RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

A BIG forty-horse power car was throbbing and panting in front of Blake's house in Messenger Square in charge of a chauffeur in livery. Upstairs in a great state of excitement was an old acquaintance of Blake's, Mr. Vansittart, the genial American millionaire. Five minutes later he and Blake emerged, the latter carrying a well-worn suit case, and, with a triumphant "Hormph!" the big car started off to whirl them along to Dangerston, seventy miles away.

To drive for Mr. Vansittart meant to drive with a fine disregard for speed limits and police traps, and they were due to lunch at Dangerston at two; it was then on the stroke of twelve.

"It's a most terrible thing this," said Mr. Vansittart, as they settled themselves down in the tonneau. "It's real good of you to come with me right away, and I'll explain as we go. Everyone wanted to call in the police, but I said 'No.' When I was trading hogs on the other side I always made it my rule to buy the best goods in the market. When I want a doctor I go for the biggest bug in the profession. So, when they said police, I said 'No,' with a large N. I wanted the brightest man with the best brains in the criminal line of business, and I guess that's you. Police—and county police, at that—are all very well for swopping lies about the pace of my cars, but I guess they haven't brains enough to catch a lame rabbit. I reckon they must have been taking tea when brains were being served out over the bargain counter, and had to put up with the odd remnants and spoilt lots."

Blake smiled grimly.

"From all of which I gather that you were fined for exceeding the limit on your way up?"

"That's the truth, sure. See here, now, though. I'd best post you up on this business before you arrive. We've a big crowd of folk staying down at Dangerston, and most of the houses round about are bang full up, too. Balls and high jinks of all sorts buzzing around, savvy? Well, for the past fortnight there've been ugly rumours of folk missing things—fancy jewellery and things of that sort. We thought we had a case ourselves last week. Lady Vickersfield waded in one morning with the high strikes, and spluttered out that her tiara had been stolen. Well, of course, we were all mighty upset and feeling pretty sore. The house was turned upside down, and half the servants gave notice on the spot because their boxes were searched.

"But the cream of the joke came the next day when the tiara was found in a drawer in her own room under some laces, where she had put it herself, and turned out to be plain plate glass. She had sold the original stones, without her husband knowing, to pay her bridge debts. Of course, the laugh was on her, and she discovered a dying third cousin whom she concluded to go off and nurse in a hurry. Yesterday, however, the boot was on the other leg. Mrs. Palliser, the wife of the train man, missed a fine ruby necklace, and little Molly Tremaine an emerald pendant. They were genuine enough, and the air was pretty black and depressing. Bang on top of that last night my wife's black pearls ran away, and they cost me over forty thousand dollars at a slap up Paris store, in the Rue de la Paix. So I said to myself, 'Sam, my boy, it's time for you to git up and git. Blake's the peg for this hole. Get a hustle on you and tote him right along.' So I toted, and there's the thing in a pea nutshell."

Blake listened attentively. Big jewel robberies are generally skilfully and cunningly planned months beforehand. So cleverly, too, that the task of unearthing the criminals is never an easy one, whilst the chances of recovering the jewels intact are small.

"Well," said Mr. Vansittart, "how does it strike you?"

"It's hard to say anything until I've had a look round and got the actual details first hand. But it seems to me that the affair has been very carefully organised and thought out by an expert professional, in which case it will be a hard nut to crack. We'll talk of something else meanwhile. I want to come at the thing with an unbiassed mind. It is a fatal thing to start theorising on insufficient data."

"Sure!" said Mr. Vansittart. "Bad as buying hog on the seller's cuss word that they're in prime condition. I did that once when I was full of youthful enthusiasm and green food, and it took the bottom out of my purse to fatten 'em up so as you could tell whether they were natural hog or somebody's patent new-fangled ventilators."

They were only fined once more on the return journey, and in isolated stretches they raced along at a comfortable fifty-four or five, whilst the noise of the "cut out" and a spiral of dust a quarter of a mile long invited people to take notice that they were coming. They slipped through the Dangerston Park gates on two wheels seven minutes ahead of time.

Blake had a nodding acquaintance with several of the house-party, and his host introduced him to the others.

Not a word was said about the robberies at luncheon—in fact, from the laughter and chatter that went on during the meal it was hard to realise that between them the party had lost something like twelve thousand pounds' worth of jewels. For Mrs. Palliser's rubies were reputed to be worth nearly five thousand, and Miss Tremaine's pendant contained an exceptionally fine table emerald, and was worth, perhaps, as many hundreds.

After luncheon, however, Blake got Mrs. Vansittart to himself and went into matters thoroughly. He was sure that the robberies were all the work of one gang, so he took the most recent specimen of their handiwork—his hostess's vanished pearls—as a starting point.

"I want you to tell me exactly all you know," he said to her, "every detail—however insignificant it may appear to you—but only what you know, not what you may think or imagine."

Mrs. Vansittart was a thoroughly practical woman, shrewd, and a quick observer.

"You come up to my room right away, Mr. Blake," she said, "and I'll explain everything to you on the spot. Now, to start with, over there let into the wall is the safe where my jewels are kept when I'm not using them. It has a patent burglar alarm which has not been touched or tampered with—in fact, the safe was left alone. Last night I wore my pearls, my usual rings, and a few odd-and-end brooches. We sat up late—in fact, it was half-past one before I came to my room. I never keep my maid Amélie up when I know I'm going to be late. I used to make my own gowns and do the housework with one coloured help when Sam and I first started, and I reckon I'm still strong enough to wrestle with my own back hair without having palpitations.

"I always put any jewels I am wearing overnight on the dressing-table just here, ready to be locked away in the morning. I'm not nervous, and I keep a small gun in the drawer beside the bed there, and I invariably lock my door. Last night I remember distinctly placing the pearls right on this very spot, beside the hairbrushes, together with some rings and two or three brooches. and on the top of them I dropped a handkerchief. I locked the door, read a little after going to bed, and switched off the light. One of those windows was open about a foot at the top and the blind was down, but you'd want an aeroplane to get in that way.

"Besides, as a rule, I'm a light sleeper, and if anyone were to so much as move that blind aside I should surely hear them. Last night, however, I confess I slept unusually soundly—quite unusually for me. I didn't wake till Amélie knocked with my tea at eight, and I had quite a touch of headache. The door was still locked, for I undid it myself, the window was untouched—in fact, everything was just as I had left it.

"Amélie brought in the tea and began tidying up the room. Naturally, one of the first things she did was to go to the dressing-table to lock away the jewels. She found everything exactly as I had left it with one exception—the black pearls were not there. The handkerchief and the other jewels were undisturbed, but the pearls were gone. We hunted high and low, looked in every conceivable and inconceivable place, but not so much as a trace of them could we find.

"Now, Mr. Blake, there is your case. I am as positive that I placed the pearls exactly here as I am that I am alive and awake. I placed the handkerchief over them just as Amélie found it this morning. I locked the door, and it was still locked when she came to call me. The windows are inaccessible, and the pearls have vanished. I don't walk in my sleep, and I'll stake my existence that Amélie is thoroughly trustworthy—apart from that, however, she had no chance to slip the jewels off the table and hide them, for, as luck would have it, I was watching her movements in the glass as I lay in bed, and it was a matter of seconds before the loss was discovered."

Blake nodded gravely.

"It is certainly a curious case, and I must thank you for your clear way of stating the facts. Now I want to ask you a question or two. Can you tell me for certain who has had access to this room since the discovery of your loss. For certain, mind."

"Easily. Amelia, myself, my husband, and yourself. Not another living soul; and the room has been securely locked the whole time."

"Very good. Then, with your permission, we will make one more thorough search before we take any other steps. By the way, I imagine that the other robberies were of a similar nature. I mean in the cases of Mrs. Palliser and Miss Tremaine."

"Precisely similar. In Mrs. Tremaine's case, though, it was even more extraordinary. She is of a very nervous disposition, and her door was not only locked, but bolted, on the night of the theft, and both lock and bolt were untouched in the morning."

Blake frowned thoughtfully, and striding across to the window, threw up the sash and leant far out examining the walls to the right and left, above and below.

Mrs. Vansittart had not exaggerated when she said an aeroplane would be the easiest way of reaching the windows. There was not so much as a cornice a cat could have walked along within many feet of them. The roof above projected so far that a rope let down from above would have been useless; and to approach from below would have needed a ladder which it would have taken three able-bodied men to handle. Blake dismissed the window as hopeless, and began a systematic search in the room itself.

More than once before he had come across somewhat similar cases, where valuables had been quite unconsciously hidden by their owners in the most unlikely places, either in their sleep or in a moment of temporary aberration.

Mrs. Vansittart helped him, but without much enthusiasm, and Blake himself was not very hopeful. Still he felt that in so serious a case he ought to leave nothing to chance.

Half an hour was sufficient to make him positive that the jewels were not hidden anywhere within the confines of the room. In that case, he argued, it was clear that the room had been entered at some time during the night, the jewels cleverly stolen, and the door locked again from the outside.

He strode over to the door and tried the lock several times. It worked easily and smoothly, and had not been tampered with in any way.

Next he pulled out the key, and took it to the window to examine it closely. At the first glance he gave vent to a sharp exclamation.

"What is it?" asked Mrs. Vansittart anxiously. He held the key out to her.

"Look at that," he said. "Look closely. Do you see those small marks just at the very end of the key? They look as though it had been gripped firmly by a small pair of pliers, and are quite fresh, as you can see by the brightness of the metal where the surface has been scratched. To you that may not mean much; but to me it tells a story of its own. The jewels have been taken by a trained and expert thief, who is well up in all the tricks of the Continental jewel robbers. Those marks were made by an instrument known to Paris thieves by the name of 'ouistiti.'

"The ouistiti is a most ingenious contrivance, not unlike a pair of curling-tongs. But the prongs are both concave, and the long handles give them endless leverage and gripping power. It can be inserted noiselessly into any lock from the outside, then the end of the key is gripped firmly by the prongs, and slowly turned, just as easily as you yourself could turn the key here in the usual way.

" The thief has used one of these in this case; simply unlocked the door, taken the pearls, and slipped out, locking the door again from the outside. One moment. You said that you are, as a rule, a very light sleeper, but that this morning you awoke with a dull headache, after sleeping unusually heavily. I think I begin to understand."

He bent down over the lace-trimmed pillows for an instant.

"Just as I thought," he said quickly. "A chloroform spray has been used. There is still a faint trace of the odour of chloroform clearly perceptible. This is the work of a type of thief known to the French police as an 'araignée'—in other words, 'the spider.' They are a very clever section of criminals, who work mostly in the large hotels and on board the big liners, and they have methods peculiarly their own, of which the ouistiti and the chloroform spray are instances.

"And another point is that they never attempt a theft without having previously made themselves intimately acquainted with their victims' habits and peculiarities. If I may, I should like to have a glance at the rooms of the other two ladies who have lost valuables."

Mrs. Vansittart led the way down the corridor, and a short inspection showed Blake that in each case the ouistiti had been used skilfully and firmly, whilst in Miss Tremaine's room the catch of the bolt had been carefully unscrewed and the screw-holes enlarged, so that a touch from outside would detach the catch from the woodwork.

"Have you any foreign servants staying in the house other than your maid?" he asked.

Mrs. Vansittart shook her head.

"Not one; and Amélie has been with me for years. If she had wanted to rob me I guess she could have done it over and over again before now, yet I've never missed a thing."

"I think your husband said something to me about a ball that is to be given in the course of the next few days."

"Surely," answered his hostess.

"Do you think you could invite one of your friends who has some particularly notable jewellery down for the occasion?"

Mrs. Vansittart stared.

"Someone, I mean," explained Blake, "who has some famous necklace or other jewels, and whose movements are important enough to be noticed in the society columns of the press. I want to use her as a bait for a little trap, you see. Of course, I shall be on the look-out, and will guarantee that she suffers no loss."

Mrs. Vansittart knitted her brows.

"I see," she said slowly. "Why, yes, of course, I know the very woman, Lady Malancourt. I reckon every one has heard of the Malancourt diamonds. I'll wire her right away, and ask her to come as a special favour and bring her diamonds along. And Sam can just drop a line to an editor or two and get them to put in a paragraph."

"That's capital," said Blake. "And if you wouldn't mind, you might let drop a hint to the others that—that what shall we say? That I fancy the thefts are the work of a well-known London criminal, and am communicating with my assistant in town to have him watched. But, above all, don't say a word to anyone—not even to your husband—of what I told you about the thief's method."

Mrs. Vansittart eyed him shrewdly.

"I guess you're only telling me the tail half of the dog," she said smiling; "but I'll do exactly as you say."

"Very well, then. And now we may as well go downstairs and join the rest."

IN spite of the cloud which was hanging over them, the house party was a very merry one, and Blake, to all outward seeming, was as cheery as the rest. But all the time he was watchful and uneasy.

As Mrs. Vansittart had expressed it, he had only told her the tail half of the dog; but the other half was worrying him considerably, and the point which worried him most of all was the actual whereabouts of the stolen property.

. He was convinced that so far the jewels were still in the vicinity of Dangerston. Valuable stones, though they can be hidden in a small compass, are by no means easy to dispose of, and, moreover, they are extremely difficult to hide in such a manner as to defy detection and at the same time be available at the precise moment when the chance comes to smuggle them away in the hands of a confederate.

Blake's chief hope lay in the cupidity of the thief, and the success of his trap baited with the Malancourt diamonds. With these in prospect, he felt pretty sure that the culprit would wait to add them to the rest of the spoil before spiriting the whole lot away. Meanwhile, there was nothing for him to do but wait and watch.

As usual in country house-parties, there were a good many flirtations going on, and Blake inadvertently dropped in for a severe lecture from his hostess by blundering into one of the most promising, all unawares.

Molly Tremaine, the only unmarried woman of the party—an extremely pretty girl—was looked upon by the others as the exclusive property of Captain Lascelles.

Anyone could see with half an eye that the two were absolutely wrapt up in one another, and Mrs. Vansittart was particularly anxious to give them every opportunity to bring matters to a conclusion. Unfortunately, on the very morning of Blake's arrival, the two had had a slight disagreement.

Blake, not knowing this, and being placed next to Molly Tremaine at dinner, laid himself out to be as amusing as he could; and Miss Tremaine, in a momentary fit of pique, devoted her attention solely to him, whilst Lascelles—a good-looking man, in a light cavalry regiment—regarded them with a dejected, hang-dog look from the far side of the table.

Matters got worse, too, as time wont on, for both the young people had wills of their own.

Lascelles, finding himself openly flouted, took refuge in a desperate flirtation with Mrs. Palliser, and, whilst really in the depths of despair, forced himself into an affectation of almost uproarious hilarity; and Miss Tremaine, determined to have her revenge, absolutely ignored him and talked to nobody but Blake.

It was after Blake and she had gone for a long ramble on the following morning, with the ostensible purpose of taking some snapshots with her hand-camera—she was an enthusiastic photographer—and had returned disgracefully late for luncheon, that Mrs. Vansittart arose in her wrath and gave Blake a private lecture as to her views on his conduct.

He took the lecture meekly enough, and was forgiven on the condition that he promised to behave with more discretion in future.

He made amends by going for a long tramp with his host in the afternoon—Captain Lascelles having been despatched by Mrs. Vansittart to drive Miss Tremaine to the neighbouring town for a fresh supply of films—and when he returned Lady Malancourt had just arrived.

The ball was for the following night, and Blake himself had chosen the room which she was to occupy.

It was in an angle of the main corridor, and the door was in sight from the door of Blake's own room, some twenty feet further along on the opposite side.

The ball was only a small affair—just the house-party and a few of the nearest neighbours.

But Blake had noted with satisfaction that the paragraph had been duly inserted in the papers announcing Lady Malancourt's visit and giving a reference to the diamonds.

Blake took little part in the festivities, and retired early to a deep armchair in the library with a book and a cigar.

He was on the alert, however, and as soon as he heard the first of the guests departing he closed his book with a snap, threw away his cigar, and rose with a sigh.

He would have given fifty pounds willingly if Vansittart had never thought of calling him in to help.

It was a little after two as the last of the guests drove off, and the house-party began to dwindle off sleepily to bed.

A few of the men lingered in the smoking-room for a final cigarette and a whisky-and-soda.

The lights were being turned out all over the house, and at last Mr. Vansittart rose and said good-night.

"You fellows can do as you please," he said, "but I'm off. I guess bed's good enough for me at this hour."

The others, laughing, rose too, and a general movement was made. Blake, who had been watching his opportunity, touched his host on the arm unobserved by the others.

"Come to my room," he whispered, "and come as soon as you can."

Vansittart stared, and then, catching sight of Blake's grave face, he nodded.

"Sure," he whispered back.

"Bring Lascelles with you," added Blake; and then aloud, "Good-night, all of you, late hours don't agree with me."

Ten minutes later the door of his room was softly opened, and Mr. Vansittart came in followed by Lascelles.

Both men had changed into smoking jackets, and looked a little uneasy and surprised.

Blake closed the door behind them and pointed to two chairs.

"If you don't mind," he said, "I'll switch off the light. I can explain just as well in the dark, and it will be better.

"Now," he continued, "I've asked you to come here and watch with me, because I am pretty certain that to-night an attempt will be made to steal Lady Malancourt's jewels, and I want you two to help me. Lady Malancourt leaves tomorrow, so if the attempt is made at all, it must be made to-night, and I fancy—though I can't be sure—that it will be.

"All I want you to do is to sit here in absolute silence, without moving, and I think it would be better if you were to take off your shoes. I don't think we shall have very long to wait—perhaps an hour."

The two men complied, and Blake very softly set the door of his room ajar, and took up his position close to it.

The suspense which followed seemed to two of them, at any rate, intolerable. The whole of the big house was wrapped in a deathlike silence—the servants, tired out, had long ago retired to their quarters, and the rest of the party, fatigued by the dancing, were sound asleep.

Suddenly Mr. Vansittart felt a slight pressure on his arm, and Blake's voice whispered in his ear:

"Follow close behind me, but whatever you do don't make a sound. Bring Lascelles, too."

In the pitch blackness they filed out into the corridor, and as they did so from a little way ahead came a very faint, almost inaudible, click.

Instantly Blake stopped dead, and held the others back with outstretched arm. The sound was not repeated, and the death-like silence became more intense than ever.

Blake put his lips close to Mr. Vansittart's ear.

"The electric light switch for the passage is just at your elbow," he whispered very low; "you two wait here and listen carefully. The instant you hear another click, turn on the light. But whatever you see or hear, make no sound."

He left them there, and glided away in the darkness, feeling carefully with his fingers till he came to Lady Malancourt's door.

He had studied the position carefully in daylight, and knew every inch of the ground.

Once at the door he flattened himself against the wall and stood motionless as a statue, hardly breathing.

Five minutes passed—ten—and then his muscles suddenly stiffened and grew tense. His trained ear had caught a sound which to ordinary senses would have been inaudible.

It was the very faintest suggestion of a rustle of a curtain.

Sight was useless, for the corridor was so dark that it was impossible to see an object only a few inches away.

There came another faint, indescribable sound—a pause—and a slight grating noise.

Blake measured his distance mentally—he had practised and studied the situation in daylight—and flung out both arms.

With his left he encircled a human form which he could not see, with his right he just managed to stifle a cry of fright before it could be uttered.

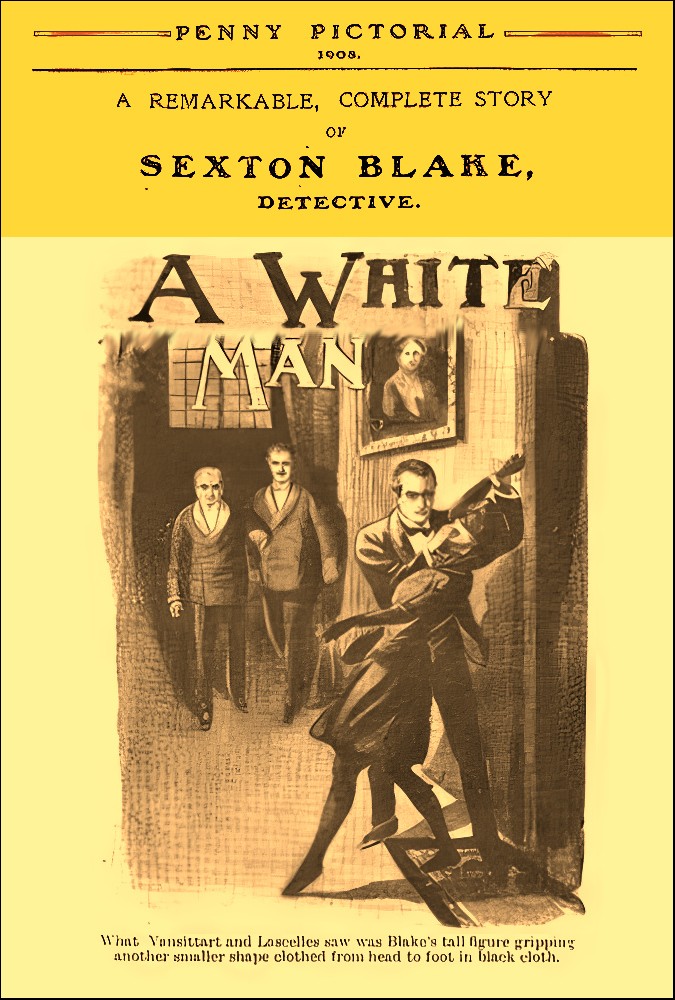

There was an uncertain click—followed by another as Mr. Vansittart switched on the light, which for an instant dazzled them all.

What Vansittart and Lascelles saw was Blake's tall, slim figure gripping another smaller shape clothed from head to foot in black cloth. There was a faint struggle, a quick convulsive movement, and the next thing they realised was that Blake was hurrying towards them carrying something in his arms.

"To the library, quick," he whispered. "You lead the way, Vansittart, and switch off that light."

In silence the small procession hurried to the library, which was in an isolated part of the building, and Blake himself turned on the lights after laying his burden gently down on the sofa.

The other two watched him aghast and uncomprehending. His own face was white as a sheet of paper, and looked haggard and drawn.

"Get some water, Vansittart," he said sharply. "You, Lascelles, close the door and lock it.

"Here is the secret of the jewel robberies, and I wish to Heaven I'd never been called in to interfere."

The two men stared blankly, and Blake took the water-jug from Vansittart's hands, which were shaking badly.

"What does it mean?" asked the latter huskily.

Before them on the sofa lay the figure of a girl in a species of gymnasium costume. She had on long black stockings with black felt soles to them, forming a kind of shoe.

A short black cloth skirt of the type women use for fencing, a black jersey with a hood which completely covered her hair, and a black mask. Even her hands were covered with thin black silk gloves; and from the limp attitude in which she lay it was clear that she had fainted.

Blake took two objects from his pocket—one, apparently a pair of plated curling-tongs; the other, a sparkling rivière of big diamonds; then, with a warning motion of his fingers to his lips, he stooped, and gently undid the mask.

There came a horrified gasp from Mr. Vansittart and a groan from Lascelles, who staggered and clutched a chair for support.

For, beneath the mask, with closed eyes fringed with long lashes, was the white face of pretty Molly Tremaine.

"Good Heavens!" said Lascelles, under his breath, and would have flung himself on his knees beside her; but Blake stopped him.

"One moment," he said. "You will understand now why I wished to goodness I had never been called into this. The moment I saw the method of Mrs. Vansittart's robbery, I knew it for the type of work peculiar to a class of criminals known as 'the Spiders.' They use these"—picking up the tongs—"to open doors; then, dressed, as you see, entirely in black, they creep in. If there is the slightest sound they lie still, face downwards, on the floor till their victim goes to sleep again, and in a dark room it is impossible to see them. If anyone is known to be a light sleeper, they use a chloroform spray on the pillow.

"Now, on the afternoon of my arrival, I heard Mrs. Palliser and Miss Tremaine talking about fencing, and, as you see, the fencing dress worn by ladies and this are similar. Almost against my will, that put me on the alert. When I went with Mrs. Vansittart to Miss Tremaine's room to examine the bolt, I saw these tongs openly displayed on her dressing-table. She was quite wise in leaving them there; not one person in a thousand would have suspected their real use. The moment I saw them I knew who the culprit was, and that her own robbery had been merely a clever ruse.

"1 got her to talk French at dinner, and slipped in here and there a few phrases of Paris thieves' slang. Quite unconsciously she betrayed an intimate acquaintance with the words. I learnt afterwards from Mrs. Vansittart that Miss Tremaine had been at school in Paris with a certain Mlle. Fougières. The woman was arrested a short time ago for a series of very daring robberies of just this class. That made it clear how Miss. Tremaine had come by her unfortunate knowledge. I got—— Ah, she is coming to! Vansittart, a glass of water!"

The girl stirred uneasily, and sat up with a little moan, still dazed and bewildered. Suddenly she seemed to realise her surroundings, and remember. Blake saw her lips part, as though to scream, and, darting forward, laid his hand gently over her mouth.

"Please be quiet," he said, not unkindly, "for your own sake—for everyone's sake! Sit quite still, and you shall say what you want to later.

"Captain Lascelles, forgive me if I hurt your feelings and hers, but the only way out of this wretched, business is to speak freely. You know that I laid a trap with Lady Malancourt's jewels, and you have seen the outcome of it.

I think I can give you some explanation of Miss Tremaine's actions—an explanation which she might not like to give herself. I fancy we all have reasons—good reasons—for thinking that you two are very fond of one another. I believe I am right in saying that you are not very well off, and I know I am right when I say that Miss Tremaine is by no means so well off as she is popularly supposed to be.

"Forgive my blunt speaking, but I am positive that the motive which induced her to—to do what she has done, was terror lest, when the truth became known as to her real financial position, she might lose your affections. In her straits and her despair, she remembered the evil lessons she had learnt from La Fougière, and, driven to distraction, she yielded to temptation."

Lascelles gave a strangled cry, and moved towards her. The poor girl flung herself on her knees and buried her face in his hands, sobbing convulsively.

"It's true, Harry! He has told you the truth. I'm guilty! I've stolen and thieved; but my heart was breaking, and I dared all and risked all because I was so afraid—so horribly afraid. 1 will give everything back! I will do anything—anything you wish!"

Blake touched her on the shoulder.

"I think, Miss Tremaine, you had better leave that to me."

He moved to a cabinet as he spoke, and took from it her hand-camera, which he held out.

"The jewels are here," he said to Mr. Vansittart. "It took me some little time to find them; but I remembered noticing that Miss Tremaine's camera was of rather an unusual shape, so I borrowed it this evening whilst you were all dancing; and here, as you see, are the missing things."

He pressed a catch beneath the roll holder, and a false bottom swung open on a hinge.

Blake held out the contents in his palm, and glanced first at the girl and then at Captain Lascelles. Then he beckoned to Mr. Vansittart, and they left the room.

Ten minutes later Lascelles came out, alone. He was very white, but smiling.

"I shall send in my papers to-morrow," he said. "Miss Tremaine and I propose to get married at once and go to Canada and start afresh—unless, that is, either of you wish to press this matter home. If you do, I have the honour to inform you that we shall carry out the programme as soon as my future wife's term of punishment is completed." He eyed them both squarely and defiantly, his head thrown back a little.

Blake and Mr. Vansittart wrung his hand silently.

"I hoped that was the view you would take," said Blake in a low tone. "Captain Lascelles, I wish you and your wife that is to be every good fortune and happiness, and I feel sure that you will neither of you ever regret the step you are about to take.

"As to the rest, no one shall know what has passed between us to-night. Mr. Vansittart and I will see to that, and to the return of the jewels. Now, if I might advise you, I should get Miss Tremaine to her room as soon as possible, for it is very late."

Once more they clasped hands in silence, and Lascelles returned to the library.

"Thank heavens they took it the right way!" said Blake.

"Lascelles is a white man, sure," said Vansittart; "and they simply worship each other."

"That was why!" said Blake, and switched off the light.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.