RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"The Orange Divan," Herbert Jenkins, London, 1923

IT was a stifling evening in high summer, the hour when, in the green country, there comes that subtle mellowing of the light which presages the stately pageantry of sunset, and by the sea that little stirring of a breeze which atones so generously for the noonday glare.

But in London there was not a breath of air. The lead-coloured sky seemed to press down upon the noisy and restless streets like a hot and heavy hand laid upon the face of the city. Since early morning the sun had blazed fiercely out of an unruffled heaven and now, though the approach of evening had dulled the molten splendour of its rays, it seemed to beat as hotly upon the panting street as it had done throughout the steaming day.

Here in this narrow side-street the sun was not a friend, a joyous companion beckoning the leisurely to the cool swimming-pool or to a stroll in the shade of some leafy grove, but an enemy, a malignant foe, that look delight in embittering still further the life of the very poor.

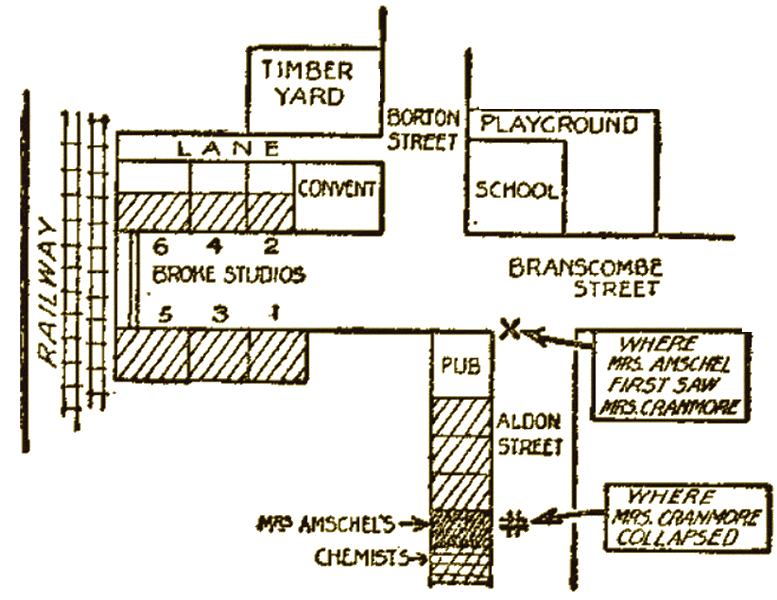

Aldon Street is the dwelling place of humble folk. It lies in that labyrinthine No Man's Land which is wedged in between South Kensington, West Kensington, Earl's Court and Fulham, a slum which through the years has remained a slum while the genteel upon which it bordered slowly sank to the shabby. From time to time, in the long years of the Victorian era, an attempt seems to have been made to raise the social level of the street. At one end the dreary frontage of squalid houses with their crumbling steps and rusting railings is interrupted by half a dozen decrepit villas, each with its strip of black and blighted garden before, the playground of emaciated cats; elsewhere the stucco facade has been unexpectedly broken by a terrace of jerry-built cottages, once of staring yellow brick, but long since endued with the sombre neutral tint which is the colour scheme of Aldon Street.

In point of fact, nothing save dynamite could hoist Aldon Street from its chronic condition of decay. It is merely a rusty link in the chain of streets which lead from the smug respectability of Kensington to the frank slumland of Walham Green. Two streets away, it is true, gentility yet raises its head in Broke Place, a quiet cul-de-sac given over exclusively to studios; but that is merely owing to the curious proclivity of painters to-attach more importance to a good north light than to the antecedents and social status of their immediate neighbours.

Aldon Street is the home of curious trades. Exponents of the art of midwifery, of pinking, of French polishing and of mangling proclaim, by means of brass plates or painted signboards, that their place of business is identical with their residence. There are half a dozen shops, including a greengrocer, a baker, a herbalist, a second-hand clothes dealer and a chemist. At almost every side-turning the corner is neatly rounded off with a public-house. The street can regulate its clocks by the habits of these rather cheerless taverns, by the appearance of the thirsty-looking queue which lines up at midday is by the stentorian cries of "Time, gentlemen, PLEASE!" the scrape of feet and the banging of doors, which proclaim the closing-hour at night.

On this hot June evening Mrs. Rosa Amschel, proprietress of Aldon Street's second-hand clothes store, sat on a kitchen chair at her shop door contemplating the view. The dusty pavements and dirty gutters fairly reeked of heat and the air of the street was laden with uncleanly odours, that blend of dirt, decaying vegetables and stale fish which is the characteristic smell of a London slum. The street was very quiet, so that one could hear the distant boom of traffic from the main-road; no one was in sight except a group of filthy children hocking in the gutter at the far end.

Mrs. Amschel was a large and rather frowsy Jewess with narrow black eyes, rather red about the rims, a thick hooked nose and a big gash of a mouth. She was scarlet in the face with the heat and her dark, frizzy hair, scraped back off her forehead and bundled up in a knob at the back of her head, was dank and untidy. Her enormous bosom bulged loosely in the dirty striped cotton wrapper she was wearing. Her age might have been anywhere between forty and fifty; but like most Jewesses of her class, she probably looked older than she was.

At her elbow the long, shallow window of her shop was filled with sundry soiled and faded articles of clothing, topping a variegated assortment of leather suit-cases, boots and shoes and hats in picturesque confusion. Against the window-pane was gummed a notice which, written in faded ink on yellowing paper, informed the Nobility and Gentry that Mrs. Rosa Amschel paid the Highest Prices for Cast-Off clothing, Uniforms, Jewellery and Teeth and that, moreover, Ladies and Gentlemen were Waited Upon at their Residences by the aforesaid Mrs. Amschel at Any Convenient Time.

Mrs. Amschel was rather an enigma to her neighbours of Aldon Street. In the language of the street she kept herself to herself. She lived alone and when business called her abroad—presumably on those occasions when she waited upon the Nobility and Gentry at their Residences—she locked up the shop and hung on the door-knob a printed notice bearing the convenient and elastic announcement "Back In An Hour." For the rest, as far as customers calling at the shop were concerned, business was not brisk. Mr. Chas. Ruddick, Chymist, as he described himself on his plate-glass window, who kept the chemist's shop adjoining Mrs. Amschel's, was in the habit of declaring that he didn't rightly know how that Mrs. Amschel contrived to get a living.

With a fat hand Mrs. Amschel smoothed the hair back out of her eyes and sighed heavily.

"Ei! Ei! it's hot!" she murmured to herself. First she looked down the street, past the chemist's shop where the afternoon sun was striking all sorts of pretty colours out of the three jars of coloured water which stood in the window and then she looked up the street. And there her gaze remained fixed.

Across the top of Aldon Street runs Branscombe Street which, at its farther end, becomes Broke Place, the cul-de-sac with the studios. Now as Mrs. Amschel looked up Aldon Street towards Branscombe Street she observed a woman turn the corner and hasten down the right-hand pavement of Aldon Street, the same side as that on which Mrs. Amschel's shop was situated. At a glance the second-hand dealer, with her shrewd eye for clothes, saw that the woman, who was young and slim, was extremely well-dressed. Her silhouette which, after all, is the test of present day elegance, was of the most fashionable.

But it was not the appearance of a woman of fashion in those squalid surroundings that made Mrs. Amschel stare so much as the fact that, despite the warm evening, the woman seemed to be in desperate haste. She came hurrying down Aldon Street with every appearance of alarm, her head down, her two arms crossed clutching her cloak across her breast. She walked desperately, unheedingly, zigzagging from side to side in the rather helpless fashion of the average woman who is not habituated to violent exercise.

Her alarm was so obvious that Mrs. Amschel rather awkwardly scrambled to her feet with the intention of retiring into her shop as if she fully expected to see some criminal turn the corner in hot pursuit after the stranger. But, save for the woman, Aldon Street, from Mrs. Amschel's shop to Branscombe Street, was completely deserted. The second-hand dealer stood at her shop-door and waited.

And now the stranger, when she was within a few yards of the shop, raised her head. On catching sight of the Jewess she stopped abruptly, faltered and, clutching at the wall for support, raised dark and lustrous eyes to the dealer's hard and rather uncompromising countenance. Then Mrs. Amschel saw a strikingly beautiful face, oval and olive-skinned, the ears hidden by loops of blue-black hair resting against the cheeks, while through the scarlet lips, parted as the stranger struggled for breath, she had a glimpse of even, dazzlingly white teeth.

But there was an odd, strained look about the regular features and the eyes were staring with terror.

"Du lieber Gott!" exclaimed the Jewess, receding in amazement and oversetting her chair which fell with a crash back into the shop.

"A taxi!"

The words came in a gurgling whisper from the stranger's lips, a scarlet smear in a bloodless face.

"Get me a taxi!"

She raised a hand as she spoke in a little gesture of appeal. As she did so the pleated cloak she was wearing fell back, displaying her beautifully rounded throat, about which a string of pearls was clasped, and the gentle swell of her bosom in a simple black satin frock.

For an instant the dealer remained motionless where she stood, whilst a look of terror deepened in her beady eyes. Her face distorted with horror, she drew back and raised one pudgy hand, with a slow and tragic gesture, to her cheek, her eyes fixed upon the other woman's breast. So the Jewess stood for a moment in a terror-stricken silence, staring with eyes that slowly distended with fear. Then suddenly she shrieked aloud, shrieked again and again, her fat hands, thrust out from her body as though to ward off some terrifying vision, pawing the air in a frenzy of fear.

So Mr. Ruddick, the chemist from next door, found her when, at the uproar, he burst from his shop into the street. He saw the Jewess, who had fallen back against the doorpost of her shop, pointing with trembling finger at the elegantly dressed stranger while scream on scream shattered the heavy air and woke all the squalid street into life. Windows were thrown up; there was the muffled thud of heavy feet on bare wooden stairs; doors slammed; while the stranger, with a wan little smile on her bloodless face and a veiled and distant regard in her dark eyes, stood, swaying a little, silently contemplating the shrieking Jewess. The chemist followed the direction of Mrs. Amschel's pointing finger, then recoiled in horror himself.

In the strange woman's left breast a knife was plunged, the hilt projecting from the black satin corsage.

JIM CRANMORE leisurely mounted the steps of his club. Following his usual custom, when business was quiet, he had walked from the City to St. James's Street and, though he had taken it easy on this warm afternoon, he felt hot and sticky in the conventional clothes of the London stockbroker which, as everybody knows, consist of a very shiny top-hat, a short black coat and what the tailors call "fancy" trousers.

On the broad shallow steps of the club where, in the London of a vanished age, the gilded youth and the old bucks had stood and quizzed their passing acquaintances, Jim Cranmore paused to wipe his damp forehead and, while doing so, to gaze on the habitual stir of the celebrated street. With pleasure he let his eyes rest again on the quiet dignity of the old Regency facades, the trim green corner-posts fashioned out of the guns of the Peninsula and Waterloo, the shining wood paving and, away at the bottom of the street, the sentries in their scarlet tunics on guard outside the Palace. Cranmore liked St. James's Street; it gratified his conservative nature, a perpetual reminder of the immutability of London life.

Of course, Cranmore didn't word it quite like that; for he had not a very extensive vocabulary in his native tongue at his command. He had been brought up, rather than educated, at a famous public school. Thence he had gone to spend three very pleasant years of idleness at Oxford before going into the City to take up a junior partnership in his father's old established and highly respectable firm of stockbrokers.

When the war came Cranmore followed the drum with the same air of quiet reserve with which he had been brought up to go about the business of life. With the same absence of fuss (at least on his part) he had been severely wounded and had spent a year in hospital. It would not be going wide of the mark to say that what had impressed the war upon Jim Cranmore's mind was not so much his temporary transformation from a stockbroker into a soldier as the circumstance that it had brought him a wife. For Jim Cranmore had met Carmen when she was serving as a V.A.D. in the Mayfair hospital to which he was first sent after being wounded.

His wife's face came into Jim Cranmore's mind now as he stood outside the club and took the last few pulls at his cigarette. He thought of her very often, not so much, perhaps, because of her splendid Spanish type of beauty, as on account of the wistfully sweet expression which lay in her big dark eyes and her exquisitely regular features. They had been three years married. They adored each other quite frankly, "though what she sees in me," Jim used to say to his brother, George Cranmore, the barrister, "I'm jiggered if I know!"

The thought recurred to him now, on this warm, still evening in St. James's Street, that he was very happy in the possession of a beautiful and affectionate wife, excellent health, sufficient means to have enabled him to tide his affairs over the difficult war period, and a sound business. Old Cranmore had built up his connection carefully and well and when, towards the close of the war, he had died, he had left his two sons and his daughter very comfortably off.

Jim Cranmore pitched away the stump of his cigarette and walked through the swing-doors into the club. In the hall he came upon his brother seated on the fender, his hat on the back of his head. George Cranmore was, like his brother, dark and clean-shaven, but he was almost a head taller and altogether a leaner and slimmer stamp of man than Jim who, broad of shoulder and thickset, had in his day played full back for the Harlequins and still looked the part.

"Cheerio, Jim!" said George, looking up from the evening paper.

"Hullo, George!" answered Jim as he took some letters from the porter.

"How's Carmen?"

"Grand!" said the other, absently running his eyes over his mail, "grand! You ought to come along and see her! You haven't been around for ages...."

"H'm," observed his brother, "I'm not sure I'm wanted..."

"My good ass—" began Jim, but George interrupted:

"You and Carmen are all right, I know," he said, "It's Dolores I mean...."

Dolores was Carmen Cranmore's half-sister who made her home with the Cranmores.

"My dear old boy," said Jim, "if you're going to make Carmen and me responsible for how Dolores treats you . . Have you two been squabbling again?"

"There was no assault and battery on my part," rejoined George, "much as I was tempted. But words passed! Oh, but she's an independent young devil is Dolores!"

"Bah!" answered his brother. "You young fellers don't know how to treat the girls of to-day, that's all there is to it! Now, look at Carmen and me! Do we ever have a word? Have we ever had a row?"

"My poor fool!" George remarked with withering sarcasm, "do you really mean to say you don't realise even yet that that is none of your doing? Carmen is a saint. She couldn't fall out with an income tax assessor! And anyway you are too fat and middle-aged and self satisfied for the poor girl to pick a quarrel with! But it's different with a fine, upstanding, audacious devil like meself...."

"Shut up, you ass!" cried Jim. "Look here, you can buy me a quick drink and I'll tell you how to be happy though married...."

"It would be far better for your figure," replied his brother, "to come up to the Bath Club and have a game of squash and a swim. And that arrangement will have the added advantage of enabling you to drive me back to the Temple afterwards. Isn't that your car outside?"

"Yes," said Jim. "I told Bartlett to bring it round to meet me. But I can't play squash with you, old boy. I've got to be home by half-past six to dress. I've promised to take Carmen to dine at the Ritz and then on to the new show at the Pavilion.....

"Anniversary?"

"No, domestic crisis! There's no housemaid—Carmen fired the last for wearing her silk stockings—and the cook's mother has picked upon this particular time to fall mortally ill. So as there's only the parlourmaid left and she has her evening off, I told Carmen we'd make a night of it!"

"That's an idea!" exclaimed George. "I haven't seen that thing at the Pavilion either. Suppose I came and took Dolores?"

"Guess again!" retorted his brother. "Dolores has gone to Ranelagh to dine. And if you think Carmen and I are going to stand for a dull fellow like you butting in...."

"Oh, dry up!" said George. "I suppose you and Carmen will sit in a box and hold hands all night like a couple of Cockneys. Come along to the smoke-room. I'll stand you a drink if it's only to stop your nauseous twaddle about matrimonial bliss!"

In the bow-window of the smoke-room they had a Martini apiece. They were good friends, the two brothers, and presently the barrister said with spontaneous warmth:

"Joking apart, Jim, old man, I'm devilish glad you're so happy with Carmen....."

"She's a brick!" replied the other fervently. "I'm the luckiest fellow alive. I honestly believe I've got everything in the world a man can want to make him happy. In the old days I never knew what it was to feel contented ... to feel, well, at peace and all that, don't you know? Things run so smoothly for me that I feel quite scared at times. I wonder whether I oughtn't to throw a ring into the sea or something, like the old josser what's his name one read about at school. I hope you'll be as happy, George, old boy! Carmen did always think that you and Dolores ought to make a match of it....."

"My dear chap," his brother retorted with the utmost promptitude, "forget it! Dolores would no more marry me than... well, I'd marry her! And when she hears that you've been trying to match-make, she'll just give you merry hell!"

Jim laughed.

"Well," he remarked after a reflective sip of his cocktail, "Dolores ought to marry. She's high-spirited and devilish obstinate and all that and wants a man to look after her a bit. But she's a dam good sort and I'd like to see some good chap make her happy!"

George looked at him curiously.

"Perhaps some man will sooner than you think!" he observed quietly.

"I shouldn't wonder. She has plenty of chances. Besides being about the prettiest girl, after Carmen, that I know, she's awfully popular. Wherever she goes she is fairly surrounded by the men. Though, mind you, they're not always the right ones. Dolores has got this modern bee in her bonnet about her 'independence,' 'living her own life' and all that bunkum. She draws the line at no one! She started bringing some of her Bohemian friends to the house till I put my foot down!"

"I met her in Bond Street on Monday," said George. "I thought she seemed a bit subdued."

And again he stole a glance at his brother's face.

"Can't say I notice it," said Jim. "She always seems to be out dashing about..."

George Cranmore laughed.

"What an unobservant bloke you are, Jim," he remarked. "I bet you a new hat that Dolores knows whom she's going to marry. And she'll marry him for all you say. ..."

An obstinate look came into Jim Cranmore's face.

"You mean that fellow Quayre?"

His brother nodded.

"I don't know what you've got against Quayre," he said. "Of course, he's an artist. But his stuff is good, especially his portraits, and he's making quite a name for himself. Of course, he hasn't a bean as yet, I know, but he's really a thundering good chap. And after all he's an old friend of Carmen's. She knew him in America....."

"My dear George, I'm not prejudiced against Quayre in the least and I'm not old-fashioned, either, I think. But it's pretty hot when a girl of nineteen like Dolores comes home time after time from some artist spree in Chelsea or God knows where at three or four in the morning. That was bad enough. But when she brought this fellow Julian Quayre into the house at some unearthly hour of the night to give him a drink, it was going a bit too far. It's not good enough, old man. Dolores has lived with us ever since she left school and she can't play up in this fashion. Carmen absolutely agrees with me. As a matter of fact, though, as you say, she knew Quayre in New York. I'm not at all sure about her being so keen on him. And I can tell you she quite approved of my reading the Riot Act to Dolores about her artistic friends. After her last exploit I sent for Master Julian Quayre and ticked him off properly. I told him he would not be seeing anything more of Dolores and I gave Dolores as well to understand that she was to cut him out. I grant you that Quayre's quite a good fellow, but he hasn't a bean, and Dolores, with her looks and charm and all that, can do better than that. And she'll have a settlement, too, when she marries. I promised Carmen to see to that. But I'm going to take care at the same time that she gets a good husband ..." He looked at his watch.

"Good Lord!" he exclaimed, scrambling to his feet, "it's half-past six. I'll have to sprint if I'm to get to Sloane Crescent, dress and be ready by seven. I never keep Carmen waiting. So long, old man! Ring up and come and dine one night soon, won't you? Can I drop you anywhere?"

No, George said, he'd have a quiet chop and go down to the dormy-house at Wickham after dinner to have a night in the fresh air. So Jim waved a hand to his brother and vanished abruptly through the smoke-room door, alert, confident, content.

Piccadilly was a roaring tangle of traffic as Jim Cranmore's big car made its way among the motor-buses and taxis. He drove himself with the sure touch of a man who is in fine physical and moral condition. His was a placid, kindly disposition, inclined, perhaps, to complacency and dogmatism, but with no leaning to arrogance. He was always happier at home than at the office or the club, and one of his chief joys in life was to return to his Carmen after his day's work was done. Jim Cranmore made no claim to introspective or intuitive powers; but he believed his wife to be in love with him though much less, as he told himself with the modesty which was one of his characteristics, than he was in love with her.

"Mind that lorry, sir, goin' to turn!" said the chauffeur, Bartlett, in his ear.

Cranmore, still busy with his thoughts, gave the wheel a half turn and brought the car nearer the pavement. His three years of married life, he reflected, had been a dream of happiness unclouded. Not a misunderstanding, not a quarrel, never a harsh word on either side. There had been no children, it was true, but that was an omission which time might rectify; besides, he sometimes wondered whether this very absence of children did not perhaps make his domestic harmony more absolute.

In his daily work, in the tumultuous surroundings of 'Change, in the very masculine atmosphere of his club, the living reflection in his mind of his wife's face, the dark sheen of her eyes, the piquant disdain of her short upper lip, the haunting charm of her smile, accompanied him like a silent friend. As the car glided in and out of the stream of traffic, he recalled her, with a thrill of warm affection, as he had left her that morning, seated at her dressing table in the white silk kimono that became her so well, remembered the look of loving kindness with which she had sped him on his way.

She was alone in the house. His fingers drummed impatiently on the steering-wheel as again and again, in the crush of vehicles, he had to slow down the car.

AT twenty minutes to seven Jim Cranmore put his latchkey into the lock of his front door in Sloane Crescent. The door swung back and closed behind him, leaving him in the tidy, oak-panelled hall lit by an old cast-iron lamp. On a big Florentine chest his opera-hat, evening scarf and overcoat lay in a neat pile as the parlour-maid had left them ready before going out.

The house was very quiet. As Cranmore set down his hat and gloves and Malacca cane he heard the solemn tick of the grandfather clock which stood in the staircase recess behind the green silk curtains shutting off the stairs. Remembering that the servants were out, he gave Carmen the call she had taught him, a funny little Spanish call on a rising and falling cadence which they used between themselves when they were alone like this.

"O!—Carmen!" he sang out and waited for the familiar reply to echo back in that soft, caressing voice which always set his heart beating faster: "O!—Jim!"

But there was no answer. A taxi hooted raucously in the street outside and somewhere in the distance one of those long drawn out, lugubrious motor whistles sounded.

"O!—Carmen!" He called out again. "I'm— i-i-in!"

But his voice fell dully on the quiet atmosphere of the house. No response was awakened. All remained profoundly still and there seemed to be something positively aggressive about the ponderous ticking of the hall clock. Cranmore parted the curtains and ran lightly up the stairs. His feet made no sound on the heavy pile carpet. On the first landing he paused and called again. Still there was no reply.

He followed the staircase up to the next floor where their bedroom and his dressing-room lay. But now he stopped short in surprise. The bedroom door stood open and at a glance he could see that the room was empty.

The bed had been turned back in preparation for the night and on it lay Carmen's fine white crêpe-de-chine nightdress, at its foot her little blue quilted bedroom slippers edged with white fur. On the couch at the end of the bed her evening things were spread out, a silver tissue frock, silver slippers, grey silk stockings, a brocade bag.

Cranmore looked round the room in perplexity. It was most unlike Carmen to be as late as this, for if she had not even started to dress they would certainly not be able to dine and reach the Pavilion by 8.15 when the curtain rose on the new revue. The sight of the empty chair in front of her dressing-table, with its array of silver and glass, powder-puffs and other feminine toilet requisites gave him a sudden poignant stab of loneliness.

How empty the house seemed!

Then he decided that Carmen must, after all, be in the drawing-room or the morning-room. She might have fallen asleep, as she sometimes did curled up on a sofa.

He descended to the first floor and pushed open the drawing-room door, but the big, cool apartment was empty. So was the little book-lined library behind it—Jim's den, this—with his desk and a few war souvenirs and his big cedarwood cabinet of cigars. Perplexed, he went on down to the morning-room.

This, situated behind the dining-room which looked out on the street, was eminently Carmen's room. The French window opening on to a vista of smooth green turf in the gardens at the back had attracted her and she had transformed a prosaic back room in a prosaic West End house into something exquisitely beautiful and exotic like herself. The walls were black, the ceiling was golden; and, with the broad divan of flaming orange, piled with great black and golden cushions, the black curtains, the lacquer furniture and the quaint Chinese lamps, the whole bizarre art of the Far East seemed to have brought a blaze of colour to lighten the London gloom.

But Carmen was not there. So permeated was the room with her personality, however, that her husband had to look twice to convince himself that she was not present. In its simplicity, its fragrant daintiness, its serene beauty, the shrine was like the goddess, and in the bizarre note which predominated was something of the mystery which envelops every woman in the eyes of man.

He looked at the orange divan, a low and broad couch with curiously carved Chinese feet in black teak displaying the five dragon's claws, the emblem of majesty in old China. Carmen was romantically attached to this quaint old piece, the only possession she had brought with her in marriage. "My dowry," she used to call it. In her early days of struggle, when she was a poor art student in New York, she had slept on the orange divan in her tiny bed sitting room. Together with a few pieces of modern furniture it constituted the only legacy, except her artistic sense and her Irish-blue eyes, she had inherited from her father, Lucius Driscol, Bohemian, dreamer and free lance, dead these many years in New York. As Cranmore gazed rather helplessly around the room, a great yearning for his wife surged over him. Suddenly he felt a little stirring of uneasiness....

He pulled out his cigarette case and lit a cigarette. His watch showed the time to be five minutes to seven. On a side-table was a morning paper, The Planet. The editor, Harringay, was a member of Cranmore's club and had mentioned on the previous day that they were running a striking series of articles on the economic condition of Germany.

Cranmore unfolded the newspaper and turned to the article in the series in question. It was interestingly written and Cranmore, reading it, became absorbed and perused it to the end. Then, from the clock on the mantelpiece, he realised that it was twenty minutes past seven.

He rose to his feet hurriedly. What was Carmen doing? He was beginning to feel hungry and consequently somewhat cross. Carmen was not a model of punctuality and she made little account of a quarter of an hour one way or another. But there was a certain consistency about her unpunctuality. Yet here forty minutes had elapsed since the time of their appointment and still there was no sign of her.

In a rather irritable frame of mind Cranmore went out to the telephone in the hall and called up Carmen's club. She was a member of the Ladies' Criterion in Bond Street and sometimes went there in the afternoon. On the spur of the moment it was the only place he could think of where he might glean news of her.

Yes, said the club porter, Mrs. Cranmore had been to the club and had had tea there. She had left about half-past five.

Had Mrs. Cranmore said where she was going?

He couldn't say.

Did she say she was going home? He didn't know.

"Damn!" said Cranmore under his breath as he put the receiver down. What a nuisance women were about the time! He felt aggrieved. He lit another cigarette and stood in the hall fuming and indulging his sense of grievance until he suddenly realised that he was giving way to this feeling of irritation to still the small, quiet voice which, as methodical as the tick of the grandfather's clock, kept telling him that perhaps something had happened to Carmen.

Perhaps Carmen had unexpectedly decided to go to Ranelagh with Dolores. Jim didn't know the name of the man who had taken Dolores to dinner. Still, he would try Ranelagh. He spent a quarter of an hour in futile telephoning, including several minutes of vain recrimination with a hysterical voice that clamoured for the National Institute for the Blind, only ultimately to find that nobody at Ranelagh knew anything, about either Miss Dolores Driscol, Mrs. Cranmore, or their escort. Then he rang up George at the club; but the porter informed him that Mr. Cranmore had left for Paddington a quarter of an hour before. As Jim put back the receiver eight o'clock struck from the neighbouring church tower.

His car was still at the door. The chauffeur, consulted, could throw no light on the question of Madame's movements. He had driven the car straight from the garage to the club and had not seen Madame all day. Nor could he say where the parlour-maid was to be found.

Jim Cranmore stood for a moment in perplexity at the front door. Then on the back of a circular which he found lying on the hall chest he wrote a line for Carmen saying he had waited until eight o'clock and had gone in the car to the Ladies' Criterion to find out what had become of her. If she came home while he was away would she wait for him? He propped the note up where she could not fail to see it and drove off in the car to Bond Street.

In half an hour he was back again. At the club he had learnt little more than the negative information he had already gathered. A little red-haired waitress in the lounge remembered Mrs. Cranmore having tea by herself. She was wearing a small black hat with a white osprey, a string of pearls and a blue serge cape. She had left in rather a hurry about: twenty minutes past five. The girl recalled this circumstance because the lady had asked her to make haste with her check. Cranmore interviewed the lady secretary and with her aid tried to discover any member who had seen or spoken to Carmen, but without success. Only a few members were in the club and none of those present had been there when Mrs. Cranmore was in.

The house in Sloane Crescent was exactly as Cranmore had left it. The windows were all dark and in the gathering dusk in the hall the first thing he saw was the note to his wife lying undisturbed on the chest. At the front door Cranmore turned and bade Bartlett wait. Then he entered the silent house and closing the door, shut out the sounds of the street.

He was fighting down a feeling of panic. Even without the evidence of the clock, of the empty house, he was virtually certain that something untoward had happened to his wife. For a full five minutes he stood in the hall, his hands thrust deep in his pockets, his brow puckered, a look of anxiety in his honest eyes, while the invisible clock inexorably, ponderously ticked the time away.

At last he raised his his head with a jerk and squared his chin. He went to the telephone, consulted the directory and called up a number. It was The Planet office. Cranmore asked for the editor. Then Harringay spoke. His voice was tired, his manner abrupt. It was obvious that he was busy.

"Is that you, Harringay?" said Jim. "Look here, I'm anxious to see you...."

"Yes," said Harringay in a non-committal manner. "Come and lunch one day.... wait a minute, what about Thursday?"

"No, no,"—Cranmore tried to steady his voice—"it's important. I must see you to-night....."

"I'm sorry, but it's quite impossible. I'm fearfully rushed....."

"Harringay," urged Cranmore, and his voice was low and pleading, "I'm in a hole and I want your advice. I shan't keep you a moment. But it's urgent, I have my car here....."

"But couldn't you tell me on the telephone?"

"Out of the question! I shan't keep you five minutes!"

"Oh, all right!" was the resigned reply, and the editor rang off.

In a plainly furnished room with a double door which shut out the clatter of typewriters, the whirr of telephone bells, the thudding of pneumatic tube carriers and the trampling of office boys on the stairs, Harringay gave Cranmore his hand and pointed to a leather chair opposite him across the desk. The room was illuminated only by the green-shaded reading-lamp which threw its rays down on the desk with its letter-trays and litter of damp proofs.

"Well, Cranmore," said the editor, "what can we do for you? Let me see, you're looking a bit off colour, aren't you?"

"It's very good of you to let me take up your time in this fashion, Harringay," said the other. "I want your advice. It's about my wife....."

The editor's eyes narrowed a trifle and he drew back in his chair as though to take a better view of his visitor. But he said nothing and Jim Cranmore continued:

"She was to have met me at home at half-past six to dine and go to the play. But she hasn't turned up. And I don't know where she is....."

The editor, his left hand propping up his chin, was looking at his visitor thoughtfully.

"Mightn't she have gone to friends?" he asked.

Cranmore shook his head vigorously.

"If she had," he answered, "she would have kept her appointment with me or let me know that she was delayed. As a matter of fact she doesn't go out a very great deal and has few intimate friends. I was with my brother this afternoon and he hadn't seen my wife for a week. And my sister, with whom she is very friendly, lives down in Hampshire."

He looked about him in a perplexed fashion.

"I don't know where she is," he repeated. "Such a thing has never happened before. There is probably a perfectly natural explanation. But, frankly, I don't know how to act. I don't care to go to the police.... it seems like making a fuss about nothing. But it's nine o'clock... and I'm... a little... anxious...."

There was a moment's silence in that quiet room which, before Big Ben tolled midnight, would reverberate, with the rest of the building, to the roar of The Planet's presses. Then the editor stretched forth his hand and pressed a button affixed to the side of the desk on a level with his knee. The rather reserved manner with which he had received his visitor had now given place to an altitude of marked interest.

"Tell me more about it!" he urged.

The stockbroker explained how he had come home to an empty house and waited in vain for the return of his wife.

"And you've no explanation?" queried Harringay.

There was a rap at the door and a liveried page appeared.

"Mr. March!" said the editor over his shoulder to the page. Then, turning to Cranmore, he continued:

"There was no trouble at home, or anything like that, I suppose?"

Jim Cranmore looked down at his hat, which he turned over slowly in his hands. His eyes were bright when he gazed into Harringay's face and answered.

"Neither of us had a care in the world," he said earnestly. "We've always been very happy together, and if you're suggesting that there's any skeleton in the cupboard, any scandal behind my wife's mysterious failure to keep her appointment with me, you're wrong. There isn't!"

Harringay had picked up a blue pencil from the pen-tray and appeared to be carefully scrutinising the end.

"Quite, quite!" he remarked absently. Then he added, with rather affected nonchalance:

"By the way, what was your wife wearing when she left her club this afternoon?"

Very slowly the colour left Cranmore's face. He rose unsteadily to his feet, dropping his hat which rolled unheeded on the carpet. He bent forward across the desk.

"My God, Harringay," he said, and his voice sank to a whisper, "you know something. My wife's met with an accident! That's it, isn't it? Come on, man, speak! Don't you see how dreadfully anxious I am?"

But the editor did not speak immediately. He got up from his desk and went round to where his visitor was standing. Harringay had a pair of blue eyes which could be fierce but which were more often kindly. He rested his hand for an instant on Cranmore's shoulder.

"You'll want to be courageous," he said gravely. "I'm afraid we have some bad news for you!"

A knock at the door made Cranmore swing round sharply. A keen-eyed, dark-haired young man in a neat blue suit came in briskly.

"I beg your pardon Mr. Harringay," he said. "They told me you wanted me. I didn't know you were engaged....."

"Come in, March," the editor answered. "This is Mr. Cranmore!"

He added something in a quick undertone to the young man whose eyes suddenly lit up with interest. To Cranmore the editor said aloud:

"This is March, our crime specialist!"

Cranmore, his face the colour of the white blotter on which his clenched fist rested, looked slowly from one man to the other, as he waited to learn what shrewd blow Fate had dealt at his life's happiness. And Carmen's face rose before him, dark-eyed, elusive.

A LITTLE clock stood on the mantelpiece in the editor's room. Its whirring, as it was about to strike, brought Cranmore back to his senses. Who was this tall, stern-looking man with the iron-grey moustache who faced him across the desk? And what was this dapper young man saying and why did he seem so embarrassed?

Cranmore looked in uncertain fashion from one man to the other. He had been thinking of Carmen, thinking of her as he had bade goodbye to her that morning, the flash of her dark eyes as she glanced at him over her shoulder and then held up her face, to be kissed.

But the vision had slipped away and he was back in the room of the editor of The Planet, immersed in a most horrible tragedy.

What, again, had they told him? That a young and handsome woman, elegantly dressed, had been found stabbed that evening in a back street in West Kensington and had died a few minutes later in a chemist's shop; that she was wearing a small black toque, a blue serge cloak and a string of pearls; and that her handkerchief and linen was marked "C.C."

"...you could go along to Aldon Street with March here," Harringay, the editor, was saying, "but I greatly fear, from what you tell me, that there can be no doubt about it." Jim Cranmore swallowed with a dry throat. With his dead white face and glazed eyes he looked like a man who had been drinking, and when he spoke his voice was thick.

"But," he protested, "there must be some mistake. Where is this Aldon Street? I tell you we don't know anybody in this slum, as you say it is. And what... what should my wife be doing there? It's... it's... absurd; it's just one of those stories you newspaper fellows get hold of, eh, Harringay?"

"Well," said the editor, glancing apprehensively from the clock to the growing pile of damp proofs on his desk, "I can only trust you're right, Cranmore. Go along to Aldon Street with March. He has been there already and knows the house. Besides, he's acquainted with the Scotland Yard people....."

He stretched out his hand.

"I hope to God," he added warmly, "that this time we are wrong!"

THAT mysterious system of news transmission which in Africa they call the "bush telegraph" is just as active in a great modern city as in the wilds. Though the Aldon Street crime had been discovered too late for a report to have caught the final editions of the evening papers, within a few hours the large red lamp hanging in front of Mr. Chas. Ruddick's pharmacy seemed to have become the assembly point of the whole neighbourhood.

The great ganglion of poor streets clustered about the scene of the tragedy appeared to have emptied the bulk of their inhabitants into Aldon Street. A hundred yards from the chemist's shop Cranmore's chauffeur found his progress impeded by masses of people, bare-headed for the most part, who, quite unable to see anything of interest except the tips of policemen's helmets above the heads of the crowd, were discussing in awed whispers the extraordinary rumours afoot.

March, a quiet, matter-of-fact young man, who had all the trained reporter's knack of sweeping difficulties aside, contrived to force a passage for Cranmore's car right up to the cordon which the police had drawn about the house. Within the barrier silence reigned. A couple of uniform constables held watch in front of the chemist's shop where a dark limousine stood at the kerb. Some towsled women with babies were in the front gardens of the dingy houses facing the house where the murdered woman lay. They conversed in whispers or else blankly stared at the three great jars of coloured water in the chemist's shop-window. A solemn hush rested over the cleared space with its frame of police and crowd, "like a State funeral," the reporter told himself.

At the barrier the police stopped the car. One of the constables allowed himself to be persuaded to go in search of Detective Inspector Manderton, who had taken charge of the case. The officer disappeared into the chemist's shop and presently emerged in the company of a burly, red-faced man of middle height in a dark jacket suit.

March got out of the car and intercepted the new-comer. The latter waved him aside.

"I can't stop to talk to you now," he said curtly.

"It's all right, Manderton," answered the newspaper man. "Between ourselves and for no other newspaper, eh? I believe we've found the husband of the lady in there."

The detective turned a slow, penetrating regard on the reporter. Though his rather heavy jowl which a thick, tooth-brush moustache seemed to emphasise, suggested a plethoric temperament, his eyes were extremely good, keen and intelligent.

"Is that so?" he said slowly. "That should make it a bit easier. We've only got linen marks to go by so far. She has nothing in her hand-bag to identify her. Who is she?"

"A Mrs. Cranmore—her husband's a stockbroker. He's there in the car!"

Cranmore now came across to the two men. He looked from one to the other hesitatingly; but he did not speak. He only made a pathetic little movement of the hands.

The detective paused, distrust in his look. By the way he eyed the reporter, you would have said he suspected a trick with the object of gaining admission to the shop. March touched his elbow.

"It's all right," he said in an undertone, "the description of the clothes absolutely tallies. Don't keep the man waiting. Don't you see he's on the verge of a breakdown....."

He pulled his companion forward and introduced him.

Manderton gave Cranmore one of his searching looks and a curt nod. Then he led the way across the dusty macadam of Aldon Street to the pharmacy.

The little shop, strongly impregnated with the combined odour of Gregory's powder and creosote, was dimly lit by an incandescent gas-burner with a broken mantle which sent forth eerie bubblings and rumblings. Behind a screen of frosted glass inscribed "Prescriptions," a little ferret-faced man with a long red nose and a long red moustache was talking with lowered voice to a black-bearded individual in his shirt sleeves who was washing his hands in a tin basin.

Manderton nodded to Blackbeard, who was the police surgeon. To the ferret-faced man, who was the Chas. Ruddick mentioned on the big red lamp without, he said:

"Don't you go away, Mr. Ruddick! I shall be wanting you again presently!"

With that he pushed open a door that stood behind the counter, a door with panels of ground glass above the painted injunction "Private." A strong whiff of carbolic smote upon them as they followed the detective into a small, darkish parlour. Part of a loaf on a wooden platter and a jug of water that stood on the small walnut sideboard suggested that Mr. Ruddick was in the habit of taking his meals there.

These and other details—the round table in the centre with its stained and faded cover, the steel engraving of the Prince Consort in the Highlands, the threadbare carpet, the uncleaned window looking out on the squalid backyard—the quick eye of the journalist took in as it swept the room before coming to rest on the object which lay shrouded in a white sheet on the sofa against the wall. But Cranmore saw nothing but the couch—, the couch and the humped up sheet...

At the table in the centre of the room under the gas chandelier a man with his back to the door was busy with a fine paint brush and a small bottle, in his left hand he was holding by the blade, which he clutched between a fold of cotton wool, a long knife. March saw the chased metal hilt gleam in the light from the gas lamps as the man applied the paint-brush to it.

Direct in everything he did, Manderton stepped across to the couch and turned back the sheet so as to uncover the dead woman's face. Then he glanced over his shoulder. Cranmore, with set, ghastly face, was at his elbow; but he held his eyes averted. No word was said between them. After a pause which seemed to March to be an eternity, Cranmore turned his head and looked down upon the still, serene face. Then very slowly he bowed his head and, buried his face with his hands, turned his back to the room and walked over to the window.

Manderton exchanged a glance with the reporter and gently drew the sheet over the face again. The man at the table had laid down the dagger and his brush. Now he went over to Cranmore and placed a hand on his shoulder.

He was obviously a foreigner. He wore one of those suits, in colour an indefinite black or grey, of the material the tailors call hopsack, which are habitually worn by the small French official or clerk, with a very low collar and a made-up bow tie of rusty black. In his button-hole the neat red silken button showed that he was Officier of the Legion of Honour. In stature below the medium, he was so broad of shoulder that he appeared to be actually shorter than he really was. A close-cropped but vigorous shock of iron-grey hair, thinning at the temples, a clear, sun-burnt skin—what the French call basané in tint—and a wonderfully keen and piercing pair of bright blue eyes, proclaimed him to be a man of no small vitality and rude bodily health. With a little air of consolation he now patted Jim Cranmore a couple of times on the shoulder.

"My poor friend!" he said in French.

Cranmore raised his head slowly and looked round. As he saw the other his face changed.

"Boulot!"

His voice was hoarse with despair.

"I see," said the Frenchman, "that you have identified Madame. She was a relative perhaps?"

The stockbroker's voice shook as he answered: "It is my wife!"

The Frenchman gripped his hand. Then Cranmore asked:

"What does it mean? Who should have killed her?"

Boulot shrugged his shoulders.

"Patience! It is very dark. There is no motive that one sees. The pearls of Madame have not been taken; her money in her bag seems to be intact...."

The husband turned hopelessly from the speaker and, putting his arm on the window frame, dropped his head on it in an attitude of despair.

"You know this gentleman, Boulot?" said Manderton in his ear.

"Mais oui!" was the answer. And in excellent English he added:

"We were at the English General Headquarters together during the war."

March touched Manderton's sleeve.

"Who's your French pal? I don't know him, do I?"

"Ex-Chief of the French Criminal Investigation Department. Only retired last year. He came over to the Yard to study up some cases for his memoirs. Happened to be in my room when they rung up about this murder so I brought him along. He's not here officially. And, friend March, you needn't put this in your paper, see?"

"Right-o!" agreed the reporter.

Manderton stepped across to the window.

"I take it there's no doubt about the identification, sir," he said to Cranmore.

"None whatever," was the sad reply. "Can't you explain things to me? What does it mean?"

"There's nothing I can usefully say at present," replied the detective. "I've only been here an hour myself. If you'd come into the shop outside, there are a few questions I'd like to put to you. And the chemist can tell you how your poor lady died. As for you "—Manderton suddenly turned on March—"you can't stay here, you know!"

Calmly the reporter looked at his watch.

"I should have been glad to," he retorted collectedly, "but I shall have to bolt if I'm to catch our first edition. Good night, Manderton. See you to-morrow!"

With a nod to Boulot he hurried away.

"What a nerve!" muttered Manderton, then caught the Frenchman's eye. Before its merry glint the severity of the Englishman's expression melted.

"Ah! la presse!" murmured the Frenchman with an indulgent smile.

They spoke in an undertone out of respect for the presence of death and for Cranmore who still, rigid as any image, remained staring blankly out of the window. But now Manderton invited him to pass into the shop. The two men went out together, leaving Boulot alone with the mortal remains of poor Carmen Cranmore.

For a little while Boulot busied himself with his brushes and preparations and cotton-wool at the table, a curiously soft expression in his clear blue eyes. Now and again he would look in the direction of the floor, wag his head and shrug his shoulders as if to say, "Poor Cranmore! Well, it can't be helped!"

Presently he finished his work on the dagger—he had been fixing certain finger prints—and glanced across the room at the sofa, with its still burden. A new look came into his face. The softness vanished from his eyes; he closed his mouth with an audible snap and his brows contracted while, with the index finger of his right hand, he rubbed the bridge of his nose reflectively. When the young men of the Sûreté Générale used to see the great Boulot rub his nose, they knew better than to interrupt his train of thought. When le patron, as they always called him, was thus engaged, it meant that he was on the scent.

Boulot crossed to the sofa and whisked away the sheet. Very methodically he began a close scrutiny of the body. He became so absorbed that presently he was humming a little tune under his breath as he worked. No race has greater respect for the dead than the French; but they are curiously indifferent to the presence of death.

There was a good deal of dried blood on the corsage about the rent left by the knife. Above the tear at the V-shaped décolleté opening the dead woman was wearing a long diamond brooch. Suddenly with a quick intake of the breath, the humming stopped. The detective's fingers were busy with the brooch. Very dexterously they appeared to detach from it some almost invisible thing, for he had to hold it up to the light, between finger and thumb, to see it. He tore a fragment of cotton-wool from a roll on the table, slipped his find into it and thrust the cotton-wool into a waistcoat pocket.

He spent a lot of time examining the dead woman's arms and their short satin sleeves which ended above the elbow. The right sleeve appeared to interest him particularly and, dropping on his knees, he drew from his pocket a folding magnifying glass with which he closely examined it. As he rose to his feet, pocketing the glass, he looked thoughtful.

For a minute he stood inactive while his right fore-finger slowly massaged the bridge of his nose. Then he took up his little tune again and resumed his examination.

He now paid great attention to the dead woman's shoes. She was wearing black suède slippers of the sandal pattern (which was then fashionable), having a strap across the instep joined to another strap running up from the vamp.

Boulot spent a long time over the right shoe.

The humming grew quicker as he bent down over it, turning the foot this way and that. Finally, he unbuttoned the shoe and took it off altogether. Then the magnifying glass came out again and with it the detective very minutely inspected the shoe under the gaslight. His scrutiny ended, he replaced the slipper on the dead woman's foot and fastened the buttons.

He glanced at his watch, covered the body with the sheet again and then set about collecting his paraphernalia scattered about the table. His eye fell upon the dagger which lay, as he had left it, its blade in a fold of cotton-wool. It was a cheap-looking knife, its total length something over a foot with a blade about nine inches long and a white metal handle with a plain Oriental design hammered in in copper.

"The Balkans or Turkey!" said the detective musingly, "a bazaar article that might belong to anybody!"

The door opened suddenly. There was a clatter outside in the shop. Men appeared with ladders, an electric lighting set, cameras. They were the police photographers come to photograph the body. The beautiful Mrs. Cranmore had sat to most of the famous London photographers who had vied with one another in the exquisite studies they had made of her rare and exotic beauty. Neither she nor they had ever dreamed of a sitting like this...

"THAT'S right!" said Mr. Ruddick, who was brewing himself a cup of cocoa in a small saucepan over the gas-ring in the corner behind the counter. "They've found the pore thing's husband. He's in the back-room now, along o' the inspector. White as a sheet, he was, w'en he come in!"

He turned round and peered through his glasses at the man who had just entered the shop, a red-faced young man with a button nose and large red hands, who wore that curiously sheepish air which distinguishes the police officer in plain clothes.

"Quite one o' the nobs, the chaps wuz tellin' me!" observed the new-comer, tapping a cigarette on the back of his hand.

"That's right!" agreed the chemist. "That's his motor at the kerb outside. It's a shockin' bizness, you know. It's given me a proper turn, I can tell you. And, mind you, one gets hardened in this perfession of ours, Mr. Smith, wot with street accidents an' burnt children or maybe a lady as is expectin', comin' over faint. But to see that pore young thing in there murdered, as you might say, before your very eyes.... dear, dear, I don't know wot the world's comin' to! Some lunertick did it, I shouldn't wonder! Puts me in mind o' the Ripper murders. Ah! but you're too young to remember them. Artful chap, he was, mind you. Hung about dark alleys an' the like—Whitechapel way it was—an' pounced out on the pore gels! We lived down the Commercial Road in those days—that was before my pore old Dad had his bankrupsy—an' I remember Dad takin' me, as a little nipper, to look at the bloodstains on the pavement down there off Leman Street. Care for a drink of hot cocoa, Mr. Smith? I've made enough for two!"

"You're very kind!" replied the plain clothes man. "I 'aven't 'ad bite nor sup since my tea. I've bin over at 'Ammersmith all the evening after that precious neighbour of yours!"

"There's sugar in it!" said Mr. Ruddick, passing a smoking cup to Mr. Smith. "And did you find Mrs. Amschel?"

"Aye," replied Smith with a wag of his head as he noisily sipped his cocoa, "over at her brother's as keeps a furniture shop. She didn't want to come back 'ere, though. Not 'arf!"

"I don't wonder!" observed the chemist polishing his glasses. "She was upset something frightful. Jews is so excitable, Mr. Smith, sir. You recolleck the air raids. You may believe me or not but...."

The bell on the shop door clanged. Mrs. Amschel stood in the doorway. Her face was an unhealthy sallow shade and her eyes were restless. Behind her followed a solidly-built man who was fanning himself with a straw-hat.

"Guv'nor here?" he enquired of Smith.

The latter jerked his head in the direction of the back-room.

Mrs. Amschel, in the meantime, had gone round the counter to Mr. Ruddick.

"Vot they vant to see me for, the police, eh? I ain't got nothing to do with it, 'ave I? Vot do the police vant fetchin' me avay in the middle of the night? I'm a respectable voman, I am, as vell you know, Mr. Ruddick....."

Her voice rose shrilly and quavered.

"I keeps myself to myself, so vot do they vant with me?"

"Keep your hair on, mother," said Smith gently. "You ain't goin' to be locked up. We only want your evidence. Silly, I call it, bunkin' off like that...."

The door of the back-room opening interrupted him. Manderton, followed by a well-groomed man with a ghastly face and haunted eyes, stepped briskly into the shop. At the sight of the detective the Jewess, who was standing beneath the burbling gas lamp, fell back a pace as though she would shrink into the shadows behind the counter.

But Manderton walked straight up to her, his eyes stern, his forbidding jowl thrust out.

"Well, Rachel?" he said.

Mrs. Amschel cast a frightened look around. She nervously twisted her fingers and made a kind of bob to him.

"Goot efening, Mr. Manderton!" she stammered.

"This is a dam fine business for you to be mixed up in, mother!" said Manderton, looking her up and down.

"Mixed op in? Mixed op in?" repeated the Jewess in shrill accents. "An' me settin' as quiet as quiet outside me own lawful premises w'en the pore lady drop dead at me feet. She mix 'erself op vith me, Mister, not me vith 'er, vish I may die ef I ain't a-telling you Gawd's own truth...."

"Don't you start going off the deep end, Mother Rachel," warned Manderton sternly. "You set down quietly on that chair there and answer my questions. And, before you try any of your monkey tricks on me, just you remember that I know one or two things about you. Let me see, there was the Levinsky case and that business in Cable Street...." "I Gott! I Gott!" lamented Mrs. Amschel, one red and dirty hand placed on her vast bosom, "'ow you take a pore voman's character avay. You vos very 'ard on me the lars' time, Mr. Manderton, very 'ard. That schnorrer Levinsky, 'e made a fool of me along of me being honest an' not suspectin' nothing. But there ain't a vord agin me in the neighbour'ood. You 'aven't only gotter arsk Mr. Ruddick there!"

Manderton firmly propelled her huge bulk into the kitchen chair which Mr. Ruddick pushed forward. So wholly did she fill it that it completely disappeared beneath her ample proportions so that you would have said she sat on air.

"And now," enjoined Manderton, bending his brows at her, "cut the cackle and tell us what happened!"

With many ejaculations and as many digressions, Mrs. Amschel, in her bewildering Anglo-Yiddish jargon, told how the "pore lady," "dressed op so fine," had suddenly appeared hurrying along Aldon Street and, after asking Mrs. Amschel to call her a taxi, had pitched forward at the Jewess's very feet.

As she finished her story, the bell on the shop-door jangled. With feet that trampled noisily on the worn linoleum, while instructions were bawled from the threshold to a husky voice whose visible possessor was swallowed up in the velvety night, a number of men filed into the shop.

"Have they come... to take her away?" Cranmore asked the detective.

"They're only the photograph men from the Yard," replied Manderton. "No, no," he added soothingly, laying a retaining hand on Cranmore's sleeve. "I want you to stay right here with me. Mr. Ruddick will tell you how Mrs. Cranmore died, and I want to ask you some questions!"

The photographers passed through into the back room, dragging their apparatus and ladders with them, the street-door was shut and once more quiet fell upon the little shop. Manderton turned to the chemist.

"Now, Ruddick," he said, "I haven't had time to hear your full story. Suppose you tell us all you know about this affair."

The chemist cleared his throat nervously, rubbing his bony hands together the while.

"Well," he began, "I was in me shop here...."

"Stop!" bade Manderton. "What time was this?"

"I wouldn't be sure of the time. But it was gorn six, 'cos I rec'leck hearing it strike. An' it wasn't the half hour, for the Horseshoe at the corner wasn't open. It'd have been about a quarter past six, I'd have said...."

Manderton nodded curtly.

"Right!" he said. "Get on with it!"

"I was in the shop, castin' up me books, w'en I hear screechin' on the pavement outside. I nipped out quick, and there, at her shop door, I see Mrs. Amschel, in a condition of considerable agitation, pointin' at a woman—a lady, I should say, for elegant she was, one could see that at a glance. At first I couldn't make out w'ot Mrs. Amschel was screamin' about, but all of a sudden I see the handle of the knife stickin' out of the pore lady's chest. Before I could move a hand to help her, the strange lady—Mrs. Cranmore, that is,—just fell all of a heap on the pavement, in a kneelin' position, as you might say. As she went down I heard the knife rattle on the flags. I picked it up afterwards and give it to the officer w'ot my boy fetched off point-duty at the other end of Aldon Street.

"For the moment, gentlemen, I didn't bother about the knife, I give you my word, but picked the lady up—she was light, sir, being of small build—and carried her through the shop into the back-parlour. I laid her on the sofa and was turning quick-like to get Mrs. Amschel, who I thought had followed me indoors, to loosen the pore lady's dress when I see her eyelids flutter. Then she opened her eyes and raised her hand. I saw that she was trying to speak."

Mr. Ruddick broke off and blew his nose violently on a red silk handkerchief which he produced from the tail pocket of his long-skirted frockcoat.

"I bent me head," he resumed, "for I knew the pore thing was near her end—and in my time, gentlemen, I've seen a-many go!—and tried to make out her words. But do what I might, I couldn't catch what she was trying to say. Leastwise, not to make sense I couldn't...."

"Tell us just what you heard, man!" snapped Manderton.

"The only phrase I could make anything of, sir," said the chemist, "was something about a orange and a divan. She said that twice; but very faint-like. And... and... she looked at me so pleading, gentlemen, so sad, I give you my word, I felt reelly distressed I couldn't understand it. I leant over and I said: 'Madam' I sez, 'what was it you wanted?' I sez. But she only smiled and sighed. And with that, gentlemen, she died...."

With his long red nose and drooping moustache, his watery eye and long scraggy neck, the chemist was a grotesque figure enough. But there was a simple dignity in the way he told his tale that gripped his audience.

A silence fell on them all as Roddick finished. It was Cranmore who broke it.

"That was all she said?" he asked.

"Absolutely all, sir; that's right!" was the chemist's reply.

Cranmore turned to Manderton. His eyes were brimming and the wet gleamed on his face. But he kept his voice under control.

"She must have been delirious," he said. "My wife has an orange couch in her room. I suppose she imagined herself to be at home."

"Where was Mrs. Cranmore when you first saw her?" said Manderton, turning to the Jewess.

"But... here in our street."

"Where in the sheet?"

"Right on the corner, op at the top of the road, on the same pavement as this...."

"You are sure she was alone? There was nobody with her?"

"Iwo!" cried the Jewess with a gesture of the hand. "The voman vas alone, I haf said it!"

"Did you hear a scream or any sound of a struggle before she appeared?"

"Nothing!"

"Perhaps Monsieur Cranmore can tell us whether he or Madame had any acquaintances in this neighbourhood?"

Mrs. Amschel started violently at the suave voice which sounded from the shadows of the shop. M. Boulot stepped into the pool of light behind the counter where the others were assembled.

"... because," he observed blandly, "it would seem to one to be important to establish what Madame was doing here. ..."

Manderton turned quickly to Mrs. Amschel.

"Here," he said, "you can be off to bed now, Mother Rachel. But don't you go running off again. You're evidence at the inquest, see? And don't you forget it!"

"I von't sleep in me 'ouse alone, Mister!" protested Mrs. Amschel. "I'm goin' back to me brother's at Ammersmith."

"As long as we know where to find you!" retorted Manderton.

The Jewess heaved herself out of her chair. Ruddick escorted her to the door and saw her into the street. Then Manderton turned eagerly to Cranmore.

"Boulot's question is to the point," he said. "Have you any idea why your wife came to Aldon Street?"

"Ever since I came here," responded Cranmore wearily, "I've been asking myself that question. There is no reason that I know of."

He stopped; then, looking from one to the other, "Mr. Manderton! Boulot!" he said with almost painful intensity. "What was my wife doing in this slum?"

"That, mon ami," answered Boulot, pursing up his lips, "seems to me to be the first thing we have to discover. Another question.... have you many acquaintances among artists?"

Manderton turned his head deliberately and stared slowly at the Frenchman.

"A few," said Cranmore. "Horace Dingwall, for instance, is a member of my club and my sister-in law, Miss Driscol, who lives with us, knows some of the Chelsea set. But I don't quite see...."

"Patience!" enjoined Boulot. "Was Madame in the habit of visiting studios?"

"In the habit? No! Sometimes we have been to one of Dingwall's private views...."

"Might she, for example, have visited a studio this afternoon?"

"Carmen . . my wife," Cranmore answered, "always told me of her engagements. As a matter of fact she went out very little alone socially. She had few close friends and we went to most places together. If she visited a studio this afternoon it was most probably as the result of an engagement made suddenly—over the telephone, perhaps. But I think it most unlikely. And certainly she mentioned no such engagement to me...."

"But have you amongst your acquaintances any artist whom you frequent, who might, say, telephone to Madame and invite her to call upon him?"

The Frenchman's voice was unalterably suave but deadly persistent.

"No," said the stockbroker. "Unless it might be Dingwall. And I happen to know that he's on his way to South America. But why all these questions about a studio?"

The French detective slowly rubbed his nose. Manderton, who had lit his pipe, was eyeing him closely.

"Not withstanding what you say," Boulot resumed, quite ignoring the other's question, "might not Madame have visited a studio to-day without your knowing?"

Cranmore shook himself rather irascibly. His nerves were beginning to fray.

"It's possible," he returned irritably. "But it would probably mean that she was visiting some friend of whom I had no knowledge...."

Boulot leant over the counter, propped up on his elbows. In his hands he was twisting the dagger which, probably unconsciously, he had picked up.

"My friend," he said bluntly. "It may be that you are right..."

But Cranmore flung his hands out in a gesture of denial.

"Ah!" he cried. "Now I know what you're getting at. Let me tell you at once, Boulot, and you, too, Manderton, that my wife had no lover. Our married life is.... was.... ideally happy. And let me tell you something else. With my poor girl lying dead in there, I'll not have her memory blackened. I'll not stand for it, do you hear? You, Boulot, are a Frenchman and perhaps don't look on these things quite as we do but...."

A big red hand descended on his shoulder.

"Steady, steady," said Manderton. "We have to examine every possibility, you know...."

Cranmore shrugged his shoulders.

"That possibility you can rule out!"

"I had no wish to offend," remarked the Frenchman, "and I ask your pardon, mon cher, for my words. But this possibility apart, do you know of anyone who should harbour a grudge against Madame?"

"No," retorted Cranmore positively. "No! It's unthinkable. My wife did not have an enemy in the world."

"You have no theory then?" asked Manderton.

"None, I am simply stupefied. I can only imagine that this is the work of a madman...."

Manderton studied the tips of his highly polished black boots, turning one foot this way and that so as to reflect the light.

"You mentioned just now," he observed, "that your sister-in-law knows some of the Chelsea set. Was she in the habit of visiting studios?"

"She was at one time," said Cranmore. "But I stopped it. To be quite frank I objected...."

"I see!" said Manderton in a perfectly noncommittal manner. "And did you object to anyone in particular?"

Cranmore paused and looked at the Inspector. He rubbed his hands nervously together.

"You know I want to help you all I can," he declared. "But I don't want to throw any unjust suspicion on anybody. You asked me just now, Boulot, whether there was anybody who might conceivably harbour a grudge against my wife. Mr. Manderton's question reminds me that we did have some trouble with a painter chap who, my wife and I thought, was seeing too much of Dolores—my sister-in-law, you know. I had to stop him coming to the house. He was probably sore with my wife because he had known her in New York in the days before she met me...." He looked up and found the eyes of the two detectives fixed intently on him. He hesitated.

"I don't want you to suppose for a moment," he added hastily, "that I connect him with this horrible crime. Young Quayre is quite incapable of anything like that...."

"What was the name?"

Manderton had pulled out his note-book and his manner was sternly official.

The stockbroker stared from one to the other.

"You don't imagine?..." he began. "My God!...."

"Let's have his name and address," Manderton interposed.

"His name," returned Cranmore, "is Julian Quayre. But I'm afraid I don't know his address. I know he has a studio somewhere in London. But I've never been there. You'll get his address in the directory. ..."

"Ahem!"

With an apologetic cough Mr. Roddick rose up from his stool by the gas ring. The three men had forgotten his very existence.

"What the blazes do you want?" demanded Manderton, rounding on him savagely.

"If it's the address of Mr. Quayre you're requirin'," ventured the chemist, nervously plucking at his fingers until the knuckles cracked, "I can give it to you. He's a customer o' mine, in a manner o' speakin'. Why, I sold him a toob o' toothpaste no longer ago than...."

"Damn it!" cried Manderton irascibly. "Where does he live?"

"In Broke Stoodios, up at the top of the road," said the chemist.

HARDLY had Mr. Ruddick made his dramatic announcement when the bell on the shop-door clanged. In the eerie light which came from the great coloured jars in the window they saw a girl standing, a young, slim girl with dark eyes staring out of a dead-white face. Boulot, with his impressionable French temperament, could not suppress a gasp of surprise, for it seemed as though the dead woman on the shabby sofa had come to life.

When the girl stepped into the patch of light flung by the gas-lamp above the counter he saw how greatly she resembled the dead woman. Her beauty was less mature (for she was obviously younger) and her colouring was different. But she had the finely-chiselled features, the same serene, clear gaze and the same sweetness of expression as he had remarked in the still form lying in the back-room. There was, however, the warmth of life in the girl's cheeks and her hair, while dark, was brown rather than black so that the general effect of her beauty was less severely classical than Mrs. Cranmore's.

She advanced swiftly into the shop, then stopped suddenly as her eyes fell upon Boulot. The Frenchman stood at the counter full in the rays of the light. But the girl did not look at him. Her gaze was concentrated with an expression of horror in her dark ryes upon the long knife held carelessly in the plump hands. The intensity of her expression laid, as it were, a hush of awe upon the little shop. The men stood like graven images, the two detectives side by side at the counter, Ruddick, with his mouth open, in his corner, Cranmore, his face ravaged by grief, behind Boulot, and the two plain clothes men just discernible as bulky shadows in the background.

Boulot laid the knife down. Its metallic tinkle seemed to break the spell. The girl went forward towards the group and seeing Cranmore faltered out:

"Carmen...."

Cranmore, with ashen face, lips tightly compressed, nodded.

"It's true then?"

The girl's voice broke with despair.

"I'd just come home from Ranelagh... some newspaper rang up... it was dreadful.... there was nobody in the house.... how did it happen? I can't believe it! I can't believe it! Who would want to kill poor darling Carmen?"

The flood of words choked her and she broke off with a little sob.

Cranmore took her hands in his and soothed her.

"My dear, my dear!" was all he could manage to say.

"Jim," cried she, lifting her eyes to his, "they are saying in the crowd outside that she's here, stabbed, dead. Oh, let me go to her! Let me see her!"

The stockbroker flashed an enquiring glance at Manderton. The detective shook his head.

"My dear," said Cranmore, "what's the use? It would only add to your grief. Perhaps tomorrow..."

His speech was slow and the words dragged themselves from his lips slowly like the gait of one who goes hampered with leg-irons. All the brisk energy of the man who, but a few hours since, had driven his smart car so alertly down Piccadilly, seemed to have evaporated. In some subtle fashion he appeared to have aged since he entered that house of death.

The change in him seemed to strike the girl, for she said softly:

"How dreadfully ill you look! Won't you let me take you home?"

But now the bulky form of Mr. Manderton thrust itself into the foreground.

"This Miss Driscol?" he asked, and without waiting for an answer, he said to her:

"Did Mrs. Cranmore call on Mr. Quayre this afternoon?"

The effect on the girl was electric. She seemed to shudder and, like a sleep-walker rudely awakened, to come to herself with an effort.

"Mr. Quayre?" she repeated dully. "Jim," she said suddenly, clasping his arm, "why does he ask me that?"

"Because," replied Cranmore, "Quayre is the only person Carmen knew in this part of London. You know he lives in some studios at the top of this road. ..."

"Broke Studios!" said the girl in a dazed fashion. "Then what is the name of this street?"

"This is Aldon Street," came the answer, sharp and precise, from Manderton, "and we have reason to believe that your sister was stabbed somewhere between this shop and Broke Studios. Therefore it is important for us to know whether Mrs. Cranmore was actually at Mr. Quayre's studio this afternoon or whether she was perhaps on her way there...."

Dolores Driscol looked up and met the calm, blue eyes of Monsieur Boulot who was watching her face with embarrassing attention. A little colour came into her cheeks and she averted her gaze. She turned to Mr. Manderton.

"I can't tell you," she replied. "My sister and I lunched together at home. She had not been out all day, as it was so hot, but as soon as it got a little cooler, she said, she was going to have tea at her club...."

The door of Mr. Roddick's back-parlour opened and the police photographers reappeared. Simultaneously, the shop-bell rang and a voice asked for Mr. Manderton. The detective detached himself from the group and went to the door. From there he called Cranmore over to him.