RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

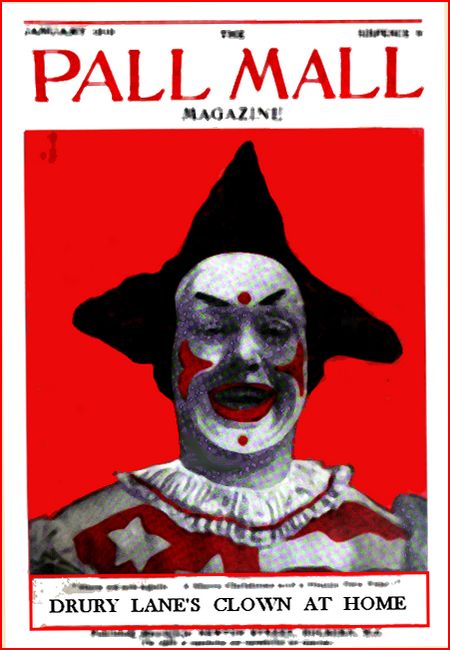

The Pall Mall Magazine, January 1910, with

"Le Roi Est Mort"

"SHE'S, she's—I don't know how to put it. But you know! She's not like other girls." The boy twisted his Panama hat between his kneading fingers. He was merely an ordinary, tanned youth in a white drill suit; further, something in copra. But, to Venetia South, he was invested with the sinister dignity of the Man with the Scythe. For he had borne the news that meant the deathblow to her career.

Deposed! The word burnt its way like a slow-match through her brain, as she languidly waved her fan, in apparent unconcern. In the rush of the warm Trade-winds among the plumed palms she heard its echo. The faraway murmur of the surf-song hummed the refrain. Deposed!

Hers had been a long reign. Ever since she had come to pass the days of her grass-widowhood on the little tooth of coral-reef, round which the great wash of blue Pacific curled and licked in unceasing swirl, she had established a rule of absolute and despotic monarchy. All the mankind of the island had laid their hearts at her feet, and then under them. All their womankind had acknowledged her power in a universal vote of enmity.

She rocked to and fro, her fan timing each jealous stab at her heart. A bewitching woman—despite the tide of her beauty was just on the turn. In defiance of custom, she wore a loose muslin robe, in the native style, and a wreath of scarlet flowers was bound in her hair.

"You can't think how ripping she is!" went on the boy. "She's so different, you know. Such slang—like a man—only she's every bit a girl. But there's not much chance for me. She's all the rage everywhere, and now Jardine has cut in—"

"Jardine!"

The fire suddenly broke through the smouldering grey ash. Venetia's eyes blazed, and her self-control vanished.

"Rather! Jardine's great at present."

Mrs. South looked at the boy with unconscious scrutiny—every detail of his appearance photographing itself indelibly on to her brain. She noticed the crop of freckles on his face—the gold stopping in a front tooth—the way his eyebrows met. Insignificant in himself, this was the straw that had marked the turn of the current.

When he had called that afternoon, she had gone through her usual course of procedure. Two fingers, a cup of tea, a draught to sit in. Then, stifling her yawns, she had waited for him to come to the inevitable point, and declare his love. And he had declared his love—his love for another woman.

When, at last, the boy had left her, Venetia sat for a

long time brooding, her chin down, and her head flat, in the

attitude of a hooded cobra about to strike. Clairvoyant at

last, she wondered she had not marked before the slow ebb of

the high tide of popularity. She had never troubled to join

in the social life of the island. The island had to come to

her. She remembered now that fewer men had drifted into her

bungalow during the past weeks. She had even received a call

from a woman, and had let that omen, as significant of coming

disaster as wax-moth in a hive, pass unnoticed.

Stung to a sudden frenzy, she sprang up and burrowed into her dark jungle of a room. Hopeless confusion reigned over everything. Several packs of cards, a bridge-scorer, cigarettes, loose music, empty tumblers and straws, dead flowers, red-skinned bananas, and cushions all lay scattered like the débris after an earthquake. A gilt clock from the Louvre had long lost its French vivacity, and settled down for life at four o'clock. Over all was a litter of photographs. All were portraits of men, and, with one exception, there was no duplicate. That exception, however, was significant, for the same face was pictured in nine different photographs.

Taking up one, Venetia looked at it closely. It represented a man with handsome, impassive features and sleepy eyes.

It was now nearly two years since Lord Jardine had stopped at the island for afternoon tea. When the yacht had called for him, six months later, he was still drinking tea, and had languidly waved his spoon in dismissal. Apparently the lying French clock and Mrs. South's charms had settled his course of inaction.

But Venetia, as she scanned the sleepy eyes, acknowledged the humiliating truth that, for once, the island gossip was at fault. Jardine, with his impassive calm, had completely baffled her resources.

Without warning, she felt an unaccustomed scalding behind her eyeballs, and a couple of tears ploughed their way through the layer of pearl-powder on her face. The next minute this advance-guard to an hysterical outburst was swiftly brushed away, as the woman caught sight of a white clad figure swinging up from the beach. It was the Trents' new governess, and the girl to whom the fickle island had transferred its allegiance.

As she approached, Mary Moon looked at the flower-wreathed bungalow with unwilling curiosity. Ever since her arrival she had heard rumours of the sinister and alluring charms of Mrs. South, but she had turned an indifferent ear to these lurid anecdotes. She was too soaked through with the charm of this tropical Paradise, too intoxicated with the delight and freedom of her new life, to worry her head about this enchantress of the island, who was apparently in the wholesale line cf me Circe business.

It was only since her rapidly-increasing friendship with Lord Jardine that doubts had clouded her serenity. She had looked at the inscrutable face of the big man—thought of the stories, and wondered—wondered. Then, she had tried her hand at cross-examination, with disquieting results. Jardine had hedged at first, but, presently, growing careless, had let slip admissions that testified to his appreciation of the charms of Mrs. South. Finally, with a yawn, he had dismissed the subject with the two words, "Ancient history."

As the girl looked askance at the bungalow, some one hailed her. "Do come in!"

It was Venetia South's voice that called from the verandah.

The Society Islands have been well-named, after all,

although the connection with their Royal Geographical sponsor

is chiefly to be traced in their remarkable and alarming

degree of latitude.

Yet, in spite of the universal friendliness, Mary Moon hesitated. Secure in her new-born happiness and joie de vivre, she was conscious of the fact that, if she owned the universe, she was not quite mistress of herself. Jardine's careless words had implanted a sting, and she felt the first stirring of jealousy.

Her eyes strayed past the gleaming emerald of the lagoon to the foaming outline of the reef. Outside were the breakers and the sharks.

Then she accepted her rival's challenge in a brief word, "Thanks!"

The woman looked at her closely and critically, as she stumbled over the threshold into the darkened room. She was a typical English girl—bonny and jolly—with ripe cheeks and trim waist. Venetia summed up her points coldly and dispassionately, bending her will to purge her mind of prejudice.

It was with a feeling of triumph that she put out of Court the two qualities she most dreaded—youth and freshness. Lord Jardine had not been attracted by the charms of Sainte Mousseline. There were plenty of young and beautiful girls in the island, and white muslin, although common enough, was more in request with the frivolous islanders—when embroidered.

Then, as she scanned the girl's trim outline, her neat, shining hair, and linen dress, she arrived at her conclusion. Mary Moon had won her supremacy by the potent power of starch. The fibres of her moral nature had been permanently stiffened to resist the soporific spell of the island, just as her skirts bore witness to drastic treatment at the wash-tub. She shone by contrast. At home, Jardine would have passed her without a backward glance. Here, after flabby morals and flimsy draperies, she was a spice of ginger in the midst of the universal insipid sweetness.

Venetia drew a long breath, for she was ignorant of the antidote to this Dew infusion.

Meantime, Mary had taken keen stock of Mrs. South. The

instant she had entered the room she had been assailed with a

strong feeling of repugnance. The air was soaked with

perfume; it clogged every square inch with its clinging odour.

Accustomed as she had grown to the scent of the South Sea

Islands, with its dominant note of tieré flower and copra,

Mary longed for a fan to sweep away this reck of a personal

essence.

It seemed to her, instinctively, that it had been sprayed about after each fresh exodus to sweeten the air of the bitter reproaches and curses of the victims of this Belle Dame Sans Merci. She knew that within these walls men's hearts had been bandied about in at game of pitch-and-toss—that youths had been stripped of their faith in womankind—that lives had been ruined and ambitions shipwrecked.

But, although she dimly felt the atmosphere of the room, in her young common sense Mary was inclined to believe that Mrs. South's reputation had been grossly exaggerated. To her critical eyes she looked incapable of playing the part. A wild-haired woman, with a powdered face, lying in a crumpled wrapper against a pile of amber cushions. She noticed, with stern disapproval, the yellow stain of cigarettes on her finger-tips, the dark pouches under her eves, and the good four inches of open-work stocking on the couch—unconscious that Mrs. South's minimum display was usually five.

The woman watched the girl's changing face, as her gaze roved over the picture-gallery of men's portraits. She smiled as she saw the frown and start with which Mary Moon encountered, in succession, the nine photographs of Lord Jardine.

"You're looking at my collection?" she asked. "I'm getting overstocked. Shall have to make a clearance, when I've the energy. Jardine, now—he's the worst offender. Always a fresh one. I suppose you've also loads? No? Then do take one—any one—to help me out! Choose!"

From the expression on the girl's face she saw that her shaft had gone home.

But Mary stood her ground. "I was looking for a portrait of your husband—that's all."

This time it was Venetia South that frowned.

"I haven't one—a photograph, I mean. But I wear his miniature, of course. The proper place for a husband is hanging round your neck."

"Like a millstone?"

Mrs. South concealed her annoyance with a laugh.

"Oh, my dear Ralph is more like a rolling-stone. Never at home. But, tell me—how do you like the island?"

"Perfect. I've never had such a glorious time before!"

Mary forgot her surroundings as she broke into a burst of enthusiasm. The dark walls seemed to fade to a mist, and she saw through them again the deep wash of the blue Pacific, the glorious orange sunshine, and the dazzling purity of the powdered coral beach.

Venetia, feeding her with careless question, heard more than her words, for her strained ear caught the bubbling undercurrent of the triumph-song of a woman in love.

She broke into the rhapsody with a jarring laugh.

"Goodness, how you enthuse! 'Thank God for life—thank God for love!'"

Mary, riding on the full wave of happiness, suddenly experienced a bitter flavour, like a swimmer who has swallowed a mouthful of salt water. She looked at Venetia, and noted for the first time, with an unreasonable pang of envy, the length of the lashes that outlined her eyes and the delicacy of her taper fingers.

"Very charming!" went on Venetia. "But have you ever thought that it all leads to nothing? All this picnicking, flirting, and lotus-eating? There's Jardine, for instance—He's been slacking here for nearly two years, but he's no earthly good to any one. He'll never marry in the island—now, will he?"

Mary faced the question squarely. "No. I suppose it is unlikely."

"Undreamt-of. Well, of course, it's all right for me, with an encumbrance already, but for an unmarried girl like yourself one naturally asks, 'What's the good of it?'"

Mary rose to her feet. She only wanted to break loose from this dark den, to breathe in the scented air, and to fall again under the spell of the eastern Pacific island.

Yet, at the doorway, something urged her to stop.

"I don't think you would talk like that," she said, 14 if you realised what—this—means to me—what sort of a time I've had before. At home—there was no money for dances or enjoyment. We just had to be educated to be independent. Then years teaching at a school, slaving all the time, indoors and out. Goodness! I feel a brute now when I remember how I bashed those wretched girls at hockey! Then, I had a slice of luck—a good private engagement. An easy time, but—my word!—the snubs. Only the governess! You know the sort of thing. And now, this—this glorious life; the freedom, the equality, the absolute perfection of living! But—I'm talking rot! Good-bye!"

As the girl stepped out into the rainbow-tinted world she was unconscious of the drift of her words. But Venetia understood. She had made an appeal.

The woman's mind swung back to the days of her own

girlhood, passed in the lively society of a garrison-town, and

contrasted it with the grey ash-path over which Mary Moon's

feet had prated So far—she had had everything! For

nearly two years Jardine had been her possession, even though

he preserved the copyright of his emotions. Should she grudge

three months of aim to the girl—six, at most?

She fought it out during the days that followed, but when the moon had ridden into the sky for the seventh time she declared the ultimatum of that empty week. War to the knife!

During those long, idle hours the truth had slowly eaten down to the bone, like acid. She was deposed! Only one or two courtiers of her defaulting retinue had straggled in to see their former idol, and, in their manner, she had read the writing on the wall. They were frankly sympathetic, and, telling her she looked a wreck, advised a change, unconscious of the change that had wrecked her life. She looked at herself in the mirror afterwards, and loathed the white-faced woman that glared at her from the glass.

Small wonder that her charms deserted her after days of pacing her room like a caged animal, and dining principally off her finger-nails! Woman-visitors, however, she had as a crowning insult; and, although she hated their society, they served as her scouts and spies. They arrived primed with gossip as to the career of Mary Moon, the number of her dresses, the snowball-growth of her conquests, the infatuation of Lord Jardine. No one knew how hard the deposed queen took her reverses; it was impossible to tell from the weary set of her jaded face. In those days, when the grasshopper was a burden, she seemed beaten to the world. The fickle island society had hailed a new sovereign, and was shouting on all sides, "Le roi est mort! Vive le roi!"

But, for all her inaction, and the verdict of the club gossip, Venetia South had not received her coup de grâce. She lay in her den—perdue—like a wounded tigress, but her mind was busy with schemes for a last desperate rally. She knew that it was impossible to regain her position by a slow siege; the facile fancy of the South Sea Islanders must be taken by assault. She fixed the date of the encounter and the battle-ground without hesitation. At the bachelors' ball she would make her last bid for supremacy.

But the weapon? For days Venetia ransacked her wardrobe, until her floors were layers deep in littered laces and muslins. She could find nothing to suit her ends. White she tabooed, for she guessed instinctively her rival's choice, and she dared not risk a brush with her glorious colouring. The rest of her things were rags, off-colour and shop-soiled, like the spoils of a remnant sale. She longed, from the depths of her soul, for a Paris creation, with which to kill competition, after the manner of a Kipling heroine.

Then, thrown back on her resources, she ransacked a pile of old Sketches. The total yield of their torn and soiled covers was a coloured picture of the dancer, "Eldorado," who had set the Thames on fire and made things hot generally in London, a few years previously.

Venetia stared at the costume with fascinated eyes. It was absolutely alluring and startling. The daring draperies, their filmy transparencies, their foaming poppy sheen, their spangle of barbaric gilding, inflamed her imagination.

She sat brooding over it for hours. Should she copy it? In England—apart from the lime-light—the costume would be frankly impossible. Here, under tropical skies, the temperature was, presumably, warmed to sufficient height to resist a shock.

Venetia tore her eyes from the tempting thing. She knew that to appear at the dance in that costume was to play the game with loaded dice or marked cards. Then, as she met the sleepy stare of Jardine's pictured eyes from nine different points of view, her last atrophied scruples were sloughed like an old skin.

* * * * *

THE magic of a tropical clime was at full strength on the night of the ball. The sky was pricked with golden stars, fireflies caught in the purple web of darkness. Down below, however, the fireflies flashed free, as lights darting hither and thither proclaimed the festive exodus from villa and bungalow to the illuminated club-house.

Mary Moon was one of the earliest to arrive. She looked a charming English export in her white dress, which, although a day behind the fair in England, was the latest fashion that had arrived at the Eastern Pacific.

As she surrendered her card to an Increasing ring of partners, her thoughts reverted to the last time that she had worn that gown, at a county ball, at home, when she had been a most tenacious wallflower.

The contrast heightened her triumph. Then, as Lord Jardine commandeered her card, the rose on her cheek deepened. It was evident that he also anticipated pleasure from the evening, for his glance was almost alert.

As they began to skirmish over the number of dances a name caught her ear. She turned, and saw a couple of women, who were gossiping to a youth.

"Fancy! I hear Mrs. South is turning out to-night!"

"Silly woman! She'd better lie low, if only to save her face!"

"Oh, you never know!" laughed the boy. "There's life in the old dog yet."

The old dog! Thus yapped the puppy. Yet, in feeling a pang of pity for her prostrate rival, Mary could not quite banish a guilty sense of joy on the score of the Jardine episode. Then she noticed that the boy, who was underhung, had further slipped his lip.

"By Jove!" he murmured, gazing at the doorway.

Instantly the women's heads swung round as on a pivot. At the same instant, Jardine drew a quick breath. Glancing up, Mary saw that he, also, was staring in the same direction. She turned swiftly, with a sense of coming disaster.

Attired like a pagan goddess, an Eastern dancing-girl, an oriental queen—whatever they chose to label her—Venetia South swept into the room, and at her appearance every scruple was licked up in the fierce flame of admiration that she kindled. Mrs. Grundy died before that scorching ray. The women gazed at her with fascinated envy, and the men slipped back to prehistoric aeons, and invoked, with unconscious faith, a pagan deity.

"By Jove!"

It was the murmur on every lip, bare or thatched.

Mary Moon stared with wide-eyed dismay. Was this the woman whose charm she had despised? She failed to recognise the yellow-faced, faded belle in this glorious creature. She was barbaric, splendid, wicked. Every bit of her—the garlands of scarlet blooms on her dishevelled hair, the flaming draperies that apparently hung together by enchantment, the rouge that blazed on her cheeks—was a challenge to the senses and a menace to the conventionalities.

Then, the low-drawn breath was relaxed, and a buzz of voices hummed free. Mary heard the low whisper of the planter's wife behind her.

"That's playing the game too low. If I catch my old man dancing with her—"

But she spoke to the empty air, for the youth had gone blundering over to Mrs. South.

With a sinking at her heart, Mary looked at Jardine. She hardly recognised him. His cool, impassive face had broken up before a flush of deep excitement. His eyes were alert. For the first time Lord Jardine was awake.

Hardly conscious of his action, he handed her back her card, with a mutter of thanks. Then he steered into the throng in the direction of the maelstrom that spun round Mrs. South. The next instant they were whirling round the room in the embrace of a waltz.

The girl hardly knew how she blundered through the dance. An east wind had swept through the tropical warmth of the ball-room, blighting her triumph. She could only feverishly wait for the next valse, against which Jardine had placed his initials.

It came at last. The band struck up, and Jardine floated by—again with Mrs. South.

Mary sat alone for the space of a minute only, before another partner secured her, but in that moment the iron entered her soul as she caught the flash of exultation in the eyes of her rival.

Venetia glanced at the white, girlish figure almost with derision. In the intoxication of her triumph the game appeared too simple, the foe too unworthy. A mere school-girl to flatten! A bread-and-butter flapper! She had crushed her to powder beneath her French heel. The world had come back at the first crook of her finger.

She laughed aloud, and Jardine laughed in answering excitement.

"Let's sit out!" he said. "I have something to say."

She looked with triumph at his transformed face. With an inch less bodice and two shades in depth of colour, she had achieved instantaneous success after two years of failure.

Yet when they sat alone under the murky glow of a swaying Chinese lantern, Jardine played idly with her fan and remained silent. The whisper of the far-away valse murmured a benediction. The sleeping island turned in her slumber, and they caught the perfume of her heaving breaths. Magic was loose in the air.

"What a night!" breathed Venetia. Then she promptly put the test-question that was hot on her lips.

"How do you think your new flame is looking? Miss Moon."

Jardine roused himself with an effort.

"Who? Oh, yes! Mary Moon. Quite nice. An ordinary enough little girl! See scores of them in England."

Venetia relaxed her breath. Her task was accomplished, and Mary Moon had taken her proper place in the scheme of things.

"What are you thinking of?" she asked, as, in spite of his tense expression, Jardine seemed looking into space.

He gave a laugh.

"Sorry! My thoughts were thousands of miles away. Odd to think that somewhere on the atlas—high up above all this waste of blue paint—is grey, drizzling England. Bet you anything, it's raining! Slippery pavements. Hansoms and taxis. The lights of Leicester Square. Can't you see them?"

"No!"

Venetia's voice was sharp. Jardine was in love with her. His every look in the ball-room proclaimed his newly-lit passion. She had brought him here to make his lips redeem the promise of his eyes.

"No," she repeated. "We're here. That's enough. Here, in this enchanted island. You and I. Why do you bother about England?"

"Why not? I'm going back."

The scented universe slipped under Venetia's feet. The stars above wheeled dizzily in their struggle to preserve their places.

The woman's voice came in a thin scream.

"You're not going back? You're not! You—you couldn't be so cruel as to desert us—this lovely island!"

"This lovely island, as you call it, is about played out. I'm fed up with reef and palm. I go by the next boat. Surely, you never imagined I should stay here always?"

Venetia gasped under the blow. She could not imagine the

island without Jardine. Its charm peeled off at a touch. It

stood revealed as an isolated, aching spot of exile. Blue,

heaving hummocks of Pacific Ocean rose interminably to

separate her from the fog-bank of far-away England.

Utter bewilderment swamped her faculties. She could not think. She tried to grapple with the appalling fact.

Jardine was going away!

Then she broke out into an incoherent torrent of entreaties, exhorting the charm of the islands.

"You won't go. This is nothing but a freak. You've eaten 'foi,' and you'll be back next boat. Think cf the freedom, the glorious climate! You'll miss that. And the picnics, the reefing, the bathing, the delightful time you've had lately with that jolly girl, Miss Moon! That fresh, charming girl! She's brought new life into the island."

In her desperation she was pushing forward her rival into the game, like a little white pawn—exploiting her charm, her attraction. Anything to pin Jardine to the spot!

He shook his head. .

"It's awfully good of you to be so persistent, Venetia. You've all been perfectly ripping. But—if I wanted to—and I'm fogged on that point—I couldn't now. Couldn't stay. I'm drawn away—dragged home!"

There was silence. Then Venetia whispered huskily:

"Who has done this? A woman?

"Yes. You!"

Venetia's brain reeled. Roller after roller of blue ocean passed before her eyes in never-ceasing movement.

Then she made a great bundle of the tattered remains of her traditional furniture, every remnant of her inherited dignity, every vestige of her school polish, every shred of her social training, and threw it to the winds. She caught at his arm.

"Take me with you!" she cried.

Jardine paused. Then, very carefully, he detached her clinging fingers.

"I'm sorry," he said coldly, "but there are two impediments to the course you propose."

"What—what?"

"To begin with—your husband."

"That—for him!"

Captain South was disposed of in a snap of two fingers.

"Secondly—my wife."

"Your wife! You are married?"

Venetia turned on him, with concentrated rage.

"You have dared to deceive me all this time!"

"If it comes to that, it's never been published in England."

Jardine's cool voice fell like lumps of ice on her hot heart.

"As a matter of fact, I came a mighty cropper over my marriage, and fled the country to escape the consequences of my folly. Came here to forget, and thought I had. Till tonight. Venetia, you graceless woman, you little know what you've done for me! When I saw you to-night—I saw more than you. Saw a pale image of the woman who has wrecked my life, broken me to bits. Eldorado, the dancer, and my wife!"

For a moment there was silence. Venetia swayed in her feat, as if to faint. Then, gathering together her forces, she rose and left him brooding in silent resentment.

He was awakened. He had to return—return to the old

slavery, the old enchantment. Against his will, he had been

aroused. But he could not sleep again.

The instant Venetia South appeared in the ball-room she was surrounded by eager suppliants. The band blared a triumphant valse. In one corner sat a neglected white figure. The fickle islanders had again made history. Their new queen was deposed, their old sovereign restored.

"Le roi est mort! Vive le roi!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.