RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"THEY'RE seven dollars fifty, Mr. Lynd," said Kitty Kate, "but I'm real sure there isn't another pair like them in Blue Springs."

"The price is all right, Kitty," said the tall young man on the other side of the counter. "And they're just what I was looking for. The only thing—" He stopped and a tinge of red showed on his bronzed cheeks.

"You're wondering if they'll fit," said Kitty with a twinkle in her dark eyes. "Well, you don't need to worry. They're just the right size." Larry Lynd looked up sharply from the pair of beautifully embroidered Indian slippers. "How—" he began.

"How do I know?" cut in Kitty, "Because I fitted Miss Hallam with a pair of shoes less than three months ago." Larry frowned, then laughed.

"You know too much, Kitty." He examined the slippers once more, slipped something inside, then gave them back to the girl. "Wrap 'em up. Here's the money."

As Kitty Kate made up the parcel a slim, upright man in mounted police uniform came into the store.

"Larry," he said in a low voice, "I've been looking for you all over. Shenley's taken ill. Had to have the doctor. He can't go out with you to-day. You'd better stay the night."

Larry shook his head.

"No need, Sergeant. I don't reckon on any trouble. There's weather brewing and, if I wait over, likely I won't be able to cross the pass."

Anderson came closer.

"You'll be worth robbing, Larry.

"Who's going to rob me? There's not a soul in this town but you and Shenley and the bank manager know I'm carrying the payroll. Doran's always taken it up to now. Besides, there's never been any trouble on the road. Thanks to you, this country's pretty well cleaned up."

Anderson shrugged.

"There's not much risk really. And it is going to snow. All right, Larry, push on if you want to. But I'd go soon if I was you."

"I'm leaving right away," Larry said as he picked up his parcel. "Good-bye, Kitty."

Anderson went out with him to the end of the street, then the two men shook hands and Larry strode away up the trail leading to Granite Mountain and the Hard Rock Mine.

Hard frozen snow coated the surface of Granite Mountain Pass, and long streamers of snow dust trailing like flags from the lofty pinnacles showed that a blizzard was brewing. But Larry was not worrying. He would be home before the storm broke and he strode rapidly up hill.

It was true that he was worth robbing for he had more than three thousand dollars in paper money, the Christmas payroll for the Hard Rock Mine tucked away in his belt. But actually he was thinking much more of the slippers than of the money or the other gifts.

These were exactly what he had wanted as his gift for Gay Hallam, the charmingly pretty schoolmistress at Hard Rock, the girl whom Larry loved with every fibre of his long, clean, young body and not inconsiderable brain. As he happened to know, the slippers were just what Gay wanted and he had fully made up his mind to offer himself along with his Christmas gift.

Whether she would have him or not was another question. Larry was only too well aware that at least three other men besides himself were in love with Gay, yet he had an inner conviction that she liked him best.

The higher he got the colder and stronger grow the wind, and at Kicking Mule Corner, where the narrow trail rounded a great rock pinnacle such a blast met him that he had to lower his head and butt into it. That prevented him from seeing the masked man who stopped out swiftly and silently from behind the pillar or the loaded club this man grasped in his right hand.

All Larry knew was a crash as of the sky falling—afterwards nothing at all.

BEING knocked out is nothing; coming round from a bad blow on the head is a horrible experience. When Larry Lynd opened his eyes all he was conscious of was pain, jumping throbs of pain in his skull, his jaws and his eyes. He found himself nearly buried in a snow drift and could not remember how he got there or, indeed, much of anything else.

But Larry was a strong man, in fine condition, and soon got a grip of himself. He sat up and found himself in a snow-bank which had formed on a ledge half way down the cliff. The drift had saved his life for, if he had fallen six feet one way or the other, he would have gone clear to the bottom and to certain death.

He put his hand to his head. There was a huge sore lump on the back. Next he felt for his belt but it was gone. He realised that he had been slugged, robbed and pushed over the ledge of the pass.

"He meant to kill me," he said aloud. He was bitterly angry.

He was still with cold, but the snow had saved his bones. At any rate, none was broken. He looked upwards. Not a hope. A cat could not have climbed that cliff. He looked down and the prospect was almost as bad. It was all of 70ft to the bottom and very nearly sheer. But the rock face was seamed with deep clefts, while here and there were jagged outcrops. There was one a little to the left and, if he could reach it, he thought he saw a way down. He would have to jump and if he missed—!

It was no use waiting. That only made it worse. He gathered himself and leaped. He reached the ledge, his feet slipped but he flung himself flat, jammed his fingers into a crack, and was saved from falling.

When he had got back his breath he rose and started down a sort of chimney which traversed the face of the cliff. Frozen snow and ice made every step a peril and time and again he was within the shadow of death. When at last he reached the bottom he was so done he had to drop upon a rock and sit until his over-strained heart ceased thumping.

Ice-flakes stung his face. Already the storm was upon him. His heart sank for he was still five miles from home and it meant a long round and a steep climb to regain the road. He could rest no longer for now every minute was precious. If he failed to reach Hard Rock before dark the odds were long that he would never reach it alive.

The ground was terribly rough and he kept on breaking through the snow crust. He had not worn snow shoes, for the trail itself was beaten hard and he had had no intention of leaving it. Now he needed them sorely. The snow fell thicker and thicker until it was a driving fog of ice particles through which Larry could see nothing beyond a radius of a few yards.

Still he stuck to it. The thought of Gay kept him going and proved the power of mind over matter for his strength was hardly equal to putting one foot in front of the other. The snow-dust smothered him, the cruel gale was numbing him, but the worst of it was that he had not the faintest notion where he was.

"Plumb lost," he remarked. "Might just as well have stayed on that ledge. I'd have saved myself a heap, of trouble." He paused a moment behind a rock, scraped the ice from his cheeks, then went on again. It was getting dark and Larry knew that, unless a miracle happened, he would never again see daylight. Yet he kept going.

The miracle did happen. A patch of yellow light showed faintly through the smother.

Larry staggered towards it and had just strength to give one loud thump on the door of a small cabin before his senses left him and he dropped on the doorstop.

THIS second coming to was not so bad as the first. When Larry's senses returned he was chiefly conscious of a sense of delightful warmth, and of a languor so complete he did not want to move or think. At last he opened his eyes. He was lying in a bunk, wrapped in blankets, in a small room illuminated by an oil lamp and heated by a rusty red-hot stove. A tall, lean old man was busy over the stove and the warm air was luscious with the odor of stewing venison.

"Hulloa!" said Larry and was startled to find his voice little better than a whisper. The other turned.

"Holloa, son. How do ye feel? You didn't much more'n make it."

"Glad I made you hear," Larry said. "I was all in."

"You was that. How come that bump on your head?" Larry hesitated.

"You don't have to tell me," said the other sharply. "Greg Haythorne don't ask no confidences. Here, drink some o' this." He gave Larry a mug of hot coffee mixed with condensed milk and Larry thought he had never tasted anything so good.

"And now I'll tell you the whole thing, Mr. Haythorne," he said, and did so. The old man listened, then nodded.

"Any notion who laid for you, Lynd?"

"No more than you," Larry answered, "but when I find him—" Gregory grinned.

"You'll learn, him, I'll warrant. But you'll have to wait. It's storming to beat the band."

"And all the time that dirty thief is getting further and further away with the payroll," Larry growled.

"He won't get far in this weather. Can you eat a plate of stew?"

"Try me," said Larry. And the old man handed him the plate and a bannock. The food put new life into Larry, and after he had finished he toppled straight into deep sleep. When he woke it was daylight and, feeling quite himself, Larry got up, dressed and helped with breakfast. He was dead keen to start for the mine, but the gale still drove the frozen drift hissing across the waste of white.

"She won't let up a while yet," Gregory told Larry, "so you may just as well take it easy." But Larry couldn't take it easy. This was Christmas eve and all the time he was wondering what his boss, grim old George Lingard, was thinking. The loss of the payroll was a serious matter, and Larry was desperately anxious to organise pursuit of the thief. The slippers, too.

That theft stuck in his throat almost worse than the payroll. Now he had nothing to give Gay. All the morning he kept watching the window, but it was past two in the afternoon before Larry, wearing a pair of rackets lent him by the old trapper, was able to start. The drifts wore enormous, the way was all up hill and it was dusk before Larry at last reached Hard Rock.

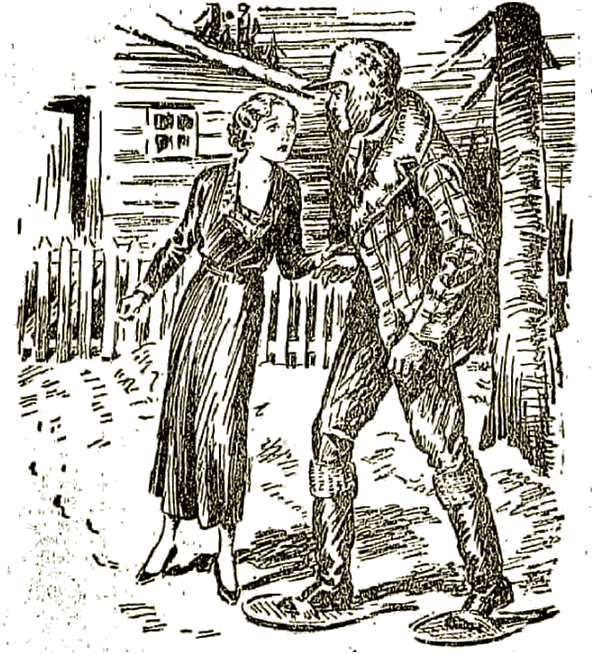

The school-house was almost the first building Larry reached, and he longed to rush in for one word with Gay, but his duty was to see Lingard first. The cold was intense, the little street was empty; then as Larry swung past the school-house gate, suddenly Gay herself came running out.

"Larry—Larry! Oh, is it you?" He stopped.

"It's Larry, Gay. Wait till I've seen the boss, then I'll be back."

"No!" she said breathlessly. "Come here. Come in quickly." Wondering, Larry obeyed. He wondered still more when he saw Gay's face. It was racked with trouble.

She caught his arm, pulled him inside and quickly closed the door.

"I told them," she went on; "I told them you'd come back. I—" she broke off. "Did anyone see you, Larry?"

"See me?" Larry repeated. He felt half dazed. "No—no one but you."

"Oh, I'm so glad, so thankful. But where can I hide you?" Larry pulled himself together.

"Gay, are you crazy, or am I? What's the matter?"

"Don't you know? Don't you understand? They say you—you ran away with the payroll." Larry's eyes blazed.

"Who says so?"

"Mr. Lingard—all of them."

"Lingard!" Larry's voice was low and dangerous. He took a step towards the door. "Lingard thinks I'm a thief. I'll soon settle that." Again Gay caught him and held him.

"Larry, they're all against you. The men are furious because they haven't got their Christmas money. It isn't safe for you to go into the town. Please—please don't try it." In spite of his anger, Larry's heart gave a great bound. Gay cared. Her voice, her eyes, everything told him. The knowledge steadied him.

"I was robbed, Gay," he said and quickly told of the robbery and attempt to murder him. She shivered.

"Who did it? Who could have done such a horrible thing?"

"Someone from here, Gay. No one at Blue Springs except Anderson, Shenley, and the bank manager know I had the roll."

"And Shenley was ill?"

"Yes, and I'll lay his illness wasn't natural either," said Larry grimly. "Gay, dear, let me go. I must tell Lingard."

"No." Gay's tone was firm, "Listen Larry. They're all coming here, to-night for the Christmas Tree. This man—the one who robbed you—must believe you to be dead. He may give himself away. We must watch and see."

"We, Gay? How can I watch? There's no place to hide in the school-room."

"But you will be disguised. Only just now Billy Davies sent to say he wasn't able to come to-night. He was going to be Father Christmas. You will take his place. You are just his height and can imitate his voice." She glanced at the clock on the chimney-piece of her pretty sitting room. "There is no time to waste. You must get into the dress at once. Come into my room."

Larry had never before been in a girl's bedroom. He felt oddly shy. Gay was far too anxious for any such feeling. The red robe trimmed with cotton wool lay on the bed. She put it on quickly, then the cap and the whiskers. She touched up his face with grease-paint and told him to look at himself in the glass. He stared at his reflection.

"Gee, I wouldn't know myself, Gay."

"No, it's a perfect disguise. Now we must go. The children will be coming almost at once."

WITH its bright lights and festoons of colored paper the school-room was a cheerful place. The tree, loaded with candles and gifts, stood in the centre and beside it Larry, the perfect Father Christmas.

Gay opened the door and the children surged in shouting and laughing. Behind came the elders. George Lingard himself was there and so was almost everyone else belonging to the mine.

But the elders were not as cheerful as the children. The loss of the payroll was a serious matter and Larry's spirits, low enough already, sank still lower as he noticed the hard, grim look on Lingard's face. There would be small mercy for him if the thief were not discovered.

Larry was busy at once snipping presents from the tree and handing out larger packages from the table below it. But he was not too busy to spot the little group that collected around Gay—Dick Douglas, Barry MacBain, Frank Maitland and John Doran. They were all her admirers. Dick was remarkably good looking, Barry had brains, Frank was son of the chief engineer, and John Doran, the boss's own nephew. All had more to recommend them than Larry and all had presents for Gay. Larry bit his lip as he thought of the slippers and remembered that now he had nothing to give Gay.

For a while he was swamped by the horde of children. Of course he knew them all but it was an effort to disguise his voice and to keep his mind on his job. He hadn't a moment to watch the others, and as for discovering the thief, the chances were too thin to think of.

The rush slacked off and suddenly Gay was beside him.

"See what I've got, Father Christmas." She laid a pile of presents on the table and suddenly Larry's heart was in his mouth. Among them were the slippers he had brought from Blue Springs.

"Who gave you those slippers?" he whispered urgently. A startled look was in Gay's eyes.

"John Doran," she answered in an equally low voice. Larry snatched up the slippers and strode across to Doran.

"Where did you get these, Doran?" His voice carried all over the room and there was a sudden hush. Doran, tall as Larry, eagle-nosed, hard-lipped, stiffened.

"I'm asking you, where you got these slippers you've just given to Miss Hallam." Doran did not flinch yet Larry saw his eyes flicker. Then quick as a flash Doran snatched off Larry's wig.

"It's Lynd," he shouted. "The man who stole the payroll." With an ugly growl the others closed in, but like a flash Gay darted between them.

"You've no proof," she cried breathlessly. "Let Mr. Doran answer Larry's question" Gaunt-faced John Lingard forced his way in.

"Yes, answer his question, John. Then we'll deal with him."

"I bought them from the Indian woman who made them," Doran answered curtly. "Naturally she didn't give me a receipt for she can't write, but I can produce her. She lives on the Red Cloud Reservation." There was a tense silence. All eyes were on Larry. Gay's face was agonised but Larry kept cool.

"Mr. Lingard, I will ask you to put your hand into the right slipper and take out what you will find there." Lingard scowling did so and took out a crumpled slip. He smoothed it and his eyes widened as he read it.

"Whose writing is that?" asked Larry.

"Yours," replied the other in a startled voice.

"Yes, It's mine, and the slippers were bought by me from Kitty Kate at Walton's Store in Blue Springs. If Doran hadn't felt sure he had finished me when he slugged me, robbed me, and throw me over the cliff—"

There was a crash—John Doran, whirling, had dashed for the door, upsetting a table as he went. He hadn't a chance. Half a dozen men seized him and, in spite of his struggles, held him.

"Well?" said Larry, facing him.

"You win," Doran snarled. "The money's in my room." Lingard went white.

"Take him away," he said in a cold still voice. They took him and the others crowded round Larry. They made him tell the whole story, and listened with breathless interest. Dick Douglas spoke.

"Gay, what's on the slip?" he asked coaxingly. Gay faced them. Her pretty cheeks were pink and her very blue eyes bright.

"With love from Larry," she read out bravely.

"No hope for us any longer, boys," said Dick. "Congratulations, Larry."

"Merry Christmas, Larry," shouted the children.

"It's going to be," said Larry, and put his arm round Gay.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.