RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

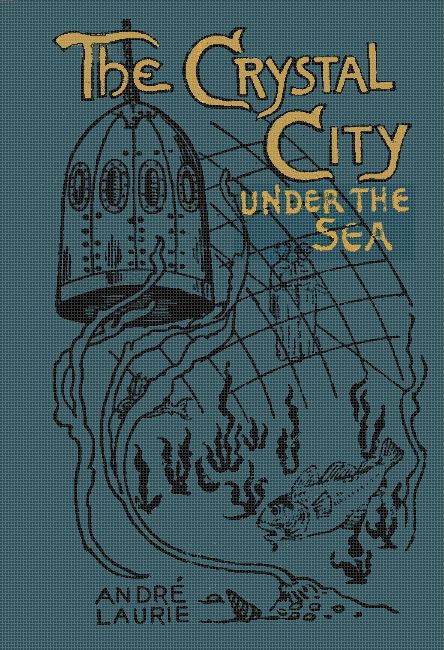

"The Crystal City Under the Sea,"

Sampson Low, Marston, & Co., London, 1896

"The Crystal City,"

Estes & Lauriate, Boston, 1896

"The Crystal City,"

Estes & Lauriate, Boston, 1896

ON the 19th of October, in the year 18—, a strange and tragic accident happened on board the cruiser Hercules, en route for Lorient, after long and laborious duty on the station in the Gulf of Benin.

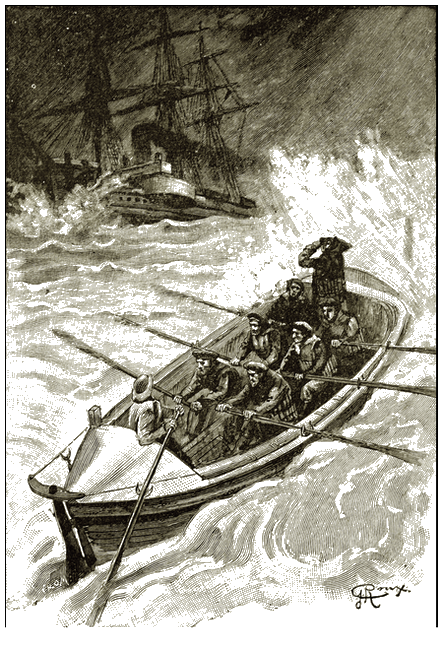

They were in mid-Atlantic, just above the Azores, as nearly as possible to the spot where 25° E. longitude crosses 36° N. latitude. The vessel was running at full speed to the N.N.E. before a cyclone, which had come up about six o'clock in the evening. It was seven, and the starless night only added to the horror of the storm, when either a mistake on the part of the helmsman, or a sudden veering of the wind, brought the cruiser broadside to a formidable wave from the west. A liquid mountain struck the upper deck of the Hercules a blow as if a hammer had done it, carrying away "with it the starboard gun and its carriage; then dashed away like a cataract, leaving a surface of thirty square feet Or more shaved as clean as a hulk. The next instant, as the vessel pursued its course, running before the cyclone, a cry, followed by a second, was heard from the maintop: "An officer overboard, from the upper deck!" "A man wounded!" At the first call the luminous buoy was severed by the stroke of a hatchet, and Commander Harancourt, rushing to the speaking-trumpet, gave in person the order to stop. In two minutes one of the life-boats was afloat, and set off in the tumult of boiling waters in search, and disappeared into the darkness. Amid the gruesome howling of the wind and the furious blows of the waves, seemingly enraged at the slackened speed of the cruiser, the officer in command brought his verbal report to his chief. The officer carried away by the wave, with the cannon from the upper deck, was Midshipman Caoudal. The man wounded in the thigh by a splinter of the planking was seaman Yvon Kermadec. Every one crowded round to listen to the lugubrious report. A half-hour of intense anxiety passed before the life-boat signalled its return, and the fruitlessness of its search. It was hoisted on board, and the dripping crew were treated to a ration of hot rum. Every man of them was obliged to own, with a sob in his voice, that any further attempt at rescue would be useless. The sea held its prey, and would not give it up.

The return of the life-boat.

The Hercules went on her way, with the poignant regret of every one on board at abandoning to the deep a brave young fellow, certain of promotion, fallen ingloriously and without advantage to any one, in full health and hope, at the threshold of his career. René Caoudal was the most popular officer on board, a great favourite with his brother officers; and, among the roughest of the men, there was not one who did not shed a tear. When the commander went below to the hospital to see Yvon Kermadec, he was coming to from a deep swoon, thanks to the energetic means applied by Dr. Patrice, and the frightened blue eyes in his honest, brown Breton face had opened. Presently memory returned to him with the pain; and he explained what occurred as follows:

"I was leaning with my back against the mizzen-mast. M. Caoudal came and went, as if he were surprised at the change of wind, when, all of a sudden, the wave broke right over us. I never saw one like it all the five years since I left Paimpol, nor even before that, when I used to go fishing for cod. It was like a wall of molten metal pouring itself over the Hercules. Everything was broken up, smashed to pieces, and washed away. I had a sort of confused vision of M. Caoudal thrown against and clinging to the breech of the cannon on the upper deck, then, lifted up and swept away with the rest. At the same instant I was blown like a flag against the mast near which I was standing, and an enormous piece of wood broke my left leg, and then I became unconscious. Better for me if I had succumbed," added the poor lad, in a discouraged tone. "What is the use of living, if I am to lose a leg? I shall be good for nothing. It would have been far better if I had been washed away instead of M. Caoudal! An officer like him is not met with every day!"

This was said with such evident sincerity that the young doctor was deeply moved. Nobody knew better than he what an irreparable loss the French navy had sustained in René Caoudal. He had been his most intimate friend and companion since their childhood. This praise of one whom he had always considered as a brother touched him to such a degree that his hand became unsteady, and he was obliged to wait a moment or two before he could proceed with the dressing of the broken limb. "Come, come, my brave Kermadec, no weakness," said he to the seaman. "Your leg is not lost yet, and I have good hope of your keeping it, but I can't promise you that, unless you take the greatest care to use every means to make it as good again as ever. As to the regrets you express at the premature end of M. Caoudal, certainly they are proper! A braver heart, a more intelligent and distinguished officer, a better son, never lived!"

"How his poor mother will grieve!" pursued the seaman, unconsciously giving expression to the thought that was in the doctor's mind. "It is hard for us who are left behind; it doesn't seem right; people that are devoted to one another here ought to make a compact to die together. Dear M. René! It was he who convinced me of the folly of spending my money at the drink-shop when I went ashore. I was so glad to have got the better of that habit. But now, who will give me good advice? Who will care whether I keep right or not? Clever gentleman though he was, he didn't think it beneath him to talk to me and teach me a heap of things. He used to call me Friend Kermadec. Ah, me! I would have gone through fire and water for him, and to see him swept away under my very eyes, without being able to lift a finger to save him!"

The seaman paused, choked with grief. "You know how dear he was to me, my brave Kermadec," said the doctor at length. "I will try to fill his place to you. If ever you are in need of advice or of help, if you think I can be useful in any way, come to me; for his sake I shall be happy to serve you."

The dressing of the injured limb was accomplished. The commander and the doctor, having cordially pressed the man's hand, left him and went on deck. They conversed a few minutes about the deplorable loss of the young officer before the commander went to draw up his report.

Everybody in the officers' deck saloon was awaiting Patrice with impatience. Still quite young, but as modest as he was clever, lively, a pleasant companion, the doctor was every one's favourite. No festivity was complete without him. But now, unusual cordiality was shown to him. They all knew what a close friendship had existed between him and Caoudal. They listened with breathless interest to the details of the accident that he had gathered from Kermadec.

"What you have to say only adds to our grief," said Lieutenant Briant, an officer about forty years of age, with large, prominent, short-sighted eyes, and grave and somewhat repellent expression of face; "and for my part, I cannot tell you how pained I am at his premature death."

"Dear, brave Caoudal," cried Midshipman des Bruyères, "if he was good-natured and willing to help his inferiors, he was none the less a jolly fellow among his equals. Where shall we find such a cheery messmate? He can never be replaced."

By a common impulse their thoughts turned to the Caoudal family, and the doctor did all he could to satisfy their respectful curiosity about them.

"René," said he, "was the son and the grandson of a sailor. Like him, his father and grandfather were both drowned at sea. He was the only son; and poor Madame Caoudal had a great horror of his entering a profession which she felt to be so cruel, and she never ceased to wage war against any tendency in him towards the vocation of the sea, to which she always owed a grudge. Her friends and the servants were warned to be very careful to abstain from any nautical allusions or anything that might tend to foster a desire to follow the father's example in that respect. Vain precautions! They might as well have tried to prevent a fish from swimming. René was a born sailor; no education but for that end would satisfy him. No one could prevent his seeing from a bend of the river a silhouette of a flying vessel, and what they failed to tell him he divined somehow or other. Nothing in the shape of a boat had ever figured among his toys; but, at seven years of age, he was found making one. "Whence had he got the idea? Surely it must have been inborn. From that time, all his thoughts, waking and sleeping, were taken up with long voyages, to the despair of his poor mother, who saw the birth and growth of a force against which she was powerless to contend. It was still worse when his little cousin Hélène came to live with them. The daughter of a sister of Lieutenant Caoudal, Hélène had been brought up by her mother to worship the profession, and with the most ardent admiration for maritime exploits. The child had been suddenly left an orphan; Madame Caoudal had given her the shelter of her roof, and, with the advent of her niece, fell the frail barriers that she vainly tried to raise between René and an irresistible vocation. At this time the two children were twelve years of age. They had not known each other before, the little girl having always lived in Algeria; but from the first day they were sworn friends. They had the same tastes, the same ambitions. Their talks ran always on the same theme,—distant voyages, expeditions to the North Pole, naval battles, and discoveries of unknown lands. Hélène's bitter regret at being only a girl was somewhat mitigated by the thought of seeing her dreams take shape by proxy. Meanwhile they prepared for future exploits by the most ridiculous freaks. Our embryo navigators made it a duty to leave no nook or corner of the neighbourhood on the banks of the Loire, in which they lived, unexplored. Their adventures 'by sea and by land' were numberless. Hardly a day passed without their coming home either with a bruised forehead, or a limb more or less damaged, and their clothes torn. From that time, René had no wish for any career other than that of the sea. Madame Caoudal, who was a wise as well as a tender mother, brought herself at last to see it, and, sacrificing from that time forward the long cherished hope of keeping her son near her, generously kept her disappointment to herself. She opened, to the children's great delight, the long closed wardrobes where she kept the sacred relics of her husband and his father, and thenceforth everything relating to the navy became a sort of religion to them. It was now no more a question of adventures 'à la Robinson Crusoe,' but seriously to think of preparing for the entrance examination for the naval school. I completed my medical studies the same year that René was admitted. Though there was a difference of six years between us, —a great difference at that age, precluding any childish intimacy,—we had always been good friends; we were neighbours, and our mothers on terms of close intimacy. It was a great satisfaction to me when I joined the Hercules. I expected great things from this promising sailor. But how miserably have our hopes been disappointed!"

All listened to this account of their late comrade with sympathetic interest, and Lieutenant Briant thanked the doctor in the name of his brother officers:

"All the details you have given us about him whom we have lost," added he, "only make his memory the more dear, if that were possible. On you, my poor fellow, will devolve the painful task of breaking the mournful news to his mother. Tell her, when she can bear to hear it, of the esteem and affection we all bore for him."

"And his cousin;" said des Bruyères, thoughtlessly, "for her also it will be a frightful blow. Perhaps she was his fiancée."

"No," replied the doctor, rather drily, "Mademoiselle Hélène Rieux and Caoudal were not engaged. We are speaking in confidence here. Why should I not tell you that Madame Caoudal's great desire was that they should marry, but she was destined to be disappointed in this wish also, for they had flatly refused to lend themselves to the project. Hélène and René were brother and sister, or, rather, their regard for one another was like that of two brothers."

While they chatted thus in the officers' deck saloon, and Commander Harancourt wrote the details of the catastrophe in the log-book, the storm lost its force and soon ceased altogether. A quieter sea succeeded the formidable waves that had subjected the Hercules to so rude an assault. The watch changed at the usual hour; the men on the watch took up their posts, whilst their comrades separated, to seek in their hammocks the rest they so much needed. All night long the cruiser rolled like a cork on the chopping sea. Then, towards morning, it quieted down again, and, when the sun appeared above the horizon, it lighted up a sea as smooth as a mirror. The Hercules pursued her course. She very soon touched at Lisbon, and was able to repair her damages, after which she again put to sea and, in a few days, arrived at Lorient. It was by this time a fortnight since the loss of Midshipman Caoudal, but the sad event was still fresh in the memory of all. Kermadec, well on the road towards recovery, was already able, by the help of a pair of crutches, to hoist himself up on deck.

Doctor Patrice's heart was as heavy as lead at the thought of the task that lay before him with regard to his friend's unfortunate mother, but, with thoughtful delicacy, the commander had desired that she should be informed in this way, rather than by an official despatch from Lisbon.

The pilot had just boarded the Hercules, bringing letters, impatiently awaited by all on board. Suddenly, the commander appeared with a radiant face, and a blue paper in his hand.

"I have good news for you, gentlemen," said he. "Midshipman Caoudal is safe and sound; picked up at sea by a mail-boat from La Plata. Two days ago he was in the hospital at Lorient, and is now convalescent."

THE doctor's joy at learning that his friend still lived was as great as the grief of the past two weeks. What a relief to be spared the sad errand to Madame Caoudal; not to be obliged to face her grief, and that of her niece! And for himself, what happiness to have his friend restored to him; to be able to hope that René would live many years to torment his friends, to frighten them to death by his escapades, and yet to be liked by everybody, as of yore! But did anybody ever hear of such a curious piece of luck? To fall into the sea, in a furious storm, to the depth of a thousand feet, and then to find himself comfortable and calm in the roadstead at Lorient, two days before his comrades The scamp! No one but René Caoudal could have met with such adventures. How they longed to see him! Doctor Patrice lost no time in finding him, and hearing his account of himself. Ten minutes after landing, he entered the room where the midshipman was lying. The first greetings over, he examined the young man carefully, feeling all over him, applying the stethoscope, and interrogating him, to make sure that there was no injury. His examination over, the doctor felt puzzled, for, physically, he was sound enough, and there did not appear to be any reason for his keeping his bed. And yet he could not conceal from himself a singular change in the mental condition of the young sailor. Sad, preoccupied, with pale face, and distrait expression, he evidently found difficulty in fixing his attention, and responded with reluctance to the eager questions of his friend. Truth to say, he appeared annoyed by them.

"What is the matter with you?" said Patrice, anxiously. "You do not seem to be any the worse for your immersion. I must say, I cannot understand why you lie here like a log. Come, make an effort! Take a turn out-of-doors; that will put you to rights in a twinkling."

"Oh! a walk in Lorient!" said he, in a contemptuous tone.

"Lorient is not to be despised!" cried the doctor. "In any case, it would be better than lying here in the dumps, for you are in the dumps; that is evident. Come, what have you got on your mind?"

The only reply was a discouraged shrug of the shoulders.

"Do you feel ill?"

"Ill? No; not precisely ill."

"Then what do you feel like? Have you any muscular pain, or any sprain? How long were you in the water?"

Again René shrugged his shoulders. "How do I know? Besides, what does it matter?" muttered he, impatiently.

And turning towards the wall, he hid his face with his arm, as if to insinuate that the conversation was burdensome. The doctor looked at him with surprise, which rapidly changed to uneasiness. What ailed him? Such a frank and lively fellow, with such an open nature, and so transparent! Had his head struck against a reef at the bottom of the sea? Must he attribute this dumbness, this unusual sullenness, to some injury of the brain?

"How is it; don't you know?" he asked, determined to make him speak. "You must be able to remember what happened when you came to the surface. You were not long under the water, perhaps. How many minutes, should you judge?" A deep sigh was the sole response. "Perhaps you lost consciousness?" René was silent.

"You were found lashed to an empty barrel, if I am rightly informed," said Patrice. "Was it long before you got hold of it? And the rope,—where did you get it from?"

Another shrug of the shoulders, and impatient turn of the head, as if to shake off importunate noise. It seemed as if the voice of his friend grated on his nerves like a saw scraping marble. For some minutes, the doctor pressed questions on him without getting any answer.

"My dear friend," said he, at last, vexed in his turn by this behaviour, "your cold bath appears to me to have had a most unfortunate effect upon your temper. You are not ill, but you are very sulky. If I bore you, say so. I will go away. It is very simple."

He turned towards the door. At this, René appeared to make an effort to rouse himself from his dejection.

"Patrice! Stephen!" called he, "Don't be angry. Come back. You know I am glad to see you. You have no need that I should throw myself into your arms to prove that, I think."

"Confound it! There is a slight difference between throwing your arms around my neck, and giving me such a reception as this, you must own." Rene sighed afresh, shaking his head in a lugubrious fashion.

"Come, let us begin all over again. What on earth is the matter with you, with your sighs and your head-shakings? One would think that you concealed some terrible secret. Have you discovered a conspiracy among the monsters of the deep, or have you heard the sirens sing at the bottom of the sea, and care for nothing but their music?"

To the doctor's great surprise, a deep flush suffused René's pale face, and his eyes brightened, while a smile leaped to his lips. The two friends waited a moment, in silence, looking one another in the face.

"Well, explain yourself, I beg," said the doctor, at length, crossing his arms on his breast.

Rene reassumed his dejected attitude.

"What would be the use?" said he, in a tone of lassitude; "you would not believe me."

"Why?"

"Because, if I spoke, it would be to tell you of such improbable things, so ridiculous, you would never believe me. And you would be right, no doubt, if it were not for one irrefutable proof; one material proof."

"A proof of what?"

"Of what happened to me."

"Where? When? How? You are enough to provoke a saint with your reticence. I have a very good mind to shake you!"

Rene remained silent a moment. Then he took a resolution.

"Here, feel my pulse," said he. "Have I any feverish symptoms?"

"Not a shadow of fever. A cool skin, and a pulse as steady as mine."

"Look at me. Do I look scared? Is my forehead burning? Do I look like a man demented, under the influence of delirium?"

"Not the least in the world. You are like a fine lad, a friend of mine, the prey of an unaccountable mood, but in possession of all his faculties."

"Then, whatever I tell you, will you believe it?"

"If you swear to me that you speak seriously, I will believe it without a doubt."

"I give you my word of honour that what I am going to tell you is strictly true. And yet, I hesitate."

"Well, go along. I never knew any one so suspicious."

"You have never known me in circumstances such as I am now placed in. Stephen, you are my dearest friend; almost my elder brother. I would not deceive you, would I? Besides, to what end? What I am going to tell you is true. It is incomprehensible, but it is true. I would rather keep to myself the secret of this strange adventure, and I had resolved never to speak of it to any one, certain of not being believed. But here you are? You question me, and I have such a habit of telling you everything that happens to me that, on my soul, I will risk it. Who knows? Perhaps, between us, we may arrive at some plausible theory, at some practical conclusion."

Intensely puzzled by this preamble, not less than by the serious and deeply affected expression of the midshipman's face, the doctor took a seat by the bedside, and prepared to listen. René, leaning on his elbow, with a dreamy look fixed on something visible to himself alone, began his story in these words:

"You have not forgotten the circumstances I was placed in when I was washed overboard, on that Monday, the 19th of October. We were in a cyclone, running N.N.E., with a tremendous sea on, and the first thing you all knew was that a huge wave carried me and the gun away with it. Doubtless, a search was made for me, and the vessel was stopped, to wait for me. I know what is the usual thing to do at such times, and, at the moment, I fully expected to be picked up."

The doctor signified by a gesture that all that had been done.

"Unfortunately, or, rather, fortunately,—for if I had been unluckily fished up then, I should have missed an unheard of spectacle,—in falling, an irresistible impulse made me curl my legs and arms round the breech of the gun. The mass of steel was engulfed in the water, and carried me down by its weight. In a moment, I felt the absurdity of what I was doing, and tried to relax my hold, in order to rise to the surface. Then I lost consciousness. So far, nothing remarkable happened. Once, I felt I was almost rescued, but instinctively I clung to my gun, which cut through the water like a flash of lightning. My last lucid thought was that I had come to the surface, and was floating like a dead fish. It is all linked together in my memory; I see now what happened. I see the plunge into the water, I feel the cold of the steel in my arms, and the loss of breath, caused by the rapid dive. Then, for the second time, I lost consciousness. How long did it last? Who will ever know? Where was I? What was this place; this never to be forgotten scene?"

The officer paused a moment, a far-off look in his eyes, and his face pale.

"When I recovered my senses," resumed he, "I was lying on a soft couch. Just at first I was unable to open my eyes; thought came back to me, but slowly; I heard, but without being able to understand what was going on around me, voices speaking in a language unknown to me. At first I lay in a sort of vague languor —a reverie. The voices ceased. Suddenly memory returned, and I thought to myself: 'I must have fallen into the water; I was suffocated. Some one has fished me out.' I opened my eyes with difficulty,—my eyelids were as heavy as lead,—expecting to find myself in the ship's hospital, with you bending over me on one side, brushes and flannels in hand, and my good Kermadec on the other, busy rubbing his officer. And I remember wondering which of our fellows had taken my place on the watch. Instead of the hospital, instead of your faces, this is what I saw: I was lying in the middle of a spacious grotto, the walls of which seemed made of red coral, of the most exquisite shade. A silvery light fell from the roof, displaying a bed of ivory covered with a thick purple texture, as soft as velvet to the touch. Under my head were piled up cushions made of precious stuffs, curiously embroidered.

"The floor of the grotto was covered with the finest sand; and here and there spread magnificent carpets. Ivory seats of antique form wore disposed here and there; also an embroidery-frame of smooth ivory with an unfinished piece of embroidery in it; and a lyre of pale tortoise-shell resting on a pile of rumpled cushions, as if it had been thrown down in haste. In a basket made of rushes I saw wools of faded colours; a roll of papyrus, open. I lay there, bewildered, looking about me, wondering what world I had wandered into, when a sweet voice, as clear as crystal, suddenly uttered an exclamation, I turned my head quickly. How shall I describe to you what I saw? A young girl and an old man stood beside my couch, and appeared to have entered from an inner grotto at the head of the bed. The old man, tall, almost gigantic, was stately in the extreme. He wore round his brow a gold fillet; his long beard covered his breast with snowy waves. Draped in a voluminous mantle of white woollen material, enriched with a border of coloured embroidery, he looked like an antique statue come to life. As to the young girl, I never saw anything so beautiful. She seemed to me a sort of ethereal being, made of the same sort of light as that shed from the roof of the grotto,—tall, upright, slender as a reed. She was clothed in a soft tunic of pale green, the colour of the waves, as you sometimes see them at sunrise. Her fair hair, held back from her face with strings of pearls, fell, in a silken mass, to her feet. Her pure brow was crowned with a garland of sea-weed, and in her clear eyes I thought I saw the spirit of the ocean, herself. She looked at me, then pointing to me with her slim finger, she pronounced a short phrase. The old man replied. I made an effort to hear them, but I could understand nothing they said. If my recollection of the classics,—hazy enough, I must own, —does not deceive me, the language they spoke in was Greek.

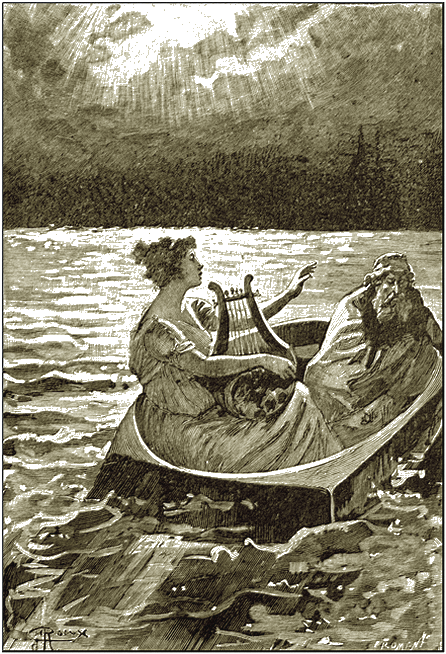

"Meanwhile, the old man came towards me, placed his hand on my forehead, on my heart, and felt my pulse, just as you would have done, my dear Stephen. The young girl, leaning on his shoulder, turned her ravishing face towards me, with an expression half curious, half mocking. I felt that my modern uniform, with its gold lace, and my leather boots, must have had a pitiful effect on this royal couch. You cannot imagine how mean and shabby I felt in the midst of all this luxury, this fairy, archaic, fantastic magnificence. However, my host and hostess continued conversing beside my couch; and by their looks and their gestures I saw that they were speaking of me. The old man looked more and more grave; several times he raised his hand towards the roof of the grotto. It seemed to me that the young girl asked something; playfully, at first; then, getting almost angry. Her charming brow darkened; she frowned, and her limpid eyes flashed. The old man, without troubling himself at this display of anger, signified 'no' with his head in a severe manner. At last, releasing himself gently, but firmly, from the young girl who clung to him, he walked to an ivory coffer, took from it a gold cup, and began to concoct a beverage. The young girl stayed by my side. She watched the old man for a few moments, with her eyelids drooping, biting her lips with a look of anger, which, by the way, in no wise detracted from her beauty; then, all at once, with a charmingly mutinous movement of the head, she smiled, drew nearer to me, and, rapidly slipping a ring on my finger, made a sign common, it seems, to all countries. She laid her finger on her smiling lips; then, running to the cushions piled up near the embroidery-frame, she posed on them like a swallow, and, taking the lyre in her arms, began a song I can never forget.

"Oh, that crystal voice! that strange, unreal music! that fantastic and yet delicious melody! You spoke just now of the song of the sirens, my dear Stephen,—what siren ever sang as mine did then? Looking at her, listening to her, I felt myself living in an unknown world. A singular joy, mixed with a nameless melancholy, suffused my whole being. I could have wished to listen to it forever, or to die, listening to it. The tears rose to my eyes involuntarily; I was transported, and yet I was sad.

"She looked at me, while shedding these exquisite notes across the grotto, and it seemed to me that the rays of her eyes brought the fantastic notes to me. Opposite to her, one of the walls appearing to be of glass, I could distinguish a light-green, like that of the seawater; I got a glimpse of large bodies passing one another in this transparent wall, attracted, retained like myself, by the magic song. Unable longer to endure inaction, I raised myself on my couch, when the old man, returning noiselessly to my side, laid his hand heavily on my shoulder, and offered me a cup of chased gold, filled with a beverage with an aromatic odour.

"I was about to refuse it, when, at a word from the old man, the young girl rose, came towards me as lightly as a shadow, and, with a smile on her lips, offered me the cup. I drank it at a draught. The beverage was of a peculiar but very agreeable taste. No sooner had I swallowed it than I fell back on my cushions as if paralyzed. The young girl began to sing again. Everything whirled round me,—the grotto, its inhabitants, its furniture, the great, strange fishes which passed to and fro near the transparent wall. I fancied I saw the faces of friends bending over my couch,—yours, my mother's, Hélène's, —I shut my eyes to escape from the sensation of vertigo. The crystal voice seemed to die away in the distance. Once more I lost consciousness.

"When I came to myself the morning sun was sparkling on the waves. I was alone. An imperceptible speck in the midst of the vast blue. Firmly lashed to an empty barrel, I floated at random in mid-Atlantic. I spent two days and two nights like that, in a state between waking and sleeping, tortured by heat and thirst during the day, my limbs stiff and cold by night. I should have died without being able to move if a French mail-boat from La Plata had not chanced to pick me up. They brought me here, took care of me, and I should have been well, I believe, long before now, if I had not been devoured with a longing which you will easily understand, and which consumes me like a burning fever, to see my young Undine again."

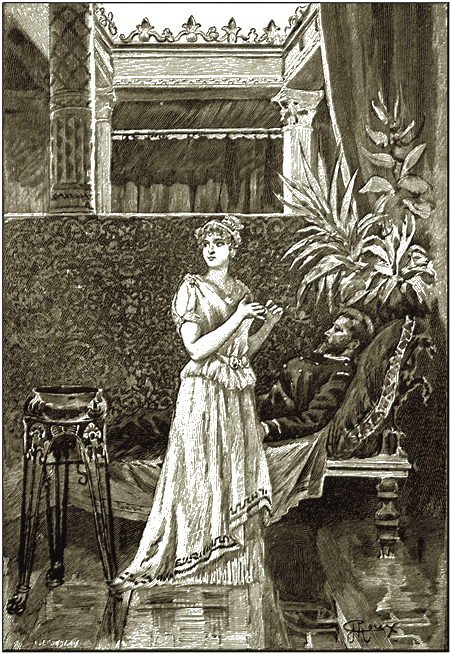

René receiving the ring.

Doctor Patrice listened, at first with surprise, and then with uneasiness, to the midshipman's strange story. Nothing was more natural than that he should, under the influence of a hallucination, caused by fever, exposure to the sun's rays, thirst, and faintness, have dreamed of all these adventures; but, that he persisted in the hallucination, and that he, in good faith, believed all that he said, was a very serious matter, and inspired him with grave fears as to his mental condition. At first, trying to laugh him out of it, and then speaking very seriously to him, Patrice exerted himself to bring his young friend to a more rational state of mind. But all in vain; René refused to abate an inch of anything he had said. He had seen the grotto, the old man, the young girl, and, what was more, he was firmly resolved to see them again.

He would die in the attempt, if need were, but find them again he must and would; he would again hear that fairy music, that siren's song which had bewitched him. No reasoning of Patrice's could shake his determination; on the contrary, it only seemed to confirm it.

"My dear friend," said the doctor, at last, fairly angry, "allow me to give you a bit of advice. It is to keep carefully quiet about all this beautiful adventure, if you do not wish to be sent straight to Charenton! How can you expect people in their senses to believe for one moment in such wild tales?"

"I have no intention of confiding them to any one whatever, you excepted," cried René, not less exasperated. "But, since you are so clever, wait, do me the favour to explain to me whence this ring comes, if it was not Undine that gave it to me."

RENÉ CAOUDAL held out to the doctor his left hand, on which glittered a pearl with a superb setting. Stephen Patrice sat silent for a long time, his eyes riveted on the ring, puzzled, perplexed, with a hundred contradictory theories chasing one another through his brain. Although reason and common sense seemed on the side of doubt, he felt sure, in his character of physician, that René was not delirious. That he was speaking in his sleep could not for a moment be admitted, or that he was inventing the story; his frankness and loyalty to his friend were too thoroughly understood. But over and above the moral testimony of his young friend, there remained this strange token—this ring—which, even in ordinary circumstances, would have struck the most indifferent observer. The unique beauty of the pearl constituted a mystery in itself.

Whence came it? Its purity, its shape, its size, its incomparable perfection, proved it to be a royal jewel, a historic ornament of priceless value, which could not have been stolen and concealed without a noise being made about it, much less worn by the thief, without being very quickly traced. It must have been celebrated, described minutely in the archives of some old mansion. The mounting was, if possible, more marvellous than the pearl. Cleopatra herself could not have dissolved and swallowed one more choice. Patrice was somewhat of a relic hunter, like many others in these modern times; but he had, in a degree that few others can have, that artistic sense so common among children in his birthplace, the south of France, where it seems as if sculpture, painting, music, singing, eloquence, and the belles-lettres grow spontaneously. He instinctively recognized a work of art, and experience had taught him to class it with certainty, to attribute to it, without hesitation, a date, a school, a country. But here, with this chef-d'oeuvre in miniature before him, he was completely nonplussed. Was it Greek art? Doubtless. But Greek, strictly speaking, like the words of the young girl and the old man, which sounded like Greek to René, "though he did not understand a word," it certainly was not. He had never seen this style of ornamentation anywhere. It did not belong to the dawn of Grecian art, nor to its meridian, nor to its decline; he could find none of the essential features of the Doric, Ionic, Corinthian or Neo-Greek schools. He could not give a name to the marvellously chiselled faces in the setting right and left of the imperial pearl.

No animal, no bird, no kind of fossil reembodied by science was represented here. The chimera, that strange creation of the ancient imagination, could not have suggested the design, for the singular feature of it was the expression, even more than the form, of the face. Whether it was the likeness of a veritable creature, or the capricious symbol of an obsolete creed, it was impossible to say. The material, of which the mounting was composed, was another subject of perplexity. It was impossible to decide whether it was metal, wood, or stone. One would judge it to be metal. But was it gold—silver—platinum? No. An unknown combination? Perhaps. It resembled nothing he had ever seen. It was altogether an enigma, Between the artist that had conceived it and those who at the moment contemplated it there was an abyss,—an abyss of time, of space, of religion, of thought, of genius, of race, of language, of manners. That was evident.

"One might think that it had fallen from another planet," said the doctor, involuntarily.

"You think so!" said René, "I felt sure I hadn't dreamt it. But whether I was inclined to believe or disbelieve it, of one thing I am now perfectly certain,—that what I have told you of my doings has been seen and lived; I am as certain of it as I am of my accident on board the Hercules, and of my own identity. There! you may say what you like to the contrary. If I had any doubts, what can one say in answer to this tangible proof?"

"I don't know," said the doctor, thoughtfully. "If only there were an inscription," added René, turning the ring about.

"An inscription! At the time in which this jewel was engraved I should be surprised to hear if they had recourse to our means of writing. Believe me, the arrangement of these faces constituted in itself a phrase legible to her for whom the ring was destined."

"To her for whom it was destined," repeated René, in a dreamy voice. "Ah, if you had but seen her, Stephen, you would no longer be surprised at the ring, wonderful as it is!"

Stephen Patrice examining the ring.

"Possibly," said the doctor, nodding his head; "but, if I may say all I think about it, I should not like to see you musing too much about these experiences of yours. I do not pretend to explain that which I do not understand, and I do not deny that which is beyond me. There are mysteries that may be good and safe to sound; but this does not appear to be one of them. Siren or mortal, goddess or daughter of the Evil One, I do not admire your goddess with her mysterious beverages and her enigmatical hospitality. Take my advice; put this ring away somewhere, or, better still, throw it into the sea, like the ancient who must have done so long ago, as a propitiatory offering to the gods; turn your back resolutely on these reminiscences which can only trouble your brain; cease to look into an unknown sphere, and fix your thoughts on things nearer home."

"Never!" cried the midshipman, indignantly, "Never! I? How can I forget this vision? No, my friend, I would not if I could. Look here! You speak of throwing it away and yet you are fascinated by it; you can't take your eyes from it; your hand is held out, in spite of yourself, to take it again. Never mind, the power which ordains that I shall find these mysterious beings again, the attraction which draws me towards them, is more imperious than you imagine. I must see them again and their submarine home. I must learn their secret, and obtain their confidence, so that I may establish communication with them."

"You must, above all, get up your strength," said the doctor, a little alarmed at this outbreak of excitement. "You should go to your mother and get better. Do you not see that all you have gone through has tried you severely, and, before attempting any fresh adventures, it will be necessary to get a little flesh on your bones?"

"That is true," said René, seriously. "To succeed in any enterprise whatever, one must first make provision in the shape of health and strength. I have a good mind to ask for leave, and to get away to 'The Poplars,' as soon as I am free."

"'The Poplars!'," repeated the doctor, in a melancholy tone. "Ah, René! how is it possible that any other image can efface the one you will find there?"

"What," said the middy, in an amused tone, "are you going to take part with the rest? You mean Hélène. How many times shall we have to beg our friends not to try to make us happy in spite of ourselves!"

"Your mother would be so pleased to call her daughter."

"But that matter is settled," said René, laughing. "Don't you see that it is absolutely impossible? Even if I could adorn with idealistic virtues the playfellow with whom I have grown up, with whom I have exchanged hard knocks on the head, and uncomplimentary home-truths, I dare not propose such a thing to her. Poor Hélène! she deserves a better fate than to be forced into a distasteful marriage. But, happily, she is not the sort of girl to allow any one to choose for her. And besides," added he, not without a spark of malice, "unless I am much mistaken, she will not have to go far to find an admirer far more satisfactory than I."

"By the way," said the doctor, abruptly changing the subject, "have you heard from Kermadec?"

"Certainly," said Caoudal. "The lad was allowed to see me as soon as he arrived at the hospital. He has even more need of rest and change than I. Do you know what I've been thinking of? To take him with me to 'The Poplars.' He is alone in the world. Mother and Hélène know him through my letters, and I am sure that he would enjoy himself there."

"A capital idea," said the doctor. "If it were not in your service that he was wounded, it is not for want of wishing it. His one grief was at having survived you, as he thought, and to have done nothing to save you. You have made a devoted friend there."

"With very little trouble, t am sure. But the friendship is reciprocated. Kermadec has rare qualities, but the simplicity of a child. His naivety and credulousness expose him to the worst influences."

"Those he will meet at 'The Poplars' can only be of the very best," said the doctor. "It is an understood thing, then. With his consent, which will not be difficult to get, we will ask for a double furlough. You go to recruit your strength together in the country air, and I will find time to pay a flying visit to 'The Poplars.' Do you know that yesterday I was ordered to serve on anything but a cheerful errand?—the mission of going to inform your mother—"

"That her René had served as breakfast for the crabs?" said the midshipman, in a tone which belied the levity of his words. "Poor mother! Bah! Let us think no more of that. It is all over now. Make haste and get your furlough, and come and join us as soon as you can."

A FORTNIGHT later, on a smooth lawn in the beautiful grounds of "The Poplars," gently sloping towards the banks of the Loire, might have been a party of young girls in light dresses, and young men in striped flannels, engaged in a game of tennis. At a little distance in the background, near a red brick house, which had no pretension to be called a mansion, but which was of the simple and beautiful proportions of a comfortable modern dwelling, the older people were chatting round a tea-table. The mistress of the house, with her sweet face, and beautiful white hair, was occupied in paying hospitable attention to the wants of everybody. Madame Caoudal was radiant. She had her René with her, the object of her continual thoughts, her pride, her hope, the only one spared to her of all those dearest to her, By a happy chance the cruel extremes of mourning and of joy had been spared her motherly heart. No one had been in a hurry to impart to the poor widow the death of her only son; so that she heard, at the same time, of his accident and of the unexpected turn of fortune which restored him to her. Even with this happy dénouement, she had been much shaken, and her young favourite and counsellor, Hélène, had much difficulty in cheering and comforting her. The tearful mother had exclaimed against the cruel sea, which had robbed her of so much, and which would hardly let her keep her only son. But Hélène had hastened to point out to her that René was, after all, safe and sound, and, for that matter, to die in bed is less glorious than at sea (witness those neighbours of theirs upon whom their roof had suddenly fallen one night), and that it was all the greater pleasure to see him again after his terrible adventure.

Whether her reasoning was bad or good, it succeeded in raising her aunt's spirits; and, moreover, when she saw her René again, the best and handsomest son in the world, according to the excellent woman, she forgot her troubles. Tall, athletic, with a proud poise of the head, a martial bearing, frank and commanding eyes, his movements supple and graceful, René Caoudal was, in truth, a fine young sailor; one to satisfy the most exacting motherly pride. He returned, it is true, somewhat thin and pale, but that did not make him the less interesting to the young folks assembled to do him honour. On the contrary, among the tennis players, there was a remarkably increased assiduity in according him a gracious welcome. But apart from the ordinary courtesy due from him to all the guests as son of the house, not one of them could flatter herself that she received particular attention from him. In vain the freshest of toilets had been put in requisition; in vain the most flattering words and rippling laughter had been discharged at him; they read in his preoccupied look, his voice, his gestures, in his manner altogether, a sort of absent- mindedness.

"He isn't like the René that he used to be," said little Félicie Arglade, between two blows of her racquet. "He is changed somehow on the voyage! He has no eyes or ears for any one but Hélène."

"After such terrible dangers," put in Doctor Patrice, quietly, "with whom should he wish to talk but his cousin, his old playmate?"

"For my part, I have never believed in these marriages between cousins," said Félicie, in a still quieter voice.

"But why are you in such a hurry to marry them?" inquired Mademoiselle Luzan, a tall, fair; sweet looking girl with a grave expression. "If I know Hélène, M. Caoudal is the last person in the world it would enter her head to marry."

"Why are they always whispering in corners then?" retorted Félicie, somewhat softened.

"They are not whispering!" protested Mademoiselle Luzan; "they are chatting confidentially. And what is there remarkable in that? Do you not know that M. Caoudal has just narrowly escaped death? Wouldn't you, if you were Hélène, be anxious to know every detail of his adventure?"

The cousins.

In reality, without any one being able to accuse them of whispering, as Félicie said, it was evident that Hélène and René had plenty to say to each other; and it was not, in truth, surprising that those who were not in their confidence should infer something strange. And how came it that Madame Caoudal, who had heard the whole story from him, and Stephen Patrice, who had heard it first, were neither of them recipients of these later confidences? Why was Madame Caoudal so radiant and Doctor Patrice so doleful? Was it that one of them saw the realization of her hopes, and the other, that which he had so long feared?

"This accident has touched their hearts and drawn them together," said the good lady, "Sometimes good comes out of evil."

"Undine will have to give way to Hélène," thought the doctor, sighing. "Well, so much the better! It wouldn't do to play the part of the dog in the manger, and one ought to rejoice in one's friends' happiness." They were both a little hasty in their conclusions. The subject of these confidences between the cousins, which they pursued in the woods, at the river bank, in the drawing-room, and at tennis, was the inexhaustible discussion of the details of René's adventures. On his return home, in the midst of the excitement, and the tearful joy of his mother, he had not been able to restrain himself from telling the whole story to her and to his cousin. For the subject had been tacitly ignored between him and the doctor, Caoudal having felt that his friend, if not hostile or sceptical, showed at least marked repugnance to encouraging him to speak of it.

As time went on, he became more and more animated and possessed by it, and, as the need of speaking and acting became more imperious, he showed that his heart was filled with thoughts of his mysterious acquaintances. Madame Caoudal appeared not incredulous, but displeased, cold, and even severe; she begged him seriously never to mention the subject in her presence again. Hélène never said a word, but her sparkling eyes spoke volumes; and when René, disappointed and perplexed, sought support and sympathy from her, she made him a sign to change the subject. "Later, when they were seated under the great poplars which gave the name to their home, she explained her attitude:

"No need to torment auntie with the account of this wonderful adventure, or to let her brood over the projects that I understand," said she. "You know what a grudge she bears to the sea; it is like a personal hatred between her and the liquid element. I believe she really thinks it a cursed power for evil. After the great sacrifice which she made in allowing you to enter the navy, we ought not to distress her any more than can be helped. If she believed, if it were possible for her to realize, that the depths of the sea, as well as its immensity, attract and claim you, that you feel called to the perilous honour of exploring unknown, mysterious, it may be deceptive regions, she, poor, dear soul, could not live. Spare her that distress.

"She has forbidden you to speak to her of such things. Obey her implicitly. As for me, I enter henceforth into all your plans; you know I have always shared your ambitions. Sometimes, nay often, I dream that I, too, pursue the glorious career of a sailor; I feel through my hair the vivifying air of the vast expanse; I fancy myself commanding a vessel; I see myself facing, with our brave seamen, the fury of the gale, landing on unknown islands, discovering new plants, new animals, new wonders, changing the aspect of geographical charts—and I wake—Hélène Rieux, as before!

"Do not think that I complain of my lot! But I admire and revere the glorious profession of my grandfather, of my uncle, and of yourself, and I shall be as proud of your exploits as if they were my own. All this is enough to show you that for these projects, still unformed, still indistinct, you should not seek any confidant except myself. You cannot be too careful. One only understands perfectly what one loves; and I feel strongly, myself, that nothing but a peculiar, hereditary influence could induce me to believe unhesitatingly and with absolute certainty in your veracity. Like other people, I see much that is incredible in your adventure, and yet I believe in it. That which convinces me is not, as with Stephen, my confidence in your good faith, the conviction of your clear-headedness, or even the proof of the ring. No, it is 'the eye of faith' voilà tout. It seems to me that it must be; because when one is a born explorer, one goes straight at the discovery; because you have been called to see that which others could not see. In short, I believe, because I believe!"

Nothing could be more satisfactory than a confidant of this sort, and René was not less anxious to tell than she to listen. Away with the false conclusions of Madame Caoudal, of Dr. Patrice and of other friends! Hélène and René, like accomplices, continually felt the need of some mysterious confabulation. Either René had omitted to give in detail some one perfection of his goddess, or else Hélène had some new hypothesis to suggest, or wished to be told over again some forgotten circumstance. And, above all, there was the increasing importance of the question:

How to find the enchanting abode of these august personages again? How to find the time, the means, of attempting it? How to do all without awakening any suspicion on the part of Madame Caoudal? Hélène was firmly resolved on two points: to spare René's mother all uneasiness, all useless anxiety; and to encourage, as far as lay in her power, that which she considered to be the fulfilment of a duty, a chosen mission.

RENÉ was too clear-headed, and had been too long accustomed to weigh things in his mind with mathematical accuracy, not to have endeavoured to account for his immersion and subsequent adventure by simple and natural causes. He started with the following premises: First, I am not the sport of a hallucination, since I have in my possession a priceless and unique ring. Second, The old man and the young girl whom I saw in the wonderful grotto were not phantoms, because there are no such things as phantoms. Third, They are living beings, placed, by some combination of circumstances of which I am ignorant, in extraordinarily peculiar conditions of existence, at some hundreds of feet beneath the surface of the ocean, since the marine charts show in this region of the Atlantic a depth of not more than one thousand feet. And the habitation of these real and living, but abnormal beings? Clearly a grotto, or series of grottos, extending under the sea, and borrowing the necessary respirable air from air-holes on the top of some rocks on a neighbouring island.

Such was the only reasonable conclusion he could arrive at. And it brought him by an easy transition to the question as to whether chance had not put him in the track of a great discovery, or at least of a great historical verification,—that of the ancient continent, now lost sight of under the ocean, which the tradition of the earliest times locates between Africa and South America; a sort of huge island, formerly analogous to Australia, long since submerged, and of which Madeira, Teneriffe, the Azores, and the Antilles are the only remains or landmarks now visible. As to the existence of this Atlantic continent, on the other side of the Pillars of Hercules (that is to say the Straits of Gibraltar), and of its disappearance during some great cataclysm, the historians, geographers, and philosophers of antiquity are all agreed. Plato speaks of it often in his writings. He gives us the source of the tradition which he hands down, and which is assuredly not without authority: it was his grand-uncle Solon, the Athenian legislator, who received from the Egyptian priests of Saïs a description of Atlantide, as they called this mysterious land.

To what branch of the human race did the Atlantes belong? On this point, tradition is less clear. Some have thought that they were an indigenous race which probably invaded Europe (that is to say Greece), and were opposed by the feeble resistance of the Pelasgi, the ancestors of the Greeks, Others believe, on the contrary, that Atlantide was a Greek colony, perhaps one of those founded by Jason and his companions on their search for the Golden Fleece. But all these writers are agreed in stating that Atlantide disappeared some thousands of years before the present era, and that the shallows, the banks of marine grass known by the name of "The Sea of Sargasses," the peaks and the islands of this region, are, in some sort, the ruins of a submerged continent.

So much for the summary, but positive, indications gleaned by René from history. He knew, moreover, that the navigators of the fifteenth century believed in the existence of Atlantide. Christopher Columbus, for one, endeavoured to find his way to the Indies by going westward, with the conviction that he was sure to find, at various distances apart, the islands surviving from the great continent, which would serve him as places where he might put into port by the way. The discovery of the Azores and the Antilles justified, in a great measure, this idea, based, as it was, on traditional geography.

All the soundings made during the last half century, notably those by Admiral Fleuriot de Langle, in the part of the Atlantic between the twelfth and sixtieth degrees west longitude, show, moreover, a region literally "paved" with shallows, reefs, and sandbanks. In short, the actual conclusions drawn from the physiography of the globe forbade him to doubt any longer the possibility, and even the probability, of these facts relative to Atlantide and its disappearance. Considerable changes have been and still are produced, under our own eyes, in the configuration of sea and land, such as the sundering of the land at the Straits of Dover, which is of comparatively modern date. The coast of Normandy, too, was encroached upon by the sea, shortly before the Carlovingian era, and nothing was left above high-water mark but the Channel Islands, and, even in our own day, the Island of Santorin, in the middle of the Mediterranean, has disappeared from view.

Then new islands have appeared, while, in the far east, frightful inundations have changed, in a few days, the physiognomy of the Japanese Archipelago. It is well known, also, that America was in primitive times much less extensive than it is now; that the enormous basin of the Amazon, that of La Plata, Florida, Patagonia, Louisiana, and Texas, are lands but recently abandoned by the ocean. In a word, there are endless proofs in evidence of the fact that the surface of the globe is ceaselessly changing, sometimes by the slow and continued action of winds and waves, sometimes by the sudden effect of some great local disturbance.

René was able, therefore, without imprudence, to admit as certain the fact that an Atlantic country had been submerged beneath the ocean, and to connect this historical known quantity with the indelible remembrance of his submarine sojourn near the Azores. The more he looked into the subject, the more sure he felt that the old man and the young girl were Atlantes, veritable Atlantes in flesh and blood, surviving the wreck of their country. How? By what mysterious means? By what refined artifices? By what superhuman power? He could not tell, and he would not risk useless hypotheses in this regard. But he was certain of one thing; what he had seen once he was determined to see again; to bring to light this mystery; to elucidate, perhaps, a great geographical problem.

Why not, after all? Why not embark voluntarily, systematically, and with his eyes open, on this voyage which a sea wave had already unconsciously accomplished for him? Why not descend once more of his own accord to the scene he had left in an inanimate condition, and come and go at his own pleasure? René made up his mind to attempt it. And so, as he was accustomed to do thoroughly what he did at all, he asked himself, to begin with, by what means he could exchange ideas with these Atlantes, supposing he were fortunate enough to find them. At any price, he must avoid the blunder of knowing that they were discussing him, without being able to understand what they said. What language did they speak? The conviction was impressed more and more upon him that it was ancient Greek.

This conviction was corroborated by their surroundings, their furniture, by the character of their garb and their attitudes, and became a certainty one evening when he was talking to himself, aloud, about that which occupied his thoughts night and day. He had just mechanically articulated some of the sounds he remembered to have heard in the grotto: "Pater, agathos, thugater."

The next thing to do was to hunt up his old classic school-books, to open the Iliad and the Odyssey, and to search feverishly for these same words.

All at once scraps of Greek, long dormant in his memory, awoke from their sleep. The old roots of Claude Lancelot shone before him, in blazing characters, and he surprised himself muttering, as in former days: "Pater, father; apater, without a father; agathos, good, brave in war; thugater, the daughter is called—"

Oh, charming roots! What delicious rhapsodies! How René enjoyed these phrases that he used to anathematize in his schoolboy days! He found out now what had made the study of Greek so difficult, before he had heard the accent of his host and hostess,—musical cadences as different as could be from the stammering attempts at pronunciation at college. But, henceforth, he would know better. By comparing other words of the same order as those with whose rhythm his ears were familiar, he could form an approximate idea of the way to pronounce them, and from that he was able to proceed to other classes of words, related to the first in various directions. He soon got as far as creating for himself, in every instance, a system of accentuation, and, as the result was harmonious, he concluded that it must be the right one. At the same time, he threw himself, heart and soul, into the study of the vocabulary, of syntax and flexions of every kind. And, above all, he attacked the roots, those delightful roots, which are the key to the language, and of which Rollin justly says that they impart "an incredible facility to the intelligence of authors."

He was now always to be found, book in hand, repeating to himself one or other of these simple phrases : "Meli, honey, sweet to the taste. Melissa, mellifluous insect." He could not keep up these exercises without Hélène's remarking it. She wished to know what it was all about; René explained, and, forthwith, she also became enamoured of the study of Greek, and, like a gardener, busied herself with these fascinating roots, and rivalled René himself in her ardent cultivation of them.

They never came across one another, without firing off a volley at each other. Greek seemed to be in the air. In the corridors, in the garden, in the field, the winged words flew about: "Aazzô, I breathe, I aspire, etc." So much so, that Kermadec, in his turn, wishing to imitate his officer in everything, and gifted, moreover, with a prodigious memory, caught the contagion. He was heard, muttering to himself, as he polished the copper pans: "Agele, great drove of oxen."

Doctor Patrice, though protesting against it for form's sake, allowed himself to be attacked by the epidemic, and could not resist the satisfaction of showing that he had not entirely forgotten his classical studies. Madame Caoudal, alone, remained impervious to the general craze, and asked, throwing up her hands, what was the matter with them all, that they spoke from morning to night in such a language.

Meanwhile, René did not neglect the practical part of his programme. He surrounded himself with all the charts and documents which might help him to solve the problem. He had, on mature reflection, delayed his projects. The first question was, not to find associates, forces, materials necessary for the execution of so fantastic an enterprise ; he must get an extension of leave and permission from his mother to spend the time of that leave at sea. During this interval, he received his promotion to the rank of lieutenant. This was no more than his due, since, for the last year, his name had figured on the roll for promotion, for "distinguished services." The first and immediate effect of this promotion was to facilitate the accomplishment of his projects, and he obtained, without difficulty, the necessary three months' freedom.

Madame Caoudal's consent was more difficult to get. But what cannot one achieve with a little perseverance and diplomacy? Worked upon by Hélène, the good lady was induced to confess that, after all, if René wished to employ his leisure in taking a voyage of discovery on his own account, there was no reason why she should oppose it. The young officer now began with all speed to prepare the ways and means for his voyage. He had for the last three weeks been in regular correspondence with some one unknown to the rest of the household. The faithful Kermadec carried the letters to the post-office in the town. For this purpose he went continually backwards and forwards between Lorient and "The Poplars," proud of serving his officer, big with importance, ready to be cut in pieces sooner than betray a secret, about which, by the way, he knew nothing. It ceased to be a secret when, one morning, René, seating himself at the breakfast-table, handed his mother an open letter, which he begged her to read. The Prince of Monte Cristo had invited him to spend a few weeks on board his yacht Cinderella in order to discuss some new and curious ideas he had formed concerning the flora of the African coast. Everybody knew that the yacht Cinderella had been engaged for several years in sounding in shallow waters. It is a superb boat, commanded by the proprietor in person, and splendidly furnished for the researches he pursues. Many celebrated savants have received his hospitality on board the vessel, and have reported their explorations to the Academies, and registered them in the papers. An invitation to spend several weeks on board so illustrious a yacht could not fail to be considered by Madame Caoudal as a great compliment to her boy.

She certainly did sigh at thought of his sacrificing the rest which he seemed to need; but the satisfaction of knowing that René was about to distinguish himself in a pacific enterprise softened the pang of parting. She therefore, without much persuasion, gave the required assent.

A week later, the young lieutenant, escorted by Kermadec, took the train for Lisbon, where the Cinderella awaited him.

THE Cinderella (Proprietor and Commander Hereditary Prince Christian of Monte Cristo, the twenty-sixth of his name) was an auxiliary yacht of five hundred and thirty tons. She was schooner rigged, but had also a single screw with engines of three hundred and fifty horse-power, and carried sufficient coal to enable her to steam at full speed for twenty days. Her speed by steam in fair weather was about a dozen knots; but the speed could be considerably augmented by sailing when the weather was favourable. The exterior of the vessel showed a pointed hull, long and light, suggesting the motion of a well-bred horse. The fine proportions of her rigging, the perfect adjustment of her timbers, which enhanced a simplicity full of elegance, struck René's practised eye at the first glance, inclined though he was by his profession to despise mere pleasure boats as inferior productions. To all appearances, the crew, in its perfect discipline, was copied from that of a man-of-war. The young lieutenant noted with satisfaction the frank and open faces of the men, an unfailing characteristic of men-of-war's men.

The planks of the deck shone with cleanliness and all the brass was as bright as gold. The officer who received the prince's guest was less satisfactory than the rest of the yacht. He introduced himself as Captain Sacripanti, second in command of the yacht: He was a little man, short and stout, with black hair shining with pomade, a showy necktie, a double watch-chain ornamented with lockets, and his fingers covered with rings; he looked in fact more like a Neapolitan valet than a seaman. His accent, too,'was that of a flunkey. He was one of those people of doubtful origin, who speak very badly, and with a coarse voice, all the languages of the Mediterranean countries.

Bowing very low, and showing a double row of very white teeth, he offered to conduct the young lieutenant to the commander,—an offer at once accepted. On going aft, René passed, one after the other, a saloon, a smoking-room, a dining-saloon, and a library luxuriously furnished. His guide knocked discreetly at the door of a state-room. "Come in," cried a voice of thunder. The "second in command" slid open the door in its groove and effaced himself to allow René to pass. "Lieutenant Caoudal," he announced in a solemn voice. Upon this, a tall figure emerged from the depths of a monumental arm-chair, and, throwing on a round table the newspaper which he was reading with the aid of eye-glasses, came, with outstretched hand, to greet him:

"My dear M, Caoudal, how pleased I am to see you!" he cried, effusively. And he pressed the young man's hand within his own, as if he were greeting a long-lost friend. He almost embraced him. Without manifesting any surprise, René expressed to him the pleasure he felt, on his side, at making the acquaintance of the Prince of Monte Cristo.

"Well! do you know, I see we shall get to be as thick as two thieves, upon my word," cried the prince in an explosive manner, when René had finished speaking, "To begin with, I must tell you I am a very outspoken person. If people please me, I tell them so to their faces. If not,—well, I am equally plain with them. And I like you,—I like you very much. I am positively enchanted to make your acquaintance; enchanted to have you on board for a time; enchanted to find that our work interests you, and that you wish to take part in it. I hope you will enjoy being with us," continued he with great volubility, paying not the slightest attention to the few polite words the lieutenant felt bound to utter. "If you are not satisfied with anything, you must tell me so, plainly, and I will endeavour to alter,—not my yacht, that would not be practicable, but, at least, I would see that things are rearranged to suit your taste. I wonder how you would like to look over my little wooden shoe, as I call my yacht. Ha! ha! ha!"

Falling in with his host's noisy, hilarious mood, René declared that he was quite ready to look over the "shoe." The prince, putting on a huge cap, led the way, and showed him every corner of it, from the deck to the hold, not omitting any detail. René was bound to admit that everything, outside and in, was perfect of its kind. Nothing was wanting which could be useful for the scientific work that the prince had undertaken; photographic studio, carpenter's shop, forge, physical and chemical laboratory, all seemed admirably organized. Two or three dozen workmen, directed by foremen, occupied these various workshops. The prince said in his guest's ear, in a stentorian whisper, that they were the pick of jolly fellows, and he "liked them extremely; otherwise he would tell them so squarely, and show them the way out."

His highness's appearance was truly extraordinary. Physically, he was a veritable Colossus; tall, broad in proportion,— aldermanic proportion,—very red in the face, with prominent eyes and a large aquiline nose, or, rather, enormous beak, which gave him a fantastic resemblance to a parrot. He had a ringing voice, and gesticulated a great deal; his laugh was Homeric in its amplitude; and his manners, as we have seen, were exuberantly cordial. He affected an openness, a frankness bordering on bluntness. An incessant talker, he used a hundred words where ten would have served. But what struck René at the outset was the philosophical disdain he professed on all occasions for the sovereign rank to which he was born. It is true his principality consisted of nothing more than an islet, two or three hundred acres in extent, whose chief industry and sole source of revenue was an argentiferous lead mine, worked by seven or eight hundred convicts, which he let to a neighbouring nation. If he was to be believed, he cared for nothing in the world but personal merit. He affirmed that the meanest scavenger, if intellectually endowed, was worth more to him than an emperor on his throne. One would have thought that he wished, by this ostentatious display of principles, to excuse himself for having been born some fifty years previously heir to a large fortune as well as a princely crown. At least he had the good taste to spend a good third of it in useful scientific work.

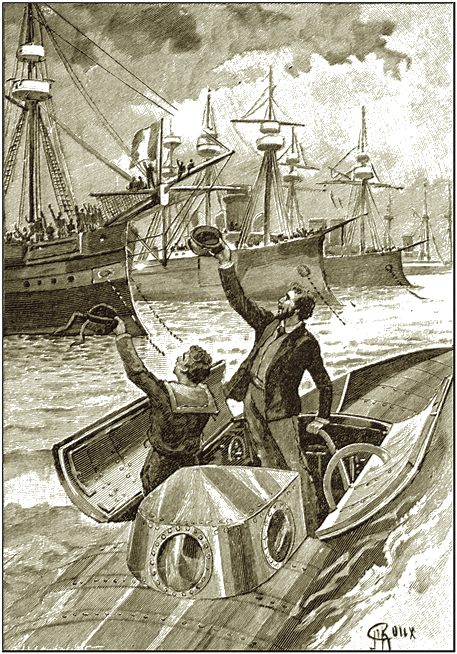

On board the "Cinderella."

"I look upon myself as a steward," he volunteered. "My fortune is not my own. I only manage it for the benefit of those who have none. As to my name! bah! what is that? As the immortal Shakespeare says, 'A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.' I protest to you that I attach no importance whatever to it, and that I would as soon go by the name of Big John, as Monte Cristo." But he never missed an opportunity of reminding one of the twelve hundred years of ancestors more or less authentic. In five minutes René knew him through and through. Ridiculous though he was, he could not dislike him, and the prospect of spending a few weeks on board so charming a vessel was not to be despised. The prince insisted on himself showing him to his cabin. It was most elegant and commodious, and opened on the library. He begged the young fellow to consider himself at home, and to tell him if he would like anything altered to suit his convenience. René assured him in all sincerity that he had never been so comfortably lodged, and they went up on deck the best friends in the world.

The object of the present voyage of the Cinderella was to sound some of the Atlantic shoals, and René lost no time in asking to be shown the apparatus to be used for the purpose. The investigation had an interest for him little dreamt of by Monte Cristo, who took him at once to the place where it was standing ready for use. It was an enormous block of lead, weighing twenty tons; round its upper extremity was coiled a solid rope of measuring silk, which Monte Cristo pronounced, not without pride, to be five hundred yards in length.

"You see," said the prince, much pleased at being able to play the showman, "our monstrous plummet is hollowed out at the base, and has a coating of grease. When it has lain long enough at the bottom it is slowly drawn up by means of this windlass; it reappears covered with shells, gravel, grasses, débris of all sorts which it picks up in dragging along at the bottom of the sea. It is by studying the nature of this débris with the magnifying-glass that we draw our conclusions concerning the kinds of vegetable and animal life (often new to us) concealed in, these beds under water."

"Indeed!" said René, surprised and disappointed, "have you no other method of research?"

"Why, no, my dear fellow! What more would you have than a plummet like mine? What do you find defective in it?"

"Nothing in itself, certainly. It is a superb plummet, but, if I may be permitted to make a suggestion, it is that another machine, somewhat akin to it, be used for examining the sea-bottom."

"But what sort of machine would you suggest? Would you have me send a photographic camera a thousand feet under water? And by what means, may I ask?"

"A camera? no."

"What, then?"

"A man! Yes, I confess, sir, I should not have asked to join in your researches, if I had not indulged the hope of going myself to the sea-bottom. I cling to the hope of seeing, with my own eyes, what goes on down there, and all the shells that could possibly attach themselves to the largest plummet in the world would tell me absolutely nothing! The least glance in person would serve my purpose."

"He, he!" and the prince went off in an explosion of laughter. "I dare say, my young friend; I, too, should like extremely to see, with my own eyes, what is going on among the fishes. But just one thing stands in my way, you see. It is impossible, simply impossible!"

"Why impossible?"

"For a very good reason; namely, that we make our soundings at such depths that we could not possibly provide our divers with a respiratory tube long enough, and, if we sent our men to explore the depths, what steps could we take to provide them with air to breathe?"

René reflected a minute before replying.

"It is clear that the difficulty of providing respirable air is the only thing that stands in the way," said he, at last. "Well, if we cannot make a tube sufficiently long, we must think of some other expedient, that's all."

"Hum, ha! let us see," said the prince, crossing his arms on his ample chest.

"Look here; it will be necessary, according to my idea, to contrive a special diving apparatus; an apparatus for shoal soundings. If only a supply of respirable air, sufficient to last for three or four hours, could be assured to the diver! Round the suspension cable a telephonic wire should be coiled, which should keep the explorer in communication with those on deck, so that he could be drawn up as soon as he gives the word, and, in case he gave no sign of life after a given interval, he could be drawn up, without losing a minute, by means of a steam-engine."

"Do you know, that is the most ingenious plan I ever heard of!" cried the prince, enchanted, "only we have no such diving apparatus."

"That is true."

"What, then?"

"We must invent one. Haven't you here, on board, complete workshops, and first-rate workmen?"

"Certainly; there are none better than mine, I flatter myself."

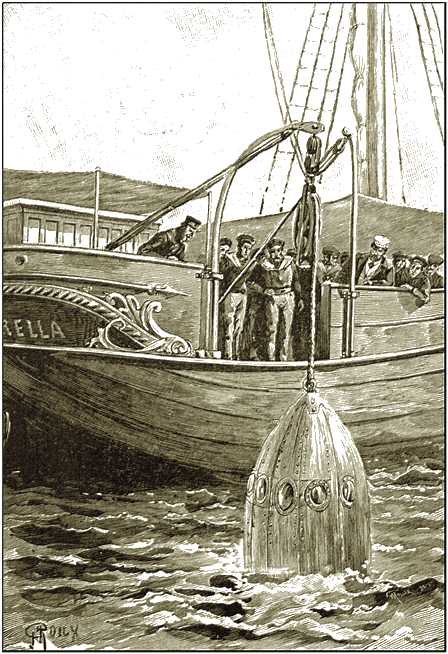

"Very well; with your permission, I will at once set to work in the library, and begin to work out my plan of a diving apparatus, and I hope, before long, to make drawings exact enough for your workmen to construct a most satisfactory one."

"If you do that, I really must embrace you," cried the prince, enthusiastically, foreseeing, already, the reports that would be addressed to the learned societies, and the interest that would be connected with his name. "If you succeed, upon my word! I would willingly give you a year or two's revenue of my principality."

"I would not ask for so much as that," said René, laughingly; "only allow me to take my first journey in it alone, when it is completed, and to choose myself the site of my soundings, at least, to begin with."

"Assuredly, my dear boy. You shall do just as you wish. When will it suit you to begin?"

"As soon as we set out."

"Bravo! And you wish to sail towards—?"

"I particularly wish to explore the region of the Sargassian Sea. When we arrive at the point where 25° E. longitude crosses 36° N. latitude, we will make a halt, and proceed to sound."

"Oh! Ah! You have decided ideas; that is clear. And what do you expect to discover at that exact spot? Plenty of driftwood, no doubt. What else?"

"Experience has taught me, indeed, that the sea is covered at that spot with a quantity of sea-wrack, which the savants call fucus natans, and our sailors, very aptly, tropical grapes, or gulf-wrack. It is a sea plant, the stalks of which terminate in watery bladders. But what does it matter? All that will only bore you, I fancy—"

"Indeed, your diving apparatus will disturb such a movable carpet. Well, sir, you have only to command. The library and the workmen are at your disposal, and I will at once give word as to our route."

And the prince went off, leaving his guest in a high state of satisfaction as seeing himself on the way to find his mysterious Undine. And, as the yacht weighed anchor and set sail, the young officer shut himself up in the library, where, thanks to considerable ability in drawing, and with the help of the necessary technical books, Indian ink, coloured crayons, compass, and drawing-board, he soon produced (on paper at least) the apparatus of which he dreamed. He made more than twenty copies before succeeding to his satisfaction, and, at last, handed to the workmen a plan which seemed to him to unite all the wished-for conditions, and, under his directions, the work was carried out in the workshop.