RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

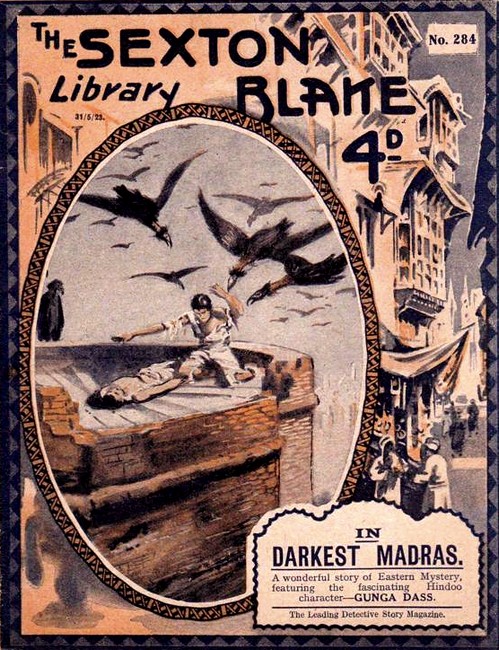

The Sexton Blake Library, May 1923, with

"In Darkest Madras"

A wonderful story of Eastern Mystery, featuring

the fascinating Hindoo character—

Gunga Dass.

Soothsayer—The Magic of Gunga Dass—Blake Accepts the Challenge.

"AND now, Tinker, I propose we spend the rest of the evening in Black Town and endeavour to see a little of real, naked India. This is our last night in the country for some time. To-morrow we return to England, for our task here is finished."

The eldest of the two Europeans, seated on the balcony of a fashionable Madras hotel, turned smilingly to his companion, a snub-nosed, freckled youth, whose only claim to beauty lay in a pair of twinkling blue eyes and an open and good-humoured countenance.

"Anything for a change, guv'nor," said the lad. "I'm getting a bit sick of European Madras. It isn't as Eastern as the East India Dock Road in dear old London. The bands here play the latest two-steps, the cinemas show the latest films, and our servants speak English a darned sight better than I can. Show me India without European clothes—stripped and naked!"

Sexton Blake smiled and glanced at the view before them. Flanking the sweeping esplanade of the sea-front were Government offices, European residences, and noble colleges, richly carved and gargoyled, and although robbed of their pristine freshness by time and its minion, the weather, they were smoothed into a rugged, weather-stained beauty pleasing to the eye.

To the left of Fort St. George a strip of golden sand stretched down into the sail-studded and moonlit waters of the Indian Ocean.

Fashionably attired men and women paraded the sea-front, and from the opera house came the sweet strains of an orchestra playing the prelude to Sullivan's "Iolanthe." It was hard to believe that not far from them was naked India, with its superstitions, intrigues, mysteries, and weird, occult knowledge handed down from generation to generation, for north of the fort lay Black Town, a far-reaching mass of stench-laden, tumble-down buildings, the native quarter of the city.

Sexton Blake and his assistant had been engaged upon a diplomatic mission on behalf of the India Office. Blake's tact and discretion had averted what might easily have become a serious menace to the British Raj, and on the morrow he and Tinker were to return to London, their task concluded, much to the relief of those Ministers in Westminster whose thankless under-taking it is to guard our interests in India.

"You'll see naked India all right in that four-mile square of brown iniquity yonder," Blake said. "Black Town harbours half the coloured crooks in the world. The night haunts of 'Frisco and the Montmarte are Band of Hope meetings in comparison. You'll see some Indian magic, too, my son. My advice to you is to watch it and then banish it from your mind. The occult sciences of the brown man cannot be fathomed by the European mind, and to attempt to probe beneath the surface of things Oriental is to flounder deeper into the mire."

Tinker nodded seriously.

"You're right, guv'nor. I've read a good bit about the 'phenomena' brought about by those fakir chaps, and, as you know, witnessed a few of their tricks— tricks that are inexplicable, like the one in which they cause a horseless gharry to go tearing over the ground at twenty miles an hour, and which have baffled the best brains in the world."

"Sheer trickery, of course. young 'un," Blake said. "The mystery of it all lies in the fact that the secret of the tricks has never been revealed. None of the fakir kidney have ever divulged the secrets which have been handed down to them through generations of 'magiis' of the long and mysterious Indian past. Many have formed the opinion that it never happens; that the audience are hypnotised by the fakir, and made to see what does not really occur—in short, that the fakir wills them to see the thing done, and that the audience imagine they do see it. But it seems thin to assume that one of those travelling holy men can hypnotise so many people, leaving not one to detect the fraud—if fraud it be."

"And yet Gunga Dass has penetrated their secrets."

Tinker spoke in a low voice and his eyes took on a peculiar expression as they turned in the direction of Black Town. It may have been the chill of the night breeze blowing across the Indian Ocean which caused the lad to shiver as though in the clasp of an icy hand.

Or could it have been the memory of a brown face and two dark eyes of hate—of a vow taken on the steps of the shrine of Kali, goddess of the devotees of Thuggee, a criminal gang he had helped his master to crush, a vow taken by Gunga Dass to destroy them Sexton Blake and he, as destroys the tiger, mercilessly, fighting with tooth and claw?

"Gunga Dass, wizard of Eastern intrigue and mystery, is as inexplicable as the Orient itself," Blake said gravely.

"It's strange the Indian police haven't laid him by the heels yet."

Blake smiled grimly.

"The man is as elusive as the wind," he said. "A master of the art of disguise, with a deep knowledge of the occult sciences of the Orient to aid him, as subtle as a snake and more dangerous in his sting, Gunga Dass can protect his liberty against the police of the world. Iron bars cannot hold him—twice he has escaped from a condemned cell—and in India, among three hundred million of his own race, to search for him would be a sheer waste of time and energy."

"But you will not give up your task?"

Blake's lips tightened, and he shook his head.

"I have also taken a vow, Tinker, and although not sworn on the shrine steps of some outlandish goddess, it is as sacred to me as Dass's own, I have vowed to bring Gunga Dass to justice, and to that end shall my life's work be devoted. But until he reveals his hand, breaks out in some daring coup, I am helpless.

'It has been three months since the swords were last unsheathed, since Dass pitted his wits against mine, and although the Hindoo managed to escape me, I then succeeded in bringing disaster upon his plans, and wrested the spoils from him at the eleventh hour.

"The man must by now be short of funds, and I am hoping that in the near future he will attempt some criminal enterprise. I should recognise his handiwork instantly, and it is possible when that time comes that he will leave some clue behind which will put me on his trail."

A silence fell between them, and the shadows did not leave the alertly thoughtful eyes of Tinker. He knew that between the brown man of India and his beloved master was a feud which would go down with them to the grave. Master-crook of the Orient, cunning and subtle as a snake, with a deep knowledge of those mystic, immutable forces of darkest India to make him doubly dangerous, Gunga Dass had many times in the past crossed swords with that great London detective Sexton Blake,

And in each of those grimly fought duels Blake, armed by his brilliant powers of deduction, as was Dass with the occult weapons of the mystic East, had found a foeman worthy of his steel.

It was a little over three months ago since Dass, by employing the occult weapon, had broken out of the condemned cell in a London prison. Since then the Hindoo had engaged himself in audacious coups, blazing a trail of crime across half the civilised world, a case in point being his nefarious attempt to gain possession of the mummified remains of the child of Parvati, a venerated Indian goddess, and thus claim the great reward offered by those of Parvati caste for the return of the great symbol of their faith.

In that exciting bid for a great fortune, Sexton Blake had again pitted his wits against the cunning Oriental, and succeeded in bringing his most carefully laid schemes to disaster, although at the eleventh hour Dass had managed to escape from him.

A mysterious flitting figure, clothing his real identity beneath a score of pseudo ones, the Indian police had been powerless to follow up the man's trail and bring him to justice. Gunga Dass was once more at large, lurking unseen somewhere in the great continent of India, obsessed with a consuming desire for vengeance against the man and boy who were the only stumbling blocks in a criminal career.

So occupied were the two detectives with thoughts of the past that neither noticed the tall figure of a shabby Hindoo who stood half concealed in the shadow of a doorway opposite the hotel balcony. The native was typical of his class—calculating and cunning of features, with the dark, piercing eyes of the hypnotist.

A striking, picturesque figure to the Western eye, he was unobtrusive of appearance in his own country, and many of similar dress and bearing could be found in the dark bye-ways of Black Town, Madras's hot-bed of intrigue and mystery.

His dark, smouldering eyes flamed with the light of a devil's torch as they were bent upon the figures of the two white men, and his features relaxed into an evil smile. They were wonderful features—handsome, and with the cruel nobility of the eagle in the dark eyes and hooked nose. His black beard and imperial black moustache were thick with white dust from the shizum-lined jungle roads, and the lank black hair, straggling over his powerful shoulders, was matted and uncombed.

An untidily-wound pugree was about his head, and his tall, lithe figure was loosely swathed in the black robes of a soothsayer, tattered and travel-stained. In one hand he carried a stout staff; across his broad back was slung a bundle of bedding, and fastened to this were brass lotahs and cooking pots.

From his sash depended a bag of broken food, and on his muscular arms were brass-studded bangles reaching up to his elbows. Cheap leather sandals encased his feet, and about his ankles were chased amulets of silver.

Suddenly his dark eyes became abnormally bright, and they rested in turn upon Blake and his assistant, as compelling as a magnet. The detective started as the knowledge of those bright eyes intruded upon his senses and glanced sharply from the brilliantly illumined balcony to the shadow of the doorway opposite.

He could see nothing, however, but in the lustrous, dark eyes of the Hindoo had suddenly appeared a brilliancy which seemed to hold the accumulated force of generations of Hindoo magii.

Blake started to his feet. The air seemed charged with an evil and hostile influence.

As he looked he felt, as though it were a keen wind, this influence growing stronger and stronger. He summoned every effort of will-power and tried to throw that malignant influence from him.

"Hypnotism, lad," he gasped. "Keep your eyes from that doorway opposite. Cover your head and face with a handkerchief—anything."

But that sensation of incredible evil grew stronger, as though the forces of the Pit were conspiring against them. And with it something warm, not physically warm, but with a physic warmth that cloyed and enveloped.

"What did you say, guv'nor? Hypnotism—"

The lad's voice trailed off into silence, and to the detective his voice had seemed to come from a great distance. Blake tried to tear his glance away, but some unseen power held it. Tinker shuddered, then grew rigid in his chair. To him it seemed that his brain had suddenly gone dreamy, although in some dim way he was conscious of his surroundings.

The dreams were mere aimless wanderings, but through them all ran a thread of consciousness that he and his master were in some deadly peril. And all the while he was conscious of some shadowy form lurking opposite, and of brilliant, mesmeric orbs which seemed to burn into his soul.

They were shadowy dreams, clouded by a foreboding of evil. The sense of some disaster overhanging them grew more defined. Someone was watching them. He felt sure of it—felt invisible eyes upon him. But what had happened to his brain? With an effort he dragged his eyes away from that fascinating shadow opposite. He glanced about him and shivered.

There was a strange, uncanny feeling in the air, and the knowledge of those watching, unseen eyes bore upon his consciousness until he felt he must scream aloud to break their spell. But what had happened to his tongue? He tried to cry out, to utter the alarm, but strive as he would he could not get the slightest sound past his lips.

A chill breeze swept his head, but the night was now hot and still. Surely the sky was darkening, the gaily coloured lamps twinkling like jewels on the balcony burning less brightly? He glanced upwards. Ah, the stars had died in the heavens! Something akin to stark terror stole insidiously upon him. And what had happened to his master? Sexton Blake lay rigid and still, and the greyness of death was on his features.

With an effort he controlled his shivering limbs. In some dim way he sensed they were in the power of Gunga Dass, master of Eastern mystery, bound by his mesmeric will as securely as though with cords. Those watching, unseen eyes seemed to be burning into his soul, robbing him of individual thought. He sniffed the air. An odour, musty as a house of the dead, was in his nostrils. His gaze was once more drawn to the doorway, and this time the hypnotist held his glance. From the doorway swirled a thin vapour. It grew into a dense cloud, and everywhere was an awful silence. Like a pall of virgin white, it enveloped them in an icy grip, relentless, freezing the marrow in their bones.

Then through the mist loomed a figure. It was the figure of Gunga Dass, brilliant-eyed, with a sardonic smile on his bearded lips. His eyes were so bright that surely they were lit by some internal radiance. He opened his lips, and his voice sounded cracked and far off.

"All hail, O wizard of the West," they heard the mocking voice of Dass saying, whilst their dim vision marked the leering smile. "So once again we meet. Then let it be as the gods decree. You will find the tiger still red of teeth and claw."

A cold sweat broke out on their skins. Dass had spoken now in a voice strangely reminiscent of the tiger's purr, and tiger-like he appeared, standing there in vision, his cruel eyes aflame, his lips drawn tightly across his white teeth.

"Sexton Blake"—the features of the vision suddenly underwent a startling change; they were now calm, even dignified—"I regret the necessity of keeping my vow. But when men cross swords in the battle of life, the defeated pay the penalty. I have now the honour of being the victor. Let me say, before your hearing is gone from you, that the death of such a brave foe will be less to me a joy than a sorrow.

"But the game is played; the gods have decreed; the end has come. Before dawn you must surely die. How, when, what matters since you have but a few short hours to live? At sunrise will the tiger have tired of its prey, and you will go out to tread the path the others have trod—the one end for the enemies of Gunga Dass."

Blake fought desperately for individual thought as a fuller realisation of Dass's weird powers grew upon him. He knew that unless he exerted his will to the utter-most his mind would be impervious to all impressions save those the mesmeriser allowed to enter—his individual soul-life would be suspended at the other's will.

The vision of his arch-enemy grew blurred and indistinct, as, setting his teeth, he strove to rise from his chair. His movements were as stiff as a marionette's, and the effort of the struggle against the mesmeriser's will brought out the sweat on his face. He overcame an impulse to rush forward and grapple with the man. He knew it to be an optical delusion.

For though his mental eyes had been forced to see that form, none was there!

In the struggle for freedom of thought, he awoke from the lethargy which had possessed his brain. Suddenly he was in full possession of his faculties, and the vision vanished completely. But what was that? His keen eyes caught sight of a shadowy form that left the doorway opposite, and vanished into the deeper gloom surrounding the high walls of the colleges.

"Gunga Dass in disguise,' he muttered grimly. "His hypnotic influence was responsible for my vision. It is an old trick of the fakirs. The man has probably had us under observation for days, for he would know of our arrival in India from the passenger list in the 'Madras Times,' and his subtle Oriental mind chose that way in order to show me I am impotent against him. Well, friend Dass, we shall see. I have won the first round, for my will has proved the stronger. Had I not been taken by surprise those confounded eyes of yours would never have taken my wits from me. I will meet cunning with cunning."

He turned and beckoned to one of the hotel servants, a slim Dher, intelligent of features. The man came forward, and bent his sleek head in obeisance.

"I have work for you to do, Mukhtarud," Blake said quickly. "Work which will mean both rupees and annas to you if you use your wits. Follow a tall native garbed as a soothsayer, and come back later and acquaint me of his movements. The man has just made off towards Fort St. George, so it is likely that he is heading for the native quarter. Get on his trail at once."

As the man left the hotel Blake turned his attention to his assistant. The lad's eyes were closed, and as Blake lifted one of the lids he saw that the pupil was set in a stony stare. Quickly he massaged the nerve centres of the temples and at the back of the neck. Soon Tinker opened amazed and startled eyes.

"Did you see him, guv'nor?" he said, glancing about the balcony with a little shiver of apprehension. "Gunga Dass! What does it all mean? It was uncanny. His threat to kill us, too! Do you think he will carry it out?"

A grave shadow fell across the detective's pale and thoughtful countenance, and he gazed from sombre eyes at the direction Dass had taken.

"As Dass has taken a vow to kill us, our duel with him will assuredly be one to the death," he said soberly. "But ere dawn it is possible we shall once more have him under lock and key. I have sent Mukhtarud to shadow him."

"Then you saw him, guv'nor?"

"He was concealed in a doorway opposite, and from there directed his hypnotist influence upon us," Blake said. "To an experienced hypnotist the trick was simple, and is of the same type of phenomena by which the fakirs impress the illiterate natives.

"When I regained my faculties I saw Dass slip from the doorway and make off for the native quarters. I immediately gave Mukhtarud instructions to follow him, and to hurry back to us as soon as possible with any information he might collect. The servant is sharp, and if there is anything to be learnt he will learn it.

"Come, lad, there is work for us to-night. Let us get into a simple native disguise in case we hear anything of importance. As coolies we should be able to pass unnoticed through the night haunts of the city."

"And our journey to England to-morrow, sir?"

"We must cancel it,' Blake said quietly. "Dass has thrown out the challenge and I accept it. Between that scoundrel and I there can never be a truce or quarter."

So the swords were again to be unsheathed. Tinker's pulses leapt at the thoughts, and his face became grim and purposeful beyond his years.

Blake glanced at the lad with a curious expression in his grey eyes for a moment, then said slowly:

"But you, Tinker, must return to England. It is almost condemning you to death to let you remain here. Remember we are now fighting Dass in the brown man's country. We can get little help from the police, and would have to play a lone hand, two against the many thousands of Thugs he could call to his standard."

"And leave you here to perhaps meet your death—alone, without a friend? Not likely, guv'nor! I didn't come out with you from England to desert you in your hour of peril!"

"My boy, you must. It is almost certain death to remain."

"Guv'nor, I won't!"

Tinker's obstinacy angered the detective until he read the misery in the lad's eyes. Tinker meant to live with him or die with him. And the eyes of the man from Baker Street softened.

"Tinker, be reasonable. Your life may depend—"

"And by my leaving you here may condemn you to death," Tinker said. "No; side by side there is a chance to defeat the ends of Gunga Dass. I've been able to get you from his hands before to-day, sir, and it may be that I shall be useful to you again."

Blake's hand went out and clasped that of the lad. He said no word, only that moment one more link was forged in the chain which held this man and lad together.

At the Joy-Shop—The Parsee Youth—Blake's Suspicion—Trapped.

IN their rooms at the hotel, Blake and his assistant lost no time in getting into coolie garb. Tinker was soon smearing his face and body with weak walnut-juice, and his white skin soon took on the unhealthy-looking and sallow tint of the Eurasian. Cunningly pencilled lines about his eyes added a good five years to his appearance, and a close-fitting wig of lank black hair completed a natural-looking transformation.

An ill-fitting suit of not over clean duck, shabby topee, and shapeless, native-made shoes of tan slashed with white buck, lent considerable effect to his clever disguise.

"Excellent, young 'un!" was Blake's comment, as Tinker submitted his disguise for his master's approval. "Now examine my little effort. There must be no flaws, for the eyes of Dass are as sharp as a snake's."

Tinker stared at Blake in amazement. He had been so occupied in attending to the details of his own disguise that he had paid little attention to his master's doings.

"Holy smoke, is it really you, guv'nor?" the lad chuckled. "What's the price of a throat-cut your way? You look the most villainous Dher I've yet set eyes on."

Sexton Blake's disguise was a masterpiece of the mummer's art. His skin had been stained to the hue of burnished copper by the use of walnut-juice, and two tiny strips of gummed silk held up the corners of his eyelids, giving them a pronounced Oriental slant.

On his brow was the painted red caste-mark of the goddess Kali, the Destroyer. A shaggy black beard streaked down his brown face, and greasy, black love-locks hung several inches below a filthy rag of a pugree which was wound about his head.

His clothes would have made a rag-and-bone merchant shudder, and his eyes, black and piercing, an effect obtained by the careful application of belladonna drops, glowed with a lambent fire beneath shaggy black eyebrows.

To the outward eye he was one of the many villainous-looking Thugs which haunt the purlieus of darkest Madras by night.

"Then you think I'll do, young 'un?" Blake said, staining his teeth red with betel nut.

"Do, guv'nor! Why, you've got our crack character actors beaten to a frazzle!"

A knock sounded at the door, and in response to Blake's summons, Mukhtarud, the servant entered. On the threshold he paused, and stared at the two from astonished and startled eyes.

"It's all right, Mukhtarud," Blake said smilingly. "My assistant and I are disguised. Well, did you succeeded in your mission?"

Mukhtarud salaamed. These Feringhees were mad, of course.

"Yes, sahib. I succeeded in shadowing the soothsayer to the joy-shop of Janjir, which lies in the Tamil Bazaar. I found out from one of the waiters that he has been living there for the past week in the name of Baji Rae, and that he describes himself as a wandering pundit. The joy-shop of Janjir is of evil repute, sahib, and if you pay it a visit I advise you to use caution."

"You have done well, Mukhturad," Blake said, pressing a ten-rupee note into the brown palm. "Remember that a still tongue makes a wise head, and may lead to more rupees."

A few minutes later the disguised detectives were walking in the direction of Fort St. George. The tropical moon hung like a great opalescent pearl in a star-spangled sky, and revealed to them their path. Devout worshippers were praying before the gaudy shrines of native saints. and from the city minarets sounded the sonorous notes of the muezzin calling the votaries to prayer.

As they merged into Black Town they found the night life of the city in full swing. Drinking-booths, eating-houses, and garish temples were ablaze with coloured lanterns, robbing the scene of much of its daylight squalor. The narrow streets, heavy with the odours of the Orient, were thronged with a picturesque, voluble crowd.

The centre of the streets were almost blocked with bags of grain, bales of merchandise, tethered bullocks and gharries. The noise of the crowd—of the buying and selling in the bazaar, the curses and execrations of the half-naked bullock drivers—rose in one indescribable din.

They were now in the centre of Black Town. Windowless shops flanked the streets, the sellers squatting on their hams knee-deep in their wares, smoking the eternal "hubble-bubble." Carpets and silks, curios in ivory and metal, illuminated Arabic manuscripts, highly coloured sweet-meats and sherbets—all could be bought in those wonderful bazaars, and the beauty of many of the goods ill-contrasted with the filth and squalor surrounding them.

"Here we are, young 'un," whispered Blake, halting before a café whose brilliant lights fell across the broken pavement.

Drawing aside the reed curtains, Blake and Tinker entered. The joy-shop of Janjir has long held the notorious reputation of being the foulest den in Madras. The café was thronged with a picturesque but dissipated crowd of lower caste Dhers, and on a platform in the centre a crowd of tuwaifs, or dancing-girls, were moving with floating motions, singing the ballads of Persia and Hindustan.

A dusky female, her grease-smeared arms smothered by brass-studded bangles, and with a great silver ring hanging from her squat nose, was dispensing gourds of bhung (native spirits) from a bar at the far end, surrounded by a crowd of swaggering Bengali youths, who had given a knowing cock to their gaudy turbans.

As Blake and Tinker quietly seated themselves at a bamboo table, a greasy-looking waiter, stripped to the waist, hurried to them.

"Amd machhli aur hilsa machbli dena," Blake said gravely, in fluent Hindustani.

"What have you ordered, guv'nor?" Tinker said, as the waiter hurried off. "It sounded pretty poisonous."

"But it will eat all right," Blake assured the lad. "I have ordered a dish of mango-fish and hilsa. As your Hindustani is weak, and has a pronounced Cockney accent, you'd better act the part of a deaf-and-dumb mute. Can you see anything of Dass? Look round unobtrusively."

A glance round the café assured them that Dass—unless, suspecting the possibility of being shadowed, he had adopted a fresh disguise—was not there.

"I will question the waiter," Blake said. "Mukhtarud states that he was sleeping here, so possibly he is in his private room."

When the waiter returned he placed the dishes on the table. A palm-leaf was piled high with Madras rice, and at the side of a number of lead-coloured chupatties were two smoking dishes of mango-fish and hilsa.

"Kitna pice, chhokra?"

"Ake rupee, sahib."

As Blake placed the rupee in the man's hand he saw that the dark eyes were bent on his own with a peculiar expression in their slumbrous depths. The look speedily vanished, though, and the man became suave and smiling.

"Have you any knowledge of one Baji Rao, the holy pundit?" asked Blake, in Hindustani. "I was informed that he was staying here. I have an urgent message for him."

A coolie at the next table, who had overheard the detective's conversation, started violently. and darted a keen glance at the disguised Britisher. Then he smiled, but his smile had nothing of humour in it.

"Baji Rao went out several minutes ago, sahib," said the waiter. "He will be back shortly."

Blake muttered his thanks, but he knew the man was lying. Something in the dark and evil eyes had told him that. The man at the next table got up and came towards him, his aquiline Indian features as expressionless as a bronze image. He was respectably clad in a cotton dhoti, striped native shirt, and pale blue turban. A deftly twisted imperial moustache adorned his upper lip, and on his breast was the brass badge of a Government servant.

"You were asking for Baji Rao, sahib," he said politely, sitting himself at the table. "I have known him for some time, and will point him out to you when he returns. He has gone to the bazaar to do some shopping."

Blake saw nothing suspicious in this, for the better type of native is polite to a degree with strangers. He turned his attention to his food. Tinker was already sampling the rice and the pungent-smelling curried mango-fish, eating it with his fingers in native fashion.

Then the polite young Hindoo stared down at the detective's palms. Blake, looking up, caught the glance, and looking down at his hands, bit his lip with chagrin. He had made a serious blunder in his disguise!

Instead of the palms of his hands being a dirty pink, as are the palms of all Hindoos, they were stained, like the rest of his skin, a deep shade of brown.

He glanced sharply at the stranger, but the lean, hawk-like features held about as much expression as a bronze caste. In that moment Blake felt he wanted to tear that inscrutable mask away and read the thoughts lurking behind.

He turned his attention once more to his food, determined to bluff the affair through. The Dher rested his arm on the table, his brow on his hand, which partly concealed his brilliant dark eyes. From beneath the penthouse of his shading fingers, he stared intently at the disguised face of the detective.

And the eyes of the young Dher had become the glittering, menacing orbs of Gunga Dass. The features of the man against whom he nursed so malignant a hatred had stirred the barbaric depths of the Oriental crook's nature, lashed with fury the wild animal which crouched there.

It was always there, locked up and chained. Sometimes it slept, but its sleep was light and uncertain. It growled and leapt at the bars of the cage sometimes. It dashed against the bars now, as the glittering orbs watched the detective, filled with the dominant desire to kill.

Savage ideas shot through his Eastern brain as the wild animal in him chafed and struggled in the fetters of his iron will. Blake should pay, and pay dearly. And the day of reckoning was at hand. His should be no commonplace revenge.

His hand had unconsciously dropped from his brow as he glared at the detective with these thoughts running riot in his brain, the evil spirit in him waking stronger as he gave it such devilish ideas to prey on. Soon it looked out of his eyes and transformed those brilliant orbs.

The deadly passion and purpose betrayed itself there for an instant in that sinister glare, a red flame beneath the lowering brows.

And at that moment Blake looked up. As for one brief instant he caught that malignant glare, he felt himself to be in danger. But was it a figment of his imagination? The young Dher now smiled courteously. He was at once suave, polite, genial.

"Baji Rao is a long time, sahib. I expect something has delayed him."

Blake nodded curtly, and turned his eyes away. The look which he had noticed, although only for a moment, on the Indian's face, gave him food for serious thought.

That gaze of dark and deadly malignity, the sinister gleam of those brilliant orbs, vaguely reminded him of something he had seen in the past. He turned his head slightly and subjected the hawk-like features to a close but unobtrusive scrutiny. But there was nothing in the inscrutable face to hint at any undercurrent beneath the calm surface.

Then in an unguarded moment Dass lost control of his features. An expression familiar to Blake crossed his face, and in that moment the detective knew the man before him to be Gunga Dass, cleverly disguised.

Before he could make up his mind as to what course to adopt, the door of the café swung open, and a young Parsee youth entered the room. His creamy-white features were sly and cunning, and there was a furtiveness about his eyes seldom seen in one of his caste.

He was attired in the black jacket and striped cashmere trousers beloved of his race, and on his head was the shining helmet of black glazed board worn by his caste, not unlike a bishop's mitre in appearance.

After glancing round the café his eyes came to rest on the disguised features of Gunga Dass. Blake thought he detected something of relief in the youth's expression, as he made his way to their table.

"Ah, Dass," said the youth, in perfect English, "I have been searching the city for you. Our plans have met with a reverse, I—"

"Silence, you fool!"

To Blake's surprise, Dass turned upon the youth in a fury, his dark eyes glittering. The Parsee recoiled, alarmed by the menace of the Hindoo's looks.

"Get out of here,' hissed Dass; and although his voice was low, every word reached the detective's ears. "Sexton Blake and his cursed chota-sahib Tinker sit opposite. Unless you want to end your days in gaol, get out! I will meet you later."

With a startled glance in the direction of Blake and Tinker, the Parsee hurried to the door. Blake betrayed not the slightest interest in the scene he had witnessed, and Tinker's eyes were bent on his plate, although by now he was fully alive to the fact that Gunga Dass sat opposite them.

Who was the Parsee youth, and what connection had one of his high caste with Gunga Dass, outlaw and criminal?

Then the Hindoo's voice, silky, holding the purr of a satisfied tiger, broke across their thoughts.

"You are my prisoners," he said softly. "A clever disguise, Blake sahib, but with one fatal mistake. Ah, I see by the direction your eyes have taken that you understand my meaning. It was your palms which gave me food for suspicion."

Blake threw all pretence aside, and jerked an automatic from his pocket. Dass did not seem to be in the least perturbed as he stared into the blue muzzle.

"Put it away, Blake," he said, with gentle irony. "This is not stage melodrama. I am about to give you a choice. Will you and your assistant come quietly to my room as prisoners, or must I denounce you as disguised police agents before everyone?"

"You talk in riddles, Dass," Blake said. "You are my prisoner. There is a warrant out for your arrest for the murder of Bhur Singh, and extradition papers have been signed by the British Home Secretary. I intend taking you back to England with me to face your charge. Hands up!"

Dass laughed mockingly, and rubbed his hands suavely.

"Quite a pretty little plan, Blake sahib," he said. "But, as it happens, I have other plans. Put that gun away before attention is attracted to us. Do you know what would happen if I were to strip you of your disguise and denounce you as a police spy? Take a look round. This café quite deserves its evil reputation. Half the criminal brains of the Orient are gathered here to-night. They would tear you and your chota-sahib limb from limb. East is East, my dear Blake."

Blake's heart sank within him as he glanced round the café. Already curious eyes were turned in his direction. They were an evil crowd, Thugs and Dacoits for the most part, and he knew that many of them must be in the pay of Gunga Dass, for the Hindoo master-mind seldom worked without a gang to back him up in his nefarious exploits.

Blake turned his glance upon the Hindoo, and said slowly:

"I have played into your hands, Dass, and agree to accompany you to your room, I choose that course not because I fear your cut-throat gang, but because while there is life in me there is still a chance that I shall live to bring you to the gallows. To that end shall my life's work be devoted."

"Bahut aacha, Blake sahib! That was well said," laughed Dass. "You are a brave man."

Sexton Blake, very erect, said slowly:

"Dass, I have no wish to plead for myself. Let me plead for one who is but a mere boy. Let Tinker go free and wreak your will upon me."

"Guv'nor, I don't wish this! Let us—"

Dass raised his hand.

"Free to dog my footsteps! Blake, do you think me mad?"

"He is only a boy."

"But possesses the wits of a man. He knows my secret, knows where I am hiding from justice. Therefore it is his life or mine. There is a door opposite leading to the sleeping quarters. Go through it; I will follow behind."

Tinker glanced at his master from wondering eyes. Was the detective, a fighter to the last ditch, to allow himself to be led like a lamb to the slaughter? It seemed like it. Blake was walking quietly to the door leading to the sleeping quarters, Dass close upon his heels.

Several of the Thugs, obeying the Hindoo's quick and unobtrusive signal, followed closely behind. Tinker felt muscular hands on his shoulders, and he was pushed roughly forward.

The next instant his master acted. The detective paused abruptly in his stride, causing Dass to bump into him from behind. Quick as lightning, Blake's cupped palms caught Dass at the back of his neck, and with a well-known wrestling throw the detective flung the man over his shoulder.

"The lights, Tinker—quick!"

Tinker writhed eel-like from the grip of his captors, and the next moment his automatic spoke. True to its aim sped the bullet, plugging the oil reservoir of the kerosene lamp which illuminated the café. Darkness speedily followed the drip, drip of the oil.

"To the door, Tinker!" yelled Blake, striking out at the shadowy forms closing in on him.

Confusion reigned. Above the din rang out the snarling voice of Dass:

"Guard the door! The Feringhees cannot escape. A thousand rupees for the man who captures them!"

But Blake had by now reached the door. He was bunched with clinging natives, but shook them from him as the wild boar shakes off the dogs that clamber upon his bristly sides.

"This way, Tinker!"

"I can't, guv'nor! The skunks have got me down," came the gasping voice of his assistant. "Get clear while you have the chance. I'm done."

But Blake gritted his teeth and sprang through the darkness in the direction from which Tinker's voice had come. Then began one of those Homeric struggles of one man against fifty.

At one moment covered by clinging adversaries, his arms, legs, and shoulders a hanging mass of brown bodies; at the next, free, desperate, alone in the midst of his foes, his face grim and set, the detective seemed less a man than a giant.

But the end quickly came. A chair, flung through the darkness, caught him on the forehead. Blake lost his balance, swayed, and fell. Ere he could rise he was pinioned by twenty hands. Five minutes later the two detectives were bound hand and foot in one of the rooms at the rear of the café, all the senses knocked from them by cowardly blows.

An Easterner's Vengeance—At the Serai—

The Tower of Silence—A Night of Horror

"THAT will do. Bring me the dhatura." As Dass's voice rang out the two Thugs eased the pressure of the roomals and flung the senseless Britishers to the floor, Dass bent over them. They were still alive, but their pulses were beating with the slowness of approaching death.

One of the Dhers went to a shelf and took down a bottle of dhatura, the deadliest and most remarkable drug known to the medical world. Much has been written about the "dope," of its wonderful properties, yet the secret of its manufacture is kept closely guarded by the fakirs, who use it in that bewildering trick when they allow themselves to be buried under the ground for days at a time, afterwards being dug out in a perfectly healthy, although dazed condition.

Bewildering as this trick may seem, If has often been performed before Western eyes during the fortnightly festival of Holi, held in honour of Krishna, when all sorts of licence and magic are indulged in.

Taking the bottle from the man, Dass forced a little of the sluggish brown fluid between the Britishers' lips. Their laboured breathing ceased entirely, and although the Hindoo held a mirror over their lips, not a trace of moisture appeared on the glass. Next he examined their pulses, but no sign of animation was there. Their bodies grew rigid, and every accepted symptom of death was present in those still figures.

Dass turned from his fell handiwork with a smile of satisfaction on his lips.

"Although my enemies appear to be quite dead, they are as much alive as you and I," he said, addressing one of the men, who appeared to jemadah of the gang. "Although all pulse and heart action is still, the vital properties in their blood live, and will continue to do so for many hours, for it takes a considerable time for the drug to work out of the system."

"May I ask your plans, master?"

Dass looked gloatingly down on the still bodies of the white men for a moment, and looking at his barbarically handsome features, his dark, expressive eyes, it was hard to believe that behind that Eastern beauty lurked so devilish a soul.

"They are to go on the Tower of Silence," he said, and his voice was calm and emotionless.

The gang shuddered and stared out of the glassless window. A great squat tower stood limned in the moonlight to the left of the fort, and above it wheeled a great cloud of vultures, screaming and occasionally flashing downwards, to rise again with human flesh in their voracious beaks.

The Towers of Silence, many of which are scattered throughout India, are the last resting place of those of Parsee faith. The bodies of the dead are deposited in fluted grooves on a grating on the top of the tower, and in a few hours the flesh is devoured by the numerous vultures which inhabit the trees surrounding the edifices, and nothing but the skeleton remains.

This method of interment originates from the veneration the Parsees pay to the elements and their zealous endeavours not to pollute them.

Parsees respect the dead, but consider corpses most unclean. The race, descendants of the old Persian Jews, and one of the greatest and most respected in India, venerate fire too much to allow it to be polluted by burning the dead. Water is almost equally respected, and so is the earth; hence this singular method of interment has been devised.

There is, it has been stated, another reason. Zartasht, one of their most venerated saints, said that rich and poor must meet in death; and this saying has been literally interpreted and carried out by the contrivance of a well which, lying in the centre of the fluted grooves of the tower, is a common receptacle for the dust of the dead.

Sir Jamshidji, who was a powerful man of the race, and other Parsee millionaires were placed, when dead, among the bones of the poor inmates of the Parsee Asylum in Bombay many years ago. The practice still flourishes to-day, and permission to view certain parts of the towers can he obtained by responsible persons from the secretary of the Parsee Panchayat.

And upon those grey towers, to be torn and lacerated by the voracious beaks of the kite vultures, were to lie the dead, yet living, bodies of Sexton Blake and Tinker.

As Dass stood beside his victims, he looked regal, a king among men, but looking into those black orbs, and into the blacker depths of the soul that lay beyond, one could divine something of the desire for vengeance which raged ceaselessly in that pitiless heart like a consuming fire.

"Being dangerous to our plans they must die," Dass said, in a voice which betrayed no emotion at all. "Dress them as poor Parsee travellers and carry them to the Serai. The keeper will find them dead, or apparently so, in the morning; and their bodies will be carried to the towers as soon as the Parsee Panchayat of Madras has been notified."

In less than an hour Blake and Tinker had been disguised as Parsee travellers. Cheap cotton dhoties were wrapped about their legs, and on their heads were placed the glazed, black helmets of the caste, while, after removing all traces of their old disguise, Dass stained their features to the creamy tint of the Persian race.

"Get them in a closed gharry to the serai," Dass said, "and lay them on the niches. Afterwards return here and report. I have other work for you later. Truly is Kali, the Mother Goddess, looking with favour upon her children this night. Soon we shall be wealthy beyond the dreams of avarice, and that thrice cursed Feringhee detective will live no more to thwart our plans."

Carrying out the rigid forms, the gang hailed a gharry, and, after bribing the driver, were soon bowling along the streets to the Serai, or native travellers' rest-house. Passing their victims out of the gharry, the gang carried them through the great entrance gates into a wide, enclosed space, with plenty of accommodation for camels, ekkas, and ponies, and little niches, or rooms, all around for travellers.

Inside all was confusion. Hairy Punjaubi dealers were watering and feeding their ponies, bearded camel-men giving fodder to their screaming, bubbling, discontented animals, and the "purdanashins," women, hidden behind a grass curtain in a far corner, added to the din by much laughing and chattering.

A fire in the centre of the great room provided the only illumination. Hugging the shadows of the walls, the gang carried the two Britishers towards the niches, and laid them side by side, afterwards leaving the place.

It was morning before they were discovered by the watchman, who, his attention arrested by the strange rigidity of their forms, summoned the Serai native hukim, or doctor. After a brief examination the hukim turned to the watchman and said:

"They are undoubtedly dead. See that the secretary of the Parsee Panchayat is advised, for they are of Parsee faith according to their clothes. It is strange they should have died together, man and boy. Suicide perhaps, for they are evidently poor travellers or beggars without a single piece in their pockets. Still, it is of no consequence to us, for they are of an alien faith and race."

As the watchman sped off to the Parsee Panchayat, the hukim, a grizzled old Hindoo, shrugged and turned away. He was a busy man, for there was cholera in the city. Besides, certificates of death are unknown in India, and post-mortems, except for the benefit of medical students, seldom carried out.

And at dusk that night there came to the Serai a distinguished body of Parsees, After the bodies had been examined and life once more pronounced extinct, four "Nasr Salars," or carriers of the dead, slipped on their white gloves and lifted the bodies with silver tongs to a bier.

Behind the bearers walked two bearded men, and about a hundred Parsees, clad-in virgin white, walked a little distance behind the bier, chanting in the soft Persian dialect, and playing stringed instruments, which throbbed and sobbed in a sweet minor key.

When the procession stood outside the Serai the men in white linked their clothes, an act in which there is said to be a mystic meaning. Soon they were moving on towards the grey towers, above which the great kite vultures screamed and wheeled. The faces of the Britishers were uncovered as they lay on the bier, and as they approached the edifice some of the bolder of the carrion-eaters perched themselves on the bamboo poles, screaming and flapping their great wings.

When they reached the tower they passed through a beautiful garden where a short ceremony was held. It was the soft hour of sunset, great bats were flickering to and fro, and the low evening haze lay like a pale blue veil over the land. Came the soft chant of the priest:

"That our brothers, firm believers in the resurrection and the re-assemblage of the atoms, here to be dispersed, shall live in a glorified and incorruptible body. Zorasta's mercy be upon them!"

Then, with impressive solemnity, the hundred men in white withdrew, and the Nasr Salars carried the bodies into the tower. In a stone chamber they were relieved of their burdens by the four men whose appearance defies description. Old and withered, with great tangled beards sweeping their naked and bony chests; with claw-like, tremulous hands, and bright, vulture-like eyes, it seemed impossible they could be of this world.

They were the keepers of the tower, living their lives in its confines, with the grinning skulls and bleached bones on the grating; the screaming vultures and blood-sucking bats as their only companions.

Carrying the bodies with tongs, these nightmare watchers of the dead placed them on the grating, side by side. Their faces, rigid as though set in death, stared up into the star-spangled heavens. Their eyes were mercifully closed to the bleached horrors around them.

Chanting a mournful dirge the bearers left the grating. Immediately, in a black, screaming cloud, the vultures descended, and Gunga Dass, watching from the roof of Janjir's joy-shop smiled his devilish smile.

Feathered Furies—The League of the Roomal— The Mystery Deepens.

IN a few seconds the victims of the Oriental's diabolical vengeance were hidden beneath the screaming fighting carrion-eaters.

Blake stirred a little as one of the cruel, curved beaks, as wicked as a shark's teeth, tore through his thin dhoti and lacerated his thigh.

Then into his dazed and drugged senses intruded a thread of consciousness that he was in some deadly peril. And all the while he was conscious of hovering, feathery shapes, and of luminous, beady eyes that seemed to hold all the concentrated evil of the Orient in their unblinking black depths.

Shadowy dreams possessed his brain, dreams that were mere aimless wanderings of the brain. But in them the nature of the peril which threatened him grew defined. Fleeting glimpses of vague shapes that flitted past him with monstrous flapping wings figured in them, at first obscurely; then the uncertain twilight of dreamland brightened; the dreamer could see what the danger was that threatened him.

Stone walls enclosed him and above him was the star-lit vault of heaven. He was buried beneath gaunt and feathery shapes that pecked and fought over his pain-racked limbs. And what lay about him? Those bleached bones and grinning skulls, the feathered furies fighting over his body—surely the whole were products of some nightmare dream?

In a frenzy of horror he dashed out his arms and gripped one of the birds by the throat. It fought and screamed in his clutch and the talons threatened to lacerate his arms to ribbons. And what was the matter with his limbs? They seemed lifeless and cold, and he was powerless to lift himself.

And as he gripped it seemed that his strong fingers melted and were turned into air. The chill of death was in him. In vain he tried to wrestle—to grapple that gaunt, feathery form. But his hands were as shadows, immaterial, impalpable. In vain he put forth all his strength, but it was the ghost of a grasp, and powerless against the material being.

The talons of the thing bit deeper into his flesh. He struggled in the horrible consciousness that he was nothing, and in the struggle his brain awakened from the lethargy which possessed it, and his limbs obeyed his will.

With a cry of horror, he scrambled to his feet. With raucous screams, the birds descended on his head and shoulders in a cloud, and the monstrous wings, flapping against his face, threatened to beat the senses from him.

He bent down and snatched up one of the bleached bones surrounding him. It was a thigh-bone; and with it he beat the winged furies from him. They fled to turrets of the tower, sinister grey shapes against the velvet blackness of the sky.

Then the horrified gaze of the detective fell upon Tinker. The lad had not yet recovered from the drug which Dass had administered. He ran to his assistant and dragged him to the shelter of the walls, where a projection of the stonework afforded them a little protection, should the vultures, infuriated at the loss of their prey, make another onslaught.

Still dazed from the effects of the drug, the detective glanced about him. He was on a circular grating, in the fluted grooves of which were dozens of skeletons, in various stages of decay. The musty odour of a house of the dead was in his nostrils.

"The Towers of Silence!" he muttered, shuddering in a revulsion of feeling. "Is Dass fiend or man?"

Suddenly a new horror possessed him. That icy coldness, like the chill of death, was once more creeping over his limbs. The potent drug was gaining mastery over his mind and limbs once more. What if he should succumb beneath its deadening effects?

Desperately he fought against the nausea, but suddenly his throat began to burn as if encased with a band of fire. He plucked feverishly at the collar of his native robes, which seemed to be choking him, forcing the blood to his head, so that his eyes were almost sightless.

As he fell to his knees, among the crumbling bones of an alien race, the sinister shapes on the tower turrets hopped, with grotesque and awkward movements, along the grating towards him. Cry after cry for help, hoarse and choking, left his lips. Still they came on, and their eyes, tiny pin-points of phosphorescent light, peered at him unblinkingly through the gloom.

Suddenly a moaning cry broke into the detective's frenzied thoughts. He turned his rapidly glazing eyes towards a circular hole, large enough to admit the passage of a man, in the grating. Above the edge appeared a face such as only the pen of a Dante could describe. It gibbered at him demonically, skeleton-like in its features, a living face in a place of long-dead things.

Blake stared at it in horror. Echoing hollowly around and about the great tower of the dead, rolled, booming, a peal of demoniacal laughter. It rose, it fell, it rose again. It was mad, devilish, a sound impossible to describe.

"My Heaven,' Blake muttered, "what is it?"

He rose like a drunken man, and there was madness in his glaring eyes as he turned them in the direction of that gibbering apparition. A low, shuddering cry left his lips. With quivering hands, as yellow and hooked as the claws of the vultures surrounding them, the nightmare horror pulled himself out of the aperture and approached nearer. The detective's heart leapt wildly in his breast; then seemed to suspend its pulsations and to grow icily cold. For past that clammily white face, those staring eyes, he could see other shapes rising from the pit, nameless visions which refused to disperse like the evil dreams he had hoped them to be.

The things which were advancing from that pit of the dead were actual, existent—to be counted with!

Further and further he drew himself away from them, snatching up Tinker in his arms, crouching in the shadows like a man demented with stark terror. Then, as they advanced yet closer—made as if to catch him in their skinny arms—he uttered a hoarse cry and sprang across the grating, on the side remote from those pallid horrors, who, strangely enough, were regarding him with a horror in their staring eyes akin to his own.

Then his brain succumbed to the drug. He reeled to the floor. How he shuddered as those yellow, skeleton-like hands touched his skin! How his very soul rose in revolt!

*

Then came a blank in the detective's recollections. When next he opened his eyes to the world again he was lying an a circular apartment of stone walls, high in one of which a solitary window gave a glimpse of sky like a square patch of velvet flecked with a few stars.

Bending over him was a vague shape, which to his dazed and horror-numbed senses gradually evolved from a shadow to—merciful heavens!—one of those pallid creatures which had crawled forth from the pit of the dead.

Iron man that he was, Blake dared not move—dared not make to pass that which lay between him and the door of the apartment. His whole body became chilled with horror. He dared not admit it was there, for he could not, with sanity, believe it to be anything human. For what he saw, yet dared not admit seeing in order to retain his sanity, was this:

A ghostly yellow face, which seemed to glisten in some faint reflected light, peered down at him with eyes as bright and black as a bird's, gibbered at him in some strange tongue, intruding where he had believed human intrusion to be impossible. And in the sinister shadows lurked others, vague shapes, whose presence seemed so utterly out of the realm of possibility—spirit forms who had risen from the ashes of the dead.

"My Heaven!" Blake whispered, and sprang into the centre of the room, Tinker was in their hands. They held him in their skinny arms, mere bones covered by a yellow, parchment-like skin. Trembling violently, his mind a feverish chaos, Blake sprang upon them.

"Sahib—sahib! We are your friends! Zoraster, in His mercy, has seen fit to resurrect you from the dead!"

Dead! Yes, that was it. He was dead. These nightmare men were not of his world. He laughed in a strange key, and his hands dropped to his sides. One of them came to him, and there was a kindness in his faded eyes which relieved the horror of his skeleton-like features.

"Who are you, sahib? You are not of our race? You were brought with your companion to the tower at dusk. Some miracle has happened. You were quite dead when we placed you on the grating, and some time afterwards we were attracted by your cries for help."

Blake grew calmer, and the strained look left his eyes. These men, so death-like in appearance, were the body carriers of those grim towers, men who had lived their lives amongst the dead ashes of past decades of their race. To his drugged and terror-distorted brain they had intruded like spirits of evil, but now he had proof that they were of flesh and blood, his mind became more rational.

"We are English,' he said, concealing with difficulty a shudder of revulsion as the man placed a yellow hand on his shoulder. "I am a detective, and by some means or other an enemy had me brought to the tower to be devoured by the vultures. But my assistant! Why do your friends hold him so—with a cloth covering his features?"

As the aged Parsee caught the white man's beseeching look, he muttered something beneath his breath, and in his dim eyes was a sympathy rarely seen. Blake grew sick at heart. The silence held a dread significance.

"He's not dead—my assistant?"

His life's blood seemed to be ebbing away from his heart, the strength from his limbs, as he saw the old man bend his head. Could it be true? Had the plucky lad gone at last? Blake felt as though the world had suddenly become very empty. Then a great rage took the place of the grief which was numbing him, and a silent vow to be revenged on Dass, the arch-murderer, the enemy of the white races, left him.

"Let me see the lad," he said.

Gently they carried the inert form to the bed. "As gently Blake lifted the cloth from the rigid features, and examined heart and pulse for any signs of animation. There was none. Every accepted symptom of death was present in that still, cold form.

Then, when hope was at its lowest ebb, Blake gave a little cry of gladness. From a wound, a flesh-torn wound in the arm caused by the sharp beak of a vulture, blood trickled in a red and mobile streak. Tinker lived! Blake's medical knowledge, which was considerable, told him that. If death possessed that form, the blood would be congealed and viscid, for rigor mortis would by now have set in.

And into Blake's mind flashed a memory of the past. A memory of when Dass, by using some subtle drug of the East, had faked death, and escaped from the prison mortuary to which they had carried him, for at the time the Hindoo had been incarcerated in the condemned cell of an English prison.

The affair unrolled itself plain and clear before him now. After falling into the hands of Dass at the joy-shop of Janjir, the scoundrel had doped them with this strange drug—dhatura—and had them carried to the tower as dead Parsees to be interned according to their supposed caste rites. His strong constitution had mercifully thrown off the effects of the drug in time, but Tinker still was under its influence, and before long would awaken to perfect health and strength.

Blake shuddered at the deadly nature of their common foe, in whose diabolical mind this fell affair had been devised. Then his eyes burned with concentrated hate and lust for vengeance. They blazed like hot coals in his white face. Dass should pay—pay to the hilt. And was not the hour of his vengeance at hand? When Tinker had been placed in safe hands, he would go to the joy-shop, and the reckoning would come. Dass, believing his evil scheme to have been successful, would be off his guard, and would fall into his hands.

"My friend is not dead," Blake said, turning to the repelling yet kindly Parsees, "but is suffering from the effect of a drug. If you can procure a gharry, I should be grateful, I have no time to explain now, except that we have been victims of a diabolical plot, but will send in a report to the secretary of the Panchayat."

Blake hesitated a minute.

"I understand little of your religion," he added, "yet enough to realise that our presence on the tower might be looked upon as a desecration. I assure you that the man responsible for the business will not go unpunished."

"No blame can he attached to you, sahib," said one of the watchers of the tower. "You were found at the native Serai, to all appearances dead, and wearing the chakka of our race. The Panehayat were notified, and you were brought here in the belief that you were of our caste. As we are forbidden to leave the tower, I will summon the watchman. He will find you a gharry."

Ten minutes later Blake had Tinker safely back at the hotel, and a British doctor from the fort was quickly in attendance. When his assistant had been pronounced out of danger, the detective went down to the hotel lobby, and, seating himself beneath a swinging punkah, considered his plans.

"I will go to the British commissioner and enlist his aid," he muttered. "With fifty juwams from the police-khana, I could draw a cordon around the joy-shop which would result in the capture of the whole gang. Thinking Tinker and me to be dead, Dass will neglect his usual precautions, and they should fall an easy prey."

As he rose to leave the hotel a night-porter hurried towards him.

"A gentleman to see you, sahib—a Mr. Fardunzi Parak, of the Zoroastrian Club."

"A Parsee," Blake said. "Very well, show the gentleman in. I can spare him little time, though."

A few minutes later an old gentleman, whose slightly Semitic cast of features betrayed his Parsee origin, was ushered into the detective's presence. His face was white and haggard, and his whole frame trembled as though gripped by some deep emotion. Blake's ready sympathy was aroused, and, rising, he dragged forward a chair.

"Sit down, Mr. Parak," he said kindly. "You appear to be in some deep trouble. Perhaps I can help you."

"Thank you, Mr. Blake! Heaven knows I need all the help I can get. I regret calling upon you at this late hour, but the affair is extremely urgent. My daughter has disappeared. She is in the hands of the dread League of the Roomal. Unless a rescue can be quickly effected, she will be sacrificed on the altar of some pagan goddess."

Blake glanced at the grief-stricken man in some surprise. Although familiar with most of the secret societies of the Orient, he had no knowledge of the League of the Roomal.

"Suppose you give me the details,' he said kindly. "I have no knowledge of the society you mention, although the roomal is the strangling-cloth of the worshippers of Kali the Destroyer. Does the league consist of a number of votaries of the goddess?"

"The league consists of a hundred and one priests of that evil goddess Kali—never more and never fewer," said the Parsee. "And they are greatly feared by the common herd, chiefly on account of the mystery which surrounds them. No one outside the sect knows where they worship. Vague rumour simply says that their temple is situated in the bowels of a great mountain in southern India. Their creed is a perfectly verbal one. Nothing is committed to writing, and the nature of their oath renders it impossible that any information can be divulged beyond the fraternity. It is terrible to think that my girl is in their clutches—my beautiful Zenda to be offered as a sacrifice to their hideous goddess!"

Blake stared at the man in horror.

"A human sacrifice!" he said sharply. "But surely those devilish rites have been stamped out?"

"It is impossible for you of the West to penetrate far below the surface of things Oriental, Mr. Blake," said the Parsee. "Even a few miles outside this city I have seen well-known business men wallowing naked in the blood of slain bullocks, and once, in my younger days, I saw a baby sacrificed on the altar of a jungle temple in the Terai country. The long arm of the British Raj cannot penetrate those dense jungle fastnesses, and many are the hideous and unholy rites practised there even at the present day."

Blake nodded, for he had long realised that beneath the calm and placid surface of the East ran dark and swift undercurrents which western eyes are never permitted to see.

"Have you any idea where this temple of the league is situated?"

The Parsee shook his head. His face had brightened a little, for there was something in the calm-voiced Englishman before him which inspired confidence.

"Its whereabouts is only known to the brothers of the sect," he said. "The limit in the number of the priesthood is a further safeguard against betrayal. As I have said, they, are never more or fewer than just one hundred and one. When a death occurs among the brotherhood, there is no burial and no incineration. He simply disappears, and is spoken of as having been carried away by Kali, the goddess of Death. The hundred surviving priests immediately elect his successor, a brother or a son from the same family being invariably chosen for the coveted dignity. In this way the league has grown to be a close family association, for the votaries of the goddess Kali inter-marry only among each other."

Mr. Parak paused for a moment, leaned his hand upon his arm, and gave way to the emotion within him.

"Mr. Blake, I know that every fifty moons—in other words, practically every five years—it is incumbent upon the High-priest of Kali to offer, as a living sacrifice to the bloodthirsty deity, a maiden of one of the fair races that dwell beyond the confines of India. I further know that the due observance of this dreadful rite is a matter of vital importance to the High-priest, for, failing his provision of a victim, he himself becomes a sacrifice to the death-goddess."

"What proof have you that your daughter has fallen into the hands of the league?" asked Blake, horrified by the distracted father's story. "I will help you in every way to effect her rescue. It is terrible to contemplate what her fate will be if left in those murderous hands."

"Heaven bless you, Mr. Blake!" said the father, clasping the detective's hands. "I will give you the story of her disappearance. An hour ago I was attracted by screams coming from my daughter's private apartment, and on rushing there found her missing. Evidence of a struggle lay in the fact that the curtains had been torn aside and that several articles of furniture had been overturned. I rushed into the street, but there was not a soul in sight. On returning to the room, in the hope of finding a clue, I found this."

The Parsee took something from his pocket, and handed it to the detective.

It was a thin circle of age-blackened rosetta wood, richly carved, and bearing the pattern of a Hindoo woman sitting on a throne. In one hand she held a roomal, and a tiny ruby, set in the centre of her brow, flashed with a venomous red spark.

About her waist was a girdle of skulls and withered hands, represented in the wood so that they appeared to be fastened to a large cobra coiled about her middle.

The whole pattern was repulsive and hideous in design, and Blake recognised at a glance that it was a representation of Kali, the Destroyer, the pagan goddess of evil, who has inspired her votaries to crimes horrible to contemplate in the long and mysterious Indian past.

"It was dropped by one of the men who carried my daughter off," said the Parsee, "and I believe it to be a badge of priesthood of the league. You will observe there is an inscription in Ramasee beneath. Translated, it reads: 'The League of the Roomal. Formed by the votaries of Kali the All-powerful, in order to perpetuate Her illustrious memory.'"

"May I retain this for the time being?" asked Blake, glancing at the design with undisguised curiosity. "It may help me in my investigations. I should also like a full description of your daughter. I will see that it is immediately telegraphed to every police-khana in India. To-morrow I will investigate the matter personally. I would do so at once, only I am engaged upon an urgent affair which I trust will be settled to-night. It is the capture of Gunga Dass, India's master-criminal, which at present occupies my time. Strangely enough, he is also a votary of Kali. It may be possible to extract some information as to the whereabouts of the secret temple of the league from him."

The Parsee's features lost much of their haggardness, for he was beginning to realise something of the capabilities which lay hidden beneath the placid exterior of the detective.

"Keep the carving by all means," he said. "I have a photograph of my daughter here, which will be far better than any verbal description. Heaven grant you success in your search!"

The old man, with trembling eagerness, took out a leather wallet and extracted a photograph. As Blake's keen eyes fell upon it, he jumped to his feet with a cry of astonishment. Two people were represented on the photograph—a beautiful Parsee girl, dressed in a silk saree of exquisite design, and a young man of the same Persian race, weak, and cunning of features.

"Who is the Parsee youth?" he asked sharply. "Unless I am badly mistaken, he had a hand in the abduction of your daughter. He was in the company of Gunga Dass, in Janjir's joy-shop, a low, haunt of the bazaar crowd, a few hours ago."

The eyes of the old Parsee became clouded.

"He is my adopted son," he said. "Many years ago my business partner died, as his son, his only child, was motherless, I took him under the shelter of my roof. When he reached the age of twenty-one his father's fortune, nearly a lakh of rupees, was made over to him; but he squandered the whole in two years, and came back to me penniless.

"I again accepted him into my household, even gave him a junior partnership in my business, in order to encourage him to run straight, but he robbed me right and left. Discovering his thefts, which, as I am a dealer in precious stones, was considerable; I washed my hands of him entirely.

"This took place about two months ago, and I have since heard that he has become a companion of thieves and haunts the vilest dens in Black Town. But, bad as he has been, there is surely some mistake! I cannot credit him guilty of so treacherous an act as to cause my only child, his playmate from boyhood days, to be stolen from me and sacrificed."

Blake studied the portrait of the youth carefully. There was weakness and cupidity in the Semitic features. Yet there was something pleasing in it, too. Some quality in the smile on the full lips, an expression in the dark eyes, beneath their drooping Oriental lids, hinted at that trace of virtue which is supposed to be present even in the worst of us.

Blake was inclined to think Fardunzi Parak was right. He could read a dishonest and shiftless nature in those features so faithfully portrayed, but not the hardness or evilness of a man who would deliver a young and beautiful girl to a body of Thugs whose religion was to destroy.

He slipped the photograph and carving of Kali into his pocket.

"I believe you to be right," he said thoughtfully, "although I am still convinced that this youth had a hand in the abduction of your daughter. It is possible that he has simply been the tool of Gunga Dass, and has been kept in ignorance of the purpose for which the girl was wanted."

"And you believe Gunga Dass to be implicated in the affair, Mr. Blake?"

Blake lit a cheroot, and smoked away thoughtfully for a moment, his mind busy with the intricate problem before him. He was convinced that Dass was in league with the brotherhood of the Kali priests, for he had suppressed the arch-murderer's Thug activities before to-day. and now-it would appear, if his theory that Dass held the power was correct, that the Hindoo was the High-priest of the sect, and that he had procured her for the purpose of sacrifice in order to save his own neck.

But what part had the adopted son of Fardunzi Parak played in the affair? When the young man had burst upon Dass in Janjir's joy-shop his manner had been wild and agitated in the extreme. Had he, aided by his knowledge of the household and the position of the rooms, carried off the girl and handed her over to Gunga Dass?

Blake inclined to this theory. He was beginning to see light. He had proof positive, by the conversation of Dass and the Parsee, that they had some evil scheme afoot, a scheme which Dass did not intend to reach Blake's ears.

"I am inclined to think that the young man will soon be making you an offer to release your daughter in return for a certain sum of money, Mr. Parak," he said slowly.

"Then this League of the Roomal badge of priesthood was simply left behind as a bluff?" said the Parsee. "Am I to understand that Biradah—that is the boy's name—has abducted her in order to hold her to ransom? By Heaven, I will see that the black-hearted young scoundrel does not touch a rupee! I will have him clapped into the House of Correction for this."

"To hold her to ransom was Biradah's intention, I believe," Blake said; "but I have a suspicion she is out of his hands now."

"How do you mean?"

"I believe that Biradah enlisted the aid of Dunga Dass to help him carry out his scheme, and that Dass has double-crossed him," Blake said thoughtfully. "It is possible that Dass instructed him and bluffed him into faking the abduction so that it would appear to be the work of the League of the Roomal, in order that you, terrorised by the fear of what your daughter's fate might be, would willingly pay a large sum in order to have her safely returned to you."

"Then am I to understand it is not the work of the league?" asked Parak, a note of relief in his voice. "That they are in no way implicated in the affair?"

Blake shook his head.

"No, Mr. Parak; I am convinced that Daas is the High-priest of the league, and that the girl is intended to be used as a sacrifice. But I am also convinced that Biradah knew nothing of this. While Biradah thought it was sheer bluff, Dass was working for his own ends as a genuine member of the league. Although I believe the youth to be unconscious of the fact, Zenda, your daughter is really in dire peril of her life."

"But you will rescue her?"

The old man was trembling with emotion, and, as Blake rose, he placed kindly hands on the bent shoulders.

"If I am successful in effecting the capture of Gunga Dass during the raid I have planned to take place at the joy-shop in a few hours' time, I feel certain your daughter will be saved," he said. "If my theory is correct, she must be hidden somewhere in Janjir's establishment. Go back to your house now. I will let you know immediately anything comes to light. Rest assured I shall leave no stone unturned to defeat the ends of Gunga Dass."

"Heaven bless you, Mr. Blake!' said the old Parsee, and his dimmed eyes looked their gratitude into the detective's. "It is terrible to contemplate the result of failure. I pray, with all my heart, you will be successful in your search!"

Blake pressed his hand in silent sympathy. They had walked to the hotel entrance now, and a young Hindoo, whose rolling gait indicated that he had looked upon the wine when it was red, lurched up the stone steps towards them.

He was attired in evening-dress, and his general appearance was that of one of the many students at the colleges who resided at the hotel. As he passed the detective Blake did not even glance in his direction, and, after wishing the Parsee good-night and offering him what encouragement he could, he left him and turned back into the hotel lobby.

As he passed a palm-tree, whose feathery plumes cast a deep shadow against the wall, the Hindoo, now betraying nothing of the inebriate in his noiseless and cat-like tread, detached himself from the gloom and raced after the unsuspecting Britisher.

In his hand he held a small tin cannister which glittered like silver, and, catching up with Blake, the man flung the contents full into the detective's face.

With a cry of pain, Blake staggered backwards. His eyes were burning like hot coals and were sightless. He felt hands roughly searching his clothing, the patter of swiftly retreating footsteps, and then the silence told him he was alone.

The Raid—The Cunning of Gunga Dass—On the Scent.

BLAKE leant against the wall in agony. His eyes were smarting and swollen, and his dazed senses had not yet realised what had taken place. He staggered to a table in the lounge, upon which stood a flask of water, and, soaking his handkerchief into the cooling liquid, he bathed his burning eyes.

"Hallo, Blake! What the deuce is the matter?"

Blake swung round at the sound of the voice, and dimly saw that Captain Mitchell, the medical officer he had summoned from the fort to Tinker's aid, was standing beside him, with a puzzled expression on his sunburned features.

"Hallo, Mitchell!" Blake said weakly. "Some dirty rascal must have flung pepper in my eyes and snatched my wallet. It's an old London pickpocket's trick, and darned painful, I can assure you. See what you can do for me, old man."