RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

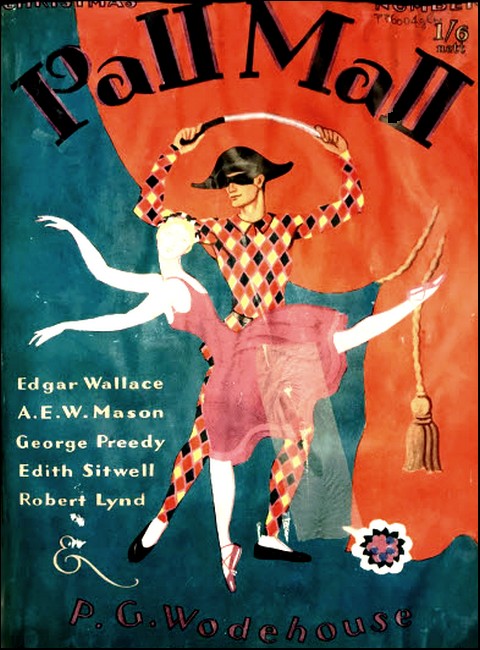

Pall Mall, December 1928, with "Silver Nails"

AS Dieudonné entered the hotel lounge, Ann Penrose—the musical comedy actress noticed, first, that she carried a huge doll and that her nails were silvered.

Then she, with the rest of the guests, held her breath at the woman's beauty and allure.

Dieudonné's skin was dead-white; long green eyes were fringed with a curtain of jet-black lashes. Her exotic charm was underlined by artifice for there was a greenish hint in her face-powder and her lipstick was crimson-mauve, to match the carnations she wore. Yet features and figure were flawless. Her costume preserved the hint of the bizarre in the snakeskin coat. A monocle veil, fringed with minute silver beads, softened her helmet-toque of mushroom suede.

Women regarded her with curiosity blended with envy, aversion, and—in some cases with positive fear.

These were the women who held their husbands on too light a leash.

For Dieudonné was both famous and infamous. As a cabaret star she commanded an enormous salary, which she earned as a box-office draw. A diseuse, rather than a singer, every inflection of her flat voice and least movement conveyed its subtle shade of meaning, which evaded the censor only by a hair's-breadth of ambiguity.

She made huge sums, but her expenditure was greater. This was always met—hence her reputation. She was famous for her extravagance, her jewels, and her lovers.

Dieudonné caught the gasp which was her invariable homage, and posed for a moment, motionless as a statue.

"Hold that," murmured the youth by Ann's side.

She looked at him, grateful for his flippancy. Sir Francis Webb was typical of his class—blond, block-shouldered and stolid. At the moment, he represented ballast.

For Ann discovered that she, too, was terribly afraid of Dieudonné—as must every woman be who had a man to lose.

And, since Sir Francis was Lord Hart's friend, she anxiously watched his reaction to Dieudonné. For life had taught her that, in fundamentals, men were much alike.

"Did you notice her nails?" she whispered.

"Not me. Are they in mourning, what?"

"They're silver. Look."

"My hat. Why not gold and bust the expense?"

Ann studied his face.

"Well, how does she impress you?" she asked.

Sir Francis looked weary and old for its youth.

"Just as a Press-Agent's big noise, That type leaves me cold. And her darned doll gets my goat."

"Why? They're silly, but one can't help collecting them."

Sir Francis shook his head.

"That's different. This doll has—personality. Looks like a potted portrait from hell of some of their choicest brands. Do you notice something special about it?"

Ann studied the doll. It was long-limbed and limp, and wore a beautiful facsimile of Dieudonné's toilette. Butits face was a horror from some opium-eater's dream—corpse-white, with evil, slitted eyes and a scarlet gash for mouth.

"Don't you see it?" asked Sir Francis impatiently.

"See what?"

"Her likeness to Dieudonné. She's her double."

Ann lost her fear. As one of the prettiest and most popular musical comedy stars, she had her full share of masculine admiration. But she was no man-eater; she cared as much for her following of gallery-girls as her faithful bodyguard of escorts to night-club and dance.

No man had attracted her until she met Lord Hart. Before he came into the title, he had travelled in many corners of the globe and worked at diverse trades. He had felled timber, shaken cocktails and acted for the films. He had travelled in a Pullman and underneath one, as a hobo. He had been entertained in an Indian palace and also in an American gaol. All these experiences had made him a good mixer, without encroachment on his reserve.

Sir Francis revived, like a wilted flower in sal-volatile, under the radiance of Ann's smile.

"You might let me make a foursome at your table," he pleaded. "Three is such a rotten ragged-looking number."

Ann nodded. Suddenly, she decided to make Sir Francis a test case. If she could hold him, she would feel more confident of her power to keep Lord Hart.

"Very well. Only, what will Lord Hart do when he comes down from the Pyrenees? When do you expect him back?"

"To-morrow. And he likes dining alone. He's that sort of solitary blighter. Crossing his fingers and just asking for it."

To-morrow. Ann's heart quickened by a beat.

"How does he ask for trouble?" she enquired.

"Because, you mark my words, when he does fall in love, he'll fall for a wrong 'un."

His words carried the ring of an evil prophecy to Ann. While intuition made her fear Dieudonné, common-sense told her that Lord Hart's rank and wealth made him marked prey for any adventuress.

"I don't believe you," she said. "Lord Hart has been through life. He understands values."

She broke off, as Dieudonné, preceded by hotel officials, approached the lift. It was like a royal progress, people parting on either side, to make room for her. The proprietor himself carried the doll.

As she passed by Ann, her glance skimmed her and flickered over Sir Francis.

Ann paled. In that second, she felt an intangible sense of loss.

ANN dressed for dinner, especially for Sir Francis, in iris-blue georgette which exactly matched her eyes. A plaited rope of small pearls encircled her throat. Sir Francis thought her adorable and broadcasted the fact to everyone in the restaurant.

"You're looking wiz," he assured her.

"Don't be absurd! How could a girl possibly look like a wizard?"

But the compliment made her glow with hope. She felt confident that she could hold her own with Dieudonné.

Presently Edouard—the maître d'hôtel, approached, and whispered to Sir Francis:

"Dieudonné has asked your name." Sir Francis glanced at Dieudonné, who was eating pilaff in solitary state, and than at Edouard.

"Well, don't you know it?" he asked. "It's the same as yesterday."

Edouard made an eloquent gesture.

"But, Sir Francis, it is a very great honour to be noticed by Dieudonné."

"I'm used to it. Tell her that in London I'm noted for my beauty and kept under glass."

Ann rewarded him with laughter; but, in spite of his bravado, she noticed a gleam of satisfaction in his blue eyes. During the remainder of the meal, he did not look exclusively at her. It made her reckless of consequences.

After dinner, when they went into the ballroom with the illuminated glass floor, she was at once surrounded by claimants for her dances. Against precedent, she gave sir Francis the unique honour of being her partner for the evening.

It was dangerous policy, for it drew Dieudonné's attention to herself. She knew that Dieudonné was aware of her existence. But fear for Lord Hart made her desperate.

The rest was easy. Sir Francis was enchanted with his monopoly of a footlight favourite. She kept him in her pocket for the rest of the next morning. They golfed together, until they were too hot, and then sat in a cool, tiled courtyard, gay with window-boxes of begonias, listening to the tinkling of a fountain and watching a parade of mannequins.

When Sir Francis implored her to choose a frock, Ann shook her head with a smile.

"My dear Franky, I'm not Dieudonné."

"Thank Heaven for that," was his fervent response.

Before they parted, she had arranged to bathe with him, that afternoon at the Port-Vieux.

She was first at the rendezvous, but was grateful to be alone, for a time. She dared not ask herself how the affair would end, for her conscience faintly reproached her with the truth that she was merely using poor Franky in her own game.

She shrugged her shoulders and lit a cigarette. Wiser not to think—but just drift with the minute. So near to Spain, she succumbed to the spell of their favourite word, "To-morrow."

Sunning herself indolently, she leaned over the stone balustrade of one of the triple-terraced bathing-cabins. Biarritz, swimming in light and colour, looked like a series of brilliant discs superimposed on a dazzling white plate—with its red-roofed villas, gay with window-shutters—green, yellow and blue. The sides of the bathing-pool were feathery with tamarisks against the deep delphinium sky.

She lazily watched the children, sprawling, like little lizards on the sands. Time slipped by. Presently, she looked at her watch. To her surprise, it was long past the agreed hour.

She stood, for a minute, frowning at the sea. Then, holding her chin high, she returned to her cabin and made a leisurely toilet. Just as she emerged again on the terrace, dressed in cool filmy white, Sir Francis—winded and overheated, rushed up the steps.

"Sorry—I'm—late," he panted.

"You're not," Ann assured him sweetly. "I arranged to bathe with you at three, not three thirty-five. So you are in excellent time for any other bathing engagement you like to make."

Sir Francis fanned himself with his hat.

"But—look here, I've been sweating like hell to get back to you. This ghastly sun's nearly bumped me off. I've been here, there, everywhere, all to find that infernal doll."

Ann's eyes narrowed.

"Had you to go and leave me in the lurch?" she asked.

Sir Francis gaped pitifully.

"Well, you see,she asked me. Dieudonné. She'd left the miserable object in some shop, and she wanted to play baccarat. She vowed the doll was her luck and she dare not touch a chip without her. It seemed positively caddish to refuse."

"Of course." Ann spoke evenly. "You're forgiven."

Had she not faced the truth at the back of her emotion, she would have wondered at the force of the blow. She knew that she did not care a fig about Sir Francis. But, as she looked at the brilliant scene, all the distinct notes of blue, red, and yellow ran together in a streaky mosaic.

She asked herself, what was the use of fighting? She had danced, smiled, played—cheapened herself with siren wiles.

And then Dieudonné bad merely lifted one finger....

CONTRARY to Sir Francis' prediction, Lord Hart did not return to Biarritz for a week. He entered the hotel lounge, one cloudy afternoon, to find Ann sitting pensively at afternoon tea.

A swift radiance flushed her face at sight of him.

"When did you get back?" she asked.

"Just after lunch."

She glanced at his flannels.

"And went straight to play pelota? What a man!"

"No. I went straight to find you. What a—what?"

"What a futile explorer. Why didn't you find me?"

Lord Hart sank down by her side.

"Presumably, because I looked in the wrong places. In every crowd. You are usually surrounded. But you look rather dim."

Ann winced.

"My holiday's up. That's all. And I've loved it so."

With Hart by her side, she could only feel happiness. But the past week had been a long-drawn out ordeal of foreboding, as she had been an unwilling witness of Dieudonné's series of triumphs. Against her own instinct, she studied her, trying to find the secret of her allure.

Other women watched her too, like tigers on the pounce. Some resented the fur or extra jewel, which should have been theirs, and which, presently, Dieudonné would wear. But others were withered by a deeper dread. One young bride—an heiress married to a society youth with an elastic heart—danced through her honeymoon, with haunted eyes.

"Where's Franky?" asked Lord Hart suddenly.

"In luck." Ann's voice was bitter. "Promoted to the Transport Service. There he is."

Her eyes, ever on the alert, had already seen Sir Francis through the glass of the revolving doors, following Dieudonné like a faithful hound. Competition was keen for the honour of carrying her assets, so Sir Francis was flushed with the pride of his burdens—two large cushions and the emaciated doll.

Ann fixed her eyes on Hart's face as he glanced at Dieudonné. She was dressed for 'le sport'—she, who knew but one. She had modified her scheme of cosmetics to suit her simple pleated jumper-suit of white crêpe-de-Chine, for her cheeks were olive and her lips carnation. Her legs, which were bare, were delicately sunburnt. From the white collar of her coat, her face arose like some beautiful flower.

Lord Hart's skin was tanned to the hue of old port, so admitted no change of colour. His eyes always remained inscrutable. Yet Ann thought she sensed a change in him.

"Who's that?" he asked sharply.

"Dieudonné. Now you know everything. Oh! What a shame! She's fleecing him again."

Ann flushed with indignation as Dieudonné stopped before a show-case in the lounge, and negligently pointed to an amethyst necklace.

Sir Francis manfully pulled out his note-case.

"He can't afford it," whispered Ann. "Yet he's never allowed to pass that case. He told me, yesterday, he's broke."

Hart merely laughed.

"Oh, we all go through that phase. Don't you realise that we all adore the woman who takes everything off us and gives us nothing? Curious. But there it is."

"No." Ann thought inconsequently of the mannequin-parade. "It's a lesson I've never been able to learn."

"Then you should go to Dieudonné for some pointers."

"Perhaps you're right. I don't seem to understand my business. No man has ever paid the rent of my flat. I've never even appeared on the stage in lingerie. And every penny I spend, I've earned."

Lord Hart did not appear to be listening. He was watching the comedy of the amethyst necklace.

As Sir Francis prepared proudly to clasp it around Dieudonné's throat, she pushed him back and held out the doll.

"But no. Put it on Mâti. It is her affair. They are hers. Amethysts for Dieudonné? I don't t'ink."

Lord Hart broke into a chuckle, as Sir Francis decorated the sinister doll. Dieudonné heard, and flickered an eyelash in his direction.

It seemed but a second later that Lord Hart was standing by the side of Sir Francis.

"Introduce me," he murmured.

Ann felt she could bear no more. In a panic she fled to her room. She stared at herself in the glass, which reflected her fair English beauty.

"No." She spoke to the blue eyes in the mirror. "If he cared for me, be can't care for her. And he did care for me. I won't believe it. I won't believe.

HER faith was severely tested that night. Although Lord Hart had returned, Sir Francis still made a dejected fourth at Ann's table.

For Dieudonné no longer dined in solitary state.

Sir Francis raised his miserable eyes to Ann's face.

"Remember what I said? That he'd fall for a wrong 'un?"

"A wrong 'un?" Ann rallied him. "With the name of 'Dieudonné'?"

"Don't pull that stuff! " Sir Francis spoke savagely. "We all know she's rotten as hell. Only—we can't go on without her."

Ann did not reply. Into her head had floated two lines from "La Belle Dame sans Merci."

"And whoso kisseth her on the mouth,

Knows no more hunger and no more drought"—

She could not understand such things. She could only sit and watch, as Lord Hart rose from the table and went from the room with his lady.

Although her official holiday was over, Arm stayed on a day, and yet another day.

It was fatal policy, for the papers were full of praise for her understudy, and, although a generous leading-lady, Ann could not afford to desert the limelight much longer.

She lingered, too, at the sacrifice of her pride. Her affair with Lord Hart had been conducted in the public eye, and paragraphs which coupled their names had appeared in the columns of gossip-writers. The same curious eyes, which had followed their flirtation, now noticed the transfer of his allegiance to Dieudonné.

Yet Ann would not give up hope. Again and again she drew out her store of memories; words, looks, the touch of ma hand. With such a man, these things could not stand for nothing.

She told herself that his infatuation for Dieudonné could only be a passing fancy. He was now her permanent attachment, at her beck to buy any costly trifle of her whim, and even to fetch and carry the macabre doll.

Sir Francis, with his empty pockets, was completely out of the picture. Once more, he sought Ann's company and they clung together in a camaraderie born of their mutual misery.

Ann made her health the excuse for a final reprieve. The date of her return was already advertised in the London Press. As a blind, she went daily to the big hydropathic establishment and sunned herself in a roofless cubicle, under its swinging screen. In between her visits she sought an opportunity to establish—at the least—some understanding between herself and Lord Hart.

The day before her last, she met him, by chance, as he was strolling through the orangery.

She stopped him resolutely.

"It's marvellous to see you alone."

"You, too. Where's Franky?"

"Five courts."

Lord Hart looked reflective.

"Do him good. Looks rather a wreck of late."

Ann nerved herself to force an issue.

"I thought you were fond of Franky," she said.

"I am. Quite."

"Then I only hope you'll never be fond of me."

Lord Hart looked at her.

"Meaning?"

"I mean, you've a curious way of showing your affection. You're making him simply wretched."

"How? Dieudonné?"

The unexpected question confused Ann.

"I didn't mean to bring her in," she said.

"Why not? Isn't she the beautiful lady who's causing all these tears?"

As be began to laugh, his amusement i roused Ann to fury.

"It may be a joke to you, but it's anything but amusing to the women whose men she steals. She's the lowest kind of thief. For she takes what they value, and what she doesn't want."

"Those good ladies should take more pains to keep their belongings," observed Lord Hart.

"How can they—with a woman like that? Don't pretend you don't understand me. SheBut you probably know the type better than I."

Hart smiled slightly as he nodded.

"Probably. To begin with, it's expensive. To be crude, Franky can't afford Dieudonné."

Ann felt a sudden glow at her heart.

"I understand—now," she cried.

Lord Hart was swift to grasp her thought.

"I doubt if you do. I imagine you're thinking along the lines of Browning's Light Woman. That situation's a bit overdone. Man—myself—in order to save his friend—Franky—from a siren, makes love to her himself. Consequently he loathes me, and I loathe her, and she lies in my hand like ripe fruit. Isn't that your idea?"

"Perhaps I hoped it was," admitted Ann.

"Sorry. But you're dead wrong. To begin with, I have the poet's assurance that Franky would certainly regard me as so much rat-poison. And, to end with, Dieudonné would never in this world, fall for me."

As Ann stared at him, in astonishment, he went off at a tangent.

"Talking of Dieudonné, have you noticed her doll?"

"I've noticed you carrying it about, like a lackey."

"That's nothing. I've done harder things than that. Stoked a liner, once. But the odd thing is that there really seems to exist an affinity between Dieudonné and her doll."

"I've noticed the likeness," said Ann acidly.

"Libellous."

Lord Hart broke off, as a stately silver-haired man came into the orangery, peering through his monocle, as though on a quest.

"Looking for anyone?" asked Hart.

The man gave a slight cough, but preserved his dignity.

"Not exactly anyone. A—a doll."

"Oh,Mâti? There she is."

Hart pointed to the doll which, clad in flamingo-red satin pyjamas—sprawled in a wicker-chair.

"Man is completely revealing," observed Hart. "One can imagine Dieudonné looking simple and chaste in a scarlet smoking-suit like that."

The man picked up the doll.

"She is looking charming. Many thanks."

Ann gripped her fingers, fighting her disgust. Directly they were alone she picked up the thread of their conversation.

"Why are you so sure that Dieudonné wouldn't fall in love with you?"

"Because she didn't before."

"Before?"

Ann's brain swam.

"And whoso kisseth her on the mouth...."

"Yes." Hart's voice cut through Ann's reverie. "When I was Franky's age. I went through the whole business. Of course, I hadn't any chance with her, then. But she's a woman one does not forget. I know this sort of thing seems impossible and—monstrous you. But you have no idea of the deadly fascination a woman like Dieudonné can exercise over a man."

Ann felt suddenly lonely, as though he had drifted a long way from her. How could she fight the years that lay behind?

"No, I cannot," she declared. "To my mind, that kind of attraction, without love, is repulsive. But, perhaps, you were in love with her?"

Lord Hart wrinkled his brow.

"I don't know myself. It's too complex. We are divided by the barrier of language. If I said to her, in her tongue, 'I love you,' or 'I hate you,' she would laugh equally. But I'm waiting for a chance to make her understand my true feeling for her. It will come."

As Ann sat silent, with frozen heart, he went on:

"But to return to Franky. Have you considered that I may want to save him from Dieudonné, so that he might find happiness with some girl who is really worthwhile?"

Ann recognised the personal note. It nerved her to seize her chance.

"That's kind of you," she said. "Yet— not so kind. For, perhaps, the girl might prefer Franky's friend."

Presently the silence was broken by Lord Hart.

"You always remind me of an English rose. Why don't you go home? It's your proper place. Green lawns and rain, not mosquitoes and scorching sun. You don't belong here."

"I am going back," said Ann. "Tomorrow's my last day.'

SHE hoped so much for that last day, because of the submerged light in his eyes when he called her an English rose. Yet, the hours passed and she saw nothing of him. He was not in to dinner, and Dieudonné, too, was absent in significant omission.

Presently, Ann noticed that diners at the far end of the restaurant were crowding out on to the balcony.

"What's the excitement, Edouard?" asked Sir Francis.

Edouard shrugged his contempt.

"The garden pavilion is on fire. C'est tout. But the one follows the other like a flock of geese."

"Let's see the fun, too," said Ann.

Sir Francis followed her to the balcony, where the blazing pavilion afforded a fine spectacle, as the flames shot up against the darkening sky and the pall of smoke revealed its fiery heart. A few of the hotel staff were amusing themselves with buckets of water, but there was no organised attempt at salvage.

The bureau clerk explained the situation.

"They have telephoned for the fire brigade. But before they come, there will be nothing but ashes. Never mind. It is insured.

Ann and Sir Francis waited to see the end. Each minute the crowd grew larger. Presently, the usual stir of interest heralded the approach of Dieudonné.

In spite of the counter-attraction, eyes turned to mark her toilette and her following. Two men were competing for her attention; one was the young honeymoon bridegroom—the other an aged financier who was adored by an invalid wife. The third man—inevitable as her shadow—was Lord Hart.

A ripple of admiration stirred the crowd. Dieudonné was dazzling in a creation of silver tissue, over which streamed a waterfall of jewels. A huge emerald gleamed from her silver turban and her eyes were green fire in the petal-whiteness of her face. As she adjusted a sparkling shoulder-strap, Ann noticed that the glare of the fire was reflected in silver nails.

Dieudonné regarded the burning pavilion with faint interest.

"Only this afternoon I rested myself there." Her lashes flickered in the direction of the aged financier, whose gratified smile proclaimed him her companion. "I would not care to rest myself there, now."

"Not with me?" whispered the financier.

She looked at his layers of chins and shrugged. "Too many dinners prevent you from making the big jump, mon ami. Oh, là-là! Her glance travelled on and rested on the thickset figure of Lord Hart.

"But you could make the big jump. Yes?"

He shook his head.

"Too bally hot."

He glanced at the pavilion, where the fire was reaching a spectacular stage. The whole of the centre doors had collapsed, revealing the interior. At the same time, the flooring of the verandah fell in, so that the building was cut off by a fiery trench.

"Oo!" thrilled the crowd.

Their murmurs were cut by a woman's shriek.

"Mâti. I forgot her. She's there!"

Dieudonné—a tragic figure—pointed to the pavilion.

"I left her in there. I can see her plain. The fire has not perished her. Save her! Oh, save her!"

For the first time, Dieudonné appealed in vain. The amused indifference of her audience aroused her to fury.

"Are there no men here?" she demanded.

A shiver of premonition ran through Ann.

Raising his brows resignedly, Lord Hart lounged forward.

"Any little thing," he murmured vaguely.

Ann stood in his way and tried to bar his path.

"You shall not," she cried. "Its a crime to risk your life for sawdust and wax."

Lord Hart glanced at her, and then brushed her aside, like a leaf.

"Sorry," he said.

His cigarette still between his lips, he sauntered down the steps.

As Ann watched him go, she felt frozen with shame. In that careless gesture, he had publicly repudiated her.

At the foot of the steps, he flung away his cigarette, and ran, at top speed, towards the pavilion. He took the untouched stone flight of steps in one stride, balanced himself on the top for a second, and then leaped the fiery chasm, where the verandah had been. Between two breaths, the spectators saw him emerge from the pavilion with the doll. The return bound landed him safe on the second step.

It was done with such apparent ease as to rob the feat of its glory. Yet, as he sauntered back to the terrace, the odour of singeing told how fierce had been the breath of the furnace. All realised that, had he miscalculated by an inch, or had his muscles failed in the least degree, he would have crashed down into a red-hot death trap.

As he approached, Dieudonné held out her hands for the unscorched doll. The triumphant glitter in her eyes acknowledged his supreme act of homage.

She turned to the guests.

"For you, it was but a doll. But to him, Mâti was Dieudonné." She turned to Lord Hart. "You saved her from the fire, because she resembled Dieudonné? Was it not so?"

"Exactly," said Lord Hart. "I look upon you and the doll as one and the same. Here she is!"

Doubling the doll into a limp contortion, he contemptuously hurled it on the ground at Dieudonné's feet, like rubbish thrown on a dump.

In the stunned silence that followed, he stepped forward to Ann, looked quickly into her eyes, and then kissed her, for everyone to see.

His action relieved the tension. As the guests grasped the significance of that abject sprawling object on the ground, they broke into spontaneous applause.

Dieudonné bent her head as she listened. The story of her humiliation would spread, like a prairie fire, from casino to cabaret.

What did it matter? She stared around her in brazen defiance. Everywhere was the gleam of eyes—women's eyes—from which the fear had passed, watching her.

Thumbs were turned down.

But other doors were open to her. Was she not Dieudonné? On the other side of the ocean were plenty of rich men—all hers for the least movement of a hand with silver nails.

Laughing, Dieudonné picked up her doll and walked away.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.