RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

CHANCES, and the laws which govern them, are beyond the scope of ordinary human understanding, and the after results of some perfectly heedless action are sometimes bewilderingly amazing.

If Blake had not chanced to be passing down Merrit Street at two o'clock on a drizzling afternoon, one of the most extraordinary crimes of late years would probably have never been brought to light.

It so happened that there was an auction sale in progress that afternoon. Merrit Street is little more than a slum, and the odds were that the effects disposed of would be the merest rubbish.

But the drizzle was becoming a regular, soaking downpour, and more to get out of the rain than from any feeling of interest, Blake turned into the house.

There were the usual crowd of small dealers—the keen-faced auctioneer trying to instil a little life into the proceedings by an occasional burst of sardonic humour—and the inevitable collection of elderly ladies, who squeezed themselves into the front places and sat stolidly looking on, hour-after hour, without the remotest intention of buying even a shilling lot. Their bonnets were knocked askew by perspiring men in aprons, carrying bedding to and fro; their elastic-side boots were trampled on, but they stuck grimly to their posts, nibbling sandwiches and unhealthy-looking buns out of paper bags, whilst the actual buyers, standing in the background, answered the auctioneer's glances with casual nods or a murmured "and one."

Blake saw three rolls of bedding, a deal chest of drawers, and a mirror in a flash frame, with painted arum lilies, "all done by hand," hotly contested for, and he had determined to face the downpour outside rather than endure that stuffy monotony a moment longer, when, to his surprise, he saw standing in a corner a group of two or three well-known dealers—men who never bother about anything that isn't big money.

Such furniture as he had seen was quite out of their line—in fact, they had their backs turned to the auctioneer, and were exchanging racing tips and stories amongst themselves.

Still the fact that they were there at all meant that there was something worth looking at, and Blake changed his mind and remained.

He hadn't long to wait for the explanation, for almost the very next lot was a fine Chinese bronze. Others followed in quick succession. The small dealers dropped out, and left the bidding respectfully to the group in the corner.

These wasted no time, raised each other by nods, five pounds at a bid, or dropped out.

The bronzes were clearly valuable, for even these shrewd experts bought them in at fifty and seventy pounds apiece.

Then the run of the sale went back to ordinary household lots, and their interest died away.

Blake continued to watch, and his attention was caught by one little odd lot—a small cracked mirror, a damaged flower vase, and a very quaint-looking metal box—it was about eleven inches long, very heavy, and on rubbing the dust away he discovered it was plain, solid brass, and of obviously Chinese workmanship.

When it came on someone bid a shilling for the lot, it rose as high as three, and Blake himself said four.

"Four shillings," droned the auctioneer. "going at four shillings"—his hammer was already raised when from somewhere in front came a shrill, excited voice.

"I give you tlwenty soveleign."

Had a high-voltage electric shock been passed through the room there could hardly have been more consternation.

Everyone stared, and the auctioneer sat up with a jerk.

"I beg your pardon," he said. "I didn't quite catch."

"I give you tlwenty soveleign—I give thirty soveleign for him piecee box."

The crowd panted in amazement, and Blake caught sight of the bidder. He was a little wizened-up Chinaman, barely five foot high, and with a face like one of his own old native ivories.

He wore an ulster much the worse for age, and beneath it native costume; on his head was a rusty old bowler hat, with his pigtail coiled under it, causing it to perch jauntily on one side of his head; he had round, horn-rimmed spectacles, and carried a huge umbrella.

All this was noticeable and striking enough, but it was nothing compared with his air of intense, almost passionate, excitement.

The little man was literally trembling with anxiety and his voice shook as badly as his hands.

"Great Scott!" said the auctioneer, under his breath; "what kind of a dime museum is this."

"Have him on the table, and deal him off as a curio," whispered his clerk. "Valuable antique— priceless bit o' China."

"I give thirty soveleign," insisted the little man shrilly.

The auctioneer resumed his official manner on the instant, remembering his private commission on the sales.

"Going for thirty pounds, gentlemen, this valuable job lot, including a unique brass—er"—he consulted his catalogue—"including a unique brass Chinese money-box. Absolutely a give-away price, gentlemen, only thirty sovereigns. The Emperor himself has the only duplicate of it in his bedroom at the palace to save up for the week's washing bill. Come along—no advance on thirty paltry sovereigns?"

Some of the small dealers sniggered, and the little Chinaman's claw-like hands were stretched out as though he wanted to seize his prospective purchase then and there.

"Going——" said the auctioneer, and the word was hardly out of his mouth before the room got its second shock.

"Thirty-five!" said a deep voice. The speaker was a big, jolly-looking man, one of the small group in the corner—Louis Cohen by name, and by repute one of the cutest dealers on the market.

The auctioneer stared as if he could hardly believe his ears.

"Thirty-five—did I hear you aright, Mr. Cohen?"

The big man nodded.

"Fiftee soveleign," screamed the small man.

"Fifty-five," said Mr. Cohen promptly.

The whole room was in a state of tense excitement, and so great was the stillness that you could have heard a pin drop.

A whisper passed round the room : "Pearls— trust Lou Cohen to know a soft thing."

"I give one hundled soveleign," quavered the Chinaman, great beads of perspiration starting out on his forehead.

The auctioneer was now as excited as everyone else, and glanced at Mr. Cohen, but before that worthy could answer, the man next him had caught the word "pearls," and relying on Mr. Cohen's deserved reputation for getting accurate inside information and keeping it to himself, joined in the gamble and sprang the price up ten pounds.

Now, as a matter of fact, Mr. Cohen was relying on nothing more than his instinctive love of a gamble and his knowledge of human nature. He had had dealings with Orientals before. He knew that to get an Eastern dealer to offer anything approaching full value was a miracle—to get one to betray eagerness or anxiety was not a miracle, it was unheard of.

Therefore, when he saw a Chinaman—a descendant of the shrewdest trading nation on earth—spring a price from four shillings to thirty pounds at one jump, and be ready to go on after that, he thought he was in for a sure thing; and, being a rich man, was determined to have a run for his money.

"One hundled an' fiftee soveleign," screamed the Chinaman.

"One sixty," said the newcomer.

"And five," added Mr. Cohen.

The third man stuck manfully to his guns till the price had reached well into the second hundred.

Then with a grumbled "Leave it to you, old man. I've had enough o' this dip in the lucky bag show," he retired from the conflict.

"What did you want to jump the market up for, then?" snapped Mr. Cohen.

"Thlee hundled soveleign," wailed his remaining adversary.

"And five," retorted Mr. Cohen.

"Thlee handled and fiftee," came quaveringly.

The auctioneer looked at the dealer despairingly. "In heaven's name, Mr. Cohen, what's the meaning of this jack-in-the-box business. What am I selling?"

Mr. Cohen shrugged his shoulders; he might be making a fool of himself, but he had no intention of advertising the fact.

"You're pilin' up a blamed fat commission— ain't that trouble enough for you?" he replied, and shot a quick glance at his opponent.

The Chinaman was in a state of nervous collapse, and he judged that the time had come for a bluff.

"Four hundred," he said.

"Four hundled an' five"—the words were hardly audible.

"Four fifty. I ain't goin' to be beat by any blame Chinee on my own dust heap," said Mr. Cohen.

For the first time there came no response. The little Chinaman tried to get out some words and failed.

The auctioneer waited with raised hammer.

"Four hundred and fifty pounds," he cried. "Any advance on four-fifty."

"You, sir—did you say anything—come only four-fifty—pity to let it go at that, after such spirited bidding?"

"Hallo! stand back there, some of you—the gentleman isn't well—give him air. Stand back, please. Someone get him a glass of water—he's fainting."

The Chinaman was clearly at his last gasp with excitement. His lips moved, but no sound came. His hands waggled feebly as though in protest; then his head fell back, and the rusty old bowler-hat went rolling across the floor. Two men carried him out into the fresher air, and again there was an expectant silence.

.The auctioneer glanced at the clock.

"Time's getting on, gentlemen; we can't wait very long. But under the circumstances, perhaps——"

"I bid four-fifty," said Mr. Cohen. "And I must ask you, if you can't get a better offer, to knock the lot down to me."

The auctioneer hesitated for a moment.

"Going at four hundred and fifty! Going"—the hammer fell with a soft tap—"gone!" he said. And the spell of stillness was broken by a clamour of applause.

Mr. Cohen's voice rose once more above the din.

"If I pay for that can I have it in my hands—now at once?"

"Certainly, Mr. Cohen. I can see no objection in this case."

"You'll take my cheque, I suppose?"

"With pleasure!"

Mr. Cohen advanced to the table, dashed off a cheque for the amount, and handed it over.

"I'll send down one of my men to see to the other things," he said. And, picking up the precious box under his arm, hurried out.

"Now, I wonder," said the auctioneer appealingly to the room—"I wonder what the deuce it is I have sold? I've seen some queer things in the course of a dozen years' hammer-thumping, but I never saw such a rum go as that."

Ten minutes later the Chinaman came tottering back, gave one look round the room out of his little, slanting eyes, and then, without a word, he, too, stole out of the house.

Blake did not follow him; but he remembered his face.

NOT very long after that sale, Mr. Louis Cohen, who appreciated a good dinner—not wisely, but too well for a man of his build—ate just one too many, and died of apoplexy within a few hours.

His business passed to his heirs, and his private collection was dispersed. In most cases the odds and ends of it were left to friends and brother-collectors as mementoes. Only the very pick of the objects were sold.

One of these friends happened to be a German, the Baron von Marden; and, to everyone's astonishment, it was reported in the papers a few weeks later that the baron had committed suicide by taking poison.

The people who knew him best refused to credit this. Von Marden was a kind, genial man of middle-age, enormously wealthy, in the best of health and spirits, devoted to his wife and his art-treasures—in short, a man who thoroughly enjoyed life, and made a boast that he had never had an illness and never known a dull moment; That a man of his type and temperament should deliberately cut short his career seemed unbelievable.

The fact remained, however, that he was found dead of "ruthine" poisoning on the floor of his library by the under-housemaid when she came in in the morning to dust.

He had dined with his wife and some friends the previous evening, and had been in the best of spirits.

Before going to bed he had announced his intention of spending an hour in the library with a book and a cigar.

That was the last time he was seen alive.

It was quite out of the question that anyone could have broken into the room or the house. All the doors and windows were fitted with patent electric burglar-alarms, which were set each night by the butler and a footman, and these were found the next morning intact and untampered with in any way.

Moreover, there were no signs of violence or of any struggle; the body was found lying quietly in an armchair in a state of collapse, and life had been extinct, it was estimated, for at least seven hours, in which case he must have committed suicide very soon after entering the room.

Such at least was the verdict; and the newspapers reported accordingly.

Amongst those who refused to believe this version, however, was young Von Marden, the baron's nephew and heir. So convinced was he that his uncle had not taken his own life that he begged Blake to look into the case.

Blake had seen the various published accounts, and he also was of the opinion that somewhere or another, beneath the surface facts as known, lay another story of a very different kind, and he came as quickly as a cab could bring him in response to the nephew's telegram.

The first thing he asked to see was the body of the dead man—he had been by no means satisfied as to the accuracy of the reports.

Ruthine is one of the rarer vegetable poisons—very hard to come by, and peculiar in its actions. Taken internally it leaves, amongst other symptoms, a slight greenish discolouration of the gums.

Blake and young Von Marden went up to the darkened room, and the latter having pulled up the blind, Blake made his examination, disturbing things as little as possible. The green discolouration, as he had half-suspected, was completely absent, though other symptoms, indicating ruthine, were undoubtedly present, and had presumably led the doctors responsible to report as they had. For fully an hour Blake continued his work, whilst the younger man watched him. At last he gave vent to a sharp exclamation, and stood up.

"Look at this!" he said, pointing to the thumb of the right hand. "Either your uncle's death was accidental, which I don't believe—for ruthine is not a poison that anyone is likely to handle by accident—or, as I do believe, he was murdered with diabolical cleverness for some reason which we must find out later. Of one thing I am certain—this is no case of suicide. Look at the thumb-nail there and tell me what you see."

The young man looked.

"I confess I can see nothing—at least, nothing of any importance—unless you mean that the nail seems to have been slightly bruised at some time or another."

"That's no bruise," replied Blake sharply. He pressed the flesh away from the underside of the nail, revealing a tiny inflamed spot no bigger than a pin-prick betwixt nail and flesh. The wound—if "wound" it could be called—was barely visible, but just around it and beneath the nail itself there was a faint greenish tinge.

"That," said, he, "is the hurt that caused his death. Taken internally a fatal dose of ruthine is a matter of seven or eight drops usually—a man has been kept alive after swallowing a dozen. But if the dose is fatal death ensues almost at once. But taken hypodermically the action is very different. To begin with, a mere graze—a hundredth part of a drop is sufficient. Not only that, the action is peculiar. For five minutes or so it is anaesthetic, and acts instantaneously, so that a victim would not even feel the pain of the puncture which admitted it into his veins. He would be entirely oblivious for a short period; and on coming to himself would be conscious of a strange sense of exhilaration, an increased vitality. This stage lasts for varying periods of from ten to twelve hours. Then the anaesthesia returns, and is followed quickly by coma and death. He has practically burnt himself out in that time—the poison which caused him to feel so strongly exhilarated in those few hours has used up all the life in him to the very last drop.

"Your uncle died, not from ruthine administered internally by himself, but by an infinitesimal portion hypodermically injected. I read that at dinner on the fatal night he was apparently in unusually good spirits, even for him. Whilst at dinner his death-warrant was already written."

Young Von Marden shuddered.

"But who can have done it? So far as I know, he hadn't an enemy in the world; certainly not one so infernally ingenious as that, or so brutally vindictive. You are right, I am sure, in saying that that small wound was never voluntarily inflicted; for, to begin with, my uncle was a collector and a bon-vivant, but he was absolutely innocent of the rudiments of chemistry."

Blake nodded thoughtfully.

"The poison itself should form a useful clue by reason of its rarity and the difficulty of distilling it. No one but an expert chemist would dare to attempt such a thing. As for the rest, it's hard to say of any man that he has no enemies, however little he may have deserved them. To begin with, your uncle was enormously wealthy—that alone would be all sufficient to make some men hate him. Again, he was a collector; and many a man before now has been sacrificed for the sake of a jewel or some priceless object of bijouterie. By the way, has anything been missed—any object of value?"

Von Marden shook his head.

"So far as I know, nothing. Most of the smaller and more portable valuables are in cases in the library—the room in which he was found. Shall we go there and have a look round?"

"By all means," said Blake—and followed him down the stairs.

The library was a room of gigantic proportions—a miniature museum, in its way. Between big bookshelves filled with rare editions stood cabinets of exquisite workmanship filled with treasures of enormous value—jewelled snuff-boxes, silver cups of the thirteenth century, intaglios carved in single sapphires, and amethysts of wonderful purity of colour.

Every description of objects of art—for the baron was quite an indiscriminate collector. If a thing was beautiful or had a history, then he bought it and treasured it.

Tables, bureaux, chairs were littered with all sorts of wonderful things. Near the centre of the room stood a massive buhl table, which had once belonged to Napoleon. On this was the usual collector's paraphernalia.

"This is where they found him," said Von Marden, resting his hand on a chair by the table. "It was his favourite seat, and here amongst the pick of his collection he used to interview dealers or people who came to him with something to sell. Queer lot, some of 'em were, too; and there used to be some fine old wrangles.

"There were only two things which upset him— one was to catch a man out in a deliberate attempt to swindle, and the other to be asked to sell anything; the last especially drove him frantic."

"There is nothing missing from this room, you believe? Look carefully round, and see if you notice the absence of anything."

"I don't, Mr. Blake. But, frankly, my memory is none of the best, and there might be a dozen things gone. Wait a minute; there should be a manuscript catalogue in this drawer. But why should you be so anxious to know if anything has gone?"

"Because," said Blake slowly, "I am convinced that something has been taken. Moreover, if your uncle died, as the evidence shows, somewhere about midnight, the theft was committed and he was to all intents and purposes murdered between, roughly, noon and two o'clock of the same day. The Question in my mind is what was taken; when once we know that, we shall have another clue concerning the man who took it."

Young Von Marden stared.

"I'm afraid you are leading me beyond my mental depths, Mr. Blake. Still, here is the catalogue, and perhaps—— What's the matter?"

Whilst he had been speaking, Blake had begun to pace restlessly up and down, glancing keenly here and there.

Suddenly he gave a sharp, half-suppressed exclamation, and with a couple of quick strides had reached an old cabinet, which was partially concealed behind a screen. On the top of this was an old brass box, which he recognised immediately.

It was the Chinese money-box of the sale.

Now, it is true, it was clean and polished and bright, whereas before it had been dingy to a degree; but that it was the identical box there was no possible doubt, for low down on the right-hand side there was a dent where at some time it had received a blow. Blake had noticed that dent before.

He placed the box gingerly on the writing-table. "Where did your uncle get this?" he asked.

Von Marden smiled.

"It has rather a quaint story. It was sent him not long ago by a friend of his, a dealer named Louis Cohen.

"Uncle always used to chaff him, and say that he would give a hundred pounds to any man who could take Cohen in over a deal. As a matter of fact, poor Cohen was about the sharpest man in the curio market. Once or twice he got the better of my uncle in prices, and he always maintained that a cup in the cabinet over there, supposed to be a Benvenuto Cellini, was a fraud. The two used to wrangle over it by the hour. Just before poor Cohen died ho sent this box as a present, with a note. He called it the 'fool trap,' and told my uncle to keep it as a souvenir of the only time on record he, Cohen, had been obliged to confess that he had been fooled. The thing is worth, I suppose, a sovereign, but Lou Cohen had been bluffed into giving quite a big sum for it, under the impression that it contained pearls or something of value. When he got it home, however, he found there was a sort of trick inner compartment-which he could never open.

"However, he made pretty sure that there was nothing inside, and put the thing away till it occurred to him to send it to my uncle."

He stretched out his hand to take hold of it as he spoke, but Blake, quick as thought, gripped his arm and pulled it away.

"Don't touch it," he cried hoarsely. "Wait a minute—get me, if you can, a thick pair of leather gloves. I can't say for certain, but I believe that it was this box which caused your uncle's death. No—don't misunderstand me. Cohen knew nothing of it. But if I am right—and I am sure I am—I have seen the man who does! Now oblige me with a pair of gloves."

When Von Marden returned, Blake had laid out on the table a strong magnifying glass, a pair of tweezers, and an old knife.

His eyes were glowing with excitement, and he was hastily turning over the pages of the manuscript catalogue.

"Now," said he, "this box, as you say, is worth possibly a sovereign, yet I myself was present when Cohen gave four hundred and fifty pounds for it, and there was another man who would have given more, but he fainted through sheer excitement. I handled the box that same day, and I have just handled it again most carefully, and I can tell you one thing—something of considerable weight has been taken out of it. It is still heavy and massive, but it weighed at least half as much again before. My fingers are sensitive, and I am sure. Your uncle, so far as you know, was unsuccessful in opening the inner compartment?"

Von Maiden nodded.

"Listen to this, then. Your uncle was found dead on the seventeenth. Here are some extracts from notes in his catalogue:

"On the third, against an entry, 'L.H.—two superb ivory stocks, best period Oriental, possibly by Tung-lao-ling, £50'—comes this note: ' L.H. seemed much interested in collection, especially poor C.'s "fool trap."

"On the sixth is another entry. 'L. H. brought magnificent ivory group, undoubtedly work of one of the master carvers; offered to sell for five pounds, if I would throw in "fool trap." I suspicious, and H.'s manner strange. Finally offered to give me carving and twenty pounds for the box. Can't understand it. Naturally wouldn't part, and bought ivory for seven guineas. Worth at least ten times that.'

"Now we come to the last entry of all, dated the sixteenth, the very day of his death.

"'L.H. brought large assortment, various. I questioned him about box, and whilst I looked at things he fetched it from the cabinet; said he thought he could show me how to find secret spring. He did.

"'You press small nick on under side inner lid.

"'The box quite empty, just plain brass (poor old C.). L. H. sat by in chair grinning whilst I sorted over things—an indifferent lot. Bought two small carvings for a couple of guineas.

"'Asked L.H. why he wanted box. Said he'd changed his mind and didn't. He'd found another—lying, of course. Fancy, like C., he must have thought there was something of value in it.'"

Blake closed the book.

"And there, in his own hand writing, is the history of your uncle's murder," he said.

"But I don't understand," began Von Marden.

"Don't you see? This L. H. referred to here is the man who bid against Cohen for the box. Unfortunately, your uncle does not give names in full."

"No; he was afraid of other collectors. But go on, please."

"When Cohen died, this L. H. probably tried to find the box at his sale, but as it had been given away, he naturally failed. He had probably been ill after his seizure at the other sale, or he would have tackled Cohen direct. He comes here in the ordinary way of business—the entry of the third shows that your uncle knew him—and asks fifty pounds for a couple of ivories. Quite by accident be sees the box.

"A little later he comes back with a carving quite as valuable, and asks as his price—not fifty pounds, but five and the box.

"Your uncle flatly refuses to part, and L. H. goes away in despair, plotting to get—not the box, but its contents.

"After an interval he returns with a lot of rubbishy things, which it will take his customer some time to look over, and whilst he is doing so, makes an excuse to handle the box and prepare the hidden spring with ruthine—smeared or dropped it on with a feather, probably.

"Then he tells his victim how to open it— remember the temporary anaesthesia caused by injection is instantaneous,.

"Your uncle presses the spring, the concealed needle point charged with ruthine enters under the thumbnail, and he becomes unconscious.

"Then L.H. darts forward, secures the contents, and, in your uncle's words, sits there grinning, waiting for his victim to wake again and find the open empty box before him—enjoying with fiendish malice the sure knowledge that the man he is grinning at will be dead in ten or twelve hours. It is just the grim sort of revenge a Chinaman would revel in."

Young Von Marden brought down his hand with a bang, on the table.

"A Chinaman, did you say?" he cried. "By Jove, Mr. Blake, you're right. There was a little shrivelled-up Chinee here at about one o'clock on the day of uncle's death. He's been here several times, and his name is Li Hwen."

"That's our man, then," said Blake. "Do you happen to know where he lives—not that it matters much; I can find him easily in a few hours."

"But I do know it. It's a dirty little shop down by the docks."

"Good! Well, as we've plenty of time, if you will give me the gloves we'll have a look at the box."

Blake drew on the thick protecting gloves, and picked up the magnifying glass. The outer lid of plain thick brass opened easily.

In the top of it was a slot for "cash," the coins usually carried on long strings threaded through a hole in the middle, and a lever which pressed down admitting each coin separately.

Blake examined this thoroughly through the glass before pressing it down with the knife blade.

It was harmless enough, however, and he threw back the lid revealing the empty interior and the secret compartment, which was about four inches square.

"Ah, here we are!" he said, peering through the glass. "Do you see there the faintest trace of a sort of viscous fluid? That's where the ruthine has been applied, and here's the spring."

It was a fiendishly cunning piece of work. The concealed spring was practically invisible, and so placed that it could only be reached by the very tip of the fingers or thumb, with the nail held uppermost to get under the slightly projecting ledge.

In this way it was imperative that whoever pressed the spring was bound to receive the needle point betwixt nail and flesh, where the wound was, to all intents and purposes, invisible, even to the sharpest and keenest scrutiny.

"Now watch!" said Blake.

With the point of the penknife in one hand and the tweezers in the other, he pressed the spring-on either side.

There was a click as the lid flew back, and out of the centre of the spring a minute steel point, finer than any needle, flashed out for perhaps an eighth of an inch, and vanished again as quick as thought, leaving behind it a tiny film of moisture.

"That," said Blake. "is how Baron Von Marden died. And now let's get a cab and catch the man who murdered him before it is too late!"

LI HWEN'S shop was dingy and dirty with the grime of ages. In the unclean windows were a few ships carved in bottles, lumps of coral, and such things as deep-sea sailormen collect and sell.

But inside in a little back room were fine specimens of Oriental work.

The two men walked straight in. The little man, still wearing his shabby ulster over his native clothes, sat poring over an open brazier. In his hands was a small dull object which he whipped behind his back as he heard their steps.

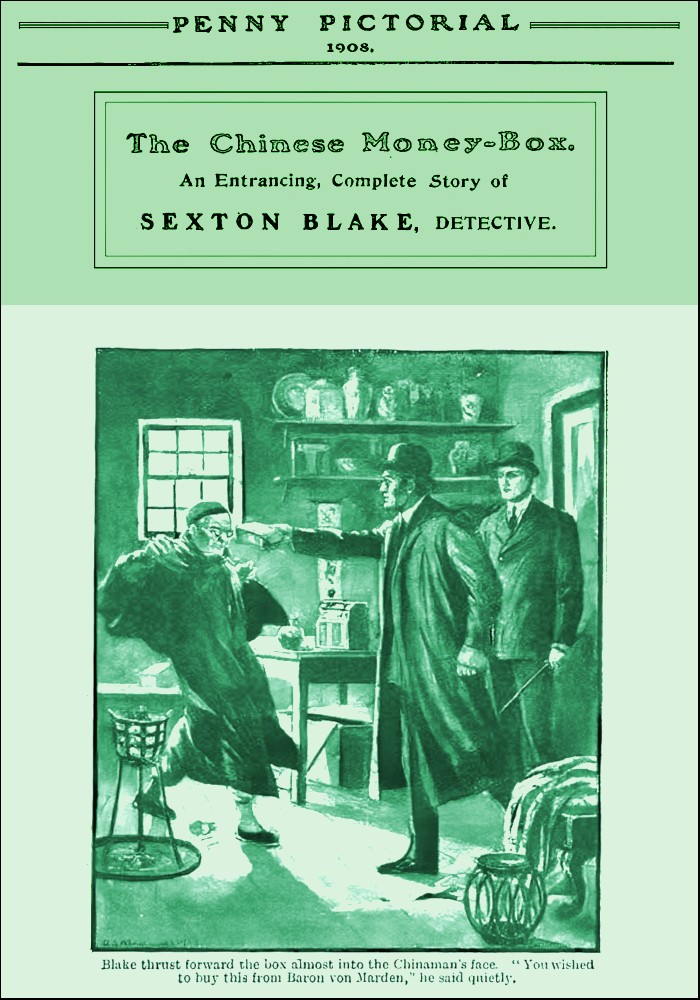

Blake thrust forward the box almost into his face.

"You wished to buy this from Baron Von Marden," he said quietly.

The Chinaman blushed, and then gave a hoarse scream of fear and anger, throwing up his hands. As he did so a small gold image of Buddha and a scroll of writing fell to the ground.

Blake darted forward and snatched it up.

For one brief second the Chinaman clawed and struggled like a mad thing. Then he broke away, finding it useless, and stood leering at them, with a weird, unearthly, senile giggle horrible to hear.

With a quick, cat-like movement he thrust his hand behind him, fumbled for the box, and pressed the spring, before either of them even guessed what he was up to.

Von Marden grabbed at his wrist, but too late.

The Chinaman wriggled free, and then with a. mask-like smile and an action not devoid of dignity, he held his thumb out for them to see.

. Under the nail there was already a slight greenish discolouration. Ho was an Oriental and a fatalist.

Not a word passed between them, as, with the same fixed smile, he went to the corner of the room and sat down, his eyes continually fixed on the gold image and the scroll in Blake's hand.

Blake glanced at the quaint Chinese writing. It had clearly been rolled up tightly and concealed in a small hollow in the image.

He tried the latter. It fitted perfectly in the secret compartment of the box—so easily yet so perfectly that no shaking could cause it to move or rattle.

"What is it?" asked Von Marden.

Blake shrugged his shoulders.

"The ways of Chinamen are not our ways, and we can't even hope to understand them. Here is a small gold image worth perhaps twenty pounds, and a rubbishy scroll about Confucius' theories on the secrets of perpetual life. And yet he offered probably half his fortune for it, and committed murder—and now that he has lost it he immediately commits suicide. We must leave him and go to the police. He won't attempt to move from there till the end comes."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.