RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

IT was on a clear and beautiful June morning that the Valentine weighed anchor and sailed out of Plymouth Bay. Mr. Eustace Estcourt's yacht was small but elegant. Estcourt had started in life with a modest fortune which, however, he had quickly dissipated.

For years he had been a sort of social loafer, a hanger-on to the skirts of society. How Eustace Estcourt lived was a question that had been asked over and over again, but without eliciting any satisfactory reply. He frequented gambling clubs, race-meetings, and was generally to be seen at balls or parties given at the most fashionable and exclusive houses, the best dressed, the most careless, the gayest, and the most debonair of all the butterfly set of fashionables.

With all his faults (and he had many), Eustace Estcourt could at least lay claim to a good old name. He was the only son of Eustace Estcourt, who had been the younger brother of Hubert Estcourt, Baron Estcourt and Earl of Dallington.

Between the owner of the Valentine and the earldom of Dallington were three lives—those of the present Earl and of his two sons, Harold and Aubrey, both sturdy, fine, handsome young Englishmen, full of life and energy, and for whose death Eustace recognized he would have to wait a very long while.

To those who were acquainted with Eustace Estcourt's character, it was a source of great wonder to see the terms of close friendship that he was on with his two cousins, Harold and Aubrey. It was well known that, but for these two young men, Eustace would one day be the Earl of Dallington with almost limitless wealth at his command, but, as it was, it seemed that he was condemned to be plain Eustace Estcourt, without a penny to his name, to the end of the chapter. And yet with these two young men, who did him such a great wrong by existing at all, he was on terms of the closest intimacy. The wiseacres shook their heads, and said that 'no good would come of it.' And for once the wiseacres were right.

Upon this lovely July morning, when the Valentine shook out her white sails and bade goodbye to the white cliffs of old England, a small crowd of well-dressed people stood on her deck waving their last farewell to a few friends who had assembled upon the quay to see them off.

Prominent among those on the deck stood the owner, Eustace Estcourt himself, a strikingly handsome man of about thirty years of age, with hair of raven blackness pronounced aquiline features, with an upright, well-knit figure, delicately white hands, and small, well-shaped feet. Cast a passing glance upon him, and you would pronounce him 'a good looking fellow', but if you looked searchingly into that face you will notice that the mouth under that luxuriant dark moustache is hard and cruel, that the thin lips are drawn tightly over the sharp, white teeth, that the eyes are too deeply sunk in the well-shaped head, and that they looked crafty and cunning. I say you will notice all this if you are an observer, but, if you are only an ordinary person, these defects will escape you, for Eustace Estcourt is one who can keep his muscles well under control.

Not far from him stood the two brothers, Harold and Aubrey Estcourt. Harold was twenty-five years of age, and Aubrey twenty-four, and both differed exceedingly in their appearance from their cousin Eustace. For, in place of his inky hair, theirs was fair and curly, their features were more Greek than Roman in outline; no cunning lurked in the depths of their clear blue eyes, and a look of hearty good-humour overspread their merry English sunburned faces.

Beside the Estcourts were about half a dozen men who had availed themselves of Eustace's invitation for a two-month cruise in the Mediterranean. There was young Travers of the Guards—poor boy, a widowed mother's heart ached for him;—old General de Vaux, a veteran of the Crimea; Parchinton, of the Foreign Office; Vinson, a wine merchant, who, it was whispered, was a large-scale creditor of his present host's; Viscount Seary, an empty-headed young nobleman; and Lionel De Vaux, son of the General, and the bosom friend of Harold and Aubrey Estcourt.

Overhead the sun shone brightly from a bed of azure sky; beneath them the blue waters danced and glittered, A gentle breeze bellied out the sails, and, like a graceful sea-bird, the yacht sped on her course.

On board all was merriment and gaiety, and none were gayer or more sprightly than the host himself. Stories, songs, wine and cigars made the time pass quickly and pleasantly, and it was with surprise, when Eustace pointed across the sea, that the company saw that the white cliffs of Albion had sunk into the waters, and that they were indeed at last upon the open sea.

The Valentine left Plymouth upon 14 June, and it was upon the 27th of that month that a Sicilian barque, the Esperanza, picked up, about six miles westward of Cagliari, a small open boat containing one passenger.

The captain and crew of the Esperanza were, without exception, Sicilians, and could speak no word of any other language than their own, and as Italian was an unknown tongue to the rescued man, he was obliged to keep his story till the arrival of the Esperanza at Naples, where he made the following statement to the British Consul.

'My name is Eustace Estcourt. Upon 14 June I and some friends sailed from Plymouth in the yacht Valentine, of which I was owner. Upon 24 June, at 11.30 pm, a cry of 'fire' was raised on board. I rushed to the deck and found the whole vessel wrapped in flames. To save the yacht was an impossibility, and all that we and the crew could do was to endeavour to save ourselves.

'The night was a calm one, and this task would have been easy had it not been for the extreme cowardice shown by everyone on board. Unaided, I launched the small boat in which I was picked up. I hastily threw in a few provisions, for we were far from land, and I did not know how long it would be before we were picked up. This done, I begged some of my companions to accompany me, but one and all resolutely refused to face the terrors of a voyage in a small boat on the open sea, and obstinately clung to the burning yacht. I prayed and beseeched them to come, but without avail. In particular I urged upon my two cousins, Harold Estcourt and Aubrey Estcourt, to leave the burning ship, but they seemed too overcome with terror to pay heed to what I said. At last, after wasting my breath and imperiling my own life by remaining close to the burning yacht, I was obliged to push off, and as I did so the vessel, which was more than half consumed, sank bows foremost and I was left alone upon the sea.

'For three days I endured all the pangs and privations of a shipwrecked sailor, till at last, Heaven be praised, I was rescued by the crew of the Esperanza, by whom I was shown every kindness, and thus, having now recovered from the hardships I have undergone, I am able to tell you my sad story.'

'A very curious story it is, too,' replied the Consul. 'Of course, Mr.—er—Mr. Estcourt, you will be required to repeat all that you have said on oath.'

'Yes, of course,' replied Estcourt, perceptibly paling under the Consul's steady scrutiny.

'Would you be kind enough to furnish me with the name of your guests and the crew?' continued the Consul, taking up a pen.

'With pleasure,' replied Estcourt. 'Besides myself, there were my two cousins, Harold and Aubrey Estcourt, General De Vaux...'

'What!' exclaimed the Consul, looking up sharply. 'Did I hear you aright... General De Vaux?'

'Certainly. I said General De Vaux.'

'Do you mean the General De Vaux, the man who, during the Crimean, was known by no other name than that of "Old Fear-nought"?'

'He is the gentleman to whom I referred.'

'And you mean to tell me,' persisted the Consul, 'that that man, the hero of a hundred fights, was so paralysed by fear that he made no attempt to save his life on the burning yacht?'

'I have told you, sir,' replied Estcourt, biting his lips nervously, 'that such was the case. There are, I believe, many men who on shore are as bold as lions, but who are the veriest cowards on board a ship, and I suppose General De Vaux must be classed with them as a "dry-land hero".'

'It is hardly credible,' said the Consul, biting his pen and glancing suspiciously at Estcourt. 'But please proceed.'

In compliance, Estcourt gave the names of all who had been with him on board the ill-fated Valentine. The interview lasted about an hour and a half, and, after all formalities had been transacted, Estcourt, with a sigh of relief, left the Consulate.

He seemed to be in no hurry to return to his native land, but remained for some days in Naples, whence he travelled on to Rome, Florence and Milan.

Whatever his plans might have been, they were altered by a letter which reached him when at Milan, informing him of the sudden death of his uncle, the Earl of Dallington, on consequence of the shock that had been caused him by the death of his two sons. The letter, which was from the family solicitors, went on to inform Eustace Estcourt that, in consequence of the tragic death of his two cousins, Harold and Aubrey, he, Eustace Estcourt, being next of kin, was now Eustace, Baron Estcourt, and seventh Earl of Dallington, in the county of Warwickshire, and the possessor of the magnificent estates and vast rent-roll that should have come to his cousins, who were now lying asleep for ever beneath the blue waters of the Mediterranean.

There is no fairer spot in all this beautiful England of ours than that part of the Cornish coast where lies the little sea-girt town of Twycombe.

Early one morning towards the end of last year's summer, Sexton Blake was strolling along the pebbly sands by the edge of the sea. Over his arm he carried a towel, and the damp aspect of his hair gave proof to the fact that he had just been enjoying an early dip in the clear, sparkling sea.

To all men who work their brains to any extent, a change of scene and of life is occasionally very necessary, and so, after several months of arduous work, Sexton Blake, finding upon his hands a little leisure time, resolved upon a week's holiday at some quietly remote place, and he found that Twycombe was a spot eminently suitable as likely to afford perfect rest, for a period, to his somewhat over-wrought brain; but, alas, for 'the best-laid plans of mice and men'!

Upon this beautiful morning—the last that he should see at Twycombe for many days to come—Sexton Blake felt a strong reluctance to retrace his footsteps to the little primitive town, although he knew that his good landlady, Mrs. Polgarthen, of the Sun Hotel, had no doubt prepared a substantial breakfast for him.

He strolled along by the edge of the sea, and presently did what ninety-nine people out of a hundred would have done under the same circumstances: he began to idly pitch small stones into the shining water.

A pebble was poised in his hand, when his eyes fell upon a small black object that was floating not far from the shore. It was a handy target, and in another second the stone was whizzing through the air, but it fell short of the goal. Another, and another followed, but with like success: some fell too far, some too short, and not one hit the mark. There are some men who do not like to be done, even in such trivial matters as stone-throwing, and of these Sexton Blake is one. He threw his towel to the ground, and in a few minutes a perfect shower of missiles flew through the air.

It was some while ere Blake succeeded in his self-imposed task, but presently, impelled nearer towards the shore by the current, the black object was hit at last by a small stone, and it gave forth a clinking sound.

'A bottle!' said Sexton Blake. 'That's curious! A bottle generally floats neck uppermost, that is if it is partially filled with water, this bottle floats on its side, therefore it contains no water; ergo, it is corked.'

Accustomed as he was to quick reasoning, this man's subtle brain was immediately filled with conjectures as to why the bottle was corked, what it was doing, floating about at the mercy of the waves, and a thousand other things that no ordinary man would probably have worried his head about.

So curious did Sexton Blake become on the subject of this derelict bottle that he began to watch with anxious eyes the course that it was pursuing. Nearer and nearer-it came to the shore. At one moment it seemed almost within reach, and Sexton Blake, regard-less of the well-being of his clothes, leaned over to reach it, but a small wave carried it off again and he had to retreat to the shore, rattled and wet.

To obtain possession of that bottle now became the sole aim of Sexton Blake's life. The more it evaded him, the more eager he became for its capture. It was a tantalizing chase: one moment the sea brought it bobbing up under his very nose, the next it was far away again.

'Well, here goes!' cried Sexton Blake at last. 'I'll have that bottle at all hazards.'

In a twinkling his clothes were lying on the beach, while their owner was splashing through the water in chase of the exasperating quarry. Dripping, breathless, but triumphant, he returned to the shore, holding in his hand a magnum champagne-bottle, tightly corked and sealed.

His eyes glistened with triumph as they noted with what carefulness the bottle had been made watertight. He felt that he was on the eve of some discovery: perhaps the bottle contained the last words of some poor shipwrecked mariner, some last message of love to the dear ones at home. Some such documents did Sexton Blake expect to find. Little did he dream that it was no message of affection that this bottle had guarded from the mighty deep, but a message of dark and bitter vengeance.

Dashing the bottle on to the beach with all his force, he burst it open, and there, as he had foreseen, he found a roll of paper in its interior.

Hastily resuming his clothes, he thrust the document into his pocket, determined to digest its contents and his breakfast at the same time.

As he had expected, Mrs. Polgarthen had prepared a sumptuous repast for him, and he found the good lady in a state of anxiety, brought about partly because of his non-appearance, and partly because she was in sore fear lest the breakfast, which her careful hands had prepared, should spoil.

On the latter point, however, she was speedily reassured, for her guest did ample justice to the spread before him. So solicitous was Mrs. Polgarthen that Sexton Blake should lack for nothing that she buzzed about the room to the silent annoyance of the detective, who was impatient to have a look at his treasure-trove.

At last, however, the excellent Mrs. Polgarthen buzzed herself out, and Sexton Blake drew out the manuscript and in a few moments was deep in its perusal. The clock on the mantelpiece ticked the minutes away one by one, but still Sexton Blake, utterly forgetful of his breakfast, read on.

Presently he uttered a cry of amazement, which was followed soon after by an exclamation of horror. He rose to his feet and paced excitedly up and down the room for a few minutes. At length, when he had sufficiently mastered himself and had again resumed perfect control of his feelings, he rang the bell.

'Mrs. Polgarthen,' he said, when that lady put in an appearance in answer to his summons, 'I shall be greatly obliged if you will find out for me when the next train leaves for town.'

'For town! La, sir! You are never thinking of leaving us? I thought your stay was for a week, and this is only your second day.'

'It is imperative that I return to town, and at once. I am indeed sorry to leave you, but it is a matter of life and death!'

'Life and death! Oh, lor', sir! I do hope nothing's occurred, but I'll go and find out about the trains at once.'

When she had gone, Sexton Blake smoothed out the document, the cause of the sudden change in his plans, and laid it on the table, and again began to examine it critically.

While he is so engaged, let us take a peep over his shoulder at this dingy sheet of paper, upon which is written the following remarkable narrative:

The yacht Valentine, 24 June 1889, 11.35 pm.

A cry of 'Fire!' has just aroused the ship. I, Harold Estcourt, the writer of this, was in my stateroom when my brother Aubrey came into me in a state of excitement bordering upon frenzy. 'The yacht is on fire,' he cried. 'Save yourself!'

I leaped from my bunk and, accompanied by my brother, made my way through blinding smoke on to the deck. Here a sight of awful horror greeted us: the whole of the ship was a mass of flames. I made my way up to one of the crew, who stood as though stupefied, and asked: 'Is there no chance to save the yacht?'

'None,' he replied, 'the fire has broken out in no less than eight different places at once.'

I stood aghast. 'Then it is a deliberate plot to destroy the ship? I asked.

'Yes, sir,' he replied, 'there can be no doubt about that. It is a fiendish plot to murder us all.'

'Then we must take to the boats!' I cried.

For answer he pointed to the bulwarks of the vessel, towards the spot where I had been accustomed to see the boats. They had gone!

'Where is Mr. Estcourt?' I demanded.

'Mr. Estcourt,' replied the captain of the yacht, who had approached us, 'is a villain! He has gone with the boats.'

'What! Is he not still in his stateroom?'

'No, sir. I repeat he has gone with the boats, after first setting fire to the yacht in eight places and cutting off every means of escape.'

'Great heavens!'

Like a flash the whole of this man's—my cousin's—treachery burst across me.

For this end, then, had he made all his friendly advances to lure us here far from the help of our fellow-creatures and to ruthlessly murder us for the sake of the titles and estates that would be his were it not that my brother and I stood in his way.

Why, I asked myself, is he not content with the murder of us and the crew, but that he also wishes for the blood of the old General and our other friends? I think I can see through his devilish cunning. He will say that the burning of the Valentine was an accident, that he alone survived. The fact that others besides my brother and myself met their deaths will give colouring to his lying tale.

The captain tells me that only a few minutes of life remain to us. In five minutes, he says, the Valentine will sink. What I have to do I must do quickly.

I, Harold Estcourt, accuse Eustace Estcourt of the deliberate and cold-blooded murder of my brother, myself, the crew and guests on board the yacht Valentine, now lying in the Mediterranean Sea, and in support of this statement are the names of all who are at the present moment on board the Valentine.

[Here followed the names of the writer and his friends, and the crew of the Valentine: Harold Estcourt, Aubrey Estcourt, Malcolm De Vaux (General), John Parchinton, Hubert Travers, Moses Abel, Vinson, Seary, Lionel Malcolm De Vaux, Frederick Symmonds, captain of the Valentine, Frank Hurst, William English, and John Paulton.]

Appended to this manuscript was a footnote in the writing of Harold Estcourt:

This document will be enclosed in a bottle, tightly sealed, and then cast into the sea. If it should ever reach land, and these lines ever be seen by human eyes, I adjure the finder, by all that he holds dearest, to bring this awful crime to light, and bring punishment upon him who has the murder of twelve human beings upon his black soul.

Harold Estcourt

Thus, after being tossed upon the bosom of the sea for five years, the bottle containing this awful accusation had fallen into the hands of the one man who of all others was most fitted to carry out the dying wishes of the murdered Harold Estcourt.

Sexton Blake folded the manuscript, and carefully placed it in his pocket-book as Mrs. Polgarthen made her reappearance, and in less than an hour he was whirling towards London as fast as steam could take him.

IN a small room within the sacred precincts of Scotland Yard sat Sexton Blake, in earnest conversation with a gentleman well known as the head of the Criminal Investigation Department.

Upon the table before them lay the document which Sexton Blake had providentially found upon the sea-shore at Twycombe.

'This is a most startling piece of news, Mr. Blake.'

'It is indeed, sir. May I ask how you propose to act?'

'I see many difficulties in my way in this matter, for the accused person is a man of high rank. But still, I have my duty to perform, and I will do it. I shall immediately order a warrant for the arrest of the Earl of Dallington on the charge of murder on the high seas.'

'You will do right, sir. I think we agree that this evidence is indisputable, the handwritings of the signatories can be examined and, I have no doubt, verified. Shall you do this before putting the warrant into execution?'

'I hardly know; perhaps it would be the safer plan; but we must be careful not to excite the suspicions of the Earl or he may give us the slip.'

'Just so. If I might suggest, I would recommend that this be kept entirely secret.'

'Then I agree with you, Mr. Blake, and now I will set to work on this case, which, as far as I can judge, seems to be one of unparalleled atrocity.'

Sexton Blake took the hint that the chief wished to be left alone, and so he took up his hat and departed.

He returned to his own rooms, impatiently expecting to hear some news of the further developments of the case; but a couple of days passed without bringing anything fresh, so that he almost wished that he had stayed at Twycombe and communicated with the police authorities by post. At length, however, on the morning of the third day, news did reach him in the form of a telegram, which ran as follows:

COME HERE, IF POSSIBLE, AT ONCE—FLJ.

It was possible, and he went, and soon found himself face to face with the chief.

'Well, Mr. Blake,' was the greeting received, 'have you heard the news?'

'No, sir. I have heard nothing since we last met.'

'Well, our bird has flown!'

'You don't mean to say that Lord Dallington has escaped?'

'Such is my meaning. I entrusted the warrant for his arrest to a man in whom I have hitherto placed much reliance, but there was some bungling somewhere, and the secret leaked out. When my man arrived at Dallington, in Warwickshire, my lord—er—had gone—gone and left not a trace behind him. The whole case seems to have come out somehow. Look here! The papers have got hold of it, and are making capital out of it.'

The chief threw a copy of a popular daily across to Blake.

Under the headline, 'Murder Will Out', more than a column and a half was devoted to the extraordinary finding of the bottle containing the accusation of murder against the Earl of Dallington, and our hero's name was prominently mentioned several times, coupled with frequent complimentary allusions to some of the most remarkable cases in which he had been engaged.

'Well, what is to be done?' asked the chief, when Blake had mastered the contents of the newspaper article.

'In the first place,' replied Blake, 'will you hand the elucidation of the case over to me? You see that, as the original finder of the document, I have an obligation to perform to the dead man who wrote it.'

'I will willingly do so,' replied the chief eagerly. 'I am mortified and disgusted by the way my man has mismanaged the affair.'

'But perhaps the fault does not lie with him,' said Blake, anxious to stand up for a less fortunate detective. 'Is he a man I know? What is his name?'

'Pinniger—Sergeant Pinniger.'

'One of the most able men in the force.'

'So I thought till this occurred.'

'Depend upon it,' said Sexton Blake generously, 'the blame in the matter cannot rest on Pinniger. He is a smart—a very smart man. Is he here?'

'Yes, I believe he is below. Would you like to see him?'

'Very much.'

The chief touched a small electric button, and then called through a speaking tube, desiring that Sergeant Pinniger should come to his room.

In a few minutes the door opened, and the sergeant made his appearance. He was a broadly-built, active-looking man, with a clean-shaven, expressive face, which seemed to have the word 'detective' written right across it. Now, Sexton Blake's appearance would not for a moment lead one to believe that he was a detective by profession, and thus he possessed the first essential for making a successful detective—that of looking as little like one as possible.

Sergeant Pinniger bowed and stepped into the room, looking round with rather a sullen expression, as though he knew that he was in disgrace, and that someone else had been entrusted with the mission in which he had failed.

'Mr. Blake would like to ask you a few questions, Pinniger,' said the chief, 'and I should like you to answer them as concisely as possible.'

The detective bowed without replying, and turned to Sexton Blake.

'You left for Warwickshire, Sergeant Pinniger?'

'Yesterday morning.'

'And you arrived there?'

'At three in the afternoon.'

'At what hour did you get to Estcourt House?'

'At half-past four.'

'And you found the Earl gone? When did he disappear?'

'Early in the morning.'

'What inquiries did you make?'

'I found out that the Earl had received a telegram in cypher from London, and that immediately on receipt of it he had packed up some belongings, together with all the money and jewellery in the house, and left by the first train for London, so that I must have passed him on my journey down.'

'And then?'

'And then, as there was nothing more to learn, I returned.'

'You have done very well indeed,' said Sexton Blake gaily. 'To you the honour belongs of finding the first clue.'

'I fail to understand,' said the chief.

'And yet it is very plain,' responded Sexton Blake. 'In the first place his lordship received a telegram in cypher from London. Ergo, he has an accomplice in this city, whose duty it is to inform his lordship if any danger threatens. Now, the question is, who can this accomplice be? He must be someone in a position to receive early news of a threatening disaster. I shall find out who he is; that is my first business.'

'Mr. Blake thinks himself very clever, no doubt,' said Pinniger sneeringly, 'but, with all due deference to his sagacity, I don't think he will succeed.'

'There you and I agree to differ, my dear sir,' said our hero, good-humouredly. 'And now, sir,' addressing the chief, 'with your permission I will retire and commence my investigations.'

'Do so, Mr. Blake. Any money that is necessary you will, of course, call upon me to provide.'

'I will keep an account of my expenses, which I will hand to you, sir, When the criminal is brought to justice.'

Pinniger smiled sardonically. 'In that case, sir, I am afraid Mr. Blake will never trouble you with his account.'

'We shall see,' replied our hero, as he bowed and made his exit from the room.

'A very good plan, and one that I invariably follow,' said Sexton Blake to himself, as he turned round the corner by the Charing Cross Road, 'is to begin at the beginning. Therefore, as the beginning of this little drama lies at Dallington, in Warwickshire, that place is my first destination.'

He hailed a hansom and drove to his chambers, where he made a few necessary alterations in his attire, packed a valise, with the warrant for the arrest of the body of Eustace Estcourt, Baron Estcourt and Earl of Dallington, in his pocket, he again re-entered the hansom, and drove rapidly off to Paddington Station, where he was just in time to catch an express to Manston, the nearest station to the village of Dallington, where the seat of the Estcourts was.

It was late at night when the journey to Manston was accomplished, and so, much against his will, he had to put up at the Head and Crown, the small and only inn of which the place could boast.

He was up, however, with the lark in the morning and, hiring a horse and trap, drove over to Dallington, a distance of sixteen miles.

A fine old Elizabethan mansion was Estcourt House, the seat of the Earls of Dallington; and, as Sexton Blake turned in at the huge wrought-iron gateways and drove past the lodge and up an avenue of superb chestnuts, he reflected that it was indeed a strange mission he was on, to seize the master of this beautiful domain and arrest him on the charge of a horrible and inhuman murder.

A footman in gorgeous livery answered his ring.

'His lordship is not in?' asked Sexton Blake, well knowing what the answer to his question would be.

'No, sir.'

'Can I see the housekeeper?'

'Mrs. Grey? Yes, sir. What name shall I say?'

'My name is Blake, but Mrs. Grey will probably not know me by name. Will you kindly say that I wish to see her on particular and urgent business connected with the Earl of Dallington?'

'Yes, sir.

'The man withdrew, and a few minutes later returned with the information that Mrs. Grey would see Mr. Blake.

Our hero followed the servant through a hall paved with marble, and with many trophies of the chase suspended from the walls, till they came to a door at which the footman knocked.

'Come in! cried a voice; and in a few moments Sexton Blake found himself in the presence of a white-haired old lady, who regarded him very curiously for a few moments.

'Madam,' commenced Blake, 'I have come on an errand of a very unpleasant...'

'Are you the Mr. Blake mentioned here?' interrupted Mrs. Grey, pointing to a copy of a daily paper lying on the table.

Sexton Blake started: he had forgotten the newspaper article.

'Yes, I am,' he replied.

'Then, Mr. Blake, I suppose you have come down here to try and find his lordship, and that you want my help?'

'I do, most certainly, Mrs. Grey.'

'Well, you shall have all the aid I can give you in bringing that monster to justice. To think that he killed poor Master Harold, and Master Aubrey too, whom I used to nurse when they were babies, poor mites without a mother!' The good soul wiped the tears from her eyes. 'Oh, the black-hearted monster! Tell me, Mr. Blake, how can I help you?'

'By answering a few simple questions, Mrs. Grey. First, a telegram arrived early in the morning of the day before yesterday; will you tell me where Lord Dallington was when he received it?'

'Yes, I can tell you that, for I took the telegram up to him myself. He was in his study.'

'Will you take me to the room?'

'Certainly.'

'The old housekeeper led the way through the hall and up a broad flight of stairs, and turned into a room upon the first floor, with Sexton Blake close on her heels.

He looked round the room. It was in a state of utter disorder: papers lay strewn upon the tables; boxes were opened and their contents spread upon the floor; the waste-paper basket and the fireplace were filled with torn scraps of paper.

'I see that this room has not been touched since the Earl disappeared.'

'No.'

'That is well. Now, Mrs. Grey, will you do me the favour of allowing me to begin my search here at once?'

'Certainly. Would you like me to leave you?'

'That is quite unnecessary. In fact, I should prefer you to stay, as I may have some questions to ask.'

Mrs. Grey seated herself, and then began to watch Sexton Blake's movements with great curiosity. First he took a sheet of brown paper, which he spread on the floor; on to this he emptied the contents of the waste-paper basket; and then he commenced a systematic search through the miscellaneous rubbish with which it had been loaded.

This search evidently did not prove successful for, when he had carefully examined every particle of paper, he returned it all to the basket and then gathered together all the torn fragments which littered the fireplace.

Most carefully did he scrutinize every tiny fragment, till at last, with a sigh of relief, he picked out a scrap of dirty pink paper, which he laid on one side, and then another piece and another, till he had exhausted the contents of the fireplace.

Quite a heap of torn shreds of pink paper rewarded his efforts, and then he set to work to piece together all the fragments, and in an incredibly short space of time the telegram which the Earl of Dallington had received two days previously lay before him in its entirety.

'The first clue!' he exclaimed, in a voice of triumph.

Mrs. Grey arose, approached the table, and looked curiously at the telegram.

'Deary me!' she exclaimed, thoroughly mystified. 'What ever is it all about?'

For the telegram written in cypher ran as follows:

HUU AHN DEKT PE URMAP. QUJ GEL JESL URQT. TSMTEBT

Sexton Blake explained to her that it was a cypher or cryptogram, and then, copying out the arrangement of letters carefully on to a sheet of paper, placed it in his capacious pocket-book.

'Now, Mrs. Grey, I have another question to ask you. Did the Earl write any letters that morning before he left?'

'Yes, I think he wrote one to his bankers.'

'Ah, I thought as much. Where did he sit when he wrote the letter?'

'I cannot say for certain, but he usually sat just where you are sitting now.'

'Good! Then he probably used this blotting paper?'

'Very likely, sir.'

'What are the names of Lord Dallington's bankers?'

'Ormsdale and Chalfont, of Lombard Street, in the City of London.'

'Can you procure me a mirror, Mrs. Grey?'

Mrs. Grey, more thoroughly mystified than ever, went out, and in a few minutes returned with the desired article.

Each sheet of blotting paper was then subjected to a careful examination.

'Ah! Here we are at last. Ormsdale and Chalfont you said, did you not, Mrs. Grey?'

With the aid of the looking-glass, Sexton Blake read the following letter, which had been imprinted on to the blotting paper:

Messrs. Ormsdale & Chalfont.

Gentlemen,—

I wish to give notice that I require to draw from your bank the sum of fifty thousand pounds which I have on deposit with you. On Thursdays next, September 4th, at 3.30 pm my representative will call and present a cheque for the amount, which I shall be obliged by your paying in fifty Bank of England notes for one thousand pounds each.

Faithfully yours,

Dallington.

'Thursday, September 4th! ejaculated Sexton Blake. 'Why, that is today. What is the time now?' drawing out his watch. 'Ten minutes to ten. Here is a too important clue to be missed. At all hazards I must be at Lombard Street at half-past three. True, I could wire instructions to Scotland Yard that the bank is to be watched, but it is probable that Pinniger would be the man instructed with the duty, and I have a strange feeling of distrust about that man. I must go myself. The only question that arises is: can I get there in time? It is the best part of two hours' drive to the station; that brings it to twelve o'clock. Supposing I can catch a train immediately, it is a four-hour journey to town; that brings it to four o'clock. That will never do. I should be an hour late at Lombard Street. Mrs. Grey, can you tell me when the next train for London leaves Manston?'

'At three minutes to eleven, Mr. Blake.'

'Ah! And what time does it arrive at Paddington?'

'It is a fast train, and arrives at six minutes after three.'

'I must catch that train.'

'But it is impossible, Mr. Blake; it is sixteen miles to the station and it is now ten o'clock; no horse here could do the distance in the time.'

Sexton Blake struck his head with his open palm. 'I must catch that train.'

'But how?' cried the old lady, getting agitated, as Sexton Blake's impatience arose. 'I've known my son Tom get to Manston within the hour, but...'

'What horse did your son ride?'

'No horse at all, sir; he rode his bicycle.'

Sexton Blade leaped to his feet. 'His bicycle!' he exclaimed. 'Is it here?'

'Yes, it is in the coachhouse.'

'Then it is my only chance. I was a good rider a few years back; perhaps my hand, or rather my foot, has not lost its cunning. You will lend me your son's machine; if any accident happens to it I will repay him handsomely.'

'There need be no talk of payment, Mr. Blake. You shall have the bicycle.'

Three minutes later Sexton Blake, with his hat jammed on his head and his trousers tucked up, was pedaling down the smooth avenue at a furious rate. The gate stood open, and he dashed into the road.

Before him lay a journey of sixteen miles, which he had to accomplish in exactly sixty minutes. To a great many cyclists such an undertaking would not be considered in the light of a very grand feat, but it must be borne in mind that at least five years had elapsed since Sexton Blake had sat astride the iron horse and, further, that he was not attired in a suitable costume to do the journey in comfort.

At first all went merrily enough: the wind, though slight, was favourable, and the hedges flew by in a very satisfactory manner.

Then the unusual action began to tire our hero's legs; the sun became unpleasantly hot, and his mouth got parched and dry.

'Eleven miles to Manston,' said a finger-post. Sexton Blake drew out his watch—twenty minutes had elapsed since he left Estcourt—he was behind his time. He had accomplished only five miles in the first twenty minutes. It was disheartening, but he redoubled his exertions, and jammed the pedals round. 'Eight miles to Manston,' said the next signpost. Ah! That was encouraging. He had accomplished the last three miles in ten minutes. The only thing that troubled his mind was, could he keep up the pace?

The stiffness of his legs was beginning to wear off; but an unpleasant, cramped feeling in his back began to torment him; besides which, the perspiration was streaming down his face and his mouth was so dry that his tongue clave to the roof. Like a Trojan, however, he stuck to his work. The road, which had hitherto been fairly level, now began to get hilly, and therefore the work harder; but he did not allow himself to despair, especially as the wind momentarily grew stronger and helped him on his way.

Up hill and down dale he went, yelling like a Red Indian on the war-path when some rustic stood gaping round-eyed in the middle of the road, or when some contemplative cow thoughtfully and deliberately meandered across his path, to the infinite danger of a collision.

It was a race against fleet-footed old Father Time. The milestones flew by, but so did the minutes. At last, however, but one mile remained to complete. But what a mile! Half of it consisted of climbing a very steep hill, and the other half of descending it.

At the hill our hero went like an arrow from a bow. It was a tough climb, and his breath came in pants, while his face went the colour of a freshly-boiled beetroot; but he got to the top and slackened speed for a moment to regain his breath, but on looking down he saw something that made him redouble his efforts, for below him was the train that he had struggled to hard to catch just rounding a curve. In another minute it would be in the station. The pedals of the machine whizzed round, the air whistled past him as he dashed down the hill for all he was worth.

The train was in the station, and the guard had the whistle to his mouth to give the signal to start when there came a crash. Sexton Blake had lost all control of the bicycle half way down the decline. There was no brake, and so the runaway machine sped unhampered on his way. Before him was the station; the door stood open, and he had the choice of dashing up against the brick wall or of guiding the machine into the open door. He chose the latter, yelling all the time at the top of his voice to clear the way.

As the machine came crashing through the doorway, Sexton Blake flung up his hands and clutched the framework over the door.

As the machine came crashing through the doorway, Sexton Blake

flung up his hands and clutched the framework over the door.

The bicycle was hurled right across the waiting-room and bent nearly double, but luckily no other damage was done.

A moment later Sexton Blake, crumpled, dusty, perspiring at every pore, but victorious, was gasping for breath upon the seat of a first-class railway carriage in the London train.

SEXTON BLAKE was not the man to content himself with looking out of the window on a four-hour railway journey. The first thing that occupied his attention when he had regained his breath, and when his blood had resumed its normal circulation, was his personal appearance, which, indeed, sadly needed repair.

This done to the best extent in his power, he reseated himself and, drawing out his pocket-book, began to study the cypher telegram. As has been before stated, the telegram ran:

HUU AHN DEKT PE URMAP. QUJ GEL JESL URQT.—TSMTBT

As a rule cyphers of this description are by no means as hard to solve as would at first appear.

In this case the very first word gave Sexton Blake a clue that he was not slow to grasp. 'Here is a word,' he muttered to himself, 'of three letters, of which the latter two are the same. Now what are the commonest words in the English language so constructed? There are, for instance, the words 'see', 'lee', 'fee', 'ass', 'all'. I should be inclined to give the preference to the last word—'all'; it seems to be the most likely. So, on this supposition, I shall replace the letter 'h' by the letter 'a', and 'uu' by 'll'. This gives me a clue to the next word, which is of three letters, of which the second one is 'a'. It requires no great wisdom to see that the second word is 'has'. 'Why,' exclaimed Sexton Blake, 'this cypher is simplicity itself; a child almost could solve it. I shall be the master of that message in something under ten minutes.'

Sexton Blake was right. In less than the time he had estimated, the solution of the telegram was accomplished:

ALL HAS COME TO LIGHT. FLY FOR YOUR LIFE.—EUGENE.

'It is as I thought,' ruminated our hero. 'The Earl received this warning from someone who is behind the scenes, as it were. Now, who can this Eugene be? I have an idea. It is a wild one, perhaps, but still I shall probably be able to verify it at the bank, for, if I am not mistaken, the representative mentioned in the Earl's letter to his bankers and this Eugene will probably turn out to be one and the same person.'

For a wonder, the train was on this day punctuality itself, and it drew up at Paddington Station as the hands of the big clock pointed to the five minutes after three.

Sexton Blake hailed a hansom and drove rapidly off Citywards, stopping on the way at a hosier's to purchase a clean collar, so as to enhance his personal appearance.

At twenty-seven minutes past three the cab turned into Lombard Street at the Gracechurch Street end. Here Sexton Blake stopped it, sprang out, paid the driver a liberal fare, and walked hastily in the direction of Ormsdale and Chalfont's bank.

As he reached the door the clock over the post-office pointed to the half-hour after three. He was punctual to the minute. Would the other man prove so?

Hardly had the thought passed through his mind when an elderly man of venerable aspect, with snowy hair and beard, pushed his way into the bank. He was carefully dressed in the orthodox high hat and black frock-coat, and he carried in his hand a small, brown, leather bag.

There was nothing suspicious in the old gentleman's appearance; but as he passed Sexton Blake closely our hero started—an intuitive feeling prompted him. Here was his man; he was sure of it! In spite of the white hair and beard, there was something very familiar about the clear-cut features; the carriage too, of the elderly gentleman did not coincide with his venerable appearance, for it was upright and his tread was elastic.

The door had scarcely slammed to when Sexton Blake pushed it open and entered the bank.

There were a good many people at the counter waiting to be served, and Sexton Blake hid himself as much as possible among the crowd, keeping, however, a very watchful eye all the time on the suspicious character.

He saw the old gentleman produce a cheque and hand it to the cashier, and his quick eye did not fail to note that the hand that presented the cheque trembled visibly.

The cashier who received the cheque glanced in a surprised manner at the amount, and then hurried, cheque in hand, into the manager's room, whence in a few moments he returned, and handed a large roll of notes across the counter.

The old gentleman rapidly counted the notes, then thrust them into a bag and left the building. Once outside he called a cab and, giving the driver some directions, was driven rapidly off.

There are no lack of cabs in the City, and Sexton Blake, hailing another, showed the driver a sovereign.

'For you,' he said briefly, 'if you do not lose sight of that cab,' pointing to the one which the old gentleman had taken.

'Right y'are, guv'nor!' replied the cabby. 'You needn't put it back in yer pocket; it's a quid easy earned.'

The two cabs drove off at as rapid a pace as the dense traffic would permit. Down Queen Victoria Street they went and over Blackfriars Bridge, then they turned into one of those dingy streets that abound on the Surrey side of the river.

Suddenly the cab in front pulled up before a house of a very disreputable appearance; but Sexton Blake's cabman, who was evidently an old bird at the game of shadowing, drove slowly by, to enable his fare to see the number of the house at which the other cab had stopped.

He turned the first corner and pulled up.

'Well, guv'nor,' he inquired, as Sexton Blake alighted, 'is it all right?'

'You have done well. Here is your sovereign. Is that cab yours?'

'No,' replied the man, rather surprised at the question. 'It belongs to Ticking's.'

'Well, if you wish to earn more money, drive back to your stables, leave the cab there, and meet me at this spot in half an hour.'

'Is it strite, guv'nor? Yer know, I've got to pay for this keb whether I has it or no.'

'Straight! Of course it's straight! Do you accept my offer or no'

'Well, yes guv'nor! If there's quids flying about I may as well be in the game as not. S'long then. In arf a hour I meet you 'ere.'

The cabman drove off, and Sexton Blake strolled up the street, wondering what his next step ought to be.

No. 90 was the house into which the old gentleman had gone. No. 45, which stood exactly opposite, was about as unsavoury in appearance, but it possessed an immense attraction to Sexton Blake, for on the fanlight over the door hung a card, bearing the legend, 'Apartments for Respectable Men'.

Sexton Blake knocked at the door, which was in due time answered by a lady of uncertain age, but of pronounced unclean habits.

'Watcherwant?' she snapped ungraciously.

'I see you have apartments to let? Might I see the rooms?'

'Oh, certingly, sir! Will you step in? I thought,' she added apologetically, 'that you were a hinsurance hagent. We 'ave a third-floor back, a first-floor front, a second...'

'Will you let me see your first-floor front?'

'Oh, certingly, sir!' responded the dame, who was now amiability itself.

She led the way up a dark staircase, with Sexton Blake stumbling after her. The impression that struck him most forcibly about this house was its utter darkness, its striking uncleanliness, and the odour of hash that pervaded the atmosphere.

'A very nice room,' said Sexton Blake, with an easy prevarication that did him credit. 'A very nice room indeed. Not too light, which is a good thing, for too much light is bad for the eyesight; not too airy, another advantage, for colds are complaints that I suffer greatly from.'

'Oh, certingly!, said the landlady, smiling consciously.

'And what might the rent be?' inquired our hero.

'Sevingteen shillings a week, sir.'

'That will suit me admirably. Will you allow me to become a weekly tenant, and take possession at once?

'Oh, certingly!'

'Then we may consider the matter settled. Would you tell me your name?'

'Missusarris.'

'I beg your pardon?'

'Missusarris.'

'Ah, Mrs. Harris! Well, mine is Brown—Samuel Brown. You would probably like the rent of the first week in advance—in lieu of references?'

'Oh, certingly!'

Everything being satisfactorily settled, Mr. Samuel Brown took possession of his new quarters. Whatever the room may have lacked in comfort, the window commanded an excellent view of the house over the way, and that was all that Mr. Samuel Brown desired.

He had arranged the dingy lace curtains to the best possible advantage, so that he could see without being seen, when a knock came at the door, and Missusarris thrust in her untidy head.

'Ow do you propose to manage about meals, sir?'

'Oh! Thank you, Mrs. Harris, I will take my hash—my dinner, I mean—at a restaurant. It will be more convenient to you. And that reminds me that I must go out now and send for my luggage.'

Sexton Blake passed out of the house and turned the corner of the street. Here, according to arrangement, the cabby stood awaiting him.

'You are punctual, my man, I see.'

'Yes, sir.'

'Now then, I want you to go to my chambers in Norfolk Street, Strand, and deliver this letter to the housekeeper. She will give you a bag, some clothes, and any letters that may have arrived for me. You will bring them to me at No. 45, in this street.'

The man grinned. 'It'll be a rum go to set inside a keb after having set outside one for so long.'

Sexton Blake returned to his room and to his point of vantage at the window. Nothing, however, transpired for some time, till presently when it began to grow dusk, a lamp was lit in the room that exactly faced the one in which our hero was installed. The blinds were left up, to Sexton Blake's huge delight, and, by the light of the lamp, he saw the old gentleman who had caused him so much trouble busily writing at a table.

At the same instant a cab drew up at his own door, and the ex-cabman made his appearance with a large bag, which he placed on the floor.

'Thank you, my man,' said Blake, keeping one eye on the house over the way all the time. 'I do not think I shall want you any more tonight. Here is another sovereign. That will repay you, I suppose, for the loss of your cab.'

The man accepted the coin with thanks and retired, and again Sexton Blake was left alone. Hardly had the cabman gone when the old gentleman rose and stretched his arms, as if tired. The room, in which he sat was half bedroom, half sitting-room. The old man rose up, looked at his watch, and walked towards a washbasin, removing, as he did so, the false wig and beard that adorned his head. He turned to place those articles on the table, and, as he did so, the lamplight shone full on his face.

Sexton Blake rubbed his hands in glee.

'Just as I thought! Just as I expected!' he murmured. 'My old friend Sergeant Pinniger!'

SERGEANT PINNIGER—for it was he who had led Sexton Blake such a chase—proceeded to wash himself, after which he again donned his false wig and beard, placed his hat on, and prepared to leave the room.

Not an action escaped Sexton Blake. As Pinniger left his room Blake left his, first taking up the bag which the cabman had brought. As he opened the street door he saw the upright form of the venerable Pinniger about a dozen yards ahead. He followed cautiously till they emerged into the Blackfriars Road; here Pinniger called a cab, and Blake did the same, directing the driver to keep the other cab in sight.

The two cabs drove at a leisurely pace over the bridge and up Queen Victoria Street, past the Bank and down Old Broad Street. At Liverpool Street Station they pulled up.

Pinniger made his way to the Continental booking-office and asked for a ticket. He received it and passed on.

Blake quickly made his way up to the office, and demanded of the clerk, nonchalantly:

'The same.'

The ruse succeeded, for the clerk, imagining that the two men were together, threw over a single first-class ticket to Antwerp, which Sexton Blake paid for and took.

It was then twenty minutes after eight; the train, Blake knew, started at eight-thirty. He found an empty compartment, and, calling for the guard, instructed that worthy to keep out intruders, at the same time pressing into his hand a couple of half-crowns.

'The chase has begun,' said Sexton Blake to himself, as the guard locked the door. 'I wonder where it is going to end! Luckily I have plenty of money with me—not as much as my friend Pinniger, certainly, but still enough to carry me round the world if necessary.'

At eight-thirty the train moved slowly out of the station.

'We are due at Parkstone at ten-thirty,' ruminated our hero. 'Well, I have plenty to do in the meantime. By Jove, though I wish I had had time to get a decent meal; I'm nearly famished.

The train was now dashing through the suburban stations, and Sexton Blake got up and turned his attention to the bag, which he opened. The first thing that he saw was a letter. It was from his friend at Scotland Yard, and ran as follows:

Dear Sir,

The enclosed will no doubt be useful to you. It is the portrait of the man whom you are to arrest—Lord Dallington. I am pleased to say that I am empowered to offer you a reward of one thousand pounds if you succeed in this undertaking.

With very best wishes for your success.

Yours very truly,

Francis L. Joram

'Most useful! said Sexton Blake, 'both the prospective reward and the photograph. Not a bad-looking fellow, this murderous Earl, but a nasty expression about the mouth. Well, now to work.'

He turned out the contents of the bag on to the seat of the railway carriage, and a motley collection of articles they were—wigs, beards, false noses, and clothes of all sorts and descriptions. After that he was very busy till the train drew up at Parkestone Quay.

The guard came bustling up to unlock the door and let our hero out; but on reaching the carriage he started back in astonishment. The sole occupant was a stolid-looking German with flaxen hair and beard, a pair of huge green goggles planted on his nose, who sat solemnly, puffing a huge meerschaum pipe.

'Where's the gen'lman as I locked in?' demanded the mystified guard.

'I don'd ondersdand dot vat you say,' replied the German, rising clumsily, and gathering his traps together. 'Is dis Harevitch? Dell me, my goot man, vot der vay is to der Ardvoorp boat.'

'Well, I'm blowed! ejaculated the guard, looking upon the elephantine figure of the German. 'Where on earth can that bloke I locked in have got to? He looked under the seats of the carriage, but, seeing no one there, departed, thoughtfully scratching his head.

In the meantime the German made his way on to the Antwerp boat, following closely on the footsteps of a white-haired, elderly gentleman. There were a good many people crossing that night, for the Antwerp Exhibition was still in full swing; but the German managed so well that he secured a berth immediately over that which the elderly gentleman proposed to occupy. After which, as if thoroughly satisfied with his night's work, he made his way into the saloon of the excellent steamers which the Great Eastern Company provide for the use of their passengers, and partook of an enormous supper, the sight of which caused the steward to shiver in his shoes.

The German then ascended to the deck, drew out his great pipe, which he filled and lighted, and then commenced to promenade up and down, to enjoy the splendid fresh air that blows across the North Sea. In the course of his perambulations he managed to collide with the white-haired personage in whom he had shown such an extraordinary interest when coming aboard.

'Den honderd tousand bardons! Can I haf hurd you? I am deebly grieved

'It is nothing,' said the white-haired gentleman shortly.

'Ah, I am delided! A peaudiful efening.'

'Very,' responded the other, turning on his heel as though to avoid further conversation.

'Ha, ha!' laughed the German softly to himself. 'One of these days, my dear Pinniger, you will probably have something more to say to me than that.'

He took another stroll up and down the deck and then knocked the ashes from his pipe and descended into the cabin.

The white-haired gentleman lay fast asleep in his berth; his wig was slightly awry and so, for that matter, was his beard; but he was blissfully unconscious of both facts.

The German stood contemplating him for a few moments and softly ejaculated under his breath:

'Ah! how beacefully he sleebs! Vat peaudiful innocence!' Then he too, clambered into his bunk, and soon sleep closed the eyes of Sexton Blake as it had those of Eugene Pinniger.

Antwerp is an excellent place to go to, for the two or three hours which one has to spend on the peaceful bosom of the broad Scheldt gives one ample time to get over any little disagreeable effects which the sea journey might have caused; besides which, one has leisure in which to replenish, by a hearty breakfast, the vacuum which the said sea journey generally creates in the bosom of most landsmen.

Sexton Blake managed a very tolerable breakfast and again caused the unfortunate steward to feel serious misgivings as to the capability of his larder to withstand the attack.

At ten o'clock the beautiful spire of the cathedral was sighted, and half an hour later Sexton Blake was standing on dry land once more, watching his white-haired fellow-passenger as he climbed into a voiture.

'Hôtel d'Angleterre! Hôtel des Voyageurs! Voiture!' shrieked the mob who generally collect on the Antwerp Quay.

Sexton Blake pushed his way through the throng and, calling a cab, instructed the driver in French to keep the bright yellow vehicle which the white-haired gentleman had taken well in sight, for which he would be well rewarded.

So the old game which had started in London recommenced in Antwerp, and the unconscious Pinniger was again shadowed by the relentless Sexton Blake.

Presently Pinniger's equipage drew up in front of the office of a large steamship company. Sexton Blake's coachman did the same, and our hero followed the ex-detective into the office. Here he found Pinniger in a sad plight, for Pinniger's education had not embraced foreign languages, and the only clerk who was present at the moment could speak no other language save Flemish and French. At the moment when Blake entered Pinniger was almost in despair.

Blake gave the most natural start of surprise in the world as his eyes fell upon his white-haired acquaintance of the previous evening.

'Goot grashous!' he exclaimed effusively. 'Vat a most egsdrordinary dings dat I gome here do meed you. I haf gome here do see my old friend Schmidt, who vor doo years I haf nod seen. He is nod in! Mosd sad. Bud you are in drouble, eh? I gan help you. Ah, yes! id vill be a bleasure.'

'You are very kind,' he said. 'You can help me. Unfortunately I do not speak French, and that man does not understand English.'

'Ach! I shall be delided!'

'Would you be kind enough to ask him to book me a berth on the El Dorado? That, I think, is the name of the steamer that starts tomorrow for Valparaiso.

Blake groaned inwardly. 'My goodness!' he thought. 'What a dance this fellow is going to lead me. But I'll stick to him; where he goes I go. And, at the end of it all, I shall find my Lord Dallington waiting...' Aloud he said:

'Most delided.'

He booked stateroom No. 81 on board the El Dorado for Pinniger and accepted that gentleman's thanks with the best possible grace; and then, when he had seen Pinniger out, he returned and booked stateroom No. 82 for himself, in the name of Jules Latour.

This little transaction satisfactorily completed, he drove to an hotel that was a trifle less filled than most of the others, stopping upon the way thither to make several purchases of ready-made clothing at a tailor's shop. He then partook of a hearty dinner, and ascended into the bedroom which had been allotted to him.

We will not seek to pry into the secrets of his toilet, but it will suffice to say that he ascended the stairs a portly, good-humoured- looking German and descended them another man altogether.

THE El Dorado was getting up steam to commence her long voyage. The decks were a scene of wild confusion; porters laden with luggage hurrying about seeking for their employers; passengers bidding their friends tearful adieus, or rushing about in search of some lost article of baggage; and sailors of all nationalities vainly endeavouring to reply to the questions that were hurled at them by a hundred passengers in about as many tongues.

Among all this hullabaloo two new passengers quietly crossed the gangplank and boarded the vessel.

The first was a broadly-built man, with somewhat sharp features and a profusion of reddish hair and whiskers. He was entered on the ship's books as Edward Pullen, of Manchester. He was not overburdened with luggage, for all that he possessed he carried himself, and so, inquiring of an English sailor who stood near him the way to the staterooms, he quietly descended and took possession of stateroom No. 81. The man who followed close on his heels was of a very different stamp. It was, indeed, easy to tell the nationality of Monsieur Jules Latour. He was a Frenchman to the backbone, with somewhat sallow complexion, hair closely cropped to his head, a huge black moustache with ends tightly waxed, and clothed in a tightly-fitting coat, with a very shiny hat perched jauntily on one side of his head, and an eyeglass stuck in his left eye. He was the picture of a dandy just fresh from the boulevards.

The movements of Mr. Edward Pullen of Manchester seemed to deeply interest Monsieur Jules Latour of Paris, and he never let the first-named gentleman out of his sight. When Mr. Pullen descended into the cabins, M. Latour also made the descent; when Mr. Pullen took possession of stateroom No. 81, M. Latour did like-wise with stateroom No. 82.

Jules Latour placed his luggage, which consisted of a large bag and some travelling wraps, on the floor of his cabin, and then drew out his pocket-handkerchief and mopped his brow.

'Whew!' he grumbled to himself, 'what a chase the fellow has given me! I was afraid at first that he had seen through the German disguise, and that he did not intend to resume his journey on to Valparaiso. But luckily I was mistaken. Rather a knowing dodge, that of changing his disguise at the last moment! But, my dear, good Eugene Pinniger, you don't for a moment think that you can deceive the very good eyesight that Sexton Blake is blessed with!'

After this somewhat curious speech for a Frenchman to make, Jules Latour turned to a looking-glass, and began to bestow as much attention on his personal appearance as would a society belle in her tenth season.

This done, he drew out a cigarette-case, extracted one of those pernicious articles, placed it between his lips, and (contrary to the rules of the ship) lighted it. Then, cocking his hat even more jauntily over his left eye and, drawing on a pair of light lavender kid-gloves, he strolled nonchalantly towards the dining-saloon.

'Scuse me, sir,' said the steward, who was an Englishman, as his eyes fell upon Monsieur Latour. 'Smokin' ain't allowed in 'ere, it's against the company's rules. There's a smoking-room close by, and there's another on deck, if you'll...'

'Pardon, m'sieu! I can you not onderstand.'

'I tell you you mustn't smoke...'

'Ah, yes! de smok! Of course you vill haf one. Ees it not so?'

'No! no! no! cried the steward, growing red in the face, and speaking with great distinctness. 'You—ain't—got—ter—smoke—in—'ere!'

'Zee ear! said the Frenchman, looking mystified. 'But I do not smok viz my ear!'

'Look 'ere!' commenced the now irate steward. 'I ain't a-goin' to waste...'

'Excuse me,' said a voice behind him, 'I think I can explain.'

The owner of the voice was a fair-haired, good-looking, sunburned young Englishman, dressed in a pronounced nautical style, and bearing generally about his person the suggested breeziness of the sailor.

'I ask your pardon for interfering,' he said, addressing Latour in very poor French, 'but the fact is you are breaking one of the company's rules. Smoking is allowed only in the smoking-rooms.'

'Ah! Ten sousand million much-obligeds! said Latour, promptly stamping on the offending cigarette. 'I onderstand vare leetle Engleesh, bur ze steward, he spik Engleesh atrocious!'

The Englishman laughed, and the conversation, half in bad English and half in worse French, was prolonged as the two men ascended together to the deck to catch a last sight of the old city of Antwerp as it dropped astern, as the great vessel cleaved its way through the muddy waters of the Scheldt.

Mr. Edward Pullen did not show himself very much on the voyage out. It was not that he was at all suspicious that his every movement was being shadowed, but the fact of the matter was that on the first few days out he had been a very sick man indeed—at least, so Sexton Blake (for, of course, our readers have recognized the famous detective in Jules Latour) inferred from the strange noises that he heard through the thin partitions of his stateroom.

In the meantime Sexton Blake had kept up his character as a Frenchman well, deceiving all on board, including even a couple of bona-fide French passengers, for our hero was a thorough master of the French language.

The acquaintance which he had made with the young Englishman—whose name was Lieutenant Sparkes—rapidly ripened into a warm friendship—a friendship that Sexton Blake took pains to augment as much as possible, for the position in which he stood with regard to the escaped murderer was not as satisfactory as he might have wished. It was true that, by keeping Mr. Eugene Pinniger in sight and shadowing his every movement, our hero was bound in time to come up with the real criminal for, as he was well aware, Pinniger was in the confidence of the Earl of Dallington, besides which he was the bearer of a considerable sum of money, which, of course, was intended for the Earl's use.

Sexton Blake carried in his pocket the warrant for the arrest of the fugitive Earl but the question that arose in his mind was, would he be able to execute it when the time arrived? For it was now pretty certain that the Earl had taken refuge in or near Valparaiso, and, as no extradition treaty is in existence between England and Chili, of which Valparaiso is the capital, he did not see quite what was to be done when he came at last face to face with the man of whom he was in pursuit, for from the fact that no extradition treaty was in existence, also arose the fact that his warrant would be but a worthless piece of paper when all the parties concerned met on Chilian soil. Sexton Blake had made up his mind, however, not to return to England without his prisoner, and therefore he began to set his fertile brain to work to find a way out of the difficulty.

In Lieutenant Sparkes, Sexton Blake saw the first gleam of light that was to illuminate his path. Lieutenant Sparkes was bound to Valparaiso to join his ship, HMS Firefly, which at that time was stationed off the Chilian coast.

If by some means, fair or foul, Sexton Blake could manage to lure Lord Dallington on board the English man-of-war, the arrest could be made, and the way was easy. So, with this object in view, our hero sought to ingratiate himself with the young lieutenant, whom he thought would be of assistance to him in the matter.

Thoughts to this effect were passing through Sexton Blake's mind as he lounged, in a seemingly careless manner, near the bulwarks of the vessel. The Horn had been rounded and now, day by day, they were rapidly nearing their destination.

'Well, M. Latour, and what are you thinking of?' said Lieutenant Sparkes, coming behind our hero.

'I vos tinking dat I should mooch like to 'ave von two minutes' conversation vid you.'

'With me? Oh, with pleasure! Shall we stroll up and down?'

Sexton Blake took the young sailor's arm, and, when they had reached a part of the deck where they were free from observation, he turned to his companion and said:

'Look here, Lieutenant Sparkes, you and I have been very good friends, so far. I am now going to impart a secret to you, and I want your word of honour that you will never indulge a word that I say.'

A look of blank astonishment passed across the lieutenant's face.

'Why—why!' he stammered, 'I thought you were a Frenchman, and yet you speak English when it suits you as well as I can myself!

'For the simple reason that I am as much an Englishman as you are.'

'Then what the dickens is your little game?'

'The fact of the matter is I am in disguise.'

'So I can see. But are you going to tell me,' said the lieutenant, recoiling a pace or two, 'that you are endeavouring to escape from justice?'

'Au contraire, as our friend Latour would put it,' said Sexton Blake, with a smile. 'The fact of the matter is that | am on the track of those who are trying to evade the law.'

'You are a detective?'

'I am. My name, as you may guess, is not Jules Latour, but Sexton Blake.'

'Not the Sexton Blake?' asked the young man in astonishment.

'I don't know if I am entitled to the flattering prefix the, but still, I am Sexton Blake at your service.'

'At my service!' said the young man, with a laugh. 'I rather think it is the other way about. You must want me to help you in some way, or you would probably not confide in me.'

'You are right,' said Sexton Blake. 'And now, without any further beating about the bush, I will explain the matter to you as clearly as possible, trusting implicitly in your honour to keep secret what I have told you. The perpetrator of an outrageous and horrible murder has taken refuge in the country that we are now fast approaching; his confederate is at this moment aboard this ship. In following him I am sure to light upon the man for whom I have a warrant to arrest. You understand so far?'

'Perfectly. But if, as you say, this murderer is at present in Chili, you cannot arrest him, as there English law is not recognized.'

'That is precisely the point at which I wished to arrive. I cannot arrest him on Chilian ground, but I can arrest him on board an English man-of-war.'

'Ha! And so that is why you have applied to me, Mr. Blake?'

'It is. I want you to aid me.'

'But,' said the young man thoughtfully. 'I don't quite see how I can. I am not the captain, you know, and, even if I were, I don't know that I could take such a great responsibility as to seize by force anyone who is at the present, at any rate, under the protection of the Chilian Republic.'

'You are right, perhaps, bur still, all that I ask you personally to do in this matter is to acquaint your captain with the facts of the case, and give me an introduction to him when we arrive at Valparaiso.'

'I will most assuredly do that with the greatest pleasure. You will find my captain a jolly good fellow, but...' The lieutenant shook his head impressively.

'No buts,' said Sexton Blake smiling. 'I have succeeded in harder cases than this one, and I've never confessed myself beaten by a criminal yet, and I hope I never shall.'

TWO days before the arrival of the El Dorado at Valparaiso, Mr. Edward Pullen made his appearance on deck, for almost the first time, indeed, since the vessel had left Antwerp.

He appeared to be labouring under great excitement, which he vainly strove to conceal; but the sharp eyes of Sexton Blake, which had been quick enough to pierce through the disguise which Sergeant Pinniger had assumed, soon detected the anxiety which the other could not avoid showing.

At last, late on the night of 4 November, Valparaiso was in sight, and the passengers began to collect their luggage preparatory to disembarking.

Messrs Pullen and Latour were not overburdened with luggage, and the former was one of the first to cross the gangplank and put his foot on dry land. But, if Mr. Pullen was the first, M. Latour was certainly a very good second.

Sergeant Eugene Pinniger—for it is now useless to call that gentleman by his assumed name—gazed about him with the distracted air that Englishmen generally assume when first landing on a foreign shore. If he had felt himself at sea when at Antwerp he was doubly so at Valparaiso.

Sexton Blake, from a point of vantage which he had secured, kept his eyes upon the unhappy-looking sergeant, and suddenly he saw the worried look that he wore give way to a smile of relief, as he advanced, with outstretched hand, to an individual who had been loitering about the quay.

Sexton Blake started violently. Never for a moment had he doubted that, by following Pinniger, he would eventually run the murderer to earth; but now that he actually stood face to face with the man whose photograph he carried in his pocket, it came almost as a surprise to him.

There could be no doubt that the man in whose company Pinniger was now rapidly walking was Lord Dallington. Sexton Blake cautiously produced the photograph of the murderer from his pocket and, for about the hundredth time, studied it minutely. Yes, the features of the photograph tallied exactly with the face of the stranger of whom Sexton Blake had caught a fleeting glance. Both bore the same aristocratic cast of countenance; the same cruel-looking, thin-lipped mouth, nearly hidden by the same luxuriant moustache. The curiously-cunning expression which lurked in the narrow, deep-set eyes, and which was so admirably portrayed in the photograph, was not missing in the original, as Sexton Blake mentally and unhesitatingly pronounced the stranger to be.

Meanwhile the two men in advance were walking at a brisk pace towards the town, and Sexton Blake was compelled to observe much circumspection in striving to keep them in sight and yet not be seen by them, for, though he still wore the dress and sustained the character of Jules Latour, he was anxious not to arouse the suspicion of the men he was tracking.

At last the two turned into a small hotel and disappeared within its doors. Sexton Blake allowed them a few minutes' grace, and then he, too, entered the diminutive place.

'Can I have a room here?' he demanded of a rosy-cheeked, black-eyed damsel, who was complacently lolling in a large basket-chair, and smoking a cigarette.

The maiden shook her head and smiled, disclosing a row of pearly teeth.

Sexton Blake repeated his question in execrable Spanish.

'Yes, señor, we have rooms. Visitors, you know, are not too plentiful about now. The first floor is occupied by a mine owner and his wife. Caramba! But they have a lot of money—more money than wit, I should say, or they wouldn't be here. Then there's one of those Englishmen; he's taken two rooms on the next floor. But, as there are three rooms, one is still vacant.'

'Good! said Sexton Blake. 'Would you be kind enough to show me the room?'

'Ah? said the young lady, indolently puffing a cloud from between her ruby lips. 'It is too hot to run up and down stairs. Go up by yourself, my friend; you will find the room—it is No. 7, on the second floor. Don't go into No. 5 or No. 6 or the Englishman will be after you. He is so particular, you know. A nice dance I have had for the past two weeks, since he has been here!'

Sexton Blake picked his way gingerly up the narrow, dark staircase till he came to the second floor. Here he had no difficulty in ascertaining which was No. 7, for the door stood wide open, while the doors of Nos. 5 and 6 were tightly closed.

Very noiselessly and very cautiously he advanced into No. 7; and then he stood still to listen, for he could hear that a conversation was being carried on in the adjacent room, and the walls, which were but rudely built of lath and plaster, did not deaden the sound much.

He approached nearer to the wall and listened intently. As he did so he started, for he heard his own name mentioned, in Pinniger's voice.

'Yes,' the ex-detective was saying, 'you have no one to thank for all this but a rascally fellow who calls himself Sexton Blake. He found a bottle or something of the sort at sea, which contained a declaration written by the late Harold Estcourt to the effect that you had set the Valentine on fire. Well, instead of coming to you and being bought off...'

'As you did, my good Eugene,' broke in a voice that was unfamiliar to Sexton Blake.

'Exactly! As I did,' continued Pinniger, 'he must go and put it into the hands of the authorities. Well, the warrant for your arrest was made out, and I was entrusted to execute it; you received my cipher telegram, and, of course, when I arrived at Dallington you had gone. I got into some disgrace, I can tell you, over that little job, although nobody ever guessed the real facts of the case; but the chief said I had bungled somehow. However, I didn't care much for that, for I received your letter containing the instructions about drawing the money and joining you out here; and here I am, you see—money and all.'

'Good! But how about the detective fellow? What did you say his name was?'

'Oh, Sexton Blake! I expect he is still grubbing about down in Warwickshire, searching for clues.'

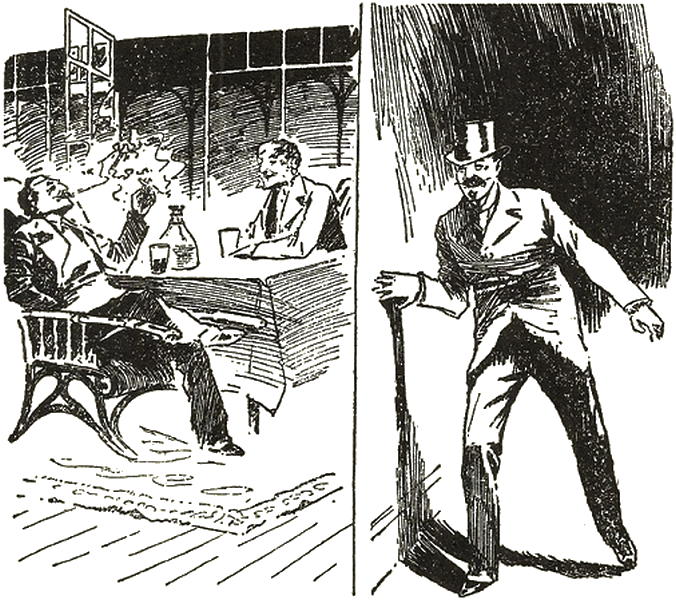

Both men laughed heartily, and Sexton Blake, on his side of the partition, silently joined in the merriment.

Both men laughed heartily at Sexton Blake's expense,

little dreaming that the detective, disguised as

Jules Latour, was listening in the adjoining room.