RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

A TELEGRAPH-BOY came whistling up Blake's steps, rang and thundered on the knocker with quite unnecessary zeal. Blake anathematised the boy in vigorous terms, regulated the flame of a Bunsen burner, and going downstairs took the proffered yellow envelope and tore it open.

It ran:

BLAKE, MESSENGER SQUARE,—DICK VANISHED OR ABDUCTED FROM ST. RUDOLPH'S SCHOOL, HOLME, KENT, LATE LAST NIGHT; MASTER FEARS FOUL DEALING; CAN YOU GO DOWN AT ONCE; WIRE REPLY; PLEASE GO IF POSSIBLE; MUCH WORRIED.—BORRODAILE.

Blake read the message over again. Borrodaile was a man whom he had known fairly well some years ago as a rising, and, oven at that time, eminent scientist. Of late, however, they had drifted somewhat apart. He knew Borrodaile to have a considerable private fortune, and one or two rather bitter enemies. It occurred to him that the master's point of view might have something in it.

"Give me a form," he said to the boy, and hastily scribbled a reply. "Going down by next train available.—Blake."

HOLME is one of those irritatingly inaccessible places, which, though near in point of distance, yet take two or three hours of cross-country travelling by wretchedly slow little branch-line trains.

It was past three in the afternoon when he reached the station, to find that there was no fly available, and that he had a three-mile tramp to the village and the school.

On the whole he was not sorry after his long journey, and swung off down the road on a bright, frosty winter's afternoon.

On sending up his card he was shown at once into the comfortable study of Mr. Hoskins, the headmaster.

The latter proved to be a genial, middle-aged gentleman, with a clever, kindly face, which could, however, be stern enough on occasion, and a courteous old-world manner. Something of a sybarite, too, in a scholarly way, judging from his luxurious surroundings and some rare first editions on his bookshelves. There were many pewters, too, reminiscent of his 'Varsity days, and some good prints.

"I am so glad you have come, Mr. Blake," he said, holding out his hand. "I hope you will forgive my not having sent to meet you, but I only got Mr. Borrodaile's wire half an hour ago. and imagined that you would be coming by the 5.40, which for this part of the world is a fast train. Excuse me a moment!"

He rang the bell, and a man-servant answered it.

"Bring the port and some biscuits, Mansbridge," he said. "Mr. Blake, you must be fatigued after your journey, and for that there is no prescription equal to a glass of good sound port; and now as to this wretched business. I am not an alarmist, Mr Blake, but I assure you that I fear the boy was abducted, if not actually by force, at any rate by threats or persuasion. I am afraid I have been able to do little myself, but what little I have done points in that direction. You will see, of course, that both in the interests of Mr. Borrodaile and of the school itself it is highly desirable to keep the matter as quiet as possible, and, for that reason, I have not seen fit as yet to call in our worthy local police, who, between you and me, are more worthy than brilliant; still, if you wish, I——"

Blake held up a protesting hand. "If every one showed the same common-sense, Mr. Hoskins, I can assure you that I should be saved a great deal of unnecessary work. You have some reason, I imagine, for not regarding the case merely as one of truancy—boys are queer animals, and sometimes a fancied grievance, a row with some of the other boys, anything may drive them to all sorts of extraordinary actions on the spur of the moment; for instance, was young Borrodaile unpopular?"

"Quite the reverse; he was very bright and cheerful, quick at his lessons, a good sportsman, and"—with a twinkle—"what 1 generally consider a healthy sign—he was up to mischief on an average twice a day."

Blake smiled. "That is usually a hopeful sign."

"He was small and slightly built, but active and played well in the junior football team. He was doing very well in the term exams—we are in the midst of them now. School breaks up for the holidays in a few days, and I can conceive no possible reason why he should have run away voluntarily. In fact, I may say that I have proofs that he did not. Kindly look at these, they were picked up on the floor of his cubicle, tossed into a corner behind the washstand."

He handed Bloke half-a-dozen scraps of coarse dirty paper from a drawer.

"Some of them seem to be missing, but the purport is clear, fancy."

Blake arranged the scraps on the table in some sort of order; there were several gaps; it read:

"——ready——after eleve——ight ——noise when ——on windo———this up."

"I suppose," said he, "that the original ran something like this:

"'Be ready (a quarter or half an hour) after eleven (to-morrow) night; (make no) noise when (I tap) on window; (tear) this up.'

"I don't suggest that those are the actual words, but merely the general sense of the message."

Mr. Hoskins nodded. "I read it in something that sort of way myself."

Blake turned the paper over and held it to the light; it was apparently part of a paper bag such as grocers use; some of the edges of the outer fragments had been cut roughly square with a pair of scissors.

The writing had been clumsily done with a quill, and was blotted in places; but one or two of the letters, notably the t's in "night" and "this" showed signs of a certain amount of education in their formation; also three of the e's were written in the style of the current Greek e.

On the whole, Blake was fairly sure that the clumsy handwriting was merely a disguise, and an inconsistent one at that.

The contents of the message inferred, too, that there had been other communications previously, or, at any rate, that someone had managed to deliver a verbal message to him privately. He suggested this to the master.

"It may be so," said Mr. Hoskins, "and now you point it out, I see that it is at least probable; we make it a rule never to interfere with the boys' letters in any way, unless we see some swindling circular or something of that sort cropping up. But I am sure he had no visitors, for that I should be bound to know of, and Holme is such a small place that—one moment please!" He rang the bell again. "Mansbridge, ask the drill-sergeant or any of the servitors if they have seen any strangers about the place or in the village of late.

"You see," he continued, as the servant retired, "we are an isolated community here, and a strange face would be noticed almost at once. Now, if you will come with me, I can show you something else; we shall be quite undisturbed—the boys are all at form.

"I am afraid I make a very poor detective, Mr. Blake," he added, with a rather pathetic smile; "you see, my world is rather a world of books; still, one little thing I have discovered, and I have prevented anyone from disturbing it."

HE led the way round a long series of class-rooms to a wing two stories high containing dormitories; the lower halves only of the windows were barred.

"We prefer to trust them," said Mr. Hoskins, with an explanatory wave of the hand, seeing that Blake's eyes had noticed. "It is better to have a harmless escapade now and again, than let the youngsters feel that they are constantly under bolt and bar—at least, to my way of thinking.

"Now, this is Borrodaile's cubicle. The junior boys are on the ground-floor, a prefect sleeps in a cubicle at either end to keep order, and a master goes the rounds between ten and half-past.

"In the mould of the flower-bed here there is, you see, a footmark, and here another. I found them myself, and for to-day the whole of this part of the grounds has been placed out of bounds by my order—even as regards the servants."

Blake examined them carefully, taking pains not to disturb them in any way, and Mr. Hoskins stood a little apart, watching him with interest. Leaning forward, he next inspected the window-sill and the top edges of the painted bars.

"Can you tell me," he asked quickly, "did young Borrodaile take his boots with him? For he certainly wasn't wearing them. By the marks on the window-sill and here"—pointing to a bar—"he had on rubber-soled sandshoes."

"Bless my soul, you're right. Mr. Blake! I remember now, when his absence was first reported to me, that I noticed he had only lain down on the outside of the bed, with the quilt drawn over him; and that both his pairs of hoots—the regulation number and his football boots—were in their places on the shelf."

"I don't think you would make such a bad detective as you think," said Blake, smiling. "It is clear to me that not only did the boy leave his room voluntarily to a certain extent, but he had made his preparations."

"But what of these other longer marks?" asked the master. "Well, Mansbridge, what is it?"

"I've made inquiries, sir, and nothing has been seen of any strangers either here or in the village, sir."

"Very well. Thank you. You can go."

Blake pointed to the marks on the flower-bed.

"They are certainly the footprints of the person who took Borrodaile away—or, at any rate, helped him; but they are peculiar, and a little puzzling. Also, the light is growing dim. When can 1 come here early to-morrow and be sure of finding no one about?"

"Morning school is from seven to eight. There will be no one in this part of the grounds then."

"Very good. I'll be up early. I suppose there are no letters or papers to give a hint of anything?"

Mr. Hoskins flushed.

"I hate to confess it, but, under the circumstances, I thought it my duty. I went through the boy's effects myself; there was nothing of any sort—not a single letter or note of any kind."

Blake frowned.

"That seems unusual. A boy is generally more careless than that. It looks to me as if someone had warned him to dispose of them. I think I'll be off to the village now. I suppose the inn is tolerable?"

Mr. Hoskins' face fell. Blake interested him. and somehow, in the midst of the worry and distress the affair had caused him, it was pleasant to meet with someone on whom he felt instinctively that he could rely.

"I was hoping you would have given me the pleasure of being my guest," he said a little doubtfully.

Blake shook his head.

"There is nothing I should have liked better. I should have enjoyed a long chat about books and kindred things; but business before pleasure. And the less I am seen to have anything to do with the school, the more likely I am to find out the root of all the trouble. By the way, when is Borrodaile coming down?"

"I wired begging him to remain in town," replied Mr. Hoskins, "in case by any chance the boy should manage to make his way home."

"Excellent," said Blake. "Good-night!" And, shaking hands, strode off through the gathering dusk, smiling. Mr. Hoskins struck him as a peculiar blend of a bookworm and a practical man of affairs.

HE found his way to the inn, which stood at the side of the small harbour—a cosy, picturesque place, with white-washed walls, small red-curtained windows, old-fashioned settles, and an open iron grate dating back a hundred years at least, the design of which went straight to Blake's heart. The landlady, a cheery-faced, buxom dame, redolent of soap-and-water and civility, charmed him still further, and, as an artist out for a holiday, he engaged his room.

The name of the inn was the Benbow, which suited it well. One of Blake's mottoes was: Observe first, and listen to people talking afterwards. He had not had time to observe, so he went early to bed between sheets which smelt of lavender, and allowed himself to be lulled to sleep over a pipe by the pleasant, monotonous plash of the waves on the beach.

THE morning broke fine and clear, and he was astir early. Chance did not bring him often within reach of a sea dip, and so, in spite of the season, he freshened himself up with an icy-cold plunge, and was in the school grounds by a few minutes after seven. The sea mist had cleared, and the sun was trying to peep through a slight haze.

He spent a quarter of an hour over the footprints on the flower-bed. and was still puzzled. They were too shapeless and blurred to tell their own tale—large, but not clumsy, and they showed no definite lines.

No rain had fallen for three days: before that it had been showery. Blake fancied that he might be able to take the trail up further along. The question was, what direction was it most likely to take? With the exception of Holme itself, there was no station within twelve miles, and strangers wishing to abduct a boy and avoid notice would hardly venture to Holme. Also, a cart, however light, in a quiet, countryside place is apt to attract notice if driven by strangers. And a cart must have been used if any station but Holme was the objective. After a few minutes' hard thinking, endeavouring to put himself in the position of those he was in search of, he came to the conclusion that there was but one feasible way open—the sea.

Having made his mind up definitely on this point, the next was to take the nearest and most feasible route to the beach.

The ground shelved deeply from the school over grassland to a lane. In one place the hedge was broken down, obviously a gap of old standing; in fact, a faint track led down towards it.

Blake chose that as the most likely path. On the far side of the gap he met with a stroke of luck—if luck it could be called—for he had only reached the point by exercising his keen analytical faculties.

He found in the mud of the ditch a deep, though blurred, impression of the same footprint which Mr. Hoskins had pointed out on the flower-bed, where the maker of it had evidently stumbled in the dark and slipped. On the far upper-lip of the ditch was a light marking of a rubber-soled sand shoe. Young Borrodaile, evidently the more active of the pair, had jumped and almost cleared it.

The lane led to the right up towards the downs, to the left seawards—in fact, it was little more than an accommodation road.

Blake, holding to his luck and his theory, took the turning to the left. It brought him in time to an open sandy beach, and before he had gone five paces he gave a quick-drawn breath. Carts and men had passed there on the previous day, gathering seaweed for manure, and making the trail muddled and confused. But away to the right a second trail led clear across the sands at a slanting angle—a double track—one of the sandshoes, with a boy's light tread and short pacing, the other slightly heavier and firmer, but not much, although the prints were nearly double the size, and still strangely ill-defined.

He glanced round him, and went down on hands and knees to examine them in detail. In a second he was up again, for the sand impressions were clear and undisturbed.

"A woman, by Jove!" he muttered. "And a clever one at that. She was purposely wearing galoshes two sizes too large to prevent identification. That accounts for the uncertain heelmarks and the general slipshod walk."

He followed up the double trail, which slanted across the sands above high-water mark and away from the village, till he came across a scuffled area which made him pause.

For some three square yards the sand was trampled and kicked up, as if a hard struggle had taken place; beyond that—nothing but a smooth expanse. Blake looked backwards, and then again at the unbroken surface seawards. He was still above even spring-tide watermark.

He took a step forward and instantly, with a curious sucking noise, his leg sank above the ankle; he laid more weight on it and it vanished to the knee; with a wrench and a jerk he threw himself backwards—free, but with a wet, clammy forehead. He had seen quicksands before, and knew that he stood on the edge of one, and a peculiarly dangerous one, for, instead of shelving, it began abruptly and sank into who could tell what depth of treacherous slime; yet, on the surface, it was dry and firm to the casual glance.

He probed with his stick a foot or so from where he stood; his keen eye had detected a slight ruffling of the surface. He felt something beneath the ferrule a trifle more solid, and worked and probed, with an ugly gleam in his eye. The sweat poured off him with the exertion, but at last he was rewarded, and on the end of his stick dangled a boy's cap—a thing of plain tweed—but with a sinister significance, seeing where he had found it. He laid it beside him, and began passing careful fingers over the kicked-up sand around him. Again he touched something hard, a small, cold object, which he picked up and wiped on his sleeve; it was the broken half of a cuff-link, silver, with the monogram R. B.

Blake sat down, jerking the thing in his hand, to consider. Borrodaile, the scientist, was a friend of his, and he felt suddenly afraid, with a fear which was in no wise personal—that he had never felt.

It was with quite an effort that he pulled himself together and forced himself into his usual calm, reasoning frame of mind.

The woman, at any rate—for he was certain it was a woman—must have taken means to ensure her own safety.

He looked about him. his mouth tense and set in a hard line. No boat could come within a hundred yards of where he was, yet she must have got away by some simple trick. The sand was slightly more shelving away to his left, and the edge of the dangerous part, when once one had realised its existence, was fairly well defined. To the right, beyond the quicksand, was a jutting headland, the base of which was covered with water even at low tide.

He took the obvious course. The woman had not retraced her steps; the way to the right was barred, even supposing that she was desperate enough to swim, for at least thirty feet of impassable treacherous ground lay between cliff edge and water, and the cliff was unscaleable.

Therefore, she must have turned to the left, and that way he also turned. There was no track— nothing to guide him—yet by sheer force of reasoning he knew that he must be right, that it was the only possible solution bar one, and that one he dismissed as beyond the pale. He could not bring himself to believe that the woman had sacrificed her own life to satisfy her vengeance, and engulfed herself and her victim in a common grave.

He proved his theory before he had covered forty yards, for on the verge of the quicksand he found another footprint deeply indented, and another, and yet more, all firm and unusually well imprinted, especially towards the heel, though the size and shape of that was obscured as before by the slipshod galoshes which prevented the marks leaving an exact definition.

Blake examined them attentively from several angles. The woman's stride differed from what it had been before. It was more uncertain, and in places she had evidently staggered and weighed heavily first on one foot, then on the other; the steps, too, were of very unequal length.

At one or two points her strength seemed to have failed her, and she had lurched wildly to one side. One might almost have imagined that she was badly wounded or hurt in some way, or that she was under the influence of some drug. Ten yards further on she had stumbled badly, hut always her track led down the beach towards the sea.

Twenty paces below high-water mark the footsteps vanished completely; not a trace of them was to be seen.

Blake circled the track once, twice, and again, but could find nothing. She had apparently vanished from the point where her last footprint marked the sand as completely as though an airship of the future had swooped down and carried her off.

Half a mile further along lay the village, with its small harbour and a few fishing smacks lying off at their moorings or high and dry inside the jetty waiting for the tide. But between them and that last footprint there was nothing at all but an empty stretch of sandy beach and a few old grey-backed gulls. He mechanically rolled a cigarette, frowning the while in deep thought. The night of the abduction there had been a late moon, and the night itself had been clear-skied and rainless.

He found himself gazing absently across the sea, watching the waves churning rhythmically on the shore. There had been a heavy wind the night before—nearly half a gale—and half a mile out the "white horses" were plentiful. Suddenly he drew a sharp breath and jabbed at the sand with his stick. In a flash he understood. Almost without thinking he had realised that the tide was dwindling to the "neaps." Below high-water mark, at varying intervals, lay successive ridges of light tangles of weed, old net, corks, and other litter, which meant that each day the high-tide mark was sixteen or twenty feet lower than the day previous.

The woman, who must have been daring and clever beyond the average, and had studied the locality carefully, had made use of this. She had led the boy down to the edge of the quicksand, persuaded nim or forced him to discard his cap and the broken link, and trampled the sand to give all the appearance of a scuffle. That, however, was merely to blind the trail, and to make it look as though a final and fatal catastrophe had taken place.

Instead, however, she had picked the boy up in her arms and walked with him along the very verge of the quicksand where her footsteps would be obliterated as soon as they were made.

She had picked the boy up in her arms and walked

with him along the very verge of the quicksand.

Compelled to take to the firm beach further on, she had headed down towards the sea and the incoming tide. The boy's weight telling on her had wearied her, causing her to lurch and stagger as she walked and throw her weight backwards to counter-balance his—explaining the deep imprint of her footsteps. Directly she reached the water's edge she had probably put the boy down and dragged him along with her, walking ankle-deep in the sea, and relying on the incoming tide to efface the marks—as up to a certain point it had. Some little distance along she had presumably been met by a boat waiting in readiness, and made off.

It was a clever plan. The one flaw in it was just such a mistake as a woman might be expected to make; she had miscalculated the height of the flood tide. The day before—two days before, in all probability—it would have completely obliterated all traces up to the very edge of the quicksand. But the flood mark became lower and lower with each successive tide. Consequently, instead of the footsteps terminating at the quicksand, pointing, in the event of their being traced, to a final tragic end of all things, a short stretch of firm sand had been left untouched by the tide betwixt the edge of the quicksand and the water; and it was on this that Blake had found those deeply-printed, uncertain footmarks. But for that the natural supposition would have been that woman and boy alike had met a death too horrible to contemplate.

BLAKE had now three facts; The boy's abductor was a woman, clever beyond the average and resourceful; the woman had studied the locality carefully, and had managed to get hold of one of the local fishermen by bribes or threats, for a strange boat hanging about the place must have attracted notice; and, thirdly, she had been at great pains to lead everyone to suppose that the boy was dead, whereas, for purposes of her own, she had kept him alive and carried him off by water. Where, or why, Blake felt that it was beyond him to so much as guess for the time being, and, satisfied with his morning's work, he returned to the Benbow Inn.

BLAKE was satisfied in his own mind that the boat employed in the abduction was a local one. Small fishing harbours are places where a strange boat is noted and classified and speculated over whilst it is five miles out in the offing.

To a landsman's eye they might seem just the same as any other—a fishing-boat and nothing more—but to the fisher folk themselves she would be marked out by a patched foresail, a different lead of the mainsheet, a strange trick of standing rigging, or a hundred and one other trifles. It must be remembered that on the night in question the sky was clear, but there was heavy weather about. Also the tide had only begun to flow shortly after ten. Consequently, any stranger would have been in sight for some hours, and was bound to have been noticed.

A local boat laying at her moorings, however, with the stiffish breeze, could have made her offing at any time during the night without comment, and though a long cruise for a small open boat would have been impossible, it would have been quite safe for her to send her dinghy ashore and pick up the woman and the boy at the risk of a wetting.

Blake pondered these things, and spent long hours in the bar of the Benbow listening to the local gossip, varied by occasional strolls for sketching purposes, to keep up his character as an artist. Not once in all that time did he evince the slightest interest in the school or its doings.

IT was on the fifth night of his stay that he got his first real clue. The conversation had turned, as was only natural, on the fishing prospects, and many and deep were the grumblings he had to listen to.

There were no fish in the bay; and the trawling banks were just as bad. One man had been out three days, another party eight hours, and both had come back without enough to pay expenses.

"Look you, sir," said a third. "There's Jimmy Pratt, one of the best men hereabouts. He's been gone close on a week he has, and come in on the afternoon tide with less than a quarter quintal o' fish. A man can't make no living at the fish these days; and the Mary How—that be Pratt's boat—us always used to reckon as the luckiest craft afloat in these parts."

Not half an hour later Pratt himself came in. Blake knew him because the landlord addressed him by name. A big, bronzed, bearded man, with a hard, resolute face and a keen eye—a good man in a boat, fair weather or foul.

He ordered a glass of rum, and slapped a five-pound note down on the bar counter to pay for it.

The landlord seemed a trifle surprised, and there was some little difficulty in changing it.

"Your luck be in, Jim," he said, counting out the coins. "It ain't many o' them we've seen in this part lately."

Pratt, a man of few words, nodded, grunted, took his drink at a gulp, and strode out.

Blake, watching behind his newspaper, knocked the ashes out of his pipe and also left the bar, but by a different door.

It occurred to him that he would like to have a look at the Mary How.

As luck would have it, she lay at her moorings, a quarter of a mile out, instead of having been brought into the harbour. Blake, standing on the jetty, watched Pratt row out just before dark and see to her riding-light. After a short interval, to Blake's delight, the man came overside again and sculled quickly ashore.

A little later Blake, for the modest sum of half-a-crown, hired a boat and lines from one of his fishing friends, and announced his intention of trying for conger.

The fisherman smiled at him.

"You be welcome to boat, master; but you won't catch no conger—no more'n if you stopped quiet, in your bed."

"We'll see," said Blake. And as soon as the good folk of Holme had retired to their beds he set out.

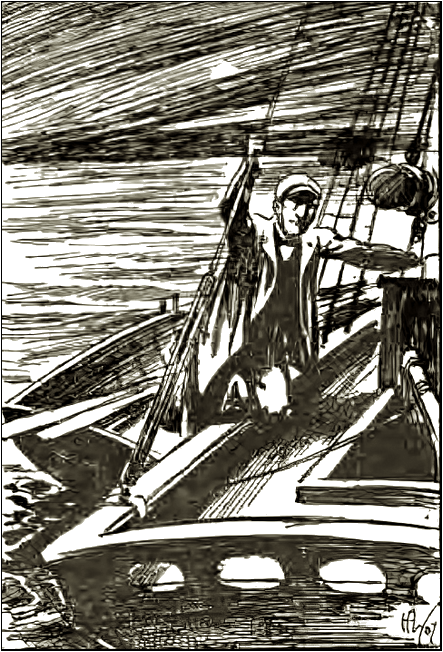

THE night was slightly overcast, and the sea smooth. He made out into the bay beyond the Mary How, and let the tide sweep him down on to her on the side furthest from the village, made fast the dinghy under cover of her stout sides, and scrambled aboard by aid of the port runner.

Blakes scrambled aboard the

"Mary How" by aid of the port runner.

There was no one aboard as he knew; so as long as he kept low, there was no chance of his being disturbed or seen by a stray coastguard, and he carefully avoided the region of the riding-light slung from the fore-stay.

The Mary How was a fine, stoutly-built, ketch-rigged boat of about fifteen tons, and looked as if she could stand a lot of weather.

The small cabin hatch aft was not even locked, and Blake dived below, with his small portable electric lamp, and began a systematic search.

The cabin, though confined, was comfortable and clean. A cushioned locker ran down each side of it, with a rack above for odds-and-ends. On the oilcloth floor was a rug.

For some time he found nothing unusual, and he was beginning to wonder if, after all, he might not be mistaken, when the sole of his rubber sea-boot touched something small and hard lying beneath the threadbare rug.

In an instant he was down on hands and knees, and had the rug flung back in an extreme corner. Betwixt locker and bulkhead he saw something glisten, and picked it up. It was a turquoise earring set with brilliants.

He looked at it in frank surprise. The woman and the boy had certainly been on board the Mary How; for fishermen's wives don't indulge in diamonds and turquoises, especially stones of such value as those before him; but then he had hardly expected the woman of the sands to do so either.

He replaced the rug, and tried the lockers. In the after-starboard one he made yet another find—a brand-new box of Belgian cigars, of which only a few had been smoked. He turned the box over. On the underside was the shopman's label, and beneath it the word "Dunquerque."

Blake had found what he wanted. He wasted no more time over the Mary How. Her clearance papers he knew would be safe in Pratt's pockets. Instead, he cast off the dinghy, and sculled home by a detour. On his way back he caught one small conger, which he carried to the inn in triumph.

THE following afternoon he was sipping his "bock" in the Jean Bart at Dunquerque.

On his way over he had been calculating chances. On the day and night after the boy's disappearance there had been heavy weather. Supposing the Mary How to have sailed shortly after midnight, she would scarcely have made Dunquerque light till darkness had fallen again. Doubtless the original intention had been to send the woman and boy ashore in the dinghy somewhere amongst the sand dunes along the coast. But in the dark and in anything of a sea such a thing would have been quite impossible, for the banks and shoals are iron-hard and the most dangerous of any along the coast, as the litter of wreckage bears witness.

Pratt dare not have risked it. He would have been compelled to take the Mary How through the fisherman's swatchway and so right up into the upper harbour, where the fishing-boats lie, in which case her arrival would be duly noted by the port officials.

Within half an hour of his arrival he had proved that he was right. The chef du port had a note of her coming and a duplicate of her "permission of departure."

Before dusk that night he had seen young Borrodaile face to face. He had seen his photograph in a group in Mr. Hoskins' study. The boy, however, was now transformed. In place of sandshoes he wore a pair of woollen sabots. His light hair had been dyed dark, his skin was stained, and he wore the typical blue blouse of the French gamin. Also, as far as Blake could see, he seemed to be enjoying himself hugely, and was living in the charge of a fisherman named Jean Lepique and his wife in a small, neat cottage on the outskirts of the town, facing the long stretch of sand dunes.

Blake made no attempt to speak to him or approach him. But a few inquiries assured him that the boy was in good hands, and that the Lepiques were kind-hearted, respectable folk, who had a daughter "over there in England" who was "domestique" maid to a great English lady, very rich.

Of the woman—the woman of the sands and the earring—he saw not a trace. Nor did he expect to, for a strange idea, which was slowly becoming a certainty, was forming in his brain, and his face was grave and anxious as he hurried back to town as fast as boat and train could take him.

Within half an hour of his arrival he was being shown into Lady Mary Borrodaile's boudoir; and she rose to greet him eagerly. She was dressed in black, and her face was pale and anxious. Evidently the strain was telling on her. She was a tall, splendidly-made woman, with a low, broad forehead, a beautifully-cut, resolute mouth, and frank, fearless, thoughtful eyes—a strong, self-reliant woman, quick to think and act. But Blake fancied he could read in her eyes a haunting terror firmly repressed.

"You have news!" she said, coming quickly forward. "I can see it in your face. Tell me what you have discovered."

"Yes," said Blake gravely, "I have news for you, Lady Mary. To begin with, I have found something belonging to you." And he held out the turquoise earring.

She gave a queer, gasping breath. Then, quick as thought, she had slipped past him, locked the door, and pulled out the key.

"You have been—you have found him out!" she said in a tense whisper. And now the terror in her eyes was unmistakable.

"I have come from the Lepiques—yes; and I have seen him."

"My heavens!" It was a moan of pain almost inaudible. "And after all I ventured, all I risked and schemed and planned! What shall I do? What can I do?"

"But why did you do it?" asked Blake, eyeing her gravely.

"To save his life." She turned on him like a wild animal at bay. "And you—you must needs meddle and interfere, and by your diabolical cunning undo all the good that has cost me weeks of sleepless nights and days of torture. Yes, I did it; I admit it. I warned Dick to be ready, and I came and fetched him, and together we stole away. He, poor child, thought the whole thing was a joke, a piece of boyish play after his own heart, and 1 didn't undeceive him. I knew Holme well; we had spent a summer holiday there two years ago. 1 took him to the edge of the quicksand and made him throw away his cap, and I tore a link from his sleeve. Then I picked him up and carried him, covering my tracks by the incoming tide. A boat was waiting—a fishing-boat. The man was a good friend of mine, and I paid him well for silence."

"Pratt," said Blake. "He kept his word."

"We reached Dunquerque. I disguised Dick as best I could, threw the galoshes I had been wearing overboard, together with most of his clothes wrapped round a lump of iron. I bought him others, and took him to the Lepiques cottage. They are parents of my maid. I nursed her once through a bad attack of typhoid, and they would do anything for me. Then feeling that he was safe, I hurried back here, and all that I have done you have undone."

"But why—why?" demanded Blake.

"To save his life. More I shall not tell you. Since you have found out so much, find out that too," she added bitterly.

Blake rose.

"I must ask you for the key, Lady Mary. If you won't trust me I must do my duty to others—to his father."

For one moment Blake fancied that it was in her mind to strike him in her desperation. Instead, however, she held out the key. He opened the door.

"Mr. Blake!" she called sharply. He turned. "Mr. Blake, you are going to tell his father that you have found him. Promise me one thing. Promise me, on your honour, not to tell him where till you have seen me again. I would have kept silence if I could, but if I am forced to speak I must. I do not think I shall be," she added slowly.

"I promise," said Blake, and went downstairs.

MR. BORRODAILE, the great scientist, was in the big room at the back of the house, half study, half laboratory. A tall, gaunt man, with a massive, protruding brow, and deep-sunken eyes—not a handsome man, but a strong man—a power—with a dominating will.

He had aged a great deal since Blake had last seen him. His gaunt frame was shrunken, and he looked nervous and ill. He sprang to meet his visitor, however.

"You have come at last, Blake! You have found him, eh? I tell you the boy must be found. I can't got on without him—I can't work without him. Tell me quickly, has he been found?" He gripped Blake's shoulder in his excitement, and Blake, looking at him suddenly, felt his heart grow chill with apprehension, and a horrible sickening dread came over him.

"Yes, I have found him," he said very slowly. Borrodaile burst into a harsh cackle of relief.

"I knew it! I knew you would. The moment I heard the news I said Blake's the man. Blake's infallible. If the boy is above ground he'll find him. You see, it was so vitally important. How could I get on with my work? These absurd restrictions that they have nowadays are an absolute bugbear, a brake on anything like systematic research. One is hampered at every turn." His voice dropped to a cunning whisper. "He would have been home, you see, in a few days' time—I was calculating on that—and then I could have worked and worked, and in two—three—weeks I could have made sure. Parkinson, Le Maitre, with their twaddle about the nerve centres and the mid-lobe, are wrong, wrong, hopelessly wrong. How can they tell, eh? How can they, I ask you, with their rabbits and their guinea-pigs, and rubbish of that sort." His grip on Blake's shoulders tightened, and Blake drew his breath in sharply between his teeth; the nameless fear was coming closer and clearer.

"Think what a chance I was so nearly missing, if you hadn't found him for me! What man ever had such a subject, a young brain unclouded by worries or trouble, quick, responsive. In two weeks I could have wrested the secret from it—all its secrets. Surely a man may do what he likes with his own son, eh? They couldn't interfere with me there, could they? I should laugh at them—I shall, if they bother me, I shall laugh in their faces and say this is my son. I can do as I please, and I devote him to the enlightenment of the human race, to the honour of science, and to the study of the brain under such conditions as no man has ever had the chance of studying it before. See, I have everything ready. That is where I shall keep him. He shall be well fed, of course, to keep his strength up, for it will take me at least two weeks, and it would never do to have the experiment interrupted in the middle. Think of the honour, the fame! His name and mine will be handed down through the ages. There I shall keep him, you see, so that the work can go on at any hour, day or night."

Blake drew back with a strangled cry, and turned away from the gruesome contrivance of glistening steel and leather padding in the corner. The fear had him in its grip now, and he understood.

"Now tell me, Blake, tell me, did you bring him with you, eh? Can we begin soon—to-night—to-morrow—where is he?"

"Where, please Heaven, you shall never find him," said Blake hoarsely. "I'd rather be struck dead on the spot than tell you. Good heavens, Borrodaile, you're a raving madman!"

There was a growl and a snarl, and the maniac, self-confessed, hurled himself at Blake like a wild beast. The great brain, which for years had studied and brooded over lesser ones, had in its turn succumbed to some secret weakness which turned the calm, calculating scientist into a thing of bestial, blind rage and fury.

With the first rush Blake was borne backward, for Borrodaile, naturally a strong man, fought with the strength of half a dozen. But the struggle, though sharp, was short. There came a horrible scream, a rush of blood from mouth and nostrils, and with a heavy crash Borrodaile's body grew limp and fell.

He had burst a blood-vessel in his overworked brain, and collapsed. Blake looked up, panting heavily. In the doorway stood Lady Mary, looking in with horrified eyes. As her husband fell she came quickly in and shut the door behind her.

Blake knelt down and laid his hand on the prostrate man's heart.

"He lives! Be quick, we must send for help at once. Lady Mary, I must ask your forgiveness. I had no idea that—that things were as they are. If you had told me——"

"I have known it for weeks—months, almost," she cried dully; "but he was cunning—so cunning! None of the servants have any suspicion. For a long time I hardly suspected myself; but gradually it was forced on me that he—he meant to use the child for—ah, it is too horrible! So I stole the boy away. But I would have kept the secret of his madness if I could. He has been a good husband, and a good father, and he has made a name for himself which is honoured throughout Europe. I would give ten years of my life to spare him the shame of being seen a mental derelict, an object for pity, for he was a proud man—few knew how proud."

"He was my friend," Blake reminded her gently. "Perhaps we can keep the secret even now. Leave it to me. I will go and fetch two doctors whom I know, and who also know and honour him. Lady Mary, if I had told him that which I came here to tell, 1 should never have forgiven myself any more than you could have forgiven me."

Lady Mary looked at him with wet eyes.

"I should have trusted you," she said very low; "but I am only a woman, and I fought my best for my own."

"A very brave woman!" said Blake; and hurried away.

THROUGH the spring months of the year the good people of Dunquerque grew accustomed to seeing a big gaunt man with a powerful, clever face and a genial smile being wheeled about in a chair by Jean Lepique. By the side of the chair usually walked a tall, graceful woman, with soft eyes and ready, attentive hands. "La belle Anglaise," they called her amongst themselves, and with them, too, sometimes, but more often amongst the sand dunes or out in the fishing-boats, a sturdy, brown-skinned, fair-haired youngster in sabots, whose French, though fluent, was unmistakably English in its accent, and who had a voracious appetite for Marie Lepique's tartines.

"I shall be fit for work again soon, Molly," the man would say now and again, and she would answer:

"Not yet, dear. Be patient for a little while. Wait till Dr. Parkinson and Mr. Blake run over to see us at Easter. You promised to wait till then. See, here comes Dick, with some fish of his own catching."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.