RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

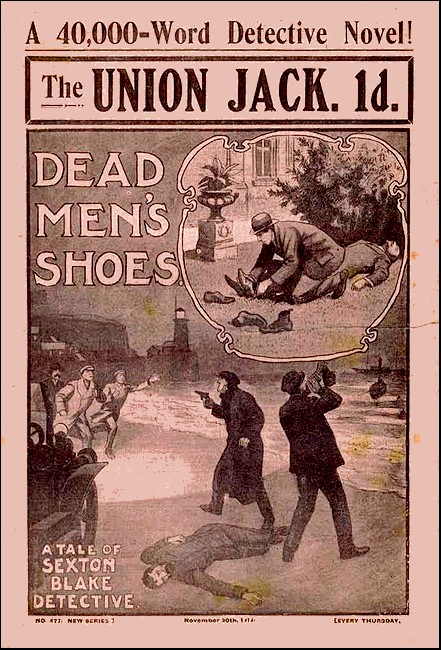

The Skipper desires to draw his readers' attention to the fact that "DEAD MEN'S SHOES" has been written expressly for this issue of the UNION JACK.

SEXTON BLAKE: The Great British Detective.

TINKER: His Clever Young Assistant.

PEDRO: Blake's World-famed Bloodhound.

WILLIAM SAUNDERS, alias JIM FORD: Jim Carson.

HARRIS: Butler to Mr. Alliston.

JAMES: Groom at Alliston Hall.

JOHN ALLISTON, alias WILLIAM TORRENCE: Heir to Alliston Hall.

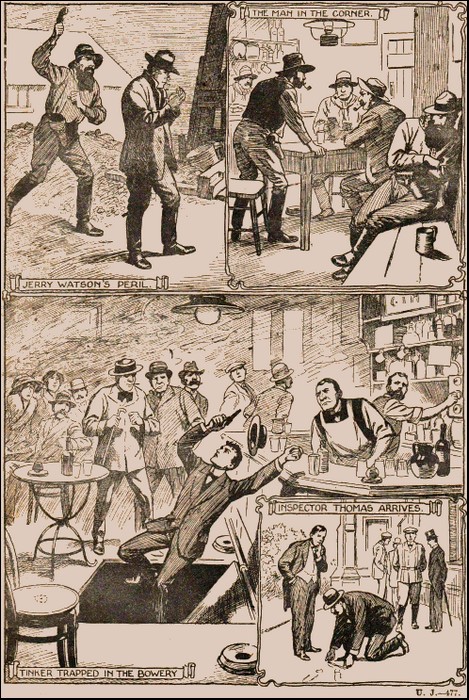

The Red Dog Saloon in Nevada - The Faro Game - The Murder.

"THE Jack wins and the seven loses; the four wins and the three loses; the two wins and the ace loses."

The voice of the faro dealer, who sat at one end of the table, went on monotonously as he pulled the cards from the dealing-box and turned them face up on the table.

At the other end sat the case-keeper, while between them was the solitary player, placing his bets as he lost, and collecting his very occasional winnings as they turned up.

The room was lit by a smoky lamp. Behind the player ranged a rude bar, typical of the Nevada mining camp in the earlier days of the Tonopah rush, over which lounged a tough-looking barkeeper, imbibing some of his own poison, many bottles of which decorated the shelves behind him. He was watching the game with a languid interest. On a bench in the corner lay a man, the abandon of whose attitude indicated a drunken stupor.

It was past two in the morning, and the silence was only broken by the droning of the dealer's voice and the clink of the player's money.

The player was a big man, as even his slouching position at the table showed. He was young, almost a boy, with a frank, engaging countenance, and pleasant eyes which were clouded at the moment with the tense look of the gambler.

Luck had been dead against him all the evening, and he had been doubling and re-doubling his stakes in the hope of a turn. But that it was past two in the morning, and the dealer still sat at the table, testified to the fact that he was a profitable customer.

Earlier in the evening the place had been crowded with miners, but they had all departed with the exception of the player and the drunken individual in the corner.

"Your luck's a bit off to-night, Torrence," remarked the dealer, as he tore the wrapper off a fresh pack of cards. "If I were you I'd cut it out for to-night."

"Go ahead with the dealing, and don't waste so much time! Keep your voice for those that need it!" growled the man called Torrence, in reply.

"All right, old man; keep your shirt on! It's your funeral, not mine," grinned the dealer. "Place your bets! The six wins and five loses; the seven wins and the four loses; the three wins and the ace loses." And so the game went on.

Pushing his chair back from the table with an oath, the player rose to his feet.

"Better come and irrigate," he remarked. "You've got me cleaned out to-night all right."

"You've had bad luck on the ace and the seven," the dealer said, rising. "You've been playing them to win all the evening, and they've lost every time."

"I never saw such a run in my life," said the case-keeper, joining them at the bar. "If a man had played the cards to lose what you played to win, he'd have broke the bank."

"Well, come on, barkeep, fill them up! I suppose it's five minutes since you had one yourself, and since you are not a camel, you had better join us," Torrence sarcastically remarked.

"Waal," drawled the barkeep, "I reckon it would make even a camel thirsty to watch you burning holes in the table. How about our weary friend in the corner? Is he joining?"

"I guess not," grinned the dealer. "His last intelligent state was over two hours ago, when he was entertaining himself with a very careful recital of Paul Revere's Ride. Well, here's better luck next time!" he remarked, tossing down his drink. "If you want a hundred to stake you, Torrence, you're welcome to it," he added.

"No, thanks!" replied Torrence. "I think I've had about enough. I'd be a bit suspicious of the game if it was anybody dealing but you, Jerry. By the way, Haynes," he asked, turning to the case-keeper, "what cards are left in the dealer's box?"

"There is a ten and a seven," replied the man, looking at his record.

"How much will you stake against that on a last turn of the cards, Jerry?" asked Torrence, pulling a folded paper his pocket and passing it to the dealer.

"Where did you get this?" inquired the dealer, looking at him quickly. "And is there much there?" he added.

"I found it myself, and made that plan out. It's simply full of the stuff, but needs machinery put in to crush the quartz, and that's why I was trying to get a turn on the table to-night. It's all straight. You may take my word for that. There's a million in that mine," he added.

"I'll tell you what I'll do," replied the dealer. "You pick on the last turn of the cards, and I'll stake you twenty-five thousand dollars against this plan."

"Done!" snapped Torrence, banging the bar with his fist. "Give us another drink, Camel, for luck!' he shouted.

As the quartet lifted their glasses, none of them saw the man in the corner quietly shift his position so that he might have a better view of the table.

Resuming their positions, Torrence leaned his head on his left hand, and it might have been seen that the little finger was missing. He stared at the dealer's box, as though he would perhaps find some information in its shining silver sides as to which would be the winning card.

"Only the ten and the seven left," he muttered. "and that cursed seven has beaten me all the evening! I've played it steadily to win, and it's lost all the time. The chances are if I play it this time to lose, the hanged thing will win. I'll play it again to win." :

"Well, Torrence, which is it?" asked the dealer.

"Go ahead! I'll pick the seven again to win!"

The atmosphere of the room was tense. The barkeeper leaned, fascinated, over his bar, and the case-keeper's fingers shook nervously as he lit a cigarette, while even the dealer, accustomed as he was to playing for fortunes in a single throw, felt the excitement of the moment. Apparently the coolest of the lot was Torrence, who was risking all he had in the world on that one turn of the cards. But none of them noticed the interest displayed by the man in the corner, whom they all thought was in a drunken sleep.

"You decide on the seven to win, do you?" asked the dealer, wetting his finger.

"Yes. For Heaven's sake turn it up, and let's get it over!"

"The ten wins and the seven loses!" called the dealer, endeavouring to keep his voice steady.

"That finishes it!" ejaculated Torrence, pushing over the plan to him. "I thought that seven would beat me again. I could take you and your table and dump you down the Mogul Mine!" he growled, getting to his feet. "Good-night!" he muttered, stumbling to the door and banging it after him.

"Have a drink before you go?" called the dealer. But Torrence did not hear him. "Well, it's been a good evening," he continued. "A clean ten thousand in cash from Torrence, besides this plan of his; and it's worth a hundred thousand dollars if it's worth a cent. You'd better wake up old sleepy head, and toss him out," he added, turning to the barkeeper.

And as he spoke, the man in the corner gave a resounding snore.

"All right," answered the barkeeper, pouring out a glass of whisky as he spoke, "I'll just give old Rip Van Winkle this, to keep him awake till he gets home."

He walked over to the recumbent figure in the corner, and shook him violently.

"Come on, my pretty child, and smell the beautiful flowers!" he yelled in his ear, holding the whisky under his nose.

The man roused himself heavily, and as he brought his arm down from his head he hit the tumbler in the barkeeper's hand, and it fell to the floor with a crash.

"Come on, Jumbo! You've spilled the only drink you'll get here to-night. Wake up!" And the barkeeper jerked him to his feet, where he stood blinking in the light, as though still under the influence of the liquor.

Dragged to the door and assisted through it by the barkeeper's foot, he lurched up the embryo street of the mining camp until he had disappeared from the path of light which shone through the window of the saloon.

Inside the saloon, the faro dealer and his assistant had gathered up their money and their belongings, and the barkeeper had collected his cash. Turning out the light, they emerged from the saloon, and stood chatting for a moment. The dealer bade the others good-night, and, turning, struck off for his camp, while the barkeeper and the assistant strolled off in the opposite direction.

As the dealer swung off up the trail towards his own cavern, he was probably engrossed calculating his profits of the night, for he did not see a dark figure which stealthily followed him, gradually drawing nearer and nearer as they approached the deep shaft of the mine.

As he turned the corner of the pile of tailings, he paused to light a cigarette. That match was the last he ever struck! The man following had crept closer and closer, and as the dealer lifted the match to his cigarette, he brought down the butt end of a Colt's revolver with crushing force on the back of his head.

The dealer dropped like a shot. His assailant leaned over, and, opening his coat, rifled the pockets, transferring the contents to his own. Picking up the senseless form of his victim, he dragged it to the mouth of the mine shaft, and pushed it over. He stood listening as the body fell, but the sound of its arrival at the bottom did not reach him in that thousand-foot shaft.

He turned and kicked some of the loose tailings over the marks of his footprints, and, pulling a flask from his pocket, coolly took a long drink. He slipped the flask back in his pocket and stole up the trail.

Torrence sat before an almost dead fire in his rough hut. His elbows rested on his knees, and his chin in the palms of his hands.

For hours he sat there, motionless, his lips moving silently at times. His eyes were hard, and his jaw squared, as he raised his hand and spoke.

"The last time—I swear it! Not another card will I touch again! Everything gone! Nothing left! Not even my name!"

And he laughed harshly.

"To think that I, John Alliston, should come to this. Thank Heaven, I have at least achieved my ruin under the assumed name of Torrence! I should have destroyed my private papers long ago. To-morrow I will do so, and again change my name. I'll have to go back over the mountains, and try my luck at finding another claim. What a fool I've been!"

And he groaned.

"That claim I lost to-night would have rivalled the Mogul. But never again, I swear it!"

With which final resolve he rose, and, stumbling to the cot in the corner, threw himself down fully dressed. Five minutes later he was in a heavy sleep.

He could have been a much lighter sleeper and still not heard the silent figure which noiselessly opened the door; and crept stealthily across the room. Even the new-comer's hand, feeling cautiously in the pockets of the sleeping man's coat, did not waken him; and a smile of triumph told of the intruder's success as he pulled some papers from Torrence's pocket, and glanced hurriedly at them.

A moment later he had glided to the door, and was soon lost in the mist and darkness.

The Arrest of Torrence—The Trial—Sentenced to Life Imprisonment.

TORRENCE was awakened by the sound of many voices and the trampling of heavy feet. He sat up, and rubbed his eyes, staring stupidly as angry words broke on his ears.

"There he is; lynch him!" cried several voices. And the amazed Torrence dropped his hand to his hip.

"What do you mean? What is the matter?" he asked, suddenly wide awake.

"Matter!" they cried. "You ask what the matter is? Is it such a small thing to toss a man down the Mogul Shaft?"

"Toss a man—" began Torrence, but broke off, as a big man pushed aside the crowd of rough miners, and addressed him.

"See here, Torrence," he said, "as a private citizen, I respect you; but as sheriff I've got to do my duty, so throw me your gun!"

Torrence complied with the request, and waited for more.

"I've got to arrest you," continued the sheriff, as he thrust the revolver in his pocket, "for the murder of Jerry Watson, the faro dealer!"

"What!" gasped Torrence. "I don't understand!"

"He can bluff all right!" growled a miner in the rear; but closed up as Torrence glanced quickly at him. east

"Listen, sheriff!" said Torrence. "This is all Greek to me. Do I understand that Jerry Watson has been murdered?"

"Yes."

"Where?"

"He was thrown down the Mogul Shaft."

And the sheriff shrugged his shoulders, for he believed Torrence to be bluffing.

"But why am I accused?" asked Torrence, bewildered.

"You were playing faro in the Red Dog last night, weren't you?" inquired the sheriff.

"Yes; but—"

"You lost a plan of some claim which you had found somewhere, didn't you?"

"Yes; I found gold beyond the northern range last week."

"Well, the case-keeper and the barkeeper both say when you got up from the table you were sore at losing and said you could throw Jerry and his table down the Mogul Shaft. Jerry was found dead at the bottom of that shaft this morning."

"But there was another man in the saloon also!" protested Torrence.

"Only Jim Carson," replied the sheriff. "He was drunk when he left. I've already been at his shack, and searched him. He was still in a drunken sleep, and we found nothing. It would have been impossible for him to do it. No, Torrence; it's no good bluffing! You'll have to come with me, but I'm going to search you first."

"I've only got some private papers in my coat—" began Torrence as he thrust his hand into the inside pocket; but his jaw dropped as it came back empty. "I've been robbed!" he gasped. "There's some devilish trick, sheriff!"

"I guess that's no good, Torrence!" grinned the sheriff, "I'm not a boy to be fooled so easy!"

A close search by the sheriff and the miners failed to reveal anything.

"He's hidden them!" growled several.

But though they tore up the boards in the floor, and looked in every possible place, they found nothing.

The sheriff finally gave it up, and led the puzzled Torrence away.

Seeing his word was laughed at, Torrence said nothing more about the papers; but he racked his brains to clear the mystery of their sudden disappearance. He knew they had been there when he lay down, but no explanation came to his bewildered mind.

The little court-room was packed with interested spectators. The prisoner, William Torrence, was fairly well known, but the deceased faro dealer, Gerald Watson, was known far and wide, and the finding of his dead body at the bottom of the Mogul Shaft had resulted with the arrest and charging with murder of Torrence.

Intense interest centred round the trial, and at the end of the argument and cross-examination it seemed a foregone conclusion that the prisoner would be convicted.

He had consistently denied all knowledge of the affair, but the circumstances as outlined by the prosecuting counsel pointed strongly to the prisoner's guilt, and as the judge started to deliver his address to the jury, eager suspense sat on the faces of the spectators.

"Gentlemen of the jury, you have heard how the prisoner at the Bar, William Torrence, was gambling in the Red Dog saloon. You have heard the sworn evidence of the barkeeper at the saloon, and of the assistant of the deceased, that the prisoner said before leaving 'He could toss the deceased and his table to the bottom of the Mogul Shaft.' James Carson, the other occupant of the saloon, is of no use as a witness, for he was not in the condition to hear anything that was said. You have heard how the barkeeper and the assistant went home together, while the deceased went off in the opposite direction alone. You have heard how the deceased faro dealer, Gerald Watson, was found dead the next morning at the bottom of the Mogul Shaft. For the defence you have heard an uncorroborated denial, but the character of the accused was of the highest until the occurrence of this unfortunate affair. I charge you to consider the evidence you have heard, and, without fear or favour, decide in your minds whether the prisoner is innocent or guilty. You will now retire!"

Twenty minutes later the jury filed in and took their places. The judge stood up.

"Gentlemen of the jury, do you find the prisoner guilty or not guilty?"

"Guilty!"

"Stand up, William Torrence! You have been judged guilty of a most cowardly crime by a jury of your. fellow-men. I have no remarks to make on the subject, but it is within my province to mitigate your sentence. In view of the fact that no incriminating evidence has been. produced other than the remark you made in the Red Dog saloon, and that you have been convicted on circumstantial evidence only, I am going to exercise my privilege. Instead of sentencing to death, I sentence you to the State Prison for the rest of your natural life!"

The prisoner at the Bar turned deathly white at the sentence, but did not falter. As he was led away by the warders, he saw at the back of the court-room a man whose features were vaguely familiar, with a sardonic smile on his face.

Ten Years Later—The Prison Fire—Torrence Leads the Rescue—Pardoned.

THE great State Prison lay wrapped in darkness. Its unyielding outlines stretched as a darker blotch against the darker sky. The encircling, forbidding walls prevented any light from showing, but, inside there was an occasional gleam. The steady pacing of the guards in the corridors broke the silence within the walls, accompanied by the restless murmur of a new arrival or the tortured raving of a prison-sick mind.

Convict No. 6072 lay sleepless on his hard bed. Ten years of prison life had aged him, and the continual thought of injustice had embittered him. No light of hope shone to him through the grey walls, and he had abandoned himself, in despair, to the living death.

"Life," he whispered to himself—"a life sentence for nothing! I wonder how many are, like myself, living the prison life of shadowed hopes, innocent of wrong-doing? Surely it is enough to make a man ask why—why—why?" He went on softly to himself: "What can be the reason of Fate's ruling which permits such a thing—the guiltless to spend a life of misery, while the guilty fatten on the results?" He sighed heavily as these thoughts passed through his mind, for as time went on they increased in intensity.

He was gradually sinking into a fitful sleep, when a bell crashed out and brought him to his feet in the darkness. Hurrying footsteps soon followed.

"Someone escaped," he muttered, as he strained his ears, listening. "No; it's not the escape-bell, it's inside."

But the smell of invading smoke told him the truth, and he hastily put on his clothes.

"Might get a chance in the excitement," he thought.

Doors were being rapidly thrown open, and the startled inmates dragged forth, to be huddled with others under the menacing guns of the massed guards.

"Here, get a gait on!" said one, throwing open No. 8072's cell door. "No monkey-tricks, either, or you'll get daylight let into you pretty quick!. The show's on fire!" he added, as No. 8072 started to leave the cell.

As the convict got outside, his eyes were met with a pitiable sight. Men who had been strong mentally and physically when they entered those walls, had lost every shred of strength by their hopeless existence, and stood cowering before the guards. A few others stood indifferent, not caring what happened, while here and there an alert eye betokened the man who intended making a break for freedom in the excitement of the moment.

No. 8072 joined the others, and the remaining cells soon emptied their occupants.

The smoke was getting intense, and the guards shifted uneasily as they waited for the last lot of prisoners to arrive.

That crowd of prisoners in their present mental state could easily get out of hand. One small thing might start a panic, and the guns of the guards would be of little avail if a concerted rush took place.

"Get into line, and march!" called the sergeant, as he detailed five men to lead them. "The first man who moves out of that line will be shot instantly!" he continued. "The fire is bad, but we're going to get through it all right, so don't lose your heads. Remember, now, the first man who disobeys will be dropped in his tracks. Forward!" And the remarkable procession moved along the corridor.

As they came into the main passage they could see the flames ahead of them. The chapel was a raging mass, and it was spreading quickly, its hungry tongues seizing on anything available. The prison was out of date, and the new one should have been put up long before. The present structure had a wood interior, and it was this which the flames were consuming.

When the convicts saw the flames in front of them. and escape seemed hopeless, it created just the spark necessary to start the other flame of panic, and before the guards could prevent them, the prisoners had turned and dashed madly back the way they had come. Shooting was useless, and the guards were greatly outnumbered. They turned and followed the panic-stricken prisoners, whom they found cowering at the other end of the passage. Kicks, curses, and blows were of little avail; the flames were spreading rapidly, and a move must be made soon. It was then that No. 8072 came to the front and took the leadership. The guards, in the strain of the moment, forgot his uniform. They heard only his commanding voice, which they unhesitatingly obeyed. His leadership was unquestioned, and he soon had a semblance of order restored.

Telling the guards off in pairs, he had each pair seize a struggling prisoner. Carrying their burden to the upper gallery and through the passage leading to the corner look-out room, they thrust him forth, and the waiting firemen outside took him down. As each pair of guards deposited his burden, they returned for another and another, until the number of helpless convicts had decreased. Some of them walked the journey, but several, who had refused to go, still remained. The flames were eating their way nearer and nearer to the corridor, and it would soon be impossible to pass up to the gallery.

As the guards felt the hot breath of the fire, they, too, lost their nerve and refused to brave it again.

No. 8072, seizing one of the rifles which had been thrown down by them, levelled it, and threatened to shoot the first guard who refused, forcing them, in this manner, to proceed. Two more trips were made—the last one on the run—and only one man remained. It was madness to brave the fire again. It looked hopeless. There was only one chance in a thousand of getting through and back; but No. 8072 took that chance. Dashing through, he seized the whimpering man and fought his way back, through the licking tongues of flame and smoke, dropping exhausted on the floor of the look-out-room. But he had rescued the man, and to him belonged the credit of the saving of more than seventy lives.

The guards soon recovered their authoritative manner on reaching the ground, and half an hour later No. 8072 and his fellow-convicts were marched, under guard, to temporary quarters.

"You're to come with me!"

It was a prison guard who spoke, in a sharp tone, to No. 8072, who sat in his temporary cell.

The guards had never quite forgiven him for his assumption of authority during the panic, and the convict suffered accordingly.

He rose without question and followed the guard, who conducted him through the building and down the stairs to an office on the ground-floor.

Knocking at a door, the guard stood aside, and No. 8072 entered, to find himself in the presence of the governor of the prison, who sat at a desk facing him.

"You are No. 8072?" he inquired, as the prisoner entered.

"Yes, sir."

"Let me see," continued the governor, consulting a paper before him. "Your name is Torrence?"

"Yes, sir."

"Well, Torrence, it has come to my ears regarding your conduct during the fire at the prison. I investigated the reports, and found them to be true. I made representations on the matter to the State Governor, and, in view of your bravery, and also considering the fact that you were committed to prison on circumstantial evidence, I am pleased to tell you that he has granted you a free pardon, without any conditions attached thereto."

No. 8072 felt everything swimming before him. A pardon! He could hardly believe his ears. It must be a mad joke!

He struggled to speak, but his emotion was too great for him. Finally, he gasped:

"Is it true?"

"Yes, Torrence, it is true," and the governor smiled kindly. "Come, man, pull yourself together and prepare yourself to leave! I have had an outfit purchased for you, and have also to present you with a cheque, with the thanks of the State. It will give you a start in life again, and I trust you will use it well."

Torrence mechanically took the slip of paper which the governor held out, and shaking the hand which was also presented to him, he mumbled his thanks and stumbled from the room, scarcely able to grasp the fact that he was free.

Free! What music that word had in it! How he rolled it over his tongue and dinned it at himself repeatedly. Free—free—free! Free to go back to England! Free to find the man who had sent him to prison, as he thought, for life! Free to hold his head up as other men!

He hastened back to his cell and donned the clothes which had been placed there in his absence. He then returned to the prison office, and thanking the governor in a more collected manner, he passed out; and as the prison door clanged behind him; he went forth into the new life.

Charles Alliston, the Wealthy Mill-Owner - He Tells His

Grandson Jack the Story of His Life - The Butler Overhears.

"DID you ring, sir?"

"Yes. Has Master Jack finished packing, Harris?"

"I'm not sure, sir; but I'll go and see."

"Tell him, when he has finished, I wish to speak to him."

"Very good, sir!" And the man withdrew.

Mr. Charles Alliston leaned back and stared at the ceiling.

His elbows were supported on the arms of the chair which he occupied, in front of a magnificent mahogany desk, and his fingertips were pressed together. His whole attitude denoted deep thought, and such, indeed, was the case.

The room in which he sat was a luxuriously-furnished library. The walls were lined with shelves, in which reposed hundreds of rare editions, for Charles Alliston was an enthusiastic collector. On the tops of the cases and over the large, open fireplace were many strange curios from all parts of the world and of all ages of man. The carpet was of the kind into which one's feet sank with a delightful sensation, and a couple of valuable rugs were thrown carelessly on it—one before the desk and the other before the fireplace. Several massive mahogany chairs and a few choice engravings completed the furnishings. A log-fire burning in the large fireplace threw a softening light on the dignified outlines of the room.

Charles Alliston was the sole owner of the large steel-works in the village which bore his name. His magnificent home lay about two miles from it, the extensive grounds running to the village limits. He was a man well past middle age, but he often remarked he felt thirty, and, indeed, a look at his stalwart figure, straight as a ramrod, as he walked about his works each day, would have impressed one of the truth of his words. His eyes were of a clear blue, and lit up his face pleasantly when he smiled; but of late years that had been seldom. His scanty hair was white, and a pointed white beard and moustache completed the dignified and pleasant impression that one received of him. As he sat at his desk that chill late summer's day, he seemed to harmonise completely with the solid and impressive lines of the room.

He sighed deeply, and his hands parted. One mechanically lifting a silver cigar-case, and the other feeling unconsciously for a match. Lighting a cigar, whose delicate aroma showed an intelligent desire for good tobacco and the means to gratify it, he rose and began pacing slowly up and down the room, his feet making no sound as they sank into the thick carpet. His eyes held a look of brooding sadness, and an occasional involuntary sigh escaped him.

As a knock came at the door, he halted at the desk. The heavy, dark curtains covering it parted, and a boy entered. He was tall, and good to look upon, and his eyes were of the same deep blue as those of the man at the desk. His features showed a great likeness to those of the man, and his figure gave promise of developing into a similar stalwart straightness. It was obvious a close blood relationship existed between them, and the boy's words as he entered proved it to be so.

"Harris tells me you wish to speak with me, grandfather."

"Yes, Jack, I do," replied the man, his eyes softening as he looked at the boy. "Draw up a chair, my boy," he added, resuming his own.

The boy did as he was told, and waited for the man to begin. A log fell down in the fireplace, and the mounting flame threw a flickering light over the man's face, increasing the look of sadness in the eyes.

Neither the man nor the boy heard the suppressed breathing of a stealthy figure, which softly opened the door and stood listening, protected by the heavy curtains. It would have been difficult to recognise in the sinister cunning portrayed on the listening man the usual obsequious expression of Harris.

"Have you finished your packing, Jack?" asked Mr. Alliston as he puffed slowly at his cigar.

"Yes, sir, quite; it is all ready for James to take to the station, and I have nothing to do now before I go."

"Very well, I will ring presently, and send orders to have it taken. You have over an hour yet," he continued, pulling out his watch and glancing at it, "and I wish to have a talk with you."

"All right, grandfather; but I can't think of anything I've done," and he wrinkled his brows in anxious perplexity.

"It is nothing like that, Jack," replied the man, smiling as he spoke, but quickly growing grave again.

"What is it, grandfather? You look worried. I'm sorry, sir. I thought you wanted to speak to me about something I had done," and he looked with affectionate anxiety at the man.

"You will be sixteen next month, Jack, and before you return to school to-day, I have decided to tell you the true facts of your life," replied Mr. Alliston, after a short sigh.

"I knew there was something about my life which you had reserved from me, and I knew it made you sad at times, sir."

"You are right, my boy; and if you will give me your attention I will tell you the facts," and he sighed deeply. "Your father," he continued presently, "was my only son, I brought him up to be my heir and successor in the mills. He was a strong-willed boy, and developed into a stronger-willed man; but we were very happy here. He had been home from school for about a year when his mother died," and the man's eyes grew moist at the memory. "After her death," he went on, "Jack—his name was the same as yours— started remaining away in the evenings. I thought nothing of it until he came to me one day at the office and said he had married the daughter of one of my employees. I flew into a rage, and drove him from me, telling him never to set foot in the door again. He took me at my word, and never did. I heard that he worked at anything he could get for about a year until your birth, which was also the occasion of your mother's death. He placed you in the care of his wife's parents, and left for abroad, saying he would write. Not a word has been received from him since that day, although I have advertised all over the world and in several different languages. One day at the mills, your mother's father, who still worked for me, saved my life. That incident brought us more in touch with each other, and I finally persuaded them to let me take you. You were about four years old at the time, and have been with me ever since."

Mr. Alliston paused to relight his cigar, and the boy's unsteady breathing showed his suppressed emotion.

"I am satisfied," said Mr. Alliston, continuing his narrative, "that something must have prevented your father from writing, because he was not the type of man to break his word. I feel confident he will yet return, and as you are now old enough to realise what it means, I want you to always look for him as I do. I wronged him, but have regretted it for years. That is all, except to tell you that my will leaves you as my heir in case he doesn't turn up. If he does, everything goes to him, excepting an annuity and a junior partnership in the mills, which goes to you. Naturally you will eventually get the rest."

"Oh, thank you, grandfather, but I'm sure, sir, I'd much rather have you than the money or the mills!"

"I know that, my boy," replied Mr. Alliston, rising and placing his hand affectionately on the boy's shoulder; "but one never knows what may happen, although I feel young and hope to live a long time yet." And he started pacing the room again.

"Have you a picture of my father?" asked Jack.

"No, in my anger I destroyed every photograph I had."

"Supposing, sir, he didn't come for a long time, after—after you—" And he hesitated on the words.

"You mean after my death," finished Mr. Alliston. "Well, of course, he will have changed with the years, but you couldn't mistake him. He is big and fair, with blue eyes, and, besides, he has one distinctive mark. When he was a little fellow he was playing with one of my guns, and it went off accidentally, blowing off the little finger of his left hand."

"Well, we'll talk no more about it just now. You had better get ready to leave, and I will go along to the railway-station with you. While you get your things, I will ring for Harris, and send word for the motor to be brought round, and also for James to take your luggage."

"Thanks, sir; I won't be long," replied Jack, and turned to go as his grandfather moved to the bell.

The impassive Harris who appeared to answer Mr. Alliston's summons, wore a very different expression on his face than he had a few moments previously when he had listened behind the curtains.

A little later, Jack and Mr. Alliston were motoring into the village, and, catching the up-train, Jack returned to Crowestoft School.

Mr. William Saunders, alias Jim Ford, alias

Jim Carson, Plans a Coup - He Takes a Journey.

MR. WILLIAM SAUNDERS was evidently in a good humour if the chuckles which he emitted at intervals were any indication of his state of mind.

He was reading a letter, and the contents were undoubtedly of a pleasing nature.

He was sitting in a dilapidated armchair in a room furnished in a most frugal manner. The one begrimed window which it contained looked out on a squalid courtyard from which came a medley of noises. They were caused by a number of dirty children amusing themselves by the entertaining occupation of tormenting a mangy yellow cur.

Their game was interrupted at frequent intervals by a general free fight, and the profane interference of a couple of slatternly women when the fight waxed too hot.

Mr. Saunders seemed oblivious to the pandemonium, for he leaned back in his chair, and his audible remarks bore no reference to the racket below.

"I guess it's about time to make a move," he said, "a few more weeks to let this thing lose its new look"—and he held up a bandaged left hand and glanced at it—"and then I'll start things going. If I hadn't gone broke on that rubber deal, I could have made a different plan. Harris and James are getting impatient, too, so I think I had better run down to Alliston and see what this good news is which Harris says he's got."

He was a big man, and as he rose to his feet and paced the room he walked with the swing of a mountaineer. He was not unpleasing in appearance, but the keen observer saw, that his eyes were set a bit too close together. Where he came from no one knew. He had no friends, and his landlady was practically the only person he spoke to. Certainly, no one would realise that the man pacing the room was the same man who, as James Ford, had swept meteor-like across the financial sky of the City a few years previously. James Ford had come from America, and had speculated heavily on the Exchange, making and losing large fortunes. He had eventually developed into one of the biggest operators' on the "Street," and when rubber was booming had sunk his entire fortune. The market went against him, and he dropped everything. He had disappeared as suddenly as he had come, and no one knew where he had gone. Reappearing quietly as William Saunders, he had nursed his remaining funds carefully, and, enlisting the services of two clever rascals, he started to carry out a plan which he had formed many years previously.

He turned and entered the adjoining room, from which he presently reappeared with a coat and cap on. Putting the letter which he had been reading in his pocket, he went out, closing the door and locking it carefully after him.

He threaded his way through a filthy littered alley, and catching a 'bus to Waterloo, climbed to the top and lit a cigarette. He was not dressed shabbily, but his clothes struck the observer as those of a man who had come down in the world, and still retained some of his belongings. That impression was just what he desired to create. As he smoked his cigarette and glanced casually at the passing traffic, his fellow-passengers would doubtless have been horrified had they known the tenor of his thoughts, and he laughed to himself as that reflection crossed his mind.

On his arrival at Waterloo he booked a first-class return to Alliston, and secured a carriage to himself. When the train arrived at Alliston, a tall man, with black moustache and beard, stepped from the carriage into which a smooth-shaven man had entered at Waterloo. He took the road leading away from the village, and swung along at a smart pace in the direction of Alliston Hall. As he approached the house he turned from the road, and, climbing the wall which separated the grounds from it, he made his way, as though familiar with the surroundings, in a circuitous manner through the trees, and came out near the stables. Dusk had already fallen, and he stepped confidently to the stable entrance. He gave a low whistle as he entered, and a door opposite opened. He moved over to it, and addressed the man who confronted him.

"Well, James, how goes it?" he asked coolly, closing the door and seating himself on a box.

The man who had opened the door had been standing silently, waiting for him to speak. He was a surly-looking fellow, and his voice, when he answered, showed him to be in a bad temper.

"'Ow goes it? A nice question to arsk. You 'ires me to go in on a job, an' then leave me down 'ere lookin' arter a lot o' blessed 'orses!"

"Steady, James, steady; you'll be losing that charming temper of yours. Now, keep cool, and tell me what is the trouble."

"Trouble? The trouble is hi want's ter know when you intend ter make a move. I'm sick of it, I am!"

"You go and tell Harris I am here, and to slip out for a few moments," cut in Saunders icily, "and then I'll talk to you."

The man sullenly went to do as he was bid, muttering angrily as he went.

He returned a few moments later, and they sat in silence, until the door was pushed open and Harris entered.

"Well, Harris, I got your letter and came right down," remarked Saunders as he entered.

"Yes, I've got good news. It gives us all the facts we needed, but makes a complication—to my mind."

"Complication! How do you mean?"

And the "faithful" Harris proceeded to repeat the conversation he had overheard the day previously.

"His telling the boy makes it all the better," remarked Saunders, when the tale was finished.

"I don't think so," replied Harris. "Identification marks, when not genuine, are always dangerous."

"Nonsense! I saw his often enough to know just what it looked like, and I had mine taken off in exactly the same manner. It helps things a lot. The boy will look for that the first thing when the long-lost father turns up, and it will create confidence immediately, especially as I know now, from what you overheard, just how it was done." And he chuckled.

"I wrote out the whole conversation, so you could read it over," said Harris, passing him an envelope.

"Wot I want ter know, is 'ow long this 'ere foolin's goin' ter keep on before we starts?" growled James, who up to now had remained silent.

"Just as long as I decide it will," answered Saunders. "Your part is to obey orders, and not interfere with my business."

"Yer can't treat me like that," sullenly answered James. "We be all in on this, an' it ain't no tea-party game, either."

"If you try any threats, you will discover pretty quick how I can treat you!" snapped Saunders.

"How long before you think you will make a move?" asked Harris, interrupting the wrangle; while James subsided, muttering.

"About two months, perhaps less. I want the recent appearance of this operation to disappear, and I am applying some stuff to help it along. It may be only a month. At any rate, you fellows keep ready for the word, and I will let you know. Don't mess up your parts, and keep cool, no matter what happens. I won't risk coming down here until I come for business, so don't forget. If anything turns up in the meantime, Harris, write me to the same address. I'll have to make a move soon," he added, rising to leave, "as funds are getting jolly low."

And the conference of these unpleasant scoundrels broke up.

Saunders returned by the path he had come, and, catching the evening train to London, stepped out at Waterloo the smooth-shaven man he had been when he had started.

The Murder of Charles Alliston - The Plan to

Outwit the Police - Saunders Escapes to America.

SOME six weeks later a man descended from the night train at Alliston. Leaving the village, he struck off toward the Hall, and climbed the wall as he had on his previous visit. Circuiting through the trees, he arrived at the stables, and a soft whistle gained him admittance.

"Is it you, James?" whispered the new-comer in the darkness.

"Yes," came an answering whisper.

"Did Harris get my letter?"

"Yes; everything is ready," came the voice in reply.

"Tip him off, then, that I am here, and tell him to smuggle me in past the maids when he can."

"All right." And a shuffling sound indicated the movement of the invisible person.

Saunders—for it was he—felt around until his hand felt a box, and, seating himself, he sat motionless until he heard returning footsteps.

"Harris says you'll 'ave to wait 'ere until the maids go ter bed," whispered James as he entered.

"All right. Don't talk; it's dangerous." And again silence reigned.

More than an hour passed before the watchers heard footsteps and a whispered curse as their owner stumbled in the dark.

"Is that you, Harris?" whispered Saunders, as a dark figure appeared in the doorway.

"Yes," came the answer. "Come along."

"All right. Be sure and have everything ready, so I can get the motor out quickly," Saunders added, turning to James. "And don't forget to obliterate any footprints I may have made behind the stable."

"I'll attend to it all right," growled the surly James. And Saunders departed silently in Harris's wake.

Lifting the latch of the side-door noiselessly, they stole silently through a long passage and emerged into the main hall.

"He's in the library now, having a peg," whispered Harris. "Come into the drawing-room and do your changing."

"All right; go ahead." And Saunders followed as Harris opened a door on the opposite side of the Hall, and closed it silently after them.

"Where are the shoes?" whispered Saunders.

"I put them under a sofa. Wait here until I get them." And Harris crept on his hands and knees across the room, returning presently with a parcel.

"Are you going to put them on now?" he asked as he returned.

"No; you keep them here ready. On second thoughts, you'd better come out in the hall. The old bird might put up a fight, and if you hear me whistle you will know I need help. Come at once if you do, for we can't waste any time, and there mustn't be any signs of a struggle in the room."

"Very well, I'll be on hand."

"Now, let me get everything clear," whispered Saunders. "You say when I open the door there are heavy curtains inside."

"Yes; and I oiled the hinges to-day."

"Good! Then on the left as I enter the room is a fireplace?"

"Yes."

"And you say he is sitting before it, reading?"

"Yes."

"Is he on the left or the right of it?"

"On the left. He is in one of the big chairs, and as you enter his back will be towards you, and the high back of the chair will also hide you."

"All right; then I'll get along. Don't hesitate to come at once if you hear me whistle."

A barely perceptible noise, and the following disappearance of the streak of light which shone from under the library door told the listening Harris that Saunders had accomplished his purpose.

He entered the room nervously, and peered through the gloom.

"Hurry up!" came Saunders's voice, in a whisper; and Harris, glancing fiercely over his shoulder, moved across and handed Saunders the shoes he had brought.

Silence reigned as the murderer took off his own and put the others on, and a moment later, pushing up the window, he slid out and disappeared across the lawn. He kept on until he came to a gravel path, where he turned and walked back to the library, following the same course.

"That will puzzle some of their smart men," he chuckled, as he climbed through the window and sat down to remove the shoes he had just utilised. "Be sure and clean those well in the morning, and put them back where you got them," he added, passing them to Harris. "And for Heaven's sake see there is no mud around the floor!"

"I'll clean up thoroughly after you go," said Harris, passing him the shoes he had just removed from the dead man's feet.

Saunders put on the fresh pair, and, tying his own—which had been lying on the floor all this time—around his waist by the laces, he again rose and slipped out of the window.

"Pass out the body!" he whispered back to Harris, and Harris carefully lifted it from the chair, dragged it over to the window, and heaved it on to Saunders's waiting shoulders. "Don't forget what I said," he cautioned Harris, as he was leaving, "and don't make a move of any kind until you hear from me. Remember, it is a big stake, and it pays to go slow and not make any mistakes. Keep your eye on James, and don't let him do anything foolish. I'm sorry we let him in on it, but we've got to put up with him now. Good-night!"

"Good-night! I'll be careful," replied Harris, leaving the window open, and starting to clean up the room.

Saunders was carrying a heavy load, and, big man though he was, he staggered under the weight. He went in the direction he had taken on the previous trip, and, reaching the edge of the gravelled walk, deposited his burden on the grass beside it. He sat down and removed the shoes he was wearing. He put them on the dead man and carefully laced them up. Untying his own from around his waist, he put them on. He then lifted himself to his feet, taking care that his own shoes rested on the gravel.

He followed the gravelled path around until he came to the garage.

"Are you here, James?" he whispered.

"Yes," came the answer.

"Is everything ready?"

"Yes. Did things go all right?"

"Splendid; not a hitch. Have you fixed the door so it looks smashed?"

"Yes; I broke the lock and split the wood around it as well."

"Good! You'd better duck now, and I'll be going. Don't lose your head, James, and be patient; the reward will well repay you."

"Oh, I'll be patient! Only I do likes action, an' I do 'ates 'orses."

"It won't be for long. Now go! I want to get away."

And James disappeared in the dark.

Saunders started the engine, and, jumping in, drove away in the night. The murmur of the almost noiseless engine sounded like fifty engines in his tense condition.

Mr. Saunders was a very clever criminal, probably one of the cleverest who had ever "honoured" England, but he made four mistakes that night.

Breakfast at Lord Raymonde's - They Hear the News -

Sexton Blake Investigates.

"THERE have been hundreds of criminals who were never caught or were never even suspected. I claim that a really clever, educated man who keeps ahead of the times can commit a crime and make his retreat without leaving a trace."

The speaker was Sir Walter Hall, and he was addressing a group of men who were enjoying an early breakfast before leaving for the shoot, Lord Raymonde being the host.

There were half a dozen of them—Lord Raymonde, the host; Dr. Thornton, the famous nerve specialist; Colonel Tucker, the well known explorer; his son, who was in the Guards; Sir Walter Hall, sportsman and J.P.; and Sexton Blake, the famous detective.

The conversation had turned on crime and the criminal, started by young Tucker, probably in order to hear Sexton Blake's opinion.

"What is your opinion, Blake?" asked the host, laughing. "Do you agree with Sir Walter, or will your ideas put him to rout?"

Blake smiled, and said:

"I don't know that I ought to join in this discussion; but although it is true that many crimes go unpunished and their perpetrators unsuspected, I hold that no criminal is clever enough to commit a crime from its inception to its completion without a single mistake, and that a specialist in crime, given a fair opportunity, can discover that mistake and eventually find the criminal."

"Of course I know, Mr. Blake, you have never lost a case," replied Sir Walter. "But look at the hundreds of cases that go undiscovered by the best men at Scotland Yard."

"I know, Sir Walter," answered Blake, smiling modestly at the first part of Sir Walter's remark; "but you will find, as scientific methods are adopted more and more, that the percentage of captured criminals will increase. The science of crime is the most embracing science in the world. It includes a thorough knowledge of every other science, language, and country known, and the man who follows that profession to-day must keep abreast of the times, for, unfortunately, the criminal of to-day is an educated, clever man, and his methods are almost in advance of science. The specialist must therefore be even in advance of the criminal, and follow the psychology of his mind." And Blake leaned back and sipped his coffee.

"I agree with Mr. Blake," joined in young Tucker. "By Jove, I'd like to see you work on a case!" he added enthusiastically.

"I'd be glad to have you any time," laughed Blake.

"You may be right in your contention," continued Sir Walter stubbornly, "but I can't believe there is no crime that can't be unravelled. I'd like to wager on it," he added.

"I'm afraid you'd lose your money if you wagered it with Mr. Blake," joined in Dr. Thornton and Colonel Tucker almost simultaneously.

A general laugh went round the table at their remark, for both of them were rare speakers, and had been apparently engrossed with their own thoughts.

At that part of the conversation the door opened, and the butler entered. Requesting a word with his master, he bent down and whispered in the latter's ear, while Lord Raymonde's brows went up with astonishment. Nodding and dismissing the man, he turned to his guests.

"By Jove, you fellows, what do you think of this on top of our conversation? Jackson tells me that a neighbour of mine, Charles Alliston, the wealthy mill-owner, was murdered in his grounds last night."

A chorus of ejaculations greeted the remark.

"Do you know any details?" they asked.

"No; just the bare statement. I suppose you will look into it, Blake?" he added, addressing the detective.

"I wouldn't mind. But, of course, I suppose the inspector from the Yard will prefer me to wait until he gets there. However, it might be worth while going over, and I think, if you will excuse me from shooting this morning, I will do so. It might prove a mystery which can't be unraveled," he laughed, turning to Sir Walter.

"By George, I'd like to go with you! May I, Mr. Blake?" asked young Tucker.

"With pleasure. I'll get the car, and we'll go over right away. By the way, Lord Raymonde, how far is it?"

"About eight miles. I'll send one of the grooms to show you the way."

"Thanks! That will be splendid," answered Blake.

There was a general rising from the table, all discussing the news they had heard, excepting the great detective, who knit his brows in deep thought.

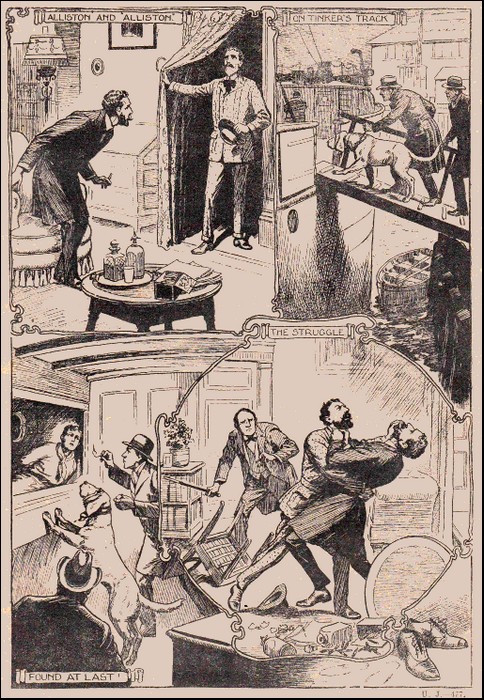

Blake and his companion were soon on their way, and as the detective had never been over the road before he took a photograph of the topography of the passing country-side the while he carried on a desultory conversation with Tucker. As they arrived at the gates of Alliston Hall he brought the car to a stop. Leaving it in charge of the groom, he and Tucker proceeded on foot to the house.

The door was opened by the butler, who seemed much affected by his master's death.

As he ushered them into the hall, he said, addressing Blake, who had passed him his card:

"I don't know that I ought to admit you to the library, sir, until Inspector Thomas arrives. He might not like it." And the admirable Harris radiated sorrowful regret.

"It makes no difference," answered Blake. "By the way, what is your name?" he added.

"Harris, sir."

"I see. Well, Harris, I don't suppose you will object it I look around outside?"

"Oh, no, sir! I will show you round myself."

"I won't take you away from your duties, Harris. My companion, Mr. Tucker, will accompany me.

"Very good, sir," the man replied, as Blake moved toward the door.

"Oblige me by strolling around in front, please, Tucker! I won't be long, and will explain my reason later. If Harris appears, engage him in conversation, and hold him some way until I return," murmured Blake hurriedly, as he strolled casually around the corner of the house.

"Right!" replied Tucker, catching his meaning, and pleased at his inclusion at the detective's actions. "I'll hold him!"

Blake strolled slowly on until he saw the open window. Walking quickly along the side of the house, he looked in, and, seeing the body stretched on a couch, knew it was the room Harris had refused to allow them to enter. Looking at the ground, he perceived the footprints leading from the window, and followed them until he came to the gravelled walk. Three times the detective paused, and took his mould from his pocket, and on reaching the walk he used it a fourth time.

"Inspector Thomas would be wild if he knew." murmured Blake, as he followed the gravelled walk around to the front.

Tucker was engaged in an animated conversation with Harris, and winked at Blake as he came up.

"Harris was looking for you, Mr. Blake, but I told him you had just strolled around the grounds. He wanted to go and assist you, but I told him you could find your way."

"Oh, yes!" answered Blake. "It was very good of you, Harris"—turning to the man—but I saw all I desired. Has Mr. Alliston any children or relatives?" he continued.

"One grandson, sir—Master Jack. I wired for him, and he will arrive at ten-thirty. Inspector Thomas also comes by that train, I think."

"Ah, very well, Harris! Mr. Tucker and I will sit here, and wait until Master Jack arrives." He seated himself on a garden bench in front, and Tucker joined him.

"Did you find anything of interest?" inquired the latter.

"I can't tell you. I want to hear the whole story, and I didn't care to ask the details until the inspector arrives. We'll wait until then."

"Right! I'm immensely interested!" replied Tucker, as he lit a cigarette.

Meanwhile, Harris had re-entered the house, and it is to be regretted Blake couldn't hear his remarks.

"I don't care for all Scotland Yard, but that man means trouble. He finds facts from nothing—curse him I'll stop him, If I have to kill him!"

And he shook his fist in the direction of the unconscious detective.

Arrival of Inspector Thomas and Jack - Inspector Forms a Theory -

So Does Blake - Blake Takes Case for Jack.

BLAKE and Tucker smoked on the terrace for half an hour, until they perceived a trap coming up the drive.

"Here comes Inspector Thomas now!" remarked Blake, rising. "Let us go and meet him."

"They strolled over to the trap as it stopped, and Inspector Thomas, accompanied by a tall boy, descended.

"I didn't expect to see you here, Blake," remarked the inspector, in a surprised tone, as he alighted.

"It is purely an accident," replied Blake. "I am staying for a few days, shooting with Lord Raymonde, whose place is near, and, hearing of the matter, I ran over.

"What do you make of it?" asked the inspector sharply.

"Oh, I have awaited your arrival! I didn't care to do anything until you came. In fact, I haven't even heard the story from the butler yet."

"Ah," remarked the inspector, and his manner thawed a little. "I'm glad you waited! By the way, this is Master Jack Alliston, who is a grandson of Mr. Alliston." And the boy, whose face indicated great grief, shook hands with Blake. "We came down on the same train," added the Inspector.

Blake introduced Tucker, and the party moved into the house, where Harris received them.

"You'd better not come along," said the inspector, addressing Jack. "I'd wait, if I were you, until after the examination."

"Oh, no; I must come!" replied the boy appealingly. "Grandfather and I—"

But he choked on the words, and turned away.

"Come along!" broke in Blake. "It won't be any worse than sitting alone in your room."

"Now, Harris," said Inspector Thomas pompously, "tell me all you know about this unfortunate affair before we go the library!"

"Well, sir," replied Harris, "I went to call the master this morning, and found his bed hadn't been slept in. I was a bit worried at the discovery, and came down at once to the library. When I opened the door I noticed the window was up, and the room empty. Just as I was going over to the window I saw James, the coachman, sir, coming across the lawn in a hurry. He was very agitated, and I asked him what was the matter. He said he had found the master's body under the trees, and that there had been murder. I left the room, and went around to where the body lay. It was as he said, sir, for there was a large wound in the shoulder. We lifted it up, and carried it into the library. James said, sir, that the garage had been broken into, and the motor taken. I then telegraphed for you, sir."

"It seems hardly probable that the garage could be broken open, and the motor taken, without anyone hearing the noise," interrupted the inspector. "But, however, we will go into the library, and have a look round. In the meantime, send for James!"

"Very well, sir!"

And Harris went to call the coachman, while the party moved into the library.

Jack gave a cry as he saw the body, and fell on his knees beside it, but Blake put his hand on the boy's shoulder, and said:

"Steady, my boy; keep up your courage. I know it is hard, but you will need all your strength during the next few days."

The boy's eyes hardened as he dragged himself to his feet.

"I'll find his murderer, if it takes me all my life; and when I do—"

And he seemed to grow older as he stood erect, and clenched his hands.

They went over to the body. and the inspector examined it first before permitting Blake to do so.

Inspector Thomas was a pompous man. and did not entertain very warm feelings for Blake, since the latter had beaten him on several cases. His manner showed he would have preferred the detective's absence, but Blake ignored it. His all-seeing eyes, however, darted around the room, taking in everything.

Harris returned with James. and they stood inside the door, awaiting the inspector's wishes.

"Has anything been disturbed?" he asked.

"No, sir," replied Harris. "James and I carried the body in, and I wouldn't allow anyone near the room."

"What time did you last see the deceased last night?"

"He rang about ten, sir, and I brought him a whisky-and-soda. He told me I could go then. and, after locking up, I retired."

"Where was he sitting?"

"In that chair on the left of the fireplace, sir."

"The window was closed, of course, when you brought him his drink?"

"Oh, yes, sir!"

"There must be some footprints outside with this muddy weather?" remarked the inspector, moving to the window.

"Yes, there are, sir; and I kept everybody away from them." answered Harris.

And Sexton Blake glanced sharply at the man as he heard him.

"Ah. that was wise! What do you make of this," Mr. Blake?" asked the inspector, after examining the footprints.

"I haven't formed any theory yet," answered Blake.

"Looks pretty clear to me," said the inspector. "We'll just follow them out to where the body was found. Here's a line of footprints approaching the window," he continued, as they walked along, "and the same prints going back again. Here is a single line leaving the window, and not returning. Mr. Alliston was found at the end of this line, and, as I expected"—measuring the prints and comparing them with the shoes on the dead man's feet—"they were made by the deceased. Very clear, I think. Someone approached the window, rapped, and the deceased opened it. The caller evidently said something which induced Mr. Alliston to accompany him, and the man murdered him under the trees. Let us go to the garage, and have a look there," he continued.

And the others followed him.

As they returned, and arrived the second time at the spot where the body had been picked up, the inspector made a closer examination of the ground. He saw a mark which interested him, and approached to examine it, but Harris accidentally trod on it with his heel, and in the soft mud it was obliterated.

Harris was again favoured with a scrutinising look from Blake, but in the profusion of his apologies to the inspector he did not perceive it.

Sexton Blake already had a mould of that mark which had interested the inspector in his pocket.

After the inspector had jotted down some notes, the party returned to the library.

"I'll send a constable up here, and I want you to leave everything untouched," the inspector said, addressing Harris. "I'll send another man along, and you can take the trap and go with him in search of the motor," he added to James. "I don't think it will be far away—probably only a blind. It looks like a clear case," he continued, turning to Blake. "Doubtless one of the men who worked in the mills, who had a grievance. I'll investigate that point," he added. as he turned and strutted to the door.

"I think we had better get along, too," said Blake, turning to Tucker. "Good-bye!" he continued, holding out his hand to Jack. "Keep up your courage!"

"Can I speak to you privately, Mr. Blake, before you go?" interrupted the boy.

"Yes; certainly! Come out to the car, and we can talk undisturbed."

Excusing himself to Tucker, he led the way outside, followed by Harris' angry eyes.

"Now, what is it?" he asked, as they leaned over the car.

"Won't you take this case, and help me find grandfather's murderer, Mr. Blake?" said the boy. "The police are so slow, and I know you will find him if you take it on."

"I am pretty busy at present," replied Blake. "and, although the case presents some very interesting features, I am afraid—"

"Oh, don't say you can't!" broke in the boy. "Please take it on!"

And he grasped Blake's arm in his earnestness.

"All right, my boy, I will. I'll go back to town to-day and start on it. Are you returning to school?"

"Yes; I will go back and finish the term. There are only a few more weeks, and I know grandfather would wish it."

"What school is it?"

"Crowestoft."

"Ah, yes; I know it! Very well, I will communicate with you there. By the way, have you no other relatives?" asked Blake.

"Well, I hardly know whether my father is alive or not. Grandfather only told me about him the day I returned to school for this term."

And he proceeded to tell Blake what Mr. Alliston had told him.

"Have you a photograph of him?" asked Blake.

"No, sir. Grandfather destroyed them all when he was angry."

"How will you recognise him if he turns up? Will the family lawyers know him?"

"No; they wouldn't. Mr. Burton would have, but since he died grandfather has had his business done by a London firm, and that is since my father went away. But grandfather described him to me. He is big and fair, and, besides, he has one distinguishing mark—the little finger on the left hand is missing. Grandfather said he lost it by the accidental explosion of a gun."

"Ah!" said Blake. "I see! Well, have patience, my boy, and keep up your courage."

"I will, sir, and thank you so much for helping me."

"Oh, that's all right!" smiled Blake, and beckoned to Tucker, who stood waiting.

"Well, it seems a pretty clear case, as the inspector says," remarked the latter, as they drove away.

"It would seem so on the face of it," smiled Blake, but the great detective's remarks to himself as he entered his room to pack his bags were very different.

"Which goes to prove my statement," he muttered, "that no criminal, no matter how clever, can execute a crime from its inception to its completion without a single mistake; and the unknown man in this case has made four."

Blake Follows Up a Clue - Baffled - Light on the Matter -

Tinker and Pedro take up the Trail.

"I'M deucedly sorry you are breaking your trip short, Blake, but I suppose if you must, you must. However, we will be here for some time yet, so if you get a chance, run down again." And as he spoke, Lord Raymonde held out his hand.

"Thanks!" said Blake, taking it. "I've enjoyed myself, but matters have arisen which make it imperative that I should run up to London; but you may see me again sooner than you think," he laughed, climbing into the big car, and taking the wheel. "So I only say au revoir."

"That's right, come whenever you can. We'll be delighted," answered his host, as Blake started away after waving his hand to the rest of the assembled guests who stood on the steps.

They would have been surprised if they had seen the big car turning in entirely the opposite direction from London as it gained the road; and go spinning at a smart pace towards Alliston Hall. It kept steadily on, passing it at high speed, and the detective did not slacken his pace until he had covered a score of miles. It was early in the afternoon, and he desired to test a theory before driving on to London.

He pulled up at each village through which he passed, and made an inquiry, but did not gain the information he wanted until he had covered a good eighty miles. As he descended a steep hill with a stone bridge at the bottom, he saw a number of farmers congregated together, examining some object in the bed of the stream. Looking down, he saw a wrecked motor-car, and brought his own to a standstill.

"Looks like a! bad smash," he remarked to the crowd who stood looking on.

"That it is, sir," said one. "Jones here, saw it as he was driving over the bridge. It was half in the water, and half out; and almost hidden by the tree."

"Have you found the driver?" asked Blake.

"No, sir; not a sign."

"You won't, either," said Blake drily; and they looked at him in astonishment. "You'd better turn it over to the police."

"We've sent for the constable already," replied the man.

"That's right; he will doubtless soon find the owner. How far is the railway-station from here?" added the detective.

"About a mile further on," replied the man.

"Thanks!" And Blake drove on.

The detective drew a blank. He spent several hours interviewing every stationmaster within the greatest possible radius which his theory embraced, but the answers had all been the same.

"No, they hadn't sold a ticket that morning to a man, nor, in fact, to anyone. Three had been sold by one man in the afternoon, but they were returns, and were to local residents whom he knew well. No, no goods train had stopped—one had run through, but it was a non-stop train. What time? About eleven the previous night."

And Blake knew his man couldn't have caught it so early. It would be one o'clock, at least, before he would be able to get that far from Alliston.

The great detective was plainly puzzled as he turned the car and headed for London, and sat absorbed in thought as he drove the big machine on its two-hour run.

"Why, of course," he muttered, as he turned into Baker Street, "why didn't I think of that? Let me see, Liverpool is the nearest. I will send Tinker to look that up."

"Did you have a good time, guv'nor?" asked Tinker, stretching his arms and yawning as the noise of Blake's entrance awoke him from the enjoyment of a sleep in a big chair before the fire.

"Fine! Anything new?"

"No, not a thing, guv'nor. I say, you are muddy!"

"Yes, I was driving fast," laughed Blake. "Stir yourself, my boy, I've got work for you to do,"

"Good! I just wanted something."

"Well, you'll get it this time, if I'm not mistaken."

"Is it a new case, guv'nor?"

"Yes." And Blake explained the facts to him. "I want you to go to Farnham and start from there," said the detective, as he finished his explanation. "It didn't occur to me this afternoon while I was there, but I feel sure the fugitive would have another car waiting for him. Pick up the trail, and follow it. I think you will find it will lead to a seaport, probably Liverpool; but make sure. Find out all you can, and wire me. I'll look up some other matters here, and you should be back by to-morrow night. Don't waste a moment, as time is valuable."

"Right, guv'nor!" replied Tinker, jumping to his feet.

"Will I take Pedro?" he asked, as the great beast entered and greeted Blake.

"Yes, if you wish. He might be useful in picking up the trail. You can get a train in an hour, so you'll have to hurry."

"Right!" And Tinker hastened away to pack a bag.

Tinker found the wrecked car the next morning, as Blake had said; and, hiring another from the local garage, he started to pick up the trail. On reaching Blakely, he stopped at the inn and made inquiries. He discovered that the boots boy had heard a motor going through the previous morning as he got up.

"What time was it?"

"About four o'clock."

And Tinker hastened on.

Following the trail on the information gained, Tinker found it headed steadily in the direction of Liverpool. As he arrived there, he paid the driver, and betook himself first to the docks. He discovered that the Caronia had sailed at ten the previous morning for New York, and, going to her dock, he finally located a man still on duty who was there when she sailed.

"Were you near the gangway when the Caronia left?" asked Tinker, slipping the man a half-sovereign.

"Yes, that I was, young sir."

"Were there any late arrivals? Did you see any passengers coming up just before she left?"

"Come to think on it now, I did," replied the man, spitting. "A motor drove up, and a big man got out. He didn't do no more than catch it, either," he added. "Was he a friend of yours?"

"Yes; I wanted very much to see him before he left," replied Tinker truthfully; "but I see I have missed him."

And, thanking the man, he hastened away to a telegraph-office, the faithful Pedro trotting beside him.

Tinker sent a long telegram to Blake. He gave his address at an hotel, and proceeded there to have lunch and await an answer. He had just finished, and was amusing himself by watching the people around him, when the waiter handed him the expected message. Tearing it open, he read:

"Return at once."

Tinker Leaves for New York - The Passenger from the Caronia -

Tinker on the Trail.

"I WANT you to get ready at once to leave for New York," said Blake, as Tinker finished his report.

"Oh, that will be splendid!" said the boy eagerly. "Does Pedro go, too?"

"I'm afraid not," smiled Blake. "I looked up the sailings to-day while you were gone," he continued, "and find the Caronia is a seven-day boat. The Mauretania leaves in the morning, and docks about four hours before the Caronia, so you will be there in time to watch the passengers go ashore. I will give you a letter to Detective Carter, of New York, and he will arrange for you to get a position at the gangway as they descend. I have procured a large plan of the city, and am also giving you a letter to the manager of the Hotel Belmont. It is a magnificent hotel, but as I want you to adopt the role of a young gentleman of leisure travelling for amusement, it will be necessary for you to stay at a place of that description. When you take your place at the gangway as the passengers descend, stand so you will be on their left, and look at the left hands of everyone as they come down. If you see one with the little finger of his left hand missing, follow him, and see where he goes, keeping me advised by cable, and don't lose sight of him. Detective Carter will let you have a couple of men to assist you.

"I will see him if he gets off, and if I do, I won't lose sight of him," replied Tinker.

"Well, keep your eyes open, and don't get into trouble. New York is a bad place in parts, and you may find your man will patronise those parts. Keep your revolver handy, and use it if you are attacked. Detective Carter will give you an authority which will be of assistance to you. Now get some sleep, and be fresh for the trip."

Tinker had often been in New York, but the promise of a race against time with the Caronia filled him with a pleasurable excitement. Blake had given him his final instructions, and had taken his departure, and Tinker, proud of the responsibility, vowed to be worthy of the trust as the great steamer left the dock.

He enjoyed every minute of the trip, and his frank, sunny ways made him a general favourite on board. As they sailed up the harbour, past the towering Statue of Liberty which stands at the front gate of the New World, Tinker indulged his interest in everything he saw, for they had passed the Caronia in the night, and he knew he would reach her dock before she landed her passengers.

He hastened ashore, getting through the Customs as quickly as possible, and, taking a taxi, proceeded at once to Mulberry Street.

Detective Carter was the most famous detective in America, and Tinker was anxious to see the man who was only second to Sexton Blake. He found Carter in his office, and presented his letter. The detective read it, and looked at Tinker with a searching gaze.

He was a smooth-shaven man, with keen grey eyes, and Tinker thought to himself that he didn't look unlike Sexton Blake.

"You're pretty young to be doing such responsible work, aren't you?" he asked, smiling.

"I know, sir. Mr. Blake has entrusted me with some important things before now, and they were handled to his satisfaction," replied Tinker modestly.

"I don't doubt it, my boy," answered Carter, holding out his hand. "Just let me know what I can do for you. I will be glad to oblige you for Sexton Blake's sake, even though he has beaten me before now. I reckon he is a great detective, and you are indeed fortunate to get your training under him."

"He is, sir!" replied Tinker, his eyes shining with enthusiasm. "He has been awfully good to me. Could you let me have two men?" he continued. "I want to catch the Caronia before she docks, and may need them to shadow a man."

"Certainly; with pleasure. I'll send two of my plainclothes men with you." And, ringing the bell, he gave instructions to the patrolman who entered to send in the men he wanted.

He introduced Tinker to the men, Hill and O'Hara, as they entered, and said:

"You will go with this gentleman, and consider yourselves under his instructions. He represents the famous Sexton Blake, and I want you to show him we can do things here as well as they can do them in London." And he smiled at Tinker, while the men looked at the lad with added respect.

Tinker felt a glow of pride as he saw the power of his benefactor's name even in a foreign land.

"Thank you, Mr. Carter," he said, holding out his hand. "I will get along now to the Belmont and leave my bags. You had better come with me," he said, turning to the men, "and we can go right down to the Caronia's dock from there."

The men saluted Carter and followed Tinker out to the taxi.

As they swung into Broadway, Tinker confessed to himself that he liked what he had so far seen of their methods. Tinker felt he was on his metal, for he knew they would watch every detail of his English methods.