RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Two flying figures rushed out of the mist,

cut across his path, and disappeared to view.

Wherein Misfortune, Shadowing a Youth's Romance, Repeats

Itself on the Other Side Of the Globe With Strange Result.

CLIFTON RAY sang in his bath.

Although vocal exercise is as essential to tub ritual as soap and loofah, he had a special reason for his jubilant howl.

Tomorrow he was going away to meet Stella.

History repeats itself. As he splashed and gurgled, his memory reverted to the last occasion when he had sung in his bath as a preliminary to meeting Stella, and—had not met her.

Today he could afford to smile at his past bitter agony of disappointment It was over two years ago;—and thousands of miles away in his lodgings at Acton.

He remembered the bath—a deep one, enameled dark green. The wallpaper was covered with indigo splotches, intended for seaweed, and their reflections in the wavering olive water unpleasantly suggested tentacles aquiver to wind themselves round the limbs of the bather.

But this special morning, two years ago, the dark, sinister bath seemed asparkle with sapphire and foam, and he shouted like a young lord of creation. Overnight, at a Chelsea hop, he had proposed to Stella and had been—nearly—accepted.

She, too, had been borne along on the flood of mutual attraction; only she was pulled in the undertow of an opposing current. On the morrow she was going on tour to the Argentine, with a revue company, and her eyes were blinded with star dust.

She refused him, but refused him with a kiss. Then, lip to lip, youth had called to youth, so that she had relented and promised her final answer, a few hours hence, at the railway station.

On his return, Clifton, fearful to oversleep, had paced his rooms until the fateful dawn. As recorded, he sang in his bath. He caught his train with several minutes to spare.

And then—he ran into the unforeseen—a blinding fog on the line. The train crawled or passively waited the will of adverse signals. When at last he arrived at Victoria, he realized that it would be a close shave if he reached Euston in time.

The tubes were congested with the usual bottled-up crowds, resultant of fog. He decided it would be quicker to cross London in a taxi.

It proved not to be quicker. The roads were up and a block in the traffic held him motionless for minutes, raging in his cab like a trapped tiger. He looked at his watch; its hands were spinning around the dial.

He wondered if it would be quicker to leave his taxi and run to the station.

It would have been quicker; one leap and fate would have collapsed like an overblown paper bag.

He let the fateful moment go by. When at last he reached the station Stella's train was still waiting.

But, as he dashed on the platform, the whistle shrilled, the green flag was waved, and the tail lights of the train disappeared round the curve of the rails.

THEY wrote. There followed the complete tragi-comedy of letters, which crossed or got lost, or were forgotten to be posted.

Then the revue company went on the rocks in the Argentine, and its members were disbanded, with some disastrous results. But Stella had more than a pretty face; she had sufficient sand in her character to avoid the moral shipwreck of her companions. After a series of adventures she worked her way back to England. She wrote.

This was fate's signal to act. Clifton got promotion which took him from the city counting-house of the export firm where he worked as a clerk, and sent him to be assistant manager of one of the company's copra trading stations in a Pacific island.

He wrote.

Stella found England rather empty. She signed a contract for an Australian tour. She had won slight promotion from the chorus. She was given a song, although she could not sing, and a dance which she executed well. She also went on being beautiful, which she did better than anything else.

In his Pacific exile Clifton became obsessed of a jealous dread of the lords and millionaires who, to his ingenuous mind, followed the limelight lure of every actress. About this time Stella grew moody on the subject of the legendary beauty of dusky tropic belles.

They stopped writing.

A week ago the long silence was broken in a letter from Stella. It gave the date, five weeks hence, when she sailed from Sydney to London.

She said stage life had proved a disillusion and she was tired—tired. She called it "fed to the back teeth." In London there lived a certain worthy man of substance whose repeated offers of marriage she had always refused, because—well, because. If upon her return to England she became Mrs. Horace Smith, she intended to make this good, true man a good, loyal wife and forget all others.

Only she still loved Clifton, always, always.

"O, Clifton, come!"

Clifton took the letter straight to his chief, who had the reputation of being the biggest blackguard in the Pacific. Probably for this reason he understood and made every allowance for human nature. He arranged for a substitute and gave Clifton two months' leave of absence.

This time no slip could intervene.

The tramp steamer, the Prince of Wales, due for departure tomorrow, lay rolling in the dark blue trough of the waves outside the island. She would make Sydney within three weeks. This gave Clifton a margin of a clear week in which to get married and then return in triumph with his queen.

The whole island throbbed with a real romance.

So—Clifton Ray sang in his bath,

THIS time he could not sit down in his tub. Its bottom of spiked coral lay so far below him that the pale green water shaded down to a deep peacock blue. For his bath was a semi-inclosed pool in the Pacific ocean.

It was not too safe a spot for a morning toilet, for an occasional triangular fin was apt to appear outside the guardian reef. But the jade water of the safe inner lagoon was tepid and always fringed with a scum of refuse, so that Clifton had chosen this rocky basin, in preference, for his morning dip.

As he swam and sang he felt almost intoxicated with life. In a burst of jubilance he dived deep into the sparkling water. The crystalline light grew gradually to a grass-green gloom; he could see fish of grotesque shapes and brilliant hues darting from the caves and spiney projections of the coral reef.

Deeper yet. Tomorrow he was going to meet Stella.

From a cleft in the reef something had moved. A tangle of dark tentacles was slowly spreading out in the jade water, as though blindly seeking.

For a moment Clifton trod water as he stared at the waving trailers. He supposed it was seaweed. Yet it looked sinister and instinct with slimy life. He decided to dive no deeper. He was still comfortably remote from the object.

Suddenly a black whip shot out, within a foot of his head.

For a ghastly second he stayed paralyzed; then the spell was broken and he clove his way to the surface in a cone of silver bubbles.

Despite the sun, he shivered as he dressed. From the length of that one tentacle he knew he must have disturbed an octopus or devilfish of unusual size. He resolved to warn Findlay, his deputy, against bathing in the pool until his boys had fished up the monster. This must be done immediately, since Stella was an expert swimmer and would revel in his private bath.

"Stella!"

He shouted her name and the warmth returned to the sunshine.

He returned to his bungalow, littered with masculine lumber, and instead of the corrugated iron dwellings of the trading station at the other end of the island, he had elected to occupy a native hut, walled with saplings interwoven with sennit and thatched with plaited pandanus leaf.

In his fancy he transformed it for his bride. They would bring, from Sydney, a pink shaded lamp, big cushions, new records for the gramophone, and a trouser-press. He could think of no further details of feminine refinement, but trusted that Stella might supply a few ideas.

This morning he could not capture his usual rapture of anticipation. Every time he thought of that whiplike tentacle, almost grazing his cheek, he felt a chill at the base of his spine.

The fate he had escaped so narrowly tinged his mind with a faint melancholy.

"If I had gone out, now!"

DURING the rest of the day he was too busy for forebodings. His deputy, young Findlay, had to instructed in the details of the business.

After dinner, as they sat outside in the veranda smoking, Findlay suddenly recollected a message from Clifton's chief.

"By the way, just as I was leaving, some steam yacht put in at the harbor. Some swell party from Raratonga. Chief told me to let you know, in case you'd care to come over to the station. He was going down then to the harbor. He said he'd shake you down and you'd be on the spot, ready to sail tomorrow."

Clifton started up, his eyes inspired, his face rapt and almost beautiful.

"That's an idea! No!" He sank limply back again. "Better not."

"Why? What's bitten you?"

"Nothing."

Clifton was drenched anew with foreboding. Suddenly he thought of Acton. He knew things would go wrong.

He started as Findlay touched him on the arm.

In a clearing of the palms stood a native girl of unusual beauty. Her features, which were nearly free from negroid taint, looked ivory in the uncertain light. Her eyes of plum purple black were heavily fringed; her hair waved strongly about her shoulders. She wore a violet lava-lave and a single scarlet hibiscus flower over her ear.

As she smiled at them, in invitation, she looked the spirit incarnate of the tropics.

Clifton shook his head and she drifted back into the shadows.

Findlay made no secret of his disappointment.

"What'd you shoo her off tor? That was the prettiest jane I've seen."

"Was she?" Clifton yawned. "Brown girls aren't in my line."

"Mean to say you've never fallen for these island belles?"

"Not me. You see, my boy, I'm just going to be married."

"Poor devil!"

"Poor what? I say, I'm marrying an actress."

This time Clifton did not miss his effect.

"An actress? You? Got her photo?"

"Two. Come inside."

He swelled with pride as they examined Stella's photographs by the light of the insect-clogged kerosene lamp. One was a really beautiful studio portrait, while the other showed her in a charming and frank revue costume.

True to youthful type, the boys reserved their deepest admiration for the Stella of the beautiful legs.

"Of all the luck!" Findlay pounded Clifton on the back. "Good old bean. She's a ripper."

"Rather. And out of all those lords and millionaires, she chose plain me. What's yours?"

Back again on the veranda, their high spirits gradually petered out into silence.

Clifton's depression spread to Findlay.

"Hell! How will I ever stick in this bally spot? Ever seen it on the map? It's absolutely ghastly. Just a black dot, shoved inside acres of blue paint."

"O, you'll shake down. I did."

"You're different. You're going to be married.".

"Yes. Perhaps. Yes, of course, I am. Findlay, I've the most awful hump. Ever had a presentiment?"

"Rather. A bullet head means nothing. I don't mind telling you, I'm psychic."

"Well, once before, when I was going to meet Stella, something cropped up and stopped me. And I've an awful conviction that once again something will happen."

"Rats. What?"

"Don't know. But I know this. I'm taking no risks. I'm not going to sleep tonight. And I'll own up; I wouldn't go down to the station tonight, because I was afraid we might meet some of the yachting crowd and get asked to the cabin."

IT was true Findlay was psychic. He suddenly shed his depression and came to life.

"Afraid, Ray?"

"Yep. Last time a millionaire's yacht put in, there was fizz going and we all got lit and there was no end of a stormy night on the beach. Great it was." His face again assumed fleeting beauty. "And I knew that if there was 'boy' going tonight I couldn't resist it, and then I might get tight and miss the boat."

"Wouldn't they wait?"

"Wait? You don't know Captain Pearl. Cargo's all and the bally passenger just ballast. He'll wait for no one this side Jordan."

Findlay rose.

"You're perfectly right, old thing. Take no risk. Best thing I can do is to leave you alone. If I don't show up again tonight you'll know I've run up against some of the yachting party."

"Good luck, old bean," said Clifton wistfully.

The solitude of the hut remained undisturbed. Clifton sat chain-smoking, watching the stars marching in companies across the ebon skies. His brain was stimulated to extraordinary clarity, although he could not control its operations.

Of a sudden, he felt lonely. For a year he had lived on a tooth of coral sticking up through thunderous plains of ocean and had been unconscious of exile. For the first time he shivered under the solitude, not of one night, but of three hundred and sixty-five lonely nights and days.

It crushed him down. All around, in the swell and whisper, seemed to be something big which pervaded the darkness.

Fate? He thought vaguely of it as blind, blundering, with a million arms. Why else had fate separated him and Stella by merely a few yards of asphalt pavement and then thrown them together from the uttermost parts of the globe?

Yet now, in the dark immensity, he sensed a definite Brain, which shaped a human destiny.

He, grew rather frightened. In some confused way he wanted to propitiate that power, so that it would not crush him again. He was a trader and he wished to drive a bargain for his happiness.

What had he to trade?

He would make Stella a thundering good husband. But any beast of the jungle will protect its mate.

He would be honest and upright in business. But that was the dictate of self-interest.

He would—he hunted for a word—he would be decent.

Decent. But—suddenly, he found he was growing sleepy. The stars were multiplying and shifting over the heavens like metallic seed blown by the wind of eternity.

He caught himself up sharply in the middle of a nod.

This would never do. He dared no sleep. He....

His head fell forward on his breast. The cigarette slipped from his fingers to the crushed white coral gravel.

He was back in Acton, packing for a journey, with Stella at his journey's end. He could not finish his task. Time was passing, yet fresh articles lay always beside him, and not one could be left behind. He knew the train was-waiting at the station, but still be packed, packed.

The dream shifted. He was on his way to the station, an endless nightmare journey. His taxi first broke down in shapeless rubbish and then changed to a donkey cart. Presently he was afoot, running to catch the train, and the houses and lamp posts ran by his side.

AFTER hundreds of years he reached the station. It lay atop of thousands of steps. He toiled up, just in time to see the train shoot past him—its lighted windows running together in a golden streak.

He woke, with a shout of horror, to find himself in his chair, outside his hut.

"Hell! I've been asleep!"

He glanced at his watch, and then held it to his ear. It was still ticking. Five o'clock.

He drew a sigh of relief. He had two and a half hours in which to catch his boat.

Then he realized that he ached in every joint and that his teeth chattered from cold. He stared around him in petrified dismay.

The whole island was wrapped in a thick white fog which blanketed the sea. Every landmark was obliterated. The trunks of the palms showed only as faint gray filaments.

The fog. The unforeseen.

The island was, luckily, no paradise of creeper-laced forest heights and plumy waterfalls. He had but to follow the track by the sea and he could not fail to reach the other end. It was only his knowledge of the possibility of losing all sense of one's direction, in a London fog, within hail of one's doorstep, which made him respect three miles of muffled landscape.

He stepped out briskly, whistling, his eyes glued to the blurred white track where the coral spine of the island had chafed its scanty covering threadbare. He had only to hold to that.

Presently he stopped whistling in order to hurry while the going was good. At every step the fog was growing denser, building a solid wall of vapor across his path, so that he could see but a few feet distant.

He looked at his watch. It was best to hurry, for he was beginning to grow anxious about the track. Yesterday it had been one well-defined line, but today it had sprouted numerous unremembered tributaries.

After a while it forked distinctly. Clifton stopped to ponder and then cursed himself for his own question. He knew that what he needed was confidence—the surety that he was plowing the right furrow. That—and the knowledge that he had time in hand.

On that score, his watch reassured him with a margin of nearly an hour and a half.

"I can do it on my head."

He plodded on, following the path which he definitely knew to be right. After ten minutes or more it seemed to him he was striking upwards, away from the coast. He stopped to listen for the voice of the sea, but could only bear a muted whisper everywhere.

In a sudden panic he retraced his steps to the fork and took the alternative track.

That the first path was the right one, he discovered later, when he found himself slipping downwards on a perilous crack in the rocks. Flurried by the loss of time, he panted up the incline at top speed until he had found the fork—but not the original fork.

His confidence lasted until the new path entirely disappeared into the rough.

He wiped his face and looked at his watch. His nerve's were beginning to betray him, for its hands had started their old trick of spinning around the dial. He must hurry. Time was rushing away.

At the knowledge, his judgment entirely deserted him. Trusting to his sense of direction, he left the safety of the track and cut blindly across the rough in the direction of the sea, in the hope of picking up his original path.

Only, he did not go in the direction of the sea, for the ocean had entered into the illusionary game, lapping and murmuring in his face when it was in reality sucking at the cliffs behind him.

He went to pieces completely, coursing round in frantic and futile circles. He felt he was blundering in a lost world, somewhere in the fourth dimension, where Acton and a Pacific isle were one and the same place. At last he stopped, beaten to the knowledge that he was hopelessly lost.

He sat his jaws tighter. To abandon method now was to court madness. If he struck out doggedly, in any given direction, he was bound, in time, to reach the primitive harbor. Even if he had failed, he must not give in. He must fight to the limit— and beyond.

AT that moment the mist began to drift and swirl across his vision. A wind was springing up, shredding the fog to tatters. The wall of solid cloud before him ripped as though scratched with a talon, revealing a slice of heaving, soupy ocean, covered with white wisps, like the tangled hair of old drowned women.

And, just below him, reeling in the combers, blind drunk, was the Prince of Wales. Once more he was left behind.

The mist shifted yet more, revealing fresh vistas. Clifton gaped in astonishment as a familiar shape loomed at the end of one gap. It looked like his own hut, apparently not more than a quarter of a mile away.

New hope shot through him. Those blind wanderings, which had led him in exactly the opposite direction to his objective, might prove his salvation. The Prince of Wales was hugging the coast; she would pass close to the bluff where his hut was situated. If he could reach the reef where his canoe lay beached he could row out to the steamer.

He began to run. In five minutes he had run straight into his dream. It was a pure nightmare effort, with leaden soles and stabbing breath, while palm trees floated by his side and columns of mist whirled like dervishes before him.

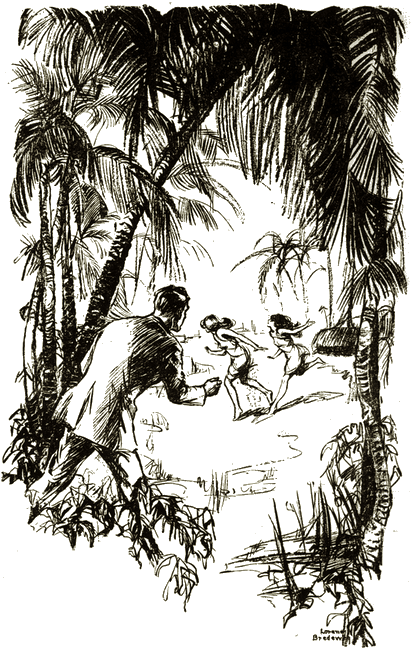

He had gained on the steamer. The hut was taking definite form, when two flying figures rushed out of the mist, cut across his path, and disappeared to view.

He saw one merely as an opaque silhouette, with flying hair and bare limbs. The other, however, in her scarlet bathing pareo, stood out in sharper relief. He recognized her as their nocturnal visitor—the flower-decked siren.

The mist swallowed them up immediately, but he located them by their laughter. They were climbing down to Clifton's private bathing pool.

He was plodding on, now almost dead to sensation, when he was, arrested by a grim memory. The horror that lurked in that pool. He must warn those girls.

He shouted. Again and again. But there was no answering hail. Stung to desperation by the thought of the Prince of Wales forging ahead of him, he ran on, only to stop again in indecision.

Was it necessary? All natives had nine lives in the water; they feared nothing that was in the sea. He ran on again.

Once more he halted. He thought of that girl as she stood, only last night, in the bath of moonlight, beautiful, and athrill. An exquisite work of the Creator. At the lowest value a life. And he thought of that same warm creature struggling in the tentacles of the loathsome pulp.

It was no good. It was a life. He could never be happy with Stella, if this morning's memory stood between them. He had to be—decent He had to warn that damned Kanaka girl.

"Of all the blooming luck"—he did not call it 'blooming'—"of all the—"

Somewhere, out there in the fog blanket, the Prince of Wales was heading for Sydney and Stella. Every minute she was tearing out the heart of an emerald wave, spitting it out again in a spill of foam.

He had lost Stella again.

He lost his manhood in that minute when he was all a man. As he slid down the weed-covered ledges, he half sobbed like a small boy whose treasures have been filched.

"Damn! Damn!"

The sun broke through the mist just as he reached the reef. It fell on a girl who stood, with arms extended ready to plunge into the pool. Those arms were ivory white and the hair that veiled her shoulders a golden fleece.

She turned, at his loud cry.

"Stella!"

They were in each other's arms, at last, clinging together as though they could never be parted. Stella laughed and cried—and because that was not enough, talked through both her tears and laughter, for so much time had been wasted and there was much to say.

"I was afraid you wouldn't come to Sydney. And then I made friends with some angelic Americans and they brought me over here in their yacht. I couldn't risk losing you again. Why didn't you come last night? I waited and waited, until too late. I sent a message by your boys. This morning I just couldn't keep still, waiting to see you, so I came for a swim. O, Clifton! I felt, if you came to me, you were fated to miss the boat!"

Clifton strained her to him closer.

"Yes," he said brokenly, "fate."

He glanced at the pool which sparkled in sapphire fire. Deep down under its surface, a long strand which looked like floating seaweed, showed as a dim purple shadow.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.