RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

WHIRR-R-R! Ting, ting, ting!

The telephone-bell buzzed viciously, and Blake laid down his morning paper, with a sigh.

A telephone can be of great convenience, but at times it ran be also a very carefully disguised blessing. Blake had been looking forward to a quiet, undisturbed week-end in the garden. The impatient ringing warned him that he would get nothing of the sort.

"Hallo!" he said resignedly, taking up the receiver.

"Hallo!" came the answering voice. "Who's that? That Mr. Blake—Sexton Blake? Ah, that's good! There's been a burglary at Medway House. The men got away with a valuable picture—Gainsborough's 'The Graces'—worth about ten thousand pounds—hacked it clean out of the frame. Can you take the matter up? Any fee you like. What's that? No, nothing. They took nothing else at all. No, no clues. All the doors and windows fastened as usual. Not a sign or a mark anywhere. Will you come and look into it? You will? Capital! Expect you about, lunch-time, then. Good-bye!"

Blake sighed again as he rang off. He had no wish to go, but he felt he ought to; and stolen pictures generally prove more interesting cases than the ordinary stolen plate or modern jewellery affairs.

Moreover, this particular case promised especially well from Blake's point of view, inasmuch as it was the ninth of its kind in four months. In each case the victims had been collectors or possessors of famous pictures or objects of art, and in each case nothing else but the pick of the collection had been taken.

The accumulated value of the objects stolen was well over sixty thousand pounds, yet no attempt had been made, so far as was known, to realise them; and in no case had the thieves left the slightest clue.

These facts, to Blake's mind, indicated that the thefts were the work of a gang or syndicate with considerable means behind them and that somewhere, possibly at one of the best-known restaurants or motels, there was a centre of organisation.

For few places are so safe, or offer so many opportunities to the swell mobsman as a big London hotel, where there is a constant coming and going of all sorts and conditions of men; and much information can be picked up by an individual who knows how to use his ears. Blake reached Medway House shortly after noon, and proceeded straight to the scene of the robbery.

The Gainsborough—or, rather, its frame—hung on the left of the big picture gallery, which was also used as a ball-room.

The canvas—a large one, roughly eight-foot by ten—had been neatly cut away from the massive gilt frame—so neatly that there was not a jagged edge visible anywhere.

Blake, examining carefully, was of opinion that the instrument which had been used was a heavy-bladed razor, and, after a careful scrutiny with a lens, he came to the conclusion that the thief or thieves had worn gloves to prevent a possible detection by the finger print method. The house, as all Londoners know, stands by itself in Park Lane, with a narrow strip of garden running round three sides and a semi-circular drive in the front.

An enormous barrack of a place viewed from the outside; a treasure house of priceless curios when seen from within.

The Gainsborough, from a purely commercial point of view, was undoubtedly the gem of the collection, and that—and that only—had been taken. A big canvas, cut from its stretchers and frame, can be rolled into a surprisingly small compass, and that was possibly one reason why the thieves had chosen it.

The ball-room, when not in use, was generally kept covered up, and the big doors locked and bolted. It had not been used for over a week previous to the discovery of the robbery; the numerous other sitting-rooms affording more than ample accommodation for small informal parties. Had this not been so, Blake would have decided that the robbery was the work of an accomplice in the household.

But it was quite possible—seeing that whoever had done the actual cutting must have been an expert—that a man knowing something of the house might have obtained access to the roof the night after the ball, and lowered himself into the gallery through one of the big top lights; in which case he would have completed his task at his leisure, and waited, if necessary, till darkness fell again to effect his escape.

A cursory inspection of the roof showed traces of recent footsteps, but these Lord Medway informed him were probably the marks left by a party of men who had been employed on repairs to the leads. Moreover, none of the footprints were in the immediate vicinity of the gallery lights.

Like all other burglaries of a similar class there was absolutely no clue of any sort or kind. The picture had been cut out of its frame and removed, and the Medway House collection was the poorer by something like ten thousand pounds, and that was all.

Blake's weariness soon left him on finding himself confronted with such a problem.

The very difficulty of the thing piqued him and put him on his mettle. Lord Medway, who had mot him before, looked at him askance, with rather a rueful smile.

"What do you make of it, Mr. Blake?" he asked at last. "I fancy that if I were to offer you a couple of thousand to a shilling against the recovery—at any rate, say, within ten years, or until they try to deal with the picture—I shouldn't be over-stating the odds."

Blake drummed on the table with his long fingers pensively.

"I tell you what I'll do, Lord Medway, if you want to have a sporting bet. I'll lay you a level five hundred pounds that I get the picture and the man within a month, and if I lose I'll charge you no fee into the bargain."

Lord Medway looked at him in surprise.

"I'll take you, though I think the advantage is all on my side. Any conditions?"

"I want the afternoon to myself in the gallery, and freedom to come and go as I please in any part of the house."

"By all means; of course. Anything else?"

"One thing—when I said the picture and the man, I should have said the man or woman who is at the head of the whole concern. The brain behind it all; not so much the actual thief, in this particular instance, who is probably a mere unimportant cypher."

"I would prefer that unimportant ciphers would give up annexing my pictures to the tune of ten thousand," said Lord Medway drily. "If I make our bet two to one, a thousand against your five hundred, can't we have the cipher thrown in? I feel vindictive, you see."

Blake shrugged his shoulders.

"As you please," he said. "I think I'll get to work at once and start with the gallery again."

When he got to the ball-room he locked the doors behind him to ensure privacy, and, drawing up the blinds, let in a flood of light through the window overlooking the park.

Then he drew an armchair up in front of the empty frame, and sat down to think the matter over quietly, with the aid of a cigarette.

"The first thing," he said to himself, "is how did the thief or thieves manage to get at the picture?

"The top edge of the canvas is a good eleven feet from the floor, nearer twelve, and a step-ladder is out of the question. Obviously a chair and a table must have been requisitioned. They would have been chosen strong for the sake of steadiness, and as light as possible, so that they could be moved without noise. Now, let's look round and see what there is to be seen.

"Humph! Wonder which I should choose under the circumstances. Certainly not a padded chair. It would be too unsteady. One of those gilt cane affairs looks more likely."

He rose from his seat and examined them carefully one by one. They were of the heavily-gilt cane-bottomed type common in mid-Victorian drawing-rooms, and Blake noticed with satisfaction that they had been recently done up.

There were, perhaps, a score of them in the room, and on the fifth he found an undeniable impression of a heel on the heavy gilding of the woodwork of the seat, and the cane part of the seat was slightly indented near the centre, as though it had been pressed upon for some considerable period by a hard object. Closer examination revealed the curve of the side of a heel.

Blake set the chair aside; the mark might have been made by a careless servant when trying to dust something out of reach. He continued his examination, and on one more chair—and only one-he found similar markings, but fainter, and repeated in half a dozen places.

"Heaven bless the gilder's art," said Blake: "but why two chairs?"

He surveyed his surroundings with slow deliberation. Opposite him, between two windows, stood a high Buhl cabinet. He regarded it thoughtfully for a moment, and shook his head—it was far too heavy a piece of furniture for one man to move.

There were tables in plenty, mostly of the Empire period, but he passed them over. He knew what he was looking for now, and he found it. It was an old-fashioned, and, if the truth be told, very ugly piece of furniture of the Victorian era, commonly known as a "what-not."

It had three square shelves—one low down, another half-way between that and the top.

The shelves were of dull walnut, three-foot square, supported at each corner by thin but strong uprights, also of walnut, tinted and gilded in the hollows. As a piece of furniture it evidently didn't think much of itself, for it was hiding away in a remote corner of the big room.

It was between four and four and a half feet high, and—as in the case of all the other tables and cabinets—the ornaments had been removed.

Blake tested its weight. It was light enough to be carried with ease, and rigid enough to bear any ordinary man with safety.

He picked it up, and took it to the window. On the top shelf were four marks unmistakably made by the legs of a chair. Also other scratches made by feet moving.

He tried his first chair; the legs fitted the marks exactly. He moved the what-not, and the two chairs to beneath the empty frame, and tried the experiment. The first chair he placed on top of the what-not, the second beside it to act as a step.

Suddenly he stopped—in a flash he saw that the canvas had been cut by a woman—no man of average height and reach would have needed the first chair at all. It would in fact, have been in his way. He could have done his work from the top of the what-not itself. Blake replaced the furniture as he had found it, took careful drawings and measurements of the heel imprint, and left the house—taking some pains to avoid Lord Medway.

A SMART-LOOKING, elderly manservant, clean-shaven, with iron-grey hair, carefully brushed, stepped out of the train at Waterloo, three or four days later.

He was typical of his class, quiet in manner, very neatly dressed in well-cut dark clothes; over one arm he carried his overcoat, in the other hand was a large brown Gladstone bag, with an umbrella and a buckhorn-handled stick passed through the straps.

And yet, for all his smartness, a shrewd observer might have read signs of hard times.

His boots were as well polished as any pair to be seen in Pall Mall, perhaps better, but the trousers, though creased and pressed, were frayed a little at the bottoms; the velvet collar of the well-brushed overcoat, too, showed signs of wear, and the shirt-cuffs had evidently made the acquaintance of a razor.

He took a tube ticket to Oxford Circus, and having emerged into the open air again, turned down a quiet side street, and stopped before a house, on the door of which was a brass plate bearing the inscription "East's Employment Bureau for Domestic Servants." The lettering was in plain, blunt type, and the house, though dingy, was eminently respectable.

The lower floor windows had screens of wire gauze and the front door stood ajar.

The manservant entered without hesitation; another door opened in the passage just inside on the left, with the word "Office" on it.

He pushed this open, and found himself in a small, dingy room, with benches round the walls; a table in the middle, with some daily papers and a magazine or two; and in the corner a desk, at which sat a sharp-featured, middle-aged man, with a register before him.

For a moment there was no one else in the room.

"Want a billet," he asked abruptly, looking up.

"That's what I'm after," said the manservant.

"Name?" asked the clerk, taking up his pen.

"Johnson—Herbert Johnson."

"Age?"

"Forty-three."

"Fifty's nearer the mark I expect; never mind, you all lie. Been through our hands before?"

"No."

"Humph! Thought I didn't know your face. Our terms are five bob down, ten bob an engagement. What do you want, single-handed or over one?"

"Under-butler, if more than four men kept—or on my own, with two footmen: I won't lake less."

"Hoity-toity! Very well, your highness! Better sit down, and wait a bit; there are papers over there. The boss will put you through it in a few minutes."

A quarter of an hour passed. and at last there came a hum of voices from the passage, evidently some ladies being shown out by another way, and the office door opened, and a head was thrust in.

"Man waiting to see you, sir," said the clerk.

Mr. East, a well-built man, in a frock-coat and the shiniest of top hats, glared at the waiting figure, and nodded.

He was rather florid, with very white teeth, and a general air of good humour, but his little grey eyes were as keen as needles, and he seemed to size the manservant up in a single glance.

"Come to my room," he said. "I've just five minutes to spare."

He closed the door of his private room, sat at his desk with the light of the window behind him, but full on the figure of the man standing before him, hat in hand.

The keen eyes focussed themselves on the frayed cuffs and trousers.

It's easy to see you've been out of a shop for some time," he snapped. "Now—er—Johnson, let's have the truth; I've got to he careful in this business you know. What was it—drink, betting, or what?"

"I don't drink, sir, barring a glass of ale with my meals, and I don't bet."

"How long is it since you had a job?"

"I've had a run of bad luck, sir," said the man a trifle nervously; "times are very hard, as I dare say you know. I've been out for close on six mouths now."

"Last place—sharp, now."

"Under-butler at Lady Maryborough's, sir!"

"Character?"

The man bit his lip.

"Her ladyship's abroad, sir, or I could get one; but that's been my difficulty. I haven't got one!"

Mr. East's eyebrows went up suddenly; he banged the desk with his fist.

"Lady Maryborough's! Why, that's where the gold plate was stolen from—looks fishy, my man. No character, eh!—what?"

The man winced and stammered. "It's true I had charge of the plate, sir, and I'm not denying there was trouble about it, but I had no hand in it. They could prove nothing—er—I mean—I had nothing to do with it."

Mr. East gave the man a long, shrewd look, and pursed up his mouth. Then he abruptly changed the subject, and began a string of questions cross-examining the man as to the doings and movements of many well-known people in the city.

Such questions as servants gossipping with other servants can answer with amazing facility.

"You seem a shrewd man, Johnson," said Mr. East, at last; "ought to make a first-class servant, I should say. Still, that story, and no character, are a bit awkward. Mind you, I make no insinuation. I'm afraid there's nothing just now, but leave your address and I'll see what can be done. Give particulars to the clerk as you go out."

The man had barely left the room three minutes, when Mr. East's door was burst open and a small dapper little man, immaculately dressed, flung into the room.

"Great Scot! Bill," he said, in an excited undertone, "that man who has just left—what have you done with him—did you see him?"

"Turned him down for the moment, but I'm going to keep an eye on him; he may be useful."

"Useful! You all-fired fool! That man's Sexton Blake! It was only by a miracle that he didn't catch sight of me as I came in."

Mr. East leapt to his feet with an oath.

"Curse him!" he said savagely. "Curse him! He's smelt me out."

"Game's up, if he's nosing round," said the small man, and dropped into a chair. "Give me a peg! I feel as if I'd a rope round my neck."

Mr. East's face took on an ugly look as he passed a decanter and glasses.

"Curse the beast! I'll not give up. I'll beat him yet!" He dropped his voice and looked round apprehensively. "There's always Lady Grassdale's to fall back on."

The small man set down his glass with a hand that shook like an aspen.

"You'd never dare," he muttered. "Think of the risk, man!"

East banged the desk again.

"What else am I thinking of, you cowardly idiot! Here's this man comes to me, pitches me a yarn, as good as owns up to stealing the Maryborough plate, and turns out to be that sneaking hound, Sexton Blake! I didn't know; how could I? Risks! Good Lor', what sort of a chance do we stand if he isn't put under? He wants me to get him a situation. By thunder, he shall have one! He shall be Lady Grassdale's butler by this time to-morrow, and dead forty-eight hours after!"

That afternoon Johnson—or, rather, Blake—received a wire.

"Come office to-morrow; chance of a place. Appointment, 12.30. East. "

And Johnson—Sexton Blake—smiled as he read it, for, as a matter of fact, he had seen the small man, and was interested.

MR. EAST was as good as his word. Lady Grassdale engaged Blake—or rather, Johnson—on the spot at a salary of eighty pounds per annum and all extras. She also allowed him liberal beer money, the only condition being that he was to enter her service at once, as she had a dinner-party that night.

Lady Grassdale had a charming house in Wilton Crescent. It was—like herself—small, but perfect, and in exquisite taste. She was a widow, so Johnson was informed by his fellow servants, fond of company, and an easy mistress.

Johnson knew two of the servants by sight, the footman—he had condescended to a place with only one under him, in view of the Maryborough story and the maid; but they did not know him, which was lucky for their peace of mind. Also, on his way to his new place, Johnson had stopped at a telegraph office and sent a wire to Scotland Yard regarding the small man.

The dinner-party was a success. There were some quite genuine and well-known people there; the plate was good, the food and wines above reproach. After dinner mild and inexpensive bridge was played, and after the guests had gone, Lady Grassdale complimented Johnson on his management. He certainly was a most excellent butler.

When he retired to rest he had leisure to think. He was quite aware that every servant in the house was a member of the gang, and that his mistress was Lady Grassdale by courtesy, and Mrs. East by right. Moreover, he had a very shrewd suspicion that he was likely to be "removed," for which reason he slept with a revolver under his pillow.

Another thing that had interested him was that the basement was apparently going to have fresh linoleum laid down, for there was a big roll of it in the servants' hall. He had had no opportunity of getting his hands on it, but he fell into a light doze, betting himself sixpence that inside the roll of linoleum would be found the Gainsborough Graces.

At dinner Lady Grassdale had dropped a casual word or two about running down to tho coast for a sniff of sea air on tho next day but one.

His sleep that night was uninterrupted, and he received a kind word of approval as to the condition of his plate at luncheon time. He accepted the compliment with a deferential bow and a face of mask-like solemnity.

After dinner on the second night he found the footman surreptitiously helping himself to port he cleared away.

"Why don't you take a drop yourself, Mr. Johnson?" said the culprit. "Hands—that's the last chap—he used to take his half bottle every night regular till it came a bit too thick."

"I don't mind if I have a glass, thank you, George," said Mr. Johnson. "Feeling a bit run down, I think. Just pour me one out while I move them flowers."

George, nothing loth, did so; and Mr. Johnson, watching him in the mirror over the mantelpiece, saw him drop something into the glass other than port.

Mr. Johnson murmured to himself. "Sleeping draught!" and took the glass.

"Nice wine, George," he said, smiling appreciatively, and trod on the electric bell-push under run table just by Lady Grassdale's place.

"Drawing-room, I expect," he said tentatively, and took a sip. "Better see, George!"

George opined it was hall-door, and went to see.

Mr. Johnson threw the contents of his glass on to tho carpet under the table and half refilled it. He was just finishing it with evident gusto when George returned, and made a remark about "dratting them blame boys!"

George was rather white and shaky, and helped himself to more port. Blake locked up the house and went to bed.

As he was evidently intended to go sound asleep—why else George and the draught?—he determined to keep specially wide awake; so he lay fully dressed on the bed in the dark with his revolver handy, pondering over three words: "Dover—very early." They had been spoken by Lady Grassdale to her maid, and Blake had heard them when he came up to announce dinner.

It must have been about two in the morning when he sat up gently and sniffed, listening carefully at the same time. There was a faint hissing sound somewhere in the darkness and an unusual stuffiness in the atmosphere.

"Gas," said Blake to himself, and slipped quietly to the floor; "simple and ingenious! I'm afraid [ under-estimated the resourcefulness of my kind mistress and Mr. East."

It would make a very plausible story, and would be well witnessed to. The new butler fills himself up with port, goes to bed, leaving the front door ajar, and doesn't even turn his gas off properly. Sad thing, but the poor chap was dead before they could get to him!

"I rather fancy that that last sentence will be the truest of the lot. Phew! it's getting stuffy here! I must clear out. I suppose they bored a hole in the pipe, and have just pulled the plug out of it. My Lady Grassdale, Herbert Johnson loaves your service without warning, and holds a private opinion that you are a dangerous vixen!"

The gas was becoming unbearable, and he dare not wait; so slipping on a tweed coat and putting his revolver in his pocket, he prepared to take his leave.

As he expected, the door was screwed up from the outside. He tried the window: that, too, was jammed. He ran his finger-tips along the edge; the crevices even had been filled up.

" Needs must when the—I beg your pardon, Lady Grassdale—when you drive! It's as well I was expecting something of the sort."

With quickly moving fingers he opened his bag, pulled out a thin coil of good Alpine rope, well knotted at intervals, and fastened one end to the bed. In the pocket of the bag was a glass-cutter and a lump of adhesive stuff.

With practised ease he had fastened the adhesive to the glass to prevent its falling outward, and so holding it, with his right hand ran the cutter round. A sharp, inward jerk, and the pane was out and lying on the bedclothes.

He was compelled to keep low by now, though, for the gas was pouring in apace, and he only dare breathe as little as possible.

He slipped the free end of the rope through the window and paid it out. A second later he was going down it hand over hand. The houses are not high, and a drop of some five feet from the rope end landed him in safety —just as the policeman on his rounds turned the corner, sauntering leisurely.

In a second the man had grabbed his whistle and clapped it to his mouth. But Blake was on him in a bound, and snatched it away.

"Keep quiet, you fool!" he whispered quickly. "If you want to lose a chance of promotion, blow your infernal whistle! Here, if you don't believe me, take me to your inspector; he will. My name's Blake—Sexton Blake, and I'm indulging in gymnastics for reasons of my own.'

"Come on, then," said the guardian of the peace; "and come quiet, or you'll be sorry."

"So will you, my friend; only hurry up, this is my busy time."

A hundred yards away, as chance would have it they found in inspector coming towards them, and one whom Blake was well known to.

"Ah! Parker," he said thankfully. "convince this lump of idiocy that I'm tolerably respectable; and make him let me go. I'm in the deuce of a hurry."

Half a sovereign changed bands, and the next moment Blake was making for Medway House through the deserted streets.

He reckoned that he had a couple of hours in which to make his preparations, but he calculated without Lady Grassdale, and she was leaving nothing to chance.

White-faced and shivering, but quite relentless, she was waiting in her room listening for any sound from the man she was deliberately doing her best to murder; consequently the rope had not swung twice against the house wall before her quick ears caught the sound, and her quick brain interpreted the full meaning of it.

She realised, too, that the police might see it dangling; if so, the game was doubly up.

In five minutes every servant in the house was collected in the basement which communicated with the stables at the back by a passage. She gave them a few hurried instructions. George and she herself carried the linoleum roll out to the stables.

In under a quarter of an hour her big car—with the linoleum roll hidden by the hood and herself and George—was gliding swiftly towards East's Registry Office.

It passed Blake a little way up Park Lane, and she, peering out from the shadows, recognised him and drew back with an unladylike expression.

By the time Blake had roused Lord Medway and got him to order his big car round, Lady Grassdale, East, and some sixty thousand pounds worth of curios were thirty miles out of London and travelling fast. Blake's one idea was to get to Dover in good time for the early outgoing boat. For there he knew he could catch his prey red-handed. But he did not know that they already had a start of many miles, nor that a neat twenty-ton yawl lay waiting for them in the outer harbour, and had been waiting for weeks.

Had he done so Lord Medway would have been bustled along more than he actually was.

"For heaven's sake, man, explain what we're up to," he gasped, as they at last moved off; "all right, I can drive and talk too, there's nothing about but market carts."

"I've got 'em," said Blake tersely, "and I've got your Gainsborough, too; but as I heard that they were off to Dover early, and knew they meant to motor, my only chance of heading them off and getting a car at this hour of the morning was to rouse you out.

"This is how it is. I found, by marks on the furniture in your gallery, that the picture had been cut out by a woman; from the shape of the heel-marks a woman got up as a servant.

"I went into the details of the other robberies, made a few inquiries, and found, curiously enough, that in every case—sometimes months before, sometimes weeks—a servant had been engaged through East's Employment Bureau, or if not directly, at second hand.

"I had a chat with your housekeeper, and sure enough, she had engaged a housemaid through them six weeks before your Gainsborough went.

"Then, of course, I understood the registry office was really a fraud on a big and rather novel scale; they had some genuine servants on their books, of course, but in the majority of cases they were merely an intelligence department, from whom exact information could he obtained, and who, being for the most part under East's thumb, could be made to carry out orders.

"The curios and other valuables stolen were invariably lowered or dropped out of a window to confederates outside, whilst yet others kept watch further up the street; and so, even if the alarm was given the first thing the next morning, as in one instance it was, searching the servants' boxes would merely establish their innocence.

"Lady Grassdale's was used as a sort of trial trip for those servants they were uncertain about, and she gave several personal characters."

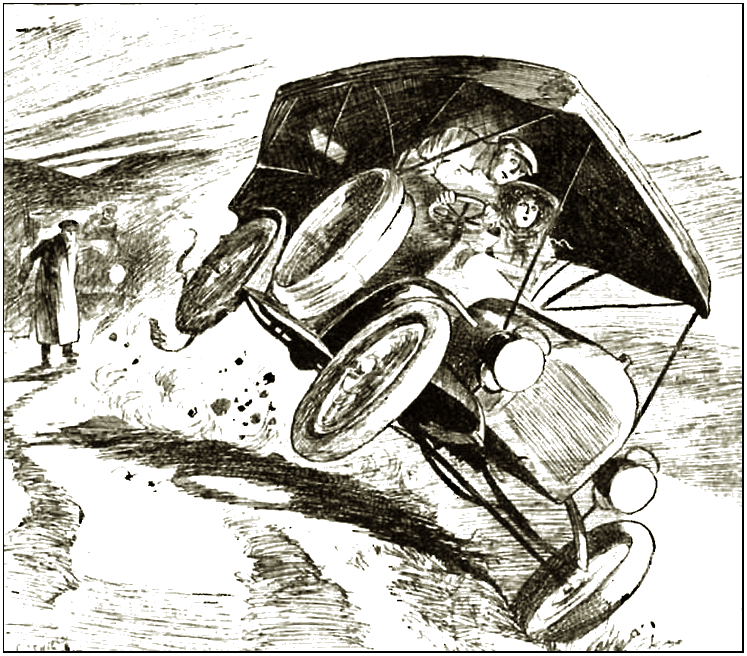

It was not till they were within fifteen miles of Dover that Lord Medway's big car picked up the Easts.

"By Jove, that's them, sure enough!" cried Blake. "I know the car. They were smarter than I thought, though. I fancied we should be well ahead of them."

The end came very suddenly; the big car gained rapidly, and they could easily recognise the face of Lady Grassdale, alias East, peering back anxiously out of the hood even in that dim light.

The big car was barely ten yards behind when, with a jarring, rending noise, she stopped in little more than her own length.

"The gear's gone," groaned Medway, and swore.

One of them ripped as though it had been slashed with a knife, and collapsed, and the car skidded violently. East tried to right it, failed, and caught the bank. His nerve failed him, and he lost control, and the car went over with a crash.

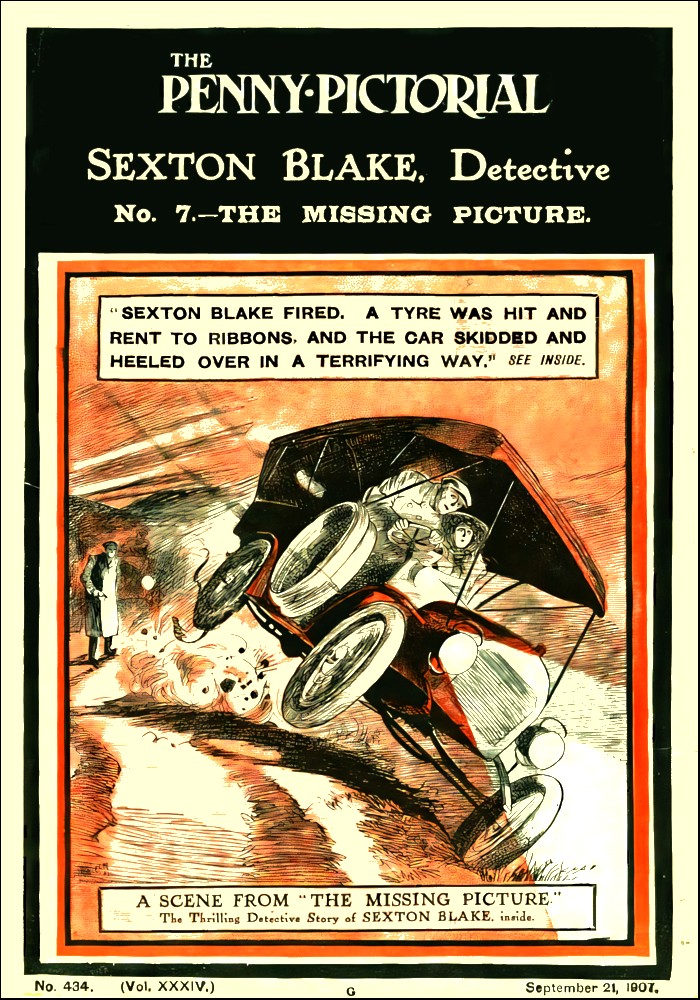

Blake whipped out his revolver and fired at the

back tyres of

the car in front. One of them ripped as though it had been slash-

ed with a knife, and collapsed, and the car skidded violently.

Blake and Medway ran forward. East lay on his back, thrown clear. He was a heavy man, and his neck was broken.

Lady Grassdale had a cut on her cheek, and was unconscious, but did not appear badly injured.

The linoleum roll lay on the grass ten paces away.

"The missing Gainsborough, Lord Medway," said Blake.

"I say, she's a deuced pretty-lookin' woman," said Lord Medway; but he was staring down at Lady Grassdale.

"She was an uncommonly clever one," said Blake. "Ah! here's the rest of the spoils. What a haul they nearly made! By the way, Lord Medway, I've won my bet."

"How?"

"Your housemaid from East's was arrested by my instructions at half-past six this morning; it's striking seven now."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.