RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

THE case of Molly O'Hara shows, perhaps, better than most others, Blake's abnormal faculty of reasoning, and his cold hard, methodical elimination of unessential facts; the reduction of chaos to order, and the crystallisation of small details into a coherent mass.

The disappearance of Molly O'Hara was for days a complete mystery, and press, police, and the hands of the factory where her father worked, were absolutely at a loss.

Put briefly, the story runs thuswise. Molly's father was one of some three hundred hands employed at the branch works of Messrs. Raymond's powder factories, on Larkand Island.

Larkand is an island of some five square miles, flat, marshy, and surrounded on all sides by a high sea-wall or bank to keep out exceptional tides at the springs.

In shape it is roughly triangular, and along the base of the triangle runs the tidal water; the remaining two sides are separated from the mainland by a creek of varying width. This, also, is tidal, and at one point at low water it is possible to drive across with the water no higher than a horse's belly.

The mainland beyond is undulating moor-like down, which stretches away for ten miles across a neck of land to a barren strip of coast.

Larkand is the private property of Messrs. Raymond, and a stranger setting foot on it is a trespasser. The main portion of it is dotted over with isolated sheds and huts, where men in thick felt slippers work in constant danger of their lives—for Raymond's also deal in experimental high explosives, and the sheds are placed, at considerable distances one from the other.

The hands, overseers, chemists, and manager, all live on the island, but on the far corner, removed from the factory sheds. The wharves are naturally on the river front. The position is isolated and dreary in the extreme, but the scale of pay is uncommonly high.

O'Hara, his wife, and their small daughter Molly occupied a cottage facing the sea-wall and backing on to the open stretch of the island. At six o'clock in the evening on Tuesday, the 9th, the child, barely six years old, went out of the back door to play by herself. Her mother was busy ironing,, with one eye on O'Hara's supper, which was being got ready against his return from work.

At half-past he turned up, tired and hungry, and asked for Molly. The mother called the child, but there was no answer, and it was imagined that she had gone off to play with some neighbour's children.

Seven o'clock came—eight—half-past; and still there was no Molly. Mrs. O'Hara began to get nervous, and throwing a shawl over her head, set out to make inquiries.

When she returned it was nearly ten. Not a sign of the child was to be seen anywhere, and Mrs. O'Hara was in a state of great agitation. A search party with lights was organised then and there, and spread out to hunt for traces of her, the neighbours good-naturedly helping. A party of a score or more were out all night, but without any result. Early the next morning no fewer than a hundred hands were abroad as soon as it was light, and gave up a day's work and wages for the sake of the quest.

The whole island was examined foot by foot and inch by inch. The few pools and small streams on it—all shallow—were dragged, and an overseer telephoned early in the morning for the police. Several papers, hearing of the case, sent down reporters, and again the result was—nothing.

The O'Haras themselves were frantic. Molly was their only child, a fair-haired, slim-built girl; and her father, who was in delicate health from a disease, which for years had been sapping his strength, was compelled, much against his will, to take to his bed from sheer exhaustion and want of rest.

The coastguards were called in and dragged the creek without success. It was quite impossible that the child could have fallen in there without her body being found, for where it ran into the main stream at either end it was netted, to preserve the eels, for which it was famous. She could not have forded it, for even at low water it would have been too deep for her, and she was a nervous child into the bargain.

Close to the ford, it is true, there were three or four clumsy boats, for use at high water; but the idea that a frail child of six could have dragged one down unaided and paddled it fifty or sixty yards across a strong tide was ridiculous, and the main stream itself was inaccessible to her by reason of a high iron railing, with upright bars.

The longer the search parties worked the more inexplicable the affair became. A second day and a third passed, and the factory hands took up the task in relays. It was calculated that it cost them nearly £300 in wages alone and loss of time.

At the end of the fourth day no one was a bit the wiser. The child had gone out to play at the back of the house in the dusk at six o'clock on the Tuesday evening, and from that moment onwards, so far as was known, no human being had set eyes on her. She could not have made her way off the island, yet every inch of it had been searched again and again.

O'Hara's fellow workmen had, to a man, ungrudgingly done their best to aid him. Overseers and manager alike had joined in the search, and yet the child had vanished as completely as though the earth had swallowed her.

Her picture was published in several papers and scattered broadcast throughout the kingdom. Her official description had been circulated by the police, and the press had devoted columns of conjecture and theorising to the case.

One suggestion was that the child had been engulfed in the soft mud of the creeks; but though the main stream bank showed a stretch of slimy ooze at low water, at no point in the creeks was the mud more than a few inches deep.

The island was practically treeless, with little or no undergrowth, and such vegetation as there was consisted mostly of tough tussocky grass land, a small portion of the remainder being under cultivation, a solitary farm, also the property of Messrs. Raymond, supplying the needs of the hands as far as possible.

One fact alone remained clear, and that was that on the middle of the fifth day, the disappearance of Molly seemed as great a mystery as ever. Cranks—spiritualistic and otherwise—wrote long letters to the journals, and everything—from necromancy to the infamous practices of the Marquis de Sade, down to the more practical suggestion that the child had been kidnapped—was put forward.

As against these latter it was pointed out that there was an utter lack of any known motive, that the child had never been off the island since the O'Haras first came there five years before; and, above all, as chance would have it, the by-road—the only one on the mainland which passed near the island at all, had been patrolled that night by mounted police, one coming from the east, the other from the west, and the two had linked up and interchanged greetings opposite the ford, the usual demarcation line of the patrol. At this point stands the small hamlet of Larkand, an inn, and some half-dozen cottages, the inmates of which had done their utmost to help the searchers

Blake had seen the case in the papers, at first with little interest, for he imagined the child had merely strayed and would be found within a few hours.

But as the days passed, he began to study the thing more closely—the peculiar circumstances interested him, and when the "Mail" on the fifth morning informed him that the girl was still missing, he packed a handbag and went down to have a look round for himself.

The nearest railway was twelve miles from Larkand village. Raymond's got all their stores and supplies, and made their shipments by barges. He got out at the small station of Drent just after midday, and started to walk.

That same evening he sent his card to Raymond's manager, who was delighted to see him, and learnt what there was to be learnt at first hand, then he paid a brief visit to the grief-stricken O'Haras, and returned to the small inn at Larkand for the night.

Dawn the next morning found him striding across the island with the long, swinging stride of the Swiss guide.

By his special request to Mr. Selvert, the manager, the other searchers had been asked to give him a free hand, and return to their various posts at the works, leaving him entirely unhampered.

This they agreed to do with alacrity as soon as they heard Blake's name; and, moreover, it must be remembered that they had already given up more than half a week's work.

Accordingly, as he strode along the track across the island, the steam-hooter of the factory was already signalling starting-time at the works, and he had the whole place to himself except for a few gulls and a stray curlew or redshank. He already had the facts of the case, so far as they were known, at his fingers' ends; but as his keen glance took in the details of the ground here and there he felt far from hopeful.

Grasses had been trampled down here, there, and everywhere, destroying any possible track. Bushes, what few there were, had been torn and mangled by willing but inexpert searching-parties. In short, the whole, thing looked very much like a forlorn hope.

You can't turn two or three hundred men loose over a small tract of country like five square miles for four consecutive days and nights without their effectually obliterating anything resembling a trail in their eagerness to help a friend in distress.

That the girl had not left the island of her own accord Blake was certain, and that she was no longer upon it—dead or alive—he was equally certain; for it was impossible to imagine that that small army of scouts—to many of whom she was known personally—could have missed her in that confined area. The idea was inconceivable.

From dawn to dusk he tramped Larkand from end to end, and from corner to corner, and back again, lunching frugally on an angle of the seawall off hard biscuit and a gulp of weak whisky-and-water from his flask.

With the coming of darkness he had to confess himself completely baffled. That some story lay behind the thing he was intuitively sure.

The O'Haras themselves were simple folk enough, and the genuineness of their anxiety and distress was beyond all question; in fact, O'Hara was so ill that he had been moved into the works' infirmary.

Blake did not go to bed that night in spite of his long tramp. Instead, he sat by the fire in his room, staring up at the ceiling and smoking cigarettes by the score.

A second dawn found him heavy-eyed and chilled, with a litter of burnt-out grey ashes in the grate, and a pile of bitten cigarette-ends in the plate on the table beside him.

He took not the faintest notice of either, for he was haunted by an elusive idea—the harder he tried to seize it the more nimbly it slipped away from him. He was just in the state of mind of the man who has a familiar name on the tip of his tongue and yet can't quite lay hold of it, even if his life was forfeit.

Blake's memory was more than abnormal; by dint of long training it had become almost uncanny—to such an extent, that if his eye rested casually on a phrase, an object, or a name, he never forgot it completely. And in the small hours it had been borne in upon him that somewhere—not very long ago—he had seen the name of O'Hara in print, in what precise connection he could not say. And in any case, the chances were thousands to one against there being any connection between that O'Hara, and this, for the name was common enough.

Still, it might be a chance link. There was a child's life at stake, and Blake had a capacity for taking pains which amounted to genius. When he was cornered, baffled—as in this instance—no possible hint or clue was small enough for him to neglect.

Also, he had a gift of intuition which approximated to second sight. At Larkand he had tried, and, so far, failed.

He determined to cast about and get on a new scent, and accordingly went back to London on an early workman's train. And all the way, to the throb and jolt of the train, his mind was striving to picture the page or column or advertisement in which the name O'Hara had appeared in print. Just as they pulled into London he brought down his hand with a resounding thump on his knee. He had remembered. It was in a newspaper advertisement two or three months before.

He drove straight to the offices of the paper, and was soon busy with the files. To hunt up an advertisement of uncertain date, the purport and wording of which are alike unknown, is a somewhat labourious task; but Blake stuck to it tenaciously, and that same afternoon he found what he was looking for, and called on the firm of solicitors who had inserted it.

It was a very brief notice, and the word which had caught Blake's eye was the first of the first line in rather bigger type than the rest.

"O'Hara"—it began—"if anyone of that name resident till seven years ago in the village of Merstwith, in Suffolk, will call on Messrs. Wolf & Stern, they may hear something to their advantage."

Within a quarter of an hour he was in the senior partner's office, talking to Mr. Wolf. The firm, it appeared, had been acting on the instructions of a late client—a certain Mr. Mike Regan, who, having been somewhat of a rolling stone all his life, had eventually rolled up to Dawson in the gold rush. There his luck had turned, and he made his pile; and, what is more, kept it, and made another on top of it. But in doing so he contracted lung trouble, brought on by exposure, and didn't live long enough to enjoy his money. He had quarrelled irrevocably with his only son Patrick Regan, who had twice been run out of the Klondyke as a "bad man," and was in trouble with the police. And so old Mike, as he lay dying, bethought him of his nephew—one Denis O'Hara—who had once lived at Merstwith, and been kind to him when he was down on his luck; and he made a will leaving his fortune to this same Denis—or should he (Denis) have married and died in the meanwhile, to his children in equal proportions. To his own son he left a hundred dollars—for a spree, as he added sardonically.

Messrs. Wolf & Stern had inserted the advertisement in several papers, and made inquiries, but so far no O'Hara from Merstwith was forthcoming.

That night Blake returned to Larkand. For all he knew he might be wasting his time on a wild goose chase, but he fancied not; and the morning proved that he was right. For, without mentioning the advertisement, he soon discovered from O'Hara that he had lived at Merstwith,and had, in fact, only moved from there shortly after his daughter's birth.

Blake said nothing to the stricken parents, but he felt that now, at any rate, he had something definite to go on.

Denis O'Hara himself was clearly not long for this world. By the terms of the will, the money, in the event of his death, would go, not to his widow, but to the child Molly. With her out of the way, it must of necessity revert to Patrick Regan, the "bad man."

Here, then, was a motive for the abduction, and a sure guide to the author of it. The problem remaining was to discover the method.

Patrick Regan was likely to prove a cunning man and a nasty one to handle—a man who had been up against the police of various countries, and knew their ways. And Blake felt sure that he would be lying low somewhere till the first rush of the hue-and-cry was over.

His chief maxim in cases of this sort was to endeavour "to get inside the skin of the criminal," as he put it.

Now Regan was a man not only of cities, but of the backwoods and the frontier, who would know how to read trails, to move quietly, and hide his tracks, and, above all, to make his way across an open space without detection by his less observant fellows. That would explain the fact that no one had seen any signs of a stranger on the island.

Again, he would have the patience of an Indian on the trail, and would lie in wait for hours rather than be baulked of his prey.

Blake put himself in Regan's place, and came up against his first difficulty. The man had spoken to no one, questioned no one in the locality, yet alone and in the dusk, he had picked out Molly unerringly, though he could not by any possibility have known her by sight.

O'Hara he knew, and the fact of the child's existence-nothing more. Blake wondered what he himself would do under those conditions. To have discovered that O'Hara was a hand at the works was easy—what next? He cast his eyes on the rolling moorland beyond the creek. A man might lie hidden there for a day—two days, and, with a strong pair of field-glasses, might watch the men going to and fro between their homes and their work. The distance was small, and with strong glasses it would be easy enough to make out a familiar face, and in O'Hara's case, with his flaming red hair, especially so.

He could mark down O'Hara's cottage, see the woman at her work and the girl child at play, and note the times of their comings and goings and their usual routine.

To cross the island unseen at dusk would be a mere nothing to a man with any knowledge of scouting or woodcraft.

Blake took in the contour of the ground. Seemingly flat though the island was, there were many small dips and hollows amply sufficient to screen a man from observation in a bad light, if he moved cautiously.

He followed with his eye the route he himself would have chosen from the creek ferry. He was pretty certain of Regan's line by now, though to look for tracks was, of course, worse than hopeless.

Instinctively he moved along it towards the O'Hara's house, and the spot where he had ascertained she had last been seen playing.

A dozen yards short of it, and some thirty or more from the house, was a small dip in the ground, shallow, and almost unnoticeable, but amply sufficient to hide a man lying flat.

He dropped down into it, and lay at full length. Nothing but sky was visible all around him, and a man might have passed within a yard of the spot, even in that light, without seeing him.

He raised his head cautiously, and peered between two tufts of long grass in front of him.

They screened his head completely, but between their roots he could get a clear view of Molly's playground and the house beyond.

"This," he said to himself, "is where Regan lay in wait," and, turning over on one side, he whipped out a pocket-glass, and began examining the ground in detail.

It had been trampled over again and again by the searchers, as had the rest of the island. But still he persevered, and at last he was rewarded.

In two places, on small fragments of broken root, he found some minute wisps of tow-like material. A glance at them under the glass told him that they were loose strands of coarse sacking.

Ho put them carefully away in a small cardboard box, with a grim smile of satisfaction. He knew now how the child had been smuggled off the island. Regan had noticed that the hands were frequently tramping to and fro with big sacks of saltpeter. It would minimise his risk of detection enormously to carry the child away in a sack, for in the gathering darkness, should he have come unexpectedly across one of the men, the latter would have merely thought him a fellow workman, and a surly good-night grunt would have prevented any suspicion.

Not content, however, he searched on, and found that one or two trodden-down blades of grass were slightly sticky.

He passed his hand across them lightly; then, with more pressure, and finally probed with his finger into the soft earth beneath, moving the grasses aside.

Sure enough, trodden deeply into the mould, was the remains of a half-melted sweet.

It was of the ordinary kind, known as "bull's-eyes," and smelt strongly even still of peppermint.

Blake had little doubt that it had originally been doctored with an opiate, and was one of the packet with which Regan had provided himself, and which had dropped out accidentally, and subsequently been trodden out of sight by the searchers, and partially melted in the damp earth.

He could see the whole scene clearly enough now, the small girl playing all unsuspectingly.

A low-spoken gruff "Have a sweety, Molly? Here, catch!" and the child's eager grab at the opiate, apparently so cheerily tossed to her by a man who called her by name, and was probably a "friend of father's."

Her coming to sit beside him, induced by the offer of a second goody, and the sudden lapse into unconsciousness, whilst all the time the man lay close in cover.

Then, as the darkness grew apace, the hurried bundling of the poor little victim into the sack, and the stealthy creep back to the ferry.

After that——

Blake turned to follow his problematical line, and for the second time his eyes rested on the upland moors.

The man would have known that the only road was patrolled by a mounted policeman at uncertain hours, and in any case it would only lead him to a small village or to Drent, both of which he would naturally avoid. A big town might have hidden Molly, but a stranger with a small girl would have been remembered at once in a village the moment the hue and cry was raised.

The moor and the open would be his safest place to lie up in, and he was a man accustomed to nature's wilds. He would take to the moor from choice.

Blake's mind was soon made up. He returned to the inn, and filled his pockets with good solid sandwiches, plenty of them, and a capacious flask. He was going to take a leaf out of Regan's own book.

He took a rug and his field-glasses, and made his way up on to the highest point on the near side of the moor.

Somewhere out in the big, undulating expanse before him he was sure his man and the child were lying snugly hidden.

To attempt to search it until he had marked him down would, he felt sure, be worse than useless.

Regan was too old a frontiersman to be caught sleeping with both eyes shut. He would have left no trail, and he would see Blake hours before Blake saw him, and be off elsewhere with the first hint of darkness.

Blake knew that he might as well try to trail down a Sioux or an Apache over that open ground as a man like Regan.

Besides, there was always the risk that the man, desperate and cornered, might wreak his vengeance on the helpless girl before he could be stopped.

But Blake had good hopes of setting eyes on the man before long, and for this reason.

He had learnt from a few chance words of Mr. Wolf that Patrick Regan, amongst other pleasing qualities, had taken to drink, more or less as a profession, and, if Blake was right, he had now been on the moor about seven days.

At the start he had probably laid in a stock of both liquor and provisions; but by this time a gentleman with Mr. Regan's thirst, and nothing to do but keep to cover, must have finished his liquor supply and be craving for more.

Sooner or later Blake felt sure that the craving would lead him to ignore the risk, and make for Drent to replenish his stock.

It was merely a matter of time.

A long wait was no new thing to Blake, and he was prepared, if necessary, to mount guard for two or three days at a stretch.

In a small place like Drent the inns close early—at ten o'clock—and Regan would have a good fifteen miles across country to do to get there, difficult country at that.

So he would be compelled to start well before dusk, and that would give Blake his chance.

All that day he rested on his ridge, his eyes glued to his binoculars, and when darkness fell he munched his sandwiches, lit a pipe, and rolled himself up in his rug.

He slept, as only those who know the joy of sleeping in the open can, and with the first hint of dawn he had a perfunctory sluice in a pool, and returned to his post.

The air was fresh, with a biting chill in it, and again and again Blake had to wipe the lenses with his handkerchief to rid them of the moisture which obscured their clearness.

And gradually the mists were swept away, and the whole panorama lay spread out before him like a map.

Crouching low on the ridge, he swept the whole expanse slowly and steadily, examining each rise in the ground, each knoll and hollow.

"In for another wasted day of waiting," he muttered to himself, and the next minute jerked back to cover behind a friendly clump of heather, for he was dangerously near the sky-line, and far away, five miles below, he had suddenly glimpsed a dark speck moving cautiously and cunningly along a shallow gully.

Every now and again it would come to rest against a patch of dark background, and remain motionless and practically invisible for minutes at a stretch.

Then it would vanish absolutely and it would take five minutes' diligent search to pick it up again five or six hundred yards further on.

Never once did it show against a sky-line or a patch of light ground, but kept always to the hollows when upright, and where a shelving ridge had to be crossed it disappeared completely in the dense heather.

It was a fine exhibition of scouting, and none but a highly-trained eye, used to scouts and their method of working, could have hoped to distinguish that small elusive speck.

But it was moving slowly and surely towards Drent by a circuitous route.

Blake had been right.

Regan's craving for strong waters had got the better of him, and he was taking a risk that he himself knew was foolhardy.

Blake took a careful cross-bearing of the spot where the speck had first shown up, and shut his binoculars with a snap and a sigh of relief.

Then he turned to and munched the last of his sandwiches, and, lighting a pipe, stretched himself luxuriously on his back and watched the clouds flitting one by one from the brightening sky.

Regan had a thirty-mile tramp to put in before he could return, but Blake had no intention of moving till his man was far away on his journey and hidden by a far fold of the hills.

He knew that at each rise Regan's instinct would make him turn and scrutinise the ground he had already covered, and he had no intention of running the risk of alarming his man and scaring him away by premature action. It was nearly noon when he made a move, and even then he went warily. There was always the chance that Regan might find the risks too great and return unexpectedly.

He worked his way cautiously downwards, keeping a sharp eye on his bearings, until at last he reached the spot where he had first glimpsed his man. Regan had covered his tracks as well as he could, but heather is tell-tale stuff to the experienced eye, for all its springiness.

Here and there the trail failed altogether over rocky patches, but by making small and constant circles, Blake managed to cut it again further back, and at last he found what he was looking for.

The ground shelved suddenly in a steep, dropping bank, with a fall of some six feet.

The bank itself was partially overhanging, and in this a shallow hollow had been scooped.

A peat roof, following the natural shape of the ground and covered with heather, was supported by three strong uprights, firmly bedded in the soil; the open front was screened by gorse bushes, the sides by the natural formation of the bank.

At five paces the thing was indistinguishable from its surroundings, and a whole army of untrained men might have been turned loose on the moor and passed it unheeding.

Blake approached suspiciously. A log-fall trap, or some similar device, might spell disaster in the very moment of success.

He made his way under the low roof by slow degrees, feeling everything with the utmost care; but there was no need. Regan's cunning had not carried him that far.

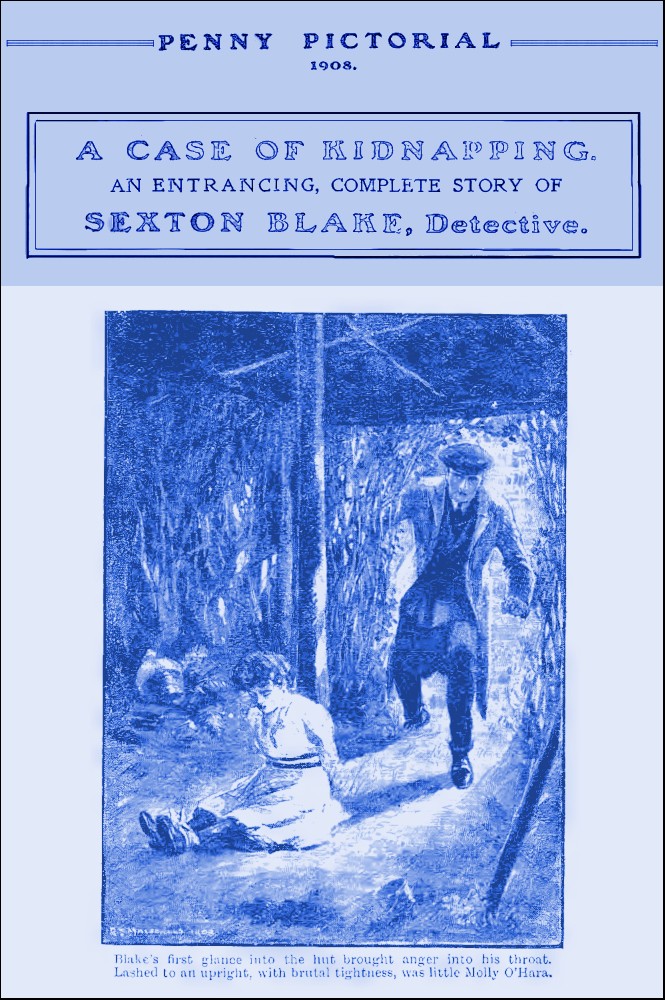

His first glance into the interior brought a gulp of fierce anger into his throat. The peat roof in the centre was some five feet from the ground, and in the midst was a stout upright of rough pine wood.

Lashed to this with brutal tightness was poor little Molly O'Hara. Her arms were bound round the post behind her back till the flesh of the wrists was cut and the skin broken, and two more coils were round her waist.

She was a very different Molly from the description given him by the parents. Her frock was muddied and torn and weather-stained.

Her face and neck and arms had been dyed with walnut-juice to a dark brown, and the fair golden hair, cropped short, had been stained a deep blue-black, as also had her eyebrows.

But the most pitiful thing of all was that, in spite of the cruelly tight cords and her cramped position, her head had fallen forward, and she was sleeping—the sleep of utter exhaustion—and there were great hollows beneath her cheek-bones.

She never even moved when Blake entered.

With deft fingers, careful not to disturb her, he loosened the cords and the handkerchief.

The small body swayed and would have fallen, but he caught her just in time and laid her on his outspread coat.

Very gently he pushed back the hair from her forehead, and noted that it was golden at the roots.

She sighed and stirred a little uneasily, then curled herself up again on the coat and slept soundly once more.

Blake sat cross-legged beside her, staring out across the sunlit moor, and now and again turning his glasses up the trail.

But in the intervals his fingers were not idle; he was knotting and testing the strength of the ropes. He took his binocular-case and removed the strap, twisting it with another which he found in the hollow, to give it additional holding power.

The place contained a blanket, a big sack (the same probably which had been used on the eventful night), a fair assortment of tinned provisions (some opened and empty), and an empty whisky jar.

In a far corner he found an old suit of workman's clothes and a pair of down-at-heel boots.

He guessed when those had last been used.

In the pocket of the coat he found the remains of a packet of bull's-eyes, and transferred them to his own.

Then he looked about him to prepare a meal of some sort, for he guessed the child would be hungry when she woke.

He dare not light a fire, but he found potted meat and biscuits and an old tin cup, which, after careful rinsing, he filled with sparkling cold water from a brook close by.

The sun was already beginning to sink slowly, when Molly woke with a little cry of fright.

What she must have suffered in those long days and nights, with no companion but Regan, moody or perhaps violent in his cups, Blake hated to think. She stared at him, blinking, and still a little sleepy.

"Dinner-time, Molly," he said, smiling, and offered her the biscuits.

She stared at him, puzzled and bewildered, but ate ravenously, whilst he explained in a roundabout way that he was come to fetch her home.

Gradually, though it took him the better part of an hour, he managed to induce her to treat the whole thing as a sort of mixture of make-believe, fairy-story and a nasty dream.

Bit by bit she came round to his point of view, and finally tumbled quietly off to sleep again, for the long nights of terror had weakened her a good deal.

Blake rested her head against his knee, and watched the trail in the fading light with a grim set expression on his face and a moody frown.

All of a sudden he stirred and she wakened.

"You goin' somewheres?" she asked drowsily.

"Only a little way, Molly," he said, smiling. "You be a very good girl and stop here till I come, and then we'll both go home to supper. Promise?"

"Promise," she said.

Blake rose, picked up the ropes and straps, and crawled out coatless. Three miles away he had marked Regan staggering down the track with something in his hand.

Blake glided along in the dusk till he was half a mile from the hiding-place, and dropped quietly to cover.

It was his intention, for his own satisfaction, to give Mr. Patrick Regan the soundest thrashing that a man ever had before, handing the remains over to the law.

But when the man was still a hundred yards away, he knew that he must deny himself.

Mr. Regan's profession had proved too much for him, and he had evidently taken too kindly to the contents of the jar he was carrying—in fact, he was carrying most of it internally, and could barely stumble along.

He had dressed for the part cunningly in a modest touring suit of heather mixture, with a camera slung over his shoulder.

But for his mental condition he could have shown up at Drent or anywhere without exciting suspicion, and would have been taken for a harmless, rather good-looking man on a walking tour.

The drink had proved his undoing, and the end came swiftly.

Blake rose suddenly from behind a gorse bush.

"Evening, Regan," he said, and caught him with his left squarely under the angle of the jaw.

Patrick Regan dropped in a sudden heap, and the half empty jar went rolling down the slope.

Blake bound him securely hand and foot, then forcing open his mouth, he compelled him to swallow half a dozen of the doctored bulls'-eyes. When he was satisfied that the man would lie there like a log for hours, he gave a final look at the knots, and left him.

Then he went back to the hiding-place.

"Come along, Molly, old lady," he said "We must hurry; it's getting late. I'll give you a pick-a-back ride part of the way home to supper and mother."

Mr. Patrick Regan lay and slept his last night in the open under the stars, but in the small hours an enthusiastic party of factory hands, with lanterns, came to fetch him, headed by Blake; and between them kicked, dragged and hauled him within reach of the long arm of the law, waiting for him on the Drent road.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.