RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing

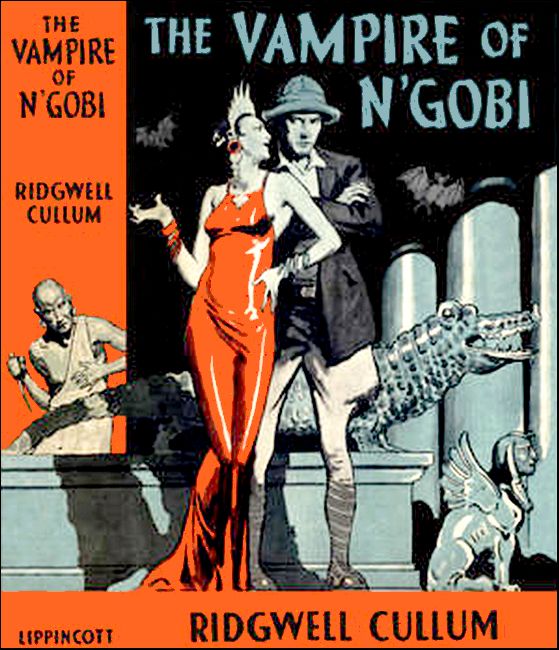

"The Vampire of N'Gobi,"

J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1936

"The Vampire of N'Gobi,"

J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1936

"The Vampire of N'Gobi,"

J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1936

A thrilling story, packed with fast-moving action, telling how Col. "Dick" Farlow traced out the mystery of the ancient race of savage yellow men who lived near the great mountain, N'Gobi, somewhere in the center of Africa. When Dick receives a map showing him how to reach the secret hiding place of the tribe and their seductive queen, he starts off from England, accompanied by his faithful servant and friend, Larky. In their launch, especially constructed to withstand the attacks of the fiercest savages, they take with them an African tribesman who has served Dick before, a man whose only desire is to kill as many of his fellow men as possible. The intrepid three venture far into the hills and encounter appalling horrors and dangers until at last Dick meets Queen Nita, the Vampire of N'Gobi. Even then it seems as if they will never emerge alive. How they face these savage yellow people and what they find in this amazing country is one of the most exciting stories that Mr. Cullum has ever written.

THE story here set out is entirely a work of imagination. It has been written without purpose other than entertainment. It contains no portraiture of any person or persons, living or dead. Neither does it contain any representation of any business organization that ever existed. If any title has been applied to any business organization, in the process of the story, which may have counterpart in real life anywhere in the world, it is due to the inadvertence of chance selection, and is entirely without intent to represent such business.

The story is founded entirely on recollections of ancient ruins existing in Central Africa, which, in the course of trading expeditions, the author not only encountered but explored in an amateurish way. And on the curious geological fact that provides Africa with a network of flowing underground rivers.

The "caverns of Umdava" in the story are an expression of many of the vast water caverns in which Africa abounds, a number of which the author has found it possible to enter, while yet possessing insufficient hardihood to attempt real exploration.

While Zimbabwe in Southern Rhodesia has created no little controversy in archaeological circles, there are a multitude of monuments, deep buried in the heart of Africa's remoter jungles, far more enlightening as to the higher civilizations which have flourished when the world was thousands of years younger.

—The Author

THE heat was intense. It was oven heat. The sort for which the city of Kimberley became notorious from the moment the first sheets of corrugated iron took possession of its roofs and walls. It was nearing noon. And the burden of the city's life was something Hadean.

Kimberley, in the earliest eighties, was frankly a city of makeshift. It was not alone in its design and building. It was in its life. In its complete disregard of spiritual and man-made law. An iron city, it was without soul.

It had, however, individuality. It lured with irresistible fascination, asking no question, and wholly unconcerned for credential. It simply absorbed, digested, and flung out its waste. For its morals matched a sanitation whose foulness involved a night-army prowling its unlit streets.

If Kimberley possessed no soul, there were those who regarded its open market-place as its heart. A mart which had advanced nothing since the old-time Boer farmers had founded it. Like the rest of its iron-clad body, it was quite inflexible in its mundane purpose. It afforded no more than lip-service to the commonest forms of honesty. And every day saw its well-defined lanes, between well-stocked booths and stalls, and tented ox-wagons, crowded with a throng of unscrupulously chaffering cosmopolitan humanity.

Every colour and almost every race found place in its traffic. Colours ranging from sun-blistered white to the ebon of Basuto. Tongues were a chaotic confusion. And fashions ranged multi-hued from Victorian frills and amplitudes to the scant utility of the hide moocha of pristine savage.

Despite oven-like temperature, the market's life was athrill with the sweating bustle of traffic and bargain. Even to its uttermost fringe, a remote corner, where the auction of an emigrant's fantastic personal belongings was in rapid and harshly vocal progress.

The auctioneer was a small Hebrew. He had the emaciated cheeks of ill-health or debauchery. But his sickly features were lit by the quick, bright eyes of undaunted spirit and racial acumen. Alternately wheedling and jesting he produced a flow of salesman's patter like to the stream of the eternal brook. And his magic was reaping a rich harvest.

The owner of the wares was there close to the elbow of the gesticulating salesman. He was big and lean, and youthful. He was darkly good-looking. He was buttoned in tightly-cut tweeds in the London fashion of the moment. He was oozing sweat under the fore and aft peaks of a "deer-stalker" cap. And a none too clean, high, starched collar was already wilting. He remained quite impervious to any discomfort.

It was the bidding for his goods that completely preoccupied him. He was watching the eager throng gathered about the many lots spread out on the sun-baked ground, and the manner of it was hard, and cold, and calculating. A careful note was made as each sale was completed.

It should have been pathetic, this dispersal of an adventuring youngster's last assets. But somehow Lionel Garnet invited no pity. Young as he was he displayed a cold indifference which utterly forbade. He simply watched his salesman lynx-eyed. And he knew a keen satisfaction as prices soared far above original costs.

Lionel Garnet's final triumph was reached when a young Boer farmer claimed a stout chest of bright, new, carpenter's tools. They had cost some eight or ten pounds. The salesman banged one fist into the palm of the other at a bid of twenty-five pounds.

Lionel Garnet forgot the gnawings of a breakfastless stomach. He forgot weeks of weary tramping of red-hot roads, questing livelihood and finding only cold unresponsiveness. He had lost the overshadowing of an unpaid board bill, and concern for his next night's lodging. His whole mind was given to the sums in his note book, and a harvest of cash that was to find place in his empty pockets.

Ben Marta's hotel was a landmark in the older Kimberley. It was also known widely under a less flattering designation.

Ben's economics were his own. And they were based on a passionate desire for profit. His bar, being fundamental of his traffic, was designed for capacity and the simplification of earnest drinking. His requirements in his barmaids were by no means original. He asked for speed that was not necessarily confined to physical activity.

Gladys fulfilled Ben Marta's ideal. She was generously figured, and complete with Victorian curves. She bejewelled liberally, as became a diamond city. Her facial work possessed the dashing art of the painter who substitutes the pallet knife for the brush. Then she had a warm sort of enveloping heart, which, if it aggravated her frailties, possessed a powerful profit-earning appeal with the more youthful who came within the orbit of her good-natured smile.

It was mid-afternoon, when Kimberley worked or slept. Gladys was in sole service at the bar. She was leaning appropriately. And she was smilingly regarding a lone customer across her counter.

Lionel Garnet pleased her. But just now her good nature was troubled.

"How'd it go, boy?" she enquired, with an eye on the long brandy and soda she had just served. "Usually a kango or 'Billy-stink,' eh? Mamma's outfit must have realized well to run to B. and S.?"

Garnet held up his big glass to the light. He drank thirstily.

"Didn't know there were so many English sovereigns in the world, Glad," he replied contentedly, setting his glass back on the counter.

"Oily Abrams 'ud talk the coppers out of a Penny Bank," Gladys admitted.

"Don't forget he had the goods to sell." Garnet's black eyes framed a cold smile. "Never saw such stuff. Didn't know I'd got it myself, till I unpacked it."

The girl watched him drink again. She decided it was all too greedy for his years.

"I don't know," she sighed regretfully. "Like selling keepsakes. You wouldn't get me selling the clothes off my back, neither. Your poor Ma's sitting back there in London, or somewhere, thinking she'd given you all you need to help you along in the life she made for you. Expect you haven't a stitch but what you're standing in now. I don't know. Men are queer. You wouldn't get a girl doing it. And now, I s'pose, you'll blow it all on that stuff."

Garnet considered the girl's troubled eyes. They were very attractive.

"No," he assured indifferently. "I need it for business. They won't let me work for a wage, so—"

He spread out his hands. Gladys saw they were shapely, and free from any sign of heavy toil. She looked up into the cold eyes and speculated as to the mischief behind them. A boy. Just a nice, big kid. Probably with the sense of a rabbit.

"Twenty or so, ain't you?" she asked abruptly.

Garnet refrained from reply. And Gladys mocked with a smile:

"Still packed in swaddling clothes. Or you wouldn't be drinking brandy and soda," she added.

"You'd like it to be mother's milk, I s'pose," Garnet jeered back, as he finished the remainder of his drink. "You're a dear, good sort, Glad," he went on quietly. "You mean well. But you run to heart in a city that never heard of things of that sort. What's troubling, my dear?"

"You said business. Just what does that mean?"

Garnet leant his big body on the counter.

"What does a fellow usually mean?" he asked. "Make profits, of course. Make a living. The thing they won't let me make working with two hands."

There was harsh bitterness in it. A snarl that transformed good looks.

"And they'll skin you like a silly rabbit." The retort exploded. "Gracious, boy, haven't you any sense? This city's a cesspool. And the only thing to be found in it is human muck. Bank your sovereigns and forget 'em. Get on to the road again. And wear out the soles of your London boots till some one'll let you do the work you say they won't. I've known Kimberley since the Boers grew mealies on it, and I tell you the sharps'll leave you hungry in a week if you flash your stuff. I tell you I don't like to see a nice boy riding to hell at the gallop. Leave the drink alone. Even when you're thirsty. Try water. Leave the bars like they were pest houses. There's no honest living in Kimberley without using two hands. Besides—"

Garnet grinned cold mockery.

"You're nervy, Glad," he said. "Too much indoors. You want to get out in the air, and laugh, and play. You're built for that. Much too pretty to stand there lecturing a boy when you ought to be snatching his money. You make me want to pillow my head on your bosom and weep. Give me another 'Protestant.' I've a desert thirst. And I mean to quench it now I've got the money. Besides—what?"

Gladys goggled angrily. She snatched his glass, set a fresh one, measured brandy closely, and prised the cork of a large soda.

"Right," she said, "I'll snatch before the sharps get it."

There was a moment while the girl's soft eyes glanced over the long empty bar.

"Ulmar Niebaum was in here this morning," she announced in a tone of unconscious awe. "Emmie Smith's his mash. She served him. I was dusting down."

Garnet's swift glance Hashed over the edge of his glass as he drank.

"Don't know him," he said, after a moment.

"Well, you're going to."

"Why?"

Garnet set his glass down.

"And you don't know I.D.B. either, I s'pose?" the girl challenged.

"Illicit Diamond Buying? Don't be silly."

Gladys was wiping the boy's first glass.

"Then you do know Niebaum. He's it. Chief detective."

"Well?"

"He asked Emmie if you were around." Again awe had crept into the tone. "Who you were. What game you were up to hanging round Malta's."

"Well?"

It was harsh. But Gladys felt Garnet was unimpressed.

"You give me a pain in the stay-busk," she complained snappily. "Emmie said you were out on the market selling up your mamma's outfit to pay your board bill. You were new out from England. You were a kid looking for a job to give you three meals a day and a place to sleep. And Niebaum told her, with that grin that's like a she-cat's. Said: 'You tell him Kimberley's no place for fellows hanging around bars. If he can't get a job —best get out. It's safer!'"

Garnet's eyes sparkled.

"He can go to hell," he snarled, with a lift of the lip. "Let him mind his damn business."

"Which is sending folk with rabbit sense to build a breakwater for—years."

The gracious shoulders lifted. Garnet's second empty glass was swept away and plunged into the water tank under the counter.

"You make me savage," Gladys went on in disgust. "What's the use trying to help a feller without sense? Don't say I never told you. When Niebaum starts asking questions it's time to wonder what's back of them. You watch that 'business' of yours. Niebaum's got about one idea of business. If you aren't working with your two hands you're buying stones, that haven't been registered, from someone without a licence to sell. And if you don't happen to be buying them he'll see you do. I tell you, boy, there's many a man, woman, and kid down there on that breakwater who're no more I.D.B.'s than I am. And it's Niebaum who found 'em their jobs. He's hell's angel is Ulmar Niebaum and Emmie Smith can have him for me."

Gladys was completely awed by the terror of the new I.D.B. laws in the hands of Niebaum. The man was a frank agent provocateur. The trap stone offered cheaply to innocent and guilty alike. A method which appealed to a ruthless Teutonic mind. But Gladys had misjudged the youth she sought to save.

Lionel Garnet possessed unusual character. He possessed keenness of purpose and shrewd observation. Gladys was warning him out of the sheer kindness of her emotional heart. And he had absorbed her warning very completely.

His decision was taken on the instant. The girl's warning had been swiftly given. And it took Lionel Garnet the least possible time to liquidate his outstanding board bill and remove himself from the precincts of Ben Marta's notorious hotel. He forthwith betook himself to stifling, cheap lodgings in the corrugated iron home of an elderly widow in a remote part of the city.

But his main purpose remained unchanged. His decision had been coldly taken. It was almost as though the forced sale of his possessions had shattered his youthful ideals. He made no pretence of seeking honest employment. But, instead, flung in his lot with those whose wits were their stock in trade. And which they exercised nightly in the brilliantly lit bars of the Angle Hotel.

Had he desired to avail himself of it a secret defensive organization operated amongst his new associates. But Garnet saw risk, even deadly danger, in so doing. He would travel alone. If Niebaum had marked him down an intended victim he would stand the racket, and defend himself with such wits as he possessed. Then the idea appealed to a nature unusually headstrong. And soon he found himself actually looking forward to the great detective's attentions.

But oddly enough the Angle Hotel did not appear to come within the orbit of Niebaum's operations. Perhaps its clientele knew the game of the trap stone too well. Perhaps, even, it was not safe ground on which to trust a diamond of any sort. In any case, for weeks Lionel Garnet found respite. He remained entirely unmolested, unapproached.

Then came the late close of a long night's gamble when Garnet's luck had been phenomenal. It was a perfectly straight game in a company of unscrupulous tricksters. Garnet had acquired astuteness and skill far beyond his years. He had drunk with scrupulous moderation. And, somewhere about an hour short of dawn, he was leaving his playground to return to his modest lodgings uplifted by the knowledge that, after weeks of outgoings, his original capital was not only intact, but had been augmented by nearly forty golden sovereigns.

The loose cash weighed heavily and pleasantly in a trouser pocket as he bade his envious companions a cheerful good night. And so he passed out of the comparative brilliance of lamplight, and plunged into the unredeemed darkness of Kimberley's night.

A hundred yards or so from the hotel. And then:

"H'st, baas!"

The hotel lights were faint behind him when Garnet received the challenge out of the void. There had been no sound. No stirring. Not even the rumble of a night-soil cart on its unsavoury mission. He had been closely hugging the deeper shadow of the roadside, where the iron buildings lined it.

He halted. Peered. And all his big body was alert and ready for action. It was a Kaffir hail. And he understood. Niebaum was at work. He chuckled inwardly as he thought of the fulfilment of a good-natured woman's prophecy. He was even glad.

He became aware of a dim outline. Of human warmth. Of odour.

"Groot klip, baas! Ja! Ten poun'. You buy? Big groot klip! Ja!"

In the inky darkness a tiger grin lit the youth's cold eyes. Yes. Niebaum. So crude. So clumsy. He wondered where the eager, secret watchers were stationed.

He reached into his coat pocket and produced matches. Pie struck one. The light revealed the weazened features of an aged, diminutive Griqua. It was a poor, mean body he could have felled with a blow.

"Show me!" he ordered. And he struck a second match, which flamed up in the still night air.

A clenched fist out-thrust. But it remained closed.

"Ten poun'," the Kaffir reiterated.

"Show!"

The fingers relaxed cautiously. They opened slowly. A largish, dull, uncut diamond revealed itself in the crumpled palm.

Garnet lit a third match. "Five," he bargained.

"Ten poun'," was the Griqua's dogged grumble. Garnet reached. It was swift in its surprise action. "Let me see," he cried.

And he snatched the stone that was all too readily yielded.

It was all a part of Garnet's long considered plan of action. With the stone in his possession his arm flung back to throw. It was a valuable gem. They always were, those trap stones. He would throw it far into the night. And Niebaum would make a double loss.

But Gladys was right in her estimate and awe of the hated Niebaum. As Garnet's big arm went back it was seized and held from behind. Assailants leapt on him from out of the darkness. He was almost helpless.

But not quite. His immense strength helped him. He tore his arm free. And, on the spur of the moment, clapped his hand to his mouth. His hand opened. The stone passed. He swallowed it.

As the rough stone seared its way down a sensitive throat a laugh jeered close behind.

"Not so good." It came derisively. "They all try it. We don't lose valuable stones that way. There's croton oil. Then there's years on a breakwater to get over it."

Beyond the Thirsts

N'Gobi!

The man's weary gaze searched the mountain's glittering summit. In his physical extremity the vision of it awed. It overwhelmed. It oppressed him with a feeling of dire insecurity. So near. So tremendous. A vast spread of snow and ice lifting thousands of feet above a broken sea of barren crags. He shrank from the spectacle of it. He lowered his gaze. Ahead of him, at his own level, was that which inspired no awe. Only incredulity, and—a stirring of hope.

He searched the glowing shadows of a tremendous kloof. Its jaws were wide flung. Jaws of grim granite, footed by an armour of vicious thorn-jungle. The white bed of a broad, dry sand river streamed down out of it like an inviting roadway.

The man's big shoulders drooped heavily. His massive frame was gaunt. He was leaning on a staff that looked to have been cut for a less merciful purpose. And his whole attitude told of bodily exhaustion. In happier circumstances he should have been a giant among his fellows. As it was Ms flesh would scarcely have gorged a single assevogel.

He was halted with his three laden asses on the river bed. Sun-scorched and blistered, his white flesh looked out unashamedly through the rents in his clothing. Shut of fine flannel. Breeches of close-woven cord. His feet were unshod, like those of a Kaffir. But unlike the Kaffirs' they were scored with sand-cracks oozing the pus of fester. His asses were in no such desperate case. Their resilient backbones were sagging under a burden that was mainly water. But they were well fed. And still capable of mincing their way on dainty hoofs.

The gloom of the kloof held the man fascinated where the glory of N'Gobi's tremendous peak had awed. Weariness was fading out of eyes which had rebelled under months of sun-glare. They grew bright with the greed of hope dawning above an horizon of despair. But he remained unmoving, as though fearing lest reality should prove only mirage.

N'Gobi! At long last. Africa's mountain outlaw. A thousand miles beyond the last pretence of man's civilization. The trackless Thirsts left behind him. And even the dreaded Chikana, and his cannibal impis, no more than a nightmare memory.

The asses were off-saddled. They were kraaled in a makeshift laager of thorn-bush. A water hole had been scooped in the river's sand. And pack-saddles had been set in place to defend the laager's opening.

The man had moved on up the river bed with his staff replaced by a sporting rifle across his shoulder, and a slung haversack packed with biltong and soft-nosed shells. He was carrying a battered lantern fitted with a fresh candle. For all his festering feet he was pressing forward eagerly to complete the last stage of an enterprise he told himself was mad.

The overshadowing kloof swallowed him up. Its gloom wrapped about him. Sun-glare passed, and a vivid sky cut down to a narrow ribbon of steel blue above his head.

The ease of the river bed's sand gave place to water worn shingle. Shingle gave way to moraine. Which, in turn, yielded to a tide of boulders that bespoke the bed of a fierce mountain torrent.

The man sought a fairer footway. There was none. Lacerating thorn-bush banked on either hand with only the rocks between. There was no alternative. It was press on over every obstruction or defeat. Defeat was unthinkable.

It was a goal like the miraculous reality of some fabulous dream. The man was standing on a chiselled paving of ancient setting. Interstices were grown with lichens and fungus. A slimy damp cooled his fevered feet. It was the uttermost end of the great kloof.

The boulder-laden river of sand flowed away behind him through a widening passage of malignant thorn-bush. Above him rose hundreds of feet of sheer granite, streaming with a moisture that glistened in the scant sun-light. In front of him gaped a curtained tunnel-mouth, draped with a gauzy network of trailing creeper.

It was no natural cavern. Like the paving on which he was standing it was the labour of human hands. Evidence was there in every detail of it. Its surmounting arch was truly scribed. Its supports were carved pillars. And both arch and pillars had nothing in common with the granite about them. They were of built stone that was rose-tinted.

He opened the bosom of his shirt and produced a linen tracing. He unfolded it. He studied it, verifying. Then he returned it to its place of concealment. While his mind flung back to days already remote and almost forgotten.

He recalled the horror and despair with which he had faced years of purgatory on a breakwater where the day's work was washed away at night by a relentless sea. He remembered a poor stricken fellow convict whose lungs were eaten out by incurable disease. But whose reckless laugh was a melancholy joy. He thought of his impulse to befriend the man. And of its consequence.

He had listened to an incredible story which had N'Gobi for its setting. It had been told in the man's dying agony while ghastly spasms of choking tore the last remains of life out of him. Then had come the moment when a tracing had been thrust into his hands. It had come to him accompanied by a hoarse whisper which was all the voice the man had left. One whispered word. N'Gobi! But for the fascination of that name the whole incident would have been forgotten.

He recalled the day of his own release from penal bondage. Hardened to the condition of drawn steel he had begun a furious struggle for decent existence. There had been Zoutpansberg's alluvial gold. A wasted period at the much boomed Malmani fields. Then Tati, where he had found his luck. And all the time he had known the haunt of that hoarsely whispered word: N'Gobi!

Now he had proved a poor, generous creature's verity. And so the logic of it all must be accepted. Somewhere beyond that tunnel mouth a secret was lying hidden. A secret for his discovery.

He searched for matches and lit the candle in his lantern. Then with a thrust of his rifle he parted the tangle of creeper. Almost on the instant it fell back into place. It was behind him.

As the puny light of his candle battled with inky darkness there was a sound in the trailing creeper behind him. There was violent movement accompanied by a threatening hiss. One long green tendril writhed into active life. It swung, it slashed. And the poison glands of a deadly green boomslang emptied their virus into the dirty canvas of the man's slung haversack.

THE two men were climbing the steep slope of a sand-dune not unlike a miniature mountain. It was a surface of tufted, wind-swept, sun-scorched grass and soft red sand into which feet sank deeply. The goal of its summit would mean a measure of relief from the torture and foulness of swarming black flies.

Colonel Farlow kicked a grass tuft and stumbled.

"Awful damned going, Larky," he complained, as he recovered himself. "What with sun, and flies, and sand—"

His complaint trailed off as he turned to observe the outfit strung out behind him.

"Never had no use for sand, sir," Larky replied, sucking his teeth. "Give me Somme mud every time."

Larky had halted with something like military precision. But his interest was with the northern distance rather than that which was meandering up the hill behind them.

Larking Brown was a batman. A factotum. And something rather precious in human friendship. He also came from the Holloway Road, which he usually reminded everybody was "London North 7." His whole horizon was bounded by his service with Colonel Richard Farlow. In point of fact he had almost forgotten any life before that association.

He had started his career with the drums of a famous regiment. He had become batman to a newly joined second lieutenant, who was Farlow. He was still his batman. Serving with him throughout the protracted South African campaign in the Great War the Armistice found them still together on Europe's Western Front. Since then years of big game hunting, and exploration of some of the least desirable remotenesses of Africa, had made up a life originally designed for the narrower scope of city dwelling.

Despite flies, and sun-glare, and a desert thirst, Farlow's narrowed grey eyes smiled as he watched Ms outstrung outfit. He understood the leisureliness of it. The disregard for any military formation. A fighting force, it had its own peculiar ideas about campaigning which were mainly concerned with a maximum of labour to be avoided. His sympathy went out to his Bantu warriors whose head-loads were made up of weighty armaments. Then the herders of his string of ten laden asses. Who could blame if they laboured up to their ankles in hot, red sand and left the donkeys to their own devices. His bearers, weighted down with precious camp outfit, stirred pity.

But his smile broadened to a real grin as he contemplated the slim, active creature bringing up the far rear. It was the Basuto headman, Omba. He was equipped with a Winchester sporting rifle across his shoulder, butt uppermost. And he was clad in a suit of vivid pyjamas which he, Farlow, had bequeathed to him. He was belted with ammunition in every direction.

Farlow turned back to the man beside him, over whom his six feet odd somewhat towered. And he decided there was little to choose in the matter of attire between his black friend and his white. Larky was wearing a khaki tunic that was button-less and devoid of its sleeves. A pair of service cord breeches were puttee-less, and flapped loose about sockless ankles and laced highlows.

"Can't think why you still wear it, but that khaki of yours reminds me, Larky," he said. "Do you know what today is? Fifteenth of October. Do you remember? On this particular day in 1918 we were both killing Huns as if we liked it. Rather like potting bunnies in fresh cut stubble. On the run for dear life. Do you remember scrounging food because the rations couldn't keep up with us? A bloodsome time, come to think of it. Still, it was the end of a dirty business. Queer how dates come back to you. Remember the general's magnum of bubbly?"

"Not half, sir."

Larky smeared a finger across his nose. They continued their upward way.

"Bit out of your reckoning, though, sir, if I may say so," he went on. "It wasn't till the eighteenth that I pinched old goat-whisker's magnum, and them chicken sangwiches he was hell on. Pommery! Cor! Filled out the corners all right, sir. Can't understand a greedy blighter like him wanting to eat chicken sangwiches with us blokes nigh starved. See it in my diary day before we started out on this goose chase that I 'spects is going to get us down before we're through with it."

Farlow was gazing at the hill-top coming down to them.

"Beastly exact, aren't you?" he grumbled. "But they were good days to—look back on. When does the next war start?"

"Quick, I'd say, sir." Larky cocked a gloomy eye. "They've drawn a new map of Europe. And a new map of Africa. War to end war! And they do that. I ask you, sir. Would you stand for it? Hun colonies. A corridor drove right through their country. If I was a Hun I wouldn't let up till I'd got my own back. Same as us Britishers did when our politicians did their dirt down there at Majuba. Before we was born."

Farlow grinned at the grotesque figure ploughing along through the sand with tireless energy.

"Topping spirit, of course," he chuckled. "But you've got it wrong this time. They've been drawing new maps of Africa since the world began. And Africa doesn't care a hoot. No impression, what? Africa just swallows up every fresh civilization when it feels like it. Man and his works don't count in Africa. There's a wonder temple of Angkor, or something, in Cambodia, or somewhere. Took man hundreds of years to build it. Jungle just swallowed it up. Crawled all over it. That's Africa, too. Air liners. Railroads. Motor cars. International boundaries. In a thousand years some scientific bug'll be digging up a locomotive or something and classifying it as some sort of dead saurian. Take you and me, Larky. Crawling over this red-hot Balbau veldt because a fool government's lost track of a commission it sent to investigate mineral resources. A pair of ants crawling over Africa's sleeping carcase like doss-house fleas on a casual. Well, Africa just gets fed up with that sort of thing. Presently she'll roll over, get rid of us, and go to sleep again."

Larky felt himself unequal to it.

"'Spect you're right, sir," he agreed, and plodded on.

They reached the hill-top. A wide plateau of deep sand and lean, wind-driven grass. Farlow thrust back a wide-brimmed hat that might have belonged to a back veldt Boer farmer. He breathed relief and swished flies with an ox tail. Larky snatched a half burnt cigarette from behind an ear and lit it. But his watch on the northern distance remained unremitting.

"Hell of a country, sir," he observed casually and inhaled smoke. Then: "Ain't it?"

Larky's appreciation of the ill-reputed Balbau veldt was well founded. A grim steep-land where sand-storm cursed and water had no surface existence. It was part of the outlaw region associated with the hill-country of N'Gobi, to its north. But it yet possessed merits which the fly-tortured mind of a cockney refused to recognise.

It was just another variation of Africa's magic. Its heat was blistering. But it was braced by the cool Benguela current that rarely failed to make itself felt. Its network of sand rivers contained ample water deep buried in their channels. Its broad, hidden savannahs were stocked with game browsing and sheltering in countless thousands. Then there were hidden wonder valleys like that which now opened out beyond the sand dune's plateau. It was deep, and wide, and far-reaching. It was gorgeous with rich pasture and park-like luxuriance.

The Balbau had been hunted by Farlow for years. Its secrets were his intimate knowledge. Its lures and repulsions were commonplaces to him. The valley now opening out before him held memories of particularly deep interest. That was the reason of its present approach.

It was at the moment the pyjama-clad Omba ranged up beside his white baas, having shepherded the trailing outfit before him, that Farlow flung out a pointing arm at the meandering course of the sand river centring the valley.

"Look!"

It came with the sharpness of an order. And Larky turned from the valley's high northern shoulder where the alabaster summit of an ice-clad N'Gobi frowned like a thunder cloud in the purpling distance.

Farlow was indicating an ironstone kopje far down in the heart of the valley. It was on the north bank of the river. And it stood up like a watch-tower. Its summit was crowned by the laid stone walls of a kaffir kraal or fortress.

"See them, Larky?" he asked. "What about goose chases? Look. Their sort don't waste time where there's no carrion." He reached his field glasses and peered. "Hundreds. I can't think of anything but a Government commission to provide the banquet."

It was a gathering of vultures. There were loathesome creatures heavily a-wing above the kopje. Others were huddled hideously, perched on walls and rocks. Some were actively engaged. Savagely active.

Farlow lowered his glasses.

"I think you're right though, Larky," he admitted grimly. "It is a goose chase."

Larky watched the lumbering birds with a feeling of physical sickness. Then he turned sharply back to the northern heights of the valley.

"All I hope, sir, is they picked them Gover'ment bones clean. We ain't looking for typhoid or enteric. Got to think of getting home for Christmas. The Cup Ties'll be starting. You can't—"

But he broke off. And the silence on the plateau was not without omen. Omba was leaning on his rifle with eyes and every other sense alert. The asses cropped at grass that scarcely seemed worth while. Farlow smoked a cigarette, and watched the circling assevogels.

Larky suddenly removed his hat and raked a shock of flaming hair.

"I don't like none of it, sir!" he exploded. "Not a little bit! And that's a fact."

A rich diapason boomed in Farlow's ear. "Yellow man. Oh, yes."

Omba sang it in his deep bass while his big eyes grinned meaninglessly. Farlow glanced from one to the other.

"And I'm smelling the bones of a Government commission on that kopje. We're not so far south of our rascally N'Gobi. What does it mean? Massacre by yellow men for assevogels to feed on. I'm afraid it means funeral business, too. Quite a night of it."

There was real humanity in it. A mute sympathy that lost nothing for the casual manner in which the work was carried out. Kaffir and white man worked for half a day and the best part of a night collecting and burying vulture-ravaged remains, and erecting a rock cairn to mark the grave of gallant men who had died fighting with the sort of inadequate equipment with which only a Government could have provided them.

Fighting whom? What?

Farlow knew at the instant of arrival at the kopje. And Larky was there to add his understanding of the massacre that had been committed. A camp had been stripped of every weapon. Every article that might serve the despoilers. And the rocky slopes of the kopje were littered with the white-man remains which the assevogels had broadcast. Nothing was left to tell but bones and a few fragments of clothing which proclaimed white identity.

The only satisfaction was the discovery of black and yellow remains amongst the ghastly litter.

It was left to Larky at the end of the night's work, after disposing a night guard of Bantus at the stone defences of the kopje, to sum up the situation. It was shorn of any nicety of language.

"'Tain't any use us talking, sir," he declared, as he endeavoured to transform a small, ancient, stone-built hut into something fit for his chief to sleep in. "Those yellow shysters copped 'em out proper. The Gover'ment thinks it's got the laugh on us when it comes to yellow blokes. Well, it's not going to laugh itself dizzy after this. Fancy sending a crowd of highbrow mining experts up on to the Balbau. Betcher there wasn't a machine-gun among the lot. Like as not they handed 'em pop-guns. D'you know what, sir? There's a crowd of them, thick in the forest on the northern slopes. Black as well as yellow, if I know anything. And we'll cop it plenty come daylight. Dirty yellow snakes. Hundreds of 'em, or I'm dippy."

Farlow removed some of his clothing preliminary to occupying the blankets Larky had laid out for him on a camp trestle.

"There's no argument, Larky," he said quietly. "If your word weren't sufficient we have Omba's. And you can't beat a Basuto's guess when it comes to what's hiding in jungle. But we must get a spot of sleep and be ready for 'em. Good night."

Farlow watched a reluctant retreat beyond a dirty Kaffir blanket which Larky had hung over the stone doorway of the hut for his chief's better comfort. Then he extinguished a candle which Larky had set up on a spill of grease. He was well enough aware that he would be watched over by a sleepless pair of mournful eyes concealing a fighting spirit that was frankly yearning for that battle which Larky had promised for daylight.

Farlow was buried beneath a leopard-skin korross despite the heat of the night. There were a couple of kaffir blankets between him and the canvas of his camp bed. His pillow was a canvas kit bag which contained his wardrobe. The hut was singing with flies and alive with white ants when Larky pulled aside the blanket strung over the doorway.

A blaze of slanting morning sun streamed in on the drab interior.

Farlow cursed. He sat up, propping his lean body against his kit bag. And he blinked resentfully at the red-head and unattractive face with a week's stubble of beard that loomed in at him.

"You're a damned depression, Larky," he growled, reaching his cigarette case lying on the up-turned box beside him, "off Iceland, or somewhere. That face. Can't you kick it? It's a blot on the skyline. I haven't had half enough sleep."

Larky gloomed unsmilingly. Any other sort of morning greeting would have disappointed.

"There's ignorant blokes at home said worse about my face than that, sir. But I don't take notice of them that hasn't no manners. Omba's had the boys hot up yesterday's hash for your breaker. Flies must have got at it in the night. Told him he'd have to eat it himself. You need a couple of them bottled rashers before the fun starts. The forest's on the move like. Have to eat quick."

Farlow inhaled a cigarette luxuriously. A gleam of affection looked out from under the lids of narrowed eyes.

"You're a blighter, of course," he observed cordially. "I'll eat whatever you choose to bring me if you'll only get to hell out of this. Go and run a mower over the bottom of your head, and clean off that red fungus. Omba at the walls?"

Larky sucked his teeth.

"All over 'em, sir. Sar'nt-majoring the Bantus like he was on parade. Rifles laid ready and magazines filled. Them eyes of his is grinning murder. Can't understand how that bloke fancies killing like he does. Pity he's a black. Win the King's Prize at Bisley he would."

"He's certainly a born killer as well as a damn good cook. But--"

It was two shots in rapid succession. There was a momentary silence. Then a deep bass boomed. And Larky and Farlow listened. It was a language of clicks which seemed to tap-tap like machine-gun fire.

Farlow grinned. Larky mutely questioned.

"Oh, telling them what he thinks of 'em. And praising his own skill," Farlow explained. "Must have hit something. Throw me my pants."

Farlow was dressing at speed.

"We'll make a clean up today, Larky, or go under," he grinned, tucking an unclean shirt into his old service cords. "You know. What you like. Getting our own back. Those boys were white if they were Government lambs. And we don't leave this dump without cleaning things up to their memory."

He pulled on highlows, and wrapped rolled puttees about massive calves.

"Got to be a sound job. The old machine-guns," he went on. "The yacht's waiting at the coast, and if we make a good job of it you ought to find yourself at a Cup Tie or something on Boxing Day. Got the Lewis guns set?"

"The way you said, sir."

"Good. Feeling glad?"

"Merry as a grig, sir. I dunno," Larky demurred. "Unhealthy. That's what the Balbau is, sir. Here we are. Set up a fair cockshy on top of this kopje. Makes you feel like those boys in the Zulu War. Isandhlwana, wasn't it? Still, Zulus is Zulus. The blarsted cocoa-nibs hereabouts fancies you best in the pot. I'm all for the bright side of things, myself. You know, sir. Knock back a couple of pints and look for a laugh. But I can't see it would set a cat laughing stewin' in a pot to make hash for a lousy lot of cannibal savages. I ask you?"

Larky found himself outside the hut with Farlow sluicing in a bucket with no more than a pint of water in it.

"The trouble with you, Larky," Farlow complained while he washed, "is you never will see the dark side of things. Too much sense of humour. That pot business is no darn joke. I'd hate like the devil to be made into pea-soup. And I'm not going to be if I can help it. We're just going to turn this beastly valley into a sort of skittle alley. Us rolling the balls. And your cocoa-nibs the skittles. See? But I can't do it on an empty stomach. See what I mean?"

Larky eyed a filthy towel with complete disapproval.

"Well, there it is, sir," he said preparing to depart. "Can't help the way a bloke's born, can you? I always was a rare one for seeing the comic in things. But I'm telling you, sir," he gloomed with dire earnestness, "if you should have to go into that bleeding pot I'm with you. And that ain't comic neither!"

THE laid stones of the old kraal walls were burning hot. The ironstone footing of the kopje's summit was punishing even to the calloused soles of kaffir feet. The sun was beating down into the heart of the valley untempered by any breath of the cool Benguela current.

Away below the grey-green veldt was empty of all but its colonies of white ant-heaps standing up like giant fungus. But at the valley's far slopes of jungle forest it might well have been different. In particular the northern bush which was in the direction of N'Gobi.

Farlow peered through levelled glasses. He was leaning on the hot stone of the northern wall. His sun-scorched, bare elbows remained indifferent to the burning. Farther along his fighting Bantus were ranged down the wall under Omba's charge. Each was a skilled rifle shot. And each had his rifle laid ready to his hand with its magazine full. Omba was in fighting-array. His black body was bare of all but ammunition belts and a hide moocha. Larky was beyond. His charge was the eastern angle of the kraal wall. And he was accompanied by many armaments.

The morning was wearing on and the enemy still clung to the shelter of the northern forests. There had been sporadic firing. There had been sniping from the bush. But there had been no attempt at that storming attack which Farlow felt confident was yet to come. Overhead, high enough to be only just visible against a brazen sky, vultures were already circling. It was an indication that a measure of success had fallen to the fort guns.

Farlow turned and beckoned the Basuto. He was searching again through his glasses when the man hurried up.

"It's coming," he said, using the man's own tongue, without lowering his glasses. "It's coming quick. A big lot. Impis. A big kill. Listen. Not a shot till I say. Understand. That's important."

The grinning nigger spurned his own tongue. His pride was in the white man's.

"Ja baas. Us know plenty. Us kill 'em much bimeby when baas say. Oh yes."

"Quite," Farlow approved.

The man marched back to his fighting squad. And he passed down its line admonishing.

Omba was an instinctive killer. He had inherited from forebears in direct descent from the fierce Moshesh, and he asked no better than that the odds should be heavy against him. But that was because of the machine-gunning he had acquired during the African campaign of the Great War. The new white man "med'cine" pleased him mightily. He could kill so many with so little effort.

He finally took his position up beside a gun he would ply and feed till it ran hot or seized.

Farlow knew his man. Hence his firm order. But there was uplift for him in Omba's instant promise of obedience and savagely grinning eyes. Already, on his way up to the Balbau, Farlow had lost two of his best Bantu fighters, sniped in the bush. He was more than glad of any opportunity to wipe out that score.

Omba turned from his own machine-gun to beam as Larky came hurrying from his wall angle to approach Farlow. He grinned after the sturdy figure anticipating results. And he remained between watchfulness and listening.

Larky almost clicked his highlowed heels as he came to a halt.

"Here, sir," he cried. "Have you got it? What I said. Yellow. It's yellow perishers and cannibal savages mixed this time."

He flung out a bare arm knotted with muscle. It was pointing at a narrow break in the bush-lined slope.

"That's where I see 'em. Two yellows and a bunch of blacks. And they stood while I got a line on 'em. But they'd hopped it before I could loose off. Yellow, sir. Khaki, too. Shirt, and pants, and puttees. Reg'lar white outfit. But yellow as a 'jimmy' we don't never see these days. What d'you know about it, sir?"

"It's no laughing matter." Farlow nodded slyly. "But there's more than two. Get back quick. We're going to have storm-troop waves over again, if I make a right guess. Hun-trained show. Or copied."

Larky hesitated.

"It's been mausers every time with them so far, sir," he reminded doubtfully. "What if it's machine-guns the same as us—this?"

Farlow shrugged impatiently.

"Why not?"

Farlow saw Omba in the act of sighting his Lewis gun.

"Wait for it, Omba!" he ordered sharply. And was just in time to discover the meaning of the Basuto's activity.

It was there at the foot of the bush slope. A long scattered line of black warriors. It had broken cover, and was advancing under the futile protection of white hide shields and bristling with numberless murderous blades of assegais gleaming in the sun. It was the awaited offensive. A surging black wave that came leaping, crouching, and even snaking its way through the tall grass.

Farlow's order came sharply.

"Get after it, Larky. The real thing. Have to draw our fire with those poor black fish. Understand? Just kill. With care. Mark your men. And count each shot a 'bull.' Don't waste a shot. And have the Bantus and Omba do the same. Just rifles. Hold up machine-guns till you get word. It's the yellow men we're to wait for. And they won't show themselves till those poor darn blacks reach storming contact."

Larky was gone on the run.

Instantly began a sniping that was the deadliest form of cold murder. The target was there like buck in the high veldt. Rifle fire sprayed with the precision of target practice with half a score of men behind it who were artists in the business.

It should have been pathetic. A senseless line of befeathered magpies, white of breast under cover of hide shields. They moved and postured. And one by one they went down to each truly sped bullet.

A second wave emerged from cover. It came on in the wake of the thinning front line. It came voicefully and urgent. Boastfully triumphant. But it was ignored by the defence which went steadily on with its decimation of the leaders. A third line broke from the bush.

The valley's bottom had become alive with perhaps a thousand reckless, lusting savages in all their war paint. They pressed on towards the kopje, utterly disregarding. The fresh waves closed up on the enfeebled front line and Farlow knew nauseation as he thought of that which would presently befall.

But he remained all unrelenting. He continued starkly painstaking in destroying front line life. It was a simple strategy of delaying contact while he waited for his real moment. He knew the "pot," with which he had twitted Larky, was a most unpleasant reality. These were Chikana's warriors. And the game was kill or cook. He had no intention of enduring eternal darkness within the disgusting purlieus of a savage belly.

Despite the merciless and accurate rifle fire the shattered remnant of the foremost wave reached the foot of the kopje. It was the psychological moment upon which Farlow had gambled, and for which he had waited. Merciless joy leapt as he beheld. The far bush fringe had become a strung-out line of perhaps five hundred khaki-clad figures. It advanced on the run in wide skirmishing order and it belched a hail of mauser bullets to sweep over the stone kraal and beat upon its ironstone.

Farlow shouted his order. Those only waiting for it rushed gladly to obey. Repeating rifles were flung aside. Half a score of machine-guns were fed and came into action to despoil a poor imitation of a Hun offensive on Europe's Western Front. It was defeat of yellow purpose to ride to victory on the shoulders of savage sacrifice. The machine-guns blasted a fire that staggered and withered.

The counter offensive of it was devastating. It was rout almost instant. The hail swept the black and white field. It lifted to the yellow behind it. There was no mercy. There could be none. Defenders were few and the enemy many. Hand to hand conflict was unthinkable. It was long range slaughter or follow in the wake of a Government commission.

In less than a half hour the assevogels were circling low.

Larky stood up from his kneeling. A thoughtful finger passed across the snub of his nose. In one hand was a Mauser automatic. In the other was a long, keen-bladed knife. It was a curved blade and its sheath was attached to a belt which had been taken from the body of the man at his feet.

Dick Farlow was still on his knees beside the wounded man. He was completing a rough examination of shattered ribs.

They were out on the open of the valley's bottom. A slaughter yard they had created. It was a nauseating carnage aggravated by the circling presence of lumbering vultures.

Omba and native bearers were moving swiftly from one dead body to another, with orders to collect for disposal, and to succour, if possible, the wounded. But Omba and his men knew little of human kindness where the dreaded Chikana and his savage impis were concerned.

Farlow stood up from the wounded yellow man and hailed the preoccupied Omba. The man came on the run.

Farlow pointed the khaki-clad figure.

"Get him up to the kraal," he ordered. "Get some of the boys. He's alive. And we want him to talk. See what you can get out of him when you've made him comfortable. You'd better get all the boys back up there, too. We haven't time to be human."

It was said in plain English on purpose. And while he spoke Farlow watched the face of the man on the ground. The expression of pain-racked features told him that which he wanted to know. He had been understood.

There was a moment while Omba and two of his boys handled the man. Then Farlow and Larky looked after them as they bore their burden up the ironstone hill.

Farlow pointed at the weapon in Larky's hands.

"Mauser, of course. Always is," he said. "That knife? German?"

Larky offered the evil looking blade for examination.

"Sheffield," he spurned contemptuously. "Hun gun and British knife. What the hell? They aren't Totties. They're not blacks. Wouldn't say they were Chinks, neither. Nor those Basta blokes. They're in khaki, like they were white. They're yellow. I ask you, sir? Mongrels of some sort. Must be. Rotten curs anyway."

Farlow returned the knife and gazed thoughtfully at the far line of the bush-clad slope.

"Not mongrels in your meaning of it, Larky," he demurred. "Just a race we don't know about." He raised his eyes in the direction of the distant N'Gobi. "It's always in N'Gobi's neighbourhood," he went on. "Directly that unwholesome hill comes into view we make contact and they try to wipe us out."

"Never did like that hill, sir," Larky mourned. "Shuts itself in with marshes and thorn-bush like it had something to hide. Must be lousy with 'em. Like to bet a tanner Omba doesn't get nothing out of that bloke."

"Looking for easy money," Farlow objected. "We've tried third degree on them before. Someday we'll have to look into N'Gobi. Whoever these people are they're in touch with world affairs. For instance, that attack. Hun storming badly done. But we'll get ready to trek back if we don't get a counter attack. Peter van Ruis will want our news down at Gobabi. Then we'll make Chutanga. Pick up Karl with the Oompee and run down to Cape Town. We ought to make the trip in time to catch that Delta Line's Olivarria. I think you'll get Boxing Day at Highbury after all."

"Yessir. But how about the mail boat," Larky suggested shrewdly. "Might get some of the League matches earlier, too."

Farlow laughed as he turned towards the kopje.

"'Fraid not. We've got to travel with Captain McGregor, if we can make it."

Larky slanted a quick eye and nodded.

"Oh, him, sir. I getcher. Dirty bit o' work, that bloke."

"Quite."

THE terrace was high up on a precipitous hill slope. It was a notch cut in its stark face just above the limits of the tropical vegetation luxuriating in the heat below. A veritable eyrie, it commanded a view over lesser hills. Over hidden valleys and gorges. It looked down upon a great lake which shone like a mirror in the sunlight.

It was basking in a passionate tropic glare. But heat was pleasantly tempered. Cooling breezes were mercifully drifting down off an icefield far above it; an icefield whose ages-old glaciers were lost under a cloud-drift forever on the move, forever changing shape and density.

The ledge of it was cut deeply into the hillside. The instruments of man had driven far into the cold heart of grey granite to level an area of many acres. There was half a mile of its length. With a depth of several hundred feet. A staunch parapet defended it against an abysmal drop below.

There was nothing rough-hewn in its quarrying. Its granite background was smoothly sheer and ribbed at regular intervals by buttress columns, admirably carved, cut deeply out of its face. Nor was the parapet of inferior workmanship. It was stone-built. A softly rose-tinted stone. And none of the material of its construction was rectangular. The stones had no uniformity in size or shape. Yet, without bonding cement, each stone seated in its place with such precision and closeness that interstices were almost unapparent.

The object of such an aloof terrace was there in ample evidence. Once it had been called upon to support a magnificent structure set up on super-imposed terraces of a similar stone to that of the parapet. It had been reduced to a sprawl of ruins. Decapitated columns stood up in ranks at regular intervals, like the stumps of decaying teeth. Their sculptured bases were buried deep in a mass of shattered rubble which once had formed the roof they had supported. There was carving on almost every stone. And the keynote of its ancient decoration was an elaborate drawing of a deified sun.

An architectural triumph of remote times dedicated to the worship of the Sun-God. Now it was gone. All its craft and artistry wrecked. And, in its place, in place of chiselled beauty belonging to the days when labour and costliness were of small account, crude, modern utility had been enthroned. A single-storeyed dwelling of colonial type had replaced it. Verandahed, spaciously enclosing a wide courtyard, and built of the stone of its predecessor, it nevertheless possessed the unmodern modesty to dispose itself at the far end of the terrace.

A girl was leaning over the coping of the parapet. It was a pose only to be dared consciously by a woman of perfect slimness. She was deeply absorbed. And her preoccupation found expression in the nervous clasping of attractive hands whose bejewelled fingers were tightly interlaced.

She had all the freshness of early years. Her black eyes had the almond shaping of the East. And they were gazing unflinchingly at a westering sun. But, unlike condor or eagle, dark, curling fringes were there to defend against blinding light.

She was beautiful in a modern way. Make-up had been deftly applied to features of an already perfect face. A chaplet of priceless jewels adorned a brow that was broad and smooth. And it encircled a head of raven-black hair that was smoothly centre-parted and coiled in dainty plaits over ears of shell-like beauty. She was wearing a closely-fitting, sheath-like gown of glittering sequins which shone like burnished steel armour. It was a single piece affair which cunningly revealed those slim curves it pretended to conceal.

Within a yard or so a man was dizzily seated on the coping over which the girl was leaning. He was aged. He had snow-white hair that was uncovered to the sun, and which was close cropped to reveal the massive shapeliness underneath it. His eyes were as black as his daughter's. But there was nothing Eastern in their shaping. He was a deeply sunburnt white man of British origin whose frame and stoutness of limb denied his many years.

He was observing watchfully. And his daughter's gripping hands warned him of a mood approaching explosive climax. There was cold warning in the shake of his cropped head.

"Why now, my girl?" he asked levelly. "You've never found it necessary before. Why interfere in things outside a woman's province? I agree the position's not all I hoped for. But, politically, I can't see that it's worse than it has been for a long time. No. I'm not worried. Farlow's been a thorn in our sides for years. There's danger in his activities. But there always has been. Ankubi made a rotten mess of it when he should have wiped him out. That's true enough. But it's no more than the fortune of war. One day we'll get him. And meanwhile I'm not squealing over spilt milk. If there's nothing more I'll get on down to the batteries."

But he knew there was more. It came with the swift swing round of a lithe young body.

"Spilt milk!" It scorned hotly. "I wonder, Father. Is it age? Is it senility? Or are you just thinking with a mind that belongs to forty years ago. 'One day we'll get him.' And I tell you it will be too late if you don't get him now. At once."

The girl flung back to her leaning. But her angry eyes avoided the sun and gazed below her.

Hundreds of feet below she beheld tiny craft with vividly coloured sails scudding over the shining waters of the lake. There was a glittering mist far down its northern shore which seemed to deaden the thunders of a mighty cataract it concealed. She saw a busy traffic moving over a red-sand roadway. Then the multitude of habitations. They looked like infinitesimal cubes of rose-tinted stone. Each with a uniformly flatted roof supporting a sort of "beehive" dome. Her gaze settled upon a small enclosed aerodrome where two planes were standing before their hangars.

The man's response came after a thoughtful pause.

"I think you're viewing the whole thing extravagantly," he said patiently. "The mind that belongs to forty years ago has thought very successfully for all that time."

"To finish up at last with an act of complete, blundering stupidity. It's—it's—damnable!"

The girl's eyes were full of hot challenge. Tire father's were calmly appraising.

"Is this getting us anywhere?" he asked without seeming umbrage. "But what can Farlow do? What does he know of us here? Believe me, Raamanita, if Farlow knew anything more than he's known for years he would be very literally knocking at our doors. Ankubi blundered. But there it is. Beyond that I can't see anything to disturb."

Raamanita pondered the big creature. She had suggested age. Senility. And she knew there was no sign of these things in this father whose ruthlessness had always been a matter for her admiration. But her woman's mind was set upon a definite purpose. And now she felt she had prepared the ground sufficiently. All her heat abruptly evaporated.

"Sorry, Father," she regretted coolly. "Feelings run away with me. But, anyhow, I don't think you fully realize Dick Farlow. I do. I've watched him so long through the press accounts and stories of him. It began years ago when I was a child in England with Uncle Tony. He was my hero then. I'm not sure he isn't a bit of a hero to me now. But the thing that seriously matters is that when he talks in Africa Governments listen. One word from him in the right quarter and good-bye to your forty years' work. Good-bye," she went on with a cunning slant of watchful eyes, "to your years' old dream of unearthing a fabulous lost reef of almost solid gold. And even, perhaps, good-bye to life itself. You and Ankubi between you have turned Dick Farlow loose upon his world with a complete story of the massacre of a dozy Government Commission. You've shown him who did it. Massacre may be merely political to you. In common law it's murder. And usually murder finds a hangman at the other end of it. Farlow can turn a hornet's nest loose on N'Gobi."

The girl's hands spread out.

"But that's only one aspect of it," she went on. "The aspect as it affects you, personally. There's another. And it's of serious concern—to me. Ankubi's left hundreds of dead or wounded for the assevogels out there on the Balbau. Half the wives and mothers in these hills are grieving. The people are savage, father, I'm their queen. You made me their queen. They're looking to me in their trouble. They're even blaming me. And when people start to blame their ruler it's time to do a lot of thinking. That's what I've been doing."

"And the result?"

"A plan. A plan to save forty years of work."

"Splendid!"

It was irony. And it was devastating in its biting cold. The man's black eyes steadily regarded the girl whom a woman of yellow skin had born to him nearly thirty years before. Never before had he found it necessary to regard her as other than a beautiful pawn on the chess-board of his scheming. But now he knew she was to be considered. And seriously considered.

"Twenty-seven, aren't you, Nita?" he nodded. "No longer a kid, anyway. Have you thought that you've never known worry or difficulty ever since you were born? You've had everything any reasonable girl could desire. You can't complain of the life I've given you. You can safely leave the people to me. I'm afraid I don't usually fancy plans other than my own. But I'll admit no sane mind ever evolved a plan that didn't possess some features worth consideration. Now this of yours. Of course—"

His heavy shoulders lifted.

"When I was much younger than you are, I, too, worked out an infallible plan," he went on grimly. "I knew it all. Much better than those who had had years of experience. My supreme confidence cost me years of penal servitude on a breakwater the sea washed away as fast as I and my fellow convicts built it. Those years taught me that no game can be successfully played until you've learned the rules by heart. Go on."

The girl's eyes sparkled resentment.

"They taught you more than that, Father," she cried. "They taught you about N'Gobi. A fellow adventurer, less fortunate than you, told you of ancient gold-workings that would yield you fortune. He told you of a people, all that were left of an ancient race which once was the dominant people of Africa. Of a great Queen who ruled over them thousands of years ago. But most important of all he told you of a fabulous lost reef which had once been the chief source of the ancient world's gold supply. And he gave you a chart of how to come to your Eldorado."

Raamanita turned to watch a flight of huge birds winging across the evening sky. She saw them approach the overshadowing of N'Gobi's snow-crowned peak. She pointed to them.

"Assevogels, glutted with the carrion you and Ankubi left for them out on the Balbau."

She went on derisively.

"You know, Father, I don't think your understanding of women is in the least extensive. I fancy women never occupied their rightful place in your man's life. I even doubt if you knew the least spiritual urge in your parenthood of me. Of course my modern mind isn't deluded by the old-fashioned hypocrisy of such a thing as 'spiritual urge' in the matter of offspring. Parenthood, at its best, is a matter of service, utility. Even cannon-fodder. At its worst, or most commonplace, it is the mere satisfaction of sexual desire comparable with that of any dumb animal. But in your case I'd say the animal has always been subservient to material considerations. I was necessary for the furtherance of your plans here in N'Gobi. So I had to be born to the only woman you found amongst our people who claimed direct descent from that queen who reigned thousands of years ago. Her claim was naturally as fabulous as other things. But it suited you."

The girl's mocking passed.

"So I've nothing to complain of! So you think you've provided me with everything a reasonable woman could desire! And yet you've held me here since ever I reached full womanhood, extravagantly educated in England, mewed up with a lot of yellow creatures whose blood I share. What do you know of a woman's mind? What do you know of her desires? Nothing. All you understand is that N'Gobi's gold is unsuspected by the rest of the world. And, somewhere, these hills contain a solid mass of precious metal whose discovery will shatter gold values the world over. Man, claim for yourself astuteness, courage, determination, imbecilic credulity, if you will. But don't let your conceit tell you you know the first thing about a woman or her desires.

"Here, Father," she hurried on, "before I reveal my plan to you let me bare things to the bone. I've got to show you once and for all you're not dealing with a child or a puppet. You're not dealing with one who's content to eat out of your hand, furthering your schemes for the few gauds with which you have decked her. Remember, I'm the daughter of a clever, unscrupulous man. And part of my blood goes back to great people, who, supposedly, once ruled a vast tract of this old, old world.

"We can leave the story of N'Gobi as you first heard it from a handful of yellow survivors, who, when you first came here, forty years ago, were ready to welcome anything that wasn't black. I'll only remind you that the story came down from father to son through countless generations telling of a race of millions. Telling that N'Gobi had once possessed its wonderful reef which had made gold almost as common as our iron is today. Telling of tragic, volcanic disaster that swallowed up that reef. And of black, conquering hordes who over-ran the country, and wiped out our yellow ancestor's rule. It also told that a poor human remnant was dragging out a benighted existence here only waiting for a return of that old queen who would recover for them their lost wealth, and, by her might and genius would restore them to their original greatness."

A second flight of returning assevogels sailed heavily towards N'Gobi's peak and vanished. The girl went on:

"The only detail of that story that interested you was the— gold. You swallowed the bait of it. And you've been held ever since with your whole mind one supreme note of interrogation. Where? But more important still how could you become possessed of a gold reef that would stagger the world?

"You quickly found an answer to the second question. The how of it simply leapt at you. You had found only a handful of our yellow people which was insufficient for your purpose. Seven or eight hundred. And mostly women. You wanted more. Legions. So you set to work to operate the old galleries as best you could and preached polygamy to the people. The whole thing would take time. But you were young. You spent your winnings from the old galleries on equipment. And demanded huge reinforcements of babies if the promise of our people's faith were to be given effect. The women were three to one in excess of the men. They set to work. And the result was comparatively staggering. Births almost became litters.

"Your plans went well. While repopulation was in progress the old workings yielded far in excess of your hopes. And you very wisely spent your winnings in fostering our people. You brought them out of the dark places into a world of sun-light. You fed them such food the like of which their stomachs had never known. You clothed them as white men and women. You drilled and equipped them into an army for modern warfare. And all this you did under the reassurance that the day of their old queen's return was near at hand.

"Meanwhile, of course, my birth had to be arranged. You selected my mother with the greatest possible discrimination and saw to things. And at last your great day arrived when you were in a position to announce the old lady's reincarnation. Their queen had returned in my infant body. Then the next step. When I was sufficiently grown I was given a great part in the pantomime you were preparing. I had to become the centre piece of your culminating transformation scene. Europe. I was sent to Uncle Tony in England for education and to be made over into your fairy queen. Under the influence of rapidly growing fortune Uncle Tony put his heart into the job. And at long last I returned over our secret highway a youthful, modern vision of a queen militant determined upon world conquest. I came complete with perfect English education. A mirror of modern fashion. And I was accompanied by all the marvels of modern mechanical science, a wealth of war-like instruments, and masses of gold-working machinery. Your triumph was complete. But—"

There was a gesture of hands that deplored.

"Over eight years ago, Father," the girl sighed extravagantly. "You were asking for a life-time's lease of these hills that you might dedicate your remaining days to your task. You obtained that lease. It mattered nothing to you that the old galleries had already yielded you and Uncle Tony a fortune of millions shrewdly disposed amongst the safest banks of Europe. That fabled reef. It had become your obsession, insanity. Everything had to be sacrificed to its pursuit. Even me. You had won out. There was nothing left but to go steadily on until your supreme goal was reached. Then you blundered. A blunder of such magnitude that the whole structure of forty years' labour is even now tottering. You've massacred a Government commission which could never have caused you serious hurt. And you've failed in a senseless attack upon the one man in Africa you should have avoided like a pestilence. Richard Farlow."

"A superfluous recital, my girl, and with a faulty conclusion," the man replied coldly. "The one man in Africa who must be got rid of at all costs."

It was only with difficulty the girl restrained expression of relief. It was the retort she had intended to provoke.

"Quite," she agreed. "All that is the matter is the way you set about it. A blundering Ankubi. A ridiculous and beastly massacre. My plan is different."

"Tell me."

The sharpness of it more than satisfied.

"I personally shall muzzle Dick Farlow like any other troublesome dog. But in my own way. He will come here to me. He appeals to me. You assure me you have given me everything a reasonable woman can desire." She shook her head. "Not until you have given me—Dick Farlow."

It was there in her eyes. The hot light of them. The father read it plainly. Without scruple in the affairs of life his whole Victorian manhood nevertheless revolted. The hideous sexual frankness nauseated.

"You're raving mad!"

It exploded to leave the girl unabashed.

"Does it matter? Is Nature sane?" she mocked. "At least it will leave you with an easy mind to pursue your will-o'-th'-wisp. Do you want more? My desires are my own. Farlow shall come here. And he shall learn all N'Gobi can tell him."

"You!"

It almost shouted as the man leapt from his seat on the coping. He towered threateningly. His eyes were aflame. One great fist was raised as though about to strike. Raamanita remained unimpressed.

"Just silly," she scorned. "An accusation on a par with other stupidity. You forget that I am queen of N'Gobi. You forget that I—not you—am responsible for the crime that the fighting force of N'Gobi has committed. Sit again, man, and don't flourish a childish fist or I shall begin to believe in that senility. Use the nimble wits which have served you so well in—the past."

There was no return to the man's seat. But the threatening fist fell to his side.

"Then for God's sake cut out your modern sex beastliness and come to your plan."

The girl's quick mind read the yielding. And with sound generalship she restrained the impulse to mock.

"It's so very simple," she explained, "if we put our feelings aside and consider politically. The position is quite clear. Farlow will tell his story if left at large. And that, of course, will rob you of everything you have laboured for. Then there are those other consequences. But like all the rest our hunter man has his price if it's in the right currency. Dick Farlow is first and last a hunter and explorer. He's got his insanity just as we have ours. He lives for the secrets of Africa. And the remoter, the more difficult they are to obtain, the more hotly he pursues them. Our yellow people have intrigued him for years. He would rather discover them than anything else in the world. I propose he shall discover them. Once he's learned of our 'Queen's Highway' nothing on earth will keep him from it. And, just as surely, nothing will induce him to tell his story of the Balbau lest the Government should interfere with his plans. Then think how the policy will react on our people. How it will strengthen our hands. My prestige. I possess such magic that my enemies are brought suppliant at my feet."

The girl's cynical laugh was without effect.

"And if he refuses to become—?" The man's voice trailed off.

Raamanita's shrug was supreme in its contempt.

"Need you ask? You?" she protested. "Listen. This is the way of it. I've prepared a careful plan of our 'Highway.' I've titled it alluringly. I've drawn it so that only Dick Farlow may read it. I shall entrust it to Chiabwe. You see, Chiabwe and Ankubi are rivals for my favours. I can play them one against the other. He will set out well equipped. He will follow Dick Farlow until the map is safely in his hands. If necessary to Cape Town, or even England. Farlow will swallow my bait. He will come here hot-foot. And he will find—me."

The girl turned away far-gazing. Then she went on without even a glance in her father's direction.

"Once here he'll never be permitted to leave—alive. He'll play the part he's cast for or—" Again came the girl's shrug of contempt. "On the other hand should he prove tractable he can live until I lose my interest in him. Then I'll hand him over to you. Or, better still, perhaps, to our gentle Ankubi."

Raamanita gazed out over the great lake while her father watched her.

"Well, Father?" she urged.

The man took swift decision. He even smiled.

"I don't know, girl," he said doubtfully, but in a tone that was almost too easy. "I once thought I knew it all. But—" he gestured. "Still, I agree the man has to be dealt with. If you can bring it about, well and good. You'll certainly be a worthy successor to that precious ancestor of yours. To my way of thinking Ovrana's knife or automatic would be the better way. But if you think you can put it over well and good. If you fail don't blame me if I leave you to stand the racket. It looks to me as if you'd better remind yourself that your life depends upon your success. When?"

"Tonight. At once. Since you agree."

The man further relaxed.

"Everything fixed?"

"Everything."

"Then—" There was a gesture of flattened hands. "—I'll get on down to the batteries and close up."

He moved away. Raamanita watched him go. And she remained gazing after him till his big figure reached the head of a broad roadway at the far end of the terrace which had been engineered up the precipitous hillside from below.

Then she, too, moved away. She hurried towards the single-storeyed modern building which was her royal palace.

The man went on down the steep roadway. It wove zig-zag path down the hill by means of many hairpin bends. He strode easily, vigorously. And there was no sign of advancing years in his robust gait.