RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

BLAKE was just emerging from one of his occasional rest cures—in other words, from five days' absolute idleness, in which he had done little else than stare at the ceiling—when he heard a ring at the door bell, to which he paid not the slightest attention.

His mind was occupied with a neat little problem in thermal activities, and the last thing on earth he desired at the moment was to be pestered by a visitor or a client.

The bell rang again and again, and with each successive peal the ringer grew less timid or more desperate. Blake gave an exclamation of annoyance, and threw up the window.

"Go away!" he called tartly. "I am busy! I can't attend to you now. Oh! just my luck!" he grumbled to himself. And then again out loud: "All right, I'll be down in a minute!"

He had caught sight of a woman waiting on the doorstep below, and Blake made it one of his rules never, if he could possibly help it, to refuse assistance to a woman-old or young, rich or poor. He would send, and frequently had sent, a distraught financier away with a few curt, blunt sentences, and refused to touch his business on any terms whatever, unless he was in the mood.

The woman below, as he had seen by the flickering light of the street lamp, was obviously poor, young, and not bad looking, though her face was drawn with anxiety.

He hurried downstairs, and opened the door.

"I beg your pardon for keeping you waiting," he said. "I am afraid you felt it very cold there. There is a fire in the room above."

The woman thanked him with a glance, and, with a slight shiver, preceded him up the stairs. In spite of her poverty-stricken appearance she was obviously a lady, and on closer view Blake noted that her eyes were more than usually pretty, with long sweeping lashes showing dark against her pale cheeks.

He glanced at her quickly again as they entered the room, and read in those same cheeks a tale of insufficient nourishment, semi-starvation, and grief, or mental strain of some sort, had brought her near the end of her strength.

Blake pushed forward a chair to the fire, and rummaged amongst an untidy mass of litter in a cupboard. At last he discovered what he was looking for—some cake and a bottle of port. Glass there was none, so he took a clean beaker from his laboratory bench, and set the things on a table by her side.

"You must forgive the shortcomings of a bachelor's establishment, Mrs.—"

"Errington," she said, in a low voice.

"Mrs. Errington. Thank you. The glass is a bit unusual, but the wine will keep the cold away. The cake was, I believe, once fresh; but it has seen its best days. I'm afraid I'm rather neglectful in these matters. Please make the best of things, though, and when you have finished be sure I will help you in any way I can." And he turned away, pretending to busy himself with a test-tube stand. He had seen the almost wolfish gleam in her eyes as she saw the food, and did not want to embarrass her.

After a little while he turned his head, and it was as much as he could do to repress an exclamation of horror. The wine by her side was barely touched, but the cake had vanished to the last crumb. And Blake, who knew that it must have been stale and almost uneatable, saw that the woman must have been a good deal nearer starvation than he had suspected.

But she was quick, and must have read something of his thoughts in his face. She glanced down at the table, and a wave of crimson passed over her pale face. It was as though she had only just realised what she had done.

"I am sorry," she said, half ashamed, half defiant. "But do you know that that was the first morsel of food I had tasted for two days. What is it? Where are you going?"

Blake was already struggling into his coat, and hunting for a hat or a cap.

"Where am I going?" he grunted angrily. "To the nearest restaurant, to get in a good sensible meal instead of that infernal—I beg your pardon!—that cake, You're not in a fit state to be out on a night like this, much less to talk business."

She laid a hand on his sleeve. "No, no!" she cried. "I am better—really ever so much better! And I have far more important things on my mind than mere hunger and physical discomfort. Please take your coat off. I am quite strong again."

Blake grumbled, but obeyed.

"Mr. Blake," she went on, "you have already shown me kindness. I want you to show me a far greater one. I came here to-night pretty well hopeless, for I have no money—nothing to offer you, and I have heard you spoken of as a hard man. Now, I know that the people who spoke so of you said what was not true. Mr. Blake, if you want to save me from the river or a pauper lunatic asylum, find my husband for me.

"No, don't interrupt; let me tell the story in my own way. I have thought it over carefully, and will spare you all unnecessary detail.

"My husband, Charles Errington, is a chemist and a scientist of no mean order. We have been married three years, and were—are—devoted to one another; although even from the start we were miserably poor.

"Eighteen months ago my husband got an appointment as confidential secretary and laboratory assistant to Dr. Rathbone.

"You have heard of him probably? His name has an almost European reputation in the scientific world."

Blake nodded, and she went on.

"He is eccentric. I believe he suffers from some disfiguring skin disease, which becomes aggravated at times, and therefore lives the life of a recluse in a big house, with a high-walled garden, near Putney. All his discoveries and his original research works are communicated to the outside world in writing. He himself never mingles with his fellows. He is rich; but my husband told me that he is a bit of a miser, and nothing pleases him more than to make money by his researches.

"Charlie's work as his assistant was arduous, but he liked it; and at any rate, it secured us an income of a hundred and fifty pounds a year.

"Often and often Dr. Rathbone used to keep him there in the laboratory till three and four in the morning, and expect him to be back the next day before ten. I am not grumbling, but it is necessary that you should know the type of man Dr. Rathbone is.

"Last Monday Charlie went to work as usual. To-day is Friday, and I have never seen him since. On Tuesday, finding that he hadn't returned, I was naturally uneasy and alarmed; but I fancied that he had been kept at work so late that he had slept in the house, though he had never done such a thing before.

"But when Tuesday evening came, and he still failed to come home, I went straight to Dr. Rathbone's, and asked to see my husband. A foolish old woman who answered the door—the only servant kept—assured me that Charlie had not slept there the night before, and that she didn't believe he had been there that day either. I insisted on seeing Dr. Rathbone, and was shown into the laboratory. He seemed busy, and was excessively rude.

"He didn't even stop his work or turn round to speak to me, but just barked his answers to my questions, and finally ordered me out of the place.

"He said that Charlie had not been near the place since Monday morning, when he had gone out by the laboratory door to send a telegram ordering a fresh stock of certain chemicals; and that in consequence of what he called Charlie's abominable conduct, his work had been seriously hampered.

"Now, I am a pretty quick observer, Mr. Blake, and a woman's intuition often carries her far.

"I am certain—as certain as I sit here now—that the man was lying to me—acting a part and overdoing it. His very rudeness was exaggerated, and his voice was strained and harsh. He is concealing something, I am sure of it. He knows what has become of my husband, and he won't say. And it's that which makes me frightened, for I begin to imagine all sorts of horrible things."

"Have you seen the police?"

"No. I didn't want to. I have no proofs—nothing but the one fact. I can't openly accuse Dr. Rathbone of anything; and the police would treat it as an ordinary commonplace case of a man leaving his wife in the lurch and going off by himself. And that I couldn't bear, for a better husband than mine, or a kinder, no woman ever had.

"But I haven't told you all yet. The day after I called on Dr. Rathbone I received this anonymously by post."

As she spoke she held out a torn envelope of considerable thickness. Blake took it and examined the contents. There were eight five-pound notes wrapped in a sheet of blank paper.

He ran through the numbers, and jotted them down on the back of the envelope.

"I will keep these," he said, retaining the outer covering and the blank paper. "The notes you had better put in some safe place. Now, do you know what kind of a man this Dr. Rathbone is—any details, I mean?"

"He struck me as being a rather untidy, slovenly old man, with a mop of grizzled hair and a long, straggling beard, rather stout, and wearing big, round glasses. Of course, I only saw him once, and then in a bad light, and I was much upset. But sometimes Charlie used to make me laugh by taking him off in one of his tempers. He is a very good mimic. I believe he used to storm and rage and use the most horrible language. He is a tremendous pipe-smoker, and used to brandish his pipe in Charlie's face when he was particularly furious. At the same time, Charlie said he was tremendously keen on his work, and would talk about it for hours if he could get anyone to listen. But he is even keener on money. Charlie spoke to him some time ago about an invention of his own. He wanted him to take it up—as, of course, my husband was too poor to stand the expense himself. I have an idea that the doctor promised to do so—he thought very favourably of it. Mr. Blake—"

She paused, and seemed to find it difficult to say what she wanted.

"You mean," said Blake, helping her out, "that you can't help having a suspicion that some ill has befallen your husband at the doctor's hands, because the doctor was supposed to be very fond of money, and your husband had taken him an invention in which he believed highly, and that those notes were sent as, let us say, conscience money?"

Mrs. Errington gave a low cry.

"That is the fear I have been fighting against all through the long nights—the fear that has been haunting me. My husband has been overworking, and his health is not strong. The doctor's manner was so strange, and I am afraid that in one of his paroxysms of rage he may have done something terrible."

Blake glanced at his watch, and rose.

"I will go and see him this evening," he said. "A man of his type can scarcely object to late hours. Meanwhile, I may want to communicate with you in a hurry. Would you mind going for the night to this address? There is a very nice landlady there, who, if you mention my name, will do everything to make you comfortable. There is a telephone in the place, so that I can ring you up at any time. Stay there till you hear from me."

"Thank you!" she said, in a tired voice. "You are very good to me."

A quarter of an hour later Blake was hurrying Putneywards.

*

He found the house easily enough. It was barely eight o'clock, and a lamp burned feebly in the hall.

The old servant answered his ring, and promptly refused him admittance.

"The doctor don't see no one!" she snapped.

Blake slipped a coin into her hand.

"At least, you can take a name down to him if he is busy. Say that a gentleman from Herr Ludenoff would particularly like to see him."

The old woman looked doubtful and rather frightened. In the end, however, she came back after a few moments' absence looking obviously surprised.

"You can go down," she said curtly—"straight down the stairs, first door on the right."

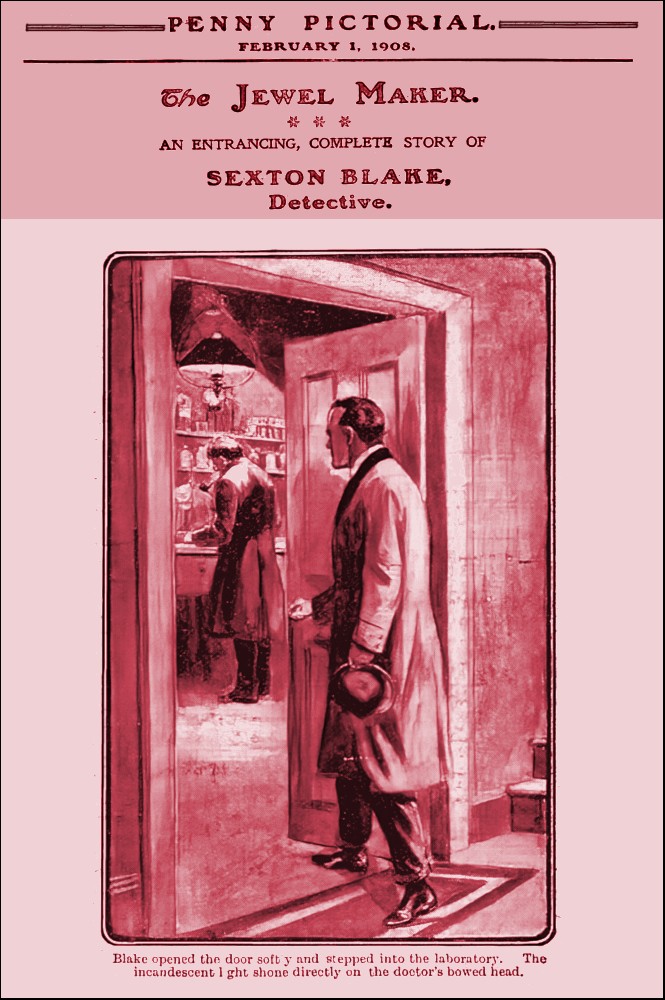

Blake nodded, and in a few strides found himself at the laboratory door. He opened it softly and stepped in. The place was in darkness save for one large, brilliant incandescent light, which shone directly on the doctor's bowed shoulders and shock head. Between his lips was a huge pipe, at which he was puffing furiously, and in front of him was a bench littered with retorts and crucibles.

He seemed to have forgotten his expected visitor, and to be immersed in his work. Blake walked quietly up to him and glanced over his shoulder. Rathbone's strong, skilful fingers were busy with the preparation of some delicate glass slides for microscopic work.

It was quite a full minute before he laid down a cleverly-prepared specimen and turned.

"Ah!" he growled. "Herr Ludenoff. I beg your pardon. I read your paper on the question of the cancer serum with much pleasure. I am at work, as you see, on some little experiments of my own which I should like you to see."

"I shall be delighted, Dr. Rathbone," said Blake quietly. "But I ought to explain that I made use of Herr Ludenoff's name—he is a great personal friend of mine—as a sort of passport to ensure getting to see you. As a matter of fact, my name is Blake, and in my own small way I have done a trifle in original research."

Dr. Rathbone frowned.

"Blake—hum—ah! Yes, I remember. I fancy you wrote a monograph on sleeping sickness, gathered from your personal observations when in Central Africa. Am I right? You see, I am a bit of a recluse, and see hardly anyone."

"Quite right," replied Blake. "It is an interesting subject which has hardly been touched on yet. However, I am really here to ask you a few questions about a young man called Errington, who, I understand, was your assistant, and who has disappeared in an extraordinary way."

Dr. Rathbone stiffened instantly, and his manner changed.

"In that case, I may say I consider this a most unwarrantable intrusion!" he declared angrily. "The fellow has probably made a fool of himself in some way. I don't go into the world much, but I know enough of it to know that young men generally contrive to do something idiotic sooner or later.

"This particular fool chose to do so at a time particularly inconvenient and annoying. He was here on the Monday. We were in the very thick of some most important experiments—experiments of which, I may say, I was expecting results of world-wide importance.

"I sent him out to despatch a telegram, and so far as I know he has not been seen since. I have washed my hands of him. What he has done or not done is no longer any concern of mine. I can waste no more time on the subject; the servant will see you out. Good-evening! And allow me to add that I consider your coming here an impertinence, and that I don't see what concern you have with the matter."

"Possibly not," answered Blake drily. "But Errington's wife came to me in great distress and asked my aid. I promised to do what I could. Dr. Rathbone, why did you send those anonymous notes?"

It was a chance shot.

Dr. Rathbone scowled through his glasses.

"Anonymous notes? Oh, I see! I may live the life of a recluse, but that doesn't necessarily mean that I am dishonest. When the young fool chose to take himself off it so happened that there was a quarter's salary due to him, and, knowing that he was married and as poor as a church mouse, I stuck some notes in an envelope and sent them oft to his wife. As for their being anonymous, as you call it, it is explained by the simple fact that, having sent the money, I did not feel called upon to take the trouble to write a letter. So have the kindness to go and meddle with what doesn't concern you somewhere else."

The man's manner was genuine enough and his explanation simple, but Blake felt suspicious. If Rathbone was as keen on money as he was made out to be, he was hardly a man to part with forty pounds or so until he was asked for it.

"But, you see, this is my concern," said Blake firmly. "I am employed by Mrs. Errington professionally as a detective, and—"

For one fleeting instant Dr. Rathbone's face changed.

"A detective!" he exclaimed. "Then you must be that fellow Sexton Blake people are always talking about. I didn't connect him with the Blake who wrote about sleeping sickness. Well, what is it you want to know? Do you imagine that I am keeping Errington in my pocket or locked in a cupboard? You can come up to my study if you wish, but I hope you will make the interview as brief as possible."

It was clear that the knowledge that the man before him was Sexton Blake had produced a noticeable change in Dr. Rathbone's manner. He led the way into the study, seated himself in a big chair, motioned Blake to take another, and refilled his big pipe.

On the table was a litter of pamphlets and correspondence, and a big notebook or diary, in which were jottings of formulae and temperatures entered up day by day.

Blake asked a few formal questions, which Dr. Rathbone answered curtly and concisely. He was evidently anxious to close the interview, but at the same time to avoid giving Blake offence.

At last Blake rose as though to go.

"By the way," he said casually, "do you chance to have a specimen of Errington's writing handy? Don't trouble if you haven't. I am afraid I have kept you over long as it is."

Dr. Rathbone swept his hand over the littered papers and picked out a page of manuscript, which he held out to Blake.

"There you are; he always writes my pamphlets out for me from dictation."

Blake glanced at it and laid it down again.

"Does he? Well, then, I think you are well rid of him, doctor, for he was a careless secretary. Forgive my alluding to it, but there were two serious errors in your paper on radio-activity which I read some while back. I put them down at the time to the fault of the printer.

"You were made to state emphatically that there was no place for radium as an element in Mendeleev's tables, and the atomic weight was given wrongly."

Dr. Rathbone sprang to his feet excitedly.

"I am sure you are wrong, Mr. Blake!" he exclaimed hotly. "I could never have passed such a thing over; and, to give Errington his due, he was methodical to a degree. Now, to prove that you were mistaken, I—" And he branched off into voluble technicalities, at the end of which, Blake having deftly led him on, he insisted on the latter accompanying him back to the laboratory to have ocular demonstration of some technical detail of his argument.

He switched on the lights to the full, and dragged out a high-powered microscope from its case, bending over it and adjusting the screws.

Blake, too, bent over, but it was not the microscope he fixed his eyes on. They were glued on the nape of Dr. Rathbone's neck, and his face grew suddenly grim and set.

"There," said the latter, "the polarisation is just—" The sentence terminated in a choking cry. He had been resuming an upright position as he spoke, and Blake, inserting a lean forefinger in the back of the well-worn collar of the man's coat, just at the bend of the neck, had, with one quick jerk, flipped off the whole of the turbulent mop of grizzled black hair, leaving in its place a close-cropped sandy head, in gruesome contrast to the long, straggling black beard and whiskers.

The man reeled backwards and clutched at the laboratory bench for support.

"Well, Mr. Errington," said Blake grimly, "an, hour or so ago I promised your wife, who was on the verge of starvation, that I would find you for her. It seems that I have found you."

"My God!" The words came brokenly in a thick whisper, and once again, "My God!" Then a new light came into the man's eyes. He dashed off his spectacles and tore at the straggly false beard.

"What's that you said?" he cried hoarsely. "What did you say about starvation?" And he clutched Blake's arm with frantic strength.

"I said," replied Blake, "that your wife was on the verge of starvation, whilst you were masquerading here in comfort."

"But the money? I sent her money—you said so yourself!"

"Which she refused to touch, believing it to be conscience-money sent by Dr. Rathbone for having harmed you or murdered you."

"But it was mine—my own—money due to me!"

"She did not look at it from that point of view. Now it remains for me to find how you disposed of Rathbone."

The younger man shivered.

"Come back to the room above; I'd better make a clean breast of it. It's not so bad as you think, not by a long way; and when you have heard and seen everything you will perhaps agree with me."

They returned to the library, and Errington, gulped down some almost raw spirit.

"Now," he said, "I will tell you all the truth;, and I can prove it, too. But first, in Heaven's name, tell me how you found me out? I thought I could have defied detection."

Blake looked at him keenly. Bereft of his disguise, though the unsightly blotches on the skin still remained, Errington's face was a pleasant one, and open. He was pale from long hours spent in the laboratory and at his desk; but the eyes were honest, and the mouth and chin good.

"It was as clever a make-up as I have ever seen," said Blake; "and your manner, I admit, deceived even me at first. It was your hands that gave you away principally, and those." He pointed to the grate. Amongst the ashes lay a number of charred cigarette ends. "When I came here I knew little or nothing of Dr. Rathbone, but I did know one fact, that he was a confirmed pipe-smoker. Look at the fingers of your left hand, the first and second fingers are brown and stained—the fingers of the typical cigarette-smoker."

Errington nodded, and Blake continued:

"Now, a confirmed pipe-smoker rarely touches cigarettes at all—certainly not to the extent that you have been doing. That was my first clue. Again, when you came to refill your pipe, you did it in a way which showed clearly that you were a novice, yet the pipes themselves, even those in the rack there, were foul and blackened by long usage.

"Here, again, is something unaccountable—at least, it was. Here is a diary in which certain entries have been made carefully and regularly every day, and the entries are brought up to date. I asked for a specimen of Errington's handwriting. A second's comparison of the sheet you offered me with the diary proved that they were written by the same man. The last entry on this page bears to-day's date; therefore, Errington was alive and well.

"I happened to have glanced through some of Rathbone's pamphlets in print. When I accused his secretary Errington of carelessness, you, who a few moments before had had no words bad enough for him, flared up in his defence. That gave me the last link, and I began to study you more closely still. I got you into a heated argument, and you put aside your pipe and rolled cigarettes one after the other.

"There was only one man sufficiently cognisant with Rathbone's work to argue about it as you did, and that man was his vanished secretary. If that man was daring to impersonate him in his own house, then Rathbone was dead or out of reach, and behind the imposture lay some strong ulterior motive. Your wife mentioned to me some invention of yours in which you believed there was a fortune, and which you wished Rathbone to take up. In that I found the motive which would nerve you to run the risk you did.

"I deduced from those facts that Rathbone had swindled you over your invention in some way; that matters had progressed so far that you were bound to have a Dr. Rathbone on hand lest the whole scheme should fall through for lack of the weight of his name and undoubted reputation as a scientist, and that Rathbone, being dead or murdered, circumstances forced you to attempt to impersonate him.

"Then you suggested a return to the laboratory. That gave me the chance I wanted. As you bent over the microscope I examined the back of your neck, and there, in just one place, I could see the fair hair beneath the wig just on the neck itself. Otherwise, it was an almost perfect disguise. The rest you know."

Errington had been sitting staring at Blake dry-lipped and open-mouthed in utter astonishment.

And I thought I could have stood any amount of cross-questioning and that sort of thing!" he cried at last. "By heavens, I could have, too, if any man but you had had the handling of the job! Even now I can't quite make out how you managed to put two and two together so surely. Every word you've said—even to that bit about my invention—is literal truth, and Rathbone is dead, sure enough. But, Mr. Blake, as I sit here, if these were the last words I was ever going to speak in this world, I had no hand in the killing of him."

Blake nodded.

"I don't think now that you had. At first—well, you can see for yourself that the case looked suspicious, and I have seen so many cases where one man has killed another in a sudden frenzy that perhaps I look at things in a different light to most people. I have known cases of men whose whole lives have been beyond reproach, who have lived cleanly and openly, and yet in a sudden spasm of anger killed their man with bare hands.

"And I have seen many a case of murder where the murderer was a man whom the plain, raw justice of a mining camp would have done honour to as to someone who had rid the earth of something noxious, but here in England he would have hanged.

"So you can easily see that I regarded the possibility of your having killed Rathbone as more likely than not as soon as I discovered that you were walking about in his skin, so to speak.

"But you are not of the type that ‘sees red' in the heat of the moment and does something rash, any more than you are of that class of man who sits down in cold blood to plan the destruction of a fellow-creature's life. You've neither passion enough for the one nor cold-blooded egotism sufficient for the other. I know you're innocent as far as Rathbone's actual death is concerned, or I shouldn't be sitting here talking to you like this. Whether it will be easy to prove you innocent is another matter.

"As a random guess, I wouldn't mind venturing a small wager that Dr. Rathbone was dead when you returned from sending the telegram on the Monday. You needn't start! I know that you sent it, from the simple fact that I went to the local office before coming here; also, I see from your face that my surmise was correct. And I will go a step further. Rathbone died from natural causes—probably an affection of the heart."

"It seems to me that you deal in black magic," said Errington. "You've stated exactly what happened. He was dead when I got back, and I hid the body. Come, I will show you!"

Blake shook his head.

"Let's have your story first. I know where the corpse lies-—somewhere beneath the laboratory floor. From the moment you knew my full name your one anxiety was to get me away from the place into this room. You forgot yourself later in the heat of the argument I forced you into."

Errington nodded.

"You seem to have the whole thing by heart. I will give you my side of the story. Dr. Rathbone—and though he is dead I still say it—was the biggest brute any man ever had to work under. A great scientist and a great worker, but a fiend incarnate. You may have seen an account some time ago in the papers of a method of making rubies and other precious stones from corundum by the action of radium. It was sound as far as it went. The stones were real rubies, and successfully withstood every test; but the method was slow, expensive, and the results uncertain.

"About the time of my marriage I had been working on a similar idea, but with many improvements. A considerable increase in temperatures and high pressure combined magnified the action of the radium, and there were other factors which I need not bother you with. It is sufficient to say that by my process I could turn out stones of any grade of colour with absolute certainty; but I had no money to start working the thing commercially on a practical basis.

"I appealed to Rathbone—showed him my specimens, and offered him a half share if he would supply the capital and use his influence to push the invention. He agreed, and we entered into negotiations with a syndicate with whom he had dealt before. His name, you see, was a guarantee to them. Had the proposal come in mine, they would not have even glanced at it. They bought the invention for fifty thousand pounds and heavy royalties. We got the news on Saturday. On Monday morning Rathbone calmly told me that he didn't intend to part with a farthing when the purchase-money was paid over, and that if I made trouble he would give me a week's salary and send me packing.

"I raved at him, but I could do nothing. I had no proofs that the invention was mine. All the formulae and notes—-everything, even the correspondence—-was in my handwriting, true; but then the same was the case with many inventions which were really his. If I attempted to claim the thing legally, he would have merely said that I, in my capacity as his assistant, had stolen his ideas. No one would have traded with me; the patents stand in his name, for he paid the fees. Not a living soul would have believed my word against his.

"I stormed at him, I pleaded with him—I believe I went down on my knees to him. Finally he flew into one of his terrific rages and ordered me out of the place. He looked as though he was going to have a fit. I seized my hat, feeling sick and dazed, and went to send the telegram you spoke of. When I came back Dr. Rathbone was lying on the floor, dead. He had an aneurysm, and either the excitement or the strain of moving a heavy carboy which stood beside him must have brought things to a climax.

"I rushed upstairs to call the old servant. Just as I got to the door it struck me what his death would mean. He was, so far as I know, without a relation in the world. If his death were known before the date of payment of the purchase-money, my last chance of obtaining a farthing for my invention would vanish into thin air. The money was due to be paid to-morrow.

"For hours—how long I can't say—I sat thinking—thinking. I can't even tell you when the idea of impersonating first came into my head; but come it did, and the more I turned and twisted it about, the more feasible it seemed. Not one of the syndicate had ever seen him; he had not spoken to a soul save myself and the old woman, who is half deaf and blind, ever since I had been with him. I knew every detail of his private affairs, and I have always had a turn for mimicry and acting.

"The old servant gave me no concern; I knew I could hoodwink her. His bankers seemed my only stumbling-block; but I usually made out his cheques and signed them, and he just initialled my signature. Finally I made up my mind to risk it.

"There is a place under the laboratory where we keep acids in bulk. I carried him down there, locked both doors, and started to make-up for my new character. I had an old box of theatrical stuff in the house, and am an adept at using it. The skin eruption I counterfeited with a little acid and some irritant powder, and the rest was easy.

"My great anxiety was for my poor wife. There was a quarter's salary due to me, and Rathbone always kept a biggish sum in the house for paying tradespeople and so forth. I took what was due, and posted the notes the next day. Later I meant to take my share of the purchase-money, destroy the body by means of strong acids, and leave the place as Dr. Rathbone, giving the old woman some money and a holiday, and telling her that I was going, abroad for a month or so. The moment I got abroad I intended to vanish as Rathbone, and reappear as myself under another name, wire to my wife to meet me, and go off to Canada with the money that was rightfully mine. I would not have touched a penny that belonged to him.

"It seemed feasible enough. A few days' anxiety for poor Lucy, and then a life of ease and comfort was all I foresaw. I never dreamt that so insignificant a person as myself would be hunted for.

"When Lucy forced her way in here, I dare not disclose myself, lest she should unwittingly betray me, and I was forced to be gruff and rude, though I loathed myself for doing it. But when I heard your name I got frightened, and tried to face the thing out.

"That is the whole truth, Mr. Blake, and I put myself unreservedly in your hands. You can prove every word I have told you by going through the papers and by—by coming to look at the body. What do you mean to do?"

Blake rose.

"I told you I knew of cases where raw justice and the justice of laws and courts differed," he said. "This is one of them. You were fighting for your bare rights and for your wife's sake. You can count on me as a friend. I shall have to see the authorities, of course. But I fancy my word carries a good deal of weight, and if I tell them your story and prove it to their satisfaction, I think we shall find a way out, and your home in the Colonies will be a reality, after all. Now we must go down and fetch the man who was really missing; then I will send a message to your wife."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.