RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

BLAKE read the telegram without any particular enthusiasm:

CAN YOU COME STRETTON STREET, LIVERPOOL, AT ONCE CONCERNING DEATH OF ANDREW CRAIG, AS REPORTED IN MORNING PAPERS—CAN GUARANTEE FIFTY POUNDS EXPENSES.—JANET FORD."

On a second reading it occurred to him that Janet Ford was an extremely business-like woman, with a clear head on her shoulders, and a proper sense of caution. Had the telegram come from a man he would probably have answered in the negative; as it came from a woman, however, after a little hesitation, he scribbled an answer announcing his arrival in the late afternoon.

At the station he bought several dailies, and scanned them leisurely for a report of the case in question.

The first one gave it a paragraph headed, "Drowned in the Fog."

"Early yesterday morning a dock boatman, on coming alongside one of the quays in a heavy mist, was horrified to discover the body of a man, apparently a sailor or marine engineer, being slowly washed to and fro in the angle formed by the quay wall and the steps.

"The body was that of a strongly-built man of about thirty, and had evidently been in the water for some hours.

"Subsequent investigations proved him to be a man known as Andrew Craig, second engineer on board the steamship Hotspur, of the Greener Line, which had come into dock homeward bound from New York the previous day.

"Craig, though on shore leave, was sleeping on board by arrangement.

"As will be remembered, on the night before last, a dense fog lay over the whole of the river district. He is known to have had supper ashore with friends, and afterwards he was seen having a drink in the bar of the Red Lion.

"It is supposed that in the darkness and fog he must have lost his way and inadvertently fallen over the quayside, stunning or disabling himself as he fell—for he was known to be a powerful swimmer.

"This theory is borne out by the fact that there is a nasty gash on the left cheek, and a contused wound, such as might have been caused by a fall, on the back of the skull.

"There seems to be no suggestion of foul play, and the deceased, when last seen, was in the best of health and spirits."

The other accounts were substantially the same—except one. In that the barmaid of the Red Lion stated that Craig had remained smoking and chatting till closing-time, and then, saying good-night, went out alone. The report proceeded:

"Ten minutes later she also left, as she was living out, and she distinctly saw Craig talking to a man with a silk hat, a big fur coat, and evening dress. He was a tall man, and the two seemed to be speaking excitedly, for Craig shook his head several times emphatically.

"She noticed them particularly, for they were standing immediately beneath a street lamp which shone full on Craig's face—also it was most unusual to see a man in a dress suit and fur coat in that district, especially at such an hour. She could not attempt to describe the man. for his face was in deep shadow as she passed, but she could see the white gleam of his shirt-front through his partially open coat.

"The streets were very deserted at that time, owing to the public-houses being closed and the inclemency of the weather—and she is positive that one of them was Craig."

Blake laid the paper down and stared abstractedly out of the window.

It was useless to attempt to form a theory until he knew the facts, such as they were. He concluded that Janet Ford was one of the friends of the supper party. In this he was right.

Stretton Street proved to be a short row of rather desolate-looking lodging-houses, with here and there a small shop of the general variety.

Janet Ford's turned out to be one of the shops, distinguishable from its neighbours by its superior cleanliness and air of tidy comfort.

On one counter were daintily-arranged piles of boxes of unwholesome-looking sweets carefully covered over with gauze, and backed by rows of mineral-waters.

The other was given over to newspapers, pipes, and picture-postcards.

At the back opening of the shop was a cosy-looking sitting-room, with a small piano, and a cheerful fire burning in the grate.

Janet Ford herself was a dark, strikingly handsome girl, dressed all in black. Her face was pale, and there were traces of sleeplessness round her eyes. But she was full of pluck, and endowed with a will of her own.

"Mr. Blake?" she asked, peering through the dusk into the street.

"I have come in answer to your wire," replied Blake.

She led him inside to the back room and pointed to a photograph in a frame on the mantelpiece.

"That is Andy," she said. "He had supper here on the night he was murdered. He and my sister Lucy were to have been married next month; as it is, I think his death will kill her, too. We are poor, of course, but the shop does well. Find the man who murdered him, and I'll sell the place up, if need be, to pay you!"

"But my dear young lady——" began Blake, taken a little aback.

She cut him short, her eyes blazing with anger.

"Wait," she said more calmly. "You think it strange that a girl like myself should be so vindictive—but my sister is all I have in the world. I have had to be sister and mother to her, too. She was passionately fond of Andy, and he of her, and now she is lying upstairs, half off her head with grief. Do you wonder that I want to make the man who is responsible for all this pay for it? Besides—though that is a smaller matter—in a short time Andy would have been a rich man—very rich—and it was for that they killed him!"

Blake looked at her sharply. Here, at any rate, was something tangible to go on.

"First of all," he said quietly, "will you kindly tell me why you persist in saying that he was murdered? Why mayn't the whole thing have been an accident, as the papers make out?"

Miss Ford shook hew head.

"It was no accident, Andy could have found his way to his ship blindfold. But it's not that alone that makes me so positive—it was something he said, half in jest, at supper-time. His words, as nearly as I can remember them, were: 'You'll have to look after me very well now, Lucy, my dear. I've become very precious all of a sudden. I've got something here'—and he patted his breast pocket—'which a good many people would give their heads for. I expect if they knew it they'd lay up for me one dark night and do for me, in order to lay their hands on it. I know one fellow who would, anyhow.'

"I spoke to him rather sharply, for Lucy is a nervous sort of girl. But he only laughed and said he was quite able to take care of himself and his fortune, and that, anyway, the risk would be over in a day or two."

"He could not have meant money—do you know what he referred to?"

Miss Ford hesitated.

"N-no—at least I think I do. Andy, as you know, was an engineer, as was his cousin Duncan, who acted as third under him.

"They were both very clever and almost inseparable, and for years I know they have been working on some sort of invention—some machinery thing. I am only a girl, and don't understand about that kind of thing. But I do know they succeeded beyond their wildest hopes just before tho Hotspur sailed for New York last time.

"They were both very reticent, being Scotch, but Andy told me that before the year was out he would be able to give up the sea, and that he already had an offer of an enormous sum of money—fifty thousand pounds, I think it was—if he would sell his idea. He also told me that he couldn't before he got back, and got certain official papers, and that then he only wanted to sell a half-share, and that Duncan and he would divide the rest between them. And there is this. It came the morning after his death—he often used to have private letters sent here. I opened this one as soon as I heard the news."

She handed a long, official paper to Blake, who glanced at the contents. It was from the Board of Trade office "re the Argosy Patent, taken out by Andrew Craig, of Stretton Street, Liverpool—said patent being for an invention by mechanical means of preventing——" and so forth and so on through a maze of technicalities, ending up with an acknowledgement of the receipt of the working model, which had been duly registered and accepted as highly satisfactory in every respect.

"I think," said Miss Ford, "that that must have been the paper he referred to, and it came just twelve hours too late!"

Blake handed it back.

"What time did he leave here on the night of his death?"

"It was late—much later than usual. You see, it was his first night ashore, and he hadn't seen Lucy for over three weeks. It must have been nearly eleven. He said that he was going to the Red Lion to have a drink to celebrate his return, and must then get back on board, as he had arranged to sleep there for a night or two in place of the regular night watchman, who was ill. A message had come down from the office requesting him to do so."

"And what about his cousin Duncan?"

"Oh, Andy was very pleased about that. The moment the ship came alongside, word was passed for Duncan to transfer at once to the outgoing ship, the Gnome, as second engineer, which was to go down river on the night tide. Of course it meant doing him out of his spell ashore; but he got promotion from third to second much sooner than he expected, and naturally jumped at the chance."

Blake frowned.

"Very well, Miss Ford. It seems rather a queer case at present, but I promise you to do all that I can; and, for the present, good-bye."

"I do rely on you, Mr. Blake," she said earnestly; "and as to the expense and trouble——"

Blake smiled.

"My dear young lady, I make it one of my strictest rules never to accept a fee from one of your sex. I am taking this case up from a sense of duty, and I will go so far as to say that I believe you are right when you insist that there is something underlying it all; and, above all, don't mention tho existence of those papers to anyone."

Blake walked slowly away towards the more central part of the town, wrapt in deep thought. If the man had been murdered, and for the one ostensible reason, it was clear that his murderer was ignorant of the fact that he had already been in communication with the Patent Office. Yet he must have been watching his movements carefully, or he could not have killed him within a few hours of his landing.

Blake visited the central police-station, where he was well known, and obtained an order to view the body, and a plain-clothes' man was detailed to accompany him. The photograph of Andy Craig had impressed him as that of a thick-set, strong, resolute man, with an exceptionally intelligent face and rather heavily-lidded eyes—the eyes of a thinker—a bright, pleasant, open face, but with a certain latent grimness and tenacity in it. On the whole, he fancied Craig must have proved an ugly customer to tackle, unless taken unawares. Still, photographs are deceptive, and he wished to see the original.

The body was lying in the mortuary, and he scrutinised it carefully. Death had lent it an added dignity, and made the features even finer than he had thought. Across the left cheek—as reported in the papers—there was an ugly cut or deep scratch running from just below the cheekbone to the outer corner of the eye. The edges were clean cut and the flesh on the cheek-bone itself was bruised. At the back of the head, also on the left side on a level with the ear, was an ugly, contused wound, which had bled a certain amount. Over this Blake spent some time, examining it most carefully. Then he rose.

"Is the Hotspur still lying at the same berth?" he asked his companion.

"She is so, Mr. Blake," answered the man, with an unmistakable brogue.

"Let's go and have a look at her, then. But it's a raw, damp night, and I dare say a glass of something hot at the Red Lion might not come amiss first—eh?"

The gentleman with the brogue brightened up visibly.

"It would not, sorr," he replied, with emphasis.

They had their refreshment, and Blake learned incidentally, from the barmaid who had volunteered her evidence, the exact spot where she had last seen Craig alive.

It was the third lamp-post on the right from the Red Lion door—that is to say, in the direction in which the Hotspur was lying. The man with him had certainly not entered the bar, or she would have noticed him; therefore he must have watched Craig enter and waited for him, since it was hardly probable that a man in a valuable fur coat would be loitering about the docks by chance, so late.

Blake and his companion sauntered along to the point indicated.

"Now," said the former, "let's make off for the Hotspur."

"We shall, sorr; an' a nasty, twisty, awkward koind av a way, it is, wid all this lumber about."

They wandered across ill-lit wharves piled with stacks of timber—gas buoys, waiting their spring coat of paint—light railroads, and a thousand other obstacles—to say nothing of wire and rope hawsers, made fast to bollards here and there, which threatened to trip them every other minute.

"An' now, here we are, Misther Blake," said his guide at length, pointing to a dim shape looming up before them—the rust-streaked sides of a big cargo boat, with a gangway thrust through a break in her well-deck just abreast of the forehold.

Blake peered at her weather-beaten sides through the dank river mist. She did not look at all inviting, nor did her surroundings.

He leant over and glanced down at the swirling yellow waters, twenty feet below the quayside. A man falling in there on a cold winter's night would need all his wits about him, however strong a swimmer he might be, to work his way out alive.

"Were any papers or anything found in the dead man's cabin?" he asked. "I suppose his effects were overhauled?"

"They were that! But barrin' a book or two full av diagrams an' a picture-postcard or so maybe, there was nothing at all but clothes and gear."

Blake nodded.

"Which are the steps where the body was found?"

"'Tis further along, you're meaning. 'Twas like this. Poor fellow, he must have lost his bearings in the fog—terrible bad, it was—an' overshot his mark by some four hundred yards before he discovered anything was wrong, and then headed down for the river, which bends outward a trifle just there—nosin' about for his boat.

"As luck would have it, there was another big steamer moored just above where he was picked up. but with only a single plank 'twixt her and the wharf, instead of a gangway. Not noticing this in the dark, he must have trod on it careless, as you might say, lost his footing, and gone in striking the head of him against an iron mooring-ring as he fell. That would be about twelve o'clock, or maybe a little later. 'Twas boatman Latimer found him, shortly after four, floating face downwards in a bit av an eddy—just there at the foot av these very stairs we're standing on."

"Quite so," said Blake. "Thank you. Now, as it's getting on, I must hurry off to the hotel. Perhaps you would join me in an appetiser?"

"I'd not be saying no, Mr. Blake."

BLAKE was astir early the next morning, but even before he rose he had been quite a long time consulting a tide-table.

He spent many hours that day loafing about the docks in an old ulster, talking to the idlers and the longshoremen.

In the evening he had two surprises, one of which caused him intense annoyance, and that was an announcement in the local papers—the morning edition, which he had not seen previously.

The ubiquitous and energetic Liverpudlian reporter had found him out; and one, with more zeal than discretion, was responsible for a flaring headline:

SEXTON BLAKE IN LIVERPOOL!

THE CRAIG MYSTERY!

As a matter of fact, the announcement was the outcome of sheer guesswork. The reporter, chancing to see him in the hall of his hotel, had recognised him, and, as chance would have it, he was the same man who had first elicited the barmaid's evidence about the individual in the fur coat. Being a shrewd, keen youngster, with an inherent dislike of the obvious, and a natural dislike of anything which explained away a situation or a drama by the vivid portrayal of which he earned his livelihood, he jumped at his opportunity and his conclusion, and for once jumped in the right direction.

That was Blake's cause of annoyance. The outcome was frankly a surprise. He had barely sat down to a very late dinner, than a visitor was announced—a gentleman who sent up a card bearing the inscription. "John Stephens & Co., Engineers, Manchester," and marked "Urgent."

Blake turned it over suspiciously. He frankly hated reporters and publicity, and feared a ruse of some kind, having considerable knowledge of their methods.

He handed the card back to the waiter, with a request that the visitor would state his business more explicitly.

In three minutes the card was beside him again, this time in a carefully sealed envelope. On the back of it was written:

Craig. I worked for him on Argosy matter. Office broken open yesterday lunch hour; two mishaps on way here. Very urgent.

Blake pursed his lips.

"Show the gentleman up!" he ordered. "Lay another plate here."

Mr. Stephens proved himself to be a young man, heavily built, with keen, deep-set black eyes, strong, regular teeth, and a big jaw—a rugged, extremely powerful specimen, who, for all that he called himself a consulting engineer, had clearly proved his worth in the shops, and had a thorough training and was no mere theorist. He carried one arm unobtrusively in an improvised sling, and seemed to be in some pain.

Blake eyed him all the way from the door down the long, brilliantly-lit dining-hall. By the time the man had reached the table he had summed him up and taken an instinctive liking to him—also he had an instinctive feeling that there were going to be new developments.

"Good evening," said Stephens abruptly. "I saw you were here by the papers. I know your reputation, and came right on by the next train. Mr. Blake, I'm accustomed to straight talk when I know the man I'm talking to. I take it you're here on the Craig business. If so, I'11 give you one point—Craig was murdered. This is the second—he was murdered because of a certain patent of his invention, of which I had knowledge, and in which there was the making of a big fortune. Now do you want to listen to any more or not?"

"My friend will dine with me here," said Blake, beckoning a waiter near by. "Bring the coffee to my room."

"I thought you would take it that way," said Mr. Stephens. "Many thanks for your hospitality. I am deuced hungry, and my arm's pretty well broken—we'll go into details afterwards.

"Now," he continued, as they sipped their coffee in Blake's own room, "Andy Craig was a pal of mine; and though he was only working as second on a second-class liner, a finer man at his job never stepped. He and his cousin Duncan had invented a thing which would have made them millionaires in a year or two. I don't know whether you understand technicalities yourself, Mr. Blake, but when a ship's propeller is run up to what we call the 'limit' and a bit beyond, that propeller is apt to 'bell'—in other words, it creates a practical vacuum round itself and gets no grip on the water. The same thing applies to these new-fangled aeroplanes and dirigibles. I don't want to bore you with 'shop' talk, but in plain English it means that a screw driven a fraction beyond the limit speed of revolutions is about as much use as a punt pole, and rather less—you can't shove ahead, you're burning a lot of fuel to no purpose, and your only alternative is to slow down. Craig has perfected an invention which entirely eliminates 'belling,' and there was a fortune waiting for him. I know for a fact that on his return trip he had been offered a very large sum by a big firm, so soon as he could get his patents passed and in order.

"He was a very quiet sort of chap, and very reticent. I and his cousin Duncan were, I believe, the only two people in his full confidence. This much, at any rate, I know for certain—there were only three specifications of his scheme in existence—one he carried on him, one till yesterday midday was in my office safe; and the other, to the best of my belief, was left with a Miss Ford of this town; and he intended to send it, with full particulars, to the patent office as soon as he returned.

"He was murdered two nights ago, and, so far, as I can read, the papers which I know he carried are missing—at the least, there is no mention of them. The second set were in my office when I locked up last night; the safe was broken open whilst I was at lunch to-day—when I returned, though everything else was intact, they were missing. On my way here I was attacked twice—once by three roughs outside my office doors as I started—they did the usual clumsy jostling act; but I am used to scrapping, and a certain amount of rough-and-tumble fighting. I jabbed one man in the teeth with my walking-stick and tripped another; the third bolted.

"Coming away from the train I was tackled again. I admit I was unprepared. A heavy, loaded cane nearly snapped my arm and the beggar who did the job—there was only one this time—made a grab at my inside pocket. He only got a few bills and invoices for his pains, and I, as you see, a damaged fin.

"But the meaning of it all is this. They think I hold the only remaining draught of the plans. Two they have got already, but the third—— Well, if they hear of Miss Ford they'll know where to look for it, and they won't stick at trifles. That's why I came along in a hurry."

Blake nodded.

"I know where the third copy is—in the Patent Office. Craig must have posted them off before he started on his outward voyage; so his death and your burglary were just so much wasted effort."

Stephens whistled softly.

"What a sell! Good heavens, what a sell!"

"Ah, but they don't know. What about Miss Ford's risk?" said Blake curtly. "Have you twelve hours to spare?"

"Four times that for poor old Andy's sake, if need be," said Stephens.

"Then take this card of mine and go down there at once. Ring me up if anything happens. One moment, you are a bit knocked about, take this in case of accidents." And he slipped a revolver across to him. "You had better cab it down. You know the address—Stretton Street."

Stephens nodded, and vanished with a hasty "Good-night."

Blake also went out shortly afterwards, but not in the direction of Stretton Street.

For the next few days Blake was very busy about the business centres of the city—apparently doing nothing in particular, in reality moving heaven and earth to come across a trace of the man in the fur coat who had been seen last with Craig; also there was one office in particular which he kept a special watch on.

Stephens, of his own accord, insisted on keeping guard over the Misses Ford, and Blake was content that he should do so—though up to now there had been no indication that the murderer or murderers knew anything of the friendship between the girls and the dead man.

So matters drifted along quietly till the Gnome, the fastest boat of the Greener line, came back from New York and slid up the Mersey to her appointed berth. Then there was a fresh and startling development. Duncan, the second engineer, was missing. He had been found dead in a Bowery slum with his head smashed by a sandbag. He had been on shore leave, the captain explained, and whether the tragedy was the outcome of a drunken spree, or whether it had merely been done from motives of robbery, no one could tell. None of his shipmates had been with him at the time. The police had found him at dawn, his head battered and his pockets rifled. The rest was a mystery.

The public, and even the Press, paid little heed to the thing. Their minds failed to connect the murder of an engineer in America with an accident in a Liverpool dock. But then, they did not know that Duncan and Craig were cousins and partners.

Blake's eyes gleamed when he heard the news and his mouth became set and hard. He began to see his goal within reach.

That night, late, armed with a plug of strong tobacco and a capacious flask, he made his way down to the Gnome, lying at her moorings.

The ship-keeper stood in the shelter of the galley, leaning against the rail—and, as luck would have it, sucking meditatively at an empty pipe.

It was two hours later when he left the ship, and the caretaker, convinced that he had never met a more civil-spoken, free-handed, ignorant thing on two legs in his life, had absorbed the contents of the flask—and Blake had absorbed such wits as the old man was possessed of, and a complete knowledge of the ship's interior. He had also learnt that the cargo was to be hustled into her the moment her holds were empty, and that she was to sail on the fourteenth, outward bound again.

Messrs. Morsom and Gold, the owners of the Greener line, were clearly gluttons for work.

On the twelfth, just before the luncheon hour, Mr. Gold, the younger partner of the firm, received a visitor—his card bore the name of J. Hiram Muntz, and down below, "Engineers and Contractors," in small type.

The firm of Muntz was well known for its sound financial basis, and its liking for novelties.

Mr. Gold—a tall, rather oily-looking man, a little too smartly dressed and a little too obviously opulent—smiled to himself as he read the card, twitched his tie straight in the glass over the mantelpiece of the palatially-furnished office, and turned back again sharply.

"Show Mr. Muntz up at once," he said, and smiled again as the door closed behind the clerk—Fate seemed to be playing into his hands.

Mr. Muntz came bustling in, a cheery, portly American with a strong taint of German in him.

He wore a big fur coat, a soft slouch hat, round, gold-rimmed spectacles and side-whiskers, neatly trimmed; a muffler was tucked carelessly round his throat, and he was smoking a huge cigar, which was certainly pure German in origin—so pure that Mr. Gold hastily lit a cigarette in self-defence.

"Say, Mr. Gold," began Mr. Muntz, dropping into an armchair with a wheeze and a grunt. "I haven't the pleasure of your acquaintance, but I'm over this side rousing up business, and I thought your firm and mine ought to kind of hitch up closer. 'The Greener boats are a smart line,' I said to myself; but that's no reason why they shouldn't be all the better for some of our new notions. We've just brought out a new condenser, now, which I'd like you to glance over the details of, and we've also got something that's a cinch in low-pressure cylinders. I'm not one of those men who like to see other firms getting business whilst our men sit down and play checkers—no, sir. So being right here, I thought I'd smell around this office and have a bit of a chat over things."

Mr. Gold was all smiles and affability. Muntz & Co. were a firm to be treated with respect. He followed his fat visitor through a maze of diagrams, statistics, and explanations, with a show of deep interest.

At length he said:

"I shall be most happy to place your suggestions before Mr. Morsom, the senior partner; he generally attends to that side of the business. I myself see to matters of cargo and shipments. By the way, though, that reminds me. I have something in your line. I have gone into it a little, and I must say it seems to me so good that we are thinking of taking up a half share in it ourselves, though it's out of our ordinary course of business. It is an invention of one of our men—a very clever invention for abolishing the belling of propellers.

"He fell on hard times, so I bought the idea from him right out, and we proposed to float it as a small company, and sell a half interest in the parent syndicate for, say, forty thousand. It's a small affair, you see, but, properly handled, there's a fortune in it. Now, your firm are just the people to put the matter through. Just glance at these papers and see what you think of the idea."

Mr. Muntz adjusted his glasses, and peered at them short-sightedly.

Suddenly he sprang to his feet.

"Gee-whiz!" he exclaimed excitedly. "Ach! Mr. Gold, I've been had for a sucker, sure! Do you see these—these specifications of yours? Well, dang me, if I ain't been and paid out hard dollars for just that very same thing! Your man on hard times has been playing honeypots with the pair of us!"

Mr. Gold's face turned grey.

"What do you mean?" he asked sharply.

"What do I mean? Waal, I guess that's plain enough when I tell you that I bought this invention some time back with money out of my own pocket, and that I have a copy of the Board of Trade's certificate, or whatever you call it this side, right here in my pocket."

He slammed a paper down on the desk right under Mr. Gold's nose. The latter seized it with beringed, trembling fingers. It was characteristic of his love of display that, not content with a couple of rings on his left hand, he also wore a large single diamond on the middle finger of his right.

"Good heavens!" he stammered. "But this is very serious, Mr. Muntz."

"Serious!" bellowed the other. "See here. You come out to lunch with me right away, and we'll discuss."

Mr. Gold rose from his seat in a dazed way, and made a violent effort to conceal his discomfiture.

"I—er—thanks, yes! Perhaps that will be best."

"You come on right away. Say, now I come to think of it, things are panning out just right. I've another friend of mine coming along—a real, smart live man—Blake—Sexton Blake, the crime elucidator; happened up against him in the hotel yesterday. He's the man to put his finger on this. Here, hold up, man! What's the matter?"

Mr. Gold swayed and nearly fell.

"I—it's nothing! A slight heart-attack, I think. I've been rather overworked lately. I don't think I'll come out, thanks! I'll just sit quietly for a bit, if you'll excuse me, Mr. Muntz!"

The big man nodded sympathetically, and replaced the paper in his pocket.

"I guess you need a livener—something stiff and fizzy. Well, I must be off. See you later!—or ring me up on the 'phone."

As he passed out he gave a swift glance back. Mr. Gold was sitting with his head buried in his hands, and a face the colour of dirty grey putty.

At two o'clock that same day Stephens received a wire, which brought him to the docks in a hurry, where he met Blake by appointment in a dingy little bar of a small, old-fashioned public-house.

"Well," he asked hurriedly, "what luck?"

Blake smiled. He was evidently in good spirits, and well-satisfied with himself.

"The best," he said. "I've found our man. I was fairly sure of him from the first. By the way, look there."

And he pointed over the dingy window screen.

On the far side of the quay lay the Gnome, the centre of a very inferno of bustle and confusion, men working like demons at her derricks, and the shore cranes piling the cargo into her for all they were worth.

"Great Scott!" cried Stephens, after a moment or two, "Why, she's got steam up, or at any rate, she is getting it as quick as she can. I thought you said she wasn't due to sail until the fourteenth."

"I expect her schedule's been altered," said Blake grimly. "Anyhow, a man from headquarters came rushing down here in a cab an hour ago, rousted Captain Rand—that's her skipper—out from his dinner, and gave him orders that sent him flying off as if he'd got a flea in his ear."

Stephens looked at him inquiringly.

"What are you driving at?"

"I've an idea," replied Blake drily, "that the Gnome will sail on the night tide, even at the risk of leaving a third of her cargo on the quayside."

"What on earth for? And why are we here?"

"We're here to take a little trip down river on her, but as we're uninvited we'll not go on board till the last moment."

The dusk settled down quickly, and a heavy drizzle set in, accompanied by a high wind.

Blake and Stephens ordered a meal of sorts, and the former kept a watchful eye on the Gnome whilst he ate.

"High water at nine-thirty," he said. "She'll warp out on the first of the ebb."

A little after nine a cab drew up in a side street near by with a clatter. They heard it turn and drive slowly off again: and, after a discreet interval, a tall man, carrying a small bag which seemed heavy, and wearing a cloth cap, well pulled down, and a long coat, with a fur-lined collar turned up about his ears, slipped hurriedly across the quay, keeping to the shadows as much as possible.

"The man in the fur coat, by James!" said Stephens.

"Precisely!" answered Blake. "That's another reason why we are here. I was expecting him. Ah, they're working the derricks on board now, and she has a full head of steam. We'd better be moving. We must watch our chance and jump for it just before she casts off. It's a hundred to one we sha'n't be noticed in the darkness, and with men coming and going all the time.

"Once on board, we must take what cover we can till she's well out in the stream and forging ahead."

Blake was right. No one paid the faintest attention to them. Stevedores were still coming and going. The deck hands were busy standing by warps or battening down the holds. The captain Was on the bridge with the pilot, and the mates busy here, there, and everywhere.

"This way!" whispered Blake.

And, side by side, they dived down into a dimly lit alley-way, and stood up in the deep shadows of the engine room.

Faintly they heard the shouts and bawling of orders.

"Slack away aft there! Slack away! Cast off that bow warp! Cast off!" Then a dull splash. "Leggo, all!" And the answering cry, "All gone, sir!"

"Come!" said Blake. "If anyone speaks to you or tries to stop you, just grunt an answer of some sort. They'll be far too busy to worry about details. Follow me close."

They stepped boldly on to the upper gratings of the engine-room. The electric-lights burnt dully on a quarter current, and the whole place was dim and misty with steam.

One man—a greaser—did turn and call out, "Hallo!"

But Blake merely nodded and shouted something to him in reply across the clanking din of the now moving engines, and passed on.

"Look out now!" he cried to Stephens. "We may come upon our man any time. Better let me go first, I'm armed, and he may show fight. We'll draw the most likely cover first—and that, I should say, is the shaft alley-way."

They dived again into the very bowels of the ship, and came at last to the entrance of the shaft-tunnel. A couple of naked incandescents, burning dully, formed all the light available.

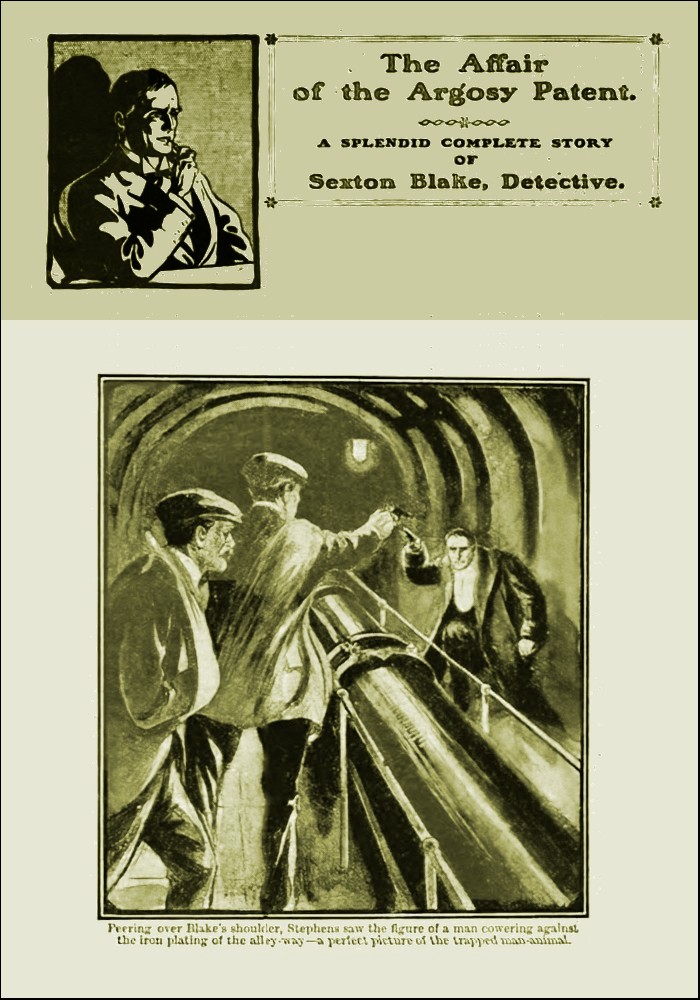

Suddenly Blake drew a sharp breath. His quick eye had caught the glimmer of something white in the far end of the tunnel right astern. Stooping low, they made their way towards it; and Stephens, peering over Blake's shoulder, saw the figure of a man cowering down against the iron plating of the alley-way.

His face was white and haggard and drawn. A crumpled white shirt-front showed where his fur coat had been thrown partially open, and in his hand he held an ugly-looking revolver—a perfect picture of the trapped man-animal. Blake's hand flew to his pocket.

"Game's up, Gold!" he said, in a hard voice. "Put that thing away! I've a warrant in my pocket for your arrest for the murder of Andrew Craig."

There was a hoarse cry, and the reverberating crack of a revolver in a confined space, instantly answered by another, and a yelp of pain.

"I warned you," said Blake sternly, and lowered his pistol hand.

Gold's bullet had flicked the paint off the iron plating a foot too much to the right, but Blake's had shattered the man's right shoulder.

In an instant they had secured him. Pain prevented him doing more than struggle feebly. Blake picked up the bag which lay on the floor behind him. It was very heavy, and chinked dully.

"Loot!" he said tersely. "Bring him along, Stephens—you can manage him all right with one hand. Now I must look after the other beauty."

He stepped out on deck and ran swiftly up the bridge ladder. The pilot was peering through the darkness ahead; the captain stood beside him; the quartermaster remained impassive, his eyes glued to the pinnacle.

The captain and the pilot both turned sharply.

"What the dickens! Who are you, sir? Get off my bridge at once," roared the captain. "What are you doing aboard this vessel? By James, I'll take my boot to you pretty smart if——"

"That will do, Captain Rand," said Blake drily. "You can keep all that to explain away the murder of second engineer Duncan in New York on the last voyage."

The captain hunched his shoulders, and the blood ran out of his face beneath the tan, leaving it livid.

"By James!" he blustered, and then with a hoarse, choking cry threw up his hands, and came crashing down on to the deck.

The pilot looked at him, then at Blake. He was a wise man who did not interfere in matters outside his own concerns.

"A point to starboard," he called over his shoulder.

"Starboard it is, sir," said the quartermaster, and shuddered. The captain's face was not a pretty sight.

Later, when the pilot boat came alongside, two men were lowered into her in handcuffs. After an interval the pilot, Blake, and Stephens came down the accommodation ladder, and the first mate, left in charge, was ordered to anchor just clear of the fairway and wait instructions.

"You may be right, sir," said the pilot, as he and Blake and Stephens sat round the table, and the tug slid back Liverpoolwards; "but I'm hanged if I understand it all. Morsom & Gold have always been considered a sound firm, and Rand, I understood, had a small interest in the business."

"Exactly so," said Blake, "but things aren't always what they seem. Morsom & Gold have been financially rotten for two years and more—a crash was inevitable. They knew it, and Rand knew it, and they were desperate.

"Then Andrew Craig came to them with his half-completed patent. They could see there was a fortune in it—a fortune big enough to prop up the business again, and they tried to Jew him out of it; but Craig was too cute for them and made up his mind to deal elsewhere.

"They didn't know, of course, that he actually applied for his patent before he sailed on his last voyage, but they did know that only three copies of the plans were in existence, and also that Duncan was in with him.

"The moment I heard of the man with the fur coat, and Duncan's sudden promotion to an outgoing ship, I suspected mischief, when taken in connection with the fact that Craig was murdered within a few hours of his arrival ashore.

"Also, there was the rather unusual fact of Craig being told off as ship-keeper. I made out from this—first, that the men after the plans had a thorough knowledge of Craig's movements, and also that they exercised considerable power in the affairs of the Greener Line. The real position of Morsom & Gold seemed to me to want investigating.

"The moment I saw Craig's body I was positive that it was a case of deliberate murder.

"He was a man who, if on his guard, would have put up a stiff fight; therefore, to make sure, he had to be taken unawares; he was wearing a bowler on the night in question.

"Now a bowler can deflect a good hard blow, especially if the blow glances off the rim, and on a dark night it is difficult to make certain.

"It was clear to me that his murderer—presumably the man in the fur coat—having failed in his negotiations—Craig was seen to repeatedly shake his head, you remember—followed him up as he returned to his ship and struck him a back-handed blow with a loaded stick from behind; the contused wound showed this, from its position; and, if you come to think of it, it is the only way in which the blow could have been struck, so as to make sure of avoiding the hat by striking beneath it. Also, it was the most dangerous spot exposed—just behind the ear.

"Craig probably reeled and tried to turn and face his assailant, whereupon the latter struck him savagely in the face and sent him down with a crash, which finished him.

"In so doing, Craig's face was badly cut by something sharp; it was a right-handed blow, judging from the bruise and direction, and the cut must have been made by a ring. Few men wear rings on the right hand—Mr. Gold wears a large single diamond on the middle finger.

"The police theory that Craig had missed his way, overshot the mark, and fallen, was absurd. Any man who could find his way through all the litter and lumber on the quay on such a night, could certainly have found his ship.

"Also, had he really fallen over the quay, where they made out, his body would not have been found there at all, but three or four hundred yards higher up, for the tide was making at the time, and was still making when the waterman found his body.

"I tried an experiment with a few baulks of wood later, and found, that if flung off the quayside close to the Hotspur's berth, the probable scene of the murder, the making tide swept them all up to approximately where the body was found in about the same time.

"By now I was pretty sure that my man was a tall, powerful individual with, for preference, a ring on his right hand, and connected with Morsom & Gold. Gold himself filled the bill precisely. Still I could not be sure. Moreover, I was pretty certain that the captain of the Gnome was mixed up in the business to a greater or less extent.

"When the Gnome returned with the report of Duncan's death, I was sure. I paid a surreptitious visit to the Gnome one night, and had a chat with the watchman, whom I induced to take me over the ship.

"I managed to get rid of him whilst I had a peep at the captain's cabin, and there, sure enough, in a flimsy locked cash box under a pile of other things, I found the second set of papers. And on the top of this, I had the assistance of my friend Mr. Stephens here, whose office had been burgled for the sake of the third set—which was not there.

"The next step was to lure Gold into making a false move. I knew he was very hard pressed for money, and I laid a trap for him.

"I happen to know Muntz & Co., the big contractors, and to know that Mr. Muntz himself was a stranger to Gold.

"I impersonated Muntz and called at the office. I would have bet ten to one that Gold would jump at such a chance to get a price for the invention. He did—as eagerly as a terrier at a rat.

"Then I sprang a mine on him, by pretending that I, as Muntz, had already bought the same thing. That bowled him over; he saw he had made a mess of things somewhere. I backed it up by an invitation to meet myself at luncheon, and he was scared to death. He must have overlooked a report in the papers that I had taken the case up.

"I could see by the man's face when I left him that he meant to grab everything he could lay hands on, and bolt; and Captain Rand, his confederate, and the Gnome, gave him his best chance.

"He rushed down a messenger to tell Rand to advance the date of sailing by forty-eight hours at any cost, and sneaked on board just in the nick of time, having probably left word that he was dining out somewhere. The rest you know. It was only a matter of spotting the most easily available temporary hiding-place, for with you on the bridge, and liable at any moment to look into the cabin for something, he would be sure to avoid that.

"And now, Stephens, I see the town lights closing up, and I think that, in spite of the lateness of the hour, I'll just telephone the police to look after Morsom, and then run down and see Miss Ford with the news."

"I'll come, too," said Stephens eagerly.

Blake smiled under cover of the darkness.

"She is a most uncommonly pretty girl," he said drily. "Prettier than her sister Lucy, I should say."

Of course she is," said Stephens indignantly, and then relapsed into sudden silence, and pulled himself up short.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.