RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

SEXTON BLAKE deftly hooked his eighth roach and dropped it in the well of the punt.

He had forsaken his favourites—the flowers—for the day, and was taking a holiday fishing.

The sun was hot; there was barely a ripple on the water; the roach were biting freely, and he was at peace with the world.

He carefully adjusted another lump of paste on the hook and dropped his line into the river. As he did so, by pure chance he glanced upwards at the bridge in front of him.

Whether it was the magnetism of a pair of eyes staring down at him which attracted his own, or whether it was the outcome of that curious subconscious intuitive sense so peculiarly his own, it would be hard to say. The fact remains that he looked up and the first thing on which his gaze focussed was the face of Ourusoff, a Russian from the province of Tver, and a notorious Anarchist. Only the man's head and shoulders were visible above the stone parapet of the bridge.

He wore a rather slatternly slouch hat, and a two days' growth of beard. His collar, a low turn-down one, was not overclean, and his face was of an unhealthy pallor; but the strangest thing of all was that, though he seemed to be staring directly at Blake, whom he had good cause to know well by sight, it was plainly obvious that he did not recognise him and was looking through him rather than at him.

Blake lowered his head at once, and became ostensibly immersed in his fishing. His straw hat came well over his eyes, and from the angle at which the man was looking down at him his face was quite invisible.

But his brain was working at lightning speed, trying to find an answer to the question: "Why should Ourusoff—an Anarchist, a fanatic, a haunter of city slums, a ranter of the purlieus of Soho, a hanger-on at Zurich—be spending his time on the bridge of Staines staring at the water with unseeing eyes?"

The fellow was a man to whom the country was a place of dull monotony, who could only breathe the air of the worlds' cities and their feverish excitement. The sun, the river, and the green trees were nothing to him and his kind. It was clear then, that he was there for some definite purpose—the question was what?

That it was nefarious was beyond all doubt. Ourusoff was one of those naturally distorted creatures, the outcome of generations of oppression, followed by a little hastily-gleaned knowledge; who are virulent pessimists, and have an undying loathing for all men better situated than themselves, to whom laws are an injustice—order, as a red rag to a bull.

Blake missed his strike, tried again, and launched his ninth fish as a car flashed over the bridge above him.

He laid down his rod and took up the morning paper; the passing of the car had set him thinking. Staines is on the road from London to Windsor, and he had an impression of seeing some reference to Windsor in the Court news of the day.

He ran his eye down the column and one paragraph immediately riveted his attention.

A brief thing of three lines announcing that her Serene Highness Princess Constantine was to lunch with the Royal party at Windsor, and would afterwards return to town to attend a gala performance at the Opera.

The Princess was well-known as a keen motorist; the probabilities were strongly in favour of her travelling down by road, and Ourusoff was waiting on the bridge.

Blake glanced at his watch—it was half-past eleven. He pulled up the rypeck, letting the punt drop below the bridge out of sight of the watcher, and made the best of his way ashore.

It occurred to him that if there was mischief afoot, and he was fairly well persuaded that such was the case, Ourusoff would not be acting alone. He would have, at least, one confederate.

The Princess's life had already been attempted twice, and she was known to be rash to the point of foolishness.

He made his way slowly on to the bridge, and found that only half its usual width was available for traffic, a considerable portion of the roadway being up for relaying the gas-mains. This meant that Ourusoff or his accomplices would be able to get close up to the royal motor, which would be compelled to pass within a few feet of them, and being desperate men, with little care of what happened to themselves so long as their plans were successful, the throwing of a bomb would be as easy as tossing a coin, and the destruction of the Princess inevitable.

Blake realised this before he had traversed twenty paces. Ourusoff was still leaning over the parapet looking over the centre span with an air of abstraction.

Blake was within half a dozen yards of him when he turned sharply with a quick, haunted look; his face was livid, and great beads of perspiration stood out on his forehead.

A passing waggon hid him temporarily from view; when it had gone he was thirty yards away, walking as though for a wager.

Blake gave chase, but at a more discreet pace. So long as he could keep his man in sight, and that man was sufficiently scared to keep on moving further and further from the danger point, he was satisfied.

The Russian turned to the left and took a road leading out to a big, flat expanse of grazing ground, known locally as the moor, never once looking behind him. But Blake noticed with apprehension that he kept his right hand constantly in his pocket and that the pocket bulged ominously.

The town-hall clock chimed the quarter to twelve. Blake reflected that the car would not pass the bridge till close on half-past one; he had therefore nearly two hours in which to act.

Ourusoff kept on at a round pace, still without a backward look, Blake following seventy yards or more in the rear.

Ahead, just where the road straightened out, a gipsy caravan was pulled up alongside. The horses were out of the shafts grazing contentedly on the short grass, and a faint wisp of smoke came up from the stovepipe chimney in the roof of the van.

Tho road itself was quite deserted. On the right lay the expanse of the moor; on the left trees and fencing. Blake put on a sprint and closed in on his man, who, on his part, had dropped to a more leisurely pace.

Barely twenty yards separated the two when Ourusoff, heading for the van, scrambled up the steps at the far end, and dived in.

Blake was momentarily at a loss. He had nothing whatever to go on but suspicion. He could make no accusation with certainty, and to invade the van was like forcing one's way into another man's house.

Nevertheless, that was what he determined to do. Ourusoff had had no opportunity to speak to anyone on the road, nor to pass any signal to a possible accomplice. Blake had watched him too carefully for that. Therefore, any assistant he might have was ignorant of this sudden change in his plans.

Sexton Blake determined to use the one available weapon left to him—"bluff"—and try and scare the man into bolting.

He sprang up the van steps, and into the arms of three men who had been crouching behind the door waiting for him.

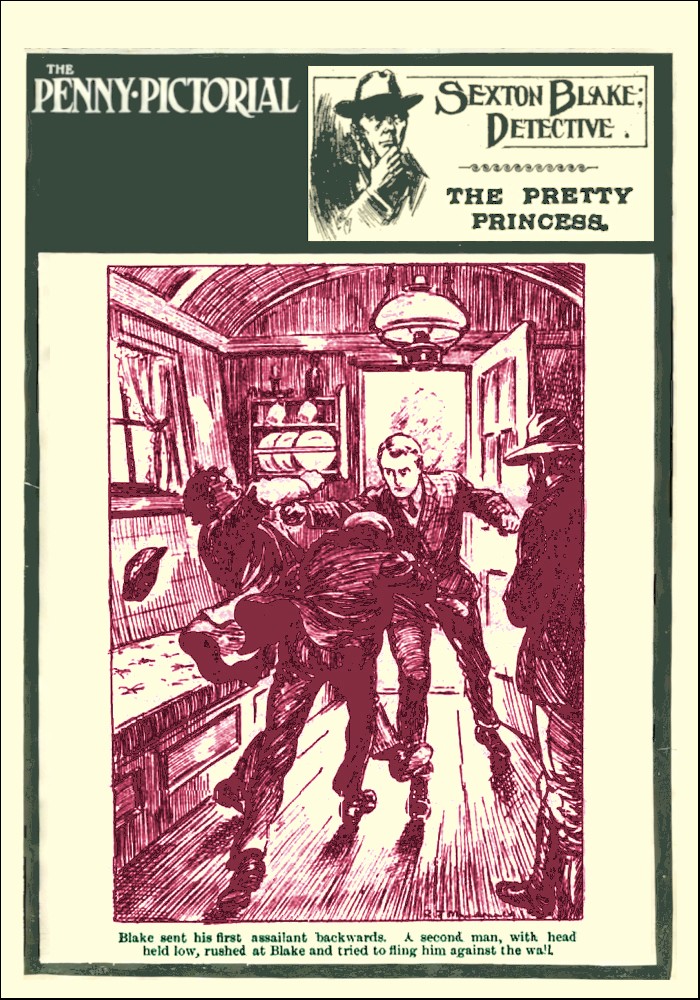

A pair of sinewy arms gripped at his ankles and tried to jerk his feet from under him, and the owner of the arms received two successive half-arm blows which sent him backwards, spitting out teeth and strange guttural oaths.

A second man with head held low rushed him and tried to fling him against the opposite wall of the van. He received Blake's knee in the pit of the stomach and grew suddenly limp.

Blake sent the first assailant backwards. A second man with head

held low rushed at Blake and tried to fling him against the wall.

But the third—Ourusoff himself—was a different matter. He was a burly, truculent scoundrel, but he had wits of a sort.

In spite of his strength he knew that he was no match for Blake. A knife he dare not use; hut he had passed some years of an evil life in New York and Chicago, and had learnt the merits of the sandbag. A terrible weapon—silent, deadly effective, and leaving no definite wound. Just as Blake turned instinctively to deal with him he dodged and brought the thing down with terrific force on the base of Blake's skull from behind.

Had the blow caught him fair and square, it must have killed him outright, though it would have left no especial mark.

As luck would have it, owing to the dim light and the confined space, the heavy bag caught him slantwise.

Even so the shock of the concussion was sickening. Blake reeled forward, his tongue half bitten through, with a vague idea that his neck was broken, and pitched face foremost on to the floor of the van; then consciousness left him.

He came to himself to find Ourusoff sluicing him with water out of a pail.

He was bound hand and foot, and a dirty rag had been crammed into his mouth, half suffocating him.

The gentleman who had lost a couple of teeth was trying also to revive him by the original method of driving a heavy boot toe into his ribs at short intervals.

Ourusoff's pale, unhealthy face wore an ugly leer.

"Well, sneak," he said in broken English, tinged with a Yankee accent. "I s'pose you think yourself almighty smart, anyhow. You look pretty, trussed up there like a fowl, and you'll look prettier before we've finished with you, I can tell you.

"Thought I didn't tumble to your little game when I saw you on the bridge, you infernal spy. Thought you were scaring me away, didn't you. You'll sing another tune to-night before I'm through with you. See that stove there? Well, we'll make that red hot and tie you up to it till you roast, you meddling bungler!

"I'll teach you to come poking your nose into my affairs!"

He put his hand to a shelf behind him and took down a small metal case not unlike a round cigarette-tin.

"See that? That's a bomb, and there are three ounces of picric acid in it. That'll do nicely for the pretty Princess Constantine, won't it. Oh, I don't mind telling you—you're as good as dead already, and dead men tell no tales!

"Look at that pin. When that is struck it releases a spring, and it will take exactly fifteen seconds from that instant to blow everything to blazes, A motor-car travelling in one direction and a man walking, fast in the other will be a good distance apart in fifteen seconds. Yet I shouldn't be surprised if some of the wreckage was to reach as far as the man, even then!"

Blake's face remained an absolute blank—not a muscle moved. He was not going to let Ourusoff have the satisfaction of thinking that he could disturb his composure.

The Anarchist stood scowling down at him, his features distorted with ungovernable hatred and malignancy.

He pulled a watch from his pocket.

"Half-past twelve," he muttered; and then leered as a new idea struck him.

"By the seven, but I've got a better plan. You shall pay for your meddling in a better way. You shall go to heaven by the same road as the pretty Princess, and at the same time. Only you shall have the pleasure of watching your death creep on you, whilst hers will come to her as a surprise.

"Boris, you get outside and smoke. Let me know if anyone is coming along. Franz, give me that rope.

"Lash him down to the floor, so—tighter, man tighter; that's better. Now shove this block of wood under his head and raise it so that he may see. I want him to see!"

The man Franz strained on the ropes till Blake was pinned to the floor-boards, and a rough billet of wood was forced under tho back of his sorely-bruised neck.

"Now, watch what I am going to do, Blake," Continued Ourusoff with a harsh laugh. "Here is another bomb like the one for the pretty Princess—just the same in every respect. I made them, so I ought to know. See, I put it here between your feet, so!"

He lifted the thing gingerly and set it on end on the floor, pin uppermost.

"Now, this piece of candle should burn just about an hour—a little less if a wind springs up, a little more with ordinary luck. We will hope it will be a little more, for that will give you time to hear the first explosion, and take with you to heaven the knowledge that we have been successful.

"I tie this iron weight to this piece of string so, and hang it over the back of tho chair just above the firing-pin of the bomb. The other end of the string I make fast here, as you see.

"Now, we will put the candle on the string and light it. When it burns down to the very end it will set light to the string, which will snap, and tho weight will drop. You will then have fifteen seconds in which to say your prayers.

"No one will come and interfere—there is no chance of rescue—the road is little used, and if anyone should come by, what will they see?—a gipsy van by the roadside and a man—Boris—sitting peaceably by the hedge smoking his pipe.

"Five minutes before the explosion he will get up and stroll away!"

Whilst he was speaking, with deft fingers he was fastening the string and adjusting the weight.

Then he allowed a few drops of melting-wax to drip on the string just near its fast end, and fixed the candle in position.

"You can see quite well, can't you?" he asked, with a chuckle. "It should be an interesting sight to you, watching the candle flare and gutter, and knowing that with its last flicker you will die.

"There will be a blinding flash, a searching shoot of flame, and you and the van will be scattered over fifty yards of roadway. Adieu, my meddling bungler—pleasant dreams! Franz and I go to the bridge to watch for the pretty Princess in her yellow car. Oh, we sha'n't miss it, don't be afraid. The good Franz will be stationed at the corner to give me the signal, and she will have to pass slowly over the bridge. A movement of the hand—so—and the little tin is on the step of the car, so. No clumsy throwing—nothing to attract attention; no one will even see it done. But fifty, sixty, a hundred yards down the road—pouf! and car and Princess and all are in the air! Mr. Meddling Spy, I bid you farewell!"

With a mocking bow and a sweep of his slouch hat he backed out of the van with his companion, closing the half door behind him, so that all Blake could see was the guttering candle, the weight, and a patch of blue sky through the upper half of the door, which was left open. He heard the sound of receding footsteps, and could smell the tobacco in Boris's pipe as he sat a little distance off on the bank. He was conscious of two sensations above all others: a furious anger with himself for having been so foolish as to walk into the trap—he had under-estimated Ourusoff's cunning—and an almost overwhelming anxiety as to the time.

That he could work himself free, he had no doubt. He held learnt the dodge of making his hand smaller than his wrist, and with the loss of a little skin, could slip out of any knot ever tied, but the question was, how long would it take him?

Ho dare not place the time of the princess's arrival later than twenty minutes past one. He must meet her some distance up the road, and Ourusoff's watch had given the hour as half past twelve some ten minutes ago.

Above all, if possible, the Princess must not be told of the danger which threatened her.

He knew her by sight from her pictures, and by reputation, as a headstrong, wilful young woman of obstinate temperament. Moreover, he felt a certain shame in letting a foreign visitor to England know that she had been in imminent peril—it seemed in a way a slur on the country's hospitality.

All the while these thoughts were passing through his head, he was wrenching, writhing, and tugging at the ropes; and the candle, aided by the draught through the open upper half of the door, was guttering and wasting away.

Twice a cart passed along the road, and a little later he heard a man speak to Boris and beg the loan of a little tobacco.

Ourusoff and his men had done their work well, and Blake heard the clock strike the hour before, covered with perspiration and half-suffocating, he managed to get one hand free and pluck the foul gag from between his teeth.

The rest was comparatively easy, and a couple of minutes more found him on his feet, bruised and shaken—but a free man. His first act was to remove the weight; his second to give himself a hurried brush down.

Ho had barely finished this last task before he heard Boris scramble to his feet, obviously with the intention off inspecting the condition of the candle.

He picked up the heavy billet of wood, drew back into the shadow of the door, and waited.

A head came over the lower half. Blake grabbed the loose shirt collar with one hand, and with the other brought the billet of wood down on the man's temple.

He felt the body grow heavy and limp, and, with a heave and a jerk, dragged it into the van and let it drop to the floor. The fellow was stunned, and not likely to move for an hour or more. In any case, Blake had no time to waste on him.

It was a good five minutes to the main street, and every second was of importance.

He ran as hard as he could go, and, to his horror, he heard a clock strike the quarter. He had lost more time than he thought.

He was feeling sick and faint, for the injuries to the back of his head pained him not a little, and his breath was coming in gasps. It was touch-and-go, and if the worst came to the worst, he would have to stop the car somehow and explain, and deal with Ourusoff later.

Just by the station the road branches in a fork, the right hand leading directly to the bridge; the other into the High Street of the town, further up, more towards the London direction.

For an instant he hesitated which to take, and as he did so he heard a big car coming up behind him, hooting at him to clear the road. The next few seconds he says he regards as the luckiest in his life.

He glanced round, and saw a big, grey, shop-finished racing car leaping along at very much more than the speed limit, and recognised, not only the car, but the driver—an enthusiastic amateur named Matthieson.

The recognition was mutual. The car slowed up, and before it had come to a standstill Blake had scrambled, panting, into the vacant seat beside the driver.

"What the deuce——" began the latter. "Blake, man, where's your hat?"

"Drive on, for God's sake!" gasped Blake. "Left hand road—and towards London! Matter of life and death. Big yellow car coming! You must stop it at all costs—collision—anything—but stop it!"

Matthieson glanced at Blake, compressed his lips, and, with a nod, set the big car speeding on her way.

He knew, without questioning, that when Blake spoke like that, seconds were of importance, and that a man of Blake's position doesn't go tearing down country road hatless on a hot day without good reason; also he had the precious gift of silence.

Blake, gradually recovering his breath, gave him the gist of the situation in a few short sentences and the car swung into the main street at a more sober pace.

Matthieson's only comment was a subdued whistle, and an "I'll do what I can." He was a man of iron nerves and used to emergencies.

They swept under the iron railway bridge, and swung off into the London road. A couple of hundred yards away a big yellow car was flashing towards them.

Matthieson slowed down, and kept the centre of the road.

"It's deuced risky," he muttered. "I'll get my license endorsed for a certainty."

With barely twenty yards between the cars he suddenly swept across the road as though to make for a side turning.

The yellow car swerved, and slowed down to avoid him; and he, in turn, seemed to change his mind and return to the straight.

There was a shout and a yell, a jarring of brakes, and a grinding shock, and the grey car's fore-wheel was skilfully manoeuvred under the yellow's mudguard, buckling it badly, and jamming it against the wheel as the two cars locked.

The chauffeur was off his scat in an instant; and a very pretty girl in a chiffon veil stepped from the tonneau and stood by, tapping her foot impatiently.

At last her indignation was too great for silence.

"This is perfectly disgraceful, sir! If you can't drive better than that, you've no right to be in charge of a car! It almost looks as if you deliberately tried to run us down! Is there much damage, Henriques?"

"Alas, Altesse—but yes!" answered the man in French. "I can repair it—yes, but in ten—twenty minutes, not less; and your Highness is already late!"

"Twenty minutes! It is impossible! I would have you know, sir," turning to Matthieson, "that you shall hear more of this! Don't you even know the rules of the road? You were trying to pass on tho wrong side; and I shall take pains to see that the facts are reported to the authorities! As it is, I have a most important engagement, and you will make me unpardonably late by your clumsiness!"

Her anger became her well, and with her eyes flashing and a faint colour mounting to her cheeks, she looked, indeed, a pretty Princess.

Matthieson, who had been making his apologies and a cursory examination of his own car at the same time, discovered, as he had hoped, that it was uninjured; he had judged the thing to a nicety.

"Henriques," said the princess rapidly in French, "go at once into the town to a garage or hotel, and see if you can hire a car and a reliable man."

Matthieson stepped forward, with a bow.

"Madam," he said, "I owe you a thousand apologies; at least let me make what reparation I can. You say you are late for an appointment. My car is fast and unharmed. Please consider it entirely at your disposition. Your chauffeur can drive you; and I will see that your own car is delivered at any place you choose to name as soon as I can get it repaired."

The Princess was vexed, and the Princess was in a hurry. For an instant she hesitated, and then, with a little bow, accepted.

"The importance of my engagement compels me to avail myself of your offer, sir," she said, her eyes still shining. "And that being the case, of course, I can take no further steps in reporting your carelessness."

"Madam, I assure you I shall never forgive myself," said Matthieson, "but I got a fly in my eye, and the car swerved before I could recover command of it. You will find the dust and the flies very bad farther on. Permit me to suggest that you should wrap your veil closer round you. The car is entirely at your service."

"I am obliged to you, Mr.—er——"

"Matthieson."

"I am much obliged to you, Mr. Matthieson; and as every moment is of importance, we will start at once. Henriques, allez vite! I should be glad, Mr. Matthieson, if you would have my car sent on as soon as possible to Princess Constantine at Windsor Castle."

"It shall be there within two hours, your Highness."

Blake helped the Princess into the car; and the two men stood, bareheaded, watching her depart.

"Phew!" said Matthieson,as it turned the corner, "you do get a man into holes and corners, Blake! What next?"

"We'll get that guard off, and run without it for the present. Quick as you can now—round with her!"

"But where are we off to?"

"Back to Chertsey. Across the river there, and up on to Staines Bridge again from the opposite direction, to take Ourusoff and the other blackguard by surprise in the rear. I want to catch 'em red-handed, and. above all, to avoid a fuss."

She's got a temper of her own," said Matthieson reflectively, "I like that 'don't-you-dare-to-answer-me' way that she carries her head."

"If we had told her the danger she was running, and that the brutes were on the look-out for this infernal yellow car, I'm pretty certain nothing but brute force would have stopped her from going on," said Blake. "The risks she ran in Petersburg were appalling. Men like Ourusoff ought to be lynched; hanging's too good for them."

The injured mudguard was wrenched away, giving the wheel free play once more, and the car hummed away towards Chertsey, over the high-pitched stone bridge, up the long street, and away to the right down the winding Chertsey Lane.

"How are your nerves—all right?" asked Blake, with a grim smile. "We must grab Ourusoff at once, before he can get hold of his infernal bomb; and I'm not going to tackle him in kid gloves, either—I don't feel that way."

Matthieson grunted.

"I'd like to break the beggar's neck when I think of that pretty girl!"

They hummed past a small red-brick farmhouse, under the railway, and so on to the dangerous corner at the end of the lane as the clock struck two.

"We're infernally behind time, but they'll be waiting; it's a woman's privilege to be unpunctual."

They reached the bridge just as the last of the factory hands had trooped over, and it was practically deserted. Ourusoff, with his back towards them, was lounging inconspicuously near the middle span, his arms on the coping.

Apparently, he was looking down at the river; in reality, he was keeping an anxious eye on Franz, who was standing at the far corner waiting to signal the car's approach.

They glided up to the pavement edge immediately behind him, and the car had stopped before he turned.

His naturally pallid face turned livid, and his jaw dropped as he caught sight of the car coming from the opposite direction to that he had expected.

Before he could realise what was happening, Blake was on him. It all happened so quickly that the scene passed unnoticed.

Blake got him by the throat with his left hand from behind, and a grip of iron closed on his right wrist—an old ju-jitsu lock.

"Come quietly," said Blake very low in his ear. "If you struggle, I'll break your arm. Matthieson, the bomb is in his pocket—take it out carefully, will you?"

To do Ourusoff justice, he was no coward, and he made a desperate effort to get at his infernal machine and involve them all in a common ruin.

Blake felt the movement.

"You would, would you? Take it, then!" he said grimly. There was a quick jerk, a yelp of pain, and the man's arm snapped backwards at the elbow, and hung dangling and useless.

Matthieson withdrew the bomb.

The sound of Blake's voice made Ourusoff wince even more than the pain of the grating bone; for, so quickly had things happened, that, till that moment, ho had barely realised who his assailant was.

Blake, gripping him by his uninjured arm, thrust him into the tonneau, and sat beside him, as Matthieson gave a low cry of "Gone away!"

Franz had turned when Ourusoff cried out, and promptly taken to his heels, heading instinctively for the road leading out to where the van had stood.

Matthieson slipped in the clutch and gave chase, Casual passers to and fro saw merely a yellow car with a damaged mudguard, with one man driving and two others sitting low in the tonneau close together, and never guessed they had been within an ace of a tragedy.

They overhauled Franz just beyond the outskirts of the town. He made some small show of fight, and was promptly knocked down, upon which he caved in abjectly.

Boris was still insensible in the van, and the horses were grazing peaceably.

They bundled their prisoners into the van, and Blake, having roped them, mounted guard.

"What next?" said Matthieson.

"You'd best take the pretty Princess's car back, and do a bit more apologising," said Blake grimly. "Here, take this card with you—it's for one of the head detectives on permanent duty. Bring him back with you to take over these beauties; and, above all, no publicity. He'll keep quiet—he's a good man, and an old friend of mine!"

Two months later both Blake and Matthieson received a magnificent ruby pin set in brilliants, with a message in French which contained the words "my heartfelt gratitude" and no signature.

They were from tho Princess's father, who learnt the truth through his minister of police.

But the pretty Princess never knew, and considers herself aggrieved, on the question of the accident.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.