RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Her attention was momentarily distracted from the

game of diabolo with which she was busily engaged.

OUTSIDE the great gales of Ripley Court, the Curer of Souls and the Curer of Bodies shook hands with the grip of a short friendship, yet long sympathy, founded on the tie of Oxford associations and a common object. They—the two energetic microbes, who were doing their best to effervesce the ditch-water of Ripley village to the bubbling zest of soda-water—differed in every respect.

The representative of the Church Militant bore the look of a man who had been beaten in a hard fight by unfair methods. His black coat seemed weighed down with depression, and his hat was even more crushed than is demanded by clerical etiquette.

"You'll have no luck with her, Brady," he said. "I've tackled her repeatedly. She's hard as nails."

"Then she needs hammering, and by my grandmother's parrot, she shall have it. You've been on the wrong lack entirely."

The speaker's face kindled in the glow of the hanging lamp. Tall, and of striking personality, Terence Brady looked more like a Bond Street exquisite than a country doctor. Of mixed parentage, the English mother within him had decreed he should thus array himself in the frock coat of etiquette as he paid his formal call on the lady of Ripley Court; but inside this frigid casing his Irish father was whirling his shillelagh with mad glee in expectation of a fight.

Terence Brady's long legs propelled him up the drive to the time of a double two-step, while his eager thoughts winged on before him; then there was a minute of tiresome delay, while the man with the mission provided the man at the door with his name for the purpose of a formal entry.

Yet his real entry was anything but formal. As the drawing-room door opened, the mistress of the great house looked at Brady with a glance of welcome, for she thought he was afternoon tea. Her face dropped when she saw only a visitor, and her attention was momentarily distracted from the game of diabolo with which she was busily engaged. The spool descended, and, finding no cord to meet it, dashed, like a great white moth, towards a pink-shaded lamp. Contrary to the nature of the flame, it seemed for once to reciprocate this passion, for it shot up to meet it.

The next minute there was a feminine shriek, and the overturned lamp was spreading a pool of liquid flame over the flimsy tablecloth.

As the girl rushed away from the scene, the two men dashed towards it. But the waiting-man was naturally slower than the man who acted, and to Brady's lot fell the burning honours of extinguishing the flaming mass. Thus, dashing, flushed, and eager—in a circle of limelight—Terence Brady made a dramatic entry to the acquaintance of Miss Vivien Primrose.

"Real Irish luck," said Terry inwardly, as in one brief moment he found he had wiped out quite thirty minutes of frigid overtures, and was nearer the object of his quest. It was pleasant to sit in an easy-chair while a remarkably pretty girl alternately thanked him and fussed over him, and Terry, who liked all young things, from children to new potatoes, was especially tolerant to the charm of youth in women.

"I'm sure you have burnt your arm, and I shall never forgive myself if you have. Do turn back your sleeve and see," cried Vivien, as she laid impetuous fingers on his frock coat.

"Not a bit. I haven't so much as scorched myself," answered Terry, stoutly resisting her overtures. "And, in any case, I'd like to keep the scar as a memento of a charming lady. Now, do look. That kettle is boiling over with impatience to make your acquaintance."

As Miss Primrose busied herself with the tea-equipage, the doctors keen blue eyes looked with surprise at this young lady who had been represented to him as an armour-plated virago. The sole heiress to her father's wealth, seen through the golden mist of a fortune her claims to beauty had been exaggerated, but even Terry, who was not prepared to admire her, found her pretty.

"A dimple, too," thought he with delight, as he noted the treacherous pit that has swallowed up the common-sense of so many men. "She can't be such a Tartar with a dimple."

Vivien started the conversation with hunting, but before long, as they exchanged ideas, they found that, so far from following the fox in spirit over the red earth, they were soaring up into the clouds. So many thoughts in common, so many mutual tastes, so many experiences to relate, that they were soon borne along on the full spate of friendship.

But, little by little, Terry turned the talk to the subject of his visit. It was his pet theme—the Cottage Hospital. He deplored the fact that the wives of the righteous county folk allowed this full-grown adult scandal to stand unchallenged in their midst. He observed that when he tried to drive home the facts of the case to these smug gentry, men who had approved of him because he rode straight had resented the fact that he could talk straight as well. They could afford to hunt, but when it came to a question of putting their hands to their pockets, they pleaded poverty. Was it not a shame?

Miss Primrose assented, and then gently tried to switch the conversation on to the number of unpaid hunt subscriptions. But Terence was firm. He insisted ongoing into details of the exact state of dilapidation and discomfort that reigned at the miserable travesty of a hospital, and at his downright words Vivien shuddered. He imagined it was from sympathy, and instantly he saw himself, twenty years later, when he had raked in fame and a fortune, coming to claim her and her stately home, while apparently she remained still the pretty golden-haired girl of twenty-three.

"And what we want," concluded Terence vehemently, "is to pull down this rotten old shell—this plague-spot—and erect a splendid new building. It must, and it shall be done!"

Vivien's eyes sparkled. "Why don't you do it yourself?" she asked.

"I?" Brady roared with laughter. "I do it? Whom do you think I am?"

"The nephew of the Duke of Wesson, to begin with—"

"To end with, a poor devil of a doctor, without a shirt to his back."

Vivien smiled at the extravagant statement of the tall young exquisite, who was intently-regarding her with eyes that were bluer than her own.

"No, Miss Primrose," announced Terry firmly, "I'm not the man to do it. But it's hanging like a load on my back, and I stumble over it at every step I take."

He paused, evidently more impressed by the pathos than the impossibility of this particular feat. "Now, is it fair? It's your responsibility that I am bearing. You are the largest landowner in the district, all your interests are here, you have no ties, you have the means. And clearly you are the obvious person to wipe out this disgrace for ever, and preserve it as a living monument of your generosity, enshrined in all the grateful hearts of the county."

He stopped, panting, and then looked at Vivien in dismay. The soft curves of her mouth had been sucked into a hard red line, and her eyes were glassy. The flow of friendship had been turned off at the main.

"I am very sorry, Dr. Brady," she said coldly, "but I must decline to take up your magnificent project. It is against my principles."

"Principles!"

"Yes." She winced slightly before Terence's accusing eye, for she knew what he meant.

"I know it will seem strange to you," she began, "but I've not been brought up in the English way. If I appear harsh, let me assure you I am not really. My heart is in the right place."

"As a medical man, I should be much more interested if it were not. Pray proceed."

"And I've thought and studied the question, and gone really deeply into it, you know—political economy, and so on. And, indeed, doctor, you do no good in prolonging useless diseased lives. It would really benefit humanity if such cases were allowed to die out, just as you weed a garden, instead of being nursed back to sickly life, and allowed to be perpetuated. I don't suppose you will see my point, but—I feel very strongly—and though I give to other things—indeed I do, very largely—I never subscribe a farthing to any hospital."

Terry's teeth snapped. He looked at the pretty appealing face, with its peach colour rubbed in by perfect health, and the memory of the Rev. Noel Bigg's words came back.

"May I ask if you have ever been ill?" he inquired sternly.

"Never."

"Well, you may have read and thought a great deal, but it is evident you have never lived. Good evening. Miss Primrose. I am sorry I troubled you. And let me, as a friend, wish you the best that can befall you for your ultimate salvation—a thundering long illness."

Vivien staggered at the words. Then she drew herself to her full height, and swished round her superfluous draperies in order to obtain a few meretricious inches.

"Thank you," she said, ringing the bell. "In return for your kind wish, I desire you to forget that—I have ever had the honour of your acquaintance."

"Certainly, madam. It is granted. I look forward to the pleasure of an introduction to Miss Primrose."

Then, with a courtly bow, he left the indignant lady.

The Rev. Noel Biggs was enjoying a well-earned smoke before the fire in his shabby rooms that evening, when the door burst open to admit Terence's broad form, still gorgeous in his war-paint. He sank down with a groan, and Biggs noticed that his face was white and drawn.

"Well, the first round of the fight is over, old man," remarked the doctor, "and I have had the half-nelson. I was not only kicked out, but in future I am denied even the honour of bowing to Miss Primrose. The history of this evening is completely wiped out, and all I know is—that I have had—a free tea—somewhere."

As he spoke the last words, his head toppled weakly over his chest, and his tall hat rolled forward on to the mat. The curate sprang to his side in sudden alarm. He propped up his friend's head, and then made a violent search for stimulant The contact of the glass against his teeth made the doctor open his eyes, and he drained it before he spoke.

"Sorry to be such an ass. See here! It happened at the very beginning, and I had to sit it out an infernal time, in order to take advantage of a good beginning."

He rolled back his sleeve, and displayed the inflamed surface of an ugly burn.

"Why didn't you mention the fact?" asked Biggs, aghast.

Terence smiled drily. He had poured out his heart to Miss Primrose in their early confidences, and made her a present of his soul, turned inside out, but in the interests of self-respect the line must be drawn somewhere. Irish linen is a valuable asset, in a desperate financial strait, and he—the reckless, handsome, smartly-garbed professional man—with native impudence, had spoken the truth to Miss Primrose in the matter of his wardrobe. He was without a shirt to his back!

A few days later the doctor effectually settled the vexed question of his parentage, as he drove along the flat road, back from a troublesome case. He was in deep depression, although by this time circumstances had permitted him to bridge the gap in his raiment. But not even this fact could dispel his gloom.

"This settles it entirely," he mused. "An Irishman would have got drunk, and then forgotten her. I'm English, through and through."

In spite of his melancholy, his frame stiffened with pride at this thought, but then he groaned aloud at the recollection of a fluffy-haired fairy, who, in spite of her precocious depravity, had destroyed his peace of mind. To his surprise, his groan was echoed, and he awoke to the fact that a bundle of clothes was lying under the hedge.

In an instant Terence had thrown the reins to his small boy, and was kneeling by the prostrate form. As he looked, his eyes nearly bulged out of his head in surprise.

This was Vivien—but not the dainty, waxen beauty, who looked as if she had just stepped out of layers of tissue paper.

She wore a green, weather-beaten skirt, and a white flannel blouse, both of which were mud-spattered and torn. Her hat had gone, and her hair fell in untidy wisps round a scratched face. Her boots were unspeakable, and round her neck was slung a bag. As the doctor stared, the girl opened her eyes, and with a sigh of relief he realised that they, at least, were unchanged.

"Thank goodness for somebody at last," she said. "I suppose I've fainted, for I've hurt my foot or something. We were paper-chasing, and I was a hare, and my papers gone."

Then she suddenly remembered the position, and coloured faintly.

"I am exceedingly sorry to detain you," she said in icy tones. "On your way home will you kindly call at Ripley Court, and ask them to send a carriage to me?"

The doctor hesitated. Then a sudden, reckless flash fired his eye. He shook his head.

"Sorry, but I daren't do it. It would be as much as my place is worth."

"What on earth do you mean?"

"This. Though I have not the honour of Miss Primrose's acquaintance, I have heard that she is an exceedingly autocratic personage, with strong views on the subject of illness and injuries, and I would not dare to enlist her aid for any maimed traveller found on the high road."

Vivien stared, not understanding his drift.

"Don't talk nonsense while I'm in pain. I'm Miss Primrose."

"You are in pain? Then that's the first consideration. Allow me."

In spite of her protests, the wretched boot was soon massacred, and even Vivien could but admit that the doctor's deft touch did much to soothe the ache of her ankle, as he again sacrificed his unlucky wardrobe to the extent of his handkerchief in the cause of bandages.

"That better?" he asked.

"Thank you, yes. I am obliged. Now I wish to go home to Ripley Court."

The doctor instantly felt her pulse.

"Delirium often follows a broken bone," he observed, "but in your case it has come on with unusual rapidity. Were you not a young girl, I should suspect you of being a hard drinker."

"How dare you speak so to me? To me?" "To you? There, now, that's what I want to find out. Who are you?"

"You know perfectly well. Miss Primrose."

But Terry shook his head with conviction.

"My dear young woman," he said, "consider the absurdity of your assertion. Although I have not the honour of knowing Miss Primrose, your appearance does not justify your claim to be such a very grand lady. But, here goes."

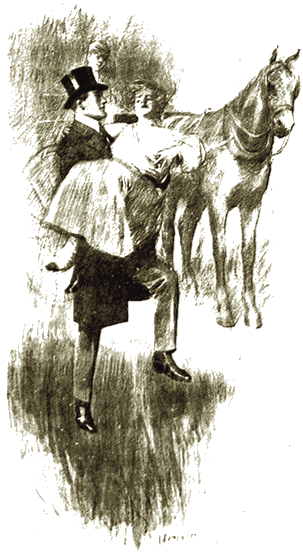

Before she was aware, Vivien was swung into the air and on to the front seat of the dog-cart.

"Where are you taking me?" she gasped.

Before she was aware, Vivien was swung into

the air. "Where are you taking me?" she gasped.

"To the only place in which I can offer you shelter for the night—the Cottage Hospital."

Although Vivien's face grew vivid with temper, a sudden gleam of respect glinted in her eye. She realised that her foe was engaging in warfare on rather a magnificent scale.

She looked between the horse's ears to the long line of hills.

"Will you tell me what you know of Miss Primrose from hearsay?" she asked.

"Certainly. I know she is young and wealthy. Everyone knows that. And I know—I dare to know—that she possesses beauty and—Dr—innate goodness. But, to diagnose her complaint, she has broken out in a nasty eruption of selfishness and inexperience, and I believe that one good dose of personal experience would put her right again."

"I can corroborate your information on the first point," was the dry answer. "Miss Primrose has immense wealth at her disposal, which is a tremendous weapon in her hand. She could effectually crush anyone who stood in her way by the force of her money and influence, ruin his career, and drum him from the county."

Terry's eyes flashed in reply.

"It all depends on the odd trick," he remarked inconsequently.

In the distance a white blur of buildings peered through the evening haze. Vivien turned once more to the doctor.

"Can you afford to play?" she asked. "You stand to lose much."

"And, by heaven! I stand to gain more. The stake's a woman's soul!"

The excitement that seethed through his veins pulsed down the reins to his horse, and they made a clattering halt before the door of the hospital. As the boy rang the bell, Vivien again spoke.

"Your lead, doctor. You may trust me not to betray myself, and make myself the laughing-stock of the place."

But she shivered with depression as she rested in the dim reception-room. It had never been her lot before to enter such a gloomy place. Then a harassed nurse-matron, in a soiled uniform, came bustling in.

"This is too bad of you, doctor," she said. "I simply can't take in another case. My 'pro' has nearly collapsed, and we're worked off our legs. Besides, we really haven't the accommodation."

"Oh, yes you will, Miss Finlay," urged Terence. "Just to oblige me. This is only a sprain, and I can't communicate with her friends till the morning. It is purely a personal matter."

The matron grunted. Then she led the way to a low-ceilinged room, which was crammed with beds and screens. Several women sat about in shawls, and a child was whimpering.

"We might squeeze her in a corner for to-night," she said.

The formality of enrolling her name was dispensed with in the rush that followed, for Vivien, who had now merged her individuality into "the Sprain," was denied the dignity of a "case." She was merely told to lie down on a lumpy bed in a corner, while her foot was properly bandaged. Vivien submitted with a rigid face, but when Terry finally took up his hat to depart, she cried out in a kind of panic:

"I can't spend the night here with all these people. The air will be poisoned. You must open all the windows."

"A draught would be fatal to some of the cases. Of course there ought to be proper ventilation, but there isn't. Everything that should be right here is wrong. It won't do you any good, but it will do you less harm than the others."

The matron's face flushed with temper.

"It's a perfect scandal!" she cried. "I wish I had some of the wealthy people here—say Miss Primrose—for one night only."

Terence's lips twitched. "You never know your luck," he observed.

Then they left her, and Vivien turned to look, with eyes of loathing, at the ceiling with its scaly growth of peeling plaster above her bed. All around her rose a chorus of groans and complaints, but she lay stiffly staring at the circle of gas-jet with fixed eyes. Later in the evening a cup of tea and some thick bread and-butter were brought for her refreshment by a weary-eyed "pro," but she turned from it with disgust. One thought only possessed her, and she turned it over in her brain until, from constant friction, it glowed to red-hot madness.

"I won't spend the night in this vile hole, I will get out, I will, I will!"

She stared at the ceiling in a mad longing to grip it in her fingers and peel off the roof. She yearned for the strength of a Samson, wherewith to pull down the walls. Then she raised her head and took stock of the window by her side. It was heavily barred.

Below, at right angles, ran a line of buildings, the out-patient room, and the mortuary. Vivien marked the untidy tangle of their thatched roofs with satisfaction. Then, looking round the room stealthily, she searched for her silver match-box, and approached the window. A minute after there was the scrape of a match, and yet another, and two flaming grubs flitted through the air, to alight on the far side of the roofs below. A soft breeze fanned their hot heads, and instantly a tiny scarlet worm began to eat its way through the dark mass of thatch, leaving a fiery trail in its wake.

Meantime, Terry had driven off through the dark lanes, in a fit of mad excitement, his cart swinging from side to side dangerously. Turning a sharp corner by the mill, it was by mere luck that he managed to check himself at the shout of two men. In the glow of his lamps he recognised his friend the curate, but he hardly heeded the hard-visaged man who accompanied him. It was Jasper Bailey, a close-fisted, long-lipped, retired banker, against whose money-bags Terence had run his head when he had tilted at him in his desperate efforts to obtain a subscription. The quarrel that ensued from Terry's importunity had made this man his own especial enemy.

The curate raised his eyebrows at the mare's heaving flanks.

"Are you red-hot from a murder?" he asked. "What's up?"

"The price of bread. Stand clear!" was the wild answer.

"Things bad at the hospital?"

"No, something more important. As for the hospital, I will keep it going in the faces of all the misers in the country, if I have to sell every worthless thing I possess, beginning with my soul."

There was a rattle of wheels, and he was gone.

"Drink!" observed Mr. Bailey sourly. "He will soon come to the end of his tether here."

It was not until the doctor had reached his rooms that his mad fit suddenly dropped from him. Then, with the bitterness and feminine fluency of his Saxon mother, he cursed the influence of his Hibernian father. He saw what he had done in its true light. On the mad chance of trusting to a girl's sense of generosity, he stood to lose everything.

Terence paced up and down his room, longing for daybreak, yet dreading its advent. Unconscious of the time, he pulled aside the heavy curtains in the hope of seeing the sun tipping the east with gold. But, to his surprise, the night was illuminated by a false dawn that reddened the sky. Then as a torch shot up in a cascade of flame, Terence, racing madly for his boots, realised that the hospital was on fire.

When the doctor arrived, panting, on the spot, it was already a scene of mad confusion and activity. The alarm had been given in time, and the majority of the patients had been removed to a huge barn, which was hastily converted to a temporary shelter. With a deep feeling of thankfulness, Terence learnt that the fire had broken out in the wing removed from the main wards.

But, if no lives were lost, it was clear that the hospital itself was doomed. In spite of the efforts of the firemen, the flames leapt over to it, licking it greedily as a preliminary to devouring the plague-spot in deadly earnest.

As a group of farmers watched the spectacle, the doctor suddenly rushed up to them, his face working in the red glare, with the twitchings of a lost soul.

"Are you sure they have removed every patient?" he asked. "One is missing.'

"Sure, for certain, sir. Not even the cats left."

"But she's missing. I can't run any risks."

As he spoke, with glorious inconsistency he ran the greatest risk which falls to a man's lot, for he dashed into the blazing shell where charred beams were already beginning to drop. For five lurid seconds he galloped through the Inferno of smoke and flame, his eyes raking every corner of the place. He had scarcely reached the outside air again when, with a sudden crash and a leaping pillar of flame, the roof fell in.

Close on daybreak, when Terence, heavy-eyed, smoke-grimed and baffled, returned to his rooms, leaving behind him the blackened rafters of a skeleton building, a disreputable young female limped up the drive of Ripley Court. She slipped into the side entrance and stole upstairs. The mistress of the house had returned with the milk.

For a week Vivien nursed her indisposition and her scheme of revenge for the annihilation of the doctor. Instead of awakening her conscience, the sufferings of the unhappy patients had served to aggravate her own. But on the eighth day a box arrived, bearing a Bond Street label, and Vivien appeared again, if not to the light of day, at least to the light of night, clad in a creation to dazzle all eyes at the Hunt Ball.

This was the most important social function of the year, and when Vivien and her chaperon arrived at the Assembly Rooms, they found half the county putting the last touches in the cloakroom. It seemed to the girl that the buzz of conversation was unusually animated, and she had barely succeeded in catching a snapshot vision of her face in one of the glasses when a matron bore down on her.

"Do you think he will have the face to turn up to-night?" she asked.

"Who?"

"Dr. Terence Brady, of course!"

"Why not?" asked Vivien quietly.

"What! Haven't you heard? Its all over the place! He has done for himself, and will be turned out of the county."

Vivien staggered. Accustomed to a sense of her own importance, she had scarcely supposed that she was a person of such consequence in celestial regions that the very stars had fought for her, and thus accomplished the doctor's downfall without her personal intervention.

"Tell me all," she cried.

"Well, it's this fire at the hospital. You know how mad he was to get a new building. He increased the fire insurance, and directly after, on the night of the fire, was seen driving away from the place, half drunk, and swearing that he had sold his soul to keep the hospital solvent. Mr. Bailey can testify to this, and even his own friend, the curate, cannot deny it. And to make things blacker, he introduced some unknown woman there that night, as an accomplice, I suppose, to start the fire. Anyway, in the morning she had vanished. Plain enough, isn't it?"

Vivien walked off to the ballroom with her head in a whirl. It was clear that her share in the affair was not so impersonal as she had imagined.

The band was beginning to tune up, and the usual groups of people hung around the door, all intent on the process of booking up. The same topic of conversation was on every tongue—the disgrace of the formerly popular Terence Brady.

"He has been warned not to put in an appearance to-night," remarked Mr. Bailey in his acid voice. "We thought it best to save him that much."

Then a sudden hush fell over the talk, as, standing in the doorway, the grand picture of a man in his hunt evening dress, stood Terence Brady. Vivien, watching his flushed face and blue eyes, thought she had never seen anyone face a situation with a braver carriage.

Taking a card, the doctor approached the nearest woman and asked for the pleasure of a dance. She was but an insipid miss of eighteen, but her refusal was decisive. He promptly turned to the next lady, to meet with the same rebuff. It was plain that before carving him up as a dish for the dogs of disaster, the county was having a trial performance, and to the feminine section had fallen the honour of exercising their dainty penknives in the first "cut."

Brady realised as much in a flash. Then, holding his head high in a spirit of bravado, he went in rotation down the line of ladies, his smile becoming gayer and his bow lower as he acknowledged each fresh snub.

With wonder in her heart Vivien watched him. Twice he had braved fire for her sake, but she knew that this reception, paradoxically enough, constituted, by reason of its very coldness, his hottest ordeal.

The band struck up for a waltz. Terence had completed his tour of the ladies and his ordeal was over. For one moment his nerve failed, as he stood in indecision, partnerless and alone, in the middle of the room.

Then his eyes suddenly flashed. He had faced the music, and he meant in return to get his worth out of the band. Crossing the room to where his friend, Noel Biggs, regarded him with sorrowful eyes, he laid his hands on his shoulders. The next minute the scandalised crowd was aware that he was spinning round in the whirl of a waltz with his clerical partner. In spite of them all he was not to be done out of his last dance!

As the waltz proceeded and the couples revolved in rapid rotation, it became evident that events were moving yet faster, and that each bar of the music was leading up to a crushing finale. A group of men watched the graceless doctor with angry amazement, and then, after a short consultation, Mr. Bailey, in his capacity of M.C., walked up to Terence. He stopped dancing, and, by common consent, half the dancers stopped as well, anxious to assist at a scandal of unusual magnitude.

Bailey tapped Terry on the shoulder.

"I must request you to leave the ball-room," he said. "Exception has been taken to your presence."

"I gathered as much. On what grounds?"

"You would be wiser not to ask, but if you wish to know, owing to your connection with a case of arson."

Terry laughed.

"Keep your eye on the law of libel. Do you suggest I made a bonfire of the hospital and burnt up half my personal effects which happened to be there on loan?"

"No, sir." Mr. Bailey's temper got the better of his prudence, as, by mockery of eye and voice, Terry goaded him beyond his self-control. "But it is believed that you instigated the outrage, and in order to clear yourself, you will have to produce the nameless female you introduced into the building on the night of the fire."

For the first time since that fateful night Terence looked straight into Vivien's eyes.

"That's the trouble," he said ruefully. "I don't know her."

"You brought her there yourself. This is not a time for quibbling!"

"But you see," persisted Terry, "we were never introduced." Then he shot Vivien a sudden glance of audacious confidence. "And if I had been," he added, "I should try to keep a good thing to myself."

There was a long pause, and in the silence Vivien's inflamed sympathy told her that Terence had thrown down his last card.

The game was finished.

She turned to Mr. Bailey.

"A short explanation from me will clear up all this mystery," she remarked. "But, first of all, I must ask you kindly to reverse the ordinary order of etiquette. Will you introduce me to—Dr. Terence Brady?"

"A short explanation from me will clear up all this

mystery," she remarked. "But, first of all, I must ask

you kindly to reverse the ordinary order of etiquette.

Will you introduce me to—Dr. Terence Brady?"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.