RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Kaiser's Speech—The Base in the North Sea—

What Did He Mean?—Sexton Blake to Decide.

"THESE manoeuvres—what will they show?" Colonel von Harmann asked in a rather sneering tone of the junior officer who sat next to him.

"Why, many things," Lieutenant Krantz answered doubtfully. "There is the test of seamanship, the—er—"

"Seamanship!" the colonel growled. "Himmel! What does seamanship count for in a modern sea battle? It would just be hammering away with the great guns, and the one that got the right shot in first would win. A game of chance—like all these affairs of war!"

This conversation was taking place at the mess of the First Regiment of the Kaiser's Pink Dragoons, and, as usual, the conversation after dinner had turned upon the subject of arms, for your German soldier is a man who makes more than a light study of his profession. He loves it until he believes that nothing could stand against his army and its organisation. And on this particular night there were the coming British naval manoeuvres to discuss, the meeting of more than three hundred war vessels in the North Sea. Not for years had such a huge naval demonstration taken place, scarcely ever before had strict secrecy with regard to them been kept to the extent of not allowing even distinguished spectators aboard the ships while the mimic fighting, the attacking and repelling, was in progress.

It was this secrecy most probably that had attracted to the eyes of all countries to the North Sea. Previously Great Britain, proud in her great naval strength, had not hesitated to make quite public all her manoeuvres by sea, yet this time—

Other nations, including some who could scarcely be said to love the little island, were asking each other what it meant.

Colonel von Harmann lit a large cigar, and puffed away jerkily. He felt in the mood for argument, and the young lieutenant was likely to prove rather an easy victim.

"And why," he asked, "has the North Sea been chosen for the scene of this affair?"

Lieutenant Krantz twisted his wineglass between his fingers, and his high German forehead, crowned by bristling hair, puckered thoughtfully. He parted his lips to give an answer, but before he could do so one came right from behind the colonel's chair

"But I can tell you, friends," it said. "Britain has just awakened to the fact that it is from the North Sea that she is most open to attack."

Colonel von Harmann turned sharply, then sprang to his feet, his hand going up to the salute.

"The Kaiser!" someone else ejaculated; and, with a clattering of chairs, every officer was on his feet.

Wilhelm II, Emperor of Germany, flung off his long military cloak, revealing the fact that he was wearing the uniform of a colonel of the regiment; and certainly, with his upturned moustache, and rather grim expression, he looked a soldier to the life.

"Be seated, comrades," he said quietly. "There is no need for officers to stand to welcome a brother officer."

In obedience to this permission the officers, who numbered rather more than a score, dropped back into their chairs again, and the Kaiser seated himself beside Colonel von Harmann.

"A cigar, your Highness?" the latter suggested, pushing a box forward.

"No, colonel," the Kaiser answered, with rather a wry smile. "The throat is still troublesome. But you were discussing when I came in?"

"The value of these British naval manoeuvres in the North Sea," the colonel answered promptly.

The Kaiser laughed softly and sipped the glass of wine that the colonel had poured out for him.

"Their value?" he echoed.

"Yes, sire," Colonel von Harmann glanced keenly at the upright figure beside him. He knew, as many another powerful man in Germany did, that the Kaiser was perhaps the best informed man in the country, and that his opinion was one to be relied upon.

"So." The Kaiser sipped at his wine again, then the smile died from his lips, and he rose to his feet. Instantly every eye was turned upon him. There was something curiously strong about the rather spare, upright figure.

Memories of other speeches that had stirred the political world, of letters written in hot haste and afterwards repented, entered the minds of the officers present, and some of the older ones regretted that a few civilians were present. Through them things might leap out—things that were better left—

"Comrades"—the Kaiser's voice rang out strongly, though with just the touch of hoarseness that told of a throat liable to give trouble at times—"some of you were discussing why these manoeuvres are to take place in the North Sea.

"The explanation is not hard. For years and years the British have thought only of the south as the point where they would be attacked in case of war, and there they have built their great forts, and sunk their mines, and held their ships in readiness, making their position so strong that it would have taken more than an ordinary foe to go against them with a chance of success. But now"—the Kaiser threw out his right arm with a dramatic gesture—"they have looked towards the north, and into their brains has come a certain thought."

There was a pause, so silent that it seemed as if every man in the room was holding his breath.

"In the North lie the Shetland Islands"—the Kaiser spoke slowly and distinctly, as if he did not wish a word to be lost—"unprotected, yet the finest base a force attacking Great Britain could possibly possess."

"Why have we not examined them?" Colonel von Harmann muttered excitedly, but not in so low a tone that the Kaiser failed to hear him.

"But we have!" The Kaiser's voice rang enthusiastically, and there was a grim little smile on his lips. "We have no enmity with England now, but even then we do not blind our eyes to the future. Some day the quarrel may arise—which Heaven forbid—and then it will be remembered that more than once our fleet has cruised there, even anchoring in Lerwick Harbour, and taking soundings of every fathom of the waterway, until our officers know it better than the men of the British navy. So, we have not been idle, and even now that these manoeuvres are to be secret, are there not ways—"

The Kaiser stopped abruptly, and pulled at his moustache. A sudden doubtful light had come into his eyes, and he stood like a man who fears that he has committed himself. Then he sat down, leaving his sentence unfinished, and began to discuss the affairs of the regiment with Colonel von Harmann.

"KAISER'S STRANGE SPEECH!"

Everywhere in London the newsboys were shouting it out, and Londoners, with memories of other speeches, were buying the papers eagerly.

Somehow, most of the details of the German Emperor's speech had leaked out, and for the first time Britishers were realising why the manoeuvres were to take place in the North. Some, strong in geography, were pointing out how easily a hostile fleet could pass from the Shetlands to the Atlantic, and so to the unguarded Western coast.

"Why don't the Admiralty think of these things?" men asked each other.

As a matter of fact, the report of the speech had sent ugly thoughts into the brain of more than one man responsible for the safeguarding of Great Britain, and into none more than that of the Prime Minister himself. He had already taken action, and now he was pacing his study in Downing Street, waiting for the arrival of Mr. Henry Kennard, Chief Lord of the Admiralty.

Time after time he paced the room, a look of worry on his face—the face which, save for the white hair above it, was that of practically a young man. And from time to time he paused by a great map of England that had evidently just been hung on one of the walls, and his white, rather nervous finger traced a track from the Shetlands round to the western coast.

"Mr. Kennard!" a footman announced, and a man of medium height, with a thin, keen face, walked briskly into the room. He was in evening-dress, and the black clothes made him look slimmer and younger than he really was.

"I am glad you have come," the Prime Minister said eagerly.

"This speech?" Mr. Kennard queried, as he coolly seated himself and took a cigar from the open box on the table.

"Yes." The Prime Minister had ceased to pace the room, but he did not seat himself. "Since the report of that speech came through I have learnt some unpleasant things. It is only too true that the Germans know the Shetlands and Lerwick better than we do, that both by land and sea they have made a most thorough examination of the part."

"You believe in the speech, then?" Mr. Kennard asked quietly.

"Yes." The Prime Minister spoke as a man who is utterly and entirely convinced. "That there is actual danger from Germany just now I do not fear. The countries are friendly, and even if they were not the business that they do with us is too important to be shattered by a war. So far peace pays them, but we must not forget that some day it may cease to do so, and then—"

"And then?" Mr. Kennard echoed.

The Prime Minister was standing in front of the map again.

"We shall know what fools we have been unless we act quickly," he answered.

Mr. Kennard started, and removed the cigar from between his lips. The line that was cut between his eyes had suddenly become deep and black, and the well-marked eyebrows nearly met above it.

"You have a plan," he said shortly, stating a fact, not asking a question.

"Yes."

"What is it?"

Before the Prime Minister could answer, the footman had entered again.

"Mr. Sexton Blake to see you, sir," he announced.

Mr. Kennard rose sharply from his chair, took the Prime Minister by the arm, and led him to the window.

"This is the famous detective?" he asked, in a whisper.

"Yes."

"But surely you are not going to allow him to dabble in affairs of State?" Mr. Kennard objected.

The Prime Minister shrugged his shoulders a trifle wearily, and his eyes roamed back to the map.

"Who else is there?" he answered.

"The secret service agents," Mr. Kennard said sharply.

The Prime Minister turned sharply, and there was that in the expression of his face which showed that his mind was fully made up. Men who knew him well, colleagues in the Cabinet, were aware that when that look came into his eyes that there was no turning him from his purpose.

"This is no case for them," he said, in a low voice. "They are clever men, some of the best in England, but for this task we must have the best, and this Sexton Blake is acknowledged to be that."

"And suppose I refuse to let him dabble with my department?" Mr. Kennard queried a trifle sharply.

"Then I shall act on my own account," the Prime Minister assured him. "You cannot prevent an agent of mine going to the Shetlands." He turned to the waiting footman. "Show Mr. Blake in here," he ordered.

A few seconds later Sexton Blake entered the room. Over his evening-clothes he wore a heavy motor-coat.

"I am sorry I am late," he said quietly; "but I was engaged in a case at Somerset when your message came. My assistant 'phoned me, and I motored up."

"It was very good of you to come so promptly," the Prime Minister said. "Perhaps you can guess what the trouble is?"

Sexton Blake smiled, nodded at Mr. Kennard, and then crossed to the map on the wall.

"There is the trace of where a finger has passed more than once from the Shetlands to the Western coast," he said quietly. "Adding that to the fact that Mr. Kennard is here, I can surely suggest that I am wanted with regard to this speech of the Kaiser's."

"Yes," the Prime Minister assented eagerly. "Do you think there is anything in it?"

"Yes."

Mr. Kennard smiled cynically, and put down the butt of his cigar.

"Surely—you will pardon the seeming rudeness—there is no reason why you should be the judge of that?" he said.

"I fancy there is," Sexton Blake answered coolly. "I have the pleasure of knowing the Kaiser—having worked both for and against him—and I can assure you that even his wildest speeches have truth in them—a good foundation of truth."

He turned to the Prime Minister.

"There is no need to beat about the bush," he said. "You wish me to find out how far the Germans have gone, and whether they are even watching these manoeuvres?"

Just for a second the Prime Minister hesitated; then he nodded.

"If you are willing," he agreed.

"I can start tonight," the great detective said simply.

"And we have your word that everything you discover, or see, you will keep secret?" Mr. Kennard put in sharply.

Sexton Blake drew himself up with a touch of haughtiness.

"You are at liberty to send someone else!" he answered.

"Tush, man! We mustn't quibble over a word," Mr. Kennard said quickly. "You would go alone?"

"No!" Sexton Blake answered. "I shall take one man with me, and my young assistant."

"They are to be trusted?"

"As myself," Sexton Blake said quietly. "I will be going. There is no time to be lost."

"And as regards fee," the Prime Minister put in, "why—"

Sexton Blake raised a hand sharply.

"I do not think there is any need to discuss that," he said, with a touch of pride. "I would willingly undertake this task for nothing—I am patriotic enough for that. Anyway, there will be time enough when I have finished to settle such matters."

By the door the great detective paused.

"You will hear from me day by day," he said quietly—"unless matters prove so serious that I dare not trust them to the wires. Good-night!"

The door closed behind Sexton Blake, and Mr. Kennard picked up a fresh cigar and lit it.

"A self-reliant man," he remarked.

"The only man in Britain for this task!" the Prime Minister answered, with conviction.

Sexton Blake stepped into his waiting motor, and as it drove away he lit up a cigar. There was nothing in the expression of his face to show that he was returning home to make preparations for commencing on one of the biggest cases of his life—a case that involved the security of a great nation.

In the Shetlands—The Whirr From Above—

The Trailing Rope—Aboard the Airship.

THE wind came strongly from the sea, so that the two men and the boy who stood looking out across the water had to bend forward to keep their balance. They were standing on a rocky promontory, of which there are many in the Shetland Islands. To their right, the lights of the town of Lerwick lay, but beyond that everything was dark.

From below, came the snapping of the waves as they spent themselves against the rocks.

"Don't believe Fleet here at all," Inspector Spearing, of Scotland Yard, who was the shorter and broader of the two men, jerked impatiently. "No lights, no whistles, no anything!"

Sexton Blake laughed, and turned his back to the wind while he lit his pipe. He had lost no time in setting out on his mission; and Spearing, after some difficulty in the way of obtaining leave without giving the exact reason for it, had come with him.

Sexton Blake had thought of him the moment the Prime Minister had asked him to undertake the work, for he knew well the splendid qualities of dogged pluck that the worthy official of Scotland Yard possessed. True, such qualities might not be required; yet Sexton Blake had a strong impression that they would be.

For years it had been common knowledge with him—there were few things escaped him—that the Germans had more than once cast eyes upon the Shetlands, and he did not think it probable that these manoeuvres would be allowed to take place without them knowing as much as possible about them.

"What's that, sir?" Tinker asked sharply, pointing seawards.

Sexton Blake shaded his eyes with his hand, and stared out into the darkness. There was not a star in the sky, and beyond the rocks on which the men stood everything was dark as a pit. Only the breaking waves told how near the water was.

A speck of light shone out—but how far away it was impossible to tell—winked, and vanished. Then a second one—away to the left—leapt into existence, and began to flash and blink at a tremendous rate.

"Warships—signalling, my lad," Sexton Blake said quietly. "If it's a general order from the flagship, you'll see more lights in a minute. Ah, there they go!"

Suddenly, right out in the darkness, fully a hundred bright, blinking lights had leapt into life, evidently answering the first one that had appeared, and the sea that had been so dark seemed to be illuminated by powerful stars.

"Is the Fleet there?" Sexton Blake queried, turning to Spearing, with a laugh.

"Don't know!" the worthy official growled, not willing to admit himself wrong. "Fool's game, anyway! Don't believe understand each other's signals!"

The lights went out as quickly as they had come, but only for a second did the sea slip back into darkness. Then, from a hundred different places, great flashlights glared out, dazzlingly white, and played upon the rocky coast.

A few fell upon the harbour itself, revealing the masses of shipping lying there—the hundreds of drifters and trawlers that make Lerwick one of the most important fishing centres of the world. But most of the lights played upon the barren rocks, and one, flashing a trifle upwards, shone full upon the detectives as they stood on the rocks. They were compelled to turn their heads, the light was so dazzling.

"Give in!" Spearing snapped. "Fleet there, sure enough!"

Now the lights swung away from the shore, and flashed around the sea in great circles. From place to place they slipped, and every time they moved their rays were broken by the great turrets of battleships, by the four straight funnels of the first-class cruisers, by the low-lying, waspish looking torpedo craft that seemed to fairly swarm round the larger vessels.

Sexton Blake drew his breath in sharply.

"A sight like that makes you believe that we do really boss the sea," he said, in a low tone.

For more than half an hour the lights swung round slowly, then rapidly, resting on certain places on the land, as if trying to wrest the very secrets of Nature from the rocks.

And they went out, leaving the night darker than before, and not even the twinkling of a riding light showed where the great Fleet lay. Possibly they had steamed away; maybe they still lay at anchor. There was nothing to give an answer.

"Getting hungry!" Spearing growled, rubbing his eyes to get the departed glare out of them. "Time for supper. Hungry—very!"

"All right; you get along with Tinker," Sexton Blake answered. "I shall stop here and finish my pipe."

"Can't I stay, too, sir?" the boy asked eagerly.

"No. There is nothing to stay for."

Sexton Blake was left alone on the rocks, and he seated himself—knees drawn up, elbows on them, pipe between his teeth—and stared out to sea. He was trying to think in what manner the Germans could—

The detective sniffed sharply, tapped the ashes from his pipe, put his foot on them—and sniffed again.

"Petrol!" he muttered, and stood staring round. "Yet there can't be a car round here. No roads worth speaking about."

But the smell of petrol, faint but pungent, was in the air right enough, and as the seconds passed it seemed to be growing stronger. For a moment the detective thought of motor-boats, but quickly put that idea away from him. He knew that the Fleet did not carry them, and that the searchlights would quickly have picked out anything of that kind had it been on the water.

Whi-r-r-r!

It was a curious sound—not unlike that made by a revolving air fan—and Sexton Blake looked round sharply as it reached his ears. The wind was light and variable now, so that it was difficult to judge from what direction it came.

Whi-r-r-r! The sound came nearer, and was followed by a small but distinct explosion.

"The exhaust of a motor!" Sexton Blake muttered; and again his eyes searched the darkness.

He remembered that there had apparently been nothing but a very rocky footpath up to the spot on which he was standing, so how was it possible for a motor-car to be coming in that direction? Yet, unless his usually keen ears were playing him false, one was certainly approaching.

A rope struck sharply across his face, and mechanically he gripped it. It swung him off his feet, clear of the rocks, and so out over the breaking waves. Then, for the first time, he knew that the whirring noise came from something dark and huge that hovered above him in the air. From there also came the faint smell of petrol.

With the instinct of self-preservation, Sexton Blake pulled up the slack of the rope that hung beneath him, and hitched it around his chest, so that the strain of holding it was no longer on his hands. It was the work of a few seconds only; then he turned his eyes upwards.

In the darkness of the night it was possible to see nothing more than a patch that loomed darker than the sky, and to hear very faintly the thudding of a motor. This last noise was so slight that another hundred yards would have made it inaudible.

Sexton Blake knew, as he swung out over the waves, that he was hanging on to the trail-rope of an airship or dirigible balloon, which had come from somewhere inland, and was now stealing out to where the Fleet lay, if it had not sailed to execute some manoeuvre.

Was it a hostile craft? Sexton Blake caught his breath sharply as the thought occurred to him. It might be one of the British airships from Aldershot; but it might just as easily be one of the foreign ones that had lately met with much success. If the tales about their flights were true, they might easily have flown a long way on a dark night like this—secretly and unobserved.

And for what purpose?

Until now the sound of breaking waves had come clearly to Sexton Blake's ears; but they began to die away, and he knew that the airship, whatever her nationality, was rising rapidly. This certainly looked as if she wished to escape observation, and to be out of the range of the searchlights should they flash out again.

A dash of sand, ballast from the strange craft above him, struck the detective's face, and as it did so a terrible thought came into his mind.

Suppose some hostile power had been waiting for such time as this, a moment when most of Great Britain's magnificent Fleet lay within a small space, to drop deadly melinite bombs, or some equally death-dealing and destructive explosive among them?

Sexton Blake felt as if his heart had stopped beating, and for the briefest fraction of a second the trail-rope nearly slipped from him. Then his grip tightened, and he resolved that whatever the risk to himself he had got to discover what nationality the men were who were controlling the airship that swayed along above his head.

No sooner was Sexton Blake's mind made up than he was ready to act. By keeping the rope hitched under his arms, and holding it in place with his teeth, he contrived to get his hands free, and set to work to drag off his boots and socks, which he let fall into the sea. That accomplished, the really arduous part of his task commenced.

Hand over hand, using his bare feet to grip with, so as to take some of the strain off his arms, Sexton Blake clambered upwards. He knew that the climb before him was most probably one of three hundred feet or more, enough to make the strongest and most determined man hesitate; but he reckoned that by resting frequently he would be able to accomplish it.

Sixty feet he covered, until he was panting for breath. A hitch of the rope under his arms and across his chest, and he hung resting in a natural swing. Only a minute, then on again, upwards over another sixty feet of swaying rope.

All the time he kept his eyes turned upwards, and with every foot he covered he began to see more plainly the airship that lay above him. At first it had been nothing but a darker blotch in a dark night, but now it was beginning to take shape and form. He could see the long balloon, narrow at one end, broadening out at the other—much the shape of a bottle-nosed shark.

From the narrower end something like a tail protruded, and there were projections, not unlike fins, half-way along the body. Below the body lay a long canvas car, capable of holding at least a dozen men, and it seemed to Sexton Blake that the airship was large enough to be capable of lifting that number.

Up again, another rest, on once more, until every line of the airship was visible to the detective's eyes. He recognised the pattern then. It was like the Zeppelin, so recently purchased by Germany, but built on a much larger scale. Only a short time back he had made a journey abroad specially to see the airship about which so much had been written, and so he could make no mistake now, even though this craft of the air was fully twice as large as the one he had previously seen.

Ay, Sexton Blake knew now that this ship was no Nulli Secundus[*], but the airship of a rival—if not mildly hostile—country, and he hesitated as to whether he should continue his climb, or slide down the rope and hang there until a chance of escaping either by sea or land presented itself to him.

[*] Nulli Secundus ("Second to none") was Britain's first powered military airship. Officially British Army Dirigible No 1, she was launched on 10 September 1907. A month later, while she was moored, high winds posed such a danger that she was dismantled and later rebuilt as Nulli Secundus II.

He looked down, and as he did so the flashlights of the ships of war stretched out their great arms of light again, and he realised what a distance he was up, that no one aboard the ships could possibly catch so much as a glimpse of the airship.

His mind was made up. He would learn more fully what the men above him were doing. Probably he would be captured, but there were ways of escape, and—

Sexton Blake started to climb upwards again, resting as before, until his fingers gripped the thin aluminium rails that formed the bottom of the car of the airship. He raised himself still higher, gripped the edge of the car, and pulled himself upwards.

A startled, angry cry in German reached his ears, powerful hands gripped him, and he was dragged into the car.

The car swayed violently as the detective was hoisted into it, and a voice from the forward end of it, a voice that Sexton Blake seemed to recognise, called out for them to be more careful.

Ten men were in the car, not counting the one who was steering and the one who was controlling the engines.

They came crowding forward now, all save one, who remained in the front of the car, a military cloak drawn tightly round him.

"Who is the spy?" this man demanded, in German.

And again Sexton Blake fancied that he had heard the sharp, commanding tones of the voice before.

A big man, with a certain tone of authority, faced the detective, as the latter clambered to his feet.

"How did you get here?" he growled.

Sexton Blake smiled coolly, and waved a hand to where the guide-rope trailed down.

"By that," he answered.

"Yes," the German agreed, thrusting his face closer. "But why did you do it?"

"Not for fun, I can assure you," Sexton Blake replied, holding up his hands to show how the climb had torn the skin on them. "I was standing on the edge of the cliffs when your rope struck me. I had to grip it to save myself from being flung over into the sea. And then—why, what else could I do but clamber up?"

"So?" the German growled doubtfully.

"That is the truth?" the man in the bows demanded.

"Why, yes, your Majesty!" Sexton Blake answered.

A sharp cry broke from the man in the bows, and he flung his cloak from him with an impatient gesture.

"How do you know me?" he asked sharply.

"Yours is a voice to remember, sire!" the detective answered coolly.

The man in the bows rose and came forward along the swinging car, and even in the darkness it was possible to make out the martial visage and upturned moustache of one of the greatest rulers that Germany has ever known—Wilhelm II.

The man in the bows rose and came forward along the swinging

car, and even in the darkness it was possible to make out the

martial visage and upturned moustache of the Kaiser.

"Who are you?" he asked sternly.

Sexton Blake bowed, and there was a hard little smile on his lips.

"Once I worked for your Majesty," he answered, "twice—the regret is mine—against you."[*]

[*] This is a reference to earlier Union Jack stories.

"Sexton Blake!" the Kaiser ejaculated.

"Precisely," the detective agreed; "and I am sorry that I cannot add, at your service!"

The Escape—The Airship Makes a Search—

Inland Before the Dawn—The Hiding Place Among the Rocks.

ONE of the greatest manoeuvres that the British Fleet had ever made was in progress, the utmost secrecy being kept with regard to it, not a single man, save the officers and crews, being allowed aboard the ships of war, though previously guests had been permitted to be aboard.

Yet over the Fleet, though hidden by the night, hung the airship of a great foreign Power that for years had been building a navy that was to rival the one that lay off the Shetlands—a Power that by land had for many years been Great Britain's superior, and which now was doing its utmost to add to that its superiority by sea as well.

And on board this airship was none other than the ruler of this nation—the Kaiser Wilhelm himself.

As the latter stood pulling at his moustache, his keen eyes on Sexton Blake, he had much the look of a naughty boy caught robbing an orchard. His blue eyes held a doubting look, and more than once he stopped when about to speak.

"It is well it is you, Mr. Blake!" he said at last. "If it had been another man—" He shrugged his shoulders, and explained no further. "I admire such men as yourself—men who have in their time even dared to thwart my will."

Sexton Blake smiled. He knew, as well as anyone living, that the Kaiser's great fault was his entire belief in his divine rights as a ruler.

"I consider myself honoured, sire," he answered.

The Kaiser hesitated, then took the detective by the arm and led him to the forward end of the cage, where no one would be able to overhear them if they spoke in a subdued tone. He took a stool, and motioned the detective to take another.

There was silence for some minutes, during which time Sexton Blake saw that the great airship was hovering almost motionless over the Fleet, and it was the Kaiser who broke it.

"You wonder why I am here?" he said abruptly.

"No," Sexton Blake answered, with a smile; "I know!"

"You think it is to spy upon these manoeuvres?" the Kaiser continued sharply.

"The word spy is a hard one to apply to your Majesty," Sexton Blake objected.

"But the right one—so?" the Kaiser persisted, tugging at his moustache. "This is no time to mince words, Herr, but to make terms. For the first, let me explain why I am really here."

Sexton Blake bowed, and his face became positively wooden in expression. He did not know what the Kaiser was going to tell him, but he did know that it would be wise to appear not to doubt it.

"I am here"—the Kaiser spoke slowly, and his eyes met the detective's unflinchingly—"more by chance than anything else. For nearly a year back this airship has been building secretly, and as soon she was completed, nothing could satisfy me but that I myself test her merits. So I embarked on her. That we headed here was natural."

Sexton Blake bowed, but made no answer. Inwardly he thought that some of the explanation was true—some.

"For the rest"—the Kaiser spoke with a lightness that he obviously did not feel—"there is the question of your silence."

"Yes?" the detective murmured.

The Kaiser was tugging at his moustache again, for he knew that in Sexton Blake he was dealing with no ordinary man.

"It will be awkward, cause bad feeling, if it is known what has happened," the Kaiser went on. "You can see that I have done no harm; but even then I would like to show my high esteem for you by offering some little present."

"Your Majesty was always a diplomat," Sexton Blake murmured. "I have never had a bribe offered me in such nice terms!"

"Bribe?" The Kaiser's face flushed. "I am offering you a present!"

"I apologise, sire," Sexton Blake answered; "but I never accept presents from rulers of foreign nations in cases like this!"

The Kaiser sat silently twisting his moustache, and from time to time glancing inquiringly at the detective.

"Very well," he said at last; "there are other ways of getting your silence—without buying it!"

The Kaiser moved back to where the man sat working the petrol-engine, and Sexton Blake was alone. He sat still in the bows of the car, trying to see down to the ships that lay below, but only an occasional flashing signal told him where they were. All the time, too, he listened for anything that the Germans might let drop, but heard nothing of importance.

The airship hung almost motionless, and it was not until one in the morning that she began to move back towards the shore, Sexton Blake judging the direction she was taking from the wind.

Then he looked down, and saw lights moving out to sea. The warships were outward bound on some manoeuvre. But he had more than that to occupy his brain, for he wanted to know what had really brought the Kaiser to the Shetlands, how they had managed to keep the presence of the great airship secret, and just how much had already been done to make the islands a naval base for the German Fleet should it ever be required.

Of one thing Sexton Blake was certain, and that was that at the first moment he would have to escape. What he would do after that there was plenty of time to decide.

Back towards the land the great airship was travelling at a steady pace, her screw hardly turning, the wind carrying her along; and as she drew nearer she sank lower, the men in charge evidently wishing to be able to sight some particular spot.

This gave Sexton Blake hope, and from time to time he glanced over the side of the car to see how far she hovered above the water.

A hundred feet below the water showed darkly, and as that height was reached two of the Germans came towards Sexton Blake, a coil of stout cord in their hands. As they approached, Sexton Blake rose to his feet. He knew what the rope was for—to make him a prisoner—and he was not taking anything of that kind just yet.

"You will make no resistance," the nearest of the Germans growled. "Even a brave man knows when defeat is his."

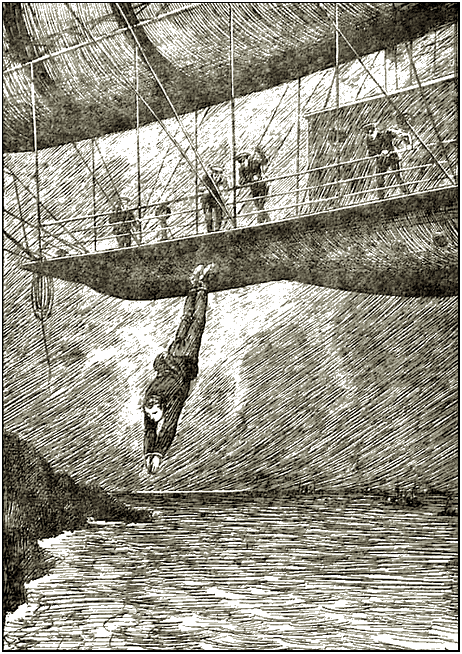

Then once again Sexton Blake glanced over the side of the car, and this time he saw that the water was no more than eighty feet below him. Without hesitation he gripped a rope, and leapt to the side of the car. On the rail he balanced himself, and, with sharp cries, the Germans rushed at him.

Too late! Cleanly, as dexterously as if there had been no hurry whatever, Sexton Blake dived, and went flashing down towards the water. It was an ugly job, but he was an accomplished diver, and had no fear of it. Besides, he was not a man accustomed to worrying about his own safety when the well-being of Great Britain was at stake.

Without hesitation, Sexton Blake leapt to the side of the airship and

balanced himself on the rail. The two Germans rushed him. Too late!

Sexton Blake dived, and went flashing down towards the water.

Almost without a splash he struck the water, and a few seconds later was on the surface. That the airship carried a searchlight he had no doubt; but he also knew that they dared not use it for fear of attracting attention. A bullet might bring them down, then it would mean the discovery of the Kaiser aboard.

A cause for war almost, and that before Germany had built the Navy that she was planning.

As Sexton Blake merely kept himself afloat, he looked upwards, and saw the airship coming down towards the surface; also he could hear excited orders being given in the Kaiser's voice, and he knew that he was not to be allowed to get away so easily.

Within a couple of feet of the water the car of the airship descended, and with the screw going slowly she began to make a search of the waves. Twice she passed close to the detective, but each time he dived, and kept below the water as long as his lungs would permit him.

Round and round went the airship in narrowing circles, and it seemed to Sexton Blake that his recapture could only be a matter of time. The diving below the water was tiring him, too, and he knew that he could not do it many times more.

Again the airship swung her blunt nose round towards him, and in the darkness he saw her coming. Below the surface he dived, and stopped there until his chest felt like bursting.

With a spring he came to the surface, and caught his breath hard as he shook the water from his eyes, and found the car of the airship right above him. Then his hand shot out, and he gripped the aluminium rods.

"Throw out ballast; she dips too low!" he heard a voice cry as his weight bore the car down lower towards the waves, until his head went beneath them, in fact, and then the car shot higher, dragging him with it.

Gently, inch by inch, Sexton Blake dragged himself up and wriggled his body between the lower supports of the car, which were about a foot below the ones on which the car actually rested, and lay there at full length.

Then he smiled, for he reckoned that he was going to learn many things. First he would discover where the airship had been hiding inland; secondly, he would know for what purpose the airship was visiting the shipments, but of the extent of that knowledge there was no guessing.

The airship still continued to hover round, sweeping the sea in search of the man who had leapt overboard; and little did the men aboard of her imagine that he was lying more or less comfortably under the car itself.

"Must be drowned, the dog!" a guttural voice said from above. "We must get inland before the dawn."

"No brave man is a dog!" the voice of the Kaiser answered, a touch of anger in it. "I tell you, I would have given much, Harmann, for a few men like Sexton Blake in Germany."

Ballast splashed into the water, and the airship rose rapidly and shot away towards the land, her propeller doing well over a thousand revolutions a minute.

There was certainly not much time to lose if the airship had to go far inland before the dawn. Sexton Blake endeavoured to turn round to see where they were going, but found it impossible, the space in which he lay being too small to move in.

Soon, however, he knew that the land had been reached, for the sound of the waves no longer came from below.

"Stop! We are there!"

As the order rang out, Sexton Blake wriggled his legs down from his perch, and his feet grated along a rough surface. Without hesitation he let go, and fell flat onto his face. Glancing upwards, he saw the great airship looming up only a few yards away, and heard the clank of a grapnel as it struck the ground.

Noiselessly he crawled along the rocky ground, round behind a boulder, and lay still. There would soon be something startling to report to the men who had feared, after reading the Kaiser's speech, for the safety of the Shetlands.

A Change of Identity—The Cave by the Shore—

What Is inside?—The Truth.

LYING behind the boulder, Sexton Blake heard the Germans embark, while Colonel von Harmann gave orders in his deep, decisive voice. He appeared to be in supreme command of the great ship and the detective remembered the many rumours he had heard with regard to the control this officer exercised over his Royal master.

At present the detective could not make the slightest guess at where he was, and even by daylight it would be difficult for him to place the spot where the airship lay, for he knew little or nothing of the Shetlands.

It seemed to him, however, that probably they were on one of the smaller islands, which are nothing more than masses of rocks, and which year in and year out are only visited by sea-birds, save when some good ship, driven there by the storm, flings onto the merciless rocks the bodies of brave men. A few of these survive—very few.

By now the grey in the sky had spread, and over to the eastward it held the look of morning. A faint pink hue had joined the grey, and for a time Sexton Blake wondered why the bottom of the sheet of colour was cut off so abruptly. Later he learnt the truth.

An hour passed, and during that time the Germans had worked on without pause. Then all movement ceased, and the men seemed to have retired. A smell of gas reached the detective's nose, and he wondered where it came from, unless the balloon was being emptied. Later, by the aid of chemicals, it would not be difficult to refill it.

So day dawned, and as Sexton Blake's eyes grew accustomed to the dim light he saw much to marvel at, and also much that he had already surmised.

All around him rose high rocks, and he saw that the spot where the airship had landed was entirely surrounded by these, so that she lay in a kind of pit. Not that she would have been noticed much by anyone passing, for the great gasbag had been emptied and stowed somewhere, though the detective could not see where.

The car, with all its complicated machinery, had been pushed on a trolley into a long wooden barn, the sides and walls of which were literally covered by boulders. Beside this building was a smaller one.

All these things Sexton Blake saw, and wondered at the laxity of a Government that had allowed a rival nation to explore these wild islands, and to leave them so unguarded that they had practically already taken possession of one of them.

He smiled as he thought of the surprise that his report would cause, and he meant to take steps to nullify these preparations that must have been going on for years.

While these thoughts were in Sexton Blake's head, the Germans came out of the shed in which they had packed the car. First came the Kaiser, more unmistakable than ever in the light of day, talking eagerly to Colonel von Harmann. Behind him followed the rest of the men, and Sexton Blake started and peered forward eagerly as he caught sight of one of them.

The man was his own height, the rather pale, clean-shaven face, adorned only by a small moustache, was not unlike his own.

"If he is here till the night, I fancy we shall change places," the detective muttered.

The sight of this man had put an idea into his head. It was a daring one, but he was used to such things. Capture might mean anything, even death, if the Kaiser were not there to interfere.

As soon as the Germans had entered the building, which was obviously a kind of living place, Sexton Blake drew a small tin box from his pocket, produced a mirror from it, and propped it up against a stone. Then, by the aid of an eyebrow pencil, he altered his eyes the veriest trifle, and cut a small but beautifully made false moustache into the shape worn by the German officer. This he fastened, then looked closely at himself in the glass.

"As far as I can see, there is no difference," he mused, "and to-night I may have a chance of comparing it with the original."

That the Kaiser would not attempt to leave save by night Sexton Blake had no fear, for there would be too much chance of him being recognised, especially as a keen but quiet watch was being kept in all the towns for foreigners while the secret manoeuvres were on.

During the next hour Sexton Blake lay behind the boulder, fervently hoping that no one would come in that direction and discover him, and at the end of that time a stroke of luck came his way that helped him considerably.

The German he had marked out emerged from the smaller of the buildings, stood uncertainly with a pair of heavy field-glasses in his hands, then started off briskly across the rocks. Within six yards of Sexton Blake he passed, but the boulder held its secret.

The detective had thought to have to wait for the night before putting his daring plan into execution, but his chance had come much earlier.

He glanced at the building where the officers were, and saw that the door was tight closed. True, someone might be watching from a loophole, but he risked that. Turning, he crawled along in the direction that the German had taken, moving from boulder to boulder, only raising his head from time to time to make sure of the direction his quarry had taken. This was not difficult, for the man was making for one of the highest points of the rock, and so was easy to keep in sight.

Higher and higher the detective climbed, glancing back to make sure that he could not be seen from the hut, and at last stopped, lying flat on the rocks, with the sea stretching out in front of him. Nowhere could he see the German, and he had time to glance round and take his bearings.

Where he lay he could command practically the whole of the little island—for that it was—and he saw that it lacked absolutely any sign of life or vegetation. It was just a clump of rocks that looked as if they had been piled unceremoniously upon each other; and not three miles away lay Lerwick, the roofs plainly discernible in the sunshine.

Now came the most dangerous part of Sexton Blake's mission—the finding of the German whom he meant to impersonate.

He looked round searchingly, without daring to raise himself from the ground, and his keen eyes soon caught sight of a boot sticking out from behind a rock that lay a matter of thirty yards distant.

More cautiously than ever, and with all the cunning of an Indian, the detective crawled in that direction, and reached the rock. Within a yard of him the boot stuck out, and from the way it occasionally moved the detective could see that the German was shifting his position, so as to get a better view of the sea.

Sexton Blake shifted a few inches nearer, and hesitated. A new plan had suggested itself to him, and though it was risky, it promised well of success. He stretched out his hand until the fingers hovered over the boot, then they clutched it, and he heaved at it with all his strength.

A smothered oath came from behind the boulder, but before it could be repeated in a louder tone Sexton Blake had darted round the rock, and was kneeling on the German. The latter, taken by surprise, made no effort to keep the detective's grip from his throat, but once the fingers had closed on it, he struggled wildly.

Right on the edge of the rocks, with a drop of fully a hundred feet to the jagged stones below in front of them, the two men fought; but Sexton Blake had started with an advantage, and he kept it. Gradually he wore his enemy's strength down, half-choking him, until he lay still. Then, using only his left hand, keeping the other on the German's throat, he released the belt from his waist, and managed to jerk it tight round the other's wrists.

The rest was easy, and within five minutes the German lay bound and gagged, his own belt fastening his ankles.

Sexton Blake stood looking down at the helpless man, and a little smile played around his lips.

"I fancy you will be safe," he said in German. "I must apologise for treating you in this manner, but must point out to you that trespassers are always liable to little troubles like this."

The German, who was rapidly recovering, turned purple with his efforts to free himself or speak, both of which were in vain.

Looking round, Sexton Blake discovered a nook between two boulders, and into this he carried the man. Then he rolled other boulders up—heavy ones that he was only just able to move—so that the man lay in a pit from which, in his helpless state, it would be quite impossible for him to escape.

By the aid of his pocket-mirror Sexton Blake compared his make-up with the face of the German, and slightly altered his moustache. Next, he turned his attention to the clothes, and saw that the man was wearing a blue lounge-suit, which might have been a brother of his own. Only the collar and tie were different, and these he quickly appropriated and donned.

"Again I must ask you to pardon a liberty," he said pleasantly; and thrust a hand into the man's pocket, and pulled out some letters.

All of them were addressed to Lieutenant Bergern, and the detective returned them after noting that fact. Then, with the man's field-glasses swinging from his hand, he calmly turned and strode down the rocks.

His heart was beating a trifle faster than usual. Perhaps it was because of the struggle that he had just had. Perhaps because he was about to walk calmly into the hands of the Kaiser and his officers, trusting to pass as Lieutenant Bergern.

Down over the rocks he went, and there was not even the slightest sign of hesitation in his manner when he caught sight of the Germans gathered outside the hut.

"Hurry!" Colonel von Harmann cried sharply.

Sexton Blake quickened his pace, and saluted in true German fashion as he joined the group.

Not one of the party looked at him suspiciously.

"There is nothing in sight, Lieutenant?" the Kaiser demanded. "No boats coming towards here?"

"Nothing, your Majesty," the detective answered.

"Himmel!" the Kaiser said, ejaculating angrily. "Please to remember that I am now Colonel Kelner!"

"Nothing, Colonel!" Sexton Blake said, thankful that his slip had aroused no suspicion. Of his German he had no fear, for he spoke the language like a native.

The Kaiser turned to Colonel von Harmann a trifle impatiently.

"We will see this cave!" he ordered.

"I am ready!" Colonel von Harmann answered; and turned and gave instructions to six of the others, stationing them at various points along the rocks.

As each one started off to his allotted place, Sexton Blake's heart seemed to stand still for a second, for if one was sent to where the real Lieutenant Bergern lay a prisoner, all would be over. But the six left, not one going to that spot, and the detective breathed freely again.

"Surely there is no need for all this?" the Kaiser said a trifle irritably.

"There is every need," Colonel von Harmann answered respectfully. "It matters nothing to me if I be captured, all my comrades in arms; but think what it would mean if those Britishers laid hands on you. You would be the laughing-stock of the world—"

"They would not dare!" the Kaiser muttered fiercely.

"Or Britain might take your actions as a cause for war," the colonel continued impressively.

The anger died out of the Kaiser's eyes, and he looked round uneasily.

"Yes, yes!" he agreed. "We must not give them excuse. So far there need be no war or rumour of war. I am not here to force trouble and expense of fighting on my country, but to make sure of victory should such an occasion arise."

"Let us go to the cave."

Sexton Blake knew now practically all that he desired to know, and he had information enough to startle even the Prime Minister. Nevertheless, he had no intention of getting back to London yet, even if he could escape, for there was more for him to learn. He already knew that the Germans had made their preparations for turning the Shetlands into a naval base should the time for war with Great Britain ever arise, and he meant to discover just what those preparations were, so that they could be made valueless.

Colonel von Harmann turned and led the way from the spot, Sexton Blake and the Germans not on guard going with him. The detective was more than a little relieved to find that no one suspected him in the slightest. In fact he had only one fear now, and that was that Spearing and Tinker would roam around the islands in search of him, strike this one, and be captured.

For three or four hundred yards the little party walked briskly over the rocky ground, and entered a narrow defile. Down this they went, stopping eventually right on the edge of the water, the waves breaking ten or fifteen feet below them. From here Lerwick, and much of the surrounding sea, could be plainly seen.

"A good spot to watch from," the Kaiser said thoughtfully. "It is well chosen."

Colonel von Harmann smiled, and tugged at a boulder that lay on his right. It came away with surprising ease, revealing an opening four feet high and three broad. To some extent this was obviously natural, but chisel-marks showed where it had been enlarged.

"You will go in?" the colonel queried.

For answer the Kaiser stooped, and entered the cave, the colonel close behind him.

Sexton Blake calmly made a move to follow, but a German gripped him by the arm and held him back.

"You forget that it is not permitted, comrade!" he said sharply. "The secret of the cave is for the colonel only—and the Kaiser!"

Sexton Blake muttered something unintelligible, and drew back, realising that he had very nearly made a fatal mistake.

Twenty minutes passed, and when the Kaiser emerged there was a smile of satisfaction on his face.

"It is good—very good!" Sexton Blake heard him say to Colonel von Harmann.

"What lay within the cave?" the detective asked himself.

THE rain came down steadily, and save for the noise of the heavy drops splashing on the rocks, and the faint rumble of the sea, there was no sound on the little island of which the Germans had taken such complete possession, yet Sexton Blake paused every few feet as he moved along in the darkness. An hour back he had taken his turn at watching from the rocks, and that had given him his opportunity of coming down to the cave that held the German's secret.

There was little risk that he would be discovered, but, nevertheless, he was taking the most minute precautions. When possible, he hid in the shadow of rocks, and every time he moved a foot he took care not to displace so much as a pebble. He was bound upon the accomplishment of a task that would probably mean much to Great Britain, and at such a time it was wise to avoid the smallest risk.

Down into the cutting between the rocks he made his way, peering along it to make sure that the cave was not guarded. There was no one there, and he moved cautiously forward.

Outside the cave at last. With quick fingers Sexton Blake gripped the boulder as he had seen Colonel von Harmann do it, and it came away in his hands, evidently fixed on some cunningly concealed swivel, and before him lay the narrow, black entrance.

He stooped, his back bent nearly double, and passed in. Inch by inch he moved forward in the darkness, feeling his way with his hands, and before he had gone ten yards he found that the passage broadened out, and that the rock roof was high enough for him to stand upright. Then he drew from his pocket an electric-lamp, and switched it on.

For a moment the bright rays dazzled him, but as his eyes became accustomed to it he looked eagerly around.

Certainly there was not much to be seen.

The cave was fully forty feet square, and was fitted all around with shelves, on which stood dozens upon dozens of electric-accumulators. At the far end of the place stood a petrol-driven engine, obviously meant to generate the electricity with which the batteries were stored. In the centre of the cave was a table, and it was to this that Sexton Blake crossed.

Then the detective caught his breath sharply, for at the edge of the table a row of electric buttons protruded, each one bearing a number. The rest of the table was covered by a chart each part of which was marked by a number corresponding with one of the buttons.

What did it mean? Had the Germans laid mines all around the Shetlands? Could they, if they so willed it, blow the great fleet that was manoeuvring to pieces? What other explanation was there?

Carefully avoiding contact with the buttons, Sexton Blake seated himself in the chair that stood before the table, and examined the chart more closely. He looked for Lerwick Harbour, to see how that was marked, and saw to his amazement that there was no mark at all. He sought for other well-known channels and moorings, but in each case there were no numbers there. Then he turned to the parts that were numbered, and saw that they were places in the Shetlands which had certainly never been regarded as landing places or harbours.

Puzzled, unable to understand the meaning of it, Sexton Blake rose from the chair and commenced to make a closer examination of the cave. At first he could discover nothing more; but at last, right in the darkest corner, he found an opening concealed by some planks. Pulling these aside, he stepped boldly through, and found himself in a smaller cave, which had evidently been used as a store-house.

Lengths of rope, coils of cable, lay everywhere, but it was a pile of stuff in a corner that attracted Sexton Blake's attention, and he crossed to it. As he examined it a smile curled his lips, for at last he understood the use that the Germans had put the island to.

The thing that he examined was a length of cable, but the curious part was that at every twenty feet along it a powerful electric-bulb was fixed, this being shaded so that the light could only shine upwards.

It was a piece of cable such as had been designed by a certain Leon Dion for lighting ships into port. Instead of the old buoys, this cable with lights attached was sunk to the bottom, and laid along the navigable channel, then, when the lights were switched on from the shore, the lamps threw a bright glow up onto the surface of the water, and by following this, a ship was able to make port without the slightest trouble.

So far as Sexton Blake knew, this system had as yet not been adopted by any country, but it was obvious that the Germans had seen the advantage of it, and put it to a practical use.

How long they had been at work in the Shetlands the detective had no idea, but he did know that they had discovered fresh landing places, each of which had been marked on the chart fastened to the table, the entrance to them being marked by the sunken lights.

Yes; Germany had made her preparations well. She had ignored the regular ports, knowing how closely they would be guarded once there was a rumour of war in the air, and had found and marked fresh ports for herself.

Sexton Blake hesitated. Should he destroy these preparations? For five minutes he stood undecided, then a solution came to him. He would leave things as they were, and prove at the first opportunity, by a practical demonstration, the danger in which the Shetlands lay.

From his pocket Sexton Blake drew a sheet of paper and a pencil, and for the next hour he sat at the table and worked. When he at last rose and left the cabin, his pocket held a complete copy of the chart of the Germans.

Away From the Island—Pursued—

Spearing Arrives in Time.

CONFIDENT now in his disguise, which at present no one had suspected, Sexton Blake calmly made his way back to the centre of the island, the faint light that came from the living-hut being guide enough. He entered the place without hesitation, and stood in the presence of the Kaiser and Colonel von Harmann who were poring over papers. Both looked up as the detective entered.

"You are back early, lieutenant," the Kaiser said shortly.

"The night is dark," Sexton Blake answered, "and to look out to sea is to fix the eyes on a blank wall."

The detective crossed to the further end of the room, where a number of sleeping-bunks had been fixed up, and threw himself into one. Never in his life had he been in such an extraordinary position, and he meant to make the most of it. True, he had already learnt many things, but there were still others to learn.

Above all, did the Germans contemplate an attack on Great Britain, or were all these preparations merely—

"Five years, not a day less," the Kaiser said irritably, with the air of a man who has finally come to a conclusion that he did not wish to reach.

"I should say four—not a day more," Colonel von Harmann corrected. "You say, wait for these battleships that are building; but I say that there is no need. Has not our fleet been here before, so why should it not come again?"

The Kaiser rose from his seat and paced up and down the floor. When he stopped at the table again the moody expression had left his face, and he laughed.

"Why, so, Harmann," he said, "we speak as if we meant to attack Great Britain, while in reality all this is merely a precaution, a way of making our power felt should the occasion ever arise. I hope to heaven it never may!"

Sexton Blake's face was towards the wall, or the men must have seen the expression of relief that crossed it. At last he had heard what he had been so anxious to hear—that there was no real danger from Germany—for the present, at least.

Over by the table the Kaiser and Colonel von Harmann were examining their papers, and Sexton Blake, tired with all that he had been through, dropped off into a doze.

He awoke with angry cries in his ears, and he sat up sharply in his bunk, his hand dropping to the pocket in which his revolver lay. He looked out into the room, but for the present only the colonel and the Kaiser were there, and they had sprung to their feet, their eyes towards the door, from the other side of which the sounds came.

"We can't have been discovered?" the Kaiser asked, in an agitated voice. "I was a fool ever to come here."

"It is our own men—there is something wrong!" the colonel growled in answer. "They make noise enough to be heard in Lerwick."

Before more could be said the door was flung open, and two of the Germans, a third man between them, whom they were supporting by the arms, came into the room. This third man, who appeared to be suffering from exhaustion and excitement, was the real Lieutenant Bergern.

Looks of amazement were on the faces of the Kaiser and Harmann.

"What is this?" the latter gasped. "Who is this man?"

"I am Lieutenant Bergern," the rescued man answered, in a weak voice, throwing himself free of the others, and standing upright, though he swayed slightly on his feet.

"This morning some man leapt upon me, half stunned me, then bound me, and left me a prisoner. Only now have my comrades found and liberated me."

With a cry, the colonel swung round and faced Sexton Blake, who, seated on the edge of his bunk, was smiling blandly. But behind his smile his brain was working rapidly. At all costs he had to get away. He knew that, and he meant to do it.

"There is the traitor!" Bergern screamed, pointing a shaking hand at the detective.

The latter slid down from his bunk, and stood with his hands in his pockets. The likeness between him and the real man was simply remarkable. They were alike as two peas.

"I think this man must be mad," he said quietly to the staring Germans.

Lieutenant Bergern made a fierce rush forward, but Sexton Blake gripped him by the arms and flung him back. At the same time he moved nearer to the door, though no one seemed to notice it.

With a half mad gesture, as if he wished to convince even himself of his identity, Lieutenant Bergern snatched papers from his pocket and flung them onto the table.

"Does that prove who I am?" he cried.

The Kaiser glanced down at the letters, Colonel Van Harmann looking over his shoulder; then both swung round upon Sexton Blake, who stood within ten feet of the door.

"Who are you?" he demanded.

Quite calmly Sexton Blake peeled the moustache from his upper lip, his expression changed, and he stood revealed.

"I am really sorry that you do not remember me, sire," he said, in a tone of regret, "even if not as a friend, as a worthy foe."

"Sexton Blake!" the Kaiser gasped, and his face went white.

Cries of rage broke from the other Germans, and one snatched at a revolver that lay on a shelf.

"Stop!" Sexton Blake thundered, and there was something in the tone that sent the man's hand dropping hastily to his side.

Sexton Blake still stood smiling against the wall, but now there was a revolver in his hand, and its barrel covered the Kaiser.

As the Germans saw this, and realised that their ruler was in danger of his life, they stood spellbound and speechless. Any one of them would have willingly given up his life for the Kaiser, but how—

"You see, it would be foolish to get excited," Sexton Blake remarked in an even tone. "Excitement makes the hand unsteady, and this is a hair-pull trigger."

The Kaiser straightened himself, and there was no fear in his eyes.

"You forget who I am!" he said fiercely. "I am the Kaiser!"

Sexton Blake bowed, but his eyes never left the other's face, and his hand did not remove the fraction of an inch.

"I think you are forgetting that you have already told me that you are Colonel Kelner," he said, very slowly and distinctly. "I must also add, Colonel, that where I should hesitate to shoot the Kaiser, I shall have no such qualms with regard to you."

The German who had tried to snatch the revolver from the shelf was eyeing the weapon again.

"One more thing!" the detective said sharply. "You are the leader here, so if one of your men makes a move against me, I shoot!"

There was a dead silence. From the expression of the Kaiser's face, it could plainly be seen that unpleasant thoughts were passing through his brain. Not that he feared death—he was too much of a man for that—but he was wondering what would happen when it was discovered that he was no longer in Germany. How would his death be explained?

"And to come down to my own position—which, I admit, is awkward," Sexton Blake continued calmly, "I must ask you to obey my orders."

"Never!" Colonel von Harmann growled.

"It must be!" the Kaiser said bitterly. "I am thinking of my country, not of myself!"

"It is a wise man who knows when he is defeated," Sexton Blake remarked. "All move over to the bunks."

At first the Germans hesitated, but a word from the Kaiser, who had already moved, sent them to the position ordered by Sexton Blake. There they stood glaring, and the detective quietly backed to the door.

He opened it, and stood in the doorway, a little smile on his lips—a smile that spoke of quiet determination rather than mirth.

"Gentlemen," he said coolly, "I have been through some exciting experiences in my time, but I really think that this one caps all. Good night!"

With a sudden jerk the detective had swung round and raced away across the uneven ground. His only chance was to get clear of the island by swimming, and that was what he intended to do.

From behind came wild cries of rage, and before Sexton Blake had run a hundred yards, making for the cleft in the rocks where the secret cave lay, two rifle bullets whizzed unpleasantly close to him. One struck the rock, splintering a small piece against his face.

"Whew!" he ejaculated. "I did not think they would dare to fire!"

There was no mistake about them daring to do so, for a perfect volley of shots pursued the running man; but now boulders lay in between him and his pursuers, so that there was little danger of being hit.

The firing ceased, the Germans evidently realising the uselessness of it, but the sound of men scrambling along behind him told Sexton Blake that he was not to be let off so easily. Down the cutting he ran, pulling up where it dropped sheer down to the rocks.

In the darkness he peered over, and just made out the rocks some fifteen feet below him; then a bullet hummed by, and he dropped down. His feet slipped on the slimy rocks, and he fell forward, missed his grip of the stone, and plunged into the sea.

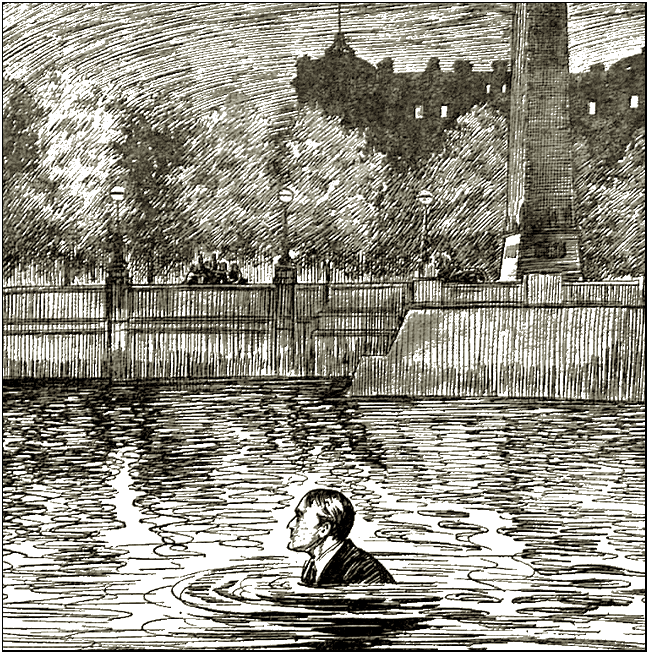

Luckily the waves were slight, or they must have dashed him back against the rocks, and so beaten the life out of him. As it was, he was well able to fight against them, and a few strong strokes took him out into practically clear water.

Would he still be followed, that was the question?

Twenty yards from the shore Sexton Blake turned and looked back. He saw the dark outline of the rocks of the little island, and as he scanned them closely a figure showed darkly on the summit, paused there a second, and came hurtling down into the sea, diving straight past the rocks.

The diving man was an enemy, yet Sexton Blake could not help catching his breath as he realised the risk that he was taking of hitting the rocks, and a sigh of relief escaped as he saw the man rise to the surface and strike out towards him.

No longer could Sexton Blake hesitate, and he swirled around in the water and swam straight for the open sea. As he did so, he caught a glimpse of another man diving from the rocks, while at the same moment a rifle cracked, the bullet splashing into the water close to his head.

The Kaiser and his men knew what would happen if he escaped, that the plans that had taken them years to formulate and carry out would all be knocked on the head, and they were doing their best to prevent him getting clear.

With a steady over-arm stroke Sexton Blake swam through the smooth water, meaning to get well out from the land, then turn and make for Lerwick. This would mean a three-mile swim; but he had accomplished that distance many a time before, and had no fear of failure now.

A hundred yards, two hundred, he covered, and turned to see where his pursuers were. To his amazement, he saw that the nearest was within ten yards of him, and swimming with a powerful over-arm stroke that was sending him through the water like a fish. Sexton Blake was no mean swimmer, but he realised that this man was quite as good as himself, and that a hard race lay before him, with for a prize—his life. Not that he thought of the latter. His one idea was to get away, so that the plans of the Germans, their years of subtle scheming and working, should be made useless.

Sexton Blake swam hard now, altering his stroke to a racing one, but when he looked back, after going a quarter of a mile, he saw that he had gained scarcely a foot on his pursuer. Probably the man had thrown most of his clothes off, so as to swim better, but the detective did not pause long enough to follow his example.

Low in the water, striking out straight ahead, Sexton Blake swum for dear life. A current caught him and whirled him in the direction of Lerwick, but that gave him no hope, for it would help his pursuer just as much. More than once he thought of stopping and fighting it out with the man, but each time put the idea from him. He knew what a fight in the water meant—probably the death of both. Life was precious to him just now—Great Britain had to be warned of its danger.

A splash behind Sexton Blake caused him to turn. The German was so close behind that he could almost have reached out a hand and touched him, and between his teeth was an ugly-looking knife.

The man took the knife from between his teeth, and sprinted with it ready in his hand. Sexton Blake tried to do the same, but his sodden clothes held him back, and he could not increase his pace.

Something ripped down the back of his coat, and he knew that it was the knife, which had just missed cutting into his flesh. Desperately he swung round to face the attack.

Then a strange thing happened. The German let go his knife, which sunk in the water, and turned and raced for the shore.

What did it mean? Why had he given up his task when it seemed so easy of accomplishment? Sexton Blake watched the man racing away, and was filled with amazement.

Chug, chug, chug!

The sound of a propeller reached the detective's ears, and as he turned in that direction he could faintly make out the outline of a small craft coming towards him.

"Help!" he shouted, and swam slowly in its direction, his strength failing him now that the worst of his task was over. That the boat was an English one he had no doubt, for he was certain that the Germans dared not approach with the Fleet so near.

A few minutes later a warship's steam pinnace swirled alongside the detective, and he was hauled into it.

"What been doing?" the voice of Spearing jerked. "Couldn't find you anywhere. Got permission to search islands. Beast of a job. Admiral so high and mighty."

"Leave him alone," the voice of Tinker put in. "Can't you see that he's done right up?"

"I'm all right." Sexton Blake managed to sit up, gasping for breath, and turned to the young officer in charge of the pinnace. "Kindly make for the flagship at once," he said.

The officer looked doubtful, though he knew who the rescued man was.

"Sorry, sir," he answered, "but I have orders to return to my own ship if you are found."

"As you will." Sexton Blake was quickly recovering, and his voice was quite steady. "I can only tell you that if you do not obey me now you may have no ship to return to to-morrow."

The officer bent forward from the tiller, a questioning expression on his face.

"What do you mean?" he demanded.

"Possibly the admiral will tell you when I have explained to him," Sexton Blake answered coldly.

The officer hesitated, annoyed at the way he was being treated, yet impressed by the detective's voice and manner.

He put the tiller over until the pinnace headed for Lerwick and the flagship.

The Admiral surprised—A Night Landing—

The Airship Pursued—The Kaiser in Trouble.

THE little pinnace ploughed its way through the smooth sea at a good pace, Sexton Blake sitting in the stern, entirely recovered from his exertions. But even now he was not out of his difficulties. He had decided to see Sir Henry Farrar, the admiral in command, and to show him all that was on the little island.

But the Kaiser? That was the trouble. Sexton Blake knew the type of man that the admiral was, and that he would make the Kaiser a prisoner as readily as he would punish one of his own men, and that was just what the detective did not want. He wanted to get the Kaiser away, to make terms with him.

Well, there was no time to think about it now, for the pinnace grated against the gangway of the flagship. The young officer led the way up onto the deck.

"How is that?" a gruff voice demanded angrily. "Lieutenant Anderson, I thought you knew that no one was to be allowed aboard a ship of the Fleet during the manoeuvres?"

Lieutenant Anderson saluted a trifle nervously. It was the admiral who was speaking, and most of the officers went more or less in dread of him, though he was a kind enough man at heart.

"I know, sir," he answered; "but this is Mr. Sexton Blake, the man who was missing. His friends are with him."

"But, hang it all, why bring 'em here?" the Admiral snorted. "Think I run this ship as a home for lost civilians, or what?"

Sexton Blake stepped forward and bowed stiffly.

"I am pleased to meet you, Sir Henry," he said.

The admiral glared, especially when he saw that the young lieutenant evidently wanted to laugh.

"Sorry can't return the compliment, sir," he said shortly. "I must ask you to leave at once. No one allowed aboard now. There are important manoeuvres to be carried out to-night. Good evening!"

But Sexton Blake held his ground, though he would have liked to have turned and taken the man at his word. But he remembered what his discovery meant to Great Britain, and he thought of the country, not of the man before him.

"You know why I am here?" he asked shortly.

"Heard something about it," the admiral admitted grudgingly. "Lords of the Admiralty!"

"Precisely, Sir Henry," Sexton Blake agreed. "They sent me up here to find out things, and I have succeeded."

"What are they?" the admiral growled suspiciously.

Sexton Blake shrugged his shoulders.

"Surely there is some better place than this to discuss important affairs," he answered.

The admiral frowned; he was not used to being dictated to at any time, and especially on his own ship. But something in the detective's quiet bearing, a certain dignity which even his sodden clothes could not rob him of, impressed him.

"Come to my cabin," he said shortly.

Along the deck the men went, and into the admiral's state-room. It was a plainly furnished apartment, with none of the fancy articles that many an officer ashore regards as essential to his comfort. It was the room of a man.

"Sit down!" Sir Henry said; and Sexton Blake took a chair by the table. "Now tell me what all this mystery means," the admiral continued. He glanced at the clock on the wall, and frowned impatiently. "In ten minutes I must sail."

"As you will," the detective answered boldly, "but I should advise you to postpone the manoeuvre, however important it may be."

The admiral's face went positively blank with amazement, and an angry flush showed under the tan.

"Don't fool!" he snapped. "Not used to it."

"Neither am I," Sexton Blake assured him. "I have come here to avert one of the biggest dangers that ever threatened Great Britain."

"Go on!" the admiral ordered, and again the quiet force of the detective was dominating him.

"You know that on more than one occasion the Germans have explored these islands," Sexton Blake commenced, "also that they have taken soundings all around them."

"Yes."

"But you do not know," the detective continued, speaking slowly and impressively, "that they have made charts showing a clear dozen landing places of which we have no knowledge, and that, what is more, they could steam up to them without danger."

"Impossible!" the admiral said shortly, though it was obvious that he was impressed. "It would mean taking soundings all the way."

Sexton Blake shrugged his shoulders, as a man weary of trying to convince another against his will.

"You have heard of the Dion system of undersea lights showing the way down a channel?" he queried.

The admiral started badly, and leant forward eagerly over the table.

"Yes," he said sharply.