RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

Thanks and credit for making this work available for publication by RGL go to Jim Blanchard, who donated the scanned image files of his print edition of Bomba the Jungle Boy in the Abandoned City used to create this e-book.

"Bomba the Jungle Boy in the Abandoned City," Cupples & Leon, New York, 1927

"Bomba the Jungle Boy in the Abandoned City," Cupples & Leon, New York, 1927

"Bomba the Jungle Boy in the Abandoned City," Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1954

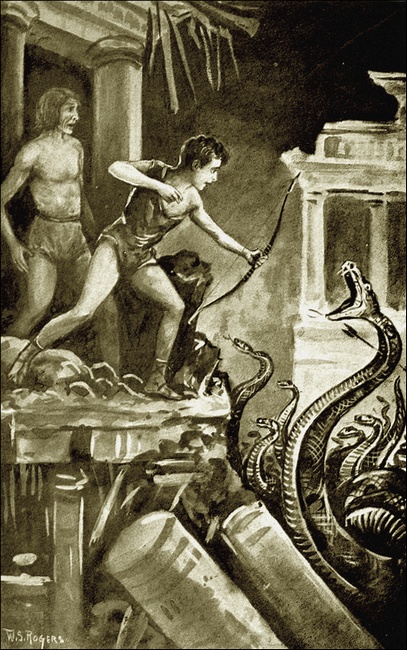

Frontispiece

The arrow pierced the throat of the monster.

THE water sped by Bomba like a wild thing lashed by terror. Logs filled it, trees, bushes, ruins of huts torn up by the earthquake and flung into the mad tumult of the river.

Far up on the river bank stood Bomba, the jungle boy, staring with habitual stoicism at the awful spectacle. The body of a native floated by. Bomba started forward, moved by an impulse to help, only to stop when he saw that nothing more could hurt that bit of human clay. The native was dead.

The jungle boy watched the body disappear in the swirling debris, thinking in his heart:

"Bomba might have been that man, with no more life in him than the uprooted trees that pile upon his body. But Bomba is here. Bomba is safe."

Almost as though to remind him that this was no time to congratulate himself, the earth trembled and undulated, snakelike, beneath Bomba's feet, flinging him upon his face.

He lay there, arms outspread, feeling the ground crawl like a slimy thing. Had he been a native, he would have called upon the gods of the jungle to save him from the fate that threatened him.

Deeper in the jungle he heard a titanic rending and groaning, as trees toppled and fell to the ground with a crash. He looked about him apprehensively. He was filled with a deathly nausea as the earth writhed beneath him.

He struggled to his feet and supported himself with a hand against a tree trunk, while his eyes stared at the spot where had once been Jaguar Island.

The place it had occupied was now a wild waste of swirling waters. Clouds of steam rose high in the air, caused by the torrents of boiling lava that were still coming from the submerged volcano of Tamura, that dread volcano to which he would have been offered as a living sacrifice if it had not been for his quick wit and dauntless daring.

While he was pondering over the awful fate from which he had so narrowly escaped, Bomba felt the earth lift again in a terrible convulsion.

The ground began to slide from beneath his feet, and with a gasp the boy flung himself backward, twining his fingers in some of the creepers that hung from a tree above him.

He was only just in time. A portion of the river bank slid with a sucking sound into the water. Bomba's grip alone withheld him from being engulfed. The waters of the rushing torrent surged hungrily about his feet.

Not for nothing was the lad as strong as the jungle jaguar, as nimble as Doto, the monkey. He swung himself upward, and, as the tough vines held, found himself once more safe on ground that still remained firm.

"Bomba must get far from here," the boy muttered to himself. "This place is the dwelling of death. At any moment the earth may open or the river come higher and swallow up the ground and Bomba with it."

However, it was easier to determine on flight than to accomplish it. The quaking of the earth continued and Bomba, trying to run, was flung repeatedly to the ground, only to struggle to his feet again and stumble blindly forward.

But the peril of falling trees in the forest seemed to be even greater than that which might await him nearer the shore, and after a while he stopped, gasping for breath, awed by the forces of nature that were arrayed against him.

"Bomba must wait," he muttered to himself. "The earth will become quiet soon, and then he can go on."

Once more he stood near the bank, watching the waters rush madly by. Many animals had been caught in its ruthless grip and were swept along as helpless as chips upon the waters of a cataract.

In a few minutes Bomba had counted five pumas and seven jaguars. They tore wildly at the river bank, but their claws could find no hold.

"Even the puma and the big cat are helpless against the earthquake and the rushing torrent," mused Bomba. "It is strange. Jaguar Island has been swallowed by the hungry waters, and all that dwelt upon it are dead, all except Bomba. Perhaps—" and here a gleam lighted his somber eyes— "Bomba has been saved because there is still work for him to do."

The light faded from his eyes and the mouth of the jungle boy became straight and grim with purpose.

"One thing Bomba will yet do," he declared. "Bomba will meet Japazy, the half-breed. Bomba will tear from his lips the truth about his birth. Japazy must tell. Japazy shall tell. It is Bomba who says it."

It had been a bitter disappointment to the lad, after having braved numerous perils of the jungle, to find, on arriving at Jaguar Island, that the half-breed who held rule over the people and whom Bomba sought was absent on some mysterious errand.

But there was still hope. Japazy at least had not perished with the other luckless inhabitants of the doomed island. Somewhere in the world of the jungle the half-breed still lived, and Bomba had no doubt that some time he would find him and get from him the knowledge of his parentage —a knowledge that it seemed only Japazy had power to impart.

The thoughts of Bomba turned to Cody Casson, his one white friend, who had wandered off, half-demented, into the jungle. Where was the old man now? Had he survived, or was he lying even now, a mere heap of bleaching bones beneath the pitiless sun?

Bomba had hoped to find Japazy quickly, to gather the information for which he hungered and return on swift feet to the village of the native chief, Hondura, who had promised to search for Casson and take good care of him if found. Perhaps, Bomba comforted himself, the poor old man was now safe with the chief. But it was a forlorn hope, and Bomba knew it.

The lad aroused himself from his musings abruptly. From somewhere had come a faint cry. Or had he imagined it?

"Help!" came a native voice in wild appeal from the river. "Help or I die!"

Bomba's eyes searched the surface of the torrent and saw, borne toward him at amazing speed, the form of a native clinging to the trunk of a tree.

The fingers of the man were cramped and weary. They were slipping from the slimy trunk. In another moment he would let go and be helpless in the grip of the flood, a bit of human driftwood carried on to destruction.

With a sharp exclamation, Bomba darted down the river bank. He lost his footing and slid some distance toward the water, in danger of meeting the very fate he was trying to ward off from another.

But he caught at some tough vines and halted his mad descent on the very brink of the stream.

The native was within two feet of him, still clinging weakly to the log. The terror of death was in his eyes, and the agonized appeal in those eyes went straight to Bomba's heart.

Lying face downward on the bank, maintaining a strong grip on the vines, Bomba swung his feet as far over the water as they would reach.

"Take hold with your hand!" he cried to the native. "It is the one chance. Quick!"

With a strength born of desperation, the native flung himself forward, at the same time releasing his hold upon the trunk. His fingers touched one of Bomba's feet, wound themselves about it and held on frantically.

Bomba felt the earth quiver beneath him. What if the bank should break loose and slide into the river as part of it had done before! Then his plight and that of the man he was trying to save would be hopeless.

Slowly, inch by inch, he made his perilous journey upward until his fingers closed on a sapling. This gave him the purchase that he needed.

Quickly now he pulled himself up to level ground. Then he reached out a hand to the Indian and drew the fellow up beside him.

For some time the Indian lay panting and speechless. Bomba saw that the man was on the verge of utter exhaustion. A few moments more and he would have been simply one more inanimate body that the river had claimed as its victim.

He was a tall, lank fellow, this native, thin almost to the point of emaciation. He had hawk-like features, a firm jaw, and an expression less brutal and more intelligent than most of the folk in this part of the jungle with whom the boy had come in contact.

The man looked up at him. His eyes were dulled by suffering and terror, but behind this veil burned a light of gratitude.

"It is to you that Gibo owes his life," the man said in a guttural voice. "Because of that the life of Gibo is yours to do with what you will. You are master, Gibo is slave."

The deep emotion in the voice of the native warmed the lonely heart of Bomba. He smiled and said slowly:

"My name is Bomba. Bomba is glad that he could save the life of Gibo. But Gibo owes Bomba nothing."

"Gibo owes Bomba his life," the native repeated doggedly. "That is not nothing. Bomba is master, Gibo is slave. Gibo will go where Bomba leads."

"Has Gibo seen Bomba before?" asked the jungle lad, who did not remember having seen the man among the natives of Jaguar Island.

"Gibo looked upon Bomba from afar," was the reply. "He did not dare go near the stranger who could put his hand on the cooanaradi and not be bitten. He thought the stranger must be a god."

Bomba could with difficulty restrain a smile as he recalled a ruse that had undoubtedly saved his life while he was in the house of Japazy on Jaguar Island. He was on the point of explaining what had seemed to the superstitious natives a miracle—how he had escaped death from the poison fangs of a cooanaradi. But he reflected that it might be well to have Gibo remain under the deep impression that the incident had produced.

"Bomba can do many things," he announced gravely. "It was not well that the people of Jaguar Island planned to kill Bomba. Tamura was angry and sent out his floods of fire and punished them. Bomba is still alive, while the people of the island have now gone to the place of death."

"It was bad of my people to do harm to the stranger," confessed Gibo humbly. "But Gibo had no part in the councils of the elders."

Bomba was about to answer when suddenly he jumped to his feet, eyes fastened on the rushing river.

Gibo followed the direction of Bomba's gaze and gave vent to an exclamation of terror.

Down the river, hurried on by the rushing torrent, came a swarm of alligators.

"Run!" shouted Bomba to Gibo. "They are headed for this spot! To stay in their path is death!"

THE alligators were being carried by the current to a point of land that jutted out from the mainland about two hundred feet from where Bomba and Gibo stood.

It was certain that many would be thrown upon this point, and as they could run almost as fast on land as they could swim in the water, the peril to the two wanderers was manifest.

The beasts were crazed by fear. Ordinarily they would have sought refuge from the great convulsion of nature that was going on by sinking to the mud of the river bed and waiting there until the tumult of unchained forces was over.

But the quake had extended beneath the river bed and had shaken it in the same way as the dry earth. And the flood of molten lava that had poured into the stream had made it boiling hot in places, so that the creatures were scalded and blistered.

In their fright and bewilderment they had surrendered themselves to the current that promised at least to carry them out of range of the disaster.

The point of land was reached with incredible swiftness. Many of the huge beasts were flung up on the shore. Right in their path were two of their natural enemies. The caymans charged them savagely. Before that attack Bomba and Gibo fled faster than they had fled from the fiery wrath of the volcano.

The ground still quaked and quivered underfoot. It was almost impossible to run. Again and again the fugitives fell to the ground, expecting to feel the snap of vicious jaws. Again and again they struggled to their feet just in time to avoid a hideous death.

If the brutes had been endowed with sufficient cunning, some could have run in different directions so as to cut off the retreat of the fugitives and surround them. But they lumbered on behind in a mass, often knocking against each other and impeding their common progress.

But they were running close to the ground and could not be so easily upset as the tall human creatures they were pursuing. And they had a reserve of strength not possessed by their human quarry. Sooner or later these advantages were bound to tell.

Bomba, looking over his shoulder, could see that the alligators were gaining. Their eyes seemed to the excited boy like points of fire, ablaze with malignity. Their jaws were open, showing the terrible rows of teeth with which they were garnished.

Bomba shouted hoarsely to Gibo, who ran close beside him, fear adding wings to his feet.

"Up in the tree!" Bomba commanded. "Quick! It is our only chance."

The branch of a great tree swung low overhead. Bomba gripped it and flung himself aloft. Even as he did so, the jaws of a cayman came together with a grisly snap, missing the ankle of the jungle lad by an inch.

Gibo followed his leader's example. But he screamed as he did so, and as he wound his legs about the branch and clung to it desperately Bomba saw that blood dripped from his leg.

"It is but a scratch!" panted Gibo. "The teeth of the cayman are sharp. Gibo is lucky that he has his leg."

The man had courage! Bomba smiled and crawled to a heavier portion of the bough, motioning the native to follow.

"The branch bends," he said. "If it breaks, the lives of Bomba and Gibo will end."

Beneath them circled the furious caymans. Their wicked eyes gleamed savagely. Their horrible jaws opened and closed with a hungry sound of grating teeth, a sound that sent a shiver to the two who had so narrowly escaped a hideous death.

While the alligators rage around the tree trunk, balked momentarily of their prey yet hoping to get them in the end, it may be well, for the benefit of those who have not read the preceding volumes of this series, to tell who Bomba was and what had been his adventures up to the time this story opens.

Bomba, now about fourteen or fifteen years of age, could not remember ever having had any home but the jungle. He had been brought up in a little hut in the Amazonian wilds, under the guardianship of Cody Casson, an aged, white naturalist, who had chosen to withdraw from civilization and bury himself with his charge in the wilderness.

Casson had always been kind to Bomba, though most of the time he was withdrawn into himself, and would sometimes let days at a time go by without speaking, except in monosyllables. When Bomba grew out of infancy, Casson seemed to wake to a sense of his obligations and began to give the boy the rudiments of an education.

But this instruction had not progressed far before an accident to Casson brought it to an abrupt end. Confronted one day by an immense anaconda that was threatening to attack Bomba, Casson had fired at the reptile with an old rifle. The weapon had burst, and some of the flying missiles had struck Casson in the head. The snake had been wounded and had retreated, and Bomba had dragged Casson back to the cabin, where he nursed him back to physical health. But the old man's mind had been affected by the explosion, and from that time on he was half-demented. His memory, especially, was almost entirely gone.

After that the care of the little household had fallen mainly on Bomba, and the responsibility, together with his remarkable strength of muscle and quickness of mind, had developed him rapidly into a splendid specimen of boyhood. He was now stronger than most men, clean-cut, tall and powerful. He had had to match his strength and cunning against the wild beasts and reptiles of the jungle and against savage tribes of men. He was keen of vision, swift of foot and quick of wit.

His usual clothing was the short tunic worn by the native Indians, home-made sandals and a puma skin suspended from his shoulders across his chest—the skin of Geluk, the puma, which Bomba had slain, when it was attacking Bomba's friends, the parrots, Kiki and Woowoo. His hair was brown and wavy, his eyes also brown and his skin was as bronzed as that of an Indian.

The outside world was a sealed book to him. He loved the jungle and its fierce fight for survival. But at times he was oppressed by a great loneliness. He had no companions except Casson and certain of the birds and monkeys with which he had made friends to such an extent that he could largely understand them and they him. The natives of that part of the jungle, though not hostile to him, yet kept aloof, and Bomba did not seek their companionship.

For in his heart the boy knew that he was white and different from the men and women with whom he came in contact. The call of the blood kept tugging at his heart. He knew nothing of his parents, not even whether they were still alive. But he longed to know of them with a yearning that could not be quenched. Again and again he had questioned Casson, but the latter, though he would have gladly given the information if he had been able, could not recall the facts. From certain mutterings of the old man, Bomba conjectured that his father's name must have been "Bartow" and his mother's name "Laura." Further than this, which in itself was only a guess, the lad knew nothing.

How Bomba by chance came across two white rubber hunters, Gillis and Dorn, and won their gratitude by saving their camp from an attack by jaguars at night—the craftiness with which he trapped the dread cooanaradi that sought his life—how he drove off the vultures that were attacking his friends the monkeys—how with the aid of his jungle friends he drove off the head-hunters who were besieging his cabin—these and other adventures are narrated in the first volume of this series, entitled: "Bomba, the Jungle Boy; or, The Old Naturalist's Secret."

In one of his semi-lucid moments Casson had told Bomba that Jojasta, the Medicine Man of the Moving Mountain, could tell him the secret of his birth. Bomba resolved to go and see this sinister personage, though he was warned that he took great risks in attempting the journey.

He went, nevertheless, and found that the dangers had not been exaggerated. He underwent perils by fire and flood and earthquake, in the course of which he was enabled to save a white woman, a Mrs. Parkhurst, from the hands of the savages, and restore to her later her son, Frank, who was lost in the jungle. But after conquering almost insuperable obstacles, Bomba came at last into the presence of Jojasta only when the latter was at the point of death.

The medicine man was able only to gasp out that the information Bomba sought might be obtained from Sobrinini, the witch woman of the Giant Cataract.

This necessitated another journey even more full of peril than the former. But Bomba was undaunted, and set out determinedly on his quest. He was captured by head-hunters, who had also carried away Casson, and was doomed to a cruel death by torture. But he escaped, leading his fellow captives with him. He found Sobrinini on her island of snakes and rescued her from a revolt of her savage subjects. But she was half-crazy, and Bomba could gather little from what she said except that his conviction was strengthened that the mysterious "Bartow" and "Laura" were indeed his father and mother.

Lesser souls would have been daunted after so many disappointments, but Bomba followed a clue hinted at in Sobrinini's ravings that Japazy, the half-breed ruler of Jaguar Island, could tell him of his parentage, and set out in search of that personage. Death clutched at him at almost every stage of his journey, death by alligators, death by jaguars, death by serpents. And when after unexampled adventures he finally reached Jaguar Island, he found that Japazy was gone on a mysterious mission, which Bomba conjectured had something to do with an ancient and rich sunken city with towers of gold. The natives, suspicious of Bomba's mission, planned to slay him before their master's return. How they were thwarted by Bomba's own quick wit and the opportune coming of an earthquake and volcanic eruption is told in the preceding volume of this series, entitled: "Bomba, the Jungle Boy, on Jaguar Island; or, Adrift on the River of Mystery."

And now to return to Bomba in the fearful plight he found himself with alligators swarming beneath him and thirsting for his blood.

He and his companion crawled cautiously toward the trunk of the tree, praying that the bough that held their weight would hold. Fortune favored them, and having reached the trunk, they climbed still higher and ensconced themselves in the fork of the tree.

Here they were safe for the moment. Only then did they relax, thankful that their hearts still beat and that their lungs still breathed the air of the jungle, hot and sulphurous though it was.

"Is Gibo badly hurt?" Bomba asked the native.

For answer, Gibo displayed the wounded ankle, from which the blood still dripped.

"It is but scratch," he deprecated. "The teeth of the cayman scraped the skin from Gibo's leg, but did not touch the bone. Because his leg is still whole, Gibo could dance and sing."

Bomba smiled, for he was growing to like the native more and more and was glad in his loneliness to have some one with whom he could hold human speech.

"Gibo is brave," Bomba said, "and Gibo has need for all his bravery, for there are bad things that happen in the jungle."

Even as he spoke there came another quake, and the tree bent suddenly halfway toward the ground. Bomba and Gibo gripped the trunk wildly to keep from being flung off into space.

"It is the earth!" gasped Bomba. "It writhes again. It seeks to kill us by its anger."

But the tree righted itself with such suddenness that Bomba and Gibo were flung violently against the trunk and clung there desperately, panting for breath.

In that second when the branches had bent earthward they were almost within reach of the caymans, but the brutes, fearing that the tree was falling, had scuttled away and had missed their chance. Now they came back again, gazing upward viciously.

"They will not run the next time," declared Bomba. "We must climb higher."

It was not easy to climb the tree, for the branches still swayed as in a great wind.

But Bomba and Gibo were like monkeys. They swayed with the swaying of the tree, wound arms and legs about the branches and held tight until the trunk had regained some measure of stability.

They were halfway up when Bomba stopped, panting.

"This is far enough, Gibo," he called to the native, who had stopped on a lower branch. "Our enemies, the caymans, are frightened. See! Even now they fall over one another in trying to get away. Soon we can go down and be safe."

Gibo looked below and saw that what Bomba had said was the truth.

The alligators, bewildered by the disappearance of their intended victims in the thick foliage, terrified perhaps by the fierceness of the latest quake, or sensing some menace that Bomba could not discern, were departing in almost panic haste.

But when Bomba would have rejoiced, a sharp cry from the native warned him of fresh danger.

He peered through the leaves and saw Gibo crouched against the trunk, staring at something that was creeping stealthily toward him.

"Ayah!" exclaimed the native in dismay. "It is the big cat! Gibo is lost!"

The hand of Bomba flew to his machete.

BOMBA'S instinctive action was instantly arrested by the thought that he could not use the weapon in time to save the life of Gibo.

As quick as thought Bomba dropped to the branch beneath and seized the jaguar by the tail.

At that instant the big cat sprang at the native. But Bomba held desperately to the tail, bracing himself for the tug of the great body.

The jaguar howled as he felt himself thrown out of balance. He felt himself slipping and tried frantically to retain his hold upon the bough. But Bomba tugged with all his might, and for one instant held the jaguar by the tail suspended over the ground. Then with a cry of triumph he sent the brute whirling and spinning to the ground beneath.

At this exhibition of nerve and strength the Indian stared at the white lad, awed beyond all speech. He glanced down through the branches of the tree and saw the great cat go limping away with its tail between its legs.

"Who are you?" asked Gibo fearfully of the jungle lad. "Who are you who can swing the jaguar by the tail and make it slink away in terror? Surely, he who does such things must be lord of all the jungle."

"I am Bomba," replied the lad simply. "All my life I have roamed through the jungle, fighting with the puma and the jaguar, the alligator and the boa constrictor. I have grown strong as I have grown in height. But one must be strong to live the life of Bomba."

His voice held a note of bitterness, and Gibo stared at him without understanding.

"Ayah! You are strong," he muttered. "Never have I seen such strength before. No warrior of our tribe could match it. The big cat feared Bomba as he would a god that sent down bolts of thunder out of heaven."

"It feared more the strange rumbling and growling of the earth and the swaying of the tree which he did not understand," returned Bomba moodily. "It is of those things that it is afraid and not of Bomba."

But the Indian would not accept this explanation. His superstitious mind sought to invest Bomba with supernatural powers, and from that time on he looked upon the jungle lad with deference and awe as a superior being.

"Twice has Bomba saved the life of Gibo," the native said gravely. "From this time the life of Gibo will be spent in the service of Bomba. Gibo will be the slave of his good friend."

"Bomba will be glad of the company of Gibo," replied the lad, with equal gravity. "For Bomba is sometimes very lonely in the jungle. But now our enemies depart and the sun is high in the heavens. We must go and find some place of refuge before darkness falls upon the jungle."

Nevertheless, they lingered for a short time, reluctant to trust to the apparent safety of the ground beneath. Within the shadows of the trees and underbrush might still be lurking the caymans or the jaguar. But the branches of the tree could not shelter them forever, for a tree is no refuge from the beasts that climb, and night would be full of menace from prowling enemies.

So at length they descended cautiously and stood for a time at the foot of the tree, alert for any sound that might betray the presence of a foe.

The ground was steadier underfoot now. The fury of nature seemed to have spent itself. Reassured by the stillness of the jungle, Bomba and Gibo crept forward, their eyes and ears at tension for the slightest sound that might be alarming.

They were soon convinced that the retreat of their foes had been a real one and that for the present at least they had little to fear.

They went on then more swiftly, thankful that the sickening motion of the earth beneath them had ceased. But Bomba was not headed toward the camp of Hondura.

He had at first thought that he would go to the maloca of the good chief and then return to resume his search for Japazy. But reflection had brought a change of purpose. Why provoke once more the dangers of a long journey to Hondura and return, when he was at this moment nearer than he might ever come again to the half-breed of whom he had come in search?

So he turned his steps in what he knew to be the general direction in which lay the sunken city with the towers of gold of which he had been told. He felt sure that somewhere in that vicinity Japazy was to be found.

That is, if he were still alive. Bomba had no means of knowing how far this great convulsion of nature had extended. For all he knew, it might have embraced the zone where lay the sunken city, and perhaps Japazy also had met the fate which had overwhelmed the greater part of his subjects.

This chance, however, had to be taken, and the lad went on with resolution, determined not to stop until he had achieved the object of his quest or learned at least that the quest was hopeless.

Gibo followed silently where Bomba led. Evidently the Indian had firmly established himself in thought as the slave of this masterful stranger, and recognized no right of his own to question the purpose of his leader.

They found progress very difficult, for there were great fissures in the earth that they could only get around by making long detours. Fallen trees blocked their path, and the machete of Bomba was called into frequent requisition to hack a way through the branches.

Night came and found them almost exhausted.

"We must rest," declared Bomba. "But where shall we find shelter?"

Gibo looked about him and gravely shook his head.

"Gibo's eyes have seen no caves," he answered. "There is no shelter, unless we climb again into a tree and trust to the gods of the jungle to keep us safe through the night."

Bomba looked about for thorn thickets. But in this part of the jungle there was none so heavy and thick that wild beasts could not force their way through.

He shook his head doubtfully.

"The tree is a poor chance to take," he said. "But since there is no cave or thicket of thorns in sight, we shall have to trust to it this once. But first we will eat the eggs of the turtle that we have gathered on the way."

They ate the eggs after they had roasted them over a small fire. And here again Gibo was filled with awe at the resources of his companion. For, as the native was about to gather dry leaves and got out the hard pointed wood and bowl with which he was accustomed to produce a spark, Bomba stopped him.

"This is better," he said, as he drew from his pouch one of the precious boxes of matches that Gillis and Dorn had given him.

He struck a match, and as the light flared up Gibo jumped back with a cry of surprise and alarm. He had never seen a match in his life.

"It is magic!" he cried, his voice trembling.

Bomba smiled. It was not for him to disclaim anything that might give him a stronger hold on his companion's allegiance.

They ate heartily, and when they had finished their meal climbed into the branches of the tallest tree they could find and there disposed themselves to spend the night.

Though asleep, Bomba's subconscious mind remained on guard. He had dwelt so long in the jungle that his senses were almost as acute as those of the wild beasts that infested it.

For a long time he slept, his arm about a heavy bough, his legs twined around some branches beneath, his head dropped forward on the puma skin that covered his chest.

But through that deep sleep of utter weariness a warning stalked in Bomba's mind, bringing him little by little from the unconsciousness of slumber.

Then he found himself wide awake, every nerve alert, eyes staring fearfully into the blackness of the jungle. Those eyes, trained to pierce the jungle, could at first see nothing. His ears, practiced in catching the slightest sound, heard nothing.

Yet, in defiance of his senses, Bomba knew that death was treading somewhere in the jungle, death that crept nearer and nearer the tree in which he and the Indian had sought refuge.

A faint rustling in the branches near him told him that Gibo too was awake and aware of danger.

Bomba spoke softly.

"Does Gibo see anything in the jungle darkness?" he asked.

"The eyes of Gibo see two other eyes," the native whispered back. "Yellow eyes that gleam like jewels in the night."

"A puma!" muttered Bomba. "He climbs a tree as the monkey climbs. Now must we fight for our lives."

But the yellow lights grew, like so many fireflies, until Bomba and his companion realized that there were not two eyes only in that enveloping darkness, but a dozen. They were hemmed in by a band of hungry pumas, than which there is no more vicious beast in the jungle.

"Now indeed are we lost," muttered Gibo. "One we might fight or perhaps two, but against six we are helpless."

"Only one can climb the tree at a time," declared Bomba stoutly. "We will kill them as they come. It is not yet time to give up hope."

With the words, Bomba swung himself to the branch below the Indian, stretched himself flat upon it and drew his machete.

It was a formidable, two-edged weapon, nearly a foot long and ground on either edge to razor-like sharpness. Again and again it had saved Bomba's life, and he trusted to it now.

Under other conditions he would have relied upon his bow and arrow. But, owing to the thick foliage and numerous branches, it was impossible for him to find elbow-room for that weapon.

His head was cool, his arm steady. He knew that the odds were against him. But so they had been many times before, and his indomitable courage had carried him through unscathed.

And if he had to die, he would die fighting. Death, after all, was only passing in the dark from one lighted house to another. Why should he fear it?

A rustling in the branches overhead caused him to draw back his machete, ready to strike. Was it possible that danger threatened also from that quarter?

But it was only Gibo. With the agility of a monkey he descended the tree till he reached a bough alongside of that of Bomba. There he rested and drew his jungle knife, which, while not as formidable as Bomba's machete, was capable of terrible execution.

"Would Gibo die?" asked Bomba in some surprise, for he had thought that in this encounter he would have to work alone. He had not much faith in native assistance.

"Bomba has twice risked his life for Gibo," the native answered simply. "Now Gibo would not see Bomba fight with death alone. His life belongs to Bomba."

There was no time for further speech. The ring of pumas had closed in about the tree. Out of the darkness the yellow eyes gleamed.

One puma approached the tree and, like a great cat, reached up and sharpened its claws upon it. Then, with a deadly purpose, the beast began to climb.

Bomba stiffened and his eyes blazed like live coals. His grip closed more tightly on the hilt of the machete.

Up and up came that creeping death. Then, directly beneath Bomba, a great head thrust itself through the foliage.

The yellow eyes of the puma gleamed wickedly as they fell upon Bomba's crouching figure. With a fierce growl the brute struck. But the arm of Bomba was swifter even than the paw of the beast.

The machete flashed and bit cruelly through flesh and bone. The paw of the puma was severed completely from the body.

With a howl of rage and pain the great brute let go its grip with the other paw and went whirling to the ground.

"The machete of Bomba is sharp," exulted Gibo. "That puma will not climb a tree again."

"The knife of Bomba need be sharp to fight off the pumas," replied the lad. "See!" and he pointed his dripping weapon through the branches of the tree. "They come again to the attack."

But it was Gibo who was nearer to the second puma when it reached their place of refuge. His eyes was steady and his arm strong. Straight through the yellow eye of the puma went the blade of the knife. The point pierced the brain and the animal fell with a strangled howl to the ground in the midst of its mates.

"Two!" said Bomba grimly. "Well struck, Gibo! Your heart has courage and your arm has power. Together we may yet fight off the beasts who would drink our blood."

A third puma met the fate of his predecessors, but this time not without damage to his slayer. For a wild sweep of its claws tore a long ridge of flesh along Bomba's arm from the shoulder to the elbow.

"A little more and he would have ripped out the heart of Bomba," muttered the lad. "It is too bad that the arm drips blood. The next blow will be weaker. But Bomba still has another arm, and that can drive the machete with almost the same strength as the other."

Ordinarily the fate that had befallen the slain and wounded pumas would have struck panic to the hearts of the others, and they would have drawn off. But now they seemed more enraged than dismayed and pressed close to the tree, growling defiance.

The situation grew desperate. Bomba well understood the reason for the unusual persistence of the pumas. The small game had been driven from that region of the jungle by the awful convulsions of the earth. The pumas were hungry and had followed in numbers the scent of human flesh. Now that they had their prey apparently trapped, they would not give up easily the prospect of a satisfying meal.

Now not one but two pumas began to ascend the trunk on opposite sides. Possibly this was due to strategy, their instinct telling them that one might have free scope for attack while their enemy was busy with the other.

Bomba was growing weak from loss of blood. His injured arm hung heavily from the shoulder, as though weighted with lead. He shifted the machete to the other hand.

The great paw of the leading puma flailed through the branches toward Bomba.

But Gibo had noted the shifting of the machete and surmised that it would put Bomba at a disadvantage. With a desperate cry the Indian launched himself forward, all the strength of his body behind a swinging blow.

The knife struck the forehead of the brute straight between the eyes, crushing through bone and sinew to the brain.

But as he struck home the puma lashed one paw out blindly and dealt the Indian a powerful blow.

Then the beast fell, striking the other climbing puma and carrying it to the ground with it.

There was another crash, and Gibo, who had been temporarily stunned by the puma's blow, whirled through the branches and fell directly upon the body of one of the slain brutes.

Disconcerted by his sudden appearance, the pumas gave back. Then they rallied again to the attack. Fate had delivered one of their enemies into their clutches.

Or so it seemed.

But the next instant another figure dropped from the tree and landed lightly on its feet, a figure whose arm dripped blood, whose eyes blazed terribly, whose knife rose and fell so swiftly that the eye could scarcely follow it.

For a moment the pumas, daunted by the furious attack, gave ground. But only for a moment. The next, maddened by the sight and smell of blood and with roars that echoed and reechoed through the night-enshrouded jungle, they charged upon the enemy.

Lips drawn back from his teeth, Bomba met them. As the first puma sprang, Bomba drove home his machete with a terrible thrust between the ribs and dodged nimbly to one side to meet the attack of his next antagonist.

Standing above the fallen body of Gibo, Bomba was fighting like a madman.

But this could not last long. He was panting. His lungs seemed bursting. He was growing faint from loss of blood.

Then came a sound like the surging of a great sea.

THE pumas heard the sound too, for they drew back from Bomba and stood crouched, ears flattened, growling a low defiance.

Gibo had struggled to his feet and now tugged at Bomba's arm.

"Death comes in a tide," said the native. "The caymans advance like a flood. To the tree, quick, or we are lost!"

Even as Gibo spoke, the first ripple of the tide of death broke through the trees and was almost upon them. Alligators advanced in great numbers, lured by the smell of blood and the sounds of conflict.

At sight of this new enemy, the drugged feeling that had been stealing over Bomba relaxed its grip. He leaped for a low hanging branch and swung himself from the ground just in time to escape the snapping jaws of one of the reptiles.

"Quick, Gibo!" shouted Bomba, reaching out a hand to the native, who was still confused and dizzy from his fall.

The pumas turned to face the new enemy and a terrible battle ensued. They were outnumbered, but fought at bay with snarling fury. It was a conflict to chill the blood of the two onlookers, who watched it fearfully from their vantage point in the tree.

"The gods of the jungle have been good to us," murmured Gibo. "They have saved our lives from the pumas."

"It is well," acquiesced Bomba. "But we must not stay here. Let the pumas and the caymans destroy each other. But we must get far away while they are forgetting about us in their hate of one another."

"We cannot go on the ground," objected Gibo dubiously, as he viewed the scene of carnage beneath.

"No but there is another way," said Bomba. "The trees are thick here and we can swing ourselves from tree to tree like the monkeys. In a little while we will be far from here."

So, while the grim battle to the death raged at foot of the tree, Bomba and his companion swung themselves along from one tree to another until the sounds of conflict grew faint in their ears and at last ceased altogether. Then they descended and threw themselves upon the ground, utterly exhausted.

By this time there was little feeling left in Bomba's right arm. For an hour past he had availed himself wholly of the left, as he swung from branch to branch.

Now as he leaned his head against the trunk of a tree a strange dizziness assailed him. The faint, lacy tracery of bush and vine grew ever more indistinct before his dimming eyes.

He fought the feeling off with all his might, but still the queer haziness gained on him.

"Can this be death?" he murmured to himself drowsily. "If so, it is not hard. Bomba is not afraid—"

At what must have been a long time afterward, Bomba awoke to find Gibo bathing his forehead with cool water and bending anxiously above him.

"The master still lives," said the faithful Indian with a great sigh of relief as he saw that the boy's eyes were open. "The ground is wet with the blood of Bomba. But the gods will that he should live. Good! Gibo is glad."

"It is not yet time for Bomba to go to the place of the dead," replied the lad gravely.

He looked down at his arm, which felt much more comfortable than it had before.

"Gibo has bandaged the arm of Bomba," he said gratefully. "It was well done."

Gibo had indeed done his work well. He had bathed the wounded arm with water from an adjacent stream and had wrapped it about with wet leaves and a plaster of river mud, using a strip of cloth that he had torn from his tunic and binding the rude bandage in place with stout vines that he had cut down with his knife.

The result of his ministrations was soothing to Bomba, and, though still dizzy, he felt refreshed and strengthened.

"With the help of Gibo, Bomba can sit up," he said.

Instantly the sinewy arm of the native was slipped beneath the jungle boy, helping him to a sitting posture.

"We must eat, Gibo," declared Bomba, all the needs of the situation coming back to him. "And then while the daylight lasts we must continue on our way."

So, while Bomba rested with his back against the tree trunk and his faithful machete ready at his hand, Gibo went into the surrounding region to look for food.

He returned in a short time, triumphantly bearing a small peccary that had evidently been struck and killed by a falling tree during the cataclysm of the day before.

"The pig is small but its flesh is sweet," observed Gibo, laying his prize beside Bomba. "Gibo will build a fire and the pig shall roast upon a spit. Gibo is swift in the service of his master."

The native was as good as his word, and before many minutes had passed the most succulent parts of the peccary, thrust through with a sharp-pointed stick, were sputtering and broiling over the dancing flames of a cheerful fire.

They ate heartily of the well-roasted meat, and when they had finished Bomba felt refreshed in body and spirit. He was in such splendid physical condition that he recuperated quickly from the effects of his wound. He could feel the blood flowing strongly through his veins, and he was not only ready but eager to start again upon his quest.

The meat of the peccary that was left over they partly roasted and thrust into the pouches of their belt. However scarce game might prove, they were fortified with food for a couple of days, at least. Gibo flung wet leaves on the dying embers of the fire and once more the twain plunged into the sinister recesses of the jungle.

All Bomba's thoughts were engrossed with the task that lay before him, and hours passed without his uttering a word. Then he woke to the consciousness that Gibo was with him. He looked at the native and saw that in his eyes was an unspoken question.

"What is it that Gibo would ask of Bomba?" inquired the lad kindly.

"It is not for the slave to ask questions of the master," returned Gibo humbly.

"After what has passed between Bomba and Gibo, Gibo is free to ask what question he will," declared Bomba. "Let Gibo speak freely and Bomba will answer."

"Then," ventured the Indian, "Gibo would know where the master is going? Gibo knows the jungle well, and he may tell the master what the master wants to know."

"As to where we go Bomba is sure," the lad replied. "As to how we go, Bomba is not so sure."

He paused for a moment in deep thought.

"Bomba travels swiftly as though pursued by all the evil spirits of the jungle," went on Gibo timidly. "If Gibo knew where the master goes, he might help to find the place."

"I go, Gibo," returned Bomba slowly, "to seek the abandoned city with the towers of gold that has sunk into the heart of the earth. I seek one who has gone there."

The Indian uttered a terrified cry and stood still for a moment as though almost tempted to flee.

"That is the city of the evil spirits, master," he said in a voice that trembled. "Surely, Bomba should avoid that evil place lest he be consumed by fire or strangled by the creeping serpent, the slave of the wicked spirits."

Bomba shook his head doggedly.

"I go to the abandoned city," he replied with a voice stern with determination. "There is one who dwells therein whose secret Bomba must make his own. I seek Japazy, the half-breed, who ruled over Jaguar Island."

The Indian sagged at the knees. It seemed as though all strength had left his limbs.

"But Jaguar Island also has sunk into the heart of the earth, and all who lived upon it, except Gibo, are smothered in mud or consumed by the fires of Tamuro," he whispered, fearing to speak aloud.

"All that were on the island," agreed Bomba. "But Japazy was not there. Bomba knows, for he waited in Japazy's house and Japazy did not come. Somewhere, he still lives, and Bomba thinks that he can find Japazy in the abandoned city with the towers of gold."

The dark skin of the native took on a sickly, greenish hue.

"DO not go, master," begged the Indian of Bomba. "It is to go to death."

Bomba laughed grimly.

"I will go," he said, and his voice was like steel.

"Bomba can do much," returned the native. "He swings a jaguar by the tail. He holds at bay the hungry pumas. He mocks the alligators that seek to devour him. But it is different when it comes to evil spirits. They can be defied by no one except the gods. But perhaps Bomba is a god?"

Bomba laughed and held out a firm brown arm, his left arm, toward the native.

"This is flesh and blood, Gibo," he declared. "Bomba is no spirit, but a boy. A little while ago did you not see him bleed? The gods do not bleed. No," he went on sadly, "Bomba is a boy who greatly needs a friend who is not afraid of evil spirits nor shrinks from danger. If Bomba can find such a friend, it is well. If not, he must go on alone, for his work is not yet done."

Gibo was silent for a moment. A struggle was going on within him. Then he raised his head, and in his eyes there was a faithful devotion that Bomba could not doubt.

"Gibo will not fear the evil spirits so long as Bomba leads the way," he said. "Bomba has thrice saved the life of Gibo, and Gibo would repay that debt."

They then continued on for some time without speech. Then Gibo said, as though the words were uttered against his will:

"If Bomba seeks the abandoned city with the towers of gold, Gibo can lead him to it."

Bomba's eyes glistened.

"Gibo knows the way?" he inquired.

"Gibo has cause to know and fear the spot," answered the Indian somberly. "But since the heart of Bomba is set upon this thing, Gibo will lead him to the place where the evil city once stood."

"Gibo is a good friend," cried Bomba. "Is it a journey of many days, Gibo?"

The native shook his head.

"Since yesterday the face of the earth is changed," he said. "There are valleys where there have been mountains, mountains where valleys stood. It is not only Jaguar Island that has sunk. All places are different from what they were."

"Yes," agreed the lad, "Bomba knows that to be true, for nothing looks the same in his eyes."

"And for that reason we must travel for many days away from the river and then toward it again before we can reach the place where the abandoned city stands," went on Gibo. "Many of the trails have been blotted out, but the moon and stars will help us find the way."

He paused and remained in thought for a few moments, while Bomba watched him intently.

"Gibo may be wrong," said the native at last. "He may lead Bomba to the place of evil sooner than he thinks. But whether the way be long or short, Gibo will do his best, if Bomba is willing to follow where he leads."

"Bomba is content," the lad replied.

They proceeded for some distance in silence, Gibo now leading the way. At length the Indian said, without looking back:

"Bomba has spoken of a secret that he must learn. Is it for this, then, that he would brave the evil spirits of the abandoned city?"

"This and this alone," answered Bomba moodily. "It would be hard for Gibo to understand, if Bomba did not tell him all the story of his wanderings."

"It is for the master to say," returned Gibo. "His heart may be less heavy if he tell. And it may be that Gibo can tell him some of the things that he would know. Gibo knew Japazy."

Bomba hesitated. Then the thought came to him that this man had known Japazy, Perhaps he had noticed something in the life of that sinister half-breed that might give Bomba some light on the problem that troubled him.

So, after a moment of hesitation, he said gravely:

"Bomba can trust Gibo. Gibo must repeat to no man what Bomba tells him. That Gibo must promise."

"Gibo promises that he will tell no man what Bomba may say to him," vowed the Indian.

So, going back to the very beginning when he had first realized that he was different from the natives of the jungle, Bomba recounted his adventures to Gibo. He told him of the tug at his heart to find his father and mother. He told him of the white people he had encountered, Gillis and Dorn, the rubber hunters, of Mrs. Parkhurst, the woman with the golden hair, of Frank, her son, to whom Bomba had been so strongly drawn. He told also of his conflicts with beast and serpent, the attacks of the head-hunters, the voyage to the Giant Cataract, to the Moving Mountain, and his rescue of Sobrinini from the Island of Snakes. As Bomba talked Gibo's eyes grew big with wonder and unlimited admiration.

"And Bomba braved alone the island of that hag, the witch woman, Sobrinini!" murmured Gibo. "There are demons on that island, too, demons in the form of writhing serpents. Was not Bomba afraid?"

"Bomba is not afraid of demons," answered the boy proudly. "Bomba does not believe in demons. Bomba is white!"

"And Bomba knows not why he came to the jungle nor why he must dwell here when he longs to live with his own people," continued the native musingly. "Bomba does not know who was his father. Nor does he know his mother—"

"Wait!" Bomba put his hand beneath the puma skin that crossed his breast and drew forth the picture of the lovely woman that he had brought with him from the dwelling of Japazy.

"Look!" said Bomba, and, being after all only a boy, his voice trembled as he spoke. "Bomba does not know, but he thinks that this was his mother."

The native paused and took the picture reverently in his hand. He studied it intently, his brows brought together in a frown.

"Gibo has seen this picture before," he announced at length. "It was in the house of Japazy."

"It was from the wall of Japazy that Bomba took the picture when Tamuro spoke in a voice of thunder," said Bomba.

"Gibo went one day to the house of Japazy," went on the native. "He had been sent by Abino to take a message to the chief. He saw Japazy standing before the picture, and when he turned away Japazy's face was not good to see."

"I think Japazy hated the woman of the picture," said Bomba. "And from what Bomba heard when he was on Jaguar Island he thinks too that Japazy slew Bomba's father."

"That Gibo does not know," replied the native. "But he thinks that this is the mother of Bomba."

"Why?" cried the lad. "What is it that makes Gibo speak such words?"

"Because the eyes of Bomba are like the eyes of the woman in the picture," replied Gibo as he handed back the treasure. "Though one pair is in the head of a woman and the other is in the head of Bomba, they are the same."

Bomba was speechless for a moment, while in his heart grew such a pride and hope and wonder that he was swept away on an overwhelming tide of emotion.

"Bomba never saw his mother, Gibo," he said in a broken voice; "or if he did, he does not remember."

"It is hard to bear." Gibo spoke gravely and in a soothing tone that brought balm to the lad's sore heart. "But some day Bomba will see his mother."

Bomba looked at the kindly face of the native and asked, with a catch in his breath:

"Why does Gibo say this thing, that some day Bomba will see his mother?"

"Because mothers are a blessing of the gods," returned Gibo simply, "and it is not written that the mother should be forever parted from her son."

Bomba did not question the logic of this. He felt hope rekindle in his heart. He thought of Frank Parkhurst and the golden-haired woman that was his mother. How Bomba had envied the boy his precious possession!

But suddenly the face of Bomba fell and his heart felt as heavy as lead.

"But Laura is dead!" he said, speaking his thought aloud.

Gibo shot a quick look at him.

"Laura is the woman in the picture?" he asked.

Bomba nodded.

"Yes," he replied. "Or so Bomba thinks. But Laura is dead."

"Why does Bomba say that? How does he know that it is true?" asked Gibo.

Bomba hesitated, and then realized suddenly that he did not know. Casson had not told him that Laura was dead, nor had Sobrinini. But Casson had spoken of her as "poor, sweet Laura" and from the grief in his tone Bomba had caught the impression that he was speaking of the dead.

"Bomba does not know," he said, as he met the gaze of Gibo fixed full upon him. "He has thought of his mother as dead, but she may still live upon the earth."

The native nodded gravely.

"It is not written," he repeated, "that a mother be forever parted from her son."

It was a slender thread to hang hope upon, but Bomba hugged it close to his lonely heart.

They went on for some time after this until they came to the banks of a river. The recent convulsions of the earth had caused the bed to be filled to overflowing by the waters of other streams that had been diverted into it, so that, while ordinarily peaceful enough, it was now a rushing torrent.

"Tell me, Gibo," Bomba asked, as the Indian frowned thoughtfully at the water. "If we follow the course of this stream, shall we come at last to the place of the abandoned city?"

Gibo shook his head.

"We must first cross this torrent that rages as though stirred up by evil spirits," he replied, and Bomba noted that he looked about him uneasily.

"But we cannot cross the torrent at this place," Bomba pointed out. "The strongest swimmer would be dragged under before he had taken ten strokes. Then, too, the piranhas would tear pieces from his flesh and caymans may be lurking in the water. It is too wide to fell a tree across, nor have we any boat that could make the passage. We could make a raft, but against the force of the waters we could not steer it to the other shore."

"And yet we must cross," muttered the native.

"We will cross," Bomba assured him. "But we must go further up until we find a place where the stream narrows. And let us go at once. For while we stand here we lose time, and Bomba's heart is troubled until he can have speech with Japazy."

The Indian assented, but his brow was troubled. The tumbling waters had revived again his superstitious fears. He was brave enough in matters that he could understand, but he shuddered before the unknown.

"What is in Gibo's heart?" questioned Bomba.

The native shrugged his shoulders as though to cast off the burden that was oppressing him.

"We are drawing near to the place of the evil spirits," he said. "Bomba does not fear, for Bomba is white. But Gibo fears because he is a caboclo and believes in the power of the evil ones to destroy his soul. But Gibo is the slave of Bomba, and where Bomba goes Gibo follows. We will go on."

Although Bomba did not actually fear the evil spirits, he had been reared in the jungle and there were times when he was inclined to believe that they had been active in laying pitfalls for unwary feet in the wild and trackless Amazonian wilderness.

But Gibo knew the country, changed as its topography was by the power of the earthquake. His sense of direction was as unerring as the scent of a hound. He led the way steadily through swamps and around waterfalls, sometimes through the topmost branches of the trees, toward the spot where the city with the towers of gold once gleamed in all its glory.

Breath was needed for their arduous task, and, except at rare intervals, neither of the pair spoke. Gibo was engrossed with his work as guide, and Bomba was so immersed in his own thoughts that he was glad to be able to ponder them without interruption.

As they penetrated further into the jungle the brushwood became so dense, the vines so tough and intertwined that more and more Bomba and Gibo depended for their progress on swinging from tree to tree.

They came upon tribes of apes, fiercer and stronger than any that Bomba had ever met in the part of the jungle where lay the cabin of Pipina. It was evident that the apes looked upon the travelers as interlopers and resented the intrusion on their solitudes. They had not yet ventured to attack the humans, but their attitude was decidedly hostile, and the creatures gathered in groups and chattered angrily as Bomba and Gibo passed.

"We must be careful, Gibo," Bomba warned his companion on one occasion when a tribe of monkeys had followed them for some distance through the trees, threatening at every moment to attack and only held back apparently by the caution of their leader. "If we were to hurt one of these monkeys, it would be bad for Bomba and his good friend Gibo."

"Bomba speaks good words," returned Gibo, looking up into a great tree beneath which they were passing. "It is not well—jump, master, jump!"

His voice rose to a scream.

Bomba obeyed instantly and leaped quickly to one side.

BOMBA had acted just in time, for even as he leaped aside, a giant castanha nut crashed to the ground on the very spot where he had stood a moment before. Had it struck him, beyond a doubt it would have fractured his skull.

He looked up and saw an ugly, grizzled face looking at him through the branches, the face of a great ape whose features were convulsed with rage and disappointment at having missed his kill.

Quick as thought, Bomba slipped his bow from his shoulder and fitted an arrow to the string. At the motion the ape retreated through the branches. His huge body offered an easy target, but Bomba held his hand and slowly lowered the bow.

"No," he said. "Bomba could kill him but he will not. A hundred might come in his stead. It is well not to make them too angry."

The native nodded his head approvingly.

"They are wise words that Bomba speaks," he replied. "We must go softly, for in this part of the jungle the beasts are wary and savage and easily offended. Even the parrots scream at us, and there is no friendship in their screams."

"It is not so with the monkeys and the parrots in the place where Bomba dwelt with Casson," observed Bomba. "There they are good friends of Bomba. They come to hear him play music on the magic pipe. They talk to Bomba and Bomba talks to them in their own language. Once or twice they have even saved the life of Bomba. But here all look on us with the eye of hate."

Here the lad fell to musing moodily and no words passed between him and Gibo for a long time.

Bomba was very sad. All his friends he had left behind him. They were pitifully few, but they were all he had and he loved them. There were Casson; Pipina, the squaw; Hondura, the friendly chief, and his little daughter Pirah; Po-lulu, the friendly puma; Doto, the monkey; Kiki and Woowoo, the parrots. All these good friends were far away. He might never see them again. He had with him now only Gibo.

After a long detour, almost a semicircle, they came out once more on the bank of the river. The torrent had subsided. Once more the stream ran sluggishly between banks overgrown with rank vegetation.

Bomba pointed with eager fingers to a tree trunk that stretched across the river.

"We can cross the stream now, Gibo," he said. "And once upon the other side, shall it not be soon that we find the spot on which once flourished the city with the towers of gold?"

"That shall we, Bomba," returned the Indian. "We are now but a little way from the place that Bomba's heart desires. If Bomba is patient, Gibo will keep his promise."

"Gibo speaks well," cried the lad. "Come, let us cross to the other bank."

The tree trunk was smooth and overgrown with moss. But Bomba and Gibo, swift and surefooted, crossed it without a slip.

Once upon the farther side of the stream, Bomba felt a rising sense of elation. At last he seemed to be nearing his goal. Soon, perhaps, he would find the half-breed, Japazy! Soon, perhaps, he would know the answer to the question that burned in his soul!

But Gibo was beginning to lose some of his stoic calm. Bomba noticed that the man looked often and fearfully over his shoulder into the shadows of the jungle, that the sharp snapping of a twig underfoot caused him to jump.

"What is it that Gibo fears?" asked the lad at last, curiously. "No jaguar is stalking us through the jungle that Gibo should look behind him so fearfully. No angry tribe of monkeys follows overhead. No serpent hangs with hissing tongue from the branches of a tree. What is it then that Gibo fears?"

"It is something worse than poison snake or creeping jaguar that Gibo feels in the air around him," answered the native. "There are evil spirits in this place, demons that steal away the hearts and minds of men. It is these that Gibo fears, and he would turn back, if it were not for the promise he has given to Bomba."

"Bomba would not keep Gibo against his will," said the jungle boy earnestly. "Bomba does not fear the evil spirits because he is white and does not believe that there are such things. But Bomba would not have Gibo suffer for his sake. Turn back then, Gibo, before it is too late and Bomba will find his way from this spot alone."

But the Indian shook his head.

"Gibo has none to mourn him if he never returns," he said. "Gibo is alone in the world, and since his life has been saved by Bomba it is to Bomba that he gives it."

Seeing that the grateful Indian would not be swerved from his purpose, Bomba urged no more and they went on swiftly together toward the site of the sunken city. They had not tasted food since early that morning, and both were beginning to feel the gnawings of hunger.

They had but a few scraps of food remaining in their pouches, and it was incumbent on them to replenish their supply.

"We must have food so that we shall be strong when we stand in the presence of Japazy," said Bomba. "We will get enough now so that we shall not have to think of it again before we reach the abandoned city."

But food was hard to find just then in that wild region, for most of the animals had fled from it in terror during the earthquake.

After an hour of fruitless search Bomba paused and held up his hand as a warning to Gibo, who followed just behind him.

"There is something that moves," he whispered. "From the color of its skin it seems to be a tapir. We shall yet have meat for dinner."

The bow twanged as the arrow winged from it.

Bomba was startled by a shrill, almost human scream. This was not the grunt of a wounded tapir!

He darted toward the spot where something lay inert upon the ground, and Bomba, to his consternation, saw that he had shot, not a tapir, but a monkey, one of the great apes whose unconcealed hostility had given them such uneasiness.

There was the sound as of a great wind sweeping through the trees, the rumble of many angry and threatening voices. Vengeance was brewing for the slayer.

As the monkey tribe came surging through the branches, Gibo caught the lad's arm.

"Quick!" he exclaimed. "Gibo will show Bomba the one way of escape."

Bomba did not stop to argue. He knew what swift vengeance the monkeys, when in numbers, meted out to the slayer of one of their tribe.

If they reached him, they would tear him limb from limb. His bow and arrow, his machete, his revolver would be useless against such an onslaught.

So he followed Gibo, fleeing before the wrath of the great apes.

The native pushed aside some branches and disclosed a dark hole.

"Quick!" he panted. "The jaguar, the puma, the cooanaradi may dwell here, but this is the one chance of Bomba and Gibo for life. Let Bomba enter and Gibo will follow."

Bomba plunged into the opening and like a flash Gibo followed, carefully rearranging the bushes over the opening.

"If they have not seen us, we are safe," gasped Gibo.

"Let us go further within the cave, Gibo," counseled Bomba. "That will give Bomba room to use his bow and arrows if the apes come in. And then it may be that this cave has another opening in some other part of the jungle. Come!"

The chattering of the angry monkeys came toward them like the onrushing waters of a tidal wave. As Bomba and Gibo felt their way along the damp sides of the cavern, they expected at almost every moment to hear the thudding footsteps of their pursuers close behind them.

The wave of sound came nearer, reaching the very entrance of their hiding place, then broke in an angry flood over the cavern and surged off into the distance.

For a long time Bomba and Gibo stood still, listening.

At last the furious uproar died away and all that could be heard was the screaming of the parrots as they flaunted their gorgeous plumage in the branches of the trees.

"Bomba thinks the danger is over, Gibo," said the jungle lad. "The monkeys were confused and passed us by."

"They may come back," returned Gibo. "It is still not safe to venture out into the jungle."

"Did Gibo know this cave, that he came to it so straight when the monkeys became angry?" asked Bomba curiously.

"Gibo came this way once before," replied the native. "He found this refuge, Bomba, and so saved the life of Gibo from two hungry jaguars that stalked him through the jungle."

Bomba looked about him trying to pierce the blackness.

"It is dark within the cave, Gibo," he said. "We must find our way back to the hole's mouth and wait there till it is once more safe to go out into the light of the sun."

But when they would have followed Bomba's advice, they found that somewhere in their retreat into the recesses of the cave they had become involved in a maze of turnings.

"There are more passages that one," muttered Gibo, his fingers feeling along the dank, mossy sides of the cave. "We must have taken the wrong turning. Gibo knows not this portion of the cave, or whether it leads to good or to evil."

"Let us go on, then, Gibo," counseled Bomba. "The cave had a beginning. It must also have an end. Come, we will follow this passage till we find that for which we seek."

The cave was as dark, as the jungle night. From time to time Bomba struck a match that revealed for a moment their surroundings. But his stock of those precious commodities was growing dangerously low, and he did not dare to use too many of them.

It was perilous work, stumbling through the darkness, not knowing what grisly perils were concealed from them by that black curtain.

The jaguar and the puma made their homes in just such caves as this. It would be almost a miracle if the cave were found to be uninhabited.

For a long time the two groped and stumbled along, coming up at last against a blank wall that marked the end of the tunnel.

They were hungry as well as weary, and Bomba regretted the mistake he had made with growing bitterness.

"Bomba is a fool," he told the patient Gibo. "Never before has he mistaken a monkey for a tapir. His eyes must be growing dim and his brain weak."

"The eyes and brain of Bomba were not to blame," replied Gibo soothingly. "The foliage of the tree was thick. Gibo, too, thought it was a tapir until he saw the monkey lying on the ground."

"Bomba is sad," observed the jungle lad. "He would not hurt a monkey. Many of the monkeys are his friends."

"It would be well to forget and to give thanks to the gods that Bomba and Gibo did not fall before the wrath of the angry tribe," returned the native.

But it seemed for a time as though they had escaped one peril only to fall into a trap from which there was no escape. It appeared that there were many underground passages, but none they traversed led to an opening. They came to one that was new to them, and as it seemed to have fewer turnings than any of the others their hope revived that it might prove the main passage.

But as they followed this new lead hope gradually gave place to irritation, almost despair.

"This but leads us further underground, Gibo," said Bomba. "The air grows hot. Perhaps it is like the Moving Mountain that has fire in its heart to destroy all who enter."

Indeed the air grew more intolerable with every step they took.

"We must turn back, master," said Gibo at last, pausing to wipe the perspiration from his face. "Surely this leads into the heart of a mountain."

"Gibo speaks truth," returned Bomba. "We must go a different way unless we wish to leave our bones in this pit of death." But as Bomba turned to retrace his steps he was halted by a cry from Gibo. As he turned toward the Indian the cry grew to a terrified scream!

"HELP, Bomba, help!" came the cry. "Help or your servant dies!"

As Bomba plunged wildly forward in the direction of the shriek he heard a hideous, sibilant hissing.

Again and again the screams of Gibo rang through the stifling air of the tunnel, accompanied by the sounds of a terrible struggle.

No need now for Bomba to wonder what danger threatened his friend. Gibo was in the coils of the terror of the jungle, the wicked anaconda. Bomba knew that he must act quickly if he would prevent his faithful companion from being crushed to death.

He whipped his machete from his belt and plunged blindly to the rescue. It was a fearful risk to attack a serpent in the dark. But Bomba used his hands and ears in default of eyes.

He groped forward and felt beneath his fingers the loathsome coils of the great snake. It was wound about the native in a deadly embrace. Bomba knew that those coils, strong as steel, would tighten slowly, ruthlessly until the bones of the victim snapped beneath the pressure.

He could hear Gibo pant and struggle. His screams became feeble moans of terror, sobs of torment.

Bomba raised his arm and plunged the knife into the slimy coils. Again and again he slashed fiercely, but the steely coils still held. A few moments more of this and life would be crushed from Gibo, his good and loyal friend.

Bomba redoubled his efforts, fighting with superhuman fury. The snake was gashed in twenty places, the floor of the cave was slippery with blood.

Half-sobbing with rage, Bomba again drove his knife into the body of the snake. This time the keen edge severed the vertebral column.

There was a terrific thrashing about as the reptile writhed in the contortions of death.

Then something struck Bomba a stunning blow on the head and felled him to the ground.

When, from the gulf of unconsciousness, Bomba swam back to a knowledge of his surroundings, he was conscious chiefly of a terrible pounding in his head. The top of his skull ached throbbingly and he could scarcely breathe. He sensed quickly what had happened to him. |One of the heavy coils in the snake's last contortions had hit him a heavy, stunning blow.

Darkness was all about him, a blackness that pressed upon him like an actual weight. Slowly Bomba reassembled his scattered senses and took a grip on himself.

He raised himself on his elbow and peered about him.

"Gibo!" he cried faintly. "It is Bomba who calls. Where are you?"

There was no answer. Remembering the folds of the giant snake, wrapped like bands of iron about the body of Gibo, Bomba wondered whether life had left the Indian before the edge of his machete had cloven the anaconda's coils.

Struggling to a sitting posture, Bomba tried again to pierce the darkness.

"Gibo!" he cried with increasing anxiety. "If Gibo lives, let him come to Bomba."

There was the sound of padding footsteps in the tunnel behind him. The heart of Bomba quickened its beats. If this were Gibo, why did he not answer? If it were not Gibo, who or what then was this that approached through the blackness of the cavern?

A big cat, perhaps, that dwelt in the recesses of the cave. Or possibly another native, not friendly like Gibo, perhaps one of the henchmen of Japazy.

As Bomba indulged in these conjectures the soft footsteps came nearer. Bomba's grip tightened on the slippery hilt of the machete, which he Still held in his hand. He tried desperately to drag himself to his knees, but found that he had not the strength, and sank back against the wall of the tunnel, weak and panting.

"Bomba must fight sitting down," the lad said to himself grimly. "It may be a quick fight, soon over, but Bomba will die, if he has to, with his machete in his hand."

On came the footsteps until they were almost upon him. Bomba braced himself for a struggle.

"Back!" he cried fiercely. "Let him that comes take care that the sharp knife of Bomba find not its way to his heart."

The padding footsteps halted. There was a moment of silence and then came the voice of Gibo, joyful and clear through the darkness.

"The gods be praised who have led Gibo to his master!" cried the faithful native. "Gibo thought that he would never hear the voice of Bomba again."

The muscles of the jungle lad relaxed. Relief and joy weakened him, and he sank back against the tunnel wall, conscious once more of the throbbing pain in his head.

"Bomba is thankful that Gibo still lives," Bomba said faintly. "The coils of the great snake then did not crush out the life of Gibo, as Bomba feared?"

Gibo fell on his knees and groped his way to the spot where Bomba lay.

"Master," he said quickly, eagerly, "when the great snake unwound from my body, killed by the knife of Bomba, Gibo fell, struck his head and knew no more. When he came to himself he knew not where he was. He was like a man that has taken too much of the fermented juice of roots, beaten and prepared by the women. He staggered and went, not knowing where he was going, and he came to a sharp bend in the passage and he saw—light! Master, surely the gods of the jungle are with us, for Gibo saw light!"

Bomba gripped the arm of the native.

"Then Gibo found another mouth to the cavern?" he asked, scarcely daring to believe in his good fortune.

"With the help of the gods, Gibo saw the light of day," replied the native. "Come then, master, and your slave, Gibo, will lead you to the sunshine and fresh air of the open jungle."

The joyful news brought an access of strength to Bomba, and he found on making the effort that he could stand on his feet, though rather unsteadily.

"Lead on, Gibo," cried the lad jubilantly. "Bomba has his strength back, for hope has again come into his heart."

The dead body of the snake lay across the floor of the tunnel. They stumbled over the noisome coils and kicked them aside, coming at last to the sharp curve of the tunnel that Gibo had spoken of to Bomba.

Then the lad saw what quickened his pulse, a faint light in the distance, the blessed light of day that he had feared he would never see again.

Bomba tried to hasten his steps, but found that he still lacked his usual vigor and had to proceed slowly.

"What was it then that felled the mighty Bomba, who again has saved the life of his slave?" asked Gibo, when they had progressed for some distance along the steadily brightening tunnel.

"To Bomba it seemed that the roof of the cavern had fallen on his head," replied the lad. "But it was the thrashing body of the anaconda that dealt him a blow that might well have dashed out his brains."

"Ayah!" said Gibo solemnly. "The gods of the jungle are with us."

"Bomba is glad," answered the jungle boy briefly.

"The evil spirits led us into the cave and the lair of the great snake," Gibo averred. "The good spirits bring us again to the light. Behold!"

Bomba saw, and his heart sang with a great joy. They were at a mouth of the tunnel, and beyond, in the familiar jungle, monkeys chattered and parrots screamed in a discord that seemed to Bomba the sweetest music he had ever heard.