RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

BLAKE read the crumpled wire in his hand for the third time with a thoughtful frown.

He could not make out what sort of a case it could be which the wire requested him to take up so urgently.

In fact, he was in doubt what to do about the whole matter. The sender was the Mother Superior of the Convent of St. Agnes, and she implored him to come at once on a matter of vital importance, but gave no details, nor so much as a hint of what the business requiring his presence might be.

The convent was in an out-of-the-way corner in Suffolk, far from a railway station, and he would be compelled to waste the better part of the day getting there, and the same returning; and he was, as it happened, overwhelmed with work just then.

After a little further thought, he sent back a reply that he would arrive as soon as possible.

Closing up the threads of some other urgent affairs delayed him in town that day, but early on the following morning he was on his way to Ellingham, a tedious, cross-country journey, mostly by slow local trains, which crawled along at a maddeningly slow pace.

St. Agnes' Convent is a magnificent building, standing back from the road in its own grounds, about ten miles from Ellingham, the nearest station.

He drove up in a ramshackle cart, and, bidding the man go to a small inn they had passed half a mile back and wait for him, rang at the entrance gates.

He was evidently anxiously expected, for without the slightest delay he was shown into the apartments of the Mother Superior.

She was a woman of scarcely more than forty, extraordinarily handsome, and with a strikingly dignified manner.

"Mr. Blake?" she asked.

Blake bowed.

"It is good of you to come to us in our distress. In fact, I had almost said our despair. The convent has suffered a terrible loss. The safe, where all our greatest treasures were stored, has been broken open, and a jewelled monstrance, worth over nine thousand pounds, has been taken. But the most terrible thing of all is that——" She paused.

"Perhaps I had better leave that till later, and tell you the details from the beginning."

Blake nodded. "I fancy that would be the best. Afterwards, I will ask you about any points which don't seem quite clear."

"To begin with, then, you should know, Mr. Blake, that ours is a very wealthy convent. Many who join us have considerable dowries, and some almost historic jewels.

"The money they dedicate to the convent treasury, but the jewels are given for the adornment of the vessels used in the chapel. You can readily see that in this way, as the years go by, the plate, and so forth, used for the high altar on feast days, has become of almost priceless value.

"It is most carefully kept in a specially-built safe in a small room adjoining the chapel entrance. Of this safe, which has two keys which must be used in combination, I hold one, and the Sister, whose turn it is to take charge of the chapel for the fortnight the other.

"It is vacation time here now, of course, and no one has had occasion to go to the safe for three weeks or more till yesterday, when I wished to put away some jewels which had just been handed me.

"Imagine my horror and dismay when, on going to it, a glance sufficed to show me that it had been broken open. A hurried inspection soon showed that a few large stones had been roughly picked cut from some of the vessels, and that, worst of all, a superb monstrance—worth, as I have said, some nine thousand pounds—had been stolen."

"Could you give me a description?" asked Blake.

"It was eighteen inches high, with a cross composed entirely of big diamonds at the top. The front, back, and sides were of beautiful deep blue enamel work, set in carved gold frames, and encrusted with designs in large pearls, emeralds, and other precious stones.

"In the centre of the front panel was a magnificent cabochon ruby, oval-shaped, and one inch and a quarter long, set in brilliants. It had once been a brooch, belonging to the Richelieu family, and was made, I believe, by the same jewellers who made the famous necklace for Marie Antoinette.

"It has been in the possession of the convent now for nearly two generations. Though we are cut off from the world here, I still have many dear friends with whom I correspond, and from one of them I hoard of your wonderful doings.

"Our sole hope is in you, Mr. Blake, for above all things I wish to avoid a scandal, and I fear a scandal there must be if we were to inform the police. You yourself are, I feel sure, the soul of discretion."

"Any secret I find out will be perfectly safe. I gather from what you say that you suspect someone, somebody in particular."

The Mother Superior hesitated.

"To be candid, I can't help myself. Suspicion is forced on me," she said. "The monstrance, you must know, is not the only thing which has vanished from the convent. With it has gone one of our guests, a girl for whom I had a great affection. You are probably aware that from time to time we offer the protection of the convent to those who from one reason or another may need it. They are free to come and go as they like, and may receive their friends. In short, they are guests simply.

"We had one such till sometime on the day before yesterday—a Miss Molly Thersiger. She had been educated here formerly, and left us. A month or so ago her father, Major Thersiger, was ordered abroad. She has no mother, and she was put in our charge until his return. I did not discover the fact that she was missing until after the loss of the monstrance. A search was made, and it was found that her bed had not been slept in the night previously, and that she had vanished. But, worst of all, in her room was found this, hidden behind a cupboard."

The Mother Superior opened the drawer of her secretaire, and held out an object, which glittered in her slim white fingers.

It was the cabochon ruby set with brilliants.

Blake eyed it narrowly. It had clearly been but lightly set in the enamel, and little or no force had been wanted to free it. At the top was a small loop, set with a single diamond, enabling it to be worn as a pendant.

"It certainly is a remarkable piece of evidence," he said thoughtfully; "but why should she or anyone have hidden it in about the last place in the world where they could have got it again with safety."

"I used the wrong word when I said 'hidden,'" replied the Mother Superior. I should have said it was concealed. For myself I came to the conclusion that the unfortunate girl, having wrenched it loose, had laid it on the cupboard, and in the flurry and anxiety of her flight accidentally swept it aside, and it dropped between the cupboard and the wall."

"That is more probable," said Blake slowly. "What type of girl is this Miss Thersiger?"

"She is just twenty years old, with dark hair, and extremely pretty—quite exceptionally pretty—a little wayward and impulsive, easier to lead than to drive; but if she had a fault she was possessed of an almost morbid passion for jewellery. I don't mean for the sake of vulgar display, but pretty stones seemed to fascinate her, and she would finger them and handle them by the hour together.

"Major Thersiger is an extremely wealthy man, and the girl herself has a good allowance—too liberal, if anything. I can only explain her action by this fascination, and a sudden yielding to temptation."

"I should like, if possible, to see the safe, and also the room which Miss Thersiger occupied," said Blake.

Under the circumstances, the whole convent is open to you, Mr. Blake. I should add, though, that I can give you my personal assurance that there is no one else amongst us who could have any connection with the—the theft. All of us in the building now are members of the convent of many years' standing, and have no longer any personal property of our own, or use for things of value."

The Mother Superior led the way to the small room in which the safe stood, and Blake examined it carefully.

As he had half expected, it was a flimsy affair, at which any expert would have laughed. It looked solid and massive enough superficially, with its green paint and its big brass handle; but it was of an old pattern, and the locks were of the simplest.

The door, too, was not solid, but consisted simply of iron plates, with the space between filled with packing.

The opening of it had been easily accomplished by the use of a small drill and a chisel, or similar implement.

The window of the room was strongly barred, and would have taken at least an hour's hard filing to break through. The lock of the room-door, however, again quite a common sort, had clearly been picked in a rough-and-ready fashion.

The Mother Superior led him down a corridor to where the guest-rooms were situated. These were on the ground floor, and the windows which looked on to the garden were unbarred. At the third room they stopped and entered.

"This was Miss Thersiger's," she said, "and there is the exact spot where I found the ruby."

Blake glanced round him. "Has anything been touched here," he asked.

"Practically nothing. I gave orders that it was to be left undisturbed till you came."

The bed had clearly not been slept in; there were ashes in the grate, and the room was in some disorder. An open wardrobe showed that the girl in her flight had left nearly all her things behind her.

"Can you tell me what articles are missing?" said Blake.

"So far as I can say, she must have left nearly everything except the clothes she stood up in, a fur-lined travelling ulster, and a hat. Her purse, too, is gone. She always carried a fairly large sum of ready money, and intended, I suppose, to buy things on her way as she needed them. Curiously enough, though, she stopped to take her dressing-bag—rather a large one—but left the fittings."

Blake raised his eyebrows. "Large enough, by any possibility, to carry the monstrance?"

The Mother Superior gave a low cry. "I never thought—— Yes, it would have been; and the weight would not be too much, for she was a strong girl and fond of outdoor sports."

Suddenly Blake gave a sharp exclamation and took a step forward. Near the window was a small plain, deal table, and on it an assortment of small tools and scraps of metal filings.

In a drawer lay an unfinished piece of metal and enamel-work and right at the back, hidden away in a corner, a chisel of stouter make. He held out the unfinished piece of work.

"Who did this?" he asked gravely.

The Mother Superior smiled a little sadly. "Molly Thersiger herself. It is good work, isn't it. It was her great hobby; she has shown at exhibitions very successfully. It was her idea, she told me, to make us some small object for the chapel as a souvenir of her stay, and she wished to do her very best."

"Anyone who could do half as well as this would find no difficulty in opening your safe," said Blake. "And besides, look at this; take my lens, please, you will see more clearly."

He handed her the chisel. Its edge was ragged and blunted, and on the back and sides of the steel were smears of green paint—the paint of the safe-door. He picked up the small metal-worker's drill—that, too, was in the same state.

He laid them down with a sigh and continued his search. In the grate were charred ashes of paper evidently torn up in haste. As often happens, words can still be read sometimes on burnt paper with ease. The third piece which Blake examined—a mere tattered fragment, bore faintly but distinctly the words:

"I send you a ruby pendant for——" The paper ash was broken off at that part; lower down came another incomplete line:

"I leave for the Cont—they catch me."

He pointed to the words. "Do you recognise the writing?" he asked.

The Mother Superior gave a quick gasp. "It is hers," she said in a low voice. "Mr. Blake, whom can she have been writing to in that fashion? Can someone—some unscrupulous person—have got hold of her and deliberately lured her into doing this?"

Blake crossed to the window, opened it, and looked out. It was barely five feet to the ground. On a rusty nail in the sill was a shred of grey tweed cloth of the kind used in making country skirts. Below in the flower-bed was a distinct imprint of a woman's shoe. He compared it with one by the wardrobe. A glance was sufficient. "1 have learnt all I can here," he said, "and time presses. I will wire to you the moment I have news. I will leave by the garden, if I may."

Blake's great desire was to get away by himself and think. He had never had a case quite so much to his dislike. Against his ordinary rules he had formed a theory, and was conscious of a prejudice, and yet the further he went into matters the more every fact and particle of proof told in the precisely opposite direction.

He wished to find and prove Miss Thersiger innocent, yet at every step he took he found fresh and incontrovertible evidence against her. Even as he scaled the low convent garden wall, instinctively following the route he felt she must have taken in her flight, he came upon a fresh clue.

He had almost unconsciously been scanning the surface of the old wall for any sign of a brick with a chafed edge, or a crumbling piece of mortar to show where anyone had scrambled over before and sure enough a little way to the right he found it. What was more, he found that the place had been used not once nor twice, but several times, and under a bush close by he discovered a rain-sodden handkerchief bearing the initials, M. T.

It had rained a little after midnight on the night preceding the discovery of the theft, and there had been no local rain since. Clearly, then, Miss Thersiger had made her escape before or about that time, and, equally clearly, she had on several occasions made use of that surreptitious mode of exit from the grounds.

He had brought with him from the convent a photograph of the girl herself for identification purposes, the paint-smeared chisel and drill, and the shred of tweed. He went to his own room at the inn and spent a quiet hour thinking over the case.

Twist it which way he would there was no special light on it. Every fact seemed to point directly to the girl's guilt, and yet Blake felt that if she was guilty, at any rate she must have had some good sound reason for her actions, and that the motive was an unselfish one.

At last, in despair, he gave up all further attempts, and went downstairs into the public rooms. He sat there glancing over a paper and listening casually to the village gossips talking over their pipes and beer.

He was not purposely paying any heed, but long practice had made him accustomed to remember any stray sentences uttered in his presence, and he had found it useful more than once before.

On this particular occasion it served him, too, for, having semi-consciously received the intelligence that Mrs. Wiggs had had a bad go of rheumatism, and that Sophy Rain's behaviour was no better than it should be, and that the local blacksmith had come on hard times and was leaving almost at once for "furrin parts," he learnt incidentally that the loss at the convent was well known, and that the fame of the monstrance and its tremendous value was a current topic.

He had smoked out his pipe, and was thinking of going up to turn in and ponder over the problem, when there came a clatter of hoofs outside, and the inn-door was burst violently open.

The new visitor was a young man of about seven-and-twenty, and he was obviously excited. Good-looking and well-dressed, he had evidently been riding hard, for he was splashed to the eyes with mud, which, to Blake's mind, argued that he had come some considerable distance, as no rain had fallen during the day, and the roads locally were dry. He glanced neither to right nor left, but strode straight up to the bar and demanded a double portion of whisky and a small soda. The barman served him with alacrity, evidently knowing him by sight.

The young man tossed off the drink at a gulp and demanded another of the same kind. Blake, peering over his paper, raised his eyebrows in surprise, and whistled softly to himself. He was a good judge of character, and was ready to wager that the youngster so close to him was no drinker.

He had a fresh, sun-tanned complexion, a clear eye, and a steady hand, and yet he was drinking the equivalent of four whiskies in half as many minutes.

Clearly something of importance had occurred to throw him momentarily off his balance, yet the square chin spelt resolution and self-control, and the reason for his temporary loss of will-power must have been a strong one.

As was only to be expected, the unaccustomed dose of alcohol made his already excited brain muddled a little.

He muttered angrily to himself, pulled from his pocket a piece of paper, read it several times a little unsteadily, and then, with an angry gesture, hurled it erratically at the open hearth near which Blake was sitting, and throwing a couple of florins on the counter, flung out of the place without speaking to anyone or waiting for change.

A moment later Blake heard a "Come up, you old brute!" and a splutter of hoof beats growing fainter in the distance.

"Young Mister Bourne, 'ee do seem in a fine tantrum!" said one of the yokels, grinning. "Niver did Oi zee un take 'is liquor the loikes of that afore! Reckun 'ee's bin backin' t' wrong 'orse again."

Blake sat straight in his chair still apparently studying his paper, but one long leg shot out, carelessly to all seeming, and his foot covered the crumpled scrap of paper so recklessly thrown aside.

Watching his chance, he snatched it up deftly and opened it out. It was a foreign telegraph form, typewritten as usual on thin strips of blue paper affixed to the form itself. It ran:

CYRIL BOURNE, THE TOWERS, ELLINGHAM.

HAVE ARRIVED. DO NOT ATTEMPT TO ANSWER LAST COMMUNICATION.

FINAL. M.

The despatch had been sent from Middleburg, in Holland, and there was no doubt that the signature of "M" stood for Molly Thersiger.

That was Blake's first clue to the story which lay behind.

"Who was the gentleman who just came in and went, out again in such a hurry?" Blake asked the man behind the bar.

"Young Mr. Bourne, sir, from Ellingham. He seemed mighty upset about something. A bit wild and high-spirited. He and Sir Philip—that's his father—and his elder brother do have terrible rows at times, they tell me; and Sir Philip has sworn to turn him out of the house."

"Dear me! Whatever for?" asked Blake.

"Well, sir, Mr. Cyril he likes a bit of a flutter on a horse, and he's lost a power of money one way and another over the races."

"Ah!" said Blake. And just then a new set of customers came in; and he buried himself once more in his paper, but both eyes and ears were on the alert.

If Cyril Bourne were hard-pressed for money, and Molly Thersiger was in love with him, that put a new complexion on matters. That the man was naturally a nice, straightforward fellow, he felt convinced; but bitter experience had proved to him over and over again that the gambling instinct, a hot temper, and love combined, had ruined many a man—and woman, too—whose instinct was to run straight.

He rose at last, and went to his room to turn in, for he meant to be in Harwich early in the morning.

It was clear enough that, innocent or guilty, Miss Thersiger's one desire had been to get right away as quickly as possible. Harwich was the nearest port, and boats ran constantly from there to Antwerp, with Holland just across the river, and Holland, as everyone knows, is the best country for the disposal of valuable but doubtfully-owned stones.

He rose early, and hurried the pony and trap down to the blacksmith's to have a loose shoe put right, and he leant against the wall of the forge smoking a cigarette whilst it was being done.

The first thing which he did on arriving at Harwich was to send a long cypher wire to a friend of his—a Mr. Dove—in town.

At Flushing—the Harwich boats run to Antwerp —he got taken off in the pilot boat, saving himself the tedious journey round by Rosendael, and took the light railway to Middleburg.

Before he had been in the town half an hour, making a few cautious inquiries, he turned the corner into the market square and came face to face with Cyril Bourne.

A very different Cyril Bourne, though, from the young, spruce-looking man he had seen a day or so previously. He was haggard, unkempt, and unshorn. His red-rimmed eyes told their own tale of dire want of sleep, and his face was drawn and haggard by some deep-rooted anxiety.

He did not know Blake by sight, of course, and the latter had no difficulty in following him unperceived.

In a short time, however, it became very evident that though the young man was searching for the missing girl, he had no notion of her whereabouts, and very little of his own, for he repeatedly wandered back over ground which he had covered before in an aimless sort of fashion.

At last he turned into a café on the quay, and chiefly by signs ordered himself a roll and coffee.

Blake took a seat at the next table and gave his own order in Dutch. Then pretending to search through his pockets for something he gave a hasty exclamation in English.

The younger man turned sharply.

"You are an Englishman, sir! Thank goodness! I hope you will be kind enough to help a fellow-countryman, as I notice you can talk this infernal lingo. I have come over here on most urgent business—a matter of life and death; and I can't make anyone understand a word I say. My name is Bourne, and I came from Suffolk, via the Hague, yesterday."

"I shall be delighted," said Blake civilly. "I myself only arrived from there this morning. Now you mention it, I fancy I saw you in a small inn where I was staying—near the Convent of St. Agnes."

Bourne leapt in his seat.

"You did! But this is a most extraordinary coincidence! For I am looking for—for a very great friend of mine who left the convent unexpectedly. She is here somewhere alone, and I'm afraid she must be ill or upset."

"I am also looking for Miss Thersiger," said Blake quietly.

"Good heavens, man, what do you mean? What have you got to do with her? I am over here on behalf of the Mother Superior of the convent to try and persuade the young lady to return. But have you found her—quick, man alive, can't you speak?"

Blake smiled.

"I have not found her. I hope to, though I am beginning to suspect that she is a much cleverer young lady than I thought at first—and a very brave one. Mr. Bourne, if you will kindly tell me your version of the matter, I shall be much obliged, and probably far more able to help both you and her. My name is Blake—Sexton Blake, and I assure you I have Miss Thersiger's welfare at heart."

"Are you the man one is always reading about in the papers?"

Blake nodded.

"I am the individual whose business it is to know things. I know, for instance, that you and Miss Thersiger are practically engaged."

"Were," corrected Mr. Bourne, with some bitterness. "Look here, I'd better tell you the whole story, and if you can make head or tail of it, it's more than I can.

Miss Thersiger and I have been practically engaged for a couple of years, but she happens to be an heiress, and I'm a stony-broke younger son, and the thing couldn't go any further till I got a job of some sort, for I won't live on her money, and my own allowance about pays for my washing and tobacco.

"Well, this was an understood thing, though she kept on pressing me to take part of what belonged to her, which was out of the question. I used to go and see her at the convent, and—well, it's no use giving you half the truth. I used to see her as well when the nuns weren't about by clambering over the wall and talking to her through the window."

Blake laughed softly.

"That explains it," he thought.

"Well, we were as jolly as sandboys," proceeded Mr. Bourne, "barring the fact that my job didn't seem to be over easy to get, until four or five days ago, when I happened to see in a village jumble curio shop what looked like rather a pretty sort of toy-jewel—not valuable, you know, but quaint.

"Molly is awfully fond of jewels and old things, so I hopped off my pony and asked how much it was. The old chap in the shop asked me fifteen bob for it. It seemed a good lot for a bit of coloured glass. Still, that didn't matter if it happened to please her, and I bought it. The chap told me a rigmarole about the baker's boy having picked it up in the road and asking him half-a-sovereign. That was all rot, though, for I met the boy later, and the man had palmed him off with a florin.

"To cut the story short, I wrapped it up in a note and sent it to Molly.

"Now this is the extraordinary part. The very next day I got from her a long incoherent letter, asking me how could I have done it. Said she had been nearly driven out of her mind, and was returning it—whatever it may have been, I don't know, for she returned nothing—and that I must never see her again.

"Of course, I saw that something serious had happened, and rode off posthaste to the convent, only to be told that she had left hurriedly. I-was flabbergasted, as you may imagine. But the evening before last I received a cablegram—from here, of all beastly places in the world—saying: 'Do not attempt to answer. Final.'"

Blake chuckled.

"I suppose you don't happen to know that that stone which you sent her, and bought for a few shillings was taken—or, as a matter of fact, was accidentally knocked out of the monstrance of the convent, which has been stolen—and was worth probably close on a thousand pounds."

"Good gracious!" said Bourne. "Do you mean that really?"

Blake nodded.

"But then I—she—You don't mean to say that she thinks I stole it?"

"I expect she had a very definite reason for whatever she did think," said Blake gravely. "And now, if you will promise to wait here for—say, a couple of hours or so—I've no doubt I can put matters straight."

Blake was well known to the Dutch police. And the registration of visitors being strictly enforced, a few inquiries over the telephone soon elicited the fact that a young English lady, corresponding exactly to Miss Thersiger's description, had arrived at Middleburg, with only a dressing-bag for luggage. And had, after spending one night at the Couronne gone on to the small village of Veere, six miles away—an isolated-looking little spot by the banks of the East Scheldt.

Blake had previously sent a cable to Mr. Dove, and, before the two hours were quite expired, had received a curt answer in cipher which evidently pleased him.

Two minutes later he and Mr. Bourne were driving up the straight road to Veere. The only response Blake made to the latter's questions was "Wait and see!"

Arrived at the inn, he bade his companion stop below in the carriage whilst he went inside. A moment's conversation with the landlord set matters straight, and he went upstairs as he had been directed, and tapped at the door of a small but clean sitting-room.

"Come in. Entrez!" said a listless voice. And Blake entered.

Miss Thersiger—for it was she—sprang to her feet, her face as white as a sheet.

"What do you want?" she asked sharply. "You are an Englishman?"

"Yes, Miss Thersiger," said Blake. "I want you to come back to England with me."

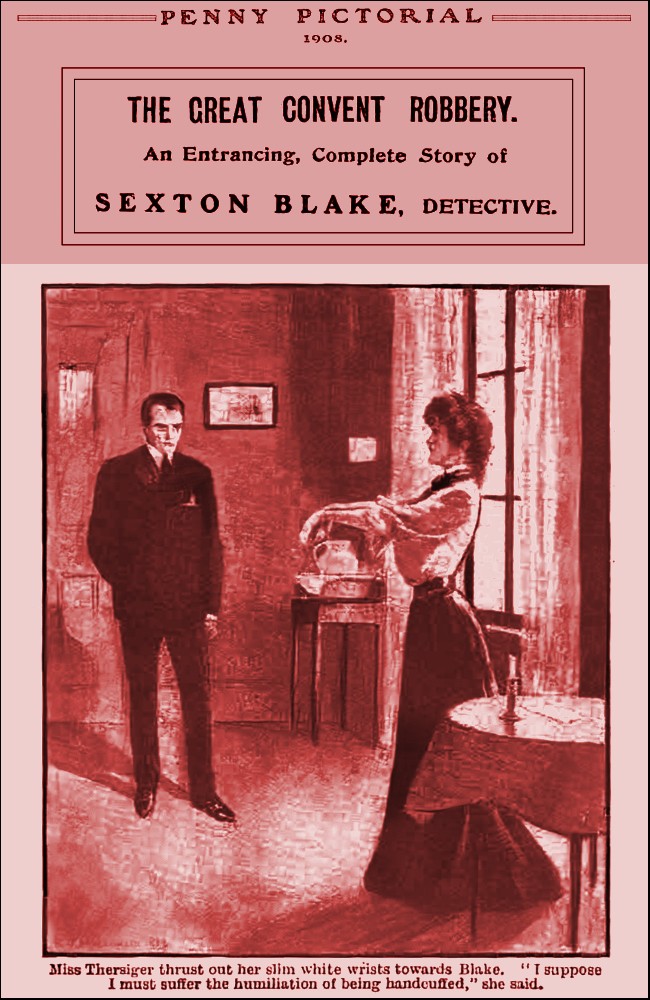

A violent fit of trembling seized her, and Blake was afraid for the moment she would fall, and took a step forward. She shrank back, and then of a sudden threw up her head, eyeing him defiantly, and thrust out her slim white wrists towards him.

"I will come," she said. "Do your duty quickly. I suppose I must suffer the humiliation of being handcuffed."

Blake shook his head smilingly.

"There is no need," he said. "I am only here to act as your courier. Meanwhile, here is some good news for you. See, this is a cable I have just received from England. I will decode it for you." And he held out a slip of paper which he had kept concealed in his hand behind his back.

"This is how it reads: 'Blacksmith arrested. Monstrance safe.—Dove.'"

Miss Thersiger put her hands to her face with a low cry.

"I don't understand! What does it mean! I thought you had come to arrest me?"

"Not at all. The guilty man has already been arrested, and Mr. Bourne had no more to do with the monstrance than you yourself."

She stared at him with horror-struck eyes.

"But—but the ruby! How could he—— Besides, I—I saw him the night before—I saw him with my own eyes!" she moaned.

"Or thought you did," said Blake. "And bravely and generously tried to mislead everyone into thinking you had taken it. I think I can explain to you exactly what happened.

"You received the ruby by post from Mr. Bourne, and at once recognised it as having been taken from the monstrance. In an agony of fear you rushed down and found that the safe had been tampered with.

"Mr. Bourne was in the habit sometimes of climbing over the convent wall, and bidding you good-night outside your window. Probably on one occasion you were expecting him, and you saw the figure of a man going away or moving about in the darkness. You may even have called to him, being sure that it was Mr. Bourne, and got no answer."

She nodded.

"That is so. I called him softly, and he did not hear me. It struck me at the time that he seemed to be carrying something, and I thought it strange."

"Exactly. And knowing that Mr. Bourne was in financial difficulties, and remembering what you had seen, you lost your head, and jumped at conclusions in a state of panic.

"Then you forced yourself to think, and resolved to try and shield him. You smeared your metalworking tool with the soft paint of the safe, and left them where they could be found, and you left clues where they might most easily be seen. That in itself made me suspicious. And you wrote two letters to him intending to return the ruby. The first letter you burnt, and the second, in your excitement, you closed without inserting the ruby, which had dropped behind a cupboard. As a matter of fact, the real thief had also dropped it in the road previously, whilst making his escape.

It was picked up by a boy, and Mr. Bourne bought it, not knowing its value, for a few shillings. What really happened was this. The man you saw that night was not Mr. Bourne, but the village blacksmith. I heard accidentally that the local blacksmith was in a poor way, and was shortly going abroad. I also heard that the value of the monstrance was well known. Now a glance at the safe had told me that although whoever had done it had a knowledge of metalwork, it was certainly not the work of an expert thief.

"I was sure it was done by some local person accustomed to handling metal. In that sparse district, a stranger would be sure to have been noticed. I thought I would have a look at the smith, so 1 loosened my pony's shoe overnight, and went down to the smithy in the morning. I saw at once that the man was doing a good trade, so the story of his difficulties was a sham. And I also recognised the man as having been a hanger-on of a third-rate gang of thieves some years ago in London.

"To enter the convent by any of the guest-room windows would be child's play. The man got the monstrance, and in his hurry must have knocked out the ruby pendant, which was weakly set. I said nothing, but I wired to a friend of mine to keep an eye on the smith. Then I came over here. I wired to have the man arrested as soon as I had heard Mr. Bourne's story, and it has been done."

"Mr. Bourne! Is he here? Oh, how can I dare face him after what I had suspected—after what I thought I had seen!"

Blake smiled.

"I don't think you will find it very hard, Miss Thersiger. From what I have seen of the gentleman, he is badly in need of a kind word. I will leave you to explain matters together. For he's down below, and I'll send him up.

"Later, you must both come back, and we'll have a comfortable little dinner before catching the boat. So don't make the explanations too long."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.