles. It was a genuine physical effort to keep from rushing forward again—to his embrace!

For a full hour I stood there, still guarded by the power of those protecting symbols I had traced upon the floor; accepting homage, as one by one his attendant host of lesser fallen angels and fiends and demons filed past me; each in his turn bending the knee and bowing his head in subjugation to their Lord's choice— their Queen to be! He, last of all his subject throng, saluted precisely as had the least of his followers. Then he, too, vanished, and I was alone.

THAT night I slept fitfully. Visions of pomp, and pride, and

power filled my mind to drunkenness. Little could I recall of

them when daylight filled my room, but while the dreams lasted,

they were gorgeous. No one had entered my room, that I knew, for

the door was locked on the inside. Yet on my dressing table I

found a necklace the like of which never was known on earth

before.

It was a long chain of some dusky yellow metal, neither copper nor gold. The links were strangely wrought and intricately twisted. Pendant from every link hung a transparent, ruby-colored stone; each one fashioned artfully to the semblance of a small human heart. And, most peculiar feature of all, while each heart- shaped stone was in reality smooth, yet at a casual glance each one seemed to be actually sweating drops of blood!

A jeweler to whom I showed them said it was due to some peculiarity of crystallization; but he could not for all his skill and his experience of years name the stones; and he was a sorely puzzled man. Nor was he at all pleased when I refused to tell him whence I had them. All I would vouchsafe was: "Oh, a gift from a ruling Prince—an admirer..."

I wore the gift of Hesperus, for such I knew the necklace to be, to a ball that night. I was never popular with the members of my own sex, but on that night it seemed to me that many who had at least formerly pretended to be nice to me acted as though they actually feared me. There was a truly great statesman there. I had never formally met him. But as I passed him during the course of the evening, I saw such involuntary admiration betrayed in his eyes that I favored him with a dazzling smile.

I heard him query of the lady to whom at the moment he was talking:

"Who is that superbly beautiful creature?"

"Lura Veyle," she snapped, all out of patience with him. "Stuck-up thing..."

He contrived to get himself introduced to me. It was easily accomplished. There were mutual acquaintances. We did not dance. We sat— and he talked. He was a brilliant conversationist, and on that occasion he fairly outdid himself. Inwardly I smiled. It was so obvious. Later he wheedled me into accompanying him to a dimly lit balcony—"for a breath of fresh air," he said.

I'll admit I was flattered by his attentions. What woman wouldn't be? Hardly were we alone than—it was highly improper, especially from one such as he, with his social status— he attempted to slip his arm about my waist, murmuring: "I know— dear—it's presumption on such short acquaintance, but—Lura—I-"

It was as far as he ever got! Even in that half-light I saw his eyes protrude; while over his face came a look of unqualified terror. His knees gave from under him and he slumped down, whispering, "My—heart—"

Naturally, I shrieked! He lived barely long enough to gasp, audibly, so that others as well as myself heard him: "The—Devil—"

Truly, I knew myself the beloved of Hesperus!

OF course, the tragic episode broke up the ball. It was then

just a few minutes past midnight, and naturally, all the guests

went to their respective homes. I, however, had no intention of

losing any sleep because of the regrettable circumstance.

Wherefore, by 1:30 I was in my bed and sound asleep. But before

2:30 I was once more wide awake. Moved by an impulse I did not

pause to analyze, I arose, donned a light kimono and slipped from

my room to that empty chamber wherein I was accustomed to perform

my strange and unhallowed practises.

Deliberately I caused the mystic lamps to ignite, and equally deliberately I refrained from drawing the protecting lines of the mighty ring "Pass Not," although I knew full well that unless I stood in the center of the potent dodecagon formed by the interlaced triangles, there would be no protection or safety for my spirit from the Haters who Haunt.

Yet I, in my arrogance, ignored that awful danger. It was well enough for lesser souls, I thought, contemptuously, to take all due precautions; but for me they were superfluous, puerile.

Was not I the beloved of the great Hesperus? Most assuredly, yes! Then what lesser powers dared molest me, when to do so would be to incur die full wrath of their puissant Overlord, whose terrific vengeance could nowise be escaped or averted?

Even more rashly, that I might omit no single detail which could aid in filling my cup of folly brimful and running over; after I had cast aside my earthly habiliments, with the exception of that wondrous necklace of many-oolored, bleeding stone human hearts, I once more voiced that same incantation that had first brought my Dark Angel to my presence.

I had not uttered a third of the spell ere he arrived! And wondrous power that was his, for one moment he was a mighty spirit, devoid of material substance; and the next moment, his was a form as solid as my own, into whose arms I yielded myself! Our lips met—and in the next instant—I was in the halls of hell!

Nor have I ever seen that body which was Lura Veyle since!

But I presume that they—my relatives and friends—interred the inert form with appropriate ceremonials; and praised the departed soul; and mourned my loss, after the fashion of earth's dwellers.

I suppose I should have been either terror-stricken or else enraged, because of what had happened to me. But in truth I was neither angry nor frightened. I say it honestly—my sole reaction to that stupendous change was a certitude that I had reached home! For I actually felt thus. I had attained to my own proper place, my true environment!

To my added satisfaction I found that I was robed in splendor far surpassing the fairest dream of any earthly costumer. On my brow was a scintillant diadem of many-colored jewels. In my hand I was holding a scepter of gold, gem-studded, tipped with a great amethystine stone which was carven into a symbol strange to me; but which, I knew in some indefinable way, possessed in itself some very potent properties.

Obviously I was in a palace—the palace of Hesperus, Ruler of one of the realms of hell. Equally obviously, I was in a chamber which had been prepared against my coming, for it was virtually a duplicate of my own personal room back upon earth; excepting that the furnishings and fittings were of more splendid material and finer workmanship. I was standing before a great mirror, and reflected therein I could see myself as I was in all my glory.

Kneeling just before me, but one at each side a trifle, so as not to interfere with my view, were two shapely, nude, coppery- colored female slaves whom I rightly took to be there in the capacity of hand-maidens to my own royal self.

Oh, my soul knew where I was, and all that had happened, yet I pinched myself in several places—then I grasped one of the maids by the hair and tugged! The abject creature emitted a whimpering yell. I released her.

"But—but," I said, uncertain if they could understand my speech, "I seem—solid—as ever. You seem— solid..."

One, not her whose hair I had pulled, replied:

"O Regal Lady! Let this slave explain. Only your earth-body have you departed from. When you are not in it, it can not feel. You are now here. That which felt while in the earth-body now feels here... Only one envelope have you abandoned; and the self has many envelopes yet remaining. Each resembles, but more—thin—the outer one. Only it is really the other way about—for each one, going outward, is like the inner one, but coarser as one becomes more thick, until the greatest thickness is found upon earth...

"But when the earth-thick body is hurt, scars remain. Here no matter how badly the form may be injured, the wounds shortly close again—unless one is condemned to—destruction —by our Master..."

The slave faltered in her speech, while a look of ghastly fear overspread her intelligent features. Very low she whispered: "Before—destruction—are many—horrors to be undergone—then—the self is—thinner—in a different, but not less awful—hell..." and again that look of ghastly fear hinted at the untenable...

There ensued for me all the splendor which lay within the power of Hesperus to bestow. Feastings, revelries unholy at which I presided co-equal with him; glories and triumphs unimaginable; ecstasies so thrilling that mind can not in soberer moments comprehend such; and I was taught control of powers and forces stupendous; received homage from beings splendid, beings grotesque, and beings—or fiends—of malignancy so hideous they nearly appalled even my over-bold soul to gaze upon. These, all these and more, were mine for a period covering several earth-years; for in full compliance with his given promise, Hesperus proclaimed me his Queen, and I shared his throne and his authority.

However, these matters I do not enter into detail about, for it is not of my triumphs and the gratifications of my inordinate ambitions, vanities, and arrogance that I would tell, but of what came after. But even before the crash occurred, I should have been warned, for there were times when I deemed, vaguely, that I detected a fleeting sneer on more than one countenance as some spirit, or fiend, bent the knee before me and bowed the head in token of subjugation.

But ultimately I could not conceal from myself that Hesperus was neglecting me; stating quietly that important affairs which concerned me as well as himself were demanding all his attention. And, perforce, with that meager explanation I must needs content myself. Finally, though, at a great banquet held in celebration of a victory over some band of Angelic Ones from a higher plane, my fate came upon me with a certainty leaving nothing to be hoped for.

As I entered the great hall by one portal, through another came Hesperus, and at his side glided with serpentine grace one who—I recognized the fact at a glance—had originated on some planet far different from that earth whence I had fallen!

The mocking smile on her curling lip was all too unmistakable. Rage suffused me. All the hell-nature that was mine rose up, rebellious; gone were all fears of consequences to myself, and naught remained but hate and—revenge!

Long ere this happening I had learned one of the uses of that amethystine-tipped scepter. What injury it could inflict—if any—on the actual spirit, I knew not; but to the various layers, or shells, or souls—call them as may be most suitable—I knew that it could do much. With wrath sufficiently intense suffusing the bearer, simply by pointing at the hated one with that symbol, annihilation of all which was visible ensued, abruptly.

And it was full at the towering figure of the Arch-Liar Hesperus himself that I directed its full potency, rather than at the beguiled fool swaying so gracefully triumphant, serpent-like, at his left side.

And nothing happened!

Only, a yelling, screaming, hooting, howling tumult of demoniacal laughter rocked that vast hall to its very foundations. The merriment of the utterly damned, rejoicing at the humiliation and the shame of her to whom, formerly, they had rendered abject homage!

Reverting to earthly methods, I drew back my arm and hurled that accursed scepter at the gravely smiling countenance of the Arch-Liar. Languidly he held up a hand, and the whirling scepter floated, light as a feather, into his grasp.

And a moment later, with no volition of my own, I found myself, denuded of all my regal robes and ornaments, crouched like any abject slave at his feet, helpless, unable even to move! While all about us crowded and jostled and swirled that fiendish throng, mocking, jeering, reviling me, gloating, appraising that beauty which was mine, so ruthlessly revealed.

SUDDENLY Hesperus singled out one from amongst that hideous

mob. "Thou," he commanded.

The monster approached, bent the knee in fealty. I shuddered with horror at his aspect. A dreadful premonition overwhelmed me, and with it there came despair absolute, unleavened by any hope! I knew my fate.

I can not adequately describe that —oh! what shall I term it—or him! All that I can say is—it was a huge, hairy-appearing brute, altogether bestial; yet in a way a most amazing travesty on the human type. Its back was furry, but what seemed to be hair, I learned later, was in reality more closely allied to the quills on a porcupine, although longer, thicker, and more sharply pointed. Its front was scaly skin like an alligator's under-parts; and its awful, cruel face and head were of some horny substance closely resembling the upper shell of a turtle.

Add to all this two round, black, lack-luster eyes, staring lidless, with a dull red glow showing beneath their inky surfaces; and two upper eyeteeth so long that they hung always bared nearly to the chin of the Thing —and you will have then but a poor and feeble word-picture. Its sole weapon w 7 as a ponderous, spike-studded bronze mace, nearly as long as the monster was tall.

"Thy name?" Hesperus demanded.

"Grarhorg!"

"Thy rank?"

"Guardian of thy watch-tower of Nak-Jad, standing where thy north frontier o'erlooks the Gorge of the Gray Shine."

"A lonely, a drear, and a dangerous post," Hesperus said reflectively, while the rabble ceased its clamor in anticipation of that which was yet to come.

"All that," growled the beast-fiend, truculently. "Yet I hold it fast, under thee. Naught from the north has ever passed thy border unbidden since thou didst commission me the Guardian of Nak-Jad."

"The force under thee?"

"Composed of Yobwins, Sogmirs, and Miljips. A mixed array, a bare ten score; but sufficient, under me."

Hesperus nodded approbation of this modest speech.

"Thy recreations are-?"

"Holding thy line inviolate, as bidden."

"But thy followers?"

"Find it suffices them that I am not displeased. Nay, are they nobles of thy court, that they should know delight in soft dalliance?"

"Thou art bold, Grarhorg," Hesperus reproved sternly, but a moment later he fairly smiled with delight when Grarhorg, nowise abashed, retorted grimly:

"There is need of boldness in him who can hold Nak-Jad secure!"

"See, my Grarhorg"—Hesperus indicated miserable me crouched there between them as they faced each other—"here is some slight recompense for thy labors, a comfort in thy loneliness, and a toy for thy idle moments."

"Mine?" The monster seemed incredulous.

"Aye," nodded Hesperus, "a toy for thee."

A huge paw, with claws as long and as sharp as those of a bear, clamped down on my bare shoulder. I was tucked under the hideous fiend's arm as though I were an inanimate bundle. In a voice as harshly reverberating as the bellow of a great bull alligator, such as I have often heard by the river near our family home upon earth, the monster roared, exultant: "Grarhorg, for this, will hold Nak-Jad safe though thou wert—pardoned!"

Even Hesperus laughed outright at the absurdity of that possibility; but that usurper Starling, swaying serpent-fashion beside her new Lord, asked, furthering the jest: "But why, Grarhorg, after he were pardoned?"

"Because he would soon return," retorted the brute. "What, do I not know my Lord by this time?"

"Enough of this," exclaimed Hesperus when the laugh died down. "Let the feast commence." He would have led the way to the long tables but Grarhorg spoke once again.

"Thy leave to return to Nak-Jad— now?"

"Small honor dost thou do us and our feast," Hesperus replied. "Why such haste?"

"This—my 'toy'," explained Grarhorg succinctly. "There is meat to be had in Nak-Jad for the eating, as well as here. Let this infant depart with his plaything, O mighty Hesperus."

"Farewell, sweet babe," mocked Hesperus. "Thou hast my permission."

Grarhorg, with no further words, turned from the festivities and strode out of the great hall to a wide, high-walled courtyard where he opened his ugly gash of a mouth and emitted a raucous howl. Came the swishing of mighty pinions, a fetid odor, and, swooping down from the air above, a winged nightmare descended.

It had the head of a crocodile, the neck of a serpent, a lizard's body, the legs and talons of a vulture many times magnified, and the wings were those of a gigantic bat. It towered above the huge Grarhorg half again as high. Grarhorg caught me by the neck in one great paw and held me out to the nightmare.

"Carry this—thou," he rumbled. "Harm it not—or I harm thee!"

The sinuous neck arched, the ugly head shot downward, and the bony jaws seized me by the middle. I felt every sharp-pointed tooth sink deeply into my waist, piercing me through and through. Writhing and screaming in agony unbearable, but which yet I had to endure, I beheld Grarhorg clamber to the back of the nightmare and seat himself where serpent neck joined lizard body. Smiting his frightful steed a heavy thump with his bronze mace he yelled:

"Back to Nak-Jad!"

I was but a sickly, whimpering, moaning, semi-conscious limpness when the Blood-Red Tower was reached. And that edifice I can not describe at all. I was barely aware that that nauseating breath was no longer scorching my middle at the same time that both extremities were almost freezing from the intense cold of the air through which we had flown at a speed incredible. Dimly I could perceive a building and that its color was scarlet-red; but thereafter I never saw again its outside.

Grarhorg, descending from his seat on the nightmare's back, received me in one capacious paw and strode through a narrow door...

It is not within the scope of the human mentality to comprehend an infinitesimal portion, even, of the soul-nauseating outrages and degrading debaucheries to which I was subjected... Grarhorg—eventually tired—then—

Ensued a period so dreadful I lost even the concept of time. There were... Yobwins; Sogmirs; Miljips... each worse than the preceding ones... argh! I—I—

An abominable Sogmir, who, at his best, was fouler, more cruel, viler even than Grarhorg was at his worst; wearied, too... as a new amusement, grasped me by the ankle, whirled me about his head, and, sufficient momentum established, he released his hundred-clawed clutch, sending me hurtling headlong, headlong, through a window in the lower story of the Red Tower of Nak-Jad, out into empty space! I fell as falls a shooting star, down and down into the ghastly Gorge of the Gray Shine!

Actually I could hear the squelch as my form struck bottom! Saw the frightfully mangled form which had been so sickeningly tormented in Nak-Jad lying there, writhing, twitching, in feeble, expiring convulsions; until slowly the final quivering twitch indicated that the end had come. And realized that I myself had stood apart during all this, and had, in fact, but lost another of my shells; had now a new one in which to functionate; and was, in reality, but become more thin.

And oh, the relief of it, after Nak-Jad and—

SHRIEKING, sobbing, wailing and moaning in hopeless horror

afresh, I whirled about and fled down the sloping bottom of the

Gorge; for close behind me, with shrill whistlings and high-

pitched pipings there raced a dozen or more luminous-shining

skeletons, remarkably human in appearance; except that upon earth

any one of them would have measured at least twenty feet in

height, yet not one of them would have spanned, at the waist, to

the bigness of a fourteen year old boy.

The bottom of the Gorge was for a long way as slippery-smooth as glare ice; and I skidded and slithered and slid as I ran, while behind me came that skeleton hell-brood, and they experienced not the slightest difficulty in maintaining their footing.

By what method can earth-time be measured in the many hells? Was it an hour—or a day—or an eon that I fled, and those ghastly things pursued? How may I tell? If horror is any criterion, it was an eternity of flight, spurred on by a nameless dread of consequences beyond even my concept, should I be overtaken. But oh! that Gorge seemed endless between those towering walls wherein that lone and sorely affrighted soul that was myself fled, wailing.

How or when or whence it came I had not noted, but I discovered that I was, for the first time since Hesperus cast me openly aside, once more arrayed in a robe. It was of some' grayish, shining' texture. It floated behind me like a filmy veil as I sped along on fear-driven feet. Then, suddenly, the robe was tight against my back as an icy wind blew shrieking down the Gorge.

That robe acted somewhat as a sail, which helped me, as it held part of that ponderous wind which swept me onward and forward. But that same wind helped my pursuers not at all, as their more open structures failed to catch or hold any assisting pressure from it. I began to have hopes...

And as usual, in those infernal regions, hope springs up but to add another and keener torment when the hope dies horridly... Abruptly I came to a halt. Incredulously I gazed, as well I might. For a very few more steps would have precipitated me, all asprawl, into a vast lake of dark blue slime or ooze! The Gorge of the Gray Shine had terminated. And that lake had no beach. Sheer cliffs rose on both sides of the mouth of the Gorge. And behind came on, avidly, that luminous skeleton crew. One, evidently fleeter than his fellows, was even then within reaching distance. His bony claw caught me by the throat. The piping whistling he kept uttering resolved itself into words:

"Thick—thick—like you! I shall draw strength and be thick..."

Desperation and nausea aroused wrath within me. Wrath such as I had thought was obliterated completely from my nature, slain beyond all possibility of re-arousal during the loathly depravities to which I had been subjected while in the power of the demoniacal vilenesses who inhabited the Blood-Red Tower of Nak-Jad.

There, at first, I had tried to fight against my fate, in regal indignation, for I had not then lost my pride and arrogance, even though I no longer queened it by the side of Hesperus.

But such awful punishment had been dealt me by Grarhorg that it very effectually slew the last temerarious thought of resistance. So that thereafter I had dared do naught else than tamely submit to whatsoever of humiliating degradation he might choose next to inflict upon his— "toy." And after he had become wearied of me and had cast me to his legion—I had been in even worse plight, likewise endured inertly, indifferently at times, when the overtaxed spirit could no longer recognize varying degrees of agonized, excruciating suffering.

All this was flashing through my mind as that bony grisliness clutched me by my throat. But at that chill touch, the rapidly mounting wrath within me exploded. Exerting a strength I knew not before that moment that I possessed, I struck violently at that pallid white forearm. It broke! Broke like a brittle twig! The fleshless, thickless fingers fell at my feet. In my turn I grappled that elongated animate skeleton and lifted! It was feather-light. I hurled it from me out into the Lake of the Dark Blue Ooze!

"You would be thick!" I screamed. "Wallow there, then, and soon shall you become thick indeed!"

"You would be thick!" I screamed. "Wallow

there, then, and soon shall you become thick indeed!".

The skeleton fell on the surface of the slimy lake, but did not sink, for the stuff was too dense; although it was not exactly solid, either, being more like the gumbo mud of my natal region upon earth. After considerable struggling the animate abhorrence got to its feet, but it no more resembled a skeleton. I had plenty of time to watch; as the other members of the pursuing band had halted in a hesitant group.

I laughed, openly, mocking them. Actually, I had at last encountered some things that were afraid of me! Yet, I knew that, did I attempt to retrace my steps and go back up the Gorge, they would be upon me like so many ravening wolves; and against such odds I could not dare to contend. Also, doubtless, there would be many others like them, and probably things even worse to be encountered should I escape them, so long as I should stay in that Gorge.

I turned again to observe the thing I had flung into the lake. It was no longer pallid white. Rather, it more resembled a corpse decaying and blackening from putrescence. It was not a pretty sight, even to eyes such as were mine, inured to horrid sights. It had accumulated all the thickness it could carry, and too much; albeit not of the sort it had desired so avidly. As I watched, its knees buckled, over-weighted, and it went down and stayed prone. Slowly, very slowly, it partially settled into the gummous ooze.

A wild idea possessed me. Upon earth the suicide disposes of one shell at least, speedily. Already I had lost two, and could have not so very many more remaining. Behind me were the animate skeletons who waited... and before me the Lake of the Dark Blue Ooze. Well I would intentionally cast myself upon the bosom of that sinister-appearing Lake, and if the ooze swallowed me, then I would have rid myself of all my woes at a single stroke. And if I should find that I had but lost another shell, with others still remaining, I'd no longer flee from any menacing Things; but would, rather, welcome them as unintentional deliverers.

I RUSHED out upon the surface of that ooze and found that it

would bear my weight so long as I kept moving rapidly. I sank

barely to my ankles in most places, although at times I would go

down half-way to my knees. So I decided that I'd not lie down and

quit, but keep going. Who knew? Perhaps even hell had its limits!

Occasionally I stood on one foot and scraped the sticky stuff

from the other and then reversed the operation. And so, went on,

and on, and on.

Two red suns hung in the sky, close together, revolving about each other slowly. Apparently they never set, for the plane of their orbits seemed to be parallel to the surface of the lake. As I looked back, the cliffs where the Gorge of the Gray Shine debouched showed but as a dim, dun cloud. Ahead I could faintly see another shore showing as a purplish-black bank of cliffs. Was I at the bottom of a huge bowl with unscalable sides? Or would there be a way-out—and if so, into what would it lead me of further horrors unguessed?

But I was thinking too far ahead, borrowing trouble when real trouble was awaiting me but a few yards ahead of where I then was. If the evidence of my sight was to be relied upon, I was approximately half-way across the lake. And just in front of me was a genuine pool, a lesser lake of clear, limpid fluid within a greater lake of viscous ooze.

The pool mirrored the red suns, and, vanity not yet wholly dead within me, I bent above its surface, desiring to see how I appeared after all my many vicissitudes. And a long, whiplike tentacle whirled upward from the depths, barely missing my face! Another instant, and that pool was aboil with squirming, writhing snaky feelers that came over the edge and secured fast anchorage on the surface of the ooze. Another instant still, and great purplish-pallid globular bodies hove themselves up from below and pulled themselves out upon the ooze which easily supported their weights. Great, round, black, lackluster eyes, horrifically reminiscent of the baleful eyes of Grarhorg, were glaring into my own wildly staring orbs!

I howled—howled—in maniac frenzy, and, catching up my robe, for I sorely needed free use of my members, I departed, full speed; howling at every jump! And those damnable things, octopods, or rather, polypods; for each had many more than eight legs; swarmed over that slimy surface much faster than I could run.

Short indeed was the distance I covered before I was overtaken. One clammy tentacle had me by the waist, hauled me back so violently that I went sprawling flat—and was at once the nucleus of a heaving, feasting mass that was drawing through many rubbery suction cups, wherewith each tentacle was provided, the substance composing that form or shell serving me as a body. I could feel ropy strips of substance pulling away from me to the accompaniment of such rending and racking tortures as I had never before then undergone. Nothing which Grarhorg and his myrmidons...

The globular, many-tentacled ghouls were slowly crawling back to their limpid pool, leaving me lying there. With a shock I realized how thin I had become. Then realized that I no longer hurt. Slowly I comprehended what had actually happened. The ghouls had depleted so much of my thick that I had become invisible and intangible to them; so that, to them, I was as one wholly devoured, leaving nothing more to be assimilated.

Then I noted another fact. In actuality I was no longer in contact with the surface of the ooze; but was floating at an appreciable height above that gummy slime. I was in a horizontal posture, but as soon as I attempted to assume the perpendicular I was successful. So, off I set once more, heading for the black cliffs ahead. My progress, for I was literally walking on, or through, the air, was so restful after my wild race from the ghouls, that it seemed no time at all ere I was looking up the towering walls and wondering how I was to surmount them.

I caught myself wishing that I could fly. Dimly, somewhere in my consciousness an earth-word was urging remembrance... what... again... "Levitation..." what was that? But even as I was thinking—as the meaning came—so I began to float upward, slowly at first, but as conscious will took charge, faster and faster—I was atop!

EVEN at the cliff-lip the light was so dull it was a dusky

twilight; and but a short way inland, it was black as black could

well be. Nor, try as I would, could I levitate myself above it.

Yet I dared not go back the way I had come, and the narrow strip

of twilight zone seemingly terminated but a few yards in either

direction from where I stood. With no alternative I walked

directly away from the cliff-lip and into that dense pall of

blackness.

Hark! What was that rumbling, rolling reverberation? Thunder, of course.... Again! Thunder? Perhaps... And once again. And that time I became positive that whatever it might be, thunder it certainly was not! Peal on peal that heavy rumbling shook that dense blackness-peal on peal of Gargantuan laughter!

At me? And if so, why? It simply couldn't be directed at, or caused by, my own small and thin self. There was not sufficient of importance about one poor, disconsolate, lost soul to occasion all that disturbance!

I decided I would head directly toward its source. But that was more easily decided upon than accomplished. It was ahead! It was back of me! Only it wasn't back of me at all! It was off to the right—no! it was close by, to the left—but, it was overhead and very, near—no, again! it was straight beneath me, down, away down—except that it was everywhere at one and the same moment...

And I was more afraid of that awful laughter than I had been of the many-tentacled ghouls which had risen from the limpid pool in the Lake of the Dark Blue Ooze!

It shook one so! It aroused- imaginings of beings monstrous; beings such as had never known light-rays; beings that had lived in Chaos and Old Night! And with that last thought, I knew to what realm I had arrived.

I was in that original Great Void which was, long before the shining worlds were created; beyond the Last Frontier; remote even from the scope of the Ultimate—Mercy!

I commenced speculating: "Mercy... Ultimate Mercy... and what is it, this—'Mercy'?" But try as I would, I could make nothing intelligible of that word "Mercy." Yet I had heard that word—but where, and when, and under what circumstances?... although I could not recall what it meant, nor how it was to be reached—won—nor of what use it would prove to be, once it was —was—"granted!"

No wonder that then I could not understand. Two abstractions these, which I had never rendered concrete in all my selfish, cruel existence upon earth—-the universe's training school for souls.

Not that I thought out at that moment die last part of what I have just said. That is only a recent realization. All I was capable of actually comprehending at that period, was the lost. and hopeless condition in which I found myself. One thing, however, I could not well ignore— that fearsome laughter!

My progress was slow, dreadfully so. Just that! For every step was taken in dread of the unknown; which—considering my experiences during what seemed to my wearied soul to have lasted for eons past— must necessarily be "dreadful." Why! How could I even foresee what frightful calamity the next step might precipitate me into? For that matter, I could not see anything at all! That blackness was so dense I could feel it! Save for the fact that it was dry, it was virtually as dense a medium as water, calling forth as much exertion as would swimming in order to make appreciable headway through it. Yet in reality I was not swimming, but as I have said, I was walking.

There were times when I trod on what I knew to be bones'—old, dry bones that broke, crackling, beneath my feet. There were times when I stepped on things that wriggled and squirmed, sluggishly, underfoot. There were occasions when I felt long, soft, furry somethings drifting aimless through the air; that brushed against my face and body, sickeningly. There were long spells when I seemed to be part of a multitude of invisible beings, not even so solid as was I; chill, feeble beings that did but weep and wail, low-voiced; while over, and under, and through, and all about, reverberated that shaken laughter.

And then again I would wander alone in Stygian darkness; alone save for that terrible merriment that was not mirth, nor anguish, nor sorrow, nor any other emotion known to human concept; but which yet bespoke a horror greater than all other horrors—the Horror of Great Darkness itself, as mentioned, guardedly, in the Ancient Books.

It became unbearable, totally so! Nothing could be worse! Rather than endure my fears alone another moment, I would cheerfully have welcomed Grarhorg and his hellish crew in the Blood-Red Tower of Nak-Jad as dearly beloved playmates!

The last vestige of what—borrowing an earth-word—I must perforce term "spunk" quitted me. For, after all, the self can endure only so much and thereafter it capitulates, regardless. As did I!

I opened my mouth, and all the repressed terror which was stifling me found expression in a prolonged series of howls, yells, and shrieks! Not mere whisperings and low-voiced wailings, either; but a perfect pandemonium of discordant vocalization that for the time at least, to myself, forced the terrible shaken laughter into taking second place in volume.

MY screams were replied to by screams even louder and more

horrific than were those I had emitted. A horde of bipedal

beings, apparently formed of fire, for they glowed as if

internally they were in a state of combustion, rushed at me

swifter than the swooping of hawks dropping from above.

A horde of women, naked, the most beautifully modeled figures I ever beheld; but with their classically perfect faces writhed into the most damnable expressions of malignancy imaginable. Three-headed they were, every one of them; with twisting, squirming knots and coils of slim serpents atop their heads in lieu of hair. And long jets and flickers of flame issued from their straining mouths at every screech, while from their lurid eyes streamed rays of baleful, cold, green fire! Aghast, I fled! I was not immune from terror at such a visitation as I myself had invited!

Ah well! They soon caught me, for they were long of limb and fleet of foot and much thicker than was I, and of strength prodigious. I was surrounded by them. They screamed —words, at me. They clasped me in their arms, hugging me fiercely to their burning breasts. They —kissed me! Kissed me, avidly, with lips that scorched, while they breathed searing sighs into my nostrils and between my lips. They tore me from one another's embrace, jealously, each shrieking, maniacally, that she loved me!

They pushed, clawed, and fought with one another to obtain momentary possession of me; and all the while the writhing serpents of their hair struck, and struck, and struck again at my face, and neck, and shoulders, and breast; infusing at every touch their venom into that shrinking, anguished, naked thing that was "I."

What abominable poisons entered into me, whether from serpent- stings or Furies' breaths, or from both together, I can not say; but—ere long I —I was kissing them in return; avid, panting, drunken, knowing that I was fast becoming as they were! Aware too, that I was commencing to glow; was full of flame delighting while it hurt excruciatingly—and, worst of all the many terrible things which had happened during all that period elapsing since I had received the first embrace of Hesperus, I was aware that I was fiendishly glad to be at one with them!

Likewise, I knew that I was rapidly becoming thick —almost if not entirely as thick as were they, for they were actually endowing me with their substance. And I could feel that, starting at each cheek-bone and reaching to about the back of my neck, another face was growing out of my head! Knew, surely, irrefutably, that my long, fine hair which upon earth had hung nearly to my knees, was turning—nay, had turned —into thin, venomous serpents that writhed, hissing soft wickednesses into my ears, which thrilled, joyously, at the enticing music of the sibilant sounds!

Sudden as leaves before the breath of a wind, the Flaming Women, or Furies, released me, scattering as blown leaves, into open order; and promptly, clasping hands, they formed a ring having me as its center; then, slowly at first but with ever- increasing swiftness, they swirled into a dance, amazingly graceful, yet, in its way, terrible, too; because of its utter, voluptuous abandonment.

They burst into song—the most dreadful song in all the universe. A chant of initiation and welcome into their ranks. A song of instruction revealing to me depravities and loathly delights of abandonment such as I, who had been the victim of much that is foul, could not wholly understand the meaning of.

They burst into song—the most dreadful song in all the universe.

Even now, so deeply were those burning words branded upon my innermost self, I could recall, if I would, every horrifying word as well as every alluring, nauseating sweet tone of that frightful song.

Catching fire from their fire, I swayed and swirled and swung with abandonment equaling theirs. I spun and pirouetted wildly, frenziedly, until the serpent-locks upon my heads stood out horizontally, rigid; as I postured more vilely, if that were possible, than they; and, gradually finding my voice again, I too, took up the burden of that song.

That song I will not, dare not repeat! Were I even to think it from its tempting beginning to its sinful end this earth would become polluted beyond all hope, and would become but one more of the many hells in a long chain of hells. For that song, in full, would summon hither that entire flaming horde to ravage this fair planet until the Angels of the furtherest spheres would shed tears of unavailing sorrow over its woe!

But the refrain of that chant terminated with:

"Sister, Sister, Sister, Sister,

Sister, Sister, ha-ha-hah!"

That word—"Sister!" What stirred within me? It shook

me, not at all pleasantly, nor evilly. Rather it was agonizingly,

mournfully saddening. Again! Sister!

Rose an inward vision, fleeting, lasting but a brief moment, of a pale, white face; clear blue eyes; soft, tenderly smiling mouth; a small, gracefully poised head surmounted by sunny, golden, wavy locks... Sister!

Something swelled within my burning breast until I deemed it would burst asunder from the internal pressure. I stopped swirling and ceased from participation in that song—a—a—something — rose — in my—throat—it—it sounded like— "glub!"... forgive me, but it can not be expressed in any other way!

Something, not burning but scalding, gathered in each of my six eyes and ran down my three faces! I— I—whispered:

"My little sister knows naught, in her spotless innocence, of such frightful things as do I in my sin. Thank —God—she is—spared..."

A howl of rage arose—a chorus of hate voiced from every fiery throat of that most abhorrent, malignant band.

"She weeps! Has dared whisper the name forbidden in all these realms!"

As one they hurled themselves upon me, clawing, kicking, biting, gouging, tearing, rending me apart, limb from limb, ripping me into shreds—oh anguish untellable, unthinkable—my last conscious idea...

"Oh, that I were where—naught— was—but— myself..."

I WAS nothing but Spirit; all trace of form had vanished, and

but a dingy spark was hurtling through Space! -It was so black,

so black, above, and below, and ahead of me; but yet it was not

that Great Blackness wherein I had so long sojourned. Naught but

a Spark was I, soulless, only remained to me the Spirit; the

ever-living Spark from the Eternal, Ineffable Flame. Yet still

was I conscious of identity and remembered all the torments

through which I had passed since Hesperus had bestowed me upon

Grarhorg...

Away and away ahead of me I "saw" a tiny point of light. After flight lasting for a few more ages I knew it for a—star! Back in the known universe once again! Until the skies were ablaze with myriad lights that were not—hell-lights!

On and on, past planets and suns and constellations, galaxies and nebulae and asteroids; into, through, and beyond the great solar system hurtled that Spirit-Spark that was I. Until, finally, at the furtherest limits of the universe, my Spark hovered, swooped, and settled on a little whirling globe.

It was a dull, barren, burned-out world. A world devoid of vegetation, lacking in moisture, without heat, and weak of illumination. A globe that once had been a fair planet, eons and eons ago—but which was now but gray, harsh rock, and sad white ashes, and blackened, scoriated lava-beds.

And then I noted a strange thing. At the time I did not understand how it had happened nor why it was necessary. Although now I know that no matter where in all the infinitude of Space the Spirit may be; by operation of a natural law it promptly attracts to itself—or sloughs off from itself—matter, or atoms, until it is covered by an envelope, a proper vehicle through and in which to function to its best advantage within such environment as it has attained to.

All I did know then, was that I had in some manner accumulated a tenuous body. And I did not want that form. Formless, I had little to fear save extinction of that spark which was my "Self." And that same extinction was naught to be feared by such as I, but was rather a hope; for annihilation would be a boon; a wondrous rest; a perpetual cessation of consciousness, identity, and— worst torment of all—the ending of memory.

For that faculty of "memory," abiding when all else is stripped from the sinful Spirit, constitutes the truest and most terrible torment; is, in itself, the greatest hell! A hell from which none may escape, though they flee to the outermost star; yet will such a spirit bear along its own peculiar hell, for that hell has become an integral part of the Self who evolved it. Nor is absolute extinction.

But I knew that, once I were again possessed of a definite form, tenuous though it might be, and were on a tangible world, there was no guessing what new and very terrible torments were in store for me. Doubtless, however, tortures afresh of some sort there would surely be. And I was so wearied of agonies and horrors inflicted.

"What had I done to deserve—?"

And then and there hell let loose!

Such hell as never yet had I undergone. Pictures, thrown outward from the seat of memory; taking visibility at a little distance, against the curtain of that dull air. Sounds, emanating primarily in my consciousness, impinging upon that same heavy air; echoed and thrown back again to my outward hearing; to penetrate in turn deeply into consciousness once more, laden with stinging anguish worse, far worse, than any virus instilled into my system by kiss of Flaming Furies or stroke of serpent-hair from Flaming Furies' tripled heads.

All I had thought, said, or heard, or did, or desired! Not one infinitesimal thing, however trivial, but what, with merciless exactitude, I was obliged to witness. I tried covering eyes and ears with my hands. And to no avail. Too tenuous! So thin I must, perforce, look through all attempts at self-blindness and see, and hear....

And again and again, repeated, circumstance by circumstance; episode followed by episode. On earth, from childhood to maturity—from evocation of the Dark Angel Hesperus to my present isolate estate. And repeated yet again!

"What had I done to deserve-?"

That which I had done deserved ten thousand-fold...!

And that denunciation came from no god, nor angel, nor demon, but from— within! It was the fiat of that last great judge, my Self, whose sentence, though long delayed, is inexorable! For it is very just.

The sole moisture that burned-out world had known for countless ages past burst from my eyes in ineffectual tears. Whence the moisture came I can not explain. Do I know the Universal Laws? Nay, hardly do I know myself—except as very sinful, very vile, immeasurably fallen, and, were it not for the Ultimate Mercy, as one lost beyond all hope of redemption.

Gradually the fountain of my tears dried up. No moisture left wherewith to weep. Yet the haunting, torturing fantasmagoria continued. I could no more bear it, despite my innate conviction that it was all fully merited.

I rose to my feet and realized as I rose that I was become still more thick. Had, in fact, a body nearly as solid as I had possessed while in the halls of Hesperus. A lingering trace of self-pity told me that if I walked, and walked, and walked, fatigue would eventually assert itself; and I knew that a tired consciousness receives but poorly any extraneous impressions.

Why, I thought to myself, I might even sleep! Which was a thing I'd not done since first I gave myself over to the will of Hesperus. Not in all the many hells has ever one lost spirit slept! My idea was good. I wandered until my feet ached and my limbs ached, while every part of me reveled in pain that was for once wholly physical.

Until, finally, exhausted, I laid me down by the side of a great rock, on a soft bed of ashes, and then—at last, I slept. And it was but a terrific nightmare, compounded of all the past experiences I had endured; but by no means in any sort of conceivable sequence. Rather, it was a jumble worse than the actual events. And awoke, weeping anew; awoke to the realization that I was even thicker, was as solid as though I still dwelt upon my native planet.

Like a child I sought to wipe my streaming eyes on the sleeve of my robe, and saw, to my amazement, that the tears I was shedding were of blood. And then the fantasmagoria of my sins and sufferings recommenced in merciless detail. And still those tears flowed. Tears of hopeless anguish. Tears of impotent weariness. Could I never be freed from the torment of my deeds?

"Oh, that I were back upon earth in the most hideous body ever beheld! I would be so—so—g—g— good!"

Came a flash of rose and gold more beauteous than earth's fairest dawn-rise. Before me there stood, stately, serene—

I leaped to my feet. Shrieking in terror I turned to flee.

"Stay!"

Those tones so commanding, yet so — gentle. In desperation I faced about. Although within me I was sick with a ghastly fear.

"Thou art a demon —well do I know thy sort! What torment hast thou in store for lost me? Let it begin, swiftly! Since needs must, I can endure."

Never a word that radiant one spoke, but the light shining all about It became brighter, more glorious; and the pity I read on that serene countenance—

Awe-stricken I sank to my knees: "Thou art one of the Celestials, a— Helper of the Lost? Forgive..."

"Poor, sorrow-laden child!"

I looked up into that countenance. I was well-nigh incredulous; finding it hard to realize that for such as I there was pity. But what I saw was unmistakable—and then, I did weep.

"Thou wouldst return to earth, hideous where formerly thou wert beautiful—why?"

"Can you ask?" I sobbed. "To escape—this!",—I meant that haunting fantasmagoria.

"For that reason?"

"Aye!"

The Shining Helper vanished.

AFTER prolonged grieving I knew my fault. And while I grieved,

still the fantasmagoria continued, hammering home the lesson I

was slowly commencing to assimilate. For now I knew that each

past agony had but counterbalanced some evil deed, some wicked

thought...

Yet it was a long while after I began to comprehend ere that Helper came the second time to where I sat in self-loathing inexpressible. Boldly, with the courage of the hopeless, than which is no greater desperation possible, I said:

"Earth I shall never behold again. That I know, for such were too great mercy for me. But were I only worthy, one boon alone would I ask-"

"I listen."

"Is there not some borderland wherefrom I can—mayhap— help, in some small way, some other sinful soul lest—lest—it, too-"

No comet ever shot through Space so swiftly as did that Helper, bearing me!

And how or why I knew not, but I was but a Spark once more; shining not so brightly, it is true; yet not dingy nor lurid. There was even a slightly yellowish tinge—

Above a great city of earth, we hovered finally. I could see, oh, what could I not see? Earth-life, its familiar evils, its sins, its hatreds, and its self-caused woes!

"Is not here work enough for thee?"

"Too much, too much," I wailed, knowing my own unfitness. "I can not-"

"One soul, thou didst say..."

"Let me descend—and try."

On a bed of rags in a barely furnished chamber in a decaying house located in a dirty slum, lay a woman, dying. Dwarfed, crippled, worn and wasted. Not in any wise a pleasing sight, even were she not at the last extremity. And, while I watched, I saw the vital spark fade out. Very clearly, gratefully, I realized my most glorious opportunity.

"What have I done to deserve-?"

"Naught hast thou, done—yet! But thy slain sister made intercession for her slayer; so—this!"

"And yet she knew?"

"It was because she did know that she interceded, besought mercy—for thee!"

"Oh! What have I been!"

The Helper indicated that twisted, stunted body from whence the Spark of Life had so recently departed...

"Well?"

"I am content."

"With that!"

"Aye!"

"So low..."

"Leaven rises from beneath..."

"Thou hast said!"

Death may be painful, but such birth as I then experienced was— there are no words adequately descriptive... The Helper had vanished.

Slowly that new body I had been granted, as fit instrument through which to atone, grew well again, gained strength. On a street, one day, I heard someone speaking of a "soul-doctor;" and — I — would — work. For thus far, I have sought in vain...

WHAT I said to that grieving soul I may not reveal. Yet never will I forget the look in her eyes, nor the expression on her features as she departed.

"You give me—hope," she stated simply.

But I do not think that she who was Lura Veyle sinned, suffered, and repented in vain. To believe thus were to doubt the Infinite Wisdom. Just and perfect is the working out of the Great Law.

For I believe that the world is nearing the dawn-light of a great spiritual awakening. Science, with its inexorable exactitude, will—nay, has commenced to—investigate, and is finding that many things heretofore labeled "superstition" have in reality a solid basis of fact as foundation.

The powers and forces and potentialities latent in the universe are manifold, limitless in possibility. But as there are true, good spirits dwelling within these our bodies of the flesh; so, too, are there others—evil, self-seeking, unscrupulous. Armed with intangible yet very real forces— against such, the Powers of Light, even, may not avail nor suffice to guard this world...

Yet, mayhap, the story of Lura Veyle will help to deter some such unscrupulous ones. As it may suffice to turn away, perchance—should any such read it—some erring soul who has already held, or who seeks to hold, intercourse with the Destroyers Who Tempt with Bribes...

So may it be!