RGL e-Book Cover

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

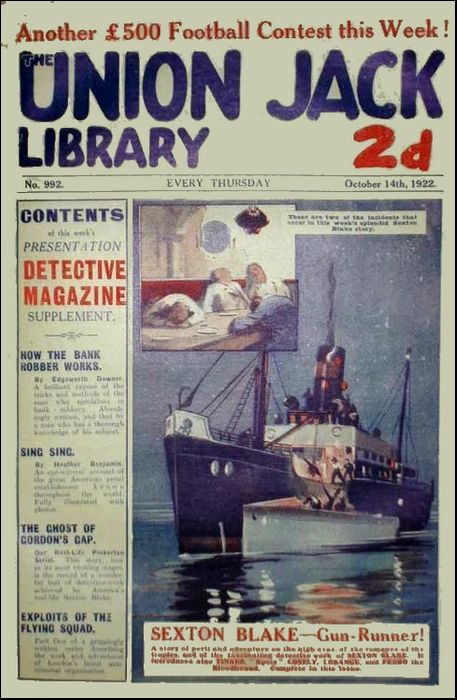

Union Jack, 14 October 1922, with "Sexton Blake - Gun-Runner!"

This week's Sexton Blake yarn is a blend of all the ingredients one finds in a really good detective-adventure story. Incident, action, a straightforward, well-told plot, and withal the splendour and romance of tropic regions. In it appear those old favourites Sir Richard Losely and Lobangu—to say nothing of Tinker and Pedro, Sexton Blake's two indispensable assistants.

At the D'Orsay Club—Sir Richard's Proposition—

Old Times—A Message to Lobangu.

SIR RICHARD LOSELY raised his claret glass to the light and squinted at the colour of it appreciatively.

The D'Orsay Club is small, obscure, and very select. It can provide you with the best dinner in London, or Europe for that matter, and its clarets are famous the wide world over. Sir Richard was connoisseur of clarets and so was Blake.

In fact the dinner had been ordered to suit the claret that was to follow.

Just some fish, plain grilled cutlets, and a simple sort of savoury with some light champagne, and then, in accordance to custom, the tablecloth was whisked away and the claret and almonds and raisins put on the bare dark polished oak.

"Well, what do you think of it, old man?" asked Sir Richard.

"A château wine, of course—a Margeau or Lafitte at a rough guess," said Blake.

"Wrong both ways!" Sir Richard chuckled. "I came across it years ago on a little one-horse vineyard, where they grow white grapes on one side of the valley and purple ones on t'other. I tasted some of it and bought up the whole available stock. I'm on the wine committee here, as you know, and when they'd tried a bottle or two they wanted to give me the D.S.O. Have another glass. We may as well finish the decanter and then we'll get to business."

Tinker, who knew nothing and cared less about clarets, was topping up on almonds and raisins.

"Let's get along to the smoking-room and have our coffee there," said Sir Richard. "The only rule I object to in this pothouse is that you can't smoke in the dining-room."

"Now," he said, as they settled themselves in the deep brown leather armchairs in front of the fire, "are you on for a little fillibustering expedition? If we win through we can make a pot of money; if we don't, we may possibly meet with something in the boiling oil line. They're rather ingenious sort of beggars in the torture department. I believe that they could even teach a Chink some new fashion in that line."

"Humph!" said Blake, knowing a little bit about the methods of the heathen Chinee. "I should doubt it. Look at this, for instance!"

He turned back his cuff and showed a livid scar.

"Sulphuric acid and water drop by drop, and you never knew which the next drop was going to be. I had forty-eight hours of that strapped to a chair, down Limehouse way, until I managed to wriggle the straps under the drops of concentrated sulphuric and bunt 'em. The chair was clamped to the floor, you see.

"Meanwhile, who are 'They'? And what's the general scheme of things?"

"Remember a chap called Gonzalez who did us a good turn once down Bolivia way? To put it more bluntly he saved us from having a taste of the '.' Where they put an iron sort of dog-collar round your neck, and instead of a stud at the back they have a turn-screw arrangement, which bores into your spinal column until something goes snap."

"I remember it quite distinctly," said Blake. "And I also remember with extreme pleasure the fact that I managed to grab a rather obsolete but very useful revolver, and bowled two of the brutes over. I can see the white dust of the roadway flying now.

"They went head over heels like shot rabbits. One of 'em had about a mile of gold lace on his breeches, and the other was plastered so stiff with medals and orders and things, mostly made out of sardine-tins and debased Mexican dollars, that I wondered how a bullet could ever have got through them and do the 'Homocea' act.

"Well, the main point of the whole scheme is that poor old Gonzalez is up a gum-tree and has managed to smuggle through a cable askin' me to help him to get down on to firm land again.

"We owe him a bit, so I'm goin' to do what I can. How he got the cable through, I don't know—possibly by native runners.

"But the point is that he's holed up on one of the island lakes—Titicumca or Piopolo—and is bleating for arms and ammunition.

"He wants rifles and cartridges badly, and a machine-gun or so.

"Revolutions are as common over there as the 'flu is here, and Da Costa, a half-breed Portugee, has made himself the president by the simple process of shooting up pretty well everyone he didn't like the look of and cutting the throats of the others with a 'machete.'

"If I can cart out rifles, and so forth, and possibly a few dozen bombs, to keep the natives amused and busy, I get in return—or, rather, we do, for it's a share-up job—a whole heap of mining concessions.

"Goyaz lies twenty degrees south, as near as no matters, and it's a rich country—one of the richest little countries in the whole bally globe, I should say.

"There is silver, copper, tin, bismuth, and gold—wonderful crops in the 'Yungas,' as they call the broad valleys, and herds of llamas, wild horses and cattle on the 'Majos Llanos,' the higher plains, really a sort of plateau stretching away to the foot-hills of a branch of the Andes.

"I tell you, my dear old bean, that if we pull Gonzalez out of the soup you'll be a miniature Rothschild at the worst, provided always that you are still wearing your own skin.

"There's a chance, of course, that none of us may. The 'Cholos'—half-breed Indian—have funny little ways of depriving you of it.

"Like some of those Eastern Bolshevist animals they've a weakness for tryin' to peel your hide off in lumps and make gloves and gaiters out of them, and they're also specialists in shrunken skulls—or heads, to be more accurate.

"Allee samee pigeon Amazon Indian palaver. They remove the bone structure, fill the skin up with hot sand, and preserve all the features, hair included, indefinitely. A real good specimen will fetch anything up to a hundred pounds sterling, though the finished article is no bigger than the head of a kid's medium-sized doll."

"It doesn't sound what you might call dull," said Blake sniffing. "And, as a matter of fact, I'm in need of a holiday; feeling a bit fagged out. How long is the picnic likely to last?"

Sir Richard shrugged his shoulders.

"No can tell," he said. "You know what those little South American revolutions are. They may go off whizz-bang, and you may get half a dozen specimens of El Presidente in a fortnight, or you may have a guerrilla warfare lasting for months.

"Gonzalez suffers from brains, and is a good soldier, as you know, and he's straight as a die, even if he did start up in business as a smuggler. Da Costa, on the other hand, is an out-an-out wrong 'un—with Indian blood in him. A demon for cruelty and treachery when he has the upper hand, and a whining cur when he is under-dog. Still, he's got a big following of the Cholos, the half-breeds, behind him—birds of a feather, I suppose. He's really half-bred himself, though he doesn't look it.

"Gonzalez has a few of the real Indians and same of the old Spanish families and their retainers at his back. Goyaz was a Spanish colony when the battle of Waterloo was fought, and many of the big landowners and ranchers still stayed on, and their descendants after them."

"Well, if you can't say when the tea-fight is going to end, you can at least tell us what date the invitations are issued for, I suppose, and whether we get there by taxi or bus."

"We take the morning boat-train for Liverpool the day after tomorrow—ten-thirty from Euston. I've got a lot of shopping to do, stores to get and so on. There we take one of the ordinary liners straight through to the canal and Panama. At Panama we charter a tramp. I've already cabled an agent out there to see about it, and you can always pick one up there cheap which will float and waddle along at her nine or ten knots; too slow to compete with the modern freighters, but good enough for coast trade down there.

"The Spaniard's motto is always 'Maņana, Maņana.' and he's never in a hurry, unless there happens to be a bullfight on."

"Tomorrow is also a day, as the Arabs put it." said Blake smiling. "But how about your little packet of—er—contraband. You wouldn't be popular if your luggage was found to consist largely of rifles and machine-guns?"

"Found your aunt! They're not going to be found!" said Sir Richard scornfully. "In the first place, the Customs officials there are not given to worrying themselves much about anything that smells too much like work, unless there is a big bribe or reward attached to it.

'Also all my cases are stencilled in large letters, both in Spanish and plain English, 'agricultural machinery, with care,' and are ostensibly consigned to a big British firm in Paraguay.

"They will not be landed at Panama but transferred direct from the steamer to the tramp, so no duty is payable, and at the worst, a twenty-dollar note will clear up any little hitch in the proceedings. It isn't as if we were taking the things to New York or New Orleans or Tampa, where they are all up on one ear about things, especially since this new liquor smuggling business has been getting in some fine work.

"Once clear of the Canal we can lounge down along the coast with our hands in our pockets, so to speak, and make for La Paz, the port—second turning to the left, and from there up the creeks to Titicumca or Piopolo, whichever Gonzalez has chosen as a place for a rest cure."

Blake chuckled.

"You must have had an awfully disreputable set of ancestors, you know, Spot's, for you're never so pleased with yourself as when you're doing a bit of looting or smuggling."

"I believe they were a teachably bad lot," Sir Richard grinned. "I know that some of 'em were robber barons and things in the good old days, pinching castles and estates and cattle and things when they got the chance, so I suppose that it runs in the blood. Anyway, I'm jolly glad that they did have those little weaknesses, for what they collared they held on to, and saved up a nice little lump for me, which was lucky, because I don't think I'd ever have made an honest penny on my own. My spelling is too off colour for me ever to have got a job as a secretary or a clerk.

"There's a slump in crossing-sweeping since all the new rich have taken to cars, and big game-shootin'—about the only thing I can do decently—don't pay in these days.

"Allan Quatermain and Scions may have made a pile at it, but in these times for every ten pounds you make on the deal you have to spend a hundred. That's why this revolutionary stunt appeals to me, quite apart from helping old Gonzalez.

"I've get large paws. I take an outsize in gloves, they tell me, and whilst the other johnnies are enjoyin' themselves stabbin' each other and cuttin' each other's throats, my paws can scrape up a few unconsidered trifles out of the mess, and gather in the shekels."

Blake looked at him in mock alarm.

"You haven't become a Jew since I saw you last, have you?" he said. "So far as I know, your last addresses were Losely Hall; Arlington Street; half a dozen expensive clubs, and a shoot in Scotland, the name of which I can't pronounce, much less spell. If you've sold those and removed to Petticoat Lane for a change of air, well say so."

"Have a drink, and don't be a blithering ass," said Sir Richard. "We leave Euston at 10.30 a.m., the day after tomorrow, if that suits you. I know you both keep a stack of bags ready packed, and anything else you want in the way of local kit you can buy over there."

"That suits all right," said Blake. "I've got one or two things to see to, important papers to stow away, and so forth, but I can manage that in a few hours. I've a couple of unfinished cases, but I'll turn over my notes and observations to Ferguson of the C.I.D., and he can finish up the show on his own. If he can't, the men deserve to get off."

"Good man!" said Sir Richard, and reached for a foreign cable form and a pencil.

He scribbled a few lines, and rang the bell. "Have that sent off at once," he said to the waiter. "It's very urgent!"

"Did you give her my love?" asked Tinker, grinning.

"Her? What on earth are you getting at?

"That cable was to old Lobangu, tellin' him to meet us at Panama. I'd already wired him to stand by, but couldn't fix anything definite until I'd seen you two first.

"I've sent it via Cape Coast Castle, and they'll forward it on by runner and lokali. "He'll catch one of the Amazon line boats which call at Colon, and go on to Panama, and meet us there. He should be several days ahead of us, but I've told him to look out for us at the Palazzio Hotel, and given him the address of the agent.

"Now I vote we look in at a show of some sort, and then have a bit of supper at your rooms.

"I'm diggin' out here for the night. I don't want to share a hammock with Tinker and Pedro, and tomorrow we've got to get busy."

Tinker Turns Cook—A Successful Meal—Collecting the Armoury—

Mr. John Fletcher—"Tomorrow We'll be Off!"

TINKER as a cook was not, as a rule, an unqualified success.

He was too experimental, always apparently in search of new ideas.

For instance, he would cook a steak which, at times, was still recognisable as a steak after he was through with it, but more often resembled a slab of charcoal which had got into the fire by mistake.

But even then, if the meat still resembled meat at all, it was pretty safe betting to lay ten to one that he'd get mixed up between paraffin oil and the real olive oil of Lucca in his efforts to produce a particularly dirty sauce or salad. The best people don't use paraffin in cooking, at least, not as a flavouring, though they may use it in an oil-heater.

Tinker was much more likely to fill the stove with expensive, imported oil of Lucca, in the stove where it wouldn't burn, and put paraffin on the steak, where it would with a particularly ghastly smell.

The only person who really appreciated Tinker's efforts was Pedro.

Pedro, being a dog of healthy appetite, and with no real objection to paraffin, knew that it was long odds that when Tinker waded in to cook, wearing a very concentrated and impressive frown, the dinner would eventually become his—Pedro's—for no one else would have touched it with a barge-pole.

Like all other rules, however, this one of Tinker's had exceptions.

At marrow-bones, devilled bones, and welsh rarebits, you could have searched the Savoy, the Carlton, and the Ritz to find his equal—always provided that someone stood by to see that he kept his hands clean, and didn't go near the darkroom, for he had an absent-minded way of strolling off there in the midst of his cooking to see how some negative or other was getting on.

If so, your number was up, for the cooking would taste of anything from hypo to hydrokinone, or dilute sulphuric acid to stale pyro-developer, which, after all, looks very much like Worcester sauce, especially if it's kept in an old sauce bottle with Messrs Lea & Perrin's label still clinging to it, and Tinker collected all the old bottles he could find for his photographic and evil-smelling mixtures.

They put in an hour or so at a revue, and then went on to Baker Street for a bite of supper.

"Get busy and rummage round, Tinker," said Blake. "See what you can find in the cupboard or in the larder downstairs; our worthy landlady will have gone to bed before this. Hurry up, Spots has got a pain in his hunger."

Tinker vanished to ransack the larder down below, and Blake hunted in the sideboard for drinkables and glasses and syphons.

In a few minutes Tinker returned triumphant with a tray.

"Devilled turkey's legs, welsh rarebit, and some hard-boiled eggs which I can stuff with sardines or anchovies, or some old thing!" he said.

"Good man!" said Sir Richard. "Get busy!"

Tinker set down the tray, and headed for the fire.

"Oh, no, you don't, my son!" said Blake, pointing to the bath-room. "In you go and wash your paws first, and in the meantime I'll take the precaution of locking the darkroom door, and pocketing the key, at any rate, till supper's over.

"I happen to know that you've got a new supply of potassium cyanide in there, which you are quite chump enough to use instead of salt, and as neither Spots nor I want to be found tied up in knots on the floor in the morning, or take the leading part at a Coroner's inquest, that door remains locked until supper's over.

"If you wish to try experiments afterwards, you can try 'em on yourself, and if it proves a complete success, as it should, because you've got enough stuff there to poison twenty people, it will keep you out of any more mischief in future."

As a matter of fact, the supper was a distinct success, and Tinker excelled himself. Afterwards they sat up till late discussing plans and studying maps. Sir Richard didn't even go back to his club to sleep, for Blake had recently taken over an extra spare room in connection with one of his cases where he had wanted to keep a client under his own personal protection and observation, a course which had undoubtedly prevented the man from being murdered.

"You'll be all right there, old man!" he said to Sir Richard. "I can fix you up for the night, and you won't even hear Tinker snoring, and in the morning we can phone to your club to have your kit sent on in a taxi."

The next day was a busy one for all concerned.

Sir Richard was off as soon as he had swallowed his breakfast to see to the stores and equipment, of which they had drawn up a carefully considered list the night before. Also, he had to negotiate delicately over the matter of the machine-guns, and satisfy himself as to their safe packing and stencilling.

You cannot walk into a shop and buy a couple of quick-firing modern machine-guns as you would a pair of gloves or a brace of handkerchiefs or ties.

People are apt to get suspicious, and ask rude questions, even after they have asked you double the proper price. One doesn't use, say, a Lewis gun for potting rabbits, as a rule; it would be unkind to the rabbits.

Also it is quite on the cards that the moment your back is turned, and you have paid your money, they will telephone the glad news to Scotland Yard, and inquisitive gentlemen from the C.I.D. will take curiously active interest in all your movements, your ancestors, how many times you have had the measles, and so forth and so on.

They have this complaint—not the measles—but acute "curiosities" just at present, because, though your name may be Andrew McPherson McKillicudeigh, they'll suspect you of being a Sinn Feiner in disguise with a pocket full of debased German marks.

Sir Richard, however, had foreseen all this; also he knew the ropes, and had an official pull, so rifles, machine-guns, and ammunition had been forthcoming, and duly labelled up as someone's new patent tractor-plough in sections, deliverable to a highly respectable firm in Paraguay.

Blake for his part was equally busy.

First of all, he had to go through his notes and papers. All those not of great and immediate importance he destroyed, and destroyed thoroughly. A carelessly-burnt piece of paper or sheet of notes simply chucked on to the fire is, to an expert, nearly as easy to read as if you had left it open on the table or your desk. The main difference is that it requires delicate and careful handling, and that the writing shows up as a silvery white on a black background, instead of black on white—a little fact which many a criminal has found out to his cost too late.

Blake, knowing this fact well, burnt the papers thoroughly, stamped them into small fragments with the heel of his shoe, and then shovelled more coal on the fire.

Then he packed all the really important documents into a despatch-case, with a double patent lock. The initials stamped on the case bore no sort of resemblance to his own "S.B."

They were, in fact, "J.F.," in bold, block letters. The despatch-case he took to a small branch bank near by, at which he kept a small emergency account, in case unforeseen circumstances made it inadvisable to go near his own regular bank at any time. He was known at the smaller establishment as Mr. John Fletcher, and was popularly supposed to be something in the writing line—an historian who liked to leave valuable documents, and so forth, in their care when he went away.

Blake did not undeceive them. Their version of the story suited him as well as another.

He saw his despatch-case safely installed in the vaults, drew a cheque for a few pounds, chatted to the manager for a minute or two, and went off.

The reason for all this was that on no less than three occasions his rooms had been broken into and ransacked during his absence, and other attempts had been made.

So the small branch bank came in handy. No one there knew his real identity. He never went to it by a direct route. And he knew that no real professional criminal would go out of his way to ask for trouble by attempting to break into a bank vault, and a small branch bank at that.

Occasionally a messenger's bag, or wallet, or a bundle of notes might be snatched from the counter, and possibly a revolver might be loosed off at random in the hopes of terrorising the staff; but that was a very different thing from making an attempt on a vault, where, possibly, there might be only a few pounds, the bulk of the money having been transferred to one of the main offices.

From the bank he made his way to New Scotland Yard, and spent some time discussing matters with one or two high officials. Then he made his way to the club for luncheon, on the chance of Sir Richard turning up.

Tinker, meanwhile, had been left to do the packing, see to their rifles and revolvers, and generally tidy things up, including himself and Pedro.

Blake had finished his frugal cutlet, and was just starting on biscuits and cheese—a paper propped up in front of him—when Sir Richard was shown in.

"Everything fixed up," he said. "Order me some grub; anything will do. I'm as hungry as a wolf! I've had a wireless from old Lobangu. I suppose he got the steward or someone to write it out for him. He's on board the SS. Atora, which sails about mid-day as they reckon it there, so he ought to be well on the high seas by now.

"Here's a cable from Maralla's, the agents, at Panama. They say that they've got me a tramp—the SS. Branca, and a cheap charter at that. She's supposed to do eleven knots, which, I suppose, means, really, nine if someone sits on the safety-valve. Still, that will do us, so long as she floats the right way up and all her seams filled in with paint and putty.

"Hallo! What's this stuff? Cold game-pie? Just the very thing to stoke-up on! And I think that, to do justice to the occasion, you'd better buy me a bottle of nice dry bubbly, to wash it down with.

"All our gear, except personal stuff, goes on to-night's mail, to save time. I've fixed it all up. To-night we'll paint little old London a nice bright vermilion. Theatre—and suppers and things are on me. Tomorrow we'll be off!"

"His Royal Highness!"—And a Little Bubbly-Water—An Unrehearsed Comedy—

Lobangu Explains—Sir Richard Gets a Bill—So Does Lobangu.

OUTWARD bound to the canal and Panama, the voyagers spent an uneventful time.

The ship was well found and comfortable, the food good of its kind, and the weather surprisingly so for the time of year.

There was the usual polyglot crowd on board—Spaniards, Portuguese, island planters, and a sprinkling of officials.

They had a set of cabins and a small sitting-room to themselves, and Pedro, who managed to find his sea-legs quicker than usual, sprawled about the deck and made friends.

Owing to the alterations being made, the passage through the canal itself was slow and the heat grilling; but they had windscreens rigged to the ports to catch such breezes as there were.

It was just getting on towards dusk when they reached harbour, and dropped anchor, and almost as soon as the gangway was down a small boat shot alongside, with three men rowing, and a fourth in faultless white duck, large straw hat, and a crimson cummerbund, seated in the stern-sheets, smoking a cheroot.

A moment or two later a steward showed him into the small saloon.

"His Excellency Sir Richard Losely?" he asked, looking from Blake to Sir Richard and back again.

"That's me all the time," said Sir Richard.

"A thousand pardons, seņor, I am Juan Maralla, of Maralla & Co., the shipping-agents whom you honoured with your esteemed commands. There lies the Branca, yonder! I hope you will find her in every way satisfactory. I took the liberty of having a coat of paint given to her and her engines thoroughly seen to. She is not fast no; but, then, she is only a little ship compared with this big liner!"

They looked, and saw a bluff-bowed stumpy, but sturdy little tramp, with her riding-lights burning brightly, about a couple of cable lengths away.

She was painted the cream-white of the tropics, and looked comfortable enough.

"She has coal ballast," said Maralla, "plenty good water, and her condenser; also an ice machine. Tomorrow early she shall be brought alongside, and your baggage and stores put on board. I myself will see to it. The steamer here, she does not leave till noon, because of the mails."

"So I've just heard." said Sir Richard. "Now. I think we'll just have a cocktail, and trot up to the Palazzio for a bit of dinner. Perhaps you'll come with us, Seņor Maralla?"

"A thousand thanks, Excellency—a cocktail with pleasure, but dinner I am desolated I must refuse! Mail days are busy days with us. I know our reputation for saying 'Maņana'—tomorrow—but, alas! with mail days here it is not tomorrow, nor the next day, but next week. But speaking of the Palazzio remembers me that there is a friend of yours awaiting you there—three, four days.

"A very large man—so: of dark complexion. Twice he has called at the office to inquire for you. A very big man—and thirsty! Never have I seen a man drink so many bottles of the wine of Champagne with the gold foil round the neck. If the canal from Colon to Panama were only of champagne, instead of water, I believe he would have drunk it all, and we poor shippers would all have been ruin!" He laughed with a flash of white teeth.

"Lobangu," said Sir Richard, "has evidently been on an unmitigated bust, and hopes that I shall foot the bill—which I sha'n't!

"I hope to goodness he hasn't smashed all the furniture or killed someone!"

"Buenas noches, seņores!" said Maralla, setting down his glass. "A los pies da usted. Till tomorrow!" And he bowed himself out.

Twenty minutes later the others were passing through the scent-laden palm-gardens of the hotel towards the terrace.

There was a brilliant tropical moon, a band of guitars and mandolins were playing soft Spanish dances at the far end, and sealed in solitary grandeur under an electric light was a large figure dressed in white ducks which met where they touched.

A loud pop and the sound of liquid bubbling into a glass announced the fact that the figure was indulging in a little liquid refreshment.

"By the process of logical deduction and the use of the faculty of observation, I should be inclined to bet you five bob," said Blake, "that that is the one and only Lobangu—and the said Lobangu is very thirsty!"

"Nothin' doin'!" grinned Sir Richard. "I tell you what I will do though. I'll bet you a level half-crown that if he finishes that bottle which he has just opened he'll bust that duck suit of his all to ribbons!

"It's only hanging on to him by a stray button here and there now. When it does carry away it will go with a loud bang! Set Pedro at him, Tinker!"

Tinker loosened Pedro with a grin, and Pedro, having sighted Lobangu, went up the shallow steps with a bound. A second bound lauded him fair and square on Lobangu's tummy.

Now it must be remembered that for comfort's sake Lobangu was lying asprawl in a big canework lounge-chair; these are very cool, and also very light. The table beside him was also very light, and of wicker, but on it was a heavy silver tray, glasses, and bottles of champagne—one empty, the other three parts full—an ice-bowl, and other paraphernalia. Consequently, when about half a ton of Pedro landed on him, Lobangu said "Ouch!"

It was all he had either time or breath to say before he went over backwards, chair, Pedro, and all. As he went he made a frantic grab at the table to save himself, and merely succeeded in taking it along with him.

The heavy silver salver went down with a crash and a clang, which it repeated as it rolled down the steps. Glasses, bottles, and ice-pail came down crash, and Pedro made ghastly and terrible noises which were intended to be a joy howl, but which really sounded more like the wailing of a banshee mixed up with a fog-siren; and Blake, Sir Richard, and Tinker let up a whoop of delight.

The orchestra at the far end of the veranda immediately stopped, turned round, and glared fiercely, evidently considering that this was some rival show—a new type of jazz-band come along to cut into their legitimate profits.

Moreover, the hotel manager, an excitable little Frenchman, followed by three or four waiters.

"Thousand thunders! What is it you do?" he said, shaking his fist at Sir Richard and the others. "What is it you do to his Royal Highness, a friend of Sir Losely's, the great English milord, for whom his Highness waits here?"

"We weren't doing anything," said Blake, as soon as he could get his breath. "As a matter of fact, we just brought along his—er—Royal Highness' little lap-dog to see him, and the poor little thing was so overjoyed that, in the exuberance of its spirits, it—er—rather upset things!"

Pedro, who had managed to get his nose in contact with the foaming cascade of champagne, and tried incautiously to sniff it up, had a violent sneezing fit, the recoil from which nearly swept the manager off his feet.

"This," continued Blake, "is Sir Richard Losely himself, and we are friends of his. We've just come off the mail-steamer."

"A thousand pardons, Excellency!" said the manager. "But in the midst of a turmoil so terrible I—"

"Oh, that's all right. But we are hungry, and want a good dinner for four. Let us have a corner table. and the best dinner you can manage. I leave all the details to you. By the way, there's a silver salver belonging to you down amongst those palmettos there. It rolled down the steps when his—er—Royal Highness was upset!"

"All shall be as your Excellency desires. I myself will attend to the dinner. It shall be served in a quarter of the hour." And he bustled off, leaving a couple of waiters to clear up the mess and retrieve the salver.

"Well your Royal Highness," said Sir Richard, "a nice exhibition you've made of yourself. What you want is a nursemaid to look after you!"

"Wow! Inkoos," said Lobangu, tenderly picking bits of broken glass out of himself, "it was not I. It was that clumsy great fool the King of Beasts! You cannot do much when a young elephant rushes in out of the darkness and jumps on your stomach, especially when you are sitting on one of these bagati chairs!"

And he gave the harmless chair a vicious kick.

"For three days and more I have been sitting here, with no one to speak to, Lukuna, for I know no one here; and every day—sometimes twice a day—I went down to the office of the man who mounts herd over the ships as the small boys of the Etbaia herd the cattle in the plains. But he could tell me little or nothing of where you were, though there was one of the little boxes which clicked in his room, just as there was in the Residency.

"But you had sent me a book to await your coming. Lukuna, and I waited and grew homesick.

"There was not even one to fight. A sharp, quick fight would have been a change, and done me good. And one night three men met me amongst the paints yonder with long knives, which they carried hidden down the leg of their trousers—not strapped to the calf of the leg in the proper way.

"I turned on them with my spear. One stayed to throw a badly-aimed knife, and then they ran.

"Wow! But they could run no better than lame dogs, so I beat them with the flat of my spear till they howled like women; then I took away their knives, and beat them till they could run no more.

"Two of the knives I threw away into a small stream, where there was much mud.

"The third I kept, for it was a good weapon of good steel, with picture-writings on it, some done in gold.

"The next morning men in uniform came, and would have tried to take me prisoner, until I showed them my broad stabbing-spear and told them that I would treat them as I had treated the others.

"Then the Frenchman who owns this kraal came out and told them who I was, and that I was a friend of certain great English lords, and they also went away, saying no other words of prison, which here they call 'cárcel,' and I was very lonely. So I took some of the bubbly-water, and felt better inside. And, oh, on that night I dreamed a dream, and in front of the dream was a red mist like a veil before my eyes, and, as thou knowest, Untwana, such a veil only comes to me at certain seasons, when there is fighting to be done!

"So I polished up my spear and drank more of the bubbly-water, and felt still better. For I knew that in the end you would come—also M'lolo and Untwana here."

"Well, we've come all right," said Sir Richard. "But you go an' have a wash and brush-up, tuppence, and for the sake of decency, man, pick out the rest of those glass splinters and put on a respectable suit and a collar! Grub will be ready in a minute. Hurry up, or you won't get any!

"Here, wait a minute! Who was it, by the way, who made you a Royal Highness? A Serene Highness I could have stuck, at a pinch—the woods are full of 'em, especially the Hun woods, where they grow as thick as blackberries, and as sour as unripe ones—but a Royal Highness is different. Who gave you that handle to your name?"

Lobangu looked coy—at least, he did his best to do so.

"In truth, Lukuna," he said, "since no one else would do it, I gave the title to myself. Was I not a friend of yours, and milord Untwana and M'lolo? It was in your honour that I did what I did. Also, at Vera Cruz I bought many beautiful ribbons, and orders which glisten like stars, and real medals. I believe, in truth, that they are such as the Portuguese wear on high festivals, and some have real stones in them which glitter most splendidly. Also a new uniform of scarlet-and-gold, and a long sword."

"Then why aren't you wearing 'em?"

"To speak truly, Lukuna, the uniform of scarlet-and-gold wouldn't have gone round me by the space of two handbreadths at least. It might have fitted M'lolo there, who is grinning like an ape in the forest, but me, though I went without food, it would not fit until I made the Portuguese thief of a trader put in more of the scarlet cloth, and even then the stiff collar choked me till I could neither eat nor drink nor take snuff. Also, the long sword, though it had a beautiful, shining colour of silver, proved to be bewitched—a 'tagati' thing which twined itself about my legs—and twice it tripped me up so that I fell on my nose.

"The second time my nose hit some hard stone steps, and the whole world seemed full of stars. Even now it is tender here, as though someone had hit it with a knobkerry.

"Still, it had its uses, for the little man who shrugs his shoulders and spreads his hands—so—gave me the best rooms in the plac, especially when I said that I was waiting for my lord Lukuna.

"There was nothing that his servants would not do for me, and all that I asked for was brought to me quickly."

"Oh, was it?" said Sir Richard dryly. "Well, the next thing you're goin' to ask for, you old ruffian, is your bill, and you'll Jolly well pay it yourself, or we'll leave you behind, to get home as quickly as you can, or they'll chuck you into the 'cárcel,' the 'jug,' the local prison, or whatever you like to call it, and keep you there, and all you'll get will be 'tortillas,' which are dry, tasteless little things made of flour, and some probably muddy water to drink.

"Now go and make yourself fit to be seen. If you're not, no dinner do you get at all!"

"N'kose!" said Lobangu, rather crestfallen, and vanished to the royal suite assigned to him.

"The old saying," observed Blake, "used to be, 'Vanity, thy name is woman,' but I think that old ruffian could give the best of 'em half the course and a beating! He's as fond of dressing up as any kid at a children's party!

"Hallo! Here comes our worthy host to say that grub's ready! Let's get a move on. We'll just have a vermouth, and then wade in. I'm not going to wait for his Royal Bumpiness, even if he has got a sore nose!" Now, as a matter of fact, Lobangu was no fool—or, at any rate, he was clever enough to realise when he had made a fool of himself—and he also had a good deal of natural personal dignity when he was not on the spree.

He came in a few minutes later in a neat blue suit, one of those be had purchased from Sir Richard's own tailor on his last visit to London, and, barring the fact that he would wear his row of quite unauthorised medal-ribbons, and the highly polished gum-ring in his hair—which, after all, he could not help—he looked quite distinguished. For he had a strong strain of pure Arab blood in his veins—nothing whatever of the negroid—and his skin was lighter than, say, any ordinary Matabele.

Many a swarthy Spaniard would have looked dark by comparison.

The manager had evidently spread himself in the matter of dinner for his so distinguished guests. Being a Frenchman and not a native, there was not a suspicion of a thing stewed in rancid oil in the menu, and where he had used garlic he had used it with the hand of an artist, not a bricklayer. Also, he had chosen the wines himself. They had the big room pretty much to themselves, most of the other people having already finished dinner and gone of to concerts and theatres.

"Inkoos—Untwana—what palaver is this?"

"War palaver," said Blake, —"some big-sized sort of war palaver. You remember El Seņor Gonzalez, of Goyaz?"

"Yes, Untwana. A great man, though not so high as my shoulder, but a great fighter. A man who fights with his head as much as with the rifle or spear, and often have I thought that but for his head we might well have come nigh losing ours."

"That's a fact!" said Blake. "Well, Don Gonzalez is in a bad way. There has been a revolution, and a half-breed called Da Costa, backed by a lot of Cholos, his own half-breed relations, have turned out top dog for the moment, and boxed Gonzalez up on one of the islands. He managed to get a message through asking for help, and, above all, arms and ammunition.

"Lukuna has a small steamer of his own, and also guns and chatter-guns.

"Tomorrow we sail for Lapaz, the only port on the Goyaz shore of any importance; and then, after we've joined with Gonzalez, we'll do our best to mop up Da Costa one time."

"That is good talk, Untwana. Tell me more, and let us think out a plan.

"I would that I had but one regiment of my young men here—those who are armed with the rifles which speak quickly—and we would stamp this Da Costa and his mongrels flat.

"Wow! It would be a great game, and we would go through them as a spear goes through a bowl of curdled milk!"

"Don't be a fathead!" said Blake. "It's taken us all our time to smuggle through a few rifles, cartridges, and machine-guns—in fact, we haven't got 'em clear through yet. Do you think that they'd have let your crowd through? Why, one of your picked regiments at full strength, and with supplies, would have wanted a couple of young transports at least! That would never have done. Listen whilst I explain—"

Sir Richard rose, yawned, and looked at Tinker, who caught his eye and took the hint.

"We'll leave you two to discuss matters," said Losely, "and leave you two to argue it out. We're goin' to take Pedro for a stroll. We'll have to be back on board in half an hour or so, or we shall be unpopular. Time's getting on."

"What's the game?" asked Tinker, as soon as they had left the veranda.

"I'm going round to find the manager's office on the quiet, and give old Lobangu the scare of his life!"

They found it after some little searching—a comfortably furnished, well-lighted room, looking on to the gardens and an orange grove.

Mons. Jules, the manager-proprietor, was taking a well-earned rest from his labours in a deep cane chair, enjoying the cool night breeze blowing inward from the sea by an open window. He had taken off his coat, was smoking a thin black cheroot, and there was a glass of sweet, strawberry-coloured "sirop" at his elbow.

Sir Richard stepped in.

"We are going back to the steamer," he said. "I should like my bill, and also that of his Highness. I should prefer to settle them now as I may not have time to come in the morning."

Mons. Jules, all alacrity at once, went to his desk and produced the two accounts. His own was moderate enough, but Lobangu's made him raise his eyebrows and grin as he passed it over to Tinker.

Lobangu, in the course of his three and a half days' stay, had managed to run up a bill of the equivalent of fifty-five pounds and some odd shillings.

"Pretty steep—eh?" said Sir Richard. Mons. Jules raised protesting hands.

"But, name of a dog, Excellency, consider what his Highness would have—nothing but the best rooms—the Royal Suite, as we call it. The best champagne of France in our cellars."

Sir Richard grinned.

"I see he seems to have averaged about half a dozen bottles a day and a few other trifles."

"But yes, Excellency—and eat! Mon Dieu! he eat soup or sweet or savoury, terrapin or expensive. He do not seem to care whether he eat soup or sweet or savoury, terrapin or Pęche Melba. If he like a dish, he eat it three or four times; if it not please him, he throw it, plate and all, at the head of waiter. He break more things in three days than all the hotel in three year.

"Ah, he is a droll, his Highness—an eccentric—is it not so?

"One day he give me a gold cigarette-case, and a gramophone the next; he not feel well in the head maybe; he have eaten sixteen seventeen courses for dinner.

"Then, pouf! I come to wish him the good-morning, and he smack me on the ear! Oh, lā, lā!

"I have been kick by a mule of Mexico. I would rather be kick so three time than smack on the ear once. He have a good heart, Excellency, but his head, I think it is soft—or mebbe he is in love!"

Tinker giggled, and Sir Richard hacked him on the shin to keep him quiet, though he himself was grinning inwardly at the idea of Lobangu "in lov."

"Well, look here, Mons. Jules," he said, producing a big bundle of notes. "I want to settle both these bills now—but on one condition."

"And that, Excellency—"

"That condition is that tomorrow morning you present to his Highness another bill, not a mere paltry one like this for fifty-five pounds; make it out for a hundred or a hundred and twenty at least. Pile it up. Put in everything you can think of; treble the number of bottles of champagne that he had; charge him for that silver salver—tell him it was lost in the palmettos. Double your prices; do anything you like, and add my dinner-bill of this evening to it. By the way, have you got any really good Havana cigars? 'Ramonez,' or some brand like that will do—the best and most expensive you've got. I'll have five hundred of them.

"I'll pay you now, but they must go down on the bill."

"Yes, Excellency," said Mons. Jules, rubbing his ear and looking depressed. "But—"

"But what?"

"If it please, your Excellency, if I present to his Highness a bill so enormous, he will—how do you phrase it?—'knock off my block,' is it not? He is of a very terrible temper when he is roused, and with that big spear of his! Oh, lā, lā!"

Sir Richard grinned.

"You will tell him that it is by my order. Here, give me a sheet of paper and a pencil."

He scrawled on it:

"You will pay this bill and look pleasant. If you don't, and I hear any complaints from Mons. Jules when you come on board, I will chuck you overside, and you can swim home. "Pay or stay. —R. L."

Tinker read the words and chuckled. "There you are," said Sir Richard, passing the note over. "That's an order which be daren't disobey. Pin that on to the bill when you give it him, and say that I told you to do so. He'll pay up like a lamb then. He's got plenty of money."

"But, Excellency, even so, what am I to do with the money, then? I cannot take it, for you have already paid me."

"Oh, put it in your safe, and keep it till I come back again.

"I'll take those cigars now, by the way. Tinker, you carry them. We must pick up Blacky and be off: it's getting late."

They collected Blake and the cigars. "You're to be on board at nine sharp," said Sir Richard to Lobangu, who looked disconsolate, and there they left him.

On the way back to the ship Sir Richard burst into a roar of laughter once or twice, and Tinker chortled.

"What on earth are you making those fool noises for?" asked Blake.

"Wait till you see that old ruffian Lobangu in the morning. He'll explain," said Sir Richard. "Oh, yes; he'll be chock full of explanations.

The Scandinavian Captain—Lobangu Arrives—

The Captain's Grievance—"You Can Count On Me!"

NEXT morning saw the party early on deck—so early, in fact, that the sun was only just clearing the horizon line, but, even so, they had scarcely finished their breakfast on deck when Juan Maralla joined them.

"I have sent the boat on with a message to the Branca, seņores," he said. "See, already they are getting the warps out to bring her alongside, and in an hour, at the most, all your baggage and the heavy machinery you spoke of should be aboard, and can be struck below, and stowed later, according as you desire. Then we will make a little tour of inspection to see if all is to your satisfaction; and so bon voyage, and a happy return!"

Slowly the Branca was warped alongside and made fast fore and aft. She looked ridiculously small in comparison to the big liner, but she seemed to be a stout, sea-going boat, and had been made spick and span under Maralla's directions.

"That," said the latter, pointing to a man in white ducks standing aft, "is her captain—Captain Wolf. He knows the coast routes well, having travelled up and down them for many years. He is half an Englishman, half Scandinavian by birth, but he speaks Spanish, Portuguese, and several native coast dialects fluently."

They looked down at the man who was giving orders. He was lean almost to emaciation, a melancholy-looking individual, with a skin burnt yellow-brown by many years in the tropics, and he had evidently had repeated doses of fever. He had thin, straggly, iron-grey hair, and a small grey tuft of beard and large, dark, tired-looking eyes. In age he might have been verging on sixty as he stood there smoking a thin black cigar, but his appearance was deceptive, as they were soon to learn.

A rope fouled a stay, and in a flash he had sprung forward and cleared it. The tired-looking eyes blazed with anger, and a hard and hairy fist shot out and floored the bungler. As it did so, Blake for one noticed a bulge in the pocket from which that fist had been drawn so swiftly, and it was evident that beside the fist the pocket had contained a fairly heavy revolver of sorts.

Then he turned loose on the bunglers with a most vitriolic tongue, and swore at them volubly and fluently in about half a dozen languages at once.

"He may be a bit long in the tooth," said Sir Richard dryly, "but he can move about as quickly as greased lightning, and the way he bowled over that big chap was a treat."

"Shall we go down, seņor?" said Maralla. Sir Richard nodded.

A rope ladder was slung overside, and they scrambled down. The captain recognised Maralla and nodded, then seeing the others and guessing them to be his future owners, he threw away his cigar and saluted stiffly. "We are just going to have a look round, captain," said Maralla. "And meanwhile you'd better set your men to getting the cargo aboard as soon as possible."

A red-headed, and unmistakable Patlander, with a dirty face and a broad grin, was fiddling about with the donkey-engine, which was giving out a kind of spasmodic grunt every now and then, whilst a little flickering wisp of steam came from the Branca's solitary funnel.

"'Tis full power we have now, sorr," he said.

"Very well, then. Get those hatches off, some of you yellow trash, and stand by the derricks."

Maralla led them off to the companionway. The saloon was surprisingly spacious, and had been put in order, and there were six fair-sized state-rooms opening off it, three on each side, whilst at the for'ard end there was small bath-room, pantry, and galley, in fact, she had far more room than anyone would have guessed from a casual glance at her from outside, and Sir Richard said so.

"Si, seņor," Maralla explained. "But when the faster boats began to carry the bulk of the freights and prices dropped down, the owners had this part transformed so that she could carry a few passengers up and down the coast, as it paid better. She has two good holds, apart from her coal-bunkers and engine-room. The captain's own cabin is underneath the bridge, and there is plenty of space for'ard for the crew."

Just then the captain came down. "They've started in on your heavy stuff, sir," he said. "They'll have it all on deck in about half an hour or so, and we can see to the stowage of it afterwards. The incoming mailboat has just been signalled, and we shall have to sheer off before she gets in. So before that you'd better have all your light stuff and personal baggage sent down; you'd like that stowed here, aft, of course?"

"That's the idea!" said Sir Richard. "Tinker, you cut up and bring back a couple of bottles or so; there are glasses in the pantry, and we'll drink success to our voyage. You'll join us, of course, captain? By the way, what sort of a crew have you got?"

"Rotten!" said the captain. "As rotten and hazy a lot of yellow monkeys as I ever came across. There's not one of 'em but wouldn't like to stick a knife in my back if they got the chance. That's why I carry this little toy"—and he patted his pocket. "They're the scum of the earth, and the only way to get 'em to work is to drive 'em and haze 'em. If you didn't, they'd go to sleep standing on their flat feet and dream of a new way of murdering you. They're as mean and treacherous a sackful of scoundrels as you can well imagine.

"The red-headed donkey-driver, Micky, is a man. He's white all through. I call him Micky because I don't know his other name, and for the matter of that, I don't think he does either. And there's a nigger cook who isn't a bad sort, and who can cook, which is something. But the rest—well, they ought to be given rat poison. Mind you, it isn't my fault, sir. I had to put up with what I could get.

"The big ships snatch up all the men worth having these days, and there's a lot of shore work going on too along the Canal, where they can get a job and stick it for two days a week and lie about and scratch themselves the other five. Besides, my orders from Mr. Maralla, there were to get a crew one-time 'pronto,' so I had to do the best I could. Mind you, they can work when they want to, and I've had worse men in the engine-room than I've got now."

"That's all right, skipper," said Sir Richard. "Ah, here comes Tinker with the needful, and—Great Scott!"

This remark was caused by Pedro deftly pushing the door open with his nose and stalking majestically into the saloon.

Captain Wolf turned sharply and saw him, and as by instinct his hand flew towards his pocket, only to be instantly withdrawn.

"I beg your pardon gentlemen," he said apologetically, "but I thought for a moment I was in for another bout of malaria, and had got the fever on me badly. I'm fond of dogs. I had a sort of bob-tailed terrier once myself—nice little chap, but the sharks got him—still, I own up. I'm not used to what you might call outsized dogs.

"I've done a bit of elephant-hunting in my time, up along the creeks, in the back-countries, and upon my soul, for a moment I fancied that I was in the tall grass and saw a bull-elephant pup coming at me. Here, Fido, come and make friends! What sort of dog might you call him, sir?"

"He's a bloodhound."

"Is that so! Well, I shouldn't care to wake up and find him sitting on my chest, and that's a fact!"

"How on earth did he get on board?" asked Sir Richard.

"Flew!" said Tinker gravely. "At least, he came by air. As a matter of fact, the poor old chap was so miserable at being left out of things, shut up in the cabin, that I got one of the steamer's deck-hands to help me sling him down. He hasn't learnt the rope-ladder trick yet."

"Well, here's success to our expedition," said Sir Richard, raising his glass. "And—Great Scott, what's that?"

There was a terrific crash and a bump, and Captain Wolf jumped to his feet ready for war.

"It's one of those yellow monkeys mishandling your cases. I'll go and twist their tails for them. I hope they haven't smashed anything, sir. It sounded to me as if a tackle had carried away."

"Wrong—quite wrong, skipper," said Blake. "It's only a friend of ours coming aboard. I recognise the bump. Don't worry, his head is about as hard as a teak block. If anything is damaged it will be your deck."

Captain Wolf looked astonished, and certainly was still more so, when Lobangu came stalking in, his big spear in one hand and a long strip of paper dangling limply from the other.

He was barefooted, and had reverted to his old duck suit, of which, as Blake had prophesied, several more seams had given way.

Captain Wolf laid a hand on Tinker's arm.

"Excuse me," he whispered. "but are there many more bits of this menagerie to come drifting along? Because me nerves aren't so strong as they were."

"No, that's the lot," grinned Tinker. "Unless you've a private collection of your own."

"I think I'll go and see to things on deck," said Wolf."I want a bit of fresh air." Lobangu, looking very woebegone, stood still and rubbed the back of his head with the hand that held the paper.

"It was his head," said Blake. "I could tell by the sound—wood on wood! Have a drink, old man."

Lobangu shuddered, and for the first and only time in his life refused.

"Nay, Untwana, no bubbly-water for me! See, and you, too, Lukuna. Look at the book that that thief at the hotel has given me!! Also there was another book from Lukuna, saying that I must pay."

Blake and Sir Richard looked, and Tinker peered over their shoulders, and it was as much as any of them could do to keep a straight face.

M. Jules had certainly proved himself to be an artist.

To begin with, the bill was at least a yard and a half long, and not content with the mere paltry hundred or so suggested by Sir Richard, he had managed to make the grand total a hundred and seventy-five pounds odd! Champagne worked out at about three pounds a bottle, and according to the number charged for, Lobangu must have got through roughly one an hour.

There was hardly a dish on the menu that cost less than ten shillings a portion, and damage to waiter's head was placed at two hundred francs!

As it was all made out in French in a thin, spidery hand, the only thing that Lobangu had been able to read were the figures, which were remarkably plain, and the flourishing signature, "Jules Dehouet," across the receipt-stamp at the bottom.

"Look you, Lukuna!" groaned Lobangu. "That little pig of a thief, who had many soldiers round him, said that if I didn't pay he would keep all my beautiful clothes, and then have me put in prison till I died!

"I saw red, and I wanted to fight, but my head was very sore, and things inside it kept going round!

"Also, there was the book you had given him, I paid him, and had my things brought down here to the big ship, where they told me you were here on this little one; so I came down a ladder of rope, which was most assuredly tagati, twisting round and round in my hands like a snake. Then something slipped, and something else very hard hit me on the back of the head, and I saw many stars! And now I am here I think I will lie down and sleep until my insides no longer walk about!"

"About the best thing you could do," said Sir Richard unsympathetically. "Tinker, you'd better cut along and see about all our small gear and any little things Lobangu has left lying about. Get a couple of the steamer hands to help you. We shall have to clear out of here one time, or we shall have the incoming mailboat barging into us.

"If you happen to see Maralla on board—he left here some little time ago—tell him I'll try and wire him any news from somewhere farther down the coast. Look slippy!"

In about twenty minutes Tinker came back loaded with gun-cases and odds and ends.

"All the rest of the stuff is on board," he said, "just by the companionway hatch. We'll have to get it down bit by bit. I gave Maralla your message, and the skipper is just casting off the warps. He says we can stow things and make everything shipshape as we go along.

"He's coming to ask what you want done when we're clear of the traffic and he can trust the wheel to the donkeyman."

"Right." said Sir Richard. "We'll get busy."

The three of them—Lobangu being still on the sick list—got to work with a will transferring all the light stuff into the spare cabin aft, such as their own rifles, cartridge-cases, medicine-chest, binoculars, cameras, mapmaking instruments, and clothes and so forth; also cases of tinned foods and other odds and ends. And they were kept busy till close on luncheon-time, and the Branca was beginning to nose her way into the outer swells of the Pacific.

There was a stiffish breeze blowing once they had made an offing, and the Branca proved herself, as they had expected, a good sea boat, if not exactly a greyhound. She would dip into an oncoming roller as if she was aiming to have a look at what was underneath it, and come up smiling and give herself a bit of a shake, sending off the spray from her bows in a scintillating diamond-like shower on either side, but with her decks bone-dry.

A grinning black face peered through the galley door, from which came a most appetising smell.

"Luncheon he lib, sah!" said the face.

"Right-ho, Sambo!" said Tinker. My tummy he lib for luncheon. You get 'um ready one time."

"My name no Sambo, sah—my name Mistah White."

"Cheerio!" said Tinker. "White it is, what's in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

"Carry on, sergeant-major! Let's have the grub, and plenty of it. Lay for four, and send and let the captain know when it's ready."

"Yes, sah!" said the grinning face, and bobbed back again amidst an aroma of curry and fried banana.

In five minutes luncheon was laid on a spotless white cloth; and it was a luncheon that many a restaurant ashore could not have bettered.

"Some lunch!" said Sir Richard. "I expected to live on sea-pie and hash, with a change over to hash and sea-pie, with an occasional dog-biscuit and a stray weevil or two by way of a savoury. White, you are an artist! Have you sent to tell the captain?"

"Sho', sah! De cap him comin' right along—"

Captain Wolf came in looking rather straight down his nose and with a grim look on his face. However, he was tired and hungry; he had been desperately hard at work for many hours, and wolfed his meal in silence.

Blake could see that the man was feeling pretty bitter about things, also that the knuckles of his left hand had been bleeding pretty badly, and there was more blood on his coat which, apparently, was not his own.

When he had gulped down his food he drummed on the table for a bit, and stared at the skylight as though trying to collect his thoughts. Then he spoke abruptly and to the point.

"Gentlemen." he said, "I've been hearing things. and I want to get to the bottom of this funny business before I go any farther! I know I've no right to butt in, but there are just a whole heap of things I'd like to know about this trip which I don't understand.

"No, don't interrupt, please! Let me have my say, and after that you can speak, or not, as you like. But I'm responsible for this old tub and for those on board her so long as she is in my charge, and it seems to me, from what I've heard when wasn't supposed to be within ear-reach—except over a long-distance telephone—that some of my crew know a darn sight more of what's going on than I do!

"Point Number One. —I was given to understand that our destination was way down South, and that some of those big heavy cases on deck, containing tractor-ploughs, end so on, labelled 'Agricultural machinery,' were to be consigned to the big British firm whose name is stencilled on them in large letters.

"Point Number Two. —I understand from what I've overheard by the back-talk amongst the hands, that there isn't so much as a spade or a trowel in those cases, let alone a plough, but that they are chock-full of rifles and machine-guns, and that the smaller cases contain cartridges and hand-bombs. Which seem to me to spell war.

"Point Number Three. —That our destination is no farther south than the port of La Paz, in Goyaz, twenty degrees south, as near as no matter, and that they are intended for el Seņor Gonzalez.

"Point Number Four. —My crew know all this, somehow; may be some of them are spies of Da Costa, the half-breed, who is aiming to wipe Gonzalez out. There's been heavy fighting going on there for this three months past, that I do know.

"Point Number Five. —Why wasn't I put wise to this when other people were, as it seems? I'll play any man any game he likes, so long as it's a square game with the cards on the table, but I play with no man who has a fifth ace in the leg of his boot, that's flat!"

Blake looked at Sir Richard, and Sir Richard whistled.

"What about White?" he said, and jerked his thumb towards the galley.

"Don't you worry about White!" said Captain Wolf, a trifle acidly. "He's sailed with me off and on this last ten years, and he's a sure good nigger! He and Micky, who acts as mate when be isn't busy with the donkey-engine, are the only two to be trusted. I tell you frankly that, if I'd known what sort of racket this was going to be, I'd never have gone into it with a crew like this!"

"Look here, skipper," said Blake. "I quite see that you think you've got a grievance, and so you have; but we've got the same complaint ourselves, in a way.

"Of course, we meant to take you into our confidence later on—we should have had to; but we thought that the closer we kept our mouths shut whilst we were in touch with shore the better. The officials at Panama are pretty easy-going in their way, but even they might have got up on one ear about trying to pass through 'arms of precision,' and all the rest of it; so we kept our tongues between our teeth as long as we could. That's only common-sense, isn't it?"

"That's right enough, sir. I see your point of view."

"Well, we thought that we'd succeeded on the agricultural implement stunt, but, from what you tell us, we haven't—we've failed! How, I know no more than you do at present. When I do find out I'm going to make it just as unpleasant as I can for someone!

"Now as to the other point. To have had our clearance-papers made out to La Paz, Goyaz would have been about as sensible as to send a typewritten paragraph or so to all the local rags, telling 'em exactly what we really did mean to do. We had to put 'em off the scent, and declare for Juarez or Fernando, where the cases were marked for.

"Lastly, we owe el Seņor Gonzalez a big-sized debt. He saved our lives, and now we're going to try and save his, and run him back into the Presidential chair.

"Mind you, this is our own private show. We don't want you to run any risk. You run us and the guns and ammunition up to Titicumca or Piopolo, and as soon as we can locate Gonzalez and deliver the goods and join up with him, you scoot for the open sea again, and hang about for us. We'll manage to get a signal or a message of sorts through to you, somehow. If things go wrong; take this old tub back again, and you'll be none the worse off; if they go right, well, I can assure you you won't be sorry. Sir Richard will see to that.

"Now you've got all the cards in front of you, so smooth your fur, have a cigar and some nose-paint, and we'll hope for the best!"

Captain Wolf flushed.

"I thank you, sir! No offence, but I had to get it off my chest, and now I'll have my little say. I know something of el Seņor Gonzalez, and I've heard quite enough of Da Costa to make me sick! If I'd got a dirty pair of heavy sea-boots on, it would give me a great deal of pleasure to kick the seat of his trousers through his waistcoat, and then go and clean those same boots afterwards.

"I'm no quitter when I know where I stand, and if I've a weakness it is for a scrap. I suppose I've been scrapping most of my life, except when I've been down with fever, and I've had to fight that pretty hard at times, so I hope you'll count me in on this deal. I know those half-breed Cholos and their nasty ways, and if I can help rid the earth of a few of 'em, it would be a real pleasure to me—a sort of holiday, you might call it. Meanwhile, I'd like to make a suggestion or two, if I may."

"Fire ahead, skipper!" said Sir Richard.

"Well, sir, as I told you, I don't trust this crew one inch, barring the donkeyman and the nigger. If you take my advice, you'll have all those cases struck into the afterhold here, where they can't be tampered with, and all the spare coal and odds and ends shifted forward."

"You'd better come and bunk here yourself," said Sir Richard; "there's tons of spare cabin room."

Wolf shook his head.

"No, sir. I'll bunk for'ard in my own den under the bridge. I've got a brace of guns, and I can keep a close eye on the beasts if they try any of their monkey-tricks! I dare say some of them are 'heeled' themselves; but, even so, I reckon I could shoot twice to their once.

"The one thing to look out for is their knives. They're not apt to be much use with a gun unless they've got the business end of it within a yard or so of your waistcoat buttons; but nearly every man of them could pin the ace of hearts to the mast plumb centre at twenty paces with a knife. They can throw either overhand or underhand with a spin—so! And if you bet on a miss you'd lose money every time!

"I've seen a man caught in the throat at a good thirty yards just a saloon down Callao way that was—at least; when I say I saw it, I saw the result. The rest was too quick to follow, though it was blazing sunlight.

"The man with the knife, though he had nothing in his hand a second before—I can swear to that—drew his arm backwards level with his hip, and jerked it forward and outward; and the next thing I saw was the other fellow go down, all sprawling, in the hot, white sand, with the haft of the knife sticking out under his chin.

"I pulled it out, whilst a pal of mine wasted lead on the man who threw it. It had a six-inch blade, and a weighted handle nicely balanced. The dead man was carrying a gun, too, but he hadn't even a chance to reach for it.

"That's what you want to watch out for, especially at nights. But, mark you, I don't think they'll give any considerable trouble until we're a good deal further south, and, anyway, somewhere near the Goyaz coast and within reach of Da Costa. It would be giving the show away.

"Now, gentlemen, we've had our palaver, and know how we stand. Count me in. Remember that. And if there is trouble you can count on the donkeyman and the nigger, who is sure to have a razor in his pants somewhere.

"By the way, can any of you take a trick at the wheel? She's dead easy to steer, and, though she may be a slow old tub, she answers sweetly to her helm. You see, if there is trouble, there's only me and Micky to take watch and watch about. The compass; for a wonder, is accurate."

That's all right, skipper," said Sir Richard. "We can all take our trick, need be, so long as you've got good charts and we don't have to make too close a land-fall amongst shoals and currents we know nothing about."

"That's good hearing, sir! Now, I'll get that stuff of yours struck down into the afterhold, and haze the beggars a bit to let them know who's who. If one of you could relieve Micky for a spell in, say, a couple of hours' time to let him have a 'caulk,' then he and I can carry on through the night."

"Tell him I'll relieve him in half an hour," said Blake. "By the way, has he got a gun? And, if he has, could he use one?"

"I've seen him drop a bird on the wing with one, sir, but he isn't wearing one now. He mislaid it, he said. But I happen to know that where he mislaid it was on a pony race, where he put it up against two bad Mexican dollars on a dead cert, and the dead cert was mostly dead from that tired feeling before it had got half-way round the course."

"Very well. Tell him in half an hour, then. And when he comes aft, Sir Richard will find him a gun and a gargle."

Southward Ho!—A Dastardly Plan—The Knock-out—

The Poisoned Knife—Da Costa's Spy—A Lesson for the Crew.

FOR the next few days they rolled their way, lazily down south, and outwardly, at any rate, nothing of any importance happened.

They ran into a squall or two, but the Branca proved herself a good, dry, seaworthy boat. She might dip down into the hollow between two waves until only the trucks of her stumpy masts were visible, but she always turned up smiling again with little or no water running out of her clippers.

Off La Mancha she ran into the tail-end of a heavy westerly gale, and they rigged up try-sails to steady her, as she was rolling a lot, being light. After that she ran into it patch of calm—so calm that the sea was like a lake, and she reeled off her reputed eleven knots and a trifle over.

With the wind dropped pretty well to zero, the heat became oppressive, and between them they managed to rig up some sort of an awning over the after-deck out of some old canvas. It was not much to look at as a piece of artistic work, but it kept off the blazing glare of the sun, and they lounged about there in deckchairs and pyjamas, whilst Mr. White fed them with long cool drinks of lime-juice-and-soda and angostura.

They each took a trick at the wheel in turn, so the work was light.

Lobangu and Pedro had both recovered their sea-legs and their appetites, which were enormous, and Micky took his donkey's breakfast from the fo'c'sle, and bunked out in the charthouse.

Now and again, as opportunity served, they ran in and lay-to off one of the small ports whilst a boat was sent ashore to buy fruit and fresh vegetables, and sometimes fresh meat.

But all this was on the surface—the calm that comes before the storm. All the after guard knew that, under this apparent peace and quietness, they were really living on top of a seething volcano.

There was nothing definite to go by. The crew worked fairly well. There was really very little for them to do except down below in the engine-room. It would have been far better for them if there had; and no one knowing this better than Wolf, he set them to work scrubbing paintwork, polishing brass, and all the odd jobs he could think of. But even so, they still had plenty of time to idle about and smoke endless black cigarettes, and chatter amongst themselves in low tones. Also, they were suspiciously civil—the too obsequious civility which is accompanied by an ugly gleam in the eye—for all the world like a mongrel dog who comes crawling up to you, yet has his fangs ready to snap on the slightest chance.

And then, like the flicker of lightning out of a summer sky which heralds a thunderstorm, two little incidents, trifling enough in themselves, happened in quick succession.

It was a clear, starlight night, and Blake was taking his trick at the wheel, the others all being below. Pedro, who had found the cabin too hot, in spite of the open skylights, was dozing, sprawled under the lee-rail for'ard. Blake could just make him out as he lay in the shadow of the rail, and from the fo'c'sle hatch came the soft thrumming of a guitar.

Presently he became aware of a second shadow which was gradually and noiselessly making its way towards Pedro. It was a man, and he held something in his hand.

Pedro, normally of the most friendly disposition, let the man pat him, and rose leisurely to his feet. The man offered him what he held, and Pedro sniffed at it and backed away.

Again the man tried to tempt him, and again Pedro backed.

Blake had recognised the man by this time as Luiz, a beetle-browed ruffian with a scar on his cheek. He also realised that things were not all as they seemed.

Swift and noiseless as a cat in his bare feet, he left the wheel to look after itself and leapt forward.

So noiseless was he that he took the man completely unawares, and gripped his wrist.

"What have you got there?" he asked.

"Not'ing, seņor; only a leetle bit of my suppaire, which I wish to give to de beeg dog in case he be hongraie, mebbe."

"The big dog is not hungry, nor does he accept food from strangers. I think," he added slowly, "that you had better finish your suppaire yourself!"

Luiz tried to wrench his arm free.

"You letta me go!"

"No, my friend," said Blake. "We've an old saying about 'trying it on the dog first,' but, like nearly all proverbs, they can be twisted round. Pedro can go without, and you shall eat!"

As he spoke, he brought the edge of his right-hand palm sharply down on the muscles of the man's tense upper arm. Properly done, the blow, though quite a light one, can cause excruciating pain.

The man gave a sharp yelp, and his muscles relaxed as though a sharp electric current had been shot through them and switched off again.

Slowly and remorselessly Blake forced the hand backwards and upwards until the lump of meat was within an inch of the man's mouth.

He wriggled and struggled, and managed to relax his fingers sufficiently to drop what they held, and at the same time slid his left arm behind him, groping for the knife at his belt.

He was at a disadvantage, because, sailor fashion, he carried his knife on his right hip; still, even so. he might have been able to reach it, for he was as sinuous as an eel.

Blake knew it, and knew the danger of a quick, upward stab.

He swung the man half-round on his feet, and drove in a terrific upper-cut to the jaw. He heard the teeth click—the man's mouth had been half-open at the time—and something went crack as the man went limp, and went down on to the deck-planks with a thud.

It was clean a knock-out as anyone would want to see.

"That will keep you quiet for another few minutes, my friend!" said Blake to himself, and ran back to lash the wheel, having taken a squint at the compass.

Then he returned to find his man still unconscious, and breathing stertorously.

He picked up the meat, tasted it with the tip of a moistened finger, and spat vigorously overside.

There was a faintly bitter, salty taste to it, suggestive of arsenic or strychnine, but not quite resembling either, and South-American poisons are numerous—all deadly; and few are to be found in even the most recent of modern works on toxicology.

He threw the meat overboard, and without ceremony searched his man thoroughly, rolling him over this way and that to get at his various pockets, having first deprived him of his knife, an ugly-looking double-edged affair with a ribbed handle.

He was going to throw it overboard, when, in feeling along the soft belt from which it was slung, he discovered a little unevenness which might be worth inspecting. So he detached knife, belt, and sheath, and all, and slipped them inside his pyjama coat. Whilst Pedro came sniffing round to see what the trouble was.

He found nothing else of any importance, though he searched the fellow to the skin, and he wasn't over-gentle in his methods, either.

In fact, he rolled him about so much that at last Luiz opened his eyes with a grunt, and staggered up on to his knees, to see Blake standing over him and watching his every movement.

He glared at him, and spat some blood out of his mouth, for the jolt he had received had cost him several teeth.

"Some day Ah keel you for this!" he said. "I swear Ah keel you for dat blow!"

"Opportunity is a fine thing," said Blake coolly. "I shouldn't boast too much. I hate dirtying my hands with yellow half-breed trash like you. Next time you give any trouble, I'll use a gun. Now, get for'ard, unless you want to have another dose.

"Go on, man—quick! Or else I'll take you by the scruff of the neck and chuck you down the fo'c'sle ladder! A skunk who would try to poison a dog who has done him no harm is worse than a snake!

"Some day you may have to meet that dog when you haven't got a knife or a bit of poison about you. If you do, I warn you you'll get your throat torn out before you can yell for help. He's got a long memory; he knows your scent. Heaven help you if you try to touch him again!"

Luiz staggered and lurched his way forward, and Blake followed him noiselessly a couple of paces behind, with Pedro beside him.