RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

BLAKE was sitting in his pet armchair in his rooms in Messenger Square, smoking, and glancing through the evening report of a trial which had resulted in a sentence of twenty years' imprisonment. In his own opinion ten would have met the case to a nicety; and he ought to have known, for it was his evidence alone which had brought the man to book.

But the judge had evidently lunched badly, or the Courts had been draughty, and, in spite of the approach of spring, influenza was still prevalent. Anyway the man, ruffian though he was, had got more than his deserts. The case, too, was vilely reported—all the essential details being omitted, and great importance having been given to any sentence uttered by judge, or counsel, which, apropos of nothing in particular, had caused "laughter" in brackets.

Blake threw the paper aside impatiently and turned to a well-worn copy of an old French memoir dealing with the Brinvilliers poisonings, when there came a frantic peal at the front-door bell, and, with a grunt of disgust, he rose and went downstairs.

On the doorstep he found waiting a man whom he judged, in that bad light, to be nearer sixty than fifty.

The man was obviously a countryman—new to London and half dazed—with an honest bluff face, small close-cropped whiskers, and a certain blunt air of distrustfulness and suspicion which appealed to Blake's sense of humour at once.

At the first glance he took him for a farmer up from the country, who had lunched over-well and been robbed of his purse or notebook by a plausible crook in the ordinary way. At the second—the light was very bad—he changed his opinion. He caught a glimpse of the beads of perspiration on the man's healthily-tanned skin, of the dumb horror in his eyes, and of the tense mouth, shut tight like a rat-trap, whilst the blunted fingers trembled with emotion. The hands told of hard physical toil, the tightened lips of a simple man in some mental distress.

"You wish to see me?" said Blake. "Come upstairs and we'll talk the matter over!"

As the man followed him into the room he lurched heavily, and Blake eyed him keenly once more in the better light. He read the case intuitively—no food, no nourishment of any kind, and acute mental strain.

"You be Blake?" said the man, with a strong country accent; and then, in a tired voice: "I be fair mazed, I——"

"I'm Blake," said his host, with a nod. "Sit there and don't speak another word till you've had something to eat and drink. This is your first visit to London, and the din of it has worried you."

The man was clearly dazed to such an extent that he hardly knew what he was doing, and allowed Blake to put food before him and pour him out a good stiff drink.

He ate voraciously, hardly noticing his host, and the food evidently did him good, and brought him to his senses, for when he spoke again it was in a different tone—the tone of a man trained to service, though it shook with some deep emotion.

"Thank ye, sir," he said. "I've had neither bite nor sup since these many hours past. No offence, sir, if I spoke rough at first, but I've been since ten this mornin' trying to find you in this great town, and every minute of it has seemed like a week o' Sundays."

Blake had been sizing his man up whilst he fed, and put him down as the head keeper on an impoverished, rambling estate in a somewhat desolate stretch of coast-bordered country.

The man's accent smacked of Norfolk, his gruff apology and the change in his tone as he became more himself betrayed the outdoor country servant, whilst his general appearance clearly indicated the open life of the woods and covers rather than the smoother one of a gardener.

"No offence whatever," Blake answered heartily; he liked the look of his visitor. "I am only sorry that you should have had so much trouble in looking me up. I fancy you'd find your way easier about the marshes and the broads than the London streets. What is it you wish to see me about so particularly? Don't hurry, tell me your story in your own way!"

The man swallowed twice convulsively, trying to master his emotion.

"It's a black shame," he broke out, at last, "that's what it is, sir—a black shame, and our folk have been in the county this two hundred years and never a breath against one of us."

Blake waited till the outburst was over.

"Go on," he said quietly.

"My daughter Sally was found dead at dawn yesterday down to Marsh Bottom—shot dead, sir, and in her hand was a revolver, and the folk make out it was suicide, and they say worse about her, poor thing! My Sally, that was the best and truest maid that ever stepped. Look ye, sir, I swear before Heaven that she never did a wrong thing in her life—all the nineteen years of it—though she never had a mother to look after her; and, what's more, she never committed suicide. There's been murder done, that's what it is, an' I've come to you, sir, to clear her name and prove it.

"We Chapmans are poor folk, but we've always run straight and honest, and Sally was as good a Chapman as the best of us. Yet suicide the doctor says, and he dared to tell me there was a reason. He lies, and I know it; why for, you say? Look ye, sir, this is for why. To begin with the maid had such a terror of firearms, along of a shock her mother got, that she couldn't abide to go near 'em, much less handle 'em. But I know something of them—I've been keeper this twenty years to Squire Borrodaile. Ours is a roughish part, and I've seen over many poaching affairs not to know what firearms can do at close quarters. I've seen a man's coat singed and burnt half off his back by the powder, and he was shot at a yard away. But my girl's dress isn't so much as marked, and yet they make out she did away with herself."

"You're quite right, Mr. Chapman. If your daughter's dress is not scorched in any way it's clearly impossible, if the wound is in the body, that she could have inflicted it herself with a firearm, for she would have had to hold the muzzle within a foot of herself. There has been some bungling here; if you will give me the details of the story I will do my best to help you."

It took Blake some time to elicit the story with all its minor points, many of which were of the utmost importance, for the poor man was half-incoherent with grief and anger mixed. Put concisely, however, it was as follows:

Chapman was a widower, and, as Blake had guessed, head keeper to a Mr. Borrodaile, on a fair-sized, but rather neglected, estate on the Norfolk coast. There had been considerable poaching for some time past, and Chapman and the under-keeper, Wright, had been kept busy.

The one thing the squire was particular about was to keep his covers well stocked and closely preserved—that and the fishing of a small estuary which split the estate nearly in two. This estuary at certain times of the year was a favourite resort of young seals from the Dutch coast, who committed great havoc amongst the fish—so great that there was a permanent reward offered by the squire of three shillings for every skin over three feet in length. The skins themselves, of course, were valueless.

This fact was important, for, anxious to earn the rewards, and enjoy a bit of sport at the same time, several of the younger men, including Wright, had hired or procured cheap rifles, mostly of .320 calibre. An ordinary shot-gun is practically no use for seal.

At eleven o'clock on the night of the crime, for Blake was sure that it was no mere suicide. Chapman had left his cottage—Sally being at that hour in her room and presumably asleep—to go the rounds of the covers near Marsh Bottom, a spot about half a mile away.

Wright, the underkeeper, was, by arrangement, to work his way down along the far side of the marsh at the same hour and meet his superior at the entrance to a drive through a cover at the far end, known as "My Lady's Bower." This programme was carried out, with the exception that Wright was nearly half an hour late in arriving at the meeting-place and that when he did arrive he was breathless and seemed a trifle excited.

He said something about having fancied that he had heard someone moving in the wood and had lain in wait but without discovering anything. He and Chapman then went the rounds of "My Lady's Bower"—a fair-sized cover—together, and, finding everything all right, made their way back to their beds—Chapman to his cottage, the light of which had been kept burning; Wright to his rooms near the stables.

It was nearly two o'clock when he returned, and Wright was to call for him again at six in the morning. The underkeeper was punctual to the minute, and they started out to see about the young birds' food, according to the ordinary routine.

They reached the edge of a pool in Marsh Bottom, and, skirting it, came all unexpectedly on Sally Chapman's body lying half on her side by the edge of the water, she had been shot just below the left breast, and in her right hand was a revolver with one chamber discharged. She was quite dead, as the horror-stricken father at once realised, and his grief seemed hardly to exceed that of the younger man Wright, who had been deeply in love with her.

Poor Sally Chapman had been the acknowledged beauty of the district for the past two years—well-knit, fairly tall, with a graceful figure, merry, laughing blue eyes, and deep chestnut hair with a natural wave and gloss to it. Every young man for miles round had been running after her. Notable amongst them, however, were two—Wright, the under-keeper, and a man called Baird, a very handsome youngster, with a wild gipsy strain in him, and a confirmed poacher.

It was an open secret that there was bad blood between these two, for Sally had at times shown a preference for Baird; and, on top of that, young Wright had twice been instrumental in having his rival hauled up over a matter of poaching before the justices.

Now Sally's body was found at a trifle after half-past six. She was presumably, almost certainly, in her room at eleven on the previous night, and Chapman and Wright had both been about and within easy earshot of a gun—the night was a still one—till close on two o'clock in the morning.

The doctor, who had been called in as soon as possible, made a hasty examination, and stated positively that death must have occurred between eleven o'clock at night and one in the morning.

During that period it was impossible for a firearm to have been used at, or near, Marsh Bottom without either of the keepers hearing it. It must be remembered that they were on the alert and looking out for poachers, and that both men were trained woodsmen, with a good, sound knowledge of their craft, and on a still night the report of a firearm will carry all of a mile. Not only that, Sally had, so far as was known, never seen a revolver in her life. The police came on the scene early and discovered that the girl had been killed by a .320 bullet, though the bullet itself was nowhere to be found—it having passed right through her body.

Chapman's statement that Wright had been half an hour late for his appointment on the previous night, turned their attention to him and also to Baird.

The rifles of both men were seized, and it was found that both had been quite recently discharged, and not cleaned since.

This fact, however, was explained, as both men, together with others, had been seal-shooting earlier in the day.

The puzzling point was how had she been shot between the hours of eleven and one without either Chapman or Wright—who were both in close proximity to the spot, and both listening intently for any unusual sounds—hearing the report.

The theory of suicide Blake dismissed temporarily on the strength of the keeper's definite statement that there were no marks of singeing. The only alternative that he could imagine was that she had been shot elsewhere, and the body conveyed to where it was found, and the revolver placed in her hand in as natural a manner as possible.

In looking at matters from this point of view, Blake bore in mind that half an hour of Wright's time on that night remained unaccounted for, and that his manner when he turned up at the meeting-place was excited and abnormal. He was a young, active man, and could have covered a lot of ground in that space of time.

The other man. Baird, had proved to the satisfaction of the police that he was in his own house shortly after eleven and had not left it again till seven the next morning.

The one obvious thing to do was to run down and look at the scene of the crime himself. He was very busy, but the case presented some peculiar aspects, and he determined to go into it further.

"I will run down with you to-morrow by the first train," he said to the old man. "We shall have to make an early start, so you had best camp out here for the night on the sofa."

The keeper gripped his hand.

"You be main good to me, sir. But I'm not asking you to do it for nothing." He drew a small canvas bag from his breeches pocket. "There be the half of my savings which I drew from the bank as I came along to London. I'm only a poor man, but you be more than welcome to the money, and if it helps find the man that did it, I wish it were ten times as much."

Blake picked up the bag and put it back again in the man's hand.

"It is very kind of you, Mr. Chapman, to make the offer, but in this case I couldn't think of accepting payment. I am going to act simply and solely in the interests of justice. And now we'd better turn in."

BLAKE, who did not wish to advertise his presence on the scene unduly, dressed himself like any small country farmer, with rough breeches and gaiters and an old shooting-coat, and arrived at the spot in company with Chapman very early on the following morning.

The ground roundabout where the body had been found was soft and had been so trampled by the local police and morbid sightseers as to render any attempt to search for particular tracks worse than hopeless.

The girl had been found with her feet almost touching the edge of the water of Marsh Bottom pool. The pool itself was a desolate little stretch of stagnant water, surrounded on all sides by trees, and fringed with clumps of tall reeds and grasses. Both in going to and returning from "My Lady's Bower" on the fatal night, Chapman must have passed within thirty yards of the spot, and on his return journey his daughter must have been lying there dead. The shot must have killed her instantly, and, in falling, she had turned half-round with the shock of the impact and lay on her left side the right arm swung outwards, and the hand, palm uppermost, loosely holding the revolver.

Blake's first act was to search for the missing bullet. It had passed through the body practically in a horizontal line, piercing the lower portion of the heart, and meeting with no bone to deflect it from its course on issuing from the back.

Sally was a tall girl, close on five-feet-seven; the height of the bullet above the ground, therefore, would be an inch or two over four feet. Its probable direction, however, was a matter of guess-work, and the only thing to be done was to make a systematic search of the trees in the vicinity at the height of roughly four feet.

No one came to disturb them, and for upwards of an hour the two searched patiently, trying first the inner and nearer trees, then those which stood further back.

The revolver was only a cheap German toy, so Chapman described it, and as the bullet had penetrated clean through the body Blake was sure the shot must have been fired at comparatively close-range.

If no bullet was found there he made up his mind to fall back on to his second—and at that stage more probable—theory that she had been killed elsewhere and carried to the spot.

A cry from the keeper however directed his attention to a distinct bullet-mark in a young fir standing back nearly twenty paces from the water.

Blake, who had been searching more to the right, harried over and examined it. The hole was just a trifle under four feet from the ground which sloped up a little at that point.

Blake took his bearings between it and the spot where the body had lain, and gave a low whistle of surprise. Then, taking his knife he dug out the bullet with the utmost care and placed it, still surrounded with a small chunk of wood, into a cardboard box in his pocket.

"You told me it was a still night," he said to the keeper. "Was it a clear one? If so, there should have been a moon."

"That there was, sir. It was dark under the trees and in the covers, but anywhere in the open it was bright as day almost."

Blake nodded. "There would have been plenty of light here by the water on this side, for instance?"

"On this side—yes, sir; t'other would be in shadow, though."

"Quite so. Well now, Mr. Chapman, I think we'll go to your house. I want to see the revolver. I suppose it's still there?"

The keeper's description of the revolver was accurate; it was just one of those gimcrack things to be bought in any small dealer's or a pawn-shop for a few shillings. To have tried to trace the purchaser of it—unless it had been bought locally, which was improbable—would have been mere waste of time.

One chamber had been discharged, and the barrel was blackened. He removed one of the unused cartridges, twisted out the bullet and after weighing it carefully on the palm of his hand slipped it into his pocket. At his request the keeper showed him the gown the poor girl had been wearing. It was neat and plain, but there was no vestige or trace of burnt powder on it.

Just then another man came and tapped at the keeper's door and Chapman's face darkened. It was the doctor—a bright, cheery-faced man of fifty, shrewd and good-humoured, but for the moment looking rather depressed. He spoke a few sympathetic words to the keeper, and glanced inquiringly at Blake.

The latter met his glance and signed to him to step outside for a moment.

"Good morning, doctor. I've come down from London to look into this sad affair," he said in a low voice. "Chapman is positive that it's not a case of suicide, and to be frank, so am I. Had the poor girl shot herself there must have been marks on her dress—marks of burning."

"Bless my soul! you're right, Mr.—er——"

"Blake."

"Blake—the Blake. I'm pleased to meet you. Of course, you're right, and that's one heavy load off our minds. But, to tell the truth, Mr. Blake, I was so upset by the whole affair, and we were all so proud of poor little Sally, that I never thought of that. I was thinking more of my own side of the question, and from the position of the wound alone, it could certainly have been self-inflicted—so"—and he indicated the position with his hand. "Besides"—he dropped his voice to a whisper—"there were reasons, you must understand. The poor girl had not been herself for some time past, but, when I found out the truth, I—well, I could nearly have made an old fool of myself.

"I wish I could lay hands on the blackguard with a good stout hunting-crop, before the hangman got him.

"You see, what with the way the body was found, and—and other things, suicide seemed the most probable."

Blake nodded.

"I promised to look round and see what I could do," continued the doctor; "and I must be able to describe the wound accurately at the inquest. There was little or no haemorrhage. You had better come up, perhaps."

Blake followed him to the small room, with the drawn blinds, where the poor girl lay.

The hands were crossed over the covering sheet.

The doctor pulled up the blind, and Blake stood looking down at the still, white figure. Suddenly he gave vent to a suppressed exclamation, and stooped down.

"Doctor," he said, in a low voice, "come here; look at this." And he pointed to the third finger of the left hand. Round the lower joint of it in a thin band, the skin was very slightly whitened and depressed, as compared with the rest.

"Do you see that? Can you tell me what it was caused by?"

The doctor looked closely. "A ring," he said.

"A wedding-ring; it's the third finger of the left hand."

"Thank heaven!" said the doctor huskily. "Poor little Sally!"

"She had got married secretly, and was afraid to wear the ring openly; so she used to conceal it somewhere, and wear it at night, or when she was sure she was alone. Now I wonder which would be the most likely hiding-place. Somewhere where she could get at it easily."

He glanced round him pensively. "If it had been in any of those cupboards, or she had carried it about with her, you or the police would have found it. What's this hanging up here? Her Sunday dress, I imagine."

He ran his fingers lightly over it here and there, and at last gave a cry of pleasure. In the front of the bodice his fingers touched something hard and round.

Inside the front, where it joined, was a small pocket, cleverly hidden in the lining. He squeezed it sideways and a heavy gold wedding ring fell out into his palm, and he held it there, frowning thoughtfully for a while.

"I'll go down and break the news to Chapman," he said, slowly; "you do what you have to do, and then, if you are at liberty, I should be obliged if you could spare an hour, and come for a stroll with me."

"Delighted if I can help," said Doctor Broughton heartily, and Blake went downstairs to tell the old keeper his daughter's secret.

In a little while the doctor joined him, and the two went outside.

"I suppose," said Blake, "that you, having heard the details and knowing the place, could show me Wright's exact route on the night in question?"

"Without a doubt; this is his path."

They walked for some time in silence till Blake suddenly paused.

"We should be near Marsh Bottom pool by now, surely?" he said.

"Just about abreast of it. But the pool itself lies a hundred yards and more to our left. That little path on the right there, which cuts through the copse on that side, is the one Wright would have followed on his return journey back to the house—the big house, I mean. His rooms were by the stables."

"I think," said Blake, "that, first of all, I should like to have a look at the pool from this side before we go any further."

"As you please," replied the doctor; and they turned off to the left into the wood.

"I suppose people hardly ever come this way?" said Blake.

"Not once in a blue moon. Even the poaching fraternity leave it alone. Its mostly firs, you see, and there's no cover for the birds."

Blake nodded.

"I think, if you wouldn't mind waiting a minute or two, I'll go on from here by myself; we're just coming on to the pool, I see."

Blake was gone barely five minutes, and when he returned his eyes were glittering with suppressed excitement, a sure sign that he had discovered something which he had been hoping and expecting to find.

"The most extraordinary part about the whole affair, to my mind," said the doctor, as he came up, "is that no report was heard. The girl was certainty shot. I am positive, myself, that she was shot between eleven and twelve, and yet neither her father nor Wright heard a sound. Which way shall we go now?"

"I think I should like to follow up that path leading to the house, if Mr. Borrodaile won't mind us intruding."

"Not he! Borrodaile's a first-class man, and a good sportsman; wish I could say as much for the man that will come after him—supercilious young cub."

"And who is that?"

"His nephew, Henry; can't stand the fellow's airs and graces; and, well, it's not telling tales out of school, I don't think Borrodaile can either. They've had frightful rumpuses for these two months past. The estate is in a bad way, and it has always been an understood thing that Henry was to marry the Harbord girl, who is an heiress. Lately, however, he has turned up his supercilious nose at the affair, and the squire let him have it fair and square—told him that unless his engagement was formally announced by next month, he'd cut him off without even the proverbial shilling, and turn the estate over to a distant cousin. Henry knows which side his bread is buttered, though—worse luck!—and he'll cave in when the time comes. There's the house, you can just see it through the trees—a fine old place, but wants a lot doing to it to put it thoroughly in order—and there's Borrodaile himself on the terrace."

A ruddy-faced man, with a bristling, white moustache, was stumping up and down the terrace moodily, sucking at a short briar.

He looked up, hearing them approach, and waved his hand to the doctor.

"Hullo, Jim!" he called.

"Morning, Charlie," answered the doctor. "I've brought a gentleman from London—Mr. Sexton Blake—the famous Blake, you know—who has been kind enough to help old Chapman in this sad affair. He has done wonders already—put the whole thing in a new light, and showed me that I'm an old fool."

Mr. Borrodaile gave Blake a hearty greeting, and the three paced up and down the terrace for a little while talking the matter over.

At last Blake said to his host:

"If you don't mind, Mr. Borrodaile, I should like permission to wander about a little bit and ask your servants a few questions. Don't misunderstand me. I haven't the faintest suspicion of any of them; but there are one or two little points which they might help me to clear up."

"Certainly—anything you please! And when you've finished you'll find us here, and must stay and have a bit of luncheon."

"Thank you," said Blake gravely. "By the way, I find my case is empty. Have you such a thing as a cigarette?"

"No—never touch the beastly things; but you'll find plenty in the smoking-room—that one there—help yourself."

Blake thanked him again, and went off by himself, leaving the other two to continue their promenade.

His task was not a long one apparently, for he was back in less than twenty minutes, and his face was very grim and stern.

The squire and the doctor were still walking to and fro. A third figure, which he took to be Henry Borrodaile, the nephew, was sprawling in a verandah chair, smoking; and old Chapman, the keeper, had just come up to the house to ask for news of Blake.

"Well," said the squire, "did you find what you wanted?"

"I found what I was looking for," said Blake. "And I have found the man who murdered Chapman's daughter. If you would all kindly come into the smoking-room, I will explain."

He led the way, and the others followed; young Borrodaile lurching slightly after the rest, having evidently been indulging in several "liveners."

"To begin with," said Blake, "I was sure from the first—for reasons which I gave the doctor and which he agrees with—that the case was not one of suicide.

"The most mysterious point about it, however, was that, though it was certain the girl was killed between eleven and twelve or a little after, neither Chapman here nor Wright heard the shot, though they were so close that it seemed incredible that they should not have heard.

"My first theory was that the crime had been committed at a distance, but it was mere theory; and my first action was to look for the bullet, Chapman and I together found it embedded in a fir tree. Here it is. I see you have a pair of scales there. We will weigh this bullet, which was the undoubted cause of death, with this other which I extracted from one of the cartridges in the revolver. I have stripped the wood from the crushed one, so the test is fair."

He placed one in either scale, and that on which lay the revolver bullet was at once jerked upwards.

"That, you see, proves that the revolver was a mere blind—a ruse. It was never fired near there at all; but a chamber of it had been discharged elsewhere in readiness.

"Moreover, I was sure that the wound had been inflicted by a high velocity bullet driven by a charge which would have blown that revolver to pieces. To begin with, the wound ran right through the body, in at one side and out at the other. And also, as I learnt afterwards from the doctor, the haemorrhage was insignificant. High velocity bullets cauterise as they pass. These two are the same calibre, but one is heavier than the other, because it was a rifle bullet and longer, similar to the ordinary bullet used by Wright and others for seal.

"Now I come to the second point! We found this embedded in a fir tree at just the height of the poor girl's heart, and taking a line from the bullet mark to above the spot where she had fallen, I found, to my surprise, that the fatal shot had been fired either from the far side of the pool or from a clump of tall grass in the pool itself. The angle precluded any other possibility, for, if fired from any other direction whatever, the bullet could not have hit both girl and tree.

"The doctor has probably told you, Mr. Borrodaile, that we discovered that the girl had been privately married, and also the ring. Here it is. You will see at once that it is of unusual weight and finish, and of London make. A native of these parts in her own class would have given her a much less expensive one. The ring indicated to me that she had married, technically speaking, above her station.

"I next examined the far bank of the pool at a spot in a line with that from which the shot had been fired. The ground was soft, and the story became clear to me at once. The man presumably connected with the story of her secret marriage had been in the habit of meeting her by appointment, when her father was out on his rounds, at the spot where she was found.

"The place was a lonely one, not visited much by either keepers or poachers. On this particular occasion he had come with the deliberate intent of murdering—of shooting the unsuspecting girl down. Instead of meeting her as usual at the agreed spot, he had reached the pool earlier on the far side—his footmarks are on the bank—waded in a little way—the water isn't a foot deep anywhere—and hidden himself in the clump of long grass. He had a rifle, and a cheap revolver, with one chamber already discharged, in his pocket. And his hiding-place was within twenty paces of the spot where the girl would wait. When she came he took deliberate aim and fired. Then, wading across, he bent over the bank, still standing in the edge of the water, and placed the revolver in her hand. By keeping to the water he avoided any betraying footmarks near her."

"But how about the report?" asked the doctor.

"There was none. The shot was fired about a quarter or twenty minutes past eleven; and Wright actually heard the murderer escaping—it was that which made him late in meeting Chapman.

"——The murderer made two mistakes, however. He dropped the empty cartridge-case amongst the tall grass. It lies there now—I could see it from the bank; and he dropped a half-smoked cigarette. I picked it up. Here it is." He paused, and then, placing it on the table before them, added quietly: "You see it is a peculiar brand of Russian."

The squire and the doctor leant forward.

"Great Scott!" said the latter. "Mr. Blake, you can't——"

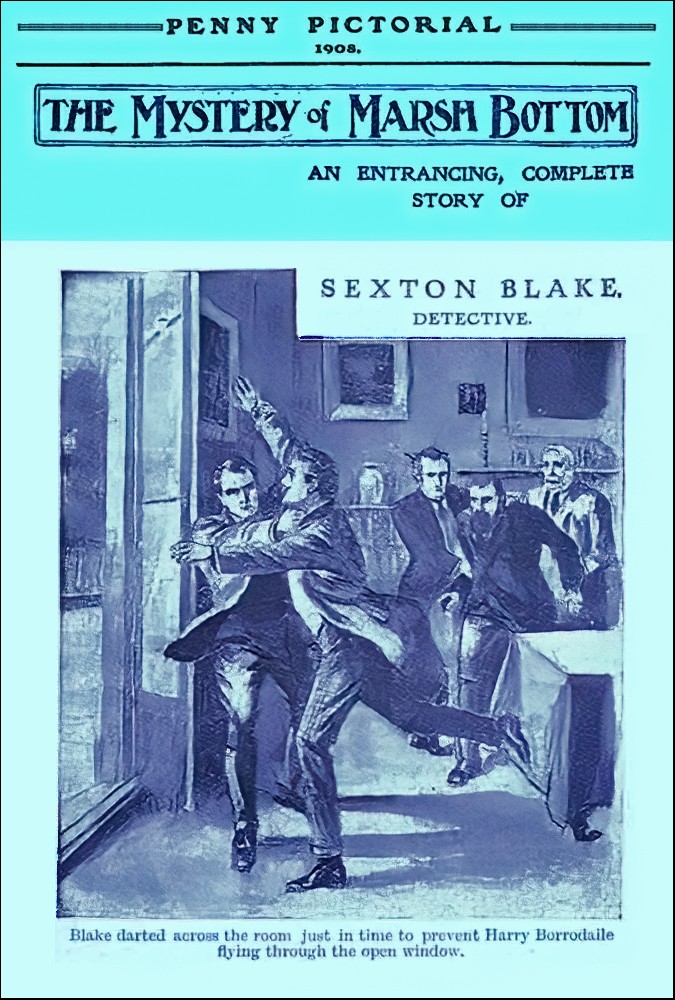

Blake said nothing, but darted across the room just in time to prevent Henry Borrodaile flying through the open window, and gripped him firmly.

With a roar of rage, Chapman, the keeper, would also have flung himself on him; but the squire and the doctor forced him back.

For an instant there was a tense silence.

"He has to all intents confessed," said Blake.

"On that table yonder is a box full of just such cigarettes as this. I took a drawing of the footmarks on the far edge of the pool—his boots fit them exactly. I tried them only a few moments ago. He has, I learn, been in the habit of going out at night ostensibly to shoot duck on the estuary. He was out on the night in question, and came back with his boots and gaiters mired. And last, but not least, in his room in an old case on the top of the wardrobe I found the gun which did the crime and a box containing nineteen cartridges fitting the revolver—it had originally held twenty-five. Here is the key of the room. I will hand it to you, Mr. Borrodaile, as a justice of the peace.

"Now as to the gun! Some months ago a German invented a simple attachment which can be added to any rifle at small expense—the papers were full of it at the time. It consists of a small lever released automatically by the passage of the bullet, and is situated a few inches from the muzzle. Its release blocks the passage of the gases caused by the explosion, and only allows them to escape by degrees—on the principle of the silencer to a motor-car—with the result that the report is practically nil. That man's rifle has such an attachment newly put on. Perhaps you will have it sent for, and I will show you."

Mr. Borrodaile, pale and shaken, rang the bell, and gave directions.

The rifle was brought. As soon as the servant had left the room Blake loaded it and, walking to the window, fired into space.

A faint sighing hiss, slowly dying away and inaudible at a dozen paces, was all that could be heard.

On the stock were the initials "H.B."

Blake pointed to them as he laid the rifle down.

"The motive, I learn from the doctor, is obvious. The case is complete. I leave him in your hands."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.