RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

IN a lonely bungalow, perched high amongst the Nilgherry Mountains, in Hindustan, Gerald Everton lay a-dying. Dying, and he knew it; knew it, and was resigned. Misfortunes had fallen so thick and heavy of late, that he would welcome death as a happy release from a world of care and trouble.

Going out to India in his youth, some five and twenty years before, he had remained there ever since, engaged in commercial pursuits; and for many years fortune had been kind to him. He had married early, and, happily, and had one child, a sturdy boy. His business prospered, wealth flowed in upon him, and Gerald Everton was thinking of retiring, and returning home with his family to enjoy his hard won wealth, when blow after blow fell upon him, changing all brightness into deepest gloom.

Three years before, he lost his wife; a year later a bank, in which he had invested most of his fortune, stopped payment, hopelessly insolvent. A year ago, the almost ruined merchant was seized with a dull, wasting sickness, which the doctors could not understand, much less banish; but they ordered him up to the purer air of the hill country, and Gerald Everton retired into the Nilgherries, accompanied by his son Rawal.

Alas! misfortune followed him. A month previously, Rawal Everton, when out shooting with Shib Dal Hamid, one of his father's attendants, met with a fatal accident.

Wife, child, and fortune; all were gone. The sickness also increased, and Gerald Everton felt that his own end was nigh.

Quietly he closed his eyes, waiting for the call.

Then, the curtains in the doorway were drawn aside in a furtive manner, and a man glided stealthily into the room.

The new-comer was a young man of two-and-twenty, swarthy in complexion; his features heavy and forbidding in their expression.

Stepping noiselessly across the polished floor, he reached the bedside, and gazed down on the dying man, whose spirit seemed already fled.

"Ah! Gone at last!" muttered the youth callously; "quite time, too. Had he lingered much longer I should have felt inclined to expedite his decease. Now to make my own arrangements ere I announce the death." And, taking a bunch of keys from a basket on the table, he unlocked Gerald Everton's desk, end began rummaging through his private papers.

The rustle aroused the dying man, who slowly raised himself on his elbow, and, in a dull, hollow voice, whispered:

"What are you doing at my desk? Why meddle with my private papers? Would you rob me, you base, ungrateful coward? Too late, now; I see it all. What a viper I have nourished! I believe my very sickness is due to you. Why, you were alone with my poor boy when he met his death. Was that your doing, also? But I will expose you. I have yet a little time to live, and, thank Heaven, still have some faithful servants within call."

"So! you will have it, will you?" cried the Indian, pulling out at arm's length a gong that his master was striving to reach. Then, going swiftly to a table, on which were a number of medicine bottles, the villain filled a wine-glass with a clear liquid, and, returning to the bedside, said sharply:

"Here! drink this! It is but a sedative; yet it will glide you unconsciously into the next world. You won't have it!" he continued, as the dying man made a feeble resistance; "nay, but you must." And forcing open his victim's mouth, the wretch poured the contents of the glass down his throat.

The death of Gerald Everton was announced an hour later.

Almost An "Electrocution" - An Unexpected Meeting.

ON a bright, clear, summer morning, some ten years ago, Sexton Blake, the famous investigator, left his chambers at Norfolk House, and strode away down the street.

Leaving the busy, jostling, roaring Strand, he turned down a thoroughfare leading to the Thames Embankment.

This street was quiet enough, bounded on either hand by residential mansions, let in flats, and at that early hour Sexton Blake had the thoroughfare almost to himself.

The only person in view was another wayfarer—a well-dressed, gentlemanly young fellow—who entered the street at the bottom, and came up the hill towards Blake; then, some twenty yards behind the young gentleman, appeared a middle-aged man, fussing and hurrying along as if late for business.

Although Sexton Blake was engaged with his own thoughts, his eyes were, as usual, keenly roving about; his mind unconsciously noting what met their gaze. The leading figure seemed familiar; something in the gait and carriage of the youth struck a chord of memory, and the detective found himself vaguely wondering who was the youth; when and where he had seen him before.

As Blake gazed and pondered, the young gentleman advanced with springing step, lightly swinging a cane, seemingly humming a tune; then, suddenly, the gay young fellow appeared struck by a bolt from the blue.

Without any warning, without any apparent cause, the wayfarer reeled, staggered like a drunken man, threw up his arms as if in a wild attempt to clutch something; then, with a cry, fell in a heap on the pavement.

"Poor lad! he has had a fit of some sort!" muttered Sexton Blake, starting forward to render aid.

But another was before him, the gentleman behind the stricken one was nearer, and he also ran to succour.

The stranger reached the prostrate figure, while Sexton Blake was still about twenty yards away; then, what was Blake's amazement to see the second man act exactly as had the first.

On arriving at the spot, he, too, reeled and staggered, then fell to the ground, clutching frantically at his companion in misfortune, as he reached the pavement.

Sexton Blake stayed his own headlong rush. Here was something mysterious; he must use his head before his legs. Swiftly, yet cautiously, he approached the fallen pair; then made a brief halt a few yards away.

Both figures were motionless, save for a convulsive twitching and trembling of the limbs; the eyes of the youth were closed; those of the man were open, the eyeballs rolling wildly. What was the cause of the catastrophe that had suddenly overwhelmed these two; the one in the spring-tide of youth and health, the other a strong man in his prime? There seamed nothing to account for it, The street was clean and bare, all around open and clear.

Quick to observe, trained to arrive at conclusions, Sexton Blake gazed keenly and inquiringly about, and almost immediately discovered the nature of the unseen force that laid low these two, as swiftly and suddenly as a lightning stroke.

Into the street, opposite to where the men lay, was let a square iron-plate, bearing the name of an electric company. Between it and the mansion, on the inner side of the pavement the flagstones were slightly arched, and over this raised portion the bodies lay.

It was clear enough now. The electric wires, supplying the mansion with light and motive power, passed from the street mains through a hollow way under the pavement, and in this the tunnel a leakage had occurred, charging the flagstones above and around with electricity. The paving-stones were turned into a gigantic electric battery, Any mortal thing stepping on that spot would be struck down without chance of retreat or escape.

Yet something must be done for the two victims, and that instantly; both were still in life; but who could tell how long their vitality would resist the electric current. To attempt their aid was probably to suffer with them; the danger seemed the greater, as its extent was unknown. Still, Sexton Blake neither hesitated nor delayed.

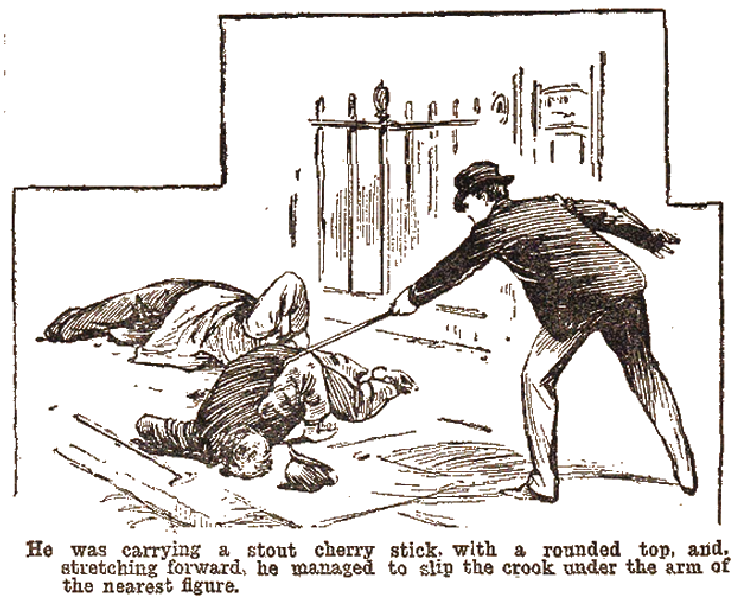

Keenly he noted the plug-hole in the street: carefully he followed the course of the submarine mines; then, cautiously approached, as if treading on thin ice, to the assistance of skaters who had fallen through. He went as near as he could; so close that he felt his right leg tingling under the electric influence. He was carrying a stout cherry stick, with a rounded top, and, stretching forward, he managed to slip the crook under the arm of the figure nearest him, that of the youth, and draw it so closes that he could grip it.

As he caught the body, the electricity ran through his own frame with a shock that almost unnerved him; but, summoning all his energies for a supreme effort, he dragged the youth from the fatal spot. The other one, the man whom he had first gone to aid, had, when he fell, grasped the youth by the leg, and, retaining his hold as convulsively as a drowning man, he, in turn, was dragged off a little way, sufficiently far for his rescuer to approach, and haul him off to a place of safety.

With the celerity with which a crowd always gathers in London when anything unusual occurs, a ring of curious spectators was formed; the police (who, despite the worn-out, and lying adage, are usually on the spot when they are wanted) were equally prompt. The dangerous ground was guarded, and the two sufferers, still unconscious, were carried into a chemist's shop in the neighbourhood; their rescuer being one of their bearers.

Two medical men were quickly in attendance; the sufferers were laid on a couple of long tables, and the doctors began their efforts at resuscitation.

Whether, owing to his more mature frame, or to his shock being less severe, the elder man was the first to recover consciousness. By-and-by, he sat up on the table, rubbing his blinking eyes, and gazing around in bewilderment; while those about him endeavoured to explain to him the nature and cause of his accident. Then, after an interval, he got off the table, and stamped about somewhat totteringly, declaring himself full of pricking pins and needles.

Although the electric effects gradually left his body, they seemed to retain a most irritating effect upon his temper, and, in the end, the man went off in a fury, vowing revenge against the electric company, whom he declared he would mulet in swinging damages for their "tricks upon travellers;" and, in his anger, he quite overlooked his fellow sufferer, and showed no interest in the youth he had previously been so ready to assist.

Meantime, those in attendance on the other victim, grew grave and anxious, as for some time the case resisted all attempts at recovery, and life and death seemed trembling in the balance.

At length the unremitting effects were successful, and, by-and-by, the youth was sitting weakly in an easy-chair, endeavouring to comprehend what had befallen him.

During the lad's resuscitation, Sexton Blake had examined him keenly. He thought the figure familiar when he first saw it afar off, and, on scrutinising the features, his impression was deepened. He had seen the youth somewhere: he had the likeness in his mental portrait gallery; but could not give it a name; could not, for long, identify the subject. Suddenly he had it; caught it like a flash, and as the lad had now subsided into comparative calmness, Blake strode up to the chair, and, extending his hand, said:

"Harry Everton; if I am not mistaken?"

"That's my name," returned the other slowly, gazing blankly into the face of his interrogator, as he took the proffered hand; "but—but—you have the advantage of me, sir!"

"Why, Everton Major," said Sexton Blake, smiling; "have you already forgotten your old school days? Surely they are not so far behind?"

"Why! it's Sexton Blake!" cried the lad, with a gasp. "Old 'Bravo! Blake,' as we used to call you. What a dolt I was not to recognise you at first. It's not the first time by a good many that you have pulled me out of a hole. But, can it be," continued Everton, pressing the hand of the other as if to assure himself of its reality; "is this really old 'Bravo! Blake'?"

"'Bravo! Blake,' it is, Everton Major! Now, as you seem well enough to be removed, but are still weak and shaken, we will take a cab to my chambers, where you can rest, and at the same time we will pick up the threads since the jolly old days at Ashleigh.

Explanation - Invitation And Acceptance -

A Journey To Everton Towers, And An Awful Reception.

AS the "London gondola" bowls along, we may have time for a word or two in explanation. Fortunately, but little comment is required, as the journey is only a short one.

Sexton Blake had been educated at the Public School of Ashleigh, and, during his later years of residence there, Harry Everton had also been a pupil, with his younger brother Frank. The two Evertons (known as Major and Minor, though there was only a couple of years between them) had been but little fellows during the time of Sexton Blake, the latter being generally regarded at that period as the hero of the school, held in greater estimation, almost in greater awe by the small fry, than the Head Master himself, Since Blake left, he had neither seen nor heard of the Evertons. Harry, from a boy of eleven, had shot up into a fine, manly young fellow of about twenty, so that Sexton Blake might be well excused for his failure to instantly identify him again, In Blake himself, the change was almost as great. The lad of eighteen, differs much from the man of seven-and-twenty; but once the chord of memory was touched by the mention of his school days, the thoughts of Everton Major flashed back to Ashleigh, and to the hero of his boyhood days, "Old 'Bravo! Blake.'"

"Sit down there and rest, Everton," said Blake, wheeling his easiest easy-chair into a comfortable position. "Now you must have a glass of sherry and a biscuit to strengthen you: afterwards, a cigar may soothe your excited nerves, You will find these 'weeds' pretty good,' he concluded, adding his cigar-box to the refreshment. "Now, tell me all about you and yours!"

Everton had not much to relate. He had left Ashleigh two years before, and had since resided with his father at Everton Towers, the centre of a large residential estate that had been in the family for many generations. Harry desired to travel: and, while his father was willing enough to allow his sons to see something of foreign parts, he wished Harry to wait until the next brother, Frank, had finished his schooling, when they that time led now arrived. and the two youths were eagerly looking forward to their foreign tour.

"We mean to have a jolly good time, Blake." concluded Harry, "and see all that is to be seen; but we do not start for a week or two yet. Meantime, we are all living at the Towers: I only ran up to London for the day—came up early. Frank is at home with father, also my youngest brother, Charlie; but he is only a kid, a schoolboy, you know— 'Everton Tertius,' he is called at Ashleigh. By the way, my cousin is staying at the Towers also."

"Who is your cousin, Harry? I never heard you speak of any such relation!"

"Good reason for that. Blake: I did not know him myself until quite lately. He is Rawal Everton; the son of my father's younger brother; so called, I believe, because he was born at Rawal-Pindeh, in the Panjaub. He has spent all his life in India; but on the death of his father last year, ha came to England, and has made our home his home, pretty well ever since."

"You don't speak very cordially, Harry! Don't you like your cousin?"

"Frankly, Blake, I do not! I can't tell why, either: He is very suave and polite, too much so by half; but I can't trust him, somehow. He goes about like a cat, always purring and friendly; yet always watching and spying for something. But there, now!" cried the youth, interrupting himself, "that's neither fair nor generous. I know nothing against my cousin; he is far cleverer, and, probably, a much better fellow than myself—only—only—in the words of the old-rhyme: 'I do not like you, Doctor Fell, the reason why I cannot tell; but this I know full well, I do not like you, Doctor Fell!'"

"I'll tell you what, Blake!" burst out the young fellow, after a pause; "you must run down with me to Everton Towers, and spend a week or two with us; then you can see things for yourself. We will make you comfortable, never fear! Of course, it is not the shooting season; but we can always knock over a few rabbits, if there is nothing better to do. Do come! it will be very jolly. That is, if you can spare the time."

"I could spare the time easily enough," replied the other smiling. "In fact, I was meditating a little holiday when I met you; only doubtful as to where I should spend it. But, Harry, I can't take you by storm in such an unceremonious fashion. What would your parents say?"

"I have only one parent, Blake; mother died some years ago, you know. Father is the kindest, the best, the jolliest old fellow breathing, not excepting even yourself, 'Bravo! Blake.' Any guests I bring are always welcome: you, especially, he will be glad to see, as he has often heard of you from Frank and me. Besides, when I tell him how you saved my life to-day, he won't rest till he has thanked you himself!"

"Poof! Saved your life! Don't talk rubbish, Harry. Why, I only fished you out of that electric current with the crook of my cherry-stick, like a Scotch gillie landing a hooked salmon with his gaff. By the way, you say this Rawal Everton is the only son of your father's younger brother. I suppose, after your family, he is next heir, as the Everton estates are entailed, I believe?"

"Yes: that's right enough, Blake; but Rawal is far too sensible to count upon any such remote contingency as that. Why, the dear old dad will live, I hope, for many long years yet, and, after him, come my two brothers and myself. But you don't put me off like that, Blake! Stick to the point, man! I say you must return with me to Everton Towers to-night, and come you shall! You have owned you are open for a holiday, so I will listen to no excuses. I will send a telegram to announce your visit; now, go and pack up, like the good fellow you always were."

Sexton Blake did not require very much pressing. He packed up his things, taking with him even his camera, as he was a skilful amateur photographer, and the country scenes promised plenty of subjects; and the afternoon Great Southern express whirled the two friends down to Alcombe Junction, the nearest station to Everton Towers.

The day, clear and bright, when they started, became dull and cloudy during the journey, and on their arrival at the junction, dark clouds were hanging in heavy lowering masses overhead; the air was still and stifling, with every indication of an impending thunderstorm.

"By George! Harry," said Blake, "electricity seems to cling to you; we shall have thunder and lightning soon!"

"Don't much matter, Blake! here is the carriage, jump in quick; we have only four miles to drive, and may reach home ere it comes on. "

In this, however, the travellers were disappointed. The storm burst upon them 'ere the carriage had covered a mile. The lightning blazed and flashed around, till they almost fancied they heard the hiss of the bolts between the deafening reverberations of the thunder claps, With difficulty the coachman restrained the terrified horses, as they reared and plunged at every peal, swerved and shied at every lurid flash; and a score of times the carnage Was within-an ace of being overturned into the ditch on the one side of the road, or rammed into the quickset hedge on the other.

Fortunately, the fury of the storm was soon spent; the rain came rushing down in a living cataract; a Niagara of whirling water, that seemed at once to extinguish the lightning and still the thunder. Then the deluge, too, passed away, its work done; and when the carriage entered the extensive chase, and rolled up the long avenue leading to Everton Towers, the sun had burst out again; and was shining as brightly as-at the start of the journey.

On drawing up at the door, however, it was evident that something untoward had occurred within the mansion. Servants were flitting about, but none came forward to tender assistance, and Harry was looking around in some wonderment, a little annoyed at the neglect: when a young fellow of eighteen rushed out, in whom Sexton Blake at once recognised Frank Everton—"Everton Minor"—hatless and breathless, his face white and scared, the boy rushed up to his brother, crying out:

"Oh, Harry! Harry! What ever shall we do? Father has been struck by the lightning! He is dead!"

Was It The Act Of Man?

WELL was it for the Everton household that Harry had chanced to bring down Sexton Blake with him.

"Father has been struck by the lightning! He is dead!" The words themselves seemed to exercise a blighting, numbing effect on the young fellow addressed, who gazed around in startled bewilderment, and appeared as if he were about to fall, when Blake, placing his hand within Harry's arm, led him into the hall, whispering: "Bear up, Harry Everton; remember, everything depends upon you; you now are the head of the house! Play the man, Harry; I will help you all I can!"

Indoors, everything was in confusion. Everyone seemed distracted, the old housekeeper, the most helpless of all; and, Sexton Blake, upon an acquiescing nod from his young friend, issued some orders. He sent for the doctor. He also sent a telegram to Sir George Chemworth, Harry's maternal uncle, announcing the sad event, and begging the presence of the baronet as quickly as possible; then, with Harry and Frank (Charlie, a boy of eleven, was crying hysterically in the arms of the housekeeper), Sexton Blake went into the death-chamber.

Squire Everton had been in his study; a little snuggery on the ground floor, with French windows opening out to the lawn. One of these windows was wide open now, and Mr. Everton had been standing by it, watching the storm when he was struck.

There lay the body of the poor squire on the carpet, close by the open window, huddled in an unnatural lifeless heap, as if he had suddenly collapsed when standing up. The face was very distressing, the features being distorted by a startled, agonising expression, the eyes, wildly distended, seeming about to leap from their sockets, with a strange, questioning look in their glare.

Although the window was wide open, and the ground outside was saturated with moisture; although, too, the rain had beat against the windows, and large drops still hung on the panes outside, strangely enough, none had entered the room; and this circumstance first aroused in Sexton Blake, the professional instinct that caused him to investigate the matter, and ultimately to trace out a foul crime, none other than murder.

Quietly issuing his commands, Blake had the body removed to a more seemly resting-place, the dead squire's bed in his own chamber; there to await the arrival of the doctor.

"Where is your cousin Rawal? I thought you said he was staying here?" inquired Blake of Harry, when things were so far settled.

"Ah! Yes! Where is Rawal, Frank?" said Harry, passing the inquiry to his brother.

"Don't know! Haven't seen him since some time before the storm!" replied Frank.

On search being made, Rawal was discovered in his own room, the shutters of which he had tightly closed. He appeared in an extremity of fright, still; and explained that, as he never could bear thunderstorms, he had shut himself up in his room when the present one commenced: and had remained there ever since. He appeared much upset on hearing of the death of his uncle: but to Sexton Blake, accustomed to notice keenly, and reason promptly, the youth's concern seemed overdone, his surprise assumed.

Sexton Blake felt an instinctive distrust of this "cousin Rawal" directly he saw him. The fellow seemed to be acting a part—over-acting it, so far as Blake was concerned—although the others, less observant, noticed nothing amiss.

Presently the doctor arrived in hot haste, and, after he had made his examination, Sexton Blake, with the two elder sons, went into the study to hear his report; Rawal saying he was going to his bedroom to lie down for a bit, and poor little Charlie again betaking himself to the sympathetic arms of the housekeeper.

"An accident! The visitation of God!" was the doctor's report. "My poor friend was instantaneously killed while watching the lightning by the open window!" he concluded.

"You are quite certain on these points, Dr. Clodman?" queried Blake.

"Only too certain, sir! There is no possible room for doubt!" returned the medico stiffly.

"Then," urged the pertinacious inquirer, "if he was killed by lightning while standing here by the open window, how comes it that the rain did not enter the room? Look for yourself, it is perfectly dry within. See! the panes are wet still, but only on the outside. Further, it seems strange that there is no trace of electricity, except on the body. In such cases the electric fluid does not suddenly stop. It usually flashes downwards into the earth, leaving traces of its passage. How do you account for these things?"

The doctor shrugged his shoulders, and did not attempt it.

"Your father died by accident; was struck down by lightning," he said turning to Harry. "I stake my professional reputation on that!"

Blake was not convinced, however; far from it—and, for his own satisfaction, when he got Harry alone—he made a very peculiar request.

"You know, I have my camera with me, Harry," he said. "Now I want to take a photograph of your father's features as they are now. Will you allow me?"

"You are a queer fellow, 'Bravo! Blake,'" replied Harry, his mind reverting to his schooldays; "but do as you like. Of course I can trust you."

There was still sufficient light for the operation; and, for the object in view, the sooner it was concluded the better. Sexton Blake took his camera and appliances into the dead man's room, and locked the door. He drew up the blinds and lightened the darkened chamber, then proceeded with his operations.

The dead man was lying on his bed, fully dressed, exactly as he had been when he received his death-stroke, his face still wearing its agonized expression, his eyes still full of startled, questioning wildness, and it soon became apparent that it was of these latter features alone that the investigator desired a photograph.

He directed one of the expiring sun-rays full into the eyes of the dead man; then, inserting one of his smallest, most sensitive plates, adjusted the camera within a foot of the pupils, took a couple of negatives, then left the room with his paraphernalia, none, save Harry Everton, being any the wiser regarding his proceedings.

Early next morning Sir George Chemworth arrived in answer to the telegram despatched to him the previous day. Sexton Blake saw nothing of the baronet on his arrival, being busily engaged in his own room all the forenoon; but, towards midday, he requested Sir George and Harry Everton to meet him in the study, and there the three assembled.

"I have sought you, Sir George," began Blake, after being introduced, "in order to lay before you a very serious matter that has come under my notice; and I have also asked Harry to be present, as he is now the head of this household. I am a detective, Sir George; you may, perhaps, have heard of me professionally?"

"What Englishman has not heard of Sexton Blake, Detective and Investigator?" replied the baronet courteously.

"Although I came here simply as a guest, as an old friend on a private visit," resumed Blake, "still I cannot leave my professional instincts behind me—cannot avoid seeing what happens around me, and making my own deductions from what I observe."

"Now, Sir George, Mr. Everton died in this room yesterday. His body was found here, on this very spot, close by the open window, and Dr. Clodman has certified that the death was caused by lightning. Now, as I have already pointed out, while undoubtedly a violent thunderstorm passed over the neighbourhood-at that time, the lightning came before the rain; and had the fluid entered through the open window, the rain that followed must have deluged the room. I also remarked that there were no traces of the lightning stroke anywhere else. That appeared strange to me, and caused me to look further."

"Now, remember, the Squire was supposed to be alone. No one saw the fatal shock. Rawal Everton was said to be hiding terrified in his bedroom, and all the other members of the household were elsewhere.

The face of the dead man attracted my attention, especially the eyes. Now, sir, as you are doubtless aware, when any man is killed by a sudden, violent shock, very frequently the last scene he looks upon on earth is imprinted—photographed, as it were—on the retina of the eye, and there the impression remains for some time.

"Very well, bearing this in mind, I resolved to try an experiment, and, on obtaining permission from Harry, I took a photograph of the eyes of the dead man. The negative was, of course, very minute, but I have enlarged it to the size of a cabinet photograph; and here" (presenting a card) "is the result. Do you recognise it?"

The baronet took the card, scrutinised it; then said, with a puzzled air:

"Why, it's Rawal Everton to the life! He is standing with his hand on some strange-looking machine. There must be some mistake here!"

"No mistake, sir; it is Rawal Everton!" asserted the investigator gravely; "science does not bear false witness. Now, think what it means. Rawal Everton was supposed to be in his own room at the time; he professed to know nothing of the matter till it was told him; yet Rawal Everton was standing by his uncle when the poor Squire was struck down. The figure of his nephew was the last thing seen by Mr. Everton ere he was hurled into eternity. Still further, that 'strange-looking machine,' as you call it, is a powerful electric battery. I have ascertained that Rawal possesses such an instrument. Still more, Rawal was seen by one of the servants stealing out of this room with that battery in his arms after the rain had ceased. Mr. Everton undoubtedly died from the effects of an electric shock. Lightning would do it, but so would an electric battery."

During the narration Sir George had listened, at first with polite interest, then he grew concerned; and towards the close a horrified expression crept over his face. He grew white and ghastly, and for a time was silent, seemingly over-powered; then he whispered hoarsely:

"What! do you mean, man, that points to cold-blooded, premeditated murder? If your suspicions are correct, Rawal Everton murdered his uncle!"

"I simply lay facts before you; you can draw your own deductions and take your own course!" replied the investigator coldly.

"No, no; it cannot be! We must not even think of it!" said the baronet hurriedly, striving to recover his self-possession. "I would not have it true for worlds! Things are bad enough as they are, but such a crime added to such a catastrophe would be simply awful! No, no; we cannot have it! For the sake of the family name and honour, we must never breathe such a suspicion! Dr. Clodman has certified that my brother-in- law died from a stroke of lightning; so let it be, in Heaven's name!"

"Is that your opinion also, Harry?" inquired Blake.

"Oh, I am so shocked, so bewildered, I cannot express any opinion! But Rawal could never have done a thing like that! There must be some other explanation! Yet my uncle is right; why seek any further solution, beyond the doctor's certificate: to go beyond that would open up terrible possibilities? Not a living soul would be benefited by further investigation. Pray let it drop!"

"Certainly!" replied Blake. "The matter is entirely in your hands. You say 'let it drop,' so I will go no further, although I deemed it only my duty to lay the facts before you. But, remember this, and you, Sir George, pray note the fact also that, whereas yesterday there were four lives between Rawal Everton and the succession of the Everton estate, to-day there are but three. See that those three be not further reduced. Now I have done with the matter, unless subsequent occurrences cause it to crop up again. I will not destroy this photograph, but will keep it in a secret, secure place. Who knows but it may yet be wanted; if so, it shall be forthcoming."

Change Of Scene - Treachery -

A Desperate Ride - The Deepsuck Moss.

BLAKE found it hard to preserve his ordinary demeanour towards Rawal, although the others treated him exactly as before, and seemed to have completely exonerated him in their own minds from all suspicion; but Rawal himself made things easier by announcing that business called him away to London, where he should remain until the date of the funeral.

The interment took place in due course, and, on the will being read, it was found to be dated long ago. Harry, of course, came into the estate, and suitable provision was made for the two younger sons. Sir George Chemworth was appointed their guardian until each came of age. There was no mention whatever of Rawal, who, of course, had been in India when the deed was executed.

When the formalities were completed the baronet took Sexton Blake aside, and informed him that, in order to get away from unpleasant associations for a time, he had taken a small sea-side estate in Scotland; Clochard, on the Argyleshire coast of the Firth of Clyde; that he was about to remove there with the three Evertons; and that Rawal also was to be of the party. The baronet then begged Mr. Blake to join them, not only because his visit to the Towers had been disturbed in such a melancholy way, but also as, despite all his wishes to believe the contrary, Sir George could not altogether dismiss the suspicions of Rawal from his mind, and would feel easier if the detective were by him; and 'Bravo! Blake,' being himself rather uneasy on the subject, accepted the invitation, and resolved to see the matter out.

The experiment of Sir George seemed to be successful. He desired, by transplanting his nephews to fresh scenes and new surroundings, to efface the memory of the tragic death of their father. In the bright springtime of youth wounds, whether bodily or mental, are quickly healed when the proper remedy is applied; and ere they had long been established at Clochard, at least the younger members had pretty well forgotten the pain of the past in planning the pleasures of the future.

"What's all that row about in front?" called out Charlie at breakfast, the third morning of their arrival, as he ran to the window to look out. "Why, uncle," he shouted, "it's the horses you ordered for us! What a lot they have sent! There are six of them for us to choose from. Come along and let us look them over."

It was as the boy had said. Sir George, wishing to temporarily replenish the stables, had ordered a local dealer to send in some cattle for inspection, and there they were.

Of course the breakfast-table was deserted, and all went out to examine the steeds.

Six there were, mostly small, wiry animals, without saddle or bridle, only confined by rope halters, the only exception being the horse which had been ridden by the dealer himself, that animal being a tall, lengthy, powerful brute, much superior to the ponies in the mob.

Sir George and Sexton Blake stepped up to the dealer, who was standing with the rems over his arm, and entered into conversation regarding the merits of his stock, while the others, boylike, drifted off to examine the steeds for themselves.

"That's a nice pony, Charlie," said Rawal, pointing to one of the animals—a light bay that rather belied the encomiums, as any connoisseur in horseflesh could have told, by the shifty restlessness of the brute, its ears wickedly laid back, its eyes glancing nervously, that it possessed a temper of its own. "Too spirited for you, though, Charlie. You could not sit him," continued Rawal.

"Couldn't I just! Think I can't ride?" cried the boy.

"You couldn't ride that beast, anyway!" was the taunting answer.

"Here, I'll soon show you! I will ride him round the ring like a circus!" cried Charlie, snatching the halter from the groom who held it. "Hi! give me a leg up!"

"Have a care, young master!' expostulated the groom; "that horse is not fit for you. He has a temper, and needs a man to ride him!"

The opposition only rendered the boy the more determined. He clutched the mane, crooked his leg, and commanded the man to give him a lift.

"Very well, young sir, if so as you will have it; but be very careful not to rouse the fiend in the beast," was the man's reply, as he hoisted the boy on to the horse's bare back.

None saw Rawal draw out his penknife, and open one of the small blades; none observed him thrust the steel deep into the horse's flank; but all heard the terrible, neighing screech that the brute gave on feeling the prod, and all started in dismay as the steed arched its back, and gave a buck-jump that caused Charlie to throw his arms round its neck, and hang on for dear life; and, no sooner had its hoofs touched the ground again than it bounded off, and shot away like an arrow, Charlie clinging like a burr to its back.

While others were shouting and yelling, issuing commands, suggestions, and entreaties, Sexton Blake snatched the reins from the dealer, swung himself into the saddle of the waiting steed, and, with a couple of vicious digs in the ribs, sent the big horse flying after the fugitive at a pace as breakneck as the other.

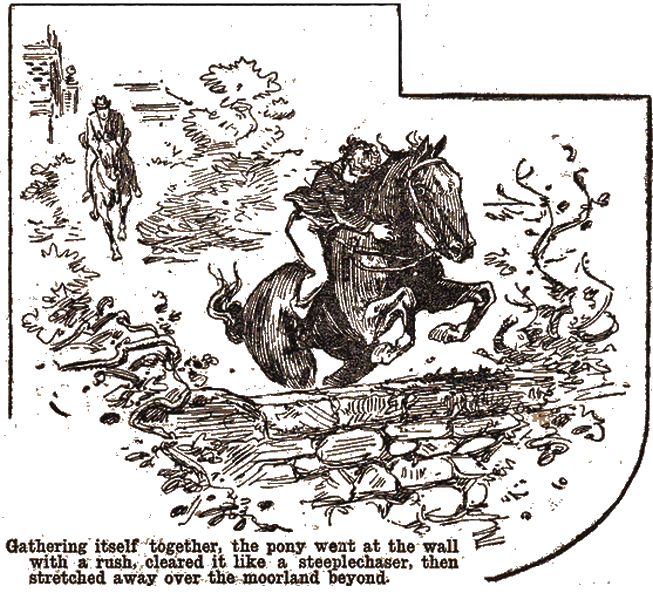

Down the approach raced the pony, the horse clattering along a hundred yards in the rear. The grounds were enclosed by a wall, built of loose stones, about five feet in height, and, as the gate was closed, it was hoped that the obstacle would stop the runaway. The pony, however, made light of it. Gathering itself together, it went at it with a rush, cleared the wall like a steeple-chaser, then stretched away over the moorland beyond.

An all-round athlete, Sexton Blake was a consummate horseman. He also leaped the wall; then, settling himself in his saddle, prepared to wear down the runaway. He felt that his horse had the pace and bottom of the pony, and, although the lighter beast might hold its own for a short sprint, he was bound to come up in the end. It was only a matter of time.

But it was awkward riding, and called for wariness. The pony pursued a rough track, a new footpath across the moor, encumbered with loose, rolling stones, blinded often by the encroaching heather. 'To stumble meant to fall; to fall at that breakneck pace might mean death itself; accustomed to the ground, and kept their footing wonderfully. Charlie, too, was doing splendidly. He had abandoned his hug of the neck, and with a good grip of the mane in both hands, was sticking on like a monkey.

Gradually the superior stride of the pursuing horse began to tell. Inch by inch, foot by foot, the distance was lessened, till only some fifty yards lay between.

As they raced along, however, the aspect of the moor began to change. The purple heather was no longer in continuous bloom; but dull, mangy patches made their appearance, and, by-and-by, ugly-looking bog-holes. The moorland track led to the peat moss, where the natives were wont to cut their fuel, and ere long little stacks of peat were passed, waiting removal when dried. And still the pony bounded along, in headlong haste, nor could the pursuer materially reduce the gap.

All too soon, Sexton Blake discovered a new danger; the ground was growing softer and softer, the land around wetter and wetter. The peat stacks were left behind, and, on either hand, great black, ugly water-holes started up, like so many yawning mouths, wide open for a gulp.

Although the riders did not know it, they were galloping straight for the Deepsuck Moss, a quaking, bottomless bog, in which everything once engulfed was sucked down to unknown depths, never to re-appear for generations.

But though the pursuer did not know the details, he apprehended the growing, the imminent danger. He was now only some twenty yards behind; but the ground became so soft and yielding, his heavier horse was at a disadvantage with the pony. Still he urged on his steed by word, rein, and heels, and splashed madly forward.

Fifteen yards, ten yards, seven yards—he would do it yet; but just as he was considering on which side to take the flying pony, he saw a sight that filled him with dismay.

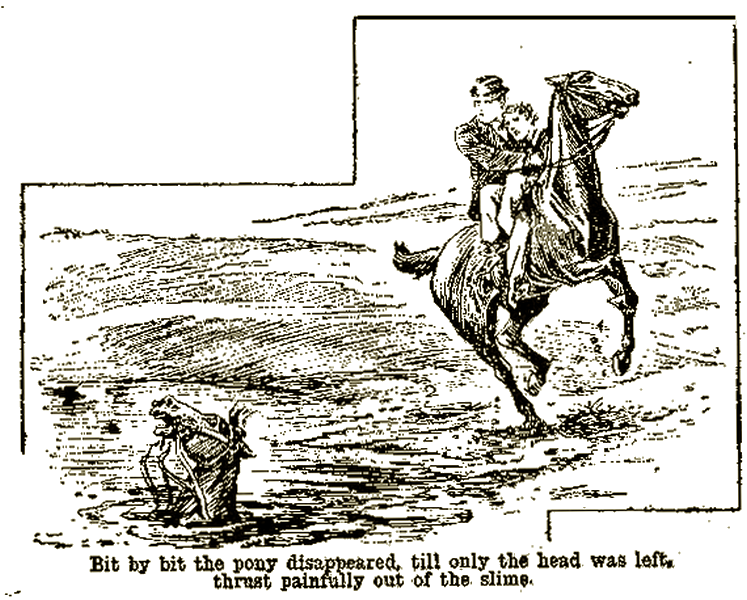

There, right ahead, stretched a long. sinister-looking sweep of moorland, covered with coarse, dank grass, mingled with stunted reeds and rushes, with here and there the gleam of water—the Deepsuck Moss. Though he did not know its name, he knew its fatal nature. Once on that treacherous sward, horses and riders would be dragged down, down, down, as in a fathomless sea. It was close by; by means of the differing vegetation, he marked the margin. It must be now or never. He rode as he never had ridden before, and, making a desperate effort, with hand, thighs, and rein, he hurled his horse forward, dashed alongside the now-faltering pony, seized Charlie, and dragged him across his own saddle; then, with a wrench that nearly threw his horse on its flank, wheeled it round on the very verge of the quick-moss—into which the pony plunged, and sank, struggling, to its withers.

The frantic distress of the poor pony was painful to witness; its maddening screams heartrending, almost human in their agonising tones. It fought and battled, heaving and swaying, rolling and wallowing, churning up the treacherous bog into a pasty mud; yet ever sinking deeper and deeper into the yielding slime. The moss around rocked gently, almost like a sea, it seemed like some fiend, quietly chuckling to itself as it leisurely gorged its victim, sucking it down into its voracious maw. Bit by bit the pony disappeared, till only the head was left, thrust painfully out of the slime; then that, too, vanished, and after some quaking convulsions, all was still.

Horror-struck, Sexton Blake had sat watching the painful tragedy, powerless to prevent it; indeed, his own situation was by no means free from peril, and called for prompt action, if he would not suffer a like fate.

His horse earlier observed the danger. Burdened as it was with a double-load, it sank to the fetlocks in the spongy ground, as, although only on the verge of the bog, the influence of the quick-moss was felt even there.

The uneasy motions of his steed, as it shuffled about, freeing one foot after another from the sticky soil, shaking its head, and twitching impatiently at the bridle, roused Blake to the danger; and, settling Charlie before him as comfortably as he could, he endeavoured to return the way he had come.

Even that course seemed perilous. A skater may safely fly at full speed over very thin ice; which, at a slower pace would not bear him; and Sexton Blake was now somewhat in the same position. The treacherous bog extended long, arm-like tentacles, like an enormous octopus far beyond its main body; again and again the rider felt his horse slipping and sinking, and, latterly, he threw the reins on the beast's neck, letting it choose its own path, relying on the sagacity of the steed to effect its own deliverance.

It was the wisest course he could adopt. The good horse justified the confidence reposed in it; and, picking its way carefully, sniffing along with its nose close to the ground, trying each step before bearing weight upon it, if gradually threaded the maze and recovered firmer footing. Ere long, it broke into an amble, and the rider was able to resume his direction; and presently he trotted into the centre of the house-party, who were anxiously following in pursuit.

Poor Charlie was soundly rated by his uncle for his thoughtless wilfulness. None but he and Rawal knew that the latter was the real culprit, the instigator and inciter of the whole affair, and Charlie, a plucky, honourable little fellow, was too manly to play the sneak; and throw the blame on his cousin. He thought that Rawal might have taken his share of the wigging; but since the Indian youth said nothing, the English boy likewise held his tongue. Had it been known that it was Rawal alone who first started and frightened the pony by his penknife prod, the result would have been different; but no one had seen the action, and that astute youth was not one to advertise it.

A Fishing Expedition; And Another "Accident."

SEVERAL days passed very pleasantly, and the party settled down quite gaily in their new quarters. The boys had always some fresh entertainment, and, in the whirl of excitement, Charlie's mad ride was almost forgotten, or, if recalled, only alluded to in joke.

The most cordial terms appeared to exist between the cousins, and any suspicions of Rawal, which might have been entertained by Sir George and Harry, were completely set at rest. The Indian youth seemed more like an elder brother than a comparative stranger whom they had never seen, scarcely ever heard of, till recently.

But Sexton Blake was not so easily satisfied, his suspicions were not so readily stilled; and; although nothing fresh occurred to verify these suspicions, he in no way relaxed his vigilant watch. Indeed, he took very good care that Rawal had no opportunity to do any evil, even if he had a mind to.

So the time sped on, until one day, after dinner, when the post-bag was brought in, Sir George and Sexton Blake retired to attend to their correspondence, and the four younger members went off to amuse themselves as best they could.

Evening was stealing on, as Charlie and Frank strolled down to the shore, the former carrying a tin can. The boy was setting up an aquarium, and, as the tide was out, he was going a-fishing in the rocky pools to provide stock for his globe; and he had persuaded his brother Frank to help him.

They had been engaged thus for some time, and had made many strange captures, shelled and finny, when they were joined by Rawal, who inquired:

"Hallo! what are you fellows up to?"

"Fishing." replied Charlie briefly.

"Fishing!" returned the other contemptuously; "why, such 'fishing' is only fit for girls and children! Now, I am going fishing in earnest; help me to drag down the punt, will you?"

Willingly enough the two boys complied, and they hauled down the small boat to the water's edge, A much larger, safer boat was lying beside the punt; but it was too heavy to move, and Rawal said he preferred the smaller one.

"You fellows coming?" Rawal inquired, when the little vessel had been launched, grounded only at the bows.

"What are you going to do?" inquired Frank.

"Going fishing,I tell you! Rare sport. Not like that childish play on which you were engaged just now. See! I have a set of drift nets here; the bay is swarming with fish; who knows what I may catch. You had better come, boys!"

"Let's go! cried Charlie eagerly, and Frank more slowly assented.

"Hi! what are you about?' said Frank, as Rawal began to transfer a number of heavy stones to the bottom of the punt.

"Better have some ballast; she is a bit crank,"' replied Rawal. " Besides, we may catch some conger eels, big, snapping fellows, that might take your leg or arm off. We must have these stones to knock them on the head."

"Don't see much fun in that! besides, it is getting dark," objected Frank; but Charlie, already in the boat, called to him to make haste, and, somewhat doubtfully, he entered, whereupon, Rawal immediately shoved off, and sprang in after him.

Frank remained seated in the bows like a figure-head; Charlie squatted astern; and, getting out the oars; Rawal sculled away amidship, heading straight for the middle of the estuary.

The fisherman appeared in no haste to commence operations; but pulled away steadily, making no answer to the questions of his cousins as to his fishing ground, till, after proceeding some three hundred yards from the shore, Frank remarked:

"I say, Rawal, I always understood that congers were caught close inshore, under the cliffs; you won't find any out here; besides, this cockle-shell is not safe, overloaded as it is with the three of us, in addition to all those big stones."

"We'll try it here, anyhow," was the reply, as the oarsman ceased rowing, and laid in his paddles; then, stooping down towards the bottom of the boat, he caught up his drift net. Some of the meshes appeared to catch on the stones, and Rawal kept pottering away in the bottom. What he was doing the others could not well make out, as he had his back to Frank, and a thwart partly screened his motions from Charlie. Further, night was falling, and objects were growing indistinct in the twilight.

Suddenly Frank shouted:

"Rawal! Rawal! Look out, man! See! the boat is filling!"

"The plug is cut!" screamed Charlie. "Look how the water is spurting in just under you, Rawal! It was firm enough when we started, for I tried it as I got in."

"Wrap your handkerchief round a tholepin and jam it in the hole!" shouted Frank. "Quick, man, or we shall sink directly!"

Rawal made a great fuss, a tremendous show in attempting to plug up the hole, but all his efforts were unavailing; still the water poured in like the jet from a force-pipe. Lower and lower sank the punt, straik by straik she settled down, till it became quickly evident that nothing could save her.

Frank made a vigorous attempt to relieve the little craft of her ballast, and heaved some of the stones overboard, but his efforts were sadly hampered by Rawal, who was working away over the leak.

"Let's shout, boys; it's our only chance!" cried Frank. And Charlie and he yelled out at the pitch of their voices:

"Help! help! We're sinking! We're drowning! Help!"

Charlie called out for his eldest brother, and sent Harry's name screaming over the water. Frank, in remembrance of his schooldays' hero, unconsciously shouted "Bravo-Blake! Sexton Blake to the rescue!"

Still no help appeared; the boat settled down lower and lower, the water came lapping over the bows, and, after a despairing glance round the fast darkening horizon, Frank called out:

"You say you can swim like a fish, Rawal. Look after Charlie. Save the boy. Never mind me; I must take my own chance."

"All right," answered Rawal.

Then the boat gave a sickening, groaning lurch, the bows dipped deeper under the surface, the water came rushing and splashing in; and, picking up one of the oars, Frank, with one foot on the gunwale; sprang clear of the foundering craft. He could not swim a stroke, but knew that his one hope—and that but a small one—was to get clear of the suction as the punt went down, then hang on to his oar as best he might, on the off chance of help arriving from the shore.

It did not take Sexton Blake long to run through his correspondence; and, postponing his replies for the moment, he put away his letters, lighted a cigar, and strolled out of doors.

"Hallo, Harry! All alone? Where are the others?" he remarked, on encountering his friend.

"Why, Blake, Charlie is starting an aquarium and Frank and he have gone down to the shore to capture some sea monsters with which to stock it!"

"Let's go and see whether they have caught any whales," remarked Blake. And together they walked slowly down to the beach.

"There is Charlie's tin pail, with some sea anemones and sticklebacks in it," said Blake: "but where are the boys? Hallo! the punt is gone! They surely have not gone out alone in that cockle-shell craft? Hark! What was that? Didn't you hear a shout? Listen again!"

"Help! help! We're sinking! We're drowning! Help! help!" came pealing across the water, followed by "Help, Harry, help!" in a shrill treble, and "'Bravo-Blake,' Sexton Blake to the rescue," in deeper tones.

" There is the other boat; let us launch it!" panted Harry.

"Too big for us, lad; too heavy! Must get assistance!' cried Blake. "Run up to the house and bring. down as many of the men as are there! Jove! I can't wait, can't stand idle after that cry! I shall swim out. Hurry the boat as you may, I think I shall reach the spot first!"

Drawing off his boots as he spoke, and throwing aside his jacket and waistcoat, the old "Bravo! Blake" rushed down the beach, dashed into the water, and set out with a long, sweeping side-stroke towards the spot from whence came the appeals; while Harry, half distracted, scudded off to arouse the house, and obtain more stable assistance.

Meantime Frank was battling away bravely yet hopelessly enough. A single scull is but a frail support for any one ignorant of natation; and although he had sprung clear of the vortex on the sinking of the boat, he was yet drawn back into it, dragged down, and whirled, tumbled, end tossed about in bewildering fashion. Rising almost breathless to the surface again, he quickly realised that he could do nothing to save his self, much less assist anyone else. The boat had gone to the bottom, sinking like the stones with which she was laden. There were no traces of either of his companions; he was utterly alone—alone and helpless!

He made no effort to raise himself or to direct his course-content merely to keep his head above water, clinging to his oar like a limpet to the rock.

It was cold weary, hopeless work; he grew numb, his senses seemed to be stealing away and yet convulsively he clutched the oar, fearing that it might slip away also.

He was almost in despair, had grown almost indifferent to his fate, when suddenly help came. His appeal was answered. A voice sounded close in his ear—the voice of the man he had last invoked; a voice from heaven, it seamed; yet the tones were only the prosaic ones of Sexton Blake.

"Hallo! Whom have we here? That you, Frank? Here, let me shove this other oar under an arm. Now, throw your other arm over the scull you are grasping so. That is better.

Now you can float safely. Hold up a little longer, help is close at hand. Now, where is Charlie? "

"Charlie? I don't know. I hope he is safe somewhere. Rawal is looking after him! spluttered Frank.

"Rawal! Was he with you, then?"

"Of course! It was he who brought us out."

"Then hang on for five minutes as you are, Frank You can do it-eh? Harry will be here within that time with the big boat. I must go and search for Charlie."

Then Frank heard Blake go surging off somewhere, and he was again alone. His position was now much more comfortable. much more secure; but the promised five minutes seemed more like five hours ere a dim shape loomed out of the gloom, and he heard the glad click, click of the oars in the rowlocks.

A wild shout, "Harry! Harry!" and the boat dashed towards him. Eager hands were stretched out to catch him, and he was hauled over the side.

"What has happened? Where is Charlie? Have you seen anything of Sexton Blake?" were the questions volleyed at the poor, half drowned youth, to which at first he found it difficult to reply; but when at length ha had told what he knew—which was little enough—those in the boat took up the search for the missing ones.

To and fro they cruised, back and forward they rowed, round and round they circled, their eyes fixed upon the water, their ears straining to catch the faintest sound.

Alas! their search was all in vain. One find they made, but that seemed only to prove the hopelessness of further search. They found poor Charles's cap floating; the wearer must have sunk to the bottom. It was useless prolonging the search in the dark. They would resume it with the morning light, but such search could only be for a lifeless body.

One hope had Harry, although but a slender one. Where was Sexton Blake? Might he not have saved Charlie? "Bravo! Blake" to the rescue once again. But if so, where was he? The chances were rather that Blake, overtaxing himself. had met the fate which he desired to avert from others, that Harry had lost a bosom friend as well as a brother.

Not until they were walking towards the house did Harry learn that Rawal had formed one of the party; and although Frank told him that their cousin had promised to look after Charlie. Harry somehow found little hope in that pledge. His sheet-anchor was "Bravo! Blake."

Charlie Is Lost - The Rescue Of Rawal.

ON the search party reaching the house, weary, draggled, and dispirited, they were astounded at finding one of the missing men, but that man the one for whom they had been least concerned. Rawal Everton sat at the supper-table in the dining-room, re-dressed, warm, dry and comfortable, regaling himself over a substantial repast.

"Why, it's Rawal!" cried Frank, rubbing his astonished eyes.

"Seen anything of Blake?" queried Harry.

"No!" replied Rawal coolly. "I expect he has funked, and is skulking somewhere."

"Who accuses Sexton Blake of 'funk' or 'skulking' said a deep voice from the doorway; and hatless, coatless, bootless, his remaining clothing wet and clinging, his whole appearance wild and dishevelled, the investigator entered the room.

"Who accuses Sexton Blake of funk or skulking?" repeated the detective. "Is it that man?' pointing sternly at the Indian youth. "Look at him, then at me. Contrast his appearance with mine, then say who most deserves these epithets."

"But where have you been, Blake? How have you succeeded? Have you any news of Charlie? Tell us your story man!" interrupted Harry hastily.

"I have but little to tell. Let Rawal tell his tale first." replied Blake.

But Rawal had little to relate either; his story was a very lame one and haltingly delivered.

When the boat sank, he averred, his leg became entangled either in the net, or with a rope, and he was dragged to the bottom with the punt. Frantically he strove to release himself, kicked and struggled; and only, when at his last gasp when all was nearly over with him, did he succeed in clearing himself. On rising to the surface, he turned over on his back and then must have lost consciousness for a time, till he was aroused by a violent blow on the head, and woke to the fact that he had been wafted ashore, and his head had struck against a rock.

"Did it raise a bump?" inquired Blake sceptically.

Without replying to the sarcasm, Rawal continued. He dragged himself to the land. Then, weak and spent, unable to help anyone, he had staggered up to the house, changed his clothes, and was having a restorative when the others arrived.

"You have recovered wonderfully quickly," commented Blake dryly. "Such accidents seem to agree with you. You look wonderfully well for a man who was on the point of death half an hour ago. I never saw you look better!"

"Hush! Mr. Blake; let us have no recriminations; this is not the time for such," interposed Sir George.

"And Charlie! Charlie!" said Harry eagerly; "have you any news of the boy. No," he continued despondingly; "I see you have not. Poor Charlie! my dear little brother is lost!"

"Yes," replied Blake slowly; "that is so; Charlie is lost! You must not expect to see or hear of him for some time."

"You mean, until his body is recovered," said Frank shuddering.

"Yes; until his body is recovered," was the reply.

Nothing further could be done that night. Search in the darkness would be unavailing, and might be perilous to the seekers, as the wind was rising, and a storm seemed imminent. All retired sadly to their rooms, under a pretence of seeking rest; but ere Sir George and Harry departed, Sexton Blake, taking them aside for a moment, said, in a low, grave voice:

"Three weeks ago there were four lives between Rawal Everton and the Everton succession! This morning there were but three. Now there appear to be but two; beware lest the number be still further reduced." Then he went off to his chamber, leaving uncle and nephew gazing into each other's eyes in helpless perplexity; yet still they refused to accept the meaning of the warning; could not comprehend such wickedness.

Small chance of sleep had anyone at Clochard that night. With every hour the wind increased, till it raged and stormed around the house like a legion of evil spirits, and by dawn a furious gale was raging.

Gloomy and silent the party met in the dining-room, their depression being increased by their surroundings.

The very daylight seemed ghastly, the low lying, ashen-grey, threatening clouds darkly luminous; away and away the tumbling sea was a sinister mass of yawning black caverns and foaming crests; while the booming roar and splintering crash of the surf against the rocks sounded like a dirge, and even indoors the air felt dark and wet with the flying sea spume.

Poor Charlie was having a dreadful "wake."

No boat could venture upon such waters; but a land search was, of course, possible; indeed, the storm itself might be an aid, as the whole estuary was in convulsion, and there was every prospect of the body being thrown ashore, if it had not already been swept out to sea.

The coast was mapped out, and such portions of the shore as could be visited were allocated amongst the party. Amid the general anxious excitement, no one noticed that Sexton Blake took no share in the discussion, although he promised readily enough to search carefully the part allotted to him.

So each member departed on his mournful quest.

At midday they met again, over an apology for lunch; but, looking wistfully into the eyes of the others, none needed to inquire how they had fared.

Rawal alone was absent; but although his lingering might afford a ray of hope, no one really expected that he would be more successful than themselves. Poor Charlie was lost, indeed!

Towards the conclusion of the moody meal, when each man was asking himself the question, " What next? and next?" the door was unceremoniously thrown open, and one of the outdoor servants rushed into the room.

"One of your young gentlemans will be in very great dangers. I am thinkin' he will be drooned!" cried the man hurriedly.

"How? Who?" exclaimed Blake, glancing round the table, forgetful for the moment of the absent Rawal.

"The 'dour' (dark, sullen) lookin' man; but come and she will see for herself; but it is not for mortal man to help that chiel this day whatefer!"

Scarcely understanding, yet fearing some fresh calamity, all hastily arose and streamed after the messenger, who led the way straight down to the beach, Sexton Blake pausing to arouse all the men-servants, and bid them follow.

On reaching the shore the man pointed across the estuary, and no further explanation was required.

On that side the land rose considerably high, precipitous rocks facing the sea, with a narrow shingly beach (covered at half tide) at their base. The tide was now making, about a quarter after the turn, and the little strip of glistening shingle lay like a broken ribbon at the foot of the rocks. Half-way towards the promontory, at the seaward end, the cliffs fell back somewhat, forming a shallow indentation, in which was visible the figure of a man. Already he was aware of his perilous position. They saw him run towards the upper end of the little bay, only to be brought up by the waters, which had already reached the foot of the cliffs at that point. At full speed he started for the other extremity, slipping and tumbling over the seaweed and wet stones, only to meet a watery barrier there, too. He was hemmed in, embayed, tide-caught; and, as if the storm-fiend rejoiced at his discomfiture, the wind came down more fiercely than before, and the angry rollers went crashing on the beach, as if striving to clutch their victim, foaming in rage as they sullenly fell back after each attempt, yet ever creeping nearer and nearer.

"It's Rawal!" cried Frank. But the others had already recognised him.

"We must save him, and shall!" exclaimed Harry decisively. "Can we reach him from the land side?" he inquired of one of the servants.

The man shook his head; then, hollowing his hand, and roaring into the ear of the youth, he briefly explained that long before they could get round to the cliffs above the water would have reached them below.

"Then we must go by water!" declared Harry. "Who will come? We have the big boat here!"

No boat could live in such a sea, the men, one and all, declared—and they ought to know, having lived in the neighbourhood all their lives.

Looking out upon that raging, boiling sea, rent by furious squalls, now showing, now hidden under driving veils of yeasty brine, Harry was silenced for the moment.

But only for the time. The furious west wind piled up the waters, and sent on the rising tide with unwonted swiftness. Bit by bit the beach was covered, narrower and narrower grew the strip of shingle at the cliff's foot, till, at last, they saw Rawal, with a desperate effort, succeed in climbing the rocky face a little way, so purchasing a respite. His reprieve would be short, however; higher it was impossible to climb, and his position was still some distance below full-tide mark. There he squatted, crouching, like a trapped beast, waiting for the inevitable end.

"He shall not perish thus!" cried the generous Harry. "I will save him, or die for it! He is there because he was looking for Charlie; Charlie's brother won't desert him now! Who will come with me? we can but try it. You shall have any reward you like, men, successful or the reverse. Who goes with me?"

"I, for one!" cried Frank, springing to his brother's side.

"No, Frank, old fellow, I won't have you," said Harry. "There are only the two of us left now; you must remain to keep up the old name!"

"Sexton Blake— Old 'Bravo! Blake,'" he continued, turning to his friend; "you have done me many great services, have stood by me times without number, will you desert me now!"

"God forbid, Harry! but think; the man is not worth the sacrifice. It is ten chances to one that we lose our lives if we attempt a rescue in such a sea!"

"For shame, Blake! It is not like you to count the cost ere doing a generous action. The 'Bravo! Blake' of old would not have hesitated thus!"

"I'm with you, lad!" was Blake's reply; then, turning to the men, he said: "Who else goes? We want three more!"

"If so as you gentlemens risks your lives (and, mind you, it's a muckle risk)," said a brawny fellow, half-boatman, half-game- keeper, "it is no' for the likes of us to hang ahint. I go for wan!"

"I'm wi' ye!" "And me, too!" cried two of the other fellows, and the lifeboat crew was complete.

It did not take long to run down the boat. Launching was a work of some danger and difficulty; but within the shelter of the little cove that had been cleared from amidst the rocks, this was safely effected, and under four oars, with the oldest and most-experienced man of the party steering with a fifth, the boat headed for the open.

Right manfully they laboured, right skilfully steered; and, on the old coxswain howling, "Easy all! but keep her nose to it!" waving his hand as his words were lost in the wind, the stiffest part of their task was done.

Gradually they drifted back, holding steadily for the point where Rawal crouched on the cliff ledge. The tide by this time had reached the base, and the angry surge, dashing high, washed the little platform on which the man nestled, threatening to sweep him off with every other wave; yet still he clung to the rocks like a limpet.

The boat could not approach the cliff within a dozen yards; to touch those rocks meant to be ground to matchwood instantly; but, watching his chance, the steersman deftly threw a rope, which was caught by Rawal, who, fastening it round his body, plunged into the sea on the crest of a receding wave, and he was hauled on board more dead than alive.

But the work was only half done; the return journey was almost as arduous and dangerous as the voyage out; still, the feeling of success cheered them on, and, adopting the same crab-like tactics, they ultimately reached the cove in safety.

Rawal, completely prostrated, was carried up to the house and put to bed; but, as the man was sensible enough, Sexton Blake said to him solemnly, ere quitting the bedroom:

"Rawal Everton, as long as you live, remember you owe your life solely to your cousin Harry! If life is of any value to you, to him alone, under Providence, are you indebted for it! I do not know whether you will ever be able to make any return; if you have the chance, see that the return is a good one!" To which exhortation Rawal made no reply.

The Visit To The Promontory - The Landslip - Frank Is Lost.

FOR a day or two Rawal Everton was confined to the house through exhaustion, following upon his late exposure; and during convalescence he was the recipient of much kindly consideration from the other members of the family. They could not overlook the fact that he owed his late peril solely to his zeal in the search; that he had nearly lost his life in his anxiety for his lost cousin, and Rawal received more sympathy than he could possibly have obtained under any other circumstances.

Meantime the search for the body of the poor boy was continued, afloat and ashore, but without any result. Beyond the cap picked up just after the accident, nothing was found, and the conviction gradually strengthened that the body had been swept out to sea, and would never be revealed "until the sea gives up its dead." Still, hoping against hope, they refused to abandon the search.

One day, when Rawal was feeling fairly strong and well again, he encountered his cousin Frank in the hall as the latter was going out, bearing a powerful telescope under his arm.

"Where are you off to, Frank?"

"Why, Rawal, I have a notion to climb that high promontory on the other side of the estuary. One must have a splendid view of the entire bay and the surrounding coast from thence. I am taking this telescope, and mean to sweep the whole surface, and search every nook and corner of it on the chance of lighting on the body of our poor little Charlie."

"I will go with you," said Rawal. "I feel that I ought to be the keenest in the search, as you know it was through me that the ill-fated fishing expedition was undertaken."

"Don't look at it in that light!" cried the generous Frank. "It must have been a pure accident, although a very strange one, and no one can blame you a bit. Why, old fellow, you have already proved how keenly you grieve over the affair—ay, almost to your own death even! But come with me, if you feel strong enough. I shall be glad of your company. Oh, dear, I miss poor Charlie sorely!"

So the two cousins set out together, apparently on the most fraternal terms. None but the servants saw them go off, Harry, Sir George, and Sexton Blake being occupied elsewhere. Had they met the two former it would have been all the same; but had the dubious detective encountered the two cousins the result might have been different, as recent events had by no means caused the investigator to abandon his former suspicions of the Indian youth. Had Blake had his way, Rawal would have been sent about his business; and although he knew better than reiterate his suspicions at present, there they were still, and would have been stirred by seeing the two youths go off together. However, Blake was far away at the moment.

The promontory was not far distant, as the crow flies, but they had to make a considerable detour to reach it; had to circle round the bay for more than a mile, until it narrowed down at the mouth of the little river Atley, which was spanned by an old stone bridge. Thereafter the path (it was not a road, but a mere mountain track) wound round the other side of the estuary, ever rising higher and higher, wild and rugged, through rough, natural cuttings and gullies; until at last, after a long, scrambling journey, the round, grassy knob of the promontory was reached.

Frank drew out his telescope, adjusted and focussed it, then swept the waters all round, searching every cave and crevice, but no trace of any human body could he discover. He walked about on the knob, viewed sea and coast from this point and from that, searched till his eye grew weary.

Weary with his walk, dispirited by his fruitless search, Frank threw himself down on the turf, close by the edge, and Rawal seated himself beside his cousin.

Much too close they were to the verge for safety. The crumbling earth, undermined and eaten away, was trembling for a further fall, and the weight of the two youths proved the last straw.

Without any warning, beyond a tumbling, crumbling feeling underneath, the ledge on which they were reclining slipped forwards and downwards, then broke into fragments, and the human débris fell as helplessly as the inanimate clods.

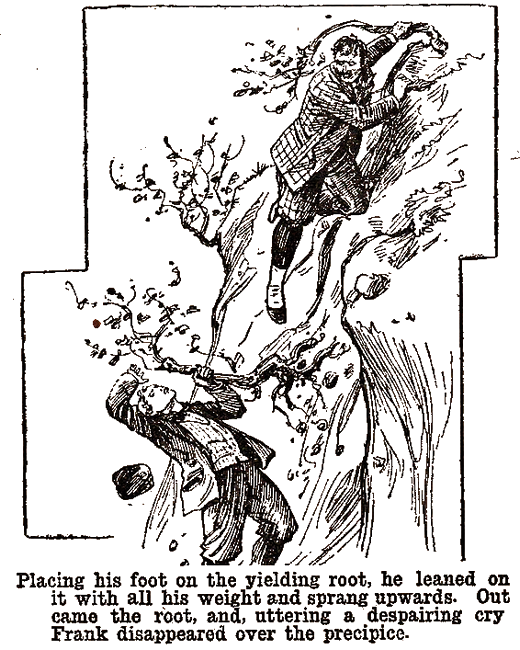

But the end was not quite yet; the earth avalanche did not descend at once sheer into the abyss; the fall was only partial, and, after a dizzy descent of a dozen feet, the two youths were brought up by a jutting ledge of rock. The stoppage was sudden, however, and found them unprepared, as, when a train or tram is suddenly stopped by the breaks, the passengers were violently jerked forward, so these two were almost pitched on into space. Frank, by seizing a hanging shrub, which, though partially uprooted, still clung to the broken soil, succeeded in arresting himself; but Rawal would have plunged forward headlong, had not his companion seized him firmly with his disengaged hand. As it was, Rawal swung round, and it was only by great exertion that Frank drew his cousin back again. The double strain, however, was too much for the frail bush to which he clung. No sooner was Rawal hurled back than Frank felt his support yielding, its roots snapping one by one, while the earth under foot at the same time began to crumble away.

Rawal, too, saw the impending danger. He clutched a firmer root that protruded from the broken soil; and, finding it secure, proceeded to haul himself up the scarred face of the cliff. His very action rendered his cousin's position more desperate, as it still further loosened the earth about the root of the shrub.

"Save me, Rawal! Give me your hand! Quick! the bush is giving!" cried Frank, as he felt the earth crumbling under hand and foot.

For an instant Rawal hesitated, but for an instant only. From his perch he could easily have extended a hand to his cousin; and, his own position secure, as the root which he gripped was sound and firm, they could both have scrambled up to the top again. Instead, he made an effort to ascend himself, climbed up a foot or two, then looked down. His foot was now on a level with the root of the bush to which Frank clung despairingly; the root was yielding under the strain; in a few seconds it would be torn away; but Rawal did not wait for that. Placing his foot on the yielding root, he leaned on it with all his weight and sprang upward. Out came the root; and, uttering a despairing cry, Frank disappeared over the precipice amidst a volley of stones and clods, as Rawal, panting and breathless, scrambled to safety on the firm ground above.

The despicable fellow no sooner found his footing secure than he started off, running down the path by which he and his cousin had come. Not for assistance. No; he had no thought for aid, no desire to render it. His only wish was to get away from the spot as quickly as possible. He never paused to see what had become of his cousin; like most cowards, he was afraid to look on his work.

A couple of hours later, Rawal, flushed and panting, breathless, and seemingly labouring under great excitement, rushed into the mansion house, and spread consternation with his calamitous tale. His story was artfully contrived, and, like most successful lies, contained a certain amount of truth. He related Frank's invitation to go to the promontory, the walk thither, the unsuccessful search, the sitting down on the verge of the precipice, and the sudden subsidence of the earth—all that was told exactly as it had occurred. Only from that point was the narrative slightly varied. Frank, he declared, was shot clean over; he, by chance, grasped the root as he was falling, hung on, and ultimately succeeded in clambering up the cliff again.

Rawal declared he had peered over the edge and had shouted aloud, but had seen or heard nothing of poor Frank. The accident had just occurred, he declared, as the tide was up, and, as the shingle at the foot of the cliffs was covered, he had raced round to Clochard to get assistance by boat.

Sexton Blake was not indoors at the time, no one knew where he was; but Sir George and Harry, summoning the servants, launched the boat, and, with Rawal, pulled across the bay to the scene of the calamity.

Here they searched carefully end long; but, although they waited till the tide turned and fell again sufficiently to leave the shingle bare, their search was wholly unsuccessful. Poor Frank had gone to join Charlie. He, also, was lost.

Sadly returning at nightfall to the landing cave, the depressed and dispirited party was met by Sexton Blake, who had learned what had occurred from the servants left behind; and, as the investigator walked up to the house with Sir George Chemworth, he said very solemnly to the baronet:

"I am not a man to say 'I told you so.' but I must ask you to recall my two previous warnings. There is only one life now between Rawal Everton and the estates. See to it that that life is not also snapped away by some sudden and strange 'accident.'"

"Good Heaven, man!' ejaculated the baronet, "do you mean to hint that Rawal Everton is a triple murderer, and is meditating a fourth crime?"

"I hint nothing." was the reply; "never do. I merely set certain facts before you; you must draw your own deductions and take your own course, Sir George."

The Last Stroke - Death Of Harry -

Rawal Succeeds To The Estates.

THE shock of this fresh catastrophe exercised different effects upon the survivors.

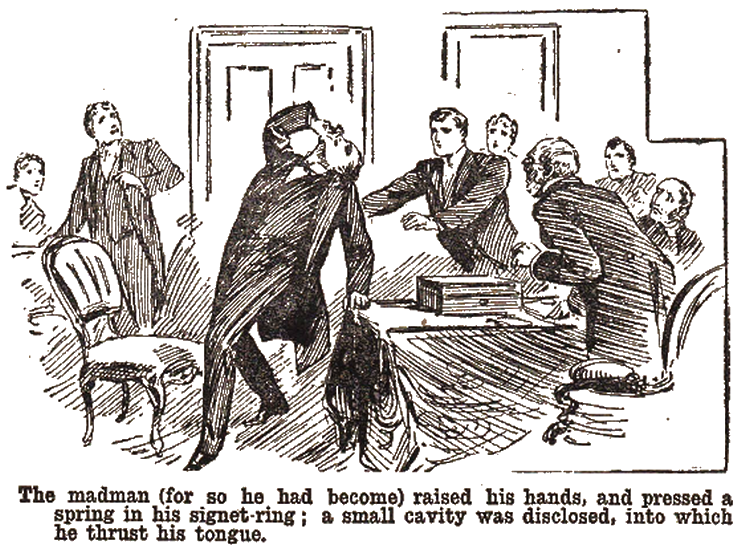

Sir George, at first utterly stunned and bewildered when he somewhat recovered himself, was all for leaving the ill-omened Clochard, with its distressing memories behind, and returning with his sole remaining nephew either to Everton Towers or to his own estate, Dalesbury, in the neighbouring county.