RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

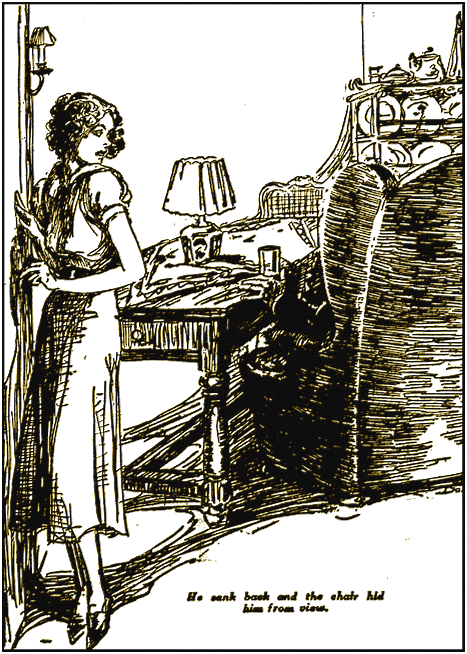

He sank back and the chair hid him from view.

"WHAT would happen to Puck if I had been killed?" This was the first thought which flashed across Merle's brain after her crash. It was the agonized question of the bread- winner, for her small nephew—Puck—was entirely dependent on herself.

The accident was not the fault of the motorist, since she had crossed the road against the lights. She had been mooning back to work, down the scented gloom of the lime avenue. It was June 23rd, Midsummer eve, and some one had told her that a dream dreamed on that special night, always came true...

Even as she smiled at the fancy, she was conscious of a shattering shock, followed by a black-out; and then she opened her eyes, to find herself lying on the pavement, while an elderly man with a kindly face, bent anxiously over her.

"Oh, I'm sorry," she cried. "Have I hurt the car?"

"The question is—has the car hurt you?" he asked.

To his relief, although bruised and shaken, she was miraculously intact. She rose unsteadily to her feet, and was beginning to fumble for her powder-puff, when he spoke to her.

"You had better let me drive you home."

As she was on her way to work, it seemed wiser to give the address of the doctor for whom she acted as secretary-dispenser. To her dismay, there was an appreciable pause before she could remember it. In the end, however, her brain began to function again, and not long afterwards, the car stopped before the right door.

Dr. Perry lived in a large old-fashioned house, at the end of the ancient city, which was dominated by gray cathedral towers. Nearly every street was lined with limes, or chestnuts, which formed cool tunnels during the summer heat. A slow green river flowed slowly through the town, which had been half asleep for the last hundred years.

Merle loved every stone of it, but this evening, it seemed doubly precious, because she had so nearly lost it. When the motorist had driven away, she entered the house, by the private way of the dispensary, and threw herself down into a deep leather chair.

The sun had been beating down on the glass roof all afternoon, so that the place was warm as a conservatory. It was very quiet, for Mrs. Stock—the housekeeper—was in the kitchen and the doctor was out, at a case in the country. He was only beginning to build up a practice, and there were no appointments for the evening.

As she sat in the twilight, smelling the familiar druggy odor, blended with the scent of the jessamine screen over the windows, Merle grew cold to realize the risk to which she had exposed Puck by her criminal carelessness. Although the gentleman had an imposing string of names, his nickname was apt, since he was rather like a mischievous elf.

He was the kind of child to whose appeal women are vulnerable—delicate, affectionate, clever, and a champion trouble-maker. Merle was especially sentimental and apprehensive over him, because he was her sole salvage from an unhappy past.

She had endured a little hell of proxy suffering during her twin-sister, Marvis' disastrous marriage to Lewis Gore. Unfortunately, her brother-in-law's conduct offered no loop-hole for legal redress. His mean bullying nature was not manifested in acts of violence, just as—although he soaked continually—no one had ever seen him drunk... But he contrived to drain his young wife of her joy and vitality, so that, at the first illness, she flickered out of life, leaving her baby boy in Merle's care.

At first, Merle was too stunned with grief, and too worried about the future, to appreciate her legacy. It took nearly all that remained or her small capital, to finance Lewis and clear him out of the country. Since he had gone, however, she could hardly believe in her present happiness and peace.

She often herself that she had everything—Puck, her work, her home, and loyal service, for Puck's nurse looked after the bungalow. Lately, too, a new element had come into her life, for she was conscious of the doctor's growing interest in herself. He was a kindly practical man, and she was growing very fond of him.

As usual, she considered Puck's interests first, and she came to the conclusion that, besides the benefit of a resident physician, the young domestic tyrant needed masculine authority.

She had drifted off into a light sleep—for the warm gloom acted as a soporific—through which she could hear faintly the cooing of the pigeons and the ticking of the grandfather's clock. Presently she opened her eyes and forced herself to rise. The movement made her feel so queer and dizzy, that she knew that further work was out of the question.

"I'll mix myself a draught, to quiet my nerves," she decided. "And then I'll rest a bit, before I go home."

To her dismay, she found that she lurched against the furniture when she crossed over to the shelves. Her head was spinning like a weather-cock in a high wind, while the floor heaved like the deck of a steamer, during a channel crossing. Half-blinded by a mist which drifted before her eyes, she managed to measure and mix a sedative.

As she raised it to her lips, she felt suddenly too sick to drink it. Laying it down again, she groped her way from the dispensary into the cool cavern of the big dining room, where she flopped down in an easy chair.

Closing her eyes, she listened to the distant sounds of Mrs. Stock moving about in the kitchen, until she was aroused by the creaking of the door.

JUMPING up in a panic, she stared, in incredulous horror, at

her brother-in-law, Lewis Gore.

He was tall and enormously stout, with a head too small for his bulk. His light cold eyes—set in deep pouches—glittered like white glass, as he nodded in casual greeting.

"Hullo, Merle."

She forced herself to speak.

"When did you come back, Lewis?"

"I landed yesterday. I've come back to collect my boy. I am taking him back to Borneo."

"Borneo?" she echoed, scarcely able to believe her ears. "But Lewis, he is so wee and delicate. He could never stand the heat."

"He'll get used to it. The kids there don't play. They just sit around and sweat. Very healthy, on the whole."

"No, Lewis, I can't let him go. You don't understand. I've had all the trouble in the world just to rear him... If you want money—"

"Money?" He laughed thickly. "My dear girl, I've not come back to hold out my hat. I've married a rich widow, with a rubber plantation, out there. You can send your bill for his keep. It can't be much for bread and gravy."

The mean speech, which flattened out two years of sacrifice into a thin spread of pap, was typical of his mentality, but Merle barely heard it. Her head was throbbing like a dynamo as she thought of Puck. He had to be tempted to eat, even in an English imitation heat wave, while he grew languid and limp as a wax candle.

It was torture to picture him—bewildered, unhappy, ill-torn from his devoted slaves and handed over to callous strangers. She knew he could never survive the change from his own little kingdom to a damp tropical exile.

"You can't do it," she cried with sudden fierceness, which was foreign to her nature. "I won't let you. It would be murder. Murder."

As her voice rose, the door slipped open a few inches, and the long horse-face of the housekeeper appeared in the aperture. "Was any one hollering 'murder'?" she asked.

Merle was too agitated to do more than shake her head, but her brother-in-law growled an order of dismissal.

"Clear out."

After another long suspicious gaze at the girl's quivering face, Mrs. Stock went away, banging the door to register protest.

As though the noise caused her jammed brain to vibrate, a wild plan suddenly flashed through Merle's head. When her brother-in-law dropped into the empty chair, and spoke in the amicable tone which paved the way for a customary request, she agreed with him in token of defeat.

"That's settled then," remarked Lewis. "Ill collect him some time this evening."

"I'll have him ready," she told him.

"Well, then, what about a quick one?"

"A drink? I'm sure the doctor would offer you one. I'll get it at once."

AS she walked slowly toward the door her decision was made.

She intended to take Puck away immediately and hide him in some

quiet place until Lewis had gone abroad again.

Only, since every minute's start was of importance to her getaway, it was necessary first to take steps to prevent his father from coming to the bungalow that evening. He must be doped, so that he would sleep for a few hours in the safe haven of the doctor's dining room. It was evident that no meal was going to be laid there that night, for the doctor would return too late for dinner.

Lewis' back was turned toward her as she crept to the sideboard and snatched up the whisky decanter, so he did not see her go into the dispensary.

Her head bumped furiously when she crossed over to the slab where she had left the sedative which she had mixed for herself. The specks of light which kept flashing across her eyes, blinded her vision; but as the powder was already dissolved in the glass, she only had to fill it up with whisky.

"Lucky I had it already," she thought, as she carried it back to the dining room.

Her brother-in-law remained seated and appeared to be already at home, as though in anticipation of his enforced visit.

"It's neat," she told him tremulously.

"That's right." He nodded approvingly. "Never tasted good water."

She gave him the tumbler, and saw him drain it as she reached the door. He sank back and the chair hid him from view; but she heard a satisfied grunt and a creaking of springs, as though he were settling himself more comfortably.

"I must wait a few minutes, just to see if it is going to take effect," she told herself.

Her heart was hammering with impatience, for she was in a fever to get back to Puck. In spite of recurrent fits of giddiness she paced the room, unable to keep still. As she paused by the dispensing-slab, she took up the bottle she had left standing there.

Suddenly her vision cleared, so that she read the label clearly. Unable to credit what she saw, she stood, staring at it in frozen horror.

Instead of a sedative, she had just given her brother-in-law a fatal dose of virulent poison.

She clutched her throat, to strangle her screams, as she realized her position. She felt sure she would be under suspicion of committing a crime, since the principal factors—motive and opportunity—could be proved. Everyone knew about her devotion to her small nephew and also her hatred of his father.

Further, there would be the evidence of the housekeeper, who disliked her intensely, and who had overheard a dispute, which included the incriminating word, "Murder." Who would believe her story that she had killed him with poison which she had mixed, in error, for herself?

"I must do something," she said desperately.

Then she shook her head hopelessly. Calling for help would be useless. The doctor was away, and the hostile housekeeper would only complicate her trouble. Besides, she knew that it was too late to try to administer antidotes.

Her brother-in-law must have died almost immediately—and in agony. As she remembered the creaking springs of the chair, which heralded the first spasm, she crashed completely and dropped down into darkness...

IT seemed to her that she had been falling for years, yet

still went on sinking. Deeper and deeper, while the blackness

thickened around her... All at once, she became conscious of

faint sounds in the void, which reminded her of homely

things—the cooing of pigeons and the ticking of a clock.

She smelt a familiar odor compounded of jessamine and drugs, as

she opened her eyes.

She was sitting in the same chair in the dispensary, as when she had felt herself growing drowsy. Her hat and bag lay beside her, just where she had thrown them after she had first entered. In front of her was a calendar, which displayed the date.

It was Midsummer eve. And she had been asleep.

The compensation of an evil dream is the relief of waking up. Although she was still feeling the effects of her crash, Merle laughed joyously.

"Lewis went to Australia," she said. "And he couldn't fascinate anyone—let alone rich widows. Except my poor Marvis, and she was spellbound. But I know where the Borneo part came from. I was staring at that."

A journal, dealing with tropical disease, lay on the table, displaying the word "Borneo," in heavy type, above an article.

In spite of her happiness, some of the horror of her dream remained. She felt apprehensive and feverishly anxious to see Puck and know that all was well with him. Ramming on her hat, she hurried from the dispensary. She ran most of the way home, so that when she reached the bungalow, she was in a state of utter exhaustion.

Mrs. Megan Thomas broke off her song—for like most Welsh people, she was a tireless vocalist—when she opened the door.

"Oh, my Heavenly Father," she gasped. "What's happened to you?"

"I was knocked down by a car," gasped Merle. "How's Puck?"

"Lively as a flee."

"Thank heaven... Anyone called about him?"

"Of course not... Now you drink this, and off to bed with you, my lady."

As she was unaccustomed to stimulants, Merle was practically drunk when Mrs. Thomas undressed her and tucked her up. She lay through the night in a heavy dreamless sleep, and awoke carefree and refreshed.

AS she lay and listened to the cheerful sounds of an awakening

world, she watched the curtains blowing into her room, and the

green flicker of a beech-tree shaking against a windy blue sky.

It was a day when it was good to be alive. She heard the

milk-cart on the road and the welcome rattle of china from the

kitchen, while she waited for the reassurance of a child's voice,

to tell her that the angels had not called for Puck during the

night.

It came almost Instantly—the protesting squeal of a young autocrat disturbed in mischief. The next minute, the door was burst open and Puck rushed into the room and hurled himself on her bed.

To an unenlightened eye, he might appear an ordinary small boy in a thin vest and panties; but when he hooked his arms around her neck, Merle knew that she held the world's wonder.

He was followed by Mrs. Thomas, with the tea tray.

"What did you have for breakfast?" Merle asked him, knowing his passion for important words.

"Partridges," he replied promptly.

"Porridge," explained Mrs. Thomas. "You don't eat partridges in summer, Puck."

"But it's winter, today," he assured them, glancing out of the corners of his almond-shaped blue eyes. "I made it 'fair and frosty'."

"He's been playing with the barometer again," groaned Merle, feeling that she need not have worried about angel visitations. "Have you broken it again, Puck?"

"Not much," he replied virtuously. "Not nearly so much as I did last time."

Mrs. Thomas and Merle smiled at each other when their young lord and master had scampered from the room to find the puppy whom he really adored.

"Fancy sending him out to Borneo," said Merle. "I had a ghastly dream about his father yesterday."

Mrs. Thomas listened to Merle's dream with a creditable show of interest; but at its end, she sniffed with disgust.

"Pity you only dreamed it... Why, what's the matter now?"

To her consternation Merle had grown suddenly pale, while her eyes were dark with horror.

"Oh, Megan," she cried. "I've just thought of something terrible. Suppose it wasn't a dream? Suppose I really did poison him?"

"Oh, don't be daft," snapped Mrs. Thomas. "Did you give him rat poison?"

"Of course not."

"Then he's still crawling round in your dream. Only vermin-killer would make his sort curl up properly."

But Merle refused to be comforted. Her hands shook so violently that Mrs. Thomas had to take her cup from her, as she went on speaking.

"You see, when I woke up in the dispensary, I was so confused that I took it for granted I'd been asleep. I never looked around... But I remember now, that I must have fainted when I found out what I'd done. Suppose I was just coming to, after a faint, instead of waking up?"

Mrs. Thomas tried to scold, or laugh her out of her morbid fancy, without success; in the end, she decided to humor her.

"If you bumped off Puck's pa," she reasoned, "you must have left the corpse lying about. We know that housekeeper is a slummock, but even she wouldn't overlook a nasty trifle like that... I'm going to ring her up and ask her if she found anything out of its place."

Merle held her breath with suspense, while she listened to Mrs. Thomas' voice in the hall, where the telephone was installed. Her heart pounded when the woman returned to the bedroom.

"The housekeeper says you left your bag behind you."

"Oh, the blessed relief," cried Merle, laughing to keep back her tears. "What a fool I've been."

SHE left the bungalow in a gay mood that matched the sunshine.

As she walked down the avenues, every garden was fragrant with

roses. The river sparkled in the light as she leaned over the

parapet of the old bridge, and looked down at the slow

current.

She was swinging away with it, when a voice brought her back to earth.

"Morning, Merle. Day-dreaming?"

She looked up into the ruddy cheerful face of Captain Cliff. He was the club gossip, and, as usual, he had plenty of amusing tales for her entertainment. Presently, however, his expression grew graver and he lowered his voice.

"By the way," he said. "I heard that precious scoundrel—your brother-in-law, Gore—was back in town. I hope, for your sake, it's not true."

As Merle listened, she felt in the grip of a nightmare.

"No," she protested vehemently. "It's not true."

"Good. Some chap fancied he recognized him. I'm glad. It's not secret that you hate him like rat-poison, is it?"

The Captain strolled away, chuckling, while Merle gazed at his receding back, as though she beheld the Angel of Doom.

"It's no secret that you hate him," The words echoed in her brain as she began to run toward the doctor's house. It was like the Voice of the Town, condemning her with corroborative evidence. Only—she had not murdered him. It was a dream, from which she was not yet fully awakened.

When she reached the familiar door, it took an effort to ring the bell. While she waited for the housekeeper to come, she reminded herself of the reassuring telephone call. All the same, she moistened her lips nervously when at last, the door was opened.

No policeman stood in the entrance—only the slatternly figure of Mrs. Stock.

"The doctor's gone away for the morning," she said in a surly voice. "He says put off all appointments till the afternoon. And he wasn't back until nearly midnight. But I suppose he knows his business best."

"He certainly does, Mrs. Stock."

Merle's voice was firm, to hide the fact that she was vaguely worried by the unexpected absence. As she crossed the hall, instead of entering the dispensary, she nerved herself to open the door of the dining-room.

Her first glance showed her that the big chair was empty. No huge, distorted body lay stiffened there in its death agony. There was nothing worse than dead flowers in the vases and the usual signs of the housekeeper's neglect.

She started at the sound of Mrs. Stock's voice.

"Your bag's in the dispensary, if that's what you are looking for."

Convicted of trespass, Merle returned to her own domain of the dispensary, where indignation drove out every other emotion. It was only too obvious that Mrs. Stock had taken advantage of the doctor's absence to slack shamefully.

"She's not so much as shown it a duster," thought Merle furiously. "Her number's up, as far as I'm concerned. And she knows it. That is why she looks so venomous."

Although a note in the doctor's handwriting was lying on a table, she did not open it at once. After telephoning to the few patients who had appointments, she decided that she must restore some order before she could work. The wastepaper basket was stuffed to overflowing and had evidently been used as a communal dump for the rubbish from the living rooms.

As she picked it up, with the intention of carrying it out to the kitchen, she noticed some fragments of glass lying amid the dead flowers from the dining room.

Her heart dropped a beat, as she scooped them up to examine them. They were parts of a broken tumbler, to which a smear of sediment still adhered.

Her dream was true. She had actually given poison to her brother-in-law.

Feeling as though she had been sandbagged, she looked around her dully. By now, Lewis Gore's death was known, for someone had discovered the body and removed it. The most likely person was the doctor, who would do his utmost to protect her. It was even possible that his absence was connected with her interests.

The thought of his championship was her one ray of light. There was a wan smile on her lips as she opened his note, but it stiffened to a grimace of horror as she read it.

"I've just seen your brother-in-law. He spun me a lie about taking Puck out to Borneo, but I soon got wise to it. He wanted to be bought off again, and it was merely a threat to raise his price... Now, you'll be furious with me, but I knew he would only go on bleeding you, so I wrote him a final check, (I'll tell you how you can repay me, when I come back.) In return, I have his stamped agreement, appointing you Puck's guardian and renouncing all claim. I am taking it up to Somerset House, to get it stamped."

The letter made the tragedy doubly grim, by reason of its irony. It was torment for Merle to reflect that Lewis had already signed away his claim to the boy when he called yesterday. He was telling lies to try and get something extra out of her.

For some time, she sat, stunned by the blow. The telephone bell rang, but she did not stir from her chair. Presently she roused herself to speculate on her future.

She could not see any ray of hope for herself. Her fate would be hanging, or imprisonment for life. What jury would believe her story of a mistake, in view of the fact that the bottle was plainly labeled, and that she was accustomed to dispense drugs?

But her own fate was nothing compared with Puck's future. By the deed, now in process of being stamped at Somerset House, she was appointed his legal guardian. And she had failed him utterly. It appalled her to imagine what would become of him—penniless and left to strangers.

Even if the doctor took charge of him, for her sake—and she only assumed his affection for herself—it was natural that he would marry some other woman, later on.

In that dark hour Merle had to admit that she and Mrs. Thomas had spoiled Puck, even although, in their opinion, he redeemed their fondness by a hundred ways, just by being himself—the most adorable small boy in the universe.

But this practical hypothetical woman—the doctor's future wife would probably resent him as a usurper and pack him off to boarding school. On the other hand, if no one accepted his responsibility he would be sent to some institution, which would be worse.

And she could do nothing to help him—for she was going to be hanged.

THE idea was so fantastic and monstrous that her mind slipped

away on another journey. Although her brain was too blurred for

clear thought, it was apparent even to her, that, since the

doctor knew nothing of the tragedy, there remained only Mrs.

Stock to make the discovery. Remembering her dilatory habits, it

was likely that she found the distorted body in the chair only a

little time before Merle had appeared on the scene.

In her employer's absence she would notify the police, who had evidently removed the body to the mortuary. There could be no other explanation of the empty chair. Yet, as Merle thought of the housekeeper's grim silence, when she opened the door, and her denial of any unusual incident, over the telephone, she had the helpless feeling of being ambushed.

If she were already connected with the tragedy why had no official appeared to take her evidence? And why were the fragments of glass placed in the wastepaper basket? She always understood that—in a case of sudden death—nothing on the scene was allowed to be removed.

For a moment she wondered whether Mrs. Stock had smashed the tumbler herself, only to reject the idea immediately. Lewis must have swept it off the table in his death agony. But the mere fact that the pieces had been piled on top of the dispensary rubbish basket, where she could not fail to see them, seemed to indicate an attempt to trap her.

She knew that if she yielded to hex impulse, she was bound to incriminate herself. For Puck's sake, she wanted desperately to hide the bite ... Yet the first thing the police would look for would be the medium by which the poison was administered and they must have seen the broken glass already.

Perhaps they were in a conspiracy with Mrs. Stock to watch her own reaction. Although the dispensary was empty, she felt the unseen presence of a company of spies. Eyes were everywhere—looking at her through holes in the ceiling and chinks in the wall.

As time passed and nothing happened, she felt that she was being subjected deliberately to the torture of suspense—waiting for the inevitable knock on the door and the footstep in the hall. They wanted to break down her resistance, in advance. Yet she could do nothing else but wait...

Wait. Listening to the ticking of the clock—to the buzz of a fly on the window pane—to the throbbing of her own heart ...

"It must be a dream," she told herself.

If she hung on to this certainty, she might wake up and find herself in the warm gloom of the twilight dispensary, where she doped last night.

Only—this was reality. She was wide awake and the sun was shining on the trees outside. This was today—and she was powerless to recall the past.

SUDDENLY her heart gave a mighty leap. Her fingers gripped the

arm of her chair, as she heard footsteps outside the room. The

door was opened, but she did not turn round. She had reached the

limit of sensation, when nothing mattered any more.

"Merle."

It was the doctor's voice, tense with anxiety. "Are you all right?" he asked. "Mrs. Thomas has just been telling me about your accident."

"Perfectly," she told him.

"Did you get my note?"

"Yes."

"Isn't it fine news about Puck? Aren't you thrilled?"

"Yes. It's marvelous."

The doctor was in a state of jubilant excitement, when he accepted Merle's lack of enthusiasm as the result of her smash. He went on talking eagerly and rapidly, while she watched his face, without grasping the meaning of his words.

"Lewis confessed he tried to touch you first. But he said you gave him a drink and then walked out on him. So then he came to me.

"When did you last see him?" asked Merle.

"Oh, lateish. I had to get the lawyer to draw up the document, after hours. Oh, by the way, I ran Lewis up to London, with me, this morning, to clear him out of your way. I... What's the matter?"

In her relief, Merle broke down completely.

"Then he's alive. I didn't poison him," she cried.

As she sobbed out her story, the doctor's face, too, worked with emotion.

"You might have drunk that poison yourself. That's the part I can't get over," he said. "It was just touch and go that you are alive today."

Suddenly a chance sentence galvanized her to life.

"But he drank it—and he's alive too," said Merle. "I can't understand it all. I always thought you told me that potassium cyanide is a deadly poison."

"So it is. For heaven's sake don't try to find out for yourself... But the poisonous effect of the cyanide is due to a great extent to the fact that it reacts with the acid normally secreted in the process of digestion by the stomach to form a highly poisonous partial compound which is instantly absorbed... Now your brother-in-law suffers from chronic alcoholic gastritis—a form of dyspepsia in which the stomach fails to secrete acid. So like Rasputin—whom they tried to kill, in vain, by the same poison—he was immune."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.