RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

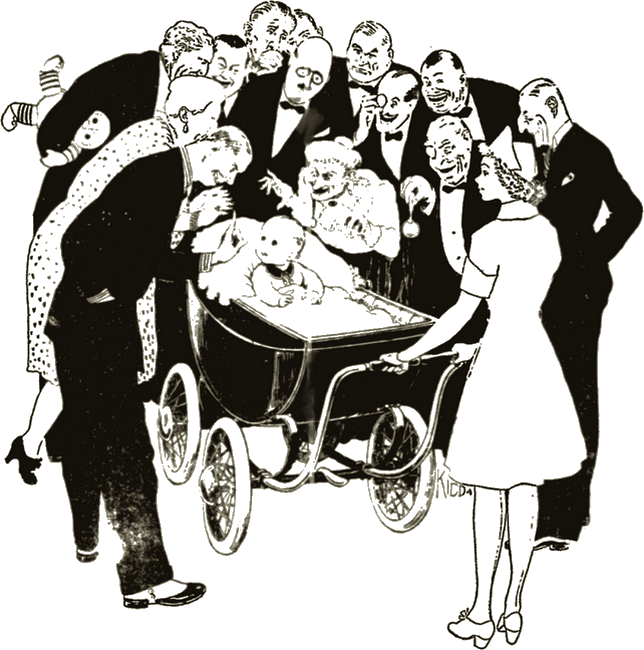

Annabel wheeled forward her precious charge.

He became immediately the center of a circle.

A young nurse's love and loyalty save a baby, and win a new home.

WHEN Annabel was nervy she would look at Wotherspoon about twenty times a day and murmur "How many people would like to kill you, Angel?"

And about twenty times a day, she declared with a determined thrust of her jaw. "But Belly won't let them."

"Belly" was the unrefined version of her poetical name decreed by Baby Wotherspoon. He had a heavy-handed way of dealing with human prejudices and destinies. It did not disturb him that his birth had upset a score of financial interests.

His millionaire father was a member of a large family. He liked none of them sufficiently for preferential treatment, but he was clannish and believed that money should not pass to strangers. Consequently, he had willed his wealth equally among Charities and his relatives.

Under this scheme, no one could be actually wealthy, but the inheritance was highly acceptable. Therefore when old Wotherspoon's third wife died in presenting him with a 10-pound son, the event was a family calamity.

There was a mighty battle for John Jasper's infant life, as he had contracted heart trouble in his sensational journey to this world.

Among the nurses, Annabel worked at top strength to keep him alive, so it was not astonishing that the millionaire offered her the job of permanent nurse to the important heir.

It was practically a death-bed charge, for old Wotherspoon's last illness developed a few months later. By that time, Annabel had become the abject slave of John Jasper, so she accepted the trust.

ANNABEL had no illusions about her job. The

remuneration was high, but she knew it could not

compensate her for the sacrifice of her youth and

liberty. She was also attractive and

vivid—red-haired, with beautiful coloring

and short features; yet her charm had to be wasted

while she was exiled in Sir Simon Wotherspoon's

house—"Four Winds," in the bleak and lonely

north.

As the most important relative, Sir Simon had been selected the baby's guardian. He was a retired Harley Street specialist and was responsible for John Jasper's health—an arrangement which did not interfere with his writing of a medical manual—while young Wotherspoon paid the expense of his establishment.

At first, Annabel was stimulated by the solitude and the stretch of open landscape. There were only two habitations in an extensive area—"Four Winds" and the cottage of a Professor Deane. A ribbon of lane wound from the York Road up to Sir Simon's house, continued for half a mile to the Professor's residence and then came to an end.

"Four Winds" was rather like a fortress, enclosed within a 10-foot wall, with two entrances. In front of it, there was a rolling view of field divided by stone walls. Behind it, lay the moor. The back gate led out to a rough path which sloped down to a steep gully through which flowed a swift mountain stream. This was spanned by a plank bridge and then the track rose up to the Danes' cottage.

The Professor and his wife Judith always used this short-cut across the moor when they visited Sir Simon. Every evening, they arrived after dinner, for a game of bridge with Sir Simon and his secretary—young Fish-Baker. It was the sole social engagement and one from which Annabel was excluded.

The house was not large and was practically divided between Sir Simon and the nursery. The work was done by a married couple—the Limes—while Annabel had a long-faced girl called "Horsington" as a nursery-maid.

In spite of her loneliness, she was not attracted to their only neighbors. The Professor was a sapless dreary man whom Annabel regarded as still-life; his wife, on the other hand, seemed driven on by a gale of mental and physical energy. She was thin, dark and possessed of a red-lipped, long-lashed beauty. During the day, she always wore shorts or slacks, but in the evening, she languished in rest-gowns of glamorous Hollywood tradition.

Annabel suspected that she was interested only in men and resented her as competition, for she never failed to crab her job.

"It's an appalling life for any girl," she declared. "You will become mental. No one can remain normal in this shattering loneliness."

"I'm married." Judith gave a triumphant laugh. "That makes all the difference... When I heard you were coming, I was afraid we might develop a triangular situation. It would have been ghastly if my husband had fallen for you."

Annabel had to bite back her true opinion of the professor's power of fascination.

"I can't imagine your husband falling in love," she said.

"Neither could I. I was one his students. Wasn't it gloriously romantic?"

ANNABEL liked the secretary no better than the

Danes. Fish-Baker had a small, pursed mouth and a

snobbish sense of social values.

The first night she was at "Four Winds," Sir Simon visited her nursery.

"I want you to know exactly what you are taking on," he said. "This baby is a Power in the financial world and not altogether a welcome one. In arranging for his future, his father altered his policy in respects which tangled up other interests. There are people who would gladly see this child dead."

"Oh, Sir Simon," gasped Annabel. "Can you tell me of special precautions to take?"

"Certainly. They may sound theatrical, but this is a melodramatic situation. To begin with, you cannot rule out the possibility of poison—in case of the Fifth Column operating in the kitchen. You must prepare his food and taste everything before you give it to him."

"Of course."

"Then there is the risk of kidnapping. He must never be left alone. It is not necessary to take him outside the house. He can get good moorland air from his veranda."

That interview was the prelude to a strange, withdrawn life for Annabel. Her world was enclosed in four walls, and her interests focused on John Jasper—his weight, his diet, his temperature and all that was his. She slept in his room, had her meals in the day-nursery and only left him in charge of Horsington while she took her daily walk on the moor.

OCTOBER passed with a shrill wind which scoured the

moor and bleached the heather to the semblance of a

tossing dun sea. The change in the landscape paired

with a corresponding difference in Annabel, She slept

badly, lost her appetite and her color and suffered

from nerves.

The truth was that Annabel was weighed down by a guilty secret.

She was a skilled nurse, trained in orthodox methods; but now that she was facing a crisis, she had allowed her instinct to triumph over her professional experience. Experiment had proved that Baby Wotherspoon throve only in defiance of the laws of health.

He could digest any food he fancied, while he threw up his proper nourishment. A breath of pure mountain air was enough to make him sneeze—and a cold was a menace to his heart. Even his personal taste was peculiar, for he preferred the advertisement photographs of motor-cars to the pictures of Snow-White & Co., on the white walls of his nursery.

It cost Annabel a terrible pang to outrage her code. But she had taken an oath that John Jasper should live and flourish to the confusion of his foes.

She had the sensation of living on the crust over an active volcano, for she knew that Sir Simon would dismiss her without a character, if he discovered her disobedience. But it was not the thought of her professional peril I which appalled her.

She dared not face the chance that she might be parted from Baby Wotherspoon because she was certain that she—and she alone—could rear him to boyhood.

THE October winds screamed themselves into silence

and November—gray and sullen—set in with

sheets of steady rain. The weather was depressing to a

normal person, while it appalled Annabel as a direct

menace to the baby's health. To shield him from the

peril of the raw air, she turned the nursery into a

fortress from which even Horsington was excluded and

she alone remained on guard—to the exclusion of

her own daily exercise.

Fortunately, Sir Simon was of set habits, so she was able to open the windows in readiness for his bi-daily visits; but she lived in constant fear of spies who might report the ban on ventilation. In her extremity, she sank to the deception of making a dummy bundle and placing it in the perambulator on the veranda.

OWING to the constant strain on her resource, she

had forgotten Sir Simon's warning about treachery. It

was the professor's wife who recalled to her the danger

of Fifth Column activity. One afternoon, Judith Dane

managed to storm the nursery and sink bonelessly down

on a rug.

"Warm," she said appreciatively. "Glad you're not a bleak, antiseptic nurse. I adore a rug."

"Then you're lucky." Necessity drove Annabel to lie. "The windows are shut while I get up the temperature."

Looking slender and attractive in black slacks and a blue-green pullover, Judith stared at the baby. She merely saw an overweight infant with a tendency to baldness. Annabel—who was also watching him—considered him a cherub, with adorable dimples in his hands and an enchanting chuckle. With the exception of his beloved "Belly," he addressed everyone as "That." His other word was "No."

He grinned at Judith's ultra-scarlet lips—clutched his nose tightly with both hands as though to keep it safe—and declared "No."

"I agree," said Judith. "It's 'no' every time... Did I ever tell you, Nurse, that I was a swell at biology? I was the professor's star turn. Well, speaking from a scientific angle, it is a crime to keep this child alive. He's far from being a 100-per cent specimen and he's stopping the survival of better lives."

Annabel controlled her fury by a laugh.

"You're talking high and don't mean one word," she said.

"Of course not. Perhaps I mean something else... A lot of people would like to see this child out of the way."

"Murder him? Oh! No, no."

"Kidnap him. He'd fetch a heavy ransom. His estate could stand the shock."

"But that would be murder. He couldn't live without me. The shock would be too much for his poor little heart."

"Then I'll give you a hint. On the first of December, the Trustees will pay their visit of inspection. They are relatives who have been cheated out of their expectations. Wouldn't it be an ideal time for one of them to arrange for the baby to be stolen, while he is here with the rest? He'd have a foolproof alibi."

"They'd find it impossible to kidnap John Jasper with me in charge of him. Besides, Sir Simon would also be on guard."

"But he's a relative too." Judith's voice was loaded with meaning. "Do Harley Street specialists make enormous fortunes? Their expenses must be staggering. Oh, by the way, one of the crowd is a real stinker. You can pick him out at a glance. I'm saying no more."

ALTHOUGH Annabel tried to ignore Judith's warning as

the invention of a neurotic woman, some of its poison

remained. When she lay awake at night, her mind

throbbed with feverish suspicions. She began to wonder

whether the lonely house had not been chosen by Sir

Simon to facilitate a kidnapping plot. Horsington too,

was a queer, silent creature. There was some mystery

about her, for Annabel sensed that she resented her

menial position. Although she tried to appear

uneducated, she had once quoted from a literary

classic, in an unguarded moment.

Annabel began to wonder if anyone in "Four Winds" could be trusted.

Above all, loomed the ordeal of the Trustees' visit. As the date drew near, the wind veered to the north and the weather became bitterly cold. Apart from the increased menace to John Jasper's chest, Annabel was grateful when a first scurry of white flakes shook from a leaden sky. Actually, the snow would prove her ally, if it kept the Trustees away.

"They won't be able to make it, if we're snowbound," she remarked hopefully to the secretary, the day before the official visit.

Fish-Baker glanced out at the white waste of moor and grimaced.

"It's only drifted to any depth on the moor. It would have to lie a jolly sight deeper to keen them away. The York Road will be clear and they can jam the lane in good cars. Under the hat, there's a carrot dangling in front of their noses."

"What do you mean?"

"None of them would lose their trustee-fee. Without betraying a confidence, I can tell you the figure is definitely stiff. The old bloke was so keen on protecting our young boss that he put all the family to check up on Simon. Hence these periodic inspections. I prefer to call them 'Suspections.'"

"Isn't one of them rather a swine?" she asked. "Oh! you mean Reginald. Definitely. Been in the Army once—and quod twice."

Suddenly, as though some connection of ideas had been established in his mind, his eyes grew shrewd.

"If you ever think about easy money," he said in a low voice, "you've only to make a contact. Nothing to do—merely relax your vigilance."

Annabel's face flamed with fury; but before she could speak, Fish-Baker began to laugh.

"Only testing your loyalty. It's in my book of words—'Suspect the nurse.' By the way, old Simon asks me to tell you the arrangements for tomorrow. The trustees will have lunch directly after arrival—inspect the heir—and go back after tea. Horsington will be wanted to help with the meals. And there'll be another guest. Sir Donald Frost is coming to examine young Wotherspoon."

Sir Donald Frost. The name sang in her head. He was the nurse's pole-star—young, good-looking, in the first flight and still rising. As a probationer, she had waited in hospital-corridors, merely to see him pass.

But now her jubilation was mixed with fear lest her unorthodox methods might be exposed. She went to bed praying for snow, snow and more snow, to keep the invaders away.

SHE awoke to a white blanket spread over the

countryside, but the weather conditions were not bad

enough for the trustees' meeting to be canceled. The

party, however, had evidently not realized the full

difficulty of their passage through the blocked lane;

but they arrived eventually in three powerful cars with

chains.

Even in the nursery, Annabel could hear the noise of their voices and laughter as Sir Simon greeted them. Lunch was very late and proved a protracted meal, for there followed a long and nerve-wracking period of waiting. Annabel had to strain her ears for the sound of footsteps coming up the stairs, so that she could rush to open the windows of the nursery.

To add to her worry, John Jasper was beginning to display an ominous interest in the snow. For the first time in her experience, he asked to be taken outside. Apparently he wanted to go skiing, tobogganing and all the other dashing things, for he grew very cross at being thwarted. When he cried, he roared and bellowed, so he had to be appeased, lest he should strain his heart.

Annabel was near the limit of her resources when—as the gray daylight began to fade—the nursery was invaded by the relatives. At first, she saw them as a prosperous hostile crowd, among which she picked out Sir Donald. His face was thinner and his figure a trifle more important, but he was no less handsome. His black hair shone as though burnished, when he bent over the baby's case-sheet, produced by Sir Simon.

"Nurse." he said in his fruity voice. "We are ready."

With a feeling of desperation, Annabel wheeled forward her precious charge. He became instantly the center of a circle, while Sir Simon presented him formally to the Trustees. Sir Donald concentrated on his examination—the relatives stared at the baby—and Annabel watched their faces.

Suddenly Annabel noticed an unnatural element—sheer gloating cruelty in the eyes of a vulture-faced man with red-lined cheeks. He caught Fish-Baker's attention and winked at him. As the secretary winked bock, Annabel recalled his remark about "easy money!"

Instantly her suspicions flared up again. Fish-Baker might not be a perfect fool, but he could be a perfect tool and used as a pawn in another's game. As the possibility of collusion flashed across her mind, the sinister Reginald—"Major" no longer—spoke to Baby Wotherspoon in a jocular vein.

"You may not know it, old boy, but you keep a damn good cellar. You do yourself proud. Simon, old boy, what about going downstairs for another spot?"

His sneering tone hinted that Sir Simon was taking advantage of her preferential position. To ease an awkward situation. Sir Donald began to congratulate Sir Simon on the baby's progress.

"His health shows an all-round improvement. Best of all, his heart is beginning to compensate... You've done excellently. Nurse."

AS a medical man. Sir Donald recognized the helper

to whom the credit was due; as a critic of feminine

beauty, his smile approved an unusually attractive

girl. Thrilled by his look as well as by his praise,

his words rang in Annabel's head after the relatives

had gone out of the nursery.

As she mechanically closed the windows, John Jasper was reminded of his thwarted desire for winter sports.

"No," he yelled, meaning 'snow.' "No."

Suddenly Annabel had an inspiration. Opening her store-cupboard, she rolled out a huge bale of cotton-wool from which she made pneumonia-jackets.

Unrolling a few yards, she spread them over the carpet.

"Come and play with Belly in the nice warm snow," she invited.

The experiment proved a great success, for the baby soon shouted with laughter. Engrossed in her game, Annabel did not hear Sir Donald's quiet, professional tread as he returned to the nursery.

"What are yon doing with that dangerous stuff?" he asked in a horrified voice.

Flushed with stooping, Annabel looked up into his disapproving face. Her lips trembled as she began to explain the incident. Instead of making any comment, he glanced around the room.

"You've got the window closed," he remarked. "What's the temperature?"

After reading the thermometer he crossed to the window and threw it open. His face set in a professional mask, he asked another question:

"Do you smoke?"

"Yes," she confessed. "I couldn't survive without my daily dozen of cigarettes."

"You will have to, in future, with all this inflammable stuff about."

"Oh, but I take no risks. I—

"You must consider the baby's safety before your nerves. Remember—no smoking."

DIRECTLY she was left with the baby, Annabel closed

the window, but she did not latch it—in readiness

for future emergency. Her mind was a turmoil of

emotions as she raged against the embargo on smoking.

Cut off from social life, she depended on tobacco as an

essential nerve tonic. As she grew calmer, however, she

was chilled by a menace which dwarfed her personal

grievance.

Sir Donald had stormed her fortress when her weak spots were exposed. He evidently considered her untrustworthy—and there were bound to be unpleasant repercussions.

While the party downstairs lingered over their tea, the short winter twilight deepened into darkness. Annabel rang the bell but no one answered its summons. Before she went to find Horsington, she looked around the nursery, to make sure that everything was safe and in order.

The fire was screened, the window closed and John Jasper was taking a nap in his day-bed.

She met Horsington in the hall and told her to sit with the baby.

While she lingered in the hall in the hope that Sir Donald might come out of the drawing-room, she heard a scream from above. Dashing upstairs, she collided with Horsington on the landing.

"Baby's gone!" she screamed. "There's a ladder at the window!"

STUNNED with shock, Annabel staggered into the

nursery. She stared first at the empty day-bed and then

at the ladder-head before she crossed to the window. As

she looked down at the illuminated snow, she saw

footprints leading down to the front gate.

Horsington rushed down the back-stairs and threw open the landing window. Tearing after her, Annabel stared down on the strip of path lighted by the back-lobby lamp.

It revealed only a white unbroken surface.

Suddenly Annabel realized that Horsington was speaking to her in an insistent tone. It suggested the necessity for speed.

"Will you tell the master? Or shall I?"

With an effort, Annabel wrenched herself out of her frozen trance or horror. Feeling that the situation was too monstrous to be real, she went down to the drawing-room and blurted out her tale. Although she was dimly aware of a storm of excitement breaking all around her, she answered Sir Simon's questions with unnatural calm. It was not until the others had rushed outside, leaving her alone, that she awoke to the shock of realization.

Baby Wotherspoon had been kidnapped.

With a professional horror of hysterics, she pressed her hands to her lips, forcing back her screams. Rushing blindly up the stairs, she ran into the nursery, where the sight of the empty bed made her break down utterly. Unable to endure it, she went down to the back-stairs landing and stood by the open window. Above her the stars glittered in the black sheet of the sky—below, stretched the blank white path. Then she laid her head down on the sill and tried to stifle her sobs.

For the second time, Sir Donald stole on her unawares.

"Well," he said, speaking in a matter-of-fact voice, "it's a planned job. The ladder had been placed under the window in readiness, for it was covered with snow. The footsteps led down to the front gate. From there, the kidnapper must have gone by car down the lane to the York road. There are only the marks of car-tires there, while there are no prints of any kind in the lane that goes on to the cottage."

"What is Sir Simon doing?" asked Annabel dully.

"Hitting the trail in the hope of catching up. But that stout man insisted that the cars should be searched first, in case the child was packed into the luggage-boot. He argued that they were all under suspicion until proved innocent."

"No," said Annabel, "I'm the only one to blame. I should never have left him. I didn't latch the window after you."

"After me?"

"Yes... I disobeyed all Sir Simon's orders. He didn't bring Baby on. It was all my work—my instinct. I found out that the ordinary rules did not apply to him. He made his own rules, bless him. But if I hadn't kept him happy, he would have been too bored to go on living. I had to stimulate his brain or it would have degenerated. Do you understand?"

"Yes... Perfectly."

"But what's the good of it all now? He can't live without me. Nobody will know how I loved him from the very first. He was such a darling little John Bull, with all the odds against him, poor fat mite. But he hung on... I'll never forgive myself. I've just taken a vow never to marry or have a child—because I let him down."

"Steady on. Have a cigarette?"

Sir Donald put the cigarette between her shaking lips, lit it—and then threw the match through the open window.

The next second, he gave a shout. Underneath their eyes, the snowy path was on fire!

IT blazed fiercely for about a minute, sweeping

downwards in a line before it died, revealing dark pits

in the snow.

Instantly Sir Donald realized the explanation of the phenomenon.

"The kidnapper's trail," he said in an excited voice. "He covered it with cotton-wool. We must follow it up. Quick."

Although she wore thin white shoes to match her overall, Annabel rushed after him down to the lobby. Outside, the path which led to the moor was scored with the impression of boots when they kicked aside the rags of charred wool. The roll had lasted until outside the radius of the light—when, having served its purpose, it came to an end.

Treading in Sir Donald's footsteps, like the page in the carol, Annabel followed the beam of his torch as it picked up the trail. It led them down to the bridge across the gully and then over the moor, up to the Danes' cottage.

"Oh, no!" tried Annabel. "We've gone wrong. It couldn't be them. They've nothing to gain."

"Come on," insisted Sir Donald "I'm going to rush them!"

After hammering upon the cottage door, he pushed it open and went into the empty hall.

"I've come for the child!" he shouted. "Thanks for the trail."

As they waited, he touched Annabel's arm and pointed to the pads of melting snow which still lay on the dark-blue carpet. Then Judith came out of a room, holding a bundle in her arms. Her eyes flashed defiance and her lips were a scarlet line in her ghastly face.

"I did it. You know why. My husband knows nothing."

Sir Donald took no notice of her. Instead, he turned to Annabel and pushed her towards the door.

"We must get him back at once," he said. "You'd better take him."

As Annabel looked with anguish into Baby Wotherspoon's poor blue face, his rigid limbs suddenly relaxed as though he recognized the touch of his beloved's protecting arms.

"He knows me," she said.

Together they crashed across the snowy moor back to "Four Winds" where Sir Donald issued another order.

"Carry on. You know what to do. I'm going back to the cottage. I want a chat with that charming couple—just for the records."

WHEN he returned to the nursery, Annabel sat before

the fire, feeding John Jasper who sipped milk and

brandy with real appreciation of his cellar.

"You darling little boozer," murmured Annabel, adoring him with her eyes, before she spoke to Sir Donald. "What happened? I still can't believe it of them."

"Naturally," he agreed. "While everyone suspected the relatives, no one remembered the Charities who were equally disappointed by the baby's birth. They were—and are—above suspicion. But the Professor had been building his hopes on taking control of the new Wotherspoon's former will. Apparently the disappointment turned him slightly mental. He planned the kidnaping—taking advantage of the trustees' meeting and the snow—and he forced his wife to play her part."

"Forced her?" repeated Annabel incredulously.

"Yes, he may look meek, but he's a dominant partner. I knew her when she was a beautiful brilliant student. I was shocked by the change in her."

"But how did they steal John Jasper?"

"Inside work. Real fifth column. Horsington is Dane's daughter by his first marriage. Directly it was dark, she stole through the front door, followed the path which was already beaten in the snow by the visitors, as far as the gate, and from there struck out towards the ladder. She placed it outside the window and then returned to the house, still keeping in her tracks. Fortunately for her, you played into her hands by asking her to watch the baby. Otherwise she would have made her chance. As it was, she gagged the baby, placed him on the veranda—in a perambulator underneath a dummy bundle—opened the window and then screamed."

"He was there—all the time?" gasped Annabel.

"Yes. No one would waste time in searching the room with a ladder stuck outside an open window. Directly she got rid of you and she guessed that everyone would be safely outside at the front of the house, she threw the roll of cotton-wool down the back-stairs and followed herself with the baby. The Professor and his wife were already on the moor by the back gate, waiting for her to signal with a light. They rushed up to the lobby where one of them grabbed the baby while the other drew out the roll of cotton-wool behind them as they went down the path, covering up their footprints. A most ingenious idea, for in the dim lamplight the deception was perfect. It looked a soft unbroken surface."

"But they knew they must be found out."

"Why? They planned to remove the cotton-wool before it was discovered. Once they had established their alibi—no trail on the lane or the short cut—their footsteps would be accounted for in the normal way, for they would make them coming across for their nightly bridge."

"What were they going to do with my baby?" asked Annabel in a low voice.

"I'm afraid they counted on his dying from shock," replied Sir Donald. "Anyway, they meant to park him in the snow all night and bring up his body in the morning. Their story would be that they found it on their doorstep."

"Fiends."

"I agree. Of course, the Professor took the detached scientific view—divorced from humanity. One life against millions, you know... Sir Simon will suggest that they leave the country. By the way, he wants to unload young Wotherspoon on me. I live by the sea on the south coast, which will suit him better. I must ask him to choose his own nurse."

As though in answer to his question, John Jasper looked drowsily up at the face bending over him and spoke in recognition of his Beloved.

"Belly."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.