RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

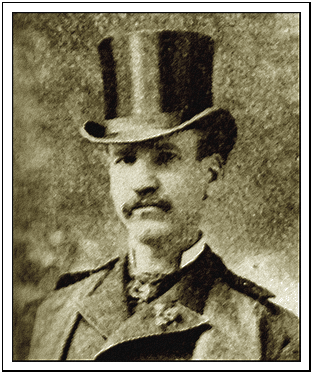

Robert Duncan Milne (1844-1899)

THE Scottish-born author Robert Duncan Milne, who lived and worked in San Fransisco, may be considered as one of the founding-fathers of modern science-fiction. He wrote 60-odd stories in this genre before his untimely death in a street accident in 1899, publishing them, for the most part, in The Argonaut and San Francisco Examiner.

In its report on Milne's demise (he was struck by a cable-car while in a state of inebriation) The San Fransico Call of 17 December 1899 summarised his life as follows:

"Mr. Milne was the son of the late Rev. George Gordon Milne, M.A., F.R.S.A., for forty years incumbent of St. James Episcopal Church, Cupar-Fife. and nephew of Duncan James Kay, Esq., of Drumpark, J.P. and D.L. of the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright, through which side of the house, and by maternal ancestry (through the Breadalbane family), he was lineally descended from King Robert the Bruce.

"He received his primary education at Trinity College, Glenalmond, where he distinguished himself by gaining first the Skinner scholarship, which he held for a period of three years; second, the Knox prize for Latin verse, the competition for which is open to a number of public echools in England and Ireland, and thirdly, the Buccleuch gold medal as senior and captain of the school, of the eleven of which he was also captain.

"From Glenalmond Mr. Milne proceeded to Oxford, where he further distinguished himself by taking honors, also rowing in his college eight and playing in its eleven.

"After leaving the university he decided to visit California, a country then beginning to be more talked about than ever, and he afterward made the Pacific Coast his residence. In 1874 Mr. Milne invented and exhibited in the Mechanics' Fair at San Francisco a working model of a new type of rotary steam engine, which was pronounced to be the wonder of the fair.

"While in California Mr. Milne for a long time gained distinction as a writer of short stories and verse which appeared in current periodicals. The character of his work was well defined by Mrs. Gertrude Atherton, who said:

"'He has an extravagant imagination, but under it is a reassuring and scientific mind. He takes such a premise as a comet falling into the sun, and works out a terribly realistic series of results: or he will invent a drama for Saturn which might well have grown out of that planet's conditions. His style is so good and so convincing that one is apt to lay down such a story as the former, with an anticipation of nightmare, if comets are hanging about. His sense of humor and literary taste will always stop him the right side of the grotesque.'"

A caricature showing Robert Duncan Milne and a San Francisco cable-car.

DURING the week which followed the Sunday on which I accepted the invitation of Major Titus to dinner, and afterward witnessed his extraordinary construction of the spherical lens and mirror, the latter of which unfortunately burst before the conclusion of our planetary observations, as detailed in the Argonaut of August 27, I again ascended the bill to the major's house toward evening, and was pleased to find him at home.

"I am glad you have come to-night," said the major, after shaking hands, "since, as I have finished my business here, I intend to rejoin my family at the seaside to-morrow, and shall probably not return for three or four weeks. We should, therefore, have missed the present most favorable opportunity of examining the principal planets en masse as it were. You have dined? Come in, then, and take a glass of Maraschino. I am just finishing my dinner," And he led the way into the dining- room.

"Yes, it was somewhat unfortunate," he remarked in answer to an allusion of mine to the bursting of the mirror on the last occasion. "It was all my fault. Accidents will happen, you know. This time, however, we will take more care, and begin earlier—a little after midnight. The superior planets are now westering rapidly, through being daily left further and further behind by the sun."

After spending the evening in billiards and piquet—the major was an adept at both—about midnight we adjourned to a species of laboratory, where my host proceeded to mix the glutinous substance in the mortar as on the former occasion, adding the various powders and solutions of the different fluorescing bodies whose nature he had previously explained, until the composition attained the proper consistency and chemical character, when we adjourned to the roof, I carrying the spirit-lamp as before, and he the mortar. We wheeled the cabin containing the receiving lenses and screen into position for commanding the planets, some of which were already rising in the east, and then went to work to inflate the monster spherical lens upon the roof of the cabin, which was successfully accomplished as before, as also was the inflation of the quicksilvered spherical mirror on the roof of the house.

"Now," said the major, when all the preparations had been completed, "we shall presently have the choice of Neptune, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, or Venus to inspect first, as we please. Saturn you saw when you were here last. Uranus is just now nearly in conjunction with the sun, and, therefore, invisible, Nor are the conditions favorable for viewing Mercury. If you wish to begin with Neptune, we will do so, but I warn you that this, the outermost wanderer of our system, has been dead for an infinitely longer period even than Saturn, and will only present you with a similar aspect of awful desolation. Uranus, on the other hand, exists, I must infer from his appearance, under totally different conditions. Instead of being dead and frozen, like Saturn and Neptune, as one might predicate from the position of his orbit, intermediate between those two, he is still the repository of life—weird, gigantic, and grotesque. There are certain evident peculiarities in his atmosphere which I have not yet been able to determine, though I am at present engaged in constructing an instrument which, in connection with this telescope, will give their analyses when he next becomes suitably situated for observation. These peculiarities seem to consist in an appropriation of the actinic properties of the sun's rays, weak as they are at that immense distance, so as to render them nearly as effective as on our own planet. You know the difference between the actual heat at the top of a high mountain and in the plain below. Given a vertical sun, on the mountain you might freeze, while on the plain you would stifle to death, all of which goes to prove that heat is the result of what is styled the actinic action of the sun's rays upon the atmosphere. In fine, the property of the atmosphere of Uranus is such as to secrete heat in sufficient quantities for the preservation of life. There is also another remarkable peculiarity about Uranus which makes one sorry that you cannot see him. I have discovered that his poles are in the plane of his orbit—that is to say, to use a familiar metaphor, instead of revolving on his axis, like the other planets, after the manner of a top, he rolls round our central sun wheel-fashion. His four satellites follow suit, and revolve round him, like all normal moons, in the plane of his axial rotation. Then it comes to pass that one hemisphere of Uranus—that directed toward the sun—is always in perpetual summer and perpetual day, while the opposite hemisphere is necessarily consigned to eternal ice, and night, and death. There are no seasons, though there are gradations of temperature—the sun, at the pole, seeming to describe a circle of small diameter around the zenith in the heavens every eighty-four years, while to an observer at the equator he seems to wheel perpetually round the horizon. Even at the distance at which I inspected the planet through the binocular, I could detect indications of vegetation and of living things, before whose size the sixty and eighty-foot proportions of our primeval monsters would pale into insignificance, judging from their relations to the calculated measurement of the soil they inhabit. But my strongest binocular magnifying lens of two hundred diameters was not sufficiently powerful to disclose more than this, and I am now having another constructed of eight hundred diameters, which I shall bring to bear upon Uranus next month, when he becomes a morning star. I presume, therefore, that you will prefer to go on with the examination of Jupiter, in which we were disturbed on the last occasion, and as the night is remarkably clear, I will screw the two-hundred-diameter power upon the binocular, which will bring the planet to an apparent distance of somewhat less than thirty miles."

Having done this, the major went out to adjust the spherical mirror, leaving me in the cabin to focus the image on the screen. After numerous fixed stars had crossed the field, the same broad band of light that I described before came sweeping upward from the bottom. I focused the receiving lens rill the edge assumed a sharp outline, and then, sitting back in the easy chair, brought the binocular into play. At first my eyes could not grasp the nature of the scene presented. It was of a grayish-white hue, and seemed to be endowed with a motion of its own, independent of the motion of the image across the screen. Gradually I became convinced that I was gazing on a rolling sea of vapor—mist it might be called- -completely concealing the surface of the planet. Besides the upward motion of the image across the screen, and the sluggish involuted movement of the vapor masses among themselves, there was a slow lateral movement from right to left. This served to assure me that the flattened polar regions of the planet were passing beneath my view. The contemplation of this drear expanse of grayish clouds was growing monotonous, when suddenly it seemed as if a thousand cyclones had burst forth with incredible fury, and the clouds were driven to the left of the screen with tremendous velocity. I felt that I must have reached the border of one of the equatorial belts, and knowing that a sphere of nearly three hundred thousand miles in circumference, rotating in ten hours upon its axis, must produce a terrific analogy to our own trade winds, I was not unprepared for the violence of the spectacle. Viewing a cloud hurricane, rushing at the rate of thirty thousand miles an hour, at an apparent distance of thirty miles, was indeed calculated to impress me with a sublime conception of force to which nothing on this little globe of ours is comparable. Then came a rift of calm in the body of the belt, and I perceived that I was gazing through the clouds upon a vast expanse of sea. I involuntarily reached for the pinion of the receiving lens, and refocused it, for I saw that the planet and its surface sea were many hundreds of miles below their nebulous envelope. A sea of glass lay beneath my gaze, presenting a weird contrast to the atmospheric war which raged above it. Not a ripple disturbed the surface of this placid, inert, iron-gray waste of waters. The entire scene looked cold and cheerless, and I confess to a feeling of relief when the impetuous hurricane of vapor again monopolized the scene. This was succeeded by a period of calm, the cloud masses seeming to roll in sluggish convulsions among themselves, till the advent of another hurricane, even fiercer than before, convinced me that the equatorial belt proper of Jupiter was now passing over the screen. Then, as suddenly, came another rift in the envelope, and as the same cheerless sea came into view, I strained my eyes to try whether I could detect any trace of life therein. Had there been such, I could scarcely have detected it at the distance of thirty miles had it not been of the most gigantic kind. I hailed the major outside, and questioned him on the subject.

"I am in the same uncertainty as you are," he replied, "until I procure my new power. My impression, however, is that Jupiter contains specimens of oceanic or amphibious life not dissimilar to that which peopled our own earth in the watery epoch, though I have no question that the reptile progeny of this monster planet exceeds our own primeval brood in the same ratio as his bulk does ours. Moderate heat implies slow development; slow development, size and longevity. Moisture contributes to the propagation of gigantic forms of life. I shall not be surprised to discover some notable saurians, and perhaps birds, with my new power, though I have as yet detected no trace of land. That, however, may be easily accounted for, owing to the comparatively small area of the planet's true surface visible through the clouds. Still I am not sanguine as to the existence of continents of any size, since, as you are aware, the density of Jupiter is but little greater than that of water; and this fact, combined with the abnormal distension at the equatorial region, occasioned by the enormous centrifugal force excited by so vast a sphere rotating at such a tremendous velocity, seems to point to the conclusion that oceans, perhaps many thousands of miles in depth, cover the major portion of the planet."

While he had been speaking another cloud hurricane had swept across the screen, and been succeeded by another narrow rift of calm. Again gazing on the placid waters below, I became aware of some dark object which seemed to move upon their surface. I riveted my eyes upon it, and felt that I could not be mistaken. Here, now, was something to which I could adjust my focus much better than to clouds or calm water, and so I readjusted the receiving lens and likewise the eye-pieces of the binocular. The object gained sharpness and distinctness. It was evidently a living thing of some sort, and I knew it must be of immense size to be visible at a distance of thirty miles. I called out to the major, telling him of my discovery, and asking him to come and look at it.

"No," said he; "since you have been so fortunate as to discover this object, creature, or whatever it is, make the most of the opportunity for observation. I dare not leave this mirror for an instant, or the scene would instantly pass from the field of vision, never to be recovered, I shall take extra pains to regulate the focusing, so that you may have uninterrupted means of observation."

I did not let my eyes leave the object for a moment, and presently the concentration of my gaze, as is frequently the case, rendered my vision clearer. There it was—an animal, toiling, floating, undulating on the surface of the water, if water it was, for it seemed to have rather the consistency of oil, and its smoothness served to impress me more strongly with the idea that the Jovian sea must possess constituents not found in our own oceans. I carefully moved my binocular on its tripod so as to keep the monster thoroughly in the field of vision, and for as long a time as possible. Gradually it resolved itself into a creature most unmistakably of the saurian tribe. The tapering muzzle, the long tail were perfectly defined, and left no room for doubt as to its identity. In place of legs, however, it possessed enormous fins or wings on either side, articulated like those of a bat, which were raised and depressed alternately, and served to propel the monster through the water It seemed as though I were watching the slow evolutions of a nondescript tadpole in a pool a good many yards off. I followed with intense interest the progress of this monster, which kept slowly plowing its course, with alternate strokes of its side fins, evidently toward some definite point, and I caught myself wondering how long it would be before this living thing, endowed with organs of locomotion adapted to its surrounding circumstances, and possessed of a purpose, would encounter its mate or its prey; and what it would think if it knew that another living being, on a body which (owing to its angular proximity to the sun) it could never see, even were it endowed with human eyes and human intelligence, was watching it attentively more than four hundred millions of miles away, I was abruptly roused from my reverie by the sudden disappearance of the object from the screen, and, taking my eyes from the binocular to ascertain the cause, found that I had unconsciously followed its image as it slowly moved to the border, where, of course, it vanished. I lost no time in returning my binocular to the centre of the field, and though I saw more of the eddying cloud masses and dashing equatorial cyclones, I was not lucky enough to inspect the surface of the Jovian sea through a rift again. When the planet passed naturally from the screen, I got up and went out.

"The spectacle was extraordinary," observed the major, as I described the creature, "but I was not wholly unprepared for it. It was, in fact, just what I should have expected. Still it is marvelous to consider the immense size of this reptile. It was as if you were looking at it at a distance of about thirty miles with the naked eye, you must remember. A creature visible at that distance must have been many hundred feet, aye, yards, in length. I dare say we should not be wrong in estimating its length at half a mile. But then it is only natural that a vast sphere, like Jupiter, should give birth to a gigantic brood in their prime; for I question whether Jupiter will have progressed so far toward its decadence for thousands of millions of years yet as to fit it for the higher forms of terrene life. Light a cigar, and we shall take Mars next, when he gets a little higher in the heavens. There is too much aberration when bodies are examined near the horizon. The war planet is at present very favorably situated for examination, being nearly in quadrature, and accordingly not more than sixty millions of miles away. With the higher power he will seem as if seen at a distance of about six miles with the naked eye."

When Mars at length gained altitude, I returned to the cabin, while the major busied himself in attending to the reflector. After the usual lapse before the adjustment of the focus, I had the satisfaction of perceiving the usual band of light invading the screen, and lost no time in regulating my binocular. I at once recognized the arctic regions of the planet, which are designated as "ice-caps" in the chart of Dawes and the orthographical projection of Proctor. My acquaintance with the geographical peculiarities of Mars, as mapped out by these distinguished astronomers, enabled me to determine accurately what portions of the planet I was gazing upon first. I instantly saw, and my previous experience caused me no difficulty in comprehending, that the supposition of modern observers, reasoning from analogy, to the effect that this planet is constituted similarly to our awn, is correct. I saw with satisfaction that the seas which were projected on the screen were veritable water, with a hue as greenish as those of any terrestrial ocean. At my apparent point of observation, I could distinguish the ripple upon their surface, as the "wavy-twinkling smile of ocean" played beneath the beams of a noonday sun. I strained my eyes to detect ships, aquatic monsters, or signs of life, but without success. I moved my binocular so as to sweep successively what I felt tolerably sure were the Maraldi Sea, the Madler continent, the Secchi continent, and Dawes's ocean, and as my vision rested on the land I became aware of the true reason of that ruddy appearance which Mars presents even to the unassisted eye. The soil seemed covered with a species of dark reddish vegetation, resembling the hue of an autumn forest. I could plainly distinguish vast bodies of trees, stretching over thousands of square miles of land; immense plains, profusely clad with rose-colored herbage; rivers now bounding over awful precipices, and now meandering placidly along between their colored banks. Anon clouds obscured the scene, and I felt convinced that physical conditions so nearly resembling those of our own planet must contribute to similar results in the production and propagation of life. I became the more convinced of the sufficiency of this reasoning by the resemblance of the vegetable kingdom, and strained my eyes with renewed interest to detect any trace of animal life or intelligent mechanism. As I leisurely scanned the area of the Madler continent, I suddenly saw spread beneath my gaze— cropping out, as it were, from amid a tangled mass of scarlet undergrowth—the unmistakable ruins of masonry. Irregular blocks of gigantic stone, evidently hundreds of feet in cubic measurement, lay strewn over miles of country. Furrowed, and scarred, and seamed with the action of wind and water, these gigantic ruins, by whose side the piles of Persepolis or Carnac would seem the work of pigmies, lay in weird and sad confusion. "The remains of a ruined city," I thought, "reared by intelligent beings. If there exist ruins on this planet, why not the abode and work of a living race?" and I again narrowly scrutinized the configuration of the soil. Here and there scattered over the face of the country I espied similar ruins, imbedded in similar vegetation, but though I used the utmost care, I could detect no sign of life, no animal, no living thing. Seas and straits, rivers and meadows, passed successively beneath my gaze, but whatever of life there was lay only within the domain of the vegetable kingdom. I pondered on so extraordinary a circumstance, as scene after scene passed beneath my ken, and was again only roused from my reverie by the disappearance of the surface of the planet from the field of vision. Hereupon I went out, and addressed the major on the subject.

"I have," said he, "witnessed the same scenes you speak of, and have only been able to come to one conclusion regarding them. It is this: There are two epochs in the natural history of a planet at which it is wholly relegated to the sway of the vegetable kingdom—viz. its infancy and its decadence. The existence of these gigantic ruins, choked up with vegetation, points out that Mars was once the abode of intelligent beings. Masses of masonry, such as are still extant there, would outlast the assaults of time and the atmospheric influences which are still going on, for many thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands of years. 'The flowers will blow, the rivers flow' for thousands of years to come, and perhaps afford satisfaction and sustenance to some lower forms of animal or insect life which have outlived the higher. It is quite probable that the tides will rise through solar action and the lunar action of the two lately discovered satellites, for millions of years to come, just as well as if they were noted and marked by rational beings. The seas will roll upon the sands, will gradually eat up some continents and leave others bare, for countless years to come, though no one watch them. Physical forces are independent of rational life, and in fact have no connection with it, though life is altogether dependent upon them."

"But surely," I remarked, "this planet must have been a theatre for the acts of a wonderfully gigantic brood, judging from the piles of masonry we saw. Creatures such as we are could not have handled such ponderous masses."

"I think you are mistaken," said the major. "You must remember that the force of gravitation at the surface of Mars is less than here, in about the ratio of three to one, and that consequently mechanical and engineering feats such as could not be achieved here would be comparatively easy of accomplishment there."

"But to what do you attribute the extinction of animal life upon this planet?" I asked.

"I think it is due to the fact," returned he, "that Mars is considerably more distant from the sun than we are, was consequently formed first, and is older. His small bulk, as compared with ours, is sufficient reason that his central fires should have cooled down much earlier than ours, and this deprived him of that internal heat which is necessary to vitality. Add to this that the sun's action is not nearly so powerful there as here, and I think we have sufficient reason for not being surprised at this spectacle of a decaying planet —not indeed dead, like Saturn, but still on the high road to dissolution, which is probably not more than a few billions of years off yet. We shall now, if you please, inspect Venus, whose condition will still further impress you with the diversity of the bodies composing our system; after which we shall have time to survey the moon, which will presently rise, as will also the new comet, which latter is a most fit subject for investigation, since I have not yet had an opportunity of observing any of the eccentric fraternity."

—Robert Duncan Milne, San Francisco, September, 1881.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.