RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

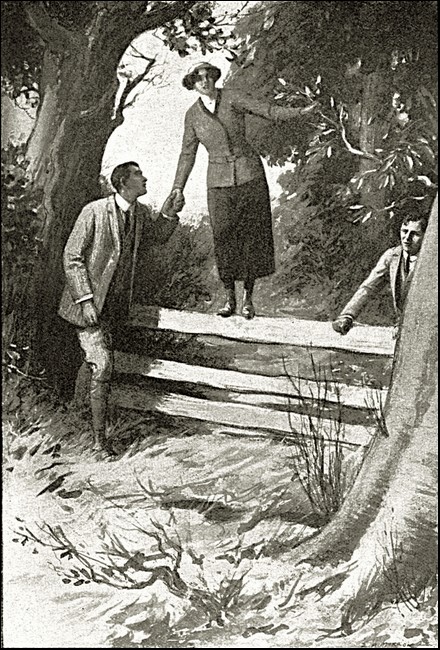

HE dropped it by the hedge, just as her foot slipped down the bank of the ditch. In an instant she picked it up again, with apparent unconcern—but too late for concealment.

The two young men, who were her companions, exchanged a look of horror. The elder swung her to a foothold on the browned grass of the field.

"Gloriously unconventional, all this!" he observed in formal tones. "By the way—would you mind? But what did you say your name was?"

The girl laughed.

"Hermione Rackham. And I didn't say it!"

Only convention—the lack of which Withers had just applauded—preventing him from groaning aloud. For as she uttered her name, his worst fear was realised.

Through their own folly, the young men had impaled themselves on the horns of a desperately awkward, and possibly dangerous, dilemma—where their future prospects were concerned. Even those who entertain angels unawares must have their satisfaction diluted with a wholesome feeling of awe. But in assuming that Miss Rackham was a common-or-garden dinner guest, Withers and Budd—ultra-smart and correct bachelors—had pledged themselves to literally entertain one who, by the flashlight of that unlucky incident, stood revealed as a stranger to celestial circles.

Outwardly, it was impossible to suspect her of a hidden bar sinister. Her oval face, its pallor accentuated by her dark eyes and waving hair, suggested purity and refinement in every line. Her trim costume, which combined utility with elegance, made her a striking figure on the field. Small wonder, then, that Withers and Budd followed her, instead of the hounds, in a breathless scamper over the fields, and, at the first check, instituted themselves her guides cross-country.

Small wonder, then, that Withers and Budd followed her, in-

stead of the hounds, in a breathless scamper over the fields.

Her pluck in negotiating obstacles, together with her staying powers, strengthened their fascination, and when they finally stopped, hot and winded, after having lost the hare, they all felt the glow of old-established friendship that comes from hours spent together in the open.

The last meet of the Harriers was the occasion for the social event of the year; an exclusive dinner, followed by a dance at Maple Hall, to those fortunate followers whom the Heather family considered worthy of the privilege. It was this highly-coveted honour that the reckless bachelors had conferred on the Unknown.

When Withers asked her, she raised her eyes, shining with pleasure.

"But can I accept on your invitation? Oughtn't Mrs. Heather to invite me?" she gasped out, still panting from her exertions.

Withers rushed to his doom.

"I assure you my cousin gives me a free hand in this matter. We make this affair informal, although, of course, no Dick, Tom or Harry on the field can slip in without being personally vouched for. My relatives are great sticklers."

"But how do you know I'm respectable or presentable?"

The question, asked in joke, was accepted as one.

The memory of this conversation recurred to Hermione as they plodded heavily, in their mud-caked boots, back to the lane.

"I'm just living for to-night, when you're to act as my social god-fathers."

In spite of the black shadow that draped her, her sparkling eyes were those of a beautiful girl, and Budd, in realising the fact, proved himself both youthful and masculine. He rose creditably to the test.

"I only hope you won't object to your name, and howl at the cold water. After all, meeting strangers is rather chilly work."

"I shan't object as long as you don't get into hot water."

"Why on earth should we?"

Hermione Rackham looked thoughtful.

"Honestly, I suspect you of being rather reckless," she said, glancing at his dare-devil blue eyes. "But I've accepted this charming invitation solely on the strength of Mr. Withers' word. I'm positive he could never do anything that wasn't the pink of propriety. Just look at that! Was it really once a boy, with a dirty collar and inky fingers?"

She nodded towards Withers, who was striding ahead, his profile outlined coldly against the blue sky.

Budd laughed.

"Beautiful, isn't he? Don't make fun of him for being so elegant. We're rather proud of him. A man with a future, only, unfortunately, just at present, there's a hitch.

"What's that?"

"Well, he's in diplomacy, you know." Budd spoke as though it were pork or leather. "And there's a lot of wire-pulling. Old Withers was to have had a splendid post jockeyed, or something. He'd have been made. Then his father goes and quarrels with Maybrick, the swell who engineers these things. So poor Withers is dropped, with only himself to depend on."

"Only that! Poor fellow!"

"Oh, well, it's hard lines. He's keen on Marie Heather, and the family won't hear of anything, unless he gets a clinking billet. Besides, he means to do well for himself."

"And no man does any good, unless he is an egotist, or is any good, if he is one," observed Miss Rackham drily. "Anyway," she added with a sigh, "your egotist is very good-looking."

Withers waited, to hold open the gate that led into the rutted lane. He spoke to Hermione with cold courtesy.

"Your car been following, with the rest, by the lanes. It will soon be round. Sorry we lost. You deserve a pad."

Then the chilly perfection of his face was broken into a beautiful smile of respectful homage and greeting.

Hermione turned swiftly to see what vision of radiant womanhood had exacted this tribute. But, contrary to the spirit of Romance, it was directed towards an elderly man, whose face, bleached and fragile as white egg-shell, was scored with lines of irritability and nervousness.

He acknowledged Withers' greeting with the curtest nod, as he climbed into a dogcart and drove off, in company with a dark, bearded man.

Withers' face clouded with disappointment.

Budd hastened to explain, in response to Hermione's look of interest.

"That's the great Maybrick I told you of. That man's got fine houses, and diamonds and motor-cars sticking out of his pockets, to give away to lucky people who can conjugate avoir and être, and smile nicely when they say, 'How-d'ye-do?' Those are the sole requirements for diplomacy, eh, Withers?"

"Funny, Budd?" Withers forced a smile. "No, the whole art is to keep a silent tongue. Eh, Budd? That's Lacroix with Maybrick," he added, turning to Hermione. "Foreign Office, you know. Both staying at Maple Hall."

"What interesting people the Heathers seem to know!" cried Hermione rapturously. "How glorious to think I'm going to their dance to-night. And all through you."

As she jumped into her smart car, her smile, directed at Budd, was, like most feminine missiles, badly aimed, for it hovered over the unresponsive Withers.

Left alone, the two young men faced each other ruefully.

Withers spoke first:

"Budd, this, is horrible! We've made a ghastly mess of it."

"You—Withers. One of your brilliant ideas to invite her."

"I admit it." The egotist unconsciously claimed a monopoly in brilliancy. "But I took it for granted that she was Colonel Long's niece. She was so charming, too. Who would have thought it of her?"

Budd nodded.

"You could have knocked me over with a feather when she made that slip at the fence. That first gave it away. I never noticed anything wrong before."

Withers bit his nails—an inelegant trick for a future diplomatist.

"Well, we've got to get out of it. She cannot—must not come to-night. It would simply ruin my prospects."

Budd scratched his healthy young cheek. Apparently, bad manners were catching.

"How can we avoid it?" he asked. "We can't drop her again, like a hot penny. It would be beastly bad form."

"Bad form?" Withers caught at the word. "But isn't it the worst possible form to introduce this—er—fascinating, but impossible young female into an exclusive family like the Heathers without credentials? They would be furious. Talk about letting loose a tiger among a flock of sheep. They'd never forgive me. And —there is Marie."

Budd nodded sympathetically.

"I know, old man. You're in a deuce of a hole. All the same, Withers, I am going to play the game. It's only cricket. I shall stick to this poor girl. We've let ourselves in through our own folly. After all, she's only a woman. Very likely, she errs through ignorance. And we're men."

He threw out his chest. His ruddy face was lit up with the chivalry that animated the knights of old—now resting, stony and cross-legged, in ancient English churches.

Withers could not be behind Budd in this new attitude, although he felt his knees give, in subtle sympathy with the crooked legs of those old stone Crusaders, when he thought of the coming ordeal.

Walking back to the Hall, he began to exercise his talents for finesse.

"We must formulate some plan, Budd. She must have no introductions. We must keep her dark. I fancy, if possible, we shall have to divide her up between us for the evening."

Budd whistled ruefully.

"It won't be a festive time. Tame sort of dance. I shall have to cut half my usual partners. What will the other girls say? What will Marie Heather think?"

Withers looked in positive pain. The recollection of a pair of dark, lustrous eyes, that had lured him to indiscretion, brought no comfort.

When they reached Maple Hall, the heavy velvet portière had barely fallen behind them, on entering, when the spirit of the house had them in thrall. Those muffling barriers that shut out every draught, were symbolic of the Heather attitude towards Society—Seclusion.

Mrs. Heather raised her eyes with the slow, languid grace that denoted a Heather. Her daughters followed suit, like a flock of sheep. All the Heather women were true to type—well-bred, cool and exclusive, with the long nose that stands for ancestors, when seen on the faces of Heather women, but merely means Jewish blood, when worn by those of lower origin. Marie Heather, although plainly one of the flock, possessed the necessary youth that labelled her a lamb, her carefully combed white fleece tied up with the blue ribbons of a family pet.

She gave Withers a look of welcome from pretty turquoise eyes. Mrs. Heather adjusted her lorgnette, which was a visible note of interrogation—the inevitable prelude to a question.

"Where did you part company with that very charming lady we saw you piloting this morning?"

Withers exchanged a guilty glance with Budd. It was evidence of his unimpeachable taste that they had accepted the lady without comment.

Budd answered him, with misplaced but admirable enthusiasm. He did not shirk the first obstacle.

"She's a stranger, staying at the hotel for a day or so. We've asked her for the dance to-night. Pressed her to accept. Withers gave his word that he was your representative."

Mrs. Heather smiled graciously.

"We shall be charmed to welcome a guest of Martin's."

Budd drew a breath of relief. Miss Rackham was formally accepted. But Withers' rigid face did not escape the attention of his own sex.

A man addressed him confidentially.

"What's up, Withers? You don't seem too happy. Nothing—er—wrong about the lady?"

"No. Oh, no. Should I ask her here if there were?"

"Then why do you look down your nose?"

Budd broke in with reckless daredevilry.

"Fact of the matter is, old Withers is a stickler for propriety, and this charming and fascinating lady has somewhat compromised herself in his eyes. This morning she slipped by a fence, and—dropped— something."

A smile appeared on every face, as a youth voiced the general reflection.

"Honi soit qui mal y pense."

Lacroix—the Frenchman—looked up with a puzzled air. Even the idiocies of English slang held no mysteries for hjm, but his linguistic talent failed to interpret this unknown tongue...

But the others translated with ease.

Withers raised his brows coldly at this offence against good taste. His sense of delicacy was aggrieved.

"Canaille!" he muttered.

Again, Lacroix looked puzzled.

"Come on, Withers! We must be off to change."

Budd took his friend's arm and led him up the staircase. At the top he paused, and glanced back down at the hall.

"Look at them sitting there," he said bitterly, "smiling as though butter wouldn't melt in their mouths. Yet they can make that poor girl's evening a perfect torment to her. All the refined tortures. Laceration of the nerves. Mutilated pride and hope. Yet she's a good and pretty young girl, as God has made her. Women are fiends."

Withers nodded assent. The Heathers were the cream of Society; they were utterly separated from the milk of human kindness.

"We must preserve her from their clutches," went on Budd. "Withers, it's up to us! Remember, I'm counting alone on your coolness of head and nerve."

Withers envied his friend's lightness of heart as the cheery whistle died away down the corridor. As he changed, drearily, he could hear the Woman's Champion singing lustily in his bath. The strains reproached him for his own dull weight of apprehension.

"Worth a thousand of me," he said to the nerve-stricken face in the glass. "No sign of the white feather about him!"

Feeling unable to face Marie Heather's tranquil eyes, in his present state of unrest, he worked himself up to a positive fever by pacing the limited length of a bachelor's room like a convict in his cell.

When he left his refuge, at the sound of the dinner-gong, he wondered how Budd had filled the interval.

"Like one of the French aristocrats," he reflected enviously. "Laughing, jesting—packing a lifetime of mirth into the few remaining minutes."

His forecast was correct in every particular. Budd had laughed, jested—and packed. At the present moment he was in the train, whirling back to town.

"Poor fellow, he was so upset at having to go!" explained Mrs. Heather. "But he had a telegram. Most important business. And his aunt is dead."

The future diplomatist smiled grimly. Budd had been desperate, when he made assurance doubly sure by that inartistic excuse. But the next moment anger overcame criticism. Now that Budd had deserted him, his position was not only difficult—it was hopeless. How could one man keep guard over a dangerous guest for the space of a whole evening?

He stopped cursing Budd's cowardly defection. He shot him out of his mind like a piece of rubbish. There was a consolatory touch in the reflection that his self-depreciation was vain. By standing his ground, he had proved himself a better man than the splendid Budd.

Although Marie was by his side, he ate his dinner with the sensation of a criminal enjoying his last meal. Tomorrow would see him cast out from the charmed circle of Exclusives.

Opposite to him was Maybrick. The great man, under the stimulus of the general excitement, had relaxed his rule of silence, and was relating anecdotes—all names carefully suppressed—in which he had triumphed over minor difficulties, by the exercise of superhuman tact and finesse. As usual, he took not the slightest notice of Withers, but he seemed to throw these exhibitions of skill carelessly at his sleek, well-brushed head.

"Take that!" he seemed to say, derisively. "Take that, you ornamental puppy, who imagine that a Gibson profile and a few French idioms are the only qualifications for a diplomatic career."

Withers grew more and more moody. He mentally put the all-conquering Maybrick in his shoes—reversing the usual order of promotion—and wondered how that brilliant brain would tackle his problem.

Unresponsive to Marie's prattle, he sank deeper in abstraction. Following the lines of a French idiom, he found himself on the trail of an idea that gave furiously to think.

When the band struck up in the hall, as a signal to the dilatory dancers, Withers took up his station near the door of the ladies' cloak-room. His imperturbable expression gave no clue to the anxiety that racked his heart. No-one could suspect that the calm, immaculate youth was desperately assuming the pose of a Machiavelli.

Presently Hermione Rackham entered the ball-room. Withers shivered at the sight of her, as though her pockets—which she did not possess—were stuffed with parcels of dynamite. Her beauty, enhanced by her gown of buttercup colour, looked exotic and Southern, but the light in her eyes was dimmed. In spite of her regal appearance, the gay confidence of the morning had departed. She glanced around her with the timid scrutiny of a wild animal, that fears a hidden trap.

At the thought of the contrast, Withers forgot his diplomatic schemes. Budd's sermon on the staircase recurred to him. Even though it was the Devil that rebuked sin, some of that fine deserter's phrases stuck. His joy for finesse evaporated before the recollection that here was a woman—and a woman in trouble. It may be that at that moment he had something more in common with an old stone Crusader than his rigid exterior.

Unfortunately for modern romance, the words with which he introduced himself as preux chevalier, lacked nobility.

"May I—'m—pleasure? Would you mind sitting it out? I have something I have to say—about myself. I'm afraid I must be an egotist—for once."

"Do! For once!"

In spite of Hermione's smile, it was evident she welcomed him as a friend.

"Where's Mr. Budd?" she asked, as Withers ushered her to an alcove.

"Gone away, I'm sorry to say. But, first of: all, I'm in a hole."

"So am I. Are you going to hide me in alcoves all the evening?"

"Far from it. There'll be a crowd of partners fighting for introductions before long. But—to return to myself, I made a bit of a blunder this morning. Over you"

"Ah!"

"Fact is, I'm in diplomacy. I've practically the refusal of a most important appointment."

Again Hermione smiled.

"And, in my position, that's a lot of social skill required. Got to remember faces, spot nationalities, and so on. Well, I flatter myself I can size up anyone on the spot, and when I first saw you this morning, I said to my companions, "I'll bet you whatever you like, that's a Frenchwoman!"

"I'm sure I don't look a bit French."

Hermione drew herself up, with a gesture of offended national pride.

"Oh, a wee bit, you know. Dark, spirituelle; and so on. But I admit I went chiefly by your dress. It had a Parisian air."

"A leather-bound skirt and nailed boots," said Hermione, suspiciously. But she was plainly appeased, and Withers hastened to follow up his advantage.

"They'll rag me no end when the truth leaks out. So I'm going to beg you to play up to me, and let me introduce you as the Marquise. No-one knows you, and it will be a fine score to take them in."

Hermione shook her head doubtfully. "But I know no French."

"Neither do they. Lacroix always speaks English, for he can't make head or tail of their French, nor they of his. They're rotten linguists. Insist on speaking English, and just say, 'Dieu!' and 'Ma foi!' and shrug occasionally! No one knows, until they try, the value of a good spoof. This may be a valuable opportunity for me to test human credulity."

Hermione looked reflectively at a pot of arum-lilies.

"Dieu! The Marquise wishes now to dance, ma foi!" shesaid presently.

The Marquise danced a lot. She was besieged with partners directly she appeared in the ballroom. As the evening wore on, her cheeks grew flushed with exercise, and her eyes sparkled with pleasure. The old radiant look of confidence returned. Her popularity increased in proportion to her added beauty. Everyone wished to dance with the Marquise. No-one attempted to reproduce Withers' reproduction of her full title, for it had a "ll" in it, and ended in "on"—pitfalls both, for blunt Anglo-Saxon tongues.

It was late in the evening before Withers was able to secure another dance with Hermione. Much water had flowed under the bridge since then, much champagne been drunk, many collars ruined. He pressed her hand.

"Congratulations. You've been a perfect success. A complete take-in. It just proves the value of bluff. Now, I'm going to leave you, once more, in a hole, while I forage for an ice for you."

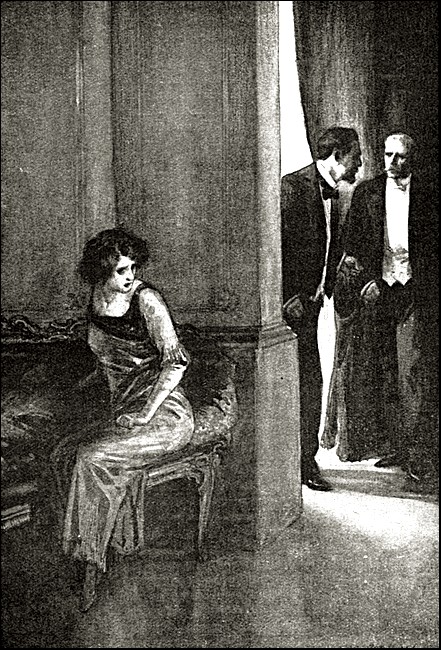

Hermione sank back in the alcove, grateful for the rest. She had barely settled herself among the cushions, before her solitude was broken in upon by two elderly men. Their faces were flushed— but not with dancing—and they talked rapidly, in French, with much gesticulation. They were the great Maybrick and Lacroix.

Hermione had barely settled herself among the cushions,

before her solitude was broken in upon by two elderly men.

At the sight of Hermione they broke off for a minute, but the Frenchman was plainly impatient to finish what he had to say.

Once again, he turned on his gigantic volume of talk in a sputtering flow of whispers, broken occasionally by the fluent, but more guttural interruptions of Maybrick. The noisy strains of the orchestra nearly drowned it, and the cheerful clamour of humanity, stamping in a two-step in close proximity to the alcove, made listening a fine art.

Presently, Hermione's face, which had grown dreamy, brightened into life as Withers, armed with a cherry-and-white ice, approached.

"Here you are, Marquise," he said.

The effect of his words was both electric and gratifying. The two great men, whose attention he had tried to woo for a week, sprang to their feet with an exclamation.

"Marquise!" cried Maybrick. "Is this lady French?"

Withers nodded. But in spite of his calm face his heart sank. He had never foreseen this contingency. The flock at Maple Hall was so select and well-chosen, that he had overlooked the possibility of Hermione's coming into contact with one of her foster-nationality. He had forgotten Lacroix. If he had remembered him, Lacroix was a non-dancing man, who effaced himself in card-rooms.

Exposure seemed inevitable.

Then he noticed that the agitation of the two big men exceeded his own. Maybrick had quite a pretty flush on his dyspeptic face, although his expression was distinctly ugly.

"Then—you have overheard our conversation?" he said, turning sharply on Hermione.

She answered promptly.

"Every word."

Lacroix made a gesture of despair. He thought he had gauged the linguistic incapacity of Maple Hall—the elder residents of whom could talk correct French about gardeners and penknives with other English people, who spoke equally correct French—unfortunately extinct in France—and the younger folk, who having been educated abroad, had congregated there in batches, and staunchly refused to speak other than their native tongue.

Maybrick, also, whose caution had outlived the attack of the champagne, did not forget this fact. He knew that only a native could have disentangled their fragments of rapid talk in the din.

And here—before them—was that selfsame native.

Withers, who stood petrified, saw with astonishment that Hermione was playing his own game of bluff.

"Yes, I heard. Every word. Valuable information, as you know. But everything has its price. You have a post that will just suit Mr. Withers. What will suit him, will suit me. For I'm engaged to be married to him."

Cold fluid seemed to be pouring down Withers' back as he heard the words. He had a vision of Marie Heather, daintily blonde, charmingly correct, white-fleeced and tied up with blue ribbons, like a valentine. In the baby-shop, her cradle must have borne the ticket, "Wife for a Rising Diplomatist."

Meantime, the dark-browed damsel, who was making diplomatists, faced Maybrick, with militant aspect. She stopped Lacroix's stream of expostulatory French with a gesture.

"I deal only with Mr. Maybrick. You know what I know. You know others will be glad to know it, too. Well, you know what will stop my tongue and make me in the secret. That post for Mr. Withers. And in writing, too!"

Maybrick paced the narrow space, his brow creased into angry lines. It was clear that he found the position impossible.

It was at this point that Withers, the unemotional, who had been having inspirations badly all day—counting from his unlucky invitation—received his crowning inspiration. He saw a way out of the entanglement. His level head distrusted the situation. He did not believe that important posts were to be bounced out of diplomatists by farce-like incidents. Hermione did not even know what post she demanded. At any moment the bubble might be pricked.

But, he saw his chance to demonstrate his special aptitude for such a post.

"Mr. Maybrick," he said, with his best smile, "this has gone on too long. I throw myself on your discretion. Your secret is still unknown. This lady does not know one word of French."

For the second time that evening the effect of his words was magical. Astonishment struggled with relief on the men's faces.

"But I gather, from the conversation, that you must have introduced this lady as being of French extraction," remarked Maybrick. "You called.her 'Marquise.' May I ask your object?"

Withers saw his chance.

"For Mr. Maybrick that question is unnecessary. This lady, whose acquaintance I made this morning by a happy chance, has already told you the reason—if any—with her own tongue."

A delicate shade of meaning underlined the words. Then he ironed all traces of anxiety from his features and awaited results. He could say no more. Everything depended on Maybrick's acumen..

He relied on a safe quality. The champagne had done its worst by now. He saw the light of comprehension dawn in Maybrick's keen eyes. It melted into approbation.

He held out his hand.

"Excellent! Mr. Withers, I congratulate you. And I should like a little chat with you to-morrow."

Withers thanked him with his eyes, which was the only form of gratitude available for what had not been promised with lips. Yet, in that careless nod, he knew a post had been given him.

The statesmen walked away, arm-in-arm. It was noticed when they re-entered the ball-room that they shook with laughter.

Left alone with Hermione, Withers faced her with some trepidation. In the hour of his exultation he remembered that he was a gentleman. Indeed, his constant recollection of this fact was his sole sign of low-breeding.

"I have to thank you sincerely for your intervention," he said. "With your permission, we will keep up the comedy of the Marquise till the end of the evening. Mr. Maybrick and M. Lacroix will respect our confidence. I have nearly won my bet, and shall owe you a debt of deepest gratitude. For the rest, of course, you were jesting. My personal affairs could not be allowed to interfere with matters of international importance. But, thank you, a thousand times, for your generous impulse. It was quite dramatic."

Sinking to his knees, he kissed her hand.

Hermione reddened at this act of homage.

"Was it so generous of me?" she asked. "You heard me tell them we were engaged."

In spite of the shock of reaction, Withers remembered again, in good time, that he was a gentleman.

"I am only too honoured," he said courteously. "Since you announced the engagement, I shall hold myself bound, until you—ahem!—throw me over!"

Hermione looked at him keenly. Then she burst out laughing.

"You are bold. I might take you at your word. And what would Miss Marie Heather think? But, no. You are safe. I'm sharp-witted enough, in spite of all, and I know what I owe you. I felt frightened out of my wits to-night when I got here, and heard the women in the cloakroom talking of M. Lacroix. They said, "He'd be impossible if he were not French. Only French people can drop their aitches and remain distinguished.' "

She fixed her dark eyes on Wither's abashed face.

And now, Miss Rackham's speech, which hitherto has been edited, out of consideration for the compositor, shall be reproduced, exactly as it left her charming lips, since she dropped her first aspirate by the ditch.

"You've be'aved like a gentleman. I guessed directly you 'ad invented this French title to save people being 'orrid to me. I've 'ad an 'appy evening. That was w'y I tried to do you a good turn just now. But as for being engaged to you—I'm already engaged to a man who's worth a 'undred of you!"

In his relief, Withers forgot that he was a gentleman.

He gripped her hands.

"'Ard lines. Oh, 'ard lines!" he said.

He had paid her the greatest possible compliment. For he, the cultured and correct—was unconscious of any lapse.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.