RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

BLAKE glanced at a small advertisement in the"Wants" column of the "Mail" for the fifth or sixth time and frowned—and took a long pull at his pipe.

It was short and plainly worded, but it worried him.

It ran as follows:

"Five Pounds Reward!" And then in smaller type; "The above sum will be paid to anyone who can supply undamaged copies of the 'Times' newspaper for November 18th of the year 1883, and also for November 19th of the same year, and a further sum of five pounds for copies of the 'Telegraph' of the above dates. Address Box 87606, 'Daily Mail,' E.C."

Now, file copies of back numbers of newspapers are fairly accessible to anybody. The five pounds' reward, then, clearly indicated that whoever wanted those particular copies wanted them to deface and make cuttings from; also the sum was sufficiently high to induce someone to part with a bound volume, it being most unlikely that a single newspaper could have stood the wear and tear of close on a quarter of a century.

Still, the fact that someone was willing to pay ten pounds for four papers not worth as many pence perplexed Blake, it even made him irritable and restless. He compelled himself to think of other things, but always that insidious advertisement kept running in his head.

At last, with an exclamation of annoyance, he picked up his hat and strode off down to his club, the threshold of which he had not crossed for months. After a frugal lunch he went straight to the club library, which was a fine one, and contained four huge shelves of massive bound newspaper volumes. He selected the two he wanted and retired to a table near by.

After a couple of hours' careful scrutiny of their contents he came upon one paragraph, and one only, common to all four papers, with the exception of certain stock trade advertisements.

The paragraph itself ran as follows:

"Re Oscar Browning, of Melbourne, lately deceased. His heirs or next-of-kin are hereby earnestly requested to communicate with Messrs. Horner and Howell, when they will hear of something to their advantage. Oscar Browning left England in or about the year 1872, up to which time it is believed that he was resident in the county of Surrey.—Address Messrs. Horner and Howell, City Street, Melbourne."

Blake jotted the thing down verbatim. Why he did so he could hardly say; he had an instinctive feeling that it might come in handy.

He glanced over some papers of previous dates, but could find no other reference to Oscar Browning, and returned home dissatisfied.

IT was nearly a week later when the name was recalled to him in an unexpected fashion.

There was a ring at the bell, and a young man came in announcing himself as Mr. John Browning.

Blake's eyes gleamed, and he shot a quick glance at his visitor with newly-awakened interest. He guessed that Mr. John Browning or his agents had inserted the offer of five pounds reward.

The man was slightly over middle height—carefully dressed in a conventional frock coat, which showed that it had been cut by a good West End tailor, and the top hat which he placed gently on Blake's table was immaculately ironed. He had heavy black eyebrows, which nearly met on the bridge of his nose, and a neatly-trimmed dark moustache, which only partly concealed a determined-looking month. The eyes were sharp and penetrating, and his worst enemy would not have written Mr. Browning down as a fool. His manner was that of a man sure of his ground and perfectly at ease with himself.

Blake guessed his age at twenty-five or six.

"Mr. Blake?" he said inquiringly.

"At your service," said Blake, and turned a little in his chair so that his visitor was compelled lo face the light more fully. Blake fancied that his visitor detected the move and smiled faintly. Mr. Browning gave him the impression of a young man who was very wideawake.

His next move showed that he was, at any rate, businesslike, and used to coming to the point quickly. For, placing his hand in his pocket he drew out a neat leather case from which he selected a piece of paper and laid it before Blake.

It was a half sheet of notepaper on which was pasted a, soiled and crumpled but perfectly legible newspaper cutting. Above, in a clear, bold hand, was written, "From the 'Times' newspaper, November 18th, 1883."

He produced also a letter which he laid beside the cutting.

"Kindly glance at those," he said. "for they contain the gist of the matter which I have come about. I received them some months ago from the friend whose name you see there."

The letter was brief.

"Dear Jack,—In going through an old book of news cuttings belonging to my father I came across the enclosed. Knowing that my father and yours were friends of long standing, and that some of your people went out to Australia, I thought it might possibly be of interest.

"Yours ever,

"Tom Wilkinson.

"P.S.—If you come into a fortune, yours truly will expect a fat commission."

There was no date and no address, but the letter read naturally and easily.

"I received that some time in August," said Mr. Browning, "and since then I have been hunting up old family papers and making inquiries. My first step was to verify the advertisement by turning up the files, and I believe my lawyers tried to obtain copies of the paper. My second was to find out what I could about Oscar Browning, of Melbourne. I discovered that he was my grandfather, and that he went to Australia about the time mentioned. He started a small sheep-run up in the back country somewhere. Gold was found on the run, and he amassed a huge fortune in a few years.

"He had left his wife and son—my father,that is—at home, not liking to take them out until he himself was settled. They were compelled to move from place to place by force of circumstances, and if he communicated with them subsequently the letters failed to reach them, and they were ignorant alike of his whereabouts and his death. At the time of his decease he was worth, I am told, some million and a quarter sterling; that was twenty-four years ago, so you can imagine that the property is far more valuable now, with accumulated interest, and so forth. He died intestate, and the estate has, up to now, swelled the list of 'unclaimed monies.' I have here"—he laid more papers on the table—"copies of the various necessary certificates for the establishment of my claim, the originals can be seen whenever you choose."

"Then I am to congratulate you on inheriting a large fortune," said Blake drily. "At the same time I fail to see why you are here." As a matter of plain fact, Blake was beginning to see daylight; at least he began to see the reason of the five pounds reward.

THE copies of the various certificates before him showed that his visitor's father—one Henry Browning—had died in 1890, in which case it was strange that his old friend Wilkinson, who had seen the cutting in 1883, had not thought it worth while to communicate with him, though, according to the letter, he had thought it sufficiently important to paste in a book.

Obviously, Mr. John Browning had come to the knowledge of his inheritance in some roundabout and not over-reputable way; and equally obviously he was in need of some natural explanation of his sudden interest in the matter. Which was accounted for by the accommodating Tom Wilkinson's letter and enclosure which, before it had been artistically soiled and crumpled, had cost John Browning himself five golden sovereigns.

Blake foresaw a swindle on a large scale, and bided his time.

"You were saying—— he suggested.

"I was saying that you might have reason to congratulate me but for one point, which is, in short, the cause of my being here. All the papers are in order and above dispute but one. I cannot trace my grandmother's marriage certificate. Her name was Latimer, and she was married to Oscar Browning, in 1864, at the Church of St. Botolph's, at Long Withem, in Surrey. I know that from certain family papers which can be produced, and also from hearing my father speak of the date of his parents' marriage. Unfortunately, the certificate is nowhere to be found, and, to make matters worse, St. Botolph's, and all the records which were kept in the vestry, was burnt in a disastrous fire in the late Seventies—1878, I think. I have come to you to help me find that certificate. I have heard wonderful things of your ability, Mr. Blake. You can see for yourself that without that certificate my claim is invalid—or, at any rate, open to doubt; and I am willing to pay a large sum—a very large sum—if you can find it for me. I will place the figure as high as fifty thousand pounds to he paid on the day my claim is acknowledged, and I will give you my bond for that amount."

"Fifty thousand is a very large sum; but on the other hand, the estate is worth by now all of a couple of millions," said Blake slowly.

"The issue at stake is too great to haggle over details," answered Browning. "I will go as high as seventy-five thousand—come, Mr. Blake, every man has his price—seventy-five thousand for a piece of paper."

A queer light crept into Blake's eyes.

"But why come to me with your offer?"

"Because you have the reputation of being the cleverest man in Europe at discovering things. And also, I once read a monograph of yours on old inks and papers and their distinctions. You should be able to know whether a document is genuine or not better than any man living."

Mr. Browning leant across tho table confidentially. By accident or design his fingers rested on an old faded letter signed Oscar Browning, beneath which lay another in a quaint, old-world handwriting, bearing the signature of Mabel Latimer. Blake had not the slightest doubt that both were genuine.

"Seventy-five thousand pounds," repeated Mr. Browning slowly, and glanced round the shabby room. Then the eyes of the two men met.

"It is a large sum of money," said Blake, and looked away. "I—perhaps I will look into the matter. Mind, I promise nothing. In any case, it will be very difficult," he added quickly.

Mr. Browning gave a sharp sigh of relief.

"I will leave these papers with you," he said. "What line do you propose to take?"

"I shall run down to Long Withem to-morrow," said Blake. "One has to be sure," he added.

Mr. Browning smiled.

"Quite so. On the day you succeed I hand you the bond. Good-day, and many thanks. My address is there on the card." He replaced his hat at a jaunty angle, nodded affably, and walked quickly out.

Blake waited until he heard the front door slam, and then gave vent to a quiet but prolonged chuckle.

The idea that he was to be hired as an expert forger at an exorbitant sum, because they were afraid of him, he found distinctly amusing. Nevertheless, the next morning he went to Long Withem.

MR. BROWNING proved to be a painstaking young gentleman. St. Botolph's had been burnt to the ground in Easter, 1878, owing to a candle setting fire to the reredos, and all the records had perished with the building. Blake made several inquiries, and the more he inquired the more his admiration for Mr. Browning rose by leaps and bounds. He had openly, it appeared, spent a month in the village pestering people to death with questions about tho registers, and had ascertained beyond all doubt that there was no one who could turn up at an inconvenient moment and upset his story.

On his way to the station, however, Blake made a discovery. A man came down the road past him, perched on the seat of a tradesman's cart, chatting away affably to the driver. He did not see Blake, but Blake saw him, and, what is more, recognised him for one Joseph Bramson—a shark solicitor with a most unsavoury practice, which had earned him the name of the "Ferret"—a little, shifty eyed, red-haired, sallow-faced brute of a man, with a face like a rat's.

Blake surmised that the "Ferret" had been down to Withem on affairs not wholly unconnected with Mr. John Browning.

He watched him into a third-class carriage, and took his seat in the next compartment. They reached town a little after one, and Mr. Bramson—originally, presumably, Abrahamson—took the Tube to the nearest point to his offices in Chancery Lane.

Blake, who was perfectly well aware which floor they were on, followed him, and went further up the dimly-lit passage, ostentatiously studying the names on the glazed doors.

Five minutes later Mr. Bramson reappeared.

"I sha'n't be back till 2.30," he bawled over his shoulder. "You can go to lunch, and be back in a quarter of an hour. If anyone calls say I sha'n't be free till four." And with that he was gone.

Knowing the nature of office-boys, Blake waited another five minutes, and a dishevelled youth came out, smoking a cheap cigarette. Bramson was much too mean and too artful to keep a clerk. The boy locked the door carelessly behind him, and Blake felt in his pockets for a piece of wire.

He had to compromise on the pipe-cleaner in his knife, however. Before the boy had reached the street Blake was standing inside the outer office.

Blake passed into Mr. Bramson's sanctum. The furniture was of the shabbiest, and a flimsy safe—which made him smile—stood in one corner. Blake had sized-up his unwitting host pretty accurately, and bothered little enough about the papers lying on the desk or in the drawers. Anything of any special value would, he was certain, be more securely and artfully hidden. But he took the liberty of inspecting Mr. Bramson's blotting-pad, holding it up sheet by sheet to the light reversed.

On one page be made out some lines to Messrs. Ewell & Ewell, solicitors, re Oscar Browning in Chancery.

He noted the name—that of a highly respectable firm of solicitors. It was clear that they were working for Homer & Co., of Melbourne.

On tho desk,in a central position, was a faded cabinet photograph of a burly-looking, middle-aged man, with old-fashioned whiskers. It had been taken in Melbourne; and, in brownish ink, scrawled across the face, and badly smudged, was the signature, Oscar Browning.

Blake examined it attentively, and noted the signature was the same as that on the letter which John Browning had left for his assistance. He turned the thing over and examined the back, which had been badly mauled and rubbed, and misused. Apparently it was bare of everything but dirt-stains, and the printed trade mark of the photographer.

He held it up to the light sideways, and looked along the surface for any trace of an inscription. His sharp eye caught a few insignificant scratches indented in one corner.

He looked along the card, so that the light fell slantwise, and the scratches became legible in patches. He made out that someone had scribbled a word or two in pencil, though of the actual pencil marks nothing remained. They had been rubbed away long ago.

"To m——" he read slowly. Then came a gap where the back was torn. "—aughter Lucy," it went on; and after that what had evidently been a date, but only the initial figure 1 and something resembling a 5 were left.

Blake gave a low whistle of astonishment. Oscar Browning might have had a son. Blake began to think it doubtful, but he most certainly had had a daughter to whom he had sent a photograph from the colonies in 1875, for that was the only date during his stay in Australia which could possibly contain a 5. Blake had a mental vision of the man out there working hard to make a home, and sending an occasional letter to the Old Country when chance offered. Then the discovery of gold; and, in the sudden rush to get rich, wife and daughter were alike forgotten till too late, and all trace of them had been lost—perhaps, amidst new interests, forgotten altogether.

He placed the photograph carefully back on the desk, and as be did so he heard the handle of the outer door turn, and Bramson's voice cursing the office-boy, still absent, for his carelessness in leaving it unlocked. Blake glanced swiftly round. Mr. Bramson's return was distinctly mal-à-propos.

In one corner stood a dirty old baize four-fold screen. Blake eyed it. It did not seem to have been moved for years, judging by the dust, and had probably been taken over with the office from some former owner. It was a risk, but it had to be taken. Blake dived behind it just as Bramson appeared, followed by Mr. John Browning and another man, an evil-looking brute who smacked of the country and the sea.

The man was clearly nervous and ill at ease—as was Mr. Bramson. Browning alone seemed master of the situation and himself.

"Well, Rorke," he said, lighting a cigar, "so you want more money, do you? Things are a bit tight just now, till I come into my property. Still, I dare say my lawyer, Mr. Bramson here, can let you have a bit to go on with."

Bramson scowled, and the man addressed as Rorke twirled his hat.

"I'm goin' to have my fifty quid afore I leave here, or I'll know the reason why!" he said sullenly.

Browning puffed at his cigar.

"Fifty is a bit stiff," he said.

"So's other things I know of!" grunted Rorke surlily, "down Widcombe way."

There was a silence in which you might have heard a pin drop, and then Bramson gave something like a gulp.

"Things ain't no business o' mine," continued Rorke, "and I ain't one to poke my nose into other folk's affairs, but if I'm to do as you wish, I want fifty pound. Ay, and another fifty on top o' that, and may be more, when you come into all that bit of money you keep on talkin' of. I'm Widcombe born and bred, I am, and I know the rocks, and the set o' the tides and the caves." He paused significantly.

"You've already had twenty-five for keeping the girl there," said Bramson shakily.

But Browning, shrewder and more daring, burst into a laugh which, however, he failed to make ring true.

"You're the man for my money!" he said, and slapped Rorke on the shoulder. "Look here," he added, lowering his voice to a whisper, "supposing it was not a matter of fifty, but of ten times, twenty times fifty, what would you do, eh?"

Rorke shifted uneasily in his chair, and Blake heard it creak.

"There's no risk," continued Browning, speaking in a whisper. "You say the girl moons about the cliffs all day, and till long after dusk, looking for—for what she can't find, eh? You know the cliffs and the tides, and the rocks. Supposing there was an accident—a piece of cliff edge worn loose by the rains, a slip on to the rocks below, eh? From that height it would be fatal. You would be the first to alarm the village. You know the dangerous points better than anyone else. You are the foremost of the rescue party, and you would arrive too late. Man, it's as easy and as safe as winking! And a thousand pounds—think of it!"

"How do I know?" said Rorke huskily. "I ain't trusting no man. How do I know the money's safe? For the rest, I tell you plain I've got you cornered, so there! I know them caves well, I do, and——"

"I'll sit down now," broke in Browning hastily, "and write you out a note promising to pay you a thousand pounds. If I don't, you know what you can do!"

"Ay!" said the man surlily.

Browning wrote rapidly and handed him a slip of paper.

"Bramson, write Rorke out a cheque for fifty, and you, Rorke, listen. When you get a wire from me, 'sending ferrets,' you do what you've agreed to in your own way; and when its done, wire me to Charles Street, in the name of Smith, 'ferrets arrived safely.' Do you see? If you fail, there'll be no thousand pounds, that's all. Don't be seen here again for a while."

Bramson turned on his client angrily the moment the door had closed.

"You fool! You triple fool! You've done it now! That brute has got us under his thumb, and you give him a paper signed with your own name—a bond for a thousand pounds, and you make me write him a cheque for fifty. It's the last money you get out of me, I can tell you!" he stuttered.

Browning puffed out a cloud of blue smoke.

"You have your points, Bramson, but you're an ass. If you hadn't given him that fifty to keep him quiet he would have split on us. I tell you the man is mad for money—worships it, and doesn't care a fig for anything else. Besides, he will do what I suggested, and when it is done I shall give him his thousand. I believe in keeping faith when you must. Of course, he will try and blackmail us afterwards; then I shall tell him that he has overreached himself, and recommend him to go to the— er—well, the States."

"What of this man Blake? Could you square him?"

Browning nodded.

"The fellow's as poor as a rat, and lives in a poky hole of a place in Chelsea. We fenced a bit, but came to terms in the end. The figure was stiff, but we dare not risk having him against us."

Bramson rubbed his hands and nodded.

"That man is a curse to us; he frightens me. All the same, I was right; every man has his price. I made inquiries. He was down at Long Withem this morning. I did not see him, but I ascertained; also I did not myself wish to be seen, and came away early."

"Talking of price," drawled Browning, "you'd better let me have another hundred to go on with. I'm at the end of my tether."

"Not a copper," snarled Bramson. "Good heavens, do you think I'm made of money? Four hundred pounds have you had from me since this began."

"You niggardly old miser! And you'll get back four hundred thousand!" roared Browning. "I tell you sometimes I feel inclined to split on the whole show and chuck it, when you make all this fuss about a few beggarly tenners."

"You split—you!" Bramson almost screamed. "And what if I tell them how you and Malet went for a walk one night and you returned alone, and that since then his daughter has been wandering up and down the cliffs searching for him or his body!"

"You will be the first one in trouble," was the grim reply. "I took good care of that. A torn letter addressed to you lies beside him, and a hand-kerchief with your initials is not fifty feet away. Come, Bramson, don't be a fool. I must have money to keep up appearances. It's only a matter of a week or so now, and we have Ewell & Ewell practically on our side already. As soon as this man Blake produces that certificate the property is as good as ours. I couldn't help it about Malet; it was unfortunate, but it was imperative. The man knew that Oscar Browning was his father-in-law. Wasn't it that very photograph which he had on his mantelpiece? He was a shiftless, easy-going man, like most artists, and rarely bothered to read a paper, and, of course, he never saw Horner & Howell's advertisement. But when the case comes on, and the papers have headlines about the heir to the Browning millions having been found, don't you think he would have seen it then? Of course he would. And when he came forward where should we have been, eh? I quite admit that you started the game ferreting round, having some knowledge of old Browning, and routing out these Malets. But unless my name had also been Browning, and the dates so nearly coincided—and if, too, I hadn't planned the whole thing and had the brains to bridge the difficulty by discovering the burnt St. Botolph's—where would you have been? A paltry solicitor's fee and some thanks if you had gone to the Malets. Nothing at all, if you hadn't. Come, don't be such a fool! Write me out a cheque. I can't appear before the solicitors and people like a penniless beggar. They would grow suspicious. A hundred ought to see us through easily, and in a week—two weeks—you'll be worth the better part of half a million."

Bramson sighed, and yielded with an ill grace. Browning took up the cheque, and with an airy nod and a "Thanks, old man; so-long!" strolled out, just as the office boy returned.

Bramson needed a scapegoat. He cursed the boy roundly, flung five shillings at him in lieu of notice, and swore to set the police on him if he ever crossed the office threshold again.

BRAMSON, left alone, sat for some time, with his head bowed on his hands, then he mopped the perspiration from his brow, dived into the safe, and producing a bottle of brandy and a glass, poured himself out a four-finger peg, added a little water from the office water-bottle, and drank it off. Browning and Rorke between them had given him a nasty turn. The spirit brought a spot of colour to his checks.

"You think you've done me, do you, you sneaking hound," he muttered, shaking his fist at the departed Browning. "I'll be even with you! I'll drain you of every penny, every farthing; and you shall be lucky to live on what I choose to dole you out!"

He rose and crossed the room, with an indescribably furtive, stealthy look in his eyes.

Blake watched him through the slit he had cut in the baize screen. Over the little fold-up wash-hand-stand was a cheap sixpenny shaving mirror in a stained frame, badly cracked.

Bramson looked around him, and took it carefully from its nail, raised a corner of the backing-board, and peeped inside.

"All safe," he muttered; "quite safe. Wait, you Browning—you, and you shall pay me such interest as no man ever paid yet!"

He replaced the mirror, took another pull at the brandy-bottle, and locked it in the safe.

"No more work to-day, Joe," he said to himself a little thickly. "No more work to-day; soon no more work at all any more. Phew! The stuff's got to my head; I must get out into the air."

He took his hat and umbrella, slammed the door, and locked it on the outside.

BLAKE, cramped by long waiting, stretched himself and gave a sigh of relief.

Then he strode straight across to the dingy little mirror, noted the exact arrangement of the back-boards, pulled out the top half, and shook out a small bundle of papers folded very flat.

He opened the first one and glanced at it with glistening eyes.

It was five o' clock when he left the office at last, the lock presenting no difficulty. In his breast-pocket lay a small bundle of papers, behind the mirror a similar one—only those behind the mirror were blank, those in his pocket were not. And he was chuckling drily.

THAT evening he wrote to Mr. Browning, and made an appointment for early the next day.

Mr. Browning, glossy hat and all, was punctual to the moment.

"Well, how goes it?" he asked.

Blake had on the table several kinds of pens, an assortment of different inks in all sorts of bottles, and a number of official-looking forms, some torn in half.

He pushed one that was not torn across to Browning, together with the two letters left by that worthy. The paper purported to be the marriage certificate of Oscar Browning and Mabel Latimer, at St. Botolph's, Long Withem, in 1864.

John Browning glanced, compared, and glanced again.

"By Jove, it's miraculous!" he cried. "Marvellous! A work of genius!"

Blake smiled.

"I admit that the colour of the ink is a possible imitation of what one would expect; also the wearing of the outer folds of the paper. I looked at those under a microscope."

"It's wonderful! Now, look here. A long time ago my grandmother, who I can prove was, beyond all doubt, Mabel Browning, lived at a farmhouse near Beeding—about 1874, I fancy. There's the address. You slip down there to-morrow with this in your pocket, tell the people of the house, and ask permission to look for some old papers which may have been left there. Offer them twenty pounds if you like. Better take a couple of days over it, so as not to look suspicious, and take care one of the people of the house is with you when you find it. Then wire to me and we'll be off to the solicitors, who have the matter in hand as soon as you reach town."

"There's one thing you've forgotten!" said Blake quietly.

"What's that?"

"Your note of hand for my remuneration."

"By Jove! I'll soon square that. Give me a pen." He dashed off a few lines and signed it. "Will that do?" he asked.

Blake nodded.

"I shall have it stamped at Somerset House," he said.

"By all means. So-long!" And Mr. Browning was gone.

BLAKE left town within an hour, but not for Beeding. Before he left he deposited a telegraph form at a boy messenger's office, with instructions that it was not to be sent before five in the afternoon. It ran:

"RORKE—WIDCOMBE—SENDING FERRETS."

THE cliffs at Widcombe are of chalk, very high—in some places overhanging—and very dangerous.

Even the coastguard's path over the downs, marked by white boulders at regular intervals, lies thirty paces from the cliff edge at the nearest point. They know tho danger, but even they do not know thoroughly the drops and windings of the smugglers' caves, long since fallen into disuse.

The night was cold and frosty, with a dark, heavy, swirling mist, which blotted out everything at five paces and less, and rendered the coastguards' safety marks hard to find.

Yet there were two solitary figures striding over the path just inside the coastguards' line. One a girl dressed entirely in black, with a heavy cloth golfing cape round her shoulders, and the hood drawn over her head. In her hand she held a small artist's satchel and a light, folding camp-stool. She was tall, and moved with an easy grace, the free movement of one accustomed to open-air exercise, but her face was pale and distraught.

Beside her walked a heavily-built man, whose face, if she had only noticed it, was also pale, and who glanced anxiously about him as he strode along, speaking to her in an oily, almost pleading, voice.

"Come along, miss, you come home. It ain't a bit of good your being out here; and what's more, it ain't safe. I tell you the word's gone all along the coast to keep a look out if—if anything should be washed ashore. You come home with me. The missis is that anxious you can't tell—that's why she sent me to fetch you. Twelve o'clock it was, when you went out to do your bit of painting, and here it is past eight of the night."

"Very well, Mr. Rorke," said the girl wearily. "I suppose it is no use; but somehow these cliffs seem to hold me against my will. If only I knew what had become of father——" She checked herself with an effort. "I am ready. Let's go;" she added. "I'm afraid I have given you a lot of trouble after your long day's work."

"It ain't the trouble I mind, miss," he said gruffly. "Don't you worry. And as for your father, he was always a bit odd like, since I knew him down here. I mind once when he was away close on a fortnight before, an' never a word said. Maybe he'll turn up this time again all safe and sound." He passed his tongue across his dry lips as he spoke, and glanced over his shoulder. "You come home along of me." And deftly he edged her out to the left, between two coastguard marks, towards the drop of the cliff.

After a few more paces, the girl turned suddenly.

"We've missed our way. We should not be walking uphill here," she cried. "We must have lost the path."

"Not much!" said the man uneasily. "I could find my way about this part blindfold. You trust Bob Rorke, missy."

Whether the man over-acted his part or not, or whether the girl's intuition served her, would be hard to say. Anyway, she glanced at him suspiciously and swerved.

"I tell you we have!" she cried, and started to ran.

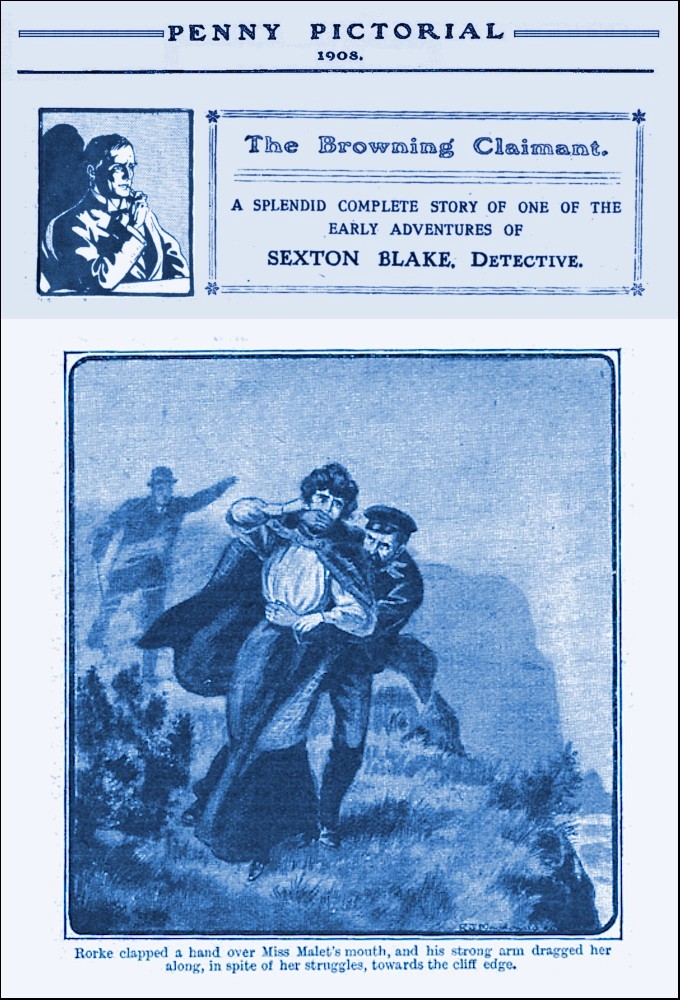

He caught her roughly by the arm.

"Nonsense, you little fool, you'll be over the cliff that way! Come with me!" And he forced her forwards.

Her quick ears caught the boom of the surf now; they were not five steps from the edge, and the grass was slippery.

"Let me go!" she cried again. "Ah, you brute! Leave go my arm! I see now—I under——" A heavy hand was clapped roughly over her mouth, and Rorke's strong arm dragged her along, in spite of her struggles, and she was a powerfully-built girl.

SUDDENLY from the mist behind another arm shot out, and wrenched her free. Rorke turned with a savage snarl and an oath, and before it was complete he was on his back with a broken wrist.

"You cur!" said a voice coldly, "get up and walk in front of us the way you came. If you attempt to run, I'll put a bullet through your leg. Now then, sharp!

"Miss Malet, let me introduce myself: my name is Blake, and I have news of great importance for you—some good; some, I am afraid, bad. Will you come with me to the Inn? I have warned the landlady of your arrival, and she has made all arrangements. As soon as we are there I shall turn this fellow over to the police. His house is no longer safe for you."

The girl glanced at him piercingly through the reek of the sea fog. "I owe you my life," she said. "I trust you implicitly."

THREE days later Blake arrived at the offices of Messrs. Ewell and Ewell by appointment. Mr. John Browning was there, also Mr. Bramson and both the senior partners of the firm. Further down the street were two four-wheelers; in one sat Miss Malet alone, dressed in deep mourning: in the other Rorke with one arm in a sling, the other wrist handcuffed to a constable who sat beside him; in front sat a plain-clothes officer. Mr. Browning did not know this.

The elder Mr. Ewell came forward and shook hands with Blake. "We know you well by reputation, Mr. Blake," he said, cordially; "my friend here tells me that you have added another case to your long list of successes, in this affair."

Blake bowed, and Mr. Ewell turned to speak to a clerk.

Mr. Bramson sidled up. "You have it with you, Mr. Blake, eh? We've had our little differences in the past, you and I, but now we are both in the same boat, my dear sir; you are prepared to swear that you found the—the document in the old Beeding farm, according to your telegram. What?"

"Certainly," said Blake, drily; "here is the document. Shall I give it to you or Mr. Ewell?"

"To him, by all means, with your own hands," said Bramson, quickly drawing back.

Blake did so; both partners scrutinised it, compared signatures and dates, and examined it most carefully.

At last tho elder spoke, turning to Browning. "I must congratulate you on placing the search in such able hands, and on your consequent success. This paper seems perfectly in order, and, of course, completes the documentary evidence of your claim. We have already gone into the other papers put forward, and with this I feel justified in cabling Messrs. Horner and Howell. The rest, as there are no disputant claimants, will, I fancy, prove merely a matter of a few weeks' delay, in deference to the formalities of the courts."

Bramson simpered and Browning's face grew flushed, though he tried to appear calm.

Mr. Ewell turned to Blake. "You will, of course, be prepared to swear to the finding of this document, Mr. Blake, as a mere matter of form."

Blake, by imperceptible degrees, had made his way to the door, which he locked with his hands behind his back.

"Certainly," he said, drily, "I had placed it there myself before."

Browning leapt to his feet and Bramson gave a strangled cry, like that of a cat in agony.

"Sit down," said Blake, sternly, "both of you; there are men waiting on the stairs out7side. Mr. Ewell, kindly hold that paper up to the light; it purports to have been signed in 1864; the water mark, you perceive, is quite modern; in short, the thing is a forgery."

Mr. Ewell gasped. "But, my dear sir, what—that is, who forged it?"

"I did," said Blake, curtly. "There is that man's note of hand for a large amount—the fee he had the impudence to offer me for the job."

Mr. Ewell's face went grey and his hands dropped to his sides.

"I can prove it," said Blake, "not only by the marks on the paper, but by the ink, which, though faded, any expert will tell you is a modern aniline ink watered down—aniline dyes and inks were not invented in 1864. Moreover, here are some papers—genuine ones, which I have been at some pains to verify, which may interest you. I took them from behind the mirror in the man Bramson's office.

"They prove conclusively that Oscar Browning married in 1863 (not 1864) and had one child, a daughter—not a son; she married subsequently an artist, named Malet, who also had a daughter. I can assure you that everything is in perfect order—a point on which you can satisfy yourself later—the lady is waiting in a cab below now. I will call her up in a few moments, but there is something else to be done first. Let me explain; This man Bramson, whose reputation is well known to the police, stumbled across the secret of the Browning inheritance—he was in Australia himself for a short time—he also came across this other man, whose name really is Browning, and who had family papers proving his right to the name up to a certain point, though he is no relation at all. Oscar Browning, as you will see later, was married in Colnbrook in 1863. I have examined the register.

"This did not suit Bramson's plans, and he and this other man laid their heads together, and concocted an ingenious plot to supply the missing link. They found a church which had been burnt down, and set to work to get someone to forge a certificate of which no duplicate was extant.

"Previously, however, the real heir, Malet, became a possible stumbling block, should he, by chance, hear of the ease; for he knew that he had married Oscar Browning's daughter.

"Bramson stole his papers—those I have just, given you. Browning murdered him on a foggy night on the Downs. I have a man below, named Rorke, who is in custody, and who saw him do it, and has shown me the spot where the body lies; it was dropped into a deep cave.

"Not content with that, both men conspired to induce Rorke to kill Miss Malet. I caught him in the act. I hope I make myself clear. With your permission, then, I will just call to the officers outside to take this precious couple in charge, and then we can fetch Miss Malet up and go through the papers.

"Kindly ring for one of your clerks to give the men on the stairs Mr. Blake's compliments and ask them to stop in.

"There need be no fuss. Thanks. As soon as the road is clear, I'll bring you Mr. Oscar Browning's heiress."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.