RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

In this remarkable long, complete novel, a very remarkable New Year adventure of Sexton Blake, Tinker, and Pedro is vividly described, It tells how the great detective and his assistants, finding themselves snowed up in a train, resolve to tramp across a moor and seek a shelter at the nearest house, and how they become members of the queerest New Year party ever gathered together.

A Winter's Journey - The Train in a Snowdrift —

A Midnight Tramp - Astray on the Moors.

"LOOKS as if we should have a bit more snow before the year's out, doesn't it, sir?"

The speaker was Tinker—the scene the platform of a railway-station in the North of England, where he, together with Sexton Blake and Pedro, were waiting for the local train which was to land them at York in time to catch the night mail for London. Business and not pleasure had been the cause of the three companions' journey to an out-of-the-way part of Yorkshire—business, however, that had been successfully accomplished a day or two before the old year ran its course.

There was a chill nip in the air as they stamped up an down the shelterless platform waiting for the train which. in accordance with the habits of local trains, was already some time overdue. Although the South of England had been favoured with a singularly mild Christmas, the same was not the case with the North — already one snowstorm had whitened the surrounding moors to the depth of several inches and, as Tinker had remarked, the sky betokened another heavy fall before long. For some time before the sun sank his face had been hidden by thick masses of dull grey cloud which had gradually overspread the whole of the sky.

"Twenty minutes late already," the detective said, as he glanced at his watch. "It's a good thing we've some time to wait at York, or we should miss the connection—Ah, there goes the signal at last!"

"Thank goodness!" Tinker said, as he gave his woollen muffler another twist round his throat. "It's what you might call a bit draughty on this wretched little platform."

Five minutes later the train had snorted into the station, and Sexton Blake, Tinker, and Pedro had tumbled into en empty compartment, just in time to escape the first white flakes driven along before the pitiless north wind.

The run—or, as Tinker impatiently expressed it, the crawl—to York was timed to take two hours; and as they had been pretty well chilled by their wait on the platform, and the carriage was badly lit and destitute of heating apparatus, the detective and his assistant would have been glad if it had been a good deal shorter. Tucking their rugs around them, they made themselves as comfortable as circumstances would permit, and for nearly an hour the train wound its way slowly along, now sheltered from the storm by overhanging heights and again exposed to the full fury of the wind as the track mounted to higher ground.

"Ugh!" Tinker grunted at last, as a fierce blast caused the window to rattle furiously and the lamps to flicker. "I shall he thankful when we get to York—this beastly carriage feels like an ice-house on wheels. Well, I suppose we sha'n't be much longer now."

The words had scarcely passed his lips when the train—which during the last few minutes had been creeping up an incline, and had then quickened its pace on the level—suddenly, with a loud hiss of escaping steam from the engine, came to a halt.

"Hallo! what's up?" Tinker exclaimed, starting to his feet and letting down the window. "There isn't any station here. Say, guv'nor, what's the mater?"

"The snow—we've stuck in a snowdrift!" the guard shouted back as he hurried by, lantern in hand.

It was true. At the top of the incline the track ran between banks three or four feet high, and between these banks the drifting snow had settled and collected in a solid mass. Into it the engine had plunged, ploughing up the snow for a few yards and then sticking fast.

Springing out of the carriage, Blake and Tinker hurried along to the engine.

"Can't you back her out. Ned?" the guard was asking anxiously as they came up.

"I'd ha' backed her out already without your telling me," the driver retorted, "if it could have been done—but it can't, The snow's got to her fires—we're stuck till they can send an engine from the junction to haul us out backwards."

A simultaneous groan issued from the group of passengers who had descended from their carriages end collected on the track. Frankly, the prospect before them was not a cheerful one. Though the worst of the snowstorm had blown over and the sky was beginning to clear, the wind was icy, and the nearest station was nearly six miles behind them. How long it would be before a relief train would arrive it was impossible to say—the guard when questioned had only a vague idea on the subject. Oastwick Junction was not more then twenty miles away, but it would be necessary to walk some distance to the nearest signal-box in order to get into communication with the junction.

"And," Blake remarked drily, "when they have heard the news at the junction, goodness knows how long they will be before they get an engine off; I know this line of old. Do you know, guard, if there's a village anywhere within reach—a place where one can put up for the night?"

"Afraid I don't, sir," the harassed guard replied. "Thorpe Ashley is somewhere about here, I know, but I couldn't direct you to it; but if you'd like to walk down the line to the signal-box with me, no doubt the chap there could tell you which way to take."

"What do you think?" Blake asked, turning to Tinker, "Shall we try and hunt up an inn, if there's one within a walk? We can't catch our train at York to-night, whatever happens, so we may as well try and find a bed instead of hanging about here waiting foe the train from the junction, which will probably be hours before it arrives."

"Right you are," Tinker agreed willingly: "anything is better than sticking here in these icy-cold carriages."

They set out accordingly along the track, accompanied by the guard and two or three of their fellow passengers, and with Pedro slouching at their heels; and twenty minutes' brisk walking brought them to the signal-box, whose occupant promptly wired the news of the stoppage along the line to Oastwick.

As the guard had said, the signalman was able to give Sexton Bake all the information he required, The nearest village was Thorpe Ashley, close on three miles away. There was a good sized inn there—the Three Feathers—and the landlord would no doubt be able to accommodate anyone who chose to walk so far. Further there was no difficulty about the way—a track across the moor struck the high-road not more than a quarter of a mile away, and when the road branched, about two miles further on, there was a signpost. It was not yet half-past nine, so that there would be plenty of time to arrive at Thorpe Ashley before the Three Feathers put up its shutters for the night.

Blake and his assistant promptly decided to set out for Thorpe Ashley; but the other three passengers, who had accompanied them as far as the signal-box, evidently had no fancy for a moorland walk through the cutting wind, and preferred to turn back and seek such shelter from the weather as the train would afford.

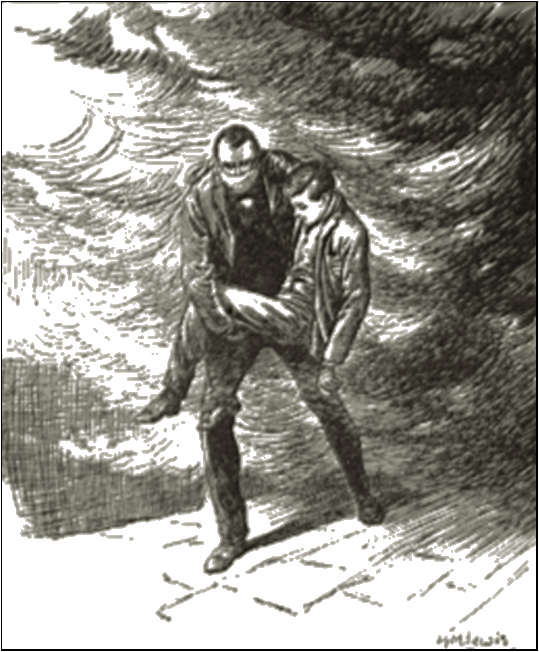

Buttoning up their coats, and bending their heads to the icy blast that came swooping in gusts across the moorland, Blake and Tinker set out on the first stage of their journey. It was only a few minutes walk to the high road, and so fierce was the wind that the exposed ground over which their way lay had been almost swept bare of snow, so that the path was easy enough to trace. Soon they were tramping along the high road, now in almost complete darkness as the moon was hidden behind scudding clouds, now able to see some distance around them over the bleak moorland landscape. The wind was against them all the way, and as it increased rather than lost in violence as time went on, their progress was much slower than they had expected, and fully an hour had gone by since they had set out, before the moon, breaking through a cloud, showed them the cross-roads of which the signalman had spoken, a little way ahead. A few minutes later they gained the parting of the ways—three roads forking oft nearly at right angles to each other.

"Now, where's the signpost?" Tinker exclaimed. "I don't see it."

In fact, no signpost was visible at the spot where it might be expected to stand.

"How's that I wonder?" Blake said. "The man distinctly told us that there was a signpost, and surely it ought to be here—Ah!"

He broke off and pointed to a post standing beside a group of blackberry bushes where the three roads met—a post between three and four feet, and with its top jagged and splintered.

"That's the signpost," he said, "or rather the remains of it. It has been broken off, and quite recently—I expect by the winds to-night. It's not been quite strong enough for that, and I dare say the wood was rotten."

"Well, where's it gone to, then?" Tinker said, in a voice of dismay, for not a sign of the board was to be seen.

Sexton Blake shrugged his shoulders.

"It has blown somewhere down that slope," he said, "for the wind's in that direction, and as the snow has all blown down there too, and is lying several feet thick at the bottom, I should say, it won't be much good our wasting our time hunting for it. We must either turn back to the train, or chance the road and go on. I'm inclined to think that we'd better turn back."

"Perhaps we had," Tinker retuned reluctantly; and then, pointing into the darkness ahead he exclaimed.

"Look, there's a light straight on—that must be the village!"

Sure enough a faint twinkle of yellow light was visible in the direction in which he pointed.

"It doesn't move," he went on, "So it must come from a house—it's about a mile off, I should say."

"About that," Blake replied. "Come along, Pedro, old chap."

And the trio stepped out briskly along the road which seemed to lead in the direction of the light. They lost sight of it almost immediately as the road wound round the shoulder of a hill, caught another glimpse of it a little nearer, and then lost sight of it again as their way led downwards into a dip between the hills. Here, though they were sheltered from the wind, the snow lay thickly—so thickly that they had considerable difficulty in keeping to the track. More than once they wandered right off it, and once Tinker floundered into a drift of snow, whence he struggled out with Blake's help damp and shivering, and long before they emerged from the valley both of them felt distinctly regretful that they had not turned back to the train at the cross-roads.

What was their dismay, therefore, when they struggled up out of the valley on to a rounded shoulder of the moorland to find that the light had completely vanished, and nothing but black darkness met their sight on every side! Further, the road had dwindled till it was little more than a track, which in itself was good evidence that they had not taken the turning leading to Thorpe Ashley.

"Here's a pretty kettle of fish!" Tinker groaned between his chattering teeth. "What on earth has become of that house? I made sure we should be close to it by now."

It can't be very far off," Blake returned hopefully. "I dare say it's hidden from us by a hill or a clump of trees. It's somewhere in that direction, I fancy—-and Pedro thinks so too. I wouldn't mind betting he'll lead us to it if we follow him. Go on, Pedro, old boy!"

The dog had turned to look inquiringly at his master, and on receiving the word of command. he gave a short bark, and turning off the path, began to trot steadily over the moor.

For five minutes or so Tinker and Blake followed him, and then they gave a simultaneous exclamation of relief as, on reaching the crest of a stretch of rising ground, they saw below them and about a hundred yards away the lighted windows of a house.

"Good old Pedro! Tinker said, patting the dog's huge head. "You've done us another good turn to-night."

The Silent House - No Answer - The Plan at the Window

A Surly Reception - Admitted at Last - Locked In.

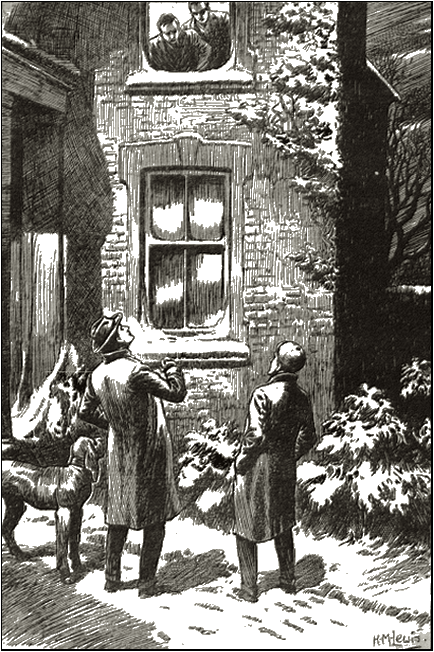

IT did not take Blake and his assistant long to scramble down the hillside and strike the path that led on to the house, which, as they neared it and the moon broke through the clouds, they saw to be a good-sized-solid-looking building surrounded by a stretch of garden. No doubt its occupants would he rather surprised to receive a visit at that time of the night from two complete strangers, but it was hardly likely that they would be so churlish as to refuse some sort of hospitality to benighted travellers.

Mounting the steps to the portico, Blake felt for the knocker and rapped loudly. But a couple of minutes went by and no one approached the door.

"Knock again, guv'nor," Tinker said, as he blew on his fingers and stamped vigorously. "They're not all asleep; I saw a shadow cross the blinds just now."

A second time the detective knocked, even more loudly, and accompanying the rap by a peal of the bell that echoed through the house. The result was the same, and a third attempt was equally unsuccessful.

Blake and Tinker looked at each other in astonishment.

"What on earth does it mean?" the boy exclaimed. "They must know we're here; don't they want to let us in?"

"Evidently not," Blake returned. "Perhaps there are only women in the house, and they are afraid to open the door."

"No; it was a man's shadow I saw on the blind." Tinker said, "Look, there it is again, and he's putting the blind on one side to have a look at us!"

It was true. The shadow of a man's figure was thrown clearly for a moment upon the blind of one of the windows on the first floor, and the blind itself was pulled slightly to one side and then dropped again as the shadow vanished.

"Well now he has had a look at us I hope he'll come and open the door," Blake said impatiently.

But in this expectation he was disappointed. No one came: and a fourth thundering rap had exactly the same effect as the three former ones.

"It's no good. guv'nor." Tinker said at last, "They don't mean to let us in. We shall have to give it up as a bad job and find our way to Thorpe Ashley, or else go back to the train, if it hasn't gone."

"Nonsense!" the detective replied decisively, as he once again awoke the echoes with the knocker. "I'm going to have the door opened, or know the reason why. There's something queer about this extraordinary silence, and I intend to find out what it is. Let's try if this has any effect." And. stooping down, he gathered up a handful of gravel from the drive and flung it at the window at which the shadow had appeared.

There was no response at first, but after Blake had sent a second shower of gravel pattering on the glass the blind was suddenly drawn up, the window flung open, and two or three figures appeared looking out of it.

"Go away!" a man's voice called curtly. "Whoever you are, go away! It's no use your knocking; we sha'n't let you in."

And the speaker drew back his head, and had raised his hands to shut the window again when Blake's voice arrested the action.

"One moment!" the detective called out. "Will you let me explain?"

"Explanations are quite unnecessary," was the retort from the window. "However much you explain, you won't be allowed to set foot in this house this side of January 1st, so the best thing you can do is to take yourselves off at once."

"What is it you are afraid of?" Blake called back, as the man's hand went up to the sash. "Surely you don't imagine that my friend and I and I are thieves. We should not be such fools as to rouse you by knocking at the door if we wanted to rob the house."

"It doesn't matter what we imagine," was the rough reply. "The only thing that matters to you is that you will not be allowed to set foot within this house, so off with you!"

"It's no good." Tinker muttered disconsolately. "That chap means what he says. We shall have to hook it."

"Wait a moment before you shut the window," the detective called up. "If you won't let us in, perhaps you will at least have the civility to direct us to Thorpe Ashley, or some other place where we can get food and shelter for the night. We are both of us very badly in need of it, and my friend is wet through from falling into a snowdrift. We are complete strangers in these parts; we were travelling to York by a train that got stuck in a snowdrift a few miles from here, and in trying to find our way to the inn at Thorpe Ashley we have lost our way on the moor."

"H'm!" the man at the window grunted. "So that's your story, is it? Well, whether it's true or not, I shouldn't mind directing you to Thorpe Ashley or anywhere else if I knew the way, but as I'm also a stranger in these parts I don't. Do you know where Thorpe Ashley is?" he went on, turning to another man who had been standing silently behind him.

The latter shook his head, whereupon the speaker vanished from the window, which, however, he left open.

"I suppose he has gone to make inquiries from someone else in the house," Blake said in a low voice, keeping his eyes upon the lighted window.

And a moment later someone else appeared at it—this time the slight figure of a young woman, who peered down over the sill at Blake and his assistant, and then hurriedly drew back and vanished in her turn.

"I wonder how many people there are in the house," Tinker muttered. "That's four I've seen—-there were three men standing at the window just now, and now that girl. It's a queer go, isn't it, guv'nor; what on earth makes 'em so frightened of us? I wish that fellow would he quick. It's beginning to snow again, and pretty thickly, too."

It was true. The sky had been clouding over heavily for the last few minutes, and suddenly heavy flakes had began to descend so thickly that the surrounding hills were immediately blotted out from sight.

Three or four minutes went by, and then once again the man who had spoken to them before came to the window.

"I'm sorry," he called out sullenly, "but we are all of us strangers in this district. No one in the house can direct you to Thorpe Ashley; you must find it us best you can. We can't help you."

"Look here," Blake returned angrily, "do you really mean to say that you are going to turn us away on a night like this to wander about the moors, with the snow coming down so that it is impossible to see a couple of yards ahead? If you won't let us into your house, will you let us have a shakedown in a stable or an outhouse? We are willing to pay handsomely for shelter, and, if you don't give it us the chances are we shall be frozen to death before morning."

For the first time the detective's arguments appeared to have made some impression on the stranger. He glanced up at the threatening sky, hesitated, and, then turned abruptly away from the window.

And Blake and Tinker, standing shivering upon the pathway below could hear the sound of several voices talking in the lighted room above them. Though they could not hear what was said, they could distinguish the different tones—-three or four men's voices and now and again a woman's. More than five minutes went by, and then once again the same man appeared and leaned out over the sill.

"Are you armed " he asked abruptly.

"I have a revolver in my pocket,' the detective answered, astonished at the question.

"Throw it in at the window, then."

"What do you mean?" Blake exclaimed, still more astonished.

"What I say. As it is quite possible your story may he true, we have decided to allow you to take shelter here for the night, but before we let you in we require you to give up any arms you possess. If you prefer to stick to your revolver, you can stay where you are.

"Stand beak from the window," Blake replied quietly. And as the man slipped aside he tossed his revolver over the sill.

The window was immediately closed, and a moment later steps could be heard descending the stairs and echoing through the hall. Then the bolts were withdrawn and the door flung open, disclosing to view a largo oak-panelled hall, lit by a gas chandelier, with a broad staircase leading to the upper floor.

Just inside the door two men were standing, and it did not escape the detective's quick eye that one of them-—a slight, good-looking young fellow of about twenty-—was holding a revolver in his right hand. The other was the man who had addressed them from the window-—tall, broad-shouldered, and red-haired.

The latter it was who had opened the door, and as soon as Sexton Blake and Tinker, followed by Pedro, had crossed the threshold, he slammed it to again, locked it quickly, took out the key and shot the three or four heavy bolts with which it was furnished. And Sexton Blake's quick glance round the hall showed him that the heavy shutters over the windows were likewise strongly padlocked and bolted, as were the doors leading into other rooms on the ground floor.

Neither Sexton Blake or Tinker could ever have been accused of being nervous, but to say that they did not feel a little uncomfortable thrill as the key grated in the lock of the front door and they found themselves in what seemed practically a prison, would be hardly the truth.

Nor was there anything very reassuring in their reception by the two men who had so reluctantly admitted them, and who, as they entered, scanned them with quick, suspicious glances, the younger of the two keeping his finger upon the trigger of his revolver as he did so.

"Is your dog under control?" the elder asked sharply.

"Perfectly."

"H'm! He looks as if he were capable of killing a man if he tried."

"Pedro is quite capable of it," Blake replied drily. "But you need not be alarmed; Pedro is the quietest beast going, unless I order him to be otherwise."

"Oh, I'm not alarmed!" the stranger replied, calmly tapping his breast, pocket. "I should shoot him if he tried to fly at me. I was only thinking of my sister; she is upstairs, and a huge beast like that might frighten her."

"I will see that he is on his best behaviour," Blake returned. "To heel, Pedro!"

"This way, then," the other returned in the same unwilling tone, and he led the way upstairs, Blake and Tinker following him, and the young man bringing up the rear.

Opening a door on the first floor, he ushered them into a large, well-lit room, where three other people were sitting around a blazing fire. Two of them—-a slight girl, whose face would have been distinctly pretty but for its intense paleness, and a stalwart young man of about five-and-twenty-—rose to their feet as the new-comers entered; the third did not stir, but the crutches which were propped against the chair showed the reason for his unwillingness to move.

It did not escape the notice of Blake and Tinker that the three strangers, one and all, glared at them with the same sharp suspicion with which the others had greeted them in the hall. For the moment there was an awkward silence, which was broken by the girl.

"I expect you must be fearfully cold and hungry," she said in a nervous, hesitating voice. "If you will sit down and warm yourselves by the fire I will get you something to eat. Will you accompany me to the kitchen, Kenneth?"

And she went out, followed by the young man whom she had addressed as Kenneth-—the same who had held the revolver when the door was opened.

Blake and Tinker were glad enough to avail themselves of the invitation to draw near the fire, but they would have been a good deal more at their ease if their hosts had made the slightest effort to disguise the reluctance which they felt at admitting the two strangers. Neither of them spoke a word, but the detective was conscious that his every movement was curiously watched; even the cripple, as he lay back on his couch with his eyes apparently closed, was peering nervously from under his lashes.

That there was some mystery concealed behind his hosts' curious behaviour, Sexton Blake felt certain. It did not escape him that though all of them were comparatively young, their faces wore an expression of intense anxiety-—anxiety that seemed as if it were a habit. Nor did he fail to note that at the slightest sound—-the creaking of a board or even the dropping of a cinder in the grate-—each of them would start and look round sharply. Another curious thing was, that though the room was comfortably and even luxuriously furnished, there appeared to be no servants in the house, since it had been necessary for two of the party to go down to the kitchen themselves in order to obtain food for the strangers.

After a few minutes of awkward silence the girl and her companion returned, bringing with them a plentiful supply of cold chicken, ham and bread, upon which Tinker and Blake were glad enough to fall to.

Hungry as they were, they were glad when the meal was over. Tinker afterwards declared he felt like an animal at the zoo while it was going on; he never looked up from his plate without finding that someone was watching him more or less intently. Blake endured the ordeal with seeming indifference, but it was all that Tinker could do not to show his annoyance at his hosts' scrutiny.

Complete silence reigned during the meal, and the first to break it was the detective, who, as he pushed away his plate, glanced up at the clock on the mantelpiece.

"I see it is nearly twelve," he said. "I need hardly say that we are very tired, and we should be much obliged if you would let us know where we are to sleep. Any sort of a shake-down would do; we are not particular."

"There are plenty of spare bed-rooms in the house," the red-haired man replied coldly. "We will have one ready for you in a few minutes. Will you come with me, Oscar?"

The man who was addressed as Oscar nodded, rose from his seat, and left the room with his red-haired companion; and again silence fell upon the little company. Sexton Blake made an attempt to break it by speaking to the girl; but though she answered him, it was with an obvious effort, and he saw that her eyes kept wandering round the room with the same nervous look in them that he had observed, though not so strongly, in the other members of the household.

After an absence of about ten minutes Oscar and his companion returned, and informed the guests that their room was ready for them.

"Curious," Blake said to himself, as he followed the pair out of the room. "Why do these people always go about in couples? It even takes taco of them to show us the way to our bed-room."

"This is your room." Oscar said. pausing at a door at the end of the passage. "I hope you will find all you want in it. Good-night!"

And, with no more ceremony, he closed the door sharply behind him.

The travellers certainly had no reason to complain of their sleeping quarters—-a large, lofty room, containing a couple of beds and with a cheerful fire crackling in the grate.

"This isn't so bad—eh?" Tinker said, as he looked round approvingly. "But what does it all mean? They're the queerest lot I ever came across."

"Listen!" Blake said sharply. holding up his finger.

Tinker listened, and distinctly heard a faint grating sound. On tiptoe he stole across the room to the door, seized the handle and turned it gently; then he looked at the detective and nodded.

"Yes," he said, "that's it; they've locked us in! What the dickens is the meaning of it? "

A Midnight Expedition - A Check -

A Voice in the Dark - A Rescue - Just in Time.

SEXTON BLAKE drew his brows together, while a queer smile played round his lips.

"That's just what I don't know at present." he replied; " but I intend to know before very long, Tinker."

"Right you are," Tinker returned. "What do you make of it all, guv'nor 7 Why are these people so afraid of us?"

"It isn't only us they are afraid of," Blake said quietly, "they are afraid of each other."

"Of each other!"

The detective nodded.

"Yes: I noticed that when they were not watching us they were watching each other. Not one of them ever seemed to be at his ease; they were always on the alert, always nervously listening and waiting for something to happen."

"Are they all one family? " Tinker said. "They seem to call each other by their Christian names."

"I rather fancy they are," Blake replied. "The girl is the red-haired man's sister, of course, and there is a distinct likeness between the two they call Oscar and Kenneth."

"Take them all round," Tinker said. reflectively, "they're the oddest New Year's party I've ever come across. I wonder how long they've been living shut up by themselves like this?"

"That is impossible to say, but it is clear, from what the red-haired man said, that they mean to go on living in this extraordinary way till New Year's Day. You remember what he called to us out of the window—-that we shouldn't be allowed to set foot in the place this side of January 1st."

"If we are to get to the bottom of the mystery," the detective went on, "we must set to work to-night, for our hosts will certainly not ask us to stay on after to-morrow morning. If we could have a look round the house, perhaps we could hit on something that would put us on the scent."

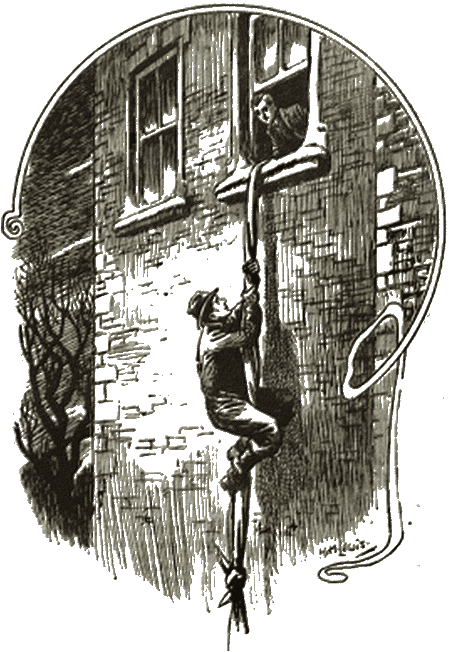

"But how are we to get a look round?" Tinker asked, pointing to the locked door. Before replying, the detective went to the window, raised it, and looked out.

"I think it can be managed." he said, as he closed the window; "but we must wait an hour or two till the house is quiet. They are moving about in the passage now. Listen! That is the tap of the cripple's crutch, so they are probably on their way to bed. As soon as I think they are asleep I shall explore the place."

"But how are you going to manage it? They'll hear us if we break the door open."

"I'm not going to break the door open. When I looked out of the window just now I saw that there was another window with a little iron balcony before it, only a few feet away. It is only on the ground floor that the windows are shuttered, so that it will he easy enough to step from our window-sill on to the balcony, raise the sash, and get into the room beyond—-if no one is sleeping there, that is to say-—and we can find that out by seeing if a light appears at the window."

Tinker nodded.

"We shall have to be careful," he said. "These fellows are all armed, and if they find us prowling about the place, they will shoot us at sight."

"I haven't the least doubt of that," Blake replied grimly. "All the same. I'm not going to leave this house to-morrow without having had a try to get to the bottom of the mystery that hangs over it. Meanwhile, we'd better put out the lights, so that our hosts, if they are curious on the subject, will imagine that we have gone to bed."

He turned out the gas as he spoke, and he and Tinker seated themselves in front of the fire, before which Pedro was already stretched comfortably asleep. For a little while they heard subdued sounds of people moving about the house-—the occasional passing of a footstep in the passage and the closing of a distant door-—and then complete silence fell, broken only by the crackle of the fire in the grate and the moaning of the wind outside. Once or twice Sexton Blake crept on tiptoe to the window and peered out, so as to see if there was a light in the next room; but greatly to his satisfaction it remained in complete darkness, showing that no one could be sleeping there.

More than two hours went by before the detective deemed it safe to act, and it was not till the fire was dying down into ashes and two o'clock had chimed out from the little clock on the mantelpiece that, he quietly rose to his feet and laid his hand on Tinker's shoulder. The boy had been half dozing in his chair, but the touch of Blake's hand roused him in an instant.

"Ready?" the detective whispered. "Then come along-—quietly, mind. Lie down, Pedro, old boy; we don't want you yet."

The dog lay down obediently, and, on tiptoe Sexton Blake and Tinker crossed the room and with the utmost caution raised the window-sash, letting in a rush of cold air. The snow had ceased, and the sky overhead was clear and frosty, while the white, rounded tops of the hills showed up sharply against the dark blue overhead.

Brushing away the snow from the window-sill. Blake placed his knee upon it, and was about to draw himself up into a standing position, when Tinker suddenly laid a hand upon his arm.

"Look! " he whispered. "What is that light, I wonder? There isn't a, house there, for it's just by the way we came. Besides, it wasn't there a moment ago."

He pointed as he spoke along the valley to a yellow point of light which had just flashed into view from the surrounding darkness. Sexton Blake turned his head to look, but he had barely caught sight of the light when it vanished as suddenly as it had appeared. Not for long, however. After on interval of perhaps ten seconds it shone out again exactly in the same spot. glowed brightly for an instant, and was then once more extinguished.

"Curious," Blake whispered. "Can it be a signal of some kind? There it is again!"

Once again, after exactly the same interval of darkness, the light shone out and disappeared, and this time it did not appear again.

But something else did. Blake and Tinker were still gazing at the spot at which it had vanished, when suddenly the snow beneath them reflected a broad ray of light. And, looking upwards, they saw it came from, a window immediately above them. Just as the light down the valley, had done, it shone out for an instant, vanished, and then, twice reappeared.

"It is a signal!" Blake said, under his breath. "Tinker, we must be careful. Someone is awake in the house, and I have not got my revolver."

He raised himself cautiously on the sill, gripped with one hand the brickwork at the side of the window, and stretched out the other until he grasped the rail of the balcony; and in another moment he was standing on the balcony and giving Tinker a helping hand as the boy in his turn stepped across to it.

The window before which they were standing was, of course, raised, but it did not take the detective long to get his knife under the hasp and gently force it back. Then, very gingerly, they raised the sash and stepped into the darkened room beyond. Once inside, the detective listened for a moment to make sure that they were alone, and then, drawing out a tiny electric pocket-lamp, he switched it on.

As they had expected, the room, which was a very small one, was empty: hut to their dismay they saw that the only door which led out of it opened not directly into the passage, but into another room, from which, earlier in In night, the detective had remarked that a light was shining. It was easy to see, from the way it was furnished and the clothes hanging on the rail, that the little room they had entered was used as a dressing-room by the man who occupied the room beyond.

"Hallo! what's to be done now? " Tinker whispered. "Do you think it would be safe to try and get through the next room?"

"Rather too risky. I'm afraid," Blake returned. "Our hosts all seemed to go about armed. The probability is that the fellow in the next room sleeps with his revolver under his pillow. Besides," he added, a moment later, after cautiously trying the handle of the door, "the thing's an impossibility! Our friend has taken the precaution to lock his bed-room door on the inside. I'm afraid, there's nothing but to go back by the way we came."

"Hard lines," Tinker muttered reluctantly.

"Better luck next time," the detective whispered back cheerfully. "Don't you worry, Tinker, I've made up my mind to get to the bottom of this business some way or other, but meanwhile, the best thing we can do it to get a night's rest. Halo! what was that?"

As he spoke he switched off the light, and he and Tinker stood listening intently, for a sound had reached their ears from the next room. For a moment they feared that they had aroused their neighbour, then the sound was repeated-a long-drawn, gurgling groan, like that of a man gasping and fighting for his breath. Tinker felt a cold thrill run down his back, and involuntarily he gripped at the detective's arm.

'What is it? " he whispered. "It sounds as if he were dying. There it is again!"

For again the groaning sound had reached their ears, this time more faintly, as if the sufferer were almost at his last gasp.

Sexton Blake hesitated no longer. Someone in the room beyond was in dire need of help, of that he felt sure, and with a bound he hurled himself against the drawing-room door. He had to repeat the attack three or four times before it was successful, but at last the hinges yielded to his vigorous assault, and with a crash the door swung open and Blake and Tinker rushed into time room beyond. As they did so an overpowering smell of gas assailed their nostrils, and as Sexton Blake switched on his electric lamp, Tinker darted to the window and flung it wide open, so as to let a rush of fresh air into the thick and stifling atmosphere.

A quick glance round the room showed Blake that there was only one person in it-—the man who had uttered the groans, and who was lying in a huddled heap at the side of the bed. Falling on his knees beside him, the detective turned him over on his back, and saw that it was the young fellow who had been addressed as Kenneth, ghastly pale and to all appearance lifeless. Evidently he had awoke to find himself suffocating, had dragged himself out of bed to get at the gas and turn it off, and before he could reach the bracket, had fallen to the ground, overcome by the fumes.

"Is he dead?" Tinker asked, in an awe-struck voice, as Sexton Blake laid his hand on the young man's breast.

"No; his heart is still beating. Open the door quickly, and let us get him out of this horrible atmosphere as quickly as we can.

And the detective hoisted the unconscious man into his arms while Tinker hurriedly unfastened the door leading to the passage, which, like all the doors in this house of mystery, was locked and bolted.

Evidently the noise they had made in breaking into the room had attracted the attention of others in the house, for they heard the sound of voices and of feet hurrying along the passage, and as Tinker flung open the door he saw the man who had been addressed as Oscar only a few paces off. And no sooner did the latter perceive the lad, than with an exclamation of amazement he snatched a revolver from his pocket and presented it at Tinker's head.

"Drop it!" Tinker said coolly. "I'm not going to hurt you. Don't be such a fool! Put away your pop-gun, and come and help us look after your friend,"

And he pointed to Sexton Blake, who came staggering into the passage carrying the limp figure of Kenneth in his arms. Oscar gave a cry of horror.

"You have killed him!" he cried, turning his weapon from Tinker to the detective. Like lightning the boy sprang forward, and, knocking his hand up, held it pointed towards the ceiling,

"Killed him?" he said. "If it wasn't for us he'd have been dead by now. Are you all mad here?"

"Go into the room and see for yourself," Blake said quietly. as he laid his burden down in the passage. "It is full of gas. Your friend would have been dead if he had been left there a few minutes longer. We heard him groaning, and broke in just in time to save him. He will come round before long, I hope, now that we have got him out of that choking atmosphere."

Oscar stared at the detective's face as if uncertain to believe him or not, and then turned towards the red-haired man, who at that moment came dashing along the passage.

"It's Kenneth this time, George!" he said; and then with a groan he buried his face in his hands.

Sexton Blake Reveals Himself - His Host's Story - The Five Heirs.

LIKE his companion, the red-haired man was at first inclined to lay the blame for what had happened at the door of Sexton Blake and Tinker: but the detective's quiet story, together with the evidence of his own senses as the fumes of gas spread into the passage, soon convinced him of his mistake.

"But how did you manage to get into the room? " he asked sharply.

"I'll tell you the whole story directly." Blake replied: "but the first thing to do is to at tend to your friend. Where had we better take him; we can't leave him in this icy passage?"

"There's a fire in the sitting-room. We'll carry him down there," the other replied.

Accordingly, wrapping the still unconscious Kenneth in blankets, they carried him along the corridor to the sitting-room, where lights were still burning and a large fire blazing on the hearth.

"Two of us sit here all night to keep watch." Oscar explained, as he saw the detective glance round curiously at the flaring gas-jets.

From the moment that Kenneth had been carried out of his bed-room he had begun to breathe more easily, and it was not long after he had been laid on the sofa before he opened his eyes and looked round him with a bewildered gaze. As soon as he saw that Kenneth was well on the way to recovery. Sexton Blake slipped quietly out of the room and made a careful examination of the gas-bracket which had so nearly been the means of the young man's death, and by the time he re-entered the room he found that the patient was sitting up and able to give an account of his experiences. All he knew about the matter was that he had awakened with a terrible feeling of suffocation: that he had got out of bed intending to call for help, but had lost his senses before he could reach the door. As for the gas, he was perfectly certain that he had turned it off carefully before he got into bed.

There was silence when he had finished, and Sexton Blake noticed that the three men eyed each other with the same look of gloomy distrust, that he had so often remarked in their faces before. Kenneth was the first to speak.

"I suppose the scoundrel—whoever he may he—got into my room and turned the gas on while I was asleep. How he managed it I can't think, for both doors were locked, and I am a very light sleeper."

"You are quite mistaken." Sexton Blake said quietly. "Until we broke open the door you were the only person to enter your room to-night."

"How do you know?" sprang simultaneously to the lips of his hearers as they turned and stared at him sharply.

"I quite agree with you," the detective went on in the same even tone, "that the escape of gas in your room to-night was the deliberate work of a would-be assassin: but he did not go to work in the way you imagine. His plan of operations was much more skilful, and it is quite possible that it was carried out some days ago. What he did was this: He bored a hole in the gas-pipe about two inches from the wall—a hole large enough to allow a considerable quantity of gas to escape; this hole he then filled up with wax, and you can easily see that every time the gas was lighted and the pipe got warmed the wax would begin to melt, until gradually it melted away entirely, when the gas would flow into the room unhindered. That is what happened to-night. If you doubt, it go and look at the hole in the pipe. You will easily see it, although I have stuffed it up for the present: and on the floor beneath the bracket you will find the stain made by the dropping grease."

The three men stared at him in amazement.

Smiling quietly. Sexton Blake took a card from his pocket-book and handed it to Ike red-haired man.

"That is my name," he said. "If you had asked me I should certainly have given it you before."

"Mr. Sexton Blake, the detective?" the other exclaimed.

"ExactlY," Blake replied. "Now that you know who I am, don't you think you would be wise in letting me into the secret of the mystery that overhangs this house. Of course I don't wish to force my services upon you, but I

think I have proved to you that I should be able to be of assistance in the matter."

The three men looked at each other for a moment, and then Oscar said firmly:

"I certainly think that we ought to accept Mr. Sexton Blake's offer. Curiously enough, I was wondering an hour or two ago whether I should write to him and lay the matter before him. As the other detectives have failed so completely in attempting to solve the mystery. I ought to have done so before. What do you say. George?"

"I am quite willing to take Mr. Blake into our confidence," he said.

"And so am I." Kenneth said decidedly.

"Sit down, Mr. Blake," the red-haired man said as he pushed an armchair towards the fire. "I will be as brief as I can, but the story will take a few minutes to tell, and when you have heard it I believe you will forgive the very discourteous reception you met with on your arrival to-night."

"To begin with I must tell you who we are. My own name is George Gilfayne, and these are my cousins, Oscar Neville and Kenneth Brant. The other occupants of the house, whom you have already seen, are my sister Brenda, and our crippled cousin Felix Gilfayne."

"You are, in fact, a family party," Blake nodded.

"Exactly: but as you already know a peculiar family party. And now for the reason of the extraordinary life we lead here. Just five-and twenty years ago there died in Manchester a successful cotton-broker named Joseph Gilfayne, my great-uncle. At the time of his death he was known to have a good round sum invested in excellent securities, and, as he had never married, his brother Walter, who was his only surviving relation, naturally imagined that be would be the sole heir. To his surprise and annoyance, however, Walter Gilfayne discovered that Joseph, who had always been slightly eccentric, had made a peculiar will. He had left his property to accumulate in the hands of trustees for five-and-twenty years. Not a penny of it was to be touched before the time was up, but at the end of the twenty-fifth year the whole sum was to be divided among such of his descendants as were then alive, each taking an equal share."

"I see," Blake said, as George Gilfayne paused. "And the five-and-twenty years are now up? "

"They will he on New Year's Day. it is on January 1st that the distribution of my great-uncle's fortune is to be made between the five persons whom you have met in this house."

"And what is the amount to be divided between you?"

"Roughly speaking, a hundred thousand pounds."

"A hundred thousand pounds. Then, as there are five of you, you will each be entitled to about twenty thousand."

"If there are five of us alive on New Year's Day," Oscar Neville broke in with a forced laugh. "But the chances

are that we shall not all of us be alive when January 1st comes round."

"What Oscar says is true," George Gilfayne went on quietly. "It is very unlikely that we shall all be alive three days from now. Mr. Blake, you yourself have been a witness of the danger that has threatened one of us to-night, so you will know that I am not exaggerating when I tell you that for the past few weeks we have been living in constant fear of our lives. Again and again some such terrible peril has threatened—or seemed to threaten—each in turn. And again and again we have escaped only by the skin of our teeth."

"And bow long has this state of things been going on?" Sexton Blake asked.

"Since the beginning of this month—December. It was on December 2nd that the first attempt was made. Felix was selected as the victim on that occasion."

"The cripple?"

"Yes. His bed-room was set on fire one night after he had fallen asleep, and he would certainly have been suffocated or burned, since be could not find his crutches, and is almost helpless without them, if his valet Morton had not happened to smell the smoke. He hurried upstairs, heard his master's cries, dashed in, and carried Felix out of the burning room only just in time. The fire was got under, but not the slightest clue to its origin could ever be found. Still, it would probably have been considered the result of an accident if it had not been for what has happened since.

"Three days after Felix had so narrowly escaped with his life from fire, I had an equally narrow escape. My sister Brenda and I have been living for the last year or two in a little village in Hertfordshire, not far from Hatfield, and I have been in the habit of bicycling in the morning to catch the train to King's Cross, and bicycling back at night. The distance is nearly three miles each way.

"On the evening of December 5th I was bicycling homewards, and had reached a point on the high-road about a mile and a half from Hatfield, when I heard the rattle of a motor-car behind me, and, looking back, I saw a large and heavy car descending the hill behind me at a terrific speed. I remember thinking how unfair it was to other users of the road to dash through the dark at that pace, and then I turned off at the main road into the lane that formed a short cut to our cottage. I had only got a short distance along it—perhaps thirty to forty yards—when the motor also swung round the corner, and without diminishing its pace in the least, swept towards me down the lane. So narrow was the space between the hedges, and so reckless did the driver seem to be, that I took care to ride almost in the gutter, leaving the road entirely to the car.

"I might as well have saved myself the trouble; for as I looked over my shoulders I saw the huge vehicle suddenly and deliberately swerve to the wrong side of the road, and the next instant I was flying through the air, and lost my senses as I struck the ground with a violent thud.

"When I came to myself, about half an hour later, not a sign of the car was to be seen; the only traces of the accident were my broken bicycle and the injuries I had received—and which, fortunately, though painful, were not very serious. I was able to limp home, and a few days' doctoring set me on my feet again but though I had inquiries made in every direction, the car was never traced, nor to this day have I been able to discover who the man was who deliberately tried to murder me."

"You would not recognise him, I suppose? " the detective asked.

George Gilfayne shook his head.

"He wore goggles, and a coat with a collar turned up over his month. I should not know him from Adam, I am sorry to say," he returned bitterly.

As George Gilfayne rested his head upon his hand and stared moodily at the fire, his cousin, Oscar Neville, took up the story.

"I was the next," he said. "A few days after George's adventure—on December 10th—I got a letter signed by an old college friend of mine, Jack Westbrook. I had been great friends with Jack at the Varsity, and I was horrified to find from his letter that he was in awful trouble. What the trouble was he did not say exactly, but he hinted that he dared not show his face anywhere where he might be recognised, and begged me to meet him that night down by the London docks.

"As I dare say you have guessed already, Mr. Blake, the whole thing was a hoax. I have heard since that Jack Westbrook is doing very well in the diplomatic service; but at the time I was completely taken in, and following the directions given me in the letter. I found myself between eleven and twelve o'clock that night, on a lonely wharf not far from the East India Docks. After I had waited there for about ten minutes, I heard a step behind me. I turned, expecting to see Jack Westbrook, and I received instead a stunning blow on the head with a heavy stick—a blow that sent me toppling backwards over the edge of the wharf. Fortunately, my head is pretty thick, and the tap which was meant to stun me did not quite effect its purpose. The plunge under the water brought me round pretty quickly, and as I am a pretty fair swimmer, I had no difficulty in keeping afloat until I reached some waterside steps. That was my adventure, Mr. Blake, and, like George, I have no idea what my assailant was like, it was dark when he attacked me, and he held his head down, with a cap pulled down right over his eyes and a muffler twisted round his throat and chin."

The detective nodded without making any comment; then he turned to Kenneth Brant.

"And you, Mr. Brant," he asked; "have you ever been attacked before to-night? "

The young man nodded.

"Yes," he said; "it was on December 12th. I was standing on the platform at Clapham Junction waiting for a train back to Victoria. It was between ten and eleven at night, and there was rather a thick fog. The train was late, and I had strolled almost to the end of the platform, and was standing there alone when I saw the lights of the engine appear through the fog. At the same instant a man who had been standing a few paces away from me, still further along the platform, turned suddenly and ran by me—and as he passed he struck out at my head with his clenched fist, and sent me reeling backwards over the edge of the platform on to the track, exactly in the path of the oncoming train. By a piece of good luck, instead of falling across the metals, I fell in between them, so that the train rolled over me without doing me the slightest harm. As soon as it had come to a standstill, I climbed up on to the platform again; but all my attempts to trace my assailant were quite in vain. In the fog and the darkness no one had seen him strike me, and I myself could give only a very vague description of him, since I had never even caught a glimpse of his face.

That was on December 12th," George Wayne went. on. Twenty-four hours later, soon after dusk on the evening of the 13th, my sister Brenda was shot at from behind a thick hedge as she was returning home from the village, which is not much over a quarter of a mile from our cottage. The shots—two were fired—both missed her, and the scoundrel who had fired them took to his heels when he heard someone approaching, and got clear away in the darkness."

The End of the Story - An Anxious Life - A Fruitless Hunt.

THERE was silence for a minute or two after George Gilfayne had finished speaking—a silence during which the detective scanned in turn the face of each of the three cousins.

"But you have not told me," he said at last, "how it is that you come to be living here in this out-of-the-way place, and surrounded by so many precautions?"

"That was my idea in the first place," Oscar Neville replied. "You can imagine, Mr. Blake, that it was not long before we came to the conclusion that these various attempts against our lives were all part of one deep-laid plot; a plot whish has for its object the destruction of some, at least, of the heirs of Joseph Gilfayne. And as we never knew who would be the next victim of the assassin's cunning, or whence the next blow would fall—as the police utterly failed to help us-I suggested that the best thing to do would be to band ourselves together, secure a house standing by itself in a lonely district, and cut ourselves off from the world for the time being—in fact, live in a state of siege until January 1st next."

"Then you believe that the danger will be over on January 1st?"

Neville nodded.

"We do," he said sternly. "We believe that the danger will be over when once our great-uncle's money is divided up amongst his heirs."

"Ah, I understand!" the detective said quietly. "Your theory is that it is one of the five heirs to your great-uncle's property who is trying to increase his own share of the inheritance by lessening the number of those who are to divide it with him? "

"Yes," Neville returned, while his two cousins nodded silently; "that is our theory—and I do not believe any other conclusion is possible, Mr. Blake. No one has anything else to gain by our deaths, and the wording of Joseph Gilfayne's will is explicit—the money is to be divided equally amongst those of his brother's descendants who, on January 1st next, are alive to claim it. The fewer who are alive on that date, the larger will be the share of those who survive. That is clear enough."

"Certainly," Blake agreed. "But there are other things to be taken into consideration. You said Mr. Gilfayne left his property in the hands of trustees. Are you sure that these men have discharged their trust honestly? If not, it would certainly be to their interest not to render an account Of their trusteeship on New Year's Day."

Oscar Neville shook his head.

"We thought of that, Mr. Blake. and the trustees them selves, who are men of unimpeachable honesty, seeing that suspicion might be directed towards them, insisted upon making a full statement of the manner in which the property was invested. No fault can possibly be found with their management of it. No; the criminal must be looked for amongst those who are to benefit by my great-uncle's will—that is to say, among the five persons who during the last week have been living together under this roof, So far he has outwitted all attempts to discover him, and he has even been cunning enough to make it appear that he shares the perils of those he is trying to destroy."

"I see," Sexton Blake returned. "Then, besides cutting yourselves off from the world outside, you are constantly keeping watch upon each other."

"Yes." George Gilfayne replied. "Since we came here. just a week ago, we have been constantly on the alert. Two of us always keep watch the whole night through—never one alone, for we dare not trust each other so far. Mr. Blake, you cannot imagine how terrible this strain of constant watching is; how dreadful it is to he always out the look-out for some fresh danger; to be always scanning the faces of your companions—even those you have known and trusted all your life—for some sign of treachery. If I am alive when New Year's Day dawns. I shall thank Heaven, not only for my life, but because this horrible and torturing time of suspicion and anxiety is at an end at last."

The man's face confirmed his words. Unusually strong though he was, it was clear that the strain of a ceaseless suspense was begin big to tell even on his iron nerves.

"In spite of all our vigilance." he went on. "we have not yet discovered the slightest clue to the miscreant, though tonight's work shows only too clearly that he has not yet abandoned the hope of succeeding in his horrible plans. Now, Mr. Blake, you know the whole story, and you understand why it was that we treated you with such discourtesy when you arrived here to-night."

A rough welcome was quite excusable under the circumstances," the detective returned; "for all you knew I might have been the accomplice of your enemy inside the house."

"That was my first idea." George Gilfayne admitted; "ridiculous as it seems now."

"I am going to offer you a bit of advice, if you will allow me," Sexton Blake went on; "and that is that you all three take a few hours' sleep; I can see that you all need it badly; and while you are resting you can trust us to keep watch."

The three men hesitated for a moment; they had been so long accustomed to suspect everybody that, although they had no doubt of Sexton Blake's identity, they found it difficult even to trust him. The detective noticed their hesitation, and smiled as he went on:

"Do just as you like, of course. If you had rather not trust us to prowl about the place by ourselves, I shall not he in the least offended, I assure you. At the same time, you must understand that if I am to undertake this case. I must -undertake it in my own way, and I shall expect to have a perfectly free hand."

"That is only fair," George Gilfayne said slowly.

"At present," Blake went on, "I am in the same position as yourselves—I suspect everyone and no one; but I hope and believe that if von allow me to follow out my own methods unhindered, I shall he able to lay my finger upon the guilty perty before many days—perhaps before many hours—are over."

"I sincerely hope that von are not mistaken, Mr. Blake." Oscar Neville said, with a heavy sigh. "I, for one, am quite ready to place myself under your orders."

"And so am I," Kenneth Brant exclaimed eagerly; while Gilfayne also nodded his assent.

"Very well," the detective said, smiling; "then my orders are that you take as much rest as you can to-night, and hand me over the keys to the various doors, as I intend to make a thorough exploration of the house at once. Before you go, however, there are one or two questions I should like to ask you. The first is, how came you to fix on this particular house?"

"We put an advertisement in the daily papers," Gilfayne replied, "stating that we required a furnished house right in the country which we could enter into possession of immediately. We received replies from several house-agents, and as this sounded the sort of place we wanted, we decided to come here as soon as the bargain was settled. We all travelled down from London exactly a week ago."

"And no one except yourselves has entered the house from the time you took it?"

"No one except my cousin Felix's valet Morton, who came down with him and left the next morning."

"That was the man who saved his life?"

"Yes, He has been with Felix for some time, and nursed him through a long illness. Felix. who is able to do very little for himself, was most unwilling to part with the man, and wanted to allow him to remain here with him; but, having talked the matter over, we came to the conclusion that no one but ourselves must be allowed in the house. As Felix was out of health, Morton travelled down with him, and left in time to catch the first train in the morning."

"Exactly. And you hold no communication even with tradespeople?"

"No. We brought down a stock of provisions from London—quite sufficient to last us till the New Year—so as to avoid having any dealings at all with any human beings. Until you arrived to-night the only person who has been near the house was the postman."

"Thank you," the detective nodded, "that is all I wanted to know to-night. except that I should be glad if you would show me where your various bed-rooms are. By the way, you had better change yours, Mr. Brant—you may as well take ours for to-night as Tinker and I shall have no use for it at present."

Accordingly. Kenneth Brant took possession of the room which earlier in the evening had been allotted to Sexton Blake and Tinker, but which during the last hour or so had been occupied only by Pedro—whom the detective now released and brought down to the sitting-room.

"Well, sir, and what do you make of it all?" the boy asked eagerly, as soon as they were alone.

Sexton Blake shook his head thoughtfully.

"At present I'm in the dark, Tinker. The only thing we can do to-night is to make a thorough examination of the house. To-morrow night we may learn something if those signal-lights that we saw to-night are repeated."

Tinker nodded.

"I noticed that you didn't mention that we'd seen them," he said.

"No: we've got to suspect everybody for the present, and, therefore, to take nobody into our confidence. Those lights make it clear that one of our five hosts has an accomplice outside, and if we can lay our hands on that accomplice—as I intend to do before another twenty-four hours are over—we shall probably lay hands at the same time on the clue to the mystery. Meanwhile, here are the keys, and we had better reconnoitre—it is possible that we may find something that will put us on the right track."

But in this expectation they were doomed to be disappointed. The closest investigation failed to reveal any clue, even the slightest, and, having practically examined the whole place from garret to cellar, they returned to the sitting-room—-glad of its cheerful warmth after the cold atmosphere of cellars and corridors. Tinker curled himself up on the sofa in front of the fire and was soon asleep. but there was little sleep that night for Sexton Blake. Until the first cold rays of dawn began to peep in at the window he sat staring intently at the fire, his head resting upon his hands and his brow wrinkled in thought.

The Explosion - Tinker's Narrow Escape.

SOON after eight o'clock in the morning the household was astir. The first to enter the sitting-room was Brenda Gilfayne, who came up to the detective with her hand outstretched.

"Mr. Blake," she said frankly," my brother has just been telling me who you are, and also of your kind offer to help us. I feel we owe you a humble apology for the discourteous way we received you last night." _

"Please say no more about that, Miss Gilfayne," the detective said kindly, while he noted the intense pallor of he girl's face and the dark rings round her eyes, the result of sleeplessness and anxiety. "If I can help you be sure I will—and I believe I can. So keep up your courage and hope for the best."

The girl smiled faintly as she turned to busy herself with laying the table for breakfast—a task in which Tinker promptly offered his assistance. One by one the other members of the household put in an appearance—and one by one Sexton Blake scanned their faces with his keen eyes for some sigh of guilt, and in each case had to confess himself

baffled. Of Kenneth Brant's innocence he felt certain; it was impossible to suspect his narrow escape on the night before of being a put-up job. Which of those four others was it then. Who had flashed the signals to an accomplice on the hillside? Surely not the girl, the detective thought, as be watched her pale, nervous face, which lit up when one of Tinker's sallies made her forget her troubles for the moment. To imagine that such a gentle. sweet-faced woman would take part in a horrible plot, which had greed and murder for its object, was almost ridiculous. That, being the case there remained only the three other men, Oscar Neville, George Gilfayne, and the crippled Felix. Yet the stories of the former two had both rung true—their voices had the note of truth in them, and their faces bore unmistakable signs of continued anxiety. As for the cripple, Blake would have dismissed the idea of his guilt at once, so frail and helpless did he seem, had it not been for the certainty that the criminal, whoever he was, was acting with the aid of an accomplice. Yet, even remembering that, the detective found it hard to reconcile the idea of deliberate murder with the invalid's gentle manners and patient expression.

"It's the most puzzling problem I've had to tackle for a long time," he said to himself. "I fancy to-night will solve it once for all, and I suppose I must wait in patience till then."

While Sexton Blake was taking stock of his hosts, Tinker and Brenda Gilfayne were bustling to and fro, putting on the kettle and preparing the morning meal.

"I see we want some more coals," the girl said, as she shovelled all that remained in the coal-box on to the fire. "Will one of you fetch them up "

"I will." Tinker replied readily. "I know where the coal-cellar is."

And picking up the empty coal-box and a candle from he mantelpiece he ran downstairs to the basement, which he and the detective had thoroughly explored a few hours before.

"Your friend is bent on making himself useful," Brenda Gilfayne said to the detective, when Tinker had vanished. "It is a shame to let him do all the work when he must be so tired."

"I am sure he is only too glad to help." the detective replied. "And as to being tired, Tinker and I are both used to doing without a night's rest now and again—Good heavens, what is that?"

He broke off and started to his feet as a sudden dull roar filled the air, while at the same time the windows rattled violently, and from garret to cellar the house shook as if in the throes of an earthquake.

With white, questioning faces the five occupants of the room stared at each other for a second; then Sexton Blake dashed for the door with Neville, Brent, and George Gilfayne at his heels.

"Tinker, Tinker, lad, what has happened? Where are you?" the detective cried, as he tore down the stairs. There was no answer but as he reached the head of the steps leading down to the kitchen a heavy cloud of smoke came curling up into the hall.

"Fetch a light—quick " Blake shouted, to those behind him, as, without an instant's hesitation, he plunged down the steps. The basement was in utter darkness, for the windows on the lower floors were all heavily shuttered, add Tinker's candle had, doubtless, been extinguished by the force of the explosion, for not a flicker shone through the gloom as the detective groped his way down the steps and along the flagged passage leading to the cellar-door. So thick were the stifling fumes that before he had gone very far the detective, afraid of being overcome by them, had to halt and tie a handkerchief over his mouth and nose; thee he pushed on again, and he had, as he judged, almost reached the cellar when he stumbled over a figure lying in a huddled heap on the stone floor. Bending down he gathered the lad into his arms and dashed back along the passage and up the stairs, reaching the hall just as Oscar Neville came hurrying towards him with a candle.

Sexton Blakes gathered the lad into his arms and

dashed back along the passage towards the stairs.

"What has happened? Is be much hurt?" the three men asked anxiously.

"I can't say yet," the detective replied between his teeth, as carrying the helpless boy in his arms he pushed past them, and hurrying into the sitting-room, laid Tinker on the sofa. The lad's free was deathly white and blood was trickling from a cut in his forehead, while his clothes smelt strongly of singeing. Brenda Gilfayne uttered a cry of horror.

"Some water, please. Miss Gilfayne—at once! Ah, thank Heaven!"

For Tinker had stirred and uttered a groan, and the next moment, as Blake held the water to his lips, he opened his eyes and stared round him in a bewildered fashion.

"It's all right, sir," he said, smiling faintly; "don't you worry. I don't think there's any bones broken: 1 shall be all right in a minute or two."

He took a long gulp at the water and then pulled himself up into a sitting position on the cushions. Blake drew a long breath of relief.

"No, I don't think there's much harm done," he said, "but tell me what happened, Tinker? There was an explosion—"

"I should think there was," the boy said, interrupting him. There was an explosion, and a mighty fine one it was as far as my recollection goes. I thought the whole house was coming down about my ears, and then I felt myself lifted off my feet and banged against something—a wall, I suppose—and I don't remember anything else."

"But what caused the explosion?" George Gilfayne asked.

"I'll tell you exactly what happened," the boy replied. "As you know, I went down into the cellar for some coal. I put down the coal-box on the floor and the candle beside it, and as the coal was in pretty big chunks I took up a hammer that was lying in a corner, meaning to smash up the blocks with it. I set to work on one big chunk, gave it a couple of good hard thwacks—and then as it spluttered there was a blaze of light and a roar that nearly deafened me. The whole place seemed to rock, and I was lifted off my feet and hurled through the air backwards. I had just time to think that I was done for, and then came a tremendous thump, and I didn't know any more till I opened my eyes again and found myself here."

"You must have been blown through the open door in the cellar into the passage," the detective said, "for you were lying outside the door when I found you. You've had a narrow escape. It's lucky you got off with a few bruises and a scratch or two."

Tinker nodded.

"Next time you're getting a load of dynamite, Miss Gilfayne," he said cheerfully. "if you will take my advice you won't have it stacked with the coals. They don't seem to mix well, somehow."

"You see, Mr. Blake," George Gilfayne said bitterly, "our enemy is at work again. The time is drawing on. There are only three more days till January 1st. He knows he must strike soon if he is to strike at all."

"Well. I say this for him—he strikes pretty hard when he does strike," Tinker rejoined, ruefully rubbing the back of his head on which a lump the size of an egg Was rising.

Sexton Blake made no reply. Taking up the candle which Oscar Neville had blown out, he re-lit it and once more descended the stairs to the cellar. The heavy clouds of vapour had began to disperse, and the atmosphere of the basement was quite bearable when the detective entered it. Some of the coal which had been spattered about the cellar by the force of the explosion was still smouldering, and Blake's first action was to fill a pail of water at the scullery tap and pour it over the smoking fuel. That done, he set to work to search for some remains of the infernal machine which had so nearly proved fatal to his assistant. Nor was it long before he made a find in the shape of a torn and twisted fragment of tin—all that was left of the metal case that had doubtless contained the explosive. Examining it carefully, he noticed that a small piece of wire was still hanging to it, and after a careful search he discovered a similar piece of wire protruding from under a piece of coal. He attempted to pull it out, but failed, and moving the coal away he discovered that the end of the wire was tightly wound round a large brass-headed nail that had been driven firmly into a chink in the cellar flooring.

"H'm." he muttered to himself, "the scoundrel was evidently determined to leave as little as possible to chance. It is easy enough to see why he took the precaution of nailing his infernal machine to the ground. If anyone saw it lying amongst the coal, and tried to pick it up, and tugged sharply at the wire, the jerk would probably be quite sufficient to explode the bomb. It strikes me that I have a very clever scoundrel to deal with."

Sexton Blake did not leave the cellar until he had assured himself by long and careful search that there was no second infernal machine concealed anywhere about it. Having completely satisfied himself on that point, and also ascertained that no other clue to the assassin's identity was to be obtained in the cellar, he washed away the traces of his search and once again mounted the stairs to the upper part of the house.

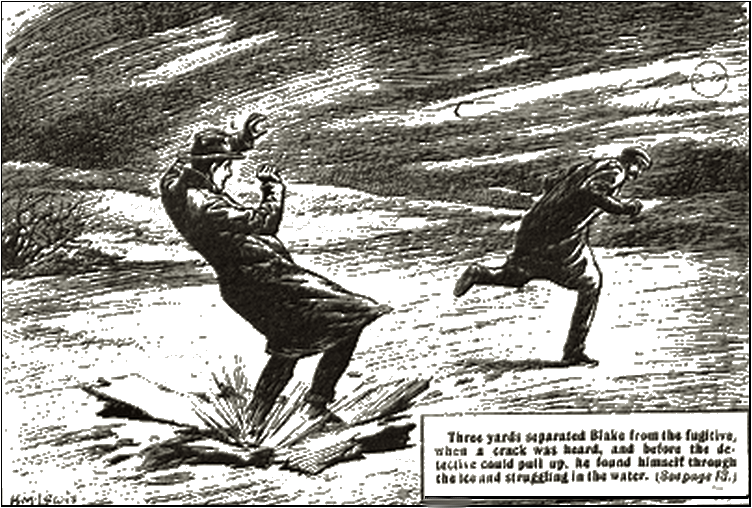

Blake's Expedition - The Mysterious Stranger - A Struggle in the Snow.

THE rest of the day passed quietly enough. The keenest watchfulness on the part of the detective failed to find anything suspicious in the conduct of his five hosts, who on their side seemed to be occupied in distrustfully watching each other. The terrible strain was evidently telling on them, and especially on Brenda Gilfayne, who started and shivered at every sound.

By Blake's advice Tinker went early to bed, and soon after ten Blake himself bade good-night to the household and entered the room where Tinker was already sleeping soundly. Taking care not to rouse the boy, Blake flung himself, carefully dressed, on his own bed, closed his eyes, and soon was fast asleep—to wake, as long habit had taught him to, at the moment he wished, just as the clock on the mantelpiece was chiming the hour of midnight. Crossing the floor quietly, he laid a hand on the sleeping boy's shoulder.

"Time to turn out. Tinker," he said; "move as softly as you can. Kenneth Brant and George Gilfayne are on the watch to-night, and I don't want them to hear us."

"Right you are," the boy whispered back as he tumbled out of bed and began to slip into his clothes.

While he was doing so Blake donned his overcoat and twisted a thick muffler round his neck.

"We're going out, then?" Tinker asked.

"I am," the detective replied. "You've got to stay here, Tinker. I trust you to find out who flashes the signals from the window while I go in search of the gentleman who signal from outside. Of course, its quite on the cards that there may be no signals to-night at all; but we've got to chance that, and I expect myself that two accomplices communicate with each other every night. Now, what you are to do is this. The signals, as you know, were flashed last night from a window at the end of the passage. Close by that window there is a cupboard; it is empty and, as I took care to see before I came to bed, unlocked."

"And I am to take up my quarters in the cupboard and keep my eye on the window?"

"Exactly. If anyone does leave their room and come down the corridor to the window, you can't fail to see them, You must be careful, though, to get to the cupboard unseen. remember that Brant and Gilfayne are sitting up and on the alert for the slightest sound."

"Trust me," Tinker nodded. "It's early yet, though, only a few minutes past twelve, and it was after two last night when we saw the lights."

"I know that; but we'd better be too early than too late, though I expect the signals are always made at the same time. Besides, I must leave myself plenty of time to get over yonder and find cover before the fellow arrives, so I shall be off at once."

As he spoke the detective gently raised the window and glanced over the sill at the ground below.

"A couple of sheets will reach far enough." he said, as he pulled the coverings of the beds and began to knot them firmly together. "Haul up the rope when I'm gone in case anyone should look out and spot it. If you see nothing, wait till four o'clock, and then slip back into the room as soon as you can do so unobserved. If I have been equally unlucky. I shall be under the window by that time. and you can let down the rope to me."

"Very well," the boy replied. "But what am I to do if I spot someone coming to the window—rouse the house or say nothing?"

"Say nothing till I come back," the detective replied as he knotted his improvised rope to the end of one of the beds. "I hope when I do come back that we shall hold all the threads of the conspiracy in our bands: but till we are sure of that, hold your tongue. Now, then, I'm off."