RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

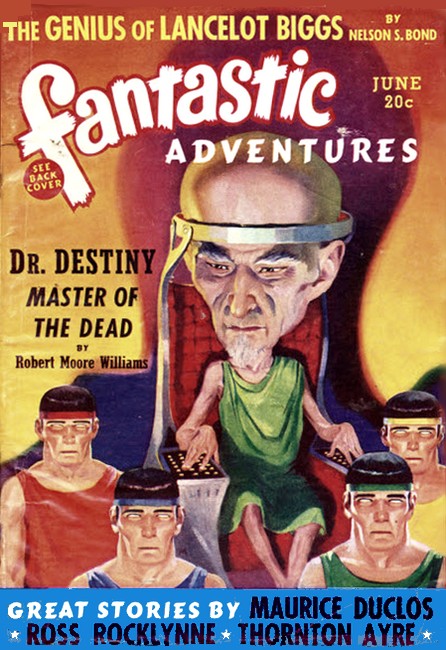

Fantastic Adventures, Jun 1940, with "Sabotage On Mars"

A tank smashed through the wall below, the guns spitting flame.

THE big desert bus slid to a halt. I spat the sand out of my mouth and eased myself off the rods. Then I crawled out between the caterpillar treads, being careful to choose the side of the bus opposite to where the passengers were getting off.

Every bone in my body was crying out in agony after the long uncomfortable ride clinging to those damnable rods.

"Damn!" I muttered.

I had reason to say more than that, for my legs were numb, and my arms were burned red with sand where I'd been forced to hang on for dear life as the bus lurched over the dunes, or lunged like a mad hippo into an especially soft dune. My hair was full of grit and so was my mouth.

"Sand!" I exclaimed in disgust.

I spat once or twice then gave it up. I'd have to chew sand until I got a drink. But I was in town at last.

I knew the town was just another of those infernal jerkwater army burgs that dot the desert wastes of Mars. So I didn't bother to glance around; I just patted the dust off my clothes and sprang up and down like a boxer waiting for the bell.

In fact, I was so busy I didn't hear the woman come up. First thing I knew, a tinkling honey voice was saying,

"Welcome to Crestview. I'm so glad you were able to make it!"

I jerked my head around. Standing next to me was an eyeful; the dark exotic type. Skin the color of old ivory, big flashing eyes with a hint of fire in their depths, streamlined figure. The sort of dame you might expect to see on Wilshire Boulevard or the Martian Way—in other words, as out of place in this wind-swept dump as a luscious peach on a quince tree.

She was smiling too. But I'm no sucker. I shot a quick glance behind me; no one was there. So I turned back and said,

"Eh?"

Her voice was as smooth as honey. "Welcome to Crestview, Doctor."

"Doctor!"

I gulped and wondered if I was hearing right. Doctor—What kind of a person was this medico she had mistaken me for? Or maybe this was her idea of fun....

I batted my hat viciously, making the dust fly.

"Sure you haven't got your wires crossed, lady?"

She laughed throatily. "Of course not! Don't you remember the General Hospital on Earth? I was a student nurse, you an interne. I gave it up after a while. Don't you remember Marcia Koch?"

"I certainly don't," I said. "Who—?"

"I understand. You were so busy and everything. You never had time for women, anyway."

"Oh, I don't know—" I began, but she kept right on talking.

"All that's changed now, isn't it, Doctor? We'll be seeing quite a lot of each other, now that you've accepted the job here."

A job! I began to take more interest in the conversation. I'd hunted over half of Mars for a good job, and even though I had youth and strength on my side, I'd only managed to pick up odds and ends. Right now a dime and a few pennies jingled forlornly in my pocket. I wanted a job badly—even to the extent of posing as a doctor!

I shot a glance over this streamlined heart-throb who called herself Marcia Koch. Interesting possibilities became apparent, even in the big dark eyes that gazed into mine.

"Marcia," I said, "you fascinate me. What about this job?"

She showed even pearly teeth. "Don't worry, Doctor, your pay will be generous. In fact, very generous."

She slipped a slim arm through mine, drew me toward a long black limousine that stood on one side of the sandy patch that posed as a road.

She gazed up at me. "I—got your call about losing your suitcase. Annoying luck when you're on a trip. I've taken the liberty of sending for some new clothes for you."

A SHORT swarthy driver held the car door open for us. The caterpillar treads kicked up the sand, and we were whizzing down a dusty road past a few huddled store buildings. A house was visible here and there, some army barracks in the background, then we were in the open.

I eased luxuriously back into the cushions and stretched out my legs. Riding the rods one minute, the next gliding along in a limousine with a beautiful woman at my side! Well, it was a little confusing. I couldn't help wondering what would happen next—what this young lady was up to, what sort of performance I would be expected to give.

The car halted before a husky steel gate set in a high brick wall—the kind that would be swell for an insane asylum or prison. A dark foreign-looking man, who might have been a brother of our chauffeur, opened the gates, and in we rolled. I saw that the wall enclosed plenty of acreage. In the center were several trim buildings; a big modernistic mansion, a bungalow, and a square building with a white-domed roof like an observatory.

I thought it was about time for a little information from Marcia.

"Well, well!" I said. "Is that an observatory?"

"Um-m," she responded. "Yes and no."

Just then the car eased to a stop before the mansion and a butler popped out of nowhere to open the door for us.

Marcia smiled sleekly.

"Well, here we are, Doctor!"

She held me back with a hand.

"James—the butler—will show you to your room. You can freshen up and change into a new suit, then we'll talk about your job. And, oh yes, Doctor—when you—ah—shave, you might skip the whiskers on your chin. It'll give you sort of a Vandyke effect—more professional looking, you know!"

Well, if I do say so myself, I did look like a professional man after I'd got cleaned up and decked out in a new suit. Of course, my face was a little red and chapped from riding under the bus, and my eyes were bloodshot. But heck, anyone would put that down as being caused by too many gin fizzes.

So I went downstairs, and one of the innumerable servants directed me into the library where Marcia Koch waited. She had changed into a filmy yellow outfit that made her more dazzling than ever.

I gulped and said to myself, "Nice stuff!" Out loud I remarked, "Quite a dump you've got, Marcia. All by your lonesome here?"

Her eyes swung in rapid survey over me, centered coldly on my face as though trying to dig around in my thoughts. Finally she said,

"I don't live by myself—haven't you noticed the servants? And another thing—for a doctor, your language is atrocious!"

I could see suspicion in her eyes.

"Listen," I told her, "maybe I'm dumb, but I don't see any literary pearls dropping off your lips."

Her ivory cheeks got a little flushed, but I went right on.

"Anyway, I thought you wanted to explain about a job. What sort is it?"

"Doctoring!" she spat out and the word sizzled.

"Yeah. I gathered as much. Who's the patient?"

"There isn't any—yet!"

I opened my mouth to say something, then shut it. I couldn't get back on our former chummy basis by antagonizing her.

MARCIA KOCH leaned against a reading table, kept her eyes on me.

"I'm employing you," she said, "to watch the health of a Mr. Walters. He's a scientist who has allowed me to help him financially. He's getting along in years and something might conceivably happen to his health. That's why you're here. Your pay, by the way, will be five hundred a week."

My jaw failed to function right, "Five hundred!" I stammered. "Five hundred to play nursemaid?" Gosh, maybe I'd stumbled into a crazy house after all!

"Five hundred is correct." She nodded her sleek head. "But the job will probably not last much longer than a week."

It still didn't make sense. "What about this Walters guy?" I asked. "I suppose he putters around in that domed building that isn't an observatory, yet is one."

"Yes," she said crisply. "That's his laboratory. I had it built for him several years ago. Poor fellow had spent all his money trying to solve a problem. His results were encouraging but he couldn't continue without money. But everyone he approached laughed at him, called him a 'visionary'.

"I was the only person to see possibilities in his work. And since I have wealth, I considered it my duty to bring him here and let him continue this great work; he has really achieved marvelous results, although he hasn't quite reached his goal yet. But I'm satisfied."

I met her eyes. "Yeah? Now let me ask a question. Just where do I fit in? Suppose I went to work this instant; what would I do?"

Marcia drew herself up. "You'd get acquainted with your prospective patient, of course. He lives with his daughter in that little bungalow outside, but he'll probably be in the laboratory right now. Let's go!"

I followed her out of the house, and we ambled past a couple of dark husky gardeners very busily doing stuff to bushes. We reached the white observatory-like building, stopped before a door. This door was set right in a larger door—a big thing about twice the height and width of an automobile garage door. I suppose it was opened only to bring in bulky pieces of apparatus.

Marcia pressed a bell button and we stood there waiting for the door to open. I guess she saw my raised eyebrows.

"Mr. Walters," she said, "keeps the door locked. He doesn't like to be disturbed."

The door cracked open a trifle and somebody behind it gave us the onceover. Then it opened entirely, and there stood a dazzling little slip of a blue-eyed blonde.

"Come in, Miss Koch," said the blonde, and her voice was as smooth as butter on hotcakes.

In we went. Well, it was a laboratory of some kind, all right, but it looked more like a powerhouse to me. There was a cleared space running from the big garage doors clear to the center of the room. Around this clearing hulked huge transformers, glass tubes and cables and stuff. A wilderness of it.

"Where's your father, Lucy?" purred Marcia sweetly. "I want him to meet the doctor here."

"He's over this way," said the blonde, walking with us past the conglomerated junk. She was a luscious tidbit if ever there was one. Wow! I couldn't keep my eyes off her. And I saw with interest that she was watching me out of the corner of her own big blue eyes.

WE drew up on one side of the clearing where a man was working. He stood on a stepladder before a big panel of instruments, doing things with a soldering iron. He looked to be about sixty-five, thin, shriveled.

There were bags underneath his eyes, wrinkles on his dead-white face. Only thing that looked alive about him were his eyes. They were blue like his daughter's, with a peculiar frosty glint. Nothing old about those orbs; they were young, and they snapped with an inner fire.

Marcia turned on the old personality gag.

"Oh Mr. Walters," she cooed, "I want you to meet an old friend of mine. Doctor—ah—Doctor Pfaffinger."

Inwardly I groaned. Pfaffinger! What a moniker! No wonder she'd momentarily forgotten it. I smiled and stuck up my hand.

"Glad t'meet you, Walters," I boomed.

"Delighted, I'm sure," he replied, taking my hand. "A doctor, eh? Somebody around here sick?"

That blast froze my mouth. But it didn't bother Marcia a bit. She went right on talking chattily, and the old goat went right on splattering solder around with his iron.

"You see," said Marcia, "Doctor Pfaffinger and I were both students at the same hospital on Earth. He happened to be visiting Mars, so for old times' sake I asked him to stay with us a few days. As a matter of fact, I've decided to let him give you a complete check-over tomorrow, Mr. Walters!"

The old fellow almost vibrated off his perch.

"What!" he spluttered. "Why, I've never felt better in my life!"

"That's just the point," purred Marcia. "You've been spending too much time on your work. You must be careful of your health—mustn't he, Doctor?"

She eased around in my direction. My head see-sawed up and down mechanically.

The blonde's big blue eyes were fixed on me anxiously.

"I'm sure father's health is perfect.... Thanks just the same for your interest, Doctor Pfaf—uh—Doctor."

Under the dazzling gaze of those orbs 1 felt a warm glow of returning life.

I made clucking noises of reproach. "Why, Lucy! I shouldn't think you'd want to take a chance with your father's health. Just because a person feels well means nothing at all. I'll give him the once-over. In fact—"

I reached down, grabbed one of her hands and pressed a finger near her wrist, where there's supposed to be a pulse.

"In fact— Yes, I'd better give you a thorough check-over, too!"

I felt Marcia's arm suddenly in mine, and then I was being turned around toward the door. But this seemed a too-abrupt way of parting company with Walters and his daughter. So I sent a farewell shot over my shoulder toward the petrified statue of science on the stepladder.

"Ben Franklin sure knew his stuff," I called. "You get quite a jolt out of experimenting with electricity, eh, Walters?"

I started to laugh at my own wit, but Walters jerked back to life and his excitement drowned me out.

"Electricity!" he exclaimed. "My dear fellow, I work with atoms! I take things apart, make atoms out of them, then I put them together again."

"Hm-m," I remarked. "Isn't that a waste of effort? If you take things apart and then put—"

I got no further. One of Marcia's stubby slippers contacted very smartly with my shin. Then I was whisked past the masses of apparatus and through the door into the open.

MARCIA didn't say a thing. I didn't say a thing. She just hung onto me desperately, as if I might evaporate. I kind of liked that; I could feel the rhythmic sway of her hips against me as we walked toward the mansion.

Well, I began to get ideas about cutting myself a piece of cake. Hell, who wouldn't have? It's not every day you have an apparently unattached and apparently rich and obviously beautiful young thing clinging to your arm.

Then I remembered some fool proverb about, "He who hesitates is lost." So when we got on the porch I stopped her masterfully, whipped my arm about her waist and drew her close. There wasn't an ounce of resistance in her as I did a good job of osculation. That's what fooled me—that and a few other things. One of them was the quickness of her reflexes after I'd released her.

I didn't see her fist until it landed like a condensed version of the Fourth of July in my left eye.

"You clumsy clod!" she spat out, and glared at me from eyes that were as hard and cold as black ice.

I got my mouth open to say something, and by that time some of the husky gardeners had plopped out of nowhere and surrounded me—not two of them but three, with a butler thrown in for good measure. One had a sickle in his hand, one a shovel, the other a rake. The butler was armed with nothing but a big brown fist that looked as hard as cast iron.

"Shall we give dis lug a woiking over, Miss?" he asked politely of Marcia.

She shook her head. "No. I can take care of him all right. Go back to your posts, all of you."

After they'd gone I dabbed at my eye with a handkerchief and breathed easier.

Standing stiff and straight, Marcia held the door open for me.

"Come in, you," she said acidly. "There's some talking to be done!" We went into the library again and I dropped into a chair. She sat at a nearby desk.

"Now that you've forced the issue, Doctor," she began, " I think we'd better come to an understanding. You have only one job here—to watch the health of Mr. Walters."

"Yeah, I know," I remarked. "But he doesn't seem to be a very cooperative fellow."

Her eyes gleamed. "That can be taken care of."

"Huh! It'd take a sledgehammer to bring him around."

She shook her sleek head. "Not quite —just a little stuff in his coffee."

I blinked. "Eh? Come again?"

"I remarked," she said smoothly, "that after eating supper one of these evenings, Mr. Walters is going to develop a stomach ache."

"How do you know?"

Marcia sat on the edge of her chair, leaned her elbows on the desk. Her dark eyes never left my face.

"Oh, he'll get a stomach ache, never fear. As I've explained, he and his daughter live in that little bungalow by the laboratory. They're rather tied down, though, and it's hard for them to get into town for food supplies.

"So I have my cook bring over their meals to them. Walters drinks coffee, his daughter doesn't.... So he's going to get such a painful stomach ache, he'll be glad to catch sight of your face. You'll feel very sorry for him, give him a hypo to ease the pain.

"It is quite possible that this hypo will be so powerful that he'll go to sleep—ah—permanently...."

I sat and stared at Marcia for a long minute while bees buzzed in my skull. I began to feel a little sick in the stomach myself; maybe that fee of five hundred wasn't so much after all.... She stared back unblinkingly at me with those dark, glittering eyes of hers.

Finally I said, "You're after Walters' invention—but I don't see why. You seem to have more money than you know what to do with right now."

She nodded. "I've got all the money I want. What I intend to do with Walters' invention doesn't concern you."

"Sounds screwy to me," I said. "If you're backing Walters, you're part owner of the gadget. Why've you got to do away with him?"

Marcia's face remained inscrutable. "I'm going to use his apparatus in a manner he wouldn't approve of."

"For crying out loud, what the devil is this contraption, anyway?"

"You heard what he said."

"You mean that crazy spiel about making atoms of stuff and then putting them together again? Hell, that doesn't make sense!"

Marcia sat up straight. "It doesn't have to make sense to you!" she snapped. "You're getting five hundred for a job—that's all that should concern you."

"That's just it!" I wailed. "I don't like ill"

Marcia's lips curled. "I had you spotted for a masher when I picked you up this afternoon, but I thought five hundred would hold you down—well, I'll give you six hundred, and not a cent more. Remember, bums pass through Crestview every day."

"That's what I mean," I said. "Why pick on me? You've got plenty of gorillas around here. Why don't you have one of them do your dirty work?"

"Stupid! How can they pose as a doctor when everybody in town knows them, not to mention Walters himself? And Walters must be killed so skilfully that even his daughter won't become suspicious of us."

Again I stared at this streamlined, dark-eyed bundle of femininity opposite me. She was beautiful, all right. But hell, a snake has dark eyes and is streamlined, and is beautiful—after a fashion.

"Suppose," I mumbled, "that the hypo Walters gets jabbed with isn't—ah—enough to put him to sleep permanently?"

"Oh, but it will be," she answered smoothly. "You'll see to that."

"Yes?"

"Yes."

I took a deep breath and thumped my chest with both hands.

"Ah! I hear the call of the open road. I think I'll travel."

MARCIA smiled thinly. "I don't ¦ think so. Not unless you want to leave some dark night—feet first. You know too much now. I have two ways of silencing you, though. One is to make you go through with your job; you won't dare talk then.

"The other way is for my boys to take care of you—and it won't be by an overdose of dope, either. No one in this town knows you're here; no one would miss you."

"Marcia," I said, "you sure talk a convincing argument. Fact of the matter is, I'm beginning to see your point. Anyway, I can use that six hundred bucks!"

Well, that's the way matters stood for the rest of the day. Marcia and I had a very cozy little supper together—to which I did full justice, because I intended it to be the first and last I'd have in this place. Then, about eleven o'clock, Marcia retired. I took the hint and went to my room, shutting the door loudly behind me.

I moved around for a few minutes, opening and closing drawers and making a lot of noise in general. Finally I shut off the light and plopped heavily on the bed, as though I'd retired.

I waited an hour or so after the household had quieted down. Then I tiptoed to the window and peered out. Starlight touched objects in the yard with a faint silvery glow, high-lighted old Walters' domed laboratory and the little bungalow where he and his daughter lived.

The intervening lawn was a pale silver sheet, and bushes and shrubs were patches of light and darkness. I watched for ten minutes; not a light showed, not a thing moved.

So I unhooked the window screen, straddled the sill and eased myself over. My room was on the second floor; and in order to lessen the distance of the drop, I hung onto the window ledge, let my feet dangle. I let go.

There were bushes below, but I landed between them in some freshly worked earth, making hardly a sound. Of course, as I straightened up, I was still facing the building. There was a big crystalloid window in the wall, and in the window, almost eye to eye with me, was a face looking out; a woman's face, exotically beautiful there in the darkness. Marcia Koch.

"Nice night for a walk, isn't it?" came her voice as if from a distance.

Nose to nose, we measured each other. But she was on the inside and I was out.

So I said, "You're damned right— and I'm walking!"

I swung around on my heel, started to take a step. It was then I made a dynamic discovery—the husky gardeners were still on the job. At least, I supposed them to be gardeners, because one rose from the bushes on either side of me with water hoses in their hands. Each of the men grabbed an arm.

"Goin' some place, Bud?" one asked.

I nodded my head. But when my throat finally decided to work, a weak "no" came out.

"Now that's damned clever figuring on your part," avowed the other gorilla. "'Cause if you had been goin' some place, we might have gotten rough— somethin' like this—"

He lifted up his arm that held the water hose, and then I made a second dynamic discovery. The hose was only about two feet long. It landed with a thud across my kidneys. I got half a yell out when the other man hit me in the stomach. I doubled up, gasping for air.

Then the boys started to go to town with their rubber hoses. I would have pitched forward on my face if they hadn't held me up by the arms.

Somewhere through the roaring in my ears I heard Marcia's voice saying,

"Don't use your fists—we don't want any marks."

I began to get mad. I took a deep breath, jerked my right arm free with a single motion and landed a haymaker on the gorilla's chin at my left. He folded like an accordion. I faced the other guy just in time to catch a glimpse of something coming up under my own chin. The world seemed to explode inside my head.

WHEN I woke up, I found myself tucked very snugly in bed. It was daylight. I sat up and groaned. My jaw ached, my back ached, every bone in my body ached. But there wasn't a scratch on me, save for the shiner Marcia had thoughtlessly hung on my eye the day before.

I dressed and went downstairs, where I found Marcia hard at her breakfast. I sat down stiffly opposite her.

She cocked her dark head on one side and observed brightly,

"There's nothing like a good night's rest to improve one's appetite—is there, Doctor?"

I nodded. "You're right. Guess I've overdone it, though. I haven't got an appetite."

"I'm sorry. Maybe it will help matters if I tell you I've decided to make tonight the night."

"Yeah?" I growled. "Speak up. I'm in no mood to guess at riddles."

Slowly Marcia put down the spoon with which she had been attacking half a Martian muskfruit. Her dark eyes glittered.

"Very well. Your impatient attitude has made me decide to rush matters. Tonight Walters is going to develop a stomach ache. He always putters around in his laboratory after supper, so you'll probably be called there. To make the visit seem casual, you'll go alone."

"Yeah, I know," I cut in. "Then I'll put him out for good with a jumbo hypo."

"Of course. Then you'll pull up one of the window blinds as a signal that Walters is dead. I'll come in, scream at sight of him, and my men will follow.... Oh, there'll be quite an hysterical gathering for a few minutes—for the benefit of Walters' daughter."

"My, you're quite an organizer, Marcia."

She purred, "But that's not all. The town folks will have to have some logical explanation to digest, so you'll announce that Walters' death was the result of a heart attack. And since you are a famous Earth doctor—well, Walters died of a heart attack, that's all. The natives won't think of an autopsy."

"Swell," I nodded. "After that, it'll be easy enough to get rid of the girl, eh? Give her a little money and send her on her way?"

"Prosaically, yes." Marcia waved a negligent spoon. "Simple, isn't it?"

"It stinks."

Marcia's olive complexion took on a little color. She put both elbows on the table, leaned toward me.

"Listen, Doctor," she said acidly, "don't make the mistake of thinking I'm simple too. I've got to have that invention and I'm going to get it, one way or another. This plan is merely the smoothest method.

"So if you're thinking of trying to outwit me by some trick like that sleepwalking stunt of yours, forget it."

I rose to my feet. "Okay, Marcia," I said. "I'll be a good boy. I like little me too well to get bumped off for an old goat like Walters. Don't worry your pretty head."

She looked at me calmly. "I'm not worrying—I don't have to."

She didn't say anything further as I sauntered toward the front door— anything else would have been an anticlimax!

OUTSIDE the sun was shining and the Martian hooting birds were hooting and the gardeners were busy rummaging around in the bushes. I ambled around a little while, and one or two of the gardeners were always doing stuff close behind me.

I contemplated nature, did a few turnabouts around old Walters' bungalow. Finally the luscious little blonde came out. She made a beeline for me.

"Gosh, I'm glad I saw you, Dr. Pfaf—uh—Doctor," she said, falling into step with me.

"Yes?" I encouraged.

She shot a glance over her shoulder at the gardeners, then looked up at me with anxious blue eyes.

"I wanted to talk—" She broke off. "Why, Doctor! Your eye is black! What happened?"

That caught me off guard. "Uh—I tried to get warm over a stove but it was cold—plenty cold."

Lucy frowned. "I don't think I quite know what you mean," she said.

"Skip it. It doesn't matter anyway. Now, what'd you want to talk to me about?"

She eyed my eye and was a picture of indecision.

"Oh, I don't know what to do! I've got to have someone I can trust, someone who'll advise me. I made up my mind yesterday to ask you because doctors are generally honest. But now I don't know.... There seems to be something strange going on around here—"

I slipped my arm through hers.

"Lucy," I said huskily, "a doctor holds the confidences, of others as a sacred trust. Their secrets are his secrets, no matter about what or whom—"

I slid my arm from hers, slipped it comfortably around her waist.

"I want to help you, Lucy."

Her big blue eyes studied me perplexedly.

"Go right ahead," I urged. "What's bothering you?"

She looked at the ground and fidgeted a little.

"It sounds silly, I suppose," she whispered, "because I can't quite tell what is the trouble. I just sense an undercurrent of danger in the atmosphere around here.

"Everything has gone nicely since we've been here, and Miss Koch has been wonderful to us—but I just can't force myself to like her, that's all. For the last few weeks I've felt a growing tension. Call it intuition, anything, but I just know something terrible's going to happen.

"It's almost like"—she sent her big blue eyes gazing up into mine—"like our very lives were in danger. Like, maybe, somebody was going to kill Dad! But that's all foolishness—isn't it, Doctor? There couldn't be any excuse—"

My arm became so weak, it dropped from around her waist.

"Just a case of nerves," I said. "You're upset; been working too hard."

"Oh, but I havent! I don't do anything!"

"Okay, then. You've got too much time. Nothing to occupy your mind."

Doubt puckered her brow, but she nodded her head anyway.

"I suppose so," she admitted. "But I know it's not all imagination. The gardeners, for instance. Haven't you noticed how they follow you around almost like guards?"

I tried to chuckle reassuringly, but all I managed was a hoarse crackle. Then I got a brilliant idea.

I cleared my throat like a high-priced professional man.

"Lucy," I said, "in cases like these I find that all that is needed is an antidote; something to neutralize the fear and the uneasiness in the mind. Uh— your father has a pistol, of course?"

She searched my face wonderingly. "Why, yes. He's got one in the house somewhere."

"Fine. The very next time you go into the house, I want you to get that pistol and put it in your pocket. Put a handful of shells in your pocket too. That's my prescription, Lucy. You'll be surprised at the confidence and the ease of mind that pistol will bring."

Lucy's lips smiled beautifully. "I guess I needed somebody like you to talk to. I feel better already. You don't know what this means to me!"

I waved a negligent hand. "Forget it. I feel better about the whole thing myself." I slid my arm around her waist again.

I saw, now, that we had walked to the door of Walters' laboratory.

"What about your Dad, Lucy? Is he suspicious of things too?"

"Oh, no! He's been too busy to think of anything but has invention."

"Better not tell him, then," I remarked sagely. "Uh—can he take things apart and stick 'em together again pretty well now?"

"W-e-l-l," said Lucy. "He can do it all right, but not like he planned. He's going to try it again in a few minutes. Want to see how it works?"

LUCY opened the door, and into the laboratory we went. The big transformers were humming nastily, filling the air with tension. I followed gingerly behind Lucy and we went across the clearing to the big switchboard.

Old Walters stood there muttering under his breath. His frosty eyes focused instantly on me and he looked unhappy about something.

"Ah—it's you, Dr. Pfaffinger," he said. He shook his finger testily. "If you think you've come here to make an invalid out of me, you're mistaken!"

I snorted suavely. "You're thinking of that physical check-up I was supposed to give you. Well, it's off—definitely. I just dropped around to watch you tinker with atoms."

That unruffled his feathers a bit. "Good." He cocked an eye at me. "Are you by any chance interested in physics?"

"Not a bit," I assured him. He rubbed his hands together and beamed.

"Fine! Then I'm sure we'll get along quite nicely."

"Certainly," I vowed. "But"—I jerked my thumb at the growling transformers—"it seems to me you got a lot of juice tied up in those things. If you'd happen to get your wires crossed—"

"My dear young man!" he exclaimed. "I have only nine hundred thousand volts available. I need millions of horsepower—millions and millions!"

He turned on his heel and started toward a spiral steel stairway leading upward. I followed him.

He stopped a moment, shot a sizzling glance backward.

"Lucy," he rasped, "you stay right where you are. I can take care of things all right by myself."

Lucy was sitting at a writing desk near the switchboard.

"Yes, father," she said meekly.

He started up the narrow steps. We were halfway up when he stopped and turned around to face me.

"Young man," he whispered hoarsely, "it's dangerous up here, and it's narrow and crowded."

I waved my hand. "Don't apologize, sir. I'm used to roughing it."

His cheeks puffed up so large that for a minute it looked like he was going to try to blow me back down the stairs. But instead, he turned and bounded upward.

We came out on a sort of mezzanine floor located up near the level of the laboratory roof; a kind of shelf about sixteen feet square. Above this yawned the inside of the dome. A lot of giant tubes and other electrical apparatus were crowding the place. In the center, fixed on an equatorial mounting, were a couple of big complicated tubes pointing up toward a slot in the dome.

"Looks like a telescope," I observed.

Walters shot me a stiletto out of each eye.

"Confound it, young man," he exclaimed, "it is a telescope!"

"What've you got two tubes for then, sir?"

"One is a telescope, the other is my atomic transporter."

HE turned his back on me and began fumbling with the telescope controls, jockeying the thing around and aiming it up into the sky through the slit in the dome. I leaned over his shoulder and squinted along the tube. There was a wonderful expanse of blank blue sky up there.

"I don't see anything," I complained.

"But it's not night!" he protested. "You see, I'm aiming my atom transporter at Earth. I'm going to try to pick up something on Earth, break it into its primordial atoms, whisk them up here to Mars and then assemble them to their former shape in the converter down on the laboratory floor.... Now please let me do my work, Dr. Pfaffinger," he added testily.

He yanked down viciously on a lever, and I thought for a second that lightning had hit the dome. There was a crash of sound and a glaring of light and a sudden protesting snarl from the transformers down on the lab floor. But I quickly saw that it was only Walters' gadget doing its stuff.

A pale beam was coming from the cylinder above the telescope, shooting up through the opening and into the sky. Then Walters pushed back on the lever and everything subsided.

The old goat brushed eagerly past me, leaned over the platform railing and shouted down to Lucy.

"Did it work? Did I get something in the converter?"

Lucy was still sitting on the desk. She didn't get off, she just glanced over at something I supposed was the "converter" and shook her blond head.

"No," she said. "Not a thing."

I clucked my tongue on the roof of my mouth.

Walters spun around to face me. "You think my invention won't work, Dr. Pfaffinger? Well, it will! If I had more power, I could pick up objects on Earth and transport them up here quicker than you could ever imagine!"

"Take it easy, Dad," I soothed. "I didn't say anything."

"I see that I must demonstrate further!" he said.

He wheeled back to the telescope, swung it downward toward the distant Martian landscape. He squinted through the eyepiece and moved the controls slowly. In a few minutes he said,

"Ah, here's a good subject! Now—"

I crowded up and put my eye to the lens. There was a view of the rusty desert sand, a few stunted bushes, and then the thing Walters bad probably referred to—a kangarabbit, one of those small Martian animals that look like a cross between a kangaroo and a rabbit.

It was munching contentedly on one of the plants.

Walters' eyes were triumphant. "Now," he said, "I will demonstrate! That kangarabbit is about ten miles away, but I'll have it here in a jiffy. Please go downstairs and watch the converter."

Well, I thought maybe it wasn't such a bad idea at that; Lucy looked lonesome down there all by herself. I clattered down the steps, and just as I got to the bottom Walters cut loose with his gadget. The transformers howled as only transformers can, and the converter burst forth with a blinding light.

The converter, I could see now, was a large metal disk set in the floor, with a similar one suspended about ten feet above it—something like huge flat electrodes. Between these two the flames played for an instant.

And then I blinked. There, resting suddenly on the bottom plate, was a goodly portion of red Martian sand, a bush—and a kangarabbit eating the bush. Abruptly the animal became aware of its surroundings and gave a mighty leap that carried it out of sight behind a transformer.

Old Walters' palely excited face beamed at me from the platform.

"Well, sir!" he exclaimed.

"I think you've got something there, Dad!" I yelled back. "You're going to give the spacelines between Earth and Mars a little competition, eh?"

He waved a hand. "Competition, young man! There just won't be any spacelines when this equipment is fully developed!"

I went over and sat with Lucy on the desktop. Stuff was buzzing around in my head. Old Walters really had something there, all right. If more power would turn the trick, would whisk things from Earth as easily as that kangarabbit had been snatched—wow!

The old duffer could build a similar apparatus on Earth to grab things from Mars, and then with a transportation system like that he'd soon be the richest person that ever lived. Marcia Koch would get a big cut on the profits, of course. But the catch was that Marcia didn't want the money. She just wanted the invention itself, for some secret use. And I was being forced into killing Walters so she could get it—Well, it didn't make sense.

Absently I began to put my arm around Lucy. But she hopped off the desk and there was just the slightest hint of reproach in her blue eyes.

"See what you've done now," she said.

I looked around in bewilderment. "Gosh, what? Did I make a mistake of etiquette?"

Lucy pointed at the pile of sand on the converter.

"That's what you've done," she said. "You've made Dad materialize a lot of sand in here—and every time he does that, he makes me shovel it out!"

"Okay, okay. I'll help you."

I started to get off the desk, but just then my eyes lit upon the newspaper Lucy had been sitting on. It was the Crestview Daily Bugle, and the black headlines rose up and smacked me right in the face:

U.S. ARMY POST HERE TO BEGIN

TESTING NEW MECHANIZED EQUIPMENT

Nothing startling in that headline, of course. But it struck a responsive cord in my skull. I stared and stared, my eyes fascinated by the word "Army." Things were clicking into place now. It was pretty clear. Marcia Koch's actions made sense — damned potent sense I Key to it all was "Army."

Marcia could be only one thing—an operative of the United Fascist States of Europe. And if that was so, the possibilities were terrific!

This ruthless dictatorship had long cast greedy eyes at Mars, but had never dared tangle with the great American space fleet guarding the red planet. Well, with a gadget like Walters', they could secretly land a tremendous army, in almost no time, overrun the American outposts on Mars with no trouble at all, and that would be that.

The American space fleet, with its operating base snatched from under it, would be about as effective as a popgun against a steel wall. The plan was simple, it was practical, and had every chance of success!

I felt sick in the stomach. In fact, I felt sick all over.

I helped Lucy shovel out the sand, and I must have looked pretty green about the gills as I was doing it. Finally she said,

"Don't you feel well, Doctor?"

I tried a nonchalant laugh. "It's nothing; just my head giving me a little trouble."

Hell, what else could I say? I couldn't blurt out:

"Lucy, you'd better not let your Dad drink his coffee tonight—because if he does, he's going to get a stomach ache, and then I'll be forced to come over and kill him."

No, I couldn't say that. Walters was going to be killed by someone—and if that someone wasn't me, I'd be killed too! Either way, Marcia was going to win, and Mars would suddenly find itself in the grip of the terrible United Fascist States of Europe.

Yes, my head was giving me a little trouble. It was grinding like a buzz-saw minus a couple of teeth!

I took Lucy's hand, patted it.

"I've got to go now," I said. Her big blue eyes looked a little wistful.

"Gosh," she whispered, "it gets awfully lonesome here with only Dad to talk to—"

"Oh, I'll be back—you can count on that! And Lucy—don't forget what I said about that pistol. Nothing like one to jack up the old morale."

She flashed me a smile. "I'll remember, Doctor!"

MARCIA KOCH was waiting for me when I entered the parlor of the mansion. She sent her dark eyes coldly over my frame.

"I understand you've been visiting Walters. I suppose he performed for you?"

I nodded. "And how! That transportation act of his will really bring down the house. In fact, it'll bring down most anything—including troops, for instance."

Marcia stiffened. "Just what do you mean?" she snapped. Her voice was dangerously hard.

"I mean, I've tumbled to your little game, Marcia. You and your gardeners and butlers are operatives of the United Fascist States of Europe. After you get rid of Walters, you're going to get more electricity and use his invention to bring soldiers up here and capture Mars."

Marcia sank back into her chair. Her eyes played over me speculatively.

"Apparently," she purred, "you can put two and two together better than your appearance would indicate. Or"— her voice became hard again—"did Walters help you?"

"Huh!" I grunted. "What kind of a dope do you take me for? Walters would have to know he was going to be killed, to make him think along those lines. You didn't think I'd tell him I'm going to polish him off tonight, did you?"

"I don't know," mused Marcia. "It's rather hard to tell what you'll do. Or should I say, what you won't do. So I think it's better for all concerned that you stay in your room until you are called this evening."

Well, I stayed in my room, all right—because the door was locked and because a couple of gardeners were fixing bushes all day under my window.

Finally, about an hour after the short Martian sunset, Marcia came in with a couple of butlers crowding close behind her.

"Lucy has just come for you, Doctor," she said calmly. "Her father isn't feeling well."

I didn't say anything.

"Here's your kit," Marcia went on, pushing a small black satchel into my hand. "And remember—after you've tended to him, raise one of the window shades. As soon as I see it's up, I'll come over and put on my act. Is that clear?"

"Sure, sure," I growled. "I get you." I started to push out of the door.

Marcia's voice stopped me short. "Just a minute, Doctor!" She stepped in front of me and her eyes were frigid. "I want to be sure you do understand. Someone is going to die tonight—if it isn't Walters, it will be you. Remember that!"

I remembered. I remembered so well I couldn't think of anything else as I walked with Lucy to the laboratory. She had her arm through mine this time, hanging onto me desperately.

"Gosh, I'm glad you're here," she breathed. "I know you'll be able to fix Dad."

Croaking noises came out of my throat. That was all.

We reached the laboratory then, and ambled past the junk edging the clearing. Walters was sitting doubled up at his desk by the switchboard. His face was beaded with sweat and the bags under his eyes had dropped until they were pouches.

"Glad—you came, Dr. Pfaffinger," he gasped. " I have a very painful stomach ache."

I PUT down my satchel on the desk and looked at Lucy and Walters. They both looked at me. Sweat began to pop out on my forehead.

Walters looked up at me with agony making his face gray. At that, it was a toss-up which of us was the sicker.

I clasped my trembling hands behind my back and took a professional stance. I opened my mouth to say something, but not a sound came out, not even a croak. Desperately I lunged for my satchel, yanked it open.

Maybe there'd be something in it— pills, perhaps—with which I could stall Walters off for a while until I'd collected my wits. But there wasn't. The valise held only two objects — significantly enough, a big evil-looking hypodermic needle and a stethoscope.

Walters eyes fastened on the needle.

"What—what is that?" he groaned.

I waved my hand weakly. "Nothing," I squeaked. "Just a—a hypo."

"Well, administer it, please. I've never had such pain in my life! It—it's killing me!"

Killing him! God! That ill-chosen phrase turned the sweat on my forehead to beads of ice. I got the hypodermic needle out of the bag, but my hand trembled so much I could hardly hold it.

"You look ill." Lucy squinted troubled blue eyes at me. "Is your head bothering you again? You look a little green—"

That gave me an idea.

I wailed, "It's thumping like the devil!"

I lifted my hand toward my head, and as I did so I purposely dropped the hypodermic needle. Its glass cylinder shattered on the concrete floor, spilling the potent contents.

"Oh, God!" Walters moaned, holding his stomach. "Get another one. Get some morphine. I can't stand this much longer!"

Blood began to circulate once more through my veins. Well, that was one crisis postponed!

"No more medicine, sir," I told him. "But you'll be all right in a little while, I'm sure. Probably just something you—er—drank. If that's the case, the thing to do is—uh—remove the source of the trouble. And since I don't carry stomach pumps around with me—well, a couple of fingers jammed as far down one's throat as possible is very effective."

He gazed up at me with blurry eyes.

"All right, all right—anything!"

Lucy and I got on either side of him and pounded his back as he leaned over and gagged. Sweat rolled off his contorted face. Finally he straightened up.

"It's hot in here!" he gasped hoarsely. He ripped off his tie. "I'm suffocating!"

I didn't see what he intended to do until he'd almost reached the window. The shock of it nearly lifted me out of my shoes. I landed between him and the window.

"Oh, no, you don't!" I gulped. "You don't touch this!"

Surprise stopped him for a moment. Then something of his old gusto twisted his wrinkled face.

"Confound you, man! I'm burning up! I need air!"

"And get pneumonia? Oh, no!" I turned toward Lucy. "Can't you do something, Lucy? Your father—"

He was past me in a flash. The window shade snapped up, spun madly on its bearings. I jumped for the cord like a ball player after a high one. I missed.

But old Walters didn't. I was still up in the air when both his hands caught me in the stomach. By the time my feet touched the floor, I was going backward. I kept on going backward until the base of my skull contacted very smartly with the concrete floor. Then through the fireworks I saw the old goat bending over me, wagging a scrawny finger in my face.

"You think I'm blind, eh?" he demanded fiercely. "I'm onto your game, Pfaffinger. I doubt that you're a doctor; you don't look intelligent enough! More likely you're an impostor who has duped poor Miss Koch. Why, you're just an adventurer after my invention. Oh, I've been noticing you, Mr. Pfaffinger!"

I wasn't listening. I was too fascinated by the horrible sight of that raised curtain. I couldn't tear my eyes away. The damage was done now!

I sprang to my feet, pushing Walters out of the way. Lucy stood on the sidelines, a perplexed frown on her ova! face. I grabbed her hand earnestly.

"Listen, Lucy," I panted. "We've got to get out of this dump, all three of us. There's going to be a female ghoul after my blood in just about two seconds! After I'm done away with, there's no telling what'll happen to you!"

Lucy's free hand fluttered to her mouth.

"You—you mean Miss Koch?"

"Right! No time to explain. But if you brought that pistol like I said—"

A sound cut off my words, sound of a door opening. My head swiveled around. There, framed in the doorway, was Marcia Koch. The surprise on her face didn't last long. I could see her stiffen, and her eyes began to glow like freshly lit forges.

All she said was: "So."

But the word and the deadly calm of her voice told me plenty.

Then she turned and called into the darkness outside.

"Boys! Come quick!"

Feet thudded near. I jolted to life and got to the door just as a mob of the gardeners did.

"Get him!" Marcia snapped at them. The nearest reached for something in his pocket. It wouldn't be a rubber hose, I knew that! I let him have a haymaker that picked him up, tumbled him back onto the others.

Then I yanked the door shut so swiftly that it scooped up Marcia and hurled her bodily out. Luckily the key was in the lock and I twisted it home.

Instantly an avalanche seemed to bang up against the door, but it held. Marcia's voice was raised shrilly.

I turned to where Walters and Lucy stood. Walters' scrawny frame was shaking as if some engine inside had come loose. It wasn't from fear, oh, no! It was from anger. At me!

"Pfaffinger!" came his bitter protest. "You can't get away with this! If you unlock that door now and give yourself up, Miss Koch and I will see that the authorities aren't too hard on you. Kidnaping and attempted robbery is a very serious matter...."

"You," I snapped, "shut up! You don't know what it's all about!"

I turned to Lucy. "The gun, Lucy—did you bring it with you?"

She gave a quick nod of her blond head and the next instant was thrusting a small pressure-pistol into my hand. Her blue eyes were large and frightened, and she looked like she needed comforting. I felt so good at that moment that I was on the point of tending to the comforting. Lucy trusted me!

But just then I became aware that old Walters was no longer with us. I spun around in time to see him fumble with the lock on the door. A howl like a factory whistle ripped from my lips. I jumped for him.

He gave me a triumphant grimace and flung open the door.

THE light revealed the gorillas outside, frozen tensely on the threshold.

"Miss Koch!" yelled Walters. "It's all right now—"

The gardeners caught sight of me bearing down on them with a pistol in my hand. Flame belched from their guns. They were rattled. A couple slugs snarled past me, and then old Walters uttered a squawk, twisted half around and fell forward on his face.

I gave a single quick squeeze on the trigger of the pressure-pistol. Two of the gorillas tumbled backward into their pals. I slammed the door, locked it.

Lucy had run up. She threw herself onto her father.

"They've killed him! They've murdered him!" she shrieked hysterically. "Oh, I knew it would happen. I just knew it!"

"Take it easy, Lucy."

I put my hands under her arms and dragged her away. Then I turned the old goat over on his back, ripped open the smock. Blood oozed out of a ragged hole in his left shoulder. It wasn't near his heart and it didn't seem to have hit a bone. The only reason I could see for his being out cold was the egg-sized bump on his skull, where it had smacked the floor.

"Nothing much wrong with him," I told Lucy "professionally." "He'll be okay in a little while."

She started to laugh and cry at the same time, so I pushed the gun into her hand and growled:

"They're not through with us yet. Watch the door and windows. If they start something, shoot. I'll tend to your Dad."

I carried Walters over by the switchboard, stretched him out, on the floor and bundled my coat under his head. His eyes opened then and he blinked stupidly for a moment.

"Easy there," I husked. "Lie still, don't try to move. Relax your arm."

"They—they shot me!" he groaned incredulously.

I nodded. "Yeah. But don't move, just stay the way you are. I'll tend to you."

Well, that kept Walters from getting in my way. So I went behind him where he couldn't see me and sat on the desk. I had some thinking to do.

We were in a hell of a spot, all three of us. The mob outside had seen Walters fall with a bullet in him. And that fact changed matters considerably. It automatically put an end to Marcia's plan of passing his death off as a heart attack. Now the only way remaining open to her would be for her gardeners to kill him. Of course, if they did that, Lucy would have to be included too, to keep her from talking.

Then Marcia would face the problem of explaining the disappearance of so well known a person as Walters. She might do it by leaving all three of our bodies in the lab and setting fire to it, then say we were "trapped."

Again, she might simply pull stakes and vanish to some other part of Mars, where she could use Walters' invention effectively. In any event, the present set-up would cause her a lot of trouble, but she could get away with it.

So all I had to do now was save my own life and Lucy's and the old duffer's as well. I had to do it quick, or that pack of wolves outside would be coming in.

SOMEONE knocked on the door for attention.

"You in there, Doctor?" came Marcia's voice. "If you come out right now, we'll forget all this happened and you can go on your way. What about it?"

I kept quiet.

Lucy, standing by one of the transformers, with the gun in her hand, looked like she wanted to say something. I put my finger to my mouth. Marcia was trying to trick us, of course; I wasn't so dumb I couldn't see that. Once I was out, she wouldn't have any trouble getting Walters and Lucy.

All was quiet for a moment outside the door. Then Marcia's voice called again. It didn't sound like tinkling bells, either; there was a vicious twang to it that bleached me white as a bone.

"You have five minutes," she called. "If you're not out by then, we're coming in after you!"

I began to get a little sick in the stomach again. God! Trapped like worms under a descending boot. There wasn't even a visiphone in the laboratory—and even if there had been, the five minutes would be up before help could reach us.

I squirmed around on the desk and sweated. Then my eyes lit upon the newspaper I'd seen earlier in the day:

U.S. ARMY POST HERE TO BEGIN

TESTING NEW MECHANIZED EQUIPMENT

I stared and stared at it, and bees began to buzz in my skull. I snatched up the paper, shot my eyes over the accompanying news item. Then I howled. I threw the paper ceilingward and jumped up and down ecstatically. I lit beside old Walters.

"Listen, Dad," I panted. "How do you run your gadget? How do you start it up?"

He looked up and gave me a contemptuous stare.

"Pfaffinger," he husked, "how could a human being sink so low? You try to steal my invention, then hold me and my daughter prisoners. Now you have the infernal gall to ask how to operate my apparatus. Young man, you may go to bell!"

The steam oozed out of me and froze. I had a strong impulse to cry, but I gulped and throttled it down. God! The old goat was as one-tracked as a two-year-old! I had only minutes to get him switched over on a new line— switched, hell! I'd have to derail him!

I took a deep breath.

"Walters," I lied, "I'll have to take you into my confidence. While I actually am a doctor, I'm using that title only as a blind right now."

I lowered my voice. "I have been specially deputized by the F.B.I. to investigate the activities of Marcia Koch. She is suspected of espionage. But I've discovered something that'll knock your ears down.

"She's been planning to kill you and your daughter, and use your apparatus to bring Fascist troops from Europe and grab Mars."

Walters looked up at me while he digested that.

"I don't believe it," he said. I shook my head resignedly. "It doesn't matter what you believe, Walters. I'm thinking of the fate of your daughter and the fate of Mars—their safety depends on operating your apparatus and operating it quickly. As for you, well, I've done everything humanly possible to prolong matters."

His eyes widened. "What do you mean?"

"Well," I said, "it'll be fifteen or twenty minutes, at the most."

"You mean I'm going—beyond?"

I motioned at his gory shoulder.

"Bleeding internally. Your lung. The ballet plowed open the postaxial sacculus which leads directly to the heart. Every indication of telangiectasis periostitis through the epithelium vacuole. The posterior caudal is also neatly prognostic."

I'd been on the scene of a nasty space ship crack-up once, and the doctors had hopefully speculated on the condition of their patients. I couldn't remember any more of their lingo than that, but it was enough to impress Walters.

He groaned and let his eyes flutter closed.

"You sure, Doctor?"

"I'm afraid so, Walters. Too bad that bullet didn't finish you off right away. Then you wouldn't have to lie there and watch them shoot Lucy down like a dog."

Walters struggled up on one elbow. His eyes flashed wildly.

"Lord!" he babbled. "Are you telling the truth?"

I put a hand on his head and pushed him down again.

"Certainly."

"You're a rascal, Pfaffinger. I—I don't believe you!"

I dabbed at the wound on his shoulder with a handkerchief.

"I don't care what you believe, Walters," I told him for the second time. I passed the cloth casually in front of his eyes, where he couldn't help but see the blood on it.

"But if you want to die peacefully, knowing your daughter is safe, you'll have to tell me how to run your gadget. I can save her then—"

A sudden heavy banging at the big garagelike doors cut off my words. The panels shook violently but held.

"They're trying to break in!" shrilled Lucy from her vantage point.

"Give 'em a shot!" I yelled back, and watched her trembling hand fire the pressure-pistol. The bullet struck up near the door-top, so the hammering didn't stop a bit.

Sweating, I turned to Walters.

"Damn it, man! Are you just going to watch them bust in and kill us?"

He sank back with a groan.

"All right, all right, Doctor. You win. I can't afford to take a chance with Lucy's life. But how my apparatus can help—"

"Just shoot me the dope," I yelled, "and you'll see!"

He banged directions at me and I stood before the big switchboard and carried them out. I pulled levers and twisted knobs and read meters to him. All around us in the laboratory the transformers and tubes came to life.

Walters looked up at me.

"My—my life's work is in your hands now. Go up in the dome, aim the telescope at what you want and pull that lever you saw me use this morning.... And by God, Pfaffinger, I— I'm praying for you!"

The big doors were splitting, beginning to give under the battering-ram blows of the gang outside. I took the steel stairs up to the dome at full tilt. When I reached the platform I leaned over the railing and motioned at Lucy.

"Get out of the way!" I yelled. "Get over by your Dad and stay there!"

THEN I sprang to the telescope and swung it along the shadowy desert horizon. Below, in the lab, I heard the doors splinter sickeningly and give. Lucy's gun barked and there were cries and shouts.

Then through the telescope I caught sight of what I was looking for—the distant war games battleground. I could see the brilliant flares that lit the scene, the exploding ground mines, the swiftly moving tanks, the tracer bullets, and the infantry coming up behind. It was all practice, of course, a test of men and machines. But it would serve my purpose.

I picked out a tank moving in the proper direction in relation to me. I centered the telescope on it, then yanked down the lever that worked Walters' transporter.

Things happened—fast! The whole apparatus jumped into howling life. A pale beam shot from the tube above the telescope, licked out toward the distant battleground. And then suddenly there was a great alien crash of sound down on the lab floor: the roaring of a motor, the metallic clatter of furiously moving caterpillar treads, the staccato stuttering of a thermite machine gun!

I reached the railing just in time to see the tank, fire spitting from its guns, roll across the clearing like an iron boulder and smash through the door where the gorillas were breaking in. Yes, it happened that quick, before the tank driver, surprised at suddenly finding himself in a strange place, could stop his crate; before the gunner could silence his weapon.

It was so blamed simple, I decided not to take any chances. I hopped back to the telescope, and in an instant another tank was crashing through the big door down on the lab floor. I figured that should have pretty well taken the pep out of Marcia's gang.

But just in case there happened to be stray "gardeners" lurking in the bushes outside, I centered the telescope on a platoon of charging soldiers, and yanked the lever. Downstairs sounded the thump of metal-shod feet, lusty battle cries and then hoarse shouts and curses of amazement.

By the time I looked over the railing, soldiers were filling the place like scurrying ants. I shot a glance over at the switchboard where Lucy and her Dad were.

Apparently the old duffer had forgotten the bullet hole in his shoulder, the bump on his head, and the pain in his stomach. He was standing up, jaw swinging like the scoop of a steam shovel. Lucy stood at his side.

But Lucy wasn't looking at the confused soldiers or the spot where our late enemies had been. She was gazing up at me, and even at that distance I could see that her big blue eyes were shining.

I waved my hand. "The Marines have landed!" I yelled. "The situation is well in hand!"

Then I was going down those steel stairs three at a time. In another moment I was at the switchboard, and in another second I had Lucy in my arms....

I felt a tap on my shoulder after a bit, and I turned around to face a perspiring, sarcastic infantry captain.

"If you don't mind," he said, "what the hell is this all about!"

"Just a little game of 'atom,'" I explained. I put my arm around Lucy's waist. "And this is Eve. And over there—"

I took a look around and finally found Marcia, struggling like all seven furies with a couple of burly soldiers.

"Over there," I nodded, "is the snake."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.