RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

BLAKE was bored to distraction, and from sheer want of something to do he slammed the door of Messenger Square and went off to buy a new hat. For him it was really quite a nice hat—a soft felt one. As a rule, he was careless about such details; and there the matter would have ended, but for the fact that on his way homewards he came face to face with Nurse Elma.

She was an old acquaintance—friend, rather—of his, and had, indeed, nursed him after his accident in the Thuringen affair.

She was a tall and extremely pretty woman, quite young, with waving masses of chestnut brown hair, showing here and there a glint of gold in the sunlight, and deep violet eyes.

But Blake noted that under the eyes there were unusual deep shadows, and her whole manner suggested an unaccustomed listlessness and apathy. As a rule, she was alert and brimming over with health and good humour, with a smile and a flash of white teeth for everyone.

Her mere presence in a sick room had a tonic effect on her patients. Blake looked at her sharply as he shook hands.

"What's the matter with you?" he said, almost, gruffly, for she was a favourite of his, and it annoyed him to see her looking ill. "You've been overworking yourself I suppose; wasting your health and good looks on a lot of peevish, discontented invalids."

"You were a bit of a bear yourself, you know, for a day or two after they had mended your leg, and removed a few superfluous bullets from various portions of your anatomy," she retorted, with something like a return to her old manner. "I'm not overworking."

"Over-worrying then!" growled Blake.

She darted a quick look at him, and her face clouded once more.

"I am worried—much worried. It's about one of my patients. In spite of all I can do he seems to get worse; but for the life of me I can't make out what is the matter."

"A friend of yours?"

"A very particular friend." She flushed slightly and smiled a little drearily as she spoke. "He is in Dr. Mason's private nursing home, where I work. It was I who induced him to come there, so that I might look after him. It seemed a simple enough case at first—low fever, an ordinary typical case, with ordinary symptoms. But for the past three weeks he has been getting weaker and weaker, in spite of all we can do."

"How long has he been ill?"

"Oh, the actual fever left him soon after he came, and he began to mend; and then all of a sudden he took this turn for the worse. Would you care to come and see him? Dr. Mason won't be back till seven at the earliest; besides, any friend I choose to bring would be admitted without question. Dr. Mason allows me to use my own discretion in everything."

"Very well," said Blake, "I will come if you like," and turned and walked beside her.

Nurse Elma's friend proved to be a good-looking man of about thirty-two, a well-built, strongly-made fellow by nature, but sadly exhausted and pulled down; so much so that he could barely raise his arm to shake hands with Blake.

The latter took a chair and sat down by his bedside, whilst Nurse Elma, having gone to take off her outdoor things and go her rounds, was absent. The two men chatted for a little while on indifferent topics, and the sick man plucked feebly at the counterpane as he gave his answers to Blake's questions. Suddenly the latter bent forward staring, and, as though fearing that the movement might have alarmed the invalid, bent down and fumbled with a boot-lace.

"They keep your rooms rather dark here," he said. "Mind if I pull up the blind? That's better."

As he spoke Blake passed swiftly behind the head of the bed towards the window, and glanced back over his shoulder, and again his eyes were riveted on the man's hands.

"Ever been in the tropics—Central Africa, or, anywhere?" he asked casually.

The sick man smiled.

"The only time I've ever even seen the sea was last year, crossing from Dover to Ostend. I am afraid I'm no traveller. I'm an architect by profession, and have been too busy to indulge much in holidays."

"Ah!" said Blake, "I've been rather a rambling sort of animal myself. I think I've stumbled into most corners of the earth at one time or another. Extraordinary how the thing becomes a habit; meet a lot of strange sort of people too. I remember once coming across a Sir Herbert Harrington—same name as your own, by the way—at a kraal right up amongst the Matoppo Mountains, and I wondered if by chance he was any relation of yours?"

He glanced keenly at the sick man's face.

Harrington shook his head.

"I never heard of him," he said drowsily; "he's certainly no connection of mine."

"Ah, well, it's not an unusual name," continued Blake, and went on with his anecdote, in the middle of which Nurse Elma came quietly in.

Soon afterwards Blake rose and took his leave. In so doing he was guilty of, for him, an extraordinary piece of clumsiness. For he tipped over the bed-side table on which stood a bottle and a medicine-glass, and both were broken. He stooped quickly to try to save them; but neither Nurse Elma nor the sick man noticed that in doing so he whipped a little empty phial out of his pocket and secured about a teaspoonful of the medicine from the lower half of the bottle and stowed it carefully away before apologising for his carelessness, he took himself off.

Nor did they have the chance to see the deep frown on his face as he strode quickly westwards.

By the midday post he got a letter from Nurse Elma which made him frown more than ever.

"You have got me into disgrace," it ran. "To begin with, poor Mr. Harrington is much worse; and secondly, Dr. Mason, who takes the deepest interest in the case, was furious with me for bringing a visitor to see his patient, especially one 'who didn't know how to behave in a sick room, and upset things.' These are his own words, quoted for your benefit. So now you know what you have let me in for.

"Seriously, dear Mr. Blake, I am so worried I hardly know what to do. Though I didn't tell you in so many words, I suppose you guessed that Mr. Harrington and I are engaged; we were, in fact, to have been married in the spring. But I am beginning to lose all hope. Can you meet me to-morrow afternoon and talk things over? Somehow, talking to you always seems to do one good.—Your sincere friend."

All that day Blake busied himself poring over his test tubes and his microscope alternately, and the harder he worked the deeper grew the frown on his face. He scribbled a short note promising to meet Nurse Elma, and then did a thing which he had not done for months. He changed info dress clothes and made his way towards club-land.

There was a man he wanted to find above all others, and that man was Sir Herbert Harrington.

He knew by the papers that the latter was in England again, and he knew his man's haunts pretty well.

He inquired for him at his club, a place where many travellers, explorers, and mighty hunters congregate during their fleeting visits home; but Sir Herbert was out.

He looked into one or two favourite restaurants and at last found him dining alone at a small table in the corner of one of the big cafés. Blake handed his hat and coat to the attendant, and, waiting till Harrington was busy talking to a waiter, slipped quietly in and seated himself at a table some little distance away. He waited till he had got through his soup and a glass of wine, then suddenly glancing up, contrived to catch Harrington's eye, and waved to him. The latter nodded back, and Blake strolled across to the other table.

"How are you?" he said. "Bit different from our last meeting, as far as surroundings go."

"Grub, too," said Harrington, with a laugh. "Goodness! how tired a man gets of tough antelope steak and stale biscuit. To appreciate a good meal a man ought to live out in the back blocks of the world for a month or two. Tell your waiter to shift your dinner over here."

Blake signed to the man and soon he and Harrington were chatting volubly about strange men and places.

Harrington was full of good spirits and anecdote; but Blake, watching him closely, fancied that at times his manner was rather forced and that inwardly he was both anxious and uneasy.

He had certainly aged a good deal in appearance, and there were lines on his face which had not been there before.

However, he seemed genuinely pleased to have someone to talk to, and they sat long over their meal.

At last he rose and suggested looking in at a music-hall.

"Just as you like," said Blake. "By the way," he added casually, "talking of people one comes across did you ever happen to meet a Doctor Mason—Mason the specialist, you know?"

Harrington's cigar was half-way to his lips and Blake's sharp eyes noted the quick tremor of the hand, instantly controlled. Harrington's nerves had been too often and too thoroughly tested to be easily upset.

"Mason," he said slowly. "N-no, I don't think so. Doctor men are not much in my line. Why?"

"Oh! he's a bit of a lion these days. Invented some wonderful cure or something. Ah! here's our hansom."

Harrington continued to chat indifferently on various subjects. Suddenly he glanced at a clock they were passing, and gave a sharp exclamation.

"By Jove! I'd clean forgotten," he said, in a vexed tone.

"What's the matter?"

"I say, Blake, I'm awfully sorry," he said hurriedly, "but I've just remembered I'm due at the Royal Geographical to meet a man; it's an important engagement, too, or I wouldn't bother. I hope it won't spoil your evening, but I'm afraid I shall have to chuck the music-hall, after all. We must have another evening later on, and a long yarn. You know where to find me—the old address."

"All right," said Blake. "No, don't you get out; take the cab on, as you're late. I'll walk."

He stopped the cab and got out.

"Good-night!" he said with a nod, and turned away with a grim smile on his face, as he gave the driver his directions.

Harrington said nothing, but flung his cigar savagely away and sat staring straight in front of him.

Blake met Nurse Elma the next day, as he had promised, and they went to a quiet little restaurant for tea.

Her face was very white, and the rings under her eyes had deepened. It was clear that she had spent a sleepless night.

"Well?" said Blake, curtly.

She struggled with a choking sensation in her throat.

"I've almost given up hope," she said in a low voice. "Mr. Blake, he's sinking fast—even Dr. Mason looks grave and worried. He hasn't actually said anything definite; but I know what it means when he looks like that. I have learnt to read his face. He can't bear to lose a patient; in all the time he has had his private house, we have only lost two cases."

"What does he attribute the change to?"

"Loss of stamina and lack of fighting power. He makes us give him strong beef essence and a little brandy every two hours. To-day, his orders have been changed to every hour; and yet, in spite of it all, Horace is getting rapidly weaker and more lethargic. He seems to have no will-power to fight against the disease."

Blake's lips tightened as she mentioned the treatment prescribed, but he said nothing.

"Can't you suggest anything—can't you help?" she asked. "Somehow, I always seem to think that you can do anything; and though you are not a doctor, yet I know your original work has carried you further than many of the men who are at the top of their profession. Not that I am saying anything against Dr. Mason. Everyone knows that he is one of the cleverest men of the day, and no one could have been more kind or more attentive. He has spent more time and trouble on Horace's case than on all his other patients put together. He even sat up with him for two whole nights."

Again Blake's lips tightened.

"I think I can help," he said quietly. "But if I do, mind you, you must do exactly as I tell you, and you must ask no questions; and,above all, it's most important that Dr. Mason should not know. It's a gross breach of etiquette for me to interfere, of course, and we don't want to upset him and make him angry."

Nurse Elma nodded.

"In the first place," continued Blake, "you must send me two or three of Dr. Mason's usual medicine bottles, the same size and shape as those in which Harrington's medicine is made up. That must be done the moment you return. I will put up some medicine of my own in them, which in colour and taste will be identical with that he is taking at present, and send it back to you. Then, as Dr. Mason gives you a new bottle, wait till he is out on his rounds, and send it straight to me by messenger-boy. You understand?"

"Yes, I understand. I must be careful, though, for if he found out, he would dismiss me on the spot, and then you would be unable to do anything for Horace. See how I trust you?"

"So you must—you must trust me absolutely in every detail. Now, I suppose you have at least one nurse on the premises who is a fool?"

Nurse Elma nodded and smiled rather drearily.

"Oh, yes; there's no.difficulty about that."

"A dull-witted, thoroughly reliable, machine-like fool, who would obey orders unquestioningly if the house was on fire under her?"

Again she nodded.

"Good! Who has the ordering of the sick-room routine?"

"I have."

"That's all right, then. You will put the reliable fool on day duty for Harrington, and you will take night duty yourself. How is the brandy administered?"

"A bottle is kept in a cupboard in the room, and a little is poured out into a tumbler weakened with water, and poured down his throat."

"Very well. When you go back, make some strong toast-water or weakish tea, and be sure you get the colour right—it must be the same as the brandy. Pour the latter away and fill the bottle with your tea. If she is a mechanical fool, she won't notice the difference, for the bottle itself will still smell of brandy, and that will satisfy her. Do as I tell you, and we'll have Harrington on his feet again inside a week. In case anything goes amiss, however, watch carefully the backs of his hands. You will notice that there is a curious mottled appearance on them. If that grows more pronounced, or the lethargy shows signs of developing into coma or collapse, send a messenger-boy for me in a cab at once. Lock yourself into Harrington's room, and allow no one to come near him, or give him anything to eat or drink till I arrive. For if I get that message, I shall come in spite of a dozen Dr. Masons. By the way, how do you and he get on— apart from professionally, I mean?"

"We are friends—great friends. He has always treated me with the utmost kindness. In fact, I've never known anyone more kind and thoughtful. It's especially surprising in him, too, for with most people he is curt almost to rudeness, and very dictatorial."

"Humph!" said Blake, and looked at her sharply. "Now then, you run off—the less time we waste the better. I shall expect those bottles in an hour and a half. You shall have them by six—back again and filled. Good-bye!"

Blake walked back to Messenger Square at a pace which made several people turn and stare, and anyone who knew him intimately would have argued from that that his mind was working at top speed.

Having filled and despatched the bottles, he hurried out again, and didn't return till close on midnight.

Next day he received a hasty pencil scrawl from Nurse Elma:

"He is already better," it ran. "I am just off duty, and though it is past seven in the morning, I feel that I must write and tell you, and thank you for the new hope that you have given me. Dr. Mason, curiously enough, was in a terrible rage about something last night. He was rude to me—a thing he has never been before—and almost brutal to the other nurses and some of the patients. He asked us a whole string of questions, and amongst other things he asked me the name of the visitor I had brought to see Horace. I told him your name, and he was more angry than ever. I have never seen him so angry; he didn't rave and storm, as some people do, but he gave me just one look, as if he would have liked to kill me on the spot, and turned away without another word; but his face was absolutely livid. I have made arrangements to have the bottles sent you, as you wished."

Three days passed by, and on each of them Blake received a parcel containing a full bottle of medicine, which he stowed carefully away in a locked cupboard. On the fourth he made up his mind to go and see Sir Herbert Harrington at his rooms.

Rather to his surprise, he found him in and alone.

The latter offered him a drink and a cigar, both of which he refused, and began to chat easily and naturally, apologising for his abrupt departure on the previous occasion.

"You see, I'm off again on another jaunt next month; getting tired of doing nothing, and I've always wanted to have a squint at Ecuador and round that way. The fellow I was to meet gave me a lot of valuable hints, and what's more, I fancy I shall be able to make money over the deal, and that's something in these hard times."

Blake yawned.

"I suppose it's fashionable nowadays to make a poor mouth; but for you to do it is surely absurd. You roll in money, and there's a lot more to come to you, isn't there?"

Harrington shrugged his broad shoulders.

"One can't have too much, in my opinion," he said smiling. "The more one has the more one wants; besides, I managed to drop a good deal over a mine. The gold's there, right enough—I made sure of that myself; but it was the old tale, you know. A syndicate stepped in and played a monkey and parrot tune with the shares. By the way, you remember that Jason or Mason fellow you were asking me about the other day—the doctor man?"

Blake nodded.

"Well, it's a small world, as the old saying goes, and I find the chap is actually a member of my own club. Must have been elected whilst I was away for that long African trip, I imagine. Seems a decent chap, and plays a rattling good game of whist."

"He is very clever, by all accounts," said Blake. "I've never met him personally. I believe he originally made his reputation as a toxicologist."

Harrington reached for a tumbler, and poured himself out a whisky and soda.

"Did he? Ah, I daresay. Certain you won't join me?"

"No, thank you. Yes, I am told he made some remarkable experiments, and he did some work on snake-bites and sleeping sickness, which are rather favourite studies of my own. You must introduce me some day, Harrington."

After another few minutes he rose leisurely and took himself off.

He had barely reached the street when Harrington also rose.

"That settles it!" he exclaimed. "Curse the meddling fool. Jameson—Jameson, you idiot," he bawled through the door. "Pack my trunks—all of them. We leave for Antwerp on the night mail. Tell them downstairs that all letters are to go to the club, and that we are off to Paris and the South of France—Algiers—anywhere you like, so long as it's not the truth. Take the gun-cases and rifles along, and have everything in readiness in good time."

He glanced at the clock. "Friend Blake has made a blunder for once. Thank goodness, it's not four yet, and he's left me time to get to the bank."

But Blake, strolling slowly down St. James's Street, had not blundered. He had calculated the time, on the contrary, to a nicety, and he smiled as, a little later, he caught sight of Sir Herbert Harrington's face as he whirled past him on his way to his bankers.

He also glanced at a neighbouring clock. It was just a quarter to four, so, having done what he wanted to do, he turned his face homewards.

The parcel containing the bottle was awaiting him as usual. Each bottle contained exactly six doses, sufficient for the twenty-four hours. He took oft the wrapper, and held it up to the light. Suddenly he gave a cry of anger and dismay.

The bottle returned was one of his own, instead of one of Doctor Mason's. Nurse Elma had confused the two.

In a flash he was down the stairs and out in the street again, and had hailed a hansom with a likely-looking horse. He scribbled a note on a leaf torn from his pocket-book, and gave it to the man.

"Drive to that address as hard as ever you can go," he said, "and give that note to a lady answering to the name of Nurse Elma. You are to give it to her in person, mind. Then drive straight back to Messenger Square. I shall be on the lookout. Tell her to come just as she is. Every second is of importance. There's a sovereign for you when you return."

"Right, sir!" said the man, and went clattering off.

Blake had been accustomed to many a long, anxious wait. But never before had time seemed to pass so slowly as he waited for Nurse Elma.

Inside the note he had written only four words, but he knew they would suffice. They were: "Come at once—imperative."

At last she did come. Blake, waiting in the darkness, saw her cab a long way off.

He snatched her out almost before it had stopped, and flung the man a sovereign. "I may want you again—wait," he called over his shoulder, and hurried Nurse Elma into the house.

"What is it?" she gasped. Her voice sounded dull and tired, and she half-reeled against him. He caught her by the arm, and half-led, half-dragged her to the room.

"What is the matter?" she asked again.

"The matter is that someone has blundered, and if we don't take care the blunder may cost Harrington his life," he snapped curtly.

"Do you see this? This is the bottle you sent me this morning. And do you see this? This is a bottle of my own mixture, for here on the shoulder of it is my little private mark, a small scratch made with a diamond. It was the only identification mark I dare make, for a man like Mason has sharp eyes. How did you get the two mixed up?"

Nurse Elma sank into a chair.

"I can't tell," she said, staring first at the bottle and then at Blake. "When the medicine was sent up by Dr. Mason, as usual, I put it away at the back of the cupboard, where other bottles and disinfectants used in the sick-room are kept, and kept yours on the table by the bedside. I was just going off duty. Later, during the dinner-hour, when I had rested, I went in and had a chat to Horace, and took the bottle from the cupboard and sent it off by messenger."

Blake frowned.

"When you left it on the table it was a fresh bottle quite full?"

"Yes. I had only just put it there when the day-nurse relieved me."

"Then how do you explain the fact that there is one dose missing?"

She stared at him helplessly. "I can't. The time for him to have his medicine was an hour after I left the room, the second dose four hours after that, just when I went to see him—and the third shortly after six in the evening. I can't make out how the mistake has occurred, for I put Dr. Mason's medicine away myself before I even unlocked my bag to produce yours. Of that I am positive. And Nurse Read could not possibly have changed them back again, for the simple reason that she did not even know of the existence of any but the one bottle."

Blake thought a moment.

"What time does Doctor Mason go his rounds?"

"Usually about ten or half-past in the mornings. After that he is uncertain."

"That would be after Nurse Read had come on duty?"

"Oh, yes!"

"That explains it then. I see it all. He came in, saw Harrington, and resolved to hurry matters up, and exchange his medicine for a stronger one. He went down, and mixed up a prescription the same to look at as this, but a great deal stronger. This he sent or brought to Nurse Read, and told her to change it for what she was using. She did so, and placed my bottle in the medicine-cupboard where you found it, mistaking it for the one you had placed there yourself. You would be in a hurry, not wanting to be seen, and consequently did not notice that there were two of them."

"I suppose that must have been what happened. I am very sorry. I will see that it doesn't happen again. After all, it was hardly my fault; and I don't suppose one or two doses of the other will make much difference."

"Make much difference! Good heavens! Woman, are you blind? Can't you see? Hasn't it dawned upon you that Mason has been deliberately and systematically poisoning the man for weeks?"

Nurse Elma sprang to her feet with a cry of horror.

"Poison!" she gasped. "Mr. Blake, you must be mad. Dr. Mason would never dream of such a thing. From first to last he has taken the greatest pains with the case—partly for my sake, I believe, because he is kind to me, and knows how much it means to me. It was his skill I felt in doubt of, never his honesty. And I came to you. But he would never think of using poison. Why, just think what it would mean to him. What could be his object? His great boast is that he has lost fewer cases than any doctor practising, and you suggest that he is deliberately trying to lower his own record. I tell you he would never dream of such a thing."

"No," said Blake, with grim irony. "He wouldn't. He is a man, and a strong man. He wouldn't dream of it; he has done it. And what is more, he has done it uncommonly cleverly, increasing the strength of the dose day by day. That is why, finding Harrington better this morning, against all his expectations, he determined on the spur of the moment to increase the dose still further, and changed the medicine."

He looked at his watch, and his face hardened.

"You said his third dose—that is, his second out of the new bottle—would be given him at six. It is past six now. He has taken two doses of that strength. Nurse"—his voice became more gentle—"nurse, if we save him you must be thankful that the age of miracles has returned; and we must go at once. A third dose would place him beyond all human aid."

Nurse Elma stared at him dry-eyed, with a face whiter than any sheet; her mouth opened, her lips parted to give vent to words that would not come. Then suddenly, to his amazement, she burst into a peal of hard, bitter laughter.

He started back involuntarily in his surprise.

"This is no time for hysterical nonsense," he said roughly. "I have seen your nerves steady as a rock during a critical operation. Stop playing the fool at once. Stop, I tell you!"

The harshness of his voice seemed to bring her to herself effectually.

"It is not hysteria," she said calmly. "It is the mockery of it all, and something which I have just remembered, that I was laughing at. We may save him yet. Heaven grant we do, for this will not be his second dose, but his first. He was so much better when I went to see him to-day that he said he was sick and tired of medicines, and would not take any more. I coaxed him and urged him, but all to no purpose. I was sitting with him whilst Nurse Read ran down to dinner, you remember. But nothing would induce him to touch it. In fact, he was well enough to get quite cross about it. So in the end, to tease him partly, and partly to amuse him, I took the dose myself, and I remember now that as I poured it out I noticed that the bottle was full."

Blake leapt forward with a hoarse cry.

"You took it—you! Do you know that one dose of that, to a woman like you—a dose of the strength he must have made it—would be fatal?"

She looked him straight in the eyes, and smiled bravely.

"If it has saved Horace I don't mind very much. I wish—I wish we could have had a little happiness together first, that's all."

"You don't mind, don't you," growled Blake angrily. "Well, let me tell you that I do. The world wants a few more women like you in it. Thank goodness, you told me in time. It won't have got a firm hold on you yet. For he dare not have made the dose too strong. Pull up your sleeve higher—higher still—right up to the shoulder, and come nearer the light. You've got plenty cf pluck—this is going to hurt."

She smiled at him again.

"I can stand a good deal," she said.

Blake selected a bright keen lancet from a closed case, and carefully uncorked a small bottle, the stopper of which had been tied down.

Then, taking the nurse's firm, white arm in his left hand, he gripped it tightly.

"Set your teeth," he said, grimly; "it's your own fault—you oughtn't to have touched the stuff."

And he plunged the lancet twice into her arm, doing it swiftly and firmly so as to minimise the pain.

She gave a little gasp at the first jab, but resolutely bit her lips.

The rich, warm blood trickled slowly down the satiny white of the skin. Blake dipped the lancet into the bottle, and jabbed it once more into the open wounds.

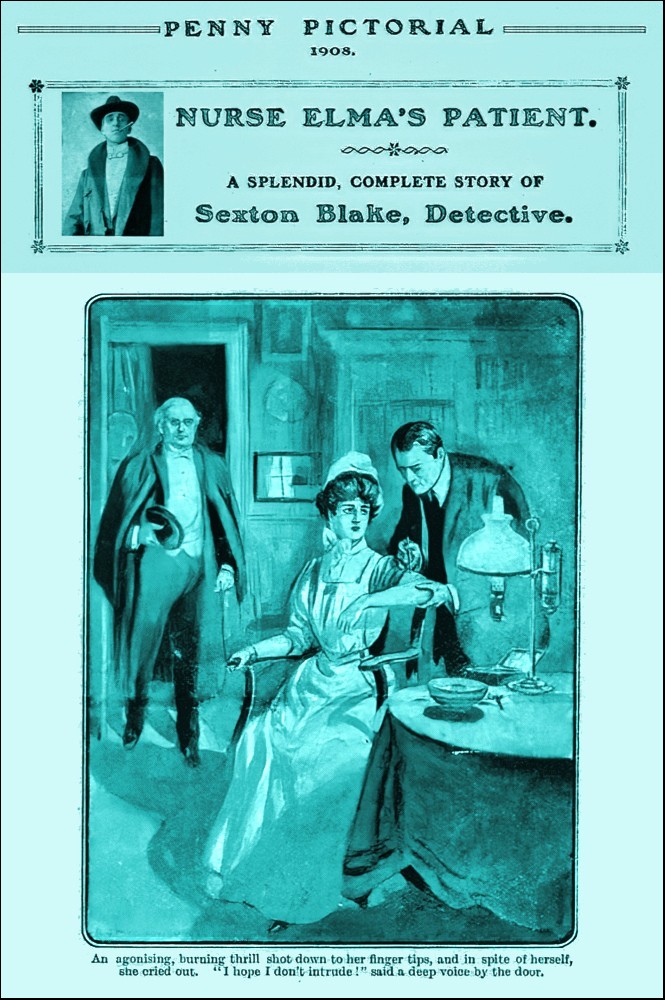

An agonising, burning, thrill, succeeded by a glowing sensation, shot down to her finger-tips, and in spite of herself she cried out.

"I hope I don't intrude," said a deep voice from the shadows by the door.

Both glanced up, and saw the well set-up, sturdy form of Dr. Mason standing there in dress clothes, his white shirt-front gleaming in the light and his hat in his hand.

"Dr. Mason, I presume," said Blake. "T have just been undoing a little of your handiwork. It may interest you to learn that Nurse Elma drank a dose of the medicine you sent up this morning for Harrington."

For an instant Mason's face seemed to shrivel and grow old, and he clutched at the door-post to support himself.

"Good heavens!" he said huskily; then, very low, "Elma—Elma!"

There was no mistaking the longing and hopeless yearning in the voice.

He pulled himself together in an instant.

"What have you done for it?" he asked Blake harshly. "It was a forty-per-cent solution, man! Tell me, what have you done?"

"All that is necessary," said Blake quietly, "judging from those specimens of your prescriptions on the shelf there. I reckoned on your risking as high as a fifty-per-cent dose, and took stringent methods accordingly. You can be quite easy; she will come to no harm, and for proof I have kept Harrington alive in spite of you, for close on a week."

"Ah, so it was you! I thought as much. Thank goodness, Elma came direct to you. Mr. Blake, you have saved the best woman in the world. The world and I owe you a debt of gratitude."

The tone was light; but his eyes remained on the woman's face as though they could not leave it.

She turned to Blake.

"I don't understand," she said piteously.

"It is like this," said Blake—"the moment I saw Harrington, and, above all, his hands and lethargic state, I knew that he was suffering from a certain poison known as 'alouquine.' It is a drug used by the Isanusi, or witch doctors of a mid-African tribe, and in my opinion its action is directly connected with the disease berri-berri, or sleeping sickness, though this I have not yet proved.

"I asked the patient if he had ever been to Africa—he had not. I also asked him whether he had ever heard of a certain Sir Herbert Harrington, and again he had not.

"Now the peculiar thing about alouquine is that it is a very rare poison, quite unknown over here, and I was positive that only two men in all Europe possessed so much as a drop of it—or a grain of the nut from which it is prepared. One man was Sir Herbert, the other myself. Our specimens were obtained at the same time from the same man, and we afterwards travelled together for awhile. Taking that fact, together with the similarity of the names and a certain knowledge of Sir Herbert's character, I couldn't help thinking that I had found a clue—in spite, nurse, of your friend denying all connection with Sir Herbert.

"I went in chase of my man, and found him. I also found that he knew Dr. Mason. He denied it; but not definitely. It was his face that betrayed him, and he realised it, and made an excuse to get away from me as quickly as he could. That meant that a third man had knowledge of the drug, and that was Mason here, in whose house the poisoned man lay. I was sure that Sir Herbert would warn Mason."

"Quite right,"said the doctor, in his deep voice; "he did—he was scared."

"And you, doctor, were not, because you had a colourless, odourless poison unknown to the pharmacopoeia—defying known analytical methods, and, given in cumulative doses, presenting all the symptoms of death from exhaustion. On the occasion of my visit, you remember I knocked over the bottle and broke it. I also carried away a specimen of the contents, which I examined.

"I was sure of my grounds then. Through Nurse Elma I substituted antidote for poison, and your own bottles were sent to me daily.

"Another curiosity about alouquine is that stimulants and meat accelerate its action. I learnt you had ordered the man concentrated beef and brandy at short intervals.

"The one question remaining was motive. Yours Nurse Elma herself unconsciously revealed to me. You were in love with her, and she with Harrington. Sir Herbert's, I was certain, was money; but whose? I made inquiries, and found a certain very old lady, a Mrs. Anderson, a confirmed invalid, very wealthy and scarcely likely to live six months—she was Sir Herbert's aunt, and he was her presumed heir. He had left England under a cloud, I knew, and I soon found out that the old lady, having paid his debts and a big lump sum down, had altered her will in favour of a remote connection whom she had never seen and barely heard of—Horace Harrington, in fact. He was reported to her as hard working and industrious, and she cut Herbert out of her will in his favour, with this proviso, that should he, Horace, die first, the money should revert to her nephew.

"When I knew this, and that you, Dr. Mason, and Sir Herbert were members of the same club, and had been together a good deal lately, the case was complete. I did not wish to involve Harrington in this—later I shall deal with him on a more definite charge. I called on him this afternoon, dropped a word or two about poisons, and he took the hint, and is by now on his way to the Continent. You, being the braver and stronger man, relied on your reputation to carry you through. In fact, without the evidence of these bottles of yours, and Nurse Elma, I don't believe a jury in England would have convicted you had you succeeded—and of their existence you were ignorant."

"Quite," assented Dr. Mason. "My first suspicion of urgent trouble was half an hour ago—just as I had finished dressing, and learnt that Nurse Elma had left my home in a cab which had been sent for her. I guessed, of course, that she had come here, and followed, meaning to bluff the matter out. As it is——"

He smiled.

Blake looked at him with raised eyebrows, and the two men exchanged glances.

"You had better satisfy yourself," said Dr. Mason, and he fumbled in his waistcoat pocket, finally producing a small brown soft-shelled nut.

Blake waved it aside.

"Your word is more than sufficient, and—it will be the best way, don't you think?"

"Much. The loser should leave the table gracefully, eh! Might I ask you for a whisky-and soda?"

Blake handed him one in silence.

Dr. Mason raised his hand to his mouth, and placed the nut on the tip of his tongue, then drained the tumbler at a gulp.

"There is, you see, no deception, as the conjurers say." He smiled cynically. "After all, I haven't enjoyed life much."

Blake's face was pale but very stern.

"It is a pity," he said gravely.

The doctor shrugged his broad shoulders.

"I am paying for the cake; but I got not so much as a slice."

Nurse Elma gave a sudden, choking cry, and ran forward with outstretched hands.

The doctor's face twitched for a moment.

"Not now, my dear. I have played my stake and left the table. In ten—twelve hours at the outside, it will be over. I have twenty men's deaths creeping into my system. It won't take long. Think kindly of me if you can; and you were well worth the—the end. As Mr. Blake says, this is the best."

He stooped his great, ponderous body and kissed her arm below the lancet marks.

"Good-bye, Elma," he said; then, raising himself he turned to Blake. "And to you, too, good-bye. I shall dine at the club—a good, solid dinner, and a bottle of burgundy should be the treatment most suitable, eh?"

Blake's eyes gleamed for a moment, not unkindly.

"You are a very brave man. It is a pity. Good-bye!"

"Come, nurse," he added, as the doctor passed out, "we must go, too. We must go to your patient."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.