RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"The Square Egg," John Lane, the Bodley Head, London, 1924

"The Square Egg," John Lane, the Bodley Head, London, 1924

Thanks are due to the Editors of the Morning Post, the Westminster Gazette, and the Bystander for their courtesy in allowing tales that appeared in these journals to be reproduced in this volume.

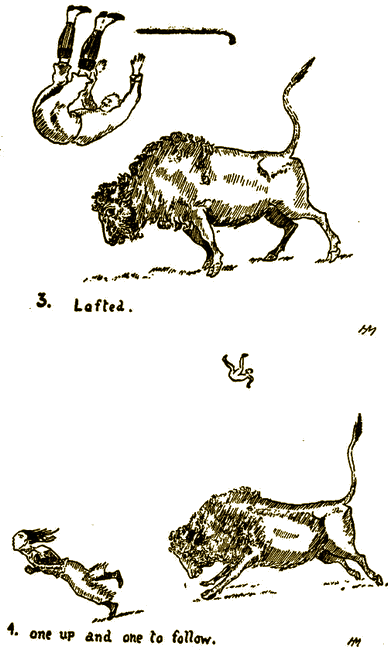

Saki's drawings, scattered through the biography, have, many of them, no connection with the text. They are given as samples of his whimsical humour.

E.M.M.

MY earliest recollection of Hector, my younger brother, was in the nursery at home, where, with my elder brother, Charlie, we had been left alone. Hector seized the long-handled hearth brush, plunged it into the fire, and chased Charlie and me round the table, shouting, "I'm God! I'm going to destroy the world!"

The "world" tore round and round the all-too-inadequate table, not daring to leave it to dash for the door, while Hector, his face lit with impish glee and the flare from the brush, enjoyed to the full his self-imposed divinity. Our yells brought Aunt Augusta on the scene, and we all got a dressing down.

The nursery looked on to a field, where appeared various farm animals that served as models for Hector's sketches—models that he kept in his head, for I never saw him drawing from life until years later.

Broadgate Villa, in the village of Pilton, near Barnstaple, North Devon, was the house my father took for us, after our mother's death, before leaving for India. Here his mother, and his two sisters, Charlotte and Augusta, were installed to look after us.

I think Hector must have been about two when we arrived there. He was born in Akyab, Burma, where my father was stationed, on December 18, 1870, and christened Hector Hugh. He was a delicate child, in fact the family doctor at Barnstaple, whom the grown-ups looked upon as an oracle, declared that the three of us would never live to grow up. Probably children not so highly-strung and excitable would have succumbed, because, judged by modern methods, our bringing up was quite wrong. The house was too dark, verandas kept much of the sunlight out, the flower and vegetable gardens were surrounded by high walls and a hedge, and on rainy days we were kept indoors.

Also fresh air was feared, especially in winter; we slept in rooms with windows shut and shuttered, with only the door open on to the landing to admit stale air. All hygienic ideas were to Aunt Augusta, the Autocrat, "choc rot," a word of her own invention.

Then we should have had more country walks than we ever got, there were lovely fields and woods quite handy, but Aunt Augusta wanted shops and gossip—also she was afraid of cows.

Fortunately, there were the three of us, and we lived a life of our own, in which the grown-ups had no part, and to which we admitted only animals and a favourite uncle, Wellesley, who stayed with us about once a year.

Our pleasures were of the very simplest—other children hardly came into our lives—once a year, at Christmas, we went to a children's party, where we were not allowed to eat any attractive, exciting-looking food, "for fear of consequences," and in case the party might have done us harm, Granny gave us hot brandy and water on our return.

Also, once a year, in the summer, the child of some friend visiting the neighbourhood would come to play with us. "So good a boy," we would be told, "he always does what he is bid."

From that moment a look of deep purpose settled on Hector's face, and on the day when the good Claud arrived an entirely busy and happy time for Hector was the result.

He saw to it that Claud did all the things we must never do, the easier to accomplish since his mother would be indoors tongue-wagging with Granny and the aunts. Poor Claud really was a good child, with no inclination to be anything else, but under Hector's ruthless tuition, backed up by Charlie, he put in a breathless day of bad deeds.

And when Aunt Tom (Charlotte she was never called), after the visitors' departure, remarked, "Claud is not the good child I imagined him to be," Hector felt it was the end of a perfect day.— But by ourselves we had not the scope for naughty deeds—it was, "Don't play on the grass," from one aunt, and "Children, you're not to play on the gravel" from the other.

The front garden, with its grass slopes under the elm-trees where the rooks lived, was the only outdoor place we had to play in, the kitchen garden being considered too tempting a place, with its fruit trees.

Therefore the boys had to get into it, by hook or by crook.

So much has been said, in reviews of Hector's books, about the cruelty element in them, an element which, personally, I cannot see, that an account of the aunts' characters may perhaps throw some light on the environment of his early years.

Our grandmother, a gentle, dignified old lady, was entirely overruled by her turbulent daughters, who hated each other with a ferocity and intensity worthy of a bigger cause. How it was they were not consumed by the strength of their feelings I don't know. I once asked a friend of the family what had started the antagonism.

"Jealousy," she said; "when your Aunt Tom, who was fifteen years older than Augusta, returned from a long visit to Scotland, where she had been much admired, and spoilt, and found the little sister growing up, also pretty and admired, she became intensely jealous of her—from that time they have always quarrelled."

Aunt Tom was the most extraordinary woman I have ever known—perhaps a reincarnation of Catherine of Russia. What she meant to know or do, that she did. She had no scruples, never saw when she was hurting people's feelings, was possessed of boundless energy and had not a day's real illness until she was seventy-six.

Her religious convictions would fit into any religion ever invented. She took us regularly to Pilton Church on Sunday mornings. For a long time I was struck by her familiarity with the Psalms, which she apparently repeated without looking at her book, but one day I discovered she was merely murmuring, without saying a word at all, and had put on her long-distance glasses in order to take good stock of the congregation and its clothes. A walk back after church with various neighbours provided material for a dramatic account to Granny (not that she was interested) of the doings of the neighbourhood. Whatever Aunt Tom did was dramatic, and whatever story she repeated, she embroidered. No use to try to get to the end before she intended you should. Without any sense of humour whatever, she was the funniest story-teller I've ever met. She was a colossal humbug, and never knew it.

The other Aunt, Augusta, is the one who, more or less, is depicted in "Sredni Vashtar" (" Chronicles of Clovis "). She was the autocrat of Broadgate—a woman of ungovernable temper, of fierce likes and dislikes, imperious, a moral coward, possessing no brains worth speaking of, and a primitive disposition. Naturally the last person who should have been in charge of children.

But the character of the aunt in "The Lumber Room" is Aunt Augusta to the life. "It was her habit, whenever one of the children fell from grace, to improvise something of a festival nature from which the offender would be rigorously debarred; if all the children sinned collectively they were suddenly informed of a circus in a neighbouring town, a circus of unrivalled merit and uncounted elephants, to which, but for their depravity, they would have been taken that very day.... She was a woman of few ideas, with immense powers of concentration.... Tea that evening was partaken of in a fearsome silence."

Well do I remember those "fearsome silences!" Nothing could be said, because it was certain to sound silly, in the vast gloom. With Aunt Tom alone we should have fared much better—she adored Hector as long as he kept off the flower-beds and out of the kitchen garden—but as we could not obey both aunts (I believe each gave us orders which she knew were contrary to those issued by the other), we found it better for ourselves, in the end, to obey Aunt Augusta.

Our best time was during some pitched battle in their internecine warfare, "with Aunt calling to Aunt like mastodons bellowing across primeval swamps;"* we lived our little lives, criticized our "elders and betters" and rejoiced exceedingly when Aunt Augusta went to bed for a whole day with a headache.

* P.G. Wodehouse.

This gave us more scope, and we became more venturesome—Hector always the most daring— even exploring the top story because it was forbidden ground, and contained a mysterious room, the original of "The Lumber Room" in "Beasts and Super Beasts."

Aunt Augusta's religion was not elastic; it was definite and High Church and took her into Barnstaple on Sunday evenings. Neither aunt permitted her religion to come between her and her ruling passion, which was, to outwit the other. What they squabbled about never seemed to be of much importance. If Aunt Tom came back from Barnstaple market bearing reports of poultry she had bought at 2s. 6d. Aunt Augusta would know no peace until she had seen a far fatter bird at 2s. 4d. and announced it.

Then a row began—more or less intense, according to the length of time that had elapsed since the last one. Fighting probably relieved their tremendous energy. They never swore, so we heard no bad words. One good effect the quarrelling certainly had on us—it looked so ugly, we never copied them— never in our lives have we three had a row.

The aunts' outside interests lay in politics and the gossip of Pilton. Gardening kept Aunt Tom more or less sane, and making yards of useless embroidery had a soothing influence on Aunt Augusta. From morning to night, whether the jobbing gardener were there or not, Aunt Tom would be busy and dirty. Both aunts were exceedingly loyal to their friends, who, in their eyes, could do no wrong, and very generous to the poor.

They did not care at all for animals, but luckily did not interfere with our pets, whom we adored— they were JhfiL. only young things we had to play

Hector had a curious dislike of rooks; I had a pet young one, and used to feed it with bread and milk; if he took the spoon he dropped it as it opened its beak. This dislike lasted all his life.

We had charming cats, who gave us all the affection the grown-ups did not know how to show. Tortoises, rabbits, doves, guinea-pigs and mice were other pets we had for a time, but cats and cocks and hens were always with us.

There was a most intelligent Houdan cock, who was Hector's shadow; he fed out of his hand and loved being petted. Unhappily he got something wrong with one leg, and had to be destroyed. I believe a "Vet." would have cured him, but this would have been considered a sinful extravagance. No one but myself knew what Hector felt at the loss of the bird. We had early learnt to hide our feelings—to show enthusiasm or emotion were sure to bring an amused smile to Aunt Augusta's face. It was a hateful smile, and I cannot imagine why it hurt, but it did; among ourselves we called it "the meaning smile."

Of course there were lots of days on which life went smoothly, but, with an autocrat like herself, the most unexpected little things would upset her.

Both aunts were guilty of mental cruelty: we often longed for revenge with an intensity I suspect we inherited from our Highland ancestry. The following episode has already appeared somewhere, years after it happened. I told it to a friend of Hector's, who said he should make it into a story.

We always had plenty of good food, but, of course, plain, and except on our birthdays we never got roast duck, of which we were very fond. Sometimes a friend coming from a distance would be asked to lunch, and then roast duck would be the chief dish. Before the guest arrived Aunt Augusta would tell the three of us that at lunch she should ask us which we would have—roast duck or cold beef, and we were to answer, "Cold beef, please."

Well, on one occasion there were a couple of ducks, which Aunt Augusta was carving, and cold beef, which Granny had before her. All the grownups had had their plates filled, and Aunt Augusta turned to us. Hector and I gave the dutiful replies, but Charlie, on her left, was evidently so overcome by the sight and smell of the birds that he replied, "Roast duck, please."

Aunt Augusta glowered at him.

"What did you say?" she asked, with furious eyes, and kicked him under the table.

"Oh, cold beef, please," said Charlie, hurriedly.

"What extraordinary children, to prefer cold beef to duck!" remarked the visitor, and the children did not enlighten her.

Charlie really came off worst—Aunt Augusta never liked him, and positively used to enjoy whipping him. Hector and I escaped whipping, being considered too delicate. Fortunately for Charlie, he went to school when he was eight, and so got away from her malign influence. In her queer way she was fond of Hector and me, but being such an unlovable character, we extended only a lukewarm sort of liking to her.

With the best will in the world we could not be really naughty, for there simply was not the scope.

Three children with three grown-ups to manage them are really handicapped from the outset.

Granny we were very fond of; she was always very gentle with us, but appallingly strict on Sunday. No toys, no books except Sunday books, Dr. Watts's ghastly catechism, a collect and piece of a hymn to be learnt and repeated to her, stories read to us from "Peep of Day," and church, of course, in the morning. But at church we saw people and other children.

In the afternoons we had a church service among ourselves, the grown-ups must have been sleeping the Sabbath sleep. Preaching was the favourite part of the game and was a solemn affair, listened to with deep attention, far deeper than the preacher in church ever got, but there had to be three sermons in rapid succession—we all had something to say.

It also, in summer, was the favourite day for the boys to attempt, generally successfully, to get into the kitchen garden. Not every afternoon did the aunts sleep, so either that or to make a marauding expedition into the store-room via the greenhouse, and equally forbidden ground, was naturally the only thing to be done.

On one occasion they emerged from the latter with a jar of tamarinds, and got it safely into the night nursery where there was a large trunk in which Aunt Augusta kept spare clothes. They ate what they wanted and put the jar in the trunk between folds of a black silk dress. The jar contained a lot of juice, very sticky, and in the eating much was smeared over the sides. However, the black silk absorbed a lot.

And then Aunt Augusta had occasion to open that trunk!

Broadgate resounded to her bellowings, and the row was frightful. In a former life she must have been a dragon. No toys allowed for two days, disgrace for all of us, and, of course, nothing to do. But mercifully we had fertile brains, and Hector was never nonplussed for occupation. Aunt Tom sometimes read to us—"Robinson Crusoe," "Masterman Ready," and the two "Alice's," which we loved, "Sandford and Merton" we refused to listen to.

"Johnnykin and the Goblins," a very little-known book, had always fascinated Hector. Being a Celt, I suppose it was natural he should be fond of goblins and nature spirits—he was certainly a Puck himself to the end of his life.

Pilton was a sort of Cranford; there were about ten families, most of them without children, so we got to know grown-ups well and to be quite at ease in their society. When we did see children, it was in a crowd at a Christmas party. Aunt Augusta always went with us, and sometimes left us with the other children while she departed to gossip with the grown-ups. Hector leapt at the opportunity and the nearest boy, and was soon in the ecstasies of a fight.

Then Aunt Augusta would look in and in a restrained fury drag him off to be tidied. But his blood was up and any threat as to subsequent punishment was ignored. It was not that he was pugnacious—he was a very sweet-tempered child, but his high spirits had to have some outlet, and life at Broadgate was very monotonous. At the same party he had to be restrained from dashing on to the stage to rescue a man who was being threatened by another.

At this time he was an extremely fair child—very pink and white skin, blue-grey eyes with long black lashes, and flaxen hair. In his teens he began to get darker. Those who only knew him in his London days cannot understand that he could ever have been fair.

From about seven years old he was a keen politician. There was a most exciting election in Barnstaple, when Lord Portsmouth's son, a Radical, was elected. We were taken to the town to hear the poll declared, and had seats in a window opposite "The Golden Lion." The sights we saw were far too thrilling, and Hector was in a fever of excitement and furious at the result of the poll. He remained Conservative all his life.

He showed no signs of a writing talent as a boy with the exception of contributions to "The Broad-gate Paper" which we ran. Drawing animals was his favourite occupation; he never copied—just drew things out of his head. One rainy day in the holidays we had nothing to do, so we settled to have a Picture Exhibition that afternoon. Hector would be about eight then. We set to work to paint the pictures, of which many were still wet at the time the show opened. The grown-ups knew what we had planned, yet they never troubled to attend and praise our efforts, so we had to be audience and judges as well. With great solemnity and perfect justice Hector's pictures were awarded the prize, an old copy I had of Aesop's Fables.

Once in four years my father came home on leave {he was then a major in the Bengal Staff Corps, and Inspector-General of the Burma Police), and for six weeks we had a glorious time.

He took us for picnics, and to the houses of friends who had farmyards, where Hector rode the pigs, climbed haystacks with Charlie and arrived home rakish and buttonless, but in unquenchable spirits, snapping his fingers (figuratively, of course) at Aunt Augusta.

We did not fear her when Papa was about. The wonder was we did not fear God with every inducement to do so. It was patent that our characters wse I take the trouble to amuse them."

Hector began lessons with a daily governess we had; our history lessons were read aloud, each taking a page. All went well until we reached Cromwell's time.

"You must take the Roundheads' part," he said to me.

"But I would rather be Royalist," I objected.

"We can't both be Royalists, so you must be Roundhead."

(The odd thing is that, from being forced into it, I have remained Roundhead ever since.) So we began the period of the Civil Wars with great delight —it soon became exciting—Hector would gloat over a victory of his side, even rising up in his chair to hurl abuse at the Roundheads, which naturally I wouldn't stand, so I abused back; the governess, being aere fatally attractive to Him, and when we went a bit too far we were told that He sent a thunderstorm as a warning that we had better be careful.

I think Aunt Augusta must have mesmerized us —the look in her dark eyes, added to the fury in her voice, and the uncertainty as to the punishment, used to make me shiver. She had the strange characteristic of being unable to be just annoyed at anything, she had to be so angry that she would work herself into a passion. After all, we fared better than a splendid retriever she had, who was kept chained up in an outhouse of the back-yard for years, with nothing to look at, eating his heart out. He was taken out for a walk perhaps twice in the year (until my father came home) and frightened Aunt Augusta with his obstreperous delight. He died of tumours when he was about eight.

Uncle Wellesley, our only civilian uncle, was a great favourite with us. He only came about once a year, and took Hector on fishing and sketching expeditions. We never had a dull moment when he was home; in a letter I found lately, written to his mother, he said àpropos of Aunt Augusta's complaint of our behaviour), "the children are never naughty with me, becau fool, at last stopped the concerted history lesson, but she couldn't stop us; we only waited until she was off, got down the histories and took the battles at a gallop, going through all the gamut of emotions from depression to exultation, according to the fortune of war. History then and ever afterwards became his favourite study, and as he had a wonderful memory his knowledge of European history from its beginning was remarkable. He was also very keen on natural history. When he was about nine he had brain-fever: the aunts nursed him most carefully; we had only to be ill, and everything was changed at Broadgate, scoldings were things of the past. This illness delayed his going to school. We went much too seldom to visit my mother's people in Kent. They were much more our sort than the home aunts. My grandfather, Rear-Admiral Mercer, was full of fun, and his daughters were young and lively, and they let us do lots of things we could never do at home. Grandpapa was very fond of practical jokes, which fondness his grandchildren inherited in full measure.

Two or three London visits, and, very seldom, two weeks by the sea, completed our outings.

Hector was rather a favourite with old ladies, with whom he made himself quite at home. Aunt Tom took us once to see a very charming old lady, whose daughter (not a chicken) was then away on a round of visits. In a pause in the conversation Hector approached our hostess and, in a most courtly manner, proceeded:

"And so I hear, Mrs. Simpson, that Miss Janet is away in Scotland, enjoying all kinds of debauchery."

There was an astonished pause, everyone laughed, and Aunt Tom exclaimed:

"That dreadful Roman history! That's where he picks up these extraordinary expressions!"

It was quite true—we had a remarkable, unexpurgated history with novel and lengthy words which needed airing, and this seemed to be a good occasion to have one out.

My father chose a resident governess for me before his last departure for Burma; she was to teach Hector as well until he was strong enough for school (he was then twelve). It would be a great change for us to have a new-comer in the house, and we gravely discussed the situation.

"After all," said Hector, we have only the grown-ups' word for it that she is a real governess, but how are we to know? We must put a pea under her mattress, and see how she sleeps."

In one of Hans Andersen's tales, an unknown Princess was admitted on a wild night into a royal castle and given a bed consisting of twenty mattresses and twenty feather beds, after the Queen had thoughtfully put a pea under the lot. If she slept well, she was an impostor, if badly, that proved her royalty. She slept atrociously.

So before the pseudo-governess arrived we put a dried pea under her mattress, and next morning asked her anxiously how she had slept.

"Very well indeed, thank you," she replied, with a pleased surprise at our solicitude.

"Ah, then, you can't be a real governess," said Hector, greatly disappointed, and told her what we had done.

She was, however, a real companion, and took us for the walks we loved and explored the whole country-side. She, like Uncle Wellesley, never found us naughty, because she took the trouble to amuse us. However, Aunt Augusta was afraid of her; we did not know it at the time, but she thought Miss J's dark eyes were trying to mesmerize her, so, on the day she left for the holidays, after only one term with us, Aunt Augusta, who had not the nerve to do it herself, got Granny, who was then dying, to dismiss her. The following term we had no governess; Granny died, and we had a very sad time.

Another governess arrived for the next term, chosen by Aunt Augusta, and Hector soon after that was considered strong enough to go to school.

He went to Exmouth, where Charlie had preceded him, and was very happy there.

It was on returning to school after the holidays that Aunt Augusta gave a sample of mental cruelty. Some petty naughtiness had angered her the day before his return to school, so she sent him back without any pocket-money. As each boy had to bank his allowance for the whole term with one of the masters, Hector's ordeal may be imagined when he had to confess he had none.

Charlie, who had not yet returned to Charterhouse, and I planned what we could do to help Hector. We settled to sell our books—Christmas and birthday presents from friends of the family. So we did, secretly, to a second-hand bookseller for quite a nice sum, and sent a postal order to Hector. Charlie then wrote to Papa, telling him what we had done, and the latter's letter to Aunt Augusta, blaming her for her action, was the first news she had of the affair. There was a row.

At fifteen, Hector went to Bedford Grammar School and was there for two years. His school reports used to be, "Plenty of ability, but little application." In his Easter holidays he went bird-nesting, with some of our neighbours, and made the beginning of a collection which he added to in our Heanton days. This collection is now in the Bideford Museum.

Two bears came forth from their cubless den—

Their cubless den, for their cubs were robbed—

And hunted about in search of men

Till they came to the spot where the Prophet was

mobbed.

For men must hunt, tho' bears will fret,

And a cub will command a good price as a pet

And money is always consoling.

Thirty-two corpses lay stretched on the sward,

Thirty-two corpses, or possibly more,

For the bears were too busy their bag to record

And the Saint didn't stay to attend to the score.

My father, who had now retired, took us both to Normandy, our first trip abroad. We had some amusing young playmates, French and Russian, and enjoyed to the hilt the novelty and fascination of life at Etretat, with no aunts to mar our delight: the bathing would certainly have shocked them.

Our second trip abroad was a more educational one, to Germany. We had a lengthy stay in Dresden, Charlie joining us, and my father first began to feel what it was like to look after strictly brought up children! Although Hector was then eighteen, he was still a boy, with no intention of growing up. One effect of the strict Broadgate régime was that he developed late—he remained and looked a boy long after he was in the twenties. We stayed in a Dresden pension run by a German lady, where the other guests were Americans.

On the flat beneath us was a girls' school, all of them ugly. One day, when my father was out, the boys made a weird figure of his bathing costume, stuffed out with paper and clothes, with a sponge for a face, and a rakish-looking hat. This they lowered into the balcony below. The schoolmistress happened to be giving dinner to a pastor, and to them, instead of to the girls, was vouchsafed this appalling vision.

When the boys thought enough time had elapsed, they swiftly drew up the figure. Swiftly, also, a note of complaint arrived for our landlady, who, being a German, saw no fun in the affair, not even with the figure sprawling at her feet. It was the convulsive laughter of a hitherto rather unbending American woman (in fact, the only time we ever knew her to laugh) that thawed her, and a note of apology was sent —insincere, as the school ma'am must have guessed, from the shouts of laughter above.

A "Lohengrin" night at the opera resulted in a sketch in which Hector depicted Lohengrin suffering from sea-sickness, while the swan turns round and gazes at him in astonishment. A German who saw it begged him to send it to the "Fliegende Blatter," but he never bothered to do it. He took long walks by himself in the parks to observe bird-life, and would stop Germans and draw in the gravel path the sort of bird he wanted, and ask if it were to be found. They would then write the bird's name in the gravel, and tell him where to get further information.

He routed out, in some obscure corner, an old man who sold birds' eggs, and from him bought a model of the Great Auk's egg, and insisted on coming home in a cab, for the greater safety of the egg.

Charlie left us to go to a crammer's (he was trying for the Army), and we then began a strenuous tour, beginning with Berlin. At the Palace of Sans Souci at Potsdam we searched for the graves of Frederick the Great's chargers and favourite dogs, and refused to go over the Palace until a park keeper could be found who knew where they were buried.

We saw an immense number of picture galleries in Berlin, Munich, etc., and were impressed by the love of German artists for St. Sebastian (the arrow-stuck saint), so we started bets on the gallery which would have the most: Berlin won.

Nuremberg delighted Hector—then and always he loved old towns; in later days Pskoff more than fulfilled his dream of what a mediaeval town should be. Prague was another delight, particularly Wallenstein's castle, where I had to engage our guide in talk while Hector cut a hair from the tail of Wallenstein's charger. In one room high up, formerly a council chamber, we were shown the window from which obstreperous councillors were thrown; we leant out while my father hung on to us, to see the depth they had to fall. This is the one described in "Karl-Ludwig's Window," in this book.

It was on our way to Prague that we saw snowcapped mountains for the first time, a never-to-be-forgotten experience. Any Celt will know the sort of awesome thrill one gets.

Fortunately, Innsbruck was the last place on our tour, for we were fagged out, and on arriving at Davos, where we were to spend several months, we lay low for a week, drank much milk and took stock of our fellow-guests at the H6tel Belvedere.

And then we let ourselves go!

My father was soon nicknamed "the Hen that hatched out ducklings," and some middle-aged, self-sacrificing men tried to be extra fathers to us, but it was no use. Swiss air and freedom went to our heads—nothing but an avalanche would have stopped us.

Tennis, paper-chases, riding, dancing, climbing, searching for marmots on the high reaches, occupied our bodies, and lectures on all manner of learned subjects and painting lessons kept our brains busy. Professor Meyer, a painter of birds of prey, was a teacher after our own hearts. He understood that we had to play some wild game before settling down to work. Usually we got to his flat before he was ready for us, and crept into his bedroom; presently a search began, and before he knew where he was he found himself in the midst of a pillow-fight—that or a wild scrimmage round the studio, and then we settled down, first eating some excellent cakes he fetched hot from the kitchen.

Hector learnt pastel from him, and did a very good picture of an eagle, life-size, bringing a seagull to her young ones.

John Addington Symonds had a house at Davos; he and Hector played chess together, and found they had a taste for heraldry in common.

The winter was even more fascinating than the summer—we were tobogganing all day, sometimes at night as well, and "tailed" behind sleighs to far-off runs, picnicking in the sun and snow. Charlie and Uncle Wellesley came out, and the bigger indoor entertainments began, fancy dress and domino balls, sheet and pillow-case dances, theatricals, etc. No better "coming-out" could any young thing desire, it was certainly the happiest winter we three had ever spent. Davos in those days was a friendly, jolly place, not at all fashionable.

We left it in April and went to stay at Schloss Salenstein, on the Swiss side of Lake Constance, the home of some very charming people whom we met at Davos.

Then to England, where we took a house, absurdly large for us, at Heanton, four miles from Barnstaple, also four miles from the aunts. Occasionally they came to visit us, one at a time, but were not encouraged to stay long. On the whole we were far too kind to them—so much water had flowed under the bridge since Broadgate days, and we were now topdogs and they knew it. Moreover, they had mellowed a bit, and Aunt Tom especially was devoted to Hector. She was such an original character we had to forgive her much, simply because of her unusualness. We were certainly blessed in our near relatives in one respect, we had not one who could be called dull!

Charlie, having failed, unfortunately, for the Army, being the only one of us with bad sight, left for the Burma Police. At Heanton we had for the first time a dog of our own, a fox terrior, who accompanied Hector on all his explorings. Toby, our cat, we brought from Broadgate, 'she was delighted to have us back, also to find so many hares in the field at the bottom of the garden, but unhappily through them she met her death from some beast of a keeper; her kitten had the same fate, and we were too sad to have another cat.

It was while roaming the country-side that Hector got to know the Devon character so well. The incidents in "The Blood-Feud of Toad-Water" really happened; our rector knew the people. There was also a witch in our neighbourhood who had uncanny powers, but we never met her.

For two years we lived at Heanton, studying under my father's direction, then left it for a season in town. Then back to Davos for the winter.

We had no more painting lessons there; our old friend had died the year before. We soon got together a "Push," of which Hector was the leading spirit, and on one or two occasions we literally painted the place red and blue with Aspinall's enamel.

There was a very pious hotel, the Hôtel des Iles, which received Hector's most artistic efforts. Six of us one night kept guard while he painted devils in every stage of intoxication on its pure walls.

The theatricals were on a more ambitious scale than two years previously. Hector took the part of the old lawyer in "Two Roses;" I heard an old colonel say he had created the part.

We had curling for the first time that winter, a game my father and Hector played a great deal, and some exciting toboggan races. But the event that set the seal on our activities was the gorgeous hoax we played on the Hôtel des Iles. It had committed the unforgivable crime in Hector's eyes of being mean.

The four English hotels at Davos (the Hôtel des Iles was one) at the beginning of the winter season elected each an Amusement Committee, which provided the various entertainments, dances, etc., for the season, sending round the hat for the funds, and it was the custom for each hotel to invite the guests of the others to the weekly dances, concerts, etc.

The Hôtel des Iles was the only one that invited no one to anything—the fault, of course, of the guests, not of the proprietor. They collected the money and—spent it on a dinner to themselves!

This, naturally, we could not stand, so the "Push," at the end of the winter season, decided they should give an entertainment that would be talked about. Hector, whose writing was not known there, wrote the invitations.

"The Hôtel des Iles requests the pleasure of the company of the Hôtel Belvedere's visitors on 20th March.

"'Box and Cox.'

"LE PETIT HOTEL."

This last, we heard, was an improper play, and was chosen to attract the foreigners.

These invitations were sent to the English hotels and to some of the visitors at the Kurhaus. We picked out Russian princes, German barons, Italian counts, etc., and we left out the distant chalets, so that no one should be put to any expense in hiring sleighs. I wanted to stay and see the fun, but Hector said he had not the nerve to look inno-cent. The replies, we stated on the invitations, should be sent to two men who, we knew, had left the Hôtel des Iles, and naturally were forwarded on to them.

As the Hôtel des Iles people were so unco' guid and kept so much to themselves, they did not mix in the life of Davos and so knew nothing of the excitement their invitation caused.

A Scottish girl, one of our "Push," sent us a thrilling account of the evening. The English hotels were warned in time, not so the people at the Kurhaus, who arrived in strength.

Then there was pandemonium, and a babel of imprecations assailed the chaste ears of the innocent inmates. "I know who did it," shouted an irascible man, and rushing home for a horsewhip he hurled himself into the room of a guiltless American. I mean he was not one of the "Push." Fortunately explanations were satisfactory, and no one was whipped. I believe the authorship of the hoax was never guessed. We heard long afterwards a rumour that early next winter the Hôtel des Iles gave a concert to which everybody was invited and no one turned up!

We went to stay with Aunt Tom at Pilton, that spring of 1893, and in June Hector left for a post my father had got for him in Burma, in the Military Police.

Charlie met him on arrival and they both stopped in Rangoon with the Deputy Inspector-General of Police.

Hector was in Burma only thirteen months and had seven fevers in the time. He got a lot of enjoyment from the animal life surrounding him—to be on a horse was one great delight, and to be at close quarters with wild animals was another.

He also, as his letters show, appreciated the good qualities and resourcefulness of the Burmese servants; whether other masters have found them so all-round useful I do not know, but Hector had the gift of attracting willing service wherever he was. The Burman is fond of animals, particularly little animals, and saw nothing extraordinary in a tiger-cat as a pet. I have quoted, in the following letters, almost exclusively the bits dealing with animals, because they are the most characteristic of him.

Singu, June 5th, —93.

My Dear E.

The heat during the last few days has been scorching, and I have been quite knocked off my legs in consequence.... This is a dreadfully noisy place when one is not feeling well; there are the children: the little brats have a remarkably good time of it, they are never whacked or scolded, and they take a deliberate pleasure in howling at the slightest opportunity; you never heard such yells, they throw all their little heathen souls—if they have any—into the performance.

I should like to spank them for ever, stopping, of course, for meal times.... Then during the night, the frogs and owls and lizards have necessarily lots to say to each other, and whenever my pony hears another neigh she whinnies back, and being a mare always insists on having the last word. As to the dogs they go on at intervals during the twenty-four hours, like the Cherubim which rest not day or night. Have you ever seen a dog bark and yawn at the same time? I did the other day and nearly had a fit; it reminded me of a person saying the responses in church. The most welcome noise of all is the whistle of the steamboat, especially when it brings the English mail. ... I am agreeably surprised with my servants, they are quick, resourceful, seem honest, and are genuinely attached to their master's interests; of course they are more or less stupid, they are human beings.... I had quite a nursery establishment last week; I found a little house-squirrel which had just left its nest, on my verandah; it is like a large dormouse, silver grey with a mauve grey tail, and orange buff underneath; it lives upon milk and is very tame and snoomified.... Then there was a duckling; I thought of putting it with the squirrel, but the latter looks upon everything as meant to be eaten, and the duck had broad views on the same subject, so I thought they had better live in single blessedness. As the squirrel occupied the only empty biscuit tin the duck had to go into the waste-paper-basket where it was quite happy.

Singu, 17.6.93.

I am rather excited over a pony I have unearthed with zebra markings on its legs; Darwin believed that the horse, ass, zebra, quagga and hemonius were all evolved from an equine animal striped like the zebra but differently constructed, and in his book on the descent of domestic animals he attached great importance to some zebra-like markings which he observed on an Exmoor pony; so my discovery may be of some interest.... This is a disappointing place as far as the flora is concerned; I have not seen any decent flowers or shrubs, except a kind of magnolia which is common here....

Aunt Tom's first letter was full of her grievances— so interesting to read; really if Providence persecuted me in the way it does her, I should be too proud to go to Heaven. Her complaint of loneliness amused me. If she is lonely in a place with 13,000 inhabitants it's her own fault. My boy continues to give satisfaction in regard to cooking, the way he serves chicken up as beefsteak borders on the supernatural.

I amuse myself by painting, when the midges are not too troublesome. I am doing a picture of the coronation of Albert II, Archduke of Austria, in 1437; not a proper picture but a sort of heraldic procession like you would see in old tapestries. The arch-bishop of Treves looks very smart on a fiery bay; I shall never forget the trouble I had to find his arms at the Brit. Museum.

Mwéhintha Outpost, 26.7.93.

I meant to have written to you last mail, but Mr. Carey arrived by the boat and paid me a long visit—it was a relief to have someone human to talk to—and I had to get ready for going out in the district; you see I have taken to district visiting in my old age. The place is so inundated that no pony can get out so I had to go by boat.... The Maid of Sker is charmed with her new quarters, she sees so much more life than formerly, and instead of having to thump on the earth floor when she wants anything, she can now rap her fore hoofs against the wooden partitions, which makes fifty times as much noise and ensures a prompt attendance....

There are most charming birds here now the rains are on, egrets, bitterns, pelicans, storks, pond-herons, etc. Shwepyi (the 1st guard on my route) is a great stronghold of these birds, as in the dry weather there are 2 large lakes there and in the rains it is all one big swamp; so when I arrived there last night I determined to make a hurried excursion next morning before leaving for this place. Accordingly I went forth this morning in a small sort of canoe with my boy and two men to row. We saw lots of pelicans and other birds but no nests, as most of them don't breed till August. As we were getting back, a Malay spotted dove flew up from a nest in a tree, which hung just over us. I sent one man up to get the eggs but he could not get at it, so I gave it a prod with an oar.

There was a yell from the men and as I stood back I saw an enormous snake rise "long and slowly" from the nest and glide into the branches. The man in the tree came down with the agility of three apes. It was a monster snake and looked very venomous.... As we were coming here in the big boat we passed a tree on which were several nests with darters sitting on them (the darter is a sort of cross between a gannet and a cormorant) a frightful tree to climb, but one of the natives ran up it like a cat and brought me down a lot of eggs and some young birds for them (the natives) to eat; fancy eating unfledged cormorants—oo-ah! When I got here I found the stockade was ankle deep in water; I had to be dragged up to the guard house in a small boat, which had to be carefully led round various shallows; it was like the swan scene in Lohengrin.

Owl and oaf thou art, not to see "Woman of No Importance" and "Second Mrs. T." The plays of the season; what would I not give to be able to see them!

25 Aug. 93.

For the last three days I have been at this place (can't remember the name, but it's six miles from Mandalay) where a high festival is being held in honour of two local deities of great repute, called the Nats. Their history is briefly this: they were two brothers who were ordered by the king to build a temple here, which they did, but omitted two bricks, for which reason the king killed them, in the impulsive way these Eastern monarchs have. After they were dead they seemed to think they had gone rather cheap and they made themselves so unpleasant about it that the king gave them permission to become deities, and built them a temple, and here they are, don't you know. Just that. The original temple with the vacant places for the missing bricks is still here; this is not an orthodox Buddhist belief but the Nats are held in great esteem in Upper Burma and parts of China, and this show is held here every year in their honour. The whole thing is so new to me that I will describe it at some length. Of course I had to come here as the presence of a European officer is necessary to keep order, and twenty-five police had to be drafted here. No martyr ever suffered so much on account of religion as I have. When I arrived the Nats were being escorted to the river to bathe, accompanied by unearthly music which sent the pony I was riding spinning round like a weather-cock in a whirlwind. Then I came to where the chief show is held and to my horror I found a solitary chair had been placed on an elevated platform for my especial use, to which I was conducted with great ceremony; I am not sure the orchestra did not try to strike up the National Anthem. I inquired wildly for Carey, but was told he was with his wife somewhere. I was in terror lest they might expect a speech, and how could I get up and tell this people, replete with the learning of centuries of Eastern civilization, "this animal will eat rice"? Fortunately the sparring commenced at once and was very absorbing to watch; two men fight with hands and legs and go for each other like cats, the one who draws blood first wins. I was quite disappointed to see them stop as soon as one was scratched. I had hoped (such is our fallen nature) that they would fight to the death and was trying hurriedly to remember whether you turned your thumbs up or down for mercy. Some of the encounters were very exciting, but I had to preserve a calm dignity befitting the representative of Great Britain and Ireland, besides which my chair was in rather a risky position and required careful sitting. Noblesse oblige. Then Carey came and told me that he had got quarters in the monastery grounds... and had got me a house adjoining the show-place. Not only does it adjoin the building, but it forms part of it and opens on to the arena! The hours of performance are from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., and from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. There are two bands. During performances my dining-room is a sort of dress-circle, so I have to get my meals when I can. As to sleep, it's not kept on the premises, while the heat is so great that you could boil an egg on an iceberg. There are also smells. The acting is not up to much but the audience are evidently charmed with it. I go to bed at ten, finding two hours quite enough, but when I get up at 5.30 the audience are applauding as vigorously as ever. Then I am worried to death by princesses; some of the native magistrates' wives are relatives of the ex-king and fancy themselves accordingly. One old lady, who carries enough jewels for twenty ordinary princesses, takes an annoying interest in me and is always pressing me to partake of various fruits at all hours of the day. She asked me, through Mrs. Carey, how old I was, and then told me I was too tall for my age, obligingly showing me the height I ought to be. It reminded me of another royal lady's dictum "All persons above a mile high to leave the Court." I told her that in this damp climate one must allow something for shrinkage, and she did not press the matter.

It is no sinecure to keep order with this huge mob of mixed nationalities, and I shall be glad when it is all over.

Singu, 6 Sept. 93.

... I found the tiger-kitten quite wild; pretended it had never seen me before, so I had to go through the ceremony of introduction again. I soon made it tame again, and we have great games together. It has not learnt how to drink properly yet and immerses its nose in the milk, then it gets mad with the saucer and shakes it, which sends the milk all over its paws, upon which it swears horribly. I have another queer creature in the shape of a young darter (same species of bird as the self-hatching one) which I saw sitting on the river bank en route for here; the men rowed to shore and just picked it up and put it in the boat where it sat as if it didn't care a twopenny damn. What blasé birds those darters are. Then there is the crow-brought chicken which was carried here by a crow and rescued by the syce; crows often run off with one's chickens but it is not often they add to your poultry. I feel quite like the prophet Elijah (or was it Elisha?) who was boarded by ravens. Milk is scarce now, but the kitten has to have some of my scanty store, while the ponies feel very annoyed if they don't get a bit of bread now and then; I believe I am rather expected to share my sardines with the darter, but I draw the line there! The Burmans have not collected any eggs for me yet; my boy says the birds are "too much upstairs living." Frightfully thrilling!...

The kitten throws off the cat and assumes the tiger when it is fed; I have to throw it its food (generally the head of a chicken) and then bolt; it is making the day hideous with its growling now, as I gave it the head and wing, and it is trying to eat both at once.

Madaya, 15.9.93.

A day or two before I left (headquarters) I was enjoying my midday tub, when my boy came and announced that a big bear had been caught and was being brought up to me; I implored him not to do anything so rash but he went away saying u Master bringing, yes." The bathroom is comparatively small and I knew that if a large bear were introduced there would be unpleasantness. I hastily forgave my enemies and tried to say my prayers, but the only one I could remember was the prayer for fine weather. As it happened my boy meant bird when he said bear, having caught a large sort of buzzard which naturalists have dignified with the name of hawk-eagle; so I left off praying for fine weather and un-forgave my enemies forthwith. The bird has fine plumage but a very sinister expression ; when I go near it, it opens its mouth, elevates its crest and glares at me with baleful eyes.

Ohnmin, 17.9.93.

I left Madaya yesterday.... My new pony I have called "Microbe" on account of his diminutive size. Poor little neglected beast, he looked on so modestly and wistfully when the mare was being given her corn and he was so charmed and thankful when he found he was going to have some too; and when he had a plantain brought him for dessert he began to think with "Mrs. Erlynne" that the world was "an intensely amusing place." ... At Yenetha my bullock cart had to be stopped, as two bears were walking along the path in front; I was on ahead, so missed seeing them. It is ever thus.... The "Mandalay Herald" had an article on the Toungbein Pwé, in which it said, "Many Europeans graced the proceedings with their presence, but the one who was most generally noticed and admired was a police-officer in full khaki uniform." This is rather rough on me, as I was the only European in uniform there.

Hôtel de France,

Mandalay,

24 Oct. 93.

... The tiger-kitten has had a nice cage made for it, with an upstair apartment to sleep in, but every afternoon it comes out into my room for an hour or two and has fine romps. It would make a nice pet for you but it would be an awful trouble sending it—it might die—and it won't be safe when it grows up. It goes into lovely tiger attitudes, when it thinks I'm looking.

... Tell Mrs. Byrne there is no immediate danger of my marrying a Burmese wife; there was a woman at Singu—ugly as a Fury—who, I think, had great hopes, but my boy, always ready to save me trouble, married her himself; he had one wife already, but that was a trifle. I impress upon him that he may have as many as he likes, within reasonable limits, but no babies. To this rule there is no exception. When I was out in the district if a child howled in any neighbouring hut men were sent at once to stop it; if it wouldn't stop it was conducted out of ear-shot; wouldn't you like to do that with English brats! How rabid the mothers would get!

Hôtel de France,

Mandalay,

30 Oct. 93.

... An old lady came to the hotel last week, one of those people with a tongue and a settled conviction that they can manage everybody's affairs. She had the room next to mine—connected by a door—and I was rather astonished when the proprietor came that evening, and with great nervousness, said that there was an old lady in the next room and er—she was rather er—fidgety old lady and er—er—er—there was a door connecting our rooms.

I was quite mystified as to what he was driving at but I answered languidly that the door was locked on my side and there was a box against it, so she could not possibly break in. The proprietor collapsed and retired in confusion; I afterwards remembered that the "cub" had spent a large portion of the afternoon pretending that this door was a besieged city, and it was a battering ram. And it does throw such vigour into its play. I met the old lady at dinner and was greeted with an icy stare which was refreshing in such a climate. That night the kitten broke out in a new direction; as soon as I went up to bed it began to roar; "and still the wonder grew, so small a throat could give so large a mew." The more I tried to comfort it the more inconsolable it grew. The situation was awful—in my room a noise like the lion-house at 4 p.m., while on the other side of the door rose the beautiful Litany of the Church of England. Then I heard the rapid turning of leaves, she was evidently searching for Daniel to gain strength from the perusal of the lion's den story; only she couldn't find Daniel so fell back upon the Psalms of David. As for me, I fled, and sent my boy to take the cage down to the stable. When I came back I heard words in the next room that never came out of the Psalms; words such as no old lady ought to use; but then it is annoying to be woken out of your first sleep by a rendering of "Jamrach's Evening Hymn." She left. The beast has behaved fairly well since, except that it eat up a handkerchief. ... It also insisted on taking tea with me yesterday and sent my cup flying into my plate, trying meanwhile to hide itself in the milk jug to prove an alibi. I am getting as bad as Aunt Charlotte with her perpetual cats, but I have seen very few human beings as yet, everyone being away, as this is a sort of holiday time....

Mandalay,

1 Feb. 94.

... I had a delightful petition brought me by a native in my guard who had got a Burman clerk to write it for him; he wanted to resign the police and his reasons were that his father and mother had died after him and that his uncle was generously ill. I hear you have a Persian kitten; of course I, who have the untameable carnivora of the jungle roaming in savage freedom through my rooms, cannot feel any interest in mere domestic cats, but I am not intolerant and I have no objection to your keeping one or two. My beast does not show any signs of getting morose; it sleeps on a shelf in its cage all day but comes out after dinner and plays the giddy goat all over the place.

I should like to get another wild cat to chum with it, there are several species in Burma: the jungle-cat, the bay-cat, the lesser leopard-cat, the tiger-cat, marbled cat, spotted wild-cat, and rusty-spotted cat; the latter, I have read, make delightful pets.

I hope you have no more bother with servants; my boy gives me notice about once a month but I never think of accepting it; if he doesn't know a good master I know a good servant, to paraphrase an old remark. He has a great idea of my consequence and of his own reflected importance; I sent him to a village with a message, and Beale A.S.P., who was expecting some fowls from that place, asked if they had been sent by him; he told me he should never forget the tone in which he said "I am Mr. Munro's boy!" Civis Romanus sum.

Mandalay,

7 Feb. 94.

... The men who bring grass carry it in two bundles thus:

The other day just as my grass man was bringing the fodder into the stable the mare came up from behind and catching hold of the hind bundle gave it a violent jerk, which brought the whole bag of tricks to the ground. I luckily had no stays on or they would certainly have burst.

Mandalay,

11.2.94.

I went to watch a game of polo last week; I long to play, and I am told that Gordon, of the military police, would mount anyone who cared to play, but at present I can scarcely find time to go and look on, much less go in for it regularly....

I am very interested in watching the vultures which congregate in great numbers just here; there are three kinds, 2 brown and 1 black; the latter is a fine bird and very much cock of the walk; whenever one comes to a carcase the brown birds have to leave off eating and wait till he's finished, trying to look as if they weren't in the least hungry. Usually only one eats at a time at a small carcase, but this morning there was a regular Rugby scrimmage over a particularly "ripe" pariah puppy, about 14 birds struggling for the choice morsel. Among the vultures I was astonished to see a lovely black eagle (Neopus Malayensis) but just as I got my field-glasses to bear on him, off he flew.

Mandalay,

30 March, 94.

... My boy has just got me some crows' eggs; the Burmans don't quite approve of my taking them as they have an idea that the spirits of their grandmothers turn into crows, but I cannot be expected to respect the eggs of other people's grandmothers.

Some absurd owls built themselves a nest inside my roof, which was a rash thing to do; of course I promptly took care of their eggs for them.

Where would one find English servants who, besides cooking one's food and bottle-washing generally, hunted for birds' eggs and routed out police cases (my boy is of more use to me that way than any of my police men, and is invaluable in the witness box, as he will swear not only to what he saw, but to what he thinks I should like him to have seen)? Fancy saying to an English cook "Dinner at 7 sharp, and I've three guests coming; and, by the way, just see if the buzzard's nest in the high elm has any eggs in it; and while you're about it find out if there is any gambling going on in the Red Lion, etc., etc." Pedrica would have wept scalding tears at such requests.

Maymyo,

23.4.94.

I am still delighted with this place, it is delightfully cool and we have whist every night and dine and breakfast in each other's houses rather more frequently than in our own; not much work to do, and a fair amount of sport to be had.... I heard a good story of some police officer to whom one of the petty Burman princelings wrote an official letter, styling himself as usual "Lord of a 100 elephants," etc., etc. The police officer in reply called himself Lord of i pony, a half-bred terrier, 3 puppies, 13 fowls and 1 duck. The princeling kicked up no end of a row.

My goose has hatched out a brood of goslings in spite of 40 miles' transit in a jolting bullock cart.

Maymyo,

26.5.94.

Don't count your chickens after they're hatched; it's quite as fatal as it was to number one's subjects in David's time. I was writing to Mr. Lamb out in the jungle last week and telling him what gentlemanly geese and ducks I had and how they multiplied exceedingly and waxed fat, etc., when a confounded messenger rode up with the following letter from the Head Constable:

Your syce report that 2 goose and 2 gooseling, duck 3, hen 1, died yesterday with deceased. Syce weeping tears,

Your obedient servant, etc.

P.S. I saw them lying dead and ordered them to dry in the sun."

English's poultry are dying too; he has just built a swagger fowl house so I wrote and told him that he was like the Rich Fool who built bigger barns, not that I wished to suggest for a moment that he was rich.

IN the summer months Hector got malaria very badly, and

in August had to resign and come home, to my great delight.

He told me that while lying in bed, feeling wretchedly ill,

in some hotel, he heard footsteps passing in the corridor

and called out. A German, a visitor like himself, and a

stranger to Hector, came in and asked what was the matter?

Hector told him he wanted a servant to bring him something

to drink; the German stood and argued that it was not his

business and he could not attend to sick people, neither

should he give a message to anyone, and then departed. Of

course he may have been mad, or madder than usual. It was

some time after that Hector attracted the attention of a

servant passing by and got what he wanted.

My father went to meet him in London and found he was too ill to travel down to Devon at once, so they stopped in town for a time, a nurse was engaged, and he gradually got better.

When he did arrive home, although looking ghastly ill, he lost no time in getting well, and soon bought a horse for the hunting season. But the fevers had weakened him so much that he could not last out a whole day's hunting until quite the end of the season.

However, we had some lovely times out together, in the hilly country between Devon and Cornwall, and these were priceless opportunities for Hector to study Devon types.

We had settled down at Westward Ho, in those days a gay and jolly place, and separated by eleven miles from the aunts.

A fox terrior, some Persian cats, and Agag, a jackdaw, with a passion for bathing, were our pets at that time. Hector shared that passion—not that they bathed together, but, wherever water was, he was not happy unless he was in it. We thought of keeping bears, but there were difficulties in the way, how to get them, chiefly. If a merchant travelling in wild animals had come our way, he would not have passed our gates in vain.

In the summer, in addition to sea-bathing and riding, there was tennis, a game Hector loved more than any other, and we had lots of fun on our sporting "putting" green, but apart from putting he never played golf.

Not more than three miles from Westward Ho there lived another witch, known personally to our housemaid, whose brother had been uncivil to her one day, and who was punished by a plague of creeping things all over him, which only left him next morning; but she is not the original of the witch in Hector's stories.

In 1896, Hector left for London, to earn his living by writing. Some Devon friends introduced him to Sir Francis Gould (then Carruthers Gould), who launched him in the literary world. He wrote for the Westminster Gazette political satires, called "Alice in Westminster," illustrated by Carruthers Gould, and afterwards published in book form, as "The Westminster Alice."

In these sketches all the characters are public men, chiefly Cabinet Ministers, portrayed as the animals, etc., in "Alice in Wonderland."

These were followed in 1902 by the "Not So Stories," also political satires.

The Munro clan has always been composed of fighters and writers. Our grandfather, a colonel in the Indian Army, had a great compliment paid him by the Marquis Wellesley of his day, who said that he wrote purely classical language. His writing was entirely, I believe, on Indian politics. Aunt Tom told us this—she always said Hector had inherited his grandfather's gift. At any rate, he wrote naturally and never went through a literary correspondence course. My mother's mother was a very clever woman, and she, through her mother, belonged to the Macnab clan. So Hector was Celtic on both sides of his family.

To me, his strongest characteristics were—whimsicality, keen sense of humour, love of animals, and pride in being Highland. There are people who think that to be fond of animals means domestic animals only; to include wild ones shows madness. Well—Hector must have been raving! It is possible to get a good deal more out of madness than sane people have any conception of!

Another characteristic was his indifference to money. His attitude to business is shown in "Clovis on the Romance of Business," in this volume.

I have kept, unfortunately, very few of his letters written from town. Some, in fact, I destroyed as soon as read, because my father insisted on reading any letters his sons ever wrote, and Hector and I sometimes had plans which we did not divulge to him at once.

Here is an extract from one written when he was chumming with a friend, one Tocke.

"My Dear E.

"The duck was a bird of great parts and as tender as a good man's conscience when confronted with the sins of others. Truly a comfortable bird. Tockling is looking well and is in better health and spirits generally, and everything in the garden's lovely. Except the 'Cambridgeshire' which we all came a cropper over. We put our underclothing on the wrong horse and are now praying for a mild Winter."

Sometimes when I left Westward Ho for a short visit, he

came down to "understudy" me, chiefly in looking after the

animals, and to see that Aunt Tom, who made a bee line for

our house as soon as she knew I had started, did not have

everything at sixes and sevens before I came back. This is

one from home.

"Aunt Tom came on a visit the day Ker left, but I am still understudying your place. She is horrified at the rapidity of my marketing (which has been so far successful), but I pointed out to her that it was doubtful economy to spend an hour trying to save a few halfpennies on the price of vegetables when other people spent pounds to snatch a short time by the seaside—and the quicker I marketed the sooner I got back. Of course she was not converted to my view.... On Wednesday we drove to Bucks and met a menagerie, so with two other traps we turned into a field to let it pass. Bertie and I went in on both nights to see the beasts, and made friends with the young trainer, who was quite charming, and had sweet little lion cubs (born in the first coronation week) taken out of their cage and put into our arms, also seductive little wolf-puppies which you would have loved."

He spent much time in the British Museum Reading Room

getting material for his book, "The Rise of the Russian

Empire." This was published in 1900, his only entirely

serious book, tracing the beginnings of Russian history to

the time of Peter the Great.

A friend writes that he is sorry the book is so little known, "for it is better written and more interesting than Rambaud's History of Russia, which I fancy is still the most widely read book on this subject."

Hector himself had not a great opinion of the book. He was charmed with the remark of our coachman who asked for the loan of it. I don't know how much of it he read, but one day he said to Hector, "I've read your book, sir, and I must say I shouldn't care to have written it myself."

Hector said it was the biggest compliment he had ever had.

The Bookman considered he had provided "an historical outline of no little value."

In August 1901 he had the experience of going to Edinburgh with Aunt Tom. At one time I wished that she had invited me too, but not after reading the following account.

Edinburgh,

17.8.01.

"My dear E.

"Travelling with Aunt Tom is more exciting than motorcarring. We had four changes and on each occasion she expected the railway company to bring our trunks round on a tray to show that they really had them on the train. Every 10 minutes or so she was prophetically certain that her trunk, containing among other things poor mother's lace. would never arrive at Edinburgh. There are times when I almost wish Aunt Tom had never had a mother. Nothing but a merciful sense of humour brought me through that intermittent unstayable outpour of bemoaning. And at Edinburgh, sure enough, her trunk was missing!

"It was in vain that the guard assured her that it would come on in the next train, half-an-hour later; she denounced the vile populace of Bristol and Crewe, who had broken open her box and were even then wearing the maternal lace. I said no one wore lace at 8 o'clock in the morning and persuaded her to get some breakfast in the refreshment-room while we waited for the alleged train. Then a worse thing befell—no baps! There were lovely French rolls but she demanded of the terrified waiter if he thought we had come to Edinburgh to eat bread!

"In the midst of our hapless breakfast I went out and lit upon her trunk and got a wee bit laddie to carry it in and lay it at her very feet. Aunt Tom received it with faint interest and complained of the absence of baps.

"Then we spent a happy hour driving from one hostelry to another in search of rooms, Aunt Tom reiterating the existence of a Writer to the Signet who went away and let his rooms 30 years ago, and ought to be doing it still. 'Anyhow,' she said, 'we are seeing Edinburgh,' much as Moses might have informed the companions of his 40 years' wanderings that they were seeing Asia. Then we came here, and she took rooms after scolding the manageress, servants and entire establishment nearly out of their senses because everything was not to her liking. I hurriedly explained to everybody that my aunt was tired and upset after a long journey, and disappointed at not getting the rooms she had expected; after I had comforted two chambermaids and the boots, who were crying quietly in corners, and coaxed the hotel kitten out of the waste-paper basket, I went to get a shave and a wash—when I came back Aunt Tom was beaming on the whole establishment and saying she should recommend the hotel to all her friends. 'You can easily manage these people,' she remarked at lunch, 'if you only know the way to their hearts.' She told the manageress that I was frightfully particular. I believe we are to be here till Tuesday morning, and then go into rooms; the hotel people have earnestly recommended a lot to us.

"Aunt Tom really is marvellous; after 16 hours in the train without a wink of sleep, and an hour spent in hunting for rooms, her only desire is to go out and see the shops. She says it was a remarkably comfortable journey; personally I have never known such an exhausting experience.

"Y.A.B.

"H.H. Munro."

I told Hector once that Aunt Tom's character should be

immortalized in some story.

"I shall write about her some day," he said, "but not until after her death."

She died in 1915 when he was learning to be a soldier, and has only appeared sketchily in his stories; "The Sex that Doesn't Shop," is chiefly about her.

Somewhere before 1902 Hector had a severe attack of double pneumonia in London. After his recovery he seemed to be much stronger than he had ever been before and continued so for the rest of his life.

In 1902 he was in the Balkans as correspondent for the Morning Post, a part of the world that had always attracted him.

To find a horse to ride, a river to bathe in and a game of tennis or bridge, were his first considerations after work had been seen to.

Sophia,

7.1.03.

Have been elected a visiting member of the Union Club, which is the social hub of the local universe; the English vice-consul and I fell into each other's arms when we each discovered that the other played Bridge. I have voluminous discussions in French with some of the leaders in the Bulgarian Parliament; I don't mean to say the discussions take place there; mercifully neither can criticise the other's accent.

Don't get humpy with L.B.; it is part of his nature to do odd things and he will never be otherwise. I can imagine him walking out of Heaven and saying "This place is run by the Jews." And at heart he is friendly.

Wyntour sent me a tiny silver crucifix to keep off vampires, which up to the present it has done.

Uskub,

20.4.03.

This is the most delightfully outlandish and primitive place I have ever dared to hope for. Rustchuk was elegant and up-to-date in comparison. The only hotel in the place is full; I am in the other. A small ragged boy swooped on my things and marched before me like a pillar of dust, while two blind beggars came behind with suggestions of charitable performances on my part. Then I was walked upstairs and offered the alternative of sharing a bedroom with a Turk or a nicer bedroom with two Turks.

I pleaded a lonely and morose disposition and was at last given a room without carpet, stove, or wardrobe, but also without Turks. The only person on the "hotel" staff that I can converse with is a boy who speaks Bulgarian with a stutter. The country round is "apart "; lovely rolling hills and huge snow-capped mountains, and storks nesting in large communities; everything wild and open and full of life. There are two magpies who seem to have some idea of living in this room with me.

Salonique,

9.5.03.

There is a "Young Turk," if you know what that means, staying in this hotel, very interesting and amusing. He has learnt and forgotten a little English, but the other day in the midst of a political discussion in French he took our breath away by starting off at a great rate "Twinkle, twinkle, little star" and went on with more of it than I had ever heard before. It's a funny world.

There is rather a nice Turkish dish one gets here, a cross between a junket and a cream cheese, eaten with sugar.

In the stampede here the other day when the attempt was made on the Telegraph Office I picked up a tiny kitten that was in danger of being trampled on and put it into a place of safety.

There was a highly-coloured account of our adventure with the piquet in the Neue Freie Presse.

This refers to his experience when "held up" as a

dynamiter—he sent the following account to the

Morning Post:

Salonica Railway Station,

April 30, 1903. (Midnight).

The reports which reached Uskub on Wednesday night and this morning of sinister doings at Salonica, of attempts to dynamite the line to Constantinople, and of the Ottoman Bank having been blown up, tempered by a cheerful official optimism that parts of the bank were still standing, prompted an immediate move towards the scene of disturbance.

In company with an American newspaper representative, whose last act in Uskub was to snapshot almost the entire Consular Body, which had turned out to see our departure, I started south by the train leaving at two o'clock in the afternoon along a line dotted throughout its length by frequent picquets, patrols, and small camps of railway guards. Before the train, slightly overdue, drew into the dark and apparently deserted terminal station the news was passed along by obviously demoralized officials that the town was in a state of siege, and that no one could be allowed to leave the station that night.

The first duty of a correspondent is to correspond, and a town in the throes of a revolutionary outbreak seemed to offer more attractions than a railway station tenanted with herded humans.

In the hope of slipping out by a side exit we therefore picked up our valises and made for an apparent outlet some five hundred yards distant across a waste of inconveniently overgrown grass. As a slight precaution against being mistaken for prowling Komitniki we turned down the collars of our overcoats so as to display the white collar, if not of a blameless life, at least of a business that did not call for concealment.

About four hundred yards of the distance had been covered when a frantic challenge in Turkish brought us to a standstill, and five armed and agitated figures sprang forward in the starlight and began to interrogate us at a distance, which they seemed disinclined to lessen. As five triggers had clicked and five rifles were covering us we dropped our valises and "uphanded," but without reassuring our questioners, who seemed to be possessed of a panic which might more reasonably have been displayed on our part.

Neither of us knew a word of Turkish, and Bulgarian was obviously unsuited to the occasion. Never in my study of that tongue have its words come so readily and persistently to my lips, and every French sentence I began became entangled with the phraseology of the debarred language.

The men had reached a point whence they were unwilling to approach nearer, and for a minute or two they took deliberate aim from a ridiculously easy range in a state of excitement which was unpleasant to witness from our end of the barrels.

At last two lowered their rifles, and after stalking round us with elaborate caution managed to secure our hands with a rope or sash-cord, which was hurriedly produced from somewhere. The operation would have been shorter if they had not tried to hold their rifles at our heads at the same time. When it was safely accomplished the statement that I was "Inglesi effendi" and the demand for our Consuls allayed their suspicions to a certain extent, but nothing would induce them to pick up my valise until the light of day should show its real nature, and it is still lying out on the waste land, where, if it explodes violently, no great harm will be done.

Arrived at the railway waiting-room, where the accumulation of apparently several trainloads was gathered in philosophic discomfort, the horrified officials flocked to release us with a haste which made the untying process almost as long as the binding.

The explanations on both sides had to be accepted for the moment, and two loud explosions in the distance made us feel that we had gained our security none too soon.

According to the information, doubtless panic-coloured, which was given us in nervous scraps by non-Turkish railway officials, the town is in. a condition which makes it dangerous to venture into the streets, the Ottoman Bank is in ruins, the Colombo and other hotels have been damaged by bombs, and many persons have been killed and wounded.