RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

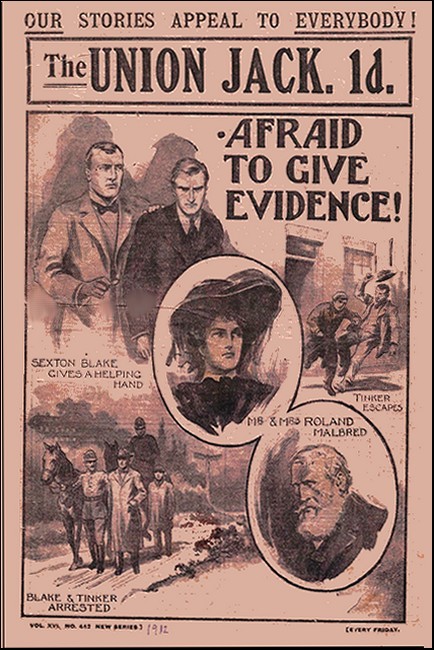

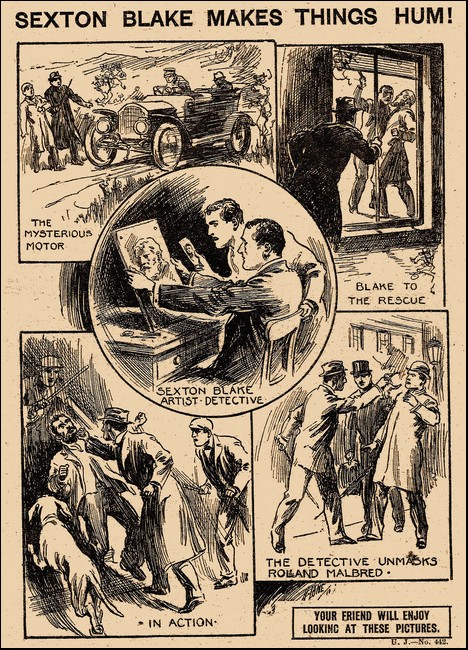

The Veiled Lady.

SEXTON BLAKE mounted the steps and entered the police-court. It was a gloomy day in the streets, and the lights in the court shone murkily through the haze that had crept in. A rank odour permeated the place, and sad faces, criminal faces, and pinched and hungry faces were everywhere except upon the bench and around the table where the lawyers were grouped.

It was a dismal scene, where tragedy plays its part every day, where sorrow, destitution, and crime are laid bare; a stage on which are unfolded the anguish and passions of the human underworld.

Moving unobtrusively through the crowd gathered near the door; Blake took a seat at the back of the court. A burly man was standing in the dock and a woman with a child in her arms near Blake was sobbing. The man was her husband.

Other women of her order in other parts of the court were pale and trembling; all had come here on this bleak day to hear the doom pronounced on those who were dear to them despite crimes the law could not condone; many more in like case would be here to-morrow. From year end to year end a police-court is a tragic scene.

The man in the dock was sentenced and led away to the cells. He was followed into the dock by another and another, the magistrate dealing with each case briefly, but with the shrewd experience of a lifetime that usually enabled him in a few quick questions to separate truth from falsehood. For half an hour these cases went on, and then for the first time one of an unusual nature presented itself. A solicitor stood up and addressed the magistrate. The former charges had not been defended by any lawyer.

"I appear for the prisoner in this case, your worship," a young, keen-faced solicitor explained.

At once there was a slight stir. The magistrate knew that a fight for the prisoner's liberty was going to be put up; the police knew that they would have to defend his arrest, and submit themselves to a clever cross-examination; all in the court were glad that some excitement was promised to give an interest to the sordid drama they had been obliged to listen to so far; the reporters, anticipating that this case might be of interest to the newspaper readers, opened their notebooks, and sharpened their pencils.

A young fellow, eighteen years of age, was now standing in the dock. He was very poorly clad, and his face was sullenly defiant.

"What is your client's name, Mr. Bricage?" the magistrate asked.

"Hugh Rollings."

"What is the charge against him?" the magistrate inquired of a police-sergeant.

"He is charged with others, not in custody, of threatening and assaulting people, your worship," the sergeant replied. "He belongs to a gang who—"

"You have no right to say that at this stage of the case!" the solicitor interrupted sharply. "Conduct the prosecution in a proper manner."

"Go into the witness-box and give your evidence," the magistrate directed.

The sergeant, his face a deeper purple after his first encounter with the solicitor, mounted into the witness-box, and was duly sworn.

Blake, having heard the prisoner's name, shot a swift look around the court. He was looking for Tinker. Tinker on his return home late the previous night had told him that he and some of his friends had been attacked by this young fellow and several others. Tinker and his party had put up a good fight, and had escaped with a few knocks. The police had arrested Rollings, and had made Tinker come to the police-station; his companions had slipped away when the fight was over. The police were calling Tinker as a witness, and it was on this account that Blake had come to the court.

He saw Tinker seated close behind the lawyers, and next him was a woman heavily veiled. The prisoner was scowling at Tinker, and the woman's head was bent.

The sergeant gave his evidence. He had seen a crowd in a street in Whitechapel; he knew that fighting was going on, so he blew his whistle and hurried to the spot. As he approached he saw a well-dressed young gentleman, who was now in court, defending himself against two men; another gentleman was on the ground; a third was fighting his way out. There was a crowd of about two hundred people, and all were hostile to the gentlemen. A lady, also in court, would be an important witness; she had been on the spot when the attack began, and had also been assaulted and robbed.

The solicitor asked the sergeant a few questions, but did not cross-examine him severely. Apparently he thought that the sergeant's evidence was not convincing as far as his client's guilt was concerned, Then Tinker was called.

He stepped into the box, bowed to the magistrate, who gravely eyed him over his spectacles, and was sworn. The sergeant proceeded to question him.

"You were in Balting Row, Whitechapel, last night at about ten o'clock?" the sergeant began. "And you were there with some friends?"

"Yes," Tinker replied.

"You were walking quietly along the pavement when some men rushed out of an alley and attacked you?"

"Yes."

"Was the prisoner one of those men?"

"Yes."

"Tell the Court what happened."

"It was this way, your worship," Tinker began, leaning on one elbow and affably addressing the magistrate. "We were walking along, chatting, just the same as you might be—"

"Stand up straight, and don't speak that way!" the magistrate snapped, "The way I talk has nothing to do with this case!"

"No; of course not!" Tinker assented.

"Don't bandy words with me, sir!" the magistrate thundered.

"I don't want to bandy words with anyone!" Tinker replied. He was beginning to feel angry.

"Don't be impudent!" the magistrate retorted. "Go on! Give your evidence properly—that is, if you know how!"

A short silence ensued, Tinker standing very straight and fingering his collar. He had not anticipated this experience, and it was not at all to his liking. The sergeant addressed him.

"You were chatting with your friends when you were attacked?" he suggested. "How did the attack begin?"

"I can't tell that," Tinker explained, "for the first thing I knew was that I got a whack on the back of the head that knocked me against a wall, and raised a lump the size of a walnut. I heard shouting, and I steadied myself, and turned round. Then I began to use my dukes."

"To use your dukes!" the magistrate said, in puzzled wonder.

"He thinks he is a duke, perhaps," the defending solicitor chuckled, just to annoy the lad the more, so that he might get flustered and possibly contradict himself.

And a titter ran round the court.

"I began to use my fists, and there ain't much of a duke about me!" Tinker replied. "And I could crack a better joke than that standing on my head! I started defending myself, anyhow, and two chaps came at me. I plugged one in the eye, and caught the other on the chin. We went at it then hammer and tongs, and I was kept busy until a cry went up that the police were coming, and the scoundrels bolted."

"And this young man, Hugh Rollings, now standing in the dock was one of those who attacked you?" the sergeant asked.

"He was."

"Those are all the questions I wish to ask this witness, your worship," the sergeant said.

The solicitor arose slowly. He did not speak for some moments, but he gazed at Tinker as if the lad was some curious sort of creature he had never seen before, and he rubbed his chin reflectively. Tinker knew this man meant mischief. He looked at him steadily.

"So you were in Whitechapel last night at ten o'clock, and you used your dukes?" the solicitor began, smiling in a very irritating way. "You rather enjoyed the experience—eh?"

"I didn't mind it!" Tinker replied offhand.

"Of course not! A great big fellow like you doesn't care a pin about tackling a couple of men—eh? You would have polished off half a dozen easily, wouldn't you?"

"That would depend upon their pluck. I would take on a couple like you, anyhow!" Tinker retorted.

A roar of laughter went round the court. Tinker began to feel happy again. The solicitor still had that cynical smile on his face.

"Of course—of course!" he said. "And now may I ask, do you live in Whitechapel?"

"No; I do not."

"Then why did you go there at ten o'clock last night?"

"Just to have a look round."

"Oh! Where do you live?"

"In Baker Street."

"And you went from the West End all the way to Whitechapel just to have a look round. I suggest that you went to Whitechapel in order to cause a disturbance, and that you are to blame for what happened."

"You can suggest what you like!" Tinker replied loftily. "That's not the case, though!"

"We'll see if it is or not, my pugilistic young friend," the solicitor replied coolly. "Who were with you?"

"Friends of mine!"

"Ha! You don't want to tell the court anything about them, but I'll drag the truth out of you!" the solicitor thundered, his whole manner changing as he shook a threatening forefinger at the lad. "Give the names of these friends!"

"One of them is Dick Plane."

"And who is this Mr. Dick Plane who finds such enjoyment in your charming and elegant company?" the solicitor sneered.

"He's a medical student."

"A medical student! And he can use his dukes, too, and plug people in the eye—eh?"

"He can if he's set upon," Tinker answered.

"Who were the other companions with you in this peaceful visit to Whitechapel?"

"Ted Bennan and Joe Cramb."

"And are they medical students, too?"

"Well, as it happens, they are," Tinker replied.

"As it happens, they are!" the solicitor scoffed. "And you and these three medical students just went to the East End to have a look round? Do you expect the Court to believe that?"

"I do!"

"Three medical students out for a frolic and a young hero like you who can make mincemeat of a couple of men!" the solicitor sneered. "You went all the way from the West End to Whitechapel just to give good example to others—eh? Your worship, I submit that this witness is perjuring himself!"

The magistrate was gazing reprovingly at Tinker,

"He is certainly telling a peculiar story, and I should like some corroboration of his evidence," the magistrate remarked. "The facts against him are suspicious. I am afraid he is of a very boastful and imaginative nature. When four young men go into the East End without any business there late at night—"

"And three of them medical students," the solicitor intervened.

"There's nothing against medical students!" Tinker said hotly.

"No; but there is a good deal against you!" the magistrate said sharply. "For one thing, you don't know how to behave in my court! Go down! I have had enough of your evidence!"

Tinker, flushed and indignant, descended from the witness-box. He had not had any desire to come into court at all; it was the police who had insisted on his evidence. In the fight on the previous night he had given the prisoner Rollings just as good as he had got, and he had been quite content to leave the matter at that. He looked wrathfully at the solicitor, who was now smiling in quite a friendly manner. The solicitor by clever questioning had put a false construction on Tinker's conduct, and thus had made the magistrate suspicious of his evidence. He had won, and he could now afford to be friendly.

Tinker sat down, thinking over all, and his anger slowly melted. After all, the solicitor had only done his duty, and he was uncommonly clever. It was his business to save his client in the dock if he could, and Tinker, generous and tolerant by nature, soon began to forgive him.

Meantime, the lady in the veil had entered the witness-box. She stood there, a black-robed and pathetic figure, and all could see that she was trembling.

"Please lift your veil," the clerk said. "You cannot be sworn until you do."

"Your worship, I would ask you not to insist on this," she urged, and the refinement of her voice startled the court.

"I am afraid I must insist, madam," the Magistrate replied. "I cannot make any exceptions here."

She raised her veil, and all gazed at her intently. She had a beautiful face, though age had somewhat lined it, and sorrow had made it intensely sad. Her wonderful large, dark eyes, her finely-chiselled features, the air of dignity so seldom seen in the precincts of a police-court—all had an awe-inspiring effect, even on the most callous who were there. She grasped the dock-rail with two slim, white hands, and swayed a little. Blake half arose as he saw her face. He drew a deep breath as he sank back heavily. Murmuring a few words, he passed his hand across his forehead, and then bent forward. A look of great sympathy was in his strong, intellectual eyes.

"You were in Balting Row at ten o'clock last night?" the sergeant began.

The lady was growing more agitated every moment.

"I must decline to answer any questions," she said.

A murmur ran through the court. The sergeant was completely taken aback. He looked to the magistrate for support.

"Why do you decline to give evidence, madam?" the magistrate asked.

"I cannot even answer that question," the lady said.

A tense silence followed. The magistrate laid down his pen, folded his hands on his desk, and gazed at her.

"I am afraid I cannot accept your refusal," he said quietly. "You have been summoned as a witness, and you are bound in law to tell what you saw. If witnesses were at liberty to give evidence or not just as they liked, then the law could not possibly be enforced, and the guilty could not be punished. I must insist on your answering the questions the sergeant puts to you. I will take care that no question is asked that you are not legally bound to answer."

The sergeant glanced at his notebook and spoke again.

"You were in Balting Row at ten o'clock last night," he repeated.

The lady now could barely stand. Her condition was pitiable.

"Your worship, I will go to gaol if you send me there, but I will not speak," she faltered.

The magistrate gazed at her. The court was in a state of suppressed fever.

"Sergeant, what is the meaning of this?" the magistrate asked.

The sergeant coughed.

"There is something behind all this," the magistrate went on.

The sergeant rubbed his nose.

"Does she live in Whitechapel?" the magistrate asked.

"Yes, your worship, and I think I see now why she won't give evidence. She is afraid."

"Afraid?"

"Yes. The prisoner is one of a gang, and—"

"I object!" the solicitor interrupted, jumping up. "That has not been put in evidence."

"Sit down, Mr. Bricage," the magistrate said sharply. "Go on, sergeant!"

The sergeant glanced triumphantly at the solicitor.

"There are a gang of roughs in Whitechapel, and the prisoner has been often seen by the police in their company, the sergeant explained. "It's my opinion, your worship, that the lady is afraid of them."

The magistrate lay back in the chair.

"The witness is very agitated, and she is hardly in a state to go through the ordeal of an examination or cross-examination." he said. "I will take that into account, and I will not insist on her evidence. I remand the prisoner for a week, and, meantime, sergeant, you will see that the lady receives every protection."

A buzz of approval ran through the court. From the lowest to the highest, all hearts had gone out to the refined and agitated lady in the witness-box. The prisoner was hurried from the dock, and another took his place. The lady descended the steps from the witness-box, and walked, a tall, graceful figure, out of the court, and the sordid day's work continued. Tinker stood up and looked around the court for Blake.

But Blake had gone as unobtrusively as he had come.

Blake Goes to Whitechapel—And Makes a Call.

TINKER elbowed his way through the crowd by the door and stepped into the street. He looked up and down in search of Blake. Failing to see him he walked away, entered a 'bus, and travelled to the West End. He mounted the stairs to the sitting-room in Baker Street, and to his surprise he saw Blake stretched before the fire in an armchair, his head bent forward, and his hands clasped together.

"I thought you were in court, sir," Tinker said.

"Yes, I was there," Blake replied dreamily, "I took a taxi home."

"I didn't do much with my evidence," Tinker said gloomily.

"More than you think, perhaps," Blake replied. "It was very useful."

A puzzled grin spread over Tinker's face. "The magistrate didn't think much of it, anyhow," he remarked. "That solicitor was too quick for me. The way he twisted everything I said—"

"You didn't help the police much," Blake interjected, rising and taking his pipe from the mantelpiece. "That is how your evidence was useful. That young Rollings has been remanded. I expect that when next he is brought up before the court he will have to be discharged."

"Why?" Tinker asked in amazement. "He was one of the chaps in the row. He did set on to me, and—"

"And there will be less evidence against him next time than there was to-day, that is, if I can be of any use," Blake interjected again, loading his pipe quickly. "That poor lady who would not give evidence won't be there."

"You know her, sir?" Tinker cried.

"Yes. I was more sorry when I saw her and recognised her than I have been for anyone for a long time past," Blake replied. "Turn to the index, Tinker, and look up the name Malbred. You might lay the papers on my desk."

Tinker soon had the papers in his hand, and Blake sitting down at his desk took them, and unfastened the strap, holding them together. He glanced at the first few.

"This is the case of Roland Malbred," he said. "Five years ago he disappeared. The lady you saw to-day in the witness-box is his wife."

"Great Scott!" Tinker gasped. "I remember a bit about Malbred. Wasn't he the plausible scoundrel, sir, who started a huge mutual aid society, and robbed the poor right and left? He swindled them out of a couple of millions, so the papers said at the time."

"That is the man, and a more heartless villain never lived," Blake replied. "The police came to me for assistance, but as usual they kept the investigation to themselves until they were completely baffled. Malbred outplayed them at all points. I found after twenty-four hours' work that they had come to me too late, and nothing has been heard of Malbred since."

"And that poor lady living in such misery in Whitechapel is his wife," Tinker said softly.

"Yes, and he treated her even more heartlessly than those he robbed so cruelly," Blake answered, his vibrant voice now ringing with scorn. "My blood tingles when I think of it all. As I saw her in court to-day, the horror of the tragedy came fully over me. And she is so brave—so very brave!"

He arose again abruptly as he spoke, and now he stood on the hearthrug, his dark eyes flashing.

"Who was she before she married, sir?"

"Ah, that's just it! That is where the bitter irony comes in," Blake replied in a tense voice. "You saw for yourself to-day how beautiful she must have been in her youth. Beautiful! There wasn't a lady in all London who could compare with her when she was the darling of Society, the most sought after by men of all ranks. She was the belle of the season, was Lady Nina Geering."

"Lady Nina Geering! That's who she is!" Tinker murmured.

"Yes. The daughter of the late Earl of Brookstuart."

"And she married this man, Malbred?"

"She did. He was the handsomest man in London, with a charm of manner few could resist. He was immensely wealthy then, and everyone thought his company was very sound. The marriage was a great social event; all London flocked to the church."

"And then the crash came?"

"Not for several years. Like all these villains who got control of a great deal of money, he was able by one dodge and another to put off the evil day. In fact, the more extravagantly he lived, and the more he turned the money entrusted to him to his own use, the bolder he became. He issued new circulars, and pretended to extend the volume of his business. He pretended to pay large interest, giving twenty thousand back for every fifty thousand he got. And all the time he was living a life of the greatest luxury on other people's money."

"And his wife?"

"Oh, her father was dead, and a distant relative had succeeded to the title and estates, Mrs. Malbred, whom you saw to-day, was left friendless. She crept into obscurity to hide a broken heart."

Tinker's young face was now very flushed.

"And was that the reason that she was afraid to give evidence?" he asked.

Blake looked oddly at the lad.

"I don't know," was his brief reply.

"But you are going to find out, sir?"

"Why do you think that?"

"Because you said just now that you intend that there will be less evidence against Rollings next time than there was to-day.

"You are right in your deduction," Blake answered. "Yes, I am going to make inquiries. But it is a delicate matter, Tinker; the poor lady shrinks from publicity, she has hidden herself in Whitechapel to avoid ill-natured gossip. What must her life have been there during all these years? I shudder when I think of it. Ah, Tinker, there are many, many sad cases in this wonderful city of extremes, where there is such wealth and such abject poverty and misery. There is not a poor street in any quarter of London where someone is not hiding who has known better days. If only the wealthy were not so thoughtless, but would look into life for themselves, half the wrongs in the world could be righted without all this wrangling and fighting."

He had knocked the ashes out of his pipe, and now he was drawing on his gloves.

"I shall be absent for the day, I expect," he said, in his usual brisk tone of voice. "We're close to the end of the month, my lad. You might check the tradesmen's accounts, and draw the cheques in payment, whilst I'm out, I'll sign them on my return."

He left the house, and sauntered down to his club in Piccadilly. There he lunched, and spent some hours reading the papers. The winter's afternoon was closing in as he took a bus to Whitechapel. Alighting near the railway-station, he walked swiftly down some turnings, until he came to a very narrow street.

The street was very poor, but it had some pretensions to respectability; only at a few doors were the women lounging, there was no corner public-house, most of the windows were clean, one in particular was very bright, and with neat curtains.

Darkness had fallen now, and a lamp at each end of the street threw a murky light for some yards on the muddy pavement. Blake stood and looked long and thoughtfully at this window. At last he moved forward and knocked gently at the door.

The door was opened by a girl about fourteen years of age. She was ill clad and evidently ill nourished, and there was a look of premature age in her small features and eyes, Blake's stalwart, well-dressed appearance startled her, she held the door as if sorry she had opened it, and as if anxious to close it in his face.

"I want to see a lady who lives here,"' Blake said, bending down and looking kindly and reassuringly into her face.

"Mother is out," the girl said.

"It is not your mother whom I wish to see to-day, but the lady who lodges here," Blake explained,

"Do you mean Mrs. Roland, sir?"

"Yes."

"I don't know as she will see anyone."

"Oh, she will see me!" Blake replied cheerily. "She will be glad to see me. I'll just knock at her door."

The young girl allowed him to pass, but eyed him nervously. He gently tapped at a door to the left of the hall. Then he opened it. Seated before a small fire was the lady who had refused to give evidence that morning in the police-court. She was leaning forward in a faded armchair, her white hands clasped together, she was gazing into the fire.

As Blake had said to Tinker he knew the delicacy of the task he had undertaken; he was about to come unbidden into the privacy of sorrow and humiliation, but he must needs do this if he was to bring balm.

"Mrs. Roland!" he said.

Hearing a man's voice the lady turned her head swiftly with a look of terror, that pained Blake deeply, in her beautiful eyes. He was standing with his hat and gloves in his hands.

"I am so sorry to intrude in this way," he urged. "Please forgive me. I won't detain you long."

She stood up agitatedly.

"Why have you called?" she asked.

He put one hand behind his back and closed the door gently.

"Because I am a friend!" he said.

"A friend?" she answered, "I do not know your name, nor do I remember your face."

"Do you think I look the sort of man who would wantonly intrude on a lady's privacy?" he asked. "Believe me, I am not one who uses the word friend lightly, nor would I come here to offer the kind of thing that goes so often by the name of friendship. I am one of the few men who can really help you in your perplexities. I am Sexton Blake, the detective."

As he mentioned his name she gave a great cry, and pushing the chair to one side she advanced to face him. All the timidity had fled, her right arm was outstretched, and under the effects of her excitement she seemed to have grown momentarily strong and young.

"Go!" she cried. "If you refuse, I will turn you out myself. You, a detective, to dare to speak to me! I know the cruel errand on which you have come. Go at once!"

"Madam, I am at a loss to understand your demeanour, or your words," Blake explained. "I have nothing to do with the police—nothing whatever,"

She clutched his arm.

"You give me your word as a man that that is true?" she urged.

"As a man I say so."

"Then you have not come to obtain evidence against my son," she murmured, a ring of intense relief in her voice. And, turning, she fell back half fainting into the chair.

A Bitter Tragedy—Blake's Resolve.

BLAKE quickly poured some water into a tumbler and handed it to the agitated lady. She sipped it eagerly, and gradually the weakness passed away. She struggled to sit up, but he urged her to lie back and rest. In a few minutes he felt he could continue the conversation without causing her undue excitement. All through these minutes he had seldom glanced at her, but she had never taken her gaze from off his face. And the look in her eyes had been searching and hungry.

"I was in the police court this morning," Blake remarked quietly, gazing into the fire, "and I saw that you refused to give evidence. I am not of an interfering nature, and I would not have come here except that I recognised you."

She started. Quickly he laid his hand on her arm, and his smile was frank and winning as he spoke.

"Your secret is sacred to me; let me assure you of that," he urged. "Whatever you tell me will never be made public. But is there much that remains for you to tell me?" he went on reflectively. "I think I know all already."

"Even about my son?"

"Perhaps not all in connection with him," he answered: "but I know the unhappy story of your life. I was not aware you had a son until—"

He stopped and looked into the fire.

"Until when?" she asked.

"Until I saw that young man in the dock to-day, and until you substantiated the opinion I had formed by your admission just now."

"Mr. Blake, can you save him?" she pleaded tremulously.

"From imprisonment?" he asked.

"Yes."

"Yes, I suppose so. There is a bigger difficulty than that before us, though. He must be saved from himself!"

"Ah, if you did know all, you would not judge him harshly," she cried, a sob in her voice. "I took him down here years ago, thinking I was doing the wisest thing, and little dreaming of the temptations that would bestrew his path as he grew up. It's my fault—all my fault!"

"You must not blame yourself for the inevitable," Blake answered. "You came here to hide yourself. And all the years you have been here you have been unable to choose his companions for him. Poverty is a cruel taskmaster. The poor not only suffer privation; they cannot keep their children out of harm's way. But I know much of the world. Do not think I am disposed to judge him harshly."

Her sobs ceased. She gazed at Blake in gratitude.

"You are the first who has shown me true sympathy throughout all my troubles," she said.

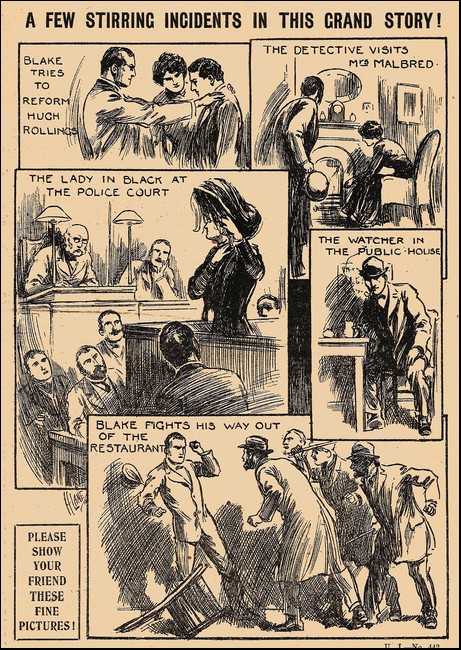

"I intend that my sympathy shall be of a practical kind," he replied. "Now, Mrs. Malbred, let us get to work and discuss everything in a sensible, matter-of-fact way. I am here to help you, and I must recall the past, which you would like to forget, if that was possible, which, of course, is not the case. We will talk about your son first. Evidently he has got into very bad company. What was he like when he was younger?"

"He was always affectionate, but impulsive and quick-tempered," she replied. "I could win him by kindness, but he would never submit to dictation. He played here in the streets with the other children, for there was no other playground for any of them; and many of the children, like their parents, are very nice, but some are very bad. He chose his companions from those who were most independent and daring, and he became very wilful. As time went on and he grew bigger, I lost all control over him. There comes the time, Mr. Blake, when a father's authority is necessary over a son, and he was without a father."

"And so things went from bad to worse," Blake remarked. "From what you have told me of his character he was evidently good at heart. There is hope, therefore, that even yet he may see the error of his ways."

"It is good of you to speak so kindly when I am almost heartbroken and in despair about him," she said. "But how do you think you can help him?"

"He has been remanded, and he will be brought up again before the magistrate in a week's time," Blake explained. "You must not appear in court. I heard the magistrate instruct the sergeant to-day to see that you were afforded proper protection. That is a trifle awkward, because, consequently, the police will come here occasionally. However, we will outwit them. The last thing they would think would be that you could afford to leave the neighbourhood."

"But, Mr. Blake, I don't understand."

"Oh, I will manage all that!" Blake said quietly. "I will take rooms for you in some other part of London, and one evening you will leave here when the police are not about. They will never find you. One has only to go a mile from one London district to another, and one is safer from pursuit than after a journey of ten thousand miles."

"And my son?"

"He will appear before the Magistrate, and you will not be there to give evidence. And for want of sufficient evidence the magistrate will have no alternative but to discharge the prisoner."

"And then?" she faltered.

"Ah, then we must hope for the best as to his future. We can help him, but he must save himself, as I have told you already. Now, there is a question I would like to ask you."

"I will answer any question you care to put to me," the poor lady replied eagerly. "You have given me hope, Mr. Blake, and my confidence in your strength and goodness has grown every moment. I will tell you everything. Do not shrink from questioning me through fear that you may cause me pain."

"Thanks! Why was it, then, that you were in Balting Row last night?" Blake asked. "The sergeant said that you were assaulted and robbed."

"I had gone there to seek my son. I had not seen him for three days, and before that he was keeping very late hours. I had made inquiries about him everywhere, and had been told he had been seen near there. I happened to come into Balting Row just as the fight was going on; and, seeing him, I hurried toward him to implore him to come home. I was pushed to one side and my purse was snatched from me, But he did not know anything about that."

"What does he do for a living, Mrs. Malbred?"

"Ah, Mr. Blake, that is the saddest thing of all," she replied. "When he found out that he had not always been poor, but that if he had his rights he would be wealthy and in a splendid position, he became sullen and hardened. He threw up the small employment he had, and went headlong into mischief. He has done nothing for the last two years."

"The sin of the father visited on the child," Blake said gravely. "It is hard on a mere lad with his life before him to discover that he has been robbed of all that men respect and honour. But he should show more strength of will. Many even in such position have carved out greatness for themselves. And how has he got on for money? I suppose that during these two years you have been struggling to support him?"

"I said I would tell you everything, and I will not flinch," she said, though her voice had sunk to a whisper. "He is seldom short of money, Mr. Blake."

Blake sat silent. The mother's face was now flushed. Both knew that that money could not have been honourably won.

"And how do you manage to live?" he asked presently.

"By dressmaking."

"There was nothing saved for you out of the wreck when your husband disappeared?"

"Nothing. I had eight hundred a year of my own, and he took that, too."

"Did you hand it over to him?"

"No. Somehow he got hold of it."

"It was yours by right? He had no claim to it?"

"None whatever."

Blake took out his notebook.

"You probably know the names of some of your son's acquaintances," he said. "It will be necessary for me to inquire into their lives and characters before I will be able to decide what is best to do about him. Who are those with whom he particularly is to be seen?"

"There is a young man named Dopin who is much with him. Dopin is in employment, though. He is not the worst, either. There is another whom I think is worse company for Hugh. His name is Strom."

"And why particularly do you object to Strom?"

"Because he ought not to be living in Whitechapel at all, Mr. Blake. He is well educated and has seen much better days. He is several years older than Hugh, also; and, again, he speaks of a life Hugh has never known, and has done much to make Hugh bitter. He has taken Hugh up to the West End and shown him all the luxury there, and boasted of all the enjoyment he has had himself. I feared his influence over my son from the first. I don't like his face, Mr. Blake, but Hugh is infatuated about him."

"I will take a particular note of all you have told me about this man Strom,?" Blake replied. "And now, Mrs. Malbred, I will bid you farewell for the present. I will see you again very shortly. And do not give way to despair any more. I do think that you have passed through the worst of your troubles and that things will gradually mend for you."

"Ah, Mr. Blake, if my son would only reform, I could bear all else!" she said, as Blake stood up to leave.

"Well, well! We mean to do our best for him," he replied, smiling cheerily as he held out his hand. "We'll let him know that he is not friendless, and that will help him on."

He left the poorly-furnished room and passed into the bustle of the big thoroughfares. In deep thought he returned to Baker Street, and took his dinner in silence. Tinker, who knew his ways so well, did not seek to make conversation, and during the evening Blake, instead of reading, as was his custom, sat smoking and gazing at the fire. It was close on ten o'clock before he sat down at his desk and went through the papers dealing with the case of Malbred. Close on midnight he stood up and sauntered up and down the room.

"Tinker!" he said.

"Yes, sir!" the lad answered readily.

"I have decided to embark on a rather hopeless venture."

"What is that, sir?"

"I am going to have a try to catch this scoundrel Malbred."

"After all these years!" Tinker cried. "He may be at the ends of the earth. For that matter he may be dead."

"All that is quite true; still, there is a particular reason why I mean to search for him. He robbed his wife of a large sum of money, the interest of which was eight hundred pounds a year. It was robbery, just as much as if he had taken it from me. The fact that she is his wife doesn't make the case less strong in her favour. Now, would it not be a splendid thing if I could recover that money for her?"

"Of course it would, sir! But didn't he come a big smash himself?"

"So it is supposed. My experience, however, from a close study of criminals of his type, has led me to believe that few of these scoundrels ever wait until the very last. They usually bolt before all is lost. They get away with a very comfortable nest egg. And their whole thought in life is money and how to get it. They don't swindle people and bring disgrace upon themselves just out of freakishness. Malbred, of course, may be dead. But if he is alive he is not in want. Men of his kind never suffer that way. They make others suffer instead."

"So you are going after him? I'm very glad, Tinker said earnestly. "When I think of all you told me to-day about that poor lady living in misery in the East End, after the splendid and luxurious life she had in her youth, and she so plucky in the court when she was half-fainting—"

"And there's more I could tell you now, after an interview I had with her to-day," Blake cut in quietly. "Yes, I'm going after Malbred, but it's almost a forlorn hope."

"If he's on the face of the earth you'll get him," Tinker said, with a ring of confidence that brought a smile to Blake's face. "From the way you've spoken, I don't think you were ever more determined about anything in your life."

"I never was," Blake agreed, as he turned out the light. "Now, my lad, we'll get to bed. Good-night!"

Tinker went to his room, but he did not go to sleep. He lay awake, for he could hear Blake walking up and down. And he knew that now there would be no real rest for the great detective until his self-allotted task had been brought to a conclusion, until either he had apprehended the villain who had disappeared years before or had proved conclusively that he was past all earthly punishment.

Blake Sets to Work—And Finds Trouble.

A WEEK went by, however, during which Tinker could not discern any great activity on Blake's part. The great detective spent some hours every morning at his desk; he passed his afternoons out-of-doors; he whiled away his evenings at his club, or reading one of the profound books of which he was so fond; by the fireside at home. Only occasionally during that week did he refer to the Malbred case, and then only to give Tinker some instructions regarding the further comforts of Mrs. Malbred. For, two evenings after his interview with her, he had taken her from Whitechapel to comfortable rooms in Kilburn.

The winter afternoon was closing in now, and the wind was drifting stray flakes of sleet hither and thither in the street below as Blake sat waiting for the return of Tinker. He heard the hall door opened and closed with a loud bang against the wind, and then the lad mounting the stairs. Tinker came into the room, his young face ruddy after buffeting with the weather, and his eyes twinkling. He laughed as Blake looked at him.

"You are right, sir. Rollings has been released," he said.

"Was there much of a fuss, Tinker?"

"There was a bit of a row," Tinker said, grinning. "The magistrate pitched into the sergeant, and that solicitor had a couple of raps at me. When Mrs. Malbred did not turn up he saw the way clear, I suppose, to save Rollings. He reminded the magistrate that at the last hearing the magistrate himself had said that he should want corroboration of my evidence. That was just like his cheek! The magistrate couldn't go back on that, however, and Mrs. Malbred wasn't there, so there was no one to prove the truth of what I had said."

"That is how I thought the case would work out," Blake remarked.

"I never saw a fellow more knocked out of time than the sergeant," Tinker went on. "He just stared at the Magistrate in a helpless, fishy sort of way while he took his lecture for letting Mrs. Malbred leave the neighbourhood on the quiet. Then the magistrate discharged Rollings, and warned him that the police would keep an eye on him, and if he was brought up again he would deal with him severely."

"And was anyone in court waiting for Rollings?"

"Yes. A rough-looking chap, They went off together."

"And you followed them?"

"I did, sir! I saw them enter a house, and I wrote down the address."

"Rollings is Mrs. Malbred's son!" Blake said. Tinker started.

"You must be told that as you are to help me in many ways in this case," Blake went on. "But that fact is to be kept absolutely secret. Mrs. Malbred took the name Roland when she went to live in Whitechapel. She told me all about it when last I saw her."

"Then you have seen her since she went to Kilburn?"

"Yes. Her husband's name is Roland Malbred. That is why she took the name of Roland. Her son has always been known as Hugh Roland, He gave the name of Rollings to the police when he was arrested; I suppose he has some shame left, and he didn't want to bring further disgrace on his mother."

"I understand, sir!"

"Very good! Now give me the address of the house into which he has gone with this other man. I am going into Whitechapel, and it will probably be late before I return, and I intend to disguise myself."

"Half a mo', guv!" cried Tinker.

"What is it?"

"Why did you go to all this trouble to save Rollings? Wouldn't it have been better to have him put away for a while? At least, so it seems to me. Living down in Whitechapel amongst all those scoundrels who are his pals he will only get into bigger trouble now that his mother is not there."

"You have asked a shrewd question, my lad," Blake replied, smiling approvingly. "I have decided, though, that he must take his choice, though from this on I mean to keep a watch over him unknown to himself."

"And why have you taken that course, sir?"

"Because through him I hope to find his father."

"Great Scott! Do you think he knows where his father is?"

"I feel certain that he doesn't; yet his father may know about him. I have not been as idle during the past week as perhaps you may have thought," Blake went on, a humorous light in his eyes. "Night and day this case has never been out of my mind; and I have spent many hours every afternoon in Whitechapel, and I have been making inquiries also in the West End. But I had to wait until Rollings was released before I could get to work. Now I can begin."

An hour later he slipped out of the house, and started for Whitechapel. He was dressed in tight-fitting, black clothes, a bowler hat, boots rather the worse for wear, and a clean shirt and collar, but with frayed edges. His tie, too, had as much worn, and he carried a shabby umbrella and an old pair of gloves. He looked like a man who had sunk from some respectable position in the City into dire poverty.

On the way to Whitechapel he sat in a corner of a 'bus looking very cold and miserable, for he was the only man without an overcoat. When he reached his destination he left the 'bus, and entered a large and brightly-lit public-house. Fumbling in his pockets, he found a penny here and a couple of halfpence there, and, ordering a drink, he went to a small table and sat down alone. Then taking a very old briar pipe out of his pocket, he began to load it from some tobacco, rapped up in a piece of newspaper, taking as much care as if every leaf of the fragrant weed was absolutely precious to him. He smoked slowly, and occasionally sipped his glass.

That public-house was not strange to him. As he had told Tinker, he had not been idle during the past week; in point of fact, he had been extremely busy every afternoon, making a thorough study of this locality. He had tracked a man in and out of this public-house, watching him narrowly, and finding out all about him that he could without creating suspicion against himself, and now he was waiting for him again. The bars filled up as the evening drew on, tradesmen went in and out, artisans and labourers came here as a meeting-place after the day's work to chat with one another. There were no people of a wealthy class, but many were well dressed, and most were respectable. Now and then, however, a small party, evidently of the criminal type, would enter and look around. Blake watched these narrowly, whilst, of course, they took no notice of him.

At last the man he was waiting for came into the bar where Blake was seated. He was the fellow Strom, of whom Mrs. Malbred had spoken to Blake, and he was accompanied by three others. They stood at the counter chatting together in a group, and the great detective had a good opportunity of observing them. He had identified Strom three days before, but the other men were complete strangers to him. They were also of a different class to Strom, who, despite the fact that his clothes were rather shabby, carried himself and spoke differently to the rest. Also he paid for the refreshment that was ordered, and stood in the middle of the group. He undoubtedly was a man to whom the others looked up. And Mrs. Malbred had told Blake that Strom had seen better days. His superior knowledge and education gave him a power over his companions.

As Blake watched them the door was opened once more, and a young man entered the bar. His. manner was nervous, and there was a look of great anxiety on his face. No sooner, however, did Strom perceive him, than he walked towards him with his arm outstretched and greeted him very cordially. Chatting cheerily, he led him to the counter and introduced him to his companions.

"Hugh Rollings! Mrs. Malbred's unhappy son!" Blake murmured, as he sipped his glass. Just as I had expected. Strom has been waiting for his release, and no doubt he sent him word to meet him here to-night. Now that the young fellow is utterly down in his luck, the scoundrel will show his hand.'

The others greeted Rollings in a very friendly fashion.

Strom patted him on the shoulder, and made some remark at which his companions laughed heartily. Rollings soon began to feel at home, and the conversation became lively. Blake could see that Rollings was telling them about his trial, and that the others were deeply interested.

Presently they all left the bar, and Blake followed them. When they were out in the street they separated; Strom and Rollings going in one direction, and the rest in another. Blake followed Strom and Rollings.

To Blake's surprise, they mounted a 'bus and travelled towards the West End. Blake, sitting inside, watched the steps, and they did not get down until the 'bus stopped at Oxford Circus. Then Strom hurried Rollings quickly away. it was getting very late now, the people were pouring out of the theatres, and the pavements and roadways were crowded. So fast did Strom walk down Regent Street and into Piccadilly that Rollings had difficulty in keeping up.

Diving down a narrow lane-way, Strom pushed open the door of a small cafe, and stepped inside, followed by Rollings. Blake hesitated, and looked up and down the lane-way for some seconds. Finally he decided to go in after them, and opening the door he walked up the room and took a seat at a table.

The cafe was rather crowded, and was doing a brisk business. A small recess was at the top of the room to the right of Blake as he sat with his back to the door, and in that recess Strom and Rollings were seated with two other men. So far, none of them had noticed the disguised detective. He slipped from the seat he had first taken to one nearer the recess, and as he sat down someone behind him coughed loudly. Ordering a cup of coffee, Blake loaded his pipe and began to smoke.

Snatches of the conversation between the four men in the recess came to him fitfully, Once Rollings uttered a protest, and Strom, laughing encouragingly, patted him on the back.

"He's just the man for the job, isn't he?" Blake heard Strom ask his companions.

Again their voices sank almost to a whisper, Blake, smoking and gazing at the ceiling, pretended to be in a deep reverie.

"It's a big house full of servants, and you will need to be careful," one of the strangers remarked, after a couple of minutes, and in a voice clear enough to carry to Blake.

Someone behind Blake coughed loudly again.

"We can catch the night mail from Southampton," Strom said presently. "It stops two miles from the Hall."

The closing hour was now at hand, and customers were paying their bills and hurrying homewards. Blake still sat on, listening eagerly, but, to all outward appearance, forgetful of his surroundings. The waiters were beginning to lower the lights, the proprietor had come into the cafe, and was urging the remaining guests to leave. A big man brushed past the table where Blake was seated, and bent down over Strom's chair. Whatever he whispered, the effect was startling. All in the recess turned their heads sharply, and scowled at Blake. Then they jumped up simultaneously.

Blake, too, pushed back his chair, and as he moved from the table someone behind him gave him a push that sent him staggering towards the recess. And at the same moment a hoarse cry went up:

"Out with the lights! Don't let him escape!"

A Fight for Life—Mother and Son—Blake's Doubts.

AT once there was an uproar, Blake was gripped, but swung himself free; a table and some chairs were upset; all the lights were extinguished. Advancing again towards the door, Blake's way was barred by one scoundrel, whilst others attacked him from behind. He hit out fiercely in the dark, but was pushed back into the recess.

The proprietor of the cafe and the waiters, scared at the attack, and fearful for their own safety, left the gallant detective to his fate, and retreated towards the kitchen, where they listened in terror to the din. Blake was fighting for his life, and alone.

But his courage and coolness stood to him. Twice he got through his enemies, but on each occasion he was driven back. The third time he eluded them more successfully, and was down the room and close to the door with a police-whistle in his fingers before they overtook him. He blew loudly on the whistle as he fought to keep the villains back. An answering shout came from the lane, and in the distance the shrill call of another whistle rang forth. Blake was knocked down, but got to his feet as strong men beat against the door. He stood waiting another charge, but none came. As the police dashed into the cafe he saw by the light of their lamps that his assailants had fled.

Some of the police rushed through the cafe into the kitchen.

A sergeant inquired the cause of the uproar from Blake, and whilst the latter was entering into an explanation the police returned from the kitchen, with the proprietors and the waiters under arrest. But the villains who had attacked Blake had got away.

"These men had nothing to do with the disturbance," Blake explained. "They certainly showed the white feather when I was attacked, but they are not liable in law for that. I do not bring any charge against them."

"In that case, as there is no evidence against them I will not take them to the police-station," the sergeant replied. "But after what has happened to-night I will keep a strict watch on the premises," he continued, eyeing the cafe proprietor sharply. "And if this sort of thing occurs again I will know what to do."

As soon as the commotion had somewhat died down, Blake slipped away. He wanted to get back to Baker Street, and think over the scraps of conversation he had heard. He was anxious, too, to avoid any close questioning from the police. Were they to arrest Strom at this juncture, the plans that the great detective had laid already would be upset.

And he believed now that he had got a clue which, in time, might be of the utmost value. Strom and his confederates were urging Rollings on to the perpetration of a crime. They were making him their tool, perhaps, by terrorising him, and perhaps of his own free will. In either case Blake had resolved to save the young fellow, if possible, from a career of further shame for the sake of his mother. The moment had come for action.

When he reached Baker Street, Tinker was dozing by the fire, awaiting his return, and Blake at once aroused him, His first words were enough to make the lad wide-eyed and alert.

"Tinker, you have to get to work early to-morrow morning," Blake said. "There is a man called Strom, a bad character of whom Mrs. Malbred has spoken to me. He was in the company of young Rollings to-night, and together they went to a cafe in the West End. I followed them into the cafe, and their gang attacked me. The police came in, but the scoundrels bolted out of the back door, and got away. I want you to follow up this man Strom, and keep an eye on him. Mischief is brewing, and he is the ringleader."

"And where have I a chance of finding him, sir?" Tinker asked.

"In Whitechapel! I will give you the address of a public-house there that he frequents continually. One of his confederates sitting at the back of the cafe recognised me in spite of my disguise, and warned Strom. He knows, therefore, that I am after him, and so it would be useless for me to shadow him myself. You will have to do that, and you will need to be very careful."

"I'll do my best, sir," Tinker replied cheerily, I suppose I had better leave here about seven o'clock?"

"Yes; I want you to watch his movements for some time. It is not to-night or possibly to-morrow night that he means mischief. See where he goes, what people he meets, and observe for yourself whether he is particularly busy making any kind of arrangements. You will be able to judge when the time has come to report to me. Then hurry here to tell me all you have found out."

"And how will I know Strom?" Tinker inquired.

"Oh, you won't have much difficulty in that! He is shabbily dressed, but he has seen better days. He stands out altogether from his confederates he meets in the public-house in Whitechapel. He is a tall, dark-featured man, slight but muscular. He has a hooked nose and a big chin, and when he is talking he has a habit of putting his right hand to his ribs. That is enough description for you to identify him. You are very quick at that sort of thing. And now, my lad, I wish you the best of luck. You will have left the house before I get up to-morrow morning."

They went to bed, and on the following morning Blake took his breakfast alone. Having attended to his correspondence, he went to Kilburn to see Mrs. Malbred. The visit was painful to him, but he had promised her that he would report anything he heard about her son. She had changed much in the short time since she had left Whitechapel. Her health was better, her face brighter; she was altogether happier. Hope had come to her through Blake.

She came into the room to greet him, her eyes sparkling with pleasure, but his grave manner warned her that he had bad news.

"You have seen my son?" she asked quickly, as they shook hands.

"Yes, Mrs. Malbred; and he is not reforming; in fact, I am afraid he is going from bad to worse," Blake replied. "That villain Strom, for his own purposes, is leading him altogether astray."

"What is Strom doing now?" she asked anxiously, "I did hope he would leave Hugh alone. And Hugh has promised me that he would give up his old life. It seems he is not keeping to his word."

She sighed heavily.

"Then you have written to your son?" Blake asked.

"I did, Mr. Blake. Night and day I am always thinking of him. I hope you are not angry with me."

"I can well understand your feelings, I am not angry at all," Blake replied gently. "But if he knows your address—"

"He has promised to call!"

There was a knock at the hall door, and Blake, walking to the window looked out. Young Rollings was standing on the steps. The great detective turned quickly, and spoke.

"Your son is here," he said, "and on the whole I am very glad. Open the door to him, but do not let him know that I am in the room."

A few moments later Rollings walked into the room, He started when he saw Blake, and his face went white. He turned as if to slink away, but Blake got between him and the door.

"You know who I am," Blake said sternly. "You and I have met before!"

Rollings did not answer.

"We met last night," Blake continued. "Your rascally companions set upon me, and I cannot be sure if you aided them because I was fighting for my life in the dark. You were with them anyhow! If I hand you over to the police you know what your fate will be."

"Have mercy!" Rollings gasped. He was trembling.

"Do you deserve any?" Blake went on coldly. "Look at your mother! You ought to be her protection, yet what kindness do you show her? Instead of being a comfort to her you are breaking her heart. And now you have come to her, I feel sure, just to borrow what little money she may have."

"Spare him for my sake, Mr. Blake!" Mrs. Malbred pleaded. "Hugh, will you promise to reform if Mr. Blake gives you this chance?"

Young Rollings moistened his lips, his tongue was parched with fear.

"I will reform," he muttered.

"And you will give up Strom and his rascally gang?" Blake demanded.

"Yes, I will!"

Blake looked steadily at the miserable young fellow, whose eyes fell before that frank, piercing gaze. His head sank, and he fidgeted his cap nervously.

"What hold has Strom on you;" Blake went on.

Rollings started.

"He has no hold on me!" he muttered.

"Then why do you keep in his company?"

"Because I am penniless and he is generous!"

"And you expect me to believe that a man like Strom can be generous without expecting something in return?" Blake scoffed.

"He has no hold on me, anyhow!" Rollings said doggedly again.

Blake walked to the window. Mrs. Malbred had been listening in fear and sorrow to the conversation. Now she put her hand on her son's arm.

"Promise me, Hugh, that you will lead an honest life from this on!" she urged. "For my sake take the straight path again."

He looked down into her worn face, and his lips twitched.

"I have given that promise," he said.

"You are not holding back again from us, Hugh?"

"No."

"Mr. Blake, will you forgive him?" she asked.

"If he doesn't do anything underhand from this on I will forgive him," Blake said. "He can go now if he likes."

Rollings slunk out of the room. Blake, still standing by the window, watched him going down the street, until he was out of sight. Then he turned to Mrs. Malbred.

"I had no intention of arresting him, but nothing but stern treatment can do him any good," he said. "Kindness would be wasted on him. He would only trade upon it. He must raise himself up, and prove himself a man. No one can do that for him."

"He seemed very sorry just before he left," Mrs. Malbred said earnestly. "This may be the turning point in his life."

But Blake, with his deep knowledge of human nature, was not prepared to agree with this view, much as he would have liked to be able to do so. He had seen the sullen look on young Rollings' face, and he knew what it indicated.

"Let us hope for the best!" he said. "In spite of all he has reason to be ashamed of, I believe he is fond of you, and that is in his favour. If he does break away from Strom he may redeem the past."

Tinker on the Trail—What He Saw—Caught!

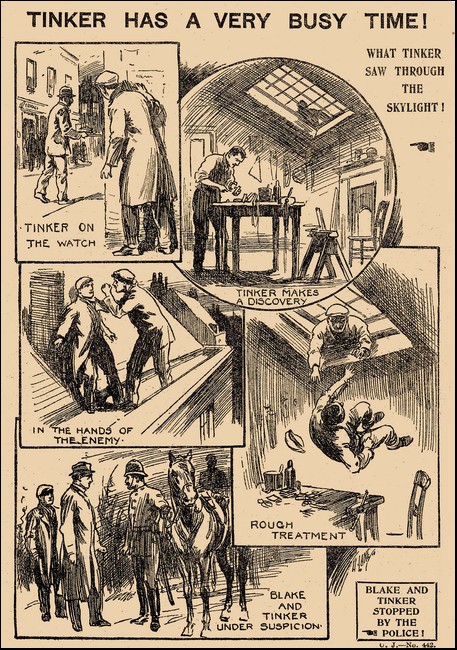

TINKER tumbled out of bed in the best of spirits that morning, and, after a hearty breakfast, he crept down the stairs, and left the house. He was never afraid of hard work or long hours on duty, and the task allotted to him by Blake was quite to his taste. He was always glad when responsibility was placed upon him. He liked to feel that he could be of real help to Blake, and he took a keen enjoyment in working on his own account.

Now, as he walked down the street, his overcoat buttoned and his hands deep in his pockets, anyone who glanced at him would have thought that the lad was on his way to an office like so many thousands to be met with at that hour in London. All would have been astonished had they known the mission on which he was bound. They would have been even more amazed had they watched him during the day.

Stepping on to a motor-bus, he travelled down to Whitechapel, observing everything as the 'bus sped along. The pavements of the City were becoming crowded, the early and most cheaply paid of the great army that draws its living from there was marching along in a steady file, gathered together from all the outlying suburbs. For these one day was like another—an early start from home, and a return late, five days of the week, a half holiday on Saturday, and a full day's rest on Sunday. To Tinker every day was different. There was always excitement or the prospect of it, and he was wise enough to appreciate how fortunate he was, thanks to the great detective, who was his friend as well as his employer.

He sat on the 'bus, noting the change in everything, in the buildings, the people he passed, the luxury at one end and the gradual transition to poverty as the 'bus drew near Whitechapel. Arrived there, he got down, and proceeded at once to his own work. And from that on he thought of nothing but what he had been set to do.

The public-house was open, and a potman was polishing the windows as Tinker strolled by. A brewer's van was unloading barrels, and a couple of loafers had already gathered by the door. Tinker's first course was to find some spot from which he could watch the public-house without attracting attention to himself, and at that early hour with the street rather deserted this was not an easy thing to do. However, a cheap restaurant opposite the public-house was open, and though he was in no need of a meal he decided to go in there first, and so spend an hour. He ordered a cup of coffee and some bread-and-butter, and sat down at a window.

Gradually the street became more filled, costers began to line the kerb with their barrows, goods from the shops were carried out, and placed in front, people began to buy their provisions for the day. When Tinker felt he could no longer stay in the restaurant, there was an air of bustle in the street, and he was able to saunter up and down without anyone taking any notice of him. Sometimes he got into conversation with other lads. In every way he could think of he sought to avoid suspicion, and all through those hours no one entered or left the public-house unseen by him.

It was close on eleven o'clock when his patience was at last rewarded. A man corresponding to Blake's description of Strom drove down the street in a taxi, and alighted at the public-house. Tinker at once crossed over, and pushing the door a few inches ajar, he peeped in. The man was talking to someone in the bar, and his manner was surly. Occasionally he fingered his face, and, looking more closely, Tinker saw the man had a black eye. He chuckled heartily. In the row in the cafe on the previous night Blake must have given him that!

"All right, Mr. Strom!" he heard his companion say. "I'll tell him your message when he comes here this evening!"

Tinker softly closed the door, and crossed the street again. He had heard all he wanted.

Presently Strom came out on to the pavement, and stood for some moments looking up and down. He sauntered away, and Tinker followed him. Strom went on for quite half a mile, taking several turnings in a way that suggested the maze of streets was well-known to him. He entered an iron-monger's shop, but instead of going to the counter he walked straight to a room at the back. The proprietor followed him, and when the latter came into the shop again he opened a drawer and took out a handful of keys, each of which he examined carefully. Tinker's interest grew deep as he observed this. What did Strom want with a key, and why could he not buy one without all this secrecy?

When Strom left that shop he went to a post-office, and spoke on the telephone. Then he took a walk in a different direction, and presently he entered an old clothes' shop. He came out with a small bundle under his arm, and went down an adjacent street. He knocked at a door which was opened almost on the instant by a squarely-built, evil-looking fellow, with an ugly squint. Strom stepped swiftly across the threshold, and the door was closed.

After this Tinker had many weary hours of watching and waiting. Strom did not come out again. Once the lad saw the man with the squint going to a restaurant, and returning with a meal on a tray covered by a napkin. Later on in the afternoon the same man came again out of the house, and he bought some tobacco and an evening paper. The day closed in, and twilight gave way to complete darkness, but Strom did not emerge. Whatever was he doing in that house?

The lamps were lit in the street, and in the houses around, but that house remained in darkness. Strom was not sitting there without a light. Then he must be in a room at the back. No sooner had Tinker come to this conclusion than he set about thinking how best he could find out what Strom was up to. He hurried along the street, and went down a lane-way. He did not know that a man crossed from the shadow of a wall, and stood gazing after him as he slipped down the lane.

The lad got to the back of the house. The only room in which there was a light was at the top, close to the roof. To get to the house Tinker would have had to climb over a wall and cross a yard, and it was just possible that a door might be easily opened, or that he could raise a window without being heard. But the attempt would be very hazardous, and there were two men for certain in the house. He stood undecided what to do, when, suddenly, he saw a ladder raised against the back of another house some forty yards away. That house was being done up, and the workmen had left the ladder there after their day's work.

Tinker came to a swift decision; all seemed easy now. He went farther down the lane, got over the wall, crossed a yard, and reached the ladder without anyone coming out to question him. Up it he went quickly, and on to the roof. Then, crouching low, he crept along the slates. He got to a skylight, and looked down. Strom was in the room and alone.

Tinker lay flat on the slates, gazing through the skylight, his mind full of excitement, and his eyes shining. The room was fitted up something like a mechanic's shop, and a small crucible was on the fire. On the table were many sorts of tools—tools not sold to customers in the ordinary way of business. Some were straight and some were oddly crooked, most of them were very small and blunt. But Tinker knew them, though they would have been a puzzle to many. They were an expert burglar's outfit, and a very extensive one, too.

Strom was bending over the table when first Tinker saw him, and he was trying to fit a key into a lock. Presently he began to file the key; after some time he succeeded in turning the lock with if. He put the key into his pocket, flung the lock into a drawer, and began to make a selection from the tools on the table. He laid four together, and put the rest in a cupboard. Then, opening the parcel he had bought at the old clothes' shop, he held up a rough suit of clothes to the light for closer inspection.

There was a pair of corduroy trousers, and apparently they looked too new, for he began to stain them with an acid, Then he rubbed ashes on to them. He did the same with a coat and vest, and in them he carefully stored away in various pockets, the tools still remaining on the table. After this he took an old cap and a thick pair of boots from a press. Finally, he took out two masks.

He began to change into these clothes, and Tinker knew he was at last about to leave the house. Tinker would need to be back in the street before Strom came out, or he would lose him altogether, and now he was all eagerness to follow him. He crept away, and began to retrace his steps towards the ladder. Suddenly he stopped, and his heart began to thump loudly. For a man was on the roof and was coming towards him. That man must have come up the ladder, too.

Tinker lay flat close to a chimney-stack, his face just raised sufficiently to observe the man's movements. And his heart sank lower as he watched. For the fellow was not coming towards him swiftly, but very deliberately. He looked around every chimney-stack as he advanced. The was searching either for something or someone. As he came close to Tinker the lad tried to creep round the chimney-stack. There was a stifled imprecation, and the man's hand came down like a vice on his neck.

"Ah, you copper's nark!" a hoarse voice growled savagely. "I've got you, have I? You didn't know I saw you going down the lane; and that I watched your tricks!"

The ruffian was pressing Tinker's face hard against the slates, and the lad was struggling desperately to free himself.

He kicked and wriggled at imminent risk of rolling off the roof, but he could not get away. Suddenly the ruffian lifted him easily to his feet, and propped him with his back against the stack. Holding him by the throat, he shook a huge fist within an inch of the lad's nose.

"Cry out, or attempt to move, and you'll get that, and you won't want any more!" he hissed. "You've come here sneaking in order to get others as good as you into trouble. Well, it's you that's caught now, and no mistake."

He released his hold on Tinker's throat and grabbed the lad's shoulder.

"Come along quietly! he snarled. "Else I'll pitch you off the roof!"

"Where are you taking me?" Tinker gasped, for he could hardly draw his breath.

"To those you were spying on, and they'll know how to deal with you!" the bully answered, as his grip grew harder. "Now, get a move on you."

So saying, he partly led and partly dragged the lad towards the skylight through which he had watched Strom.

Baulked—The "Smart" Patrol—Frustrated.

RAISING the skylight, the bully lifted Tinker up, and then dropped him. The lad fell with a crash on to the table; one leg of which broke, and he rolled to the floor. He was on his feet next moment as his captor, swinging from his hands on the skylight edge, prepared to drop down gently. Tinker made for the decor, opened it, found there was a key in the lock outside, and banged and locked the door as the villain dashed to stop him.

Down the stairs Tinker rushed headlong. Heavy footsteps came thumping up the stairs; and he knew that the man with the squint had heard the row, and was hurrying up to find out the cause. Meantime, the man locked in the room was crashing against the door, and the wood was splintering. The lad's quick wit did not desert him.

"Police, police!" he shouted. "They've got into Strom's room, and they're coming downstairs! Scoot while you've got the chance!"

The villain with the squint was startled by the shout. The cry that the police were in the house was enough at any time to fill his evil heart with alarm, and the banging and the tending of wood upstairs gave conviction to Tinker's warning.

He turned and went down the stairs, almost falling in his desperate eagerness to escape, He pounded along the hall, flung the door open, and ran down the steps. Tinker was close on his heels.

The lad was very wrathful at the rough usage he had received; his back was aching. and his throat was sore from the savage clutch of the bully's fingers. The man with the squint once in the street, was anxious to see who had given him the warning; as he half turned, his legs spread out awkwardly, Tinker tripped him up, and sent him sprawling in the mad.

"That's just to pay out your rascally pal!" he shouted, as he sped away. "I've fooled you both at the finish!?"

He did not look back, but sprinted along the street as hard as he could go. As the man with the squint picked himself up, his clothes plastered with mud, his hands and knees scraped by the fall, and his ugly face comical in its astonishment and fury, the lad was turning the corner. Tinker ran on until he got to a main thoroughfare. Then he jumped on to a 'bus bound west.

He got off the 'bus at Oxford Circus, and hurried on foot to Baker Street. Glancing up at the windows as he drew near to the house, he saw a light in Blake's sitting-room, and he ran up the stairs, entered the room, and began to speak almost breathlessly.

"Strom has gone out with a disguise on and a mask in his pocket," he began.

Blake, who was at his desk, pushed back his chair and stood up. His face was very keen.

"Where has he gone?" he asked.

"I don't know, sir! It wasn't my fault that I couldn't follow him. I was on a roof watching him through a skylight, and I was nabbed on the slates. I managed to get away, and I've hurried back!"

"You're certain about the disguise and the mask?"

"Yes, I've been shadowing him since eleven o'clock this morning. I know where he bought the disguise, and the room he was in is full of burglar's tools. He's taken four of the tools with him!"

"Burglar's tools!" Blake cried, his excitement growing more intense every moment. "Then I know what he's up to. You've done well, Tinker—very well. Now, we'll get off at once and try to pick up the trail."

Tinker's face grew long.

"At once!" he faltered.

Blake shot a swift glance at him.

"Ah, I forgot!" he said. "We can wait ten minutes. You must be very hungry. Make the most of the time." Tinker went to the sideboard and began to carve a joint of beef. He ate ravenously whilst Blake continued speaking.

"The burglary is evidently to be attempted to-night, he said, "somewhere on the line between Southampton and Waterloo."

"How do you know there's to be a burglary?" Tinker asked in a thick voice as he devoured the food.

"I overheard scraps of conversation in the cafe," Blake replied. "Of course, we could go to Waterloo and watch there for Strom, but he may get on the train at Vauxhall or Clapham Junction. It's a pity you had only an opportunity of seeing him. Now, if you had heard anything—"

"I did hear something," Tinker interjected. "I listened to Strom whilst he was in the public-house. He was talking to a man there, and I heard the man say that he would give someone a message."

Blake, who was striding up and down the room, stopped and gazed at the lad.

"Then it is as I feared," he said. "Young Rollings does not mean to reform. He promised his mother and myself to-day that he would do so, but his face was sullen, and there was a shifty look in his eyes. Strom has some terrible hold on him. We must find out Rollings and follow him. That is the way we will get to Strom. I'll call a taxi at once."

"And I'll cut another hunk of meat and bread and be down in the hall in a jiffy!" Tinker said, "Oh, dear, I didn't know how downright hungry I was until I started on the grub! I feel I could go on for ever."

A few minutes later they were in a taxi speeding towards Whitechapel. They alighted when close to the public-house, and Blake bade Tinker enter it and look for Rollings; he was afraid he would be recognised himself had he done so. Tinker came out in a few seconds, his face bright and his eyes shining.

"He's in there right enough, talking to a couple of men," he said.

Blake gave a big sigh of relief.

"Then we have only to follow him and we'll come up with Strom and stop the burglary," he said. "It will be an exciting time for us both, my lad."

Tinker chuckled softly.

"I've had a fair time enough already," Tinker replied with a grin. "One never knows what fun the day is going to bring. Just half a mo', sir! There's a bun-shop yonder! A few cakes would fix me up nicely now!"

He darted into a shop and came out shortly with a bag in his hand. As he munched one of the cakes Blake moved along the pavement.

"There's Rollings just leaving the public-house, and he's alone," he said. "Now, Tinker, we must follow him cautiously. You go on first and keep him in sight, and I will keep you in sight. In that way, he won't have a chance to recognise me, and still I will be in touch with him."

Rollings walked swiftly away, but he did not look very cheerful. His head was bent and his shoulders were stooped. He took a 'bus to Cannon Street, and from there he went by train to Waterloo. There at the main line he entered another train bound for Southampton. As the train ran into Vauxhall, Tinker popped his head out of the window of the compartment close to the guard's van where he and Blake were seated. He quickly drew it in again.

"Strom is on the platform," he whispered.

"You're certain?" Blake asked.

"I can't be mistaken, sir," Tinker replied; "but no one would ever recognise him in the disguise he has on."

The train rolled away on its long journey. At every station at which it stopped during the next hour Blake made certain that Strom and Rollings did not get out. When they did alight, it was on to a platform where there were very few passengers. They both were clearly visible as they hurried along and left the station. The way lay down a winding country road, the night was dark, and a fresh breeze was blowing.

Blake and Tinker, following them cautiously, first saw them on ahead as a motor leaving the station having picked up a gentleman from London, flashed its bright light along the road. Strom and Rollings stood to one side to let it pass.

They came to a cross-road, to one side of which lay a village. Strom did not go through the village; Blake saw him crossing the road by the light of a lamp-post. After that there was darkness all the way. On and on Blake and Tinker Went, not knowing the moment when they might see them again. At last Blake spoke:

"How far do you think we are from the station?" he asked.

"A couple of miles, I reckon," Tinker replied.