RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

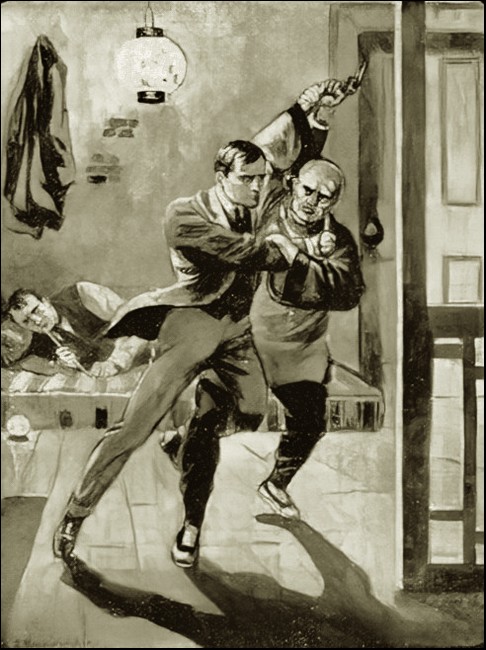

With a jerk Blake threw the man half off his balance, and, seizing his

pigtail, gave it a swift turn around the muscular neck and pulled tight.

THE quadruple-screw turbine-driven Meretoria, of the Rockall Holme Line, was absolutely the last word in Atlantic travel. She had reeled off her twenty-eight knots to the hour on her official trials, and on her maiden trip was confidently expected to knock the bottom out of all existing records, in spite of the fact that she could not be driven hard until she had had time to sweeten down a bit.

The papers had been full of her and her wonders for the past fortnight. American billionaires were outbidding each other to secure the most magnificent suites of rooms on board, and the Government had selected her as the vessel to carry three millions in gold for the relief of the financial stress in Wall Street.

This last fact was also published broadcast in the papers, and caused certain officials, including Mr. Mason, the Meretoria's purser, no little uneasiness. For a crack Atlantic liner frequently carries some very queer passengers, whether she will or no—gentlemen with very sharp wits and very nimble fingers, at the topmost pinnacle of their profession. Consequently the stowing of the specie was carried out with the utmost secrecy and precaution.

Sexton Blake had been sent an invitation for the trip out and home by an old friend—the head of the line—Andrew Rockall. A comfortable cabin on the port side of the boat-deck had been placed at his disposal, and Mr. Mason, the purser, had received instructions to take especial care that he was made thoroughly comfortable.

Mr. Mason was a portly, middle-aged man, who, from years of experience, could talk an infuriated woman with a grievance, or a slighted millionaire, into a good temper without losing his own, and wrestle with intricate accounts and details of management whilst a hundred and one people pestered him with foolish questions.

Next to the captain, Mr. Mason considered himself, and rightly, to be the most important man on the ship's books; and he certainly had to work like a dozen men from twenty-four hours before the first passenger stepped on board till the last hat-box was overside at the other end of the journey. Yet no passenger ever saw him busy. He always seemed to have time for a smoke and a chat, or a smile and the latest story for a dull group in the smoking-room.

Blake, being a privileged guest, had come on board a whole day before the date of sailing, and had been shown all over the ship—from the navigating-bridge deck and the Marconi house abaft the second smoke-stack amidships, to the chain lockers and profoundest depths of the great engine-rooms far under the lower orlop deck.

He and Mr. Mason had taken to one another on sight, and the two were sitting chatting comfortably over their cigars in the purser's own room. It was the first rest Mr. Mason had enjoyed for many a weary hour, and he stretched himself out in his deep chair luxuriously, and unbuttoned his expansive waistcoat.

"Thank heavens for a bit of peace and quietness!" he grunted. "Mr. Blake, you'll join me in a liqueur? We've some cognac the King himself might be proud of. Steward, get me two glasses of the No. 35 special—large glasses! To think," he added plaintively, "that by this time to-morrow I shall have to be grinning like a Cheshire cat on both sides of my face, and keeping a sharp eye lifting to make sure that the fellows in the smoking-room are doing justice to our cellars—whilst Miss Smith from Harlem wants to know exactly where I've mislaid her 'gums,' and Mrs. Smith is asking me to take a message to the captain at once, to tell him that he must keep the boat on an even keel, or she won't answer for the consequences."

Blake smiled condolence.

"A purser on a big liner ought to have five heads, fifteen arms, and a score of understudies to satisfy everyone. I've seen the Atlantic tripper before now, and felt sorry—for the purser."

Even as he spoke the telephone on the table whirred aggressively.

"Oh, lor'!" groaned Mason. "No rest for the wicked. What's the newest brand of trouble, I wonder? Eh? Yes! All right! Who the dickens are you, anyway? Yes, I'm Mr. Mason. What then?"

"By Jove! Mr. Blake, you must excuse me!" he exclaimed a moment later. "Or, if you care to, you can come right along. It's the people from the Bank of England waiting to deliver specie, and see it weighed and stowed. It's not often that a man gets the chance of clapping eyes on three whole million sovereigns at a time. You'd better come."

Blake raised his eyebrows slightly.

"I thought all that had been got through this afternoon," he said. "I saw some big lorries with the orthodox bullion-boxes, and obvious detectives on guard alongside; and later I had a glimpse into the specie-room under the mail-sorters' office for'ard, down under the orlop, and surrounded by baggage-holds, with the fresh water-tanks below it again. It occurred to me to be a good, inaccessible place, and they were piling in the little iron-bound cases as if their lives depended on it whilst I was there."

Mr. Mason gave a fat chuckle.

"I take that as a compliment—a big compliment—since it comes from you, Mr. Blake. That was all a fake—an idea of my own. You see, if anything went wrong, the chicken who would get it in the neck would be largely me.

"I spotted a young crowd of reporters hanging about, and a stray camerist or two. The Press boys are nice children, as a rule, but they are mighty inquisitive at times, and naturally they have to play for their own hands or get fired.

"Well, the moment I spotted that lot, I knew the Press would be busy over the wires, and they'd be wanting nice sensational pictures to fill up the blanks in the copy.

"So I just sent a cipher wire to the Bank, and had a whole lot of dummy boxes toted along with due state, and every blame reporter was on them like a knife. One man even had the nerve to offer me half-a-sovereign to let him come aboard and take a photograph of them being lowered down the forehatch. I took his half-sovereign, sure, and passed it along later to the stewards' fund.

"But the real bullion is lying right on the wharf-side now, and each case is packed in straw in a provision hamper, with a Leadenhall Meat Market label attached, and a private seal on the string; and they're not going into the specie-room, either.

"Three million in gold might draw a smudge on an archangel's reputation for honesty, so this particular three is going into a little private cubbyhole specially devised for it.

"Nothing short of dynamite would force the door, and it has three separate locks. I hold the key of one, the captain the second, and the Bank people the third. We shall each lock one combination, and the Bank people's key will be sealed in an envelope as soon as they're through with using it, and enclosed in a special locked mailbag to the authorities on the other side. Now, time's moving, and I guess we'd better be doing the same."

Sexton Blake and Mr. Mason made their way up the grand entrance companion, and stepped out on deck into the cool night air. Only a few incandescents were alight on the main deck, and by their rays hampers, not unlike cases of wine in shape, were being carried up the gangway.

The place swarmed with plain-clothes' men and detectives, and at the gangway-head were four elderly gentlemen in caps and ulsters, watching the passing of each case with a careful eye.

The captain—also in mufti—joined the group, with a perfunctory nod to Blake and Mason.

Beneath the purser's snuggery was a blind space—-a huge steel safe, neither more nor less. It was right amidships, and measured some fourteen feet square. The only entrance to it was a heavy sliding door hidden beneath a section of parquet flooring, and a thick rug immediately below the purser's massive desk.

To slide back the door itself was the work of two able-bodied men, and the clang of it, as it rumbled back along its grooving, would have awakened half a ship's company.

The hampers, with their precious contents packed in iron-bound, square boxes, were duly examined one by one, weighed on a specially tested machine, and lowered into the strong-room under the eyes of the Bank officials themselves, each being carefully checked and initialled for by the three people mainly responsible.

Finally, the captain, Mr. Mason, and the senior inspector from the Bank used their several keys, the two former pocketing theirs, and the latter slipping his into an envelope, which he sealed, unseen by the others, and placed in a strong leathern mailbag, which he locked with his own hands. The floor section, rug, and desk were replaced, and the Bank officials took their leave, as did the captain.

"There!" said Mr. Mason, mopping his forehead. "Thank goodness that's over, and precious glad I shall be when I get my receipt and tally on the other side.

"I've a rooted objection to specie in bulk—unless it happens to be lying to the credit of Richard Mason in the vaults of his own bank. You can't earmark the beastly stuff, and you can't trust your own brother whilst it's lying about."

He stamped his heavy foot on the floor, and the sound rang dull and true, not suspiciously hollow.

"Just think," he cried; "there's enough lying under my shoe-leather to build a couple of battleships, and still have a modest competence and a house or two in Park Lane leftover. I sha'n't sleep easy at night, I can tell you, and if I find anyone smelling round after lights out, that man will be apt to die of lead poisoning"—and he nodded towards a big revolver hanging in a holster over his bunk.

"I should put that thing away," said Blake sharply; "if anyone does mean mischief, the very first thing he would do would be to watch you well out of the way and tamper with the cartridges or the lock action."

Mr. Mason scratched his head.

"Mr. Blake, I've been smelling round and thinking I'd been pretty smart; you may call me a fool if it will do you good, for I never thought of that. I'm much obliged for the hint. That revolver goes out of sight, but within handy reach, and not even you yourself shall know where I put it. Now it's getting late, and I've a long day ahead of me; so, if you don't mind, we'll just have a final throat-cooler and turn in. The trippers will be on hand a little after mid-day, and we sail at dusk."

THE Meretoria went down the yellow, muddy river under easy steam, having left her moorings at 4.30 p.m, on the following afternoon. Mr. Mason, true to his word, was grinning like a Cheshire cat with affability. They had a cram-full passenger list, and it was necessary that the Meretoria and her staff should prove so satisfactory that no one would ever want to travel by any other boat so long as business or pleasure took them across the Atlantic.

If they did—especially if any of those who took the most expensive suites of cabins did—Mr. Mason was likely to get into serious trouble.

Every possible comfort and facility that ingenuity and forethought could provide were provided to the full.

Even the purser himself admitted that things were running on oiled wheels, and the captain, aloof and solitary, gave a curt nod and a grim smile of approval when Mr. Mason gave him a cursory report.

They had sailed together on three separate ships of the line, and earned promotion shoulder to shoulder; betwixt such men a grunt and a momentary twitch of the lip-muscles meant more than a volume of speech between men who were strangers.

The Meretoria, being more than up-to-date, had a restaurant and café, as well as an ordinary dining-saloon; and before darkness had fallen an hour or so, the restaurant tables were crammed, and the champagne corks popping, whilst a gay buzz of chatter and laughter rose on all sides—some were hungry, others feared that they might never be hungry again till they reached Berra fir once more, and so were taking advantage of the smooth waters of the river to eat their last meal before resigning themselves to the inevitable.

They were the usual cosmopolitan crowd. American financiers, loud-voiced parties from Chicago and Louisville doing Europe, Germans, Frenchmen, mining engineers, travellers for big business houses, and a few small parties of smart English people, who kept themselves very much to themselves, and a smattering of the artistic musical and scientific big-wigs.

Blake watched the groups with amusement, but kept aloof; and, as usually happens after passing Queenstown, the various circles and cliques began to mingle together.

Acquaintanceship grows apace aboard ship, and entertainments were organised to kill time. Hermann, the noted pianist, gave a recital. Professor Mortimer, who had an extremely pretty and popular wife, and was himself an expert on microphotography, gave a lecture, accompanied by limelight pictures thrown, on a screen, for which purpose he was allowed to have his apparatus got out from the emergency baggage hold, and removed to his state-room. The following night, the weather being fine, there was a dance, followed by a supper in the café. In short, the voyage was a huge and stupendous success, and, when still three hundred miles from Sandy Hook, the Marconi installation was clicking and snapping busily, sending messages to the shore station, both private and to the Press.

A dozen snub-nosed little tugs muzzled against the Meretoria's long, lean sides, and shoved and wriggled and prodded her into her berth, whilst admiring ferry-boats and other craft of all sorts and conditions hooted her a welcome on their sirens, and signified their noisy approval of this her first visit to American waters.

The great gangways were run out, the Health officials and the Customs made themselves as fussily obnoxious as usual; There were hurried good-byes, and the great ship was left deserted by all but her crew and the small army of stewards and stewardesses, who were already waging war on the litter left behind by the passengers, and making preparations for the comfort of the fresh batch which would arrive in a few days' time.

Blake, who frankly detested New York, remained on board watching the bustle and the crowd, and the busy derricks hoisting out the baggage from the holds.

Later a small squad of detectives marched down and the pseudo bullion boxes were placed on a lorry and conveyed away.

It was not until dusk had fallen, however, that a small group of officials came down from the Bank, and an ordinary unobtrusive-looking covered cart drew up on the quayside near by.

"Come and see me hand over Uncle Sam's little tip of three millions," said Mr. Mason; and Blake, lighting a fresh cigar, strolled into the purser's den, where the Bank officials were already assembled. One of them carried the private mail bag, which he unlocked with a duplicate key, and took out the sealed envelope. This he examined carefully, opened and took out the key of the third combination, handing Mr. Mason a receipt for the same.

A moment later the captain entered with his key in his hands, followed by a steward carrying a tray laden with champagne glasses and cigars.

"Now, gentlemen, I think we can get to business," said Mr. Mason. "As you will see, we devised a snug strong room for your bit of money. Jameson"—to the steward—"roll back that desk of mine into the corner and pull up the rug. Captain, you have your key, I see; here is mine and I shall sleep easier without it to-night, I can tell you; for, till a few moments ago, I've been wearing it round my waist, and it's left its mark on my fat sides. Shall I undo my lock first? Very good!"

He knelt down heavily, and turned the first combination. The captain and the man from the Bank did the same, and the heavy sliding door went rumbling back in its grooves.

Three of the Bank officials clambered down into the strong-room, the fourth, a chief teller, assisted by two of the ship's stewards, stood by the weighing-machine.

One by one the crates were hoisted out, checked and weighed.

"Say, Mr. Mason," said the teller, during a pause, "this was a real smart notion of yours. The Press have been spreading themselves over this shipment, and half the crooks in New York have been scratching their heads and worrying to grab some of the loot. There was an organised rush on that dummy lorrie you sent off earlier, and two men got hurt."

The checking and weighing went on monotonously, and the captain nodded to a steward to open some champagne.

Suddenly, Blake, who had been watching, twitched Mr. Mason's sleeve and gave him a warning glance.

Unobtrusively the two withdrew to the far corner behind the rest of the group.

"Two of those crates have been tampered with," whispered Blake quickly. "Their weights passed muster, but they've been opened. I can swear to it. I saw them put in, remember; then each one was tied in exactly the same manner, and with the same kind of string. Now, those two over there which have just been moved off the scales are tied with much thinner stuff—just ordinary stout parcel string. Look!"

Mr. Mason looked, and gave a quick, gasping "My heaven!"

The captain and the teller turned sharply. Mr. Mason pointed with quivering finger.

"Gentlemen, some one has been monkeying with the bullion. Mr. Blake—Mr. Sexton Blake, whom you all know by reputation—was with us when it was stowed, and he has just pointed out to me that those two crates which have passed the scales have been opened and refastened."

"Lock the door," said the captain sternly.

"Mr. Mason, I can hardly believe such a thing possible! Nothing short of dynamite could have broken a way into that place."

"Look at the string, sir," said the purser.

The captain looked and frowned. He and the teller exchanged sharp glances.

"I guess they'd better be opened right here," said the latter, "or I can't put my name to a clean receipt."

The crate was wrenched open, and the iron-bound case removed from its straw packing. A glance was sufficient to show that that had clearly been treated with violence.

A cold chisel and a hammer splintered the lid to fragments in a trice, and a cry of dismay went up from the onlookers.

The box was empty except for several large thick sheets of lead tightly wedged into place!

Mr. Mason stretched out a shaking hand, and, seizing a tumbler of champagne, drained it at a gulp.

"This beats me," he said apologetically.

"One moment," said Blake. "Captain, would you kindly issue a general order that all work is to be suspended in the cabins and state-rooms at once, and that they are to be vacated by the stewards till further notice?"

The captain sprang to the telephone, and rapped out the command sharply.

"Anything else?" he asked.

"If possible, the news of this discovery must not leak out of this room."

"Pray Heaven, it doesn't! Gentlemen, in our own interests, I think you will be ready enough to agree with Mr. Blake. And, you"—turning to the stewards—"will find it to yours; for if so much as a whisper gets round each one of you loses his job, and I'll take good care he never gets another on a Rockall Holme boat."

"Now let's finish the rest of the checking as quickly as we can," said Blake.

The task was soon concluded, and, as far as outward inspection went, at any rate, only those two crates had been touched. The teller wrote out a receipt.

"You will understand," he said, "that, under the circumstances, I can only acknowledge these other crates as being supposed to contain specie. Your manager had better send a couple of men round from the office to the Bank, and watch the detail checking there."

The captain nodded, and shortly afterwards two covered vans rumbled unostentatiously away, whilst four men, with their hands on the revolvers in their pockets, strolled unconcernedly beside and behind each.

The captain, the purser and Blake were left alone with the two dummy crates.

"Eighteen thousand pounds," said the captain, with a groan. "If this gets out, the ship's reputation is ruined—done for!"

"How in fury was the trick done?" growled the purser.

"I think you needn't despair," said Blake quietly. "If you can let me have a plan of the ship and the passenger list, and half an hour or so to look round, I am pretty sure I can tell you how it was done. Because, you see, I would bet five pounds to a penny that I know who did it!"

IT was a bitterly raw, cold night with driving sleet, and getting on for midnight, as Blake and Mr. Mason trudged through the sloppy streets of the poorer quarters of New York.

"I don't know where we're going, or why!" growled the purser, plunging his hands deeper into his pockets. "But if it will bring us any nearer getting hold of the missing loot and the scoundrel who took it, I can put up with even this infernal blizzard."

"Unless I'm very much mistaken," said Blake, "within an hour we shall have collected both. I can promise you the man, at any rate."

They skirted the Bowery, and headed up for the small but densely-crowded Chinese quarter.

"Chinatown, by Jove!" said the purser. "Well, you're navigating officer this trip. I feel more as if I was lost on the banks in a heavy snow squall."

The stink of decayed fish and other Chinese delicacies drifted out towards them, many coloured lamps and weird inscriptions danced before their eyes, and at one corner Blake glanced sharply down a side alley, and gave an almost imperceptible signal to a small covered cart standing by the kerb, the driver crouching down out of the wind, and nodding over his pipe.

The next moment they stopped opposite a dingy-looking tenement-house. In the cellar, through the mist and steam on the small window-panes, they glimpsed flaring gas-jets and a crowd of Chinese playing fan-tan. For a Chinaman will work like a slave all day, and gamble all night. On the first floor was a shabby little joss-house.

Blake signed to the purser to move quietly, pushed open the door, and shut it again quickly behind them.

An old Chinaman, the sole occupant of the room, glanced round, startled and alarmed. The place was a mass of tawdry tinsel, garishly-painted images, candles, and lanterns; and here and there a really fine specimen of lacquer ware. One of these-was a magnificent cabinet fully eight feet high, its gleaming black panels beautifully ornamented with a gold design.

Blake gave the old man no time. He clapped one hand quickly over his mouth, and with the other seized him firmly but not roughly by the scruff of the neck.

"Open the cupboard," he whispered to Mason, nodding to the cabinet.

The purser did so.

"Now press on that dragon thing on the back—on the head part—so."

The back of the cabinet swung noiselessly open.

"Out of the light," said Blake. "Follow me closely, and as soon as we get to the room we're bound for clap the door to, set your back against it, and, if need be, shoot anyone who tries to get out. You've brought your revolver? Good!"

He took the small Chinaman, and ran him through the secret panel at the back and up a narrow stairway beyond. Three flights in all, and Mr. Mason, puffing and panting behind him, became aware of a sickly sweet, not unpleasant, perfume.

"Opium," he said to himself, sniffing. "And good smuggled opium at that, or I'm no judge."

The next instant Blake had flung open a door, and sent the small Chinese reeling into a corner. A blast of stifling hot air and a glare of light met them, and Mr. Mason, obedient to orders, slammed the door to, planted his broad back squarely against it, and brandished a revolver.

It was a fairly big room—far bigger than one would have expected to find in such a house. It was lighted solely by one hanging, unshaded oil-lamp, which stank abominably. The walls and meagre furniture were shabby to a degree, and stained and dirty and smoke-begrimed.

But there was a roaring stove, which made the place like an oven, and, as Mr. Mason had said, the opium smoked was too good to have come through the Customs.

All round the room ran shelving bunks, heaped up with dirty piles of rags, and on some of these dozed a still dirtier mixture of humanity in a state of semi-stupefaction, though one or two certainly seemed to belong to a superior class to their neighbours.

Two or three small Chinese boys, barefooted, attended to the needs of the smokers, replenishing the little spirit-lamps by the bunksides, and cooking the little balls of opium in the flames, before placing them in the tiny bowls of the pipes.

The old Chinaman lay whimpering in the corner where he had fallen, but in the middle of the floor stood another of a different type—a big, strongly-built man with a sallow, scowling face, and evil, slanting eyes. The moment he saw Blake he whipped his hand behind him beneath his loose smock with a veritable scream of rage.

Blake sprang for him, and caught his arm by the wrist, bending it upwards and backwards. The hand held an ugly-looking revolver. With a jerk and a swing he threw the man half off his balance, and, seizing his pigtail, took a swift turn round the sallow, muscular neck, and pulled tight.

The fellow struggled like a mad beast, and in spite of the fact that he was half throttled, gave Blake all he could do to hold him.

Mr. Mason dodged round and round the reeling pair, puffing heavily till he saw an opening, and then brought down the butt of his own revolver smartly on the ruffian's skull.

The man's muscles relaxed and grew limp, and he flopped on to the floor. Blake dragged a pair of handcuffs from his pocket and promptly snapped them on.

Then he darted to the door and peered down the stairs, listening intently. Not a sound was to be heard, and closing it again carefully, he walked over and examined the occupants of the bunks—the small attendants staring at him in open-eyed fright.

At last he stopped in front of one of the smokers.

"Mason, come here," he said in a low voice. "There's your man, and half my promise fulfilled."

The purser bent over the unconscious, prostrate form on the heap of dirty rags.

The eyes opened slowly, and the man made a feeble struggle to rise, but sank back again with a snarl which ended in a sigh.

"Good heavens!" said Mason. "Professor Mortimer without his whiskers."

Blake nodded.

"That's the man. The next thing is to find the loot. You keep an eye on the door and the Chinese ruffian there—if he bellows, stuff a rag into his throat; the professor is too far gone to give trouble!"

Blake gave a hurried look round him, and then proceeded with a systematic search of the room.

He had barely been at work five minutes when, with a sudden exclamation he stooped down and began prising away at a loose plank.

It gave with a jerk and a snap, revealing a hole beneath the professor's bunk. Inside lay four big cylinders of compressed oxygen—or, at any rate, cylinders such as are used for that purpose, and for working limelight lantern shows.

"Eureka!" said Blake with a smile. "I've found the stuff all right."

Mr. Mason peeped over his shoulder.

"Those things," he said, with a snort. "They are only part of the beggar's luggage. I remember them coming on board, and a beastly nuisance they were; it took a couple of men to handle each of 'em. And he made a deuce of a fuss about getting them certified to pass through the Customs this end unopened. Wanted them stuck in his state-room; but I'd no use for him breaking his shins over them in a seaway, and stuck 'em in the light baggage hold. However, we had to rouse them out when he gave his lecture—so he got his own way in the end."

"Almost!" said Blake quizzically. "Anyhow, we'll just take the professor, his belongings, John Chinaman and all back to the Meretoria. You mount guard here whilst I run down below."

Once out in the street again Blake gave a low whistle, and the cart to which he had signed on entering pulled up a few doors away, and four men got quickly out of it.

In half an hour the still-unconscious professor, the cylinders, and the handcuffed Chinaman were back on board, and in the purser's room, where, much to the latter's surprise, seeing that it was past one in the morning, the captain and the teller from the bank were waiting for them expectantly over a peg and a cigar.

"Can I give a few orders?" asked Blake.

"Anything you like," said the captain. "But in the name of goodness, man, tell us—have you succeeded?"

"You shall see!" said Blake.

"Steward, kindly get a couple of your men to bring me an empty hip bath, or something of the sort, and a big barrel of very hot water. Mason, I'll trouble you for a spanner if you've got such a thing."

The others looked on bewildered at these preparations, whilst the Chinaman was marched off in charge of a couple of men, and the professor still breathed stertorously on a couch.

"Pick up one of those cylinders and drop it into the hot water," said Blake. "Gently does it—that's right. Now, Mason, that spanner of yours."

Blake worked away at the nozzle of the cylinder and screwed it off, but there was no hissing escape of gas.

He waited a few minutes, and then bade the men up-end the thing over the empty bath—an order they obeyed with some difficulty, for it was a heavy weight to manipulate.

No sooner had they lifted it, however, than a greasy, viscid liquid oozed out, and then began to run more freely, and with a rush there followed a veritable spout of gold coins.

The three men—captain, purser, and Bank official—leapt to their feet with a shout, and the two stewards nearly dropped the cylinder.

Blake alone seemed quite unperturbed, and chuckled at their amazement.

"There's the second half of my promise carried out!" he said. "In those four cylinders, I fancy, you will find the whole of the missing specie."

"Mr. Blake," said the captain, pouring himself out a two-finger peg. "I drink to your health. I don't mind owning up when I'm in the wrong, and 1 confess right here that till now I didn't for a moment believe you'd do any good. I reckon Rockall Holme will do the handsome thing by you over this. But for pity's sake give us a glimpse behind the scenes. In plain English, how the dickens did you manage it; what breed of magic do you keep on tap?"

"Common-sense," said Blake drily. "You remember I stood by the rail watching the passengers both arrive and depart, and you know that gold in bulk weighs a deuce of a lot.

"The moment I knew that the specie had been tampered with, I also knew who had done the tampering, and how the gold had been taken off the ship under our very noses; and what's more, I had a very shrewd suspicion as to the method of getting at it.

"Now, you come below for a moment. We can empty the other cylinders later."

He led the way to the professor's late state-room and switched on the light.

"You recollect that I asked you, Mason, for the plans and the passenger list. When I did so I knew that Mortimer was the thief—he and his pretty wife between them. A glance at the list showed me that they had one of the four cabins backing on to your precious strong-room. This is the wall here. Now, I shrewdly suspect that Mortimer has been planning this coup for weeks. The papers were full of the specie shipment, and the engineering papers had complete plans of the ship, showing every detail.

"He got wind of Mason's ruse, and where the gold was actually going to be stored, and after studying the plans of the ship carefully, he chose his state-room.

"I expect I am right in saying that he booked early and inspected his rooms in person before settling on them definitely."

"Quite right," said Mason, nodding. "And a deuce of a nuisance I thought him, I recollect."

"Very well, then, look here," continued Blake.

He went to the wardrobe which was clamped against the wall and opened the swing glass door. It was empty, and there seemed nothing special amiss with it.

Blake inserted his penknife, and the thin back-board of the cupboard fell forward, revealing the painted iron plating of the bare wall, riveted with big, round-headed bolts.

Into one of these he drove the point of his knife—it was wood.

"Now do you begin to understand?" he said. "The man laid his plans, and his pose of lecturer gave him just what he wanted. To have got the gold away in any quantity in ordinary luggage would have been quite impossible—the weight would have aroused suspicion.

"The only possible way in which it could be taken off was in those cylinders. I realised that at once. Mason here nearly upset the whole gamble by refusing to let him have them in his state-room.

"But the man was smart enough to give that lecture and make it an excuse to get hold of them.

"Having done so, he and his wife worked away through the nights and fused out the bolts with an oxyhydrogen flame, having previously unscrewed the back of the wardrobe.

"Then they removed one small plate and set to work on the specie. They couldn't take much, but they took all they dared.

"See here again. I found these flakes on the floor under the sofa, there—flakes of gelatine. He used a lot in preparing his films and slides, but he used a precious sight more in melting it down in hot water and filling up the chinks between the coins in the empty cylinders so that when it set solid they couldn't rattle.

He had some dummy wooden bolts ready and a pot of paint mixed with a lot of driers. As soon as the robbery was complete they just jammed these into place and chucked the real remnants of bolts overboard.

"It was a clever piece of work, and you can see for yourselves there is scarcely a sign of anything having been meddled with.

"If they hadn't forgotten the detail of the string on the crates I fancy the Bank would have signed a receipt in full, and it might have been a month before the fraud was discovered.

"Having got so far, it was easy to find that the professor and his wife had booked rooms at the Holland House, and inquiry showed that he and his cylinders had left ostensibly on the noon express to give a lecture the next day at Chicago—leaving his wife behind.

"I cabled and discovered that neither professor nor cylinders had gone on the train, and, moreover, I didn't expect they had, for the man could have had hardly a wink of sleep for three nights.

"The method—all first-class criminals have their own methods—struck me as very like those of a man called Simpson, so I 'phoned to the police for a description of the fellow, who is badly wanted by them on several counts. They sent me a description and a photograph.

"I had never seen the man himself, but the moment I set eyes on his picture I knew that Simpson and Mortimer were one and the same, in spite of the professor's whiskers.

"I know my New York pretty well, and I knew that Ling Foo's opium joint had a private entrance, and is extensively used by swell cracksmen as a good place to lie up in.

"Especially in a case like this, where the man must have been sick with want of sleep, and was known, according to the police, to be an occasional victim to the opium habit.

"A little questioning elicited the fact that a cart had pulled up at Ling Foo's shortly after noon, and some men had carried several heavy objects into the house.

"Then I knew that I had located our friend, and came back on board to fetch Mason just about half-past ten.

"As for Ling Foo and Simpson (or Mortimer), the police will take them and say thank you, whenever you like. Both are wanted on several counts, and nothing need come out about this little affair.

"The fascinating Mrs. Mortimer is asleep at the Holland House, and I've a man watching her. And now, as it's past two, and I've had a pretty busy evening of it, I think I'll say good-night and turn in for a bit of sleep myself."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.