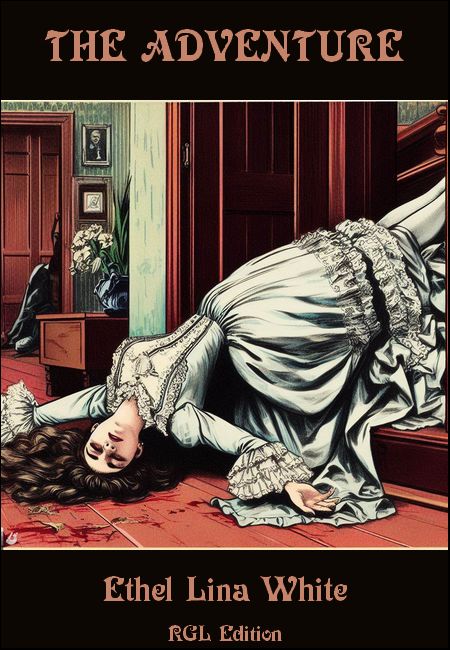

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

A CRASH, followed by a low groan, rang through the building.

A girl, who stood on the dirty stone stairs, clasped her hands at the sound. "An adventure!" she whispered. "It must be murder!"

But her voice lacked conviction. Even as she spoke, she laughed—the incredulous laugh of youth, that merely quested for a thrill.

All day long, her blood had rioted for an adventure. Spring pricked in the pulse of the year. Blades of purple and yellow crocuses pierced the sod of the City parks. The clouds were travelling at a tremendous pace over the pale blue of the sky.

From the top of her motor-bus, she had marked the stir of life in Nature and humanity, and it had moved her to discontent. She knew that things happened here—were happening even now, all round her. Crimes and adventures shot through the drab of uneventful existence with a streak of scarlet. But never to her; others lived—while she merely existed.

Thus it was, that, when the dusk gathered at the end of the street, in violet shadows, she found herself in regions where she had no earthly business to be—shamelessly chasing her dog up the stairs of a block of bachelor chambers.

She clasped him to her, when the sudden noise startled her from the chase, she had, herself, stage-managed. For several minutes she remained in a rigid attitude—half afraid that someone would come and discover her presence. She had slipped behind the back of the preoccupied commissionaire at the door, when she started her escapade, and she had met no-one in the course of her graceless journey.

Two minutes ticked slowly by and the sound was not repeated. Either no-one else had heard the disturbance, or else part of the building was unoccupied, during a process of re-decoration. She noticed a ladder reared against the wall, on an upper landing, while the air was pungent with a whiff of new varnish.

Tired of waiting, she turned at last regretfully towards the staircase.

"Nothing's going to happen after all!" she said disconsolately.

But she had only taken two steps when she halted, appalled by the programme before her. Outside was the drab street, a fourpenny meal—tea and toast—at a cream-and-gold Lyons, and a decorous 'bus waiting to jog her safely home to the suburbs. To round off the glorious day thus, reeked of sacrilege to the Spring.

In contrast to this dreary prospect there was a sense of guilty exhilaration about these forbidden precincts—this maiden's Thibet. She felt sure that behind these doors were rooms that had grown familiar to her through their presentment in West-End theatres. From her place in the pit, the little Colonial had often followed, with breathless interest, heightened by her inexperience—adventures of these Society people, who were so totally unlike the rough type of humanity she knew.

Now as she gazed around her, her imagination told her that in this building lived the counterparts of these stimulating-folk. This was the stage in real life; if she were only bold enough to ring up the curtain, the play might begin.

The Spring had her well in thrall, for a sudden gleam of audacity lightened her childish face.

"I will," she said. "There was a noise, and I can pretend—"

Without a pause for further reflection, she rapped sharply at the nearest door, and then fell back, aghast at the sound.

She heard the murmur of masculine voices. Before she could turn to fly, in sudden panic, the door opened, and she found herself looking into the face of a young man. It was too late to recoil; she had forced her adventure.

At first sight of him, she felt overwhelmed by her luck. Tall, handsome and well-dressed—the tenant of this room seemed expressly created to figure in a romantic episode. She decided that in the role of hero, he would be quite as good as Alexander—only better, and equal to Waller—only superior.

Then her heart sank to observe that he evidently did not share her rapture for his features were stiff with annoyance.

He stared at the pretty pink face and the homely grey gown as though he viewed a ghost.

"Well?" he queried abruptly. Thora's courage, ebbed under his hostile eye.

"I thought I heard something," she stammered appalled to find he did not take things for granted in the happy way of stage tradition.

"Heard something?" He stared. "How could you hear any sound—from the street? Blair, come here!"

The sight of the second man did not tend to reassure her. The lower part of his sinister face appeared to be swathed in a thin bluish scarf, so strongly marked were the signs of shaving in contrast to his pallid skin.

"But I wasn't in the street. I was here," she confessed.

Both men continued to regard her, without the smile she had grown to regard as the normal thing.

"You have no business here," said the sinister one severely. "I think you owe us some explanation. Please!"

Thora looked down at the floor. She felt sure they had exchanged meaning glances and she was not surprised. Well-brought-up girls do not, as a rule, amuse themselves by giving runaway knocks at the doors of bachelor chambers.

In her anxiety to clear herself of the charge of frivolity, she blurted out her preconcerted story, in all its absurdity.

"You're quite mistaken in what you're thinking. Common humanity only led me to your door. I felt it my duty to see if murder were being committed!"

The men stared at her helplessly for a second, then simultaneously burst into a fit of laughter.

"What were you going to do?" asked the younger man, at last, controlling his voice with an effort. "Take us in charge? Where are the bracelets?"

A fresh spasm of laughter doubled him up as he looked at the slight, girlish figure.

"Of course I wasn't going to do anything so silly." Thora's stiff voice suddenly began to run up and down its register, like quicksilver. "I-I merely meant to give the alarm. They would hear this in the street."

From the bag on her arm, she produced a policeman's whistle.

As the man regarded it with mock awe, she turned to him, appealingly.

"If you are a gentleman," she said—drawing on the theatre for inspiration, "you will kindly let me go now."

Then her voice gave way completely.

"I know I've made an awful fool of myself," she quavered. "But—can't you understand? It seemed like an adventure. I've never had one. And I've longed for one all my life!"

Confidences are indiscreet, but this time, Thora's impulse was justified by its success. The younger man forgot his mirth, and looked at her with sudden interest.

Under his gaze, the girl felt a faint thrill. Was this the prelude to a romance? It seemed to her that the instruments were tuning-up; at any moment the overture might begin.

A door banged overhead, and footsteps, were heard coming down the stone steps. The man startled at the sound and looked at his sinister companion.

Then with an abrupt movement, he turned to Thora.

"I believe some good angel sent you here," he said, speaking rapidly. "Do you really want an adventure? I can give you one now, and what's more, you'll help me out of a deuce of a hole. Will you? It's only to come inside and say you're my cousin. Play up to me, I give you my word of honour it's all right."

Thora hesitated. Now that the adventure she longed for, was being thrust upon her, she shrank back in indecision. Every scrap of home training, every "extra" at her finishing school and every ounce of maidenly prudence seemed to drag at her with irresistible force, straining to tug her feet down the staircase, away from temptation. But the magic of Spring rioted in her blood, clamouring for the claims of youth.

The man read her prolonged silence aright.

"Just look at me," he said quietly. "If you can trust me, then come! If you have any doubt, remain outside!"

The words appealed to Thora. Her confidence returned at the sight of his finely-cut face, tanned the colour of tea, and the candour of his blue eyes. She made her decision.

One hour of life!

"I trust you!" she said simply.

With an exclamation of relief, the men almost snatched her into the room and dumped her into a chair by the fire. One tore at her hat-pins in his efforts to remove her hat, while the other dragged to her side a table with unused tea-equipment.

"Look as if you'd been here ages," whispered the younger man. "Oh, and call me Jim!"

Thora nodded. She clasped her dog to her, enchanted with the wild rush and whirl. In one moment she had been transplanted from the commonplace world that pays two-and-six for the pit, and bundled behind the foot-lights. Her half-glance told her that this room was just such a one her fancy had painted—luxurious and artistic. She felt a positive thrill of joy to see the electric lights had the red shades hallowed to stage-settings.

There was a fumbling at the door handle and a head looked round the portière. With instinctive sense of drama, Thora stiffened for her cue. The moment had arrived.

Glancing round, she saw the other two actors had already got into their stride. The sinister one was lighting a cigarette, while her hero dug at the fire in the most natural manner.

The head at the door was followed by the body of the intruder.

Thora was seized with an involuntary spasm of antipathy; she felt glad that she had been roped into this conspiracy to baffle his curiosity. His pallidly unhealthy face, creased with disfiguring lines, bald head and prying eyes, shielded by rimless pince-nez, gave him something of the look of a vulture craning for garbage.

"Hello!" he said. "What was the row just now? Heard a crash and came down to hold an inquest. What's up?"

Thora reddened slightly as her hero threw her an amused smile. With a nod, he indicated a heavy oak chair that lay overturned in a corner.

"That's your crash," he said. "Blair and I were at grips over the hanging of—a certain lady."

He jerked his head towards the picture of a woman that hung on the wall. Thora had taken it for a fancy head, barely suggested by scratchy crayon lines and splashes of rose-madder draperies. But the eyes were alive and alluring—the eyes of a syren.

Who was this woman? The girl felt a throb of senseless jealousy as Blair spoke for the first time.

"I was trying to depose her," he said. "Bad art! Milton insisted on her retaining the place of honour. I bowled him over, and the chair."

"H'm!" The intruder seemed to sniff the air.

"And where's Maude?" he continued.

Maude? Again Thora felt the vivid morbid interest. Was this the name of the woman whose picture hung on the wall? She began to understand something of the nature of the mystery. She asked herself what she had to do with it, as she hung on Jim's answer.

"Hanged if I know!" he said carelessly. "Not here at all events."

"But I thought I heard—" continued the spy.

Jim cut him short.

"Considering I've been entertaining a lady—my cousin from the country—here to lunch—is it likely I should have other visitors? Sorry I can't ask you to stop, Candy! I'm neglecting my guest."

For the first time, Candy turned his short-sighted glare on Thora. He had ignored her presence before and there was a sceptical grin on his face as he acknowledged her existence.

He gave a slight start as he gazed, and the insolent light in his eyes faded to a stare of wonder. There was no mistaking the genus; country parsonage was written all over her person. Her little fresh face was so utterly unsophisticated, her grey dress so simple, her hair so pretty and yet so badly-done, that Candy glanced at Jim, almost with respect, for the possession of such an immaculate relative.

He took off his hat hastily.

"I beg your pardon," he said vaguely. "Er—early for the Academy, hey? So you've been here since the morning, hum?"

It was a thrilling moment for Thora for it seemed that the three men hung upon her answer. This was her cue to bolster up imposture. Although ignorant of the issues at stake, she was certain that much depended upon her.

"Let me see!" She spoke slowly and naturally. "What time was it I came, Jim? Change of air has made my watch mad."

"Twelve, you graceless country person! You've done me out of a meal. I've had a composite breakfast and lunch for your sweet sake."

Candy turned away, his interest vanished.

"Well, I was going to spend a couple of hours here before leaving for the Hook," he said. "But as you're engaged, So long!"

As the door slammed, Jim turned impulsively to Thora.

"You ought to be on the stage!" he said. "How can we thank you? And how clever of you not to commit yourself over the time!" Thora rose to her feet, feeling a little overstrung, and suddenly fearful of the outraged proprieties.

"I must really go," she said stiffly. "I have no business to be here."

"Of course you haven't," agreed Jim, in shocked tones.

All the same he hastened to shut the door which Blair darted forward to open.

"By the way," he continued, "my name is Milton. I really cannot allow you to call me 'Jim' any longer. So now we're properly introduced, or shall be, when you've told me who you are."

Thora moved an inch away from the door, her mind at work on three facts. Firstly, this was the most interesting man she had ever met; secondly, this time to-morrow she would be on the sea, the steamer's nose turned towards Canada; thirdly, who was Maude?

She yielded to the appeal in Milton's eyes, and sank back into her chair. She noticed that Blair seemed annoyed at her action, for he started to pace the room like an impatient caged beast.

"My name is Thora Steel," she began, "and my father is a clergyman."

She stopped, bewildered by the men's suddenly stifled laughter.

"I believe you." Milton assured her quite unnecessarily. "Well, look upon this as a sort of district visit, quite in your line. Besides, I have a parson relative, too, to make you feel at home. There he is on the wall. We'll look on the Reverend Clifford as our chaperon."

Thora had hardly glanced at the narrow fanatical face in the photograph, when an exclamation from Blair startled her. She noticed that his face looked still more ghastly.

"For Heaven's sake, Milton, stop!" he muttered. "This is going too far!"

Thora looked from one man to the other, misgiving again stirring in her heart.

"I think I'll go," she murmured.

"Not yet!" Milton's smile again reassured her. "It's too cruel to leave us in the lurch. This old Blair thinks I'm too rapid in my friendships, that's all. What were you saying?"

"We live on a station in Canada," Thora again took up her tale. "Father is the only parson for miles around. It's like being buried. I've had a short holiday here—staying with an aunt in Streatham. This time to-morrow I shall be on my way back. So you see, it was my last chance, and I did so want an adventure!"

"Quite so." Jim nodded. "But the voyage. Plenty of chance there." Thora hung her head. "I'm such a wretched sailor," she faltered, feeling her answer a bad blot on romance. "I never leave my berth."

"Hard lines." Her words seemed to please her companion, as though he disliked the thought of possible ocean flirtations. "Well, now you've had an adventure of sorts. Something to talk of, I suppose. I should rather like to know what you've made of it."

Thora looked at the alluring face on the wall that presented such an odd contrast to the Rev. Clifford.

"It's simple," she said, with evident pride in her powers of deduction. "I suppose you're in love with that woman—Maude, and you're expecting her to come here every minute. That horrid man, who came in just now, has some sort of claim on her—her husband very likely. You were afraid he would come in and stay until she came. That's why you kept me here, as a blind, and also to send him away. I've been a sort of catspaw, I suppose. And now, since she may come any minute, I'll go."

The two men exchanged rapid glances, and Milton looked at the clock.

"Stay just half an hour longer!" he pleaded. "That chap may come back yet. Besides I've something I want to say."

He lowered his voice.

"You think I'm in love with Maude!"

"Why not? She's beautiful enough. And it's no concern of mine. We're strangers."

"Not now." The note in Milton's voice suddenly dissipated her wretched pangs of jealousy. "D'you know, I've never met anyone like you before? Maude! I'm surfeited with Maudes. Wish to be quit of her for ever! Perhaps you understand now why I was so anxious that man should not find her here. She's in Society, you know. There'd be scandal. I did not wish to be compromised for the sake of a burnt-out flame."

Thora's ingenuous face betrayed her relief.

"It is so horrid to feel you've been used in another woman's love affair," she said. "And if you really like—I'll stay just a little longer."

It really seemed to her only a little longer that she stayed, although the clock told another tale—the minutes slipped away so quickly in the red-lit room. Undeterred by the presence of Blair, who fidgeted with a book, Milton and Thora talked with lowered voices. It seemed to the girl that nothing she said was too trivial to arouse Milton's interest. He asked so many questions and received her confidences with such sympathy, that her head was turned with conquest.

Woman-like, she resolved to test her power.

"Now, tell me something," she commanded. "About Maude!"

"Maude?" Involuntarily, Milton gave a violent start, and he glanced sharply towards a heavy curtain that screened an alcove at the end of the room.

Thora followed the direction of his gaze. She was positive that she could discern a slight bulge behind the portière that might have been the outlines of a human figure. At the sight she was seized with a sharp revulsion of feeling. Milton had deceived her.

As he noticed her stare, he gave her a slight nod.

The feeling of fear that had filtered through the girl's mind gave way to a rush of indignation. It was infamous to reflect that all along he had known that there was an eavesdropper—an unseen witness of their tender conversation—possibly some woman who laughed in her sleeve.

"Is there a woman behind that curtain?" she demanded haughtily. "Is it—" she had difficulty in forcing herself to utter the hateful word. "Is it—Maude?"

Milton glanced at Blair. Then once more he nodded.

"Hush!" he said. "If you must really go now, I'll see you a little way."

He seized his hat and muffler as he spoke, and moved towards the door. But Thora did not move. "I feel, in the circumstances," she said haughtily, "I ought to see the woman for whose sake I have lied."

Milton read the injured pride and jealousy in the immature little face.

"Not for hers!" he said quickly. "For mine. Listen, Thora! Haven't I made it plain? I've done with her!" He snapped his fingers. "Done with her for ever. It's been your score all along. A bit of a comedy if you think of it. Like the screen scene from 'The School for Scandal.' Here she's been, cooped up behind that curtain, cramped and uncomfortable, yet not daring to show her face. She knows I'll never return to her—now!"

His eyes were ardent. Young though she was, Thora knew that only some overpowering emotion could have brought the flush to his face.

"Look here, Thora," he proceeded. "At the beginning of this adventure you trusted me. Now I'm going to trust you with my secrets."

Heedless of Blair's smothered ejaculation, he continued.

"I want you to leave this room, perfectly satisfied that all is above-board—that I've no shady corners I wish to keep dark from you. Personally, I would rather you did not raise that curtain. At the same time, sooner than doubt me, I wish you to look. The choice I leave with you!"

Thora's heart swelled with triumph. This was the culminating point in her adventure—the real romance. Incredible though it seemed, the strong attraction she had felt for this man had been duplicated within him. It had been a fusion of two live wires. And in earnest of his passion he had sacrificed this woman to her.

Moved by overpowering curiosity, she walked towards the portière. The two men drew near also. Blair's lips worked nervously in his anticipation of a scene, but Milton merely smiled. He twisted the muffler in his hand, but that was his sole sign of any suspense.

Thora's hand was outstretched. Then it fell nervelessly to her side. A sudden distaste seized her. This shady episode in a man's history was no concern of hers. Her whole nature recoiled before stirring up muddy depths.

"I—I'd rather not look!" she said.

Milton drew a breath of relief.

"I felt sure you wouldn't. I'm glad of it. And now come away!"

Thora could understand now his anxiety to get her out of the room away from Blair and the woman. When they were outside on the landing, she turned to him, half dreading the words she felt sure he would utter. To her surprise, he merely rang for the lift. Chilled with disappointment, she looked timidly at him as they shot downwards. He seemed suddenly to have grown older and played out—a mere shell of a man. The tears started to her eyes. She had had her vision of walking slowly down those stone stairs, with him—treading on air—while she listened to his promise to come to her in her exile—like the fairy-prince of romance.

Side by side, they walked soberly out of the building and into the quiet street. Then the man spoke in a formal voice. "I should like to say something. Will you promise me never to embark again in such an adventure? I have sisters like you—dear little souls!—but terribly young and inexperienced. I should be sorry to have seen them in your shoes to-day. Be grateful Fate led you to my door—and no-one else's in this building!"

Thora could hardly believe her ears. Her unconventional eager lover had suddenly merged into a prig. She felt she was being blamed.

"But—but it was you who asked me to come in," she faltered.

"Well, I hadn't sized you up then. What would a man think of a girl who knocked him up on a flimsy pretext? But there's no harm done. I promise you I will keep this little indiscretion of yours a dead secret. If you are wise you'll never mention this to a living soul, or you might find yourself compromised."

"Thank you. I can keep my own counsel."

Thora reared her head proudly in the air, while she bit her lip to keep back her tears. Her adventure had proved to be nothing but a hollow fraud, with a sermon for its epitaph.

Then she was aware that Milton had taken her hand.

"Good-bye. I shall often think of you, dear little Sweet Seventeen!"

He turned and left her. Smarting from the blister on her self-respect, Thora walked away into the violet twilight, disconsolate for the moment, and crushed and disillusioned, even though her life was in the Spring, and Summer lay before her.

Meantime, Milton had gone back to the flat as quickly as the lift could take him. He seemed no whit surprised to find Blair alone. Glancing at his ghastly face, he poured out some brandy.

"Here!" he said roughly. "It's all right. She'll never split. I've left her crushed and humbled to the dust. There was humour in some of my remarks." He smiled grimly at the recollection. "It was the devil's own luck her turning up like that. No-one else would have kept that hound Candy from nosing round. She'd have whitewashed the Fiend himself!"

Blair nodded as he gulped down his drink.

"What induced you to play the fool like that at the end?" he asked thickly. "You stood to ruin all."

Milton suddenly wiped his face.

"Because it was the only thing to do. It was vital to our interests that she should leave this room satisfied there was no secret or mystery. Good lord! My relief when she decided not to look. I didn't want to—"

He broke off to drink some more brandy.

"Besides there was no risk," he continued quietly, taking no heed of the look of horror that deepened in the other man's face.

"Didn't you notice I was ready for her?" He picked up the muffler, with trembling fingers. "Pity she'll never know she's had the adventure of her life—poor innocent! If she'd drawn that curtain, she'd never have drawn another breath!"

Then squaring his shoulders, he walked towards the curtain.

"Pull yourself together, Doctor!" he commanded. "You'll have to work now like the devil!"

He spoke truly. There was devil's work to be done.

For, as he drew the portière, a silent huddled figure fell limply forward upon the carpet—all that was left of the murdered woman—Maude.

The pictured eyes of her injured husband, the Rev. Clifford, stared at her dispassionately and pitilessly, from the wall. And the man whose youth and life she had wrecked, staggered back, in momentary recoil, at the fresh sight of his victim. The red-shaded lamps of stage-tradition, threw a rosy glow on the final tableau.

And a block away, a little girl, in a grey gown, crossed the road in safety, under the sheltering palm of the police.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.