RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

MR. JOSEPH BERNSTEIN called on Blake at exactly ten-thirty—not the Bernstein of Hatton Garden fame, but Joseph Bernstein, the junior partner of the firm of financial magnates further east, who ruled a section of the diamond ring. The Hatton Garden man was a distant connection and in the early days of I.D.B. (Illicit Diamond Buying) and shot guns charged with rock-salt, they had found him useful.

Joseph Bernstein was a middle-aged, stout, aggressively over-dressed man, with a smartly-trimmed black moustache, a clear complexion, in spite of too many good dinners at the Savoy, and a truculent I-can-buy-the-world sort of air about him.

He reeked of self-assertiveness and ill-gotten gold, and aped an air of boisterous good-humour of the coarse kind, as a rule, which grated on Blake's nerves.

On this occasion, however, there was neither aping nor good-humour. Mr. Bernstein was frankly in a flaring rage; the kind of rage which, in that type of man, causes him to sack an unoffending typist and kick something weaker than himself with genuine pleasure.

"Look here, Blake!" he said as he bounced in.

"Mister Blake," suggested the latter suavely.

"Oh! I beg your pardon," snapped Bernstein, "but we've done Business before, and when I talk business I've no use for frills.

"Now see that?" he slapped a blank cheque on the table. "You can fill that up for any amount in reason you see fit. I'll go as far as five figures, but it's got to buy you—buy you, body and soul, you understand, so long as my job lasts—and it won't take a man like you a lot of time, either."

Blake pushed the cheque aside. "Don't you think you'd better give me an idea of what you want me to undertake first? Some of your dealings in high finance, for instance, are too—shall we say, subtle? for my poor sense of honesty, Mr. Bernstein. Also, I'm rather busy this morning. I can give you just ten minutes."

Mr. Bernstein gulped. He wanted to kick, and it occurred to him that someone else was doing all the kicking.

"It's that young fool Merydell. You've heard of him, of course?"

Blake nodded. "I've seen something about him in the papers."

"Seen something ab——Good heavens, man, the whole press seems to be going mad about the fraud!

"He's got an idea that he can make diamonds— brought it to us, as a matter of fact, nearly a year ago, and asked us to put money in the concern, and we kicked him out, naturally. The world's chock full of fools who pretend they can make diamonds. For the past twenty years a man's cropped up every now and again who melts down a lot of mess and gets a few small useless crystals which may or may not have been diamonds.

"But the only stones worth tuppence have been dug up in our mines, and don't you make any mistake about it. We hold command of the market, and if we say diamonds are so-and-so a carat, why that's the price all the world over.

"Leastways, it used to be like that. But I'll trouble you to take a look at those: you know a stone when you see one as well as I do."

He fumbled in his pocket and produced a small wash-leather bag, in which were two stones, one uncut, the other, cut and polished, and both of a very fair size.

Blake looked at them and fingered them, and examined one by the light of the window.

"Both good stones of rather exceptional colour—almost Brazilian," he said lazily, handing them back. "What then?"

"What then! By George, Mr. Blake, you don't catch on! Merydell made those—made 'em with me standing over him. You can trust my word it was no fake. None of your changing crucibles, re-salting the mess he put in 'em with the real article beforehand. He just made 'em whilst I was standing by him and tossed 'em across to me to keep as 'a souvenir of my visit.' Those were his own words, confound his impertinence! And he chucked 'em at me just the same as I might chuck half-a-dollar to a man for calling me a cab; and what's more, I know for a fact that the man was half starving at the time—not worth a sovereign as he stood—yet he flings at me two stones worth every bit of sixty pounds."

Blake laughed gently to himself. "As a matter of fact, Mr. Bernstein, we both of us know that these two diamonds are worth more than double that, and so, as you have got a present of close on a hundred and fifty pounds, I really can't see why you need come and bother me about it."

"Not bother you about it! Mr. Blake, a joke's a joke, but this is past anything of that kind. Can't you see that if this Merydell can make stones like that, our mines are ruined, done for, squashed, and that all the millions of capital we've sunk in 'em aren't worth a fraudulent greenback, and the thousands of poor workers for whom we provide a livelihood and a means of existence will be thrown out of employment?

"Do you realise that he told me he can turn out stones like that now at an average cost of ten pounds apiece, and that if he gets going on a big scale that ten pounds will be reduced to a fraction. Man alive, it's sheer ruination!"

Blake yawned in undisguised boredom. "In that case Merydell has made a fortune, and you've got to face the prospect of losing one. I fail to see where I am concerned in the matter."

"But I do," almost screamed Bernstein. "I don't offer a cheque of five figures for nothing. I know diamonds and I know my business, but this Merydell show is beyond me. I am paying you to find out how the man makes his diamonds, or, at least, to find out enough to give me a guarantee that the thing is genuine."

"And then?"

"Then I shall know for certain where we stand."

"But you say you've seen the actual process and know that it's genuine. Why not buy the man out or take him into partnership?"

"Buy him? I made a suggestion to him, and he just laughed at me. Told me I'd had the chance once, and that I'd turned him out of the office. I'm not denying that I did, mind you; but when I offered him a price he just laughed, chucked me those stones, and hinted that his time was valuable and that I might take myself off."

"So is mine," said Blake lazily, looking at his watch. "You remind me that I've an appointment in five minutes."

Mr. Bernstein rapped fiercely on the cheque with his knuckles. "But this is vital—can't you understand? The interests involved are enormous, and here's this bit of paper in consideration of which I am buying your services."

Blake shrugged his shoulders and rose. "You can take your cheque or leave it," he drawled. "I may glance into the matter, if I've time. Good morning!"

Mr. Bernstein looked for a moment as if he would have liked to stretch Blake dead on his own office-floor, but he needed him desperately, and so managed to control himself. He put on his extremely glossy hat with a thump, made a vicious snatch for his umbrella, and went out slamming the door. Mr. Bernstein was accustomed to a world where his money could buy anything and everything. He was, in fact, rather like a peculiarly unpleasant, spoiled child.

Blake sat back in his chair and chuckled. Mr. Bernstein's obvious annoyance amused him, and he also happened to know Merydell slightly, and had taken rather a liking to him.

He found his address without any difficulty, and wired to him to come and dine with him that evening at a small restaurant in Soho.

Merydell turned up punctually. He was a tall, lank man with broad shoulders, and lean hips, and the muscles and sinews of him were like whipcord; clean-shaven, but otherwise distinctly careless about his appearance.

Blake surveyed him with a critical glance, and came to the conclusion that Bernstein had not exaggerated when he spoke of the man as half-starving. His quick eye noted unnecessary hollows beneath the cheek-bones, and shadows under the deep-set eyes.

"Good evening, Mr. Merydell," he said pleasantly. "I am glad you managed to come. I've got a little business to talk over with you. However, we'll dine first and discuss things afterwards."

Merydell, a man of few words, nodded, and set about his dinner in a businesslike fashion.

"Good heavens!" he said, with a sigh of satisfaction, stretching his long legs as the meal drew to a close. "You don't know what pleasure there is in eating really decent food again. For the last two months I've been doing my own cooking over a Bunsen burner, and I should say I was the vilest cook ever born. Don't know why I didn't half kill myself."

"Why on earth did you do it, then?" said Blake. "A man who can make diamonds worth seventy or eighty pounds apiece can surely allow himself a few luxuries."

"Ah," said Merydell slowly, "I imagined it was that you wanted to sew me about! Yes, I can make diamonds right enough; but I don't mind telling you, now that I have turned the corner, that I jolly nearly starved for weeks at a stretch before I found out the trick of the making. Funds ran clean out, and I lived on an old coat and waistcoat one week, and fared sumptuously on the proceeds of a cheap German watch another, and so on. My materials ran into money too. Yet even when I proved that I could make diamonds—the genuine article—beyond all shadow of doubt, I couldn't get those fat fools in the City to put up so much as a penny piece on the evidence of their own senses.

"I was astounded—flabbergasted. I'd used up all my material in making the stones under their noses, and hadn't a cent to buy any move, let alone any food to put under my belt.

"I tell you, Mr. Blake, for about forty-eight hours I was like a sick dog, with never a kick in me. Then I took up my belt a couple of holes, and went round to the metallurgists begging, borrowing, and praying for boron from one man, something else from another, and so on, till I could start again.

"It wasn't nice. I don't like eating dirt more than the next man, but I did it. Made some stones, sold 'em, and paid for more material, and now I'm on my feet and can do as I please." He threw back his head with a sharp, hard laugh. "And one of the things that will please me best is to make the fat City fools pay for their folly, and cringe and grovel.

"Oh, I can tell you I've a long score up against them! I'm not naturally a revengeful sort of animal, but this trip I'm out for blood and plenty of it, and somebody is going to squeal."

Blake drummed on the table pensively with his fingers.

"They used you badly," he said, half to himself.

Merydell laughed again.

"Badly, ye gods and little fishes! There are one or two of them that, the moment I get a few more dozen stones on the market, I am going to interview with a good stout hunting crop and pay my fiver apiece for like a man. Five! There's one I'll cheerfully pay five hundred to thrash, and when he summonses me before a police-court, or whatever the etiquette of those matters may be, I shall let slip a few facts that will pretty well stagger this snug, law-abiding village of ours."

"Look here, Merydell," said Blake suddenly, "I'm going to be perfectly frank with you. I was offered a commission this morning to have a look into your affairs and this matter of the diamonds. I refused either to decline or accept it. I have reasons of my own for disliking the man who made the offer, and I wanted to have a chat with you first. From what you have said, and I expected the story would run pretty much that way, I have decided, and I shall absolutely decline to touch the matter,,so we'll let that part slide.

"On the other hand, as you know, I'm interested in scientific questions. I am convinced that the making of diamonds is, after all, a comparatively simple thing when once someone has discovered the secret. The question is, are you sure that you have got hold of the right scheme? Isn't it possible that your successes may have been accidental?"

Merydell glanced round him. That part of the restaurant was practically empty. He drew from his inside pocket a leather bag, untied the string, and poured the contents on the tablecloth behind the edge of his plate.

"Mr. Blake," he said slowly, "I've been many kinds of a fool but I've never been a liar. I give you my word of honour that I made these—er— accidents, and that in the making of them I had only two failures owing to an insufficient supply of heat. Kindly examine them!"

There were close on a hundred stones; eighty or so were of fair size and practically of uniform weight. The remainder were nearly twice as big—all were uncut.

Blake picked out some at random here and there, and examined them carefully.

"I take back the word accident," he said quietly, "you've found the secret, sure enough. Those are all high-class stones, and if they'll stand the cutting and polishing as well as the natural article I should value that lot at roughly eight thousand pounds."

Merydell nodded.

"Eight thousand three hundred at present prices, and they cost me no more than the odd hundreds for the making. When I get going on a big scale the cost will be reduced to a quarter of that, and there won't be nearly as much waste. As for cutting, look at this."

From his waistcoat he produced a single large stone, superbly cut and polished.

"Isn't she a beauty?" he asked enthusiastically. It's worth going through what I've been through for that. With a few thousands of them I can light the whole combine and smash it—knock the bottom out of it."

Blake nodded.

"That to me is the strongest proof of your success. Bernstein for one is getting frightened."

"Bernstein!" Merydell stared. "Do you mean to say that he actually had the nerve to come to you? Why, the man ought to be hung out of hand as a murderer. Look here, I've only given you an inkling of what's been going on. It was Bernstein and his gang at first who tried to squeeze me out and starve me. They got the metallurgists to cut off my supplies. They tried to bring an action against me for fraud. But when they found all those methods a failure they tried more stringent measures."

He opened his coat and showed the dully-gleaming butt of a revolver.

"I've had to carry that about for weeks, and sleep with it under my pillow."

Blake nodded.

"I noticed it when you came in."

"They found out where I used to get my provisions; a week later the shop changed hands— a creature of Bernstein's had been put in. I indulged in sugar in my tea in those days. I used two lumps out of the new packet, and was on my back for nearly a week, sick as a cat—poisoned. The only other lump I used out of that packet was for analytical purposes.

"See this here"—he pointed to a livid white scar on his temple and a red blur where his eyebrow should have been—"Bernstein again. When I was out one day they broke into my place. Couldn't find anything because I carry all my information in my head and my diamonds in my pocket, but they faked some of my mixing clay with high explosives, and when I put the next crucible into the furnace I left the room in mid-air through a window. Blew me clean out of the place. Why I wasn't killed I'm hanged if I know. If I'd struck a wall instead of a window or butted into a bit of crucible, I suppose Bernstein would have felt happy and sent a wreath and a card."

He paused and gave a deep chuckle.

"Look here, Mr. Blake," he said, "you've chucked up Bernstein's case, you say? Well, as you've washed your hands of friend Bernstein, why not accept me as a client, and see if between us we can't catch the gentleman tripping. I've told you that these various surprises are his handiwork, and they are; but I've no proof, and I've been too busy to look into things. You could, though, and we might be able to lay him by the heels."

Merydell's eyes twinkled at the idea, and Blake gave a grim smile.

"I think, on the whole, that I will," he said slowly. "In the first place, I owe Bernstein a grudge. He's a most unpleasant brute, and needs kicking; and in the second, I think that without myself or someone else to help you, the chances are about ten to one against your being alive a week after those diamonds are on the market. In fact, 1 strongly advise you not to dispose of them until we have seen our friend. Now pay me my fee and I'm with you. My fee is that you let me see you make a diamond with my own eyes."

Merydell sprang up.

"Good, man! Come along down to my place and I'll show you the whole bag of tricks, for I know that with you a secret is a secret. I'll give you the formula, and you shall make one yourself."

"Capital!" said Blake. "By the way, are you sure Bernstein knows that you intend to make a deal to-morrow?"

"Dead sure. He'll have known it at four o'clock this afternoon. I took pains that he should. I thought it was calculated to annoy, you see."

"I see one thing," said Blake quietly. "You and I will travel in separate cabs, and you will go first. Tell your man as you get in that if he hears one loud whistle he is to stop dead. From what I know of Bernstein he'll have lost his temper and his caution, and will try to act before you can spread your story round the market. That means he will try to-night."

"Let's get a couple of hansoms then," said Merydell, and left the restaurant.

Blake waited a few seconds and then followed him out.

MERYDELL'S cab was just out of sight round the corner as Blake got into his and bade the man follow, and with a space of fifty yards between them the two drove swiftly westwards towards Notting Hill.

They were just passing the end of Marshfield Street when Blake leant suddenly over the dashboard. His quick eyes had distinctly seen the driver of the first cab give a peculiar signal with his whip. An instant later a man who had been standing at the corner of the street strolled away, and as Blake's own cab flashed past he saw that the man had broken into a run as soon as he was clear of the lights of the main thoroughfare. That meant that Merydell had been followed to the restaurant, for Bernstein's house lay up in Clarestone Square, which is barely three hundred yards from Marshfield Street.

Bernstein had told his men to have a cab waiting to watch Merydell's movements when he came out.

Merydell had seen a cab and hailed it. The man had jumped at his chance and driven him off, not realising that he was being followed, for the order about the whistle he would take, if he knew anything of what was afoot, as Merydell's own idea.

Twice further down the road, and at long intervals the cabman signalled again, and the road led straight to Merydell's destination. For once in a way Bernstein had been lavish with his money.

At Notting Hill a narrow, slummy, decayed-looking street leads upwards at a gentle slope, and there terminates abruptly in a larger tract of waste land cut in two by a railway line.

It is as dreary and squalid a place as any to be found so near a central part of London. At one time, probably as long ago as when the railway was in building, worksheds had been set up here and there on the waste ground. Rough, unstable creations. It was one of the largest of these which Merydell had turned into a dwelling, laboratory, and workshop in one.

Blake saw the cab in front of him slow down as it approached the end of the street, and promptly stopped his own man and got out.

"Here's half a sovereign for you if you make yourself scarce before the other man sees you," he said.

"Righto, guv'nor, I'm off!" answered the cabby, and was gone like a flash.

Blake sprang into the shadow of a doorway and waited for Merydell's cabman to pass him on his return. When he did, the street lamp shone full on his face for an instant, and Blake gave a low whistle of surprise.

"Samuels, by Jove!" he muttered. "This begins to look ugly!" Samuels was known to him of old as a man with two known but unproven murders to his credit. "I think Merydell will be glad I came before the night's out."

He hurried on and caught up the latter, and side by side they hurried down a muddy, broken, cart track.

It was a good quarter of a mile from the nearest dwelling to Merydell's shed.

The shed was merely a timber affair with one brick wall. Merydell ushered him in and lit a lamp.

. "Now then," sail he, "I'll show you a diamond in the making."

Blake glanced at his watch.

"You've a short half-hour to do it in," he said grimly.

Merydell turned round with a start.

"What the deuce do you mean?"

"Exactly what I say. The man who drove you is one of Bernstein's. The latter has had a report by now that you returned home—alone. It will take the cabman twenty minutes to reach Bernstein's house—not more. Bernstein will have his car waiting, and will be back in another ten with some of his ruffians. Then the fun will begin. You chose a nice isolated spot when you chose this shed, but if you paid me I couldn't tell yon of a more unsafe one for a man in your position. Have you got such a thing as an auger? If so, lend it me."

Merydell looked at him quizzically.

"They're taking no end of trouble, aren't they?" he said pathetically. "Here's a brace and bit; will that do?"

"Capitally," said Blake, and kneeling he drilled a hole in the plank wall some few feet from the door, and plugged it with paper. "Now then," he said, rising, "show me what you can do in half an hour."

Merydell shook his head.

"I want twice as much as that, even with everything prepared; but I'll have a shot. This stuff here is common blue clay, the sort stones are generally found in. Here are salts of boron—animal charcoal—all in powder, and on that bench are clean crucibles. Take a crucible and put in the stuff in proportions of five, one, and one. Now take this phial." He held up a small glass bottle containing an ounce or so of colourless liquid. "Add just ten drops of that and close the crucible with one of those clamp lids."

Blake did as he was told.

"Now," said Merydell, "you're satisfied that I've not played any monkey-tricks?"

"Quite," said Blake. "You're using a moderation of Charpentier's old formula which proved a failure. What next?"

"Put the crucible in the oven and switch on the current."

Again Blake did as he was told, and clanged-to the door.

Suddenly Blake caught Merydell's arm.

"Hush!" he said warningly. "I heard a step outside! Don't speak again till you're spoken to."

"I heard nothing," whispered Merydell. "You must have the senses of a wild animal."

"I need to," said Blake drily. "Keep your eye on me, and do just what I motion you to do."

As be spoke he knelt down on one knee at the hole he had bored and put his eye to it.

For the first ten seconds he could distinguish nothing in the darkness outside; but as his sight got more accustomed to it, he managed to make out the figure of a man crouching down, with-something in one hand—what, he couldn't quite make out.

Then away to the left he saw a second figure—and a third. The last was Samuels.

There was a faint glimmer of light through a crack in the door. The second man stepped across its track, and it glinted on his face.

For the second time Blake gave vent to a low whistle, and drew his revolver from his pocket.

The fellow was a man known as "Tim the Butcher"—a notorious hooligan.

Blake smiled grimly to himself. Had either of those men known that he was inside the building wild horses wouldn't have dragged them within a mile of it. He slid his hand over the hole to prevent the light shining through, and beckoned to Merydell.

The latter cams and stood behind him.

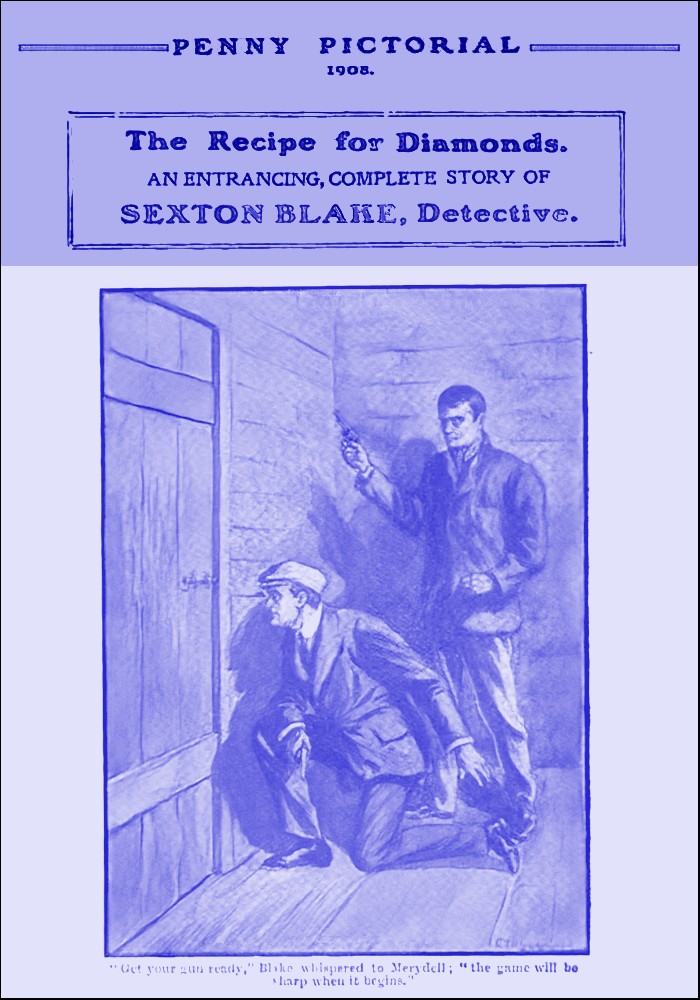

"Get your gun ready," Blake whispered. "I don't know what their game is yet, but it'll be something sharp when it begins. Fire at once when I give the word, and don't miss your man."

Presently they heard footsteps, quick and unguarded—a stumble—and a very palpable oath.

Blake returned to his peephole and laughed softly. Outside in the pouring rain, wrapped to the neck in a motoring mackintosh, with a high collar, stood Mr. Bernstein himself.

He evidently intended to see that there was no bungling on the part of his hirelings. Matters were too critical; and he had nerved himself to the pitch. Physical courage was not Bernstein's strong point, and he swayed slightly as he stood, showing the source from which the courage had been derived. His brain was clear enough, however, and all the dogged, tenacious obstinacy of his race was up in arms. His fortune was at stake, and he would have gone through living flame to save it if he could.

"Mr. Merydell," he bawled above the swish of the rain—"Mr. Merydell, I want to speak to you! I've come to make terms."

His voice was husky, but his determination— and libations—kept the quaver out of it.

Getting no answer, he came up to the door and rapped on it hastily, and leapt back.

Then at last Blake saw the game. On either side of the door, a yard or so away, crouched a man with the end of a slack wire in one hand and a heavy club in the other. The third, Blake guessed, though he couldn't see him, was lying in wait by the door itself. Beyond stood Mr. Bernstein.

They hoped to lure Merydell outside. Then the wire would tighten, with a jerk, and trip him, and the clubs would effectually do the rest.

Blake nodded to Merydell; and the latter took his cue.

"Don't move a foot from the room," whispered Blake.

Merydell put his hand on the latch and called out sharply:

"Who's there?"

"I—Bernstein! I've heard what you mean to do to-morrow; and I've come to offer terms."

"Oh, you've come to your senses, have you?" said Merydell. "I don't think your terms will suit me."

"At least, let us talk things over," said Bernstein. And they heard him curse beneath his breath. "Let me in! It's so infernally dark out here—I can't see an inch; and it's raining like the deuce."

"As yon please," said Merydell.

Blake rose softly to his feet.

"You take Bernstein," he whispered. "I'll attend to the others." And he picked up a heavy piece of iron piping in his left hand.

"Open the door, step aside, and take Bernstein as he comes in. Now."

Merydell opened the door and leapt back. As Blake passed him in a flash there came a dull thud and a groan. Blake's iron bar had caught the third man just as he raised his arm to hit, and broke it at the elbow.

"Drop that line, Samuels—quick, or I fire!" he called sharply. "You, too, Tim! I've got you covered."

Samuels, catching a glimpse of Blake's face, gave a hoarse cry and, dropping the wire, flung up his hands.

Tim the Butcher raised an arm to fling his club; and the revolver spat venomously in the dark. The man gave a shriek, and dropped with a bullet through his foot, and lay writhing.

Mr. Bernstein turned and fled; but Merydell, disobeying orders, was after him, with a shout.

Mr. Bernstein was fat and out of condition; and Merydell's long legs finished the race in half a dozen strides. His heavy hand descended on the collar of the mackintosh, and the financier was yanked off his feet.

Take him inside," said Blake sternly. "You, too, Samuels—in with you, and bring that man Tim along! If you attempt any tricks, you'll get a bullet in you, too; but I fancy you know me too well to try it on."

The man, thoroughly cowed, obeyed.

Blake himself picked up the third, who had fainted, and carried him in, laying him on the floor. Then he shut the door and bolted it.

"Now, Samuels," he said sharply," how much did that man"—pointing to Bernstein—"offer you for the job?"

"Fifty pound apiece, Mr. Blake," came the mumbled answer. "Another hundred to split up if we 'outed' 'im, an' a free trip to the other side."

"When was the offer made?"

"Only to-day, guv'nor. But if we'd known as you wos——"

"That will do!" The words came like the crack of a whip.

He looked at Samuels, at Tim—who was moaning with pain—and at the man on the floor.

"I don't know your friend here," he said grimly, "but I sha'n't forget him."

He slipped his hand into his breast pocket, and drew out a blank cheque, which he tore across, and turned to Bernstein.

"I've known you for a swindler, a thief, and a fraud," he said slowly. "Now I find you've been dabbling in murder. Yet you had the insolence to come to me this morning and ask me to help you defraud a man of a fortune which he honestly earned. I refused to give you an answer then; I give it now!" And he flung the torn cheque in the man's face. "Now do exactly as I tell you. There's pen and paper. Sit down and write a confession of your various attempts on Mr. Merydell in full. If you don't, you and these men here will be in a police cell inside the hour.

"Now. Merydell, what are your ideas of terms? Do you want money, fame, or what? If you go on knocking the bottom out of the market by turning diamonds out by the thousand, you may ruin Bernstein & Co—will, in fact—but you'll be lowering the value of your own wares as well. What do you want most?"

Merydell stretched his arms, and laughed.

"Money," he said laconically—"money and ease and a yacht to go about and see things in! Good heavens, you don't think I'm enjoying myself poring over furnaces? I only did it because I wanted money—not a great deal—say a couple of hundred thousand. My idea was to turn the thing over to a company for that, and clear out. It's worth millions properly handled; but I've no head or liking for business."

"You'll be satisfied with that?"

"You bet. But that little beggar would never keep a bargain."

"Oh, yes he will!" said Blake. "Now, Bernstein, listen to me! Have you finished writing? Humph! Yes, that'll do. Sign it."

The man signed meekly, all the fight gone out of him. And Blake pocketed the paper.

"These are the terms. The diamond ring which you control will pay to Mr. Merydell to-morrow at noon one hundred thousand pounds. On this day month you will pay another hundred thousand."

Bernstein gasped.

"Or you will be convicted of attempted murder," said Blake sharply. "Your ring is worth several millions; yet Merydell here could have ruined the lot of you. In addition to the two hundred thousand, you will pay him an annual income of twenty thousand, in lieu of royalties on his patent, and on these conditions—Mr. Merydell will undertake to make no more diamonds, except for experimental or personal purposes. He will pledge his word to put none on the market in any way. Also, in case Mr. Merydell should die young—as you would naturally wish under the circumstances—his formula will be placed in a sealed envelope in a safe place. On the day following his death under suspicious circumstances, that formula, with full details, will be published broadcast throughout Europe; and in a week the shares of your mines would not be worth the paper they were printed on. You understand? At noon to-morrow Mr. Merydell and I will call at your office. If you don't carry out your side of the bargain to the letter you know what will happen. Now go, and take those friends of yours with you as best you can!"

Mr. Bernstein gulped, swayed to and fro on his feet, and staggered blindly into the darkness, without a word.

Samuels slunk away, supporting the other two. Merydell danced a jig on the floor.

"Man, dear, we'll go on a cruise in the Greek islands, and dream the days away in sunshine." And he heaved a heavy lump of iron at the furnace, smashing the door.

Blake laughed.

"How about my experiment?"

Merydell seized a pair of tongs, and drew out the crucible. There was a hissing crackle, a cloud of steam, arid a loud report as he plunged it into a tank of water.

He groped about amongst the fragments, and, with a cry of triumph, fished out a large soapy-feeling stone.

"'Tis the last I'll cook!" he said, holding it out.

Blake took it in his hand.

"I'll keep this as my fee," he said, chuckling. "You'd better come back to my rooms for the night."

"I'll stay with you a week, man, dear!" said Mr. Merydell. "But I'm hanged if I'd like to be in Bernstein's shoes this minute. And he a bloated millionaire, too! Mr. Blake, I'm wanting a long, large, fizzy drink. Let's be off!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.