RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an antique print of a lunar landscape (c. 1900)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an antique print of a lunar landscape (c. 1900)

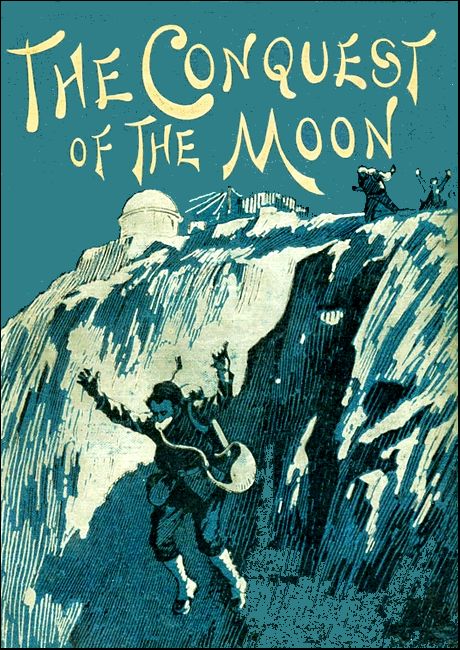

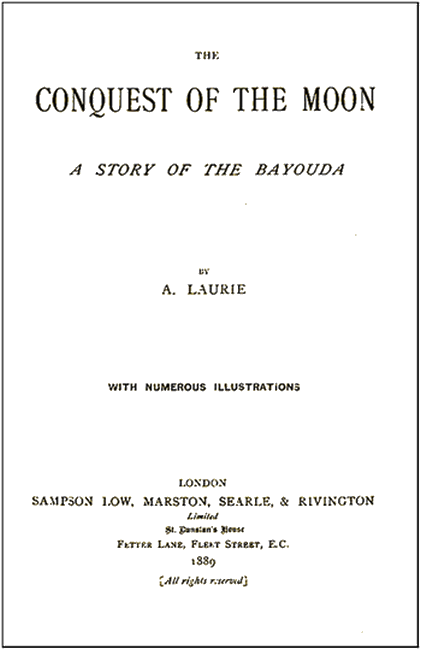

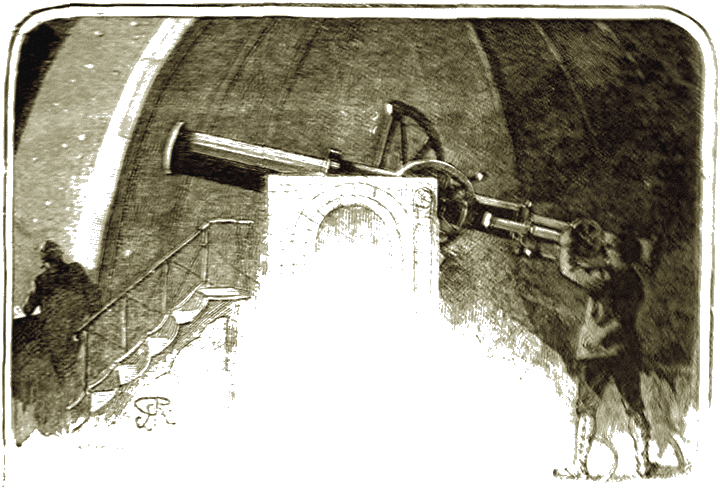

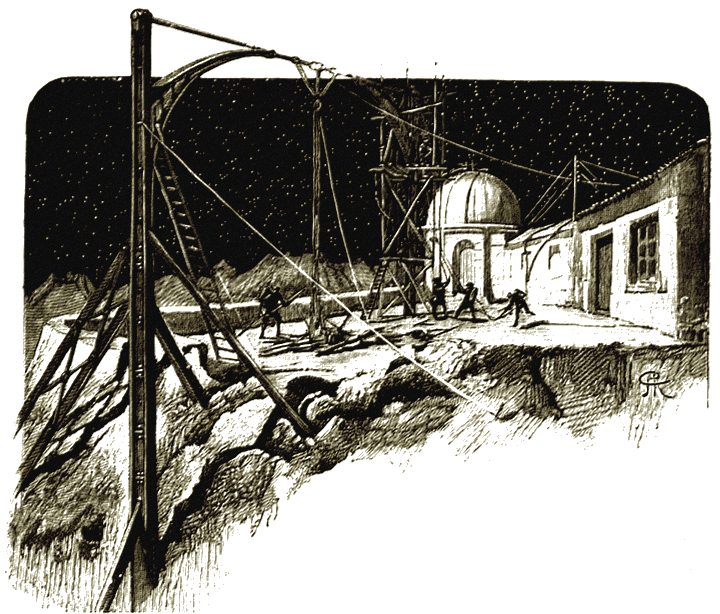

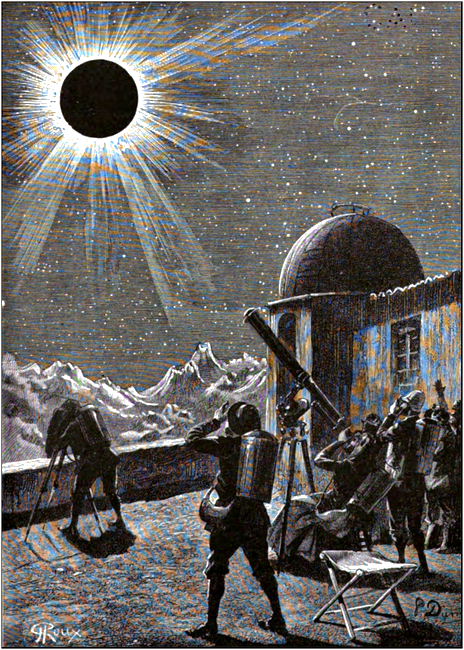

"The Conquest of the Moon,"

Sampson Low, Marston, & Co., London, 1889

"The Conquest of the Moon,"

Sampson Low, Marston, & Co., London, 1889

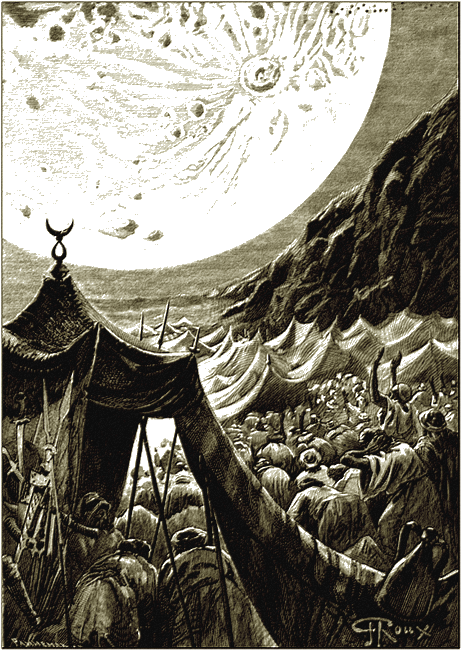

"Les Exilés de la Terre,"

J. Hetzel et Cie., Paris, 1887

"Les Exilés de la Terre,"

J. Hetzel et Cie., Paris, 1887

It is a bold thing to attempt a subject that has already attracted such writers as Cyrano, Swift, Edgar Poe, Jules Verne, and many others; but let them throw the first stone who, amid the radiance of August nights, have never been tempted by the problem to form dreams of their own. —The Author.

DINNER was over: the company had passed into the drawing-room, where large bay windows stood wide open to the motionless expanse of the Red Sea, now slowly darkening in the twilight of a lovely evening in January.

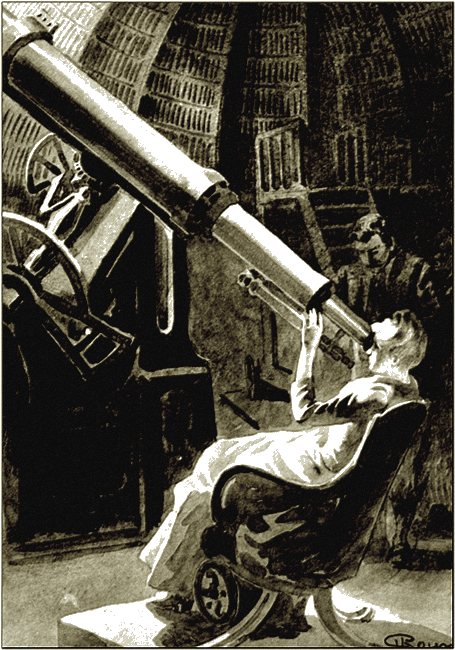

M. Kersain, the French Consul at Suakim, was entertaining that night M. Norbert Mauny, a young astronomer who had been particularly recommended to him by the Minister of Foreign Affairs. The official letter intimated that the Consul would do well to put himself at the entire disposal of M. Mauny, and to assist him as far as possible in the scientific mission that, in a confidential postscript, was stated to be of a secret nature. No one, therefore, had been asked to meet the young savant, with the exception of the lieutenant of the ship, Guyon, who in Suakim waters was in command of the Lévrier, the French despatch-boat.

The Consul was a widower. The honours of the table had been gracefully done by his daughter Gertrude as mistress of the house; and now seated at the piano, she was softly playing a nocturne of Chopin.

The weather was soft and mild. The dinner had been most joyous, its official character notwithstanding, for the quartette, albeit strangers heretofore, had conversed together with the delight and friendly recognition that is so customary among Parisians wheresoever they meet. The last stories of the Boulevards were laughed over: mutual friends were discovered at every turn. When coffee came, the talk became more intimate, and the Consul thought it time to put a question that excited his curiosity. "You have come to the Soudan on a scientific mission," said he to Norbert Mauny. "Is it indiscreet to inquire what kind of mission it is?"

"Not at all," replied the young man smiling, "and your question is only natural, Monsieur le Consul. But will you be offended if I say that I cannot gratify your legitimate I curiosity, because the business that has brought me to Africa must remain an absolute secret if possible?"

"Secret even from Captain Guyon and me?" replied M. Kersain, looking slightly astonished. "There is nothing political, I presume, about your mission? The minister's letter stated that you were an astronomer belonging to the Paris Observatory, and, if I am rightly informed, one of the most distinguished among our young savants."

"I am in point of fact an astronomer, and it is in this capacity that I have come to Suakim. There is nothing political about my mission. But it is an unknown one hitherto in this country, and for this and many other complicated reasons, I think it best not to divulge its nature, not even to the representative of France. This was the understanding with which the Minister of Foreign Affairs recommended me to you. And, moreover, not only is my mission not political; it is purely of a private nature. The expenses are borne by English capitalists. The colleagues who came with me in the Dover Castle are none of them French. We have come to Africa to make an ingenious experiment. The sole favour I have asked from our Government is its moral support in case of need. This was promised me by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who assured me also that I should always find him ready to assist me in the task I have undertaken."

Whilst Norbert Mauny gave these explanations, the French Consul and the naval lieutenant observed him narrowly.

He was a tall, slender, dark young man of about twenty-six or thirty. Refined broad brow, clear bright eyes, aquiline nose surmounting a well-defined mouth, firmly moulded chin; one and all were instinct with frank bravery and goodness. He wore his evening black coat with the ease of good breeding mingled with the careless nonchalance usual in men of action. His voice was deep and melodious; speech short, and to the point. Serious without pedantry, a hidden gaiety peeping out in every deed and look, he was a fine type of a Frenchman—one might say of a great Frenchman, so evident and undeniable was the superiority of his nature.

Satisfied with the result of his scrutiny, the Consul courteously hastened to change the conversation.

M. Kersain was a distinguished diplomatist of the old school, who would have attained to the greatest eminence in his profession had he not been kept by the shores of the Red Sea by his unfortunate passion for Nubian antiquities and the need of a warm climate for the health of his daughter. Gertrude was twenty years of age. Frail and bending like a reed, with a milk-white complexion, and a profusion of magnificent golden hair that almost weighed her down, it was easy to see that her life hung upon a thread. Her mother, indeed, had died young of consumption, to the life-long grief of M. Kersain; and he was in constant dread lest the daughter might develop the same too well-known symptoms of decay. From time to time a slight cough shook the lovely but delicate frame, whilst an alarming flush coloured the white cheek. Gertrude paid no attention to these signs; she was gentle and charming, the idol of all who approached her, and she was full of hope, as is so often the case with these perfect beings, "too pure for this world."

But her father could not be blind to the alarming symptoms; and the doctors were on the alert to warn him that a less dry climate might prove fatal to Gertrude. For the sake of his daughter, therefore, he had remained at Suakim, which had been the scene of his début in the consular career. Every moment that he could spare was devoted to her, and to watch over the health of his child was the sole aim of his life. Her happiness was his constant thought, and he could refuse her nothing. Unselfish and modest by nature, the sweet and well-trained girl had but few caprices, but these were gratified without hesitation by her adoring father. The reticence of the young astronomer had, in despite of himself and his host, lent an air of restraint to the conversation. It was, therefore, a relief to all when a fresh guest appeared, in the person of a florid, sprightly man of about fifty—Dr. Briet, the uncle of Mademoiselle Kersain, who had travelled to Suakim on purpose to take care of the health of his niece. Not an evening passed without his appearance at the Consulate, and his entry now was the signal for a joyous welcome.

"Good evening, uncle!" cried Gertrude, flying into his arms.

"Allow me, dear docteur, to present you to our compatriot, M. Norbert Mauny ... M. le docteur Briet," added the Consul, introducing the two men to each other.

They bowed, and the jovial doctor said simply at once, and with great cordiality:

"'I knew of the arrival of M. Mauny, and of course he was already known to me by repute. No one can read the Records of the Academy of Science without learning that M. Norbert Mauny has done magnificent work with the Spectrum analysis, and that he discovered two telescopic planets, Priscilla and—the deuce do you call the other one?"

"She is not yet christened, except with a number," laughingly replied the young astronomer. "So many planets are discovered in these days," added he modestly, "that it is difficult to find names for them all."

"Call it Gertrudia," said Captain Guyon, looking at Mademoiselle Kersain.

"Oh! Captain! You don't mean that!" exclaimed Gertrude.

"But, on the contrary, it is an excellent idea," replied Norbert; "and I shall be only too delighted to profit by it, if your father and yourself will give me permission. A definite name is much wanted by these little stars, to distinguish them clearly from the others. Gertrudia will be perfection. I adopt Gertrudia!"

"Oh, papa, what fun! I shall have a star to myself!" exclaimed the enchanted child. "But you will point it out to me, will you not, sir, that I may know it when I see it?"

"Most willingly... when it is visible!...In seven or eight months' time, if the weather allows."

"One cannot see it every night, then?" asked Gertrude, slightly disappointed.

"Oh! no. If so, it would long ago have been discovered and named. But we have found out enough about its habits now not to let it go by without an au revoir."

"It is not everyone who can offer such a bouquet as that to a lady," said the doctor. "And, doubtless," he continued, all unwitting of indiscretion, "you are engaged on an astronomical mission?"

"Not precisely!" replied Norbert, who could not help laughing this time. "I see," he added, on perceiving the astonishment of the doctor, "that it is not easy to keep a secret, especially when one is resolved to tell no lies in its defence. I might have said that I wanted the clear sky of the Soudan for the purpose of taking fresh interplanetary observations. I prefer to tell you a part of the truth. I have come here to study the ways and means of a somewhat chimerical undertaking, or, at least, such it will appear in the eyes of many when they hear the programme. Now, unfortunately, at the University I have already got the character of being a hare-brained individual. I am therefore condemned necessarily to silence about my plan until it succeeds—under pain of being looked upon and perhaps treated as a lunatic. In these circumstances you will understand my having solemnly resolved to say nothing about it to anyone. If I succeed everyone will see it! If not, there is nothing to gain by being laughed at, and having perhaps fresh obstacles added to those that already confront me. The first step will be the establishment of a scientific station on the tableland of Tehbali, in the desert of Bayouda."

"A scientific station in the desert of Bayouda!" cried the doctor. "What a time to choose for such a thing! Think you, forsooth, that our friends the Soudanese will let you settle it all at your ease?. I wouldn't give a hundred pence for the skin of any European who tried even to reach the Upper Nile. And you think to cross it, and get to the Darfour frontier?. Allow me to tell you that this is simple folly."

"Did I not say that you would call me a lunatic at the first word!" coldly replied Norbert. "You are witnesses, all of you, that I was right!"

"I' faith, I'll not retract!" answered Doter Briet. "To try and penetrate to the heart of the Soudan is quite as hazardous as it would be to go among the Touaregs. Have you forgotten the fate of all who have ventured south of Tripoli—Dournaux-Dupéré in 1874, my brave, good friend Colonel Flatters in 1881, Captain Masson, Captain Dianons, Docteur Guiard, the engineers Roche, Beringer, and so many before their time?"

"I have forgotten nothing," said the young astronomer, with perfect sang froid. "But the geological and sidereal conditions that I need are only to be found together in the desert of Bayouda, on the table-land of Tehbali. I must seek them there."

"Beware lest you find something quite different!" exclaimed the Consul significantly. "Believe an old African—there is only one way now to go to Darfour: with a regiment of Algerian sharpshooters and a convoy of three thousand camels."

"I see myself, indeed, at the head of so many sharpshooters and camels!" gaily answered the young savant. "I have done my twenty-eight days twice, just like any one else, but I have never got beyond the grade of corporal, nor commanded more than four men. I must content myself with my servant Virgil, who happens to be an old African sharpshooter, and with a good guide, if I can find him At all events, the Soudanese will see that I come in friendly guise."

"A giaour? Not they! Go and ask them what they think about it, and then come and tell them, if you have a tongue left to speak with!"

"You are certainly bent upon making me think that I am going to embark on something superhuman. Are these Soudanese, then, such fearfully wicked people?"

"They have no intention of letting any European come out alive from among them-that is all I can tell you. And there are two or three million of them at the least perfectly disciplined, blindly obedient to their chiefs, armed to the teeth, with immense resources at their disposal. Have you never heard of the Mahdi?"

"The Mahdi?. That kind of Mussulman illuminati, who organized a revolt on the Bahr-el-Ghazel, two or three hundred leagues off?"

"Just so. Well, Monsieur Mauny, this Mahdi, if we do not take care, will eat us all before the year is out. He will drive us from Suakim, from Khartoum, and from Assouan. Perhaps he will drive us out of Cairo, and even Alexandria!"

"But have not troops been sent from Egypt to oppose him?"

"He will make but a mouthful of them, if he does not even force them to serve under him. I know what I am talking about, I tell you!. We are beginning a sacred war. In six months, or at most a year, the Mahdi will be at Khartoum!"

"A year; that is a long time! Perhaps I shall not want so long to realize my project."

The docteur contented himself with throwing up his arms to heaven.

"So," said the lieutenant of the ship to Norbert Mauny, "you persist in running into the lion's mouth?"

"Yes, captain."

"Well! you are plucky for an astronomer!"

Everyone had listened to this discussion with great interest, but Mademoiselle Kersain more than all. Whilst Norbert Mauny described his plan, and Docteur Briet set forth his objections, she remained silent, her large eyes looking from one to the other; but every now and then she grew pale with the thought of the dangers to which the young savant was going to expose himself, whilst she was full of admiration for the tranquil courage with which he accepted the programme. Her expressive and sensitive countenance showed so visibly the emotions that agitated her, that her father, feeling anxious, made a sign to the docteur to change the conversation. He rang at the same time for tea, which was brought by a little Arab servant, and dispensed as usual by Gertrude. Drawing Norbert Mauny aside, the Consul led him out on the terrace, where, taking him by the arm, he said:

"Do you know I have serious scruples about lending my countenance to such an enterprise as yours?"

"It is settled then, that you go?"

"What am I to do?" replied the young savant, very simply. "I am not alone! Considerable capital is embarked in the undertaking. A superintending committee accompany me on the Dover Castle which brought us here with all our requisites. And I repeat, what I am about to undertake is only possible in the Soudan. Besides the fact that, to my certain knowledge, the indispensable physical conditions are found together only there, the very state of existing anarchy is one of the reasons that have confirmed me; for this frees us from tiresome negotiations and authorizations that we should perhaps never have got from an established Government. We shall work in a region that is dependent on no one, since all nominal authority even is at an end. These are precious advantages, and it would be folly not to profit by them."

"But how do you propose to overcome the notorious and implacable hostility of Arab tribes who will bar your passage?"

"In the simplest way in the world. By converting them into friendly allies.

"And you expect to succeed in so doing?"

"I hope so."

"I cannot agree with your sanguine expectations; but if you are really determined, you must at least take all possible precautions. We have here at Suakim a man who may be useful to you from his knowledge of the customs and men of the country. His name is Mabrouki-Speke. He is the old negro guide who accompanied successively Burton, Speke, Livingstone, and Gordon. Shall I put you into communication with him?"

"By all means. I am only too glad, of course, to increase my chances of success. . It will take some time to organize the expedition, on account of the heaviness of the baggage and requisite material. Doubtless I shall often have to come to you for help before I leave Suakim."

"Make all possible use of me," replied the Consul, with a cordial grip of the hand, as they returned to the drawing-room.

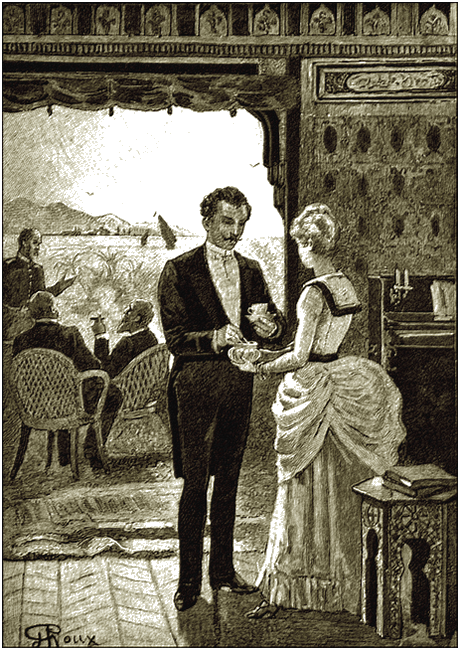

Gertrude came forward at once with a cup of tea, which she offered Norbert.

"It is settled, then, that you go?" she asked, as she handed him a piece of sugar.

"It is settled, then, that you go?"

The ingenuous expression of sadness on her countenance went to the heart of the young man, and he felt, to his surprise, grieved, as if about to leave a well-loved sister or one of childhood's friends. Suppressing the sigh that rose to his lips, he smiled in reply:

"I go, but not directly. The preparations will take two or three weeks, and so I do not bid adieu yet to the Consulate of France."

Gertrude said nothing. Her eyes were filled with tears.

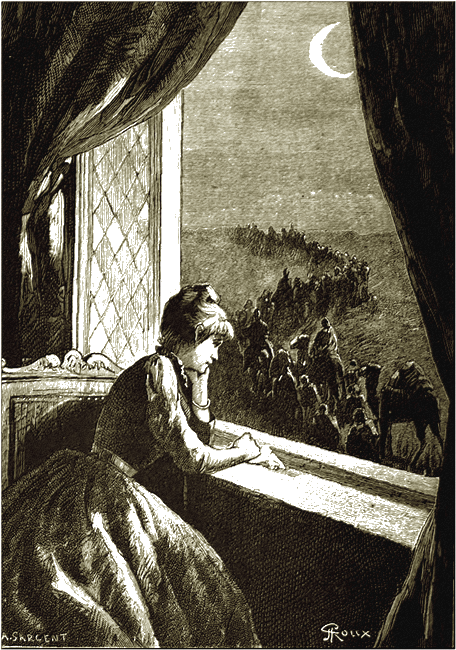

She bowed slightly, and stepped on to the terrace to gaze on the myriad stars that irradiated the heavens.

"I LIKE M. Mauny very much, certainly," said the French Consul next morning, as he took his seat opposite his daughter at the breakfast-table. "The doctor declares that he is a most distinguished savant. He has good manners; besides, he is evidently energetic, and in addition, as a set-off, he is a good-looking young fellow."

"In a word," answered Gertrude, with a slightly embarrassed laugh, "he has quite made a conquest of you, dear father, and perhaps," she continued, with a touch of malice, "he will be more pleased than surprised when he knows it."

"That is the way with all young girls!" exclaimed the Consul. "They are always ready to pick out the faults in their sincerest admirers. For I could see that he was smitten with you. But, of course," he continued, good-humouredly pretending to take her at her word, "if you do not like him, it is as well that I should know it at once. He has just sent me a line inviting us both to go over the Dover Castle this evening; but I can go alone, and make some excuse for you!"

"An excuse for not going over the Dover Castle? You are laughing at me, dear papa," she answered quickly. "Rather do I want an excuse to see it? I am most grateful to M. Mauny for inviting me. And, to tell the truth, I meant to give him a hint last night at dinner when I spoke about the tapering masts that have been a three days' wonder to the world of Suakim; but I feared it was but a waste of breath, and that he would never descend from the transcendental heights of astronomy to notice, still less to gratify, the curiosity of such an insignificant individual as myself."

"You were mistaken, you see," said M. Kersain. "Well then, it is settled. Be ready to go out at sunset, about five o'clock, and a boat shall be waiting at the quay."

So saying, the Consul buried his head in the newspapers, which he generally read during breakfast. Gertrude left the room a few minutes afterwards to make her preparations, chatting the while with her little Arab maid Fatima. She was waiting for her father, gloves buttoned, at least an hour before he came to fetch her.

Suakim is by no means a large town, and in three minutes the father and daughter reached the quay. They saw Norbert Mauny at once. He seemed to be awaiting them in company with a stranger, and he now came up with great eagerness.

"We scarcely dared to hope that Mademoiselle Kersain would do us the favour of accompanying you," he said, pressing both the hands held out to him. "Let me introduce you to my friend, Sir Bucephalus Coghill; he is a member of our expedition, and, with myself, will have much pleasure in doing the honours of the Dover Castle."

Sir Bucephalus Coghill, Baronet, was a tall, slender, elegant young man of twenty-six years of age. His florid complexion bore evidence to his Anglo-Saxon nationality, but he appeared fitted rather for the hunting-field than for a scientific expedition. He had, however, been a great traveller, and he was soon engaged in lively conversation with the Consul and his daughter.

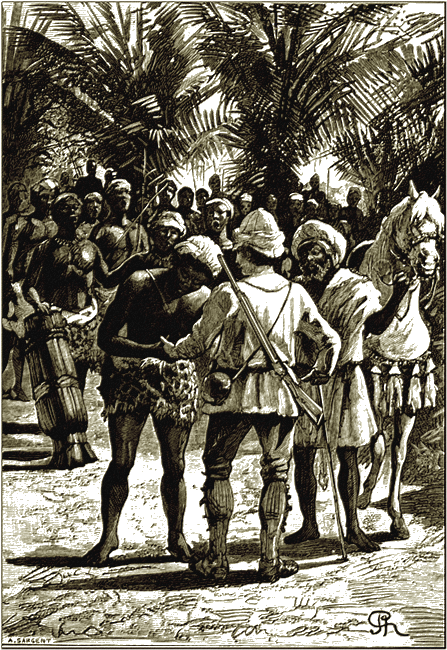

Norbert, though, was quite taken up with what was passing at the distance of a few paces in a group composed of several Arabs, three Europeans, and an old negro habited in white linen acting as interpreter to the rest.

"It is Mabrouki Speke! You have got hold of him already," said M. Kersain, observing the direction in which the young astronomer was looking.

"Yes, he is trying to negotiate on our account with some camel-drivers, but he does not seem to be making much way with them."

Only in the East, indeed, would it be possible to hear such a medley of cries, groans, and curses as proceeded from the aforesaid group, conspicuous among whom was a great bearded, hook-nosed, turbaned fellow, who vowed he could not accept a centime less, swearing by Allah and the infernal powers that by the head of his father he would be reduced to die of hunger! But all this eloquence had little effect on the Europeans. One of them now left the group, and, coming up to Norbert, said abruptly, with a very Teutonic accent:

"These dogs ask ten piastres a camel, and will not give in."

"Allow me to introduce you to M. Ignaz Vogel, one of the commissioners of our expedition," said Norbert Mauny, in a cold tone.

The guide was not, indeed, very presentable—squinting, under-sized, covered with rings and trinkets, his miserable little body clothed in a large-checked costume, with the tiniest of hats set on a great shock head of hair, his hybrid language, accompanied with a sinister smile, made up a whole that filled one with disgust and suspicion.

"Permit me to leave you for a minute for an important matter," said Norbert to his guests.

They bowed assent.

"Ten piastres?" he resumed in an aside to Vogel. "And how many camels?"

"Twenty-five, at ten piastres a head. I think it exorbitant."

"No. It is nothing, on the contrary. Have you considered the distance they will have to traverse? Would that we had five hundred camels at that price instead of twenty-five. Engage them at once, but be careful not to let the men see that we have such need of them."

"Very well," replied the other; "I will manage it."

Then, turning to the Consul and his daughter, he added: "Monsieur and mademoiselle, I will not say good-bye, but au revoir. I shall have the pleasure of seeing you presently on board." So saying, with a parting salute in the shape of a scrape of the foot, he went off to his camels.

"A strange associate, truly, for Monsieur Mauny and that correct young Englishman," observed M. Kersain and Gertrude to each other.

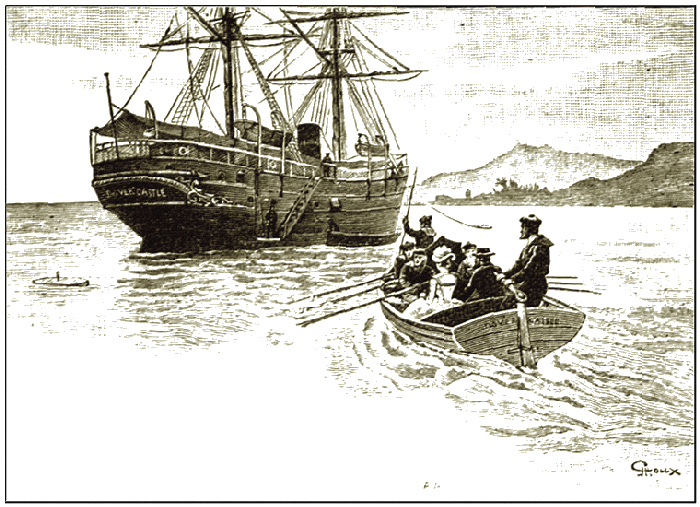

But the pleasure of embarking in a canoe soon effaced the disagreeable image of Ignaz Vogel. Six sturdy sailors, rowing well together, brought them in two minutes to the stairs of the Dover Castle, whose captain awaited them with a courteous greeting.

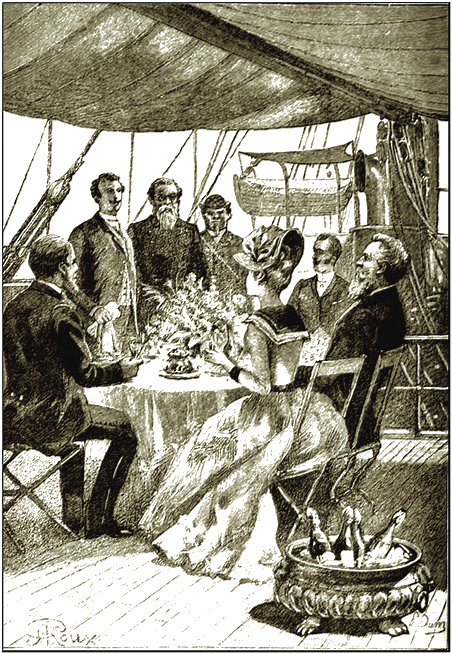

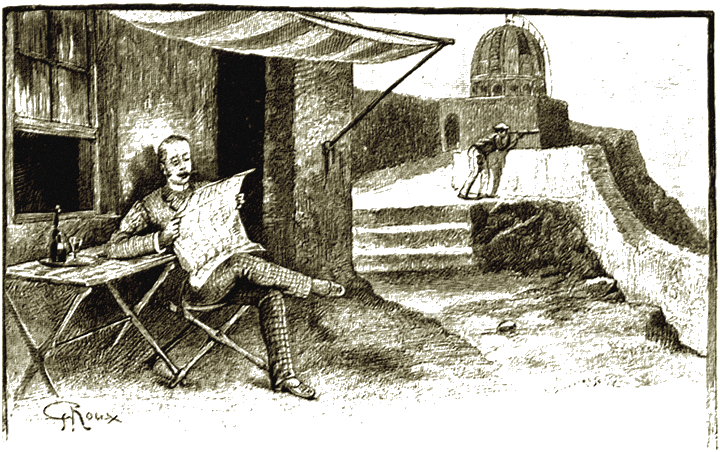

They duly admired in extenso and in detail the cleanliness, discipline, and good order that reigned everywhere, and asked, as is usual, a thousand explanations that were all forgotten the next minute. They were told the name of every little bit of rope, and initiated into all the customary rites of the occasion. At length, when everything had been lauded to the skies, came the chief rite of all, the luncheon, which the two young men had ordered to be laid out aft under an awning.

The table was covered with fruit, ices, and pastry, embedded in flowers; and, to the great surprise of M. Kersain and his daughter, there was a profusion of superb plate and rare china. The Consul could not refrain from complimenting M. Norbert.

"All these splendours are due to Sir Bucephalus, and not to me," laughingly replied the young savant. "I am not in the habit, I assure you, of always eating off silver plate or drinking tea out of porcelain cups; but the three other commissioners and myself take our meals with Sir Bucephalus in common, and this is the Asiatic luxury he shares with us."

"No luxury could be too great to honour our present Guests," said Sir Bucephalus. "But I must beg them to believe that I could very well dispense with it, only my domestic tyrant will not allow me to have my own way."

"Sir Bucephalus," explained Norbert, "possesses a model valet, who has grown up in the shadow of the ancestral manor, and would deem it a crime not to regulate his master's life in accordance with the laws of etiquette."

"He knows very well, at least, how to decorate a table," said Gertrude; "these pomegranate blossoms have a charming effect."

Tyrrell Smith, the valet in question, coming up at this juncture with the champagne, the conversation was changed, and before very long joyous peals of laughter resounded over the calm waters of the Red Sea.

In the midst of their cordiality Ignaz Vogel made his appearance, escorted by the two individuals they had seen with him on the quay. Norbert at once introduced them as—

"M. Peter Gryphins ... Costerus Wagner, commissioners of the expedition."

"Mr. Peter Gryphins ... Mr. Costerus Wagner."

The three new-comers seated themselves at table without ceremony.

"More commissioners," thought Gertrude. "They look rather like servants out for a holiday. M. Mauny has certainly been unfortunate in his choice of commissioners."

"Have you succeeded in settling your business without being outrageously cheated by those cunning rascals?" asked the consul. He was by no means fascinated by the oddities whom he was addressing, but he tried to be amiable out of compliment to his host.

"Damn it!" elegantly replied Peter Gryphins, who might have come straight from a stable, judging from his scanty waistcoat, his gaitered legs, paper collar, and bookmaker's visage. "We have scarcely nobbled thirty-five camels, instead of the fifty that were promised us."

"These Arabs make a boast of fooling us," added Ignaz Vogel. "I am very doubtful whether we shall succeed in getting the necessary means of transport."

"Do you need, then, such an enormous number of men and beasts?" asked the Consul.

"We want at least eight hundred camels," replied Norbert, "and a proportionate number of guides. It is a question of disembarking all our material and conveying it to the table-land of Tehbali—that is to say, about eight hundred leagues off, across the desert. It is no easy matter, I know. But the thing will be feasible if only the bad faith of these people does not raise insurmountable obstacles."

"Why did you not tell me sooner of your difficulties?" cried the Consul. "I could have saved you many useless comings and goings. You must know that in any great undertaking there is nothing to be done throughout the Suakim territory, unless you treat directly with the real lord of the land?"

"And who is he?" asked Norbert.

"He is a local 'saint,' Sidi-Ben-Kamsa, Mogaddem of Rhadameh, and head of the powerful tribe of the Cherofas. Not only will no camels be forthcoming without his permission, but if you had had the imprudence to bring any from Egypt or Syria, you would assuredly have been attacked and robbed in the desert."

"Are you speaking seriously?" exclaimed the young astronomer.

"Most seriously. You must indubitably win over this high personage to your enterprise, or give it up."

"And how can a humble wretch like me manage to gain the protection of a holy mogaddem? It seems more difficult than to get hold of those slippery camels," said Norbert.

"Good. Have you forgotten that a golden key will open many doors?"

"How? Would the saint be amenable to mercenary sentiments?"

"Between ourselves, I believe he knows no other. Sidi-Ben-Kamsa is one of the most singular phenomena of this country. It is to him that recourse must be had for everything and on every occasion. He gives audience every morning at sunrise, like the Commander of the Faithful in the' Thousand and One Nights.' His receptions are much sought after, and it would be supremely inconvenient to go there empty-handed."

"No matter," gaily rejoined Norbert. "We are quite prepared to go with full hands. Is it far from here?"

"About two days', or rather two nights', march."

"We should not do ill to go and visit this holy personage tomorrow. What say you, Coghill?"

"I say that the excursion would be a real pleasure party if M. and Mademoiselle Kersain will come, too," answered the baronet stolidly.

"Mademoiselle Kersain!" "My daughter!" simultaneously cried Norbert and the Consul.

"Oh, a thousand thanks, monsieur!" exclaimed Gertrude, quite delighted. "You could not have proposed anything that would please me better. If my father will only say 'Yes,' I undertake to show you that a woman can travel in the desert without being in anyone's way. Oh! dear papa, do consent! You know that for a long while I have been dying to see this famous mogaddem. I promise to keep well, darling papa, and not to tire myself."

"Very well, very well," smilingly answered her father, who had no wish to refuse his daughter the promised pleasure, and was only fearful of intruding. "But are you quite sure that we shall not be in the way, Monsieur Mallny?"

"Oh! Consul, has not Sir Bucephalus told you that if you come the journey will be turned into a party of pleasure? But it will be fearfully dull if we are not to have your company after having hoped for it."

"It is very gracious of you to make me so welcome. It is settled then. For a long while past my brother-in-law, Doctor Briet, has been urging us to make this strange excursion with him. He shall join us if you consent, and I make no doubt but that he will be ready to start as soon as you like."

The baronet and Norbert bowed their assent. As to the three "commissioners," no one noticed their presence, or seemed to consider them as forming part of the expedition. But the one whom Norbert had called Costerus Wagner, and who, from his large flapping hat and long trailing yellow hair, might very well pose as a savant at large, suddenly said:

"Do you think it necessary for Vogel, Gryphins, and myself to make this journey?"

"By no means," answered Norbert, most significantly; "and if you prefer to remain here and superintend the landing of the material—"

"The landing is the captain's affair," interrupted Peter Gryphins, in a sullen tone. "And the statutes are precise; we ought not to leave you."

"The statutes having been drawn up at my suggestion, there is no need to quote them to me," replied Norbert, with an irony in his voice that escaped neither the Consul nor the "commissioners." The latter made a visible grimace.

"I think our best plan is to entrust Mabrouki Speke with all the preparations," said Norbert to the Consul; "and if it is agreeable to you we might start to-morrow."

"To-morrow night," replied M. Kersain; "for, as you doubtless know, one can travel only at night and morning in this climate. Shall we meet at six o'clock at the Consulate?"

"Yes, at six o'clock."

"How pleased I am!" cried Gertrude, delighted.

"Thank you, dear father! Thanks a thousand times, messieurs! Sir Bucephalus, it was you who proposed that I should be of the party. I thank you, then, more especially!"

Norbert had some trouble to dissemble his pique at this expression of gratitude, natural and unaffected though it was.

"There is that fellow, Coghill," he thought, "already on the best of terms with Mademoiselle Kersain! I shall never know how to get on with her; I seem lacking in the art or gift, whichever it is. Perhaps I have been so long taken up with telescopes that I have forgotten how to talk to ladies."

M. Kersain perceived his abstracted air, and rose to take leave of his hosts, who, however, insisted on accompanying him and his daughter to the very door of the Consulate.

Returning to the Dover Castle, they met Mabrouki Speke on the quay, and gave him their orders. The old guide knew his work. He listened attentively to their instructions, and promised that all should be ready for the start at the appointed hour on the morrow.

THE route taken by the little caravan led by Mabrouki Speke lies first due westward on the road to Berber, then veers to the south towards the oasis of Rhadameh. After leaving Suakim the path leads over a mountainous and broken country. But after some hours' march the landscape changes to sterile downs stretching away out of sight to the horizon. The road is simply a pathway traced by the passage of caravans, and the simoons would cover it over with sand were it not for the sun-dried parchment-like skeletons of horses or camels to be met with here and there, and serving as landmarks to show where the path was once. This is the aspect of the Nubian desert between the Red Sea and the Nile, extending over about 110 leagues. It differs, as will be seen, from the Sahara, properly so-called, but perhaps it is even more lonely, more monotonous and desolate.

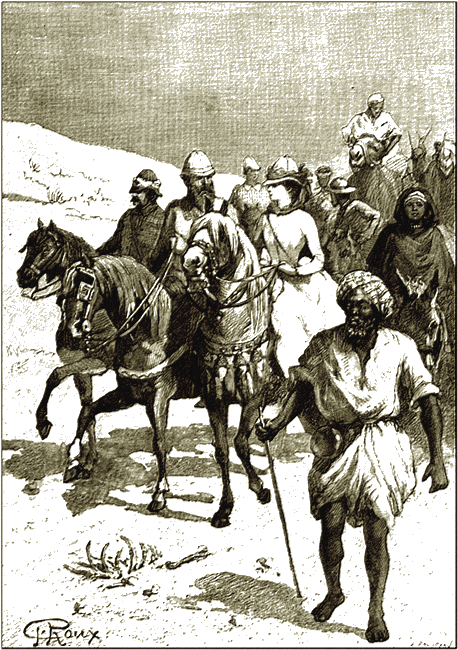

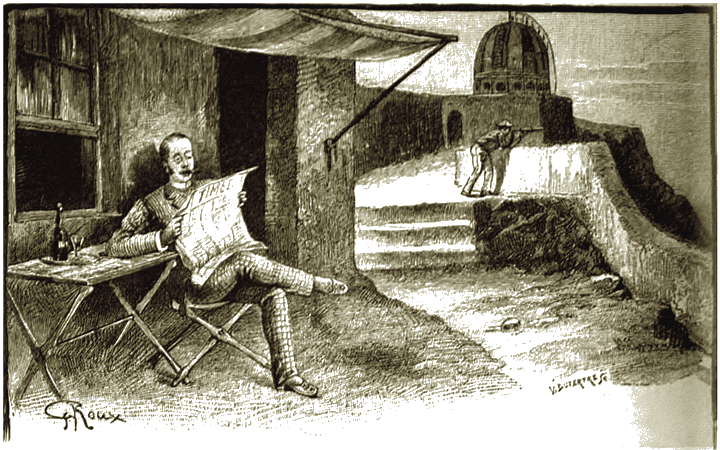

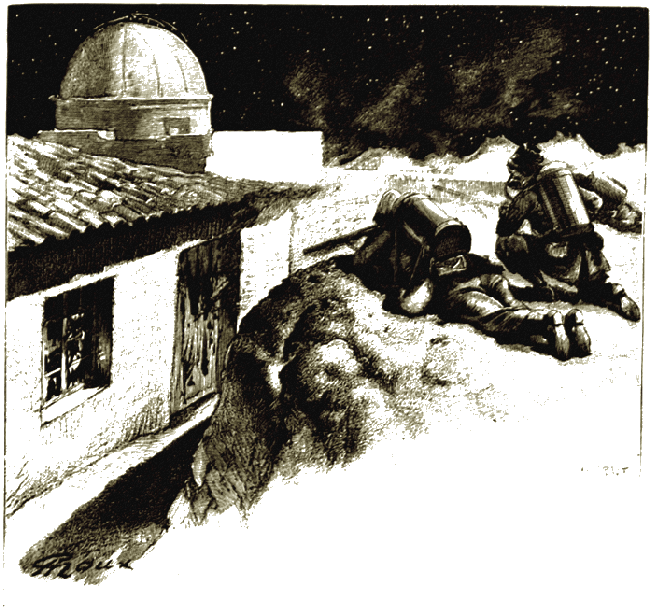

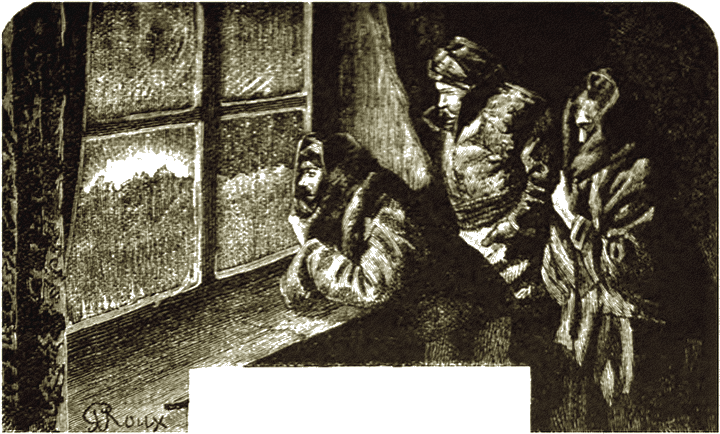

After due deliberation the three commissioners, Costerus Wagner, Ignaz Vogel, and Peter Gryphins, had, to the relief of Norbert, decided on remaining in Suakim. He, however, could not help suspecting some sinister design to lie at the root of their decision. The expedition consisted therefore only of M. Kersain, his daughter, Doctor Briet, the baronet, and Norbert. They were all on horseback, as also were the attendants. Gertrude had donned a long robe of white linen, and wore on her head a canvas helmet and blue veil that became her admirably. Her little servant, Fatima, was in Arab costume. They headed the cavalcade, escorted by the four cavaliers, and were alternately led or followed by Mabrouki Speke.

Gertude a canvas helmet and blue veil.

The rear-guard was highly picturesque. It consisted of seven camels, laden with provisions, drinking-water, and camping necessaries.

Five Arab drivers, perched on camel backs between the water-skins and the bales, showed a glimpse of bronzed faces in the midst of snowy-flowing draperies. Then came two individuals of highly different aspect: Tyrrell Smith, the valet of Sir Bucephalus, philosophically enduring the hard jerky trot of his camel, and a great jolly dark-skinned fellow, clothed in grey linen, with an Algerian chechiâ on his head, who was none other than Virgil, the soldier-servant of M. Mauny.

We term him a soldier-servant because he so termed himself whenever he was questioned on the point; and also because, until now, he had only served under commissioned French officers. He was an Algerian sharpshooter. The brother of M. Mauny, himself a captain in the African army, had, on learning the departure of the latter for the Soudan, hastened to secure for him the services of Virgil, who would, as he knew, prove to be a most valuable help and companion. The good fellow made no pretensions indeed to the dignity of valet, cook, coachman, or groom. A stranger to the most elementary principles of etiquette, and even to the usages of civilized life, he was nothing but a soldier's servant—a most unique specimen though; for he was full of resources, and was indeed a Jack-of-all-trades.

Just now he was vastly amused at the doleful expression on the clean-shaven countenance of Tyrrell.

"Well, friend!" he said, tapping him on the shoulder as their camels went along, cheek by jowl; "say: wouldn't you prefer a first-class carriage?"

Such familiarity was not at all to the taste of M. Tyrrell Smith, who, moreover, had but an imperfect knowledge of French. He contented himself therefore with making a disdainful grimace, intended to express the immeasurable distance that in his mind existed between the butler of a baronet and the servant of a simple astronomer.

But Virgil was not going to be beaten.

He did not even notice the grand airs of Tyrrell, and if he had, he was too simple-minded to have understood them. Taking off the artistically-carved gourd that hung round his neck by a red cord, he courteously offered it to Tyrrell, saying with abroad grin:

"Taste that, comrade, and tell me what you think of it!" This act of politeness touched Tyrrell Smith. He had a special weakness for French cognac, and without waiting to be pressed, he put the neck of the gourd to his thin lips and took a good long draught. This sacrifice to Bacchus unloosed his tongue, and enabled it once more to speak French.

"A queulle heure... nous... arriver... hotel?" he asked, with a visible attempt at graciousness.

"At the hotel!" exclaimed Virgil. "You don't mean to say that you expect hotels to spring up in the Nubian desert like mushrooms? We shall probably halt about midnight for three or four hours' rest, and after a slight snack, start off again."

"But... the gentlemen... and the ladies?" said Tyrrell.

"Well, the gentleman and the ladies will, like us, take a nap under their rugs, and after eating a morsel, will get into the saddle again."

"Je disapprouvais... hautement... pour... Sir Bucephalus!"

Emotion would not let him proceed further; his professional gorge rose at the idea of his master being subjected to such a rough-and-ready style of living, and he was seized with an attack of ill-humour that lasted until at midnight a halt was called at the place fixed by Mabrouki, the meeting of the routes to Rhadameh and Berber.

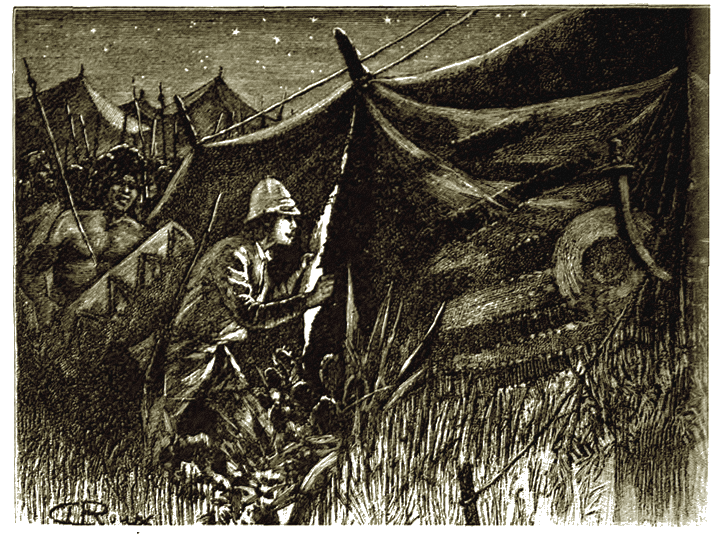

They had all bravely weathered this first stage. In the twinkling of an eye, the Arab servants had lighted torches, posted picquets, pitched tents, and spread out the pro-visions on carpets, around which the hungry travellers seated themselves with appetites sharpened by six hours' travelling.

Tyrrell Smith noted with dismay the total absence of plate. He solemnly entered his protest against such a violation of sacred etiquette by standing bolt upright all supper-time, motionless and sullen, with white gloves and cravat, behind his master.

At the end of the collation, Gertrude and Fatima retired into one of the tents, whilst the three Frenchmen and the baronet took the other; and all gave themselves up to repose. It did not last long. They had not slept an hour even, before they were awakened by the sound of voices and the stamping of feet. Fatima crept out of the tent to reconnoitre.

"It is a Berber tribe going to the Mogaddem of Rhadameh. There are a hundred at least, and all on donkeys."

"I must see them!" exclaimed Gertrude, hastening to rise and join her father and the other travellers, who were already on the qui-vive.

The Berbers were, in fact, all mounted on diminutive donkeys, which they led with only a halter. They had women with them, and about a dozen children, who were absolutely naked, and whose first thought at the sight of a pool of water near the encampment was to rush into it and splash about.

The new comers soon gave evidence that they also meant to pitch their camp. But they were not long about it, and soon absolute silence once more reigned in the desert.

Suddenly an unexpected tumult aroused the weary travellers.

"What is that?" exclaimed Gertrude, not a little alarmed.

"Only a donkey braying," replied Fatima.

It was indeed a young ass testifying its delight in the enjoyment of fresh water and food, in much deeper and more prolonged notes than are emitted by its European brethren. The elegant solo lasted quite three minutes.

"At last!" exclaimed M. Kersain, when it had finished. "It is time!"

But another ass took up the song in a higher key. "Good heavens!" groaned Fatima, "now they are all going to tune up!"

"What do you mean?"

"Oh, mistress, I know them well. When one begins, they all follow in succession. There are more than sixty of them. They will go on for at least three hours."

"Are you sure?"

"You will hear! I know them well," replied Fatima piteously.

"Then we must not expect to get any sleep?"

"No, indeed!"

"Well, that is pleasant news!"

The same sort of colloquy took place probably in the other tents, judging from the angry voices proceeding therefrom. And all the while the monstrous serenade continued, being taken up by a third, a fourth, up to the fiftieth ass in succession. Tyrrell Smith could stand it no longer, "Will you be quiet, you horrid beasts, who will not even let a gentleman sleep?" Seizing a stick dose at hand, he rushed to the asses and began beating them as hard as he could.

They all at once set up a perfect chorus of frenzied braying, which so enraged Tyrrell Smith that, losing all control over himself, he laid about him more violently that ever, regardless of the vociferations and screams of the indignant Berbers.

Virgil now came up in his turn.

"Stop!" he cried. "You will only excite them still more. I know how to silence them; come with me."

Calling the other servants, he gave them their respective instructions, and in an instant, to the general surprise, the horrible din gave place to a profound silence.

His plan was very simple. Knowing that donkeys cannot bray heartily unless their tails are in the air, he thought of forcing them to lower these appendages by grouping them round the provision bales, and then fastening their tails to the cords of the bales. The donkeys found this argument unanswerable. After a good laugh at Virgil's plan, everyone settled once more to sleep.

At four o'clock in the morning, Mabrouki's rattle gave notice that it was time to start. The travellers were coming out of their tents one by one, when they were startled by the sound of Virgil's voice pitched in a high key.

"Dogs of Arabs! Gaol birds! You shall pay for this!"

"What is the matter, Virgil?" exclaimed M. Mauny, running up.

"The matter? Why, those dogs of black devils have decamped with all our provisions!"

"You don't say so!"

"Look, then! They have carried off everything, meat, preserves, biscuits, even the water-skins! and that must be out of sheer mischief, for they had plenty of water without taking ours!"

"We must set to work to pursue them," said Norbert, "they can't have gone far!"

"What do you think about it, Mabrouki?" said M. Kersain.

"I think it will be useless; supposing we do overtake them, they will have already hidden the provisions in the sand, and as soon as they see us they will hasten to disperse."

"Well, what are we to do, then? We are not going to die of hunger!"

"There is one thing to be done."

"What?"

"Go to the Zaonia of Daïs, and buy some provisions."

"Is it far?"

"Three leagues off towards the east. But the road IS too bad for the horses."

"In that case what is the alternative?"

"If you like, I will go there with two men and two camels, and will rejoin you at the first halt. You have only to keep due south; one of the Arabs will guide you."

This plan was approved and put into execution at once.

Mabrouki left whilst the tents were being struck.

At this moment appeared a strange being, whom it was difficult to recognize for the correct and irreproachable Tyrrell Smith. It was himself, though, but in a deplorable condition; he was wet, muddy, and covered with dung from head to foot. He was greeted by a general peal of laughter.

"I can't understand it," he said. "It must have rained in torrents. Look what a state I awoke in."

"This is getting serious!" said Virgil, as if seized with a new idea.

He ran to the tent of the model servant, and found it flooded. The ground was nothing but a vast puddle, in the midst of which floated the leather skins, once full, but now quite empty.

"This is another trick of those dogs of Berbers," said Virgil. "It is their return for the cudgelling you gave their young donkeys."

"Let us be thankful," said the doctor, "that they have not taken the water-skins." He was of a very optimistic temperament. "At least," he continued, "we can fill them from the pool yonder."

"Yes," said Virgil, "fill them with nigger-boys' dishwater!"

"How so?"

"They have so well stirred it up that there is not a drop fit to drink. It is only mud."

To their annoyance they found this but too true. The indignation of Tyrrell Smith knew no bounds.

"There is no more water?" he cried, in a voice strangled with emotion.

"Not a drop!"

"But how," said he, red in the face with anger, "but... comment... moi.. préparer... le tub de Sir Bucephalus?"

"His what?"

"His tub...his bain...; there!"

"Ha! ha!" laughed Virgil, "that is the very least of my anxieties, I can assure you."

This was not very consoling for Tyrrell Smith to hear. The march was resumed, although it must be owned in a somewhat spiritless manner, for no one would have been sorry to have had something to eat.

Virgil, at the last moment, was seen to be actively engaged in collecting twigs and handfuls of dried herbs which he made up into a bundle.

"Are you afraid of being frozen on the way? and do you intend lighting a fire on your saddle-bow?" asked Tyrrell, who was still smarting from the previous ridicule of the other. "You have guessed exactly right," imperturbably answered Virgil.

Before starting afresh, he loaded his camel with two enormous bundles of wood and four empty water-skins.

The sun was not yet visible above the horizon. The air was fresh and balmy; and the travellers, as they went along conversing cheerfully, ended by forgetting that they had had no first breakfast, and that the second was problematical. Dr. Briet, as curious as ever about the mission of M. Mauny and his committee, made three or four fresh attempts to extract an answer. But the young savant skilfully parried his questions, and as to the baronet, it was much if he answered even by a monosyllable.

After three hours' march they reached a little grove of thinly-planted sickly-looking trees. The ground was covered with a kind of moss, and with tufts of grass so fine and silky in appearance as to resemble spun-glass.

Here they encamped afresh, on the Arab declaring it to be the meeting-place Mabrouki had fixed upon. But they searched in vain for the water the verdure had seemed to promise; there was not a trace of any.

Two hours had gone by and Mabrouki had not returned.

The sun was now high above the horizon, and the heat overpowering. Our travellers began to feel the pangs of hunger by this time.

"We have guns," said Virgil suddenly. "I don't see why we should wait any longer for our breakfast!"

And before anyone had time to ask for an explanation of his words, he had fired at and brought down two birds resembling pheasants, whom his piercing eye had descried peacefully slumbering on the top of a palm-tree.

No more was needed to arouse the whole feathered population of the grove, and with loud cries a number of birds flew up to the sky and descended after a few minutes. Virgil had already lighted a splendid fire with his two faggots, and was soon busily engaged in plucking his pheasants. Norbert and the baronet, following his example, soon brought down a dozen birds of varied plumage. The main part of breakfast was thus amply provided for, but, as Gertrude remarked, a little bread would not be amiss.

"Bread!" cried Virgil. "Nothing easier; we shall have it in a quarter of an hour... Hi! comrade!" he went on to Tyrrell Smith, who with arms akimbo, stood looking at him, "come on with me!"

He drew him towards a kind of ravine made by the rains. In it grew a sort of reed two or three yards long.

"What will you do with this, pray?" asked Tyrrell, in a bantering tone.

"With these reeds? I' faith I don't quite know."

"They are not reeds. They are what we in Algiers term sorgho, and are here called dhoura... not, perhaps of a first-rate quality, but it is Hobson's choice. We will begin with gathering in the harvest, and then we will turn ourselves into bakers."

While speaking he cut with his pocket-knife several sorgho-roots heavy with grains, made them into a sheaf, and took them back to the camp. The grains were perfectly ripe, and were easily crushed between two stones.

"But," observed the Doctor, "water is essential in order to make bread."

"I think so, too," answered Virgil. Groping in his pocket, he drew out a leaden ball, and carefully loading his gun with it, he looked about him. At a distance of about thirty yards stood an enormous and strangely-shaped fig-tree, the trunk of which was entirely bare. Virgil took aim at it.

"Good!" cried Smith. "He has found a target." The shot took effect. In an instant a stream of fresh limpid water was seen to spring from the wounded tree.

Fatima stood amazed, and felt inclined to look upon worthy Virgil as a magician. He had seized a 'water-skin, and was hastily filling it at the improvised fountain.

"See what it is to be practical!" exclaimed the doctor.

"I knew that the tribes of the Soudan were in the habit of scooping out the trunks of certain trees in order to make reservoirs of them, carefully closing them up afterwards; but I should never have looked for one in the fig-tree, neither should I have thought of opening it in that manner."

"It was not my invention," modestly said Virgil. "I learnt it from the Touaregs. They generally fire at their reservoirs in order to open them, and as the fig-tree looked like one, I thought it well to make sure. But see! my water-skin is nearly full. Please hold it under the fountain, Monsieur Smith, whilst I get the other skins off the back of my camel."

The Doctor went back to the travellers, who were sitting in the shade under the tent, and told them of Virgil's new exploit. They all went off at once to see the marvellous tree and drink some mouthfuls of water.

When they reached the foot of the fig-tree they found Virgil in a state of the greatest excitement.

"There is no more water!" he cried out, "and I don't know what has become of the Englishman with the full water-skin I entrusted to him... Smith!! Monsieur Smith!!!" he screamed at the top of his voice.

"What is the matter?" replied a voice in the distance from a tent.

"I want to know where you are, and above all, where is my water?"

"The water? Here, of course!"

The phlegmatic face of Tyrrell Smith now appeared at the opening of the tent.

Virgil ran up, followed by all the travellers. An unexpected sight met their eyes.

The model domestic had extracted from his inexhaustible portmanteau a splendid gutta-percha tub, and, spreading it open, filled it with the contents of the water-skin, not keeping even a drop to appease his own thirst; he had poured in a flask of toilet vinegar and thrown in a gigantic bath sponge. With a satisfied look, and a white bathing-dress on his arm, he now bowed to Sir Bucephalus, and said solemnly:

"Your bath is ready, sir!"

Virgil had to be forcibly held down, otherwise Tyrrell Smith would have been strangled.

"Insufferable blockhead!" exclaimed the baronet, "you are at it again!" and turning to the others he said: "Mademoiselle, messieurs, I don't know how to apologize; believe me, I had nothing to do with this incredible stupidity of my servant... I don't know why I don't throw him into his tub, and hold his head under water till he is done for." No contrition appeared, however, on the countenance of the model domestic. He was simply astonished at the scolding, for was it not the duty of a good valet to prepare his master's matutinal bath? Virgil, left to his own devices, would soon have opened Smith's eyes to a different view on this point, but luckily for the ears of Tyrrell Smith a fresh incident turned up in the arrival of Mabrouki Speke.

Mabrouki Speke had been detained longer than he wished by bad roads and by the dilatory ways of the Zaouia people. But here he was at last, with provisions, fresh water, and everything needful... There was no room now for any feeling but that of amusement at Virgil's mischance, and the latter soon laughed as heartily as the rest, resolving, however, to keep a sharp look out in future over the proceedings of his comrade, Tyrrell.

The journey was completed without further incident.

Resuming their march at sunset, they halted at midnight, to proceed afresh at four o'clock in the morning, hoping in this way to reach the residence of the Mogaddem soon.

s

s

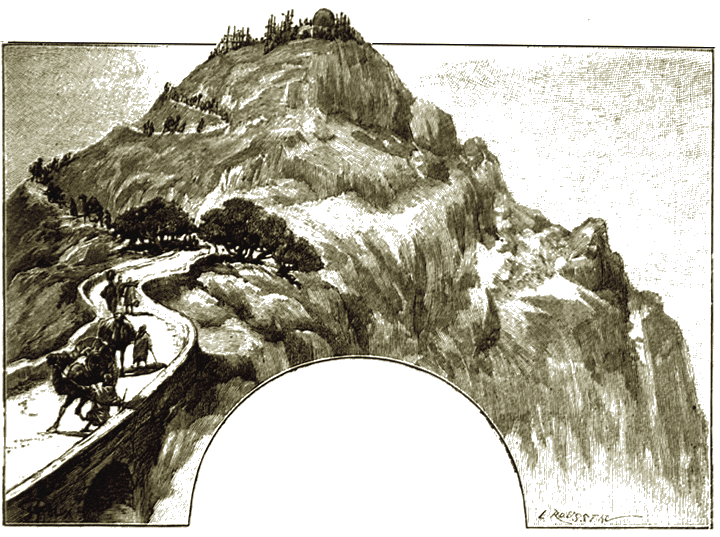

IT was seven o'clock in the morning, and the sun already scorching, when Mabrouki Speke, pointing to a white speck on the summit of a hill at the horizon, said,— "There is Rhadameh!" Every spy-glass at once leapt out of its case, and disclosed to view the dome of a minaret whose white walls glistened amid the surrounding verdure.

"We shall be there in forty minutes," added the guide.

"And it will not be a moment too soon," exclaimed Mademoiselle Kersain, putting her hand to her white linen helmet, "for this martial head-covering is really suffocating, and yet I dare not take it off."

"Indeed you must not!" answered Norbert, anxiously. "You would have a sunstroke, which would be anything but pleasant."

"Perhaps you would rather that some one else should have one—myself, for instance!" laughingly observed Dr. Briet, as he vigorously wiped his forehead. "The heedlessness of these young astronomers is something deplorable," he continued; "what on earth would become of the expedition deprived of its head doctor? And yet I may take off my helmet as often as I like, without you noticing it."

In less than half-an-hour the little caravan reached the foot of the hill. The horses and camels went lightly up the stony road, and soon came to a waste piece of ground, bounded on the east by the walls of the Zaouia. This is the name given in Mahometan countries to the convents or stations that serve as sees or residences for the ecclesiastical dignitaries. The travellers dismounted amid an ever-increasing crowd of pilgrims of every condition, colour, and age, who had all come to consult the famous Mogaddem. There were negroes from Darfour or Kordofan, Arabs wrapped in their wide burnouses, Turks in their baggy trowsers,—Jewish merchants even were to be seen spreading out their poor merchandise in the midst of the horses, asses, and camels. Some of the asses were uncommonly like those who had been so suddenly cured of their musical mania by Virgil two nights previously; but it was impossible in such a bewildering crowd to identify either the asses or the Berbers, whom they had only seen at night-time. So no one even tried to do so; they were in too much haste to expedite matters, and to see the Mogaddem.

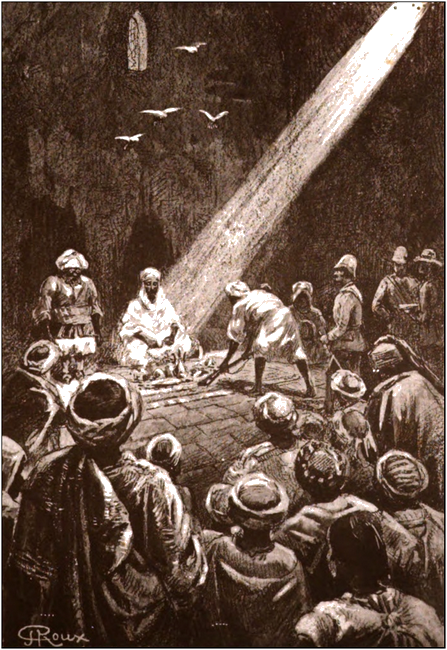

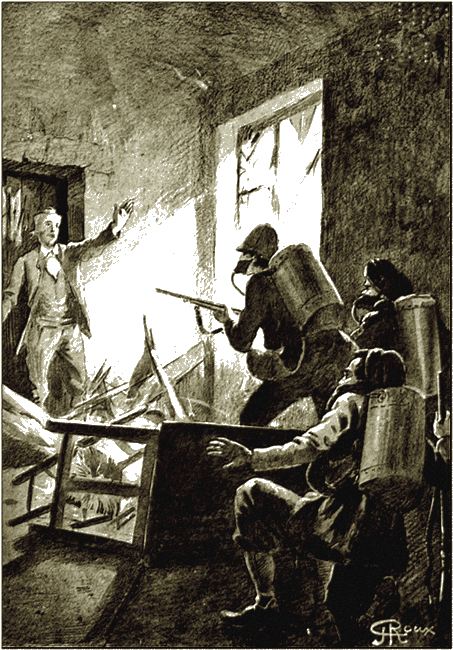

The latter received the homage of the faithful in a large paved hall, opening outwards by two double doors. The entrance was free to all the world, and our travellers passed in with the others.

Their first impression was one of physical pleasure in exchanging torrid heat and blinding sunshine for the delicious coolness of a vast vaulted nave, that was lighted only from above by windows of stained glass. When their eyes had become accustomed to the semi-obscurity, they perceived at the further end him whom they sought.

The holy man was seated cross-legged in the middle of a wonderful square carpet, whose brilliant colours were the only relief to the dead whiteness of the bare walls. He wore a wide cotton shirt, and a white turban was tightly wound round his head. He sat motionless with downcast eyes, as if in deep meditation. His leanness was extra-ordinary. Although, to all appearance, scarcely more than forty years of age, his coal-black beard was thickly strewn with silver. The skinny fingers, dried up as those of a mummy, slowly passed the beads of a heavy amber rosary; indeed, but for this movement, he might have been thought lifeless, for no sound, not even a sigh, issued from the half-open lips, and even the long eyelashes lay motionless on his cheek. The faithful crowded round the carpet, and followed with eager eyes the slow passage of the beads that dropped one by one from the Mogaddem's fingers. From time to time a row of musicians seated against the left wall beat upon their drums with the palms of their hands. This was the signal for a lugubrious groan that resounded through the hall, whilst all the faithful were seized with a simultaneous holy shudder. They were evidently in expectation of something, and they did not always wait in vain. A stick of dried wood, thrown as if by chance in front of the Mogaddem, would suddenly rise up hissing, and glide with a wavy motion to his venerated feet. The stick had become a serpent! The faithful rush to save the prophet... when lo! the serpent stretches out its head and quietly subsides into merely a stick once more!

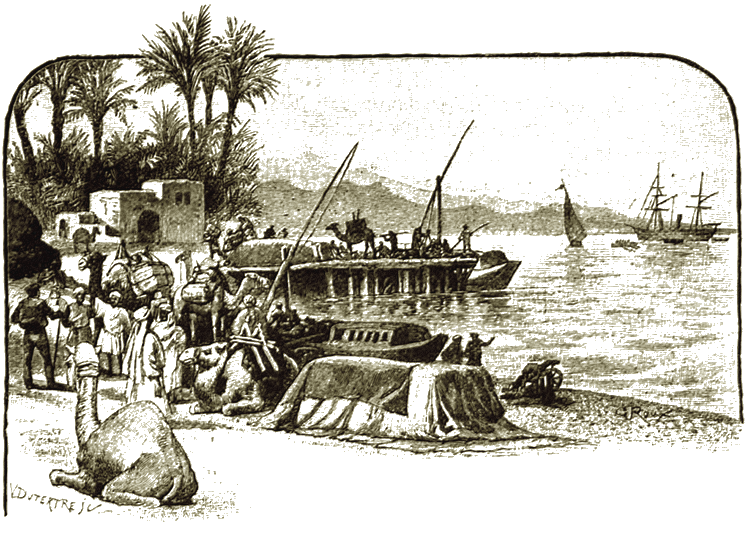

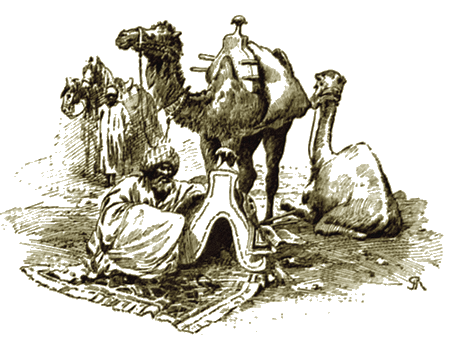

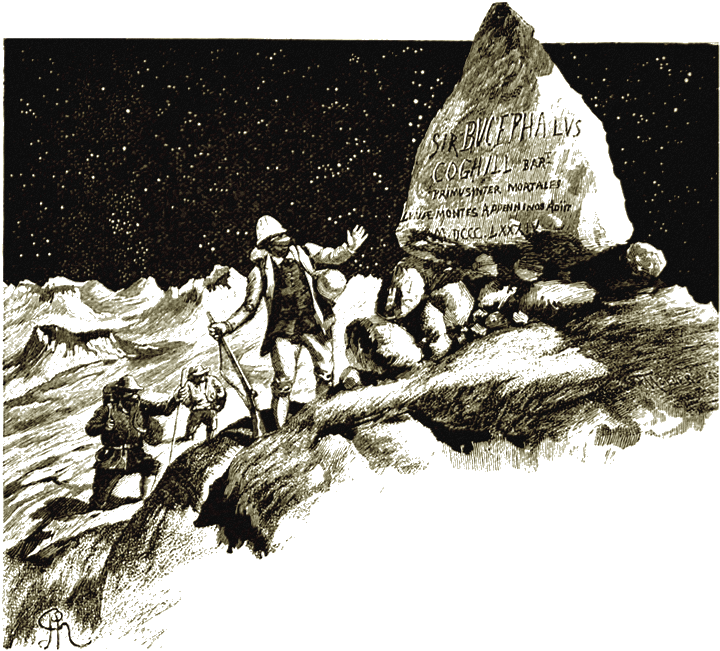

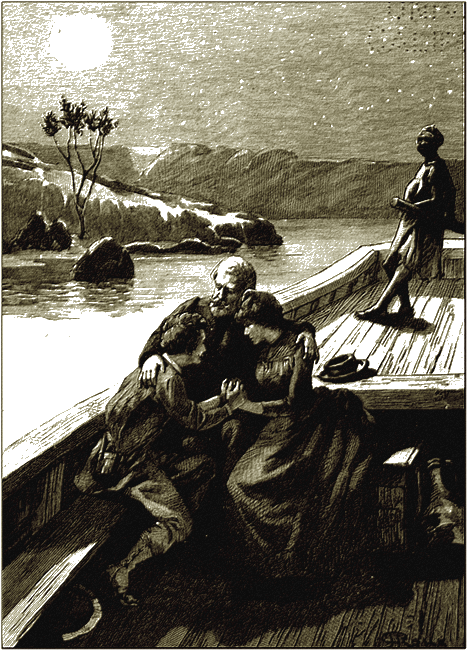

A halt in the desert.

Or again, numbers of white pigeons flying through the narrow opening in the roof, would hover round the saint, and at a word, or even only a sigh, from him, hang motionless in the air, as if suspended, three feet above the earth. Another sign or sigh and, behold, they all fly away! The faithful were lost in a stupor of amazement at seeing such prodigies. At each fresh signal they tore off in feverish haste everything valuable they had about them—a silver-mounted poniard, or silken purse, or perchance a curiously chiselled cocoa-nut, and flung all at the feet of the saint.

He took no notice, and appeared as if rapt in ecstasy. Only if some object of greater value was offered him, such as a piece of silk or a wooden bowl filled with gold-dust, or a fragment of ivory, he would heave a sigh, and, raising his heavy eyelids, murmur a few words in reply to the supplicant's question.

At his right hand stood a singular being, a kind of deformed dwarf, who made hideous grimaces, and attracted the attention of the visitors almost more even than the Mogaddem.

He was not taller than a child of four years old, although his shoulders were of an extraordinary width. He was, in fact, as broad as he was high, and his brawny muscular arms hung down nearly to his enormous feet. A complexion black as ebony, an abnormally wide mouth, snub nose, and little eyes hidden behind thick spectacles, stamped him a perfect monster. His costume was a red silk blouse, confined round the waist by a wide blue sash; white pantaloons, yellow boots of morocco leather, and an immense white turban, from which his beard appeared to be growing, so short was the space between his forehead and his mouth.

This dwarf was apparently dumb. He stood on the edge of the carpet, about two yards from the Mogaddem, on whom he kept his spectacled eyes fixed, without seeming to notice the strangers near. But every now and again the dwarf and his master exchanged mysterious signs that struck terror into the spectators. Doctor Briet whispered to Norbert that he fancied he recognized the mute alphabet.

At the near approach of our travellers, this singular being was evidently disturbed. A gesture of admiring surprise escaped him. His eyes shot out fire from behind his glasses. But it was only for an instant that his habitual calm was thus troubled; he quickly resumed his passive contemplation of the Mogaddem, whose ecstasy had not been interrupted in the least.

Meanwhile Mabrouki, the guide, spread out on the carpet the gifts, without which it would have been the height of bad taste to have approached the holy man. The ascetic physiognomy of the Mogaddem assumed an expression of earthly delight on beholding at his feet a gold chronometer, a spy-glass, a double-barrelled fowling-piece, and a china crape shawl. A glance escaped from under the piously downcast eyelids, and with a deep sigh the saint awoke from his silent contemplation and looked with benignity on the new faithful.

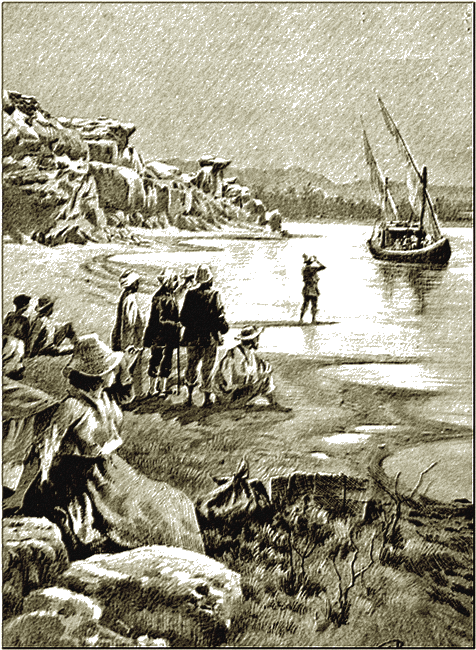

Mabrouki, the guide, spread out on the carpet the gifts...

Norbert came to the front then, and couched his request in the requisite formula through the medium of Virgil, who repeated his words in Arabic.

The Mogaddem, who had fallen back into deep abstraction again, with closed eyes and hands crossed upon his rosary, now roused himself afresh to consult his dwarf. The latter made several rapid signs, then prostrating himself on the ground, he struck it thrice with his forehead.

After a fresh interval of silence, the Mogaddem murmured in a squeaky voice some words that Virgil hastened to interpret.

The holy man was quite willing to assist the travellers with the services of his children, the braves of the tribe of Cherofa. But it was first necessary to consult the oracle.

"What oracle?" asked Norbert.

"The oracle of the holy Sheikh Sidi-Mohammed-Jeraïb," said Mabrouki discreetly, whilst the Mogaddem, who had resumed his ecstasy, gave no more sign of life.

"And where does this new saint hang out?"

"In his tomb, five hundred paces off," gently answered the old guide, whom a long experience of Europeans had accustomed to their audacity of language. "Only," he added in an aside, "it will cost another pretty sum!"

"What matter, if it is necessary!"

"And besides, it may be amusing!" said Gertrude, who was always ready for novelties in the way of wonders.

The travellers sallied forth to find the tomb of the sheikh, without paying any more attention to the Mogaddem and his dwarf. It was moreover evident, from the renewed abstraction of the holy man, that he considered the interview at an end.

They caught sight of the tomb on a waste piece of ground three or four hundred yards from the audience-hall, and beyond the precincts of the Zaouia. It was not worth while to remount, and the party traversed the short distance on foot.

They had taken about twenty steps when Gertrude stumbled over a stone. At one and the same moment the baronet and Norbert rushed forward with extended arms to her assistance. Gertrude could not but laugh at their haste, and not wishing to slight either, she took both arms held out to her. This way of settling affairs displeased each of them, and they both went away sulkily, to her increased amusement.

"What a monster that dwarf is!" she cried. "Did you notice his resemblance to a monkey? I wonder what is the secret of his influence over the Mogaddem... for it is evident that the saint undertakes nothing without his advice!"

"They must have done some bad business together," said Norbert in a tragic tone.

"Why such a supposition as that?" answered the baronet. "Would not their faith be a sufficient link?"

"Faith in the power of money, you mean, doubtless," rejoined the young savant ironically. He had not failed to note the stealthy glance the Mogaddem had cast upon the gifts.

"Well! That is perfectly compatible with more noble convictions," replied Sir Bucephalus. "What can be done without money?"

"I am inclined to think that the dwarf is simply the Mogaddem's appointed conjuror," said the doctor, who, with M. Kersain, had been listening to the little discussion. "Did you notice his Indian costume? In Bengal I have often seen the like marvels done by the jugglers of the country. I have seen them make serpents out of wood, paralyze pigeons, and perform even greater wonders still."

"Those are enough, I am sure!" exclaimed Gertrude. "How on earth do they manage to arrest the flight of the pigeons and keep them perfectly motionless in the air?"

"Probably they only appear so, whilst in reality they are slightly fluttering their wings; they are under the influence of a kind of magnetism. But in India I have seen something much more wonderful. I have seen a child of seven years old raised in the air to the height of three feet like the doves just now."

"You saw that yourself?"

"I seemed to see it. And there was no cheating; there were no suspending cords, no supports of any kind. The phenomenon is inexplicable by any of the known data of European science, and it is not the only one of the sort. For instance, on another occasion I saw a Bengalese magician scratch up with his nails the parched soil in a garden alley, then plant in it a camellia seed, which germinated under our eyes, and in a quarter of an hour it became a plant covered with flowers."

"Wonderful!"

"It was all an illusion of the senses, due to the prodigious dexterity of the conjuror. But I have seen these Indian fakirs and jugglers perform other marvels that I scarcely dare to relate to you, so inconceivable are they. These people have a host of traditional secrets touching upon phenomena scarcely known as yet to modern physiology."

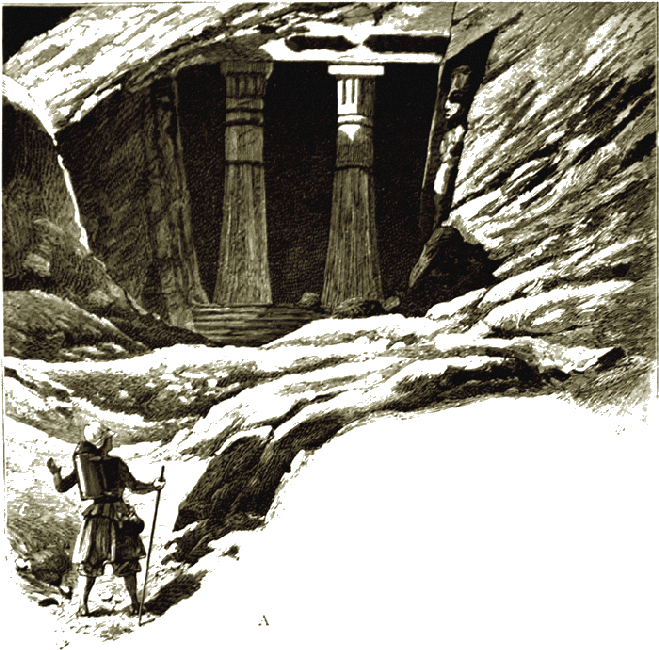

Conversing thus, they reached the tomb of the sheikh. It was a small square edifice made out of one block, five yards long and four wide, overshadowed by three elegant palm-trees.

At the entrance, two dervishes with parchment-like countenances and shaven heads awaited the visitors. They came forward, bowing profoundly, and on learning from Virgil that it was a question of consulting the oracle, demanded a preliminary contribution of five piastres a head. Pocketing this, they announced that the visitors must enter the sanctuary barefooted.

Our travellers were obliged to submit, and left their boots therefore at the door.

Suddenly a fresh difficulty arose. The dervishes objected to admit Mademoiselle Kersain and Fatima. But this scruple quickly melted under the influence of another gold coin.

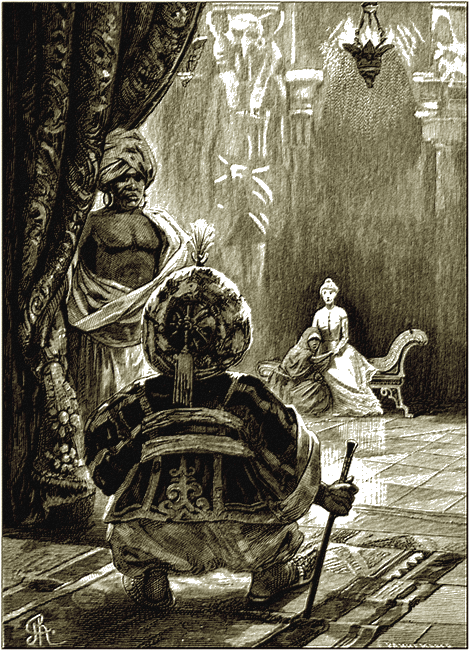

At length the matter was settled, and they all went into the holy tomb. It proved to be a bare hall containing only a carpet well worn by the knees of the faithful. At the right angle stood a kind of cup or vase of grey marble without any apparent opening. One of the dervishes explained, through the medium of Virgil, that it received questions, and gave forth the answers of the oracle, but that the sacred formula must first be uttered.

"Very well!" said Norbert, shrugging his shoulders. "Let us have the formula then, Virgil, since we must say it."

The two dervishes, now prostrating themselves on the carpet, lifted their hands above their heads, and said an Arabic prayer together.

Virgil repeated it slowly so that his master might articulate each word with him, which the young man did, not without evident impatience.

"Now," said the dervish who took the lead, "let the stranger lord address himself directly to Sidi-Mohammed-Jeraïb."

"Confound it!" said Norbert in an aside, "the oracle really ought to speak French."

"I speak French!" at once answered a sepulchral voice, issuing apparently from the bottom of the cup.

This unexpected manifestation so astonished the visitors that they were at first stunned. Mademoiselle Kersain turned pale. Fatima's eyes dilated with fear, and she seemed on the point of fainting.

But Norbert soon shook offhis emotion, that sprang from surprise only, and he now bent down to the vase with a smile upon his lips.

"Sidi-Mohammed-Jeraïb," he said, "since you know French so well, we can talk freely. I am in need of your powerful assistance, in order to obtain the necessary means of transport from the tribe of Cherofa, your beloved daughter. Will you help me?"

At the name of the saint the two dervishes had thrown myrrh into the lighted censers hanging from their sashes, and swung them to and fro. A thin thread of smoke rose up, filling the hall with a penetrating perfume. The voice of the marble cup answered:

"You must first tell me what has brought you to the Soudan, and what end you have in view."

The young astronomer could not repress an involuntary gesture of astonishment, whilst his travelling companions drew nearer to hear the interesting dialogue.

After an instant's hesitation, Norbert thought he had better continue the conversation.

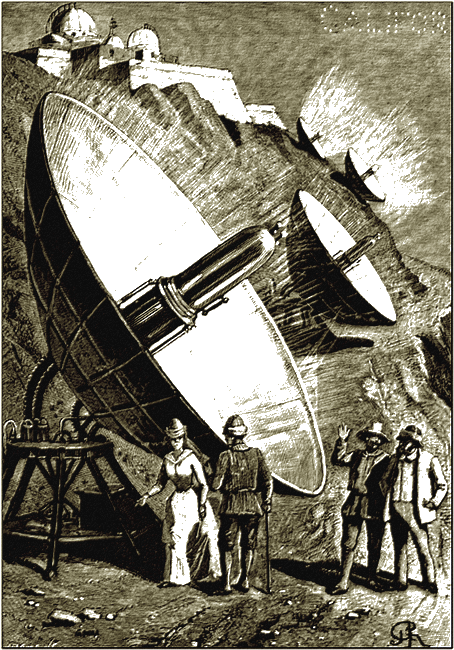

"I have come," he replied, "to study the wonders of the heavens, and for this purpose I mean to erect an observatory on the table-land of Tehbali."

"You are not telling the whole truth," replied the oracle. "You have a more audacious scheme in view!"

For an instant Norbert was put out of countenance, and held his peace.

"I am omniscient," resumed the oracle. "Nothing escapes me. I know the present, the past, and the future. Shall I prove it to you by saying what you seek to do on the mountain of Tehbali?"

"Say on," said Norbert merrily.

"Laugh not! Your levity is ill-timed... for your undertaking is a most foolish one. You are come hither to contend against the eternal laws that regulate the Universe. If you are our friend, we can but pity you, inasmuch as you will be vanquished in the struggle. If you be an enemy, Nature will take our vengeance upon herself!" It is impossible to give any idea of the effect this sinister prediction from an invisible mouth produced upon the audience. Norbert laughed no more. His reason could scarcely master the stupor that came over him on hearing the replies given by the oracle. But still he was loth to believe that any one at Rhadameh could really know his secret.

"Think you," resumed the voice in terrible accents, "that anything concerning the people of Allah can escape me? Your scheme had not been formed three minutes ere it was known to me! You have the presumption to aim at suspending the course of the moon, to attract it to the earth and render it accessible to human cupidity! That is your senseless scheme! But I here tell you that it will not succeed!"

Norbert and Sir Bucephalus looked at each other in amazement. Was it possible that their secret had been violated? How could the pretended oracle know it? The only explanation they could think of was that one of the commissioners left behind at Suakim must have been indiscreet, and the betrayed secret, travelling faster than the caravan, had preceded them to Rhadameh.

It was indeed astonishing to meet with it here through the invisible agency of an intelligence that could speak French, and whose voice issued from a marble vase!

Doctor Brief was evidently most deeply interested in the revelations. His twinkling little eyes went from Norbert to Sir Bucephalus, trying to read their faces and find out whether what the oracle said was true. Not less great was the surprise of M. Kersain and of Gertrude. As to Fatima, she had fallen on her knees as soon as the voice first spoke, and, hiding her face in her hands, gave herself up to superstitious terror. And no wonder! For it would have tried stronger nerves than those of the little servant to have heard the terrible voice issuing apparently from the earth; the effect heightened by the sighs of the dervishes who were squatting on the carpet, and the aromatic perfume that in spiral clouds of bluish colour rose up from the smoking censers. Virgil alone took it philosophically, looking round him with all his accustomed sang-froid.

Norbert was the first to recover himself.

"Well," he said imperiously, "if you know our scheme, you also know that it is in nowise inimical to the Arab people. Yes or no; will you help us to the necessary means of transport?"

"I will," said the oracle.

Then suddenly condescending to earthly details, he continued:

"You must pay in advance ten piastres a head for every man or beast, and in seven days the 800 camels you require shall await you with their guides under the walls of Suakim."

"That is what I call speaking to the point," cried Norbert gaily, "and this oracle evidently knows how to do business! To whom must we pay the 16,000 piastre?"

"To the envoy of the Mogaddem, who will fetch them, and will give a receipt at the French consulate."

"That is settled, then. But tell me, Sidi-Mohammed Jeraïb, is our alliance to end with the transport?"

"It will endure so long as you regularly pay tribute to the Mogaddem."

"What tribute?"

"That which is due to him, if you wish his children to protect you in the desert, and give you the assistance you need."

"How," said Norbert, rather ironically, "would they lend themselves to an enterprise that you disapprove?"

"Yes; if you pay the tribute, they will not trouble about your plans."

"And how much is it?"

"Twenty times twenty piastres a month."

"I willingly agree," replied Norbert.

"Then farewell... and may Allah go with you!"

With these words a lugubrious groan issued apparently from the vase. The dervishes arose, and slowly intoning a psalm in a low voice, they retreated backwards to the entrance, swinging their censers the while. The visitors instinctively followed their example, and, still under the influence of the astonishing scene, put on their shoes in silence. Fatima was so completely stupefied by it all that she stumbled over her Turkish slippers, and would not have found them again, had not Virgil picked them up and put them into her hand.

They now set off towards the encampment chosen by Virgil at a few paces distant. He had already pitched their tents, and had brought thither the fresh provisions they had procured at the Zaouia. After a little while they all began to exchange ideas concerning the strange facts they had witnessed. Norbert alone remained silently buried in his own reflections.

None of them could understand it. That there was some clever jugglery behind was plain, but how was it managed? How was it that the oracle could give such an exact statement of the young astronomer's project? The doctor especially was devoured by curiosity.

"Come, Sir Bucephalus," said he merrily to the baronet, "you who are in the conspiracy can tell us if the oracle was right! There is Mademoiselle Kersain dying to know the truth. Will you leave her to find it out from M. Mauny?"

"Speak for yourself, uncle," exclaimed Gertrude, with a merry laugh; "don't try to hide your curiosity under cover of mine. You know that you have been in an agony for three days to find it all out!"

"I acknowledge it," replied the doctor. "But I swear that my curiosity is purely in the interests of science."

"M. Mauny," observed M. Kersain, "did not certainly contradict the oracle. But if he does not see fit to trust us with his plans, we have no right to force his confidence."

"Bosh!" responded the doctor, "when the secret is flying about the desert!"

At this moment, Norbert, who was walking on in silence, turned round, and addressing the consul and his daughter, said:

"The oracle made use of a very simple artifice. There is evidently an acoustic tube connecting the Zaouia with the tomb of the sheikh, and thus enabling the Mogaddem to hear and answer the questions; unless, indeed, it is mere ventriloquism. But still there remains to be explained how it is that this fellow can speak French, and, above all, how he has managed to ascertain my project. For, as a matter of fact, he did not tell any lies. I have in reality come to the Soudan in the hope of getting hold of the moon, and under pain of being taken for a fool, I must now explain how I intend to set about it. Do you not think so, too?" he added to the baronet.

"Most decidedly," answered the latter.

"Well, then," pursued Norbert, "if Mademoiselle Kersain and these gentlemen will grant me patience, I will recount at breakfast-time how the idea, which must seem so scatter-brained to them, first came into my head. I don't ask them to agree with it as practicable. I only beg them to believe that I have good reason not to deem it such utter folly as the sheikh pretends to think."

This was a delightful announcement to Doctor Briet, and as they had now reached the tents, all sat down to breakfast. When the dessert was put on the table, the young savant redeemed his promise. We will content ourselves with giving the substance of his account, adding several details concerning his associates that a natural reserve led him to suppress.

SEVEN months previous to the arrival of the Dover Castle at Suakim, three men were together on the ground floor of a house in Queen Street, which is one of the most beautiful in Melbourne, herself the queen of Australia. Although near mid-day, that busiest of commercial hours in Anglo-Saxon cities, these men were doing nothing but lazily reading the Argus, Herald, Tribune, and other morning papers. They sat on morocco arm-chairs in front of great mahogany desks. The room was separated from the corridor by panes of ground glass, and a partition of the same material divided it from the street, and bore in brass letters the inscription:

THE ELECTRIC TRANSMISSION CO. (LIMITED),

PETER GRYPHINS, VOGEL, WAGNER & CO.,

SOLE AGENTS.

Against the right wall stood a magnificent iron safe of stern business-like aspect. The left wall supported a marble chimney-piece on which stood models of electrical machines and submarine cables; whilst beautifully framed diagrams and plans occupied every free space. In its own quiet corner stood the telephone, ready for confidential communications. Openings were cut here and there in the ground glass for the various purposes of "deposits," "inquiries," and "dividends." A thick Turkey carpet covered the floor, and everything in fine bespoke opulence and security.

Perhaps, indeed, a little too much security, judging from the idleness of the three partners.

"Ignaz Vogel," suddenly said one of them. "Peter Gryphins?"

"How much have we in the cash-box?"

"Seven pounds sterling, eleven shillings, and threepence."

"What payments are we expecting before the end of the month?"

"There is a credit of twenty pounds to Wolf; but it is no more likely to be paid than that of last month; four pounds due from Johannsen, and twenty-eight shillings from Krause."

"And how much have we to pay on the 30th?"

"Three thousand pounds sterling, six shillings, and twopence."

"Are they pressing debts?"

"Most pressing! They have the signature of the firm, the stamp of the house, and the sign manuals on paper bearing the royal arms."

"Does this amount include the accounts or the rent?"

"No! Peter Gryphins."

"Nor our salaries and those of Costerus Wagner and Müller's wages?"

"No! Peter Gryphins, not even the wages of Mrs. Cumber, the housekeeper."