RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

SYLVIA REED longed for a vocation, and accordingly selected hospital work. She was drawn to this particular branch of usefulness by a genuine desire to alleviate pain, and the potent attraction of the uniform.

If her pretty blue eyes noted her picturesque reflection in the mirror with complacency, the girl's satisfaction was tempered with an absolving leaven of high-born resolutions. These she cradled in hope, and as she unfortunately failed to add perseverance, it sang the usual lullaby to her aspirations.

Sylvia missed her star, but gained an earthly paradise.

When the pretty probationer was flirting round with her duster, she was incidentally slipping into the good graces of one of the medical staff of the hospital. So she finally left the hospital before her time of probation was over, and vanished in a cloud of rice into private life.

Never did a matrimonial venture start more brilliantly.

Jayne saw only sunshine in Sylvia's volatile nature, and basked in its rays, unconscious of gathering storms.

ONE fine day, about three months after their marriage, he descended to the breakfast-room in a particularly amiable mood.

The room was flooded with sunshine, and Sylvia looked daintily pretty in her fresh white dress. The canary sang in the window, and a pot of snowdrops on the table suggested Spring. Sylvia broke off one to fasten in her husband's buttonhole before she attended to his wants.

Jayne studied the charming face, half of which was hidden from his gaze by a tea-cosy possessed of an alarming sense of propriety. There was a pleased air of excitement lurking in her smile, and a sparkle in the pretty eyes.

Every man knows the symptoms. She was enthralled in the joys of a secret.

Jayne's grave features relaxed as he noted her evident enjoyment.

"Now, I wonder," he observed indulgently, "what is the reason of this sudden excitement?"

"Excitement! What reason! I'm not a bit excited." Jayne laughed.

"Is it an idea for a sweet dress, or a dream of a hat? Or, stay—have you heard of a new cook?"

"No, dear, don't be silly. I didn't mean to tell you, but I suppose I must, just to stop your nonsense. I was thinking how nice it is to see one's name in print."

Jayne roared outright.

"Why, it's never been trying to write?"

"Yes, it has, and," defiantly, "it has succeeded!"

"Oh," she went on, enjoying her husband's amazement, "it was not a scrap difficult either—only took about three minutes, and—oh, you poor dear, you do look astonished. Here it is!"

His astonishment increased as he took the page she showed him. It was an advertisement for some patent soap. In black letters above was printed:

A Doctor's Wife Writes:

I have much pleasure in testifying to the excellence of your soap.

Signed.

Sylvia Jayne,

Harley Street, London.

Jayne stiffened with displeasure, but Sylvia did not notice it as she prattled on dreamily:

"Of course, it's only a little thing, but it gives me such a funny sort of pleasure. When I look through the Sketch and all those papers, I just long to have my photo in, and know everyone is looking at it. But, of course," she added wistfully, "there's no chance of that."

No answer came to destroy her reverie, and she continued in ungrammatical eloquence:

"But this is something the same. Just fancy, perhaps I shall see people in 'buses and trains reading this, and they will never think that the person who wrote it is sitting by them. And doesn't it look nice—'A doctor's wife writes'?"

"Sylvia!"

"Why, Leslie!"

"Never let me hear any nonsense of this kind again. It shows a senseless vanity and a lack of stability that I am ashamed to see in you. I had no idea you were so petty!"

Sylvia looked up. "It's not my character that's at fault. It's you. You don't understand me."

She ran out of the room, and banged the door.

ALL the morning Sylvia indulged in the luxury of playing the

misunderstood. After lunch she sallied forth to see a friend, a

rich spinster, with a comfortable love for humanity, only

excluding the animal man.

"My dear," she said solemnly, "I see a sad significance in this morning's episode. When a man fails to understand the hidden springs of your nature it shows something is missing. It's men, my dear, who make creation miserable, nothing else. Why, even the martyrs at the stake did not suffer a bit once the nerve tissues were destroyed. It is always such a blessed comfort to me to remember that."

Sylvia walked home in a rebellious frame of mind, but was surprised to find that Leslie, though graver than usual at dinner, made no allusion to the morning.

"He did not mean what he said," was her final deduction.

SHE was passing through a phase of disease which attacks most

women of her temperament, and as she had no means of an outlet,

it was a dangerous malady. Had she been rich or influential her

society functions would have graced the columns of the

fashionable papers, or she would cheerfully have been torn to

pieces on the staircase at a fashionable crush for the pleasure

of seeing her name next morning in print.

After the first outburst the course of events flowed on as smoothly as before. The only difference was that each had discovered at least one clay toe in the feet of their idol. Jayne deplored a tendency to vanity on his wife's part, and she sadly felt Leslie's temper was defective. Sylvia's final conclusion was that her husband did not like to be told of her small recreations, which were otherwise legitimate, so she broke out from time to time in elegantly-worded testimonials, from which she derived a seraphic happiness worthy of a better cause.

These she carefully concealed from Leslie, so there was no renewal of the scene until a month later.

Breakfast was again the fateful meal. Jayne was reading a newspaper article which wrestled with the theory as to whether matrimony was an economy.

"It depends on the wives we choose, my dear," he said approvingly. "Everyone may not be so fortunate as I."

Sylvia coloured with pleasure. "And you don't even know how very economical I am. Why I get some things for nothing!"

"My dear, the bills come in regularly."

"But I tell you it's a fact. That tin of oatmeal—you are eating some at present—is a sample tin."

"But I understood samples were rather diminutive."

Discretion had a brief but desperate struggle with Sylvia's thirst for appreciation. Then, unhappily, it was overthrown. The girl lowered her voice.

"If," she asserted, "you want to get a big tin, you just write an advertisement—Oh, Leslie, what's the matter?"

Jayne suddenly rose from the table, and strode into the kitchen, followed in trembling apprehension by the culprit, who vaguely wondered if he contemplated suicide, or intended ordering a fresh consignment of porridge.

"Mary," he said, addressing the awe-struck domestic, "bring that packet of patent oatmeal."

He received it from the girl's fingers with a tragic mien, stepped to the kitchen range, and flung it on the fire. Without a word he left the kitchen, feeling pleased at the way in which he had disposed of the matter. Actions, he argued, spoke louder than words.

"Well," gasped Mary, "what a wicked waste!"

But Sylvia flew upstairs in a perfect passion of tears. "Only too late I've discovered it," she sobbed; "tied to a man with a temper. But I won't be bullied, or give in. I'll continue to assert my individuality."

AN acute observer might have noticed an unusually hard look

about Sylvia's mouth after that episode. But not one would have

guessed that the corroding word written in her heart, of which

the look was the outward and visible sign, was—Oatmeal.

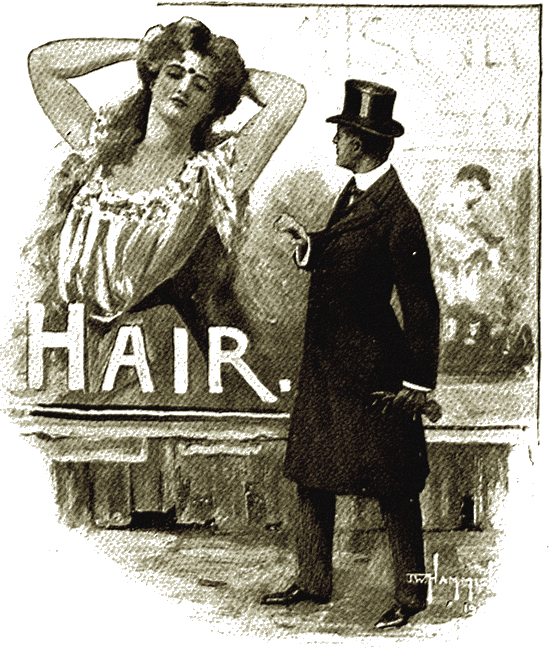

Leslie Jayne's friends described him as the essence of refinement, while his enemies stigmatised him as "mean." As a matter cf fact, he had a marvelous sense of the fitness of things, with a microscopic eye for details. His mental retina was at present occupied with the letters "M.D." after his name, and a visionary doctor's brougham. Anything that came between him and these cherished objects disconcerted him greatly. It was with a shock of positive horror that a few mornings afterwards he saw on a hoarding in Charing Cross Road a huge poster of a pretty woman, whose rippling curls hanging down to her waist were due, according to the wording underneath, to a world-famed hair-restorer. No need of the name to tell the original! It was Sylvia, his Sylvia! During the rounds at the hospital, one of his colleagues mentioned the poster, which had caught his eye.

He saw on a hoarding a huge poster of a

pretty woman. It was Sylvia... his Sylvia.

"I wanted to ask you," he began, "is that your wife?"

But Jayne had already gone. He reached home that night in a white heat of rage. His wife was silting by the drawing-room fire, book in hand. She raised her eyes, and they looked at each other, defiance meeting with anger.

Jayne glanced round the pretty apartment, which was destined to be the scene of another sordid strife between outraged sensibilities and domestic relations. Their wedding presents strewn around them, mute witnesses of the day when their married life began, failed to draw them from the fray, while a few streets away the wretched poster flapped in the wind, the inadequate cause of another matrimonial shipwreck.

Jayne went up to the fire, and kicked a piece of coal.

"I've seen that poster," he said icily.

"Most people have by now," was the triumphant reply.

"Have you lost all sense of decency?"

"Have you lost all pride in your wife's appearance?"

"Don't be absurd! That's not the point."

"But it is. You don't care about me now. You don't admire my hair. Once you said it was the prettiest hair in London; now everybody admires it but you."

"Apparently everyone will have a chance of admiring it now," groaned Jayne.

"You haven't a scrap of pride in me. Mr. Adrian Rose, the artist, said he would love to paint me; he admires me, and he's an artist."

"Don't be hysterical."

"It's a comfort to think someone appreciates you, if your husband does not," and Sylvia subsided into tears, while Jayne hastily went out, banging the door.

TEARS and bangings were the keynote of the next few days; but

about the fourth morning Sylvia appeared with a bright face. She

was cheerfully ready to eat her own words. Her hilarity

positively grated on Jayne, who was suffering from a bad attack

of toothache.

"Leslie," she said bravely, "I've determined never to send another testimonial—never, if it displeases you, though I don't see why it should."

"That's right," was the somewhat grudging reply.

"So no harm's done, dear."

"That poster?"

"Too flattering! No one will recognise it."

The effort which it cost Sylvia to make this assertion was greatly to her credit.

"Have you been sending any more of these beastly things away?" asked Jayne, preparing to issue pardon.

"Only one. But the funny part is, I was writing about a cure for stammering for Aunt Lena, and sending a testimonial for the cough medicine which did you so much good, and I muddled them up, and the testimonial reads: 'You've cured my husband of stammering!' Isn't it funny? Especially as you do stammer a little."

Jayne rose to his feet. "Do you know what you've done?" he demanded. "This time you've made me an object of ridicule. You've degraded the medical profession. And you crown your confession with duplicity; you feign sorrow and repentance. I cannot find a home here, and if I go outside every wind blows these wretched advertisements to me. I'm heartily sorry for the day I met you."

In his eloquence, Jayne had forgotten the primary cause of his displeasure. He only realised that he was a long-suffering individual with a grievance, who was goaded to fury by a disobedient wife. A good measure of his anger melted during the day, but he dreaded the evening interview with the tearful Sylvia. So, accordingly, he sent a telegram to say he would be detained in town that night.

It put the finishing stroke to the girl's misery. Her husband's hasty words had filtered through a nature already riddled with emotions. She had intended to put everything right, and banish the clouds that had settled on the household, but had only received the knowledge that she was an undesirable superfluity.

She fled in tears to her spinster friend, who gave her good advice—"to go to bed, and sleep on it." Unfortunately, she only followed half, for she wooed sleep in vain. She tossed and turned, and exhausted herself by violent fits of crying. As she had eaten nothing all day, the strain presently reacted on the overwrought brain. She was sure her husband hated her, and wished he had never seen her. She felt these words whirring through her brain, till she was conscious of nothing else.

AT six next morning, a miserable, white-faced girl crept down

the steps into the fog without. She made no plans, and had but

one fixed resolution, namely, that she must leave her

husband.

At the door, as she paused for breath for a moment, a broad form hurried through the gloom, and, with a feeling of gratitude, she recognised the face of Adrian Rose, the artist.

"What! Going off so early?" he inquired.

"Yes, but," looking helplessly at the Bradshaw she carried, "I'm not sure about the trains."

"Ah! You've had bad news, I'm afraid?"

"Yes," was the faltering reply.

The two heads bent over the railway guide, and Sylvia indiscriminately sorted a name out of the tangle. Any kind of refuge would do.

"Here you are, the 7.45. We had better take a cab. I'm going off by the early train myself."

So a hansom soon rattled away with the two travelers, and Sylvia thanked Fate for the cavalier who had come to her rescue, unwitting of the fact that this incident would prove an effectual barrier against her reentering her Paradise for many a long day.

WHEN Jayne reached home the next night, he encountered the

curious gaze of a frightened-looking maid.

"Missus went away this morning, but I think she left you a message."

Yes, there was the inevitable note, pinned in time-honoured fashion to the cushion, incoherent, scarcely legible: "After your cruel words, I can no longer stay with you. I am leaving you, for ever!"

Jayne laughed uneasily. "Hysteria again. She will be back to-morrow."

Then he rang for the housemaid.

"Did your mistress take any luggage?" he inquired.

"No, sir; I didn't know she was going. She didn't have even a cup of tea. I'm sure I was surprised when I saw her outside talking to Mr. Rose."

Jayne's face grew white, but he made no sign, and the servant warmed to her tale.

"There they were, sir, looking out trains in a Bradshaw, and they went off in a cab together."

Then Jayne shut the erring Sylvia from his heart.

IN a week's time she had repented, and she wrote a letter of

apology, begging forgiveness. Her husband tore it up unopened. A

second letter shared a similar fate, and when the prodigal wife

hurriedly returned to town, she found the house shut up.

All they could tell her was that the doctor had taken abroad a globetrotting patient, and left no address.

Thrown on her own resources, and deserted by her husband, Sylvia hardly knew what to do. Her pride prevented her from appealing to her relatives, but she had a friend to whom she turned—the rich spinster. She gathered the poor girl into her fold, like a brand snatched from the burning, until the time when Sylvia was again able to take up her part in life's struggle.

WHEN Jayne returned to England, after a year's absence, he was

astonished to find that no one seemed to be conscious of his

domestic troubles, and it was popularly supposed that his wife

was still abroad. He also heard casually that Rose had married a

pretty American two days after Sylvia had left him. Ostrich-like,

he had thought to escape his trouble by burying himself; but now,

in the face of the doubts which persisted in rising, he wished he

had not so hastily destroyed all communication. For appearance'

sake, it would be as well to investigate the story. His

cautiously-worded advertisements failed to discover his missing

wife. Sylvia had completely effaced herself.

ONE cold, grey morning Jayne wended his way Citywards. London

was wrapped in a cold, grey fog, and the chill bit into his

bones, and made his face blue. At the Marble Arch he took the

Twopenny Tube, and as they rumbled swiftly on, he glanced at a

girl opposite.

She was reading a popular magazine, and as she turned over the paper cover, the inner leaf was exposed to his view. A flood of bitter memories swept over his mind; then suddenly—from the tangled shadows of the past—he awoke to consciousness.

His own name was staring him in the face!

Jayne strained his eyes incredulously.

It was the picture of a baby, clad in its own birthday suit from Nature, and underneath was printed:

Leslie Jayne, aged fifteen months, brought up on — Food since the age of three months.

Above was the inscription. How proud Sylvia had been of the phrase, "A Doctors Wife writes"!

Anyone glancing at the man sitting motionless, staring out at the curved walls that sloped in front, would never have guessed at the storm of chaotic feelings that raged behind the rigid face.

It was atrocious! Hateful! The woman was past all shame! To break out again—to defy all decent feelings of reticence, to expose her son—his son—to the gaze of every Tom, Dick, and Harry—and without a rag to cover him. His fingers itched to tear the paper from the unconscious reader's hands. When she looked up inadvertently, and saw a strange man glaring at her, the poor girl was quite alarmed.

At last the Bank was reached. Jayne could hardly wait until the lift transported him to the higher regions again. Oblivious of his business, he rushed to the nearest newsagent's, where he feverishly turned over the papers. His search was unavailing—no similar advertisement could he find.

The boy's sarcasm began at last to penetrate his consciousness, ami, as he groped, he was hardly aware of the changes, which turned his anger to impatience, which in turn melted again into anxiety.

"Like the whole shop, sir? Nothing to pay!" quoth the youth, but Jayne took no notice. With a cry of triumph he swooped upon a number, and hurriedly throwing down half-a-crown, he departed, leaving change and reputation behind.

Once outside, he hailed a cab; he felt he dared not trust himself to look at the thing while curious faces surrounded him.

At St. Paul's Churchyard he got out, and, obeying an impulse, walked up the steps into the Cathedral. With the exception of a few scattered groups, the great building was empty. The pillared heights, the light filtering through the stained-glass windows, and the solemn quiet took the last shreds of fever out of the man's mind. He opened the page calmly.

Yes, it was a baby of which anyone might be proud. What a bonny little fellow it was, with its rounded limbs and laughing mouth, showing the dear little teeth. Just such a son as he could have wished for, and with his name, too! So she had called him after his father!

As he again scanned the tiny features, a strong sense of familiarity quickened the doctor's recollection. Where had he seen this portrait before?

Memory showed him an old, faded photograph of another baby, which was cherished by a mother with tender eyes. A deep feeling of shame swamped his thoughts, as he realised how he had slipped, through countless acts of pettiness, from his childhood's throne of innocency.

The grave eyes of the other baby looked at him in reproachful wonder. Only this one, his son, had curly hair, a golden halo of curls, such as he had never possessed. For the first time in many months, a feeling of tenderness crept into Jayne's heart, as he thought of Sylvia's golden tresses, of which he had been so proud.

The baby looked as if he had come straight from the Garden of Eden. The thought struck Jayne that if, like another Eve, Sylvia had clothed the child only in its halo of curls, she had no Adam to work for her. He had never bought a single garment for that wee atom. Then came the question—where was she living? What was she doing? He remembered the unopened letters, with anguish. Might there not have been some grave mistake? He had refused all explanations, but now, how to find her?

Suddenly, with a gasp of relief, he peered again at the page. Yes, there was the address, in little black letters, in the corner. Oh, the blessed advertisement paragraph!

The black type swam before his eyes, and then blurred into a white mist. Mechanically, he took out his note-book—a somewhat superfluous act considering the address was branded into his brain. As his eye traveled over the list of engagements, he gave a start. In half-an-hour he had an appointment with one of the greatest authorities in the medical world—an appointment that he had deemed himself both proud and happy to obtain.

Jayne frowned. Sylvia was always getting in between him and his profession, ever since the days when, as a pretty probationer, she had wooed his thoughts from fractures and temperatures. And now she was exerting the same baleful influence through his boy!

He stopped from force of habit to calculate. It would make but little difference whether he sought out his missing wife now or a couple of hours later. He looked again at the portrait, and then, as though illuminated by a flash of lightning, the wasted years stood sharply before him. For the first time a glimmering suspicion asserted itself that he might have offered other sacrifices up to his profession than time and labour. Was not Sylvia included in the category?

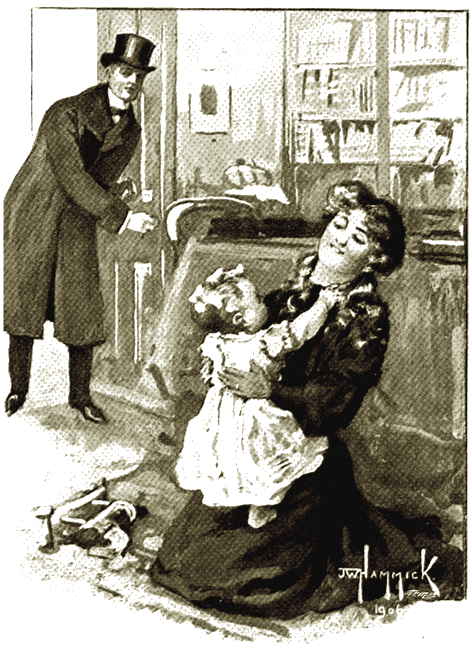

Suddenly, little baby fingers seemed to pass over the cherished appointment, wiping it out, and though Leslie knew it not, some of the old, selfish nature died at that moment. A few minutes later Leslie was in the train, speeding out towards Sydenham, chafing at every stop. He had a nightmare feeling of oppression as he walked along the dreary suburban roads. At length he stopped before a small semi-detached villa. The door was open, and an untidy servant wrangled with a tardy errand-boy. Pushing aside the astonished pair, he burst into the small sitting-room. Kneeling on the rug was Sylvia. The golden hair, her pride, hung in tangled curls over her black dress; the firelight kissed it into a copper glory, and she was laughing as the fingers of a beloved little tyrant pulled down the tresses. At the sound of footsteps, she looked up hurriedly, clasping the baby to her heart.

Kneeling on the rug was Sylvia.

He saw her face, sweeter than of yore, with the lines of care and resolution marring the empty prettiness of feature.

Suddenly Sylvia raised her eyes and saw her husband looking at her in the old, fond manner. Instantly the past three years were wiped out. With outstretched hands and the red staining her face, she ran towards him.

"How did you find me?" she cried.

A cloud suddenly blotted out the sunshine on Jayne's face.

"By this," he said grimly, throwing the paper on the table.

Their hands never met. The moment had passed and the wretched advertisement still lay between them.

Sylvia started back. With a hunted movement she seized the boy and strained him to her.

"You want baby!" she cried. "You have come to take him away from me. You never shall—there!"

It was the old Sylvia breathing defiance, and Jayne's heart hardened. From the shelter of his mother's arms the baby looked at the intruder with the ineffable hauteur which is the exclusive property of infants under the age of two.

Jayne cleared his throat. "Listen!" he said. "When you left me I had, perforce, to come to certain monstrous conclusions. It was not my fault"—the old Jayne struggled hard to assert himself—"you thrust it upon me. Now, I was wrong. I await your explanation, and if—as I believe—it will be satisfactory, my home is waiting for you and—baby. There is only one obstacle." He paused, and both looked at the piece of paper. He struck it violently. "This! This wrecked our lives for three years. I see, in spite of all you have gone through, the old craving for cheap notoriety remains. Now, where will it end?

"It has ended!"

Sylvia drew herself up, her eyes shining.

"Leslie, have I ever lied to you?"

"Never!" he admitted.

"Then listen. When I left you I saw everything in its true light It was vanity—all vanity! And I was sorry. I never wrote another advertisement. But—" she strove to hide her tears—"things grew so bad lately. I was penniless, so I remembered and wrote this. They sent me £5 for it. But I've written my last advertisement. I swear it—my very last!"

Then suddenly Jayne snatched up the paper and threw it on the fire.

And, a minute later, they had forgotten all their troubles in one long embrace.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.