RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

BLAKE had been suffering from over-strain and a bad attack of insomnia. So, constituting himself his own physician, he prescribed for himself that simplest and best of all cures—fresh air and exercise.

He dined leisurely at seven in a small Essex village inn, and, after dining, fine or rain, cold or warm, he went regularly for a good fifteen-mile tramp in the dark.

It wasn't particularly amusing, but it did him a vast amount of good. He came back pleasantly tired—too tired to lie awake and worry over this and that—and slept the sleep of the just, though it is on record that the unjust occasionally doze without any particular discomfort.

He had been at Helsing just a week, and was contemplating leaving in a couple of days, when he literally walked into the affairs of the Black Orchid. He was swinging along at a good round four-and-a-half to the hour, a well-coloured clay—an old friend—between his teeth, and a serviceable ash stick in the crook of his arm, homeward bound, when he suddenly came upon several lights and a group of men bending over something in the road not a hundred yards away.

He had a good knowledge of the district, gained by his nocturnal tramps, and he knew that the nearest cottage was at least a quarter of a mile away, round a bend in the road, and out of sight.

The road itself led to Helsing a mile further on; just where Blake came in sight of the group it forked. The main road led to Helsing Station; the other, a by-road up which he had been travelling, to a small hamlet known as Helsing Ford. The two joined one another at an acute angle, with the apex pointing towards Helsing.

It was a particularly desolate stretch of country, with dense cover on either side of the road, and had rather an evil reputation for gipsies and other vagrants.

The group was collected at a point about seventy yards beyond the junction of the two roads. Blake, seeing at once that something was amiss, hurried forward until he joined them. There were six in all, and two from the nearest cottages had storm lanterns; in their midst lay the body of an elderly man, quite dead, with his head horribly battered in.

He was lying a little to one side of the road, and his clothes showed that he had been rolled over and over in the dirt; no other injuries were apparent. The sickly, uncertain flare of the lanterns made it seem as though he were still twitching convulsively in his death struggle, but a touch of his leg, which was drawn up in a cramped position, assured Blake that he had been dead for some time. The yokels who had found him were dumbfounded, and sorely in need of a guiding mind.

"Bill 'e be gone for perlice!" said one, glancing round, for they all knew Blake by sight. "Wot be best to do, mister?"

Blake glanced at the body. It was that of a man past middle age, with long, old-fashioned grey whiskers, a clean-shaven chin, and dressed in what should have been immaculate broadcloth. He had been wearing glasses, for they lay broken and splintered a yard or so away, and the back of the head was a hideous sight.

"Why, it's old Mr. Smithers from the farm!" said Blake, bending down.

"Ay, sir, it be poor Mr. Smithers, an' a kinder-'earted gent never lived! It be they blamed gipsies what have outed him—cracked 'is 'ead they 'ave, an' 'im used to come by this ways reg'lar as clockwork every night by the ten o'clock train; an' Fridays 'e 'ad 'is bit of a bag with 'is takings, to bank Saturdays!"

Mr. Smithers, of the Farm, was the sleeping partner in a successful small draper's shop in the neighbouring market town. His nephew ostensibly conducted the business, but Mr. Smithers kept a watchful eye on it and went backwards and forwards from Helsing as regularly as clockwork every day, more from habit than necessity, for he had made enough to retire on in a modest way.

His one passion in life, however, was his flowers, and, above all, his small orchid-house, where he spent all his mornings. A more harmless, inoffensive individual it would be hard to conceive, methodical and regular to such a degree that you could have set your watch by his movements.

The Farm, as it was called, lay on the outskirts of Helsing.

Blake glanced at his watch. It was close on half-past eleven, and a Friday night.

"Have any of you seen anything of the bag you say he was in the habit of carrying on this day of the week?" he asked.

"No, sir," came in chorus from three or four voices at once. "'Is bag he took for sure, a black 'un 'e were, small, like so—us knowed 'un well by sight—an' it be took. Folks allus said as one day Mr. Smithers would be done for wi' carryin' a lump of money along this 'ere road after dark. 'Tis a main bad place for tramps an' gipsies an' such. Oi see'd two o' their travellin' vans pass this way this mornin'."

Blake nodded.

"They're camping down the lane three or four miles back; I passed them not long ago. Now, will one of you lend me a lantern? Thanks. Now, I want you all to come to the side of the road, here and wait patiently till I've made a careful examination."

The men obeyed willingly enough, only too glad to find someone on to whom they could shift the responsibility.

Blake knelt down and set the lantern on the ground. The wound at the back of the head was clearly the result of a terrific blow, dealt with such savage force that it had caved in the base of the skull like an egg-shell, and death must have been instantaneous. Yet, in spite of that, the body had certainly been moved after death, not lifted and carried, but flung aside, as it were, and rolled over and over, for both the upper as well as the underside of the clothes were covered with dust and road dirt.

The nature of the wound, too, made it hard to determine at a glance what type of weapon had been used. The general appearances suggested some homicidal maniac, of gigantic stature and a wild-beast-like ferocity, armed with a hastily-improvised club torn from some post and rails, who had dashed upon his unsuspecting victim with the velocity of a whirlwind.

Blake remembered hearing that Mr. Smithers was very deaf—a fact which rather lent colour to the theory. On the other hand, however, a homicidal maniac rarely if ever waits to rob his victim. His desire is for blood, to crush and mangle and batter his prey with savage glee. Wealth or money or glittering jewels have no interest for him.

The bag containing the money was certainly missing, and, moreover, the dead man's watch and chain had been snatched, as one remaining broken link and the crossbar in the buttonhole testified, though there were still loose coins, to the value of a couple of pounds, in his pocket, and his sleeve-links and a handsome scarfpin—a cat's eye, set in brilliants—were untouched.

Blake confessed to being momentarily puzzled. It was possible, of course, that the gipsies might have had a hand in the crime, but he hardly thought it likely.

"Give a dog a bad name" was a saying which, in his opinion, applied particularly to the gipsy folk. Whenever they happen to be in a district where a crime is committed it's a certainty that they will be suspected and possibly arrested.

As a matter of fact, as Blake knew from long personal experience, gipsies, though by no means angels, are not as black as they are painted. They have their good points. They never forget a kindness; they are merry and happy-go-lucky; and, above all, cold-blooded, deliberate murder for gain or spite is not a pastime they indulge in.

In the quick flash of a quarrel, or in revenge, human life is not a thing they put a long price on; but in this case there had been no fight or quarrel, and to associate the harmless and methodical Mr. Smithers with any scheme of revenge was, on the face of it, ridiculous.

Blake studied the road on either side, and his surroundings, as well as he was able to by the dim light of the storm lantern. On each hand for some considerable distance the roadside was densely wooded, and it would have been a simple matter for anyone to have lain in wait and made a sudden dash—especially anyone who knew that Mr. Smithers travelled regularly by the train arriving at ten, and was in the habit of carrying a considerable amount of gold with him on Friday nights.

He turned back to the body and studied its position more exactly. It was lying, as has been said, on its back, partially concealing the wound, bareheaded, the features contracted and distorted into a fixed expression of horror and dismay. One fist was tightly clenched, the fingers of the other hand were splayed, palm upwards. One leg, the left, was crooked at the knee, and the trouser leg was torn raggedly by violent contact with the road, and on the right underside of the body, at the height of the third rib, the coat had a jagged rip some three inches in length.

Blake examined this carefully. Owing to the position of the body relatively to his own it had escaped his notice previously.

Mr. Smithers was not a tall man, though fairly thick-set, and Blake asked himself what could have caused that tear. He felt instinctively that if he could get at that he was half way to the elucidation of the crime.

Suddenly a new idea struck him—the whereabouts of the dead man's hat might help him. Calling to the whispering group of men, he ordered them to stay where they were, and on no account to disturb the roadway by tramping about on it. Then taking the lantern he moved forward a few paces along the edge of the wayside, holding the light low; but the hat was nowhere to be seen.

He stood for a moment frowning thoughtfully, then retraced his steps and continued on past the body for some distance. Again there was no sign of the hat.

He came back again, this time paying more attention to the rough strip of grass at the side of the road; and, sure enough, he found the hat, but nearly ten yards from where the body lay. Moreover, it was battered into an almost unrecognisable mass by a violent blow on the top, which had completely smashed in the crown. Yet there was no wound on the top of Mr. Smithers' head.

The further he went into matters the more inexplicable and contradictory they seemed, and Blake went at them again with renewed interest. He had expected at first a rather sordid, ordinary kind of case, but now he was on his mettle.

Snatching the second lantern from the man who was carrying it, he took one in either hand and re-examined the roadway itself.

Before he had gone a dozen paces he stopped. He stooped, holding his lights close to the ground, and gave a sharp exclamation of satisfaction. Then he moved away quickly in the direction of the fork of the two roads, stooping every ten yards or so to study the ground.

Those watching him saw the two lamps grow dimmer and dimmer in the distance, check for an instant at the point of junction, and then hurry down the right-hand lane which led to Helsing Ford.

Here again the lights became stationary for quite an appreciable time, and then receded once more.

"'E be a rum 'un!" said one of the men, sucking at his empty pipe.

"Folk do say 'e be won'erful clever," answered another, "an' not afeared o' nuthin'. 'E bain't goin' to tackle them there gipsies single-'anded, surely?"

"They'd be after makin' mincemeat of 'im. We 'uns 'ad better go an' bear a hand."

"Not us! 'Ere 'e be comin' again, runnin' like a mad thing."

Blake was coming back along the road at top speed, the lanterns swinging and clattering behind him, keeping carefully, however, to the edge of the grass. He passed the group opposite the body, taking no heed of them, and went further up the road, stopping and peering here and there.

Twenty yards beyond where Mr. Smithers lay, he gave a quick short cry of satisfaction, and went down once more on hands and knees, his face close to the road surface, his eyes bright and gleaming, and his whole figure tense and nervous and alert.

He was evidently spelling out the details of the crime word by word.

After a few moments he rose, brushed his knees, and came back towards them, this time on a rather zigzag straight to where the body lay limp and inert, his face bent towards the ground end his feet moving gingerly as though he were loth to disturb something.

When he was right up to them he turned and asked sharply:

"Any of you men got a bicycle you can lend me?"

One of the group dived back towards the hedge and brought forward a ramshackle old solid-tyred affair which he used to take him to his work.

"Right you are!" said Blake. "Here's five bob for the use of it for to-night. If I'm not back when you start for work to-morrow I'll give you another five. Hand me one of those lamps, someone. That's capital. I'm off; good-night!"

And the next second ho was pelting along the road towards Helsing village, and was soon lost to sight beyond the curve.

"Funny bloke," said the owner of the bicycle. "'Ope he don't come back for a fortnight at that rate o' pay. 'Allo, 'ere come the perlice at last!"

Far away down the road he had heard and recognised the heavy, majestic official tread of the local representatives of the law.

BLAKE, lantern in hand, had disappeared on his borrowed bicycle, and it was well past midday before any of the good folk of Helsing set eyes on him again.

He was muddied from head to foot, and soaked to the skin, for it had rained heavily just before the dawn, and he had been riding all through the night off and on. Moreover, he was desperately hungry and very tired.

He had a wash and a change of clothes, and was just sitting down to a big dish of ham and eggs, when the local police inspector was ushered in. He was rubbing his hands and smiling.

"Morning, Mr. Blake," he said, with a touch of condescension in his voice. "I'm glad you were in these parts just as this happened. Of course, we've all heard of you, and some of the smart things you've done; but this time I hope you will be able to give a good account of us to the big-wigs up at the Yard. We've got our men all right, and I think you'll admit it was a pretty neat piece of work, sir. Thanks to that hint from you, we knew which route the gipsies had taken, and followed them up at once.

"They'd taken the alarm, though, and cleared out sharp. We have a lot of their sort round here, however, and several of our men can read gipsy signs—the bits of sticks and things they leave about to let their pals know which way they've gone. Sure enough, just past Helsing Ford they'd turned away north, and we found the crossed twigs.

"They must have been going fast, too, for we had a ten-mile chase before we caught them up. Two of the men are old hands—notorious poachers—and we spotted them at once.

"They tried the usual bluff innocence racket, but I could see with half an eye that they were in a blue funk, and I overhauled the vans. In the second, stowed away amongst some old clothes, though, I found Mr. Smithers' watch and the broken chain. So that put an end to their game. One of the men swore he'd found it in a wood near by; but it was too thin, of course, so we just brought 'em both along to the lock-up, and a mounted patrol is keeping an eye on the rest of the gang."

"You found one of them in possession of Smithers' watch," said Blake slowly, frowning to himself. "Have you the watch with you, and can I see it for a moment?"

"Certainly; here you are, sir. I brought it along, as I'm on my way to see Mr. Harbord, the magistrate, about the case."

He fumbled in his pocket, and eventually produced the watch and laid it beside Blake's plate. It was a plain, gold, half-hunter; the glass was cracked, and the case was dented on one side, clearly from a heavy blow. Attached to it was a length of gold chain, snapped at the bar end, and on the back of the case, in small black letters, were the initials "J E.S."

Blake looked at it minutely before handing it back.

"That is certainly Smithers' watch," he said. "I recognise it by the fracture of the chain. This twisted link here corresponds exactly with the link still in the waistcoat. Where exactly did the man say he picked it up?"

"In a little bit of a copse on the left of the road, just this side of Helsing; but, of course, that was a bit too much of a good thing, for not only does the copse lie beyond Mr. Smithers' house, but the poor fellow himself was struck down half a mile short of the place."

"Quite so," said Blake. "Are you going straight out to Mr—er—Harbord's now?"

"Well, it's a goodish step from here, so I was going to put it off till after dinner, and then drive out. You are very welcome to come, too, if you like, sir."

"Thanks," said Blake. "I should like it immensely. Meanwhile, I suppose there's no objection to my having a look over the dead man's house, just to fill in time?"

"Not in the least, Mr. Blake. One of our men is there, but just mention my name and he'll let you in. I'll be back here for you at a quarter-past two with the trap."

Blake finished his breakfast and strolled down the road to the farm where Mr. Smithers had lived, and found no difficulty in obtaining entrance. His only real difficulty was in evading the conversation of the well-meaning but rather talkative policeman in charge.

He went the rounds of the house, and then turned his attention to the garden at the back. In size it was small, and a considerable portion of it was covered with glass. A glance sufficed to show that Mr. Smithers had been a keen and experienced horticulturist, and had spared no expense on his hobby. Two of the houses were filled entirely with orchids, and the doors were fitted with patent lever-locks, showing that these were the special pride of Mr. Smithers' heart, and that he guarded them with jealous care.

Blake obtained the keys and went in. Mr. Smithers had clearly been one of those men who gamble in orchids, buying job lots here and there at the sales for a few pounds, in the hope of one day rearing a "Sport," and making a small fortune out of it.

Before Blake had been in the second house a couple of minutes he discovered that Mr. Smithers had for once, at any rate, been gambling to some purpose. Carefully tucked away in a shielded corner, where the casual observer might have overlooked it, was a perfectly jet-black orchid, an absolutely unique specimen both for colour and the magnificent size of the bloom.

Blake looked at it with a strange light in his eyes, for he knew that he was looking at the immediate cause of Mr. Smithers' murder.

Then he locked the door again, and went quietly out; but he had retained the keys.

An hour later he was seated beside the inspector, driving out to Mr. Harbord, the magistrate. Mr. Harbord lived in a spacious white house, standing in pleasant grounds, with well-kept, orderly gardens and terraces. The inspector swept round the back way, which led to the stables, to put up the trap, as he expected to be detained for some little time. And Blake lit a- cigarette and strolled about, talking to the groom and looking over the place with an abstracted air.

"I suppose it won't be many years before horses finally vanish off the road, except as curiosities," he said at last.

"I believe you're about right, sir," answered the groom. "Everyone seems crazy over these new-fangled stink-cars, as I call 'em. We're luckier here than most parts, though; we don't get many of 'em, because the roads aren't up to much. The guv'nor's got one, and two or three more of the gentry round about. But it's nothing like Surrey or places near town."

"I suppose you have had to turn to and learn how to drive them?"

"Not me, thank goodness! I 'ave to clean 'er and oil up and that, but the guv'nor always drives himself, good luck to it. I can't stick the things; cleaning them's bad enough. Look at this, for instance"—opening the coach-house door. "Mr. Harbord drove up to town yesterday, and it took me two solid hours this morning to get the mud and grease off."

Blake glanced at the car—a powerful forty-horse, with two bucket seats—and nodded.

"He ought to be able to get about pretty quickly in a thing that size, anyhow. Ready, inspector? Very well, I'll come with you." And, throwing away his cigarette, he strolled off towards the house.

Mr. Harbord was in his study—a dark, lean-faced man of about forty, with a drooping moustache hiding a rather unpleasant mouth, coarse features, and narrow-lidded dark eyes set too close together.

He was clearly by no means in the best of tempers, and appeared to have lunched rather well than wisely, for his face was flushed and his hands shook noticeably.

"Well, what is it you want?" he snapped. "And who is this gentleman?"

"I've come to see you about the Smithers murder case, sir. And this gentleman—Mr. Blake—came with me, as he was one of the first to find the body. I sent you a report of the crime this morning, sir, by one of our men on a bicycle."

Mr. Harbord nodded.

"I got your message. It seems a bad case, so I telephoned to Sir Arthur Moon to come over. He is here. One moment—I'll send and ask him to come in and hear what you have to say."

Sir Arthur, a fellow-magistrate, came in shortly—a typical country squire, with a bluff, hearty manner, and a kindly and rather shrewd face.

"Now then, inspector, Sir Arthur and I shall be glad to hear a few details," said Mr. Harbord sharply. "Be as brief as you can, as I wish to go to town by the afternoon train."

"Well, sir, I told you in my report of the finding of the body. And now we've got the men safe under lock and key right enough—a couple of gipsies. One of 'em had the dead man's watch hidden away in his van; but, so far, we've not been able to find the bag or the money."

"Those infernal gipsies are the curse of the country," said Sir Arthur. "They ruin the covers, poach, and thieve, and break down fences. If I had my way I'd pack the whole lot of 'em out of England. Have you got a clear case against them, inspector?"

"Clear as daylight, Sir Arthur; and we haven't wasted much time either. Mr. Blake here was able to put us on their track."

"Mr. Sexton Blake?" inquired Sir Arthur.

Blake bowed.

"I'm delighted to meet you," said Sir Arthur. "I've heard wonderful accounts of what you can do and have done. My cousin, Lady Blare, is never tired of singing your praises.

"Now, as regards this case. I suppose you agree that we've got the right men? We don't want to make any mistake, do we? But with you to back us there's not much fear of that."

"No; I don't think there's much fear of that," said Blake drily. "So perhaps, Sir Arthur, you would kindly sign a warrant and give it to the inspector here, and he can arrest the man straight away."

Sir Arthur stared, and the inspector gave a gulp of surprise.

"But surely the men have already been arrested?" said the former.

"Two gipsies have been taken up, yes. But I was proposing that we should arrest the murderer of Mr. Smithers."

"What's all this nonsense!" broke in Mr. Harbord. "Surely the case against the gipsies is clear enough! The inspector here says that he found one of them in the possession of the dead man's watch. Both are known as notorious bad characters. You yourself saw them near the scene of the murder.

"I really fail to see the point of carrying the matter further in its present stage. The police will look for, and probably find, further evidence, and the case can come up in the ordinary way. If the men can prove their innocence, and that is a possibility we must not overlook, then we can cast about for other clues; but with such a strong prima facie case I don't imagine that there will be much need."

"My case is so strong that I can assure you there will be none at all," was Blake's dry rejoinder, "if either you or Sir Arthur would be kind enough to sign a warrant."

Sir Arthur took up a pen.

"I'll pin my faith on you, Mr. Blake. I don't in the least understand what you're driving at, but I am sure that you do; so here is what you require." And he dashed off his signature.

Blake blotted it carefully, and passed the paper to the official.

"Now, inspector," he said, "if you've a pair of handcuffs with you, perhaps we'd better get this business—— Look out!"

There was a hoarse, inarticulate cry like the cry of some animal in pain, a crash, and a splintering of glass, and Blake, hurling the inspector on one side, grabbed Mr. Harbord's leg just as he was vanishing through the window.

Sir Arthur and the policeman were too astounded to stir for the moment, and Blake had his work cut out, for the man fought like a maniac. He kicked and bit and struggled, and the broken glass nearly-severed an artery before Blake managed at last to drag him back into the room, and get him down.

"The handcuffs—quick!" ho panted. "The wrists behind him—so. That's it; he'll be safer like that."

The bewildered inspector obeyed mechanically, and Mr. Harbord was pushed into a seat.

"For Heaven's sake what's the meaning of this, Mr. Blake!" gasped Sir Arthur. "You don't mean to say that you have any suspicion of Mr. Harbord? The very idea is preposterous."

"I mean," replied Blake, still breathing quickly, "that there sits the man who murdered Mr. Smithers; and if I hadn't happened to be on the spot, so to speak, I can say, without boasting, that it's a thousand to one the true criminal would never have been discovered. The case was one presenting some rather unusual aspects."

Sir Arthur sat down heavily, and covered his eyes with his hand for a moment, trying to collect his thoughts.

"Harbord," he said at last, "in Heaven's name, say there's some mistake! This is like a horrible nightmare! Tell Mr. Blake that for once he is wrong."

Mr. Harbord scowled blackly.

"What's the use," he said.

"The use? Why you—— Man alive, you don't mean it's true?"

"It's my duty to warn you, sir," began the inspector formally, "that——"

"Be quiet, curse you!" cried Harbord; "and mind your own business. I own up, but if it hadn't been for that meddling brute I should have been safe enough!"

Sir Arthur let his arms drop across the table, his face horror-struck but grim.

"Mr. Blake, will you please explain?"

"Certainly. The points of the case are not without interest. To begin with, when I found the body and the men standing round it, I noticed, first of all, that the wound was of a most unusual nature, and the blow had been dealt with almost supernatural force.

"I learnt from the men that Mr. Smithers was a most methodical man, and was well known to return from business by that particular train; that on Fridays he carried a bag of money, and a few other details.

"The money and the watch were missing, and the blow which was the cause of death had clearly been of such force as to roll the body over and over in the road.

"But another thing which struck me was that Mr. Smithers' hat was nowhere to be seen. One would have expected that, having been struck from behind, the hat would be somewhere on ahead. As a matter of fact, I found it eventually, much battered, some considerable distance behind the body. In other words, the body had been propelled a distance of several yards after the blow was dealt. Moreover, the blow itself would have left the hat uninjured, for it was struck at the base of the skull.

"From that, and a peculiar grazing mark on the right side of the coat, I took it for granted that the cause of death was neither more nor less than a motor-car. That would account for the terrific force, the propulsion of the body forward, and the battered hat behind the spot where the body was found. The draught of the car would have hurled it aside, and it was probably flung against some portion of the front of the car and crushed. But for the absence of the money and the watch the whole thing might well have been an accident.

"But I was soon to find that it was nothing of the sort. Taking a lamp, and warning the men to keep clear of the road, I started to see what could be read from the tracks. You may know that it is easy work to tell in which direction a car has travelled by looking at small stones in the tracks. These are first pushed forward and then flung back by the wheels. Again, supposing a small furrow crosses the road, any small sudden drop, the tyres bulge out perceptibly and broaden the tracks. This is also the case when a car is at a standstill.

"Well, on following the car back along its course, I found that it had stood for a considerable time sheltered by the hedge in the lane leading to Helsing Ford, and at a point from which, though himself unseen, the driver could make out the main road towards Helsing from the station. A leakage from the pumps and some lubricating-oil drippings confirmed this.

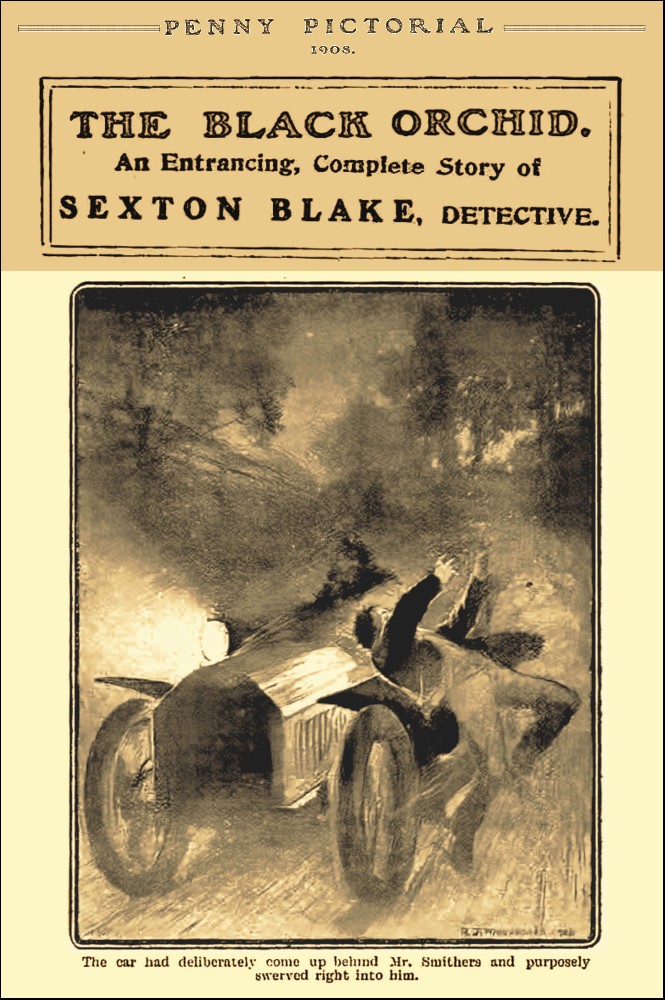

"Following the tracks from there towards the body, I saw, to my amazement, that, so far from trying to avoid Mr. Smithers, the car had deliberately come up behind him and purposely swerved right into him.

"This was easily proved by the fact that the wheel-marks in places overran his footprints, showing that the car came up behind. Now the driver clearly knew Mr. Smithers' habits—that his normal time for passing the junction of the lane and the main road was, say, ten minutes past ten. It is a very lonely stretch just there, and Mr. Smithers, being very deaf, would not hear the car coming. His murderer, knowing all this, had lain in wait for him out of sight, and then run him down in cold blood. The tracks afforded a further proof of this, for at twenty minutes past ten there was a short rain-squall, and the wheel-marks were pitted by the drops, showing that the car had passed previously to that.

"But that is not all. Having run down his victim, the man had pulled the car up thirty yards beyond the body—the tracks bulging showed the place where the brakes had been applied—and run back to make sure of his handiwork.

"To make the crime look like the work of a tramp he snatched away the watch and the bag of money. Then he returned to his car and lighted his lamps—I found there three wax matches in the roadway—and continued his journey.

"Naturally he would not keep things so incriminating as the watch and the bag an instant longer than necessary. The first he flung into the wood as soon as he got a little way away. You will see that it got battered and dented in so doing, for it has stopped at 10.21, showing that it was still going when taken from the body. The gipsy was probably poaching when he found it.

"The bag of money, I fancy, will be found in the small stream where it runs under the bridge on the way to Helsing. It would be the easiest way of disposing of it.

"To continue, I borrowed a bicycle and a lamp and I followed up the tracks. It cost me a night's rest, for the car went a round of some forty miles. I asked several people whom I passed outside Helsing whether they had seen a car. As luck would have it two of them had. It was going at a furious pace, and one man—a carter—had taken the number, as it had scared his horse.

"The number was E 10073. Now, that struck me as curious, for E is the mark of the Staffordshire cars. The Essex mark, as you know, is F.

"It seemed to me that it would be an easy matter to turn an F temporarily into an E, and I noted the fact.

"To cut a long story short, after missing the trail once, I eventually traced the car here to this house. Then I turned my attention to other matters. A cipher wire, in answer to one I sent, soon gave me the name of the owner of the number F 10073, just as a check on my own discoveries. So I knew my man, but the motive was lacking.

"That also I discovered. Smithers had told several acquaintances that he expected to make his fortune soon out of his flowers, but said nothing more. I examined his hothouses, and there, to my amazement, I discovered, carefully stowed away behind others, a magnificent black orchid."

Sir Arthur gave a start.

"Precisely," said Blake. "You see my point. Some fortnight ago I read that two splendid black orchids had been shown, and that their exhibitor, Mr. Harbord, had refused six thousand pounds for a single specimen.

"He had stolen the pollen from Mr. Smithers originally, and had fraudulently posed as the real grower of this unique "sport," which, from its rarity, would be worth a fortune from a collector's point of view. Mr. Smithers had evidently either heard of this, or Mr. Harbord knew that he must soon inevitably do so; and, rendered desperate at the thought of the scandal and exposure which must follow, took a desperate way out of the difficulty—a way which almost succeeded.

"I had a look at the number-plate of his car just now, and at the base of the F there are two distinct ruled lines—the outlines of the base turning F into E. He had filled these up himself with some black stuff, and, as soon as he was clear of this part of the country, wiped it off again.

"And now, inspector, I should advise you to take your man along and lose no time in letting out those gipsies, or they may cause trouble."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.