RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

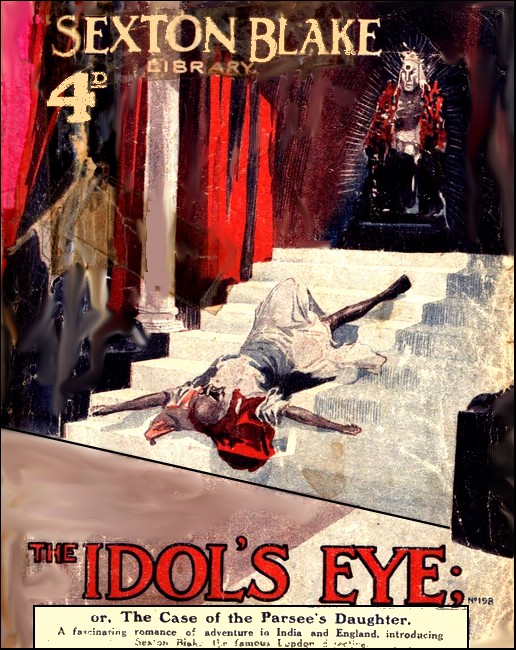

Sexton Blake Library, November 1921, with "The Idol's Eye"

A statue of the goddess Kali.

Alone in the Jungle—The Tiger's Claw—The Parsee's Daughter.

PHEET-EET-EET! Pheet!

The shrill scream of the whistle quivered through the shimmering heat of the jungle. The Central Provinces badly needed the refreshing rains of the monsoon. A glaring sun beat down mercilessly on the scorched profusion of cactus, wisteria, and parasitical undergrowth, making the drooping plumes of the palms hang wilted as from dead, gigantic birds, and drawing from the mangrove swamp a heavy, stagnant odour.

Pheet-eet!

Through an opening between the lofty peepul trees a range of mauve-tinted hills reared against a cloudless sky, and from their naked slopes came the howls of jackals and the chattering laugh of a hyena as he led the hungry pack to the valleys below in search of food. Countless insects droned in the honey-laden, brilliantly-hued flora, and the brushwood rustled occasionally with the passage of hissing cobra, grunting wild boar, or prowling cheetah.

Came the sound of the whistle again, and suddenly the brushwood parted to reveal two lithe, copper-skinned Hindoos as they lashed the densest of the thickets with stout staves.

And from ahead came a coughing roar as a tiger, awakened from its gorged siesta, restlessly paced its lair.

The shrill blast of the whistle had signalled the beaters to stop; and now a white man, clad in serviceable drill, with knee-boots, and a pith helmet tilted over his eyes, made his way towards them.

Tall, bronzed, and lean, with fair hair and steadfast blue eyes, Edward Hartley looked every inch an adventurous, sports-loving Britisher.

The younger son of a baronet, with little prospect of inheriting the family estates in Essex, he had long since tired of the conventional rounds of a man about town, and twelve months before had booked a passage on one of the British-India boats for Bombay. After a tour of the south he was now trekking northwards through the Central Provinces to the big game preserves of the swampy Punjab, accompanied by his two faithful beaters of the Bhil tribe, who worshipped him—next to their numerous and varied gods—above all things on earth.

Sport in the Central Provinces at this period—some twenty years ago—was plentiful, and Hartley, shooting in the Wuddar style (on foot), had met with fair success; then news had come from the elders of a near-by village—at which he had rested—of a mammoth, cattle-killing tiger that had been known to kill a man in pure sport.

Thinking the opportunity too good to be lost, Hartley had wasted no time in getting his beaters on the man-killer's track. After days of patient jungle-craft he now seemed within an ace of success, and the reckless blue eyes sparkled with eagerness as he reached the beaters.

"You have done well," he said, in Hindustani. "Take you the left, Khar, and you, Moulla Rahl, the right. Work carefully round its lair, and when I give you the signal, drive towards the clearing yonder. I will await with my rifle."

The dark, soft eyes of Moulla Rahl looked troubled.

"As the sahib commands," he said, in an uneasy voice. "But I beg of you to use caution, master. This is no mangy tigress worn with nursing, or broken-toothed old male But one of such size"—he pointed to the imprint of an enormous five-clawed 'pug' in a patch of earth—"that even I, sahib, who have beaten the Satpura Hills and preserves of Bengal for the Royal sahibs have never beheld greater than the sabre-tooth that lurks yonder to kill."

"Your words are wise, Rahl, and I will remember," Hartley said; and as the beaters slipped quietly through the jungle, he made his way to the clearing, the joy of battle in his eyes, that smile of pure recklessness on his lips which made those who loved Edward Hartley fear for him.

Dropping to one knee he examined his rifle, and after a brief pause blew his whistle for the drive to commence.

As the raucous shouts of the beaters rang out they were answered by a menacing snarl. Rather than forsake its lair the "king of the Indian jungle" was prepared to battle for its life. Then came a violent crashing of undergrowth and brushwood, a hoarse cry of fear, followed by a scream of agony and terror that died into a whimpering moan.

Hartley, his face pale, leapt to his feet. He knew what that scream meant, and as he ran forward he fired his rifle, hoping to scare the enraged animal from the unfortunate beater. But scarcely had the hills ceased to echo the shot than another scream rang out, this time trailing into an agony-wrung death cry.

Hartley hastily reloaded his rifle and paused for a moment, uncertain of action; then a crash, followed by a menacing growl, sounded to his left and he hastily turned. Before him, with head bowed to the ground, the luminous green eyes burning under the heavy brows, crouched the tiger, silky-coated, full-bellied, and deep-jowled.

The unwinking green eyes never left the man's face. It was the deadly jungle mesmerism that the "sabre-tooth" had practised often on his quarry, and although Hartley was by no means a terrified jungle hare, he stood for a few seconds, held by the oddity of the attack.

Then, with a strained laugh, he jerked the rifle to his shoulder and fired between the devilish eyes.

There was a growl of pain, a quivering of the lithe, sinewy body, and the furry mass, reeking of carrion, sprang. Hartley felt a searing, agonising pain as the cruel claws, dripping with blood of the unfortunate beaters, bit deeply into his flesh, and he toppled backwards beneath the heavy carcass. As he lay beneath, the tiger, game to the last, raised its paw for a finishing blow. But the burning eyes glazed, the paw wagged foolishly; then, with a final, convulsive kick, the animal lay dead.

For a time there was silence, until one by one the startled animals returned to their lay-byes. For hours the white man lay motionless. The hills became wrapped in the opal haze of night and the sinking sun lit up the western sky with flaming gold and crimson. With tropical suddenness the jungle was plunged into darkness, and the Indian night, broken by its minute noises, hung over them, as oppressive as the heat. The bush was very quiet but uncannily alive. The moon climbed slowly into the star-spangled heavens, bathing the grim scene with a soft light, and from the shadows crept a beautiful spotted cheetah.

Sniffing hungrily at the reek of blood, the graceful creature circled cautiously round the still figures; then, lifting its snout, whined out its eerie, cat-like call, which was answered in the distance by its mate.

"Sahib! Sahib!"

There was a crashing of dried brushwood and the cheetah sprang back into the undergrowth with a startled growl as the faithful Moulla Rahl staggered drunkenly into the clearing.

The brown flesh of breast and loin was terribly lacerated, and the tattered dhoti, wrapped about his loins, covered with blood. But with a courage as great as his strength was weak, the gallant Bhil reached his master's side, only to fall face downward beside him.

The cold sweat was already commencing to steal out in great beads on the brown limbs, but in the lion heart of the Hindoo was a love for his master that would not admit defeat. Struggling gamely to his feet he stooped over the white man, and as gently as possible, grasped the torn and bleeding shoulders. With an effort that sent the agony-wrung sweat streaming down his body, he drew Hartley from beneath the crushing weight of the tiger, and when the white man faintly stirred and groaned, Moulla Rahl's dimming eyes lit up with joy.

Unknotting the dhoti from his waist he crawled to a tiny jungle stream and rinsed out the bloodstains in the cool water. When he returned he tore it into strips, bathing and dressing his master's wounds as best he could. Finally, satisfied with his task, he squatted by the white man's side and chanted weirdly to his gods.

The night dragged on; from the mangrove-swamp came a cold white mist, and with the mist came the mosquitoes. Moulla Rahl knew that for white men the fierce little tormentors meant fever and perhaps death.

Picking up a fallen palm leaf, he fanned the buzzing horde from the motionless figure.

As the first flush of dawn coloured the eastern sky Hartley stirred uneasily, and after a wild glance at the stiffening bulk of the tiger, looked at his beater with sane and seeing eyes.

"Good man, Rahl!" He stretched out his hand as he spoke in faint tones, and the lean, brown fingers clasped it timidly. "When the sun rises higher, take the revolver from my belt and fire three shots. The signal may be heard. In any case, it is our only chance. What of poor Khar?"

"Sahib, Khar is dead!"

Though realising the hopelessness of the effort, Hartley made an attempt to get to his feet, but with a groan of pain, sank limply back.

"I am sorry," he muttered. "Sorry—to have led you—into this." He closed his eyes. "Rahl, it was the sabre-tooth's fight, I fear—victory even in death!"

With stoic calm Moulla Rahl squatted by his master's side, fighting against the deadly weakness that was threatening to overpower him. Before the sun rose much higher the gallant beater knew that he would be dead, but with the tenacity of the Bhils—a tribe famous wherever shikar (big-game shooting) is followed—he held on to life.

When an hour had passed he took the Webley & Scott from his master's belt, and, lifting his arm into the air, rapidly fired three shots—the white man's signal of distress known throughout India. The hills, taking up the reports, sent them echoing through the valleys below.

The distress signal was followed only by silence, and, each kick of the revolver sending a spasm of agony through his tortured arms, Rahl fired again after a reasonable pause. Six times in all fired Rahl, then, faintly in the distance, sounded the rolling beat of tom-toms. The signal had been heard.

Rahl's dark eyes flickered with no light of joy, and, seizing the whistle from his master's belt, he blew blast after blast in order to give the rescuers their direction.

When the sound of the tom-toms of the approaching party could be plainly heard, Moulla Rahl, faithful unto death, gave up the life he had clung to for his master's sake; and with one profound salaam to his gods, toppled sideways into the grass and lay still.

The undergrowth parted, and into the clearing trotted a party of low-caste Hindoos, followed at a more leisurely pace by a tall man of dignified appearance, flowing white beard and cream-coloured flesh. On his snow-white head he wore the black, shining helmet of the Parsees—not unlike a bishop's mitre. His legs were wrapped in a silk dhoti of exquisite design and texture; and over his embroidered shirt, fastened with jewelled studs, he wore the long, black surcoat affected by his caste.

Josef Agran, one of the native merchant princes of India, had just completed a tour of the district, bartering for rugs, jewels, and carvings of ancient workmanship, of which most native villages, poor and famine-stricken though they may be, contain a goodly store. With caravan, pack-mules, and servants he had been following the winding, beaten road that ran through the jungle, some two miles to the east of the tragic scene, when, hearing the signal shots of the faithful Rhal, he had read its message of distress.

As his eyes fell upon the still figures, Josef Agran uttered a sharp cry of pity, and running forward, knelt by Hartley's side. After a cursory examination the Parsee turned to his servants, who were gazing from awestricken eyes at the beautiful body of the huge tiger.

"Make a litter of branches quickly, for the white man lives!" he commanded rapidly.

And as the natives set about their task he took from his girdle a gourd of potent Indian spirit.

With gentle hands he lifted the bloodstained head to his knee and put the gourd to the scarred lips. Hartley spluttered convulsively for a moment, then opened his eyes.

"Easy, my friend," Agran bade gently, as the Englishman made an effort to rise. "You are with friends. Do not move. Soon I will have you carried to my caravan that stands in the jungle path, and my madah is well versed in the art of medicine, shall attend you."

With faint words of thanks Hartley looked gratefully into the kindly face of the Parsee. Then be saw the huddled figure of Rahl, and his blue eyes dimmed.

"If any of your bearers are of the true Hindoo caste, please bid them build a funeral pyre and cremate the bodies of my beaters according to the rites of their caste," he said sadly. "It would be their earnest wish could they voice it. I cannot leave their bodies to the beasts of the jungle. They were faithful unto death."

"It shall be done," Agran said gravely, and with a weary sigh of pain Hartley drifted back into unconsciousness.

At length the litter was constructed, and when the funeral pyre of the beaters was well alight, the procession, preceded by two of the bearers, who beat down the undergrowth for them to pass, made its way to the jungle path.

When they reached the caravan an ebony-skinned syce left the team of little switch-tailed kabuli ponies, and, opening the door, assisted the bearers to carry the limp figure to a pile of silk cushions which lay strewn about its luxurious interior.

"Fetch the madah quickly," bade Agran.

And with a respectful salaam the syce trotted off, returning in a few minutes with the madah, a shrivelled old man with a white, flowing beard.

The medicine bag of his calling was strapped across big bony chest, and as he bent over the recumbent figure of Hartley he muttered and nodded with an air of profound wisdom.

"The sahib's illness will be long," he said. "But he will live."

In a quavering voice he ordered the syce to light the kerosene oil-stove, and, filling a brass lotah with water, he carefully removed the coarse linen bandages from the white man's wounds, while he waited for the water to boil. When it was hissing and bubbling in the lotah he took a bunch of dried leaves from his bag and a roll of fine linen bandages. Placing the leaves in the water, he stirred them for some minutes with a bamboo rod. A pungent but not unpleasant odour filled the room.

He tore some of the linen into strips when the infusion had cooled to his satisfaction, and soaked the strips in the herbal brew, wringing them half out, then placed them carefully over Hartley's wounds and bandaged firmly.

Satisfied with his task, he stepped back and addressed his master.

"It is well, sahib," he quavered respectfully. "The white man's wounds, although deep and ragged, are not fatal. They will now heal cleanly. When he is conscious, give him a little food, and then this potion in the phial, for it brings sleep and ease from pain."

Josef Agran nodded, and drew a curtain of chopped and dyed reeds across the divan. Then he dismissed the madah and bade his servants continue the journey.

It was not until dusk had fallen and the caravan was halted beneath the shade of the peepul trees for the night, that Hartley stirred.

The soft-footed Agran was immediately at his side, carrying a gourd of goat's milk.

"Drink this," he said softly, as the blue eyes opened; "then I will have some food prepared for you."

After Hartley had sipped some of the cool, refreshing milk, Agran left the caravan, and when he returned he brought a bowl of boiled goat's flesh. Eating a little, Hartley felt stronger.

"I don't know who you are," he said in a weak voice. "But I'm infernally grateful to you. I met my Waterloo in the beast you saw lying beside me." He shuddered. "What would have happened if you had not found me I don't dare to think. Vultures, cheetahs, and jackals are not timid when they scent a helpless man. But what of you, my friend?"

The Parsee squatted beside him.

"My name is Josef Agran, and I am a dealer in precious stones," he said. "I was on my way home to the village of Kudderal when I heard your signals. It is some days' journey from here. I intend taking you to the home of an Englishman who is commissioner of the district there. His wife will nurse you, and you will get food and attention according to the manner of your race."

"It's thundering good of you," Hartley said gratefully. "But tell me, how is it you speak my lingo so well?"

"I was educated at the college of Madras, after the English fashion," said Agran. "And I deal much with your race at my shop in the Parsee bazaar at Bombay. Speak not of your gratitude, my friend. An Englishman once saved my life, and any service I can do you will help to repay the great debt I owe to your race. But I shall tire you with my chatter. Drink this, and sleep."

He held the phial the madah had left to Hartley's lips, and soon the white man closed his eyes.

When his even breathing told Agran that he slept, he dropped a mosquito-net over him and quietly summoned the punkah-wallah. As the native squatted in the corner and pulled the ropes of the big fan-like punkah, the cool air circled round the caravan, and, stretching himself upon a reed mat, the Parsee went to sleep.

At noon of the third day the jungle grew sparser, and soon they were travelling over an expanse of sun-lit desolation, with several roads straggling in various directions. A little later that evening they reached the village of Kudderal, with its rows of mud-and-wattle huts, intersected here and there by comparatively lordly dak-bungalows.

The hot, roughly-made streets were filled with chattering natives, ramshackle gharries and ox-waggons, and the shouts of fruit sellers and water carriers sounded on every side.

Children, clad in little garments of coloured prints, ran beside them, soliciting alms, to the accompaniment of the jingling bangles which gleamed upon their brown arms and ankles.

Leaving the native quarters behind they mounted an incline, and the better-class houses, painted pink, blue, and yellow, gleamed in the sunlight. Some hours later they drew up before a stately residence of white stone that lay beneath a clump of lofty palm and peepul trees.

The reed curtains covering the arcade that ran along the front of the house were suddenly dashed aside, and a slim, girlish figure ran lightly down the steps.

She wore an underfrock of white, embroidered satin, covered by a silk saree of beautiful design, and gold and jewelled bangles of ancient workmanship tinkled musically on her creamy-white arms. Her poise was one of youthful grace and beauty.

"Father!" cried the girl.

The red lips curved in a smile of joy as Agran descended from the caravan. The next minute she was in his arms.

"How glad I am to see you home again, my father!" she cried gaily, in as perfect English as Agran's own. "Has all gone well?"

"With us, yes," Agran said, as he kissed her. "But out in the jungle we came across a man of the English race who was badly mauled by a tiger. His beaters were dead, so we carried him to the caravan and brought him here. In the morning I must take him to the house of the nearest commissioner, for there he will have the food and comforts of his race."

The beautiful face of the Parsee girl filled with compassion as she peeped into the caravan and saw the lacerated and bandaged face of the sleeping man.

"But, my father, why should the poor Englishman go to the house of the commissioner? My ayah, who was of his race, taught me to cook and nurse as they do in his country."

Agran looked troubled, and nervously plucked his beard.

"The laws of caste are stronger than the laws of friendship, Zenda," he said slowly. "This man is not of our race."

Zenda's beautiful eyes clouded.

"But what difference does that make?" she cried appealingly. "We are true worshipers of our Temple, but we respect the English, who have built up our railways and our commerce. Remember, too, my father, that a brave English man once saved your life. It would be but a poor return if we sent this injured stranger from us in his hour of need. The household of the commissioner is distant, and the journey may rob him of his chance of life. Father, let him stay, and I will nurse him," Zenda pleaded.

Agran hesitated. But the reminder that he owed his life to one of the derelict's race was a strong appeal. He bade his servants carry the white man into the house.

And as the litter was borne in Hartley opened heavy eyes, to behold, looking down at him compassionately, the loveliest face he had yet seen on earth, and to wonder if he were truly dead, and if this was the first angel come to welcome him to Paradise.

An Indian Romance—The Mystic Ruby.

A CLOUD of dust swirled from the white road as a steaming kabuli pony, pulled up short on its haunches, halted outside the house of Josef Agran. Its rider slipped from the brass-studded saddle and tethered the animal to the trunk of a palm-tree.

The age of the rider was about thirty. His forehead bore the red-painted mark of the Hindoo caste. Clad in a robe of white, his brown face, with its growth of straggling beard, was crowned with a multi-coloured turban.

Reaching the shade of the veranda he dropped into a bamboo chair and clanged the copper gong that stood on a table by his side.

A sleepy-eyed ayah answered his summons.

"My greetings to the mem-sahib Zenda," he said, speaking in Hindustani, and in a harsh, forbidding voice. "Tell her I crave an interview with her."

The ayah hurried off on her mission, and shortly afterwards Zenda came slowly down towards the native visitor with a look of distaste in her golden-brown eyes.

"Greetings, Bhur Singh!" she said coldly. "What is your mission? Do you desire to do business with my father?"

Bhur Singh's piercing black eyes flickered with admiration as they dwelt on the beautiful face of the Parsee girl. He salaamed, then, straightening himself, regarded her with mingled passion and pleading in his haughty face.

"My business with your father will wait, Zenda," said he slowly. "Be seated—there is much I wish to say to you, peerless one."

Although the girl acceded to his wish, and sat down, the aloofness in her manner brought a glitter to Bhur Singh's eyes.

"How fares it with your Englishman?" he asked. Then, with a badly-veiled sneer: "I have no doubt that, under your devoted care and attention, Hartley Sahib is now restored to health?"

"Hartley Sahib is better," Zenda replied, a trace of defiance in her voice, in whose musical tones the man jealously detected a note of regret. "Soon he will leave us for Bombay, to return to his own country."

The thin, bearded lips of the Hindoo tightened.

"It is well," he said grimly. "I have no liking for these Christians—nor is it fitting that they should associate with you. Zenda!" He leaned forward suddenly and caught her hands. "No—do not turn from me, my beautiful Zenda. Surely you have guessed that I came not to see your father, but to tell you of my love!"

Drawing her hand from him sharply, the girl rose to her feet, her creamy-white face flushed with anger, but soon paling to fear as she saw the passion in the evil eyes of Bhur Singh. She had long feared this moment with him, for, an educated Hindoo, of good birth, and a student for the Indian law, he had both power and influence in the district—even greater than her father's own.

Yet between those two stretched the mystic barrier of caste.

"Your words are an insult, Bhur Singh!" cried the Parsee maiden proudly. "You, a Hindoo, and worshipper at Kali's shrine, to speak of love to one of my faith! Are you mad to think that I would change my caste for yours—aye, even though I loved you—which I do not, and never shall?"

Bhur Singh rose, his black eyes aglitter, as the sting of the scornful words sank home.

"Does it lie so?" he said in low and menacing tones. "Beware, Zenda! Already the gossips of the bazaars are coupling your name with that of this Christian. Perhaps rumour does not lie! Is it for one of Hartley Sahib's foreign faith that you scorn my religion and my love?"

The passion in his face caused the now frightened girl to glance back towards the house, as though contemplating flight. Seeing her intention, the Hindoo seized her by one fair, white arm.

"Go, Buhr Singh!" panted Zenda. "Go—or I will order my father's servants to whip you from our doors. How dare you—"

She shuddered. Bhur Singh was smiling the evil smile of unleashed jealousy. The scorn in her voice, the alluring beauty of her face, drove him beyond reason for the moment, and he struggled to draw her closer into his dusky arms.

"Help!" Her cry rang out suddenly, sharply. And Bhur Singh started; he knew that her father usually slept at this hours, and believed that Hartley was absent from the house.

"Help—Hartley Sahib!" cried the girl again.

Came the swift patter of feet on the paved floor, and, crossing the verandah, with a cry of anger, Hartley's stout arm shot outward. With a cry Bhur Singh sagged to his knees, having felt the weight of a British fist.

It was three months since Hartley had been borne to the Parsee's house from the jungle, and though still pale after his long illness, he had regained much of his strength.

"Get up, you black scum!" he thundered angrily. "Get up and clear, or—"

The Hindoo had leapt lithely to his feet; his hand went swiftly to his girdle, and there was the flash of steel. Murder gleamed uglily in his eyes as he crouched with a cry of terror Zenda flung herself between the two men.

But Hartley's hand placed her gently behind him.

"Draw on me, would you scum!" he said hotly. "You want a lesson—and by James you shall have it, too! Draw on a white man, would you—"

With a spring he was on the Hindoo. A powerful hand gripped the man's arm above the elbow—the knife arm—and Hartley locked his leg around the foe. Backward and forward they swayed, the Englishman never relaxing that vice-like grip. Then, with a quick movement, he jerked the Hindoo's arm behind his back. A minute's agony the man suffered gamely, then with a moan he let the knife clatter to the floor.

Hartley gazed at the defeated one with a grin of serene cheerfulness.

"I'm going to give you a thundering good hiding for playing with knives, my dusky friend," he said. Then, turning his head towards the girl: "Run in, Zenda, and send the syce with the tonga-whip—this gentleman needs a lesson in that respect which he should show to women—and he shall have one."

Zenda's tender heart made her hesitate, but she saw the gleam of amusement in Hartley's eyes, and understood. Hartley held the Hindoo till the syce came out bearing the tonga-whip, then he released him. Hartley took the whip and the long lash cracked as he tested it.

Bhur Singh, with a yell of fury and terror, bolted down the garden. Not the lash, but the degradation of it, was what he dreaded, as Hartley well knew, The Hindoo untied his pony and, scrambling into the saddle, spurred into a mad gallop, turning to shake his fist at the laughing white man.

"Hartley Sahib, one day you and yours shall pay for this insult, if fate gives the chance into my hands!" he yelled. "Bhur Singh never forgets!"

"Wish I didn't," laughed Hartley, as he retraced his steps, whip still in hand. "Thought that would settle his old hash, Zenda."

But the girl laid her hand on his arm, and her face was like death.

"Oh, take care. He is a dangerous man!"

Her voice was trembling—trembling anxiety for him! It gave Hartley a glad throb of the heart as he looked at her.

How fair she was—fairer, he thought, than many Europeans, this lovely Eastern maid. Speaking perfectly his own tongue, with the culture of the Indian college lady, it had often been difficult for him to realise that she was not of his own blood and race.

"I don't fear the chap, Zenda," he said softly. "But—" He paused. "Do you forget that to-morrow we have to say good-bye?"

"Do I forget?" she whispered, and in her voice was the sadness that now ate into the men's heart. Hartley knew that the parting from this sweet-natured girl would cruelly wrench his heart.

For those months he had been in her keeping had brought romance into the lives of those two; Buhr Singh's jealousy had not been baseless, and the Parsee bride he had long coveted had given her heart to this lover of blue eyes and northern blood.

"You have been very good to me, little Zenda," he said, as he drew her on stone seat beside him. "I owe my life to you!"

"To my father, who found you," she said softly.

"And to you, who nursed me back from death."

Day was slowly merging into tropical night. A strained silence fell upon them both. A feeling new, and strange, and sweet, was stirring Hartley's blood to something akin to madness—the madness of a love that was stronger than the traditions of family and of race.

The big, red sun sank slowly into the purple haze of the west, instantly transforming the sky into a riot of amber, mauve, and the crimson of molten rubies.

Heavy with the scent of orange groves, a soft wind—the intoxicating Indian night wind—rustled in the feathery palms. Humming birds of brilliant hues hovered over the Indian cresses and trumpet-flowers. From the village came the soft roll of tom-toms, the thrumming of stringed instruments, and bursts of Indian songs—bizarre, passionate, and beautiful.

It was a garden of enchantment. Tonight Edward Hartley felt much of its magic spell. The brief season of happiness was ended. To-morrow he would be gone, and nothing but memories would be left. He turned and looked at her as she sat, flecked with the silver light of the moon, a slender figure against a background of lichened stone.

Their eyes met, and it seemed to the young man that something was dawning in her heart which caused his own to throb responsively.

"Zenda," he whispered, "it's more than I can bear to think of parting for ever from you. I can't realise it. Part—without a hope of ever meeting again, for my days in India are done!"

Hearing her quivering sigh, that was like a sob, he passionately caught her hands.

"I love you," he said simply. "I have from that first day, when I thought myself dying—or dead—and you came to me, like—like the first angel to welcome me into the great Valhalla. Don't send me away from you, Zenda—I can't go alone! Marry me—come back to England with me as my wife!"

"You—you know it can't be," breathed the girl. "My faith is not yours. And my vows! Father would never consent. It would mean ostracism for the rest of my life—and for yours. For neither my people nor yours—"

"Zenda, darling, tell me one thing—do you love me?"

"I love you—yes. Oh, yes!" Her voice was low music. "But—Oh, my dear—"

"Listen," he said, and he crushed her to his heart and kissed her lips. "I will make any sacrifice for you, my darling. I know there is only one way, and I will take it. I will become of your own faith——"

"Oh, no—you cannot, must not—"

"I will! Love and you are more precious to me than aught in the world," he said. "And it is the only way your father would consent to, I know. Come, and we will go to him now."

The old reckless light was shining in his eyes. He was not narrow-minded enough to think that the religion of other races must needs be less noble than his own. Yet his face was white as he kissed the lips of his love once more, and led her back into the house.

Josef Agran was squatting on a pile of cushions when they entered, Hartley leading Zenda into the old merchant's private apartment. Rising, Hartley was courteously motioned to a seat on the divan.

"Full arrangements have been made for your journey, Hartley Sahib," Agran said. "We shall be sorry to lose our guest. I will accompany you as far as Rhanpur. Thence a compartment has been reserved for you to Bombay."

Hartley looked with gratitude at the venerable, wrinkled face of the Parsee.

"You have been a generous friend," he said in a low voice. "And as your reward, it seems that I must now seek to rob you of your dearest possession. Zenda and I love each other, and I have come to ask your consent to our marriage. I am willing to embrace your faith."

Agran looked at them, but there was no expression of displeasure on his kindly face. Perhaps he had not been wholly blind to the romance that had followed the coming of this Englishman.

"Are you aware of what our religion is?" he gravely asked. "It is not to be lightly regarded, the step you contemplate."

Hartley shook his head; he knew but little of such matters. And the old man continued:

"We are not of the Indian races. Descendants the one-time great Aryan race of Central Asia, that accounts for the whiteness of our skin. I, who am an old man, have grown yellow with the suns of India, but Zenda has the fair colouring of your own white women almost.

"Our race emigrated to India many hundreds of years ago, and the country owes much of its prosperity to our labour and enterprise. Our deities are the sun, water, and the earth. Because of our reverence for the earth we erected our 'Towers of Silence,' in order that our dead might not desecrate the earth, and we suffer our bodies to be devoured by the vultures on the tower gratings. Yet in spite of this we worship the true God of creation, known to us as Ormuzd. Think well before you decide."

"I have decided," Hartley said gravely and firmly. "My faith shall be that of the woman I love."

"Zenda, do you love this man?"

"My father!" Her voice faltered. "Life without his love would be as a long night without a star."

Agran was silent for some minutes. Then he rose and placed his hands affectionately on the white man's shoulders.

"My son," he said with emotion, "I consent. I am old, and not long for this world, and it would be unjust if I denied my daughter her happiness in order that she should stay to comfort my declining years. I will send a runner to the Temple of Ormuzd, so that the head magi may prepare for your conversion and marriage ceremony. It is my dearest wish that you marry and sail for England immediately, as some of the fanatics of our creed do not look favourably upon inter-racial unions, and it would be dangerous for you to remain here."

He left Hartley and crossed over to Zenda. The girl clung tenderly to him.

"If I could allow Zenda to take up your faith I would," he resumed; "but we cannot break our temple vows, for to us of the East they are dearer than life itself. Zenda has been my dearest possession since her mother died, and India, gorgeous and beautiful though the setting is, is sordid and vice-stricken. Be cause of that I have long cherished a desire that one day my daughter would marry an Englishman and go back with him to his own country, for there your women are treated with chivalry. Then so let it be."

He kissed the girl fondly, and went back to the divan.

Silently they left the room, and for a long time the old man sat motionless, his shoulders bowed. At length he rose and crossed over to a brass-bound chest that stood in a curtained alcove. He unlocked it, and, taking out a goat-skin bag, walked over to the table and emptied the contents on the tapestry cloth.

On the table now lay a small heap of jewels that caught the flickering light of the kerosene lamps and flung back a thousand gleaming shafts of colour. Amongst the poorer stones flamed one huge, blood-red ruby of many facets, a magnificent gem, worthy of a setting in a king's crown. Agran's face paled, and he glanced almost furtively towards the open window as be pressed it to his heart.

"For years have I basked in thy lustrous beauty," he muttered in the Aryan tongue; "but now thou shalt be the marriage dowry of my beautiful Zenda. In the new land whither she goes thou shalt, whatever befall her, preserve her from want. Cunning old bargainer and faithless as Margha was, I met him, cunning for cunning, for thy possession!"

This neither Hartley nor Zenda heard.

SOON after the first flush of dawn had tinted the eastern sky the caravan started on its journey, and after many hours of travelling over sun-scorched, boulder-strewn plains they arrived at Rhanpur.

Outside the station, thronged with picturesque, chattering natives, they halted, and when Agran had given instructions to the driver they made their way to the train.

At Bombay they found a private gharry, drawn by a team of plumed and decorated Arabian horses, awaiting them, and they drove towards the Temple of Ormuzd.

Leaving the wide, sweeping streets, flanked by stately buildings, behind, they were soon in the midst of densely-populated native quarters.

The cobbled streets were crowded with tonga-waggons drawn by teams of hump-backed oxen, smiling, chattering men clad in multi-coloured loin-cloths and turbans, and native women, their sarees drawn across their mouths, with tall brass lotahs upon their heads.

Merchants and pedlars squatted down on the narrow pavements, with their merchandise set out before them; fruit-sellers with huge slices of ruby-seeded melons, mangoes and pines; spice merchants with piles of amber, saffron, and red-tinted spices set out upon white cloths; dentists and bone-setters, sellers of ivory, curios and silks.

The gharry, with clanging gong, at length entered the quieter quarters inhabited by the Parsees. Here stately residences of sculptured stone studded with mosaic patterns, lined the streets, and fair skinned men and women, in costly sarees, cheered the bridal procession as it trotted by.

Finally they drew up before the Temple of Ormuzd, and a venerable-looking magi, swathed in his white priestal robes, came forward and led them through the lofty arches to the altar.

The temple, decorated with designs of mosaic and costly tapestries, and studded with rich carvings of cedarwood and stone, was dimly lit and deserted, for Agran had ordered the ceremony to be a quiet one.

Hartley and the Parsee girl knelt down, side by side, before the gilded altar, and, following the responses of the priest, Hartley took the vows. Afterward, the marriage ceremony, solemnised by the priest in an ancient Persian dialect, was interpreted to him by Agran.

The ceremony over, they re-entered the gharry and were driven to the Alexandra Docks, where a stately liner, her white paint gleaming in the sun, rode at anchor. Joseph Agran, omitting nothing, had booked their passages aboard the boat.

Quartermasters were already shouting for the passengers to hurry aboard, and one of the gangways was being hauled up on deck when they arrived.

Zenda clung tearfully to her father, and the scene being painful to Hartley, he left father and daughter alone for a moment, and directed a steward as to their luggage.

"Do not grieve, my daughter," Agran said gently. "It is for your own happiness that you leave me. Here is your marriage dowry. Amongst the stones you will find a large ruby. You must not let it be seen in India! It is for your safe future, Zenda. Should ill befall you in a foreign land it will preserve you from want. But guard it as a secret, since it has itself a secret which may well make its ruby redness be as a blood-drop from a faithless heart!"

A bell on the ship's bridge clanged harshly. Hartley hurried forward to take his farewell of the large-hearted old man, and then they hurried up the gangway.

With screaming siren the ship steamed slowly from the quayside and out into the sparkling blue expanse of the Indian ocean.

When Bombay became swathed and hidden in the haze of distance Zenda lifted her beautiful face to her husband's adoring eyes.

"You will never regret the vows you have taken, Edward?" she asked gently.

Hartley gazed out over the ocean for a moment; then he fondly kissed her. Already he felt remorse at being a renegade from his faith but love had been stronger than all.

And over them brooded the sinister shadow of Bhur Singh's vow of vengeance—though it was not until many years had passed that the Hindoo's shadow was to fall upon Zenda's path again, and the mysterious ruby bring tragedy into the life of the Parsee bride.

Twenty Years Afterwards—The Betrothal Gift—The Face at the Window.

"A TELEGRAM, sir," said Mrs. Bardell, Sexton Blake's housekeeper. "And of all the cheeky and owdacious young varmints as brought it—"

"Thank you, Mrs. Bardell." Sexton Blake looked up languidly from the book of travels he had been reading, and took the buff-coloured envelope from a red-faced and very indignant old lady's hand, Mrs. Bardell yielding it with a resentful snort at the interruption.

It was late afternoon at the famous criminologist's rooms in Baker Street. After a quiet day in an unusually quiet week, Tinker, Sexton Blake's clever young assistant, reclined upon a couch, having at the moment no more edifying occupation for idle hands than tickling the ears of Pedro, the bloodhound, that famous sleuth who, in his career, had made almost as many friends—and foes—as Blake himself.

The peaceful quiet of the sitting-room had been suddenly broken by a peal on the bell below, followed by muffled sounds of conversation, punctuated by shrill exclamations of indignation. Then had come the heavy footsteps of Mrs. Bardell on the stairs, and her flushed appearance with the "wire."

"A cheeky young varmint!" continued Mrs. Bardell, raising her voice, as one determined to have her say. "Arsks me if this was the place of the famous detective, Sexton Blake, as could trace anythink what was lost. As innercent as a child, I says 'Yes,' and what does the owdacious young himp do but devise me to permission you to trace me long-lost beauty! And for no more than telling him to take 'is muddy hoofs off my clean step!"

A sound suspiciously like a chuckle came from the couch, and with wrathful mien Mrs. Bardell marched out of the room, closing the door with unnecessary violence in protest.

As Blake took up a paper-knife and slit open the envelope, Tinker sat up expectantly.

"Hope it's something exciting, guv'nor," he said. "I've been hoping something would turn up, if only the mysterious poisoning of Lady de Vere Plantaganet's favourite tabby. Things have been pretty dull lately. What's the latest?"

"I am afraid your craving for abnormal excitement will not be gratified on this occasion," Sexton Blake said. "It is an invitation from Sir John Currier, C.B., a very old and esteemed friend of mine, who is giving a betrothal dinner at Wierdale Court, his Surrey house, in honour of his son's engagement. Young Jim Currier is a fine young fellow, recently called to the Bar, Tinker, and—"

"Oh, I remember, guv'nor," Tinker said. "Wasn't he the young barrister you helped on the Bothwell case a year ago?"

"The same, my boy. And although Sir John has not given us much time in which to prepare we will not disappoint him. Ring up the garage people, and ask them to have the Grey Panther round in an hour's time."

Tinker went to the 'phone and ordered the car. A drive into the country, with a dinner at the other end of it—to say nothing of a peep at Society's latest bride-to-be—was better than an evening at home, anyhow, although it was not quite the type of excitement which Sexton Blake's restless young assistant craved. Mrs. Bardell sniffed with an aggrieved air when, a little later, she went up to find Blake and Tinker in evening attire. Her somewhat inflamed face revealed that she had not yet recovered her outraged temper.

"We are dining out, Mrs. Bardell," said Sexton Blake. "At Wierdale Court, in Surrey."

"Then all as I can say is, it's a sin and a shame!" declared the indignant landlady. "I've got in the loveliest leg o' lamb as never was, and new pertaties, too!" A louder sniff. "To say nothink about neglecting of the detective work, which things is so slack as we'll soon be on the parish, and me never being so before, Bardell always bein' proud, if poor."

"Noble Bardell!" murmured Tinker.

Mrs. Bardell cast a warlike eye upon that young gentleman's evening dress.

"An' to say nothink, neither," said she, "about a young jackernapes getting a size larger in heads by going to swell affairs all dressed up like a butler or a waiter! It's most disintegratin', what things is comin' to. In my young days little boys didn't swank about in evening clothes—only a nightgown, when they be cheeky, and spanked before being puttin' to bed!"

"Toodle-oo, dear old thing!" chuckled Tinker, as he followed Blake to the car, which had arrived. "If it isn't any better when we get home you shall see a doctor! Toodle-oo!"

As they were threading through the traffic of Oxford Street, Blake at the wheel of the famous car, the detective gave Tinker some further particulars of their host.

"Until recently Sir John was one of the most prominent men in the Indian Civil Service," Blake said. "Retired three years ago, and was knighted for excellent administrative work in the Madras district. A fine old fellow of the old school, irascible, good-hearted, but with the deep prejudice of his class. His son Jim six weeks ago became engaged to Miss Lillah Hartley, one of the most charming debutantes of the season, and the dinner tonight is obviously to celebrate that event."

"Jove, guv'nor! He's a lucky dog, then! I saw her portrait in an illustrated paper some days ago. She's a stunner!"

Sexton Blake smiled.

"Lack of ability to express yourself in orthodox English is one of your failings, Tinker," he said reprovingly. "But you are right, my boy Miss Lillah Hartley is a stun—er—I mean she is exceedingly beautiful. She is the daughter of Lady Hartley, one of the most popular women in English society."

"A merry widow, isn't she?" said Tinker.

"Her ladyship is widowed, yes. Her late husband, Sir Edward Hartley, who came into the baronetcy and family estate in Surrey ten years ago, was killed two seasons back by a motor-car accident. Young Currier gave me these particulars when I met him in connection with the Bothwell case."

Blake presently halted at a jeweller's, where they purchased a fitting present for the betrothed pair; then they were soon speeding southwards. Less than an hour's driving brought the Grey Panther to the poplar-flanked drive of Sir John Currier's residence, which lay half hidden in a well-timbered park.

A mechanic took charge of the car, and Sir John, who had observed their arrival from the house, came forward to meet them.

He was a red-faced man of sixty, with stubborn chin and hard features, relieved by twinkling blue eyes. His left foot was encased in a much-slashed slipper as a concession to his prevailing malady—gout—and as he walked he leaned slightly on a stout stick.

"Good of you to come, Blake," he boomed, shaking the detective's hand. "Sorry I didn't give more warning. Shockin' memory, y'know. Tinker, I suppose? How-de-do, young fellow? Jim will be so glad to meet you again, Blake. Says you made him on that Bothwell case. Lucky dog—what?" He chuckled. "Wait till you meet his girl!"

Leading them into the hall, Sir John rattled his stick forcibly against the oak settle as a twinge of gout took him.

"Jackson, you black rascal! Where are you?" he roared. "Jackson!"

"Comin', sah!"

"Oh, there you are! Worst of these confounded niggers, Blake. You can't see 'em in the gloom!"

A huge African negro came forward, showing the whites of his eyes and a set of perfect teeth in a grin. Keeping well out of range of the stick, Jackson took their luggage and coats from the guests, and, with a grunt, the irascible Sir John led them into the drawing-room.

Lady Hartley, the mother of the bride-to-be, who was acting as hostess, came forward to greet them cordially. Little more than forty, Blake thought her a woman of striking and peculiar beauty, though to the detective's keen eyes her features had a slightly foreign cast. But in her low and musical voice there was no trace of accent as she greeted them.

"I am truly glad to meet you, Mr. Blake," her ladyship said. "We have heard so much of you from Jim—and of Mr. Tinker, too!"

The charming smile she bestowed on Tinker quite won that young man's heart.

A moment later, as they were being introduced to Lillah Hartley, Blake found himself bowing to one of the loveliest girls he had ever met.

Tall and supple, with her mother's large, tender brown eyes, and a wealth of tawny hair, thickly coiled about her shapely head, Jim Currier's beautiful fiancée wore an evening-gown, the well-chosen tone of which softened in effect the warm olive tint of her skin. Again that puzzled look crept into his keen eyes, and Blake glanced quickly towards Lady Hartley, who was chatting to Tinker.

Then, with a rare but slightly puzzled smile in them, his grey eyes came back to the girl.

"Allow me to congratulate you, Miss Hartley," he said. "I am delighted to be present at what must be a happy day for you and Jim."

"Thank you, Mr. Blake." Lillah smiled at the famous detective. "It was good of you to come. Jim wished it very much. I must confess that I, too, was curious to meet England's most famous criminal-hunter."

"I trust that he comes up to your expectations," Blake said, with a laugh.

"Perhaps not quite!" She echoed his laugh. "I half expected to meet a bullet-headed person, wearing a miniature handcuff as a tiepin, and with a bundle of warrants protruding from his pockets."

"Dear me!" said Blake, joining in the laughter. "If young ladies form such horrible impressions of my calling, I shall be losing my assistant. Tinker is very susceptible to the opinions of the fair sex, and I shall be having him give me notice."

At this juncture Jim Currier came up. He was a tall, athletic young man, with his father's twinkling blue eyes and firmness of chin.

"Hallo, Blake! Jolly glad to see you," he said, with a hearty grip. "You'll stay a few days, of course, old man? I can promise you a run with the trout and some golf."

"Thanks, Jim!" answered Sexton Blake. "Unless some urgent matter recalls me to town, I shall be delighted."

The grinning Jackson announced dinner, and the guests, mostly local people, filed into the dining-room.

Wierdale Court was one of the show places of the county, and the dining-room was panelled rich old mahogany—a costly whim of a former Currier. The flames of the log fire racing up the wide chimney were reflected in a ruby gleams upon its tawny surface, throwing into relief the white damask, the flowers, and the silver on the table.

The dinner passed amid gay chatter, chiefly relating to sport and local affairs. When the toasting glasses had been filled Sir John rose to his feet.

"It gives me great pleasure, ladies and gentlemen, to publicly announce the engagement of my son Jim to Miss Lillah Hartley," he said. "You are all friends of my family, and of Lady Hartley, who so charmingly fills the position of hostess in an old widower's home tonight, and I know you will join me in every good wish for the long life and happiness of my only son and his future charming bride."

After admiring the rich colour of the old port, and with one doubtful, downwards glance at his gouty foot, Sir John drained his glass with the air of a man performing a duty at the expense of his constitution, and bowed gallantly to Lady Hartley.

There were other speeches, including one from Sexton Blake, and after Jim had responded Lady Hartley rose to her feet. Opening a jewel-case that lay on the table before her, she took out a magnificent ruby, set in the form of a pendant.

A hum of admiration came from the guests, and even Sexton Blake, indifferent as an rule to what he termed a "bauble," could not repress an exclamation of surprise as he noted the stone's size and seemingly living rays of blood-red fire.

"My betrothal gift to Lillah," her ladyship said quietly, as she fastened the glittering jewel around the girl's neck. "It came into my possession on the happiest day of my life. I trust it will prove as faithful a talisman of happiness to her as it has always been to me."

"Hear, hear!" said Sir John. "Good luck and long happiness to you, Lillah, my dear. B'George, it's a beauty! I've lived for years in India, the home of great jewels, but I've never seen a grander ruby than that."

Humbler gifts were given to the radiantly happy lovers, and then dessert was served.

Lady Hartley's magnificent gift turned the topic of conversation to famous rubies.

"Talking of fine rubles always reminds me," said Sir John, "of the stir in native circles in India some twenty years ago, when the great Kali ruby was stolen from one of the Hindoo temples. It formed the eye of the goddess Kali, and one morning the old priest was found stabbed on the steps of the shrine. The ruby had been wrenched from its setting in the centre of the idol's forehead, and every search made for it was made in vain. The Customs authorities had orders to prevent all rubies of large size leaving the country, but nothing further was heard about the idol's missing eye; and many believe it still to be in the country. The best place for it, too!" he ended grimly. "The trail of these great Hindoo jewels are only too often flecked with blood. Good job this is not one of them—though it's splendid enough to be one of those dangerous religious stones."

As the old baronet finished his narrative, Sexton Blake's keen ears caught the sound of a sharply indrawn breath. He looked quickly towards Lady Hartley. With pale face and tremulous lips she was staring with fascinated eyes at the huge ruby that was now pulsating with blood-red, sinister fire upon her daughter's neck. Again that puzzled look crept into the detective's eyes. He read fear in her ladyship's face.

During the rest of the evening Lady Hartley seemed preoccupied and contributed but little to the lively conversation. At midnight when the guests, excepting Blake and Tinker, had departed, she breathed a faint sigh of relief. Jim Currier fondly hissed his fiancée good-night and escorted Lillah and her mother to their car.

The drive home was a short one. Lady Hartley and her daughter entered a fine old Tudor mansion, ivy-clustered and picturesque, that adjoined the Wierdale Court estate, and a trim maid came forward and helped them with their cloaks.

"A letter was handed to one of the kitchen-maids, addressed to you, my lady," the girl said. "I have placed it on the table in the library."

"Thank you, Morris. You may go to bed now. I shall not require anything. Good-night!"

As the maid went to the servants' quarters, Lillah turned to her mother.

"Will you excuse me, mother? I feel tired, and would like to go straight to bed. I don't know how to thank you for your present. It's simply splendid! Why, I didn't know you had such a splendid stone! I have never seen it before!"

At the mention of the ruby her mother's eyes became troubled.

"I have had it for many years, Lillah," she said thoughtfully. "It was given to me on my marriage by your grandfather—my father. But I—"

She broke off suddenly.

"My grandfather!" said the girl. "I have never met him, mother—never any of your people!"

Lady Hartley's olive-tinted face slightly flushed.

"My people are not in England, Lillah—I have told you that before. But go to bed now, my dearest. I am not in the mood for questions tonight."

Zenda held Lillah in her arms and kissed her fondly. She had hidden, for her daughter's sake, her own Parsee origin. She had feared prejudice against her half-caste daughter in her husband's country, and Edward Hartley had helped his wife to guard that secret of the past, for Lillah's sake.

Not a soul in England, save Zenda herself, knew that beautiful Lillah was a Eurasian!

"You do not look happy tonight, mother dear!" Lillah said, with an anxious glance at Lady Hartley's troubled face. "And—and it should be such a happy night for us both!"

"Don't worry, my dear," her mother answered. And the sadness in her voice came painfully to the girl's ears. "I am only tired. Go to bed now, Lillah. I shall not be long. Good-night, my darling."

Lillah, her beautiful eyes plowing with affection and happiness, kissed her mother and went up the stairs to her room. Lady Hartley's soft, golden-brown eyes lit up with a wealth of tenderness as she watched her go. Since the tragic death of Sir Edward Hartley she had lavished all her love on the beautiful girl who had brought so much happiness to them both. It had been for Lillah's sake that Zenda and Hartley, three years after their arrival in England, had broken the vows made in the Parsee Temple of Ormuzd and become of the English Church.

When Lillah had gone from sight she turned and went to the library. She sank wearily into a chair and her eyes sought the portrait of her husband that stood upon the desk before her. Raising it, she pressed it to her quivering lips; but he whom she had so loved and revered, he in whom her very life had been bound up, was now dead and unable to comfort her.

"A mad marriage, perhaps," she murmured, "But, oh, my husband, to go with you through that madness again! And yet—my child! If they knew all, they would scorn her—call her of 'nigger' blood! Oh, God of my dear husband, in whom I now believe, help me to guard my darling's secret to the end!"

The reckless, laughing eyes and handsome face so vividly portrayed opened the floodgates of memory, and her mind raced back across the past. She saw once more the clamorous Indian docks, and the stately liner. Her Parsee father's parting words came back to her with a new significance:

"Guard this ruby as a secret, since it has itself a secret which may well make its ruby redness be as a blood-drop from a faithless heart."

Her eyes fell on the letter which the maid had placed for her on the library table. With a swift movement she went to the table, opened the letter and read it. Her face became pale with apprehension. Three days before she had received just as mysterious a letter in the same hand. But then she had not known!

"What can it mean?" she muttered uneasily. The letter ran thus:

"Lady Hartley will meet the writer tonight in the drive end at sunset, and must observe secrecy as to this appointment. She must yield up what is demanded of her, otherwise she must be prepared to have her past revealed to the world—

B.S."

She crushed the letter nervously in her hand, an uneasy thought that it might be connected with the ruby obsessed her mind and terrified her. She had not suspected this until she heard Sir John's story tonight.

Could the stone she had given to her daughter tonight be the missing "eye" of the goddess Kali?

There was reason for Lady Hartley's fear, for, being of the East, she knew its fanatical reverence for the stolen ruby that for countless ages had adorned the brow of Kali—chief goddess of the Hindoos—with ten million worshipers at her shrine. She knew of the terrible vendetta that had been sworn by the high priests and of the vengeance, swift and sure, that would follow in the wake of the possessor. To those of the Kali caste the ruby was more precious than life itself.

"B.S.," she whispered. "Who can it be? Not—not Bhur Singh!"

Suddenly she sat tense and rigid. Someone was watching her. She felt sure of it—felt fierce, invisible eyes upon her. The knowledge bore upon her consciousness until she thought she must scream to break the silence and the spell of those watching, unseen eyes. She turned to the window; then, with a little cry, paused, her hand pressed to her heart, her breathing suspended.

A brown face was pressed against the glass!

There came a click as the catch was forced, the half-closed curtains parted, and a man stepped into the room.

A Mysterious Crime—Lady Hartley's Silence—The Ruby Disappears.

"TINKER!" Sexton Blake was vigorously shaking his young assistant by the arm.

"Wake up, my boy! Look alive!

"Warrer-marrer?" murmured the sleeper. "Warrer—Oh! Great pip! Is that you, guv'nor?" Tinker was awake instantly. "Anything wrong?"

In the bright light of early morning he saw that Blake's expression was graver than usual and that his lips were tightly compressed. Clad in his dressing-gown, unshaven, and with ruffled hair, it was obvious that the detective had only recently left his bed, he and Tinker having been accommodated with adjoining rooms at Wierdale Court.

"Be quick into your clothes, Tinker!" Blake said hurriedly. "Something has happened at the Larches. That's the residence of Lady Hartley and her daughter, you know. Miss Hartley has just 'phoned through to Jim and wants him to get there quickly, accompanied by myself and you. She seems in a pretty bad way about it, my boy. As soon as you are dressed, get the car ready, and we'll slip off. Sir John is not yet risen, and we don't want to worry him before we know what's wrong."

Blake hurried from the room. Tinker, his mind in a whirl, sprang out of bed and after hastily dressing himself, ran down to the garage. Starting the car, he brought it round to the front steps, where Blake and Jim Currier were already waiting. The young man had hurriedly donned a sports coat and grey flannel trousers. He was unshaven and very pale.

"By heavens! This is awful, Blake! What can it mean?" Jim said huskily. "Lillah, on the 'phone, said it was something 'dreadful'! She was in a terrible way about it. I wonder—"

"It is a waste of time to conjecture," answered Blake crisply. "Get in the car, Tinker. You had better sit beside me, Currier, and direct me. And don't get uneasy, old chap; it may be nothing very bad, after all."

"You don't know Lillah, Blake. She doesn't get hysterical about nothing," groaned Jim. "And she was just wild with terror—"

The powerful car swept through the lodge gates, and soon after they had raced through the old-world little town of Wierdale they reached the Larches.

A trembling, white-faced manservant met them at the door, and Jim clutched the man's arm in his agitation.

"Where are Lady Hartley and Miss Lillah, Jenkins? What has happened?"

"Her ladyship is in the morning-room sir," the man said shakily. "Dr. Long and Inspector Mulberry, of the local police, are with them. It's terrible—terrible, sir!"

"The police?" gasped Jim. "Why, what—"

"Yes, sir; there's been murder," said Jenkins, in a trembling voice. "Or what looks like murder, for the doctor says the wound couldn't have been self-inflicted. And her ladyship was found by the nigger—"

"Pull yourself together, my man, and don't ramble," Blake said sharply. "Tell us just what has happened. When was this discovery made, and by whom?"

"One of the maids, sir, rose at the usual time and went into the library to tidy up. She thought her ladyship in bed, but was amazed to see her lying on the floor, unconscious. She thought she'd just fainted, but as she bent over her, trying to revive her, she saw something else, and jumped up with a scream. It was the body of a black man, lying alongside her ladyship—stone dead, and with a dagger sticking in his neck!"

"Good heavens!" gasped Currier.

"The girl hadn't noticed the man before sir," went on Jenkins agitatedly. "It was not yet full light, and, the man being black, she hadn't noticed. It gave her a fair shock, and she runs, screaming, into the hall. I went then and saw—saw—" He broke off with a shudder. "I 'phoned through for the police and the doctor. That's all I know."

"You had better go in to them, Jim," Blake said quietly. "Tinker and I will have a look at the library at once. The body has not been removed, I suppose, Jenkins!"

The old man wrung his hands.

"No, sir. Inspector Mulberry said nothing was to be disturbed. He's with Miss Lillah, questioning her, now. I don't know if I'm doing right by taking you to the library, sir, as Inspector Mulberry said—"

"I am a detective, Jenkins—Sexton Blake. I have Miss Hartley's authority to appear in this case. You may be sure I'll not abuse any privileges or interfere in any way with the authority and investigations of the police. A black man, you say?"

"Yes, sir—leastways, coloured."

As Jim hurried off to see Lillah, Jenkins conducted Blake and Tinker to the scene of the tragedy.

The library was a large, well-furnished room, and along the panelled walls ran well-stocked bookcases. Opening out upon a veranda was a wide French window, and near this lay the huddled figure of a man of colour. The morning sun, streaming in through the window, caused something to sparkle and glitter on the dark neck. Blake crossed swiftly towards the stark figure, and, dropping to one knee, made a careful examination.

The glittering object proved to be the jewelled hilt of a toyish and elaborately chased dagger, the slender blade of which was buried deeply. The detective examined it closely, but did not remove it. Blake always respected the primary authority of the official police.

Next he peered closely into the dusky face. Sexton Blake never, even when out on pleasure bent, travelled without certain small instruments which his methods and his professions experiences had many times proved invaluable. He took out his powerful magnifying-glass, and, after polishing the lens on his handkerchief, closely scrutinized the man's forehead, on which some slightly abnormal appearance, had riveted his attention. Then he turned to Tinker.

"Here, my boy," he said quickly. "Take a peep through the glass at the centre of his forehead. That's right—just there. What do you make of it?"

"Why, guv'nor, there's a patch of skin, in the exact centre, lighter in colour than the surrounding skin. It's cracked and peeling a little, too," answered Tinker.

"Exactly, my boy. And if you will look closer, you will see, embedded in the pores on that small spot, some minute specks of what appears to be red pigment. The man belongs to one of the Hindoo castes, I feel sure. They wear, sometimes, a tattooed—sometimes a painted—mark on their brows, in order that these different castes may be distinguished. The mark in this case, I should say, has been painted regularly for years, as witness the skin's comparative lightness of colour. The last time this caste-mark was made, judging by the fact that some of the pigment still remains, was as recent as a month or five weeks ago, I feel sure, giving us the valuable hint that the man has not long left his own country."

"I believe you're right, guv'nor," Tinker said. "Anything else? That looks a curious dagger!"

"I believe it to be of Indian workmanship," Blake said. "And whoever stabbed him used considerable violence. The blade has pierced the neck from behind, and severed the jugular vein. At a rough guess, I should say that he has been dead about six hours."

"Who do you think the chap can be, guv'nor?"

Tinker was looking down, with mingled compassion and curiosity, at the dead face, its strong features rigid in the set of the death agony.

Sexton Blake looked up from a close scrutiny of the hands.

"In his own country he is probably a man of some position, for his clothes are good also his linen, which is void of any marks. You will notice that the tailors tab has also been removed from the coat. I have examined his finger-nails, but there is no trace of his having clutched at anyone. They are unbroken and hold no shreds of cloth. The contents of the finger-nails have before now afforded me a valuable clue in a murder case. I think that we may deduce that he was taken unaware. The furniture is not disarranged, as you see. But the strongest suggestion that there was no struggle lies in the fact that he was stabbed from behind."

"Have you noticed how clumsily his tie is knotted, guv'nor?" asked Tinker. "Seems to have been grabbed hold of, too!"

"Yes; I was coming to that. It is far from being the orthodox knot, and gives an impression that he was unfamiliar with European dress. That was quite a smart point of yours, my boy. It bears out my opinion that he has not long left his native country, in spite of his well-groomed appearance, and Western fashionable attire."

Heavy footsteps sounded along the passage and soon the door opened, to admit a burly, red-faced man, blue-serged, and bearing the in ineffaceable stamp of the police. His red face showed a tendency to turn purple as he saw Blake and Tinker.

"Hullo! What the dickens are you doing in here?" he said gruffly. "I gave orders the no one was to come near. You'll be for the high-jumps if you've touched anything! What are you—newspaper men?"

"Good-morning!" Blake said calmly. "You are Inspector Mulberry, I presume?"

"And who the dickens might you be?" snapped the police-officer, with a glare.

"My name is Sexton Blake," said the detective, with a quiet smile. He opened his jacket, and exposed a silver badge. "You will see I carry an authoritative badge as acting—through Detective-Inspector Rollings—for Scotland Yard. I have also the additional authority to investigate conferred upon me by Miss Hartley."

Inspector Mulberry grunted, but at the mention of Scotland Yard his manner became a little more mollified. But this was the biggest case his placid career as a country police-officer had yet offered, and he did not take the intrusion with any pleasure.

"Hm! I suppose your presence will be all right, then. You won't find a fat lot to interest you here, Mister Blake. The case is pretty clear. Her ladyship is coming round now, so I shall soon get a statement. Not much doubt as to who killed this poor chap, I'm afraid."

"Meaning?" inquired Blake, with a barely perceptible lift of his eyebrows.

"Meaning that everything looks thundering black against her ladyship," Mulberry said bluntly. "I questioned the servants, and found out that the dagger belongs to her, and is used as a paper-knife. This nigger evidently came here late last night to see her, and they quarrelled. She was lying on the floor—just there, by those chalk-marks—when I was called on the scene, and clutched in her hand I found several shreds of silk that match the nigger's tie in colour and texture. All I've to do is to find out why he came, and why they fell out."

"Indeed?" said Blake quietly. "All you lack, then, is the motive?"

"And when I've got her statement, see, I shall jolly soon have that!"

Tinker eyed his master with undisguised consternation, but, except for a quick gleam that shot into Blake's eyes, his face was impassive.

"What of the man's pockets?" Sexton Blake inquired. "They are now empty, so I presume you have taken charge of the contents. Is there anything which may serve to identify him?"

"Nothing at all," Mulberry said. "Except for a gold watch and a good sum in paper money, they contained nothing of importance."

Blake's grey eyes became interested.

"A gold watch?" he repeated quickly. "Have you any objection to my examining it? An expensive watch generally carries the maker's name and its guarantee number. It may be possible to trace the man's identity from that."

Mulberry grinned triumphantly.

"You'll draw a blank, I'm afraid, Mister Blake. It's gold right enough, but it doesn't carry any maker's name—not even the hallmark," said the inspector, with a thinly veiled sneer. "I've heard of your wonderful methods! Perhaps you'll tell me what you 'deduce' from that?"

"Certainly, Mulberry," said the great criminologist cheerfully. "The absence of a sign may be a more important clue than its presence. If there is no hallmark, it helps to prove my theory that the man is a native of India."

Inspector Mulberry stared at him a little blankly, and scratched his close-cropped head.

"In India, inspector," Blake said quietly, "it is possible to purchase articles of gold cheaper than in this country. The gold is mined in the northern districts, and much of it does not come to England to be stamped with the British hallmark guarantee. A heavy tax is therefore evaded."

Mulberry walked to the table on which the watch and money was placed.

"I think you will find I am correct, Mulberry," Blake said, as he joined the inspector, and took up the watch.

"Oh, I dare say!" grunted Mulberry. "Not of much importance, anyway. I knew he was a nigger of some sort. I've sent particulars to the Yard, so I expect the photographers down soon. I'm going to her ladyship now, so I'll lock the door. There'll be the dickens of a row if anything's touched!"

Blake was silent as they proceeded to the morning-room. As the inspector had said, things were beginning to look black against Lady Hartley, although the evidence was circumstantial and motive was so far lacking. That she should have been discovered alone and unconscious with the man who had been killed by her own jewelled paper-knife was disconcerting, to say the least.

With ashen face Lady Hartley, who, it was plain to see, had only recently recovered consciousness, looked fearfully at the hard-featured official as they entered. Jim and Lillah stood beside the couch on which she lay, and were trying to calm her agitation.

Mulberry strutted towards her, and wetting the point of a pencil, jerked out a well-thumbed notebook.

"Sorry to trouble your ladyship," he said brusquely. "But it's my duty to take a statement from you, so I'll be obliged if you'll tell me exactly what happened in the library early this morning."

Lady Hartley's golden-brown eyes filled with terror.

"I know nothing—nothing!" she cried wildly. "Oh, please do not question me. It is like an evil dream. I can't tell you—anything."

There was deliberate evasion in her words, and Mulberry eyed her narrowly. Didn't look quite English—though deuced good-looking. May have had some past connection with this dead "nigger." Well, he was going to find it out. She couldn't fool him!

"Don't you see how awkward things are looking, your ladyship?" he said bluntly. "Who is this nigger fellow, and what was he doing here last night? I must impress upon your ladyship the necessity of answering the questions of the police."

"I—I can tell you so very little, I do not know this man," she replied, with fear-stricken, averted eyes. "How he was—was murdered I cannot say. He entered the library late last night by way of the French windows, and I fainted. I knew no more until I found Doctor Long bending over me a few minutes ago."

Disbelief was plainly written on the inspector's harsh features.

"Are you aware, your ladyship, that I found several shreds of the dead man's necktie clutched in your hand?" he said sharply. "Also that the dagger which caused his death belongs to you—your paper-knife, in fact! It's impossible that the wound was self-inflicted. You say this man entered last night. It is quite obvious, then, that you were present when he died, as you were found beside him this morning! If only to clear yourself, your ladyship must tell the exact truth. Who is this man, and for what purpose did he come here?"

The cold denunciation in his voice broke down the last barrier of Lady Hartley's endurance, and she clung tearfully to Lillah, who sought to comfort her.

"Lady Hartley," said Blake quietly, though he was blazing at Mulberry's brutality, "you are not compelled to make any statement to this man. What you have to say I advise you to withhold until the inquest. Inspector Mulberry is grossly exceeding his duty!"

"Thank you, Mr. Blake—I will take your advice," Lady Hartley said.

Mulberry closed his book with a vicious snap and turned to the doctor, after a fierce glare at Blake.

"I'd like you to step along to the library, doctor," he said. "I must find out the correct time the man met his death."

To the relief of everyone present they left the room, and Blake turned to her ladyship.

"You will be wise to go to your room, Lady Hartley. No useful purpose will be served by your presence, and you are plainly unfit to be worried," he said, and the quiet sympathy in his voice brought a look of gratitude into the dark, tear-brimmed eyes.

"I will, Mr. Blake. But, oh, please do not let them question me further. I cannot tell them more, and it would be useless," she said tremulously. "I—I will wait until the inquest. And you will help me, won't you, Mr. Blake? You won't let them say that terrible thing was done by me?"

"I will do my best, Lady Hartley," Blake said gently, and leaning heavily on Lillah's arm, her ladyship left the room.

Jim Currier turned to the detective, his face flushed with anger.

"Mulberry's a fool!" he said savagely. "You don't believe her guilty, do you Blake? He's forging a chain of evidence against her that, although circumstantial, is going to prove damning if we are not careful. Take up the case, and prove her innocent. She's no more guilty than I am, man. Why—she couldn't do it!"

But Blake's lips were compressed. He had not liked Lady Hartley's strange reticence.

"Rest assured that I shall do my best, Jim," he said. "Although her reluctance to tell all she knows is strange, I am loth to think her guilty." He turned to Tinker. "Ask one of the maids if Miss Hartley has finished attending her mother. I should like to see her for a minute. It is just possible that she may be able to help us!"

Tinker hurried off. Blake dropped into a chair. There was a vein of mystery in the case that appealed to him. That Lady Hartley was no stranger to the dead man was apparent. She was, for some reason, afraid to divulge what she knew concerning his identity, his object in coming to the house, and his death. That would be accounted for were she guilty.

But Blake did not believe she was guilty. Why, then, was she afraid to reveal the truth?

A few moments later Tinker returned, followed by Lillah. Jim crossed over to her, and for some moments she clung to him, overcome by her grief and anxiety.

"You must be brave, darling," Jim said gently. "Mr. Blake has promised to take up the case, and will strive to prove your mothers innocence."